Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are among

the most common and economically significant musculoskeletal

injuries, particularly in athletes and physically active

individuals, with an estimated annual incidence of 1 in 3,500

individuals and ~400,000 ACL reconstruction (ACLR) procedures

performed annually in the USA (1).

These injuries frequently result in knee instability, reduced

functional capacity and long-term degenerative changes (2). ACLR is the standard surgical

intervention used to restore knee stability and enable a return to

pre-injury activity levels, with studies demonstrating that 80% of

individuals return to some form of sport and 55% return to

competitive levels following reconstruction (3). While ACLR is widely accepted as

effective, the optimal timing of the surgery remains a critical yet

unresolved clinical question. Early reconstruction is often

advocated to prevent secondary injuries, while delayed approaches

aim to reduce post-operative complications, such as arthrofibrosis

(2,4). This dichotomy underscores the need to

balance immediate surgical intervention with pre-operative

rehabilitation to optimize outcomes.

The debate surrounding early vs. delayed ACLR

centers on competing biomechanical, biological and clinical

considerations. Proponents of early surgery argue that prompt

stabilization reduces the risk of meniscal and chondral damage

caused by persistent knee instability (4,5).

Conversely, delayed reconstruction allows for the resolution of

acute inflammation and the restoration of pre-operative range of

motion, potentially minimizing post-operative stiffness (2,4).

Clinical guidelines lack consensus, with variations in recommended

waiting periods ranging from weeks to several months depending on

institutional protocols (2,6).

This variability reflects gaps in evidence regarding how surgical

timing interacts with patient-specific factors, such as age,

activity level and pre-operative rehabilitation compliance.

Muscle atrophy and neuromuscular dysfunction

represent significant consequences of ACL injury that influence

both surgical timing and rehabilitation outcomes. Quadriceus

weakness of up to 30% compared to the contralateral limb is nearly

ubiquitous following ACL injury, resulting from a combination of

disuse atrophy and central activation failure. Research indicates

that the optimal window for ACLR regarding muscle preservation may

lie between 21-100 days post-injury, as longer delays increase the

risk of progressive quadriceps atrophy and impaired early

rehabilitation (7).

The existing literature on the timing of ACLR has

been limited by heterogeneous study designs, inconsistent

definitions of ‘early’ vs. ‘delayed’ surgery, and short follow-up

durations (2,5). While recent investigations have

explored objective outcomes, such as muscle strength recovery and

return-to-sport rates, only a limited number of studies have

comprehensively evaluated patient-reported outcomes across diverse

demographic groups (6).

Furthermore, previous research often focuses on isolated ACL

injuries, neglecting the impact of concomitant meniscal repairs or

degenerative changes that frequently accompany delayed

presentations (4,5). These limitations hinder the

development of standardized, evidence-based protocols tailored to

individual patient needs and activity demands.

The present retrospective study aimed to address

these gaps in available evidence by analyzing the association

between the timing of ACLR and multidimensional patient outcomes in

a large, heterogeneous cohort. Despite numerous investigations, the

lack of an available consensus on optimal surgical timing persists,

particularly regarding its interaction with patient age,

preoperative activity level and concomitant knee pathology

(3,4,6). By

evaluating functional recovery, complication rates, and

patient-reported outcomes across different surgical intervals, the

present study aimed to provide clinicians with data-driven insights

to guide shared decision-making. The primary objective of the

present study was to determine whether early ACLR demonstrates

superior outcomes compared to delayed reconstruction when

controlling for demographic variables and injury characteristics,

thereby informing personalized treatment strategies for

ACL-deficient patients.

