1. Introduction

Curcumin is the principal constituent of turmeric

i.e., the ground rhizomes of Curcuma longa, which contains

two other curcuminoids: desmethoxycurcumin and

bis-desmethoxycurcumin (1).

Turmeric is widely used as a spice mostly in Asian countries.

However, it is also used to treat acne, psoriasis, dermatitis and

rash. It should be stressed that traditionally, turmeric was

suspended in whole milk or buttermilk that dissolved it in fat

fractions and/or stabilized curcumin (2). Over the past few decades,

preclinical and clinical studies have revealed that curcumin is

active against variety of diseases, such as cancer and pulmonary

diseases, as well as neurological, liver, metabolic, autoimmune and

cardiovascular diseases, and numerous other chronic ailments

(3–6). Over 116 clinical studies on curcumin

in humans were registered with the US National Institutes of Health

in 2015 encomapssing a number of conditions, such as cancer,

cognitive disorders, gastrointestinal diseases and psychiatric

conditions. In humans, the administration of curcumin at up to 12 g

per day has not been found to exert any toxic effects (7–10).

One of the puzzling questions is how curcumin can be

so effective in the treatment of diseases, since it has a very low

water solubility and bioavailability. For example, the oral dose of

8 g/day in humans translates to low nanogram levels of circulating

curcumin in plasma (only 22–41 ng/ml) (11,12). Moreover, curcumin is not stable

under various conditions, such as aqueous phosphate buffer or

serum-free medium at 37°C, degrading to the bioactive compounds,

including ferulic acid, feruloylmethane and vanillin, which may be

responsible for its biological activities rather than curcumin

itself (12,13).

In view of the very low bioavailability of curcumin

as observed in clinical studies, the role of the degradation or

condensation products should be taken into consideration when

evaluating the activity of curcumin in various diseases.

2. Physico-chemical properties of

curcumin

Curcumin (IUPAC name:

(1E,6E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione)

is, practically insoluble in water at a neutral and lower pH, but

is soluble in acetone, dichloromethane, methanol, ethanol, alkali

and oils. The water solubility of curcumin may be increased by its

incorporation into various surfactants, such as sodium dodecyl

sulfate, polysaccharides, polyethylene glycol and cyclodextrins, as

well as others (13,14). In addition, in aqueous solutions

and at an alkaline pH, the acidic phenol group in curcumin

dissociates its hydrogen, forming the phenolate ion(s) that render

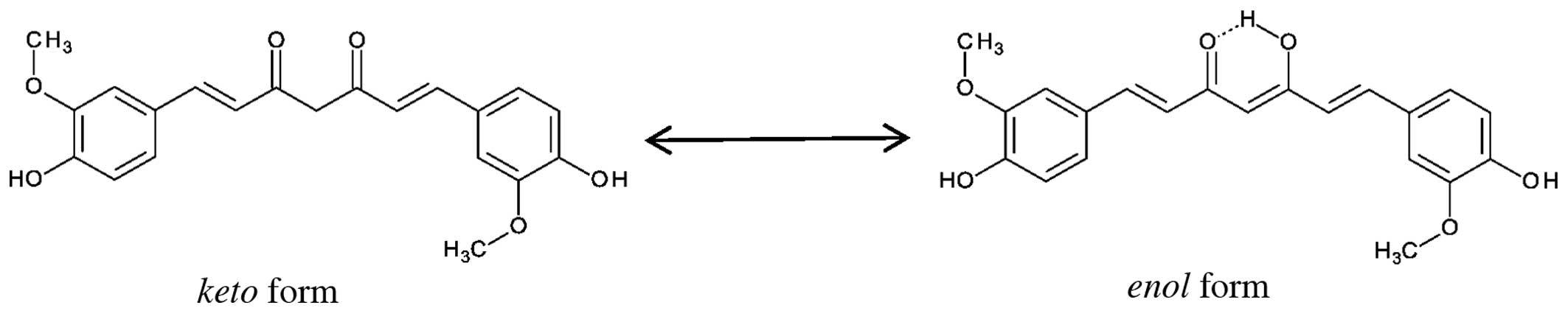

the solubility of curcumin in water somewhat possible (15–18). Curcumin is a natural polyphenol

that is responsible for the yellow color of turmeric and exhibits

keto-enol tautomerism (Fig.

1). The enol form is more energetically stable in the

solid phase and, depending on the solvent, up to 95% can be in the

enol form (1). Three

reactive functional groups, namely diketone moiety and two phenolic

groups determine the activity of curcumin. The biologically

important chemical reactions of curcumin are the following: the

hydrogen donation leading to oxidation, reversible and irreversible

nucleophilic addition (Michael reaction), hydrolysis, degradation

and enzymatic reactions (19).

