Introduction

Sarcomas, including soft tissue sarcomas (STS) and

osteosarcomas, are heterogeneous tumours that arise from

transformed cells of mesenchymal origin, including malignant

tumours made of bone, cartilage, fat, muscle, vascular or

hematopoietic tissues. Patients with a localized sarcoma have a 83%

chance for a 5-year survival, whereas those sarcomas with lymph

node involvement have a reduced prognosis of 54% and the worst

prognosis is 16% for sarcomas that have spread to distant parts of

the body (1). This reflects the

ineffectiveness of current therapy and the importance for the

development of better treatment options to improve outcomes.

The human epidermal growth factor receptor

(EGFR/HER) family of receptor tyrosine kinases, including

EGFR/HER1/ErbB1, HER2/ErbB2, HER3/ErbB3 and HER4/ErbB4, regulates

proliferation, survival, adhesion, and the migration and invasion

of malignant cells (2,3). Following ligand binding to the

extra-celluar domain of HER family members, subsequent signalling

cascades affect gene transcription through three downstream

pathways: ras/raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK),

phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT and Janus kinase/signal

transducer and activator of transcription (JAK)/signal transducer

and activator of transcription (STAT) (4). Clinical studies have indicated that

the hyperactivation of the HER family is associated with more

aggressive diseases and poor clinical outcomes, so the HER family

has been intensively pursued as therapeutic targets (5 and refs.

therein).

We have previously reported that, in a cohort of 46

consecutive patients with STS, 78% demonstrated a positive

expression of EGFR (6). This

finding is consistent with other series in STS with a mean of 68%

(range 60–77%) (7–11). In a large Japanese study, EGFR

expression was found to be significantly associated with the

histological grade, but was not an independent prognostic factor

for survival (7). Our recent

studies demonstrated that EGFR and downstream signal transducers

were highly expressed and activated in STS cell lines (12), and showed that phosphorylated

(p-)EGFR p-EGFR) and p-Erk are independent prognostic factors for

overall and/or cancer-specific survival in 87 STS samples (13). However, the specific EGFR

inhibitor, gefitinib, was ineffective in terms of preclinical

anti-proliferation, despite the inhibition of pEGFR and signalling

transducers in the EGFR downstream PI3K/AKT and ras/raf/Erk MAPK

pathways (12). Consistently, a

phase II clinical trial demonstrated that single agent gefitinib

was unsatisfactory with low response rates of 21 and 6% at 4 and 6

months, respectively and short disease control in advanced synovial

sarcomas (14). All the above data

suggest that novel approaches targeting this pathway are required

in sarcoma.

Our previous study on gefitinib in sarcoma cell

lines identified the STAT3 escape pathway as a potential resistance

mechanism, due to the increased/unchanged ratio of pSTAT3/pSTAT1

from the JAK/STAT pathway (12).

HER2 overexpression as an upstream regulator has been demonstrated

to activate STAT3 and induce breast cancer growth (15,16).

In addition, HER2 also acts as a transcriptional co-activator of

STAT3 and leads to cyclin D1 promoter activation to enhance tumour

proliferation (17). Furthermore,

blocking HER2 can induce apoptosis (18). These studies provide a rationale

that HER2-induced STAT3 activation may be an escape pathway to

EGFR-specific inhibition and suggest that a panHER inhibitor

blocking both EGFR and HER2 may enhance the therapeutic effect.

Dacomitinib, a panHER inhibitor, has been shown to

exert an irreversible inhibitory effect on the tyrosine kinase

activation of human EGFR/HER1, HER2 and HER4, and is active in both

EGFR-sensitive and EGFR-resistant preclinical models (19–23).

Following initial phase I studies (20,24,25),

in subsequent phase II trials, it was shown to be well-tolerated

and showed encouraging activity (25–27).

In two phase II studies as a first-line therapy, dacomitinib

demonstrated encouraging clinical activity in patients with

recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and

neck (SCCHN) and with clinically or molecularly selected advanced

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (28–30).

Although a randomised phase II trial demonstrated a significant

improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) (31), in two double-blind randomised phase

III trials in patients pretreated with NSCLC, dacomitinib did not

improve PFS/overall survival (OS) compared with the placebo or

erlotinib in an unselected patient population (32,33).

However, a pooled subset analyses demonstrated that dacomitinib

exhibited favourable trends in PFS for the EGFR activation

mutation patient subgroup (34).

Accordingly, dacomitinib is currently in a phase III study of

first-line dacomitinib versus gefitinib in patients with advanced

NSCLC harbouring activating EGFR mutations. Of note, in a

recent interim analysis of the 452 patients in this study,

dacomitinib treatment extended PFS and the duration of response

versus gefitinib (35).

Considering the potential advantages of irreversible

panHER inhibitors over their reversible counterparts, as well as

our previous findings (12) that

sarcoma cells exhibit resistance to gefitinib treatment through the

STAT3 escape pathway, in this study, the panHER inhibitor,

dacomitinib, was examined in sarcoma cell lines. We hypothesized

that the use of dacomitinib would have the potential to increase

the effectiveness of EGFR/HER1-targeted therapy in sarcomas by i)

downregulating STAT3 via the inhibition of HER2 favouring an

increased drive to apoptsis; ii) blocking EGFR/HER1 downstream

ras/raf/MAPK and PI3K/AKT survival signals to further induce

apoptosis; and iii) blocking other HER family member signalling to

overcome resistance to single EGFR/HER1 inhibition. To date, no

panHER inhibitor has been tested in sarcomas. The principal aim of

this study was to investigate the in vitro antitumour effect

and mechanisms of action of dacomitinib mono- and combination

therapy in a panel of 13 human STS and osteosarcoma cell lines.

Materials and methods

Drugs and cell lines

The panHER inhibitor, dacomitinib (PF299804), was

kindly provided by Pfizer USA (New York, NY, USA). The STAT3

inhibitor, S3I-201 (NSC74859), and the EGFR inhibitor, gefitinib,

were purchased from Selleckchem (Scoresby, VIC, Australia) and

Euroasian chemicals (Mumbai, India), respectively. The human

sarcoma cell lines [SW872 (liposarcoma), HT1080 (fibrosarcoma),

SW684 (fibrosarcoma), GCT (undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma),

SW982 (synovial sarcoma), A431 (epidermoid carcinoma), SJSA

(osteosarcoma), U2-OS (osteosarcoma), MG63 (osteosarcoma) and

Saos-2 (osteosarcoma)] were purchased from the American Type

Culture Collection (ATTC, Manassas, VA, USA). PC9 (lung

adenocarcinoma) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Castle Hill, NSW,

Australia). The other cell lines [778 (fibrosarcoma), 449B

(liposarcoma; also known as 93T449; STR profile available on ATCC,

cat. no. ATCC CRL-3043), HOS (osteosarcoma) and 143B

(osteosarcoma)] were kindly provided by Professor David Thomas

(Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) and Dr

Florence Pedeatour (Nice University Hospital, Nice, France). The

cell lines were all tested as mycoplasma-free, and were subjected

to identification tests using short tandem repeat (STR) profiling

by CellBank Australia (Westmead, NSW, Australia) and shown to be

consistent with their stated cell lineage.

Cell culture and cell proliferation

assay

All cells were maintained in Rosewell Park Memorial

Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium, supplemented with 10%

heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine and

antibiotics (50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin)

at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 and 95% atmosphere. Cell

culture reagents were purchased from Gibco (Melbourne, VIC,

Australia). Cells were grown as monolayer cultures in

75-cm2 flasks. Once 80–90% confluent, the cells were

detached with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA/PBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA,

USA) and then cultured in a new flask for use in subsequent

experiments. Cell proliferation assay was carried by crystal violet

colorilmetric assay, as previously described (36). Briefly, 24 h after the cells were

seeded, they were treated with the vehicle [dimethyl sulfoxide

(DMSO), purchased from Amresco (Solon, OH, USA)] or drugs

[including monotherapy with gefitinib, S3I-201, and dacomitinib, as

well as combination therapy (refer to the Results section for the

details of specific mono- or combination treatments, doses and

treatment durations)]. At least duplicate experiments with each

treatment group containing triplicate wells were carried out. After

the required time period, the cells were washed with Dulbecco’s

phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), stained with 0.5% crystal violet

(Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated with elution solution (0.1 M sodium

citrate and 100% ethanol), followed by light absorbance at 540 nm

on a plate reader (Tecan; Grodig, Salzburg, Austria).

Clonogenic survival assay for adherent

sarcoma cells

After 24 h of seeding, the cells were treated with

the vehicle (DMSO) or drugs (200 nM of dacomitinib, 10 μM of

S3I-201 or 200 nM of dacomitinib plus 10 μM of S3I-201) and

incubated at 37°C. The drugs were present in the medium throughout

the whole incubation period. Once colony-formation (1 colony ≥50

cells, 6–8 days) was observed in the control wells, all related

wells were washed and stained with crystal violet.

Anchorage-independent growth assay

(anti-anoikis assay) by soft agar colony formation assay

The bottom gel was created by mixing 1% agarose with

equivalent volume of 2X RPMI. Logarithmically growing cells were

harvested and suspended in medium containing 0.35% soft agar. The

cells were treated with the vehicle or the drugs in quadruplicate.

Plates were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator for 1–2

weeks until colonies were formed. Subsequently, 10% AlamarBlue

(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was added to each well and

incubated for 4–20 h. The results were evaluated using a

fluorescence microplate reader SpectrMax M3 (Molecular Devices, San

Jose, CA, USA) with an excitation wavelength of 540–570 nm and an

emission wavelength of 580–610 nm.

