Introduction

The development of cancer is promoted by age,

overweight, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and metabolic

syndrome. T2DM is associated with a significant number of cancers,

such as those of the breast, pancreas, liver, colorectal, renal and

reproductive systems. Diabetic patients with cancer have increased

mortality compared with cancerous non-diabetic individuals

(1).

Hyperglycemia, transient hyperinsulinemia, chronic

inflammation and oxidative stress promote the activation of

signaling mechanisms that favor the initiation, development and

progression of cancer during diabetes (1,2). The

increased plasma levels of insulin-like growth factors, enhanced

production of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNFα and IL1β), low

expression of certain adipokines (adiponectin), and aberrant

protein glycosylation in T2DM organisms induce changes in metabolic

and signaling pathways (2). These

changes help cancer cells adapt to a hyperglycemic environment and

promote the proliferation and acquisition of a migratory and

chemoresistant phenotype (3). The

increased proliferative activity of tumor cells depends on a

continuous supply of biomolecules such as amino acids,

carbohydrates, nucleotides and fatty acids capable of providing the

energy requirements of the cell, favoring the synthesis of DNA,

RNA, proteins and lipids at a higher rate in diabetic patients

(4).

The malignant cells that survive primary treatment

evolve into a population of resistant clones, leading to cancer

progression and patient death (5).

Mortality from breast cancer (BC) is higher in women with diabetes

compared with women without it, since diabetes can exacerbate the

onset and development of cancer by activating various cellular

processes such as proliferation, migration and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (6). Additionally, variations in the

expression and activity of several drug-metabolizing enzymes,

altered drug membrane transport, and evasion of apoptosis play a

critical role in drug resistance (2).

It was found that a high concentration of glucose

promotes an invasive/metastatic phenotype, inducing proliferation,

migration, EMT and cell invasion in MDA-MB-231 cells, which was

associated with increased expression of plasminogen activator

urokinase-type (uPA), its receptor (uPAR), and type 1 inhibitor

(PAI-1), leading to the activation of plasminogen activation system

and AKT signaling (4,6). EMT is one of the mechanisms to enhance

migratory and invasive properties of tumor cells, together with

cell survival, invasiveness and chemotherapy drug resistance

(7).

Elevated blood glucose levels regulate the

chemoresistance in BC (2,3,8).

Hyperglycemia and diabetes promote the sensitivity of BC cells or

breast tumors to some DNA repair inhibitors (8). On the other hand, the development of

resistance to cisplatin and other drugs by BC cells is frequently

mediated by the prevention of apoptosis, increased EMT, DNA repair,

Wnt and PI3K pathways, since cisplatin leads to apoptosis through

increased reactive oxygen species, which leads to DNA damage

(9). However, the genes and

signaling pathways implicated in the development of chemoresistant

and aggressive BC phenotype by high glucose (HG) in diabetic

patients have not been fully explored.

It was aimed to detect the action of HG on the

chemoresistance to cisplatin and changes in gene expression in

MDA-MB-231 BC-derived cells. In addition, to analyze the genes,

metabolic and signaling pathways that can mediate the promotion of

cisplatin resistance and a migratory phenotype by HG.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

MDA-MB-231 BC cells were acquired from the American

Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified

Eagle's Medium/Ham's Nutrient Mixture F12 (DMEM-F12;

MilliporeSigma). The medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; Biowest) and the following antibiotics: penicillin 100

U/ml and streptomycin 100 µg/ml (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The cells were authenticated by the 17 short tandem repeat

profiling (ATCC Cell Line Authentication Service) in August 2020.

The RNA extraction and microarray were processed in 2019, and the

corresponding microarray series GSE136277 was made public in August

2019. Most of the experiments were concluded in 2020. Cultures were

routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using a PCR-based

detection kit (cat. no. ab289834; Abcam). For propagation, cells

were seeded and cultured in monolayers in 75-cm2 tissue

culture flasks. For some experiments, cells cultured in

6.0-cm-diameter culture plates to 60-80% confluence were cultured

for 48 h in the following conditions: i) Normal glucose (NG), 5.6

mmol/l; ii) 30 mmol/l (HG); iii) HG + 60 µmol/l cisplatin

(MilliporeSigma); and iv) NG + 60 µmol/l cisplatin. The cells were

detached with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution (Biowest).

Supplementation with ~5.6 mmol/l D-glucose

approximates normal blood sugar levels, whereas concentrations ~10

mmol/l and above mimic pre-diabetic and diabetic conditions,

respectively. In most studies, HG conditions use 25-30 mmol/l

glucose. In previous studies, it was found that 30 mmol/l glucose

produced the most evident and reproducible effects on MDA-MB-231

cells (4,6). Furthermore, interstitial glucose can

be similar to blood glucose, considering that interstitial glucose

concentrations in skeletal muscle of patients with T2DM during a

glucose tolerance test were similar to blood glucose levels

(10).

MTT assay

The MTT method is a quantitative colorimetric assay

that measures the metabolic activity of cells, which is

proportional to changes in the cell populations. This assay was

used to determine the changes in the cell population and the median

lethal concentration (LC50) of cisplatin under standard

culture (17.5 mmol/l glucose), NG and HG conditions, and using an

osmotic control of glucose 5.6 mmol/l plus mannitol 19.4 mmol/l

(Mannitol). A total of 5,000 cells per well were seeded in 96-well

plates and exposed to different concentrations of cisplatin (15-90

µmol/l). The culture medium was replaced with 200 µl serum-free

DMEM and 50 µl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml) after 48 h of incubation

at 37˚C. Then, the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h, the

medium was removed, and 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to

dissolve the formazan crystals. The plate was read at 570 nm

wavelength using a microplate reader iMark (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.).

Western blotting

The cells were washed with PBS and lysed in RIPA

Buffer (cat. no. 89900; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), containing

a protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. I3786; MilliporeSigma) to

prevent protein degradation. Proteins were quantified by the

Bradford assay, and the cell lysates were stored at -70˚C. Equal

amounts of protein (100 µg per well) were mixed with Laemmli sample

buffer and separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

The transfer was realized in a PVDF membrane (0.8

mm/cm2, 2 h), using Tris buffer 25 mmol/l, glycine 192

mmol/l and methanol 20%. Membranes were then blocked with 5% BSA in

TBS for 1 h at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding.

Subsequently, membranes were incubated overnight at 4˚C with

primary anti-caspase-3 antibody (1:500; cat. no. sc-7272; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) in TBS-T (0.1% Tween-20) containing 1%

BSA. Antibody binding was detected using an HRP-conjugated

secondary antibody (1:5,000; cat. no. 7076S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), incubated for 1 h at room temperature, followed

by visualization with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Clarity

Western ECL substrate, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), according to

the manufacturer's instructions. The images were obtained using the

C-Digit Blot Scanner (LI-COR Biosciences). The bands were

quantified by densitometry analysis using the Image Studio 4.0

software (LI-COR Biosciences).

RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. RNA quality was verified by 2% agarose gel

electrophoresis, followed by ethidium bromide staining and

visualization under UV light and quantified using a NanoDrop

ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Hybridization and microarray

analysis

A total of 10 µg of total RNA obtained from cells

cultured in NG and HG media was used for cDNA synthesis and

labeling with the Superscript II kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), incorporating dUTP-Cy5 for HG samples and

dUTP-Cy3 for NG (control) samples. The absorbance was measured at

655 nm for Cy5 and 555 nm for Cy3. Fluorophore-labeled cDNAs were

hybridized in similar quantities to the Human 10K 50-mer

oligonucleotide collection (MWG Biotech Oligo Bio Sets).

Microarray images were acquired and quantified using

a ScanArray 4000 scanner with QuantArray software (Packard

BioChips; PerkinElmer, Inc.), and data were analyzed using

Array-Pro Analyzer software (Media Cybernetics, Inc.). Background

correction, normalization, intensity filtering, replicate analysis,

and the selection of differentially expressed genes were performed

using genArise, a free program developed by the Computing Unit of

the Cellular Physiology Institute, National Autonomous University

of Mexico (http://www.ifc.unam.mx/genarise/). The data generated

in the present study were deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus

(GEO) platform under accession number GSE136277 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE136277).

Differentially expressed genes were identified using the following

statistical cutoffs: Z-score ≥2 or ≤-2 for biological significance,

and a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤0.05 to account for multiple

testing. These thresholds were applied from the outset of the

analysis to ensure the robustness of the candidate genes included

in subsequent evaluations.

Reverese transcription-quantitative

PCR (RT-qPCR)

The microarray analysis was validated by RT-qPCR for

frizzled 3 (FZD3) and tetraspanin 1 (TSPAN1). Total

RNA (1 µg) was reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript™ III

First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol (50˚C

for 60 min, followed by enzyme inactivation at 70˚C for 15 min).

Alternatively, when individual components were used, reverse

transcription was performed in a 20 µl reaction mixture containing

200 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase, 1X first-strand buffer, 0.5 mM

dNTP mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 25 µg/ml oligo(dT)

primers (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and 40 U

RNase inhibitor, incubated at 37˚C for 60 min with enzyme

inactivation at 95˚C for 15 min. The resulting cDNA was amplified

using the Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The resulting cDNA was amplified using the Maxima

SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the

following thermocycling conditions: Initial activation at 95˚C for

15 min; 40 cycles of 95˚C for 15 sec and annealing at the

primer-specific melting temperature for 1 min; followed by a final

extension at 72˚C for 10 min. Expression of the selected genes was

normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase

(HPRT). The primer sequences used were as follows:

FZD3 forward, 5'-CATGGAGATGTTTGGTGTTCCTT-3' and reverse,

5'-AAGTCGAGGATATGGCTCATCAC-3'; TSPAN1 forward,

5'-TGGGCTGCTATGGTGCTA-3' and reverse, 5'-TGCAGGTTTCATTGGCTGT-3';

and HPRT forward, 5'-CATTATGCTGAGGATTTGGAAAGG-3' and

reverse, 5'-CTTGAGCACACAGAGGGCTACA-3'. Relative expression levels

were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method (11).

HPRT was used as a housekeeping gene because

its expression has been considered moderately stable in BC cell

lines, including MDA-MB-231 cells (12). Under hyperglycemic conditions, Liu

et al (13) identified the

HPRT gene as one of the more reliable reference genes in

retinal pigment epithelial cells, and even HPRT expression

was more stable than ACTB and GAPDH genes.

Additionally, no changes in the expression of this gene under HG

were found in our microarray study.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) expression

of TSPAN-1 and FZD3 in BC tissue

IHC expression of TSPAN1 and FZD3 in BC

tissue. To investigate the protein expression patterns of TSPAN1

and FZD3, representative IHC images of ductal breast carcinoma were

analyzed from 50 samples available in the Human Protein Atlas

database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/), corresponding to women

aged 30-37 years. Adjacent normal breast tissue and adenoma samples

were used as controls.