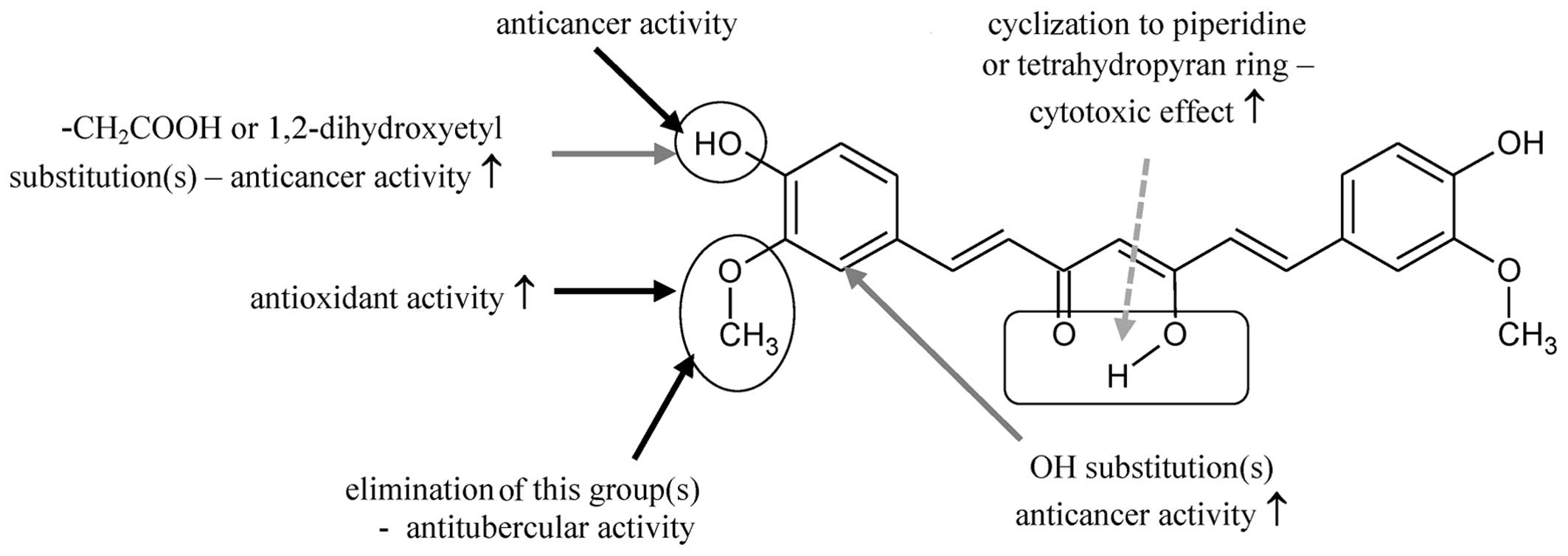

In a previous review article, Agrawal and Mishra

analyzed studies (years 1815–2009) on curcumin and 728 curcumin

analogs (20). This very large

group of compounds was tested for pharmacological properties and

mostly on anticancer activity on different cell lines. Some analogs

have been shown to exhibit antioxidant, anti-mutagenic and anti-HIV

activities (21), as well as

anti-angiogenic anti-malaria and anti-tuberculosis activities

(7) or anti-inflammatory

activities [cyclooxygenases (COX) inhibitors]. Based on a

literature search, the authors concluded the following (Fig. 2): the anticancer properties of

curcuminoids depend on the presence of OH groups in the phenolic

ring (entries 4 and 4′). These groups are an electron donor to free

radicals. The methoxy group at position 3 and 3′ increases the

antioxidant properties of curcuminoids; substitution in the 2 and

2′ positions increases all activities than the unsubstituted

analogs; cyclization in the central part of the compound and the

introduction of heteroatoms (oxygen and nitrogen) leads to the

formation of compounds with enhanced antitumor and anti-angiogenic

activities; attaching solubilizing groups to the OH group in

position 4 and 4′ is responsible for the cytotoxicity of

curcuminoids; the elimination of one of the methoxy group reveals

the effect of tuberculosis (7);

conversion of methoxy groups to hydroxyl increases the anti-HIV

activity (21).

3. Alkaline degradation and autoxidation of

curcumin

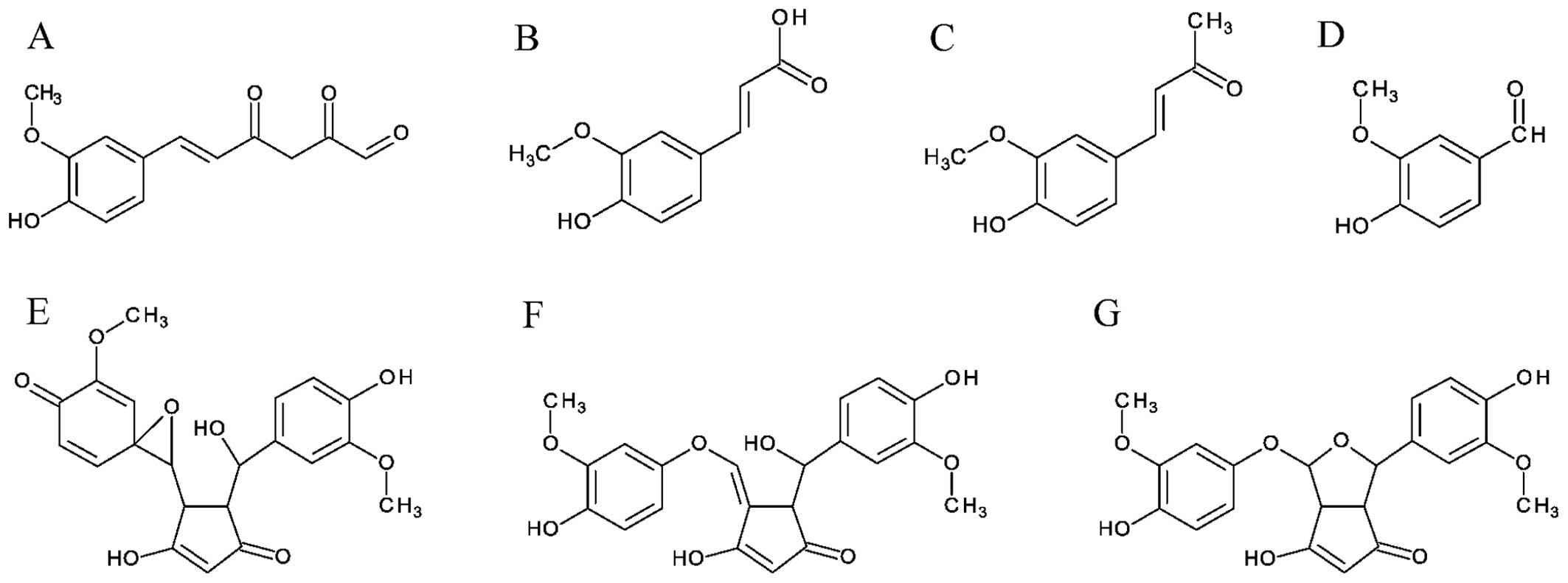

Wang et al (13) incubated curcumin in 0.1 M

phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 at 37°C, and found that 90% was degraded

in 30 min. Trans-6-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2,4-dioxo-5-hexenal,

vanillin, ferulic acid and feruloyl methane (Fig. 3A–D) were identified as degradation

products (13). This is a

plausible explanation of the biological activity of curcumin, since

the degradation products have better aqueous solubility as

reflected by their respective logP values: 1.42 for ferulic acid

and 1.09 for vanillin, lower than the keto and enol

form of curcumin, which are respectively 2.56 and 2.17 (12). Moreover, it has been reported that

ferulic acid inhibits COX-1 and -2 and suppresses the activation of

nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which are known to be important targets

in the prevention of cancer development (12,22,23). Vanillin as well can inhibit COX-2

gene expression and NF-κB activation (12,24).

Shen and Ji (12),

in a comprehensive review of curcumin degradation, described the

curcumin-mediated inhibition of xanthine oxidase that is involved

in the pathogenesis of many diseases. The authors described

molecular modeling, demonstrating that all degradation products can

enter into the binding pocket of an enzyme. Surprisingly, curcumin

itself failed to efficiently fit within the binding pocket of

xanthine oxidase and only entered the binding pocket with low

binding affinity (12). This is

consistent with the experimental findings that the degradation

products (ferulic acid, vanillin, ferulic acid and feruloyl

methane), rather than curcumin itself can inhibit xanthine oxidase

(12,25,26).

In a previous study, Gordon and Schneider

demonstrated that the cleavage of the heptadienedione chain,

resulting in vanillin, ferulic acid and feruloylmethane as

products, was not the prevailing degradation reaction (27). Rather, they proposed that the

degradation of curcumin is a spontaneous autoxidation, free

radical-driven incorporation of oxygen and that the major product

of this process is a bicyclopentadione (15,27). It has been reported that different

product profiles of curcumin autoxidation reactions are dependent

on time. In reactions between 20–45 min, the chromatograms exhibit

peaks, indicating spiroepoxide and vinylether as major products

(Fig. 3E–G), and dihydroxy,

ketohydroxy and hemiketal cyclopentadiones as minor products.