Western blot analysis

The vehicle-treated and drug-treated cells were

harvested, and total proteins were extracted and measured using

western blot with β-actin as an internal protein loading control,

with our standard procedures (37). Briefly, cells were starved

overnight in RPMI-1640 medium containing 1% FBS and then treated

with the vehicle (DMSO) or drugs (200 nM of dacomitinib and/or 20

μM of S3I-201 for 24 h). The cells were then harvested

following 15 min of incubation with or without 100 ng/ml EGF

stimulation, and total proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer

(both from Sigma-Aldrich) with 1% Protease and Phosphatase

inhibitor cocktails (Merck, Bayswater, VIC, Australia). Protein

concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (Thermofisher,

Scoresby, VIC, Australia), according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. Subsequently, 50 μg proteins per lane were

separated by 4–20% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose

membranes (Bio-Rad, Gladesville, NSW, Australia), which were

blocked with 5% skim milk powder in TBS with 01% Tween-20 (TBST)

for 1 h at room temperature, and then probed with primary

antibodies overnight at 4°C. The detection of β-actin was used to

ensure equal loading and proper transfer of the protein.

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were detected by

chemiluminescence agent Supersignal Western Dura Extended Duration

(Thermofisher). Membranes were imaged by ImageQuant LAS4000 (GE

Healthcare; Silverwater, NSW, Australia). Densitometric analysis

was performed by ImageQuant TL Software (GE Healthcare) and

presented as ratios of protein expression normalized to relevant

β-actin loading control. All antibodies (STAT antibody kit #9939,

p-STAT antibody kit #9914, HER family antibody kit #8339,

PhosphoPlus AKT activation kit #9280, MAPK family antibody kit

#9926, p-MAPK family antibody kit #9910 and β-actin #4970) were

purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Arundel, QLD, Australia)

and diluted as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Growth inhibition data were calculated using

GraphPad Prism software, and IC50 curves were fitted

using a non-linear regression model with a sigmoidal dose-response.

Mean percentage growths in different treatment groups from at least

duplicate experiments with triplicate samples against controls were

analysed using ANOVA first. Significant differences obtained from

ANOVA were further analysed by a post-hoc Bonferroni test.

Two-tailed P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate

statistically significant differences.

Results

Positive expression of HER1 and HER2 in

sarcoma cell lines

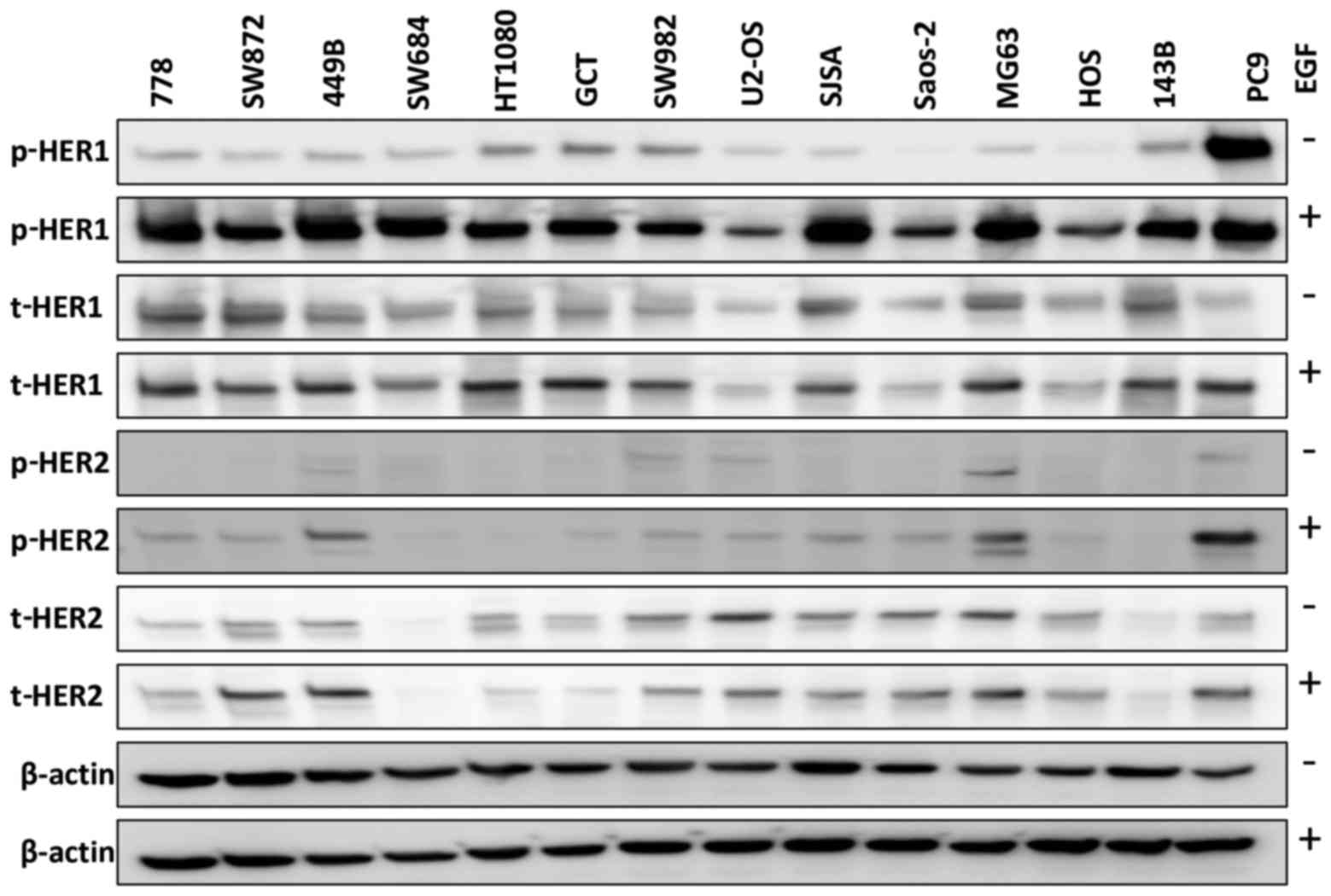

We first examined HER1 expression in 13 sarcoma cell

lines, using the PC9 cells as a positive control [which have been

reported to express abnormally high levels of HER1 (38)]. The sarcoma cell lines expressed

total HER1 (t-HER1) at a similar or higher level to that in the PC9

cells (Fig. 1) in the absence of

ligand EGF stimulation. Phosphorylated HER1 (p-HER1) was

undetectable in the Saos-2 and HOS cells, and was weakly expressed

in the other sarcoma cell lines in the absence of EGF, while the

PC9 cells exhibited a strong p-HER1 expression. We also found that

EGF stimulation (closely mimicking the in vivo setting)

induced p-HER1 expression in all 13 sarcoma cell lines, with the

cells expressing lower (U2-OS, Saos-2 and HOS) or similar levels of

p-HER1 compared with the PC9 cells. Similarly, with ligand EGF

stimulation, 10/13 cell lines exhibited HER2 phosphorylation. In

total, 6/7 STS (86%) and 5/6 osteosarcoma (83%) cell lines

expressed t-HER2 in the absence/presence of EGF.

Inhibition of the phosphorylation of HER

family receptors and signalling factors in PI3K/AKT and

ras/raf/MAPK pathways by dacomitinib monotherapy

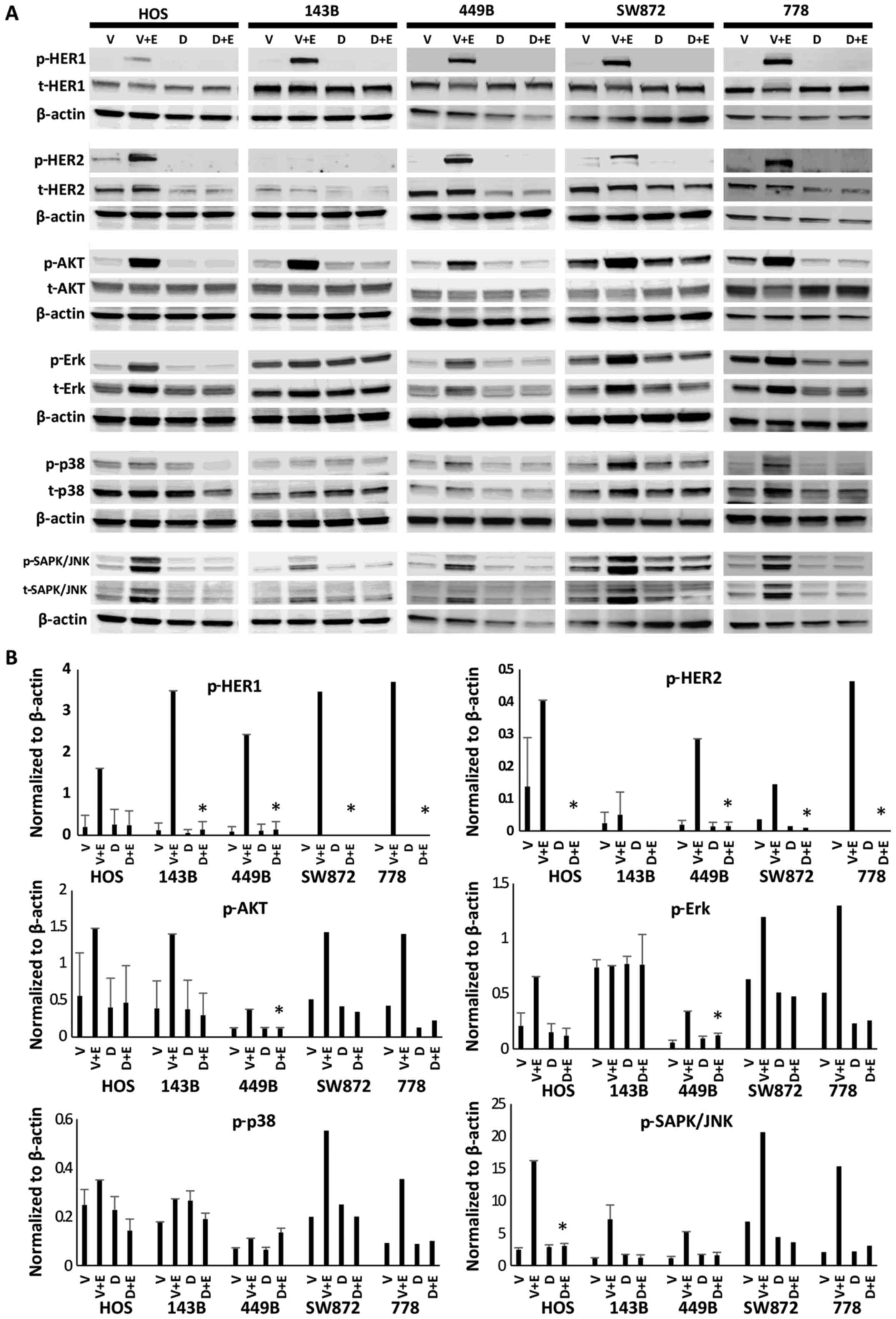

Five sarcoma cell lines (3 STS and 2 osteosarcoma)

were treated for 24 h with dacomitinib (PF299804) at its clinically

achievable total plasma concentration (200 nM) (20). As shown in Fig. 2, dacomitinib markedly blocked