Patients and methods

Study design and setting

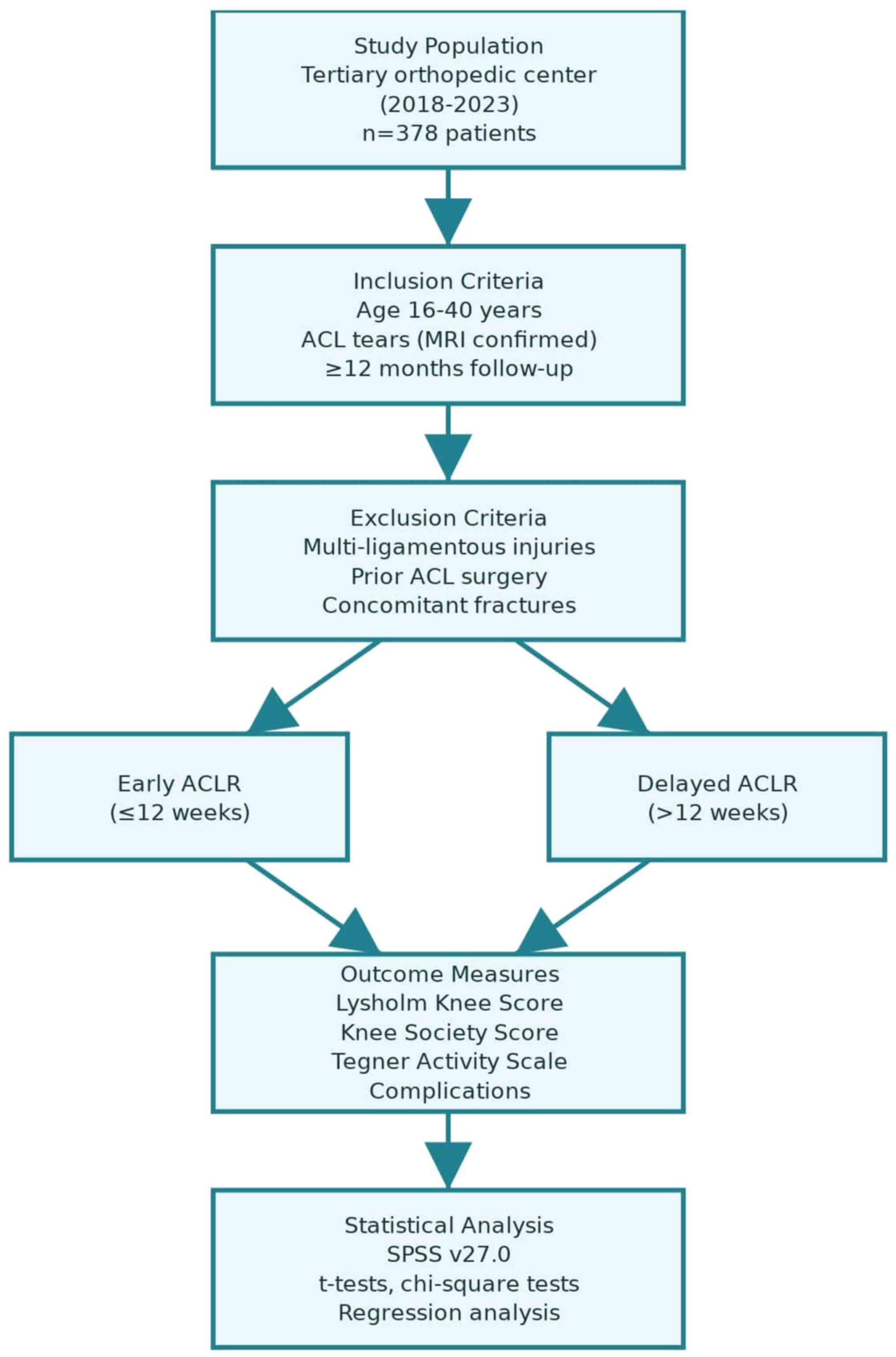

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at a

tertiary orthopedic center to evaluate the effects of early vs.

delayed ACLR on patient outcomes. The study protocol received

ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Raparin

University (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq; Reference no. 2866/28-5-2023). The

dataset comprised electronic medical records covering the period

between January, 2018 to December 20, 2024. The authors retrieved

these records and conducted follow-up assessments using structured

questionnaires between December 20, 2024 and April 10, 2025,

through in-person visits and telephone interviews. This combined

approach, retrospective clinical data supplemented with

contemporaneous patient-reported outcomes, is consistent with

current methodological standards aimed at enhancing data

completeness and validity. A detailed overview of participant

inclusion and analysis is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Participants and sampling

A non-probability purposive sampling strategy was

employed to select participants aged 16-40 years diagnosed with

partial or complete ACL tears via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

and a clinical examination. The sample size was calculated using

G*Power software (version 3.1), based on an effect size of 0.35

derived from a comparable study, with α=0.05 and 80% power,

yielding a minimum required sample of 68 participants. To account

for potential attrition, the target sample was increased, resulting

in 378 patients. The inclusion criteria required documented ACL

injury management at the study site and the completion of

post-operative follow-up for a period ≥12 months. The exclusion

criteria excluded individuals with multi-ligamentous injuries,

prior ipsilateral ACL reconstruction, cognitive impairments

affecting self-reporting, or concomitant fractures/dislocations

that could confound the recovery outcomes.

The present study reviewed the outcomes of ACL

injury regarding surgical timing, comparing early (within 12 weeks

post-injury) and delayed (>12 weeks post-injury) interventions

in a heterogeneous patient population. The objective was to

identify differences in the outcome measures related to surgical

timing, thereby providing insight applicable to a broad spectrum of

patients.

