Introduction

Desmoid-type fibromatosis (DTF) is a benign, locally

infiltrating mesenchymal tumor that causes fibroblast and

myofibroblast proliferation, and increased collagen production in

deep musculoaponeurotic structures. It has intermediate biological

characteristics between benign fibrous lesions and fibrosarcoma

(1). The disease is extremely

rare, accounting for only 0.03% of all neoplasms (2). Additionally, a notable predilection

towards females has been observed (3). The etiology of DTF is multifaceted,

possibly influenced by a combination of genetic predisposition,

traumatic events and hormonal factors (4). DTF is classified into three subtypes

based on their anatomical location: Abdominal wall,

intra-abdominal, and extra-abdominal. Extra-abdominal desmoid

tumors account for approximately one-third of all desmoid cases and

most commonly arise in the shoulder, pelvic girdle and limbs.

However, only 10-25% of cases occur in the head and neck region

(5). Unlike other benign neoplasms

in this area, desmoid tumors exhibit infiltrative growth and a

marked propensity for local recurrence following surgery,

underscoring the need for accurate diagnosis and appropriate

management. Although complete resection with negative microscopic

margins is considered the standard of care for DTF which is

unresponsive to other treatments, achieving such margins in the

head and neck is challenging due to the density of vital

structures. This difficulty is even more pronounced in pediatric

patients, where surgeons may hesitate to perform wide resections

owing to the substantial risk of post-operative functional

morbidity (3,4).

The present study describes the case of a male

pediatric patient diagnosed with DTF involving the level II. The

present case report was written in accordance with the CaReL

guidelines, with filtering references to prevent citing contents in

blacklisted journals (6,7).

Case report

Patient information

On December 20, 2023, a 2-year-old male patient was

brought to Smart Health Tower, Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, presenting with

a gradually progressing swelling in the left submandibular region

that had developed insidiously over the previous 3 months.

Clinical findings

The neck mass was large, firm and non-tender, below

the angle of the mandible on the left side of the neck.

Diagnostic assessment

The hematological test results of the patient were

normal. A neck ultrasound revealed a well-defined, lobulated,

predominantly solid hypoechoic left subcutaneous mass, measuring

38x31x27 mm, with mild vascularity, mild surrounding inhomogeneity

and features suggestive of a suppurative or necrotic lymph node.

There was bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, with nodes of

variable size, well-defined, with a cortical thickness <2 mm,

and a preserved shape and hilar echotexture; the largest node

measured 15x6 mm in the left level II. The thyroid, submandibular

and parotid glands were normal, with no focal lesions (data not

shown). A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the

chest and abdomen yielded normal findings (data not shown).

