Introduction

Osteoporosis, which is characterized by low bone

mass and microarchitectural deterioration of the bone tissue, is a

significant public health issue (1-3).

Therefore, it has received extensive attention. With the global

trend of population aging, the incidence of osteoporosis is

increasing (1,2). The prevalence of osteoporosis in the

elderly population in China is ~36% (4). Fractures, which can lead to chronic

pain, disability, depression and other associated diseases, are the

most serious complication of osteoporosis (3,5).

Therefore, identifying novel biomarkers for predicting individuals

at risk of osteoporosis is of great importance for the early

intervention to prevent fractures.

Human bone metabolism is a complex process that

involves bone absorption mediated by osteoclasts and

osteoblast-mediated bone formation (6). Bone absorption and formation are

stable under physiological conditions. However, disruption of this

balance, which can lead to impaired osteoblast and osteoclast

activities, can result in osteoporosis (7).

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), which

were first isolated from bone marrow and named by Friedenstein

et al (8) in 1976, are

closely associated with the occurrence and development of

osteoporosis. Abnormal BMSC differentiation, proliferation and

senescence are the most common causes of osteoporosis (9). BMSCs are normally differentiate into

osteoblasts, chondrocytes and adipocytes, while their

differentiation can be affected by several factors, including age

(10) and intracellular biological

factors (11). When only a few

BMSCs differentiate into osteoblasts, which in turn results in

reduced bone formation, osteoporosis can occur (11,12).

Furthermore, it has been reported that BMSC senescence is regulated

by several factors, such as DNA damage, oxidative stress and

mitogenic signals (13,14). Therefore, emerging evidence has

suggested that BMSC senescence plays a significant role in the

occurrence of osteoporosis (15,16).

Although circular RNAs (circRNAs/circ) are

classified as non-coding RNAs, several of them exert protein-coding

potential (17,18). Owing to their loop structure,

without 3' and 5' ends, circRNAs are more stable compared with

linear RNAs and less prone to degradation by exonucleases (4,19). In

addition, previous studies indicated that circRNAs, possessing

numerous miRNA binding sites, could act as competing endogenous

RNAs (ceRNAs) via sponging microRNAs (miRNAs), thus playing an

essential regulatory role in the progression of several diseases,

including osteoporosis (19-21).

For example, a study revealed that circ_0001052 was involved in the

regulation of BMSC differentiation and the pathogenesis of

osteoporosis via acting as ceRNA through sponging miR-124-3p

(22). In addition, circRNA_0048211

could protect against postmenopausal osteoporosis via targeting

miRNA-93-5p (23). Furthermore, an

increasing number of evidence has indicated that circRNA-miRNA-mRNA

networks serve a regulatory role in osteoporosis (21,23). A

previous study from our laboratory demonstrated that

hsa_circ_0122913 was upregulated in the peripheral blood of

patients with senile osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture

(24). However, the effect of

hsa_circ_0122913 on the proliferation and osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs has not been previously investigated.

Furthermore, a previous study also showed that icariin exerted

beneficial effects on the skeletal system in vitro,

including the enhancement of the osteogenic differentiation and

proliferation of BMSCs (25).

However, whether circRNAs are involved in the mechanisms underlying

the protective effects of icariin remains elusive. Therefore, the

present study aimed to explore the role of hsa_circ_0122913 in the

proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, and whether

it could be involved in the protective effects of icariin on the

skeletal system. Overall, the results of the current study could

provide novel insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms

underlying the onset of osteoporosis and could potentially pave the

way for the development of therapeutic interventions.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

The human BMSC cell line (cat. no. HUXMA-01001,

passage 2 upon receipt) was obtained from Cyagen Biosciences Inc.

and cultured in BMSCs growth medium (Cyagen Biosciences, Inc.) at

37˚C in an incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were then

treated with 1x10-6 mol/l icariin (Shanghai Yuanye

Bio-Technology, Co., Ltd.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Following culture and treatment with the indicated

compounds, BMSCs were collected, and total RNA was then isolated

using the Total RNA Rapid Extraction Kit (cat. no. GK3016; Generay

Biotech Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, total RNA was reverse transcribed

into cDNA using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (cat. no. R222-01;

Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) strictly according to the manufacturer's

protocols. qPCR was performed using the ChamQ SYBR Color qPCR

Master Mix Kit (cat. no. Q411-02; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) on the

CFX Connect Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The

thermocycling protocol included an initial denaturation step at

95.0˚C for 30 sec followed by 40 cycles consisting of 95.0˚C for 10

sec and 60.0˚C for 30 sec, with a final melt curve analysis

performed from 70˚C to 95˚C using 0.5˚C increments and 5-sec holds

at each temperature step. The expression levels of target genes

were normalized to β-actin as the housekeeping gene, and relative

gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method

(26). The primer sequences used

for PCR are listed in Table I.

| Table ISequences of primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I

Sequences of primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene name | Primer sequence

(5'-3') |

|---|

| Actin | F:

TGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG |

| | R:

CTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAG |

| Osteopontin | F:

GAAGTTTCGCAGACCTGACAT |

| | R:

GTATGCACCATTCAACTCCTCG |

| Osterix | F:

GTGGAACAGGAGTGGAGCTG |

| | R:

AGGCAGATGGAGAGAGCTGG |

| Runt-related

transcription factor 2 | F:

CGCCTCACAAACAACCACAG |

| | R:

ACTGCTTGCAGCCTTAAATGAC |

| Defective in cullin

neddylation 1 domain containing 1 | F:

TGCCTACTGGAACTTAGTGCT |

| | R:

CTGCAATCATCGTACTGAAGTCT |

Alizarin red staining

BMSCs at a density of 6x104 cells/well

were seeded into 12-well culture plates and cultured for 7 days.

Subsequently, the medium was discarded and BMSCs were washed twice

with PBS. Cells were then fixed with 2 ml 4% formaldehyde at room

temperature for 30 min, followed by washing twice with PBS.

Subsequently, BMSCs were stained with alizarin red solution (cat.

no. G3280; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for

5 min. Following washing with PBS for two times, images of the

stained cells were captured under a fluorescent inverted microscope

(cat. no. IX73; Olympus Corporation) at a magnification of x200 and

a scale bar of 50 µm.

