Mitochondria are the powerhouses of mammalian cells,

providing the energy and materials required for cellular function.

Mitochondria utilize pyruvate, products from glycolysis, amino acid

metabolism and fatty acid oxidation to transfer electrons through

the electron transport chain, synthesizing energy in the form of

adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial dysfunction causes

bioenergetic imbalance and increases oxidative stress, which paves

the way for pathogenesis to occur. Multiple diseases arise from

mitochondrial damage or are a consequence of impaired mitochondria

due to tissue injury. Aging and degenerative diseases are common

examples of conditions involving mitochondrial dysfunction. While

genetic modifications and the reduction of telomere length are

definite hallmarks of aging, impaired mitochondrial function and

the accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations critically

determine healthy aging outcomes and contribute to longevity

(1). Degenerative diseases, such

as brain, muscle and macular degeneration are consequences of

mitochondrial dysfunction. Modifications in mitochondrial membrane

potential, reduced calcium homeostasis and decreased ATP production

are associated with mitochondrial dynamic dysregulation and

increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This leads to

protein degradation, the loss of intercellular interactions and

eventually, apoptosis (2-5).

For instance, in the immune system, reduced mitochondrial

respiration and metabolism are associated with immune paralysis

following septic shock (6,7). In metabolic syndromes, such as type 2

diabetes, mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes glucose

intolerance and excessive lipid accumulation in adipocytes, and

drives systemic inflammation, which further accelerates insulin

resistance (8-10).

Mitochondria have also been an unrecognized factor in the

progression of skin diseases (11). In pulmonary diseases derived from

smoking, cigarette smoke directly blocks complexes I and II, causes

mitochondrial depolarisation through altered mitophagy, and induces

mitochondrial ROS generation. This consequently results in the

apoptosis and necrosis of pulmonary endothelial cells, contributing

to the development of chronic and fibrotic conditions (12-14).

In addition, mitochondria exhibiting a low oxygen consumption rate,

high levels of mtDNA damage and ROS production are observed in the

vascular endothelial cells of preterm infants with bronchopulmonary

dysplasia and adverse outcomes (15). Mitochondria are also a key site for

calcium homeostasis, as they buffer cytoplasmic calcium ions

through interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum (16). The disruption of calcium balance

may interfere with mitochondrial respiration and ATP production,

leading to the development of pathological conditions and diseases,

such as neuron degeneration, cancers, diabetes, and muscular and

cardiac dystrophy (17-19).

Thus, the ability of cells to maintain competent mitochondrial

function and capacity is key to preventing disease progression and

negative outcomes.

Mitochondrial transfer refers to the process through

which cells exchange mitochondria, serving as a form of cell-cell

communication. This transfer may involve the sharing of damaged

mitochondria to signal neighboring cells about oxidative damage,

while surrounding cells offer functional mitochondria to stressed

cells. Receiving mitochondria supports cells in recovering from

oxidative stress, improving cellular respiration and ATP

production, and consequently, reversing the effects of cellular

dysfunction and tissue damage (20-22).

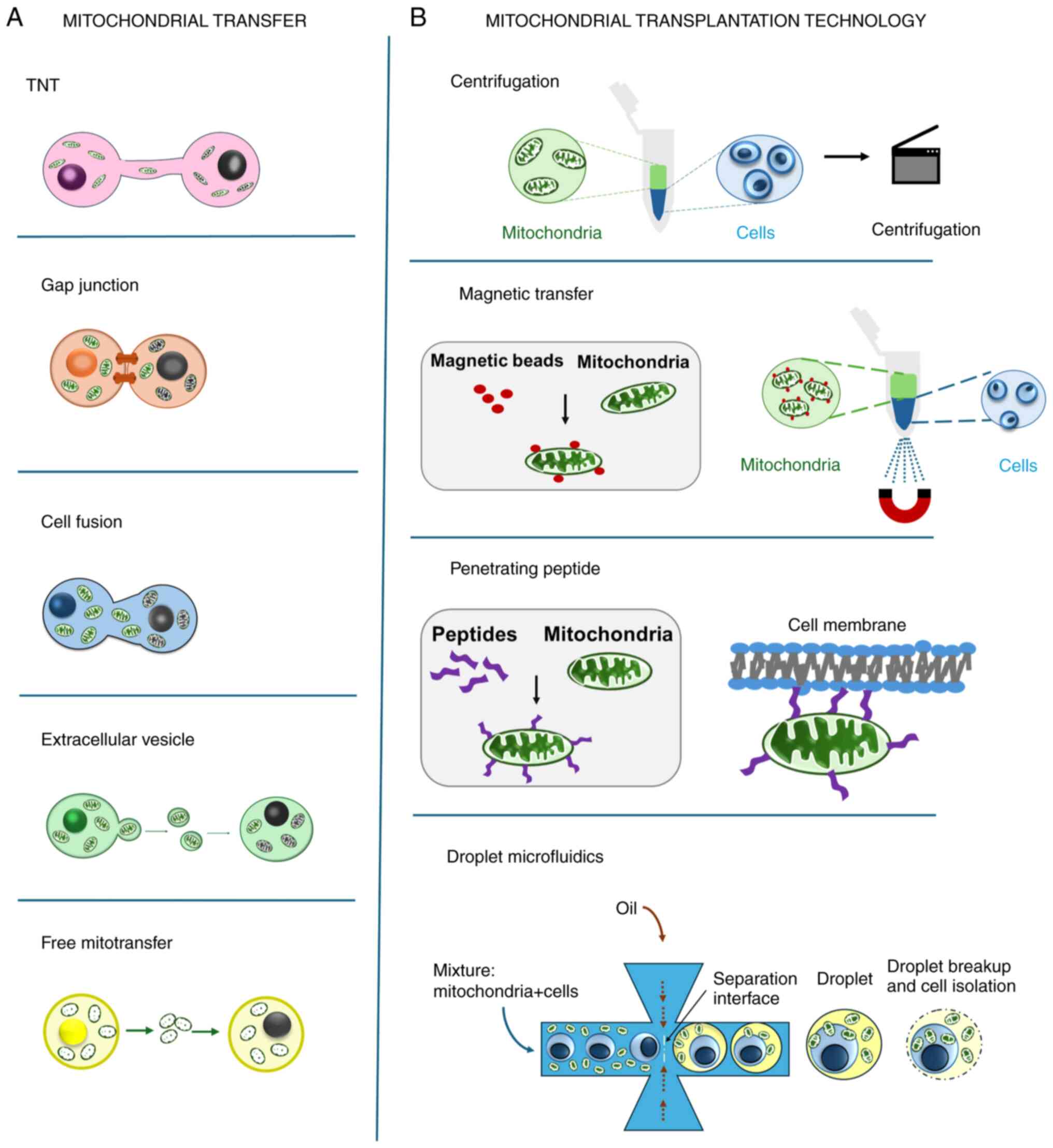

The mechanisms of intercellular mitochondrial transfer have been

well established and are illustrated in Fig. 1A. The application of mitochondrial

transfer has been transformed into mitochondrial transplantation

therapy (Fig. 1B), in which

exogenous mitochondria are isolated and artificially transferred

into cells or tissues. Mitochondrial therapy, which encompasses

both mitochondrial transfer and transplantation, is effective in

improving cell metabolism, restoring cells from stress and

preventing tissue degeneration (23-25).

Early clinical trials of mitochondrial therapy have been conducted

in ischemic diseases, demonstrating that the injection of exogenous

mitochondria effectively improves the conditions of patients and

reduces the recovery time (26,27).

These data indicate that mitochondrial therapy holds potential for

future applications. However, the autologous transfer of

mitochondria may be invasive and non-accessible in a number of

cases; thus, a source of qualified mitochondrial donors is

critical.