Therapeutic intervention

A surgical cervical exploration with lymph node

biopsy was performed under general anesthesia with the patient

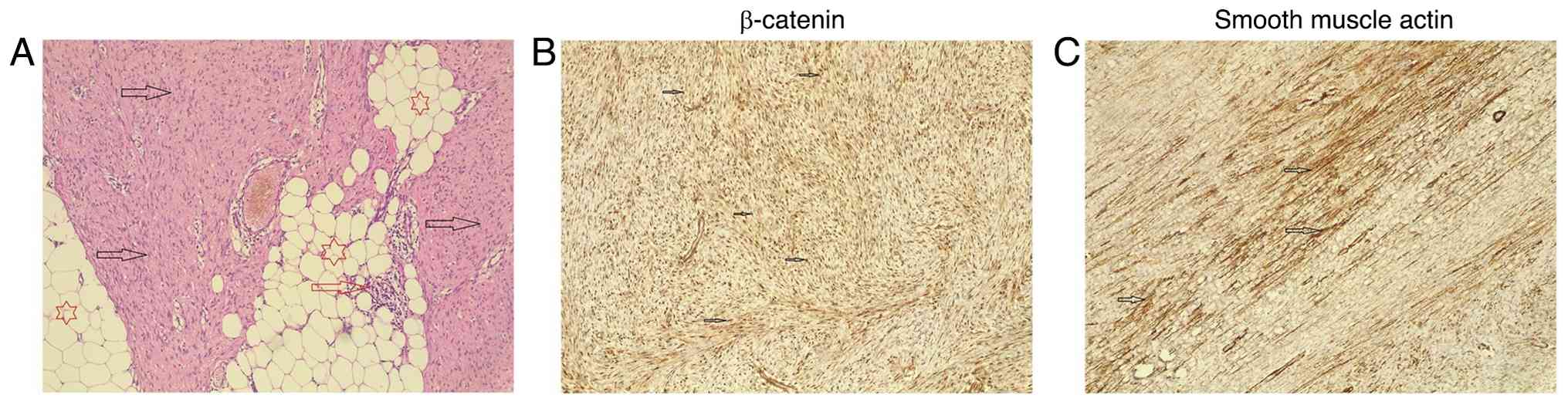

placed in the supine position. A post-operative histopathological

examination (HPE) was performed. The biopsy specimen was placed

into tissue cassettes and processed using the DiaPath Donatello

automated processor with a standard 11-h protocol involving graded

alcohols, xylene and paraffin. Following paraffin embedding and

trimming, blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 4-6 µm onto

standard glass slides, incubated in an oven at 60˚C overnight, and

stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) on the DiaPath Giotto

automated stainer using Gill II hematoxylin (1% for 10 min). The

slides were then dried, coverslipped, and examined under a light

microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). For immunohistochemistry,

paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 4-6 µm and mounted onto

charged glass slides, followed by overnight incubation at 60˚C.

Antigen retrieval was performed using the Dako PT Link system

(Agilent Technologies, Inc.) by heating the sections to 100˚C for

5-10 min in either pH 6.0 or pH 9.0 retrieval solution, depending

on the target antibody. The slides were then washed for 1 min in a

20 ml buffer solution (0.05 mol/l Tris/HCl, 0.15 mol/l NaCl, 0.05%

Tween-20, pH 7.6) at room temperature. Hydrophobic wells were

created using the Dako Pen (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Endogenous

peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Primary

antibodies [smooth muscle actin (mouse monoclonal, clone 1A4,

1:100, cat. no. M0851) and β-catenin (mouse monoclonal clone

β-catenin-1, 1:100, cat. no. M3539) both from Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.] were applied at room temperature for 80 min,

followed by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibody (1:200, cat. no. P0447, Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) and diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen for 15 min

each at room temperature. Counterstaining was performed with Gill

II hematoxylin for 30 sec, after which the slides were dried and

coverslipped. The post-operative HPE revealed a 4-cm, well-defined

mass with a rubbery tan-white fibrotic texture. It was diagnosed as

a low-grade spindle cell neoplasm, specifically a DTF, aided by

immunohistochemical staining, which yielded positive results for

smooth muscle actin and β-catenin (Fig. 1).

Follow-up and outcome

The post-operative period was uneventful, and the

patient was discharged from the hospital in good health after 2

days. The follow-up treatment plan included regular clinical

assessments and imaging as needed to monitor for recurrence, as

part of standard care for DTF, which has a risk of local

recurrence. Following a 6-month follow-up period, no recurrence was

reported.

Discussion

Herein, a literature review was also conducted to

identify reports on DTF of the head and neck through a Google

Scholar search using the key word ‘neck desmoid fibromatosis’. A

total of 7 cases of DTF in the head and neck region were reviewed

and these are summarized in Table

I. Of the 7 cases, 4 patients were female and 3 patients were

male, with ages ranging from 9 months to 42 years. The tumor in 4

cases was located in the neck, while the remaining tumors were

found in the mandible (n=2) and tongue (n=1). Among the cases

reviewed herein, the neck tumors generally progressed gradually,

occasionally causing symptoms, such as numbness, pain and weakness,

whereas tumors in other locations exhibited a more rapid

progression. The preferred imaging modalities for these tumors were

a CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Surgical

exploration with mass excision and clear safety margins was the

standard approach for managing these tumors. The majority of

patients experienced uneventful outcomes following surgery, apart

from 1 patient who developed temporary partial facial nerve

paralysis.

| Table ISummary of seven reported cases of

desmoid fibromatosis of the head and neck region identified in the

literature. |

Table I

Summary of seven reported cases of

desmoid fibromatosis of the head and neck region identified in the

literature.

