Introduction

Epilepsy is a common clinical disease characterized

by abnormal discharge from neurons in the brain. The pathogenesis

of epilepsy remains to be fully elucidated and its causes are

complex. The hippocampus is the site of high concentration of

neurons and has an important role in the pathogenesis of epilepsy

(1). Excitatory and inhibitory

neurotransmitters present in the central nervous system maintain

normal cerebral function, and glutamate is an important excitatory

neurotransmitter in the brain. Glutamate receptor (GluR)

dysfunction may be an important cause of epilepsy (2). Excessive activation of GluRs may

cause neuronal damage, a variety of neurological damage, and

chronic neurodegenerative diseases (3). The

α-am-ino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)

receptor is an important subtype of ionotropic GluRs (4) and is composed of four subunits

(GluR1, 2, 3 and 4). The primary features of AMPA receptors are

determined by GluR2, with GluR2 protein downregulation considered

to be a molecular switch. Blocking or reducing GluR2 expression

forms a calcium-permeable AMPA receptor, which increases

Ca2+ influx and enhances endogenous glutamate

excitotoxicity (5). In the central

nervous system, the GluR2 subunit is highly expressed in various

neurons. Under normal conditions, GluR2 is abundant in synapses.

Following hypoxia, the expression of GluR2 on the surface of the

neuron membrane is significantly decreased, indicating that the

mechanism of blocking Ca2+ influx has weakened. Without

a GluR2 subunit, the Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors

increases and a large Ca2+ influx is detected, which may

activate a series of intracellular protein kinases or immediate

early genes. The decreased GluR2 expression induced by epileptic

seizure causes an increase in the Ca2+ permeability of

AMPA receptors, resulting in Ca2+ overload, which is an

important cause of delayed neuronal death in hippocampal neurons

(6). Neuropeptide Y (NPY) contains

36 amino acids and was first extracted from the brain tissue of

pigs by Tatemoto et al (7)

in 1982. It is widely distributed in the central and peripheral

nervous systems (8). In the

central nervous system, NPY concentrations are greatest in the

hippocampus. NPY has a protective effect on cerebellum neuronal

cells cultured in vitro and has been demonstrated to possess

an anti-epileptic effect (9);

however, its protective effects are weakened following blocking of

NPY Y1 and Y2 receptors, suggesting that NPY exerts neuroprotective

effects via these receptors (10).

The present study aimed to investigate the functional alterations

in the GluR2 subunit induced by epileptiform discharge in

hippocampal neurons and to investigate whether NPY affects these

functional alterations.

Materials and methods

Animals and reagents

A total of 64 clean male Sprague-Dawley rats, which

were born within 24 h were provided by the Experimental Animal

Center of Hebei Medical University (animal license no. SCXK (Ji)

2013-1-003; Shijiazhuang, China). The rats were maintained in a 12

h light/dark cycle, humidity of 60±5%, 22±3°C. All rats were

allowed free access to food and water. All animal experimental

procedures were performed in strict accordance with the Guidance

Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of National

Institutes of Health (U.S.) and the protocol was approved by the

Institutional Animal Care Committee of Hebei Medical University.

Neurobasal medium, B-27, L-glutamine, fetal bovine serum (FBS;

special grade) and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F-12

medium were purchased from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

(Waltham, MA, USA); poly-L-lysine and trypsin from Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany); and AMPA, NPY and BIBP3226 from

Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY, USA).

Rabbit anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2)

(cat. no. 17490-1-AP) polyclonal antibody and fluorescein

isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G

(cat. no. SA00003-2) were obtained from ProteinTech Group, Inc.

(Chicago, IL, USA); rabbit anti-phosphorylated (p)-GluR2 (Tyr876)

(cat. no. 4027) antibody and rabbit anti-GluR2 (cat. no. 5306)

antibody from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA).

Mouse anti-β-actin (cat. no. sc-130300) from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). Horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary

antibodies (cat. nos. 7072 and 7071) from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). The random primers were

obtained from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI, USA).

Culture of hippocampal neurons

Hippocampal neurons were primarily cultured as

described by Yang et al (11). Following intraperitoneal injection

of anesthetic (pentobarbital sodium, 3 µl/g), Neonatal

Sprague-Dawley rats aged <24 h were surface sterilized with

disinfectant (75% alcohol) and sacrificed by decapitation and the

brains were extracted and placed in DMEM/F-12 medium at 0°C.

Bilateral hippocampi were harvested under an anatomical microscope.

Following removal of the meninges, the brain tissue was cut into

pieces and immersed in 0.125% trypsin (5X volume of brain tissue).

The samples were digested in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C

for 15 min. The digestion was terminated by adding DMEM/F-12 medium

containing 10% serum. All samples were triturated and filtered with

a 200-mesh screen. The resulting cell suspension was adjusted to

~1×105/ml with DMEM/F-12 medium containing 10% FBS,

seeded into 6-well plates with polylysine-coated coverslips (3

ml/well) and placed in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 24

h. The medium was subsequently replaced with neuronal medium

(Neurobasal medium), supplemented with 2% B-27, 100 U/ml penicillin

and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Half of the neuronal medium was

replaced with fresh every 3 days, for 7–9 days, following which the

purified neurons were harvested.

