Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are crucial cellular

secondary messengers involved in diverse biological processes in

cancer cells (1–7). ROS are oxygen-containing species,

including superoxide (O2•−), hydroxyl

(•OH), and hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2). The majority of ROS are produced as

side products of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria

(4,5,8,9), but

they are also induced by NADPH oxidase (NOX), growth factors, and

cytokines (2,4). ROS are increased in many types of

cancers and these elevated ROS are highly involved in tumor

development and progression (2,6,10).

High levels of ROS exert cytotoxic effects by inducing DNA damage

or cell death, thereby limiting cancer progression (2,4,5,7). On

the other hand, at low levels, ROS function as signaling molecules

that can induce nucleic acid and protein synthesis, cell cycle

progression, the expression of numerous genes involved in cell

proliferation and survival, the activation of redox-sensitive

transcription factors [such as p53, hypoxia inducible factor

(HIF)-1, and NF-κB], epigenetic alterations, and tumorigenesis

(2,4,5,7). In

addition, ROS have been shown to induce epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) in cancer cells (11–14).

However, the precise mechanism of ROS-induced EMT remains to be

elucidated.

EMT plays critical roles in embryogenesis as well as

in tumor invasion and metastasis. Epithelial cells undergoing EMT

lose their polarization and acquire mesenchymal-like morphology.

EMT is also characterized by decreased expression of epithelial

markers, such as E-cadherin and induction of mesenchymal markers,

such as vimentin. Loss of E-cadherin is considered a hallmark of

EMT (15–19). EMT is regulated by several

transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, Twist-related protein

(Twist)1, Twist2, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox (ZEB)1, ZEB2,

and E12/E47. Snail, a key transcription factor in EMT, promotes

invasion and metastasis in response to several oncogenic signaling

pathways (20–22). Recently, Snail has been implicated

in metabolic alterations, such as glycolytic switch (21,23).

Glycolytic switch is a phenomenon whereby cancer cells rely on

glycolysis more than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation for

ATP production, even when sufficient oxygen is available (24–28).

Recently, we showed that distal-less homeobox-2 (Dlx-2) induces EMT

and glycolytic switch by activating Snail (29,30).

Dlx-2 is one of the human distal-less (Dlx) gene family proteins

and is involved in embryonic development (31,32)

and tumor progression (33–36).

Dlx-2 is known to play an important role in shifting the activity

of TGF-β from tumor suppression to tumor promotion (34).

In this study, we show that ROS induce EMT through

Snail and Dlx-2 cascades. We also show that Dlx-2/Snail signaling

plays a critical role(s) in ROS-induced glycolytic switch,

inhibition of mitochondrial respiration, and cytochrome c oxidase

(COX) inhibition. These results clarify the mechanism by which ROS

promotes tumor progression through Dlx-2/Snail axis-dependent EMT

and glycolytic switch in MCF-7 cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and ROS treatment

MCF-7 cells were obtained from the American Type

Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA; authenticated by short

tandem repeat profiling). MCF-7 cells were cultured in Eagle's

minimal essential medium (EMEM; Hyclone; GE Healthcare, Logan, UT,

USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine

serum (FBS, Hyclone; GE Healthcare) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

(PS, Hyclone; GE Healthcare). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a

humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and were passaged two

times per week. Low-passage cultures (passage 5–25) were used for

all experiments. Cells were routinely checked for mycoplasma

contamination using the Mycoplasma PCR Detection kit (iNtRON

Biotechnology). MCF-7 cells were treated with ROS [200 µM

H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and

10 µM menadione (an O2− generator;

Sigma)].

Transfection and short hairpin RNA

(shRNA) interference

pCR3.1-Snail-Flg (provided by J.I. Yook, Yonsei

University, Korea) was transfected into MCF-7 cells using jetPEI

(Polyplus-transfection SA, New York, NY, USA). pSUPER vectors with

control shRNA and shRNAs against Dlx-2 and Snail were produced and

transfected as described previously (23). shRNA target sequences have also

been described previously (23,29).

Immunoblotting and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Immunoblotting was performed using the following

antibodies: anti-Dlx-2 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA);

anti-Snail (Abgent, San Diego, CA, USA); anti-E-cadherin,

anti-COXVIIc, anti-COX15, and anti-COX19 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Dallas, TX, USA); anti-COXVIc, and anti-COXVIIa (MitoSciences,

Eugene, OR, USA); anti-COX18 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK); anti-α-tubulin

(Biogenex, Fermont, CA, USA).