Osteogenic differentiation assay

The differentiation potential of osteocytes was

verified using a differentiation assay. Briefly, BMSCs at a density

of 6x104 cells/well were seeded into 12-well culture

plates and differentiated in osteogenic medium containing alizarin

red staining solution (Cyagen Biosciences, Inc.), according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from BMSCs using a

Cell Lysis Buffer for Western and IP (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) supplemented with 1 mM phenyl-methyl-sulfonyl

fluoride (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Subsequently, the

protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic protein

assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The protein

extracts were then separated by 10% sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, with 30 µg of protein

loaded per lane, followed by transferring onto polyvinylidene

fluoride membranes (MilliporeSigma). Following blocking with 5%

fat-free milk at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were

incubated with primary antibodies at 4˚C overnight, followed by

washing with Tris-buffer saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST)

for three times for 10 min each. Subsequently, the membranes were

incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies at room

temperature for 1 h and washed again with TBST. The protein bands

were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) and images were captured using an

automatic chemiluminescence imaging analysis system (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The densitometric analysis of the protein

bands was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.4.3.67;

National Institutes of Health). The primary antibodies used against

defective in cullin neddylation 1 domain containing 1 (DCUN1D1;

cat. no. ab181233; 1:5,000), osterix (OSX; cat. no. ab209484;

1:1,000), runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2; cat. no.

ab236639; 1:1,000) and osteopontin (OPN; cat. no. ab214050;

1:1,000) were all purchased from Abcam. The anti-β-actin primary

antibody (cat. no. ab008; 1:5,000) was obtained from Hangzhou

MultiSciences (Lianke) Biotech Co., Ltd. The corresponding

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, including goat

anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. GAM007, 1:5,000) and goat anti-rabbit IgG

(cat. no. GAR0072, 1:5,000), were also obtained from Hangzhou

MultiSciences (Lianke) Biotech Co., Ltd.

Annexin V-APC/7-AAD assay

Cell apoptosis was assessed using an Annexin

V-APC/7-AAD apoptosis kit [Hangzhou MultiSciences (Lianke) Biotech

Co., Ltd.]. Briefly, cells were collected after trypsinization

without EDTA at 48 and 72 h, and 7 days of cell proliferation,

followed by washing twice with PBS. The cells were resuspended in

binding buffer with Annexin V-APC (5 µl/tube) and 7-AAD (10

µl/tube) and incubated in the dark at 4˚C for 5 min. Finally, cells

were analyzed using a BD Accuri™ C6 Plus flow cytometer

(BD Biosciences) and the corresponding supporting BD Accuri C6

software.

Cell transfection

For silencing experiments, viral particles

encompassing short hairpin (sh)RNAs targeting hsa_circ_0122913 and

DCUN1D1, and their corresponding negative control (NC) shRNAs were

purchased from Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. For transfection,

BMSCs at a density of 4x104 cells/well were seeded into

12-well plates. When the cell confluence reached 50%, the culture

medium was replaced with fresh medium containing viral particles at

multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 50 or 100. The viral titer for

all constructs was 2x108 TU/ml, with volumes of 10 µl

(MOI=50) or 20 µl (MOI=100) added per well. Polybrene was included

at a 1:1,000 dilution to enhance transduction efficiency. The viral

particles were incubated with the cells for 6 h at 37˚C and 5%

CO2. Following the incubation, the transfection medium

was replaced with fresh complete culture medium and the cells were

cultured for 48 h before collection for further analysis. The shRNA

sequences are listed in Table

II.

| Table IISequences of shRNAs. |

Table II

Sequences of shRNAs.

| Name of shRNA | Strand (5'-3') |

|---|

| DCUN1D1 | Sense:

GATCCGTACGATGATTGCAGATGACTCGAGTCATCTGCAATCATCGTACTTTTTTG |

| | Antisense:

AATTCAAAAAAGTACGATGATTGCAGATGACTCGAGTCATCTGCAATCATC

GTACG |

|

hsa_circ-0122913 | Sense:

GATCCGATGAAGAAGAACAAGTTGCTCGAGCAACTTGTTCTTCTTCATCTTTTTTG |

| | Antisense:

AATTCAAAAAAGATGAAGAAGAACAAGTTGCTCGAGCAACTTGTTCTTCTTCATCG |

| Negative

control | Sense:

GATCCGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTAATTCAAGAGATTACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAATTTTTTC |

| | Antisense:

AATTGAAAAAATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTAATCTCTTGAATTACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACG |

Cell counting kit 8 (CCK-8) assay

The cultured BMSCs were reaped and seeded into

96-well plates (density, 8x103 cells/well), followed by

incubation in an incubator at 37˚C with 5% CO2. Cell

proliferation at 24, 48 and 72 h, as well as 7 days after treatment

was assessed using a CCK-8 Assay kit [Hangzhou MultiSciences

(Lianke) Biotech Co., Ltd.]. Briefly, after removing the

supernatants, each well was supplemented with 10 µl CCK-8 solution

and cells were incubated at 37˚C in the dark for 1 h. The

absorbance in each well at wavelengths of 450 and 650 nm was

measured using a microplate reader (SpectraMAX Plus; Molecular

Devices, LLC.).

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

Bioinformatics analysis using the CircBank database

(http://www.circbank.cn/) was carried out to

predict whether hsa_circ_0122913 could encompass a biding site for

microRNA (miR)-501-5p. MiR-501-5p mimic and the corresponding NC

mimic were synthesized by Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd. The sense

sequence of the miR-501-5p mimic is: 5'-AAUCCUUUGUCCCUGGGUGAGA-3'

and the antisense sequence is: 5'-UCUACCCAGGGACAAAGGAUU-3'. The

sense sequence of the NC mimic is: 5'-UUUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3',

and the antisense sequence is: 5'-AAACAUGAUGUGUUUUCAUGAC-3'. The

reporter plasmids used in the experiment were the

pmirGLO-hsa-circ-0122913-WT and pmirGLO-hsa-circ-0122913-MUT

plasmids, synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. For the

transfection experiments, 293T cells, which were obtained from

Chinese National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, at ~80%

confluency in 24-well plates were co-transfected with 20 pmol of

miRNA mimics and 500 ng of reporter plasmids using Lipofectamine

3000 transfection reagent (cat. no. L3000150; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The interaction between miR-501-5p and

hsa_circ_0122913 was verified using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter

