Introduction

According to the statistics, almost a quarter of

female patients suffering from cancer are diagnosed with breast

cancer (1). As the most typical

type of cancer affecting women, even in an era with advanced

medical applications, breast cancer remains a serious concernt and

a threat to human health, causing significant morbidity and

mortality (2). Several subtypes

of breast cancer, each requiring different therapeutic regimens,

limit the treatment options. The standard treatment for breast

cancer is chemotherapy and radiotherapy; however, treatment

outcomes are, in the most part, discouraging for patients (3). In this scenario, it is imperative to

explore different alternative therapies or medicines with low

toxicicity for breast cancer treatment.

Due to the significant cytotoxic activities and less

adverse effects, herbal medicines have gradually become good

candidates for cancer therapy (4). It has been proven that Cordyceps

militaris, a folk tonic in Asia, displays pro-apoptotic

properties in cells and tumor xenografts in C57BL/6 mice via

mitochondrial-related pathways (5,6).

As a type of food and medical fungus, Grifola frondosa has

been studied for years, and amino acids, polysaccharides and

amounts of trace elements have been found in its fruitbody. Since

the first study on the anti-tumor effects of Grifola

frondosa polysaccharide (GFP) in 1984, the structure and

function of its polysaccharides have been gradually analyzed

(7). Pharmacological analyses and

clinical trials have demonstrated that the polysaccharide-enriched

extract of Grifola frondosa exhibits various activities,

including anti-tumor, immunomodulatory, and blood glucose and lipid

regulating effects (8–10). A chemically sulfated

polysaccharide purified from Grifola frondosa has also been

shown to induce HepG2 cell apoptosis via the Notch 1-NF-κB pathway

(11). However, few studies to

date have reported the pro-apoptotic activities of GFP on breast

cancer cells and the underlying mechanisms.

Apoptosis, an energy-dependent process, is regulated

by various signals (12). During

this process, cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation and DNA damage

are observed (13). Mitochondrial

apoptosis occurs gradually along with the depolarization of

mitochondrial transmembrane potential (MMP; ΔΨm), the abnormal

expressions of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family members, cytochrome

c (Cyto c) over-release and caspase-3 activation

(14,15). The initiator caspase (caspase-8)

controls the proteolytic maturation of caspase-3 (16). The accumulation of intracellular

reactive oxygen species (ROS) is capable of inducing apoptosis by

interacting with proteins related to mitochondrial dysfunction. On

the other hand, the activation of AKT and extracellular

signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) contributes to cell proliferation

and apoptosis (17,18).

This study aimed to investigate the anti-breast

cancer effects of GFP in in vitro and in vivo models.

We found that in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, GFP induced apoptotic

cell death related to mitochondrial function. GFP also

significantly suppressed the growth of MCF-7 tumor xenografts in

nude mice. Our data support the possible use of Grifola

frondosa as a therapeutic agent for breast cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Preparation of polysaccharides separated

from Grifola frondosa

Grifola frondosa powder (100 g) was extracted

twice with 10-fold double-distilled water (DD water) at 90°C for 3

h. The protein existing in the extract was removed using Sevag

reagent [v (n-butanol):v (chloroform) = 1:4, 50 ml].

Polysaccharides were collected via the alcohol precipitation method

with 4-fold ethanol. The content of the total polysaccharides

separated from Grifola frondosa was 65.2±1.05 mg/g.

Cell culture

The cell lines, MDA-MB-231 (human breast epithelial

cell line; ATCC no. HTB-26) and MCF-7 (human breast carcinoma cell

line; ATCC no. HTB-22), were maintained in Dulbecco's modified

Eagle's medium (DMEM) medium, supplemented with a 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 g/ml streptomycin under a

humidified atmosphere containing 5%/95% of CO2/air at

37°C. The cultured medium was refreshed every 3 days. Cell culture

reagents were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad,

CA, USA).

MTT cell survival assay

The cells (5,000 cells/100 μl) were seeded

into 96-well plates and incubated with GFPs at concentrations of

25, 50, 100, 200 and 400 μg/ml for 24 or 48 h. Subsequently,

10 μl of

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

(0.5 mg/ml) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were added

to each well. Following a 4-h incubation at 37°C in the dark, the

supernatant was aspirated, and then 100 μl DMSO were added.

The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm using a

microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Values were expressed as a percentage of those from the

corresponding controls.

Analysis of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

concentration and caspase-3 activation

The cells (5×104) were seeded into 6-well

plates and treated with 50 and 200 μg/ml GFPs for 24 h. The

LDH concentration in the culture medium was detected using a LDH

assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing,

China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The treated cells were collected and lysed with

radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St.

Louis, MO, USA), and the protein concentration was examined using

Bio-Rad protein assays. A caspase-3 colorimetric detection kit

(Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA) was applied to

detect caspase-3 activation. Values were expressed as a percentage

of those from the corresponding controls.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell

apoptosis

The cells were seeded into 6-well plates at

5×104/well and treated with 50 and 200 μg/ml GFPs

for 12 h. The treated cells were harvested and washed with PBS 3

times, and then suspended in binding buffer containing with 5

μl Annexin V-FITC (20 μg/ml) and 5 μl

propidium iodide (PI; 50 μg/ml) (BD Biosciences, Franklin

Lakes, NJ, USA). Following a 15-min incubation at room temperature

in the dark, the apoptotic rate was analyzed using a flow cytometer

(FC500; Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA).