| Authors | Age | Sex of included

patient | Presenting

compliant | Examination | Location | Imaging used for

diagnosis (CT/MRI) | Management | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kant et

al | 22 years | Female | Intermittent neck

pain, numbness, and weakness in her left shoulder | Weakness was evident

in her left shoulder and left elbow, and sensory loss was noted in

the left C3, C4, and C5 dermatomes | Neck | Well-defined

lobulated multicompartmental mass along the left brachial plexus

(C2-C6), occupying the paraspinal, prevertebral, and parapharyngeal

spaces, displacing the trachea and esophagus rightward and the left

carotid sheath anterolaterally. | Cervical exploration

and subtotal decompression of the tumor were performed | Unknown | (4) |

| | 36 years | Male | Gradually progressing

swelling on the left side of his neck | Neck mass was large,

firm, and non-tender, extending from the angle of the mandible to

the clavicle on the left side of the neck | Neck | Multilobulated

isointense mass on the left neck extending along the left brachial

plexus, medially into the neural foramina, and inferiorly into the

mediastinum. | Unknown | Unknown | (4) |

| Miyashita et

al | 9 months | Female | A tumor rapidly

enlarged, with part protruding from the tongue | The patient was

unable to fully close her mouth, and swallowing was aided by

compensatory motion of the unaffected side | Tongue | Whole-body CT

examination revealed no signs of any other tumoral lesions. MRI

revealed a large mass with contrast enhancement on the right side

of the tongue. MRI of the sagittal plane did not show the

possibility of infiltration into the root of the tongue. | A partial glossectomy

with a 5-mm safety margin and simultaneous reconstruction with a

local flap were performed | Good outcome without

recurrence after 1 year | (8) |

| Bouatay et

al | 38 years | Female | Recurrent desmoid

fibromatosis after 1 month of management | Painless, hard,

non-tender right laterocervical swelling (8 cm), fixed to the skin

and deep structures | Neck | Cervical CT scan

revealed a soft tissue mass infiltrating the deep lateral cervical

muscles and surrounding superficial and deep fat. | Complete tumor

resection | No local recurrence

was observed after 15 months | (11) |

| Alherabi et

al | 42 years | Female | Neck mass gradually

increasing in size | Hard, non-tender

swelling in the left posterolateral upper neck, fixed to the skin

and deep structures | Neck | Neck CT scan revealed

a soft tissue mass in the upper neck, lateral to the

sternocleidomastoid muscle, infiltrating deep lateral cervical

muscles and adjacent superficial and deep fat. | Mass widely excised

with a small remnant at the carotid bifurcation; 16-month CT showed

slow regrowth, treated with 60 Gy radiotherapy. The case

encountered temporary partial facial nerve paralysis | Good after a 2-year

follow-up with significant regression of the tumor | (14) |

| Sato et

al | 3 years | Male | Swelling of

submandibular region for 1 month | Inspection and

palpation revealed a 50x35 mm bony-hard, poorly mobile mass arising

from the left mandibular angle, expanding anteroinferiorly | Mandible | MRI revealed a

50x45x32 mm left mandibular tumor with unclear margins and high T2

signal; CT scan revealed moth-eaten mandibular destruction. | Surgical excision was

performed | Good without

recurrence after 25 months | (5) |

| Said-Al-Naief et

al | 8 years | Male | A rapidly enlarging,

painless mass along the right mandibular border for two

months. | Slight expansion of

the right mandibular border with overlying soft tissue

fullness. | Mandible | CT scan revealed an 8

mm right mandibular body mass with outer cortical destruction. | Mass resection with

wide margins of the right inferior mandibular border was

performed. | Good without

recurrence after 4.5 years | (15) |

DTF of the head and neck is a rare benign

mesenchymal tumor with an annual incidence of 2-4 cases per million

individuals (2,8). In the case series study by Hoos et

al (9), a sex predilection for

females was noted, whereas in the literature review performed in

the study by Miyashita et al (8), including 141 pediatric patients with

DTF of the head and neck aged birth to 18 years, no sex

predominance was observed. In the literature review performed in

the study by Miyashita et al (8), the mandible was the most common site

of involvement, accounting for 25% of cases. Additional reported

sites included the submandibular region, the infratemporal fossa,

the neck, the peritracheal area and the paraspinal region (8).

Empirical evidence indicates that among DTFs

involving the neck, the anterolateral aspect is a common site, with

the majority of patients presenting with a painless mass (60-94%).

However, neurogenic symptoms, such as pain or focal motor deficit

may be observed in a smaller proportion of cases (16-36%) (10). Compression of the brachial plexus

can result in symptoms, such as tingling, paresthesia, numbness and

weakness in hand muscles (1). A

rapidly enlarging DTF was also reported in a pediatric case in the

study by Miyashita et al (8). The case in the present study was a

2-year-old male presenting with a painless, slow-growing swelling

in the left submandibular region, which progressed over a period of

3 months.