Total mRNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol

(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the supplier's

instructions. Transcript levels were assessed with reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction using primers

for EMT-inducing transcription factors (including Snail, Slug,

Twist1, Twist2, ZEB1, ZEB2, E12/E47, Dlx-2), E-cadherin,

N-cadherin, vimentin, fibronectin, cluster of differentiation 44

(CD44), COX subunits and assembly factors, and β-actin. Primer

sequences described previously were used (23,29,37),

along with the following additional primers: Twist1 sense,

5′-CAGACCCTCAAGCTGGCGGC-3′; Twist1 antisense,

5′-CCAGGCCCCCTCCATCCTCC-3′; Twist2 sense,

5′-TGGGCACCAGCGAGGAGGAG-3′; Twist2 antisense,

5′-CTGGGGCTGCCCTTCTTGCC-3′; ZEB1 sense,

5′-GGGAGGATGACAGAAAGGAAGG-3′; ZEB1 antisense,

5′-TGCCTCTGGTCCTCTTCAGGTGC-3′; ZEB2 sense,

5′-CAGAAGCCACGATCCAGACCGC-3′; ZEB2 antisense,

5′-GTGCCAAGGCGAGACAGCTCC-3′; E12/E47 sense,

5′-GCCGGGCACATGTGAAAGTAAACAA-3′; E12/E47 antisense,

5′-CAGGTTTCCACAGCATCCCCCTT-3′; N-cadherin sense,

5′-AGCCAACCTTAACTGAGGAGT-3′; N-cadherin antisense,

5′-GGCAAGTTGATTGGAGGGATG-3′; vimentin sense,

5′-TGAAGGAGGAAATGGCTCGTC-3′; vimentin antisense,

5′-GTTTGGAAGAGGCAGAGAAATCC-3′; fibronectin sense,

5′-CAGTGGGAGACCTCGAGAAG-3′; fibronectin antisense,

5′-TCCCTCGGAACATCAGAAAC-3′; CD44 sense, 5′-TGCCGCTTTGCAGGTGTATT-3′;

CD44 antisense, 5′-CCGATGCTCAGAGCTTTCTCC-3′. Values were normalized

to those of β-actin.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

Cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde,

permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked with 2% BSA. Cells

were then incubated overnight with anti-E-cadherin antibody and

immunostained with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse

secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) was

used to stain cell nuclei. Cells were viewed under a fluorescence

microscope.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

assay

ChIP assays were performed using a ChIP assay kit

(EMD Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Isotype control IgG, anti-Dlx-2, and anti-Snail (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology) were used to immunoprecipitate DNA-containing

complexes. ChIP-enriched DNA was analyzed by PCR using primers

complementary to promoter regions containing Dlx-2 or Snail binding

sites, as described previously (23,29).

Assays for mitochondrial respiration,

COX activity, glucose consumption, lactate production, and ATP

production

Mitochondrial respiration and COX activity were

measured as described previously (23,38).

For the mitochondrial respiration assay, exponentially growing

cells (1.5×106) were washed with TD buffer (137 mM NaCl,

5 mM KCl, 0.7 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM Tris-HCl; pH

7.4), collected, and resuspended in complete medium without phenol

red. Cells (5×105) were transferred to a Mitocell

chamber equipped with a Clark O2 electrode (782

O2 Meter; Strathkelvin Instruments, Glasgow, UK).

O2 consumption rates were measured after adding 30 µM

DNP to obtain the maximum respiration rate and specificity for

mitochondrial respiration was confirmed by adding 5 mM KCN. COX

activity was determined by measuring the KCN-sensitive,

COX-dependent O2 consumption rate by adding 3 mM TMPD in

the presence of 30 µM DNP and 20 µM antimycin A.

Glucose, lactate, and intracellular ATP levels in

the media were determined using a glucose oxidation assay kit

(Sigma-Aldrich), a colorimetric and fluorescence-based lactate

assay kit (BioVision, Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA), and an ATP

Bioluminescence Assay kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland),

respectively, according to the manufacturers' instructions. Levels

of glucose, lactate, and intracellular ATP were normalized to

protein concentrations. Levels of ATP produced by aerobic

respiration and glycolysis were determined by measuring lactate

production and O2 consumption (23,39).

Measurement of circularity

Circularity assays were performed as described

previously (29). Briefly,

microscopic images were analyzed with AxioVision LE software

(version 4.8). Circularity was calculated using the formula, 4π

(area/perimeter2). Values closer to 1.0 indicate a more

circular cell morphology.

Statistical analysis

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction, mitochondrial respiration, glucose consumption, lactate

production, and ATP production assays were performed at least in

triplicate. Most experiments were repeated more than twice. Data

were analyzed by Student's t-test (unpaired, two-tailed) for

comparison between two groups, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's

multiple-comparisons test for comparison between three groups, and

two-way ANOVA for comparison between three groups with multiple

factors and results were expressed as mean ± SE. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results and Discussion

