Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), accounting for

~90% of oral cancer cases, and poses a global health challenge with

a 5-year survival rate of 35-50%, primarily due to late diagnosis

driven by non-specific symptoms and invasive diagnostics (1,2).

Fanconi anemia (FA), a rare genetic disorder affecting 1 in 130,000

individuals, markedly increases susceptibility to squamous cell

carcinomas (SCC), with OSCC among the most prevalent, exhibiting a

500-700-fold elevated risk, often at younger ages (3,4).

This necessitates robust surveillance strategies that are

sensitive, comprehensive and sustainable for high-risk patients

with FA (5). Non-invasive

biomarkers, such as microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) and proteins, enable

patient-friendly monitoring through biofluids, such as saliva and

serum, thereby enhancing early detection (6).

miR-34a, a potent tumor suppressor, regulates the

Wnt and PI3K pathways by targeting genes [e.g., Wnt family member 1

(WNT1), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and baculoviral IAP

repeat containing 5 (BIRC5)] and promotes apoptosis (7). However, the downregulation of its

expression has been reported in SCCs (head and neck, lung and

cervical) and other types of cancer (leukemia and glioma), with

this being associated with tumor progression (8). Survivin, an apoptosis inhibitor,

suppresses caspase 3/9 activity and is overexpressed in OSCC, head

and neck SCC, and cancers such as lung and gastric cancer, is

detectable in serum and saliva, and is linked to an aggressive

tumor behavior (9). Despite their

established roles in SCCs, the combined utility of salivary miR-34a

and serum survivin for OSCC surveillance in FA remains

underexplored, particularly in a comparative setting with patients

with OSCC and healthy controls. Thus, the present pilot study

evaluated these biomarkers in patients with FA (n=24), patients

with OSCC (n=24) and healthy controls (n=40) cohorts to establish

non-invasive tools for early detection of OSCC in FA, aiming to

improve clinical outcomes in this high-risk population.

Patients and methods

Study population

The present study included 24 patients with OSCC

(mean age, 54.52±10.49 years; 58.3% male; TNM stages I-IV), 24

patients with FA (mean age, 20.03±5.87 years; 58.3% male) and 40

healthy controls (mean age, 42.23±10.22 years, 50% male). OSCC was

diagnosed via histopathological biopsy, and FA was confirmed by

chromosomal breakage tests (using mitomycin C and diepoxybutane

tests). Genetic analysis for specific germline mutations (e.g.,

FANCA and FANCC) was not performed in the present study due to

resource limitations.

Exclusion criteria included other malignancies,

autoimmune disorders, or recent infections. The patients with FA

had no history of OSCC at the time of sampling. The demographic

characteristics of the study participants (age, sex, oral hygiene

and oral lesions) are presented in Table I.

| Table IDemographic characteristics of

patients with OSCC ad FA, and the controls. |

Table I

Demographic characteristics of

patients with OSCC ad FA, and the controls.

| Feature | Patients with OSCC

(n=24) | Patients with FA

(n=24) | Control group

(n=40) |

|---|

| Age range, years | 31-67 | 14-32 | 25-53 |

| Age, years (mean ±

SD) | 54.52±10.49 | 20.03±5.87 | 42.13±10.92 |

| Sex, n (%) | | | |

|

Male | 14 (58.3) | 14 (58.3) | 20(50) |

|

Female | 10 (41.7) | 10 (41.6) | 20(50) |

| Oral hygiene | | | |

|

Poor | 10 (41.6) | 14 | 21(55) |

|

Good | 14 (58.3) | 10 | 19(45) |

| Oral lesions | | | |

|

Present | 19 (79.1) | 9 (37.5) | 14(20) |

|

Absent | 5 (20.9) | 15 (67.5%) | 26(80) |

Ethical approval and consent

The present study was approved by the Istanbul

University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Approval no. 1307,

November 13, 2019) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants, with parental consent being obtained for those <18

years of age.

Sample collection

Saliva (4 ml) and serum (6 ml in EDTA tubes) were

collected under standardized conditions. Saliva was centrifuged at

3,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C to remove debris, and serum was

separated at 1,500 x g for 10 min at 4˚C. Supernatants were stored

at -80˚C until analysis.

miRNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Salivary miRNA was extracted using the miRNeasy Mini

kit (Qiagen GmbH). RNA purity and concentration were verified using

a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (A260/A280 ratio: 1.8-2.0). cDNA was

synthesized using the miRCURY LNA RT kit (Qiagen GmbH).