Assay System (Promega Corporation), with Firefly luciferase

activity normalized to Renilla luciferase activity,

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data were obtained from at least

three biological replicates and are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation. All analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics). For comparisons

between two groups, independent unpaired t-tests were used. For

multiple group comparisons, one-way ANOVA was performed, followed

by Tukey's post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

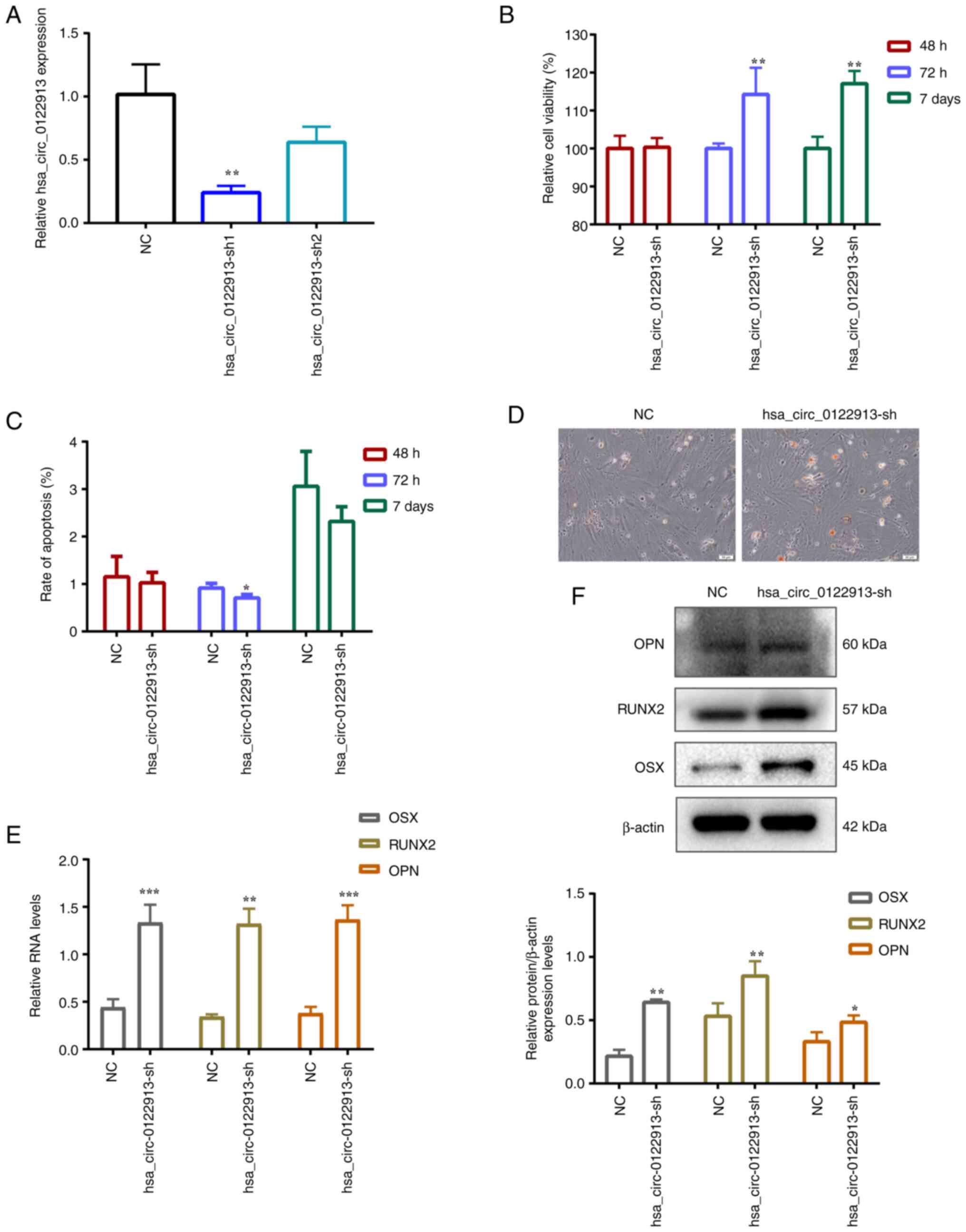

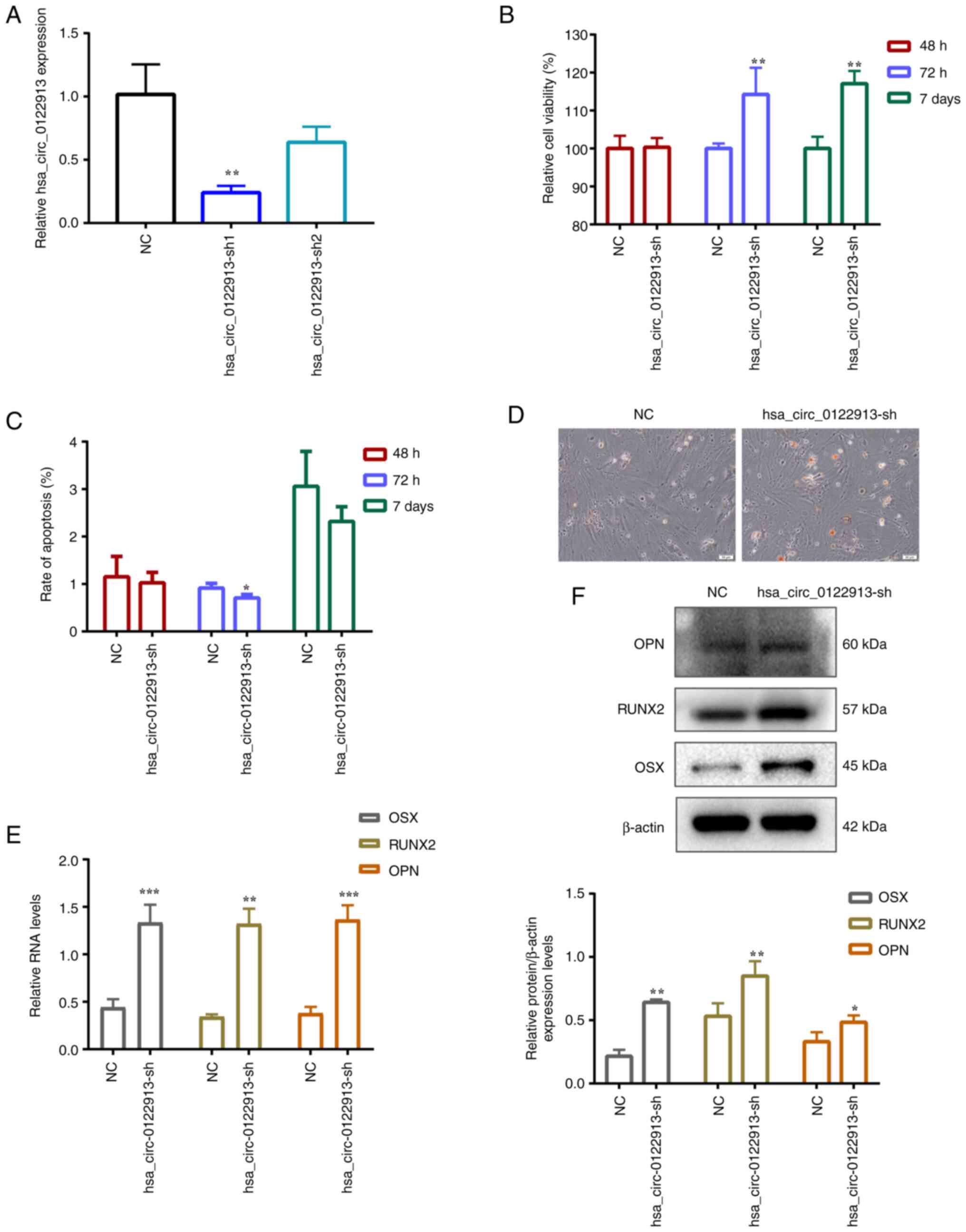

Hsa_circ_0122913 suppresses the

proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in vitro

To investigate the effect of hsa_circ_0122913 on the

proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs,

hsa_circ_0122913 was silenced in BMSCs using the corresponding

shRNAs. Therefore, the RT-qPCR results showed that

sh-circ_0122913-1 significantly decreased the expression levels of

hsa_circ_0122913 in BMSCs. Therefore, hsa_circ_0122913-sh1 was used

in the subsequent experiments (Fig.

1A). Additionally, CCK-8 assays (Fig. 1B) and flow cytometric analysis

(Figs. 1C and S1) demonstrated that hsa_circ_0122913

silencing improved the viability and reduced the apoptosis of BMSCs

at 72 h and 7 days compared with the NC group. However, no

difference was observed at 48 h. Furthermore, the role of

hsa_circ_0122913 in the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs was