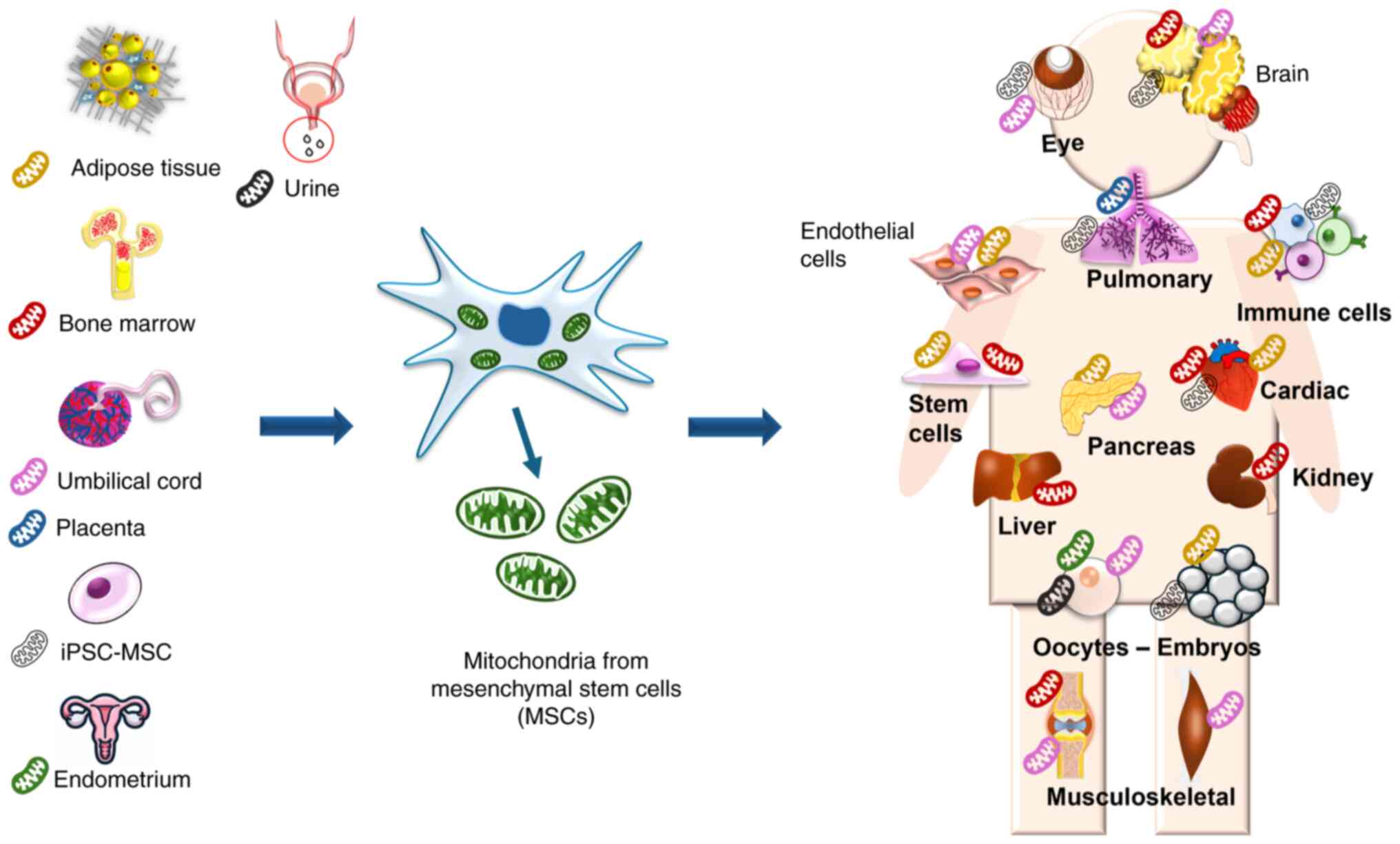

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) feature high

plasticity and proliferation, which demonstrates their inherent

mitochondrial capacity. The ability to acquire, handle and expand

MSCs in large quantities in culture, along with a stable and

reliable assessment of mitochondrial quality, may further

facilitate access to mitochondrial transplantation in various

clinical settings, rendering MSCs promising for such therapeutic

purposes. The use of MSCs as a mitochondrial source has been shown

in in vitro and in vivo models of different diseases,

indicating that mitochondria isolated from MSCs are efficient and

safe for translational studies (Fig.

2) (28-30).

The present review summarizes data from numerous studies in the

literature on mitochondrial transfer using MSCs as mitochondrial

donors. Detailed descriptions of the mechanisms underlying

mitochondrial therapy are also included. The present review also

provides an update on the broad application of mitochondrial

donation in various pathological conditions and diseases,

indicating that MSCs from different origins are valuable sources

for mitochondrial collection and transplantation technology.

Asthma is a chronic condition involving a persistent

inflammatory disorder in the airways (31). Mitochondrial dysfunction causes

oxidative stress and reduced ATP synthase activity, leading to

apoptosis and damage to airway epithelial cells, which results in

allergic responses and inflammation (32,33).

Through tunneling nanotubes (TNTs), mitochondria transferred from

MSCs have been shown to protect the human bronchial epithelium cell

line (BEAS-2B) against mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis

induced by cobalt(II) chloride (CoCl2), which has been

used as a hypoxia-mimicking agent (34). Connexin43 (Cx43), a transmembrane

protein encoded by the GJA1 gene, is essential for TNT formation

and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-MSC-mediated mitochondrial

transfer. This transfer alleviates the symptoms of allergic airway

inflammation by recovering mitochondrial function in the bronchi

and inhibiting programmed cell death in the lungs (34). The positive effects of

mitochondrial transfer have also been reported when inducing airway

inflammation by ovalbumin, specifically via the restoration of

mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and the inhibition of

caspase-3 and -9(34).

The dysfunction of mitochondria, which is associated

with changes in mitochondrial morphology and homeostasis and the

disruption of MMP in lung cells, is one of the main causes of

pulmonary fibrosis (PF) (35). ROS

overproduction in the mitochondria is associated with mitochondrial

dysfunction, leading to lung damage and inflammatory responses,

which contributes to the pathogenesis of PF (36). Increasing mitochondrial biogenesis

within human MSCs (hMSCs) using pioglitazone and iron oxide

nanoparticles has been shown to enhance mitochondrial transfer to

mouse alveolar epithelial cells (TC-1) damaged by bleomycin (BLM),

a treatment that induces mtDNA strand breaks and mitochondrial

respiratory chain dysfunction (37). TC-1 cells damaged by BLM exhibit

restored ATP levels, reduced intracellular ROS levels and recover

MMP when they receive functional mitochondria from hMSCs (37).

In the model of chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD), mitochondrial dysfunction due to oxidative stress

contributes to tissue inflammation and remodeling (38). Oxidative stress accelerates the

inflammatory process by stimulating neutrophils and macrophages

(39), leading to apoptosis,

autophagy and cellular senescence in the airways (38). Smoking is a well-known contributing

factor to the development of COPD and airway structure remodeling.

Cigarette smoke medium (CSM) has been shown to alter mitochondrial

metabolic regulation, leading to glycolysis and ROS production

(40,41). It was previously demonstrated that

the transfer of mitochondria from iPSC-MSCs reduced intracellular

ROS levels and prevented MMP impairment in airway smooth muscle

cells induced by CSM, significantly decreasing apoptosis by 50%

(42). Antoehr study demonstrated

that BEAS-2B cells treated with 2% CSM for 24 h induced significant

inflammatory responses and oxidative stress without leading to cell

death, and also received mitochondria from bone marrow-derived MSCs

(BM-MSCs) (43). Mitochondrial

transfer from BM-MSCs to BEAS-2B cells treated with CSM showed

recovery in intracellular ATP levels (43). This evidence indicated that

transferring mitochondria from MSCs can restore mitochondrial

dysfunction in the respiratory system by preventing oxidative

stress, reducing epithelial cell death, and airway inflammation,

and is a potential supportive method in pulmonary diseases.

In cardiac tissue, damage to cardiac muscles can

initiate numerous cardiac issues. For example, progressive

myocardial damage can be caused by the use of anthracyclines,

including doxorubicin, which are commonly used as drugs for the

treatment of cancer. Mitochondrial biogenesis inhibition has been

shown to contribute to this damage (44). The overproduction of ROS caused by

doxorubicin induces mitochondrial dysfunction through the

impairment of MMP, the opening of mitochondrial permeability

transition pore (mPTP), and the alteration of mitochondrial

morphology in human vascular endothelial cells (45). Mitochondrial dysfunction caused by

doxorubicin has a significant effect on cardiomyocytes as

mitochondria comprise 40% of the volume of each cardiomyocyte, and

the majority of energy in these cells is generated through

mitochondrial respiration (46).

In this context, the supplementation of fresh mitochondria could be

beneficial. Evidence has indicated that the injection of autologous

mitochondria isolated from skeletal muscles into the ischemic

hearts of pediatric patients effectively helped them separate from

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (27). However, isolating mitochondria from

skeletal muscles may be invasive and impossible in some cases.

Thus, a readily available source of healthy mitochondria for

transplantation is expected to advance current treatment. As such,

MSCs appear as a potential source for mitochondria isolation due to

their rapid proliferation. Several studies have demonstrated that

MSCs may be a safe source for mitochondrial transfer in

cardiovascular conditions (Table

I). A previous study demonstrated that functional mitochondrial

transfer by iPSC-MSCs protected against doxorubicin-induced damage

in cardiomyocytes from neonatal mice, resulting in a marked

recovery of the mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR), ATP

production, and optimal mitochondrial respiration in cardiomyocytes

(47). It was noted that this

effect was distinct from the paracrine activity of MSCs and

involved mitochondrial Rho GTPase 1 (Miro1), an outer mitochondrial

membrane protein, in the formation of TNTs (47). In another study, the

transplantation of mitochondria derived from MSCs reduced apoptosis

and ROS levels, while increasing ATP production in cardiomyocytes

treated with doxorubicin (48).

Mitochondrial dysfunction is also a key event in

simulated ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) (49). Abnormal mitochondrial morphology

and irregularities in mitochondrial quality control have been

identified as cellular mechanisms leading to IRI (50). Mitochondrial ROS production is a

primary target of damage caused by hypoxia (51). In an ischemic model, MSCs were

shown to reduce the death of H9c2 cardiomyocytes when co-cultured

under hypoxic conditions for 150 min via the transfer of healthy

mitochondria (52). In another

study, BM-MSCs delivered functional mitochondria to injured H9c2

rat ventricular cells, which were cultured in a medium deprived of

serum and glucose and incubated under hypoxic conditions for 12 h

(53). Co-culturing injured H9c2

cells with BM-MSCs showed significant downregulation of Bax

expression and an upregulation of B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2)

expression (53). Furthermore,

BM-MSCs also decreased the caspase-3 levels induced by SI/R in H9c2

cells, as this enzyme is an executor of the apoptosis process

(53). However, when BM-MSCs were

treated with latrunculin A (LatA), which is known to inhibit TNT

formation, apoptosis increased (53), suggesting that TNT formation is

critical. In another study, when co-culturing human adipose-derived

stem cells (hADSCs) with rat cardiomyocytes for 24 h under hypoxic

conditions, functional ADSC-derived mitochondria enhanced the OCR

of rat cardiomyocytes. This effect was shown to be independent of

the paracrine effects from ADSCs (54). On the other hand, mitochondria

released by damaged somatic cells, such as hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2)-treated RL14 cardiomyocytes or human

umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), activate MSCs to

transfer healthy mitochondria toward dying cells (55). Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is a

rate-limiting enzyme in heme metabolism and exerts a wide range of

anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and immunoregulatory effects in

various diseases (56).