EGF-induced p-HER1 expression in all 5 sarcoma cell lines, as well

as that of p-HER2 in 4/5. In addition, dacomitinib decreased the

activation of AKT and SAPK/JNK to baseline levels in all 5 sarcoma

cell lines, and downregulated the the levels of p-Erk and p-p38

MAPK in 4/5 sarcoma cell lines, apart from p-Erk in the 143B cells

and p-p38 in the 449B cells (Fig.

2).

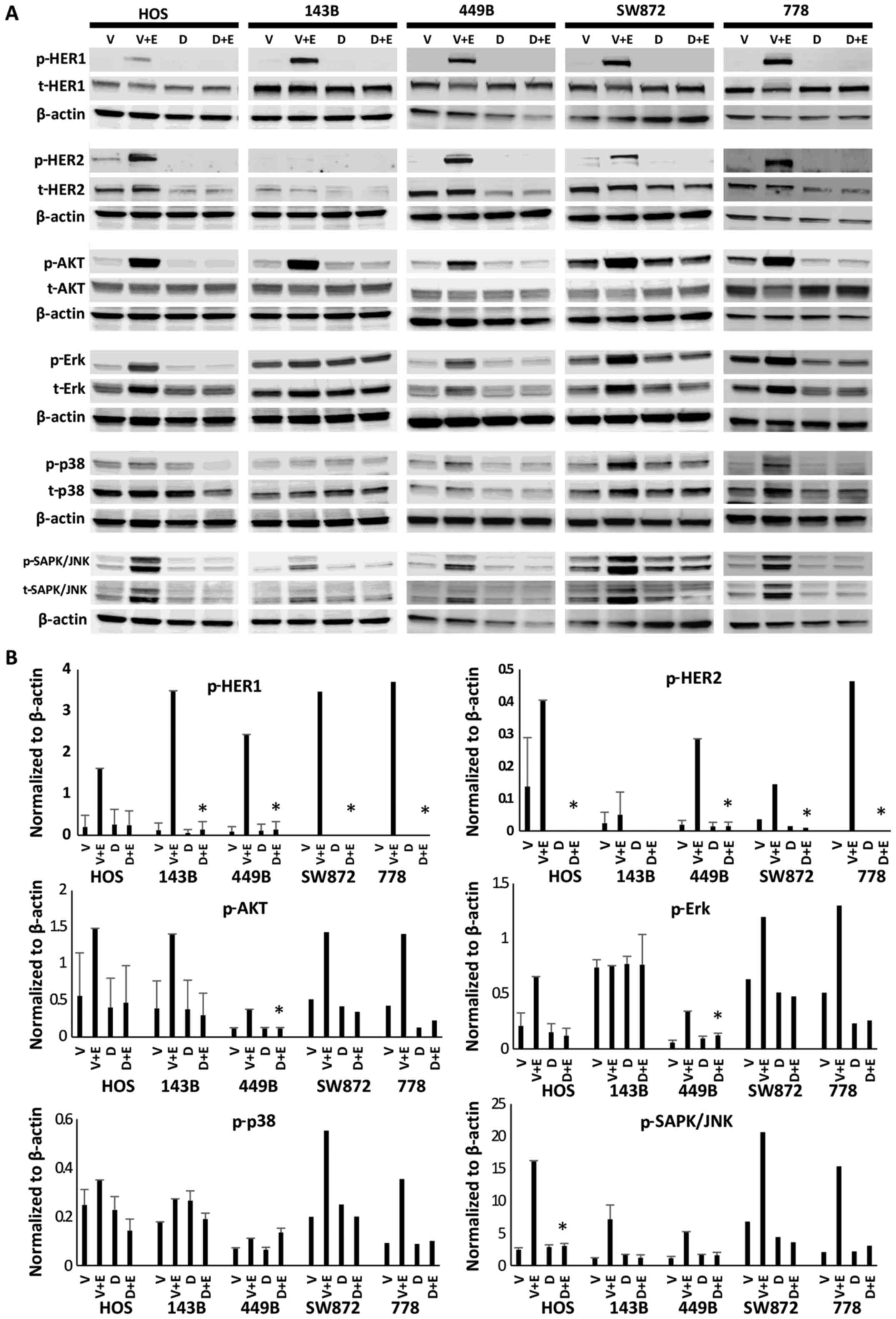

| Figure 2Dacomitinib (PF299804) decreased the

phosphorylation (activity) of the HER family receptors (HER1 and

HER2), as well as signalling factors in the PI3K/AKT and

ras/raf/MAPK downstream pathways (AKT, Erk, p38 MAPK and SAPK/JNK).

A panel of 5 sarcoma cell lines (HOS, 143B, 449B, SW872 and 778)

were treated with 200 nM of dacomitinib for 24 h, followed by

incubation with or without EGF for 15 min, and the the extracted

proteins were then immunoblotted with the indicated

phosphor-specific antibodies. Membranes used for analysis of

phosphorylated proteins were stripped and reblotted with the

respective total antibodies. The expression of β-actin was analysed

from the same cell lines as a loading control. V, vehicle control;

V+E, vehicle control plus EGF stimulation; D, 200 nM dacomitinib

treatment; D+E, 200 nM dacomitinib treatment plus EGF stimulation.

(A) Representative western blot images. (B) Expression levels of

the indicated proteins were quantified by densitometry and

normalized to β-actin loading control. P-values (D+E vs. V+E)

<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

*P<0.05. |

Growth inhibitory effects of dacomitinib

monotherapy on sarcoma cell lines

Following 72 h of treatment with 0.25–15 μM

dacomitinib, the anti-proliferative ability was evaluated. The

IC50 values are summarized in Table I. At the early time point (72 h of

treatment), all the cell lines exhibited a greater sensitivity to

dacomitinib [IC50 values: 1–5 μM for dacomitinib

versus 14–30 μM for gefitinib in our previous study on

gefitinib (12)]. However, the

IC50 values of dacomitinib in the sarcoma cell lines

were still 1,000-fold higher than those in the sensitive control

cell line, PC9 (1 nM). Extending the treatment window for longer

time period of up to 7 days, we found that all the cell lines

exhibited further growth inhibitory effects. The IC50

values for the 778, 449B, Saos-2 and SW684 cells were 3- to 5-fold

lower than those on day 3. In particular, the IC50

values for 6 sarcoma cell lines were scaled down to <1

μM.

| Table IIC50 values of dacomitinib

in 13 sarcoma cell lines. |

Table I

IC50 values of dacomitinib

in 13 sarcoma cell lines.

| Anti-proliferation

| IC50 of

anti-colony formation (μM) |

|---|

| IC50

value on day 3 (μM) | IC50

value on day 7 (μM) |

|---|

| 449B | 4.4±0.8 | 1.3±0.3 | 0.677±0.057 |

| 778 | 3.1±0.9 | 0.9±0.2 | 1.326±0.032 |

| GCT | 2.2±0.1 | 1.3±0.1 | 1.142±0.027 |

| HT1080 | 2.2±0.5 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.781±0.058 |

| SW684 | 5.6±1.3 | 1.1±0.2 | No colonies

formed |

| SW872 | 3.7±0.6 | 1.6±0.3 | 0.875±0.089 |

| SW982 | 2.0±0.3 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.163±0.055 |

| SJSA | 3.9±1.3 |

1.5±0 | No colonies

formed |

| U2-OS | 3.7±1.5 |

0.5±0 | 0.278±0.083 |

| 143B | 4.6±0.1 | 2.4±0.1 | 0.184 |

| HOS | 3.6±1.0 | 1.3±0.5 | 0.455±0.033 |

| MG63 | 2.3±0.6 |

1.0±0 | No colonies

formed |

| Saos-2 | 1.9±0.3 | 0.6±0.1 | No colonies

formed |

| PC-9 (serving as

sensitive control) | 0.001 | – | – |

| A431 (serving as

sensitive control) | – | – | 0.044 |

In addition, clonogenic survival assay was also

performed to determine the long-term effects of dacomitinib on the

sarcoma cell lines. Dacomitinib at the concentration of <1.4

μM suppressed colony formation by 50% in the sarcoma cell

lines, with IC50 values of 0.163 and 0.184 μM for

the SW982 and 143B cells, respectively, which were higher than

those of the sensitive control cell line, A431 (IC50,

0.044 μM), treated with dacomitinib (Table I).