assessed using alizarin red S staining, RT-qPCR and western blot

analysis. Alizarin staining demonstrated that hsa_circ_0122913

knockdown could significantly enhance the osteogenic

differentiation ability of BMSCs on day 7 compared with the control

group (Fig. 1D). In addition, the

RT-qPCR and western blot results revealed that hsa_circ_0122913

silencing could increase the expression levels of several

significant osteoblast differentiation-related markers, including

those of OSX, RUNX2 and OPN, at both the mRNA and protein levels

(Fig. 1E and F).

| Figure 1Hsa_circ_0122913 suppresses the

proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in

vitro. (A) The expression of knocked down hsa_circ_0122913 in

BMSCs determined by RT-qPCR. (B) The cell viability of

hsa_circ_0122913 knocking-down in BMSCs after 48 h, 72 h and 7 d

determined by Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. (C) The apoptotic rate of

hsa_circ_0122913 knocking-down in BMSCs group after 48, 72 h and 7

d determined by flow cytometric analysis. (D) The osteogenic

differentiation ability after 7 days of osteogenic induction

detected by alizarin staining. (E) The mRNA expression of OSX,

RUNX2 and OPN in BMSCs after knockdown of hsa_circ_0122913 detected

by RT-qPCR. (F) The protein expression of OSX, RUNX2 and OPN in

BMSCs after knockdown of hsa_circ_0122913 detected by western blot

analysis. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. NC. BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; OSX,