Co-culturing MSCs with RL4 cells damaged by

H2O2 and HUVECs leads to the increased

expression of HO-1 and enhances HO-1 enzyme activity in MSCs

(55). These data indicate that

MSCs are promising sources of mitochondria that can be used for

mitochondrial transplantation technologies.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common musculoskeletal

disorder related to the aging process, which is characterized by

cartilage degradation, joint pain, and impaired function (57). Chondrocytes play a functional role

in the synthesis, deposition and formation of the extracellular

matrix of cartilage tissue (57).

The mitochondria of chondrocytes in the OA model exhibit a reduced

activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC) enzymes (complex

I, II, III, IV and ATP synthase), along with decreased MMP

(58). Furthermore, mitochondria

exhibiting a swollen morphology and loss of cristae regularity have

also been observed in chondrocytes in models of OA (58). Mitochondrial dysfunction and energy

metabolism disruption markedly contribute to the pathogenesis of

OA, including cartilage degeneration, increased synovial

inflammation and the calcification of the cartilage matrix

(59). The abnormal alteration in

the metabolic process of cartilage cells is a response to

inflammation and is correlated with the process of cartilage

degeneration (60). In a previous

study, the bilateral anterior cruciate ligament and medial meniscus

were resected in 8-week-old rats to induce OA pathogenesis

(61). Functional mitochondria

from BM-MSCs rescued OA chondrocytes from mitochondrial dysfunction

by restoring the normal morphology of mitochondria, MMP, MRCI, II,

and III activity, citrate synthase, and ATP content (61). Another study indicated that

mitochondrial dysfunction in chondrocytes in OA is characterized by

a reduced type II collagen secretion (58). It should be noted that type II

collagen and proteoglycans are key components of cartilage tissue

(62). OA chondrocytes co-cultured

with MSCs showed a significant increase in the concentration of

type II collagen and proteoglycan compared to the OA chondrocytes

group (61). Another study

indicated that inhibiting mitochondria in chondrocytes with agents

such as rotenone or oligomycin promoted MSCs to transfer functional

mitochondria to chondrocytes with mitochondrial dysfunction

(63). Although chondrocytes adapt

to low oxygen conditions, a number of their functions are still

oxygen-dependent (64). Thus,

culture conditions, such as hyperoxia and hyperglycemia, affected

the mitochondrial transfer from MSCs to chondrocytes because

chondrocyte homeostasis responds to the low oxygen levels and

nutrient-deficient conditions in vivo (63).

Tendon injuries often occur in the severely hypoxic

zone, characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction and increased

oxidative stress (65).

Mitochondrial dysfunction is characterized by an increase in ROS,

decreased superoxide dismutase activity, and a reduced number of

mitochondria, all of which contribute to tendon pathology (66). In a previous study on a murine

model of supraspinatus tendinopathy, mitochondrial dysfunction led

to the altered expression of genes related to morphology and

abnormal mitochondrial quantity associated with the development of

tendinitis (67). Another study

indicated that H2O2 activated the apoptotic

pathway by inducing oxidative stress and the depolarization of MMP

in mouse models of Achilles tendinopathy (68). Tenomodulin (TNMD) is a marker

specific to tendons and contributes to the durability and aging of

tendon tissue at the tissue level (69). TNMD is associated with the

structural and functional properties of collagen 1 (COL1) (69). A reduction in the levels of

tenomodulin is a sign of pathogenesis. Mitochondrial transfer from

BM-MSCs to H2O2-damaged tenocytes triggered

anti-apoptotic mechanisms and restored mitochondrial function by

recovering MMP and ATP levels (70). Functional mitochondria derived from

MSCs enhanced the expression of TNMD and collagen 1 and reduced the

expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1 in tenocytes treated with

tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (71). Moreover, functional mitochondria

from MSCs also reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such

as interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6(70), demonstrating an anti-inflammatory

effect.

Mitochondria contribute to several key functions for

the survival of muscle cells, such as ATP production, substrate

biosynthesis, metabolism and participation in the regulation of

apoptosis (72). Skeletal muscle

atrophy is characterized by a reduction in muscle mass and strength

and is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction as mitochondria

occupy a significant portion of muscle cell volume (72,73).

The reduction in mitochondrial mass, MMP, ATP production and

mitochondrial glucose metabolism activity are characteristic

features of muscle atrophy (74).

ROS overproduction related to mitochondrial dysfunction is the main

mechanism associated with muscle atrophy (75-77).

Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction has also been implicated in the

pathology of muscular dystrophy (78). The restoration of mitochondrial

bioenergetics has been shown to ameliorate the progression of

muscular dystrophy in mice (79).

Dexamethasone is an agent that induces muscular atrophy through a

process of pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death involving

inflammation as the initial process (80). A previous study demonstrated that

mitochondrial transplantation derived from umbilical cord-derived

MSCs (UC-MSCs) promoted myofiber hypertrophy and reduced

intracellular lactate concentration in dexamethasone-induced

atrophied muscles (81). This also

contributed to enhancing the expression of muscle-specific markers,

such as desmin and activated adenosine monophosphate-activated

protein kinase, which aided the functional recovery of atrophied

muscles (81).

These data indicate that the use of mitochondria

isolated from MSCs may be beneficial in different types of

pathology in the musculoskeletal system. The addition of MSC

mitochondria aids in the restoration of various cell types, the

construction of different functional parts, and the reduction of

tissue destruction caused by immune responses to stress.

Ischemic stroke is associated with a reduction in

cerebral blood flow, leading to severe oxygen and glucose

deprivation (OGD) in neurons (82-84).

OGD has been shown to cause neuronal mitochondrial dysfunction,

such as reduced mitochondrial complex I activity, MMP collapse,

decreased ATP synthesis and increased oxidative stress (85). Transient focal cerebral ischemia is

characterized by irreversible neuronal loss, leading to persistent

neurological impairment in individuals (86). The in vitro model of brain

ischemia is a state of OGD closely related to oxidative stress due

to the overproduction of ROS (87). In a previous study, mitochondrial

damage in astrocytes caused by OGD, which resulted in fragmented

mitochondria, stimulated the transfer of functional mitochondria

from multipotent MSCs (MMSCs) to astrocytes (88). The functional mitochondria from

MMSCs not only restored bioenergetics, but also normalized the

proliferation of neuron-like ρ0 PC12 pheochromocytoma cells,

which carried damaged mitochondrial DNA and generated most of their

energy through anaerobic glycolysis (88). Injured astrocytes received more

functional mitochondria from MMSCs when MMSCs overexpressed

Miro1(88). Furthermore, BM-MSCs

also transferred functional mitochondria to VSC4.1 motor neurons

injured by OGD (89). BM-MSCs

exhibited an increased CD157 expression when co-cultured with

VSC4.1 motor neurons injured by OGD, an effect that enhanced the

mitochondrial transfer capacity of BM-MSCs (89). Mitochondria derived from BM-MSCs

could alleviate apoptosis and inflammation in damaged VSC4.1 motor

neurons and promoted the outgrowth of VSC4.1 motor neurons, but

only affected their length without changing their number (89). The mitochondrial transfer from

iPSC-MSCs increased intracellular ATP levels in PC12 cells

following CoCl2-induced hypoxic damage (90). Furthermore, the mitochondrial

transfer from MSCs improved mitochondrial respiration, ATP

production, and the basal metabolic rate in neurons after

H2O2-induced injury (91).

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severe type of central

nervous system injury and is associated with oxidative stress

caused by the excessive production of ROS (92). Mitochondrial dysfunction related to

mitochondrial homeostasis leads to the inactivation of

ATP-dependent ion pumps and is closely associated with the

activation of cell death (93).

Mitochondrial quality control and the mitochondria-related process

of ferroptosis play a crucial in SCI (94). Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent

cell death process that occurs due to the accumulation of damaged

phospholipids on the cell membrane and is associated with SCI

(95-97).

In a previous study, UC-MSCs were shown to transfer mitochondria to

HT22 neuronal cells under the stimulation of the ferroptosis

inducer Rsl3 when co-cultured (98). UC-MSCs helped to restore

mitochondrial mass, promoted mitochondrial fusion, restored MMP,

and balanced intracellular ROS and ATP levels in ferroptosis

neurons (98). Furthermore,

mitochondrial transfer from UC-MSCs reduced ferroptosis by

decreasing the total intracellular iron content and free

Fe2+ levels in neurons undergoing ferroptosis (98). Inhibiting ferroptosis using

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in injured neurons has been shown to

normalize mitochondrial morphology and MMP (96).

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a condition related to

the degeneration of the nervous system of the brain, and damaged

mitochondria are one of the causes of PD (99,100). Mitochondrial dysfunction has been

identified as a major factor contributing to the death of

dopaminergic (DA) neurons (101).

The dysfunction of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I is a

major cause of PD pathogenesis (102). The impairment of mitophagy and

oxidative stress are hallmarks of PD (103). Mitochondria derived from UC-MSCs

reduce DA cell death caused by 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium,

6-hydroxydopamine and rotenone (104). Furthermore, mitochondria derived

from UC-MSCs also reduce the mRNA expression of TNF-α and nitric

oxide synthase, and decrease the expression of IL-6 and IL-8

induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in murine microglia BV2 cells

(104). The reduced expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokines has been shown to alleviate oxidative

stress, inflammation and normalize mitochondrial dysfunction in a

mouse model of PD (105). In a

previous study, astrocytes derived from iPSC-MSCs provided

functional mitochondria to DA neurons damaged by rotenone, a

compound that inhibits complex I (106). Notably, the neuroprotective

effect of astrocytes was not due to paracrine activity, but

primarily to the transfer of mitochondria to DA neurons (106). The transfer of mitochondria from

iPSC-MSCs-derived astrocytes restored ATP levels impaired by

rotenone in DA neurons (106).