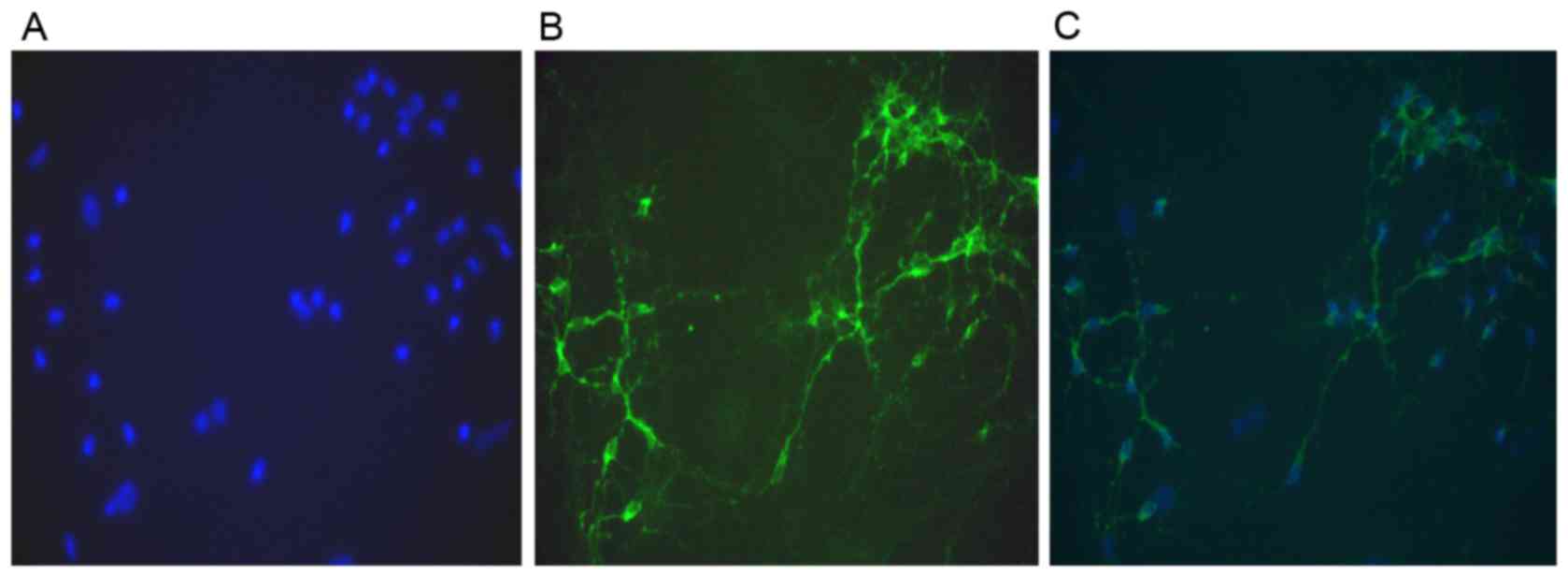

Identification of hippocampal

neurons

MAP-2 is a neuron-specific protein and a marker of

neuronal differentiation (12). At

day 9 of in vitro culture, the hippocampal neurons on glass

slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, washed three

times with PBS for 5 min each time, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton

X-100 for 10 min and washed three times with PBS for 5 min each

time. Cells were blocked with 3% goat serum (OriGene Technologies,

Inc., Beijing, China) at room temperature for 30 min and incubated

with MAP-2 antibody (1:100) at 4°C overnight. Following three

washes with PBS for 5 min each time, cells were incubated with a

FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:100) at 37°C for 1 h,

followed by a further three washes with PBS for 5 min each time.

Cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 for 5 min, washed

three times with PBS for 5 min each time and observed under a

fluorescence microscope.

Group assignment

Following 12 days of in vitro culture,

hippocampal neurons were assigned to the following groups: Control,

Mg2+-free, NPY+Mg2+-free and

BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free. In the control group, neurons

were treated with normal extracellular fluid for 3 h. In the

Mg2+-free group, neurons were treated with

Mg2+-free extracellular fluid for 3 h. In the

NPY+Mg2+-free group, neurons were incubated with cell

culture fluid containing NPY at a final concentration of 1 µmol/l

for 30 min and then with Mg2+-free extracellular fluid

for 3 h. In the BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free group, neurons

were incubated with cell culture fluid containing the NPY Y1

receptor blocker BIBP3226 at a final concentration of 1 µmol/l for

30 min, with NPY at a final concentration of 1 µmol/l for 30 min

and finally with Mg2+-free extracellular fluid for 3 h.

Afterwards, all groups received normal extracellular fluid for 1 h.

Cells were subsequently analyzed using the patch clamp technique,

western blot analysis to measure GluR2 and phosphorylated GluR2

protein expression levels, and RT-qPCR to measure GluR2 mRNA

expression levels.

Normal extracellular fluid comprised: NaCl, 147 mM;

4-(2-hydroxyethyl) −1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 10 mM;

glucose, 13 mM; KC1, 2 mM; CaCl2, 2 mM; and

MgC12, 2 mM; adjusted to pH 7.3 with 5 mM NaOH; osmotic

pressure 280–320 mM. Mg2+-free extracellular fluid

comprised: NaCl, 147 mM; HEPES, 10 mM; glucose, 13 mM; KC1, 2 mM;

and CaCl2, 2 mM; adjusted to pH 7.3 with 5 mM NaOH;

osmotic pressure 280–320 mM.

Using the patch clamp technique, the action

potential of neurons was recorded in the control,

Mg2+-free and NPY+Mg2+-free groups in

accordance with the method of DeLorenzo et al (13).