Degradation between 30 min and 4 h also produces the

bicyclopentadiones as major products and, several unidentified

chemicals. When autoxidation is longer than 4 h, bicyclopentadione

is detected as well (28,29).

Naturally occurring polyphenols have been shown to

act with topoisomerase II, increasing the levels of topoisomerase

II-mediated DNA cleavage. Topoisomerase poisons are used in

anticancer and antibacterial therapies. Thus, Ketron et al

(30) investigated whether

curcumin, its structurally related degradation products (vanillin,

ferulic acid and feruloylmethane) and its oxidative metabolites

exert any effects on the DNA cleavage of human topoisomerase IIα

and IIβ. Curcumin, bicyclopentadione, vanillin, ferulic acid and

feruloylmethane were shown to have no effect on DNA cleavage.

However, intermediates of the curcumin oxidation pathway increased

the level of DNA cleavage by both enzymes ~4–5-fold. Moreover,

under conditions that promote oxidation, curcumin enhanced

topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage even further (30).

Gordon et al (28) also demonstrated that the product

of curcumin oxidation, a stable spiroepoxide, was able to poison

recombinant human topoisomerase IIα and that this process was

significantly increased in the presence of potassium ferricyanide,

indicating that oxidative conversion was needed to achieve full DNA

cleavage activity. They concluded that oxidative metabolites may be

responsible for the biological effects of curcumin (28).

4. Photodegradation of curcumin

It is common knowledge that turmeric stains can be

removed by exposure to sunlight. This is due to the fact that

curcumin absorbs strongly in the visible wavelength range, making

it predisposed to degradation and modification in daylight and

artificial lighting. The photodegradation of curcumin takes place

in solid state, as well as in different organic solvents (14,18,31–34). However, the composition,

degradation kinetics and the relative abundance of the degradation

products differ, depending on the physical state of the compound

and the conditions.

Previously, the photochemical degradation of solid

state curcumin exposed to sunlight for 120 h yielded vanillin

(34%), ferulic aldehyde (0.5%), ferulic acid (0.5%), vanillic acid

(0.5%) and three unidentified compounds. The photodegradation of

dissolved curcumin depends on the solvent and wavelength. When

curcumin was dissolved in isopropanol and irradiated for 4 h at

400–510 nm, then similar products as in the case of

light-irradiated crystalline curcumin were observed, such us

vanillin, vanillic acid and ferulic acid, in addition to aldehyde

4-vinylguaiacol (34).

Exposure to visible light inflicts more degradation

than UV light; the irradiation of curcumin in 254-nm in methanol

has been shown to produce three unspecified degradation products,

whereas irradiation with daylight produces five unspecified

degradation chemicals products (31). The exposure of curcumin to visible

light is solvent-dependent. Irradiation with light (400–750-nm) for

4 h was shown to be associated with cyclization at one of the

o-methoxyphenyl groups, producing

7-hydroxy-1-[(2E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-enoyl]-6-methoxy-naphthalen-2(1H)-one

in isopropanol, methanol and chloroform, but not in acetonitrile

and ethyl acetate (32,34). Galer and Šket irradiated

acetonitrile solution of curcumin by light (350 nm) and found that

90% of all formed products included 3,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde,

3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid and Z and E isomers of

3-(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propenoic acid (35).

It has also been reported that the photodegradation

of curcumin involves the formation of the excited states and

generation of singlet oxygen that is responsible for the

photobiological and photodynamic activity of curcumin (19,33). Thus, it was postulated that the

degradation of curcumin following photoexcitation must proceed

though the triplet excited state of curcumin (19). Curcumin is photoactivated by blue

light (420–480 nm) that has limited tissue penetration. That

property makes curcumin an ideal surface antibacterial agent for

oral or skin disinfection, particularly for antibiotic-resistant

bacterial strains as it does not affect healthy tissue (36–38).

An interesting observation was previously made when

studying the interaction of curcumin with lipoxygenase (LOX) by a

single-crystal X-ray analysis, showing the complex Enz:Fe-O-O-R

with the curcumin degradation product instead, identified as

4-hydroperoxy-2-methoxyphenol bound to the enzyme's iron cofactor.

Irradiation by X-ray is known to produce free radicals, but

curcumin itself is stable under such conditions. LOX is a very good

biocatalyst stimulating many reactions, neither of which would lead

to the observed product. Thus, it was obvious that the X-ray

radiation, LOX and curcumin properties together were responsible

for the curcumin transformation to this peroxide, which converts it

into 2-methoxycyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione (39). While the enzyme in that experiment

was of plant origin, humans do have six LOXs, four of which (5-,

12S-, 12R-LOX and eLOX-3, [for comparison see (40)] have a highly similar structure of

the enzymatic active site. X-rays radiation used for curative

purposes in humans often causes severe side-effects, including

inflammatory responses caused by various eicosanoids produced by

oxygenases: COX and LOX and cytochrome P450 (CYP450). It may be

worth exploring whether and how curcumin may be utilized during

radiation therapy to improve the treatment outcomes and the comfort

of patients.