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using SYBR-Green Master Mix

(Qiagen GmbH) on a LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics) under the

following cycling conditions: Initial activation at 95˚C for 2 min,

followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 10 sec and

annealing/extension at 56˚C for 60 sec, and a melt curve analysis

from 65˚C to 95˚C.Primers for hsa-miR-34a-5p (forward,

5'-GCAGTGGCAGTGTCTTAG-3'; reverse,

5´-GGTCCAGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTACAAC-3') and U6 snRNA (human; forward,

5'-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3'; reverse, 5' AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCT-3' were

purchased from Qiagen GmbH. Relative expression levels were

calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method (10).

Protein analysis

Serum survivin levels were quantified using a

commercial ELISA kit (Cat. No: E3904Hu, Human Survivin ELISA kit,

BT-Lab). Standard curves were generated according to the

manufacturer's instructions, and the optical density was measured

at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk

test for continuous variables (age, salivary miR-34a expression and

serum survivin levels). Age satisfied the normality assumption

(Shapiro-Wilk, P=0.37) and data were compared between groups using

one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni correction for post hoc pairwise

comparisons. Salivary miR-34a and serum survivin distributions

deviated from normality (Shapiro-Wilk, P<0.05) and are therefore

are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Group

comparisons for these biomarkers were performed using the

Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn's post hoc test for multiple

comparisons. Categorical variables were compared using the

Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. All

correlation analyses were performed using Spearman's rank

correlation. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were

performed to calculate the area under the curve (AUC), 95%

confidence intervals (CIs), cut-off values, sensitivity and

specificity. All tests were two-sided, and a value of P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v25 (IBM Corp.).

Results

Demographic and clinical

characteristics of the study participants

The present study comprised 24 patients with OSCC

(mean age, 54.52±10.7 years; 58.3% male), 24 patients with FA (mean

age, 20.03±5.87 years; 58.3% male) and 40 healthy controls (mean

age, 42.13±10.92 years; 50% male). Age followed a normal

distribution (Shapiro-Wilk, P=0.37), while salivary miR-34a and

serum survivin did not (Shapiro-Wilk, P<0.05). Therefore,

non-parametric tests were applied for these biomarkers. Sex

distribution was also comparable (P>0.05). The demographic

characteristics of the patient and control groups are summarized in

Table I.

miR-34a expression levels

As salivary miR-34a and serum survivin values

deviated from normality (Shapiro-Wilk, P<0.05), they are

presented as the median (IQR) and were compared using the

Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's post-hoc (Table II). Salivary miR-34a expression,

quantified using RT-qPCR with the 2-ΔΔCq method with U6

normalization, was significantly lower in the patients with OSCC

[median (IQR), 1.33 (0.68-3.69); P=0.012] and FA [median (IQR),

0.72 (0.05-3.19); P=0.014] compared to the controls [median (IQR),

3.63 (0.32-14.77)]. No significant difference was observed between

the OSCC and FA (P=0.78) groups. These results are presented in

Fig. 1 and Table II.

| Table IImiR-34a and survivin levels in the

OSCC, FA and control groups. |

Table II

miR-34a and survivin levels in the

OSCC, FA and control groups.

| Group | miR-34a

(2-ΔΔCq) median (IQR) | P-value vs.

control | Survivin (ng/ml)

median (IQR) | P-value vs.

control |

|---|

| OSCC (n=24) | 1.33 (0.68-3.69) | 0.012 | 196.19

(165.83-298.75) | 0.01 |

| FA (n=24) | 0.72 (0.05-3.19) | 0.014 | 216.38

(102.89-858.87) | 0.001 |

| Control (n=40) | 3.63

(0.32-14.77) | | 121.90

(103.85-182.03) | |

In the patients OSCC, the miR-34a levels tended to

be lower in those with advanced tumor stages (T3-T4) and lymph node

metastasis; however, these associations were not statistically

significant (P=0.34 and P=0.87, respectively; Table III). No significant associations

were found with other clinical parameters, including depth of

invasion, differentiation, or treatment response (P>0.05;

Table III).