Detection of ROS

Following treatment with GFPs for 12 h at

concentrations of 50 and 200 μg/ml, the cells were suspended

and incubated with 10 μM dichlorodihydrofluorescein

diacetate (DCFH-DA) for 10 min at 37°C in the dark. After being

washed with PBS 3 times, the intracellular ROS levels were

determined using a flow cytometer (FC500; Beckman Coulter).

Detection of MMP

The cells were seeded into 6-well plates at

5×104/well and treated with 50 and 200 μg/ml GFPs

for 12 h. The cells were further incubated with 2 μM

5,5′,6,6′-tetra-chloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine

iodide (JC-1; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 10 min. After being washed

with PBS, the changes in fluorescent color were examined using a

fluorescence microscope (x20 magnification; CCD camera, TE2000;

Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

MCF-7 tumor xenograft model

Six-week-old male BALB/c nude mice purchased from

Weitong Lihua Laboratory Animal Technology Ltd. Co. (Beijing,

China) were used in our in vivo experiments. The protocol

was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Jilin University.

The mice were housed in groups 3 per cage and maintained on a 12 h

light/dark cycle at 23±1°C with water and food available ad

libitum.

An amount of 0.1 ml (1×108 cells/ml) of

MCF-7 cells at the mid-log phase was inoculated subcutaneously into

the right flank of BALB/c nude mice. When the diameter of the tumor

reached to 3–5 mm, the mice were divided into 2 groups (n=3 each)

randomly, and orally treated with 0.5 g/kg GFPs or DD water every

other day continuously for 2 weeks. During the GFP administration,

the body weight and tumor dimension were measured. The equation of

length × (width)2 × 0.5 was applied to estimate the

tumor volume (mm3). All the mice were sacrificed via an

injection of 200 mg/kg pentobarbital after the final treatment, and

tumor tissues were dissected.

Western blot analysis

The MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 (2×105 cells)

were seeded into 6-well plates and exposed vaqrious concentrations

of GFPs for the indicated periods of time. The cells and collected

tumor tissues were lysed by RIPA buffer containing 1% protease

inhibitor cocktail and 2% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)

(both from Sigma-Aldrich). The bicinchoninic acid method was

applied to detect the protein concentrations. Protein samples (40

μg) were separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel, and then

electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 μm; Bio

Basic, Inc., Markham, ON, Canada). The membranes were incubated at

4°C overnight with Bcl-2 (MABC573), Bcl-extra large (Bcl-xL;

MAB4625), Bax (AB2915), cleaved caspase-3 (AB3623), cleaved

caspase-8 (AB1879), and phosphorylated (p)-AKT (05–1003) (all from

Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), total (t)-AKT (ab126811) and

p-glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) (ab75745) (both from Abcam,

Cambrige, UK), T-GSK-3β (PK1111) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (ABS16) (both from Merck Millipore) at

dilution of 1:1,000. The membranes were then incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 2 h at room

temperature. Band detection was performed using enhanced

chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kits (GE Healthcare Life

Sciences, Chalfont, UK). The intensity of the bands was quantified

using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the means ± standard deviation

(SD) and analyzed by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

followed with Dunn's test using SPSS software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago,

IL, USA). The IC50 values are calculated using SPSS 16.0

software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A value P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Intracellular toxic effects of GFPs on