Dlx-2/Snail cascade is implicated in

ROS-induced EMT

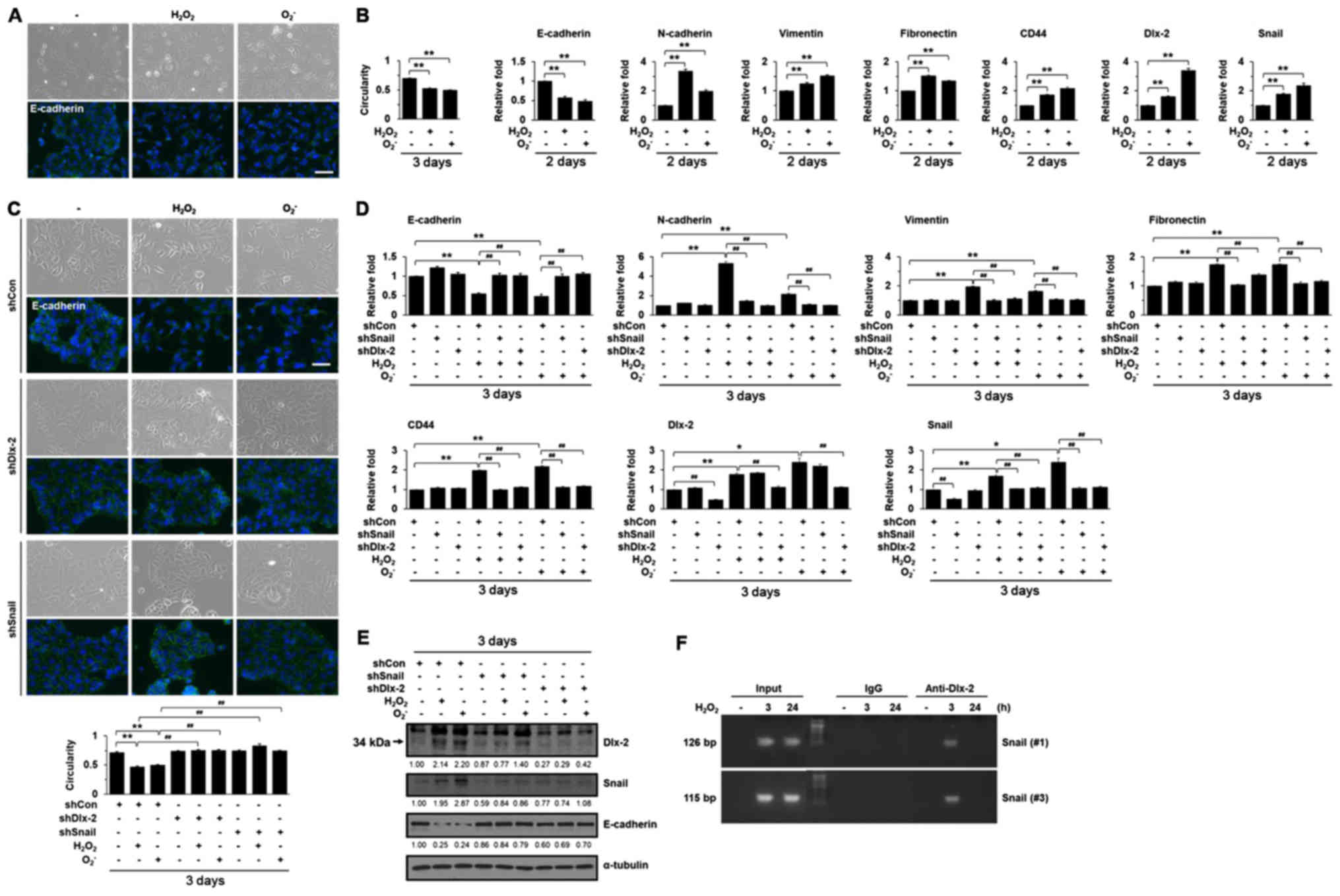

It has been shown that ROS induces EMT by increasing

Snail expression (11–14). We examined the EMT-inducing effects

of H2O2 and O2− in

MCF-7 cells, a non-invasive luminal A subtype breast cancer cell

line. MCF-7 cells have low levels of Snail, but various stimuli

including TGF and Wnt can induce Snail expression, and

subsequently, EMT in MCF-7 cells; thus, MCF-7 cells are widely used

for studying breast cancer, particularly EMT (40–42).

ROS induced a phenotypical change to an elongated morphology with

pseudopodia, which is a characteristic of mesenchymal cells, and

decreased the expression of an epithelial marker, E-cadherin,

indicating that ROS induce EMT (Fig.

1A and B). We further examined the effects of ROS on the

expression of mesenchymal markers, such as N-cadherin, vimentin,

and fibronectin. In addition, we also examined the expression of

CD44, a glycoprotein receptor for various extracellular matrix

(ECM) ligands, such as hyaluronic acid (HA); HA-CD44 interaction

promotes EMT and CSC self-renewal through Nanog expression

(43,44). ROS were shown to increase the

expression of mesenchymal markers including N-cadherin, vimentin,

and fibronectin (Table I and

Fig. 1B). ROS also upregulated the

CD44 expression (Table I and

Fig. 1B). We investigated which

EMT-inducing transcription factors (Snail, Slug, Twist1, Twist2,

ZEB1, ZEB2, E12/E47, and Dlx-2) were involved in ROS

treatment-induced EMT using reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (Table

I). ROS induced Snail and Dlx-2 expression, but had no effect

on the other EMT-inducing transcription factors (Table I and Fig. 1B). Therefore, we examined if the

Dlx-2/Snail cascade was involved in ROS-induced EMT. Dlx-2 and

Snail shRNAs appeared to block the EMT phenotype and downregulation

of E-cadherin induced by ROS (Fig.