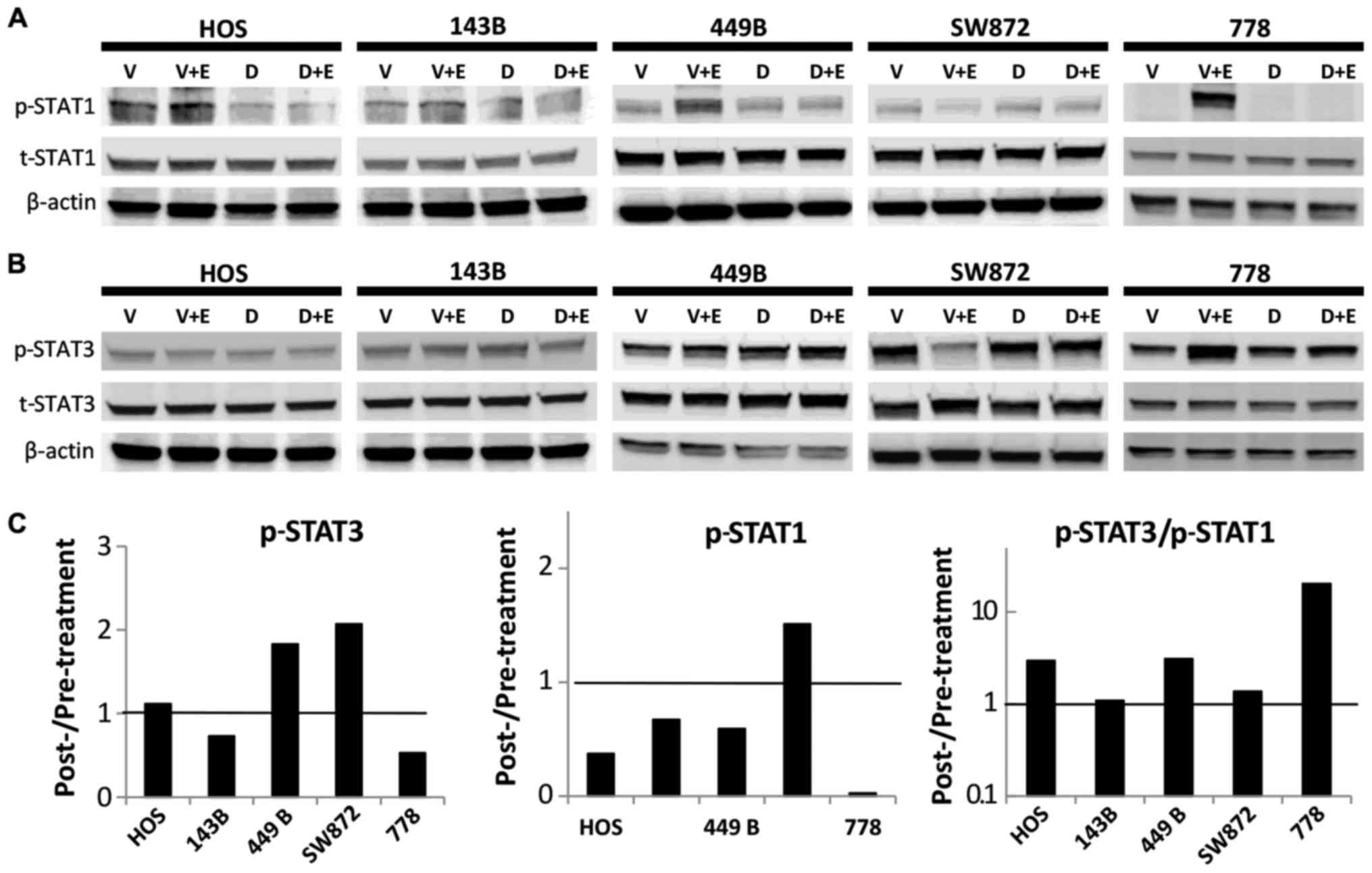

The STAT3 escape pathway and the

resistance of dacomitinib monotherapy in sarcoma

Although dacomitinib markedly inactivated HER family

members and downstream ras/raf/MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, it

failed to supress sarcoma cell growth and colony formation at

reasonable IC50 values, compared with the sensitive

control. The increased or unaltered ratio of p-STAT3/p-STAT1 was

found to be associated with the STAT3 escape pathway in our

previous study on the EGFR inhibitor, gefitinib, in sarcoma cell

lines (12). In the present study,

we found that dacomitinib inhibited p-STAT1 expression in 4/5

sarcoma cell lines by 97, 62, 41 and 33 in the 778, HOS, 449B and

143B cells, respectively, compared with the corresponding vehicle

control in the presence of EGF stimulation (Fig. 3A). However, the effects of

dacomitinib on p-STAT3 expression were highly variable: We observed

a decreased p-STAT3 expression in the 143B cells (27%) and 778

cells (47%); however, p-STAT3 expression was unaltered in the HOS

cells and it increased in the 449B cells (1.8-fold) and SW872

(2.1-fold) (Fig. 3B). The ratio of

p-STAT3/p-STAT1 was increased in 3/5 cell lines (HOS, 449B and 778

cells) and unaltered in the 143B and SW872 cells (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the STAT3

relative abundance and activation likely plays an important role in

sarcoma growth, maintenance and resistance mechanisms.