osterix; RUNX2, runt-related transcription factor 2; OPN,

osteopontin; NC, negative control. |

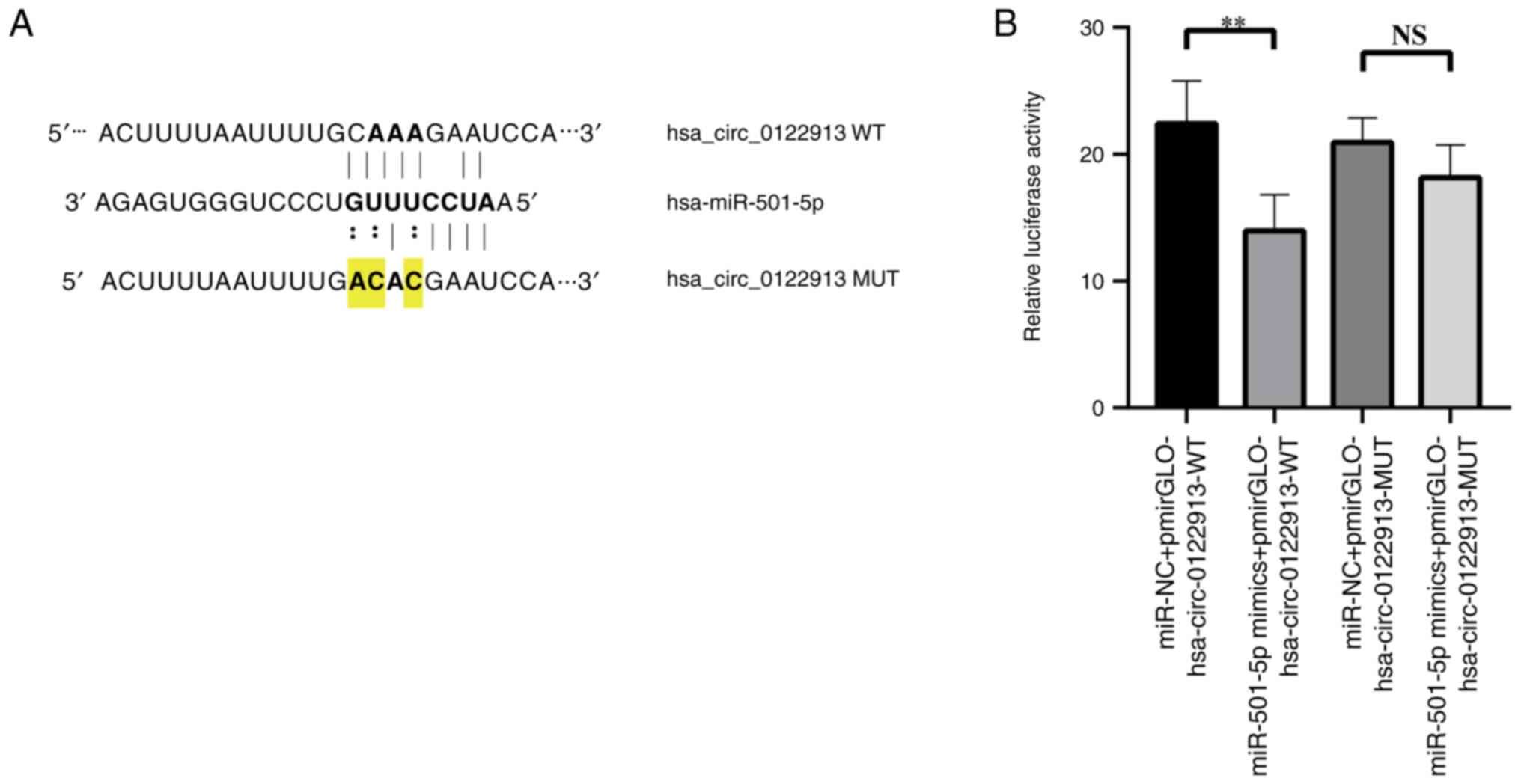

Hsa_circ_0122913 acts a ceRNA for

miR-501-5p

The aforementioned results suggested that

hsa_circ_0122913 could play a key role in the occurrence and

development of osteoporosis. Therefore, it was hypothesized that

hsa_circ_0122913 could regulate the expression levels of miRNAs via

a ceRNA network. Bioinformatics analysis predicted that

hsa_circ_0122913 encompassed a binding site for miR-501-5p

(Fig. 2A). Subsequently, a

dual-luciferase reporter assay was carried out to verify whether

hsa_circ_0122913 could sponge miR-501-5p. Therefore, wild-type (WT)

and binding motif-mutant (MUT) luciferase reporter plasmids were

constructed, namely hsa_circ_0122913-WT/MUT. Then, BMSCs were

co-transfected with miR-501-5p mimic and hsa_circ_0122913-WT/MUT

plasmids. The results indicated that compared with the vector

control group, the luciferase activity was reduced upon

co-transfection of the miR-501-5p mimic. However, transfection of

the miR-501-5p mimic had no effect on the luciferase activity of

hsa_circ_0122913-MUT, thus indicating that hsa_circ_0122913 could

sponge miR-501-5p (Fig. 2B).

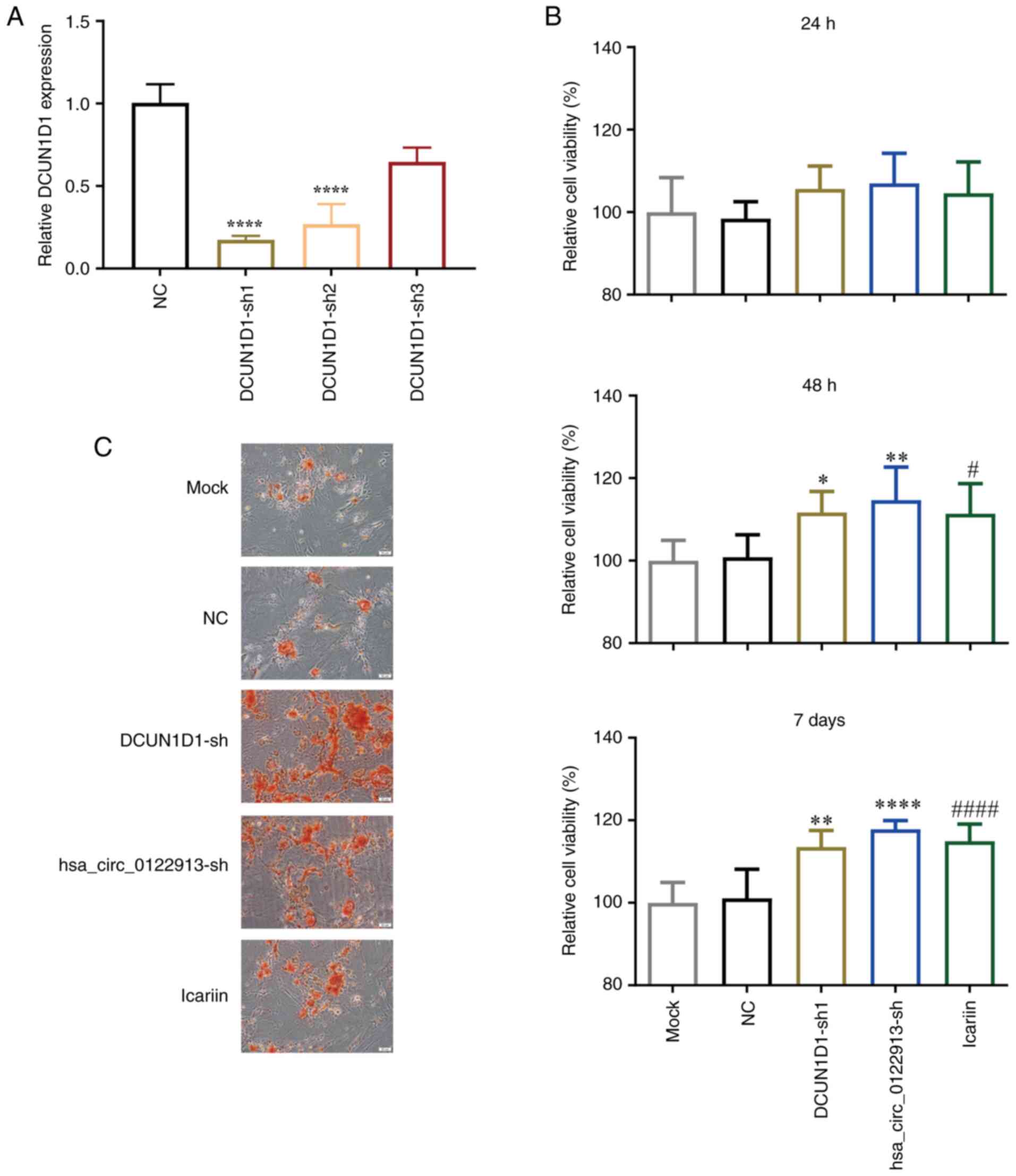

Icariin treatment and DCUN1D1

knockdown can promote the proliferation and osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs in vitro

Bioinformatics analysis using the CircBank database

predicted that DCUN1D1 could be a host gene of hsa_circ_0122913.

Therefore, shRNAs were used to knockdown DCUN1D1 in BMSCs and the

RT-qPCR results showed that DCUN1D1 expression was most

significantly decreased in BMSCs transfected with DCUN1D1-sh1

(Fig. 3A). Therefore, this

construct was used for DCUN1D1 knockdown in subsequent experiments.