In addition, cisplatin is a chemotherapeutic agent

used to treat cancer; however, it is known to cause morphological

changes and mitochondrial dysfunction in mouse neurons (107). Cisplatin has been shown to cause

excessive ROS production and alter the mitochondrial content of

cells (108). The donation of

MSCs was shown to normalize the membrane potential of neural stem

cells (NSCs) treated with cisplatin, which had shown a marked

decrease in basal respiratory capacity, ATP levels, and MMP

(109). Furthermore, excessive

expression of Miro1 in MSCs increased mitochondrial transfer and

promoted the survival of NSCs (109). In summary, these findings

indicate that the transfer of functional mitochondria from MSCs can

improve mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal survival under

various pathological conditions in brain tissue (106).

Mitochondrial damage and abnormalities in

mitochondrial homeostasis are among the causes of ocular diseases

(110,111). The risk of mitochondrial damage

increases when the cornea is exposed to ultraviolet rays (112). Corneal endothelial cells (CECs)

play a crucial role in maintaining the transparency of the cornea;

therefore, a decline in their function will negatively impact

vision (110). Metabolic activity

and mitochondrial respiration, such as the tricarboxylic acid cycle

and acetyl coenzyme A-related enzymes, are closely related to the

survival and function of CECs (113). Therefore, the addition of

functional mitochondria is expected to support the recovery of eye

disorders where impaired mitochondria have been identified to play

a role. In a model of human corneal endothelial cells (hCECs)

damaged by rotenone, the inhibition of mitochondrial complex I and

increased ROS production were shown to promote the uptake of MSC

mitochondria through TNT, whereas healthy hCECs could not

accelerate similar effects (111,114). Rotenone-induced ROS promote

NF-κB, which enhances TNT formation via the upregulation of

TNF-α-induced protein 2 (TNFαip2) (114). The underlying mechanism has been

previously reported (115). The

contribution of functional mitochondria from MSCs improves basal

respiration, ATP production, and the expression of mitochondrial

component proteins, such as complex I, mitochondrial matrix

components and the mitochondrial membrane (111). The transfer of functional

mitochondria from MSCs is the primary mechanism for protecting CECs

from the effects of rotenone, although the paracrine effects of

MSCs are also a contributing factor (114). However, the transferred

mitochondria are either digested by lysosomes in the host cell or

excreted after 8 days (111),

suggesting that the therapeutic effect of exogenous mitochondria

may be limited to the short term in CECs.

Mitochondria play a crucial role in the functional

activity of renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) (125,126), and the disruption in

mitochondrial activities has been shown to cause the aging of renal

TECs, leading to renal complications and pathogenesis (127-129).

Hyperglycemia causes mitochondrial dysfunction, characterized by a

reduction in intracellular ATP and MMP, changes in mitochondrial

morphology, and the excessive production of ROS in renal TECs,

which contribute to diabetic nephropathy (130). A recent study revealed that high

glucose levels increased oxidatively modified proteins in

mitochondria and intracellular ROS in TECs (131). Streptozotocin (STZ) is an agent

that causes alterations in MMP and mitochondrial NAD and NADH

enzyme activity, leading to the inhibition of ATP synthesis, and

thereby inducing oxidative stress and apoptosis in pancreatic

β-cells (132). The use of STZ to

model diabetes has been shown to lead to cellular metabolic changes

and mitochondrial dysfunction in renal cells (133). In that context, mitochondrial

transfer from BM-MSCs was previously been shown to inhibit

apoptosis and ROS production in damaged proximal TECs induced by

STZ (29). This was achieved by

promoting the expression of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2

and Bcl-2, which are involved in regulating the process of

apoptosis of proximal TECs (29).

Furthermore, BM-MSCs-derived functional mitochondria improved the

expression of megalin, a surface receptor protein in TECs that

participates in the reabsorption of proteins from urine (134), as well as sodium-glucose

cotransporter-2 (SGLT2), a member of the glucose transporter family

in proximal TECs (29). Since high

glucose levels have been shown to reduce the expression of megalin

(which is also associated with glucose transport via SGLT)

(135), the recovery of megalin

and SGLT2 is a sign of improved TEC function.

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) has been shown

to be a result of dysfunctional mitochondria, which includes

alterations of enzymatic activity, changes in mitochondrial shape

and quantity, and disrupted calcium regulation (136,137). In the NASH disease model,

impaired mitochondria facilitate hepatic lipid accumulation by

promoting ROS production and lipid peroxidation processes (138). High-fat diets over a long period

of time have been shown to cause mitochondrial deformation and

alter the levels of proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics

(139). It was previously shown

that when fatty hepatocytes were co-cultured with BM-MSCs,

mitochondrial transfer was observed through cell-to-cell contact,

which promoted lipolytic activities via enhancing oxidative

capacity and mitochondrial biogenesis (140,141). Mitochondria from BM-MSCs restored

several mitochondrial abnormalities in the hepatocytes of mice fed

a high-fat diet, including MMP, mtDNA copy number, OCR and ATP

levels (140). Functional

mitochondrial-derived BM-MSCs also restored impaired calcium

activity in steatotic cells (140), an effect which is important for

glucose production and lipogenesis (142).

Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is an inflammation

of the pancreas that can lead to mortality. SAP is often linked to

smoking, gallstone disease, alcohol consumption, obesity, diabetes,

and hyperlipidemia (143). The

excessive accumulation of intracellular ROS is associated with

pyroptosis in pancreatic cells during acute inflammation (144). The dysregulation of the mPTP

caused by excessive intracellular calcium levels results in changes

in MMP, which is associated with the progression of SAP (145). The transfer of mitochondria via

extracellular vesicles (EVs) from hypoxia (5%

O2)-treated hUC-MSCs (hypo-EVs) was previously shown to

restore ATP levels and OCR, and to maintain relatively stable MMP

in sodium taurocholate-induced damaged rat pancreatic acinar cells

(PACs) (146). EVs carrying

mitochondria also promoted the normalization of glycolytic activity

in PACs (146).

Allogeneic islet transplantation provides a

promising opportunity for a limited group of patients with type I

diabetes (147). Allogeneic

transplantation of human islets requires short-term cultivation to

ensure safety assessments (148).

However, islet functions are influenced by various environmental

conditions during this period, which may induce oxidative stress

and inflammation (148). The

insulin-secreting ability of pancreatic islet β-cells is associated

with mitochondrial mass and respiratory capacity (149,150). It is also primarily regulated by

mitochondrial ATP production in response to extracellular glucose

levels (150). ADSCs have been

shown to transfer mitochondria through extracellular vesicles to

mouse islet cells exposed to hypoxia (1% oxygen), resulting in

enhanced OCR and insulin secretion of islet cells when stimulated

with 20 mM glucose (151). These

data suggest that mitochondrial transfer can also be used as a

supportive technique in optimizing islet pre-transplantation

conditions.

Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalomyopathy with

lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) is the acronym

for a clinical subgroup of mtDNA diseases affecting several body

systems (152). MELAS is often a

result of point mutations in the mtDNA and is thus inheritable from

the affected mother (152). The

transition from adenine to guanine at nucleotide 3243 in the mtDNA

of the MT-LT1 gene encoding tRNAleu (UUR), is among

the most frequently observed pathogenic mutations in individuals

with MELAS (153). This

alteration leads to the impaired translation and synthesis of ETC

protein subunits, resulting in reduced mitochondrial energy

production (154). Patients with

MELAS have fibroblasts (MELAS fibroblasts) with a high mutation

burden, featuring mitochondrial dysfunction and increased ROS

production (155). It was

previously shown that Wharton's jelly-derived MSCs (WJMSCs)

transferred mitochondria via TNTs into MELAS fibroblasts

pre-treated with rotenone, resulting in an increased protein

expression of the respiratory complexes, which suppressed ROS

production and enhanced MMP (155). Furthermore, this also enhanced

the proliferation of fibroblasts and reduced the expression of

cleaved caspase-3 and TUNEL, thereby suppressing apoptosis

(155). The results of another

study suggested that highly purified MSCs have a greater ability to

transfer mitochondria into MELAS neurons compared to traditional

MSCs (156). Furthermore,

co-culturing with RECs or MSCs significantly enhanced the viability

of MELAS neurons (156).

Myoclonus epilepsy with ragged red fiber syndrome

(MERRF) is a result of a transition from adenine to guanine at

nucleotide 8344 (mt8344A>G) within the mitochondrial

tRNALys coding gene (157). This mutation has been shown to

increase ROS production and oxidative stress, along with

compromised mitochondrial bioenergetics (157). MERRF cybrids, which were created

by fusing ρ0 cells lacking mtDNA with human

platelets in a medium devoid of pyruvate and uridine, were unable

to survive in a galactose-added and glucose-free medium. This

suggests that the mt8344A>G mutation leads to mitochondrial

dysfunction (158). The MERRF

mutation impairs the translation of 13 proteins encoded by mtDNA

and produces abnormal translation products (159). The transfer of mitochondria from

WJMSCs into MERRF cybrids decreases intracellular ROS,

re-establishes MMP, and enables the growth of MERRF cells in

glucose-free environments (158).

In clinical applications, hematopoietic stem cells

(HSCs) were utilized for mitochondrial transplantation into the

HSCs of patients with large-scale mtDNA deletion, such as Pearson

or Kearns-Sayre syndromes (160,161). Recipient HSCs were then infused

back into the patients, improving their quality of life (160,161). This evidence suggests a novel

therapeutic application of mitochondrial transplantation for

currently incurable diseases. While MSCs have not yet been used in

such clinical trials, they can be collected from multiple sources

and easily expanded. Their mitochondria vary in both morphology and

functional capacity, and can be selected to suit HSC biology,

making them a potential source for mitochondrial transplantation

into HSCs for similar cases. Although replacing or supplementing

defective mitochondria in all body systems appears challenging and

warrants further research, mitochondrial transplantation holds

therapeutic potential in mitochondrial pathogenesis.