Gene analysis and Gene Ontology

(GO)

The analysis of genes differentially regulated by HG

and their associated functions, including GO categories (cellular

components, molecular functions and biological processes), as well

as biological pathways, was performed using Gene Set Enrichment

Analysis (GSEA). For this purpose, the WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis

Toolkit (WebGestalt; http://www.webgestalt.org/) and WikiPathways Cancer

were employed. Gene sets were considered significant at an FDR

≤0.05. In addition, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway analysis (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) was used to

determine the interactions of differentially expressed genes within

metabolic and signaling pathways.

Functional association network and

selection of genes involved in chemoresistance

All the overexpressed and downregulated genes

associated with cancer were uploaded into the program STRING

(https://string-db.org/), which predicts the

protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. The confidence score for

displaying interaction was 0.9. The formatted PPI networks were

uploaded and visualized with the Cytoscape software (version

3.10.1) (14). Due to the

complexity of this network, the CytoHubba plugin was used to select

the 50 nodes with the highest degree score, and their interaction

network was constructed (15).

Furthermore, the overexpressed genes with at least 2-fold change

and their involvement in chemoresistance, according to scientific

studies (16-19),

were selected, and their possible participation in HG-dependent

chemoresistance was considered.

Kaplan-Meier (KM) plot analysis

Overall survival (OS) analysis was performed for the

key genes YBX3 (also known as CSDA), amphiregulin

(AREG), amyloid precursor protein (APP) and

N-cadherin (CDH2) using the KM Plotter database (20); (https://kmplot.com) to assess the prognostic value of

the genes associated with cisplatin resistance in BC. A cohort of

153 patients with TNBC who were split into high and low expression

groups was selected, considering the median expression of the gene.

OS plots were created using data from BC samples negative for

estrogen, progesterone and HER2 receptors, as detected by IHC and

microarray. The hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals

(CIs) and log-rank P-values were calculated.

Coexpression analysis

To evaluate whether the selected genes are

coexpressed in a cohort of patients with BC and the potential

molecular and regulatory interactions between proteins codified by

them, the coexpression of AREG, FZD3, APP and

CDH2 with YBX3 was performed using R2: Genomics

Analysis and Visualization Platform (http://r2.amc.nl)

on TCGA Breast Invasive Carcinoma (BRCA) datasets (1,097 samples)

with R2 internal identifier ps_avgpres_tcgabrca1097_tcgars. Pearson

correlation coefficients and associated P-values were calculated,

with scatter plots and linear regression used for

visualization.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in at least three

independent replicates. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test was used

for MTT, western blotting and RT-qPCR analyses, and performed using

GraphPad Prism 8.02 software (Dotmatics). P≤0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. Microarray and

GSEA analyses were considered significant with fold-change ≥1.5 and

FDR≤0.05, respectively. Co-expression analyses of AREG,

FZD3, APP and CDH2 with YBX3 were

performed using the R2 Genomics platform https://hgserver1.amc.nl/cgi-bin/r2/main.cgi, and

survival analyses were conducted using the KM Plotter, with HRs,

95% CIs and log-rank P-values. P≤0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Previously, it was found that HG increases cell

population growth, migration, invasion and EMT in MDA-MB-231 cells

(4). In the present study, the

effect of HG was analyzed on cisplatin resistance, cell death and

changes in gene expression. Additionally, it was analyzed how the

change in gene expression is associated with a chemoresistant and

aggressive phenotype.

Hyperglycemia-induced resistance to

cisplatin

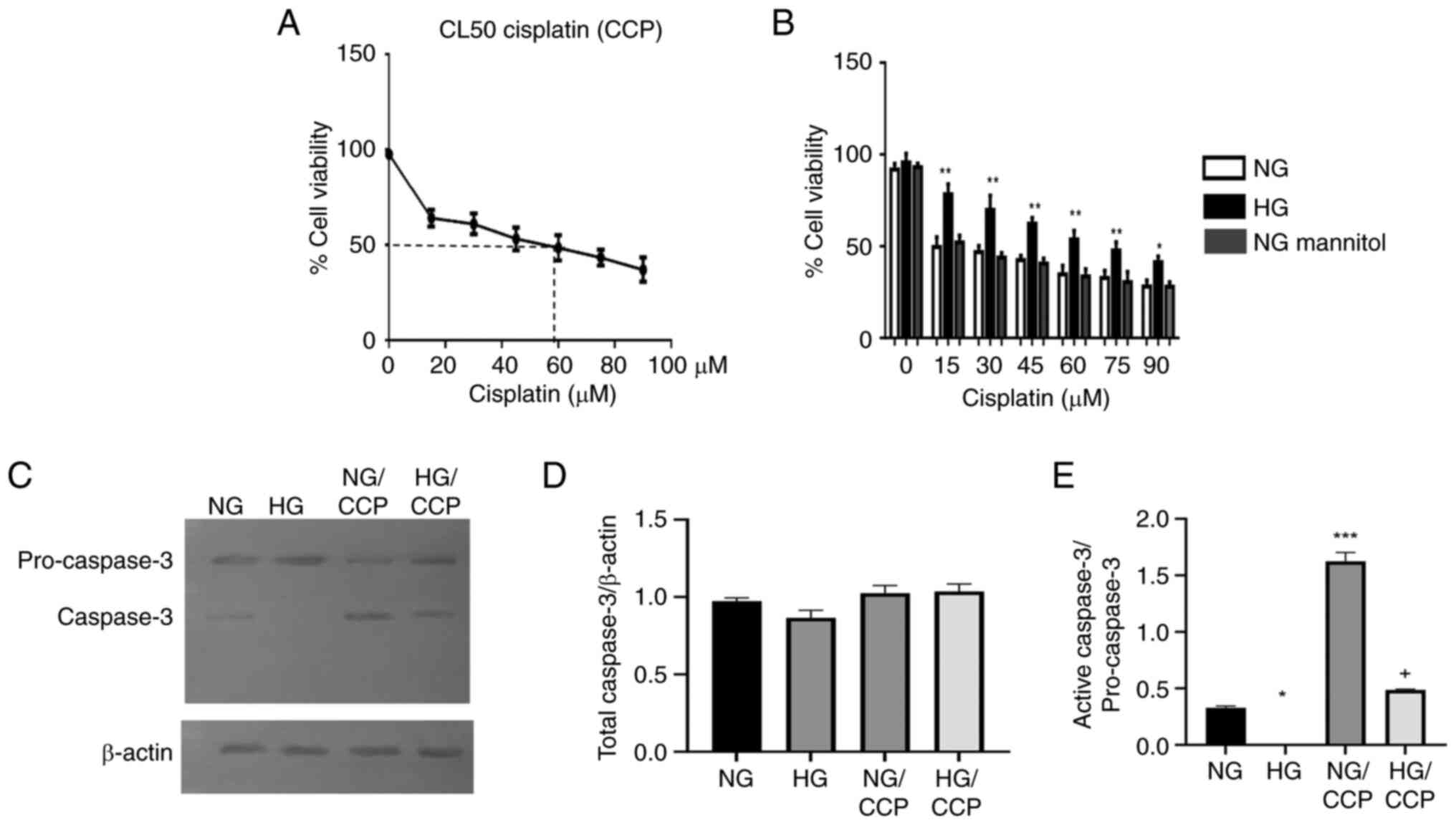

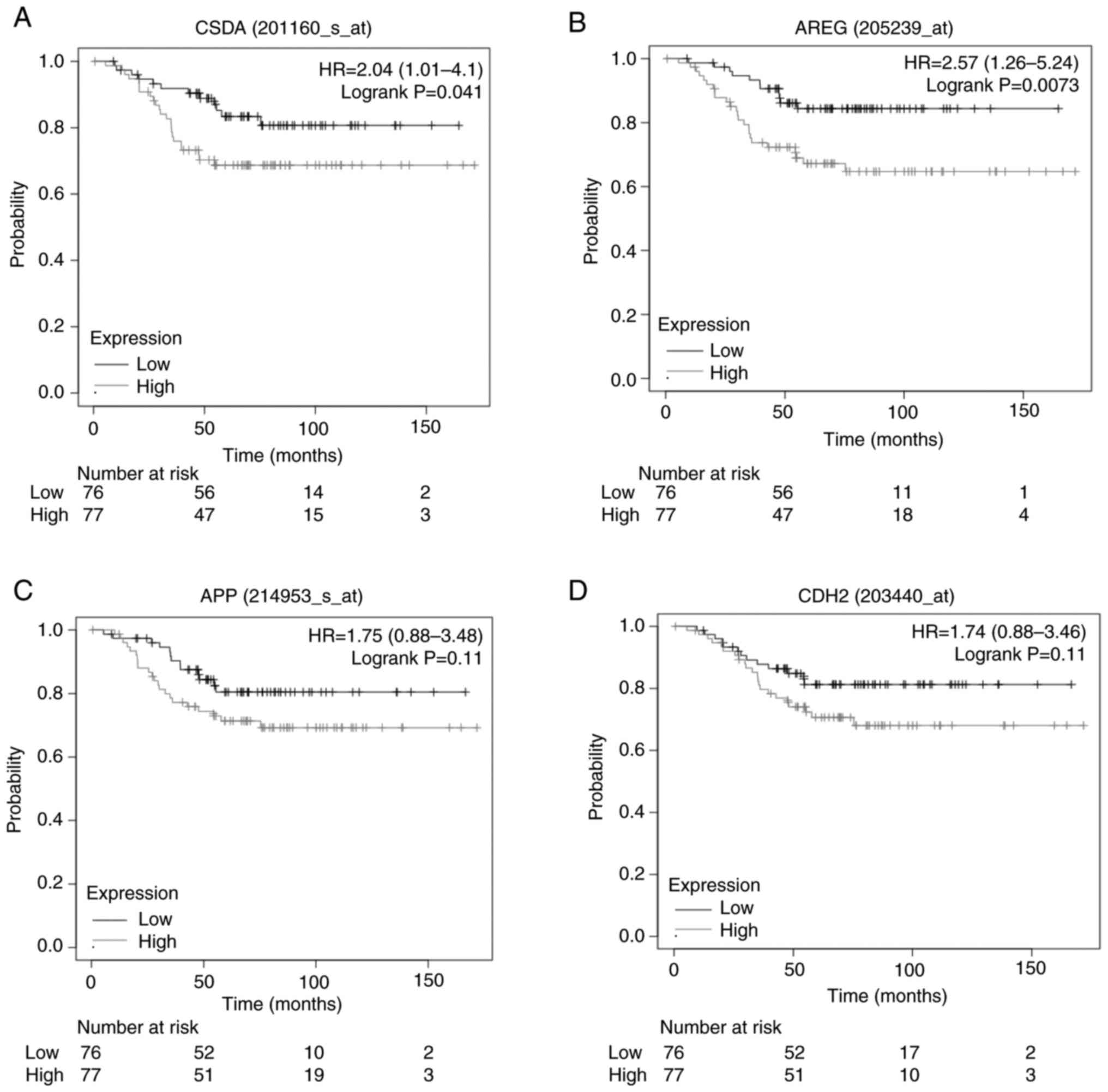

To investigate whether HG induces drug resistance,

the LC50 of cisplatin for MDA-MB-231 cells was

determined under standard culture conditions (glucose 17.5 mmol/l),

NG, NG with mannitol (osmotic control) and HG. The osmotic control

group showed no difference compared with the NG group. Cell

viability progressively decreased as cisplatin concentration

increased from 15 to 90 µmol/l in a concentration-dependent manner,

with LC50 values of 60, 15 and 75 µmol/l for standard,

NG and HG conditions, respectively. These findings indicated that

cells cultured under HG and standard conditions were more resistant

to cisplatin compared with those cultured under NG. Thus, in the

present study, cisplatin resistance was directly proportional to

glucose concentration (Fig. 1A and

B).

| Figure 1HG attenuates the effect of cisplatin

on the cell population and prevents apoptosis. (A and B) MDA-MB-231

cells were treated for 48 h with CCP. The growth of the cell

population was evaluated by the MTT assay in standard, (NG), HG,

and mannitol osmotic control (NG Mannitol) culture conditions.