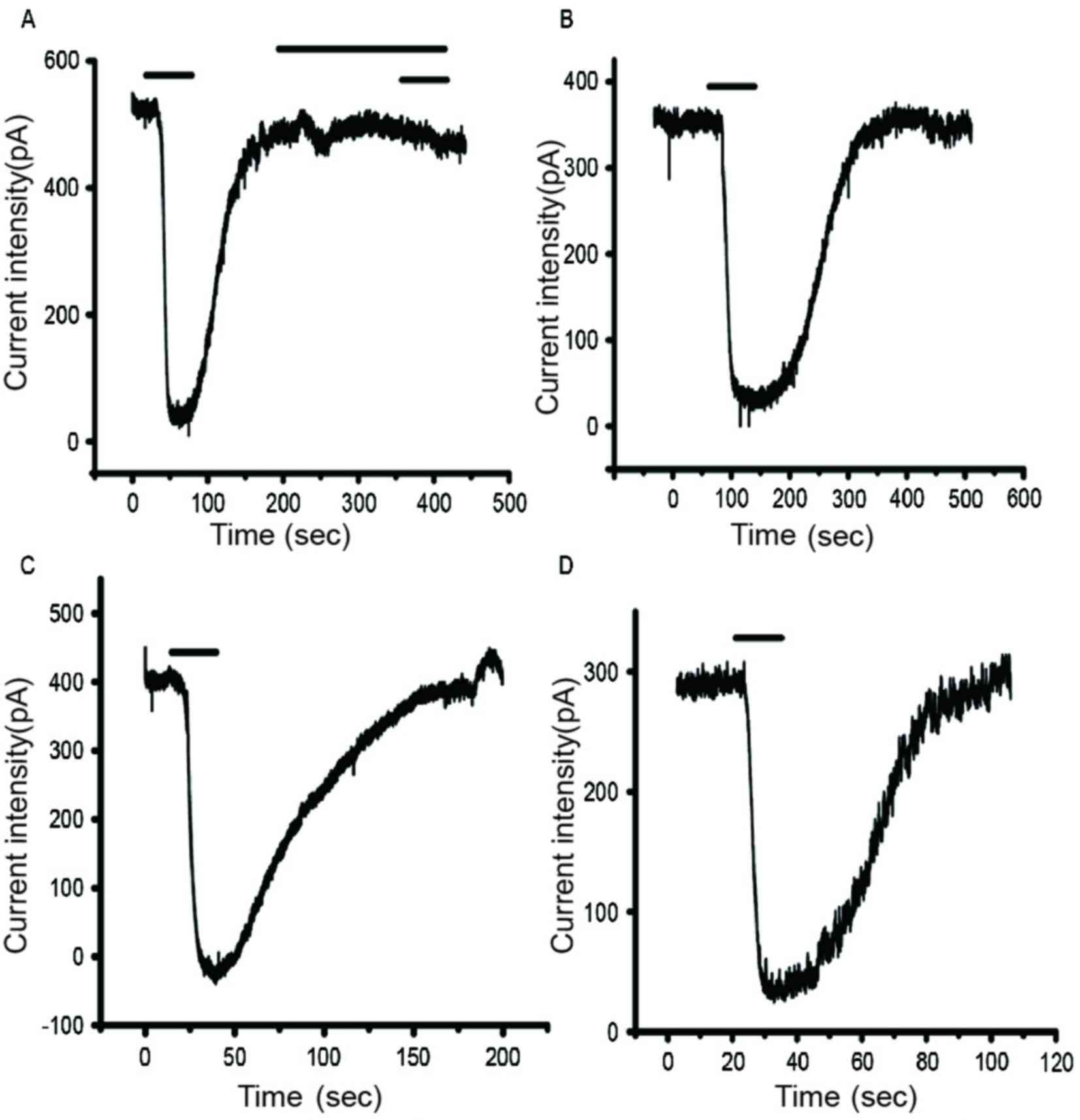

Detection of AMPA current

(IAMPA)

IAMPA in neurons was recorded using the

patch clamp technique (14,15).

Cell slides were placed in a 0.3 ml bath and perfused with

extracellular fluid at 2 ml/min to ensure fluid exchange in 2 min.

Cells were observed under an inverted microscope. Neurons with a

distinct stereoscopic outline and smooth surface were used for the

sealing experiment. With a three-dimensional manipulator, a glass

microelectrode with impedance of 1–3 MΩ and pipette solution

(Cs-gluconate, 110 mmol/l; CsCl, 30 mmol/l; HEPES, 10 mmol/l; EGTA,

0.2 mmol/l; NaCl, 8 mmol/l; Mg-ATP, 2 mmol/l; Na3GTP,

0.3 mmol/l; phosphocreatine, 10 mmol/l; pH 7.2 adjusted with NaOH)

was connected to the cell surface. Negative pressure was increased

until the cells ruptured. Capacitive current and series resistance

were compensated and a whole-cell recording created. Voltage was

held at −70 mV for 5 min, following which the intracellular fluid

and pipette solution were completely replaced, and 100 µmol/l AMPA

was administered to induce inward current. This current was

IAMPA. To further verify this, AMPA was measured

following elution and the membrane current returned to normal. When

100 µmol/l AMPA was administered, 10 µmol/l

6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione was used to block the AMPA

receptor and the original inward current could not be detected.

Thus, the recorded current was IAMPA. To exclude error

in different cells, peak current density was measured using

pA/pF.

Western blot analysis of GluR2 protein

expression and phosphorylation levels

Cells were harvested, washed with PBS, lysed with

precooled radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China) and centrifuged at

12,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant, containing

the total proteins from the hippocampal neurons, was collected.

Protein concentrations were determined by the Lowry method. Total

proteins (100 µg) were separated by electrophoresis on 5% stacking

and 10% separating gels at 100 V for 150 min. Separated proteins

were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes.

Membranes were blocked by 5% non-fat milk in 0.01 mol/l PBS at room

temperature for 2 h, incubated with primary antibody at 4°C

overnight (1:1,000), washed three times, incubated with a

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:400) at

37°C for 1 h and washed three times. Protein bands were visualized

with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai,

China) and the gray values were measured and quantitatively

analyzed with BandScan version 5.0 (Glyko; BioMarin Pharmaceutical,

Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA). The experiments were performed in

triplicate.

RT-qPCR analysis of GluR2 mRNA

expression levels

Following the removal of cell medium, 1 ml

TRIzol® was added to each well. The samples were

triturated and placed in a ribozyme-free centrifuge tube for 5 min.

Subsequently, 0.2 ml chloroform was added to each tube, which were

vigorously agitated for 15 sec, rested for 5 min and centrifuged at

13,800 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was

transferred to a new centrifuge tube, treated with an equal volume

of isopropanol and centrifuged at 13,800 × g at 4°C for 10

min. A feathery white precipitate was observed at the bottom of the

tube, the supernatant was discarded and 1 ml 75% ethanol [prepared

with diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water] was added. The

precipitate was washed and centrifuged at 5,400 × g at 4°C

for 5 min. Following removal of the supernatant, the sample was

air-dried for 3–5 min. RNA was fully dissolved with 20–30 µl of

DEPC-treated water and its purity measured using an ultraviolet

spectrophotometer. cDNA was synthesized using the EasyScript

First-strand cDNA synthesis superMix kit (Beijing TransGen Biotech

Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Rat GluR2 primer sequences were

synthesized by Promega Corporation (Table I). The reaction mixture was as

follows: 2X UltraSYBR® Mixture (with ROX), 10 µl;

forward primer (10 µmol/l), 1 µl; reverse primer (10 µmol/l), 1 µl;

cDNA, 8 µl. The total reaction volume was 20 µl. qPCR cycling

conditions were as follows: An initial predenaturation step at 95°C

for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15

sec, annealing at 58°C for 20 sec and extension at 72°C for 27 sec.

Following amplification, results were analyzed with an ABI 7300

Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The relative value (RQ value) of target gene expression to

the internal reference gene GAPDH was detected and calculated

(16).

| Table I.Specific primers for GluR2 and GAPDH

used in reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction. |

Table I.

Specific primers for GluR2 and GAPDH

used in reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction.

| Gene | Primer sequence

(5′-3′) | Product size

(bp) |

|---|

| GluR2 | F:

CAAGTTCGCATACCTCTA | 207 |

|

| R:

TTATCCCTTTCACAGTCC |

|

| GAPDH | F:

TGAACGGGAAGCTCACTGG | 120 |

|

| R:

GCTTCACCACCTTCTTGATGTC |

|

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with SPSS version 10.0 (SPSS,

Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) using tests for normality and homogeneity

of variance. Data that obeyed normality and homogeneity of variance

were analyzed using analysis of variance for completely random

design. Paired comparison was conducted with the least significant

difference post hoc test. Data were expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

