Introduction

Small-interfering RNA (siRNA) therapeutics are

synthetic RNA duplexes designed to target and degrade specific mRNA

(1,2). Cationic liposomes, commonly used as

vectors to deliver siRNA, can form complexes called siRNA

lipoplexes (3,4). However, upon systemic administration,

these positively charged siRNA lipoplexes bind blood components,

including erythrocytes (5), forming

agglutinates that are sequestered by lung capillaries (6). To avoid this, poly(ethylene glycol)

modification (PEGylation) of siRNA lipoplexes is commonly applied

to improve circulating stability (5,7).

However, the presence of PEG on lipoplex surfaces also poses an

obstacle, widely known as the ‘PEG dilemma’, because PEGylation

reduce cellular uptake and endosomal escape, thereby compromising

overall gene-silencing efficacy (8,9).

To minimize interactions between siRNA lipoplexes

and blood components, their surface charge should be negative or

neutral. Negatively charged ternary siRNA lipoplexes have been

created using anionic liposomes composed of

dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol (DOPG) and

dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) with Ca2+ ions

and siRNA, where Ca2+ electrostatically binds the

phosphate groups of DOPG and siRNA (10,11).

Alternatively, biodegradable anionic polymer coatings, such as

hyaluronic acid, chondroitin sulfate, and poly-L-glutamic acid, can

convert cationic siRNA lipoplexes into anionic lipoplexes (12,13).

Meanwhile, neutral or anionic siRNA lipid nanoparticles can be

generated by rapidly mixing organic solvent-dissolved phospholipid,

cholesterol, PEG-lipid, and ionizable cationic lipid, with aqueous

solution-dissolved siRNA via microfluidics (14,15).

Although these approaches prevent blood component agglutination,

they require specialized preparation equipment.

A single-step modified ethanol injection (MEI)

protocol was previously developed to prepare cationic siRNA

lipoplexes (16,17). This method involves the rapid

injection of siRNA dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

into a lipid-ethanol solution, resulting in efficient formation of

small, uniform siRNA lipoplexes without the need for specialized

equipment. In the present study, a two-step MEI approach is

employed to generate anionic siRNA lipoplexes. Their gene-silencing

efficiency and interaction with erythrocytes are evaluated.

Materials and methods

Materials

1,2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl

sulfate salt (DOTAP) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.

(Alabaster, AL, USA). Dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide (DDAB;

cat.no. DC-1-18),

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide (cat. no. DC-1-16), and

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide (cat. no. TC-1-12) were purchased from Sogo Pharmaceutical

Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). DOPE and polyethylene glycol-cholesteryl

ether (PEG-Chol, average PEG molecular weight: 1,600) were

purchased from NOF Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Cholesteryl

hemisuccinate (CHS) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis,

MO, USA).

Firefly luciferase (Luc)-specific siRNA (target

sequence: hLuc+; GenBank accession no. AY535007.1),

firefly pGL3 Luc-specific siRNA (target sequence: Luc+;

GenBank accession no U47295.2), non-silencing control siRNA (Cont

siRNA), and cyanine 5 (Cy5)-conjugated Cont siRNA (Cy5-siRNA) were

synthesized by Sigma Genosys (Tokyo, Japan) as previously described

(17-19).

AlexaFluor555-labeled Allstars negative control siRNA (AF555-siRNA)

was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA). Hoechst 33342,

trihydrochloride trihydrate, was purchased from Thermo Fisher

Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell culture

Human breast cancer MCF-7-Luc cells stably

expressing Luc (hLuc+) were gifted by Dr. Kenji Yamato

(University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan). Short tandem repeat (STR)

DNA profile analysis verified that the MCF-7-Luc cells utilized in

this study were identical to the MCF-7 cells registered with the

Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (National

Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Ibaraki, Osaka, Japan). Human

cervical carcinoma HeLa-Luc cells (CVCL_5J41) stably expressing Luc

(Luc+) were acquired from Caliper Life Sciences

(Hopkinton, MA, USA).