*P≤0.01 and **P≤0.001 vs. the respective NG

for each cisplatin concentration. No significant differences were

observed between the NG and mannitol-treated groups. (C-E)

Additionally, the activation of caspase 3 was evaluated by western

blotting and densitometry in lysates of cells cultured for 48 h, in

NG and HG conditions, and treated with cisplatin (NG/CCP and

HG/CCP). The intensities of the bands were calculated after

background subtraction, and the sum of the bands (total caspase 3)

and active caspase 3 were normalized to (D) β-actin and (E)

procaspase 3, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of

three independent experiments. *P≤0.05 and

***P≤0.001 vs. NG, and + P≤0.001 vs. HG.

HG, high glucose; NG, normal glucose; CCP, cisplatin. |

Hyperglycemia prevents the apoptosis

induced by cisplatin

Apoptosis induced by cisplatin under normoglycemic

and hyperglycemic conditions was evaluated in MDA-MB-231 cells by

western blot analysis of caspase-3 activation. The caspase 3

antibody recognizes two band, one of higher molecular weight (MW)

corresponding with the procapase 3, and other of lower MW

corresponding to the cleaved/active caspase 3 (Fig. 1C). Both NG and HG groups exhibited

similar levels of total caspase 3 independently of the cisplatin

treatment (Fig. 1D). Whereas,

cisplatin induced a significant increase in the proportion of

active caspase 3 in both NG (P≤0.001) and HG (P≤0.001) conditions

(Fig. 1E). Notably, the NG and

NG/cisplatin groups displayed higher levels of active caspase-3

than the corresponding HG and HG/cisplatin groups (Fig. 1E). These results indicated that HG

attenuated cisplatin-induced apoptosis, thereby promoting cisplatin

chemoresistance.

Overall changes in gene

expression

Considering an expression change equal to or greater

than 1.5-fold, 1,099 genes were differentially expressed. Among

these, 457 were overexpressed, while 642 were downregulated under

the HG condition. The top 15 overexpressed and downregulated genes

in the HG microenvironment are presented in Table I. All differentially expressed genes

are listed in Tables SI and

SII.

| Table ITop 15 upregulated and downregulated

genes in a hyperglycemic environment. |

Table I

Top 15 upregulated and downregulated

genes in a hyperglycemic environment.

| Upregulated |

|---|

| ID | Genes | Z score | Full name |

|---|

| NM_032741 | AGPAT1 | 4.152511 |

1-Acylglycerol-3-phosphate

O-acyltransferase 1 |

| NM_003043 | SLC6A6 | 4.058222 | Taurine

transporter |

| NM_005727 | TSPAN-1 | 3.811546 | Tetraspanin 1 |

| NM_004189 | SOX14 | 3.648091 | SRY-box 14 |

| NM_021625 | TRPV4 | 3.609894 | Transient receptor

potential cation channel subfamily V member 4 |

| NM_016176 | SDF4 | 3.445534 | Stromal cell

derived factor 4 |

| NM_006213 | PHKG1 | 3.320789 | Phosphorylase

kinase catalytic subunit gamma 1 |

| NM_020649 | CBX8 | 3.251316 | Chromobox 8 |

| NM_001252 | TNFSF7 | 3.129304 | CD70 molecule |

| NM_005919 | MEF2B | 3.041269 | BORCS8-MEF2B

readthrough |

| NM_002600 | PDE4B | 3.035975 | Phosphodiesterase

4B |

| NM_002150 | HPD | 2.983852 |

4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase |

| NM_014610 | GANAB | 2.950495 | Glucosidase II

alpha subunit |

| NM_017412 | FZD3 | 2.854118 | Frizzled class

receptor 3 |

| Downregulated |

| NM_006544 | SEC10L1 | -4.523611 | Exocyst complex

component 5 |

| NM_012261 | LAMP5 | -4.45501 | Lysosomal

associated membrane protein family member 5 |

| NM_012070 | ATRN | -4.333672 | Attractin |

| NM_004185 | WNT2B | -3.908675 | Wnt family member

2B |

| NM_001697 | ATP5O | -3.87772 | ATP synthase, H+

transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, O subunit |

| NM_053004 |

FLJ21125 | -3.814458 | G protein subunit

beta 1 like |

| NM_003692 | TMEFF1 | -3.744839 | Transmembrane

protein with EGF like and two follistatin like domains 1 |

| NM_006866 | LILRB1 | -3.717488 | Leukocyte

immunoglobulin like receptor A2 |

| NM_003072 | SMARCA4 | -3.709549 | SWI/SNF related,

matrix associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin,

subfamily A, member 4 |

| NM_021176 | G6PC2 | -3.584369 |

Glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit

2 |

| NM_004937 | CTNS | -3.50955 | Cystinosin,

lysosomal cystine transporter |

| NM_004208 | PDCD8 | -3.506222 | Apoptosis-inducing

factor, mitochondrion-associated, 1 |

| NM_013335 | GMPPA | -3.505725 | GDP-mannose

pyrophosphorylase A |

| NM_017882 | CLN6 | -3.495366 |

Ceroid-lipofuscinosis, neuronal 6, late

infantile, variant |

| NM_022444 | SLC13A1 | -3.435806 | Solute carrier

family 13 (sodium/sulfate symporters), member 1 |

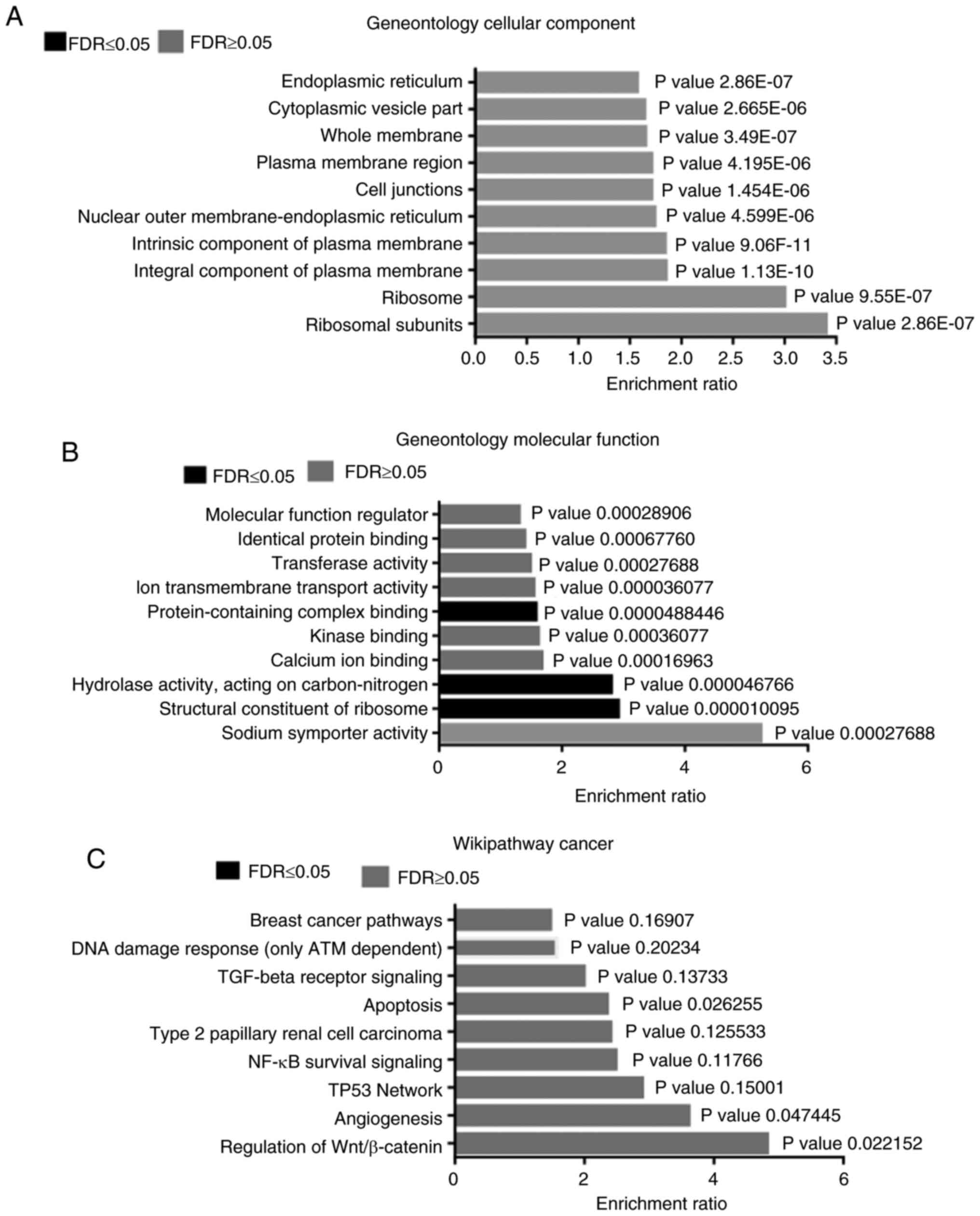

GSEA

Microarray data were subjected to functional

enrichment analysis using WEB-Gestalt and the WikiPathways

database. In the cellular component analysis, an activation of

genes that encode protein constituents of the ribosomes, plasma

membrane, cell junctions and endoplasmic reticulum was found

(Fig. 2A). This was also reflected

in the molecular function analysis, where changes in structural

constituents of ribosomes, sodium symporter activity and ion

transmembrane transport were identified. In addition, changes in

hydrolase activity, calcium ion binding, kinase binding and

protein-containing complex binding were observed (Fig. 2B). According to the enrichment

analysis, the following signaling pathways were enriched in a

hyperglycemic microenvironment: Wnt/β-catenin, angiogenesis, TP53

network, NF-κB survival signaling, apoptosis, TGF-beta receptor

signaling and ATM-dependent DNA damage response (Fig. 2C).