Stem cell therapies have often been ineffective due

to low cell survival and engraftment (162,163). The excessive production of ROS in

damaged tissues usually decreases the viability of transplanted

MSCs (164). Additionally, MSC

functional characteristics may be compromised with prolonged

isolation and in vitro cultivation, or due to the age of the

donor or disease conditions (165,166). In this context, it has been shown

that healthy hMSCs could donate mitochondria to those pre-treated

with H2O2 through TNT formation (167). The treatment of hMSCs with

mesenchymal stem cell adjuvant has been shown to enhance their

mitochondrial transfer into other

H2O2-induced damaged hMSCs, resulting in a

significant reduction in intracellular ROS levels, maintenance of

MMP, and an increase in TNT length and formation (167). Mitochondrial Drp 1

phosphorylation (Drp1 S616) is involved in mitochondrial fission

and fragmentation (168). It was

previously demonstrated that functional mitochondria derived from

healthy hMSCs reduced mitochondrial fragmentation and Drp1 S616

phosphorylation in damaged hMSCs (167). The mitochondria derived from

ADSCs supplied ATP to fulfill metabolic needs, thereby enhancing

the overall metabolic activity of the recipient ADSCs through

glycolysis (169). Moreover,

ADSCs that received donated mitochondria showed enhanced

proliferation and mobility in serum starvation conditions,

demonstrating enhanced stress tolerance, anti-aging capabilities

and multidirectional differentiation potential in ADSCs treated

with doxorubicin (169). It

should be noted that mitochondria can be artificially introduced

into BM-MSCs in vitro, and within certain limits, the

addition of extracellular mitochondria could enhance the capacity

of the recipient cells to take up more mitochondria (170). Receiving mitochondria also

increases BM-MSC proliferation and migration, promoting cells to

enter the S and G2/M phases, and resisting the replicative

senescence of BM-MSCs (170). In

addition, mitochondrial transfer also enhances the osteogenic

differentiation potential and mitochondrial functions, including

OCR and ATP production in BM-MSCs (170).

A recent study demonstrated that the transfer of

mitochondria from MSCs to endothelial cells, either by direct

cell-to-cell contact or artificial transplantation, significantly

enhanced the engraftment ability of the cells in the in vivo

environment (171). The

stimulation of these effects was shown to be related to mitophagy;

however, the precise mechanism remained unknown. These data

suggested that boosting mitochondrial activity by mitochondrial

transfer and donation can also support cell survival in an in

vivo environment, proposing a potential application for

mitochondrial therapy in cell transplantation technology.

MSCs possess the capacity to modulate immune

responses, particularly those of T-cells, indicating their

therapeutic potential in treating autoimmune disorders, preventing

graft rejection and managing graft vs. host disease (GVHD)

(172). One mechanism of

immunoregulation by MSCs may be attributed to their ability to

transfer mitochondria to immune cells, regulating cell function and

consequent immune outcomes. It was previously demonstrated that

CD3+ T-cells receiving mitochondria from UC-MSCs

increased the expression of CD25 (a factor for T-cell activation)

and FoxP3 [a marker of T-regulatory cell (Treg) differentiation],

compared to CD3+ T-cells not receiving mitochondria from

UC-MSCs (173). Since Tregs

participate in maintaining tolerance and preventing autoimmunity,

they are involved in various pathological conditions, including

GVHD (174). Treg cell

differentiation induced by mitochondria transferred from UC-MSCs

enhanced the ability to inhibit the proliferation of peripheral

blood mononuclear cells (173).

As previously demonstrated, mitochondrial transfer also markedly

improved the survival rate of mice with GVHD, while decreasing

tissue inflammation (173). The

key strategy employed by Tregs to preserve immune homeostasis is

the inhibition of conventional T-cell (Tconv) proliferation

(175). A previous study

demonstrated that ADSCs transferred mitochondria to Tregs during

co-culture, 85% of which remained functional, allowing Tregs to

efficiently inhibit the proliferation of Tconvs (176). The insufficient presence of HLA

class II antigens on ASCs restricted the uptake of mitochondria by

>80% (176). Thus,

mitochondrial transfer from MSCs supports T-cells in regulating

uncontrolled immunity.

Diabetes mellitus is chiefly characterized by

increased macrophage infiltration in the kidneys. Implementing

strategies to prevent the pro-inflammatory (M1) phenotype or to

shift them to an anti-inflammatory (M2) state has been proposed to

help reduce kidney injury in diabetic mice (180). Metabolic and physiological

changes in mitochondria are essential for regulating macrophage

polarization, proliferation and survival (181). While M1 macrophages utilize

glycolysis for energy, M2 macrophages depend on mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation (182,183). Mitochondrial dysfunction in

macrophages derived from diabetic mice has been shown to lead to M1

polarization and resulted in subsequent inflammation (184). In that context, in another study,

mitochondria transferred from MSCs to RAW264.7 macrophages

pre-treated with high glucose helped the cells to reduce ROS

production and restore MMP and ATP levels by regulating gene

expression of the glycolytic and citric acid cycles (185). RAW264.7 macrophages induced by

high glucose that took up mitochondria exhibited lower levels of

cytokine secretion, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, two cytokines which

are critical for mitigating inflammation (185).

Alveolar macrophages (AMs), found in the lung lumen

adjacent to the epithelium, function to phagocytose debris and help

resolve inflammation (186).

Dysfunctional AMs with an irregular mitochondrial function

frequently contribute to severe inflammation in the lungs (186). It has been shown that MSCs

transferring mitochondria to macrophages can enhance their

phagocytosis, which may uncover a mechanism behind the

antimicrobial effects of BM-MSCs (187). Furthermore, mitochondrial

transfer from MSCs can boost the anti-inflammatory and

antibacterial functions of macrophages by promoting their

differentiation into the M2 phenotype (188). As previously demonstrated, when

MSCs and primary human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) were

co-cultured for 4 h, the mitochondrial transfer from BM-MSCs

through TNTs enhanced the ability of macrophages to kill up to 80%

of extracellular Escherichia coli bacteria (187). Notably, macrophages co-cultured

with MSCs exhibited a substantial and consistent enhancement of

both OCR and ATP production (187). This was consistent with a report

that macrophages receiving mitochondria from exosomes secreted by

MSCs in the co-culture settings significantly increased OCR and

reduced proton leak (189). This

functioned as a survival strategy in response to oxidative stress,

where donated mitochondria were re-utilized through a fusion

process to enhance the bioenergetics of macrophages (189). Exosomes derived from ADSCs could

transfer mitochondrial components to murine alveolar macrophages,

which then fused with the macrophage mitochondria (190). Murine alveolar macrophages in

acute lung injury exhibited an increased number of mitochondria,

improved mitochondrial morphology, and increased membrane potential

after receiving mitochondria from ADSCs (190). Moreover, mitochondria played a

critical role in the metabolic programming of immune cells and in

reshaping cellular phenotypes and function (191). The transfer of mitochondria via

ADSC-derived exosomes caused LPS-stimulated macrophages to

transition from a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to an

anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype (190). Furthermore, mitochondria have

been shown to be transferred from MSCs to macrophages via EVs,

which boosted oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), leading to

enhanced phagocytosis of macrophages (192). These data demonstrate that MSCs

employ multiple mechanisms to transfer mitochondria to immune

cells, which often have high mobility in circulation. Thus,

questions regarding the driving factors for mitochondrial transfer

from MSCs to immune cells warrant future research, potentially

opening a potential opportunity for therapeutic application.

The reproductive system consists of various organs

and structures that are distinct in males and females. Different

cell compartments in the reproductive system are responsible for

specific functions that support the formation and production of

offspring. The two key cell types directly responsible for

fertilization are sperm and eggs. While mitochondria are crucial

for sperm maturation, survival, and mobility, oocyte mitochondria

are critical for fertilization and embryonic development, which are

also majorly inherited by the fetus (193). Thus, both mtDNA content and

mitochondrial function are essential for successful fertilization,

pregnancy and live births. Mitochondria in oocytes produce energy

mainly via OXPHOS, as glycolysis is only unblocked at the early

stage of blastocyst formation. ATP production is associated with

egg quality, as aged and poor-quality eggs have significantly lower

mtDNA content and produce much less ATP compared to normal and

healthy oocytes (194). This

could potentially result in low or no fertilization (195,196). Aging is one of the major

contributing factors to reduced female fertility, as it directly

affects mtDNA replication and mutation, and changes mitochondrial

metabolism (197).

Mitochondria can be isolated from healthy donors

and directly injected into the eggs or embryos of unhealthy

individuals who may carry mutations interfering with mitochondrial

function. The technology is effective in supplementing oocytes with

healthy mitochondria to improve oocyte quality and fertilization

rate, and to increase chances of live births and offspring with

normal phenotypes, providing hope to infertile women and those with

inherited diseases (198).