MCF-7-Luc cells were maintained in Roswell Park

Memorial Institute-1640 medium (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical

Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10%

heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific)

and 1.2 mg/ml G418 sulfate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX,

USA) in a humidified incubator at 37˚C and 5% CO2.

HeLa-Luc cells were cultured under identical conditions in Eagle's

minimum essential medium (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries,

Ltd.) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 µg/ml kanamycin.

Preparation of cationic and anionic

siRNA lipoplexes using MEI method

To prepare cationic siRNA lipoplexes, a

lipid-ethanol solution was prepared by dissolving cationic lipid

(DOTAP, DDAB, DC-1-16, or TC-1-12), DOPE, and PEG-Chol in ethanol

at a molar ratio of 49.5:49.5:1 (2 mg/ml concentration for the

cationic lipid), following previously reported methods (17). For example, 2 mg TC-1-12, 1.53 mg

DOPE, and 0.08 mg PEG-Chol were dissolved in 1 ml of ethanol.

Subsequently, 50 pmol siRNA solution was transferred to a tube

containing 100 µl of PBS (pH 7.4). The resulting solution was

rapidly added to the lipid-ethanol solution (3.1 µl for LP-DOTAP,

2.3 µl for LP-DC116, 2.5 µl for LP-DDAB, and 3.9 µl for LP-TC112)

in another tube to achieve a charge ratio (+:-) of 4:1, based on

previous reports (16,17). The charge ratio (+:-) refers to the

molar ratio of quaternary amines in the cationic lipid to the siRNA

phosphates.