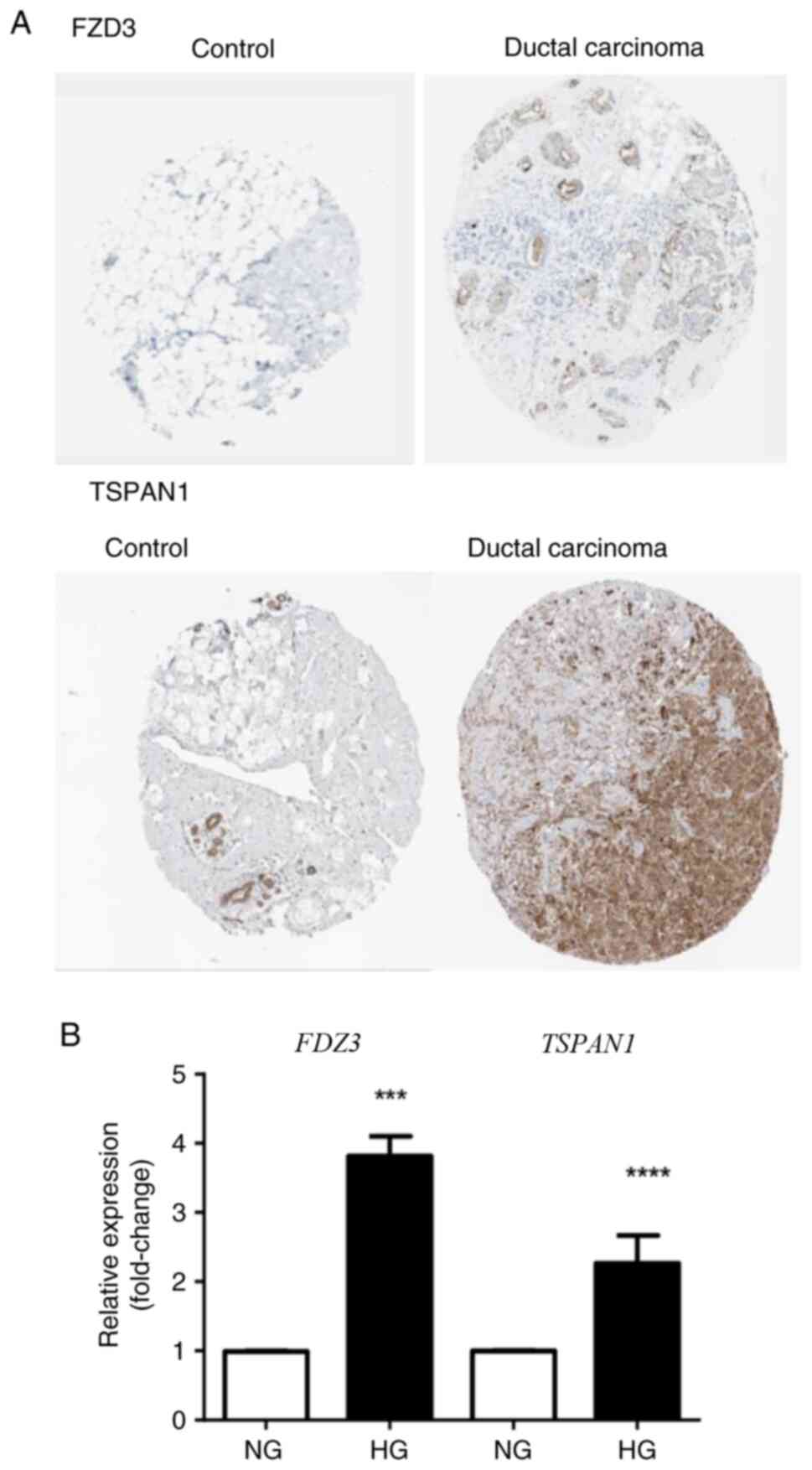

Gene validation

The expression of TSPAN1 and FZD3 was

evaluated by RT-qPCR to validate the microarray analysis. Both

genes are associated with an aggressive BC phenotype and showed

some of the highest Z-scores (3.81 for TSPAN1 and 2.85 for

FZD3). In particular, FZD3, a protein of the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway, exhibited the highest Z-score. RT-qPCR analysis confirmed

that FZD3 expression under HG conditions was 3.81-fold

higher compared with NG (Fig. 3).

Similarly, TSPAN1 expression under HG conditions was

2.26-fold higher than under NG conditions, consistent with the

microarray results (Fig. 3). These

findings are also supported by data from the Human Protein Atlas,

which shows higher expression of TSPAN1 and FZD3 proteins in BC

tissues compared with healthy mammary tissue (Fig. 3).

Hyperglycemia alters genes associated

with metabolism

According to the aforementioned analysis with the

KEGG pathways program, it was found that a high number of genes of

transmembrane transporters and ribosomal proteins were

differentially expressed in HG conditions (Table II). Additionally, several genes

associated with other metabolic processes were found, including: i)

Synthesis of DNA, RNA and proteins; and ii) purine, pyrimidine and

lipid metabolism. Noteworthy, the upregulation of some genes of

electron chain transport or ECT (COX41, COX61,

COX7B and NDUFB3) indicated an increase in the

electron flux through this chain. However, subunits ATP5O

and ATP5D of the ATP synthase were downregulated, suggesting

the uncoupling between the ECT and ATP synthesis.

| Table IIKyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes pathways associated with genes regulated by

hyperglycemia. |

Table II

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes pathways associated with genes regulated by

hyperglycemia.

| Metabolic or

signaling pathway | Total genes | Genes

upregulated | Genes

downregulated |

|---|

| Transmembrane

transport | 27 | SLC6A6,

SLC44A4, SLC35F2, SLC16A8, SLC13A2,

SLC6A20, SLC23A2, SLC25A19, SLC39A7,

SLC22A18AS, SLC25A5 | SLC13A1,

SLC22A7, SLC26A3, SLC7A7, SLC2A8,

SLC35B3, SLC6A12, SLC1A7, SLC39A6,

SLC39A4, SLC35C2, SLC38A3, SLC16A10,

SLC44A2, SLC25A17, SLC28A2 |

| Cytokine-cytokine

receptor interaction | 24 | CXCL1,

CXCR3, PDGFRA, IL9R, IL21R,

IL1RA, EPOR, IL17RA, IL17RB,

TNFSF7, CCL20, IL32 | TNIP2,

CCR9, CXCR2, CXCR4, CXCR6,

CCRL1, TGFBR2, TGFBR1, CXCL6,

IFNA8, IL4, IL17C |

| Regulation of

cytoskeleton | 24 | CHRM4,

FGFR1, PDGFRA, VAV3, CFL, ITGB4,

RASAL-1, RIN1, CDC42BPA, RAB9A,

RHOB | PIK3C2B,

PIK3R5, CHRM1, FGF20, FGFR2,

ACTN3, VCL, VAV2, ILK, ARHGDIB,

RDX, RRAS, RASSF7 |

| Ribosomal proteins

(extra and intramitochondrial) | 20 | RPS13,

RPS17, RPS21, RPS3A, RPS8, RPS7,

RPL23A, RPL13A, RPL15, RPL9,

MRPS18B, MRPS7, MRPL15, MRLP17,

MRPL49 | MRPS31,

MRPL11, RPL23, MRPL33, MRPL42 |

| Purine, pyrimidine

metabolism/nucleic acid synthesis | 22 | XDH,

POLA2, POLG, GUCY2F, PDE1B,

PAPSS2, PDE2A, UPB1, PDE4B,

ADCY7, NME1, ECGF, NOC3L,

ATIC | CDA,

NT5E, AK3, AMPD2, AMPD3, ADA2,

MTAP, DNPH1 |

| MAPK | 20 | FGFR1,

PDGFRA, MKNK, DUSP4, RIN1,

MAPK8IP1, RASGRF1 | PPP3C,

FGF20, TGFBR2, MAP2K3, MAPKAPK5,

MEF2C, BLK, DUSP5, TGFBR1,

FGFR2, RRAS, RAPGEF2, RASSF7 |

| Ras | 19 | FGFR1,

PDGFRA, TEK, RIN1, RASGRF1,

SPEC1, RASAL-1, RIN1 | PIK3C2B,

PIK3R5, FGF20, GNB1, FGFR2,

ANGPT1, RRAS, RALA, RAPGEF2,

RASSF7, PLAAT1 |

| Apoptosis | 19 | TRAF1,

CASP10, XIAP, BCL2L2, BIRC2,

RHOB, PERP | PTPN13,

PIK3C2B, PIK3R5, PDCD8, PDCD5,

BIRC3, BIK, DAPK1, CCAR2, BNIP1,

TNIP2, RASSF7 |

| Wnt β-catenin | 17 | FZD3,

FZD4, LPR8, DVL2, WNT1, LEF1,

DKKL1, RHOB, PPP2R3B | WNT2B,

TGFBR2, BMP2, TGFBR1, ID1,

PPP3CA, TBL1, CAMK2B |

| Focal adhesion | 17 | PDGFRA,

XIAP, VAV3, LAMC2, ITGB4,

PPP2R5B, PPP2R5C, RASGRF1 | PIK3C2B,

PIK3R5, THBS2S, ACTN3, VCL, BLK,

VAV2, BIRC2, ILK |

| Glycerophospholipid

metabolism | 16 | AGPAT1,

MBOAT7, CEPT1, GLA, PNLIPRP2,

ACHE, LYPLA1, PLA2G2A | AGPAT4,

CDIPT, CHPT1, PCYT1B, PLA2G2D,

TAZ, PAFAH1B3, PLAAT1 |

| Jak-STAT | 14 | PIM1,

PIAS1, IL9R, IL21R, EPOR,

PTPN6 | PIK3C2B,

PIK3R5, BLK, SOCS5, IFNA8, IL4,

IL17C, GFAP |

| Oxidative

phosphorylation | 10 | COX4I1,

COX6A1, COX7B, NDUFB3 | ATP5O,

ATP5D, COX7A1, NDUFA13, NDUFB4,

E2IG2 |

Hyperglycemia alters genes associated

with apoptosis and cell survival

On the other hand, it was found that HG induces

increased expression of some genes that promote cell survival

(TNFSF7 and TRAF1) (21) or prevent apoptosis (XIAP and

BCL2L2) (22,23). Additionally, HG leads to low

expression of proapoptotic factors (BIK, PDCD8, PDCD5, BNIP1,

DAPK1 and CCAR2) (24-26).

These data indicated that HG prevents BC cell death and promotes

cell survival under stress conditions, such as the presence of

chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin (Fig. 1).

Signal pathways associated with the

adaptation to hyperglycemia

The KEGG pathways program indicates that

Wnt-β-catenin, Jak/STAT and Ras-MAPK are involved in the action of

HG, together with processes such as cytokine-cytokine receptor

interaction, regulation of actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion

(Table II). These results and the

PPI analysis suggested that the Wnt-β-catenin signaling has a

significant role in the action of HG.

