1. Introduction

Cancer is a medical condition in which somatic cells

undergo genetic or epigenetic changes, causing aberrant cell

proliferation that can spread to other parts of the body (1). Breast cancer (BC) is one of the most

detrimental and heterogeneous diseases in modern times, affecting a

large number of individuals globally. It is the second most common

type of cancer among females worldwide, accounting for

685,000-related deaths (16% of the total female cancer-related

deaths) (2,3). In India, BC has become the most

frequent type of cancer among women, particularly in younger age

groups (4). BC is a heterogeneous

disease with various clinical, molecular and biological features;

some tumors exhibit a high estrogen receptor expression, which

influences the methods of treatment, as well as the prognosis of

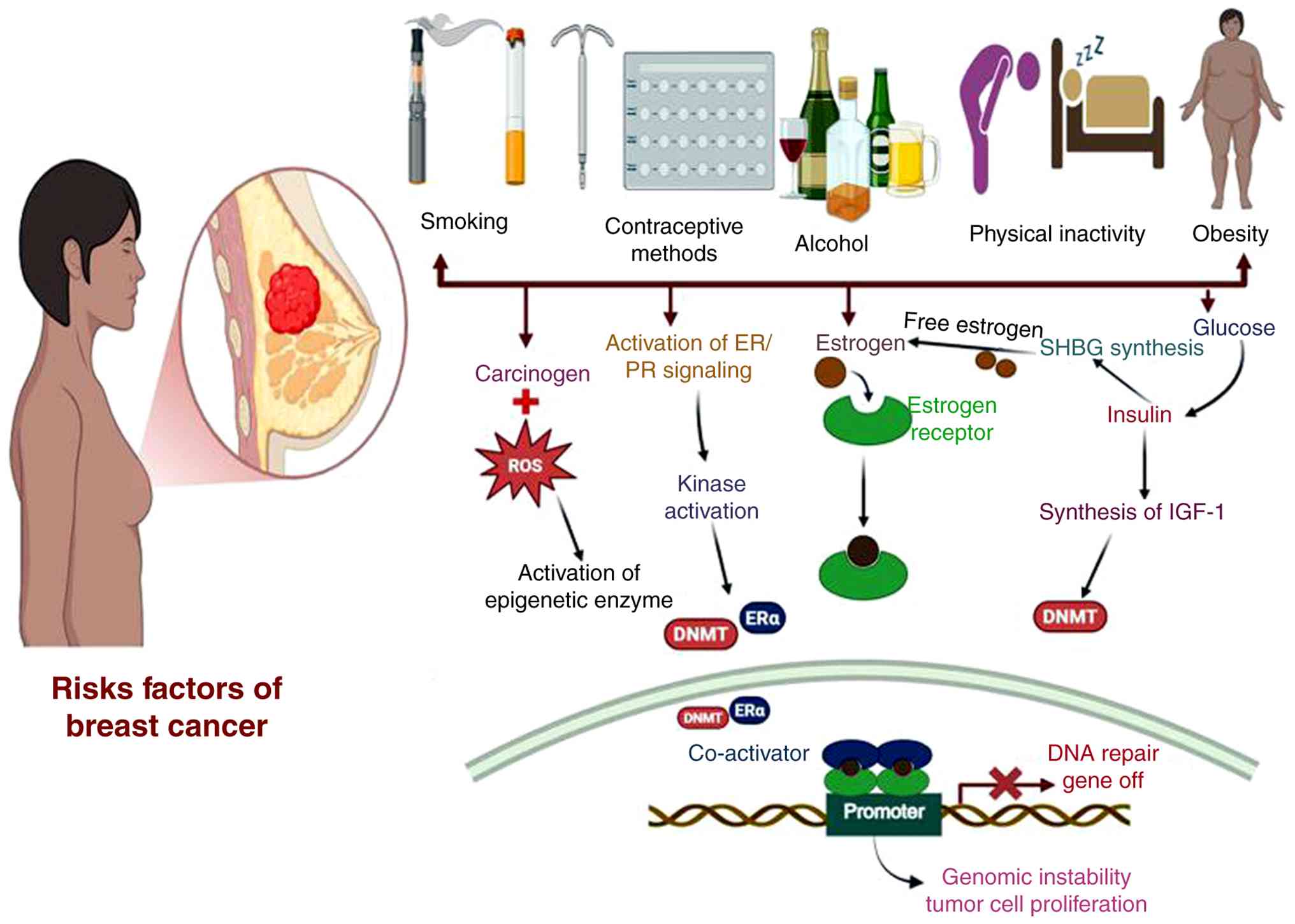

patients (5). Numerous factors

influence the development of breast tumors, as illustrated in

Fig. 1.

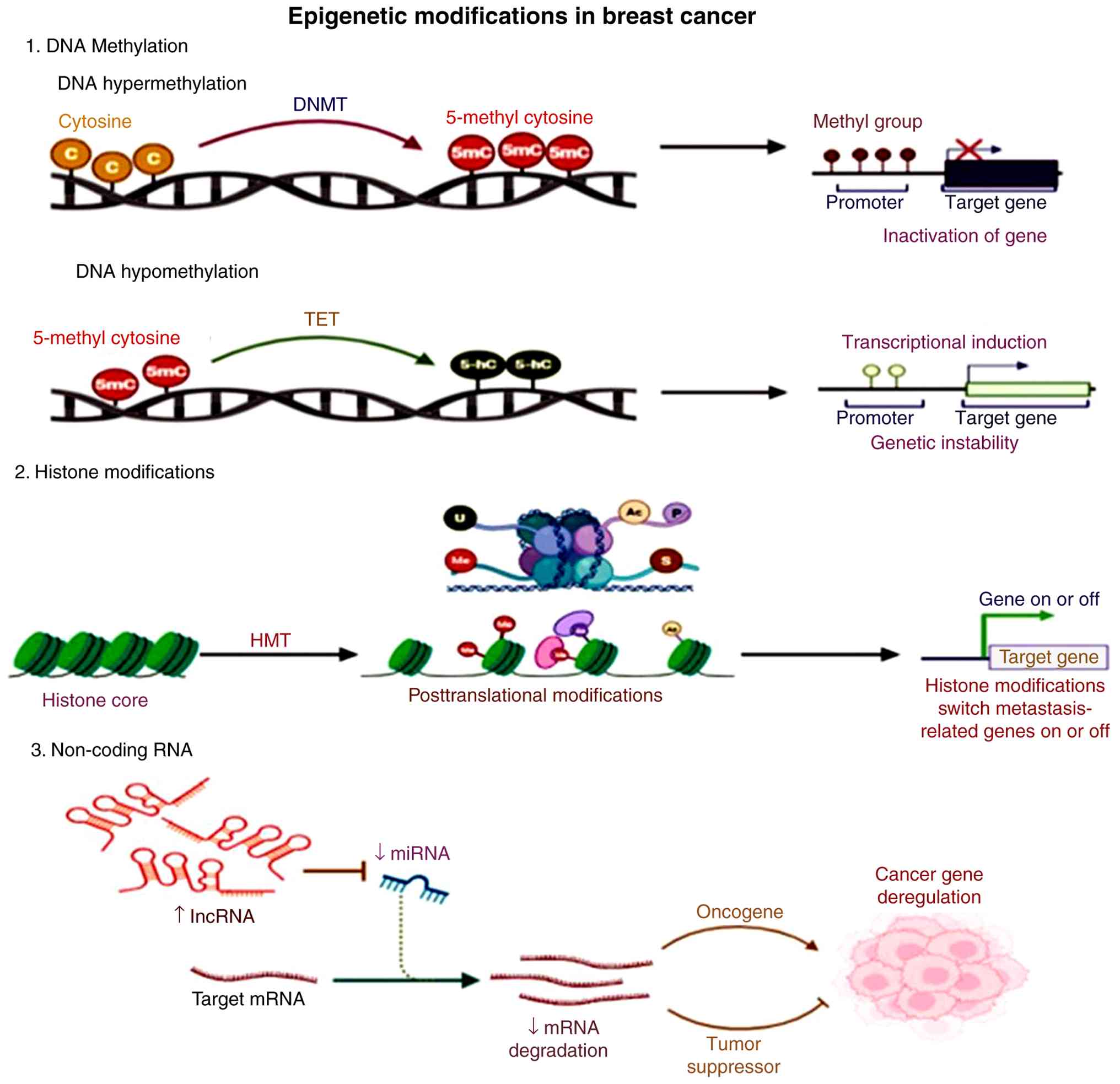

The processes of epigenetic modification [such as

DNA methylation, the post-transcriptional modification of histone

proteins and regulation through non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)] are

critical in controlling the normal functions of a cell throughout

the developmental and differentiation states (6). These processes also help cells adapt

to environmental changes, including dietary changes or exposures to

chemicals or radiation. It is known that the action of cigarette

smoke and hormones is responsible for inducing epigenetic changes.