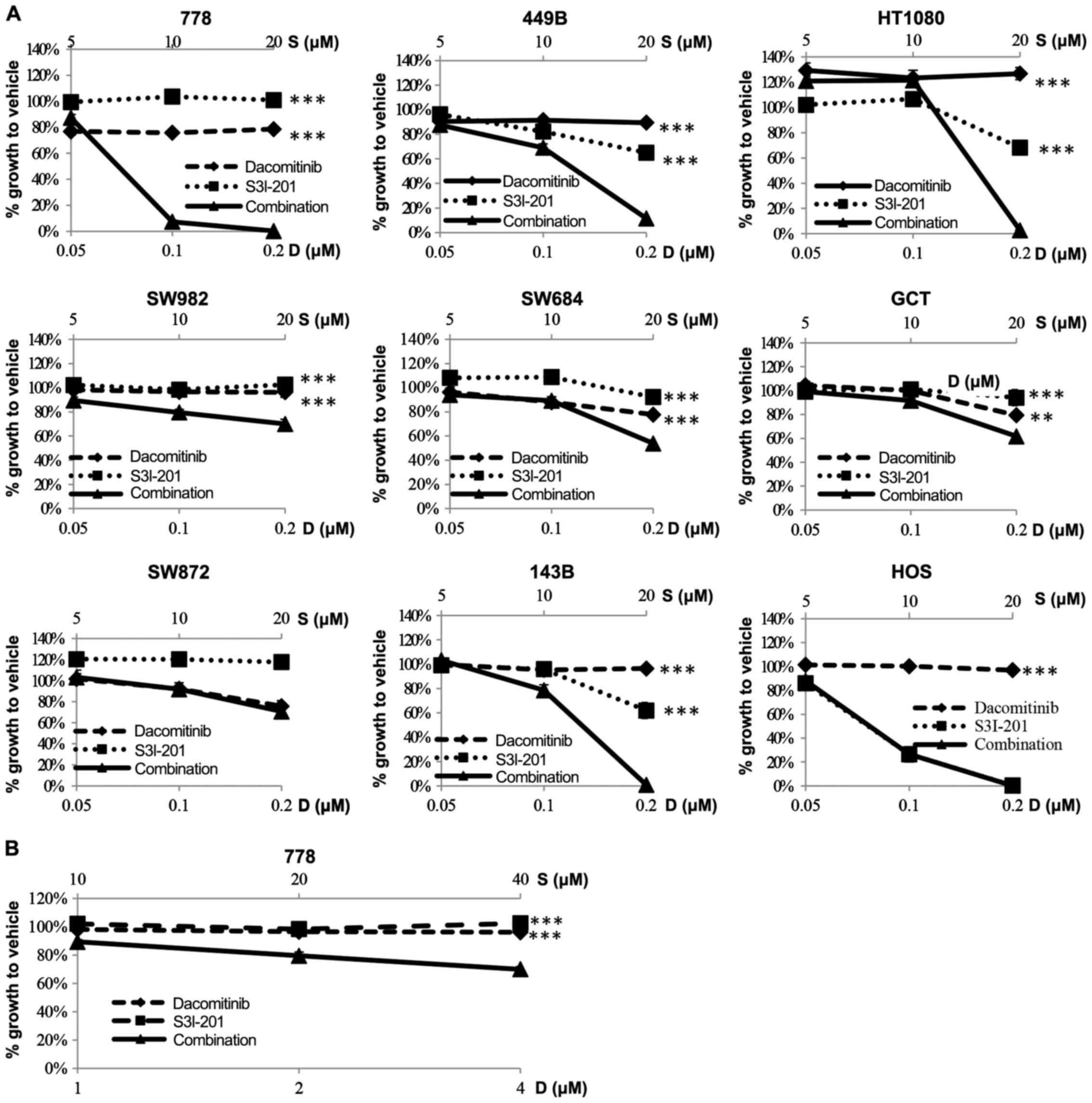

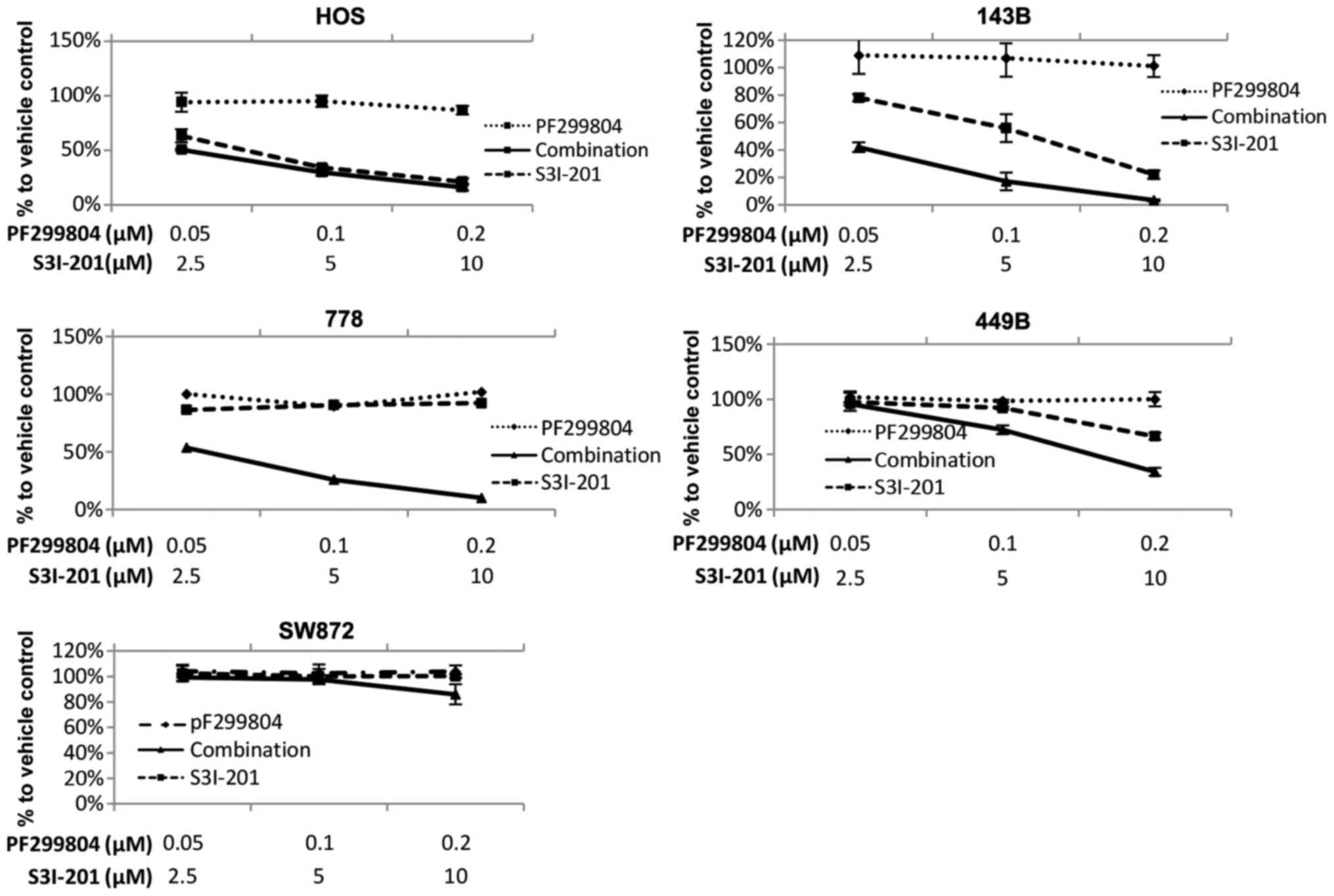

Enhancement of the sensitivity of sarcoma

cells to dacomitinib by the STAT3 inhibitor, S3I-201

A panel of 7 STS and 2 osteosarcoma (HOS and 143B)

cell lines were treated with the vehicle, dacomitinib, or S3I-201,

or a combination of dacomitinib and S3I-201 at 3 concentrations

(lower than the clinically achievable total plasma concentration

200 nM) in the constant ratio (dose ratio of dacomitinib to S3I-201

= 1:100). At 7 days post-administration, in 7/9 cell lines,

combination therapy achieved significantly enhanced

anti-proliferative effects (Fig.

4A). The HOS cells, which were the most sensitive (almost 100%)

to S3I-201 monotherapy, did not exhibit any further growth

inhibition. We also examined combination therapy in the

S3I-201-resistant SW872 cells (36) and found that these cells did not

undergo any further enhancement of the growth inhibitory effects.

Dacomitinib is ~98% bound to plasma proteins in human plasma, as

measured by equilibrium dialysis (kindly suggested by Dr Scott

Weinrich, Director of Early Clinical Development, Pfizer USA). This

indicates that only 2% constitutes the ‘free’ drug in the

circulation of patients; therefore, the 200 nM total plasma

concentration becomes 4 nM ‘free’ drug. Considering that it should

be the ‘free’ drug concentration at the site of action that exerts

the biological activity (39), we

aimed to emulate clinical exposure in vitro by the addition

of up to 4 nM dacomitinib to the most sensitive cell line, 778.

This achieved a significantly enhanced anti-proliferative effect

(combination versus dacomitinib: P=0.003; combination versus

S3I-201: P=0.0002) (Fig. 4B).

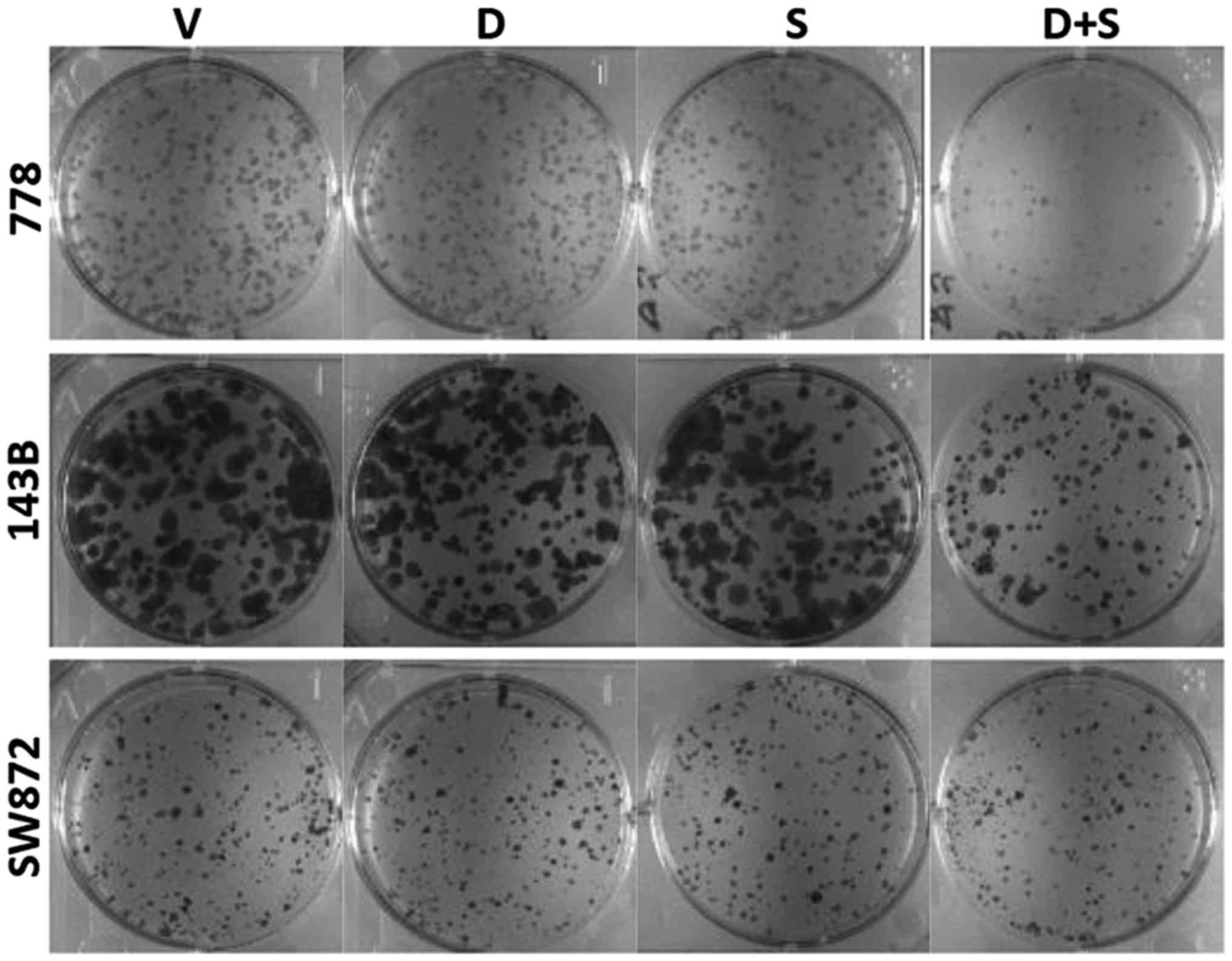

In addition, clonogenic assay was performed on the

778, 143B and SW872 cells, representing a sensitive STS cell line,

a sensitive osteosarcoma cell line and a resistant cell line,

respectively, to further examine the cell responses to the

combination therapy. Consistently, the 778 and 143B cells exhibited

an enhanced inhibition of their colony-forming ability (Fig. 5), whereas the SW872 cells were

still resistant to both monotherapies and combination therapy.

Enhancement of anoikis by dacomitinib and

S3I-201 in sarcoma cell lines

Anchorage-independent growth (the ability to evade

anoikis) using the 3D soft agar colony formation assay was then

applied to assess cancer metastatic (anoikis-resistance) ability in

sarcoma cell lines following treatment with dacomitinib and S3I-201

monotherapy or their combination. The results shown in Fig. 6 confirmed that combination therapy

markedly enhanced anoikis (apoptosis occurred when the cells

detached to the extracellular matrix) in the 778, 449B and 143B

cells. However, this enhancement was not observed in the HOS cells,

in which the combination therapy did not further enhance anoikis

compared to treatment with S3I-201 alone treatment, no in the SW872

cells, in which all treatments (both drug mono- and

combination-therapies) did not restore anoikis.