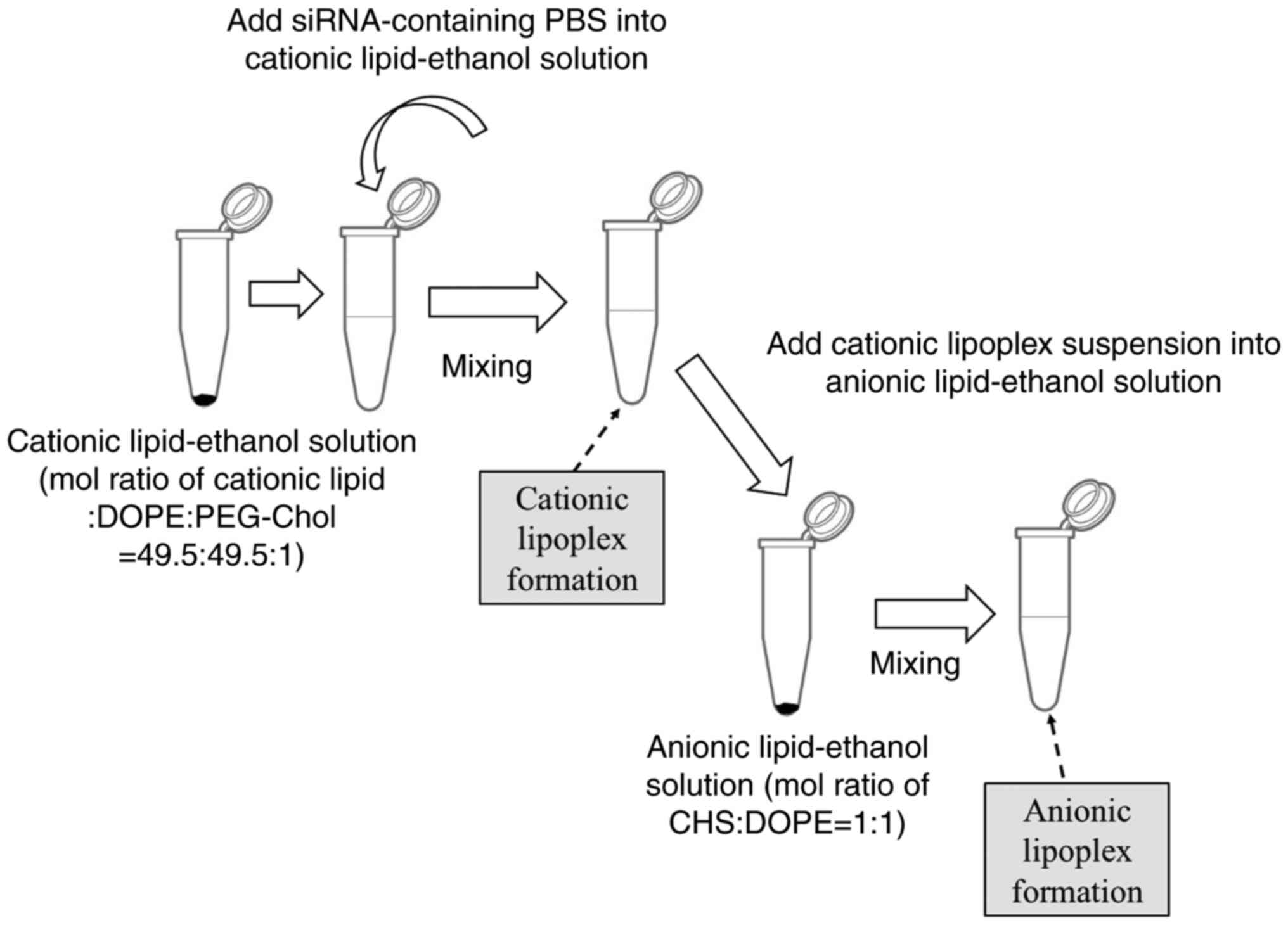

To prepare anionic siRNA lipoplexes, another

lipid-ethanol solution was prepared by dissolving 2 mg CHS and 3.06

mg DOPE (molar ratio of 1:1) in 1 ml of ethanol. The lipid-ethanol

solution was then mixed with a cationic lipoplex suspension

containing 50 pmol siRNA. Volumes of 1.95 and 3.89 µl of the

lipid-ethanol solution were used to achieve charge ratios (+:-) of

1:1 and 1:2 (1CHS and 2CHS), respectively. The charge ratio (+:-)

was calculated as the molar ratio of cationic lipids to CHS.

Measurement of liposome and siRNA

lipoplex sizes

Cationic and anionic siRNA lipoplexes containing 5

µg Cont siRNA were prepared using the MEI method. Cationic and

anionic liposomes were prepared using the same amount of

lipid-ethanol solution as the siRNA lipoplexes but without siRNA.

The liposomes and siRNA lipoplexes were diluted threefold with

water. Subsequently, the particle size, polydispersity index (PDI),

and ζ-potential of the liposomes and siRNA lipoplexes were measured

using a light-scattering photometer (ELS-Z2; Otsuka Electronics

Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

Evaluation of Luc knockdown efficiency

in Luc siRNA lipoplexes

Anionic and cationic siRNA lipoplexes containing 50

pmol of Cont and Luc siRNAs were diluted in culture medium

supplemented with 10% FBS to a final siRNA concentration of 50 nM.

The siRNA lipoplexes were added to MCF-7-Luc and HeLa-Luc cells in

12-well culture plates. Luc activity [counts per second (cps)] was

determined 48 h post-transfection as previously described (5). Luc activity (%) was calculated

relative to that (cps/µg protein) of untreated cells.

Cytotoxicity after transfection with

anionic and cationic lipoplexes

MCF-7-Luc and HeLa-Luc cells were seeded in 96-well

culture plates at a density of 1x104 cells/well. After

24 h of incubation at 37˚C, anionic and cationic lipoplexes

containing 50 pmol Cont siRNA were prepared using the MEI method.

The lipoplexes were diluted with culture medium containing 10% FBS

(final siRNA concentration: 50 nM) and subsequently added to the

cells (100 µl/well). Cytotoxicity was assessed 48 h

post-transfection using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo

Laboratories, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan), as previously reported

(20).

Cellular uptake of siRNA

lipoplexes

To quantify the amount of siRNA taken up by the

cells, MCF-7-Luc cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates at a

density of 1x105 cells/well. After 24 h of incubation at

37˚C, cationic and anionic lipoplexes containing 50 pmol

AF555-siRNA in 1 ml of culture medium were added to the cells

(final siRNA concentration: 50 nM). After 24-h incubation, the

plates were washed with PBS to remove unbound lipoplexes, and the

cells were lysed with cell lysis buffer (Pierce™ Luciferase Cell

Lysis Buffer; Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), followed by

centrifugation at 15,000 g for 10 sec at 4˚C. AF555-fluorescence

intensity [relative fluorescence unit (RFU)] in the supernatant

were then measured using a fluorescence microplate reader

(GloMax® Discover system, Promega Corporation, Madison,

WI, USA) at 525 nm of excitation and 580-640 nm of emission.