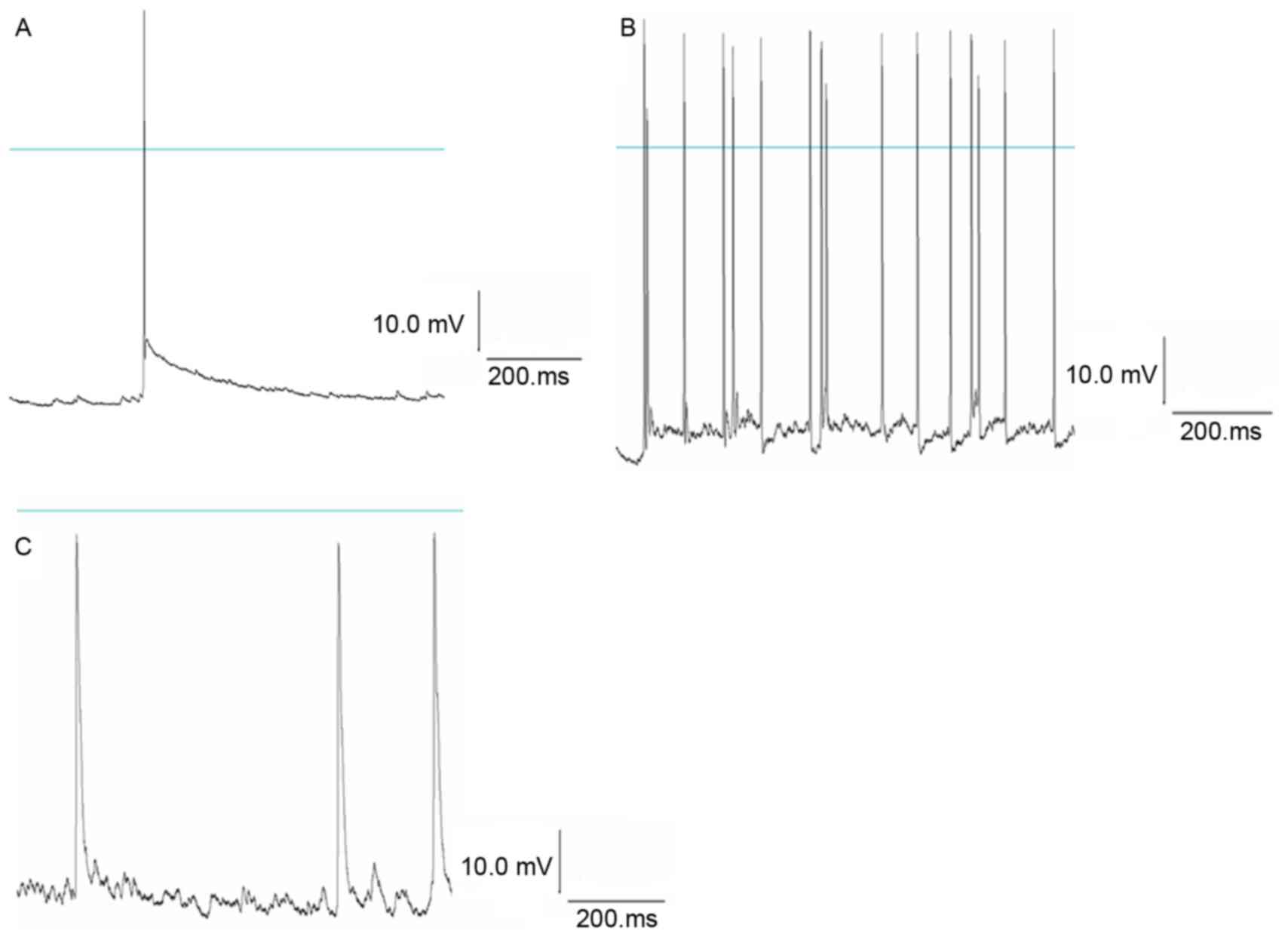

NPY suppresses epileptiform discharges

in hippocampal neurons

Primary cultured hippocampal neurons had axons and

dendrites. Immunostaining of MAP-2 revealed that neuronal purity

was >95% (Fig. 1). The patch

clamp technique records the normal action potential of hippocampal

neurons. Following treatment with Mg2+-free

extracellular fluid for 3 h followed by normal extracellular fluid,

a continuously stable action potential was detected in the neurons;

the frequency and amplitude appeared greater compared with the

control group, indicating spontaneous epileptiform discharges in

the neurons. Following treatment with NPY 1 µmol/l for 30 min,

Mg2+-free extracellular fluid for 3 h and normal

extracellular fluid, the frequency and amplitude of the action

potential were significantly reduced in NPY+Mg2+-free

group compared with the Mg2+-free group (P<0.05;

Fig. 2; Tables II and III). This suggested that NPY

significantly inhibited abnormal discharges in hippocampal

neurons.

| Table II.Comparison of frequency of action

potential in three groups. |

Table II.

Comparison of frequency of action

potential in three groups.

| Group | Frequency

(number/s) |

|---|

|

Mg2+-free |

13.86±2.19a |

|

NPY+Mg2+-free |

1.89±0.69b |

| Control | 0.85±0.22 |

| Table III.Comparison of amplitude of action

potential in three groups. |

Table III.

Comparison of amplitude of action

potential in three groups.