However, aberrant epigenetic changes lead to the development of

cancer (7). A key mechanism of

gene inactivation in breast cancer is promoter CpG island

hypermethylation. which targets CG-rich regions associated with

promoters of protein-coding genes (8). This epigenetic damage inactivates

several cellular processes, such as DNA repair, leading to mutator

pathways. Notably, patients with breast cancer frequently exhibit

hypermethylation of DNA repair genes, including breast cancer gene

1 (BRCA1), breast cancer gene 2 (BRCA2),

Abraxas1/BRCA1 A complex subunit (ABRA1), MRE11,

BRCA1-associated RING domain 1 (BARD1), mediator of DNA

damage checkpoint 1 (MDC1), ring finger protein (RNF)168,

UBC13, partner and localizer of BRCA2 (PALB2), RAD50,

RAD51, RAD51C, RNF8, NBS1, CtIP and ATM. The ability of

cells to respond to DNA damage is disrupted by epigenetic

alterations, resulting in increased tumor growth. Given that

epigenetic alterations are potentially reversible, they are an

attractive target for the development of treatments (9). Surgical intervention, chemotherapy

and radiation therapy continue to form the backbone of treatment

options for breast cancer; however, there are limitations to their

effectiveness, including dose-dependent toxicity, limited

selectivity, the potential for treatment resistance and significant

side-effects leading to the damage of non-cancerous cells.

Metastatic disease remains one of the key challenges of treatment

and is the principal cause of mortality in women with breast cancer

(10). Dietary phytochemicals

(natural compounds derived from plants) are being recognized as

potentially effective chemopreventive and therapeutic agents for

the treatmetn of breast cancer due to their low toxicity levels,

minimal side effects, affordability, and ease of access in

comparison to synthetic pharmaceuticals (11). Natural plant extracts, such as

Piper longum, Curcuma longa, Withania somnifera, Nigella sativa,

Amora rohituka and Dimocarpus longan contain anticancer

compounds with demonstrated anti-BC characteristics (12). This approach is particularly

promising as epigenetic changes, unlike genetic mutations, are

reversible and influence early cancer progression. Although this

exhibits immense potential, a knowledge gap currently exists in the

research of phytochemicals and their role in epigenetics in BC. The

present review thus aimed to fill this gap in the current

literature. The present review discusses the findings from the most

contemporary literature available with regard to the reversals of

hypermethylation in DNA repair genes by phytochemicals and their

mechanisms of action in BC.

2. Epigenetic modifications in breast

cancer

The term ‘epigenetics’, originally used by

Waddington in 1942, describes genetic, reversible modifications in

gene expression without changing the DNA sequence (13). Breast cancer often involves

epigenetic reprogramming despite its genetic origin (14). These epigenetic alterations include

DNA methylation, histone modifications and ncRNA expression

(15), as illustrated in Fig. 2.

DNA methylation

DNA methylation is an epigenetic process linked to

cell development and various critical activities. Aberrant

methylation patterns have been observed in cancer cell genomes

(16). It is a reversible process

in which methyl groups are introduced to the fifth carbon position

of the cytosine from S-adenosyl methionine. Of note, two types of

methylation exist: Maintenance methylation (when CpG dinucleotides

on a single strand of DNA are methylated) and de novo

methylation (when CpG dinucleotides on both of the strands are

unmethylated) (17). DNA

methylation is a reversible process facilitated by DNA

methyltransferases (DNMTs). DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3A and

DNMT3B encode proteins with different functional

specificities. As previously demonstrated, two patterns of aberrant

methylation have been identified: Global hypomethylation throughout

the genome and hypermethylation at CpG islands within promoter

regions (18,19).

DNA hypomethylation

Global DNA hypomethylation, a cancer hallmark

coexisting with focal CpG island hypermethylation, involves

genome-wide loss of cytosine methylation (20). Mechanistically driven by an

impaired DNMT1 maintenance, deregulated DNMT3A/3B

activity and aberrant TET-mediated demethylation, and reduced

5-methylcytosine levels are associated with tumor progression and a

poor survival (21). Functionally,

hypomethylation destabilizes heterochromatin, causing chromosomal

instability. It reactivates transposable elements, inducing

mutagenesis, and aberrantly activates oncogenes and

metastasis-promoting genes (22).

DNA hypermethylation

The aberrant addition of methyl groups to cytosines

in CpG dinucleotides, particularly within promoter-associated CpG

islands, is a hallmark epigenetic alteration in cancer, causing

stable gene silencing without altering the DNA sequence. In cancer,

~5-10% of promoter CpG islands become hypermethylated, repressing

tumor suppressor genes involved in cell cycle control, DNA repair

and apoptosis (e.g., CDKN2A, MLH1 and BRCA1),

contributing to oncogenesis (23,24).

These reversible changes provide targets for epigenetic therapy, as

well as biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic

stratification (25). Both

modifications have commonly been documented in BC and are greatly

affected by environmental factors such as aging, stress, alcohol

consumption and air pollution (26).

Histone modifications

DNA wraps around a histone octamer in the nucleus.

The histone tails are sensitive to several covalent

posttranslational modifications (PTMs) that regulate chromatin

state. Changes in histone PTM patterns have been widely associated

with cancer (27). Key

modifications include the following:

Histone phosphorylation. The addition of

phosphate groups promoting chromatin relaxation, critical for DNA

damage responses (notably γ-H2AX at Ser139), transcriptional

regulation and mitotic chromosome condensation (28).

Histone acetylation. Acetylation by histone

acetyltransferases leads to decreased histone-DNA interaction,

creating euchromatin. This is strongly associated with gene

transcription activation. Histone deacetylases remove acetyl

groups, compacting chromatin and inhibiting transcription (29).

Histone ubiquitylation. H2A ubiquitination

(Lys119) usually causes gene repression, while H2B ubiquitination

(Lys120) aids transcription and is required prior to methylation

(30).

Histone sumoylation. SUMO conjugation drives

transcriptional repression and chromatin compaction, often

antagonizing acetylation and ubiquitination (31).

Histone methylation. This occurs on lysine

and arginine residues with variable outcomes. Activating markers

include H3K4me3; repressive markers include H3K9me3 and H3K27me3.

Histone methyltransferases and demethylases control methylation

dynamics (32).

ncRNA expression

Non-coding RNAs lack protein-coding ability, and

~52% of the human genome has been encoded, although only 1.2%

codify proteins. ncRNAs are categorized into ‘housekeeping ncRNAs’

(tRNAs, rRNAs, snRNAs and snoRNAs) and ‘regulatory ncRNAs’

(lncRNAs, >200 nucleotides; and short ncRNAs, <200

nucleotides) (33,34). They play a critical role in

controlling signaling pathways linked to tumor development, spread

and therapeutic resistance (35).