Data collection instruments and

variables

The data were extracted from electronic medical

records and structured questionnaires adapted from validated tools,

including the Lysholm Knee Score (LKS) (8), Knee Society Score (KSS) (9) and Tegner Activity Scale (TAS)

(8). The retrieval of medical

record data and the administration of questionnaires were carried

out by the authors between December 20, 2024 and April 10, 2025,

after obtaining ethical approval. The questionnaire was comprised

of three domains: i) Socio-demographics: Age, sex, occupation,

education level, residence and pre-injury activity level. ii)

Clinical and surgical details: Injury mechanism, surgical timing

stratified as early (≤12 weeks) or delayed (>12 weeks). iii)

Rehabilitation: The duration of pre-operative and post-operative

rehabilitation and participation.

The outcome measures were the following: Functional

recovery (LKS and KSS), activity level (measured using the TAS),

complications (infection, re-tear, stiffness, pain, instability,

nerve injury) and patient satisfaction. To ensure reliability, the

questionnaire underwent pilot testing with 5 patients, which was

conducted by the authors between December 1, 2024, and December 15,

2024, demonstrating excellent internal consistency (Cronbach s

α=0.89) and content validity, as assessed by three orthopedic

surgeons independently. Final data collection was subsequently

carried out by the authors via telephone or electronic

communication to maximize follow-up completeness.

Ethical considerations

All data were anonymized and stored on secure,

password-protected servers. Ethical approval for the full study,

including pilot testing and patient follow-up, was obtained prior

to data collection. The study adhered to STROBE guidelines for

observational research to ensure methodological rigor and

transparency.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

Statistics (v27.0). Descriptive statistics summarized the baseline

characteristics. Continuous variables were compared between early

and delayed groups using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U

tests, depending on normality (assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests).

The categorical variables (e.g., complication rates) were analyzed

using Chi-squared or Fisher s exact tests. Multivariable

linear and logistic regression models adjusted for confounders,

including age, body mass index, pre-operative activity level and

meniscal/chondral injuries.

Results

The study included a total of 378 patients, with 108

(28.6%) patients in the early ACL group and 270 (71.4%) patients in

the delayed ACLR group. Among these, 95 (88.0%) patients in the

early ACLR group were male compared to 264 (97.8%) in the delayed

ACLR group, and the difference between the groups was statistically

significant (P<0.001). The median age of all the patients was 29

years [quartile range (QR), 24-35], with the early ACLR group

having a younger median age of 27 years (QR, 22.5-33), compared to

30 years (QR, 25-37) in the delayed ACLR group (P=0.003). As

regards occupation, heavy manual labor was the most common type of

work, reported by 37 (34.3%) patients in the early group and 90

(33.3%) patients in the delayed ACLR group (P=0.096). The majority

of the patients had attained a higher education, with 46 (42.6%)

patients in the early ACLR group and 143 (53.0%) patients in the

delayed ACLR group (P=0.138). Urban residency was reported by 58

(53.7%) of the patients in the early ACLR group and 128 (47.4%) of

the patients in the delayed ACLR group (P=0.425). Sports-related

injury was the leading cause of ACL rupture, accounting for 73

(67.6%) of early cases and 210 (77.8%) of delayed cases (P=0.217)

(Table I).

| Table IComparison of demographic,

socioeconomic and clinical characteristics between the early and

delayed ACLR groups. |

Table I

Comparison of demographic,

socioeconomic and clinical characteristics between the early and

delayed ACLR groups.

| Variables | Total (n=378) | Early ACLR

(n=108) | Delayed ACLR

(n=270) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, n (%) | | | | <0.001 |

|

Male | 359 | 95 (88.0) | 264 (97.8) | |

|

Female | 19 | 13 (12.0) | 6 (2.2) | |

| Age, median (QR) | 29 (24-35) | 27 (22.5-33) | 30 (25-37) | 0.003 |

| BMI, median (QR) | 26.2 (23.8-28.7) | 25.9 (23.1-27.9) | 26.2 (24.2-29.1) | 0.547 |

| Occupation, n

(%) | | | | 0.096 |

|

Heavy manual

labor | 127 | 37 (34.3) | 90 (33.3) | |

|

Light manual

labor | 21 | 5 (4.6) | 16 (5.9) | |

|

Nonmanual

(walking/standing) | 71 | 14 (13.0) | 57 (21.1) | |

|

Non-manual

(non-office) | 59 | 24 (22.2) | 35 (13.0) | |

|

Office | 92 | 24 (22.2) | 68 (25.2) | |

|

Domestic | 8 | 4 (3.7) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Educational level, n