The diagnosis of DTF in the head and neck region is

primarily based on a clinical presentation, imaging studies and

biopsy. While radiographs may be a useful initial diagnostic tool,

their findings can vary, and a definitive diagnosis usually

requires HPE (10,11). The accurate assessment of the

extent of the tumor and its relation to surrounding structures is

crucial for effective management. Advancing imaging techniques,

such as neck CT scans and MRI, play a key role in such an

assessment. MRI, in particular, is preferred for its superior soft

tissue contrast, which aids in more precise tumor delineation and

reduces the risk of damaging critical structures during surgery

(11). Typically, DTF exhibits

intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images (T1WIs),

similar to muscle tissue, and on T2-weighted images (T2WIs), where

the signal is lower than that of fat, but higher than that of

adjacent muscle. Fat-suppressed T2-weighted images often exhibit

increased signal intensity within these lesions. Areas with a low

signal intensity within DTF correspond to regions of higher

collagen content. Post-contrast imaging usually reveals moderate to

marked heterogeneous enhancement, reflecting the vascularity of the

lesion. In the case in the present study, a neck ultrasound

revealed a well-defined, lobulated, predominantly solid hypoechoic

left subcutaneous mass, measuring 38x31x27 mm, with mild

vascularity. Chest and abdominal contrasted CT scans yielded normal

findings.

The primary clinical differential diagnoses include

soft-tissue sarcoma, lymphoma, myositis ossificans and

arteriovenous malformation. Imaging often rules out the latter

conditions; however, distinguishing desmoid tumors from soft tissue

sarcomas can be challenging (12).

Desmoid tumors exhibit a spectrum of clinical behaviors, ranging

from indolent growth to aggressive local infiltration, which

significantly influences management strategies. Aggressive

variants, characterized by rapid growth, local invasion and a

higher risk of recurrence, often require multimodal treatment.

Post-operative radiation therapy (RT) is particularly considered in

cases where achieving negative surgical margins is challenging or

where tumors are located near critical structures, making complete

excision infeasible without undue morbidity (1,13).

Despite this, the role of RT remains controversial due to the

benign histological nature of desmoid tumors and the potential for

significant complications, coupled with a lack of prospective

clinical trials assessing its efficacy in reducing recurrence rates

(11,14,15).

Current evidence is derived from retrospective studies, which

suggest that combining RT with surgery may improve local control

rates, particularly in cases where wide margins are difficult to

achieve (8). Surgical resection

has traditionally been the primary treatment for primary and

recurrent desmoid tumors, aiming for tumor-free margins. A 5-year

local control rate of 80% with negative-margin resection has been

reported. However, some experts argued that achieving negative

margins may lead to unnecessary complications and may not prevent

local recurrence (11). The

recurrence rate among pediatric patients undergoing surgery has

been reported as 27.2% (8).

For benign or less aggressive variants, which

demonstrate slow growth and minimal recurrence risk, a more

conservative approach, such as watchful waiting, is gaining

acceptance, particularly for asymptomatic cases or tumors in

anatomically challenging locations. Given the challenges of

balancing treatment efficacy with minimizing overtreatment or

unnecessary morbidity, the management of desmoid tumors underscores

the need for a multidisciplinary approach. In pediatric patients

with DF that is unresponsive to non-surgical therapies, surgeons

may hesitate to pursue wide resections due to the substantial risk

of postoperative morbidity. When a large tumor is located near

vital structures, achieving adequate surgical margins can be

particularly challenging (8). The

literature review performed in the study by Miyashita et al

(8) revealed post-operative

complications in 13 patients (10.4%). Trismus was the most frequent

(n=6). A total of 2 patients developed secondary papillary

carcinoma following radiation therapy. Additional complications

included osteomyelitis (n=2), mild ptosis resulting from facial

nerve sectioning (n=1), restricted neck mobility (n=1) and

Claude-Bernard-Horner syndrome (n=1) (8). Individualized treatment planning,

guided by the biological behavior of the tumor, is essential to

optimize patient outcomes while addressing the limitations of

current evidence and therapeutic options (10,15).

In the present case report, the mass was successfully excised under

general anesthesia with no complications. No recurrence was

reported following 6 months of follow-up. The limitations of the

present case report include the inability to retrieve the

ultrasound figures due to poor archiving and CT scan figures for

the case, as they were conducted at an external facility.