Short non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs). snRNAs are a

diverse group under ~200 nucleotides, including microRNAs (miRNAs),

small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs),

that regulate gene expression primarily at the post-transcriptional

level. These molecules contribute to chromatin modulation, cell

differentiation, stress responses and disease processes (36,37).

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). These RNA

species are longer than 200 nt without protein-coding potential

(33). The human transcriptome has

~10,000 lncRNAs. They function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors,

affecting cancer cell growth, apoptosis, metabolic processes,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), metastasis and treatment

resistance. lncRNAs are usually exclusive to a particular tumor

subtype, and BC exhibits abnormal expression levels of several

lncRNAs (34,38).

3. Hypermethylated DNA repair genes in

breast cancer

DNA repair processes play a crucial role in

preserving genomic stability and limiting the growth of mutations

that may lead to cancer (39). In

BC, these mechanisms are frequently affected not only by genetic

mutations, but also by epigenetic alterations, particularly

promoter hypermethylation, that can silence essential DNA repair

genes without affecting their DNA sequence (40). In BC, promoter hypermethylation is

known to silence certain key DNA repair genes, as discussed below

and presented in Table I (41-67).

| Table IRole of hypermethylated DNA repair

genes in breast cancer. |

Table I

Role of hypermethylated DNA repair

genes in breast cancer.

| Gene | Function in DNA

repair | Impact of

hypermethylation in breast cancer | Locus | (Refs.) |

|---|

| MSH6 | Forms MutSα complex

with MSH2 to repair base mismatches and small

insertion/deletion loops, preserving genomic stability. | Promoter

hypermethylation in both DCIS and IDC leads to early gene

silencing, impairing mismatch repair and promoting genomic

instability. | 2p16 | (41,42) |

| MDC1 | Scaffold protein in

DNA damage response, binds γH2AX at DSBs, recruits MRN complex,

ATM, RNF8, BRCA1, 53BP1, amplifies ATM signaling |

Hypermethylation/downregulation linked to

radioresistance, nodal failure, poor prognosis, and genomic

instability | 6p21.3 | (43,44) |

| RNF168 | E3 ubiquitin

ligase; ubiquitinates H2A at K13/K15, recruits 53BP1, BRCA1, PALB2,

promotes homologous recombination (HR) | Hypermethylation

may reduce expression, impair DNA repair, increase sensitivity to

DNA damage, or drive endocrine resistance | 3q29 | (45,46) |

| RAD51 | Key protein in

homologous recombination repair (HRR), mediates HR intermediate

formation and resolution | Promoter

hypermethylation causes gene silencing, seen in TNBC, linked to HR

deficiency, and poor prognosis | 17q23 | (47,48) |

| MLH1 | Key component of

the mismatch repair (MMR) system, forms a heterodimer with

PMS2 to correct DNA replication errors | Promoter

hypermethylation silences the gene, seen in ~43.5% of breast

cancers; linked to advanced stages, genomic instability, and

disease progression | 3p22.2 | (49,50) |

| RAD50 | key element of the

MRN complex that enables checkpoint activation, telomere

maintenance, and DSB repair through HR and Non-Homologous End

Joining (NHEJ) | Promoter

hypermethylation reduces expression, linked to impaired DNA repair

and increased breast malignancy risk | 5q31.1 | (51,52) |

| MRE11 | MRN complex member;

detects DSBs, initiates end resection, activates ATM, supports

HR/NHEJ | Reduced expression

(~31%) impairs repair; linked to BRCA1/ATM deregulation and

increased risk | 11q21 | (53,54) |

| BRCC36 | BRCA1-A complex

DUB; removes K63-linked ubiquitin, essential for BRCA1 activation

and 53BP1 recruitment | Overexpressed in

breast tumors; may disrupt BRCA1 function; silencing increases

radiosensitivity | Xq28 | (55,56) |

| BRCA1 | HR repair; RAD51

recruitment | Well-established

promoter hypermethylation in sporadic breast cancer → BRCA1

silencing & HRD | 17q12-21 | (57-59) |

| BRCA2 | HR mediator; loads

RAD51 | Promoter

hypermethylation in subsets, including DCIS → reduced HR | 13q12 | (41,59,60) |

| PALB2 | Bridges

BRCA1 and BRCA2; facilitates RAD51 loading, thereby

enabling HR repair of DSBs. | Rare but reported

promoter methylation → reduced HR competence in subsets | 16p12.2 | (61,62) |

| ATM | Serine/threonine

kinase that senses DSBs and activates DDR: phosphorylates key

effectors(e.g., p53, BRCA1, CHK2), triggering cell-cycle

checkpoints, DNA repair, or apoptosis. | Hypermethylation →

downregulation, larger tumors and an advanced stage | 11q22.3 | (63-65) |

| RNF8 | E3 ligase promotes

K63-Ub chains to recruit repair proteins | Direct methylation

is rare; aberrant expression, mostly upregulation, contributes to

EMT and chemoresistance | 6p21.3 | (66,67) |

MutS homolog 6 (MSH6)

MSH6 partners with MSH2 to form the

MutSα complex, which recognizes and repairs base-base mismatches

during DNA replication. In BC, promoter hypermethylation silences

MSH6 expression in both ductal carcinoma in situ

(DCIS) and invasive carcinomas, compromising mismatch repair (MMR)

fidelity and elevating mutation rates (41,42).

TCGA bioinformatic analyses have demonstrated inverse correlations

between promoter methylation and gene expression, establishing

MSH6 loss as an early driver of genomic instability in

breast tumorigenesis (42,68).

MDC1

MDC1 functions as a molecular scaffold at DNA

double-strand breaks (DSBs), binding phosphorylated histone H2AX

(γH2AX) and orchestrating the recruitment of the MRN complex,

ATM kinase, RNF8, BRCA1 and 53BP1.

Promoter-associated transcriptional downregulation in BC is

associated with genomic instability, radioresistance, nodal

metastasis and adverse clinical outcomes. In silico network

analyses position MDC1 as a central signaling hub within the

ATM-BRCA1-RNF8 axis, where its functional loss accelerates

DNA damage accumulation and impairs checkpoint responses (43,44).

RNF168

RNF168 (3q29), an E3 ubiquitin ligase,

catalyzes histone H2A ubiquitination at lysines 13 and 15,

facilitating the recruitment of 53BP1, BRCA1 and

PALB2 to DSB sites for homologous recombination (HR).

TCGA-BRCA and METABRIC dataset analyses reveal that promoter

hypermethylation suppresses RNF168 expression, resulting in

HR deficiency, heightened sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and

potential endocrine therapeutic resistance (45,46).

TCGA data indicate RNF168 overexpression in

BRCA1-mutant BCs and in BCs with HR deficiency (HRD), driven

mainly by copy-number amplification and enriched in basal-like

tumors. A high expression of RNF168 is associated with HRD

mutational signature 3 and a worse survival, while lower

RNF168 levels are associated with improved outcomes and a

reduced risk of developing BC in BRCA1 mutation carriers

(69).

RAD51

RAD51 (17q23) is the central recombinase in

homologous recombination repair, mediating strand invasion and the

resolution of HR intermediates. Integrative analyses of TCGA and

DNA methylation arrays identify promoter hypermethylation-mediated

RAD51 silencing predominantly in triple-negative breast

cancer (TNBC), where it is associated with HR-deficiency molecular

signatures and reduced transcript abundance (47,48).

TCGA and drug-response datasets demonstrate that a low expression

of RAD51 is associated with a poor overall survival, but

increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging chemotherapy, particularly in

BC, reflecting homologous recombination deficiency that can be

therapeutically exploited (70).