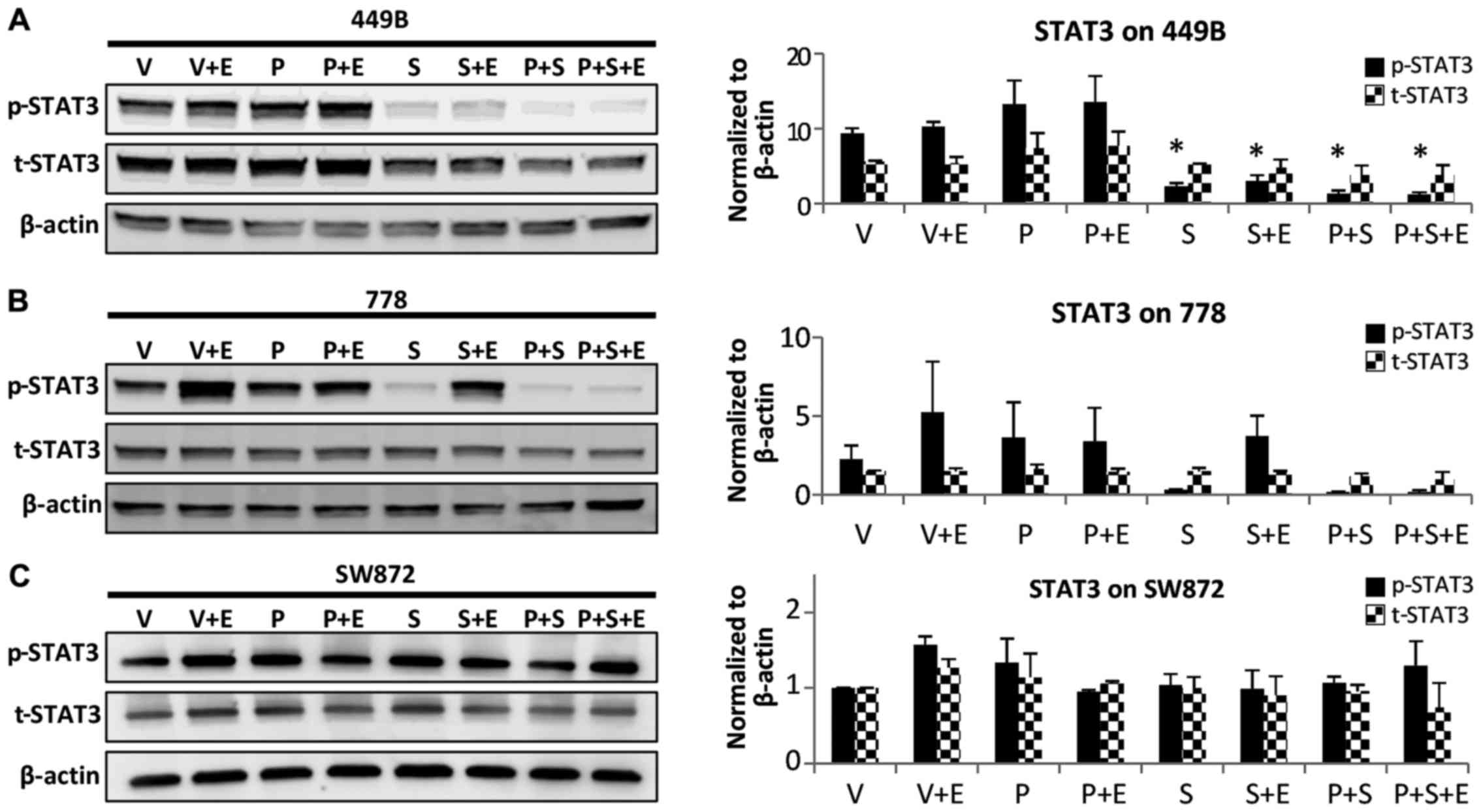

Contribution of the downregulation of

STAT3 phosphorylation to the enhanced effects observed with

combination therapy

Using different methods (crystal violet

colorimetric, clonogenic and anoikis assays), we demonstrated that

combination treatment with S3I-201 enhanced the sensitivity to

dacomitinib in the sarcoma cell lines. As a preliminary

investigation of the potential mechanisms of action behind the

enhancement, western blot analysis was performed on 3 sarcoma cell

lines, representing a strong enhancement (778 cells), moderate

enhancement (449B cells) and resistance (SW872 cells). In the 778

cells, treatment with S3I-201 alone downregulated constitutive

STAT3 phosphorylation; however, the blockage of p-STAT3 was

partially recovered by EGF stimulation. As expected, the

combination therapy induced almost complete (94%) inhibition of

STAT3 phosphorylation, even with EGF stimulation (Fig. 7). In the 449B cells, the addition

of 200 nM dacomitinib also led to the further blockage of STAT3

phosphorylation compared to treatment with S3I-201 alone (from 77

to 90%). However, in the SW872 cells, which exhibited resistance to

both monotherapies and combination treatment in our

anti-proliferation assay, combination therapy did not effectively

inhibit STAT3 phosphorylation, as shown by the results of western

blot analysis (Fig. 7).

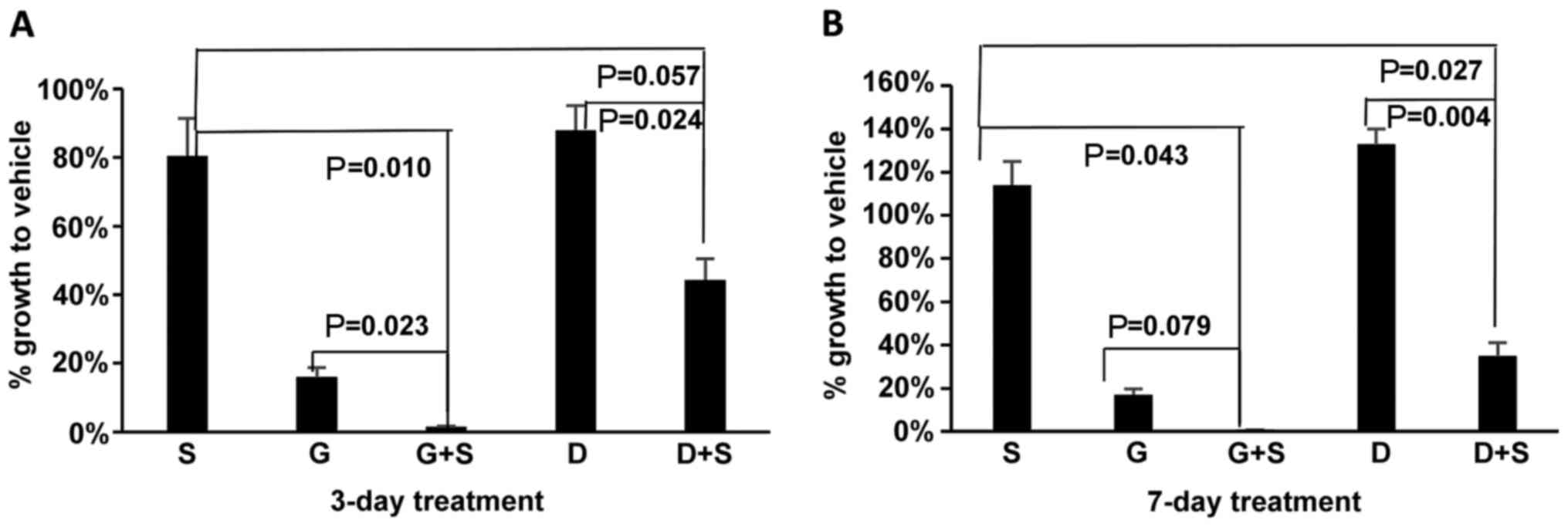

Comparison of panHER inhibition with HER1

in combination with STAT3 inhibition

Previously, we reported that the addition of the

STAT3 inhibitor, S3I-201, to the EGFR inhibitor, gefitinib,

achieved synergistic anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects

in sarcoma cell lines (12). In

this study, to compare the potential effects of concurrent

inhibition using dacomitinib-S3I-201 with previous

gefitinib-S3I-201, we examined the growth-inhibiting ability of the

combination therapies at the clinically achievable concentrations

for each drug (10 μM for gefitinib and 200 nM for

dacomitinib) at the same time (Fig.

8). After 24 h of seeding, the HT1080 cells were treated with

the vehicle (DMSO), S3I-201, gefitinib, dacomitinib, gefitinib plus

S3I-201 or dacomitinib plus S3I-201 for 3 or 7 days. In terms of

combination versus monotherapy with dacomitinib or gefitinib,

treatment with dacomitinib led to a similar P-value (0.024) as

gefitinib (0.023) after 3 days of treatment, and to an even lower

P-value (0.004) than gefitinib (0.079) after 7 days of treatment.

The combination treatment with dacomitinib and S3I-201 (56 and 65%

growth inhibition on days 3 and 7, respectively) significantly

enhanced the anti-proliferative effects compared to dacomitinib

monotherapy; however, it exerted less potent inhibitory effects

than gefitinib-S3I-201 (98 and 99% inhibition) on sarcoma cell

growth.

Discussion

In this study, we discovered that apart from

EGFR/HER1, another HER family receptor, HER2, was also

overexpressed in human sarcoma cell lines. The panHER inhibitor,

dacomitinib, successfully inhibited the activation of HER family

members (p-EGFR and p-HER2), as well as HER downstream pathway

signalling transducers (p-AKT, p-Erk, p-p38 MAPK and p-SAPK/JNK).

Despite the suppression of these pathways, the results of cell

proliferation and colony formation assay revealed that all 13

sarcoma cell lines were insensitive to dacomitinib. We demonstrated

that dacomitinib increased or did not significantly alter the ratio

of oncogene p-STAT3 versus tumour suppressor p-STAT1, indicating

that STAT3 may represent an escape pathway that correlates with the

resistance of sarcoma cell lines to dacomitinib. To conclusively

determine causation will require additional studies with siRNA

and/or transgenic mouse models in the future. This mechanism (the

STAT3 escape pathway), if further validated, may prove to be a

targe-table mechanism of resistance to EGFR blockade in

sarcoma.