breast cancer cells

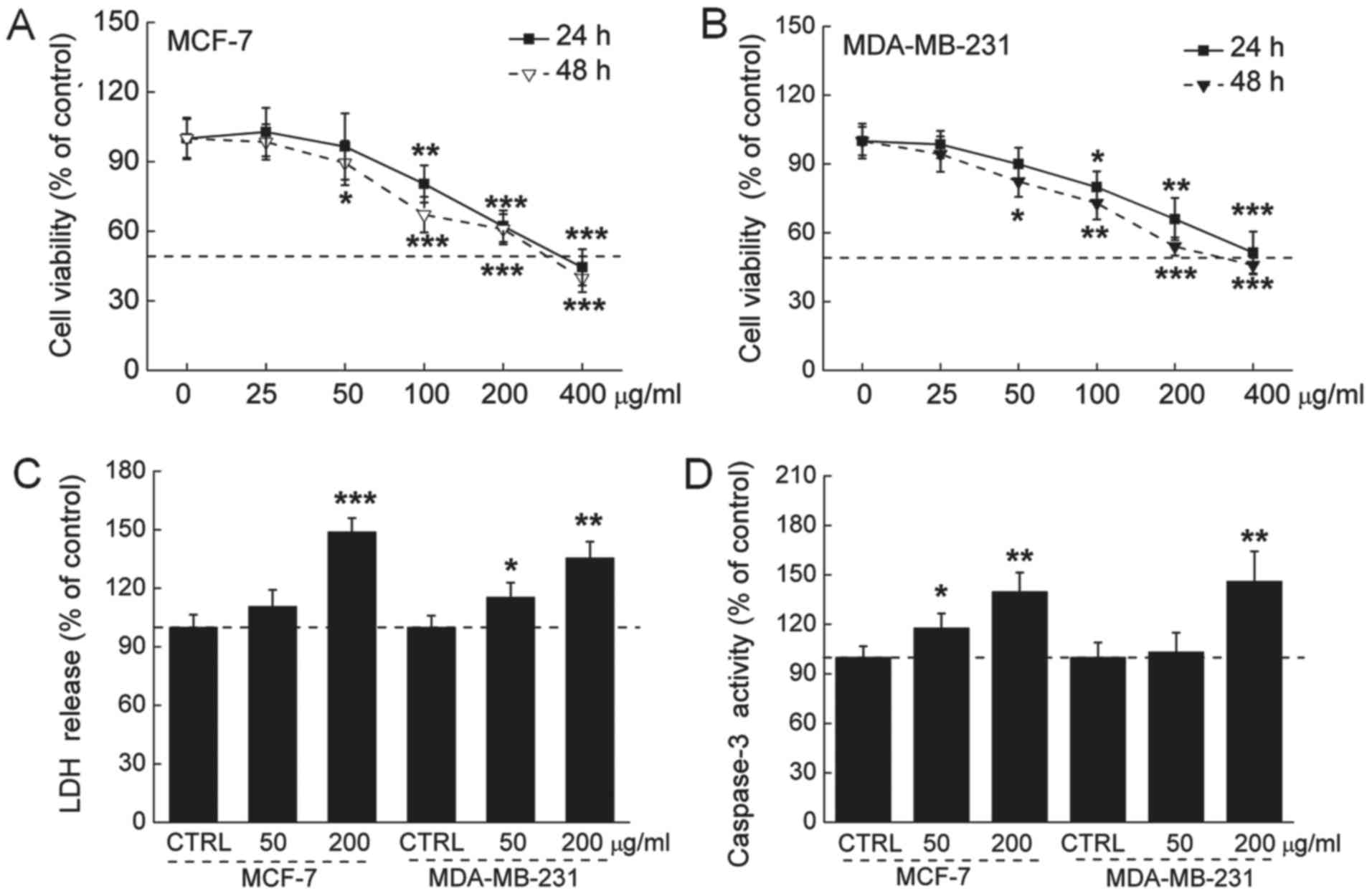

The 24-h IC50 values of the GFPs were 335

and 412 μg/ml, and the 48-h IC50 values of the

GFPs were 295 and 348 µg/ml in the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

cells, respectively (Fig. 1A and

B). The release of LDH was increased during cell death. An

approximately 47 and 32% LDH over-release was observed in the 200

µg/ml GFP-treated MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (P<0.01;

Fig. 1C). The activation of

caspase-3 serves as a marker of cell apoptosis. We found that the

GFPs at 200 µg/ml enhanced caspase-3 activation by almost 35

and 43% in the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively (P<0.01;

Fig. 1D).

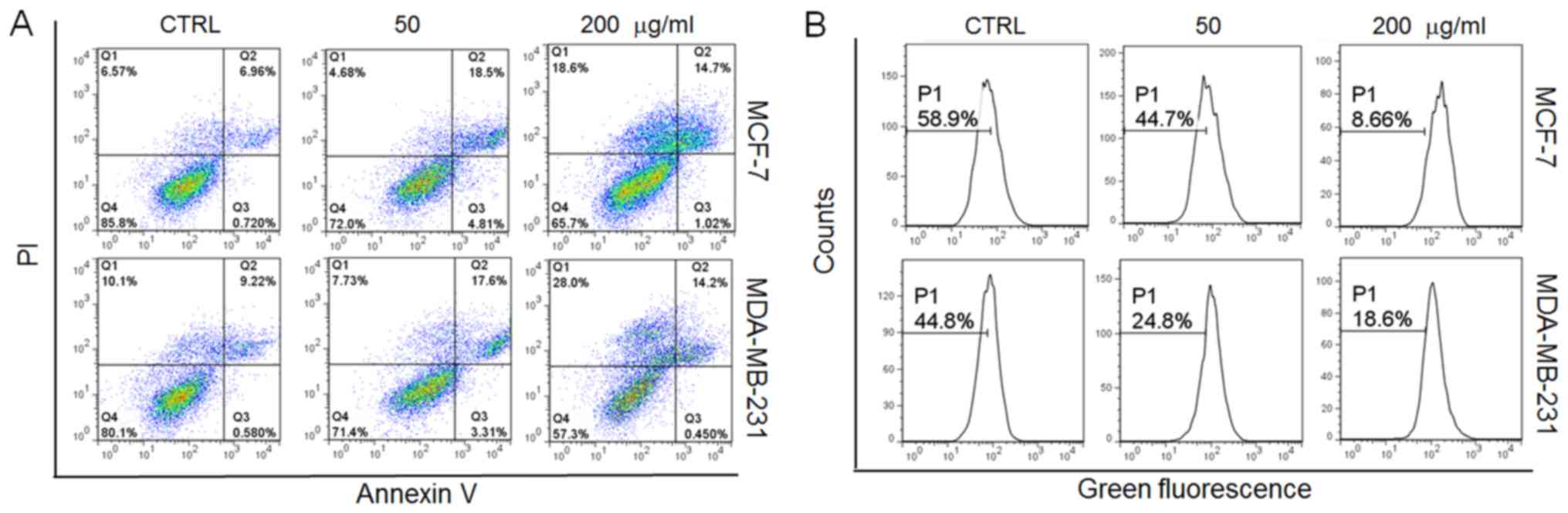

In addition, incubation with the GFPs (50

μg/ml) for 12 h led to approximately 22 and 21% of the MCF-7

and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively to become apoptotic (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, oxidative stress,

particularly, the overproduction of intracellular ROS, leads to

cellular dysfunction and apoptosis (19). In this study, following incubation

with the GFPs for 12 h at 200 μg/ml, a 50 and 26% increment

in intracellular ROS levels was noted in the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

cells, respectively compared with the controls (Fig. 2B). All these data confirmed that

GFPs exerted cytotoxic effects on the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

cells.