1C-E). We also found that Dlx-2 and Snail shRNAs prevented the

ROS-induced expression of N-cadherin, vimentin, fibronectin, and

CD44 (Fig. 1D). Because Dlx-2 has

been shown to be an upstream regulator of Snail (29,30),

we examined the effects of Dlx-2 shRNA on ROS-induced Snail

expression. In the immunoblotting of Dlx-2, anti-Dlx-2 antibody

recognized 2 bands (33). The

lower band (indicated by arrowhead, 34 kDa) is Dlx-2; the higher

band is non-specific band. Expectedly, Snail shRNA suppressed

ROS-induced Snail expression and Dlx-2 shRNA suppressed ROS-induced

Dlx-2 expression. In addition, Dlx-2 shRNA also prevented Snail

induction by ROS, whereas Snail shRNA did not affect Dlx-2

induction by ROS (Fig. 1D and E),

indicating that Dlx-2 consistently acts upstream of ROS-induced

Snail. A ChIP assay showed that ROS increased Dlx-2 binding at the

Snail promoter, which was detected at an early time point (3 h)

after ROS treatment (Fig. 1F).

Dlx-2 appeared to act as a mediator for ROS-Snail-induced EMT.

These results suggest that the Dlx-2/Snail axis are implicated in

ROS-induced EMT.

| Table I.Regulation of EMT markers and

EMT-inducing transcription factors by ROS. |

Table I.

Regulation of EMT markers and

EMT-inducing transcription factors by ROS.

|

|

H2O2 |

O2− |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Genes | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

|---|

| EMT markers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E-cadherin | 0.980 | 0.670b | 0.665b | 0.963 | 0.496b | 0.430b |

|

N-cadherin | 1.612a | 3.382b | 5.719b | 1.644b | 2.043b | 2.135b |

|

Vimentin | 1.028 | 1.226 | 1.894b | 0.975 | 1.537b | 1.628b |

|

Fibronectin | 1.390 | 1.527b | 1.945b | 1.249 | 1.353 | 1.651b |

|

CD44 | 1.551b | 1.738b | 2.034b | 1.129 | 2.208b | 2.068b |

| EMT-inducing

transcription factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Snail | 1.254 | 1.243 | 1.724b | 1.209 | 2.183b | 2.553a |