Even though the overexpression of p-EGFR and its

downstream signal transducers is noted in sarcoma tissues and cell

lines and is negatively associated with sarcoma outcomes, we have

shown a limited inhibitory effect of EGFR pathway blockade using

the specific EGFR inhibitor, gefitinib, due to the relative

activation of STAT3 (12). The

observation of HER2-positive expression in sarcoma cell lines

indicated that the blockade of a single receptor of the HER family

may be compromised by signalling through other members. HER2

overexpression has been demonstrated to activate STAT3 and to act

as a transcriptional co-activator of STAT3 and contribute to tumour

initiation and growth (15–17).

The activation of HER2 signalling has been reported to be

associated with the primary resistance of metastatic colorectal

carcinoma to EGFR-targeted therapy (40). In addition, MET

amplification/overexpression has also been reported to promote

resistance to gefitinib by driving the HER3-dependent activation of

PI3K in a gefitinib-sensitive lung cancer cell line (HCC827)

(41,42). Therefore, we hypothesized that

targeting all HER family members using a panHER inhibitor may

enhance the inhibitory effects of targeted therapy in sarcoma.

Dacomitinib is a highly effective panHER inhibitor both in

vitro and in vivo in a broad range of human cancer cell

lines (21–23,43–45).

In this study, we demonstrated that dacomitinib

markedly suppressed the activation of both EGFR/HER1 and HER2, as

well as their representative downstream signalling factors in

ras/raf/MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, including p-AKT, p-Erk, p-p38

and p-SAPK/JNK. This was consistent with the findings of other

studies on breast cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

cell lines (44,45). Despite this, the anti-proliferative

effect of dacomitinib in our study indicated that all 13 sarcoma

cell lines were resistant to the drug with IC50 values

of ~1 μM, greater than that of our sensitive control lung

cancer cell line, PC9 (1 nM), which is similar to previous reports

on non-sarcoma cell lines (21,46).

The results of western blot analysis revealed that dacomitinib did

not decrease the ratio of p-STAT3/p-STAT1. Dacomitinib, despite its

additional blockade of HER2 compared with gefitinib blocking HER1

only, showed lower IC50 values, but no improvement in

biologically and potentially clinically meaningful antitumour

effects. Rather than the EGF pathway not being relevant to tumour

promotion in sarcoma, this absence of benefit appears to be a

result of failure to overcome the STAT3 escape pathway, which may

be regulated by HER-independent upstream mediators. In head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma and lung adeno-carcinomas, STAT3

constitutive activation has been reported to use an

autocrine/paracrine-activating loop through alternative pathways,

such as IL-6/gp130 (47,48). HER-independent JAK/STAT3 (such as

IL-6/JAK/STAT3) leads to the ineffectiveness of targeting HER

family pathway. STAT3 is a more downstream point of convergence in

many ligand/receptor pathways (such as growth factor and cytokine

receptors) and non-receptor tyrosine kinase pathways (such as Src)

and consequently cross-talk among these signalling pathways may

contribute to resistance to EGFR/panHER inhibitors (49).

In this study, we found that the addition of S3I-201

to dacomitinib induced significant enhancement of the

anti-proliferative effects (7/9 cell lines), further inhibited

colony formation (2/3 cell lines) and enhanced anoikis (3/5 of

sarcoma cell lines). Our preliminary STAT3 expression and

regulation analysis revealed the additional inactivation of STAT3

by the combination treatment in sensitive sarcoma cell lines. By

contrast, in the SW872 liposarcoma cell line, which exhibited

resistance to the combination therapy in the anti-proliferation

assay, STAT3 activation was not inhibited by the combination

treatment. Comparing the current dacomitinib-S3I-201 combination

with the one in our previous study (gefitinib-S3I-201) (13), we found that dacomitinib-S3I-201

did not demonstrate superior anti-proliferative activities.

Consistent with our findings, the activation of

JAK/STAT3 signalling pathway mediated by autocrine and paracrine

IL-6R has been found to be associated with the development of drug

resistance to the irreversible panHER inhibitors, dacomitinib and

afatinib in non-small cell lung cancer (50). The blockade of the IL-6R/JAK/STAT3

signalling pathway significantly enhanced the sensitivity to these

irreversible inhibitors in both in vitro and in vivo

models. Taken together, these results of STAT inhibition used to

overcome primary resistance to EGFR blockade encourage the further

exploration of this approach. Further experiments will require

optimisation through next-generation inhibitors, different drug

ratios, and the sequence of drug administration in vitro,

followed by assessing the effectiveness and safety of combination

therapy using both panHER and STAT3 inhibitors in vivo in

sarcoma animal models.

We thus conclude that neither the first-generation

reversible specific EGFR inhibitor, gefitinib, nor the

second-generation irreversible panHER inhibitor, dacomitinib, as

single agents are likely to have clinical utility in sarcoma. The

relative abundance and activation of STAT3 may be involved in the

resistance mechanism in both EGFR- and panHR-targeted therapies. To

the best of our knowledge, our results are the first to demonstrate

the significantly and highly anti-proliferative effects of the

combination of the irreversible panHER inhibitor, dacomitinib, and

the STAT3 inhibitior, S3I-201, in sarcoma cell lines. These results

provide a rationale for further in vitro and in vivo

studies inhibiting both EGFR/panHER and STAT3 in combination for

the treatment of sarcoma.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Pfizer USA (grant

no. IIR #WS1914693). XW was awarded Rainbows for Kate PhD

Scholarship from the Australasian Sarcoma Study Group.

Availability of data and materials

The analysed datasets generated during the study are

available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

XW contributed to performing the experiments, data

acquisition and analysis and manuscript drafting. JLY contributed

to Pfizer IIR grant application, project design, supervision, grant

management, statistical analysis and manuscript revision. DG and

PJC assisted in the study design and conception and revised the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sarcoma, Soft Tissue: Statistics. ASCO,

Cancer.Net Editorial Board; 2016, http://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/sarcoma-soft-tissue/statistics.

|

|

2

|

Baselga J and Arteaga CL: Critical update

and emerging trends in epidermal growth factor receptor targeting

in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 23:2445–2459. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hynes NE and Lane HA: ERBB receptors and

cancer: The complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer.

5:341–354. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wang X, Batty KM, Crowe PJ, Goldstein D

and Yang JL: The potential of panHER inhibition in cancer. Front

Oncol. 5:22015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Holbro T and Hynes NE: ErbB receptors:

Directing key signaling networks throughout life. Annu Rev

Pharmacol Toxicol. 44:195–217. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yang JL, Hannan MT, Russell PJ and Crowe

PJ: Expression of HER1/EGFR protein in human soft tissue sarcomas.

Eur J Surg Oncol. 32:466–468. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Sato O, Wada T, Kawai A, Yamaguchi U,

Makimoto A, Kokai Y, Yamashita T, Chuman H, Beppu Y, Tani Y, et al:

Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor, ERBB2 and KIT in

adult soft tissue sarcomas: A clinicopathologic study of 281 cases.

Cancer. 103:1881–1890. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Teng HW, Wang HW, Chen WM, Chao TC, Hsieh

YY, Hsih CH, Tzeng CH, Chen PC and Yen CC: Prevalence and

prognostic influence of genomic changes of EGFR pathway markers in

synovial sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 103:773–781. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Cascio MJ, O’Donnell RJ and Horvai AE:

Epithelioid sarcoma expresses epidermal growth factor receptor but

gene amplification and kinase domain mutations are rare. Mod

Pathol. 23:574–580. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Keizman D, Issakov J, Meller I, Maimon N,

Ish-Shalom M, Sher O and Merimsky O: Expression and significance of

EGFR in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. J Neurooncol.

94:383–388. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Biscuola M, Van de Vijver K, Castilla MA,

Romero-Pérez L, López-García MÁ, Díaz-Martín J, Matias-Guiu X,

Oliva E and Palacios Calvo J: Oncogene alterations in endometrial

carcinosarcomas. Hum Pathol. 44:852–859. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wang X, Goldstein D, Crowe PJ, Yang M,

Garrett K, Zeps N and Yang JL: Overcoming resistance of targeted

EGFR monotherapy by inhibition of STAT3 escape pathway in soft

tissue sarcoma. Oncotarget. 7:21496–21509. 2016.

|

|

13

|

Yang JL, Gupta RD, Goldstein D and Crowe

PJ: Significance of phosphorylated epidermal growth factor receptor

and its signal transducers in human soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Mol

Sci. 18:182017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ray-Coquard I, Le Cesne A, Whelan JS,

Schoffski P, Bui BN, Verweij J, Marreaud S, van Glabbeke M,

Hogendoorn P and Blay JY: A phase II study of gefitinib for

patients with advanced HER-1 expressing synovial sarcoma refractory

to doxorubicin-containing regimens. Oncologist. 13:467–473. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hawthorne VS, Huang WC, Neal CL, Tseng LM,

Hung MC and Yu D: ErbB2-mediated Src and signal transducer and

activator of transcription 3 activation leads to transcriptional

up-regulation of p21Cip1 and chemoresistance in breast cancer

cells. Mol Cancer Res. 7:592–600. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Proietti CJ, Rosemblit C, Beguelin W,

Rivas MA, Díaz Flaqué MC, Charreau EH, Schillaci R and Elizalde PV:

Activation of Stat3 by heregulin/ErbB-2 through the co-option of

progesterone receptor signaling drives breast cancer growth. Mol

Cell Biol. 29:1249–1265. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Béguelin W, Díaz Flaqué MC, Proietti CJ,

Cayrol F, Rivas MA, Tkach M, Rosemblit C, Tocci JM, Charreau EH,

Schillaci R, et al: Progesterone receptor induces ErbB-2 nuclear

translocation to promote breast cancer growth via a novel

transcriptional effect: ErbB-2 function as a coactivator of Stat3.