MLH1

MLH1 heterodimerizes with PMS2 to

execute mismatch repair, correcting replication errors including

base mismatches and insertion-deletion loops. Promoter

hypermethylation silences MLH1 in ~43.5% of BCs, as

demonstrated by multi-platform in silico analyses

demonstrating strong inverse methylation-expression correlations

(49,50). The loss of MLH1 precipitates

MMR deficiency, microsatellite instability, elevated tumor

mutational burden, and the progression toward advanced, genomically

unstable disease states (71).

RAD50

RAD50 is a core part of the ATPase-containing

MRN complex, which is critical for the recognition of DSBs, the

activation of ATM, telomere maintenance, and selection of DSB

repair pathways between HR and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)

repair (51,52). Multi-omics analysis has

demonstrated that the hypermethylation of promoters suppresses

RAD50 transcription and disrupts the stability of the MRN

complex, resulting in improper DSB signaling, genomic instability

and an increased risk of developing BC. RAD50 suppression is

particularly implicated in TNBC carcinogenesis and chemotherapeutic

resistance (72).

MRE11

MRE11 provides the nuclease activity within the MRN

complex, initiating DNA end resection, activating ATM-dependent

checkpoints, and supporting both HR and NHEJ pathways (53,54).

Previously, TCGA-BRCA analyses demonstrated a reduced MRE11

expression in a subset of breast cancers, while copy-number

alterations affecting MRE11 were observed at a lower frequency. A

low expression of MRE11 was shown to be associated with

differential gene expression and pathway enrichment indicating

impaired ATM signaling and homologous recombination,

consistent with genomic instability and aggressive tumor phenotypes

(73).

BRCC36 (BRCC3)

BRCC36 (Xq28) is a K63-specific

deubiquitinase within the BRCA1-A complex that removes ubiquitin

chains to fine-tune BRCA1 activation and regulate 53BP1 recruitment

during DSB repair pathway selection (55,56).

TCGA-BRCA transcriptomic data have revealed the

dysregulation/overexpression of BRCC36 in BC (74). Network and pathway analyses have

linked altered BRCC36 levels to a perturbed BRCA1-A complex

function and ubiquitin-dependent DSB repair, with computational

models suggesting the modulation of DSB pathway choice and

potential radiosensitization upon BRCC36 inhibition

(74).

BRCA1

BRCA1 is a tumor suppressor orchestrating

homologous recombination, cell cycle checkpoints, and

transcriptional regulation. In sporadic BC, promoter

hypermethylation constitutes a major mechanism of BRCA1

silencing, producing HR deficiency, triple-negative phenotype

enrichment, and synthetic lethality with PARP inhibitors (57-59).

Integrated bioinformatics analyses of BC cohorts have demonstrated

that BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation is tightly linked to

reduced BRCA1 expression and

homologous-recombination-deficient genomic and transcriptomic

signatures, closely mirroring BRCA1-mutated tumors and

supporting epigenetic BRCA1 silencing as a functional driver

of HR deficiency (75).

BRCA2

BRCA2 functions as a tumor suppressor that

regulates RAD51 nucleoprotein filament assembly during

HR-mediated DSB repair. Promoter hypermethylation represents an

early and frequent event in breast carcinogenesis, detected even in

DCIS, where it induces gene silencing, genomic instability and

repair incompetence (41,60). TCGA-based methylation and

integrative bioinformatic analyses link BRCA2 promoter

hypermethylation in pre-invasive breast lesions to homologous

recombination deficiency signatures and increased genomic

instability (76).

PALB2

PALB2 serves as a molecular bridge connecting

BRCA1 and BRCA2, facilitating RAD51 loading

and enabling efficient HR. While germline PALB2 mutations

confer hereditary breast cancer susceptibility, somatic promoter

hypermethylation also suppresses expression in a subset of sporadic

cases, resulting in HR deficiency and disease progression (61,62).

Bioinformatics methylome profiling in early-onset BC samples has

revealed increased methylation at PALB2 promoter-associated

CpG probes in tumor DNA compared with matched blood DNA, consistent

with potential epigenetic modulation of PALB2 expression in

a subset of cases (77).

ATM

ATM encodes a master checkpoint kinase that

phosphorylates numerous substrates, including p53, BRCA1 and

CHK2 in response to DSBs, orchestrating cell cycle arrest

and repair pathway activation. Promoter hypermethylation reduces

ATM expression in BC, and is associated with a larger tumor

size, advanced stage and an older patient age (63-65).

TCGA-based repair signature analyses have associated ATM

silencing with checkpoint deficiency and impaired DSB repair

capacity, supporting its utility as a prognostic and predictive

biomarker in sporadic disease (78).

RNF8

RNF8 (6p21.3) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase

initiating the ubiquitin cascade required for BRCA1 and

53BP1 recruitment to DSBs, promoting high-fidelity HR, while

suppressing mutagenic NHEJ. Paradoxically, RNF8 is

frequently overexpressed in BC, where it drives EMT, metastasis and

chemoresistance through the activation of the Twist and β-catenin

signaling pathways (66,67). Bioinformatics analyses of BC

datasets has demonstrated that RNF8 promoter methylation is rare;

however, RNF8 is transcriptionally dysregulated and embedded

in DDR networks linked to BRCA1-RAD51-ATM signaling,

indicating an altered homologous recombination and DDR pathway

balance (79).

4. Phytochemicals causing the reversal of

hypermethylation in DNA repair genes

The hypermethylation of functionally significant

genes has been observed in breast carcinoma; silencing of these

genes is crucial for carcinogenesis and tumor development (40). Treatment options for BC include

surgery, chemoradiotherapy, hormone treatments, monoclonal

antibodies, immunotherapy, nanomedicines and small molecule

inhibitors. Conventional medicines have limitations, including

resistance, a low efficacy and adverse effects, which limit their

clinical uses. Anticancer medications derived from plants that have

limited or no adverse effects may be a beneficial alternative to

chemotherapy (12). The ‘phyto’ in

the word phytochemicals is derived from the Greek word, meaning

‘plant’. Therefore, phytochemicals are plant compounds (80). Phytochemicals are plant-based

bioactive molecules that plants manufacture to protect themselves.

Over a thousand phytochemicals have been identified to date and can

be obtained from various foods, including whole grains, fruits,

vegetables, nuts, and herbs (81).

Phytochemicals primarily inhibit BC by reducing the

proliferation of cells, inducing apoptosis, limiting cancer cell

dissemination, inhibiting angiogenesis and impairing cancerous cell

migration. These chemicals have also been shown to improve the

curative effectiveness of other anticancer medications, sensitize

cells to radiation, and prevent resistance to therapy in malignant

tissue (82). Epigenetic

alterations are modulated by phytochemicals as inhibiting DNMTs

(83), modulating histone

acetylation and methylation, and affecting ncRNAs (84). Some of the phytochemicals with

targeted genes and their mechanisms are presented in Table II (85-97).

| Table IIPhytochemicals targeting DNA repair

genes through epigenetic modulation in breast cancer. |

Table II

Phytochemicals targeting DNA repair

genes through epigenetic modulation in breast cancer.

| Phytochemical | Source (plant

part) | Target gene | Mechanism | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Curcumin | Turmeric