|

Slug | 1.210 | 0.835 | 0.940 | 0.935 | 0.705 | 1.080 |

|

Dlx-2 | 1.573b | 1.564b | 1.573b | 1.615b | 3.457b | 2.383b |

|

Twist1 | 1.240 | 1.080 | 1.255 | 1.150 | 1.025 | 1.270 |

|

Twist2 | 1.065 | 1.070 | 1.155 | 0.895 | 1.110 | 1.360 |

|

ZEB1 | 0.955 | 0.940 | 1.100 | 1.315 | 1.260 | 1.245 |

|

ZEB2 | 0.950 | 1.050 | 1.500 | 0.835 | 0.960 | 1.435 |

|

E12/E47 | 0.834 | 0.960 | 0.934 | 1.061 | 0.877 | 0.937 |

Dlx-2/Snail signaling is implicated in

ROS-induced glycolytic switch and inhibition of mitochondrial

respiration

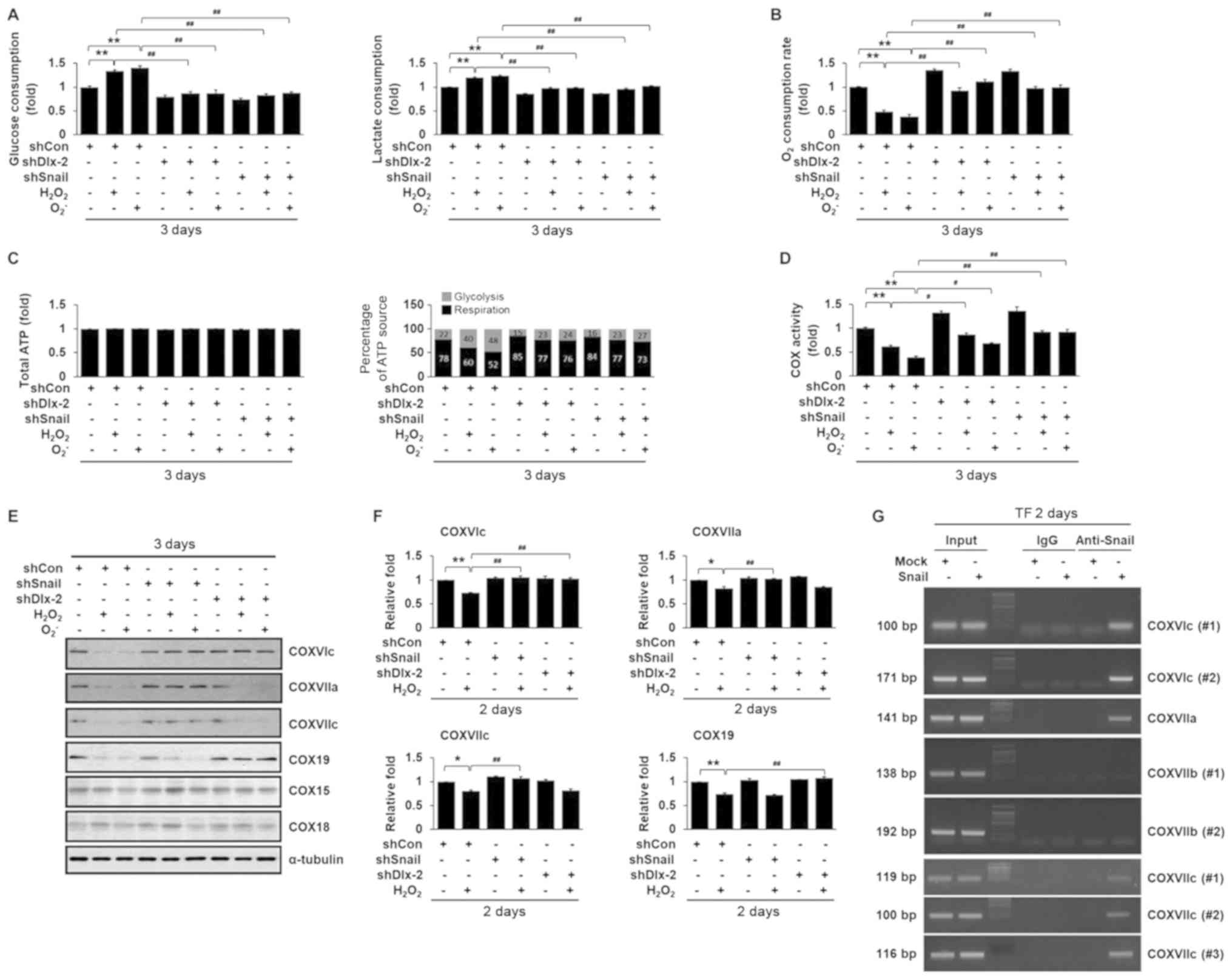

Cancer cells exhibit glycolytic switch as well as

EMT during tumor development and progression (24–28).

Thus, we examined the effects of ROS on glycolytic switch and

mitochondrial respiration. ROS significantly increased glucose

consumption and lactate production (Fig. 2A). In addition, ROS reduced

O2 consumption (Fig.

2B). Although total ATP concentrations remained the same in all

cells, ROS increased the ATP ratio produced by glycolysis versus

aerobic respiration (Fig. 2C),

indicating that ROS induced glycolytic switch. Previously, we

showed that the Dlx-2/Snail cascade induces glycolytic switch and

inhibits mitochondrial respiration (29,30).

We further examined whether the Dlx-2/Snail cascade affected

ROS-induced glycolytic switch and inhibition of mitochondrial

respiration. Dlx-2 and Snail shRNAs impaired the effects of ROS on

glucose consumption, lactate production, and O2

consumption (Fig. 2A-C),

indicating that the Dlx-2-Snail axis is involved in ROS-induced

glycolytic switch and inhibition of mitochondrial respiration.

Dlx-2/Snail signaling is implicated in

ROS-induced COX activity repression

Inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory activity is

closely related to changes in the activity of COX, the terminal

enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. We found that ROS

repressed COX activity (Fig. 2D).

Thus, we further examined the involvement of the Dlx-2/Snail

cascade in ROS-induced downregulation of COX activity. Dlx-2 and

Snail shRNAs suppressed ROS-induced downregulation of COX activity

(Fig. 2D), implicating the

Dlx-2/Snail cascade in ROS-induced COX activity repression.

Dlx-2/Snail signaling is implicated in

ROS-induced COX activity repression by downregulating multiple COX

subunits and assembly factors

Eukaryotic COX is composed of 13 different subunits

in the inner mitochondrial membrane and the sequential action of

several assembly factors regulates its assembly (Table II). We further examined the

effects of ROS on the expression of COX subunits and assembly

factors. ROS downregulated the expression of COXVIc, COXVIIa,

COXVIIc, COX15, COX18, and COX19 (Table II). Note that ROS decreased the

mRNA levels of COX15 and COX18, but not their protein levels

(Fig. 2E and F; Table II). We previously found that Snail

decreased expression of COXVIc, COXVIIa, and COXVIIc (23) and Dlx-2 decreased expression of

COXVIc and COX19 (29). Snail

shRNA suppressed the ROS-induced reduction in the levels of COXVIc,

COXVIIa, and COXVIIc, but not COX19 (Fig. 2E and F). Dlx-2 shRNA suppressed the

ROS-induced reduction in the levels of COXVIc and COX19, but not

COXVIIa and COXVIIc (Fig. 2E and

F).

| Table II.Regulation of gene expression of COX

subunits and assembly factors by ROS. |

Table II.