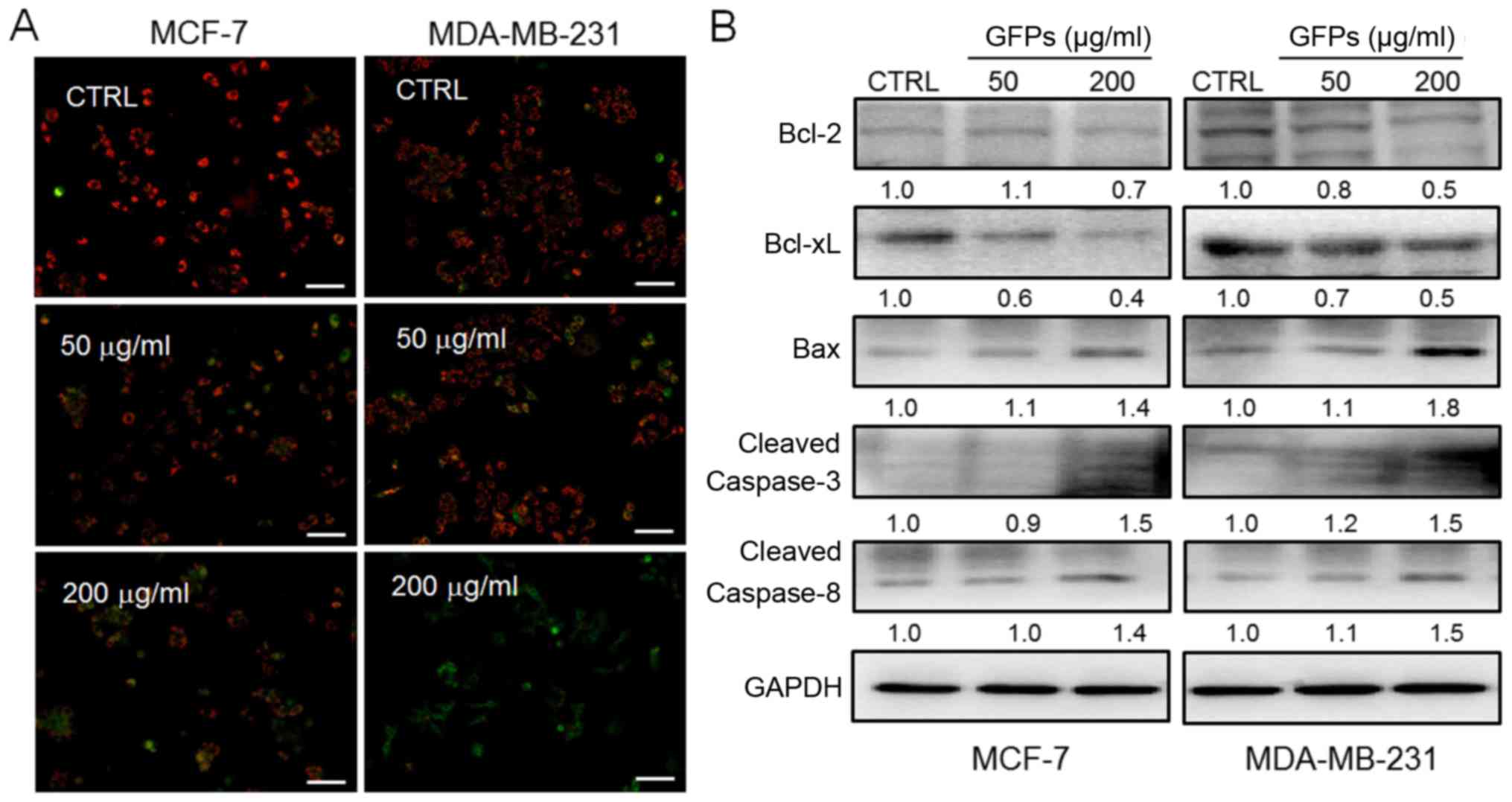

GFPs cause mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondrial function plays a central role during

cell apoptosis (20). As

indicated by the reduced ratio of red to green fluorescence by JC-1

staining, treatment with the GFPs for 12 h at concentrations of 50

and 200 μg/ml significantly decreased MMP in the MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells, compared with untreated cells (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the increased

expression levels of Bax, cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-8, and the

reduced levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL were observed in the MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells following incubation with the GFPs for 24 h GFPs

at concentrations of 50 and 200 μg/ml (Fig. 3B).