(rhizome) | BRCA2 ↓,

RAD51 ↓, PARP1 modulation | In vitro

studies report reduced BRCA2 and RAD51 stability,

suggesting homologous recombination deficiency and increased

PARP-inhibitor sensitivity | (85-87) |

| Genistein | Soybeans

(seeds) | BRCA1 ↑,

BRCA2 ↑, ATM ↑ (transcriptional); MLH1

demethylation | In vitro and

limited in vivo data suggest DNMT inhibition and partial

promoter demethylation, leading to reactivation of BRCA1 and

MLH1 | (88,89) |

| Resveratrol | Grapes, berries,

red wine (skin, seeds) | RAD51 | In vitro

evidence indicates RAD51 downregulation, suggesting impaired

homologous recombination and increased DNA-damage sensitivity | (90) |

| Quercetin | Apples, onions,

grapes (fruits, peels) | RAD51,

Ku70, XRCC1 (DNA repair mediators) | In vitro

studies report reduced expression of multiple DNA repair genes,

suggesting global suppression of repair capacity | (91) |

| Thymoquinone | Black cumin

(seeds) | RAD51, Ku70,

XRCC1 (DNA repair) | In vitro

findings suggest decreased repair gene expression and increased DNA

damage markers, indicating impaired DNA repair | (91) |

| Berberine | Barberry

(roots/bark) |

XRCC1-mediated BER; BRCA1

axis (sensitization) | Preclinical studies

report inhibition of XRCC1-mediated BER, sensitizing cells

to DNA-damaging agents; BRCA1 effects are indirect. | (92) |

| Epigallocatechin

gallate | Green tea

(leaves) | DNMT1 ↓ →

MLH1 re-expression, BRCA1 promoter demethylation

reported | In vitro

studies demonstrate DNMT1 inhibition and re-expression of

MLH1; BRCA1 demethylation has been reported in select

models | (93,94) |

| Withaferin-A | Ashwagandha

(leaves, roots) | BRCA1 ↓,

ATR/ATM-DDR modulation | Preclinical

evidence suggests BRCA1 degradation and ATM/ATR-DDR

modulation, resulting in reduced homologous recombination | (95-97) |

5. Critical analysis, limitations and future

directions

Although DNA repair gene hypermethylation is widely

reported in BC, much of the evidence remains correlative as it

relies heavily on in vitro studies and bulk bioinformatic

datasets that fail to reflect the true biological complexity of

tumors. Large-scale methylation analyses demonstrate extensive

inter- and intra-tumoral epigenetic heterogeneity, indicating that

simplified models cannot fully capture patient-specific variation

(98). Moreover, the BC

microenvironment, including stromal and immune components, strongly

influences epigenetic states, yet this context is largely absent

from current experimental systems (99). Methodological variability across

methylation assays, histone modification profiling, and ncRNA

detection platforms further contributes to inconsistent and

difficult-to-compare findings in the epigenetics literature

(100). Notably, hypermethylation

in several DNA repair genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51,

MLH1, MSH6, ATM, and components of the MRN complex

(MRE11-RAD50-NBS1), is frequently reported in BC; yet,

direct evidence demonstrating that these epigenetic alterations

consistently translate into functional protein loss or impaired DNA

repair activity remains limited (101). A number of published studies rely

on simplified experimental systems, including in vitro cell

line models, simplified animal models and bulk bioinformatic

analyses, which do not adequately capture the cellular

heterogeneity, tumor microenvironment and overall biological

complexity of primary breast tumors (14,26,78).

For this reason, determining the functional impact of

hypermethylation may be challenging as it remains unclear how this

process will affect cellular behavior. In vitro examples

have demonstrated that promoter hypermethylation can be reversed,

for example, with genes such as BRCA1, XRCC1, ATM and

RAD51; however, the majority of these studies are not

supported by comprehensive functional assays, either in terms of

confirming successful restoration of DNA repair function or

establishing the stability, reproducibility and long-term

biological impact of such reversions. Furthermore, in the majority

of cases, reversal of hypermethylation, in addition to being

unstable, may not have any biological significance in the long

term.

Such uncertainties in scientific research are

inclusive of the challenges related to the developing a medicinal

approach targeting hypermethylation reversal, particularly those

which are phytochemical-based. Variability in phytochemical

composition with respect to species, environmental factors, storage

and processing is very high, thus rendering standardization

difficult (102). Moreover, study

designs for establishing direct causality between phytochemical

consumption and subsequent cancer repression are not very feasible

due to confounding variables, such as dietary habits (103). The limited understanding of

phytochemical pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, in addition, adds

complexity to predictive models of safety, efficacy and interaction

with conventional therapies (92).

Bioavailability is an issue with a number of phytochemicals, in

which a large absorption, low solubility, rapid metabolism and poor

tissue biodistribution frequently require supraphysiological

concentrations in vitro, which are not attainable in

vivo (104). The precise

biochemical mechanisms for their actions on epigenetic targets have

not yet been fully understood, and numerous compounds have

pleotropic or context-dependent effects that limit their

reliability as targeted epigenetic modulators (82).

Collectively, these limitations suggest more

integrated and rigorous research is required. Future studies

should, whenever possible, evaluate not only methylation and gene

expression, but also quantify endogenous protein levels, protein

abundance and functional DNA repair restoration in clinically

relevant models. In addition, enhancing the phytochemical

pharmacokinetics and developing standardized extraction protocols,

the use of combinatorial therapeutic approaches might help in

overcoming current barriers (105). Ultimately, well-designed clinical

trials with clearly defined molecular clinical endpoints become the

key to unlocking the true therapeutic potential of DNA repair gene

reversal and hypermethylation in breast cancer.

6. Conclusion

BC is a major concern that arises due to both

hereditary and epigenetic modifications, with hypermethylation of

DNA repair genes playing a critical role in carcinogenesis in BC.

Such epigenetic modifications lead to the inactivation of tumor

suppressor genes, resulting in DNA repair systems and promoting

genomic instability. Patients with cancer usually undergo

unconventional treatment methods, which have weaknesses, including

toxicity, resistance and negative side-effects. However, the use of

phytochemicals appears to be a promising strategy to reverse such

aberrant epigenetic modifications in BC, having multiple

advantages, including low toxicity, cost-effectiveness and

potential synergy with standard treatments. Phytochemicals are

natural molecules found in fruits, vegetables and medicinal plants

that are essential components of the human diet and have a large

impact in the direction of therapy of cancer. The present review

discussed some phytochemicals, such as curcumin, that have shown a

committing effect in targeting BC hypermethylated DNA repair

genes.

Despite their potential however, several

restrictions and challenges related to variability in the compound

composition of phytochemicals, low bioavailability, difficult

standardization and reproducibility, and a lack of clinical

validation prevent them from being widely used. Future studies are

thus required to elucidate the epigenetic effects of BC in order to

overcome these obstacles. This will aid in the development of more

individualized targets for phytochemical-based therapies, which

also provide a low-toxicity method of reactivating genes involved

in DNA repair and improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the

School of Biosciences and Technology, Galgotias University, Greater

Noida, India, in terms of access to library resources, online

databases, and research facilities for the preparation of this

review.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

TG wrote the main manuscript, and AKJ provided

conceptual guidance. Both authors reviewed, and have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Saini A, Kumar M, Bhatt S, Saini V and

Malik A: Cancer causes and treatments. Int J Pharm Sci Res.

11:3121–3134. 2020.

|

|

2

|

Fatima N, Liu L, Hong S and Ahmed H:

Prediction of breast cancer, comparative review of machine learning

techniques, and their analysis. IEEE Access. 8:150360–150376.

2020.

|

|

3

|

Mathur R, Jha NK, Saini G, Jha SK, Shukla

SP, Filipejová Z, Kesari KK, Iqbal D, Nand P, Upadhye VJ, et al:

Epigenetic factors in breast cancer therapy. Front Genet.

13(886487)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Mehrotra R and Yadav K: Breast cancer in

India: Present scenario and the challenges ahead. World J Clin

Oncol. 13(209)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Mohanad M, Hamza HM, Bahnassy AA, Shaarawy

S, Ahmed O, El-Mezayen HA, Ayad EG, Tahoun N and Abdellateif MS:

Molecular profiling of breast cancer methylation pattern in triple

negative versus non-triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep.