| Table IIIAssociation of miR-34a and survivin

expression with clinicopathological features of patients with

OSCC. |

Table III

Association of miR-34a and survivin

expression with clinicopathological features of patients with

OSCC.

| | | miR-34a | Survivin |

|---|

| Clinical

characteristics of patients with OSCC | No. of patients

(%) | High expression | Low expression | P-value | High expression | Low expression | P-value |

|---|

| Tumor size | | | | | | | 0.31 |

|

<2

cm | 3 (12.5) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | |

|

2-3 cm | 15 (62.5) | 4 (26.6) | 11 (73.3) | | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) | |

|

>4

cm | 6(25) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 0.08 | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Tumor stage | | | | | | | 0.23 |

|

T1, T2 | 11 (45.8) | 3 (37.5) | 8 (62.5) | | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | |

|

T3, T4 | 13 (54.2) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | 0.34 | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | | | | | 0.72 |

|

Present | 9 (37.5) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.7) | 0.87 | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | |

|

Absent | 15 (62.5) | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Degree of

differentiation | | | | | | | 0.84 |

|

Poor | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 2(100) | | 1(50) | 1(50) | |

|

Moderate | 17 (70.9) | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | 1.56 | 10 (58.8) | 7 (29.2) | |

|

Well | 5 (20.8) | 1(20) | 4(80) | | 3(60) | 2(40) | |

| Depth of

invasion | | | | | | | 0.95 |

|

<10

mm | 8 (33.3) | 4(50) | 4(50) | | 8(100) | 0 (0) | |

|

>10mm | 16 (66.7) | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.7) | 0.058 | 4(25) | 12(75) | |

| Perineural

invasion | | | | | | | 0.45 |

|

Present | 14 (58.3) | 4 (28.5) | 5 (71.5) | 0.08 | 7(50) | 7(50) | |

|

Absent | 10 (41.6) | 3(30) | 7(70) | | 7(70) | 3(30) | |

| Lymphovascular

invasion | | | | | | | 0.22 |

|

Present | 9 (37.5) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | 0.21 | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

|

Absent | 15 (62.5) | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Chemotherapy

response | | | | | | | 0.08 |

|

Present | 15 (62.5) | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | 0.07 | 9(60) | 6(40) | |

|

Absent | 9 (37.5) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | |

| Radiotherapy

response | | | | | | | 0.09 |

|

Present | 16 (66.6) | 4(25) | 12(75) | 0.99 | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.7) | |

|

Absent | 8 (33.4) | 4(50) | 4(50) | | 2(25) | 6(75) | |

| Progression | | | | | | | 0.14 |

|

Present | 7 (29.2) | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.7) | 0.16 | 7(100) | 0 (0) | |

|

Absent | 17 (70.8) | 6 (35.3) | 11 (64.7) | | 7 (41.2) | 10 (58.8) | |

Survivin levels

The serum survivin levels, measured using ELISA,

were significantly elevated in patients with OSCC [median (IQR),

196.19 (165.83-298.75) ng/ml; P=0.01) and FA [median (IQR), 216.38

(102.89-858.87); P=0.001] compared to the controls [median (IQR),

121.90 (103.85-182.03)]. The survivin levels were higher in

patients with FA than in patients with OSCC (P=0.028). These

results are presented in Fig. 2

and Table II.

In OSCC, the survivin levels did not exhibit a

significant association with clinical parameters, including tumor

stage, lymph node metastasis, or progression (P>0.05; Table III).