Regulation of gene expression of COX

subunits and assembly factors by ROS.

|

|

H2O2 (n=2-3) |

O2− (n=4) |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Genes | 48 h | 48 h |

|---|

| COX subunits |

|

COXIV | 1.067 | 1.138 |

|

COXVa | 1.047 | 1.018 |

|

COXVb | 0.978 | 1.214 |

|

COXVIa | 1.021 | 1.047 |

|

COXVIb | 0.853 | 1.425 |

|

COXVIc | 0.728b | 0.704b |

|

COXVIIa | 0.826b | 0.431b |

|

COXVIIb | 1.188 | 1.045 |

|

COXVIIc | 0.804a | 0.778b |

|

COXVIII | 1.072 | 1.053 |

| Assembly

factors |

|

COX10 | 0.942 | 0.918 |

|

COX11 | 1.103 | 1.028 |

|

COX15 | 0.776a | 0.653b |

|

COX17 | 1.016 | 0.939 |

|

COX18 | 0.836a | 0.865b |

|

COX19 | 0.742b | 0.849b |

|

LRPPRC | 1.139 | 1.051 |

|

SURF1 | 0.773 | 1.274 |

|

SCO1 | 1.036 | 1.170 |

|

SCO2 | 1.058 | 1.055 |

Several Snail-binding sites (E-box)

were previously found in the promoters of COX subunits (23)

To examine whether the expression of the COX

subunits was regulated by Snail, we conducted a ChIP assay. Snail

bound to the COXVIc, COXVIIa, and COXVIIc promoters (Fig. 2G), which is consistent with

previous observations (23). Among

the COX subunits, COXVIc acted as a common target of ROS, Dlx-2,

and Snail. Therefore, COXVIc may play an important role in the

repression of COX activity via the ROS-Dlx-2/Snail-mediated

pathway. For judging the transformation of the proteome accurately,

the proteome needs to be analyzed by mass spectrometry-based

methods, such as liquid chromatography time-of-flight mass

spectrometry (LC-TOF-MS), ultra-performance liquid chromatography

triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (UPLC-TQ-MS), and gas

chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOF-MS),

together with bioinformatics analyses (45,46).

Thus, proteome transformation is yet to be examined in further

studies, but cumulatively, our findings suggest that the

ROS-Dlx-2/Snail axis plays a crucial role in breast tumor

progression by regulating EMT, mitochondrial repression, and

glycolytic switch.

NF-κB has been shown to be involved in

ROS-induced EMT (13)

NF-κB induces EMT-inducing transcription factors

such as Snail, Slug, ZEB1, ZEB2, and Twist; NF-κB/p65

transcriptionally regulates the expression of these transcription

factors, which in turn represses the epithelial marker E-cadherin

and activates the mesenchymal marker N-cadherin, thereby resulting

in the induction of EMT (47–49).

Additionally, NF-κB stimulates the expression of HIF-1α, also

contributing to EMT (48).

Furthermore, NF-κB activation induces matrix-degrading enzymes such

as MMP9, thus contributing to EMT (50). NF-κB is known to be involved in

ROS-induced EMT via Snail induction (13). Because we found that ROS induce EMT

through the Dlx-2/Snail cascade, we think that an interplay between

NF-κB and Dlx-2 may possibly exist for Snail activation in

ROS-induced EMT; this interplay between NF-κB and Dlx-2 is yet to

be elucidated in further studies.

It has been shown that ROS are

involved in many aspects of cellular signaling

TGF-β1 has been shown to activate the ROS-NFκB

pathway, which plays an important role in TGF-β1-induced EMT, cell

migration, and invasion (51). We

have also shown that Dlx-2/Snail signaling is involved in

TGF-β-induced EMT (29,30). Thus, the ROS-Dlx-2/Snail cascade

may be involved in TGF-β-induced EMT. In addition, it was recently

reported that ROS are involved in EMT and cancer metastasis induced

by chemotherapeutics, such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), gemcitabine

(GEM), and oxaliplatin (52–54).

EMT contributes to chemoresistance in cancer cells. Dual oxidase 2

(DUOX2)-induced ROS promote the induction of EMT in 5-FU-resistant

colon cancer cells (52). In

addition, in GEM-treated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

patients, the levels of glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx1), an

antioxidant enzyme, are negatively regulated. GPx1 inhibits

ROS-mediated Akt/GSK3β/Snail signaling, thereby suppressing EMT and

chemoresistance in PDAC (53). ROS

have been shown to mediate oxaliplatin-induced EMT and invasive

potential in colon cancer (54).

Our results suggest that ROS-induced Dlx-2/Snail signaling may be

involved in EMT and may be induced by these chemotherapeutics. Note

that we used only one cell line in this study, thus our results are

limited to MCF-7 cells. Therefore, the Dlx-2/Snail axis is a

potential therapeutic target for the prevention of metastasis and

tumor progression in MCF-7 cells; this mechanism may be the case

for breast cancer in general.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research

Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government

(MSIP) (grant nos. 2015M2B2A9028108, 2015R1A2A2A01004468,

2017R1A2B4010411 and 2017R1A6A3A11030673).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

SYL, MKJ, HMJ and HSK conceived and designed the

project. SYL, MKJ and HMJ performed the experiments. SYL, MKJ, HMJ,

CHK, HGP, SIH, YJL and HSK analyzed and interpreted the data. SYL,

MKJ, HMJ, YJL and HSK wrote the manuscript. HSK supervised the

project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Storz P: Reactive oxygen species in tumor

progression. Front Biosci. 10:1881–1896. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liou GY and Storz P: Reactive oxygen

species in cancer. Free Radic Res. 44:479–496. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Schieber M and Chandel NS: ROS function in

redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 24:R453–R462.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mittler R: ROS Are Good. Trends Plant Sci.