15(6894)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Buocikova V, Rios-Mondragon I, Pilalis E,

Chatziioannou A, Miklikova S, Mego M, Pajuste K, Rucins M, Yamani

NE, Longhin EM, et al: Epigenetics in breast cancer therapy-new

strategies and future nanomedicine perspectives. Cancers (Basel).

12(3622)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Klibaner-Schiff E, Simonin EM, Akdis CA,

Cheong A, Johnson MM, Karagas MR, Kirsh S, Kline O, Mazumdar M,

Oken E, et al: Environmental exposures influence multigenerational

epigenetic transmission. Clin Epigenetics. 16(145)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kang Z, Wang J, Liu J, Du L and Liu X:

Epigenetic modifications in breast cancer: From immune escape

mechanisms to therapeutic target discovery. Front Immunol.

16(1584087)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Watanabe Y, Maeda I, Oikawa R, Wu W,

Tsuchiya K, Miyoshi Y, Itoh F, Tsugawa KI and Ohta T: Aberrant DNA

methylation status of DNA repair genes in breast cancer treated

with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Genes Cells. 18:1120–1130.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chiou YS, Li S, Ho CT and Pan MH:

Prevention of breast cancer by natural phytochemicals: Focusing on

molecular targets and combinational strategy. Mol Nutr Food Res.

62(e1800392)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Abbasi BA, Iqbal J, Mahmood T, Khalil AT,

Ali B, Kanwal S, Shah SA and Ahmad R: Role of dietary

phytochemicals in modulation of miRNA expression: Natural swords

combating breast cancer. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 11:501–509.

2018.

|

|

12

|

Sohel M, Aktar S, Biswas P, Amin MA,

Hossain MA, Ahmed N, Mim MIH, Islam F and Mamun AA: Exploring the

anti-cancer potential of dietary phytochemicals for the patients

with breast cancer: A comprehensive review. Cancer Med.

12:14556–14583. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Thuy LHA, Thuan LD and Phuong TK: DNA

hypermethylation in breast cancer. In: Breast Cancer-From Biology

to Medicine. IntechOpen, 2017.

|

|

14

|

Flores-García LC, Rubio K, Ibarra-Sierra

E, Silva-Cázares MB, Palma-Flores C and López-Camarillo C:

Epigenetic and transcriptional reprogramming in 3D culture models

in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 17(3830)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Park M, Kim D, Ko S, Kim A, Mo K and Yoon

H: Breast cancer metastasis: Mechanisms and therapeutic

implications. Int J Mol Sci. 23(6806)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Smith ZD, Hetzel S and Meissner A: DNA

methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Genet.

26:7–30. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Karami Fath M, Azargoonjahromi A, Kiani A,

Jalalifar F, Osati P, Akbari Oryani M, Shakeri F, Nasirzadeh F,

Khalesi B, Nabi-Afjadi M, et al: The role of epigenetic

modifications in drug resistance and treatment of breast cancer.

Cell Mol Biol Lett. 27(52)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Jha AK, Nikbakht M, Jain V, Sehgal A,

Capalash N and Kaur J: Promoter hypermethylation of p73 and p53

genes in cervical cancer patients among north Indian population.

Mol Biol Rep. 39:9145–9157. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Agarwal N and Jha AK: DNA hypermethylation

of tumor suppressor genes among oral squamous cell carcinoma

patients: A prominent diagnostic biomarker. Mol Biol Rep.

52(44)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Fu J, Qin T, Li C, Zhu J, Ding Y, Zhou M,

Yang Q, Liu X, Zhou J and Chen F: Research progress of LINE-1 in

the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of gynecologic tumors.

Front Oncol. 13(1201568)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chen C, Wang Z, Ding Y, Wang L, Wang S,

Wang H and Qin Y: DNA methylation: From cancer biology to clinical

perspectives. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 27(326)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Besselink N, Keijer J, Vermeulen C,

Boymans S, de Ridder J, van Hoeck A, Cuppen E and Kuijk E: The

genome-wide mutational consequences of DNA hypomethylation. Sci

Rep. 13(6874)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Jung I, An J and Ko M: Epigenetic

regulators of DNA cytosine modification: Promising targets for

cancer therapy. Biomedicines. 11(654)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Heery R and Schaefer MH: DNA methylation

variation along the cancer epigenome and the identification of

novel epigenetic driver events. Nucleic Acids Res. 49:12692–12705.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Dunican DS, Mjoseng HK, Duthie L, Flyamer

IM, Bickmore WA and Meehan RR: Bivalent promoter hypermethylation

in cancer is linked to the H327me3/H3K4me3 ratio in embryonic stem

cells. BMC Biol. 18(25)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Vietri MT, D'elia G, Benincasa G, Ferraro

G, Caliendo G, Nicoletti GF and Napoli C: DNA methylation and

breast cancer: A way forward (Review). Int J Oncol.

59(98)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Duan X, Xing Z, Qiao L, Qin S, Zhao X,

Gong Y and Li X: The role of histone post-translational

modifications in cancer and cancer immunity: Functions, mechanisms

and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol.

15(1495221)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Gong P, Guo Z, Wang S, Gao S and Cao Q:

Histone phosphorylation in DNA damage response. Int J Mol Sci.

26(2405)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Fang Z, Wang X, Sun X, Hu W and Miao QR:

The role of histone protein acetylation in regulating endothelial

function. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9(672447)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Baweja L and Wereszczynski J: Mechanistic

basis for the opposing effects of H2A and H2B ubiquitination on

nucleosome stability and dynamics. bioRxiv [Preprint]:

2025.02.13.638112, 2025.

|

|

31

|

Ryu HY and Hochstrasser M: Histone

sumoylation and chromatin dynamics. Nucleic Acids Res.

49:6043–6052. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Millán-Zambrano G, Burton A, Bannister AJ

and Schneider R: Histone post-translational modifications-cause and

consequence of genome function. Nat Rev Genet. 23:563–580.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

George TP, Subramanian S and Supriya MH: A

brief review of noncoding RNA. Egypt J Med Hum Genet.

25(98)2024.

|

|

34

|

Amelio I, Bernassola F and Candi E:

Emerging roles of long non-coding RNAs in breast cancer biology and

management. Semin Cancer Biol. 72:36–45. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Keyvani-Ghamsari S, Khorsandi K, Rasul A

and Zaman MK: Current understanding of epigenetics mechanism as a

novel target in reducing cancer stem cells resistance. Clin

Epigenetics. 13(120)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Jouravleva K and Zamore PD: A guide to the

biogenesis and functions of endogenous small non-coding RNAs in

animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 26:347–370. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Xiong Q and Zhang Y: Small RNA

modifications: Regulatory molecules and potential applications. J

Hematol Oncol. 16(64)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Lu C, Wei D, Zhang Y, Wang P and Zhang W:

Long non-coding RNAs as potential diagnostic and prognostic

biomarkers in breast cancer: progress and prospects. Front Oncol.

11(710538)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hopkins JL, Lan L and Zou L: DNA repair

defects in cancer and therapeutic opportunities. Genes Dev.