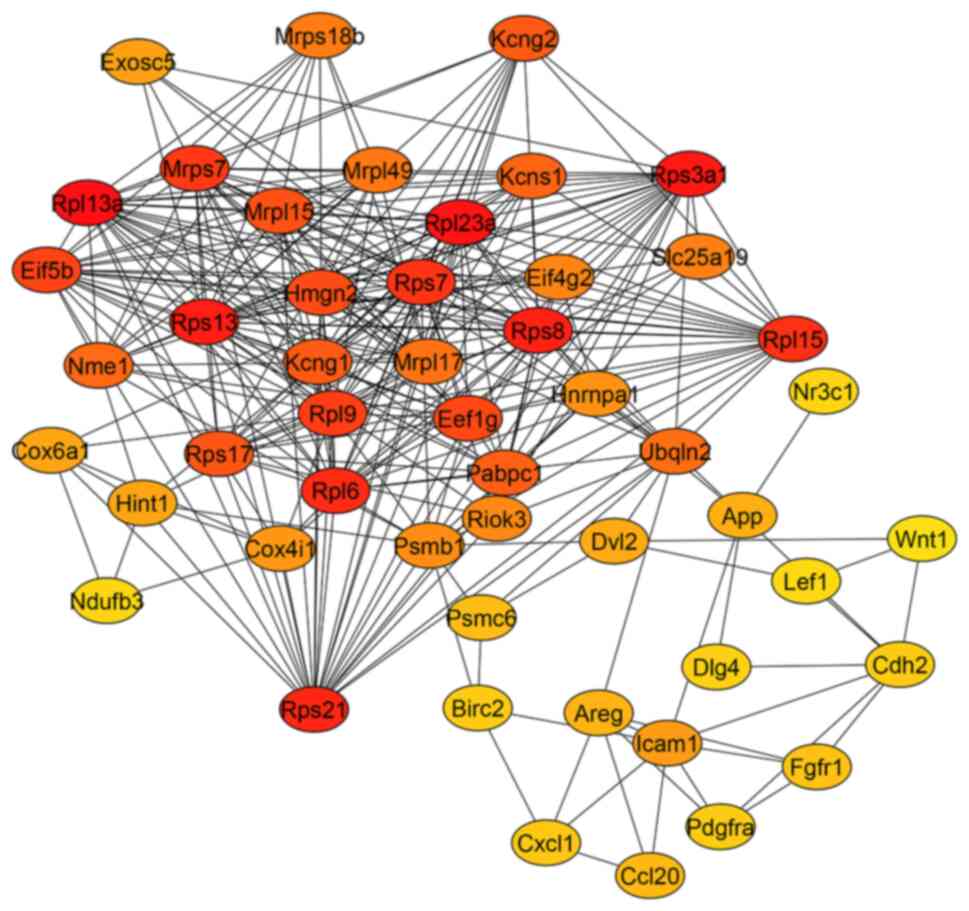

Selection of hub genes and PPI

In the PPI network of overexpressed genes

constructed by Cytoscape, a total of 303 nodes and 834 edges were

arranged (data not shown); further analysis by cytoHubba based on

this network revealed a network with 50 principal nodes (Fig. 4). Between the highest degree score

hubs, genes for ribosomal proteins were found, such as

RPL13a, RPL23a, RPS3a1, RPS13,

RPS8, RPS21, RPL6, RPL15, RPS7,

MRPS7 and RPL9 with a high degree of interaction

shown in red (Fig. 3). Interacting

with these nodes genes coding for transcription and protein

synthesis (PABPC1, EIF4G2, EIF5B, EEF1G

and HNRNPA1), potassium channels (KCNG2, KCNG1

and KCNS1) and metabolism (COX4I1, COX6A1 and

NDUFB3) were found. Other important hubs were associated

with the Wnt/canonical pathway, such as WNT-1, DVL2

and LEF1. Other proteins related to cancer progression were

also represented (APP, AREG and CDH2). It is

noteworthy that ribosomal proteins were overrepresented and had the

highest degree scores (red and orange in Fig. 4). Because of this, nodes of

important proteins had lower degree scores (orange and yellow in

Fig. 4). The PPI network according

to the enrichment analysis indicates the relevance of Wnt/β-catenin

(Fig. 2C).

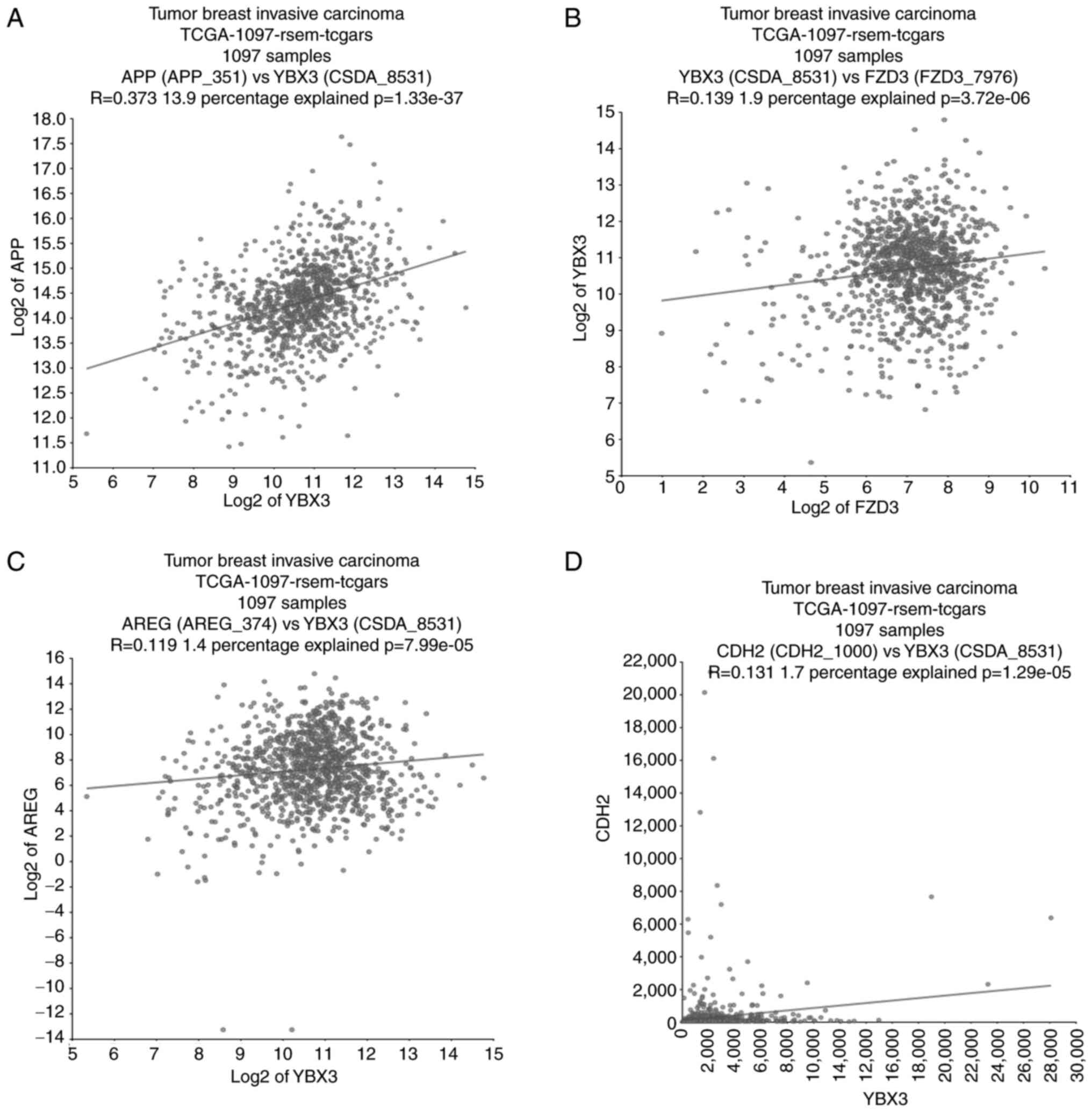

Prognostic value of Hub genes YBX3,

AREG, APP and CDH2

Considering the hub genes with the highest number of

interactions obtained from the CytoHubba analysis and their

prognostic evaluation using the KM-plot platform, YBX3 or

CSDA (HR=2.04; 95% CI, 1.01-4.01; P=0.041), AREG

(HR=2.57; 95% CI, 1.26-5.24; P=0.0073), APP (HR=1.73; 95%

CI, 0.87-3.44; P=0.11) and CDH2 (HR=1.74; 95% CI, 0.88-3.46;

P=0.11) were associated with poor prognosis in diabetic patients

with BC (Fig. 5). These data

demonstrate that high expression of YBX3 and AREG is

significantly associated with reduced survival probability, whereas

APP and CDH2 did not reach statistical significance.

Nevertheless, elevated YBX3 and AREG levels may serve

as potential biomarkers for identifying diabetic patients with BC

with a worse prognosis.