| Group | Amplitude (mV) |

|---|

|

Mg2+-free |

81.25±5.18a |

|

NPY+Mg2+-free |

40.06±2.31b |

| Control | 35.56±1.23 |

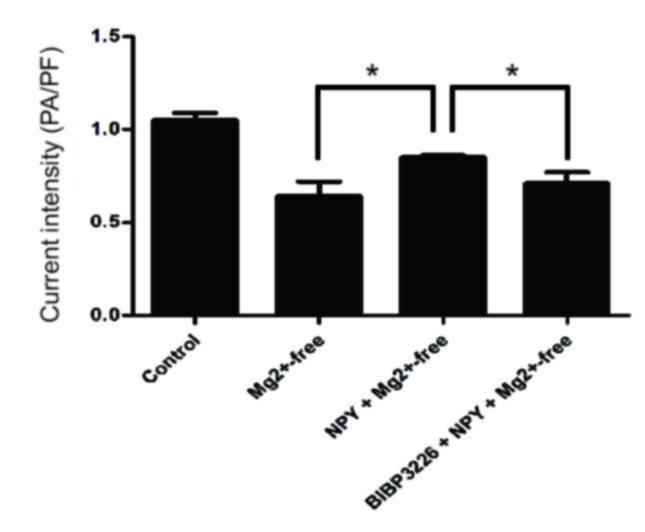

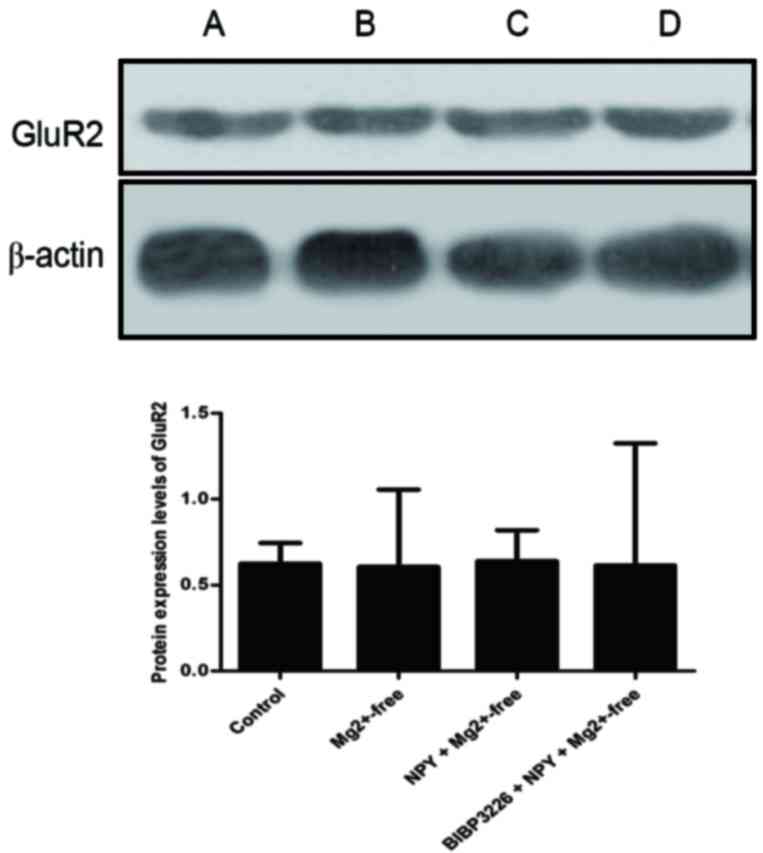

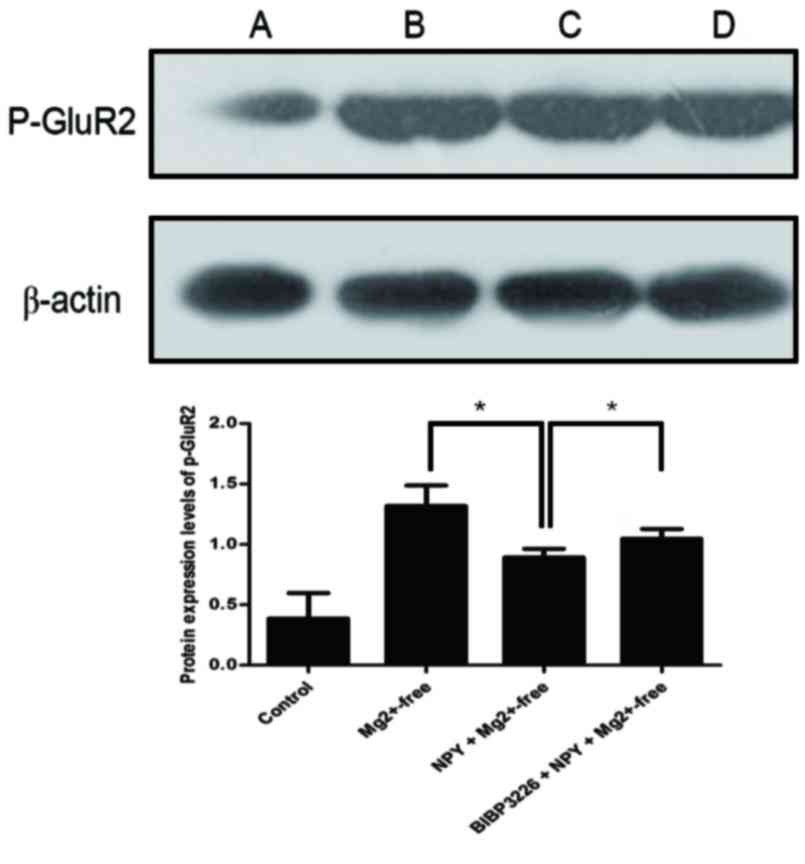

Epileptiform discharges in hippocampal

neurons inhibit the function of AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit

IAMPA detection results demonstrated that

peak current density was significantly reduced in the

Mg2+-free group compared with the control group

(P<0.05; Figs. 3 and 4; Table

IV). Protein expression levels of GluR2 were slightly reduced

(P>0.05; Fig. 5; Table V) and those of p-GluR2 were

significantly greater (P<0.05; Fig.

6; Table VI) in the

Mg2+-free group compared with the control group. GluR2

mRNA expression levels were significantly reduced in the

Mg2+-free group compared with the control group

(P<0.05; Fig. 7; Table VII). These results suggested that

epileptiform discharges in hippocampal neurons may induce the

suppression of the function of the GluR2 subunit.

| Table IV.Current density of primary cultured

hippocampal neurons induced by

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid. |

Table IV.

Current density of primary cultured

hippocampal neurons induced by

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid.

| Group | Current density

(pA/pF) |

|---|

| Control | 1.05±0.04 |

|

Mg2+-free |

0.64±0.08a |

|

NPY+Mg2+-free |

0.85±0.01b |

|

BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free |

0.71±0.06a |

| Table V.Protein expression levels of GluR2,

as assessed by western blot analysis. |

Table V.

Protein expression levels of GluR2,

as assessed by western blot analysis.

| Group | GluR2 |

|---|

| Control | 0.6241±0.15 |

|

Mg2+-free | 0.6057±0.25 |

|

NPY+Mg2+-free | 0.6397±0.18 |

|

BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free | 0.6146±0.21 |

| Table VI.Protein expression levels of p-GluR2,

as assessed by western blot analysis. |

Table VI.

Protein expression levels of p-GluR2,

as assessed by western blot analysis.

| Group | p-GluR2 |

|---|

| Control | 0.3879±0.21 |

|

Mg2+-free |

1.3173±0.17a |

|

NPY+Mg2+-free |

0.8918±0.07b |

|

BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free |

1.0483±0.08a |

| Table VII.mRNA expression levels of GluR2, as

assessed by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction. |

Table VII.

mRNA expression levels of GluR2, as

assessed by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction.

| Group | GluR2 |

|---|

| Control | 1.016±0.11 |

|

Mg2+-free |

0.179±0.16a |

|

NPY+Mg2+-free |

0.713±0.08b |

|

BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free |

0.394±0.05a |

NPY relieves the inhibition of GluR2

subunit function induced by epileptiform discharges in hippocampal

neurons

Peak current density was significantly greater in

the NPY+Mg2+-free group compared with the

Mg2+-free group (P<0.05; Figs. 3 and 4; Table

IV). Protein expression levels of GluR2 were slightly increased

(P>0.05; Fig. 5; Table V) and those of p-GluR2 were

significantly reduced (P<0.05; Fig.

6; Table VI) in the

NPY+Mg2+-free group compared with the

Mg2+-free group. GluR2 mRNA expression levels were

significantly greater in the NPY+Mg2+-free group

compared with the Mg2+-free group (P<0.05; Fig. 7; Table VII). These findings indicated

that NPY weakened the inhibition of GluR2 function induced by

epileptiform discharges in neurons.