The CCK-8 assay results demonstrated that both hsa_circ_0122913 and

DCUN1D1 knockdown increased cell viability compared with NC

controls, with non-significant effects at 24 h, but statistically

significant enhancement at 48 h and 7 days. Similarly, icariin

treatment showed a progressive improvement in viability compared

with mock controls, with marked increases observed at 48 h and 7

days (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the

alizarin red staining results showed that hsa_circ_0122913 and

DCUN1D1 silencing promoted the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs

to a similar extent as icariin treatment (Fig. 3C).

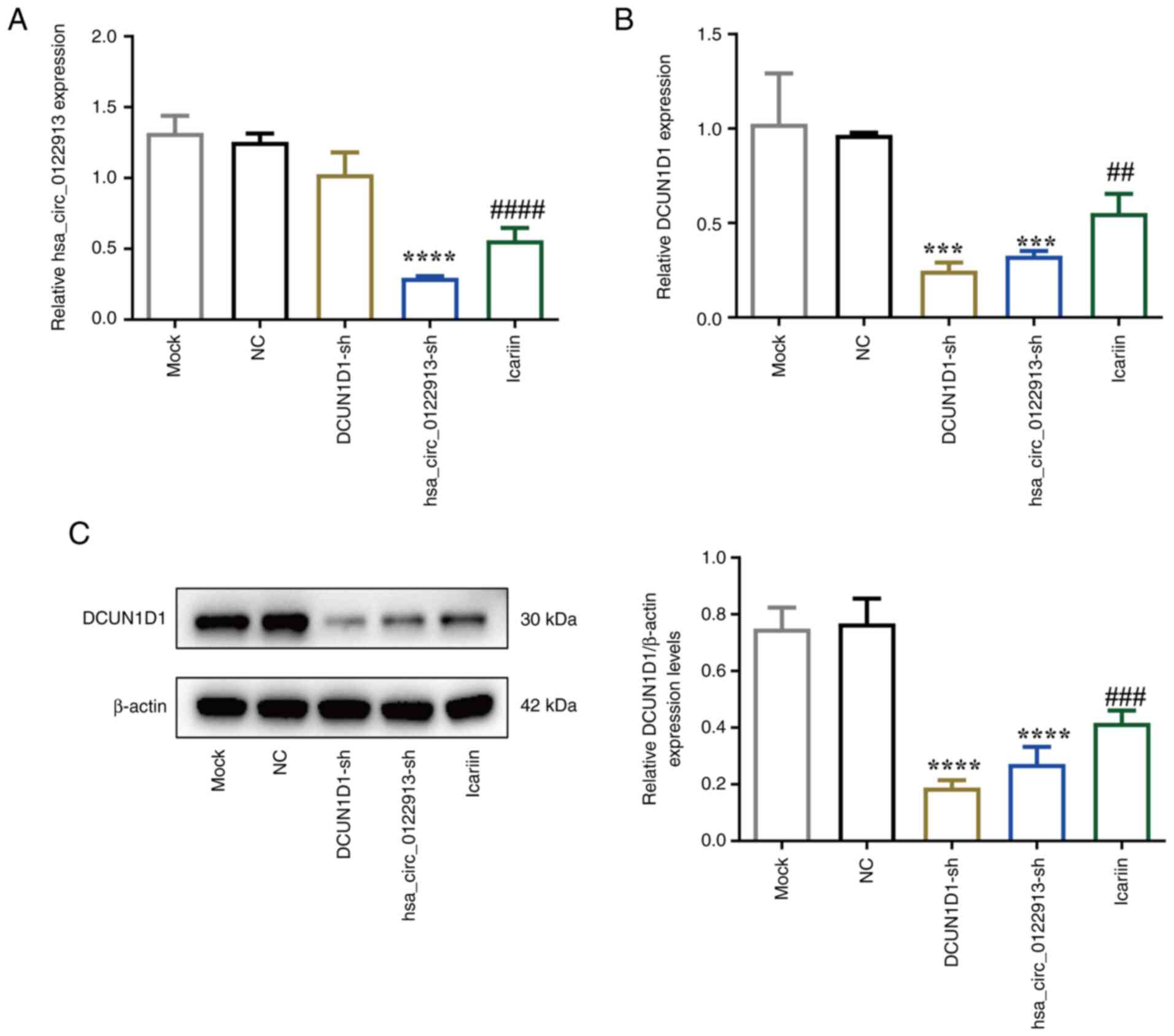

Hsa_circ_0122913/DCUN1D1 axis is

involved in the effects of icariin treatment on BMSCs

The aforementioned results suggested that the

effects of icariin on the proliferation and differentiation ability

of BMSCs were similar to those observed in circ_0122913- or

DCUN1D1-depleted BMSCs. However, no association between icariin and

the hsa_circ_0122913/DCUN1D1 pathway was obtained. Therefore,

RT-qPCR and western blot analyses were performed to verify that

icariin could suppress the mRNA expression levels of

hsa_circ_0122913 (Fig. 4A) and

those of DCUN1D1 at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 4B and C). Furthermore, hsa_circ_0122913 knockdown

significantly decreased the mRNA and protein expression levels of

DCUN1D1 in BMSCs (Fig. 4B and

C). However, DCUN1D1 silencing had

no effect on the expression levels of hsa_circ_0122913 (Fig. 4A).

Discussion

CircRNAs are a relatively new class of non-coding

RNAs that play significant roles in several biological processes.

Therefore, circRNAs are considered as potential therapeutic

biomarkers in various diseases (27,28),

such as cancer (29), Crohn's

disease (30), cardiovascular

diseases (31) and renal diseases

(32). The present study mainly

focused on the effects of hsa_circ_0122913 on the proliferation and

osteogenic differentiation capacities of BMSCs, since this circRNA

was found to be upregulated in patients with senile osteoporotic

vertebral compression fracture (24). The results showed that

hsa_circ_0122913 could reduce the viability and osteogenic

differentiation ability of BMSCs in vitro. Consistent with

previous studies, the aforementioned finding suggested that

hsa_circ_0122913 was closely associated with the occurrence and

development of osteoporosis.

CeRNA networks, where competitive non-coding RNAs

and miRNAs regulate target gene expression, are considered as a

typical mechanism of action of non-coding RNAs (28). A previous study predicted the top

five miRNAs that could regulate hsa_circ_0122913, including

miR-501-5p (24). Other studies

demonstrated that miR-501-5p could play a significant regulatory

role in several types of cancer, such as neck squamous cell

carcinoma (33) and hepatocellular

carcinoma (34). However, its role

in osteogenic differentiation has not been previously investigated.

In the present study, the results indicated that hsa_circ_0122913

could act as a sponge for miR-501-5p. However, how this ceRNA

network acts in BMSCs remains poorly understood and requires

further investigation.