Multiple studies have been conducted on both animal and human

models, aiming to examine the applicability of mitochondria

isolated from various cell types to identify the most suitable

source of mitochondria specifically for oocyte improvement; a

number of these sources were from MSCs of different origins. Even

though the current technology focuses on the autologous grafting of

mitochondria due to concerns about mtDNA and nuclear DNA mismatch

(199), the therapy has yielded

positive results in assisting cases of aged and low-quality

oocytes. For example, in animal models, for instance, the

mitochondria isolated from MSCs derived from UC-MSCs were directly

injected into metaphase I oocytes of aged mice, which consequently

resulted in improved mitochondrial function and development of

early embryos (200). On the

other hand, mitochondria derived from ADSCs were shown to be

effective in improving oocyte competence, fertilization rate, and

blastocyst development in both aged-MII and cryopreserved oocytes

(201,202). MSCs (EnMSCs) were also a source

of cells that have been tested in mice. The increase in oocyte

quality and maturation associated with an enhanced birth rate and

embryonic development suggested that mitochondrial transfer from

EnMSCs was effective in rescuing infertility due to the poor

quality of germinal vesicle oocytes (203). Additionally, mitochondria

isolated from iPSCs were also shown to be a good source for

mitochondrial transfer due to their compatibility with the

mitochondrial morphology in oocytes and embryos (204). Furthermore, advancements have

been made to bring the technology of mitochondrial therapy to

humans. Particularly, mitochondria from urine-derived MSCs and

oogonial stem cells were isolated for use in aged human oocytes.

The results revealed an improvement in pregnancy rates, embryonic

development and live birth rates (205-209).

These data highlight the promising potential of mitochondrial

transplantation technology in supporting the reproductive system,

particularly in addressing female infertility. Future research is

also anticipated to advance mitochondrial therapy in the male

reproductive system.

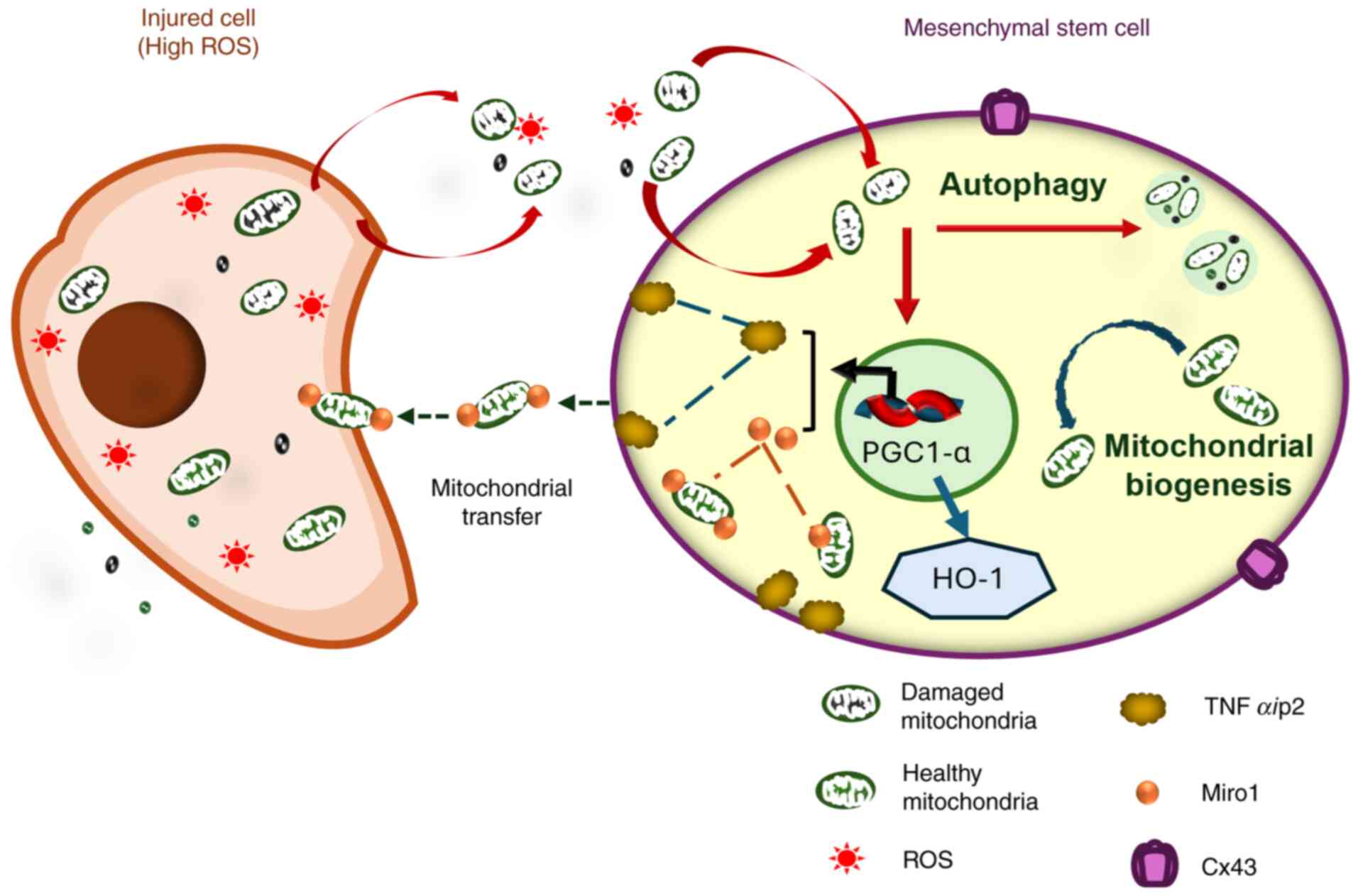

The molecular mechanism of TNT formation involves

Miro1, an outer mitochondrial membrane protein essential for

mitochondrial transport and donation (217,218). Following the increased levels of

Miro1 induced by oxidative stress, MSCs enhance their capacity for

mitochondrial transfer through TNTs (47,55,88,219). Miro1 deletion has been

proven to inhibit MSC mitochondrial transfer and impair the

microtubule movement of donated mitochondria (217,218). It should be noted that the

expression of Miro1 and TNFαip2 are interrelated in

mitochondrial transfer (219).

TNFαip2 is a marker of TNT formation that regulates

intercellular interactions (114). TNF-α-induced oxidative stress

causes significantly high TNFαip2 expression (220). When TNFαip2 is deleted in

MSCs, the overexpression of Miro1 also decreases

mitochondrial transfer, and the control of ROS levels is impaired

both in vitro and in vivo (217). NF-κB and TNFαip2

overexpression increase ROS levels, which subsequently leads to

TNTs formation, and NAC reverses this process by reducing ROS

(47,114,221). Furthermore, there is an

association between the phosphorylation of NF-κB and TNT

formation inhibition (114,221,222). The expression of TNFαip2

is directly related to mitochondrial transfer capacity between

cells through TNTs (219,220). The N- and C-terminal region of

the TNFaip2 protein have different contributions to the remodeling

of the MSC's plasma membrane to form TNTs (223).

Additionally, after receiving stimulation from

injured cell signals, MSCs also promote cell-to-cell interactions

and mitochondrial transfer capacity. Connexin 43 (Cx43) has been

shown to be related to the transfer of mitochondria between cells

(63,224). ROS overproduction caused by LPS

in injured cells promotes the mitochondrial transfer from MSCs

through Cx43 regulation (214).

Cx43 knockdown in MSCs interrupts the mitochondrial transfer from

MSCs to injured chondrocytes (63,225). In the event that MSCs upregulate

Cx43 expression by iron oxide nanoparticles, the mitochondrial

transfer ability of MSCs will be enhanced (226). On the other hand, various

mechanisms can be utilized by other cells, particularly cancer

cells, to steal mitochondria from their neighboring cells in the

microenvironment (227-231);

however, these mechanisms have not been implicated in the

MSC-mediated mitochondrial rescue pathway. Questions remain as to

whether these mechanisms exist between MSCs and other cells.

There are two separate fates for donated exogenous

mitochondria once internalized inside recipient cells: Integration

into the host mitochondrial network or degradation through

mitophagy and autophagy processes. Within the host cells, exogenous

mitochondria can fuse with the host mitochondrial network, and this

fusion can occur via different mechanisms across various types of

cells (232-234).

This process is associated with the expression of mitofusin (MNF)1,

MNF2 and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) (235). Under oxidative stress conditions,

cells downregulate the expression of these mitochondrial fusion

proteins, particularly MFN1 and OPA1(232). In the majority of cases, this

downregulation is affected by the presence of exogenous

mitochondria. A previous study demonstrated that following

exogenous mitochondrial transplantation, the recipient cells

contained nearly 12% mtDNA from donor cells after 24 h (171). Notably, this exogenous mtDNA

cannot be detected on day 7. Lysosomes of host cells degrade parts

of exogenous mitochondria (232,233,235). On the other hand, it has been

shown that at ~6-12 h following transplantation, exogenous

mitochondria enter the autophagy process in host cells (171). There is evidence to indicate that

donated mitochondria from MSCs inside endothelial cells undergo

mitophagy mediated by the PINK1-Parkin pathway, which facilitates

biogenesis in the recipient cells and enhances their engraftment

in vivo (171). Future

research is warranted to elucidate the precise mechanisms through

which host cells take up and regulate the use of exogenous

mitochondria within their cytoplasm.

Mitochondrial transfer and transplantation appear

to be an innovative and promising tool for targeting

mitochondria-related pathological conditions (25,236-238).

However, identifying a qualified and ready-to-use source of

mitochondria has been a challenge for clinical translation.