NPY regulates GluR2 subunit function

possibly via the Y1 receptor

Peak current density was significantly reduced in

the BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free group compared with the

NPY+Mg2+-free group (P<0.05; Figs. 3 and 4; Table

IV). Protein expression levels of GluR2 were slightly reduced

(P>0.05; Fig. 5; Table V) and those of p-GluR2 were

significantly greater (P<0.05; Fig.

6; Table VI) in the

BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free group compared with the

NPY+Mg2+-free group. GluR2 mRNA expression levels were

significantly reduced in the BIBP3226+NPY+Mg2+-free

group compared with the NPY+Mg2+-free group (P<0.05;

Fig. 7; Table VII).

Discussion

Epilepsy is a brain disorder characterized by the

abnormal discharge of neurons in the brain. The pathogenesis of

epilepsy remains unclear and it may be that a variety of factors

contribute to its occurrence. Neuronal loss occurs, and is

accompanied by a large number of abnormal discharge neurons in the

lesion. Ion channel dysfunction in cells causes seizures; this is

the ‘epileptic neuron’ theory (17,18).

The hippocampus is the site of a high concentration of neurons and

possesses an important role in the pathogenesis of epilepsy:

Hippocampal sclerosis is a common cause of temporal lobe epilepsy.

The structure of the nervous system is complex and there are

numerous factors restricting its study in vivo.

Electrophysiological testing, including the patch clamp technique,

is not easy to implement. Hippocampal slices and neuronal cultures

have attracted increasing attention in the study of epilepsy

(19).

Mg2+ serves an important role in

maintaining normal electric activity in the central nervous system

(20). DeLorenzo et al

(13) reported that the removal of

Mg2+ from the cell medium, or treatment with

Mg2+-free extracellular fluid for 3 h, may successfully

induce spontaneous recurrent epileptiform discharges in primary

cultured hippocampal neurons. Such cultured neurons do not possess

real anatomical connections or clinical manifestations, but the

spontaneous recurrent action potential evoked by

Mg2+-free conditions is similar to the

electrophysiological activity during epileptic seizures and

anti-epileptic drugs may prevent such action potentials (21–22).

This technique has been used in studies of the biochemical,

electrophysiological and molecular mechanisms of acquired epilepsy

(23).

NPY is widely distributed in the central nervous

system (cerebral cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus and

brain stem) and the peripheral nervous system. In the central

nervous system, NPY concentration is greatest in the hippocampus.

NPY has an anti-epileptic effect (24,25)

and a protective effect on cerebellum neuronal cells cultured in

vitro. These protective effects are weakened following blocking

of the NPY Y1 and Y2 receptors, suggesting that NPY exerts

neuroprotective effects via the Y1 and Y2 receptors (26–28).

In the present study, epileptiform discharges were detected in

hippocampal neurons of rats following treatment with

Mg2+-free extracellular fluid. Following treatment with

NPY and Mg2+-free extracellular fluid, epileptiform

discharges were notably weakened, indicating that NPY may suppress

epileptiform discharges in neurons.

Excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters present

in the central nervous system are responsible for the balance of a

complex network and maintain normal cerebral function. Following

excitatory neurotransmitter increases, or inhibitory

neurotransmitter decreases, the ratio may become unbalanced. GluR

functional alteration is one of the important causes of epilepsy

(29). Excessive activation of

GluRs may cause neuronal damage, a variety of neurological damage,

and chronic neurodegenerative diseases, including cerebral ischemia

and hypoxia, epilepsy and brain trauma. Previous studies have

confirmed that following epilepsy, a massive release of glutamate

and overactivation of its receptors causes a Ca2+

influx, followed by delayed neuronal death and secondary injury

(30,31).

GluR may be divided into metabotropic types (coupled

with G protein) and ionotropic types (containing ion channels). In

accordance with pharmacological properties, molecular

characteristics and electrophysiological properties, ionotropic

GluR may be divided into three subtypes: AMPA receptor,

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor and kainate receptor (32).

The AMPA receptor, a type of ion channel protein,

may be regulated by membrane potential, glutamate and AMPA. It is

composed of four subunits (GluR1, 2, 3 and 4) encoded by different

genes (33). Due to the low

calcium ion permeability induced by mRNA Q/R site editing, the

relative content of GluR2 subunit in the AMPA receptor determines

the functional properties of AMPA receptors. An AMPA receptor

containing the GluR2 subunit is permeable to monovalent cations

(Na+, K+), but not to divalent cations

(Ca2+); an AMPA receptor without a GluR2 subunit is

highly permeable to Ca2+ (34,35).

The primary features of AMPA receptors are therefore determined by

GluR2 and GluR2 protein downregulation is considered to be a

molecular switch (36). Blocking

or reducing GluR2 expression forms a calcium-permeable AMPA

receptor, increases Ca2+ influx and enhances endogenous

glutamate excitotoxicity.

In the central nervous system, the GluR2 subunit is

highly expressed in various neurons. Under normal conditions, GluR2

is abundant in synapses. Following hypoxia, the content of GluR2 on

the membrane surface of the neuron is significantly decreased and

the number of synapses containing GluR2 reduced, indicating that

the mechanism of blocking Ca2+ influx has markedly

weakened (37).

The results of the present study demonstrated that,

following treatment with Mg2+-free extracellular fluid,

GluR2 subunit mRNA expression levels were decreased, but protein

phosphorylation levels were increased, suggesting that the GluR2

subunit had been reduced or its activity deceased in neuronal

membranes. Abnormal activation of neurons diminished AMPA receptor

GluR2 subunit expression. It has previously been demonstrated that

without a GluR2 subunit, the Ca2+ permeability of AMPA

receptors increases and a large Ca2+ influx may be

detected, able to activate a series of intracellular protein

kinases or immediate early genes (38) and resulting in a decrease in GluR2

subunit expression. Grooms et al (39) hypothesized that the decreased GluR2

expression induced by epileptic seizure caused an increase in the

Ca2+ permeability of AMPA receptors, resulting in

Ca2+ overload, an important cause of delayed neuronal

death in hippocampal neurons. Sanchez et al (40) demonstrated that perinatal

hypoxia-induced seizures increased the Ca2+ permeability

of AMPA receptors.

The present study used a whole cell patch clamp

technique to record IAMPA in neurons cultured in

vitro. AMPA is a selective agonist of the exogenous AMPA

receptor, and is synthesized artificially. AMPA binding to AMPA

receptor depolarizes the cell membrane and opens ion channels.

Results from the present study demonstrated that IAMPA

was reduced in the Mg2+-free group compared with the

control group. The decreased degree of IAMPA was

markedly diminished in the NPY+Mg2+-free group compared

with the Mg2+-free group. This effect was inhibited by

BIBP3226. These results indicated that epileptiform discharges in

cells may induce a reduction in the functions of AMPA

receptors.