5. Curcumin complexes with metals

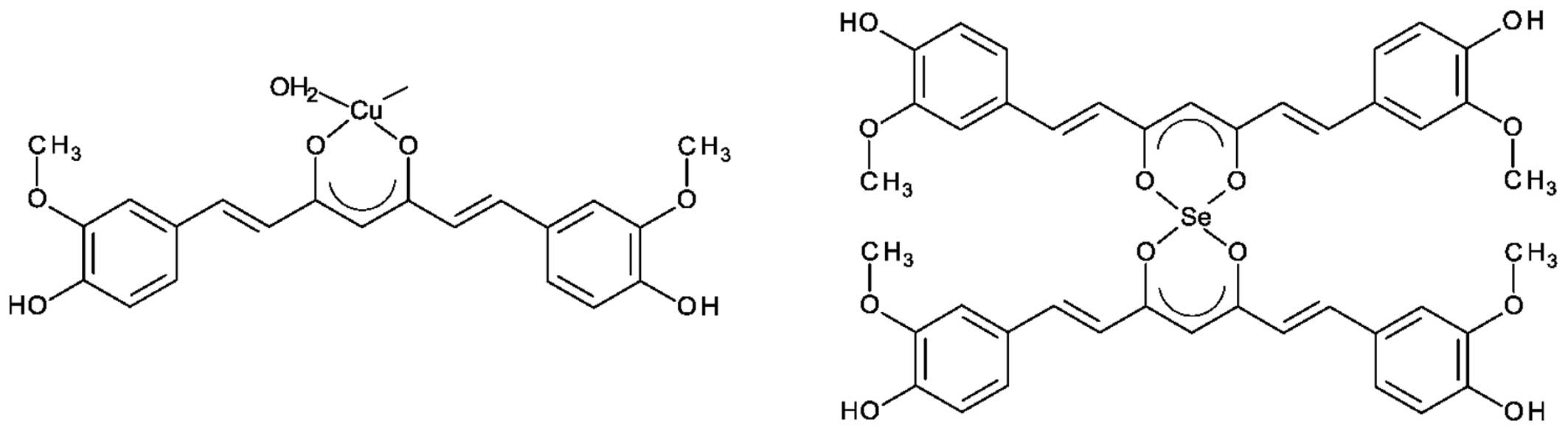

Curcumin can form complexes with transition metals

to protect against degradation in the treatment of Alzheimer's

disease (41,42). Several curcumin complexes with

metals (Cu, Mn, V, Ga and In) have been synthesized and evaluated

for their biological activity (43–49). However, all these metallocomplexes

have been synthetized under high temperature conditions, reflux at

100°C in the presence of different organic solvents for 3 h. Zebib

et al (50) synthesized

curcumin complexes with divalent ions of Zn2+,

Cu2+, Mg2+ and Se2+, in

glycerol/water solution and room temperature (50) (Fig.

4). They found that all complexes were stable in water at pH

6.5 up to 30 h at 37°C. All complexes rapidly decomposed by

demetallization at acidic pH 2 and greatly decreased at higher pH

10. At pH 7.0, in phosphate buffer, curcumin was degraded after 1

h, while <5% of complexes were degraded. The authors estimated

that the stability of curcumin metal complexes at pH 7 was ~20-fold

greater than that of curcumin alone (50).

John et al (49) synthetized four synthetic

curcuminoids and their Cu2+ metallocomplexes. Using L929

mouse fibrosarcoma cells, they found that the concentration

required for the 50% inhibition of cell growth was ~10 µg/ml

for curcuminoids, but only 1 µg/ml for their copper

counterparts. Moreover, they observed a significant reduction

(p<0.001) in tumor volume in mice treated with copper chelates

of curcuminoids (49). Mei et

al (51) investigated the

anti-ulcerogenic effects of a Zn-curcumin chelate in mice.

Treatment with Zn-curcumin reduced gastric lesions in a

dose-dependent manner (12, 24 and 48 mg/kg) in comparison with the

control group (51). In a

different study from the same group, the effects of Zn-curcumin on

hemorheological alterations, oxidative stress and liver injury in a

rat model of acute alcoholism were investigated. They found that

the oral dose of Zn-chelated curcumin prevented the alcohol-induced

increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in serum and the reduction

in glutathione levels and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity.

Furthermore the Zn-curcumin complex inhibited ethanol-induced liver

injury. In addition, this curcumin derivative reduced the

alcohol-induced elevation of blood viscosity, plasma viscosity,

erythrocyte aggregation index and hematocrit. In all of these

experiments Zn-curcumin was found to be more effective than

curcumin (52).

In another study, Refat (53) synthesized curcumin complexes with

Cr(III), Mn(II), Fe(III), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) and

tested the antibacterial and antifungal activity. Only the cobalt

[Co(II)]-curcumin complex exhibited antibacterial activity against

three bacterial strains (Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas

aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus) (53).

6. Interaction of enzymes with curcumin

Curcumin interacts with very large number of

proteins, such us albumin (54),

Ca2+-ATPase of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (55,56), Ca2+-dependent protein

kinase (CDPK) (57), COX-2

(58,59), LOX (39,60), LOX-5 (61), pp60c-src tyrosine kinase (62,63), PKC (63), xanthine oxidase (64,65) and many others (66). Dr Duke's Phytochemical and

Ethnobotanical Database (https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/search)

provides a long list of curcumin anti- and pro-health properties.

It is known as an inhibitor of the oxygenases 5- and 12-LOX, COX-2

and CYP450, but an inducer of lipase which is up in the arachidonic

acid pathway. It can inhibit protein kinase C (PKC), protein

tyrosine kinase (PTK), IKB-kinase and IKK involved in NF-κB

signaling pathway, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), topoisomerase I and

II, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), sortase A and

ornithine decarboxylase. It promotes maltase and sucroses, and

glutathione synthetase activity, while it suppresses amyloid β

activity. This list, probably far from complete, shows that

curcumin has a very broad range of activities and that its impact

would depend on dose and environment.