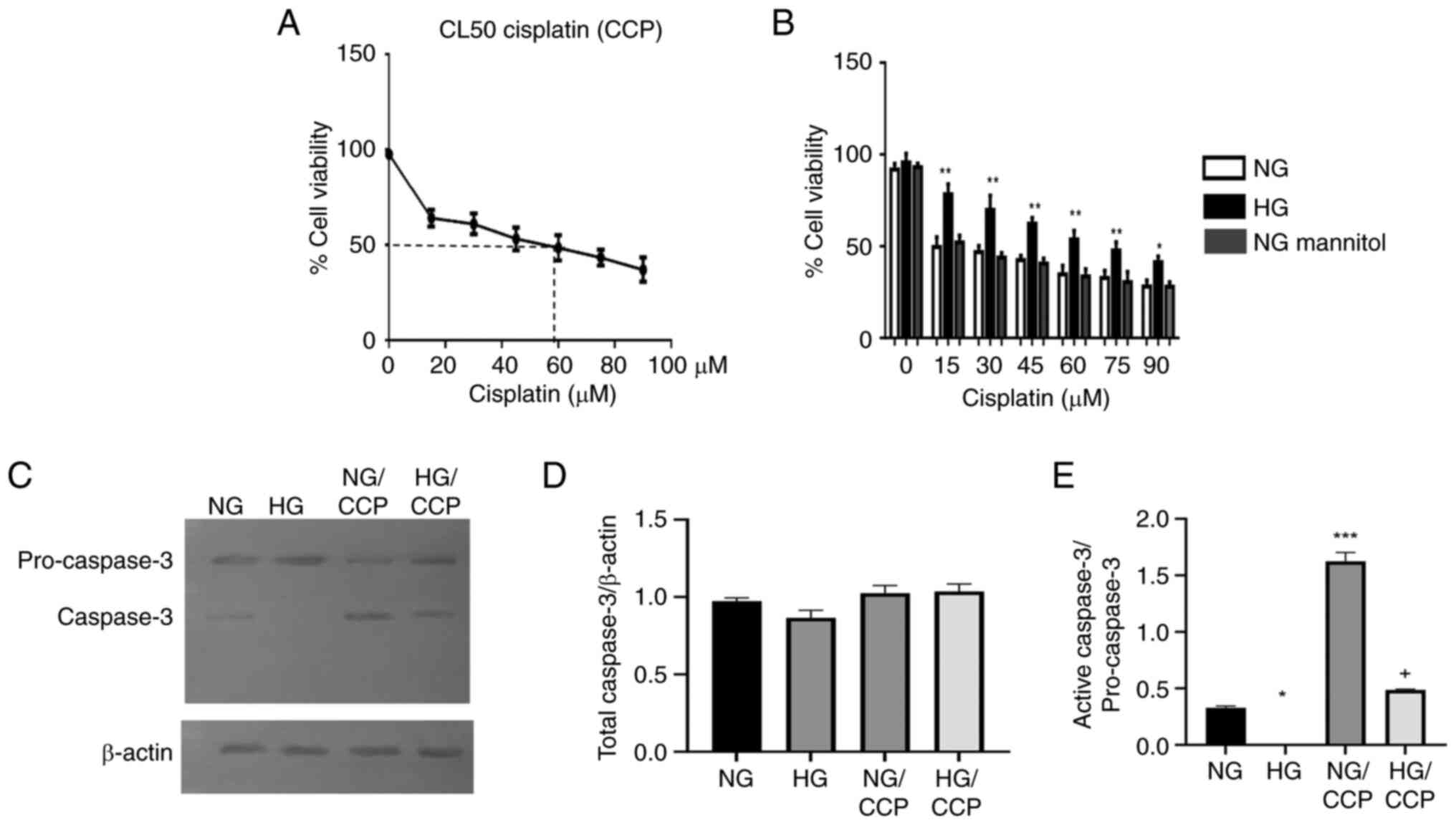

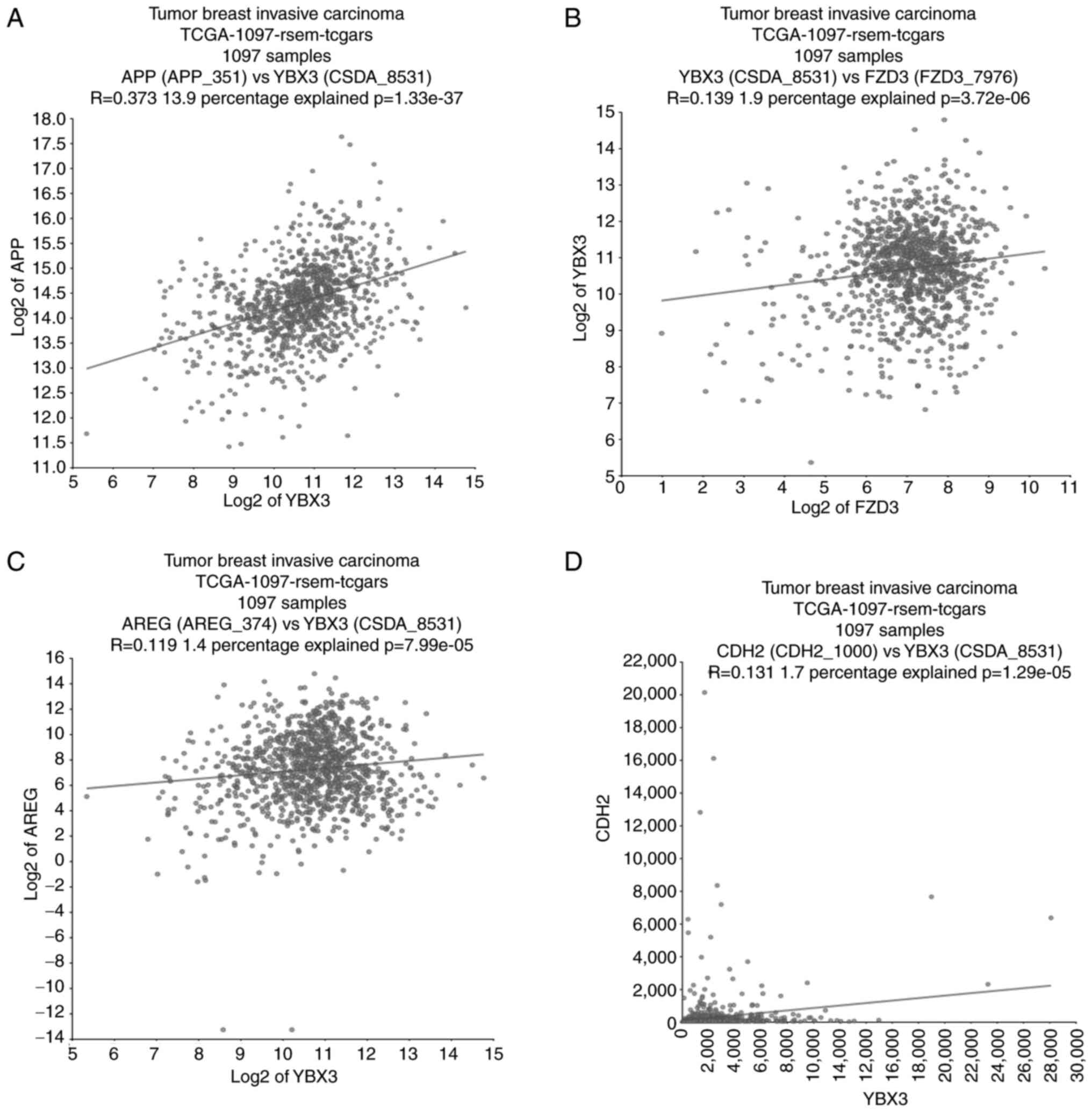

Coexpression of hub genes YBX3, AREG,

APP and CDH2

The coexpression analysis was performed in a cohort

of 1,097 patients diagnosed with breast invasive carcinoma, aged 26

to 90 years, with heterogeneous clinical characteristics (Fig. 6), including estrogen receptor status

(ER+ 71.7%, ER- 22%), progesterone receptor

status (PR+ 63.7%, PR- 31.4%), HER2 status

(HER2+ 14%, HER2- 51.3%) and metastatic

condition (M0 82.6%, MX 14.8% and M1 2%). The analysis revealed

that APP and AREG expression were significantly

correlated with YBX3 (R=0.373 and R=0.119, respectively),

indicating that higher YBX3 expression is associated with

increased APP and AREG expression. A positive but

weak correlation was observed between YBX3 and FZD3

(R=0.139). Importantly, CDH2 and YBX3 also exhibited

a weak but statistically significant correlation (R=0.131;

P=1.29x10-5).

| Figure 6Correlation analysis of gene hubs.

(A-D) Correlation analysis of gene expression was performed using

the R2 Genomics platform (http://r2.amc.nl) in a cohort of 1,097 patients

diagnosed with breast invasive carcinoma (TCGA), aged 26 to 90

years, with heterogeneous hormone receptor status (ER+

71.7%, ER- 22%, PR+ 63.7%, PR-

31.4%, HER2+ 14%, and HER2- 51.3%), and

metastatic condition (M0 82.6%, MX 14.8% and M1 2%). Scatter plots

show the relationships between (A) APP and YBX3, (B)

YBX3 and FZD3, (C) AREG and YBX3, and

(D) CDH2 and YBX3. Each plot includes a regression

line, the Pearson correlation coefficient (R), and the statistical

significance (P-value). TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas. |

Discussion

Hyperglycemia is one of the most important factors

considered a promoter of cancer in T2DM. In the present study, it

was detected that HG induces cisplatin resistance and changes in

gene expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. These changes indicate a

variety of alterations in metabolic and signaling pathways that may

be related to preventing cell death and increased chemoresistance

associated with an aggressive phenotype. Additionally, some genes

(AREG and YBX3) were selected as possible biomarkers

of chemoresistance and prognostic indicators. Furthermore, it was

confirmed that hyperglycemia increases the migratory phenotype in

these cells.

HG induces resistance to cisplatin. The

prometastatic action of HG on MDA-MB-231 cells has been

demonstrated. In our previous studies, HG promoted the growth of

the cell population, EMT, clonogenicity, cell migration and cell

invasion compared with NG and the control of osmolality (4,6). It

was also described that T2DM promoted the progression of BC in mice

(27). In the present study, the

lower IC50 for cisplatin in cell cultures with HG

indicated the induction of cisplatin resistance by HG,

corroborating that HG is a promoter of chemoresistance (2,3,8).

Chemoresistance is associated with an invasive phenotype, and both

are dependent on the prevention of apoptosis and the induction of

EMT, cancer stemness, oncogenes, tumor suppressors, and metabolic

and cell signaling reprogramming, involving transporter pumps,

mitochondrial alterations, DNA repair and autophagy (28).

Prevention of cisplatin-induced apoptosis by

HG. To confirm if the prevention of the cytotoxic effect of

cisplatin by HG is due to the prevention of cell death, caspase-3

was assessed. Caspase-3 is involved in the final stages of

apoptosis, participating in the amplification of intracellular

apoptotic signals as a consequence of the caspase cascade induced

by both intrinsic and extrinsic signaling (26). In the present study, it was found

that HG prevents caspase-3 activation and, therefore, apoptosis,

which explains the increased chemoresistance to cisplatin (Fig. 1). HG induces apoptosis in normal

cells; however, in cancer cells, HG prevents a variety of

proapoptotic mechanisms and promotes their proliferation and

invasiveness (4,6,28).

Additionally, the microarray analysis indicated that HG prevents

the cytotoxic action of cisplatin through the increased expression

of genes related to cell survival. (TNFSF7 and TRAF1)

(Table II) (21), and inhibition of apoptosis

(XIAP and BCL2L2) (Table

II) (22,23), together with diminished expression

of proapoptotic factors (BIK, PDCD8, PDCD5,

BNIP1, DAPK1 and CCAR2) (24,25).

The overexpression of BCL2L2 has been associated with an

aggressive and radioresistant BC phenotype (22).

Genes involved in metabolism are associated with

chemoresistance. Diabetes and hyperglycemia are frequently

associated with metabolic disorders. The data suggest that cancer

metabolism is intimately linked to drug resistance. The enrichment

analysis indicates the differential expression of numerous genes

for components of membranes and ribosomes in HG conditions. The

first is related to metabolite and ion transporters, and suggests

the reprogramming of solute interchange (ions and nutrients)

through the cell membranes. The second could be associated with the

increased synthesis of proteins.

The reprogramming of membrane transport is

suggested because of changes in the expression of 27 solute carrier

transporters (SLC) and 10 ATP-dependent transporters in the HG

condition (Tables II, SI and SII). The overexpression of SLC that

controls the entry of essential amino acids, monocarboxylates,

vitamins, glucose, nucleotides and organic cations indicates an

increased flux of nutrients, favoring the biosynthetic and

energetic demands of cancer cells. The SLC may be novel therapeutic

targets and predictive markers of chemoresistance. Among the

transporter-coding genes upregulated in the HG condition,

SLC6A6 (4.05 fold) and SLC39A7 (1.57-fold) have been

related to multidrug and cisplatin resistance in colorectal and

non-small cell lung cancers (16,29).

The dysregulation of genes coding for ribosomal

proteins promotes BC metastasis. Among them, RPS13 was

upregulated more than 2-fold during HG treatment and promoted drug

resistance in gastric cancer cells, suppressing apoptosis (17).