The AMPA receptor is a membrane receptor, the

function of which may be regulated by multiple internal and

external cell processes; phosphorylation has the greatest influence

on its function (41). PDZ

domain-containing proteins may interact with the PDZ structural

domain at the GluR2 C terminus following binding to activate

protein kinase C-α, which induces ser880 phosphorylation at the

GluR2 C terminus and endocytosis of the GluR2 complex, reducing the

expression of AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit on the surface of neurons

and thus serving an important role in AMPA receptor expression and

transport (42,43).

IAMPA is the most direct indicator

reflecting electrophysiological alterations in AMPA receptors. A

decrease in IAMPA reflects a reduction in receptor

function. During epileptiform discharges, IAMPA falls,

indicating that AMPA receptor activity is reduced. Based on the

RT-qPCR and western blot analysis results, it is hypothesized that

epileptiform discharges in hippocampal neurons led to the

phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit on the membrane

surface and suppressed GluR2 subunit mRNA. The AMPA receptor GluR2

subunit on the membrane surface was transported into cells, so AMPA

receptor activity on the membrane surface diminished. Therefore,

neuron total protein detection did not alter significantly between

groups. The lack of the normal AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit pathway

on the membrane surface causes a high Ca2+ permeability

and may induce a rapid Ca2+ influx, Ca2+

concentration increase and a series of pathological reactions.

IAMPA and GluR2 mRNA expression levels

were significantly greater, but GluR2 protein phosphorylation

levels were significantly reduced in the NPY+Mg2+-free

group compared with the Mg2+-free group. It is

hypothesized that NPY may inhibit the alterations in AMPA receptor

function induced by epileptiform discharges, suggesting that NPY

may have affected AMPA receptor functions and avoided excessive

reduction of IAMPA by regulating the GluR2 subunit. The

inhibitory effect of NPY was suppressed by treatment with the Y1

receptor blocker BIBP3226. NPY exerts different effects by binding

to different receptors; NPY receptors belong to the G

protein-coupled receptor family (44) and contain Y1, Y2, Y3, Y4 and Y5

subtypes in humans. Different NPY receptors are distributed in

different regions of the body; the Y1 receptor is primarily

expressed in the cerebral cortex, amygdala and hippocampus

(45). Previous studies on the

anti-epileptic effect of NPY have primarily focused on Y2 and Y5

receptors (46,47). It is hypothesized that NPY exerted

an anti-epileptic effect in the present study via the Y1 receptor

expressed on the membrane surface of hippocampal neurons. This may

be a pharmacological mechanism underlying the anti-epileptic effect

of NPY.

In conclusion, the present study investigated the

functional alterations in the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit and the

effect of NPY on these alterations during epileptiform discharges

in hippocampal neurons, to provide a theoretical basis for

specifically blocking pathological process and for the design of

therapeutic agents with low toxicity for the treatment of

epilepsy.

References

|

1

|

Rocha AK, de Lima E, Amaral FG, Peres R,

Cipolla-Neto J and Amado D: Pilocarpine-induced epilepsy alters the

expression and daily variation of the nuclear receptor RORα in the

hippocampus of rats. Epilepsy Behav. 55:38–46. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Muldoon SF, Villette V, Tressard T,

Malvache A, Reichinnek S, Bartolomei F and Cossart R: GABAergic

inhibition shapes interictal dynamics in awake epileptic mice.

Brain. 138:2875–2890. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Tsamis KI, Mytilinaios DG, Njau SN and

Baloyannis SJ: Glutamate receptors in human caudate nucleus in

normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res.

10:469–475. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ettinger AB, LoPresti A, Yang H, Williams

B, Zhou S, Fain R and Laurenza A: Psychiatric and behavioral

adverse events in randomized clinical studies of the noncompetitive

AMPA receptor antagonist perampanel. Epilepsia. 56:1252–1263. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Harlow DE, Saul KE, Komuro H and Macklin

WB: Myelin proteolipid protein complexes with αv integrin and AMPA

receptors in vivo and regulates AMPA-dependent oligodendrocyte

progenitor cell migration through the modulation of cell-surface

GluR2 expression. J Neurosci. 35:12018–12032. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Friedman LK, Velísková J, Kaur J, Magrys

BW and Liu H: GluR2(B) knockdown accelerates CA3 injury after

kainate seizures. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 62:733–750. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tatemoto K, Carlquist M and Mutt V:

Neuropeptide Y-a novel brain peptide with structural similarities

to peptide YY and pancreatic polypeptide. Nature. 296:659–660.

1982. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Woldbye DP and Kokaia M: Neuropeptide Y

and seizures: Effects of exogenously applied ligands.

Neuropeptides. 38:253–260. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Malva JO, Xapelli S, Baptista S, Valero J,

Agasse F, Ferreira R and Silva AP: Multifaces of neuropeptide Y in

the brain-neuroprotection, neurogenesis and neuroinflammation.

Neuropeptides. 46:299–308. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Vezzani A and Sperk G: Overexpression of

NPY and Y2 receptors in epileptic brain tissue: An endogenous

neuroprotective mechanism in temporal lobe epilepsy? Neuropeptides.

38:245–252. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yang S, Zhou W, Zhang Y, Yan C and Zhao Y:

Effects of Liuwei Dihuang decoction on ion channels and synaptic

transmission in cultured hippocampal neuron of rat. J

Ethnopharmacol. 106:166–172. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Atalay B, Caner H, Can A and Cekinmez M:

Attenuation of microtubule associated protein-2 degradation after

mild head injury by mexiletine and calpain-2 inhibitor. Br J

Neurosurg. 21:281–287. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

DeLorenzo RJ, Sombati S and Coulter DA:

Effects of topiramate on sustained repetitive firing and

spontaneous recurrent seizure discharges in cultured hippocampal

neurons. Epilepsia. 41:(Suppl 1). S40–S44. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rozov A, Sprengel R and Seeburg PH:

GluA2-lacking AMPA receptors in hippocampal CA1 cell synapses:

Evidence from gene-targeted mice. Front Mol Neurosci. 5:222012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rozov A, Zivkovic AR and Schwarz MK:

Homer1 gene products orchestrate Ca(2+)-permeable AMPA

receptor distribution and LTP expression. Front Synaptic Neurosci.

4:42012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Curtis KM, Gomez LA, Rios C, Garbayo E,

Raval AP, Perez-Pinzon MA and Schiller PC: EF1alpha and RPL13a

represent normalization genes suitable for RT-qPCR analysis of bone

marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. BMC Mol Biol. 11:612010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Dudek FE and Rogawski MA: The epileptic

neuron redux. Epilepsy Curr. 2:151–152. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bernard C, Anderson A, Becker A, Poolos

NP, Beck H and Johnston D: Acquired dendritic channelopathy in

temporal lobe epilepsy. Science. 305:532–535. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kato K, Sekino Y, Takahashi H, Yasuda H

and Shirao T: Increase in AMPA receptor-mediated miniature EPSC

amplitude after chronic NMDA receptor blockade in cultured

hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 418:4–8. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Solger J, Heinemann U and Behr J:

Electrical and chemical long-term depression do not attenuate

low-Mg2+-induced epileptiform activity in the entorhinal cortex.