(%) | | | | 0.138 |

|

Illiterate | 12 | 4 (3.7) | 8 (3.0) | |

|

Primary | 43 | 10 (9.3) | 33 (12.2) | |

|

Secondary | 65 | 26 (24.1) | 39 (14.4) | |

|

High

school | 69 | 22 (20.4) | 47 (17.4) | |

|

Higher

education | 189 | 46 (42.6) | 143 (53.0) | |

| Time from injury to

surgery, weeks, median (QR) | 48.0

(12.0-144.0) | 4.0 (2.0-8.0) | 80.0

(36.0-208.0) | <0.001 |

| Residence, n (%) | | | | 0.425 |

|

Urban | 186 | 58 (53.7) | 128 (47.4) | |

|

Sub-urban | 180 | 46 (42.6) | 134 (49.6) | |

|

Rural | 12 | 4 (3.7) | 8 (3.0) | |

| History of other knee

injury, n (%) | | | | 0.315 |

|

Yes | 72 | 24 (22.2) | 48 (17.8) | |

|

No | 306 | 84 (77.8) | 222 (82.2) | |

| Monthly income, n

(%) | | | | 0.366 |

|

Sufficient | 114 | 33 (30.6) | 81 (30.0) | |

|

Barely

sufficient | 243 | 72 (66.7) | 171 (63.3) | |

|

Insufficient | 21 | 3 (2.8) | 18 (6.7) | |

| Causes of ACL

injury, n (%) | | | | 0.217 |

|

Sport | 283 | 73 (67.6) | 210 (77.8) | |

|

Road traffic

accident | 15 | 7 (6.5) | 8 (3.0) | |

|

Bullet | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | |

|

Fall from

height | 39 | 15 (13.9) | 24 (8.9) | |

|

Disease | 3 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.7) | |

|

Others | 36 | 12 (11.1) | 24 (8.9) | |

| Return to daily

activity, weeks, median (QR) | 6 (4-9) | 7 (2-9) | 6 (2-9) | 0.987 |

Among the 378 patients included in the present

study, 114 (30.2%) patients underwent rehabilitation prior to

surgery, with a significantly higher proportion in the delayed ACLR

group (n=90, 33.3%) compared to the early ACLR group (n=24, 22.2%)

(P=0.035). The median duration of pre-operative rehabilitation was

4.0 weeks (QR, 2.5-8.5), with patients in the delayed ACLR group

receiving longer periods of rehabilitation (median, 5.0 weeks; QR,

4.0-10.0) than those in the early ACLR group (median, 3.0 weeks;

QR, 2.0-4.0) (P=0.011). Post-operative rehabilitation was almost

universal, with 366 (96.8%) patients participating and no

significant difference observed between the early (n=106, 98.1%)

and delayed ACLR groups (n=260, 96.3%) (P=0.285). The median

duration of post-operative rehabilitation was 9.0 weeks (QR,

5.0-17.0), with comparable durations between the groups (P=0.734).

A history of knee popping sounds was reported in 230 (60.8%)

patients, with similar rates between the early (n=63, 58.3%) and

delayed (n=167, 61.9%) ACLR groups (P=0.275). The median frequency

of knee popping was 30 episodes per month (QR, 15.0-75.0),

consistent across both groups (P=0.606) (Table II).

| Table IIPre-operative and post-operative

rehabilitation profiles and symptomatology in early vs. delayed

ACLR. |

Table II

Pre-operative and post-operative

rehabilitation profiles and symptomatology in early vs. delayed

ACLR.

| Variables | Total (n=378) | Early ACLR

(n=108) | Delayed ACLR

(n=270) | P-value |

|---|

| Rehabilitation

prior to surgery, n (%) | | | | 0.035 |

|

Yes | 114 | 24 (22.2) | 90 (33.3) | |

|

No | 264 | 84 (77.8) | 180 (66.7) | |

| Pre-operative

rehabilitation duration, weeks, median (QR) | 4.0 (2.5-8.5) | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) | 5.0 (4.0-10.0) | 0.011 |

| Post-operative

rehabilitation, n (%) | | | | 0.285 |

|

Yes | 366 | 106 (98.1) | 260 (96.3) | |

|

No | 12 | 2 (1.9) | 10 (3.7) | |

| Post-operative

rehabilitation, weeks, median (QR) | 9.0 (5.0-17.0) | 8.0 (4.0-16.0) | 9.0 (5.0-20.0) | 0.734 |

| History of knee

popping sound, n (%) | | | | 0.275 |

|

Yes | 230 | 63 (58.3) | 167 (61.9) | |

|

No | 148 | 45 (41.6) | 103 (38.1) | |

| Knee popping

sound/month, median (QR) | 30.0

(15.0-75.0) | 30.0

(15.0-50.0) | 30.0

(15.0-75.0) | 0.606 |

| History of knee

locking, n (%) | | | | 0.415 |

|

Yes | 85 | 21 (19.4) | 64 (23.7) | |

|

No | 293 | 87 (80.6) | 206 (76.3) | |

The functional outcomes assessed using the LKS

demonstrated that 200 (52.9%) patients achieved an excellent

outcome, with a significantly higher proportion in the early ACL

group (n=88, 81.5%) compared to the delayed ACLR group (n=112,

41.5%) (P<0.001). Good, fair and poor outcomes were reported in

26.5, 15.3 and 5.3% of the total cohort, respectively. The KSS for

range of motion indicated that the majority of the patients

attained excellent (n=286, 75.7%) or good (n=79, 20.9%) results,

with no significant difference between the early and delayed ACLR

groups (P=0.126). Similarly, the TAS revealed that 292 (77.2%)