The regulation of circRNA expression and its

interplay with host genes is complex and depending on context.

Indeed, emerging evidence suggests that circRNAs can regulate the

expression of host genes (35). For

instance, knockdown experiments targeting circRNAs such as

circAMOTL1(36) and

circ-ENO1(37) have demonstrated

lower expression levels of their respective host genes, paralleling

our observation that the knockdown of hsa_circ_0122913 coincided

with a downregulation of the host gene DCUN1D1. However, it is

crucial to recognize that circRNA expression can be influenced by

various factors, including cell type and tissue specificity. In

some cases, circRNA expression may not directly correlate with the

expression levels of the linear host gene, as supported by previous

research (38,39). This is consistent with our results,

where the expression level of hsa_circ_0122913 was not

significantly affected by DCUN1D1 knockdown.

Furthermore, DCUN1D1 knockdown and icariin treatment

were found to enhance the viability and osteogenic differentiation

potential of BMSCs. Additionally, the RT-qPCR and western blot

analysis results showed that icariin treatment could regulate the

expression of hsa_circ_0122913 and DCUN1D1, thus indicating that

the hsa_circ_0122913/DCUN1D1 axis could be involved in the effect

of icariin treatment on BMSCs. Previous studies demonstrated that

DCUN1D1 could serve a key role in tumor progression (40,41),

and was involved in several biological functions, including

activation of matrix metalloproteinase 2(42), regulation of CD8+ T-cell

infiltration and depigmentation (43). Notably, Shao et al (44) found that DCUN1D1 may be one of the

genes regulated by upregulated miRNAs in osteoporosis. Combining

the aforementioned previous findings with those of the current

study, it was hypothesized that the hsa_circ_0122913/DCUN1D1

signaling pathway could play a significant role in the occurrence

and development of osteoporosis.

Although the results of the present study could be

helpful in the investigation of the molecular mechanisms associated

with osteoporosis, the present study has some limitations. Firstly,

while the experimental design used in previous studies was

referenced (45,46), where scrambled shRNA was used as a

negative control, it is acknowledged that the inclusion of both

blank and positive controls will be essential in future, as well as

more in-depth studies to strengthen the experimental design and

enhance the reliability of the results. Secondly, more studies are

needed on ceRNA networks to fully explain how hsa_circ_0122913

could regulate the proliferation and differentiation of BMSCs.

Lastly, although the results demonstrated that icariin could

regulate the expression of hsa_circ_0122913 and DCUN1D1, more

studies are needed to uncover the association between the

underlying molecular mechanisms of icariin and those of the

hsa_circ_0122913/DCUN1D1 axis.

In conclusion, the results of the current study

showed that hsa_circ_0122913 could suppress the proliferation and

osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs via sponging miR-501-5p.

Furthermore, hsa_circ_0122913 and DCUN1D1 could be involved in

icariin-regulated biological events in BMSCs. Overall, the

aforementioned results could provide novel insights into the

development of new therapies for osteoporosis.

Supplementary Material

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis

in the hsa_circ_0122913-knockdown BMSC group at 48, 72 h and 7

days. BMSC, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by major scientific and

technological plan projects for social development in Xiaoshan

(grant nos. 2019212 and 2020304) and Zhejiang Traditional Chinese

medicine science and technology project (grant no. 2024ZL801).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HH designed the study. YW, ML and CL performed the

experiments and analyzed the results. YW and ML confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. YW and HH wrote the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Lane NE: Epidemiology, etiology, and

diagnosis of osteoporosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 194 (Suppl

2):S3–S11. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wang Y, Tao Y, Hyman ME, Li J and Chen Y:

Osteoporosis in China. Osteoporos Int. 20:1651–1662.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Johnston CB and Dagar M: Osteoporosis in

older adults. Med Clin North Am. 104:873–884. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ji H, Cui X, Yang Y and Zhou X: CircRNA

hsa_circ_0006215 promotes osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and

enhances osteogenesis-angiogenesis coupling by competitively

binding to miR-942-5p and regulating RUNX2 and VEGF. Aging (Albany

NY). 13:10275–10288. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Anthamatten A and Parish A: Clinical

update on osteoporosis. J Midwifery Womens Health. 64:265–275.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yang Y, Yujiao W, Fang W, Linhui Y, Ziqi

G, Zhichen W, Zirui W and Shengwang W: The roles of miRNA, lncRNA

and circRNA in the development of osteoporosis. Biol Res.

53(40)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Xiao L, Zhong M, Huang Y, Zhu J, Tang W,

Li D, Shi J, Lu A, Yang H, Geng D, et al: Puerarin alleviates

osteoporosis in the ovariectomy-induced mice by suppressing

osteoclastogenesis via inhibition of TRAF6/ROS-dependent MAPK/NF-κB

signaling pathways. Aging (Albany NY). 12:21706–21729.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Friedenstein AJ, Gorskaja JF and Kulagina

NN: . Fibroblast precursors in normal and irradiated mouse

hematopoietic organs. Exp Hematol. 4:267–274. 1976.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hu L, Yin C, Zhao F, Ali A, Ma J and Qian

A: Mesenchymal stem cells: cell fate decision to osteoblast or

adipocyte and application in osteoporosis treatment. Int J Mol Sci.

19(360)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang C, Meng H, Wang X, Zhao C, Peng J and

Wang Y: Differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in

osteoblasts and adipocytes and its role in treatment of

osteoporosis. Med Sci Monit. 22:226–233. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Qadir A, Liang S, Wu Z, Chen Z, Hu L and

Qian A: Senile osteoporosis: The involvement of differentiation and

senescence of bone marrow stromal cells. Int J Mol Sci.

21(349)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Infante A and Rodríguez CI: Osteogenesis

and aging: Lessons from mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther.

9(244)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Mattiucci D, Maurizi G, Leoni P and Poloni

A: Aging- and senescence-associated changes of mesenchymal stromal

cells in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cell Transplant. 27:754–764.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Fathi E, Charoudeh HN, Sanaat Z and

Farahzadi R: Telomere shortening as a hallmark of stem cell

senescence. Stem Cell Investig. 6(7)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Guo Y, Jia X, Cui Y, Song Y, Wang S, Geng

Y, Li R, Gao W and Fu D: Sirt3-mediated mitophagy regulates

AGEs-induced BMSCs senescence and senile osteoporosis. Redox Biol.