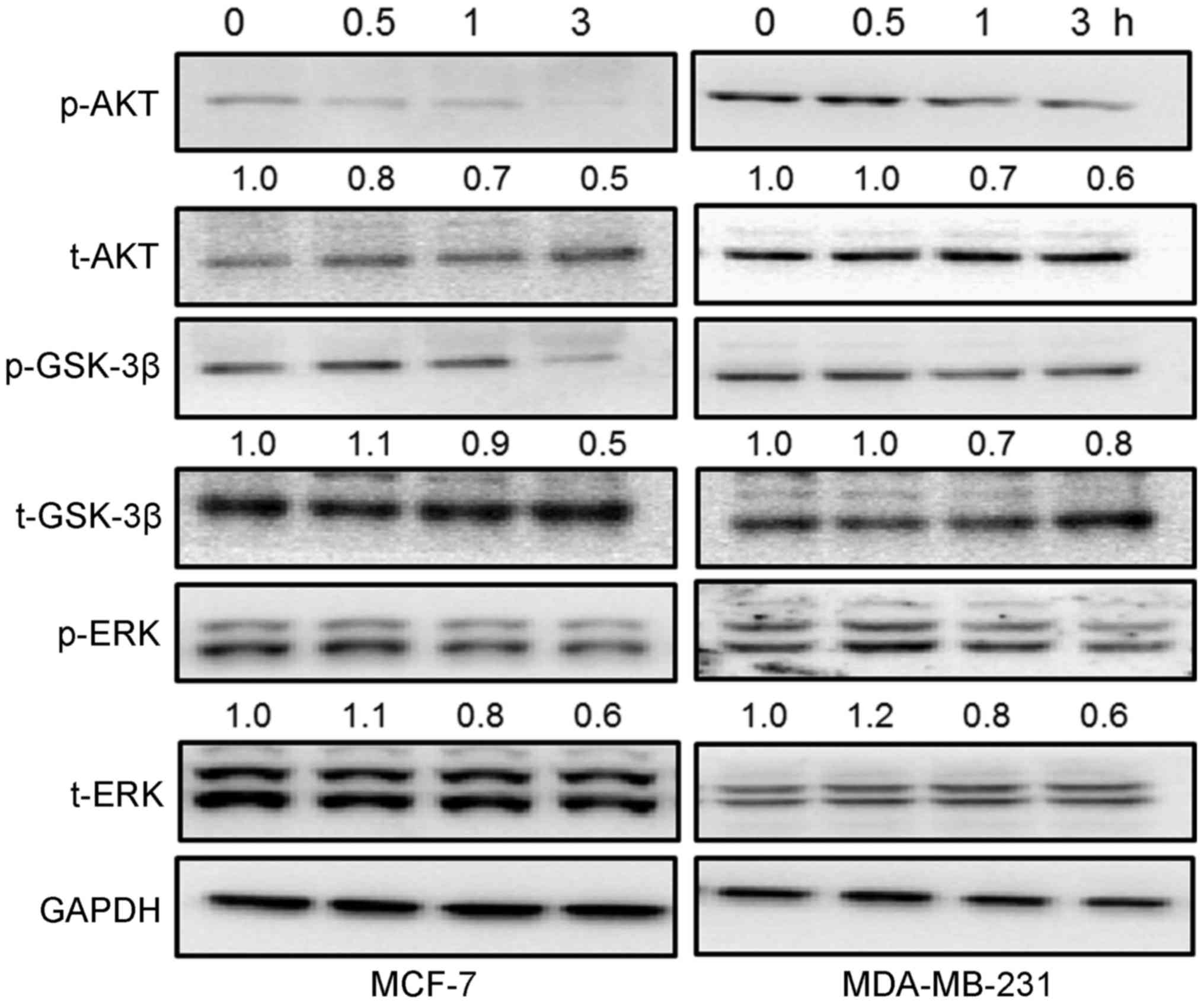

The activation of AKT/GSK-3β and ERK is

involved in GFP-mediated cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells

It has been reported that the activation of

AKT/GSK-3β and ERK participate in cell proliferation, survival and

even apoptosis (21,22). The GFPs time-dependently

suppressed the phosphorylation of AKT and GSK-3β from 0.5 to 3 h in

the breast cancer cells incubated with 200 μg/ml of GFPs,

particularly at 1 and 3 h (Fig.

4). In addition, incubation with 200 μg/ml GFPs

significantly inhibited the activation of ERK from 1 and 3 h in the

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig.

4).