In conclusion, DTF of the head and neck presents a

complex clinical scenario. Its rarity and the challenges associated

with diagnosis, location, and treatment necessitate careful

consideration, particularly in pediatric cases, in order to prevent

unnecessary interventions and complications. Ongoing research is

thus warranted to define standardized treatment protocols and

improve therapeutic outcomes for this challenging condition.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

FHK and AMS were major contributors to the

conception of the study, as well as to the literature search for

related studies. WNS, AAQ and SHH contributed to the clinical

management of the patient, assisted in data acquisition and

interpretation, and participated in the literature review and

manuscript preparation. HOB, HMD, ROM, ASM and KMS contributed to

the conception and design of the study, the literature review, the

critical revision of the manuscript, and in the processing of the

table. SHT was the radiologist who performed the assessment of the

case. AMA was the pathologist who performed the diagnosis of the

case. FHK and AMS confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient's parents for participation in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient's parents for the publication of the present and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kasper B, Ströbel P and Hohenberger P:

Desmoid tumors: Clinical features and treatment options for

advanced disease. Oncologist. 16:682–693. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Nuyttens JJ, Rust PF, Thomas CR Jr and

Turrisi AT III: Surgery versus radiation therapy for patients with

aggressive fibromatosis or desmoid tumors: A comparative review of

22 articles. Cancer. 88:1517–1523. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang CP, Chang YL, Ko JY, Cheng CH, Yeh CF

and Lou PJ: Desmoid tumor of the head and neck. Head Neck.

28:1008–1013. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kant S, Charan BD, Goel V, Das S, Sahu S,

Sharma R, Borkar S, Sebastian LJD and Garg A: Desmoid-type

fibromatosis of neck masquerading as nerve sheath tumors: two case

reports. Egyptian J Radiol Nuclear Med. 54(176)2023.

|

|

5

|

Sato K, Kawana M, Nonomura N and Takahashi

S: Desmoid-type infantile fibromatosis in the mandible: A case

report. Am J Otolaryngol. 21:207–212. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Prasad S, Nassar M, Azzam AY,

García-Muro-San José F, Jamee M, Sliman RK, Evola G, Mustafa AM,

Abdullah HO, Abdalla B, et al: CaReL Guidelines: A Consensus-based

guideline on case reports and literature review (CaReL). Barw Med

J. 2:13–19. 2024.

|

|

7

|

Abdullah HO, Abdalla BA, Kakamad FH, Ahmed

JO, Baba HO, Hassan MN, Bapir R, Rahim HM, Omar DA, Kakamad SH, et

al: Predatory publishing lists: A review on the ongoing battle

against fraudulent actions. Barw Med J. 2:26–30. 2024.

|

|

8

|

Miyashita H, Asoda S, Soma T, Munakata K,

Yazawa M, Nakagawa T and Kawana H: Desmoid-type fibromatosis of the

head and neck in children: A case report and review of the

literature. J Med Case Rep. 10(173)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hoos A, Lewis JJ, Urist MJ, Shaha AR,

Hawkins WG, Shah JP and Brennan MF: Desmoid tumors of the head and

neck-a clinical study of a rare entity. Head Neck. 22:814–821.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhou MY, Bui NQ, Charville GW, Ghanouni P

and Ganjoo KN: Current management and recent progress in desmoid

tumors. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 31(100562)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Bouatay R, Bouaziz N, Harrathi K and

Koubaa J: Aggressive and recurrent desmoid tumor of the head and

neck: A therapeutic challenge. Otolaryngol Case Rep.

30(100578)2024.

|

|

12

|

de Bree E, Zoras O, Hunt JL, Takes RP,

Suárez C, Mendenhall WM, Hinni ML, Rodrigo JP, Shaha AR, Rinaldo A,

et al: Desmoid tumors of the head and neck: A therapeutic

challenge. Head Neck. 36:1517–1526. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK and Ballo MT:

Long-term outcomes for desmoid tumors treated with radiation

therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 71:441–447. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Alherabi AZ, Marglani OA, Bukhari DH and

Al-Khatib TA: Desmoid tumor (fibromatosis) of the head and neck.

Saudi Med J. 36(101)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Said-Al-Naief N, Fernandes R, Louis P,

Bell W and Siegal GP: Desmoplastic fibroma of the jaw: A case

report and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

Oral Radiol Endod. 101:82–94. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|