Epilepsia. 46:509–516. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hu Y, Jiang L, Chen H and Zhang X:

Expression of AMPA receptor subunits in hippocampus after status

convulsion. Childs Nerv Syst. 28:911–918. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ma YX, Yin JB, Fan XT, Xu HW, An N, Wan

ZB, Li ZF, Liu GL, Zhang YH and Yang Hui: Establishment of kainic

acid induced temporal lobe epilepsy in rat and study of its

neurogenesis. Acta Academiae Medicinae Militaris Tertiae.

29:872–875. 2007.

|

|

23

|

Sombati S and Delorenzo RJ: Recurrent

spontaneous seizure activity in hippocampal neuronal networks in

culture. J Neurophysiol. 73:1706–1711. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Furtinger S, Pirker S, Czech T,

Baumgartner C, Ransmayr G and Sperk G: Plasticity of Y1 and Y2

receptors and neuropeptide Y fibers in patients with temporal lobe

epilepsy. J Neurosci. 21:5804–5812. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sørensen G and Woldbye DP: Mice lacking

neuropeptide Y show increased sensitivity to cocaine. Synapse.

66:840–843. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yamamoto BK and Raudensky J: The role of

oxidative stress, metabolic compromise, and inflammation in

neuronal injury produced by amphetamine-related drugs of abuse. J

Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 3:203–217. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cadet JL and Krasnova IN: Molecular bases

of methamphetamine-induced neurodegeneration. Int Rev Neurobiol.

88:101–119. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nunes AF, Montero M, Franquinho F, Santos

SD, Malva J, Zimmer J and Sousa MM: Transthyretin knockout mice

display decreased susceptibility to AMPA-induced neurodegeneration.

Neurochem Int. 55:454–457. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hoy KC, Huie JR and Grau JW: AMPA receptor

mediated behavioral plasticity in the isolated rat spinal cord.

Behav Brain Res. 236:319–326. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Blair RE, Sombati S, Churn SB and

Delorenzo RJ: Epileptogenesis causes an N-methyl-d-aspartate

receptor/Ca2+-dependent decrease in

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity in

a hippocampal neuronal culture model of spontaneous recurrent

epileptiform discharges. Eur J Pharmacol. 588:64–71. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Blair RE, Deshpande LS, Sombati S, Elphick

MR, Martin BR and DeLorenzo RJ: Prolonged exposure to WIN55,212-2

causes downregulation of the CB1 receptor and the development of

tolerance to its anticonvulsant effects in the hippocampal neuronal

culture model of acquired epilepsy. Neuropharmacology. 57:208–218.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gardner SM, Takamiya K, Xia J, Suh JG,

Johnson R, Yu S and Huganir RL: Calcium-permeable AMPA receptor

plasticity is mediated by subunit-specific interactions with PICK1

and NSF. Neuron. 45:903–915. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Essin K, Nistri A and Magazanik L:

Evaluation of GluR2 subunit involvement in AMPA receptor function

of neonatal rat hypoglossal motoneurons. Eur J Neurosci.

15:1899–1906. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Palmer CL, Cotton L and Henley JM: The

molecular pharmacology and cell biology of

alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors.

Pharmacol Rev. 57:253–277. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Montero M, Nielsen M, Rønn LC, Møller A,

Noraberg J and Zimmer J: Neuroprotective effects of the AMPA

antagonist PNQX in oxygen-glucose deprivation in mouse hippocampal

slice cultures and global cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Brain Res.

1177:124–135. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Sager C, Tapken D, Kott S and Hollmann M:

Functional modulation of AMPA receptors by transmembrane AMPA

receptor regulatory proteins. Neuroscience. 158:45–54. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Colbourne F, Grooms SY, Zukin RS, Buchan

AM and Bennett MV: Hypothermia rescues hippocampal CA1 neurons and

attenuates down-regulation of the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit after

forebrain ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 100:2906–2910. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Calderone A, Jover T, Mashiko T, Noh KM,

Tanaka H, Bennett MV and Zukin RS: Late calcium EDTA rescues

hippocampal CA1 neurons from global ischemia-induced death. J

Neurosci. 24:9903–9913. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Grooms SY, Opitz T, Bennett MV and Zukin

RS: Status epilepticus decreases glutamate receptor 2 mRNA and

protein expression in hippocampal pyramidal cells before neuronal

death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97:3631–3636. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Sanchez RM, Koh S, Rio C, Wang C, Lamperti

ED, Sharma D, Corfas G and Jensen FE: Decreased glutamate receptor

2 expression and enhanced epileptogenesis in immature rat

hippocampus after perinatal hypoxia-induced seizures. J Neurosci.

21:8154–8163. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hanley JG and Henley JM: PICK1 is a

calcium-sensor for NMDA-induced AMPA receptor trafficking. EMBO J.

24:3266–3278. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang Y, Venkitaramani DV, Gladding CM,

Zhang Y, Kurup P, Molnar E, Collingridge GL and Lombroso PJ: The

tyrosine phosphatase STEP mediates AMPA receptor endocytosis after

metabotropic glutamate receptor stimulation. J Neurosci.

28:10561–10566. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dev KK, Nakanishi S and Henley JM: The PDZ

domain of PICK1 differentially accepts protein kinase C-alpha and

GluR2 as interacting ligands. J Biol Chem. 279:41393–41397. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Alvaro AR, Martins J, Costa AC, Fernandes

E, Carvalho F, Ambrósio AF and Cavadas C: Neuropeptide Y protects

retinal neural cells against cell death induced by ecstasy.

Neuroscience. 152:97–105. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Baptista S, Bento AR, Gonçalves J,

Bernardino L, Summavielle T, Lobo A, Fontes-Ribeiro C, Malva JO,

Agasse F and Silva AP: Neuropeptide Y promotes neurogenesis and

protection against methamphetamine-induced toxicity in mouse

dentate gyrus-derived neurosphere cultures. Neuropharmacology.

62:2413–2423. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Jinde S, Masui A, Morinobu S, Noda A and

Kato N: Differential changes in messenger RNA expressions and

binding sites of neuropeptide Y Y1, Y2 and Y5 receptors in the

hippocampus of an epileptic mutant rat: Noda epileptic rat.

Neuroscience. 115:1035–1045. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Woldbye DP, Nanobashvili A, Sørensen AT,

Husum H, Bolwig TG, Sørensen G, Ernfors P and Kokaia M:

Differential suppression of seizures via Y2 and Y5 neuropeptide Y

receptors. Neurobiol Dis. 20:760–772. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|