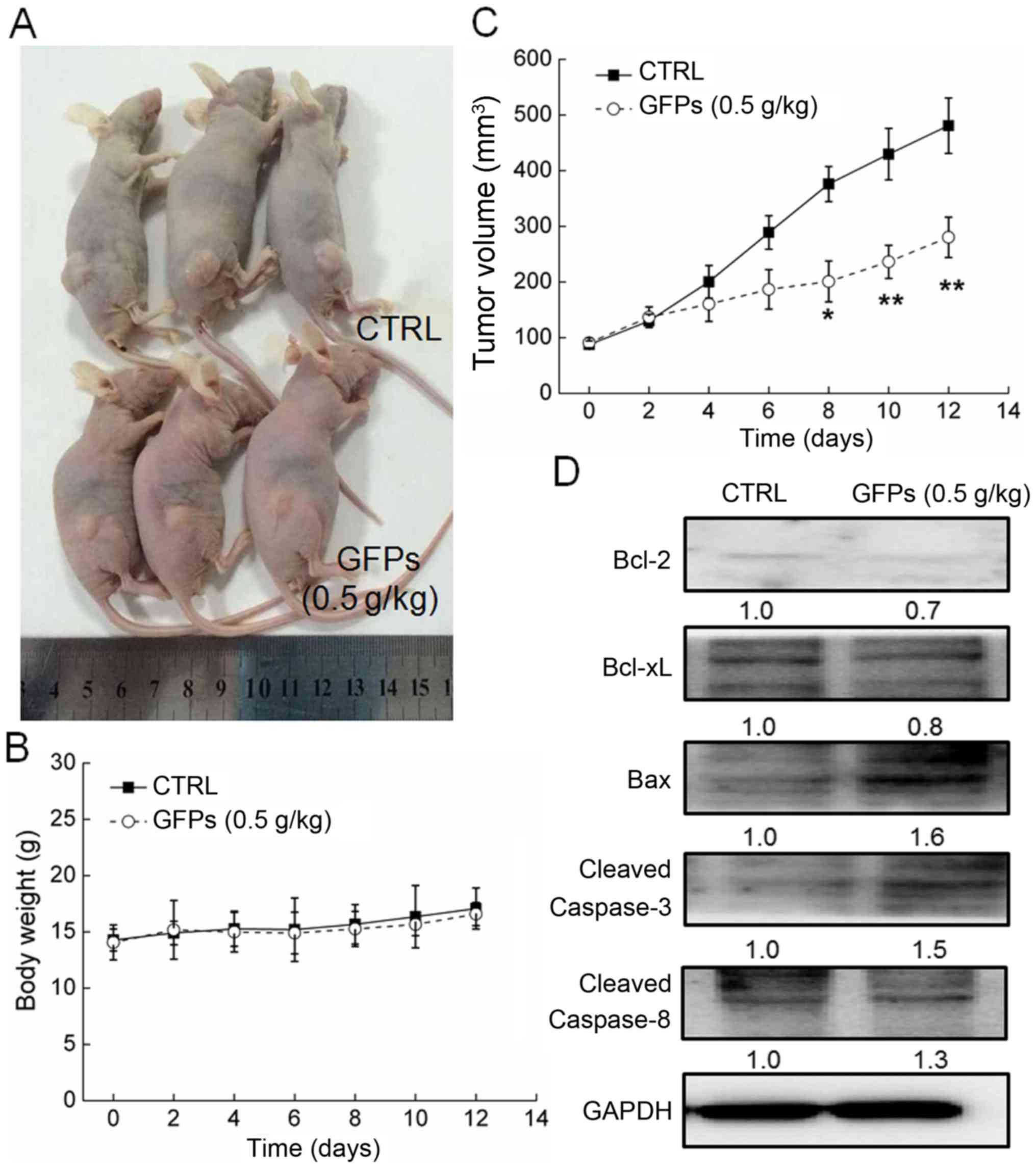

GFPs inhibits the growth of MCF-7 tumor

xenografts

GFP administration at 0.5 g/kg significantly

suppressed the growth of MCF-7 tumor xenografts from the 8th day to

the end of the experiment (P<0.05; Fig. 5A and C). Compared with the

controls, GFPs decreased the tumor size by almost 42% on the 14th

day (P<0.01; Fig. 5C). The

GFPs did not to influence the body weight of the mice compared with

the untreated mice, which suggested limited aggressive side-effects

(Fig. 5B). Additionally, compared

with the controls, in the tumor tissues from the treated mice, GFPs

increased the expression levels of Bax, cleaved caspase-3 and

caspase-8, and suppressed the expression levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL

(Fig. 5D).

Discussion

In the present study, the potential anti-tumor

effects of GPFs on breast cancer were successfully confirmed in

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, and tumor-bearing nude mice. The GFPs

exerted cytotoxic effects on the breast cancer cell lines, as

evidenced by a decrease in cell viability, and an increase in LDH

release, ROS accumulation and caspase-3 activation, as well as the

induction of cell apoptosis and mitochondrial apoptotic

alterations. The suppressed phosphorylation of AKT/GSk-3β and ERK,

related to mitochondrial function, revealed the possible mechanisms

involved.

During apoptosis, which is a physiological suicide

process, mitochondrial function plays a central role (23). The functional loss of the

mitochondria is related to the dissipation of MMP (20), which was noted in this study

following incubation with the GFPs for 12 h. The reduced Bcl-2 and

Bcl-xL levels, and enhanced Bax expression levels were also

observed in the GFP-treated cells. The Bcl-2 family, located in the

outer mitochondrial membrane, serves as an important index in

mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis (24). Moreover, in this study, the

accumulation of intracellular ROS was observed in the cells treated

with the GFPs. The overproduction of ROS causes oxidative stress,

further resulting in mitochondrial apoptosis and cellular

dysfunction. It has been reported that ROS accumulation is

responsible for the opening mitochondrial permeability transition

pore (mPTP), which leads to mitochondrial depolarization, matrix

solutes loss and Cyto c release (25). Taken together, the effects of GFPs

on mitochondrial function are involved in its anti-breast cancer

effects.

On the other hand, mitochondria control the

intrinsic pathway of apoptosis, and during this process, MMP

ignites caspases and other catabolic enzyme activation (26). Caspases are considered as inactive

pro-enzymes and will be activated via proteolytic cleavage

(27). Caspase-8, located mostly

in the mitochondria, undergoes dimerization, and then cleaves

itself to its fully activated form (28), which further leads to the

cleavages of effector caspases in the cytosol (caspase-3) (29). Caspase-3, amplifying the

initiation signals from caspase-8, plays a central role in

activating the apoptotic program via regulating other caspases and

some vital proteins (30), and it

is important for cell death in a tissue-, cell type- or death

stimulus-specific manner (31).