Mol Cell Biol. 30:5456–5472. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Gao L, Li F, Dong B, Zhang J, Rao Y, Cong

Y, Mao B and Chen X: Inhibition of STAT3 and ErbB2 suppresses tumor

growth, enhances radiosensitivity, and induces

mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in glioma cells. Int J Radiat

Oncol Biol Phys. 77:1223–1231. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Boyer MJ, Blackhall FH, Park K, Barrios

CH, Krzakowski MJ, Taylor I, Liang JQ, Denis LJ, O’Connell JP and

Ramalingam SS: Efficacy and safety of PF299804 versus erlotinib

(E): A glolbal, randomized phase II trial in patients (pts) with

advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after failure of

chemotherapy (CT). In: ASCO Annual Meeting 2010; J Clin Oncol;

Chicago, IL; 2010

|

|

20

|

Jänne PA, Boss DS, Camidge DR, Britten CD,

Engelman JA, Garon EB, Guo F, Wong S, Liang J, Letrent S, et al:

Phase I dose-escalation study of the pan-HER inhibitor, PF299804,

in patients with advanced malignant solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res.

17:1131–1139. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Gale C-M,

Lifshits E, Gonzales AJ, Shimamura T, Zhao F, Vincent PW, Naumov

GN, Bradner JE, et al: PF00299804, an irreversible pan-ERBB

inhibitor, is effective in lung cancer models with EGFR and ERBB2

mutations that are resistant to gefitinib. Cancer Res.

67:11924–11932. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Gonzales AJ, Hook KE, Althaus IW, Ellis

PA, Trachet E, Delaney AM, Harvey PJ, Ellis TA, Amato DM, Nelson

JM, et al: Antitumor activity and pharmacokinetic properties of

PF-00299804, a second-generation irreversible pan-erbB receptor

tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 7:1880–1889. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Nam H-J, Ching KA, Kan J, Kim HP, Han SW,

Im SA, Kim TY, Christensen JG, Oh DY and Bang YJ: Evaluation of the

antitumor effects and mechanisms of PF00299804, a pan-HER

inhibitor, alone or in combination with chemotherapy or targeted

agents in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 11:439–451. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Takahashi T, Boku N, Murakami H, Naito T,

Tsuya A, Nakamura Y, Ono A, Machida N, Yamazaki K, Watanabe J, et

al: Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of dacomitinib (PF-00299804),

an oral irreversible, small molecule inhibitor of human epidermal

growth factor receptor-1, -2, and -4 tyrosine kinases, in Japanese

patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs.

30:2352–2363. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Park K, Cho BC, Kim DW, Ahn MJ, Lee SY,

Gernhardt D, Taylor I, Campbell AK, Zhang H, Giri N, et al: Safety

and efficacy of dacomitinib in korean patients with KRAS wild-type

advanced non-small-cell lung cancer refractory to chemotherapy and

erlotinib or gefitinib: A phase I/II trial. J Thorac Oncol.

9:1523–1531. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Reckamp KL, Giaccone G, Camidge DR,

Gadgeel SM, Khuri FR, Engelman JA, Koczywas M, Rajan A, Campbell

AK, Gernhardt D, et al: A phase 2 trial of dacomitinib

(PF-00299804), an oral, irreversible pan-HER (human epidermal

growth factor receptor) inhibitor, in patients with advanced

non-small cell lung cancer after failure of prior chemotherapy and

erlotinib. Cancer. 120:1145–1154. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Oh DY, Lee KW, Cho JY, Kang WK, Im SA, Kim

JW and Bang YJ: Phase II trial of dacomitinib in patients with

HER2-positive gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 19:1095–1103. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Abdul Razak AR, Soulières D, Laurie SA,

Hotte SJ, Singh S, Winquist E, Chia S, Le Tourneau C, Nguyen-Tan

PF, Chen EX, et al: A phase II trial of dacomitinib, an oral

pan-human EGF receptor (HER) inhibitor, as first-line treatment in

recurrent and/or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and

neck. Ann Oncol. 24:761–769. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Jänne PA, Ou SH, Kim DW, Oxnard GR,

Martins R, Kris MG, Dunphy F, Nishio M, O’Connell J, Paweletz C, et

al: Dacomitinib as first-line treatment in patients with clinically

or molecularly selected advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A

multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 15:1433–1441.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kris MG, Camidge DR, Giaccone G, Hida T,

Li BT, O’Connell J, Taylor I, Zhang H, Arcila ME, Goldberg Z, et

al: Targeting HER2 aberrations as actionable drivers in lung

cancers: Phase II trial of the pan-HER tyrosine kinase inhibitor

dacomitinib in patients with HER2-mutant or amplified tumors. Ann

Oncol. 26:1421–1427. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ramalingam SS, Blackhall F, Krzakowski M,

Barrios CH, Park K, Bover I, Seog Heo D, Rosell R, Talbot DC, Frank

R, et al: Randomized phase II study of dacomitinib (PF-00299804),

an irreversible pan-human epidermal growth factor receptor

inhibitor, versus erlotinib in patients with advanced

non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 30:3337–3344. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ellis PM, Shepherd FA, Millward M, Perrone

F, Seymour L, Liu G, Sun S, Cho BC, Morabito A, Leighl NB, et al

NCIC CTG; Australasian Lung Cancer Trials Group; NCI Naples

Clinical Trials Unit: Dacomitinib compared with placebo in

pretreated patients with advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung

cancer (NCIC CTG BR.26): A double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial.

Lancet Oncol. 15:1379–1388. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ramalingam SS, Jänne PA, Mok T, O’Byrne K,

Boyer MJ, Von Pawel J, Pluzanski A, Shtivelband M, Docampo LI,

Bennouna J, et al: Dacomitinib versus erlotinib in patients with

advanced-stage, previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer

(ARCHER 1009): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 15:1369–1378. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ramalingam SS, O’Byrne K, Boyer M, Mok T,

Jänne PA, Zhang H, Liang J, Taylor I, Sbar EI and Paz-Ares L:

Dacomitinib versus erlotinib in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced

nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Pooled subset analyses from two

randomized trials. Ann Oncol. 27:423–429. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wu YL, Cheng Y, Zhou X, Lee KH, Nakagawa

K, Niho S, Tsuji F, Linke R, Rosell R, Corral J, et al: Dacomitinib

versus gefitinib for the first-line treatment of advanced EGFR

mutation positive non-small cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1050): A

randomized, open-label phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 18:1454–1466.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Wang X, Goldstein D, Crowe PJ and Yang

J-L: S3I-201, a Novel STAT3 Inhibitor, Inhibits Growth of Human

Soft Tissue Sarcoma Cell Lines. World J Cancer Res. 1:61–68. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Wang X, Goldstein D, Crowe PJ and Yang JL:

Impact of STAT3 inhibition on survival of osteosarcoma cell lines.

Anticancer Res. 34:6537–6545. 2014.

|

|

38

|

Koizumi F, Shimoyama T, Taguchi F, Saijo N

and Nishio K: Establishment of a human non-small cell lung cancer

cell line resistant to gefitinib. Int J Cancer. 116:36–44. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Muller PY and Milton MN: The determination

and interpretation of the therapeutic index in drug development.

Nat Rev Drug Discov. 11:751–761. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ciardiello F and Normanno N: HER2

signaling and resistance to the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody

cetuximab: A further step toward personalized medicine for patients

with colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 1:472–474. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T,

Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, Lindeman N, Gale CM, Zhao X, Christensen

J, et al: MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung

cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 316:1039–1043. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, Riely G, Viale

A, Wang L, Chitale D, Motoi N, Szoke J, Broderick S, et al: MET

amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant

lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104:20932–20937. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Nam H-J, Kim H-P, Yoon Y-K, Song SH, Min

AR, Han SW, Im SA, Kim TY, Oh DY and Bang YJ: The irreversible

pan-HER inhibitor PF00299804 alone or combined with gemcitabine has

an antitumor effect in biliary tract cancer cell lines. Invest New

Drugs. 30:2148–2160. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kalous O, Conklin D, Desai AJ, O’Brien NA,

Ginther C, Anderson L, Cohen DJ, Britten CD, Taylor I, Christensen

JG, et al: Dacomitinib (PF-00299804), an irreversible Pan-HER

inhibitor, inhibits proliferation of HER2-amplified breast cancer

cell lines resistant to trastuzumab and lapatinib. Mol Cancer Ther.

11:1978–1987. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Ather F, Hamidi H, Fejzo MS, Letrent S,

Finn RS, Kabbinavar F, Head C and Wong SG: Dacomitinib, an

irreversible Pan-ErbB inhibitor significantly abrogates growth in

head and neck cancer models that exhibit low response to cetuximab.

PLoS One. 8:e561122013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Ercan D, Zejnullahu K, Yonesaka K, Xiao Y,

Capelletti M, Rogers A, Lifshits E, Brown A, Lee C, Christensen JG,

et al: Amplification of EGFR T790M causes resistance to an

irreversible EGFR inhibitor. Oncogene. 29:2346–2356. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Sriuranpong V, Park JI, Amornphimoltham P,

Patel V, Nelkin BD and Gutkind JS: Epidermal growth factor

receptor-independent constitutive activation of STAT3 in head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma is mediated by the autocrine/paracrine

stimulation of the interleukin 6/gp130 cytokine system. Cancer Res.

63:2948–2956. 2003.

|

|

48

|

Gao SP, Mark KG, Leslie K, Pao W, Motoi N,

Gerald WL, Travis WD, Bornmann W, Veach D, Clarkson B, et al:

Mutations in the EGFR kinase domain mediate STAT3 activation via

IL-6 production in human lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Invest.

117:3846–3856. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wang X, Crowe PJ, Goldstein D and Yang JL:

STAT3 inhibition, a novel approach to enhancing targeted therapy in

human cancers (Review). Int J Oncol. 41:1181–1191. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Kim SM, Kwon O-J, Hong YK, Kim JH, Solca

F, Ha SJ, Soo RA, Christensen JG, Lee JH and Cho BC: Activation of

IL-6R/JAK1/STAT3 signaling induces de novo resistance to

irreversible EGFR inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer with

T790M resistance mutation. Mol Cancer Ther. 11:2254–2264. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|