22:11–19. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Di Meo S, Reed TT, Venditti P and Victor

VM: Harmful and beneficial role of ROS. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2016:79091862016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wu WS: The signaling mechanism of ROS in

tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 25:695–705. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

de Sá, Junior PL, Câmara DAD, Porcacchia

AS, Fonseca PMM, Jorge SD, Araldi RP and Ferreira AK: The roles of

ROS in cancer heterogeneity and therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2017:24679402017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zorov DB, Juhaszova M and Sollott SJ:

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS

release. Physiol Rev. 94:909–950. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Han D, Williams E and Cadenas E:

Mitochondrial respiratory chain-dependent generation of superoxide

anion and its release into the intermembrane space. Biochem J.

353:411–416. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Burdon RH: Superoxide and hydrogen

peroxide in relation to mammalian cell proliferation. Free Radic

Biol Med. 18:775–794. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cannito S, Novo E, di Bonzo LV, Busletta

C, Colombatto S and Parola M: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition:

from molecular mechanisms, redox regulation to implications in

human health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 12:1383–1430.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pani G, Giannoni E, Galeotti T and

Chiarugi P: Redox-based escape mechanism from death: the cancer

lesson. Antioxid Redox Signal. 11:2791–2806. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cichon MA and Radisky DC: ROS-induced

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mammary epithelial cells is

mediated by NF-kB-dependent activation of Snail. Oncotarget.

5:2827–2838. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lim SO, Gu JM, Kim MS, Kim HS, Park YN,

Park CK, Cho JW, Park YM and Jung G: Epigenetic changes induced by

reactive oxygen species in hepatocellular carcinoma: methylation of

the E-cadherin promoter. Gastroenterology. 135:2128–2140, 2140

e2121-2128. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

De Craene B and Berx G: Regulatory

networks defining EMT during cancer initiation and progression. Nat

Rev Cancer. 13:97–110. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tsai JH and Yang J: Epithelial-mesenchymal

plasticity in carcinoma metastasis. Genes Dev. 27:2192–2206. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Puisieux A, Brabletz T and Caramel J:

Oncogenic roles of EMT-inducing transcription factors. Nat Cell

Biol. 16:488–494. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Micalizzi DS, Farabaugh SM and Ford HL:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: Parallels between

normal development and tumor progression. J Mammary Gland Biol

Neoplasia. 15:117–134. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Iwatsuki M, Mimori K, Yokobori T, Ishi H,

Beppu T, Nakamori S, Baba H and Mori M: Epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in cancer development and its clinical significance.

Cancer Sci. 101:293–299. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Peinado H, Olmeda D and Cano A: Snail, Zeb

and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the

epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 7:415–428. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang Y, Shi J, Chai K, Ying X and Zhou BP:

The role of snail in EMT and tumorigenesis. Curr Cancer Drug

Targets. 13:963–972. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

De Craene B, Denecker G, Vermassen P,

Taminau J, Mauch C, Derore A, Jonkers J, Fuchs E and Berx G:

Epidermal snail expression drives skin cancer initiation and

progression through enhanced cytoprotection, epidermal

stem/progenitor cell expansion and enhanced metastatic potential.

Cell Death Differ. 21:310–320. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lee SY, Jeon HM, Ju MK, Kim CH, Yoon G,

Han SI, Park HG and Kang HS: Wnt/Snail signaling regulates

cytochrome C oxidase and glucose metabolism. Cancer Res.

72:3607–3617. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Warburg O: On the origin of cancer cells.

Science. 123:309–314. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hsu PP and Sabatini DM: Cancer cell

metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell. 134:703–707. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC and Thompson

CB: Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of

cell proliferation. Science. 324:1029–1033. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cairns RA, Harris IS and Mak TW:

Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 11:85–95.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Finley LW, Zhang J, Ye J, Ward PS and

Thompson CB: SnapShot: cancer metabolism pathways. Cell Metab.

17:466, e462. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lee SY, Jeon HM, Ju MK, Jeong EK, Kim CH,

Yoo MA, Park HG, Han SI and Kang HS: Dlx-2 is implicated in TGF-β-

and Wnt-induced epithelial-mesenchymal, glycolytic switch, and

mitochondrial repression by Snail activation. Int J Oncol.

46:1768–1780. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lee SY, Jeon HM, Ju MK, Jeong EK, Kim CH,

Park HG, Han SI and Kang HS: Dlx-2 and glutaminase upregulate

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and glycolytic switch.

Oncotarget. 7:7925–7939. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Merlo GR, Zerega B, Paleari L, Trombino S,

Mantero S and Levi G: Multiple functions of Dlx genes. Int J Dev

Biol. 44:619–626. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Panganiban G and Rubenstein JL:

Developmental functions of the Distal-less/Dlx homeobox genes.