In this study, in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, and MCF-7 tumor

xenografts, GFPs significantly enhanced the expressions of cleaved

caspase-3 and caspase-8, which revealed that the anticancer

activity of GFPs was associated with the regulation on caspase

activation, which further targets the mitochondria.

AKT signaling is responsible for cell proliferation

and apoptosis, which regulates apoptotic proteins including Bcl-2

family members GSK-3β (21). The

reduced phosphorylation of AKT activates its downstream GSK-3β,

which promotes Bax activation (32). As previously reported, GSK-3β

mediates the release of cytochrome c into the cytosol, and

its activated form helps to open mPTP (33). Via the AKT/GSK-3β- and

ROS-dependent mitochondrial-mediated pathway, 18β-glycyrrhetinic

acid induces the apoptosis of pituitary adenoma cells (23). Furthermore, the ERK pathway has

been reported to be a target for cancer therapy, which is

hyper-acted in human tumors (34,35). p-ERK, an active form, inhibits

pro-apoptotic signals via the modulation of numerous substrates

(22). In our study, the GFPs

strongly suppressed the phosphorylation of AKT/GSK-3β and ERK in

the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, and this suppression may be

involved in the GFP-mediated anti-tumor effects. Furthermore, ERK

has been shown to exert positive regulatory effects on Bcl-2 and

Bcl-xL expression, and ERKs/Bcl-2 have been confirmed as potential

targets for cancer cell apoptosis (36,37). Previous studies have indicated

that AKT contributes to the maintenance of mitochondrial integrity,

which also affects Bcl-2 expression (38,39). Collectively, the downregulation of

AKT/GSK-3β and ERK activation contributes to GFP-induced

mitochondrial apoptosis.

The anti-breast cancer effects of GFPs were

successfully confirmed in in vitro and in vivo

experiments. GFPs reduced cell viability, enhanced the apoptotic

rate, increased the ROS and caspase-3 intracellular levels, and

caused LDH over-release, as well as MMP dissipation and the

abnormal expression of pro-apoptotic proteins. The suppressed

activation of ERK and AKT/GSK-3β in the GFP-incubated cells was

responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction. All these findings

reveal that the mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic pathway

contributes to GFP-induced cytotoxicity in the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

cells, which provides pharmacological evidence to support the use

of GFPs as a potential chemotherapeutic agent.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Jilin Province Science

and Technology Key Problem of China (2014020314YY).

References

|

1

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward

E and Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin.

61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hosseini BA, Pasdaran A, Kazemi T,

Shanehbandi D, Karami H, Orangi M and Baradaran B: Dichloromethane

fractions of Scrophularia oxysepala extract induce apoptosis in

MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 15:26–32.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chang CH, Chen SJ and Liu CY: Adjuvant

treatments of breast cancer increase the risk of depressive

disorders: a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 182:44–49.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Vadodkar AS, Suman S, Lakshmanaswamy R and

Damodaran C: Chemoprevention of breast cancer by dietary compounds.

Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 12:1185–1202. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jin CY, Kim GY and Choi YH: Induction of

apoptosis by aqueous extract of Cordyceps militaris through

activation of caspases and inactivation of Akt in human breast

cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 18:1997–2003.

2008.

|

|

6

|

Yoo HS, Shin JW, Cho JH, Son CG, Lee YW,

Park SY and Cho CK: Effects of Cordyceps militaris extract on

angiogenesis and tumor growth. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 25:657–665.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ohno N, Suzuki I, Oikawa S, Sato K,

Miyazaki T and Yadomae T: Antitumor activity and structural

characterization of glucans extracted from cultured fruit bodies of

Grifola frondosa. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 32:1142–1151. 1984.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Inoue A, Kodama N and Nanba H: Effect of

maitake (Grifola frondosa) D-fraction on the control of the T lymph

node Th-1/Th-2 proportion. Biol Pharm Bull. 25:536–540. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ma XL, Meng M, Han LR, Li Z, Cao XH and

Wang CL: Immunomodulatory activity of macromolecular polysaccharide

isolated from Grifola frondosa. Chinese Journal of Natural

Medicines. 13:906–914. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Cui FJ, Li Y, Xu YY, Liu ZQ, Huang DM,

Zhang ZC and Tao WY: Induction of apoptosis in SGC-7901 cells by

polysaccharide-peptide GFPS1b from the cultured mycelia of Grifola

frondosa GF9801. Toxicol In Vitro. 21:417–427. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang CL, Meng M, Liu SB, Wang LR, Hou LH

and Cao XH: A chemically sulfated polysaccharide from Grifola

frondos induces HepG2 cell apoptosis by notch1-NF-κB pathway.

Carbohydr Polym. 95:282–287. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nakagawa S, Shiraishi T, Kihara S and

Tabuchi K: Detection of DNA strand breaks associated with apoptosis

in human brain tumors. Virchows Arch. 427:175–179. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Joselin AP, Schulze-Osthoff K and Schwerk

C: Loss of Acinus inhibits oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation but

not chromatin condensation during apoptosis. J Biol Chem.