36:278–293. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Kundu S, Sarkar S, Ghosh S and Chowdhury

AA: DNA methylation as an oncogenic driver in breast cancer:

Therapeutic targeting via epigenetic reprogramming of DNA

methyltransferases. Biochem Pharmacol. 242(117313)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Moelans CB, Verschuur-Maes AH and Van

Diest PJ: Frequent promoter hypermethylation of BRCA2, CDH13, MSH6,

PAX5, PAX6 and WT1 in ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast

cancer. J Pathol. 225:222–231. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Aravind Kumar M, Naushad SM, Narasimgu N,

Nagaraju Naik S, Kadali S, Shanker U and Lakshmi Narasu M: Whole

exome sequencing of breast cancer (TNBC) cases from India:

Association of MSH6 and BRIP1 variants with TNBC risk and oxidative

DNA damage. Mol Biol Rep. 45:1413–1419. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zou R, Zhong X, Wang C, Sun H, Wang S, Lin

L, Sun S, Tong C, Luo H, Gao P, et al: MDC1 enhances estrogen

receptor-mediated transactivation and contributes to breast cancer

suppression. Int J Biol Sci. 11:992–1005. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Torres Esteban M: Structural and

Functional Characterization of Two Phosphorylation Site Clusters in

the DNA Damage Response Adaptor Protein MDC1. Doctoral

Dissertation, University of Zurich, 2024.

|

|

45

|

Kelliher J, Ghosal G and Leung JWC: New

answers to the old RIDDLE: RNF168 and the DNA damage response

pathway. FEBS J. 289:2467–2480. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Xie T, Qin H, Yuan Z, Zhang Y, Li X and

Zheng L: Emerging roles of RNF168 in tumor progression. Molecules.

28(1417)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Pettitt S, Proszek P, Torga G, Gulati A,

Llop-Guevara A, Jank P, Felder B, Rodriguez A, Cooke S,

Garcia-Murillas I, et al: 435 (PB423): Persistence of BRCA1 and

RAD51C methylation after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in high risk

TNBC. Eur J Cancer. 211 (Suppl 1)(S114944)2024.

|

|

48

|

Tabano S, Azzollini J, Pesenti C, Lovati

S, Costanza J, Fontana L, Peissel B, Miozzo M and Manoukian S:

Analysis of BRCA1 and RAD51C promoter methylation in Italian

families at high-risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Cancers

(Basel). 12(910)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Malik SS, Zia A, Mubarik S, Masood N,

Rashid S, Sherrard A, Khan MB and Khadim MT: Correlation of MLH1

polymorphisms, survival statistics, in silico assessment and gene

downregulation with clinical outcomes among breast cancer cases.

Mol Biol Rep. 47:683–692. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Dasgupta H, Islam S, Alam N, Roy A,

Roychoudhury S and Panda CK: Hypomethylation of mismatch repair

genes MLH1 and MSH2 is associated with chemotolerance of breast

carcinoma: Clinical significance. J Surg Oncol. 119:88–100.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Heng J, Zhang F, Guo X, Tang L, Peng L,

Luo X, Xu X, Wang S, Dai L and Wang J: Integrated analysis of

promoter methylation and expression of telomere related genes in

breast cancer. Oncotarget. 8(25442)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Abad E, Civit L, Potesil D, Zdrahal Z and

Lyakhovich A: Enhanced DNA damage response through RAD50 in triple

negative breast cancer resistant and cancer stem-like cells

contributes to chemoresistance. FEBS J. 288:2184–2202.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Borde V: The multiple roles of the Mre11

complex for meiotic recombination. Chromosome Res. 15:551–563.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Lu R, Zhang H, Jiang YN, Wang ZQ, Sun L

and Zhou ZW: Post-translational modification of MRE11: Its

implication in DDR and diseases. Genes (Basel).

12(1158)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Block-Schmidt AS, Dukowic-Schulze S,

Wanieck K, Reidt W and Puchta H: BRCC36A is epistatic to BRCA1 in

DNA crosslink repair and homologous recombination in Arabidopsis

thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:146–154. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Rabl J, Bunker RD, Schenk AD, Cavadini S,

Gill ME, Abdulrahman W, Andrés-Pons A, Luijsterburg MS, Ibrahim

AFM, Branigan E, et al: Structural basis of BRCC36 function in DNA

repair and immune regulation. Mol Cell. 75:483–497.e9.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Rosen EM, Fan S, Pestell RG and Goldberg

ID: BRCA1 gene in breast cancer. J Cell Physiol. 196:19–41.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Tarsounas M and Sung P: The

antitumorigenic roles of BRCA1-BARD1 in DNA repair and replication.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:284–299. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Stefansson OA and Esteller M: Epigenetic

modifications in breast cancer and their role in personalized

medicine. Am J Pathol. 183:1052–1063. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Fishchuk L, Rossokha Z, Lobanova O,

Cheshuk V, Vereshchako R, Vershyhora V, Medvedieva N, Dubitskaa O

and Gorovenko N: Hypermethylation of the BRCA2 gene promoter and

its co-hypermethylation with the BRCA1 gene promoter in patients

with breast cancer. Cancer Biomark. 40:275–283. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Pauty J, Rodrigue A, Couturier A, Buisson

R and Masson JY: Exploring the roles of PALB2 at the crossroads of

DNA repair and cancer. Biochem J. 460:331–342. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Potapova A, Hoffman AM, Godwin AK,

Al-Saleem T and Cairns P: Promoter hypermethylation of the PALB2

susceptibility gene in inherited and sporadic breast and ovarian

cancer. Cancer Res. 68:998–1002. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Khanna KK: Cancer risk and the ATM gene: A

continuing debate. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92:795–802. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

He C, Kawaguchi K and Toi M: DNA damage

repair functions and targeted treatment in breast cancer. Breast

Cancer. 27:355–362. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Vo QN, Kim WJ, Cvitanovic L, Boudreau DA,

Ginzinger DG and Brown KD: Erratum: The ATM gene is a target for

epigenetic silencing in locally advanced breast cancer. Oncogene.

24(1964)2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Zhou T, Yi F, Wang Z, Guo Q, Liu J, Bai N,

Li X, Dong X, Ren L, Cao L and Song X: The functions of DNA damage

factor RNF8 in the pathogenesis and progression of cancer. Int J

Biol Sci. 15:909–918. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Lee HJ, Li CF, Ruan D, Powers S, Thompson

PA, Frohman MA and Chan CH: The DNA damage transducer RNF8

facilitates cancer chemoresistance and progression through twist

activation. Mol Cell. 63:1021–1033. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Hacking S, Chou C, Baykara Y, Wang Y, Uzun

A and Gamsiz Uzun ED: MMR deficiency defines distinct molecular

subtype of breast cancer with histone proteomic networks. Int J Mol

Sci. 24(5327)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Patel PS, Abraham KJ, Guturi KK, Halaby

MJ, Khan Z, Palomero L, Ho B, Duan S, St-Germain J, Algouneh A, et

al: RNF168 regulates R-loop resolution and genomic stability in

BRCA1/2-deficient tumors. J Clin Invest.

131(e140105)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Liu H and Weng J: A pan-cancer

bioinformatic analysis of RAD51 regarding the values for diagnosis,

prognosis, and therapeutic prediction. Front Oncol.

12(858756)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Yan Y, Wang Y, Tang J, Liu X, Wang J, Song

G and Li H: Comprehensive analysis of oncogenic somatic alterations

of mismatch repair gene in breast cancer patients. Bioengineering

(Basel). 12(426)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Karamat U and Ejaz S: Overexpression of

RAD50 is the marker of poor prognosis and drug resistance in breast

cancer patients. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 21:163–176.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Alblihy A, Shoqafi A, Toss MS, Algethami

M, Harris AE, Jeyapalan JN, Abdel-Fatah T, Servante J, Chan SYT,

Green A, et al: Untangling the clinicopathological significance of

MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex in sporadic breast cancers. NPJ Breast

Cancer. 7(143)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Mohamed RI, Bargal SA, Mekawy AS,

El-Shiekh I, Tuncbag N, Ahmed AS, Badr E and Elserafy M: The

overexpression of DNA repair genes in invasive ductal and lobular

breast carcinomas: Insights on individual variations and precision

medicine. PLoS One. 16(e0247837)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Glodzik D, Bosch A, Hartman J, Aine M,

Vallon-Christersson J, Reuterswärd C, Karlsson A, Mitra S, Niméus

E, Holm K, et al: Comprehensive molecular comparison of BRCA1

hypermethylated and BRCA1 mutated triple negative breast cancers.