patients achieved excellent activity levels, with a higher

percentage observed in the early ACLR group (n=93, 86.1%) compared

to the delayed ACLR group (n=199, 73.7%), reaching borderline

statistical significance (P=0.05) (Table III).

| Table IIIComparison of functional outcomes,

range of motion, and activity levels in early vs. delayed ACLR

using LKS, KSS and TAS. |

Table III

Comparison of functional outcomes,

range of motion, and activity levels in early vs. delayed ACLR

using LKS, KSS and TAS.

| Variables | Total (n=378) | Early ACLR

(n=108) | Delayed ACLR

(n=270) | P-value |

|---|

| LKS for functional

outcome, n (%) | | | | <0.001 |

|

Excellent | 200 (52.9) | 88 (81.5) | 112 (41.5) | |

|

Good | 100 (26.5) | 8 (7.4) | 92 (34.1) | |

|

Fair | 58 (15.3) | 9 (8.3) | 49 (18.1) | |

|

Poor | 20 (5.3) | 3 (2.8) | 17 (6.3) | |

| KSS for range of

motion, n (%) | | | | 0.126 |

|

Excellent | 286 (75.7) | 89 (82.4) | 197 (73.0) | |

|

Good | 79 (20.9) | 15 (13.9) | 64 (23.7) | |

|

Fair | 11 (2.9) | 4 (3.7) | 7 (2.6) | |

|

Poor | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | |

| TAS for activity

level, n (%) | | | | 0.05 |

|

Excellent | 292 (77.2) | 93 (86.1) | 199 (73.7) | |

|

Good | 73 (19.3) | 13 (12.0) | 60 (22.2) | |

|

Fair | 9 (2.4) | 2 (1.9) | 7 (2.6) | |

|

Poor | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.5) | |

Complications occurred in varying frequencies among

the patients. Infection was reported in 67 (17.7%) cases, with no

significant difference between the early (n=21, 19.4%) and delayed

ACLR groups (n=46, 17.0%) (P=0.655). Re-tear rates were low,

observed in 11 (2.9%) patients overall, and tended to be higher in

the delayed ACLR group (n=10, 3.7%) compared to the early ACLR

group (n=1, 0.9%), although this difference was not statistically

significant (P=0.190). Knee stiffness was significantly more

frequent in the delayed ACLR group 23, 8.5%) than in the early ACLR

group (n=2, 1.9%) (P=0.020). Nerve damage was rare, occurring in

only 1 (0.3%) patient in the delayed ACLR group, with no cases

reported in the early ACLR group. Persistent pain affected 55

(14.6%) patients, and was significantly more common in the delayed

ACLR group (n=49, 18.1%) than the early ACLR group (n=6, 5.6%)

(P=0.001). Similarly, knee instability was significantly higher in

the delayed ACLR group 22(8.1%) compared to the early ACLR group

(n=2, 1.9%) (P=0.020) (Table

IV).

| Table IVComparison of postoperative

complications in early vs. delayed ACLR. |

Table IV

Comparison of postoperative

complications in early vs. delayed ACLR.