Correlation analysis

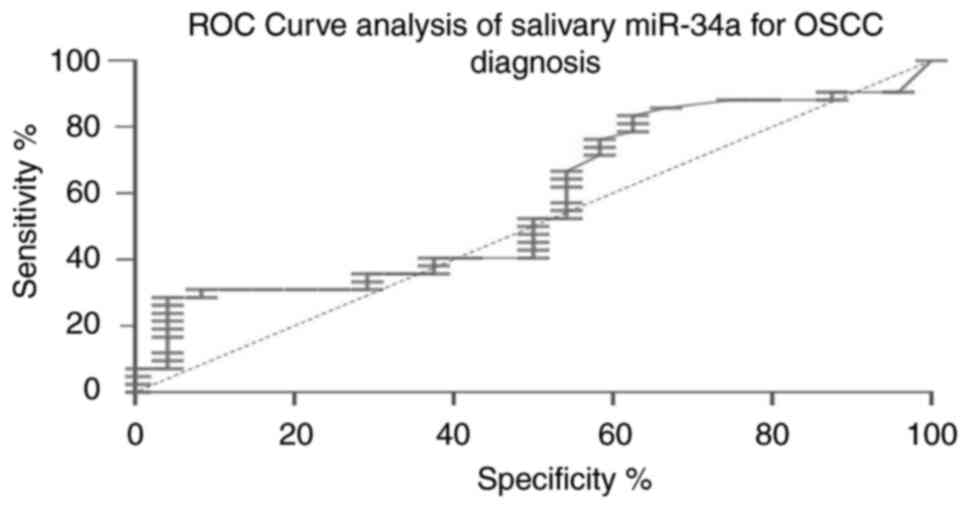

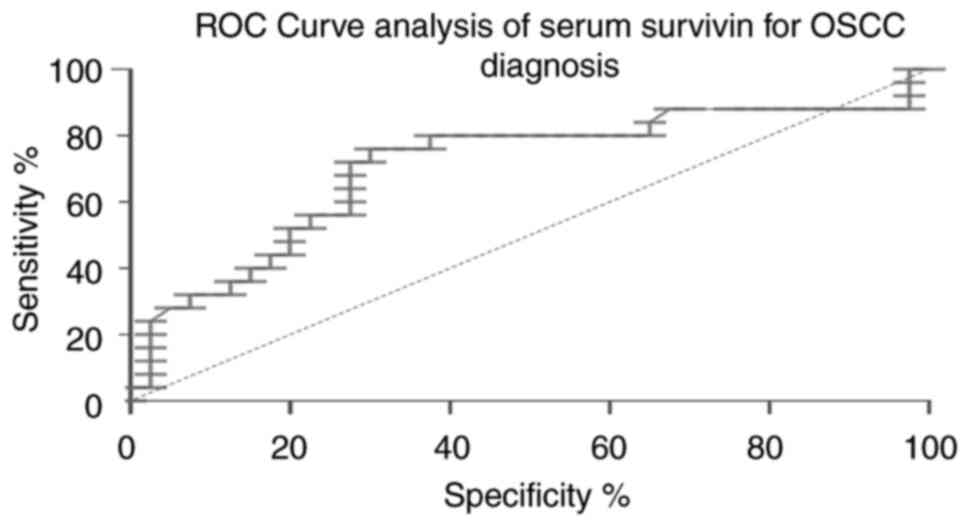

ROC analysis was used to evaluate the diagnostic

accuracy of miR-34a and survivin in OSCC. Salivary miR-34a

exhibited poor discriminatory power (AUC, 0.575; 95% CI,

0.439-0.719; cut-off value, >24.53; sensitivity, 24%;