Difficulties in obtaining mitochondrial sources can limit the

reproducibility of the approach, increase the need for invasive

procedures in patients, and hinder the quality control of the

transplanted mitochondria. In clinical trials, ready-to-use

mitochondria may help to improve the feasibility and efficacy of

their application, ensuring timely treatment (239). A recent study demonstrated that

storable human mitochondria, as a ready source of exogenous

mitochondria, are effective in a mouse model of Leigh syndrome

(240). Thus, a stable and

quality source of mitochondria is key to the success of

mitochondrial transplantation. In this context, MSCs have emerged

as potential donors of mitochondria in mitochondrial therapy, and

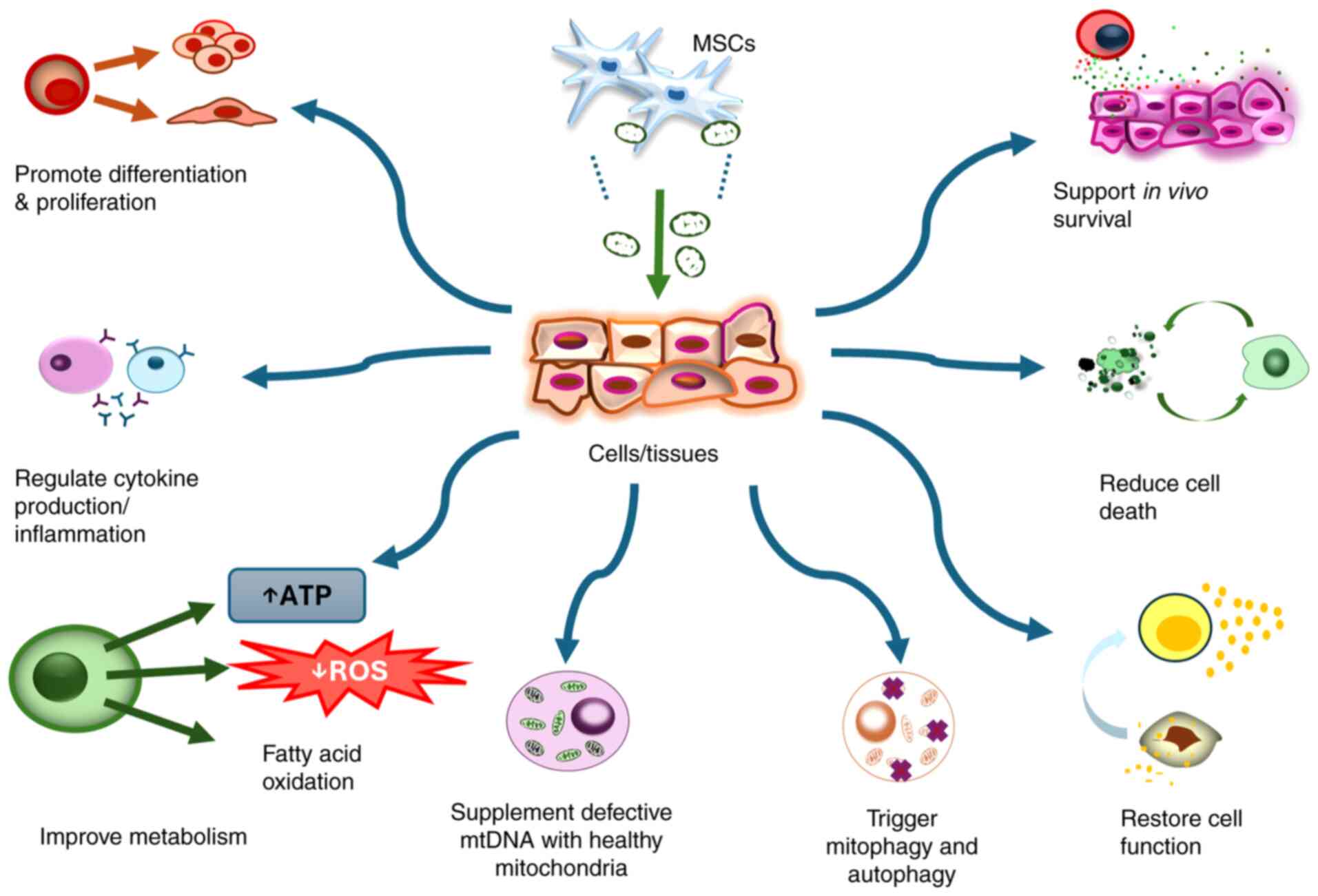

preclinical data indicate that their use is effective across a

range of cell types, diseases and conditions. A summary of

recipient cell types receiving mitochondrial transfer from MSCs is

presented in Table I. However,

although the exact mechanisms underlying tissue regeneration

through mitochondrial transfer are not yet fully understood, it is

proposed to involve several rescuing effects (Fig. 4).

Despite this promising application, it should be

noted that mitochondrial transfer and transplantation may also pose

significant health risks in the case of misuse. Mitochondrial

therapy, whether utilizing mitochondria from MSCs or other cell

types (both autologous or allogenic), may encounter various

challenges, including the acceleration of the immune response and

the promotion of tumor metastasis (241-243).

For instance, allogenic mtDNA has been shown to accelerate the

innate immune response in mice (244), and even in cases of autologous

transplantation, an mtDNA mutation in the cells of the donor could

elicit an immune response that is dependent on host major

histocompatibility complex (245). Although allogenic mitochondrial

transplantation has been shown in several studies, it is important

to understand the mechanism and effects of the treatment, and

screening for mtDNA is crucial to ensure safety in clinical

applications. In addition, several ethical questions have also been

raised, primarily in the field of assisted reproductive technology,

concerning the retention of exogenous mitochondria and the

potential for mtDNA/nuclear DNA mismatch within host cells

(243,246,247). Given the relevance of these

issues in other clinical applications, further research is required

to clarify the mechanisms of exogenous mitochondrial interaction

with the host cells and determine the effective dosages for

different cases. Furthermore, optimizing the procedures and routes

of application for specific pathological conditions is crucial to

enhance the accessibility of this technique in diverse clinical

settings.

Although challenges persist, progress has been

achieved to improve the safety and broad application of

mitochondrial transfer and transplantation. Firstly, research has

focused on optimizing the cellular uptake of exogenous mitochondria

through various techniques of artificial transplantation (Fig. 1B). These technologies focus on

improving mitochondrial permeabilization across the cell membranes

by utilizing both mechanical forces and penetrating peptides. While

none of these methods are currently suitable for clinical

application, ongoing efforts are focused on refining existing

techniques and developing new materials and technologies. Current

approaches, however, have successfully achieved mitochondrial

transplantation into isolated cells. This success holds promise for

improving cell function in therapeutic areas, such as stem cell and

immune cell therapies. Furthermore, research is being conducted to

understand the mechanism of intercellular mitochondrial transfer,

aiming to enhance the rescue of damaged cells in in vivo

settings (248). For instance,

stimulating mitochondrial transfer from MSCs, such as enhancing the

formation of TNT, increasing the secretion of EVs, and promoting

cell fusion, could be advantageous for multiple applications. Most

importantly, future research is required to verify the

effectiveness of different stem cell types and their culture

conditions, while clarifying and defining appropriate mitochondrial

quality measures. With the current progress, it is expected that

MSCs will provide a cell source for mitochondrial transplantation,

offering a new approach to regenerative medicine and adding an

essential element to stem cell therapy.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

CMT was involved in the conceptualization of the

study, in the preparation of the figures, and in the writing of the

original draft of the manuscript. VTTN was involved in the

conceptualization of the study, in the preparation of the figures

visualization, in the writing of the original draft of the

manuscript, and in the writing, reviewing and editing of the

manuscript. Both authors have read and confirmed the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

|

1

|

Amorim JA, Coppotelli G, Rolo AP, Palmeira

CM, Ross JM and Sinclair DA: Mitochondrial and metabolic

dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

18:243–258. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hyatt H, Deminice R, Yoshihara T and

Powers SK: Mitochondrial dysfunction induces muscle atrophy during

prolonged inactivity: A review of the causes and effects. Arch

Biochem Biophys. 662:49–60. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Dagda RK: Role of mitochondrial

dysfunction in degenerative brain diseases, an overview. Brain Sci.

8(178)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kaarniranta K, Uusitalo H, Blasiak J,

Felszeghy S, Kannan R, Kauppinen A, Salminen A, Sinha D and

Ferrington D: Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction and their

impact on age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res.

79(100858)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zilio E, Piano V and Wirth B:

Mitochondrial dysfunction in spinal muscular atrophy. Int J Mol

Sci. 23(10878)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Weiss SL, Zhang D, Bush J, Graham K, Starr

J, Murray J, Tuluc F, Henrickson S, Deutschman CS, Becker L, et al:

Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with an immune paralysis

phenotype in pediatric sepsis. Shock. 54:285–293. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

McBride MA, Owen AM, Stothers CL,

Hernandez A, Luan L, Burelbach KR, Patil TK, Bohannon JK, Sherwood

ER and Patil NK: The metabolic basis of immune dysfunction

following sepsis and trauma. Front Immunol. 11(1043)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Prasun P: Mitochondrial dysfunction in

metabolic syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1866(165838)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Bhatti JS, Bhatti GK and Reddy PH:

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in metabolic

disorders-a step towards mitochondria based therapeutic strategies.

Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1863:1066–1077. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Montgomery MK: Mitochondrial dysfunction

and diabetes: Is mitochondrial transfer a friend or foe? Biology

(Basel). 8(33)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Feichtinger RG, Sperl W, Bauer JW and

Kofler B: Mitochondrial dysfunction: A neglected component of skin

diseases. Exp Dermatol. 23:607–614. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Mizumura K, Cloonan SM, Nakahira K,

Bhashyam AR, Cervo M, Kitada T, Glass K, Owen CA, Mahmood A, Washko

GR, et al: Mitophagy-dependent necroptosis contributes to the

pathogenesis of COPD. J Clin Invest. 124:3987–4003. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Li X, Zhang W, Cao Q, Wang Z, Zhao M, Xu L

and Zhuang Q: Mitochondrial dysfunction in fibrotic diseases. Cell

Death Discov. 6(80)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ryter SW, Rosas IO, Owen CA, Martinez FJ,

Choi ME, Lee CG, Elias JA and Choi AMK: Mitochondrial dysfunction

as a pathogenic mediator of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 15 (Suppl

4):S266–S272. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kandasamy J, Olave N, Ballinger SW and

Ambalavanan N: Vascular endothelial mitochondrial function predicts

death or pulmonary outcomes in preterm infants. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med. 196:1040–1049. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Rizzuto R, De Stefani D, Raffaello A and

Mammucari C: Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium

signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 13:566–578. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Matuz-Mares D, González-Andrade M,

Araiza-Villanueva MG, Vilchis-Landeros MM and Vázquez-Meza H:

Mitochondrial calcium: Effects of its imbalance in disease.