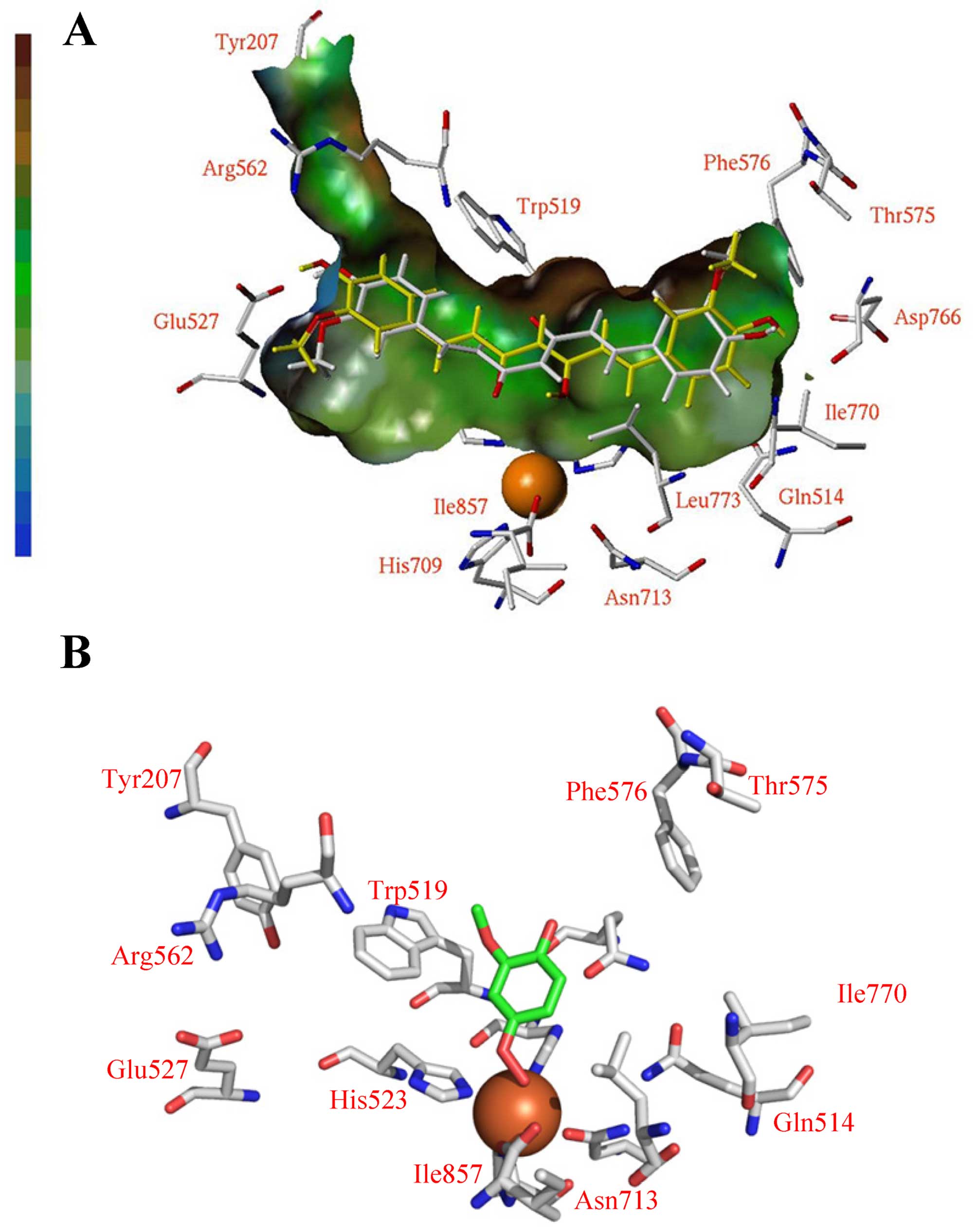

Computational molecular modeling methods have shown

that curcumin can bind into the central active pocket of soybean

LOX-3 lipoxygnase (39). However,

the solved X-ray structure of LOX shows the photodegradation

product of curcumin (Fig. 5).

That was based on the size, volume and position of the unoccupied

(Fo-Fc) difference map (39,60).

7. Changes in the body

Interestingly, curcumin has is metabolized

differently in the mammalian body depending on the type of

administration (oral, intravenous or intraperitoneal). Curcumin

administered orally undergoes glucuronidation and sulfation to the

glucuronide of hexahydrocurcumin (67). However, when administered

intravenously or intraperitoneally, it undergoes a reduction that

leads to the formation of tetrahydrocurcumin and hexahydrocurcumin,

the two major metabolites of curcumin in body fluids, organs and

cells (68), and two minor

metabolites: octahydrocurcumin and dihydrocurcumin. Curcumin is

poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract after oral intake,

with extremely low concentrations being detected only in bile,

urine (67,69) and blood plasma (70). Furthermore, in available tissue

samples obtained during surgery from patients administered high

doses of curcumin, either no curcumin, or very low concentrations

of curcumin conjugates were detected (71). Despite the lower bioavailability,

in clinical investigations, curcumin has been shown to have

therapeutic potential in various human diseases. The main activity

of curcumin seems to be connected with its modulatory activity of

cell signaling pathways and transcription factors, such as NF-κB,

activator protein 1 (AP-1) and mitogen-activated protein kinase

(MAPK) (72), and its suppressive

effects on the expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as

interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, TNF-α, matrix metalloproteinase

(MMP)-2 and MMP-9 (73).

Periodontitis, as an imbalance between biofilm and

immune host reaction, is an opportunistic and chronic infection in

which the above-mentioned cell signaling pathways regulating the

expression of inflammatory mediators have become promising

therapeutic targets (74). The

oral cavity can be easily used to observe the reactions of tissue

to curcumin in vitro and in vivo. In many animal

studies, the antioxidant (75)

and anti-inflammatory (76), as

well as the angiogenic and wound-healing effects of curcumin, by

increasing the number of fibroblasts and promoting collagen

synthesis (77), or by modulating

urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) expression (78), have been demonstrated.

Interestingly, curcumin does not prevent alveolar bone resorption

in vivo in rats (76), but

inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis in vitro (79). Guimarães et al also

observed the lack of inhibition of bone resorption in an

experimental model of lipopolysacharide (LPS)-induced periodontal

disease (76), which is

surprising, keeping in mind that curcumin was shown to

significantly inhibit Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS-induced

TNF-α and IL-1β production (80).

Curcumin has also exhibited exhibited bactericidal activity against

Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia,

Fusobacterium nucleatum and capnocytophaga at a

minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 1 mg/ml by the local

application into periodontal pockets in humans (81). The results of the

benzoyl-DL-arginine-naphthylamide (BANA) test, which verifyied the

presence of Tannerella forsythia, Treponema

denticola, Porphyromonas gingivalis and

capnocytophaga species, was similar for 1% curcumin solution

and 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate in subgingival irrigation. The

only difference was the earlier re-colonization by periopathogens

places treated with curcumin (82). Curcumin exhibits a local activity

in the chemopreventive therapy of premalignant lesions for oral

cancer. In an in vitro model consisting of primary cultures

of normal epithelial cells, cell lines derived from dysplastic

leukoplakia and squamous cell carcinoma cells, curcumin was equally

effective for all cell types tested and blocked the cells in the

S/G2M phase of the cell cycle (83). The local effectiveness of curcumin

was higher in combination with(−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)

(83). This suggests some

limitations of curcumin even in local treatment.

Numerous approaches have been undertaken to improve

the poor solubility, rapid metabolic disposition and the lack of

systemic bioavailability of curcumin. One of the possibilities is

the use of curcumin metabolites or chemically modified curcumin.

Unlike curcumin, tetrahydrocurcumin is stable in phosphate buffer

and in saline at various pH values and is easy absorbed through the

gastrointestinal tract (84). An

in vitro investigation revealed that treatment with

tetrahydrocurcumin reduced fibrosarcoma cell (HT1080) adhesion to

the extracellular matrix and laminin, and the secretion of MMPs

(MMP-2 and MMP-9) and uPA (85).

It has also been shown to affect the migration and proliferation of

gingival fibroblast cells (86).

Chemically modified curcumin with a carbonyl substituent at the C-4

position exhibits better solubility, serum albumin-binding activity

and enhanced zinc-binding characteristics (87). 4-Metoxycarbonyl curcumin,

administered orally, was shown to inhibit MMP-9 and MMP-13 activity

more effectively than curcumin (by 2–7-fold). It also demonstrates

greater therapeutic activity, based on its inhibitory effect on

MMPs and pro-inflamatory mediators [TNF-α, IL-1β, monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-6 and prostaglandin (PGE)-2]

(87). In another study,

phenylamino carbonyl curcumin exerted inhibitory effects on MMPs in

rats with LPS-induced periodontitis; however, unlike curcumin, it

significantly reduced alveolar bone loss (88). The bioavailability of curcumin

extremely was shown to increase when combined with piperine (20

mg/kg) in rats and humans with no side-effects (89). Promising results were also

obtained in a recent study which used mucoadhesive nanoparticles

loaded with curcumin as a new approach with which to deliver

curcumin for the local treatment of oral cancer (90).