Nat Commun. 11(3747)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Pang JMB, Deb S, Takano EA, Byrne DJ, Jene

N, Boulghourjian A, Holliday A, Millar E, Lee CS, O'Toole SA, et

al: Methylation profiling of ductal carcinoma in situ and its

relationship to histopathological features. Breast Cancer Res.

16(423)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Scott CM, Joo JE, O'Callaghan N, Buchanan

DD, Clendenning M, Giles GG, Hopper JL, Wong EM and Southey MC:

Methylation of breast cancer predisposition genes in early-onset

breast cancer: Australian breast cancer family registry. PLoS One.

11(e0165436)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Knijnenburg TA, Wang L, Zimmermann MT,

Chambwe N, Gao GF, Cherniack AD, Fan H, Shen H, Way GP, Greene CS,

et al: Genomic and molecular landscape of DNA damage repair

deficiency across the cancer genome atlas. Cell Rep. 23:239–254.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Liu C, Kuang J, Wang Y, Duan T, Min L, Lu

C, Zhang T, Chen R, Wu Y and Zhu L: A functional reference map of

the RNF8 interactome in cancer. Biol Direct. 17(17)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Jayakumari S: Phytochemicals and

pharmaceutical: Overview: Recent progress and future applications.

In: Advances in Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. Springer Singapore,

pp163-173, 2020.

|

|

81

|

Kumar A, P N, Kumar M, Jose A, Tomer V, Oz

E, Proestos C, Zeng M, Elobeid T, K S and Oz F: Major

phytochemicals: Recent advances in health benefits and extraction

method. Molecules. 28(887)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Bhattacharya T, Dutta S, Akter R, Rahman

MH, Karthika C, Nagaswarupa HP, Murthy HCA, Fratila O, Brata R and

Bungau S: Role of phytonutrients in nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics

perspective in curing breast cancer. Biomolecules.

11(1176)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Pop S, Enciu AM, Tarcomnicu I, Gille E and

Tanase C: Phytochemicals in cancer prevention: Modulating

epigenetic alterations of DNA methylation. Phytochem Rev.

18:1005–1024. 2019.

|

|

84

|

Hsieh HH, Kuo MZ, Chen IA, Lin CJ, Hsu V,

Huangfu WC and Wu TY: Epigenetic modifications as novel therapeutic

strategies of Cancer chemoprevention by phytochemicals. Pharm Res.

42:69–78. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Guney Eskiler G, Sahin E, Deveci Ozkan A,

Cilingir Kaya OT and Kaleli S: Curcumin induces DNA damage by

mediating homologous recombination mechanism in triple negative

breast cancer. Nutr Cancer. 72:1057–1066. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Choi YE and Park E: Curcumin enhances

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor sensitivity to chemotherapy

in breast cancer cells. J Nutr Biochem. 26:1442–1447.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Komar ZM, Ladan MM, Verkaik NS, Dahmani A,

Montaudon E, Marangoni E, Kanaar R, Nonnekens J, Houtsmuller AB,

Jager A and van Gent DC: Curcumin induces homologous recombination

deficiency by BRCA2 degradation in breast cancer and normal cells.

Cancers (Basel). 17(2109)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Xie Q, Bai Q, Zou LY, Zhang QY, Zhou Y,

Chang H, Yi L, Zhu JD and Mi MT: Genistein inhibits DNA methylation

and increases expression of tumor suppressor genes in human breast

cancer cells. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 53:422–431. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Donovan MG, Selmin OI, Doetschman TC and

Romagnolo DF: Epigenetic activation of BRCA1 by genistein in vivo

and triple negative breast cancer cells linked to antagonism toward

aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nutrients. 11(2559)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Sharma M and Tollefsbol TO: Combinatorial

epigenetic mechanisms of sulforaphane, genistein and sodium

butyrate in breast cancer inhibition. Exp Cell Res.

416(113160)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Karimian A, Majidinia M, Moliani A, Alemi

F, Asemi Z, Yousefi B and Naghibi AF: The modulatory effects of two

bioflavonoids, quercetin and thymoquinone on the expression levels

of DNA damage and repair genes in human breast, lung and prostate

cancer cell lines. Pathol Res Pract. 240(154143)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Gao X, Wang J, Li M, Wang J, Lv J, Zhang

L, Sun C, Ji J, Yang W, Zhao Z and Mao W: Berberine attenuates

XRCC1-mediated base excision repair and sensitizes breast cancer

cells to the chemotherapeutic drugs. J Cell Mol Med. 23:6797–6804.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Fang MZ, Wang Y, Ai N, Hou Z, Sun Y, Lu H,

Welsh W and Yang CS: Tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate

inhibits DNA methyltransferase and reactivates methylation-silenced

genes in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 63:7563–7570.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Mirza S, Sharma G, Parshad R, Gupta SD,

Pandya P and Ralhan R: Expression of DNA methyltransferases in

breast cancer patients and to analyze the effect of natural

compounds on DNA methyltransferases and associated proteins. J

Breast Cancer. 16:23–31. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Zhang X, Timmermann B, Samadi AK and Cohen

MS: Withaferin a induces proteasome-dependent degradation of breast

cancer susceptibility gene 1 and heat shock factor 1 proteins in

breast cancer cells. ISRN Biochem. 2012(707586)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Hahm ER, Lee J, Abella T and Singh SV:

Withaferin A inhibits expression of ataxia telangiectasia and

Rad3-related kinase and enhances sensitivity of human breast cancer

cells to cisplatin. Mol Carcinog. 58:2139–2148. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Yu Y, Katiyar SP, Sundar D, Kaul Z, Miyako

E, Zhang Z, Kaul SC, Reddel RR and Wadhwa R: Withaferin-A kills

cancer cells with and without telomerase: Chemical, computational

and experimental evidences. Cell Death Dis. 8(e2755)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Batra RN, Lifshitz A, Vidakovic AT, Chin

SF, Sati-Batra A, Sammut SJ, Provenzano E, Ali HR, Dariush A, Bruna

A, et al: DNA methylation landscapes of 1538 breast cancers reveal

a replication-linked clock, epigenomic instability and

cis-regulation. Nat Commun. 12(5406)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Yang J, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Yu X and

Shi S: Epigenetic regulation in the tumor microenvironment:

Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 8(210)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Sherif ZA, Ogunwobi OO and Ressom HW:

Mechanisms and technologies in cancer epigenetics. Front Oncol.

14(1513654)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

McCarthy-Leo C, Darwiche F and Tainsky MA:

DNA repair mechanisms, protein interactions and therapeutic

targeting of the MRN complex. Cancers (Basel).

14(5278)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Gupta VK, Singh R and Sharma B:

Phytochemicals mediated signalling pathways and their implications

in cancer chemotherapy: Challenges and opportunities in

phytochemicals based drug development: A review. Biochem Comp.

5:1–5. 2017.

|

|

103

|

Alaouna M, Penny C, Hull R, Molefi T,

Chauke-Malinga N, Khanyile R, Makgoka M, Bida M and Dlamini Z:

Overcoming the challenges of phytochemicals in triple negative

breast cancer therapy: The path forward. Plants (Basel).

12(2350)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Singh VK, Arora D, Ansari MI and Sharma

PK: Phytochemicals based chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic

strategies and modern technologies to overcome limitations for

better clinical applications. Phytother Res. 33:3064–3089.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Koklesova L, Jakubikova J, Cholujova D,

Samec M, Mazurakova A, Šudomová M, Pec M, Hassan STS, Biringer K,

Büsselberg D, et al: Phytochemical-based nanodrugs going beyond the

state-of-the-art in cancer management-targeting cancer stem cells

in the framework of predictive, preventive, personalized medicine.

Front Pharmacol. 14(1121950)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|