| Complications | Total (n=378) | Early ACLR

(n=108) | Delayed ACLR

(n=270) | P-value |

|---|

| Infection, n

(%) | 67 (17.7) | 21 (19.4) | 46 (17.0) | 0.655 |

|

Yes | 311 (82.3) | 87 (80.6) | 224 (83.0) | |

|

No | | | | |

| Re-tear, n (%) | | | | 0.190 |

|

Yes | 11 (2.9) | 1 (0.9) | 10 (3.7) | |

|

No | 367 (97.1) | 107 (99.1) | 260 (96.3) | |

| Knee-stiffness, n

(%) | | | | 0.020 |

|

Yes | 25 (6.6) | 2 (1.9) | 23 (8.5) | |

|

No | 353 (93.4) | 106 (98.1) | 247 (91.5) | |

| Nerve damage, n

(%) | | | | NS |

|

Yes | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | |

|

No | 377 (99.7) | 108 (100.0) | 269 (99.6) | |

| Persistent pain, n

(%) | | | | 0.001 |

|

Yes | 55 (14.6) | 6 (5.6) | 49 (18.1) | |

|

No | 323 (85.4) | 102 (94.4) | 221 (81.9) | |

| Knee instability, n

(%) | | | | 0.020 |

|

Yes | 24 (6.3) | 2 (1.9) | 22 (8.1) | |

|

No | 354 (93.7) | 106 (98.1) | 248 (91.9) | |

Discussion

The optimal timing for ACL reconstruction remains a

topic of ongoing debate, with recent high-quality systematic

reviews and meta-analyses yielding conflicting results regarding

the impact of early vs. delayed intervention on comprehensive

patient outcomes. In the present study, a cohort of 378 patients

was analyzed, with 108 undergoing early ACLR and 270 receiving

delayed surgery. Notably, the delayed group demonstrated a

significantly higher proportion of male patients and an older

median age, which may reflect the demographic profile commonly

observed in large cohorts of ACL-deficient patients seeking care at

tertiary centers (2,10). Heavy manual labor was the most

common occupation in both groups, and the majority of patients had

attained higher education, suggesting that socioeconomic factors

did not significantly influence the timing of surgery in this

population. Urban vs. rural residency also did not differ between

groups, indicating that access to care may not have been a major

determinant of surgical timing (11).

Herein, sports-related injury mechanisms accounted

for the majority of ACL ruptures in both groups, consistent with

epidemiological data identifying sports participation as the

leading cause of ACL injury in young, active populations.

Specifically, non-contact mechanisms account for ~70% of ACL

injuries, typically occurring during pivoting, cutting, or landing

maneuvers that generate combined rotational and translational

forces. This injury pattern was reflected in the cohort in the

present study and aligns with broader epidemiological trends

demonstrating ACL injury rates of 6.5 per 100,000 athlete exposures

in high school sports, with competition carrying a 7-fold higher

risk than practice (12,13).

A significantly higher proportion of patients in the

delayed ACLR group underwent pre-operative rehabilitation, and the

duration of this rehabilitation was longer compared to the early

ACLR group. This practice reflects current evidence-based

recommendations to optimize knee function, reduce effusion and

restore range of motion prior to surgery, although recent evidence

suggests that the benefits of pre-operative rehabilitation may be

limited in certain populations (2,14). A

recent systematic review demonstrated that structured

prehabilitation programs, incorporating quadriceps strengthening,

range of motion exercises and neuromuscular training, provide

measurable benefits in post-operative recovery (15). However, the optimal duration and

intensity of prehabilitation remain subjects of ongoing

investigation, with programs ranging from 4-6 weeks demonstrating

the most consistent benefits (15). In the present study, post-operative

rehabilitation was almost universal in both groups with no

significant difference in participation or duration, reflecting the

widespread adoption of accelerated rehabilitation protocols in

modern ACLR (16).

Functional outcomes, as assessed using the LKS,

revealed a marked advantage for the early ACLR group, with 81.5%

achieving excellent results compared to 41.5% in the delayed ACLR

group. This finding appears to be in contrast to the most recent

and comprehensive meta-analysis by Shen et al (2), which analyzed 11 randomized

controlled trials involving 972 participants and found no

significant differences in the majority of functional outcomes

between early and delayed ACLR. However, their analysis did

identify small, yet statistically significant advantages for early

reconstruction in IKDC scores (mean difference, 2.77 points) and

2-year Lysholm scores (mean difference, 2.61 points) (2). The magnitude of difference observed

in the present study exceeds these meta-analytic findings,

potentially reflecting the influence of confounding variables

inherent in retrospective cohort designs or differences in patient

populations and rehabilitation protocols. Other studies have

reported that early reconstruction may be associated with improved

knee function and movement ability at short-term follow-up,

particularly in highly active patients (14).

Contemporary evidence regarding functional outcomes

demonstrates considerable variability across studies, largely

attributable to heterogeneous definitions of ‘early’ and ‘delayed’

timing, ranging from 2 days to 7 months for early reconstruction

and 3 weeks to several years for delayed procedures. This

definitional inconsistency complicates direct comparisons between

studies and contributes to ongoing clinical uncertainty. Recent

investigations have attempted to establish more precise timing

thresholds, with some evidence suggesting that reconstruction

performed within 3-5 months of injury may optimize outcomes while

minimizing complications (17,18).

In the present study, the KSS for range of motion

indicated that most patients achieved excellent or good results,

with no significant difference between the groups. This is

consistent with the findings of recent systematic reviews, which

found no significant difference in the objective measures of knee

motion or stability between early and delayed reconstruction

(2,14). The TAS revealed that a higher

percentage of patients in the early ACLR group achieved excellent

activity levels with a borderline significant difference. This

suggests that early intervention may facilitate a more rapid return

to pre-injury activity, although the evidence from randomized

trials remains equivocal (2,14).