8. Conclusion

Clearly curcumin exhibits a variety of health

benefits; however, proof that the curcumin molecule itself is

responsible for these effects seems to be illusive. This is due to

the poor bioavailability, instability and strong reactivity of

curcumin. An additional complicating factor is the fact that

curcumin metabolizes differently depending on the type of

administration. The ability of curcumin to undergo degradation or

condensation strongly suggests that research should also focus on

the health benefits of these molecules rather than only on curcumin

itself.

References

|

1

|

Manolova Y, Deneva V, Antonov L, Drakalska

E, Momekova D and Lambov N: The effect of the water on the curcumin

tautomerism: A quantitative approach. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol

Spectrosc. 132:815–820. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fu S, Shen Z, Ajlouni S, Ng K, Sanguansri

L and Augustin MA: Interactions of buttermilk with curcuminoids.

Food Chem. 149:47–53. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gostner J, Ciardi C, Becker K, Fuchs D and

Sucher R: Immunoregulatory impact of food antioxidants. Curr Pharm

Des. 20:840–849. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gupta SC, Kismali G and Aggarwal BB:

Curcumin, a component of turmeric: From farm to pharmacy.

Biofactors. 39:2–13. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Maruta H: Herbal therapeutics that block

the oncogenic kinase PAK1: A practical approach towards

PAK1-dependent diseases and longevity. Phytother Res. 28:656–672.

2014. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Srinivasan K: Antioxidant potential of

spices and their active constituents. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.

54:352–372. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Current clinical trials on curcumin. US

National Institutes of Health, Clinical Trial Registry; June. 2015.

2015

|

|

8

|

Bar-Sela G, Epelbaum R and Schaffer M:

Curcumin as an anticancer agent: Review of the gap between basic

and clinical applications. Curr Med Chem. 17:190–197. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Chainani-Wu N: Safety and

anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin: A component of tumeric

(Curcuma longa). J Altern Complement Med. 9:161–168. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Goel A, Kunnumakkara AB and Aggarwal BB:

Curcumin as 'Curecumin': From kitchen to clinic. Biochem Pharmacol.

75:787–809. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Dhillon N, Aggarwal BB, Newman RA, Wolff

RA, Kunnumakkara AB, Abbruzzese JL, Ng CS, Badmaev V and Kurzrock

R: Phase II trial of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 14:4491–4499. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shen L and Ji HF: Contribution of

degradation products to the anticancer activity of curcumin. Clin

Cancer Res. 15:7108author reply 7108–7109. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang YJ, Pan MH, Cheng AL, Lin LI, Ho YS,

Hsieh CY and Lin JK: Stability of curcumin in buffer solutions and

characterization of its degradation products. J Pharm Biomed Anal.

15:1867–1876. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tønnesen HH: Solubility, chemical and

photochemical stability of curcumin in surfactant solutions.

Studies of curcumin and curcuminoids, XXVIII. Pharmazie.

57:820–824. 2002.

|

|

15

|

Schneider C, Gordon ON, Edwards RL and

Luis PB: Degradation of Curcumin: From Mechanism to Biological

Implications. J Agric Food Chem. 63:7606–7614. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Metzler M, Pfeiffer E, Schulz SI and Dempe

JS: Curcumin uptake and metabolism. Biofactors. 39:14–20. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Mohanty C and Sahoo SK: The in vitro

stability and in vivo pharmacokinetics of curcumin prepared as an

aqueous nanoparticulate formulation. Biomaterials. 31:6597–6611.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tønnesen HH and Karlsen J: Studies on

curcumin and curcuminoids. VI Kinetics of curcumin degradation in

aqueous solution. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 180:402–404. 1985.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Priyadarsini KI: The chemistry of

curcumin: From extraction to therapeutic agent. Molecules.

19:20091–20112. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Agrawal DK and Mishra PK: Curcumin and its

analogues: Potential anticancer agents. Med Res Rev. 30:818–860.

2010.

|

|

21

|

Mazumder A, Neamati N, Sunder S, Schulz J,

Pertz H, Eich E and Pommier Y: Curcumin analogs with altered

potencies against HIV-1 integrase as probes for biochemical

mechanisms of drug action. J Med Chem. 40:3057–3063. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jayaprakasam B, Vanisree M, Zhang Y,

Dewitt DL and Nair MG: Impact of alkyl esters of caffeic and

ferulic acids on tumor cell proliferation, cyclooxygenase enzyme,

and lipid peroxidation. J Agric Food Chem. 54:5375–5381. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jung KJ, Go EK, Kim JY, Yu BP and Chung

HY: Suppression of age-related renal changes in NF-kappaB and its

target gene expression by dietary ferulate. J Nutr Biochem.

20:378–388. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Murakami Y, Hirata A, Ito S, Shoji M,

Tanaka S, Yasui T, Machino M and Fujisawa S: Re-evaluation of

cyclooxygenase-2-inhibiting activity of vanillin and guaiacol in

macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Anticancer Res.

27:801–807. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chang YC, Lee FW, Chen CS, Huang ST, Tsai

SH, Huang SH and Lin CM: Structure-activity relationship of C6-C3

phenylpropanoids on xanthine oxidase-inhibiting and free

radical-scavenging activities. Free Radic Biol Med. 43:1541–1551.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shen L and Ji HF: Insights into the

inhibition of xanthine oxidase by curcumin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett.

19:5990–5993. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gordon ON and Schneider C: Vanillin and

ferulic acid: Not the major degradation products of curcumin.

Trends Mol Med. 18:361–363; author reply 363–364. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Gordon ON, Luis PB, Ashley RE, Osheroff N

and Schneider C: Oxidative transformation of demethoxy- and

bisdemethoxycurcumin: Products, mechanism of formation, and

poisoning of human topoisomerase IIα. Chem Res Toxicol. 28:989–996.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Griesser M, Pistis V, Suzuki T, Tejera N,

Pratt DA and Schneider C: Autoxidative and cyclooxygenase-2

catalyzed transformation of the dietary chemopreventive agent

curcumin. J Biol Chem. 286:1114–1124. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

30

|

Ketron AC, Gordon ON, Schneider C and

Osheroff N: Oxidative metabolites of curcumin poison human type II

topoisomerases. Biochemistry. 52:221–227. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

Ansari MJ, Ahmad S, Kohli K, Ali J and

Khar RK: Stability-indicating HPTLC determination of curcumin in

bulk drug and pharmaceutical formulations. J Pharm Biomed Anal.

39:132–138. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Heger M, van Golen RF, Broekgaarden M and

Michel MC: The molecular basis for the pharmacokinetics and

pharmacodynamics of curcumin and its metabolites in relation to

cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 66:222–307. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Tønnesen HH, de Vries H, Karlsen J and

Beijersbergen van Henegouwen G: Studies on curcumin and

curcuminoids. IX: Investigation of the photobiological activity of

curcumin using bacterial indicator systems. J Pharm Sci.