Recently, changes in lipid metabolism have been

recognized as important mediators of drug resistance. The gene

coding for 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 1

(AGPAT1) was the most highly overexpressed in HG. It is

highly expressed in breast tumor tissues, and it has been proposed

as a component of a gene signature for prognosis in BC (30). More studies are required to

determine its role in chemoresistance under HG conditions; some

members of the AGPAT gene family are upregulated in multiple

cancers and are associated with drug resistance and poor prognosis

(31).

Crosstalk between different oncogenic signaling

pathways in hyperglycemia. The metabolic alterations and

changes in gene expression induced by HG suggest the implication of

multiple signaling pathways that favor an aggressive phenotype and

chemoresistance in MDA-MB-231 cells. RT-qPCR confirmed the

overexpression of TSPAN1 and FZD3 genes, and several

studies suggested their role in cancer progression and

chemoresistance. TSPAN-1 promotes the proliferation and development

of a migratory-invasive phenotype through the induction of EMT and

activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling (32). In addition, the suppression of

TSPAN1 expression prevented BC tumor growth in mice

(18). These data are in agreement

with the high expression of TSPAN1 and FZD3 proteins in breast

ductal carcinoma in women of reproductive age (Fig. 3).

The finding that FZD3 and other members of

the Wnt canonical signaling [WNT1, FZD-4, disheveled 2

(DVL2), lymphoid enhancer factor 1 (LEF1) and

LRP8] were overexpressed in a hyperglycemic microenvironment

indicates the participation of Wnt signaling in the promotion of an

aggressive and chemoresistant phenotype by hyperglycemia, which was

supported by the enrichment and the PPI analyses. The altered

expression of genes of the Wnt pathway has been related to cancer

progression and poor prognosis (33,34).

WNT1 can induce transformation of the mouse mammalian cell line

C57MG (34). The expression of

WNT1 and LEF1 is upregulated in human breast

carcinoma (35). Whereas the

upregulation of FZD4 in glioma cells is correlated with

resistance to drug-induced cell death, partly due to the activation

of Wnt/β-catenin and downregulation of proapoptotic genes

(CASP3 and PDCD4) (36). The silencing of LRP8 by

interference RNA attenuates Wnt/β-catenin, decreases the metastatic

potential, and sensitizes BC cells to chemotherapy (37). As a consequence of the activation of

the Wnt pathway, LEF-1 and T cell factor (TCF) form a complex and

activate the expression of genes such as MDR1, C-MYC,

MET, MMP7, C-JUN and CCND1,

contributing to carcinogenesis and tumor progression in several

cancers (33,35). In MCF7 BC cells, LEF1 induces

resistance to docetaxel (DTX), and the inhibition of LEF1 with

quercetin reestablishes sensitivity to DTX (38). LEF1 is a transcription factor that

controls gene expression dependent or independent of Wnt/β-catenin

signaling and increases the expression of EMT effectors, such as

snail, vimentin and N-cadherin; the gene that encodes N-cadherin,

CDH2, was also found to be overexpressed in the HG condition

(Table SI). The potential role of

the Wnt pathway in the promotion of BC under hyperglycemic

conditions requires further studies.

The non-canonical signaling of Wnt can also be

implicated in the promotion of BC by hyperglycemia. Two genes that

encode CDC42 effectors were overexpressed by 2-fold in HG

conditions, including CDC42 binding protein kinase alpha and CDC42

small effector 1. The binding of WNT1 with FZD-3 induces the

activation of CDC42 in a β-catenin independent signaling, and CDC42

induces the reorganization of the cytoskeleton and cell migration

(39).

As the PPI indicates, the ATM-dependent

DNA-repairing pathway is of special interest, considering that

platinum salts are DNA-damaging agents. ATM improves the

ability to repair double-strand DNA breaks and can lead to

increased resistance to DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents, such

as platinum salts (40).

Potential genes associated with

chemoresistance induced by hyperglycemia

Through the evaluation of hub genes with a greater

number of interactions (Fig. 4),

the survival of TNBC patients using the KM plotter (Fig. 5) and coexpression analysis (Fig. 6), the authors propose YBX3 as

a central regulator positively correlated with AREG,

APP and FZD3, suggesting that these genes may

participate in a signaling network that promotes proliferation,

invasion and therapy resistance under hyperglycemic conditions. In

particular, YBX3 and AREG showed significant

prognostic value, as their high expression was associated with

reduced survival in patients with BC, highlighting their potential

as biomarkers of poor outcome (Fig.

5).

By contrast, APP and CDH2 did not

reach statistical significance in survival analyses, but

coexpression studies demonstrated that both genes are positively

correlated with YBX3 (Fig.

6). This finding suggests that APP and CDH2 may

not act as independent prognostic markers, but rather as

cooperative elements within YBX3-driven regulatory networks,

thereby contributing indirectly to tumor progression and

aggressiveness. Importantly, recent studies have shown that

YBX3 is overexpressed in multiple cancer types and

contributes to chemoresistance by regulating transcriptional and

translational programs involved in EMT, proliferation, and survival

pathways (19,41,42).

Moreover, YBX3 regulates the expression of growth factors and

ligands such as AREG, creating a positive feedback loop that

amplifies growth factor signaling, enhances EMT, and promotes

chemoresistance (43).

AREG is the primary EGFR ligand in MDA-MB-231

cells, and its binding to EGFR promotes BC growth and metastasis

(44). APP overexpression drives

EMT, proliferation and migration/invasion in BC cells, and it has

been proposed as a risk factor for lymph node metastasis and poor

prognosis in non-luminal BCs, including TNBC (45). CDH2 is a mesenchymal marker induced

by EMT that facilitates migration and invasion, and its high

expression correlates with poor prognosis in invasive

micropapillary BC (46,47).

Taken together, these findings suggest that while

AREG and CDH2 emerge as potential prognostic

biomarkers, APP and CDH2 may act primarily as

modulators of YBX3-driven transcriptional networks that

support tumor progression rather than serving as independent

prognostic indicators. Nevertheless, despite these associations,

the current evidence remains insufficient to establish these hub

genes as reliable biomarkers, underscoring the need for further

validation in larger patient cohorts and in-depth functional

studies.

It must be considered that an increase in the mRNA

level of a gene is not always followed by an increase in the

codified protein, and the protein generally realizes a function in

metabolism, secretion, or gene expression regulation. This

situation limits the conclusions of the estimations of the OS based

on mRNA values, as our data were derived from the KM plot

analysis.

Therapeutic implications and resistance bypass

strategies. The present results provide a foundation for

therapeutic strategies aimed at overcoming hyperglycemia-induced

chemoresistance in TNBC. Previous studies have shown that

inhibitors or interfering RNAs targeting YBX3 increase

chemosensitivity, highlighting a promising approach for TNBC

(19,42). Other potential therapeutic targets

include metabolic reprogramming and transporter activity,

considering the SLC6A6, SLC39A7 and RPS13

genes (16,17,29),

which are overexpressed in HG and aforementioned. Pharmacological

inhibition of these transporters, or modulation of glucose and

lipid metabolism, could sensitize TNBC cells to chemotherapy.

Combined strategies that target metabolic and oncogenic signaling

pathways may prove particularly effective. The inhibition of the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway or ATM-mediated DNA repair, in combination

with chemotherapy, could synergistically reduce tumors. These

findings support a framework for personalized combinatorial

therapies in diabetic patients with BC, integrating metabolic

modulators, inhibitors of YBX3-regulated networks, and

conventional chemotherapeutics to overcome resistance and improve

clinical outcomes.

Limitations of the present study. The

present study has potential limitations. It was based on the

analysis of the changes induced by HG in an invasive BC cell line,

using an in vitro experimental and bioinformatics approach.

Although the MDA-MB-231 cell line has been widely used as a model

of invasive BC, it does not represent the genetic heterogeneity of

invasive breast tumors. Therefore, the current findings need to be

validated in other experimental models and clinical cohorts.

However, the present study provides important insights and allows

us to better understand the behavior of this type of cancer under

HG conditions, as well as to identify potential signaling pathways

and genes associated with chemoresistance and prognosis in patients

with T2DM.

Although the use of HPRT as a housekeeping

gene is considered unreliable for comparing the gene expression

between cancerous and non-cancerous tissues (48), this gene has been recommended in

hyperglycemic conditions (13), and

its expression is moderately stable in BC cell lines (12), although in hyperglycemic conditions,

it has been validated in other types of cells. Therefore, the use

of an additional reference gene is recommended to further

consolidate the overexpression of TSPAN and FZD3

genes.

The present findings and bibliographic references

suggest that TSPAN1 and FZD3 play an important role

in the induction of chemoresistant and invasive phenotypes by HG

(18,32). However, gene knockdown experiments

are required to better understand their roles.

The clinical implications were partially validated

using public patient datasets and informatics platforms; however,

these platforms are generally based on non-diabetic patients, and

the estimation of the effect of selected overexpressed genes on OS

was therefore performed in non-diabetic conditions. These results

should be interpreted with caution, highlighting the need for

further validation in diabetic patient cohorts.

Additionally, both diabetes and cancer are complex

processes involving multiple genetic and environmental contexts;

therefore, further studies are required to validate the clinical

implications of our findings. These include validation at both

protein (western blotting and IHC) and mRNA (RT-qPCR) levels of

overexpressed genes (FZD3 and TSPAN1), as well as of

potential genes associated with chemoresistance and prognosis

(AREG and YBX3) in breast tumor tissues of diabetic

patients.

In addition, changes in gene expression and the

induction of cisplatin chemoresistance by diabetes in a mouse model

of syngeneic BC are currently studied, and patient-derived

organoids can be used to analyze cisplatin action under HG

conditions in human tissues. Finally, the correlation of the

selected genes and clinical outcomes should be studied in other

patient cohorts, preferably in diabetic patients with BC.

In conclusion, these data indicate that alterations

in gene expression induced by hyperglycemia lead to changes in the

metabolism of cancer cells, affecting a variety of processes that

promote a more aggressive phenotype through the activation of

Wnt/β-catenin, NF-κB survival, angiogenesis and PI3K/AKT signaling,

contributing to enhanced proliferation, migration, invasion and

inhibition of apoptosis. Some potential biomarkers of cisplatin

resistance under hyperglycemia could be AREG and

YBX3.

Supplementary Material

Upregulated genes in MDA-MB-231 cells

supplemented with glucose 30 mmo/l.

Downregulated genes in MDA-MB-231

cells supplemented with glucose 30 mmo/l.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms Lorena Chávez,

Dr José Luis Santillán, Mr Simón Guzmán and Dr Jorge Ramírez for

performing the microarray analysis at the Instituto de Fisiología

Celular, National Autonomous University of Mexico. The authors

thank student Mr Jael Gutiérrez Savedra for his technical

assistance, and Dr Leticia Moreno Fierros for her technical advice

[both are affiliated to the National Autonomous University of

Mexico (UNAM), FES-Iztacala].

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Programa de

Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica

(PAPIIT), Dirección General de Apoyo al Personal Académico (DGAPA),

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), (grant nos.

IN223121 and IN220024), by the Financing for Research of Women

Scientists (grant no. FICDTEM-2023-56) and by the Fiscal Resources

Program for Research of the National Institute of Pediatrics (grant

no. 2020/016).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

found in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number

GSE136277 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE136277.