Return-to-sport outcomes are critical indicators of

the success of ACLR, particularly among athletic populations.

Successful return to sport is influenced, not only by biomechanical

recovery, but also by psychological readiness, self-efficacy and

knee-related quality of life. Previous studies have demonstrated

that patients who achieve a return to their pre-injury activity

levels report significantly higher satisfaction rates and improved

quality of life measures (19,20).

In the present study, the median duration for return to daily

activities was 5 weeks (QR, 4-9 weeks), with no significant

difference observed between the early and delayed reconstruction

groups (7.0, 2.0-9.0 weeks for the early group vs. 6.0, 2.0-9.0

weeks for the delayed group).

Complication rates were generally low in both

groups, with no significant difference in infection or re-tear

rates. This finding is supported by recent meta-analyses, which

found no significant difference in the rates of these complications

between early and delayed ACL reconstruction (2,21).

However, knee stiffness and persistent pain were significantly more

common in the delayed ACLR group, echoing findings from

observational studies that have reported higher rates of

arthrofibrosis and persistent symptoms in patients with prolonged

preoperative intervals (11). In

the present study, there was no significant difference in infection

rates between the early and delayed ACL reconstruction groups. The

initially reported infection rate of 67 out of 378 cases included

all postoperative inflammatory events, such as superficial wound

erythema and minor serous discharge, which were conservatively

managed with oral antibiotics, rather than only confirmed deep

joint infections. Upon reclassification, only 3 cases (0.8%) met

the criteria for deep surgical-site infection, which is consistent

with the globally reported incidence range of 0.4-1.4%, as

documented in recent meta-analyses (22).

Recent studies have also highlighted the risk of

secondary intra-articular pathology with delayed ACLR. For example,

a previous prospective observational study found that the odds of

chondral injury increased significantly with a longer time since

the original injury, while meniscal injuries were less predictable

but still tended to increase over time (11). Another study reported that the risk

of concomitant intra-articular pathology, particularly chondral

injuries, increased linearly with a longer time to surgery

(23). This suggests that while

early reconstruction may not always result in improved functional

outcomes, it may help to reduce the risk of additional joint

damage.

The optimal window for ACLR with respect to muscle

atrophy has been suggested to lie between 21 and 100 days following

injury, as delaying surgery beyond this period may increase the

risk of quadriceps atrophy and impair early rehabilitation

(14). This is consistent with the

findings of the present study, where increased stiffness and

persistent pain was found in the delayed group, which may be

related to prolonged immobilization or reduced muscle strength.

Several limitations should be considered in the

interpretation of the present study. First, its retrospective and

non-randomized nature introduces the potential for confounding

variables, such as differences in surgical technique, graft

selection, or associated injuries, which could influence outcomes

and make it difficult to establish causality between the timing of

ACLR and the clinical results. Second, all ACLRs were performed by

a single surgeon, which, while ensuring procedural consistency, may

limit the generalizability of the findings. The influence of the

experience of the surgeon on outcomes is acknowledged as a

potential source of bias and further studies are required to

consider including multiple surgeons to better account for this

variable. Finally, the lack of long-term follow-ups and the

comprehensive assessment of secondary intra-articular pathology,

such as meniscal or chondral injuries, may have resulted in an

incomplete understanding of the true impact of surgical timing on

knee health and function.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

early ACLR (performed within 12 weeks post-injury) is associated

with superior functional outcomes, higher activity levels and

reduced rates of knee stiffness, persistent pain, and instability

compared to delayed surgery. Although delayed reconstruction allows

for longer pre-operative rehabilitation, it may increase the risk

of developing post-operative complications that adversely affect

recovery. These findings support early surgical intervention as a

strategy to optimize patient outcomes, particularly in younger,

active individuals. Individualized treatment decisions should

consider patient-specific factors such as age, activity demands,

and concomitant knee pathology to tailor the timing of ACLR for

optimal recovery.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

Both authors (BMR and YKB) contributed equally to

the conception and design of the study, as well as in data

collection and analysis, and in the writing of the manuscript. BMR

and YKB confirm the authenticity of the raw data. Both authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Scientific

Committee of University of Raparin (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq; Reference

no. 2866/28-5-2023). Written informed consent was obtained from the

patients or the patients parents (in the case of patients who

were underage) for participation in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kaeding CC, Léger-St-Jean B and Magnussen

RA: Epidemiology and diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament

injuries. Clin Sports Med. 36:1–8. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Shen X, Liu T, Xu S, Chen B, Tang X, Xiao

J and Qin Y: Optimal timing of anterior cruciate ligament

reconstruction in patients with anterior cruciate ligament tear: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open.