specificity, 95%; Fig. 3), while

serum survivin exhibited a moderate discriminatory power (AUC,

0.710; 95% CI, 0.657-0.934; cut-off value, >191.1; sensitivity,

70%; specificity, 97%; Fig. 4). In

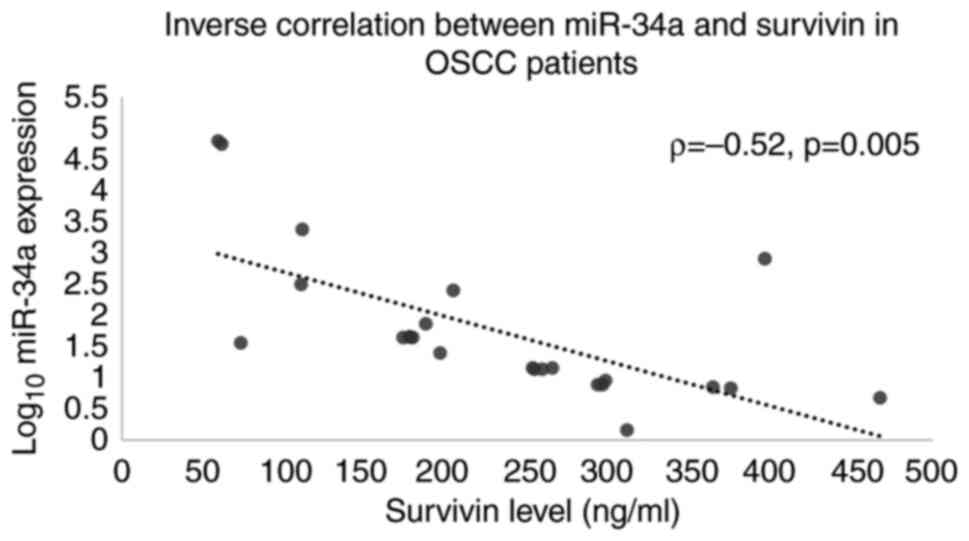

patients with OSCC, salivary miR-34a expression inversely

correlated with serum survivin levels (Spearman's Rho=-0.52;

P=0.005; Table IV and Fig. 5).

| Table IVInverse correlation between miR-34a

and survivin expression in OSCC patients. |

Table IV

Inverse correlation between miR-34a

and survivin expression in OSCC patients.

| Group | Correlation

coefficient (Rho) | P-value |

|---|

| OSCC (n=24) | -0.52 | 0.005 |

| FA (n=24) | - | >0.05 |

| Control (n=40) | - | >0.05 |

Discussion

The present pilot study was the first to evaluate

salivary miR-34a and serum survivin as non-invasive biomarkers for

OSCC surveillance in patients with FA and OSCC, with a focus on

their roles in cancer pathways. The findings revealed significant

alterations in miR-34a (P=0.012 in OSCC and P=0.014 in FA) and

survivin (P=0.04 in OSCC and P=0.01 in FA) compared to the

controls, providing molecular insight into the risk of developing

OSCC in patients with FA. Another key finding and limitation is the

marked age disparity between patients with FA and OSCC, which

reflects the biology of FA-related carcinogenesis, but introduces

potential age-related confounding factors.

The marked reduction of miR-34a levels in both OSCC

and FA aligns with its tumor-suppressive role, as it regulates the

Wnt and PI3K pathways by targeting genes, such as WNT1, PTEN and

BIRC5(11). However, miR-34a did

not exhibit a significant association with clinical parameters,

such as T stage or lymph node metastasis (P=0.34 and P=0.87,

respectively). It exhibited poor diagnostic performance (AUC,

0.575), indicating limitations as a standalone early predictive

marker for OSCC. Future studies are thus required to investigate

the use of combined biomarkers to improve the diagnostic accuracy.

In OSCC, a decreased miR-34a expression was associated with

enhanced tumor proliferation and metastasis, consistent with

studies reporting its downregulation in head and neck SCCs and an

association with advanced tumor stages (12). In the present study, the findings

of a reduced miR-34a level in OSCC and FA are consistent with those

of the study by Kalfert et al (8), who reported the downregulation of

miR-34a in head and neck cancers, emphasizing its potential as a

salivary biomarker for early detection.

In FA, the reduction of miR-34a expression, despite

elevated p53 activity, suggests alternative pathways that suppress

tumor-suppressive mechanisms, potentially indicating early

malignant transformation. This finding is in contrast to that of

reports of miR-34a upregulation in acute graft-vs.-host disease in

FA, highlighting the context-specific regulation of this miRNA

(13).

Elevated survivin levels in OSCC and FA underscore

its anti-apoptotic function via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway,

promoting tumor survival (9).

Overexpressed in SCCs (e.g., head and neck, lung) and detectable in

biofluids, survivin is associated with an aggressive tumor behavior

and a poor prognosis (9,14). In the present study, in patients

with FA, significantly higher survivin levels (P=0.001 vs. controls

and P=0.028 vs. OSCC) may reflect the evasion of apoptosis under

cellular stress. However, its lack of specificity limits its

utility as an OSCC-specific marker in FA. These findings align with

those in the study by Xie et al (15), who identified survivin as a

prognostic biomarker in oral cancers through a meta-analysis,

highlighting its role in tumor progression. The inverse correlation

observed between salivary miR-34a and serum survivin (Spearman's

Rho=-0.52, P=0.005) in patients with OSCC supports a potential

regulatory axis, which may be disrupted in FA. Although the present

study did not directly investigate mechanistic regulation, previous

studies suggest that miR-34a can downregulate survivin directly via

the PI3K/AKT pathway (16). This

possible regulatory axis warrants functional validation in future

in vitro and in vivo studies.