76:371–373. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tønnesen HH, Karlsen J and van Henegouwen

GB: Studies on curcumin and curcuminoids. VIII Photochemical

stability of curcumin. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 183:116–122. 1986.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Galer P and Šket B: Photodegradation of

methoxy substituted curcuminoids. Acta Chim Slov. 62:346–353. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Leite DP, Paolillo FR, Parmesano TN,

Fontana CR and Bagnato VS: Effects of photodynamic therapy with

blue light and curcumin as mouth rinse for oral disinfection: A

randomized controlled trial. Photomed Laser Surg. 32:627–632. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mahdi Z, Habiboallh G, Mahbobeh NN, Mina

ZJ, Majid Z and Nooshin A: Lethal effect of blue light-activated

hydrogen peroxide, curcumin and erythrosine as potential oral

photosensitizers on the viability of Porphyromonas gingivalis and

Fusobacterium nucleatum. Laser Ther. 24:103–111. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yin R and Hamblin MR: Antimicrobial

photosensitizers: Drug discovery under the spotlight. Curr Med

Chem. 22:2159–2185. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Skrzypczak-Jankun E, Zhou K, McCabe NP,

Selman SH and Jankun J: Structure of curcumin in complex with

lipoxygenase and its significance in cancer. Int J Mol Med.

12:17–24. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jankun J, Doerks T, Aleem AM,

Lysiak-Szydłowska W and Skrzypczak-Jankun E: Do human lipoxygenases

have a PDZ regulatory domain? Curr Mol Med. 8:768–773. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ji HF and Zhang HY: Multipotent natural

agents to combat Alzheimer's disease. Functional spectrum and

structural features. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 29:143–151. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang HY: One-compound-multiple-targets

strategy to combat Alzheimer's disease. FEBS Lett. 579:5260–5264.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Barik A, Mishra B, Kunwar A, Kadam RM,

Shen L, Dutta S, Padhye S, Satpati AK, Zhang HY and Indira

Priyadarsini K: Comparative study of copper(II)-curcumin complexes

as superoxide dismutase mimics and free radical scavengers. Eur J

Med Chem. 42:431–439. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Barik A, Mishra B, Shen L, Mohan H, Kadam

RM, Dutta S, Zhang HY and Priyadarsini KI: Evaluation of a new

copper(II)-curcumin complex as superoxide dismutase mimic and its

free radical reactions. Free Radic Biol Med. 39:811–822. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Eybl V, Kotyzová D, Lesetický L, Bludovská

M and Koutenský J: The influence of curcumin and manganese complex

of curcumin on cadmium-induced oxidative damage and trace elements

status in tissues of mice. J Appl Toxicol. 26:207–212. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Fouladvand M, Barazesh A and Tahmasebi R:

Evaluation of in vitro antileishmanial activity of curcumin and its

derivatives 'gallium curcumin, indium curcumin and diacethyle

curcumin'. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 17:3306–3308. 2013.

|

|

47

|

Gaurav C, Goutam R, Rohan KN, Sweta KT,

Abhay CS and Amit GK: (Copper-curcumin) beta-cyclodextrin vaginal

gel: delivering a novel metal-herbal approach for the development

of topical contraception prophylaxis. Eur J Pharm Sci. 65:183–191.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hatcher H, Planalp R, Cho J, Torti FM and

Torti SV: Curcumin: From ancient medicine to current clinical

trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 65:1631–1652. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

John VD, Kuttan G and Krishnankutty K:

Anti-tumour studies of metal chelates of synthetic curcuminoids. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 21:219–224. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zebib B, Mouloungui Z and Noirot V:

Stabilization of curcumin by complexation with divalent cations in

glycerol/water system. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2010:2927602010.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

51

|

Mei X, Xu D and Xu S, Zheng Y and Xu S:

Gastroprotective and antidepressant effects of a new

zinc(II)-curcumin complex in rodent models of gastric ulcer and

depression induced by stresses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 99:66–74.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yu C, Mei XT, Zheng YP and Xu DH:

Zn(II)-curcumin protects against hemorheological alterations,

oxidative stress and liver injury in a rat model of acute

alcoholism. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 37:729–737. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Refat MS: Synthesis and characterization

of ligational behavior of curcumin drug towards some transition

metal ions: Chelation effect on their thermal stability and

biological activity. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc.

105:326–337. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Barik A, Priyadarsini KI and Mohan H:

Photophysical studies on binding of curcumin to bovine serum

albumins. Photochem Photobiol. 77:597–603. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wootton LL and Michelangeli F: The effects

of the phenylalanine 256 to valine mutation on the sensitivity of

sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA)

Ca2+ pump isoforms 1, 2, and 3 to thapsigargin and other

inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 281:6970–6976. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Logan-Smith MJ, Lockyer PJ, East JM and

Lee AG: Curcumin, a molecule that inhibits the

Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum but increases the

rate of accumulation of Ca2+. J Biol Chem.

276:46905–46911. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Hasmeda M and Polya GM: Inhibition of

cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase by curcumin. Phytochemistry.

42:599–605. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Jung KT and Lim KJ: Curcumin, COX-2, and

Protein p300/CBP. Korean J Pain. 27:365–366. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Bukhari SN, Lauro G, Jantan I, Bifulco G

and Amjad MW: Pharmacological evaluation and docking studies of

α,β-unsaturated carbonyl based synthetic compounds as inhibitors of

secretory phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenases,

lipoxygenase and proinflammatory cytokines. Bioorg Med Chem.

22:4151–4161. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Skrzypczak-Jankun E, McCabe NP, Selman SH

and Jankun J: Curcumin inhibits lipoxygenase by binding to its

central cavity: Theoretical and X-ray evidence. Int J Mol Med.

6:521–526. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Hong J, Bose M, Ju J, Ryu JH, Chen X, Sang

S, Lee MJ and Yang CS: Modulation of arachidonic acid metabolism by

curcumin and related beta-diketone derivatives: Effects on

cytosolic phospholipase A(2), cyclooxygenases and 5-lipoxy-genase.

Carcinogenesis. 25:1671–1679. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Heng MC: Signaling pathways targeted by

curcumin in acute and chronic injury: Burns and photo-damaged skin.

Int J Dermatol. 52:531–543. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Reddy S and Aggarwal BB: Curcumin is a

non-competitive and selective inhibitor of phosphorylase kinase.

FEBS Lett. 341:19–22. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Manikandan P, Sumitra M, Aishwarya S,

Manohar BM, Lokanadam B and Puvanakrishnan R: Curcumin modulates

free radical quenching in myocardial ischaemia in rats. Int J

Biochem Cell Biol. 36:1967–1980. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Lin JK and Shih CA: Inhibitory effect of

curcumin on xanthine dehydrogenase/oxidase induced by

phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate in NIH3T3 cells. Carcinogenesis.