41(101915)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhang P, Zhang H, Lin J, Xiao T, Xu R, Fu

Y, Zhang Y, Du Y, Cheng J and Jiang H: Insulin impedes osteogenesis

of BMSCs by inhibiting autophagy and promoting premature senescence

via the TGF-β1 pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 12:2084–2100.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Chen L, Wang C, Sun H, Wang J, Liang Y,

Wang Y and Wong G: The bioinformatics toolbox for circRNA discovery

and analysis. Brief Bioinform. 22:1706–1728. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Li R, Jiang J, Shi H, Qian H, Zhang X and

Xu W: CircRNA: A rising star in gastric cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci.

77:1661–1680. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Shafabakhsh R, Mirhosseini N, Chaichian S,

Moazzami B, Mahdizadeh Z and Asemi Z: Could circRNA be a new

biomarker for pre-eclampsia? Mol Reprod Dev. 86:1773–1780.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zang J, Lu D and Xu A: The interaction of

circRNAs and RNA binding proteins: An important part of circRNA

maintenance and function. J Neurosci Res. 98:87–97. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Gao M, Zhang Z, Sun J, Li B and Li Y: The

roles of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks in the development and

treatment of osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

13(945310)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Liu N, Lu W, Qu X and Zhu C: LLLI promotes

BMSC proliferation through circRNA_0001052/miR-124-3p. Lasers Med

Sci. 37:849–856. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Qiao L, Li CG and Liu D: CircRNA_0048211

protects postmenopausal osteoporosis through targeting miRNA-93-5p

to regulate BMP2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 24:3459–3466.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yao X, Liu M, Jin F and Zhu Z:

Comprehensive analysis of differentially expressed circular RNAs in

patients with senile osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture.

Biomed Res Int. 2020(4951251)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wu Y, Xia L, Zhou Y, Xu Y and Jiang X:

Icariin induces osteogenic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem

cells in a MAPK-dependent manner. Cell Prolif. 48:375–384.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: . Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yu L and Liu Y: circRNA_0016624 could

sponge miR-98 to regulate BMP2 expression in postmenopausal

osteoporosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 516:546–550.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Chia W, Liu J, Huang YG and Zhang C: A

circular RNA derived from DAB1 promotes cell proliferation and

osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs via RBPJ/DAB1 axis. Cell Death

Dis. 11(372)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gao Y, Shang S, Guo S, Li X, Zhou H, Liu

H, Sun Y, Wang J, Wang P, Zhi H, et al: Lnc2Cancer 3.0: An updated

resource for experimentally supported lncRNA/circRNA cancer

associations and web tools based on RNA-seq and scRNA-seq data.

Nucleic Acids Res. 49:D1251–D1258. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ye Y, Zhang L, Hu T, Yin J, Xu L, Pang Z

and Chen W: CircRNA_103765 acts as a proinflammatory factor via

sponging miR-30 family in Crohn's disease. Sci Rep.

11(565)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ju J, Song YN, Chen XZ, Wang T, Liu CY and

Wang K: circRNA is a potential target for cardiovascular diseases

treatment. Mol Cell Biochem. 477:417–430. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Jin J, Sun H, Shi C, Yang H, Wu Y, Li W,

Dong YH, Cai L and Meng XM: Circular RNA in renal diseases. J Cell

Mol Med. 24:6523–6533. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Giordano L, Porta GD, Peretti GM and

Maffulli N: Therapeutic potential of microRNA in tendon injuries.

Br Med Bull. 133:79–94. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Huang DH, Wang GY, Zhang JW, Li Y, Zeng XC

and Jiang N: MiR-501-5p regulates CYLD expression and promotes cell

proliferation in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol.

45:738–744. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Liu D, Kang H, Gao M, Jin L, Zhang F, Chen

D, Li M and Xiao L: Exosome-transmitted circ_MMP2 promotes

hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by upregulating MMP2. Mol

Oncol. 14:1365–1380. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ou R, Lv J, Zhang Q, Lin F, Zhu L, Huang

F, Li X, Li T, Zhao L, Ren Y and Xu Y: circAMOTL1 motivates AMOTL1

expression to facilitate cervical cancer growth. Mol Ther Nucleic

Acids. 19:50–60. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Zhou J, Zhang S, Chen Z, He Z, Xu Y and Li

Z: CircRNA-ENO1 promoted glycolysis and tumor progression in lung

adenocarcinoma through upregulating its host gene ENO1. Cell Death

Dis. 10(885)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Ebbesen KK, Hansen TB and Kjems J:

Insights into circular RNA biology. RNA Biol. 14:1035–1045.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Siede D, Rapti K, Gorska AA, Katus HA,

Altmüller J, Boeckel JN, Meder B, Maack C, Völkers M, Müller OJ, et

al: Identification of circular RNAs with host gene-independent

expression in human model systems for cardiac differentiation and

disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 109:48–56. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Li J, Yu T, Yan M, Zhang X, Liao L, Zhu M,

Lin H, Pan H and Yao M: DCUN1D1 facilitates tumor metastasis by

activating FAK signaling and up-regulates PD-L1 in non-small-cell

lung cancer. Exp Cell Res. 374:304–314. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Huang S, Liu Z, Jiang F, He H and Zhong W:

DCUN1D1 promotes tumour progress in prostate cancer and its effect

on DU145 in vitro. J Pak Med Assoc. 71:473–478. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

O-charoenrat P, Sarkaria I, Talbot SG,

Reddy P, Dao S, Ngai I, Shaha A, Kraus D, Shah J, Rusch V, et al:

SCCRO (DCUN1D1) induces extracellular matrix invasion by activating

matrix metalloproteinase 2. Clin Cancer Res. 14:6780–6789.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhao Y, Hu Y, Shen Q, Xiong R, Song X and

Guan C: DCUN1D1, a new molecule involved in depigmentation via

upregulating CXCL10. Exp Dermatol. 32:457–468. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Shao JL, Li H, Zhang XR, Zhang X, Li ZZ,

Jiao GL and Sun GD: Identification of serum exosomal MicroRNA

expression profiling in menopausal females with osteoporosis by

high-throughput sequencing. Curr Med Sci. 40:1161–1169.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Chen SC, Jiang T, Liu QY, Liu ZT, Su YF

and Su HT: Hsa_circ_0001485 promoted osteogenic differentiation by

targeting BMPR2 to activate the TGFβ-BMP pathway. Stem Cell Res

Ther. 13(453)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Fan L, Yang K, Yu R, Hui H and Wu W:

circ-Iqsec1 induces bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell

(BMSC) osteogenic differentiation through the miR-187-3p/Satb2

signaling pathway. Arthritis Res Ther. 24(273)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|