The data generated in the present study are included in the figures

and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

ARVR, MGMH and LABG contributed to the conception

and design of the study. ARVR, MGMH, LAFL, MÁVF, RREG and JRPB

performed material preparation, data collection and analysis. ARVR

and LABG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors

commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript. ARVR and

LABG confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ryu TY, Park J and Scherer PE:

Hyperglycemia as a risk factor for cancer progression. Diabetes

Metab J. 38:330–336. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Varghese E, Samuel SM, Líšková A, Samec M,

Kubatka P and Büsselberg D: Targeting glucose metabolism to

overcome resistance to anticancer chemotherapy in breast cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 12(2252)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Qiu J, Zheng Q and Meng X: Hyperglycemia

and chemoresistance in breast cancer: From cellular mechanisms to

treatment response. Front Oncol. 11(628359)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Flores-López LA, Martínez-Hernández MG,

Viedma-Rodríguez R, Díaz-Flores M and Baiza-Gutman LA: High glucose

and insulin enhance uPA expression, ROS formation and invasiveness

in breast cancer-derived cells. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 39:365–378.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Bergandi L, Mungo E, Morone R, Bosco O,

Rolando B and Doublier S: Hyperglycemia promotes chemoresistance

through the reduction of the mitochondrial DNA damage, the

Bax/Bcl-2 and Bax/Bcl-XL ratio, and the cells in sub-G1 phase due

to antitumoral drugs induced-cytotoxicity in human colon

adenocarcinoma cells. Front Pharmacol. 9(866)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Viedma-Rodríguez R, Martínez-Hernández MG,

Flores-López LA and Baiza-Gutman LA: Epsilon-aminocaproic acid

prevents high glucose and insulin induced-invasiveness in

MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, modulating the plasminogen

activator system. Mol Cell Biochem. 437:65–80. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Huang Y, Hong W and Wei X: The molecular

mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression

and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 15(129)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Panigrahi G, Candia J, Dorsey TH, Tang W,

Ohara Y, Byun JS, Minas TZ, Zhang AL, Ajao A, Cellini A, et al:

Diabetes-associated breast cancer is molecularly distinct and shows

a DNA damage repair deficiency. JCI Insight.

8(e170105)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ashrafizadeh M, Zarrabi A, Hushmandi K,

Kalantari M, Mohammadinejad R, Javaheri T and Sethi G: Association

of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) with cisplatin

resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 21(4002)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Frossard M, Blank D, Joukhadar Ch, Bayegan

K, Schmid R, Luger A and Müller M: Interstitial glucose in skeletal

muscle of diabetic patients during an oral glucose tolerance test.

Diabet Med. 22:56–60. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Schmittgen TD and Livak KJ: Analyzing

real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc.

3:1101–1108. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gorji-Bahri G, Moradtabrizi N, Vakhshiteh

F and Hashemi A: Validation of common reference genes stability in

exosomal mRNA-isolated from liver and breast cancer cell lines.

Cell Biol Int. 45:1098–1110. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Liu X, Xie J, Liu Z, Gong Q, Tian R and Su

G: Identification and validation of reference genes for

quantitative RT-PCR analysis of retinal pigment epithelium cells

under hypoxia and/or hyperglycemia. Gene. 580:41–46.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Gorodkin J and

Jensen LJ: Cytoscape StringApp: Network analysis and visualization

of proteomics data. J Proteome Res. 18:623–632. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT and

Lin CY: cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from

complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 8 (Suppl 4)(S11)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Yasunaga M and Matsumura Y: Role of SLC6A6

in promoting the survival and multidrug resistance of colorectal

cancer. Sci Rep. 4(4852)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Shi Y, Zhai H, Wang X, Han Z, Liu C, Lan

M, Du J, Guo C, Zhang Y, Wu K and Fan D: Ribosomal proteins S13 and

L23 promote multidrug resistance in gastric cancer cells by

suppressing drug-induced apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 296:337–346.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Garcia-Mayea Y, Mir C, Carballo L,

Sánchez-García A, Bataller M and ME LL: TSPAN1, a novel tetraspanin

member highly involved in carcinogenesis and chemoresistance.

Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1877(188674)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Tong C, Qu K, Wang G, Liu R, Duan B, Wang

X and Liu C: Knockdown of DNA-binding protein A enhances the

chemotherapy sensitivity of colorectal cancer via suppressing the

Wnt/β-catenin/Chk1 pathway. Cell Biol Int. 44:2075–2085.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lánczky A and Győrffy B: Web-based

survival analysis tool tailored for medical research (KMplot):

Development and implementation. J Med Internet Res.

23(e27633)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Liu N, Sheng X, Liu Y, Zhang X and Yu J:

Increased CD70 expression is associated with clinical resistance to

cisplatin-based chemotherapy and poor survival in advanced ovarian

carcinomas. Onco Targets Ther. 6:615–619. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hartman ML and Czyz M: BCL-w: Apoptotic

and non-apoptotic role in health and disease. Cell Death Dis.

11(260)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bano D and Prehn JHM: Apoptosis-inducing

factor (AIF) in physiology and disease: The tale of a repented

natural born killer. EBioMedicine. 30:29–37. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zheng HC: The molecular mechanisms of

chemoresistance in cancers. Oncotarget. 8:59950–59964.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Gozuacik D, Bialik S, Raveh T, Mitou G,

Shohat G, Sabanay H, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T and Kimchi A:

DAP-kinase is a mediator of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced

caspase activation and autophagic cell death. Cell Death Differ.

15:1875–1886. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Porter AG and Jänicke RU: Emerging roles

of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 6:99–104.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Viedma-Rodríguez R, Martínez-Hernández MG,

Martínez-Torres DI and Baiza-Gutman LA: Epithelial mesenchymal

transition and progression of breast cancer promoted by diabetes

mellitus in mice are associated with increased expression of

glycolytic and proteolytic enzymes. Horm Cancer. 11:170–181.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Vaughn AE and Deshmukh M: Glucose

metabolism inhibits apoptosis in neurons and cancer cells by redox

inactivation of cytochrome c. Nat Cell Biol. 10:1477–1483.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wu DM, Liu T, Deng SH, Han R and Xu Y:

SLC39A4 expression is associated with enhanced cell migration,

cisplatin resistance, and poor survival in non-small cell lung

cancer. Sci Rep. 7(7211)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ren X, Cui H, Wu J, Zhou R, Wang N, Liu D,

Xie X, Zhang H, Liu D, Ma X, et al: Identification of a combined

apoptosis and hypoxia gene signature for predicting prognosis and

immune infiltration in breast cancer. Cancer Med. 11:3886–3901.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wen P, Wang R, Xing Y, Ouyang W, Yuan Y,

Zhang S, Liu Y and Peng Z: The prognostic value of the GPAT/AGPAT

gene family in hepatocellular carcinoma and its role in the tumor

immune microenvironment. Front Immunol. 14(1026669)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wu Y, Chen W, Gong Y, Liu H and Zhang B:

Tetraspanin 1 (TSPAN1) promotes growth and transferation of breast

cancer cells via mediating PI3K/Akt pathway. Bioengineered.

12:10761–10770. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Merikhian P, Eisavand MR and Farahmand L:

Triple-negative breast cancer: Understanding Wnt signaling in drug

resistance. Cancer Cell Int. 21(419)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wong GT, Gavin BJ and McMahon AP:

Differential transformation of mammary epithelial cells by Wnt

genes. Mol Cell Biol. 14:6278–6286. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ayyanan A, Civenni G, Ciarloni L, Morel C,

Mueller N, Lefort K, Mandinova A, Raffoul W, Fiche M, Dotto GP and

Brisken C: Increased Wnt signaling triggers oncogenic conversion of

human breast epithelial cells by a Notch-dependent mechanism. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:3799–3804. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Jin X, Jeon HY, Joo KM, Kim JK, Jin J, Kim

SH, Kang BG, Beck S, Lee SJ, Kim JK, et al: Frizzled 4 regulates

stemness and invasiveness of migrating glioma cells established by

serial intracranial transplantation. Cancer Res. 71:3066–3075.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Lin CC, Lo MC, Moody R, Jiang H, Harouaka

R, Stevers N, Tinsley S, Gasparyan M, Wicha M and Sun D: Targeting

LRP8 inhibits breast cancer stem cells in triple-negative breast

cancer. Cancer Lett. 438:165–173. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Prieto-Vila M, Shimomura I, Kogure A,

Usuba W, Takahashi RU, Ochiya T and Yamamoto Y: Quercetin inhibits

Lef1 and resensitizes docetaxel-resistant breast cancer cells.

Molecules. 25(2576)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Tümen D, Heumann P, Huber J, Hahn N, Macek

C, Ernst M, Kandulski A, Kunst C and Gülow K: Unraveling cancer's

Wnt signaling: Dynamic control through protein kinase regulation.

Cancers (Basel). 16(2686)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Galland L, Ballot E, Mananet H, Boidot R,

Lecuelle J, Albuisson J, Arnould L, Desmoulins I, Mayeur D,

Kaderbhai C, et al: Efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy in

metastatic breast cancer and HRD biomarkers: Utility of exome

sequencing. NPJ Breast Cancer. 8(28)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Wang C, You Z, He Y and Chen X:

Identification of RNA-binding protein YBX3 as an oncogene in clear

cell renal cell carcinoma. Funct Integr Genomics.

23(225)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Sun Y, Li Z, Wang W, Zhang X, Li W, Du G,

Yin J, Xiao W and Yang H: Identification and verification of YBX3

and its regulatory gene HEIH as an oncogenic system: A

multidimensional analysis in colon cancer. Front Immunol.

13(957865)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Panupinthu N, Yu S, Zhang D, Zhang F,

Gagea M, Lu Y, Grandis JR, Dunn SE, Lee HY and Mills GB:

Self-reinforcing loop of amphiregulin and Y-box binding protein-1

contributes to poor outcomes in ovarian cancer. Oncogene.

33:2846–2856. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Bolitho C, Moscova M, Baxter RC and Marsh

DJ: Amphiregulin increases migration and proliferation of

epithelial ovarian cancer cells by inducing its own expression via

PI3-kinase signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol.

533(111338)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wu X, Chen S and Lu C: Amyloid precursor

protein promotes the migration and invasion of breast cancer cells

by regulating the MAPK signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med.

45:162–174. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Cao ZQ, Wang Z and Leng P: Aberrant

N-cadherin expression in cancer. Biomed Pharmacother.

118(109320)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ge R, Wang Z, Wu S, Zhuo Y, Otsetov AG,

Cai C, Zhong W, Wu CL and Olumi AF: Metformin represses cancer

cells via alternate pathways in N-cadherin expressing vs N-cadherin

deficient cells. Oncotarget. 6:28973–28987. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Townsend MH, Felsted AM, Ence ZE, Piccolo

SR, Robison RA and O'Neill KL: Falling from grace: HPRT is not

suitable as an endogenous control for cancer-related studies. Mol

Cell Oncol. 6(1575691)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|