281:12475–12484. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen R, Liu S, Piao F, Wang Z, Qi Y, Li S,

Zhang D and Shen J: 2,5-Hexanedione induced apoptosis in

mesenchymal stem cells from rat bone marrow via

mitochondria-dependent caspase-3 pathway. Ind Health. 53:222–235.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang Y, Wu Y, Luo K, Liu Y, Zhou M, Yan S,

Shi H and Cai Y: The protective effects of selenium on

cadmium-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis via mitochondria

pathway in mice kidney. Food Chem Toxicol. 58:61–67. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hu Q, Wu D, Chen W, Yan Z and Shi Y:

Proteolytic processing of the caspase-9 zymogen is required for

apoptosome-mediated activation of caspase-9. J Biol Chem.

288:15142–15147. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lin YL, Wang GJ, Huang CL, Lee YC, Liao

WC, Lai WL, Lin YJ and Huang NK: Ligusticum chuanxiong as a

potential neuroprotectant for preventing serum deprivation-induced

apoptosis in rat pheochromocytoma cells: functional roles of

mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Ethnopharmacol. 122:417–423.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lou H, Fan P, Perez RG and Lou H:

Neuroprotective effects of linarin through activation of the

PI3K/Akt pathway in amyloid-β-induced neuronal cell death. Bioorg

Med Chem. 19:4021–4027. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Brown DI and Griendling KK: Regulation of

signal transduction by reactive oxygen species in the

cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 116:531–549. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hisatomi T, Ishibashi T, Miller JW and

Kroemer G: Pharmacological inhibition of mitochondrial membrane

permeabilization for neuroprotection. Exp Neurol. 218:347–352.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Maurer U, Preiss F, Brauns-Schubert P,

Schlicher L and Charvet C: GSK-3 - at the crossroads of cell death

and survival. J Cell Sci. 127:1369–1378. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sweatt JD: The neuronal MAP kinase

cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving

synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem. 76:1–10. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang D, Wong HK, Feng YB and Zhang ZJ:

18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid induces apoptosis in pituitary adenoma

cells via ROS/MAPKs-mediated pathway. J Neurooncol. 116:221–230.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Chan SL and Yu VC: Proteins of the bcl-2

family in apoptosis signalling: from mechanistic insights to

therapeutic opportunities. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 31:119–128.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bernardi P and Rasola A: Calcium and cell

death: the mitochondrial connection. Subcell Biochem. 45:481–506.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Kepp O, Séror C,

Hangen E, Perfettini JL, Modjtahedi N and Kroemer G: Methods to

dissect mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in the course of

apoptosis. Methods Enzymol. 442:355–374. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hippe D, Gais A, Gross U and Lüder CG:

Modulation of caspase activation by Toxoplasma gondii. Methods Mol

Biol. 470:275–288. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Schug ZT, Gonzalvez F, Houtkooper RH, Vaz

FM and Gottlieb E: BID is cleaved by caspase-8 within a native

complex on the mitochondrial membrane. Cell Death Differ.

18:538–548. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

29

|

Lee KH, Feig C, Tchikov V, Schickel R,

Hallas C, Schütze S, Peter ME and Chan AC: The role of receptor

internalization in CD95 signaling. EMBO J. 25:1009–1023. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Espín R, Roca FJ, Candel S, Sepulcre MP,

González-Rosa JM, Alcaraz-Pérez F, Meseguer J, Cayuela ML, Mercader

N and Mulero V: TNF receptors regulate vascular homeostasis in

zebrafish through a caspase-8, caspase-2 and P53 apoptotic program

that bypasses caspase-3. Dis Model Mech. 6:383–396. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

Porter AG and Jänicke RU: Emerging roles

of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 6:99–104. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang L, Zhang Y and Xing D: LPLI inhibits

apoptosis upstream of Bax translocation via a

GSK-3beta-inactivation mechanism. J Cell Physiol. 224:218–228.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Petit-Paitel A, Brau F, Cazareth J and

Chabry J: Involvment of cytosolic and mitochondrial GSK-3beta in

mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal cell death of

MPTP/MPP-treated neurons. PLoS One. 4:e54912009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Krajarng A, Nakamura Y, Suksamrarn S and

Watanapokasin R: α-Mangostin induces apoptosis in human

chondrosarcoma cells through downregulation of ERK/JNK and Akt

signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 59:5746–5754. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tada K, Kawahara K, Matsushita S,

Hashiguchi T, Maruyama I and Kanekura T: MK615, a Prunus mume Steb.

Et Zucc ('Ume') extract, attenuates the growth of A375 melanoma

cells by inhibiting the ERK1/2-Id-1 pathway. Phytother Res.

26:833–838. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhao Y, Shen S, Guo J, Chen H, Greenblatt

DY, Kleeff J, Liao Q, Chen G, Friess H and Leung PS:

Mitogen-activated protein kinases and chemoresistance in pancreatic

cancer cells. J Surg Res. 136:325–335. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Balmanno K and Cook SJ: Tumour cell

survival signalling by the ERK1/2 pathway. Cell Death Differ.

16:368–377. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Lim JY, Park SI, Oh JH, Kim SM, Jeong CH,

Jun JA, Lee KS, Oh W, Lee JK and Jeun SS: Brain-derived

neurotrophic factor stimulates the neural differentiation of human

umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells and survival of

differentiated cells through MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt-dependent

signaling pathways. J Neurosci Res. 86:2168–2178. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ma R, Xiong N, Huang C, Tang Q, Hu B,

Xiang J and Li G: Erythropoietin protects PC12 cells from

beta-amyloid(25–35)-induced apoptosis via PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway. Neuropharmacology. 56:1027–1034. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|