5(e2242742)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Waldron K, Brown M, Calderon A and Feldman

M: Anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation and return to sport:

How fast is too fast? Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 4:e175–e179.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Herbst E, Hoser C, Gföller P, Hepperger C,

Abermann E, Neumayer K, Musahl V and Fink C: Impact of surgical

timing on the outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 25:569–577. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Anstey DE, Heyworth BE, Price MD and Gill

TJ: Effect of timing of ACL reconstruction in surgery and

development of meniscal and chondral lesions. Phys Sportsmed.

40:36–40. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Högberg J, Fridh E, Piussi R, Senorski RH,

Cristiani R, Samuelsson K, Thomeé R and Senorski EH: Delayed

anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is associated with lower

odds of returning to preinjury physical activity level at 12 months

Follow-Up. Arthroscopy. 41:3401–3412.e4. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Thomas AC, Wojtys EM, Brandon C and

Palmieri-Smith RM: Muscle atrophy contributes to quadriceps

weakness after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Sci Med

Sport. 19:7–11. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Briggs KK, Kocher MS, Rodkey WG and

Steadman JR: Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the

Lysholm knee score and Tegner activity scale for patients with

meniscal injury of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 88:698–705.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Scuderi GR, Bourne RB, Noble PC, Benjamin

JB, Lonner JH and Scott W: The new knee society knee scoring

system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 470:3–19. 2011.

|

|

10

|

Migliorini F, Lucenti L, Mok YR, Bardazzi

T, D Ambrosi R, De Carli A, Paolicelli D and Maffulli N:

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using lateral

Extra-articular procedures: A systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas).

61(294)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Patra SK, Unnava N, Patro BP and Mohanty

S: Timing of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and its

effect on associated chondral damage and meniscal injury: A

prospective observational study. Int J Res Orthop. 9:770–775.

2023.

|

|

12

|

Joseph AM, Collins CL, Henke NM, Yard EE,

Fields SK and Comstock RD: A multisport epidemiologic comparison of

anterior cruciate ligament injuries in high school athletics. J

Athl Train. 48:810–817. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Montalvo AM, Schneider DK, Webster KE, Yut

L, Galloway MT, Heidt RS Jr, Kaeding CC, Kremcheck TE, Magnussen

RA, Parikh SN and Stanfield DT: Anterior cruciate ligament injury

risk in sport: A systematic review and meta-analysis of injury

incidence by sex and sport classification. J Athl Train.

54:472–482. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Widhalm HK, Draschl A, Horns J, Rilk S,

Leitgeb J, Hajdu S and Sadoghi P: The optimal window for

reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) with respect

to quadriceps atrophies lies within 21 to 100 days. PLoS One.

19(e0296943)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zakharia A, Zhang K, Al-Katanani F, Rathod

P, Uddandam A, Kay J, Murphy B, Ogborn D and de SAD:

Prehabilitation prior to anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

is a safe and effective intervention for short-to long-term

benefits: A systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.

33:4148–4166. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ricupito R, Grassi A, Mourad F, Di Filippo

L, Gobbo M and Maselli F: Anterior Cruciate Ligament Return to

Play:‘A Framework for Decision Making’. J Clin Med.

14(2146)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liu AF, Guo TC, Feng HC, Yu WJ, Chen JX

and Zhai JB: Efficacy and safety of early versus delayed

reconstruction for anterior cruciate ligament injuries: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee. 44:43–58.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zsidai B, Kaarre J, Narup E and Samuelsson

K: Timing of anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Clin Sports Med.

43:331–341. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Battaglia M, Arner JW, Midtgaard KS, Haber

DB, Peebles LA, Peebles AM, Ganokroj P, Whalen RJ, Provencher MT,

Torre G and Ciatti R: Early versus standard return to play

following ACL reconstruction: Impact on volume of play and career

longevity in 180 professional European soccer players: A

retrospective cohort study. J Orthop Traumatol.

26(29)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Piussi R, Simonson R, Zsidai B, Grassi A,

Karlsson J, Della Villa F, Samuelsson K and Senorski EH: Better

safe than sorry? A systematic review with meta-analysis on time to

return to sport after ACL reconstruction as a risk factor for

second ACL injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 54:161–175.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lee YS, Lee OS, Lee SH and Hui TS: Effect

of the timing of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on

clinical and stability outcomes: A systematic review and

Meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 34:592–602. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Cassano GD, Moretti L, Vicenti G, Buono C,

Albano F, Ladogana T, Rausa I, Notarnicola A and Solarino G:

Infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A

narrative review of the literature. Healthcare (Basel).

12(894)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Phillips T, Ronna B, Terner Z, Cushing T,

Goldenberg N and Shybut T: After 40 days intra-articular injury,

risk profile increases linearly with time to surgery in adolescent

patients undergoing primary anterior cruciate ligament

reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 33:1192–1201.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|