Antioxidants (Basel). 11(801)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Belosludtsev KN, Talanov EY, Starinets VS,

Agafonov AV, Dubinin MV and Belosludtseva NV: Transport of

Ca2+ and Ca2+-dependent permeability

transition in rat liver mitochondria under the

streptozotocin-induced type I diabetes. Cells.

8(1014)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Sundaramoorthy P, Sim JJ, Jang YS, Mishra

SK, Jeong KY, Mander P, Chul OB, Shim WS, Oh SH, Nam KY and Kim HM:

Modulation of intracellular calcium levels by calcium lactate

affects colon cancer cell motility through calcium-dependent

calpain. PLoS One. 10(e0116984)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Spees JL, Olson SD, Whitney MJ and Prockop

DJ: Mitochondrial transfer between cells can rescue aerobic

respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:1283–1288. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Rodriguez AM, Nakhle J, Griessinger E and

Vignais ML: Intercellular mitochondria trafficking highlighting the

dual role of mesenchymal stem cells as both sensors and rescuers of

tissue injury. Cell Cycle. 17:712–721. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Plotnikov EY, Babenko VA, Silachev DN,

Zorova LD, Khryapenkova TG, Savchenko ES, Pevzner IB and Zorov DB:

Intercellular transfer of mitochondria. Biochemistry (Mosc).

80:542–548. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hayashida K, Takegawa R, Shoaib M, Aoki T,

Choudhary RC, Kuschner CE, Nishikimi M, Miyara SJ, Rolston DM,

Guevara S, et al: Mitochondrial transplantation therapy for

ischemia reperfusion injury: A systematic review of animal and

human studies. J Transl Med. 19(214)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yang C, Yokomori R, Chua LH, Tan SH, Tan

DQ, Miharada K, Sanda T and Suda T: Mitochondria transfer mediates

stress erythropoiesis by altering the bioenergetic profiles of

early erythroblasts through CD47. J Exp Med.

219(e20220685)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Liu D, Gao Y, Liu J, Huang Y, Yin J, Feng

Y, Shi L, Meloni BP, Zhang C, Zheng M and Gao J: Intercellular

mitochondrial transfer as a means of tissue revitalization. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 6(65)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Emani SM, Piekarski BL, Harrild D, Del

Nido PJ and McCully JD: Autologous mitochondrial transplantation

for dysfunction after ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac

Cardiovasc Surg. 154:286–289. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Guariento A, Piekarski BL, Doulamis IP,

Blitzer D, Ferraro AM, Harrild DM, Zurakowski D, Del Nido PJ,

McCully JD and Emani SM: Autologous mitochondrial transplantation

for cardiogenic shock in pediatric patients following

ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.

162:992–1001. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Michaeloudes C, Li X, Mak JCW and Bhavsar

PK: Study of mesenchymal stem cell-mediated mitochondrial transfer

in in vitro models of oxidant-mediated airway epithelial and smooth

muscle cell injury. Methods Mol Biol. 2269:93–105. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Konari N, Nagaishi K, Kikuchi S and

Fujimiya M: Mitochondria transfer from mesenchymal stem cells

structurally and functionally repairs renal proximal tubular

epithelial cells in diabetic nephropathy in vivo. Sci Rep.

9(5184)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Moschoi R, Imbert V, Nebout M, Chiche J,

Mary D, Prebet T, Saland E, Castellano R, Pouyet L, Collette Y, et

al: Protective mitochondrial transfer from bone marrow stromal

cells to acute myeloid leukemic cells during chemotherapy. Blood.

128:253–264. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Lambrecht BN and Hammad H: The immunology

of asthma. Nat Immunol. 16:45–56. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Chan TK, Tan WSD, Peh HY and Wong WSF:

Aeroallergens induce reactive oxygen species production and DNA

damage and dampen antioxidant responses in bronchial epithelial

cells. J Immunol. 199:39–47. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhao L, Gao J, Chen G, Huang C, Kong W,

Feng Y and Zhen G: Mitochondria dysfunction in airway epithelial

cells is associated with type 2-low asthma. Front Genet.

14(1186317)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Yao Y, Fan XL, Jiang D, Zhang Y, Li X, Xu

ZB, Fang SB, Chiu S, Tse HF, Lian Q and Fu QL: Connexin 43-mediated

mitochondrial transfer of iPSC-MSCs alleviates asthma inflammation.

Stem Cell Reports. 11:1120–1135. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Malsin ES and Kamp DW: The mitochondria in

lung fibrosis: Friend or foe? Transl Res. 202:1–23. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Takahashi M, Mizumura K, Gon Y, Shimizu T,

Kozu Y, Shikano S, Iida Y, Hikichi M, Okamoto S, Tsuya K, et al:

Iron-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the

pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Front Pharmacol.

12(643980)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Huang T, Lin R, Su Y, Sun H, Zheng X,

Zhang J, Lu X, Zhao B, Jiang X, Huang L, et al: Efficient

intervention for pulmonary fibrosis via mitochondrial transfer

promoted by mitochondrial biogenesis. Nat Commun.

14(5781)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Li CL, Liu JF and Liu SF: Mitochondrial

dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Unraveling

the molecular nexus. Biomedicines. 12(814)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Canton M, Sánchez-Rodríguez R, Spera I,

Venegas FC, Favia M, Viola A and Castegna A: Reactive oxygen

species in macrophages: Sources and targets. Front Immunol.

12(734229)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Aridgides DS, Mellinger DL, Armstrong DA,

Hazlett HF, Dessaint JA, Hampton TH, Atkins GT, Carroll JL and

Ashare A: Functional and metabolic impairment in cigarette

smoke-exposed macrophages is tied to oxidative stress. Sci Rep.

9(9624)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Tulen CBM, Wang Y, Beentjes D, Jessen PJJ,

Ninaber DK, Reynaert NL, van Schooten FJ, Opperhuizen A, Hiemstra

PS and Remels AHV: Dysregulated mitochondrial metabolism upon

cigarette smoke exposure in various human bronchial epithelial cell

models. Dis Model Mech. 15(dmm049247)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Li X, Michaeloudes C, Zhang Y, Wiegman CH,

Adcock IM, Lian Q, Mak JCW, Bhavsar PK and Chung KF: Mesenchymal

stem cells alleviate oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial

dysfunction in the airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

141:1634–1645.e5. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Li X, Zhang Y, Yeung SC, Liang Y, Liang X,

Ding Y, Ip MS, Tse HF, Mak JC and Lian Q: Mitochondrial transfer of

induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells to

airway epithelial cells attenuates cigarette smoke-induced damage.

Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 51:455–465. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Wu BB, Leung KT and Poon EN:

Mitochondrial-targeted therapy for doxorubicin-induced

cardiotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 23(1912)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

He H, Wang L, Qiao Y, Zhou Q, Li H, Chen

S, Yin D, Huang Q and He M: Doxorubicin induces endotheliotoxicity

and mitochondrial dysfunction via ROS/eNOS/NO pathway. Front

Pharmacol. 10(1531)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Tang H, Tao A, Song J, Liu Q, Wang H and

Rui T: Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis: Role of

mitofusin 2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 88:55–59. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Zhang Y, Yu Z, Jiang D, Liang X, Liao S,

Zhang Z, Yue W, Li X, Chiu SM, Chai YH, et al: iPSC-MSCs with high

intrinsic MIRO1 and sensitivity to TNF-α yield efficacious

mitochondrial transfer to rescue anthracycline-induced

cardiomyopathy. Stem Cell Reports. 7:749–763. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Jin N, Zhang M, Zhou L, Jin S, Cheng H, Li

X, Shi Y, Xiang T, Zhang Z, Liu Z, et al: Mitochondria

transplantation alleviates cardiomyocytes apoptosis through

inhibiting AMPKα-mTOR mediated excessive autophagy. FASEB J.

38(e23655)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Tanaka-Esposito C, Chen Q and Lesnefsky

EJ: Blockade of electron transport before ischemia protects

mitochondria and decreases myocardial injury during reperfusion in

aged rat hearts. Transl Res. 160:207–216. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Huang J, Li R and Wang C: The role of

mitochondrial quality control in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion

injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021(5543452)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Bouhamida E, Morciano G, Perrone M, Kahsay

AE, Della Sala M, Wieckowski MR, Fiorica F, Pinton P, Giorgi C and

Patergnani S: The interplay of hypoxia signaling on mitochondrial

dysfunction and inflammation in cardiovascular diseases and cancer:

From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic approaches. Biology

(Basel). 11(300)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Cselenyák A, Pankotai E, Horváth EM, Kiss

L and Lacza Z: Mesenchymal stem cells rescue cardiomyoblasts from

cell death in an in vitro ischemia model via direct cell-to-cell

connections. BMC Cell Biol. 11(29)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Han H, Hu J, Yan Q, Zhu J, Zhu Z, Chen Y,

Sun J and Zhang R: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells

rescue injured H9c2 cells via transferring intact mitochondria

through tunneling nanotubes in an in vitro simulated

ischemia/reperfusion model. Mol Med Rep. 13:1517–1524.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|