The consistency of miR-34a and survivin alterations

in saliva and serum supports non-invasive sampling, which is

particularly beneficial for patients with FA who are intolerant to

invasive procedures. Salivary biomarkers, such as miR-34a, could

enhance annual OSCC screening protocols for high-risk populations

such as patients with FA by enabling non-invasive monitoring during

routine dental check-ups. Although limited by sample size (FA,

n=24; OSCC, n=24; controls, n=40), which prevents the

identification of significant associations with clinical

parameters, the trends of lower miR-34a expression in advanced OSCC

stages align with previous research (8,12).

The ROC analysis for survivin (AUC, 0.710; sensitivity, 70%;

specificity, 97%) indicates moderate diagnostic potential, which is

lower than that reported in other cancer types (e.g., AUC, 0.729;

sensitivity, 57%; specificity, 82.6% in colon cancer) (17). By contrast, miR-34a exhibited poor

diagnostic performance (AUC, 0.575), further indicating that it

cannot be considered a reliable standalone marker and supporting

the need for multi-marker approaches.

The findings of the present study align with those

in the study by Chen et al (18), who linked miR-34a suppression to

cutaneous SCC progression, and studies identifying survivin as a

prognostic marker in head and neck cancers (9,14,15).

By demonstrating alterations in miR-34a and survivin in FA and

OSCC, the present study lays the groundwork for non-invasive

biomarker strategies to enhance early detection of OSCC in FA.

However, larger studies are warranted to validate their clinical

utility.

The present study has certain limitations which

should be mentioned. The key limitations of the present study

include the small sample size, the genotypic heterogeneity of FA

(e.g., FANCA mutations) and demographic variability between groups.

In particular, the significant age disparity between the patients

with FA (mean age, 20.03±5.87 years) and patients with OSCC (mean

age, 54.52±10.49 years) reflects the biology of FA-related

carcinogenesis, but also introduces potential age-related

confounding factors. The recruitment of age-matched patients with

FA and sporadic OSCC was not feasible in the current single-center

sample, and the limited cohort size precluded adequately powered

age-adjusted multivariable analyses. Additionally, the lack of

tumor stage stratification in OSCC further limits the

generalizability of the findings. Consequently, the biomarker

differences observed herein should be interpreted cautiously and

validated in larger, multicenter cohorts that are age-balanced or

stratified and prospectively followed for OSCC development and

treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

miR-34a and survivin are promising non-invasive biomarkers for the

surveillance of OSCC in patients with FA and OSCC. Their

integration into clinical screening protocols could enhance early

detection and improve survival outcomes in patients with FA and

OSCC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the organizing

committee of the European Hematology Oncology Congress (EHOC) 2021,

held as a hybrid event on November 10-13, 2021, at the Hilton

Istanbul Bomonti Hotel and Conference Center, for providing a

platform to present a preliminary version of this study (Abstract,

published with DOI: 10.1016/j.htct.2021.10.1085), which helped

refine the research through valuable feedback.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Scientific

Research Projects Coordination Unit of Istanbul University (Project

no. 34946) as part of a doctoral thesis project.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ZAK conceptualized and designed the study, performed

the experiments, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript and

supervised the project. NY contributed to the study design,

performed the clinical examinations of patients with Fanconi

anemia, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript and

evaluation of the results. TTC conducted the clinical examinations

of patients with Fanconi anemia and evaluated the study outcomes.

BB, HMY and OK performed clinical the examinations of patients with

oral squamous cell carcinoma and contributed to the evaluation of

the study outcomes. MGG conducted the statistical analyses and

contributed to data interpretation. ZAK and NY confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Istanbul

University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Approval no. 1307;

November 13, 2019) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants, with parental consent being obtained for those <18

years of age.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Rivera C and Venegas B: Histological and

molecular aspects of oral squamous cell carcinoma (Review). Oncol

Lett. 8:7–11. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Warnakulasuriya S: Global epidemiology of

oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 45:309–316.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mehrotra R and Yadav S: Oral squamous cell

carcinoma: Etiology, pathogenesis, and prognostic value of genomic

alterations. Indian J Cancer. 43:60–66. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kutler DI, Auerbach AD, Satagopan J,

Giampietro PF, Batish SD, Huvos AG, Goberdhan A, Shah JP and Singh

B: High incidence of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in

patients with Fanconi anemia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

129:106–112. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Singh T and Andi K: Fanconi anemia and

oral squamous cell carcinoma: Management considerations. N Z Med J.