Development. 129:4371–4386. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lee SY, Jeon HM, Kim CH, Ju MK, Bae HS,

Park HG, Lim SC, Han SI and Kang HS: Homeobox gene Dlx-2 is

implicated in metabolic stress-induced necrosis. Mol Cancer.

10:1132011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yilmaz M, Maass D, Tiwari N, Waldmeier L,

Schmidt P, Lehembre F and Christofori G: Transcription factor Dlx2

protects from TGFβ-induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. EMBO J.

30:4489–4499. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tang P, Huang H, Chang J, Zhao GF, Lu ML

and Wang Y: Increased expression of DLX2 correlates with advanced

stage of gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol.

19:2697–2703. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yan ZH, Bao ZS, Yan W, Liu YW, Zhang CB,

Wang HJ, Feng Y, Wang YZ, Zhang W, You G, et al: Upregulation of

DLX2 confers a poor prognosis in glioblastoma patients by inducing

a proliferative phenotype. Curr Mol Med. 13:438–445. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kim CH, Jeon HM, Lee SY, Ju MK, Moon JY,

Park HG, Yoo MA, Choi BT, Yook JI, Lim SC, et al: Implication of

snail in metabolic stress-induced necrosis. PLoS One. 6:e180002011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yoon YS, Lee JH, Hwang SC, Choi KS and

Yoon G: TGF beta1 induces prolonged mitochondrial ROS generation

through decreased complex IV activity with senescent arrest in

Mv1Lu cells. Oncogene. 24:1895–1903. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sariban-Sohraby S, Magrath IT and Balaban

RS: Comparison of energy metabolism in human normal and neoplastic

(Burkitt's lymphoma) lymphoid cells. Cancer Res. 43:4662–4664.

1983.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dong C, Yuan T, Wu Y, Wang Y, Fan TW,

Miriyala S, Lin Y, Yao J, Shi J, Kang T, et al: Loss of FBP1 by

Snail-mediated repression provides metabolic advantages in

basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 23:316–331. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Jin L, Zhu C, Wang X, Li C, Cao C, Yuan J

and Li S: Urocortin attenuates TGFβ1-induced Snail1 and slug

expressions: inhibitory role of Smad7 in Smad2/3 signaling in

breast cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 116:2494–2503. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Rios Garcia M, Steinbauer B, Srivastava K,

Singhal M, Mattijssen F, Maida A, Christian S, Hess-Stumpp H,

Augustin HG, et al: Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1-dependent protein

acetylation controls breast cancer metastasis and recurrence. Cell

Metab. 26:842–855, e845. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Xu H, Tian Y, Yuan X, Wu H, Liu Q, Pestell

RG and Wu K: The role of CD44 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition

and cancer development. Onco Targets Ther. 8:3783–3792.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chanmee T, Ontong P, Kimata K and Itano N:

Key roles of hyaluronan and Its CD44 receptor in the stemness and

survival of cancer stem cells. Front Oncol. 5:1802015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Han X, Aslanian A and Yates JR III: Mass

spectrometry for proteomics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 12:483–490. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Dettmer K, Aronov PA and Hammock BD: Mass

spectrometry-based metabolomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 26:51–78. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Min C, Eddy SF, Sherr DH and Sonenshein

GE: NF-kappaB and epithelial to mesenchymal transition of cancer. J

Cell Biochem. 104:733–744. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Taniguchi K and Karin M: NF-κB,

inflammation, immunity and cancer: Coming of age. Nat Rev Immunol.

18:309–324. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Pires BR, Mencalha AL, Ferreira GM, de

Souza WF, Morgado-Díaz JA, Maia AM, Corrêa S and Abdelhay ES:

NF-kappaB is involved in the regulation of EMT genes in breast

cancer cells. PLoS One. 12:e01696222017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Huang S, Pettaway CA, Uehara H, Bucana CD

and Fidler IJ: Blockade of NF-kappaB activity in human prostate

cancer cells is associated with suppression of angiogenesis,

invasion, and metastasis. Oncogene. 20:4188–4197. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Tobar N, Villar V and Santibanez JF:

ROS-NFkappaB mediates TGF-beta1-induced expression of

urokinase-type plasminogen activator, matrix metalloproteinase-9

and cell invasion. Mol Cell Biochem. 340:195–202. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kang KA, Ryu YS, Piao MJ, Shilnikova K,

Kang HK, Yi JM, Boulanger M, Paolillo R, Bossis G, Yoon SY, et al:

DUOX2-mediated production of reactive oxygen species induces

epithelial mesenchymal transition in 5-fluorouracil resistant human

colon cancer cells. Redox Biol. 17:224–235. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Meng Q, Shi S, Liang C, Liang D, Hua J,

Zhang B, Xu J and Yu X: Abrogation of glutathione peroxidase-1

drives EMT and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer by activating

ROS-mediated Akt/GSK3β/Snail signaling. Oncogene. 37:5843–5857.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Jiao L, Li DD, Yang CL, Peng RQ, Guo YQ,

Zhang XS and Zhu XF: Reactive oxygen species mediate

oxaliplatin-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasive

potential in colon cancer. Tumour Biol. 37:8413–8423. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|