15:1717–1721. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Aggarwal BB, Surh J and Shishodia S: The

Molecular Targets and Therapeutic Uses of Curcumin in Health and

Disease. Springer; New York, NY: 2007, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Asai A and Miyazawa T: Occurrence of

orally administered curcuminoid as glucuronide and

glucuronide/sulfate conjugates in rat plasma. Life Sci.

67:2785–2793. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Holder GM, Plummer JL and Ryan AJ: The

metabolism and excretion of curcumin

(1,7-bis-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione) in

the rat. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological

systems. 8:761–768. 1978. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Wahlström B and Blennow G: A study on the

fate of curcumin in the rat. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh).

43:86–92. 1978. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA and

Aggarwal BB: Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises.

Mol Pharm. 4:807–818. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Garcea G, Jones DJ, Singh R, Dennison AR,

Farmer PB, Sharma RA, Steward WP, Gescher AJ and Berry DP:

Detection of curcumin and its metabolites in hepatic tissue and

portal blood of patients following oral administration. Br J

Cancer. 90:1011–1015. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Kim GY, Kim KH, Lee SH, Yoon MS, Lee HJ,

Moon DO, Lee CM, Ahn SC, Park YC and Park YM: Curcumin inhibits

immunostimulatory function of dendritic cells: MAPKs and

translocation of NF-kappa B as potential targets. J Immunol.

174:8116–8124. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Mun SH, Kim HS, Kim JW, Ko NY, Kim K, Lee

BY, Kim B, Won HS, Shin HS, Han JW, et al: Oral administration of

curcumin suppresses production of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1

and MMP-3 to ameliorate collagen-induced arthritis: Inhibition of

the PKCdelta/JNK/c-Jun pathway. J Pharmacol Sci. 111:13–21. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Kirkwood KL, Cirelli JA, Rogers JE and

Giannobile WV: Novel host response therapeutic approaches to treat

periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 43:294–315. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Mahakunakorn P, Tohda M, Murakami Y,

Matsumoto K, Watanabe H and Vajaragupta O: Cytoprotective and

cytotoxic effects of curcumin: Dual action on H2O2-induced

oxidative cell damage in NG108-15 cells. Biol Pharm Bull.

26:725–728. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Guimarães MR, Coimbra LS, de Aquino SG,

Spolidorio LC, Kirkwood KL and Rossa C Jr: Potent anti-inflammatory

effects of systemically administered curcumin modulate periodontal

disease in vivo. J Periodontal Res. 46:269–279. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Jagetia GC and Rajanikant GK: Curcumin

treatment enhances the repair and regeneration of wounds in mice

exposed to hemibody gamma-irradiation. Plast Reconstr Surg.

115:515–528. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Madhyastha R, Madhyastha H, Nakajima Y,

Omura S and Maruyama M: Curcumin facilitates fibrinolysis and

cellular migration during wound healing by modulating urokinase

plasminogen activator expression. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb.

37:59–66. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Oh S, Kyung TW and Choi HS: Curcumin

inhibits osteoclastogenesis by decreasing receptor activator of

nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) in bone marrow stromal cells.

Mol Cells. 26:486–489. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Singh R, Chandra R, Bose M and Luthra MP:

Antibacterial activity of curcumin longa rhizome extract on

periopathogenic bacteria. Curr Sci. 83:737–740. 2002.

|

|

81

|

Bhatia M, Urolagin SS, Pentyala KB,

Urolagin SB, Menaka KB and Bhoi S: Novel therapeutic approach for

the treatment of periodontitis by curcumin. J Clin Diagn Res.

8:ZC65–ZC69. 2014.

|

|

82

|

Gottumukkala SN, Koneru S, Mannem S and

Mandalapu N: Effectiveness of sub gingival irrigation of an

indigenous 1% curcumin solution on clinical and microbiological

parameters in chronic periodontitis patients: A pilot randomized

clinical trial. Contemp Clin Dent. 4:186–191. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Khafif A, Schantz SP, Chou TC, Edelstein D

and Sacks PG: Quantitation of chemopreventive synergism between

(−)-epigal-locatechin-3-gallate and curcumin in normal,

premalignant and malignant human oral epithelial cells.

Carcinogenesis. 19:419–424. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Pari L and Murugan P: Tetrahydrocurcumin:

Effect on chloroquine-mediated oxidative damage in rat kidney.

Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 99:329–334. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Yodkeeree S, Garbisa S and Limtrakul P:

Tetrahydrocurcumin inhibits HT1080 cell migration and invasion via

downregulation of MMPs and uPA. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 29:853–860.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

San Miguel SM, Opperman LA, Allen EP,

Zielinski J and Svoboda KK: Bioactive antioxidant mixtures promote

proliferation and migration on human oral fibroblasts. Arch Oral

Biol. 56:812–822. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Gu Y, Lee HM, Napolitano N, Clemens M,

Zhang Y, Sorsa T, Zhang Y, Johnson F and Golub LM:

4-methoxycarbonyl curcumin: A unique inhibitor of both inflammatory

mediators and periodontal inflammation. Mediators Inflamm.

2013:3297402013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Elburki MS, Rossa C, Guimaraes MR,

Goodenough M, Lee HM, Curylofo FA, Zhang Y, Johnson F and Golub LM:

A novel chemically modified curcumin reduces severity of

experimental periodontal disease in rats: Initial observations.

Mediators Inflamm. 2014:9594712014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Shoba G, Joy D, Joseph T, Majeed M,

Rajendran R and Srinivas PS: Influence of piperine on the

pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers.

Planta Med. 64:353–356. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Mazzarino L, Loch-Neckel G, Bubniak LS,

Mazzucco S, Santos-Silva MC, Borsali R and Lemos-Senna E:

Curcumin-loaded chitosan-coated nanoparticles as a new approach for

the local treatment of oral cavity cancer. J Nanosci Nanotechnol.

15:781–791. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Gordon ON, Luis PB, Sintim HO and

Schneider C: Unraveling curcumin degradation: Autoxidation proceeds

through spiroepoxide and vinylether intermediates en route to the

main bicyclopentadione. J Biol Chem. 290:4817–4828. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Kaźmierkiewicz R, Czaplewski C and

Ciarkowski J: Elucidation of neurophysin/bioligand interactions

from molecular modeling. Acta Biochim Pol. 44:453–466. 1997.

|

|

93

|

Zhang YL, Tropsha A, McPhail AT and Lee

KH: Antitumor agents. 152 In vitro inhibitory activity of etoposide

derivative NPF against human tumor cell lines and a study of its

conformation by X-ray crystallography, molecular modeling, and NMR

spectroscopy. J Med Chem. 37:1460–1464. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|