130:92–95. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Smetsers SE, Velleuer E, Dietrich R, Wu T,

Brink A, Buijze M, Deeg DJ, Soulier J, Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ and

Brakenhoff RH: Noninvasive molecular screening for oral precancer

in Fanconi anemia patients. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 8:1102–1111.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mazumder S, Datta S, Ray JG, Chaudhuri K

and Chatterjee R: Liquid Biopsy: miRNA as a potential biomarker in

oral cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 58:137–145. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kalfert D, Ludvikova M, Pesta M, Ludvik J,

Dostalova L and Kholová I: Multifunctional Roles of miR-34a in

cancer: A review with the emphasis on head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma and thyroid cancer with clinical implications.

Diagnostics (Basel). 10(563)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Pickhard A, Gröber S, Haug AK, Piontek G,

Wirth M, Straßen U, Rudelius M and Reiter R: Survivin and pAkt as

potential prognostic markers in squamous cell carcinoma of the head

and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 117:733–742.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Fu J, Imani S, Wu MY and Wu RC:

MicroRNA-34 family in cancers: Role, mechanism, and therapeutic

potential. Cancers (Basel). 15(4723)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kumar B, Yadav A, Lang J, Teknos TN and

Kumar P: Dysregulation of microRNA-34a expression in head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma promotes tumor growth and tumor

angiogenesis. PLoS One. 7(e37601)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wang L, Romero M, Ratajczak P, Lebœuf C,

Belhadj S, Peffault de Latour R, Zhao WL, Socié G and Janin A:

Increased apoptosis is linked to severe acute GVHD in patients with

Fanconi anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48:849–853. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Khan Z, Khan AA, Yadav H, Prasad GBKS and

Bisen PS: Survivin, a molecular target for therapeutic

interventions in squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Mol Biol Lett.

22(8)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Xie S, Xu H, Shan X, Liu B, Wang K and Cai

Z: Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of survivin

expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: Evidence

from a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 10(e0116517)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Shen Z, Zhan G, Ye D, Ren Y, Cheng L, Wu Z

and Guo J: MicroRNA-34a affects the occurrence of laryngeal

squamous cell carcinoma by targeting the antiapoptotic gene

survivin. Med Oncol. 29:2473–2480. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jakubowska K, Pryczynicz A,

Dymicka-Piekarska V, Famulski W and Guzińska-Ustymowicz K:

Immunohistochemical expression and serum level of survivin protein

in colorectal cancer patients. Oncol Lett. 12:3591–3597.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Chen S, Yuan M, Chen H, Wu T, Wu T, Zhang

D, Miao X and Shi J: MiR-34a-5p suppresses cutaneous squamous cell

carcinoma progression by targeting SIRT6. Arch Dermatol Res.

316(299)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

![Salivary miR-34a expression levels in

the FA, OSCC and control groups. Bar graph illustrating the median

(IQR) miR-34a expression levels (quantified by RT-qPCR using the

2-ΔΔCq method with U6 normalization) across the groups

[OSCC, 1.33 (0.68-3.69); FA, 0.72 (0.05-3.19); and control, 3.63

(0.32-14.77)]. P-values indicate significant differences: P=0.012

for OSCC vs. control and P=0.014 for FA vs. control. Error bars

represent IQR. IQR, interquartile range; OSCC, oral squamous cell

carcinoma; FA, Fanconi anemia.](/article_images/wasj/8/1/wasj-08-01-00422-g00.jpg)

![Serum survivin levels in the FA, OSCC

and control groups. Bar graph illustrating the median (IQR) serum

survivin levels (measured using ELISA) in the different groups

[OSCC, 196.19 (165.83-298.75) ng/ml; FA, 216.38 (102.89-858.87)

ng/ml; and control, 121.90 (103.85-182.03) ng/ml]. P-values were as

follows: P=0.01 for OSCC vs. control, P=0.001 for FA vs. control,

and P=0.028 for FA vs. OSCC. Error bars represent IQR. IQR,

interquartile range; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; FA,

Fanconi anemia.](/article_images/wasj/8/1/wasj-08-01-00422-g01.jpg)