Protein concentrations of the supernatants were determined with

bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagent (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit;

Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The fluorescence intensity

of AF555-siRNA (RFU/µg protein) in the cells was calculated by

subtracting the background fluorescence (RFU/µg protein) of

untreated cells.

To observe the localization of siRNA in the cells,

MCF-7-Luc cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates at a density

of 1x105 cells/well. After 5 or 24 h of incubation at

37˚C, anionic and cationic lipoplexes containing 50 pmol Cy5-siRNA

in 1 ml of culture medium were added to the cells (final siRNA

concentration: 50 nM). At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were

fixed with Mildform 10N (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries,

Ltd.) for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were

incubated with 10 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 10 min to stain the

nuclei. Cy5-siRNA and nuclei within the cells were detected using

an Eclipse TS100-F fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation,

Tokyo, Japan) equipped with optical filters for Cy5 (excitation

filter: 620/60 nm, dichroic mirror: 660 nm, absorption filter:

700/75 nm) and Hoechst 33342 (excitation filter: 365/10 nm,

dichroic mirror: 400 nm, absorption filter: 400 nm).

Animal experiments

Animal experiments adhered to the Guide for the Care

and Use of Laboratory Animals of the U.S. National Institutes of

Health and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee of Hoshi University (Tokyo, Japan; approval number:

P24-151, Research period: from December 10, 2024, to February 28,

2025). The predetermined endpoint for experimental termination was

set as: the mice would be euthanized by cervical dislocation if the

solid tumor volume in a tumor-bearing mouse exceeded 2,000

mm3. However, this endpoint criterion was not applied to

any mice during the course of the study.

One eight-week-old female BALB/c mouse obtained from

Sankyo Labo Service Corporation, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) was maintained

in a temperature-controlled room (24˚C) at 55% relative humidity

under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle (08:00 to 20:00) with ad

libitum access to food and water.

Hemolysis and agglutination assay

Study on erythrocyte characteristics based on donor

sex shows that female donors have erythrocytes with greater

resilience to storage damage and hemolysis (21). Therefore, erythrocytes from female

mice were used. Total duration of the study was 1 day. Blood (0.2

ml) was collected from the jugular vein of one female BALB/c mouse

under anesthesia induced by isoflurane inhalation (4% gas-air

mixture for induction and 2% gas-air mixture for maintenance;

FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation). Immediately after the

blood collection, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation;

death was confirmed by cessation of heartbeat. Erythrocytes were

collected from the blood at 4˚C by centrifugation at 300 x g for 3

min and resuspended in PBS as a 2% (v/v) suspension of

erythrocytes.

To assess agglutination, cationic and anionic siRNA

lipoplexes containing 50 pmol Cont siRNA in 100 µl of PBS were

added to 100 µl of a 2% (v/v) erythrocyte suspension. After

incubating at 37˚C for 15 min, the sample was placed on a glass

slide, and agglutination was observed under a light microscope

(Eclipse TS100-F, Nikon Corporation).

To examine erythrocyte hemolysis induced by siRNA

lipoplexes, cationic and anionic siRNA lipoplexes containing 50

pmol Cont siRNA in 100 µl of PBS were added to 100 µl of a 2% (v/v)

erythrocyte suspension; the hemolysis proportion was calculated as

previously reported (22).

Erythrocytes suspended in water served as positive controls for

complete hemolysis (100% hemolysis).

Statistical analysis

Two groups were compared using an unpaired Student's

t-test. Multiple groups were compared using one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. All data were

analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0; GraphPad

Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), and statistical significance

was set at P<0.05.

Results

Characterization of cationic and

anionic siRNA lipoplexes

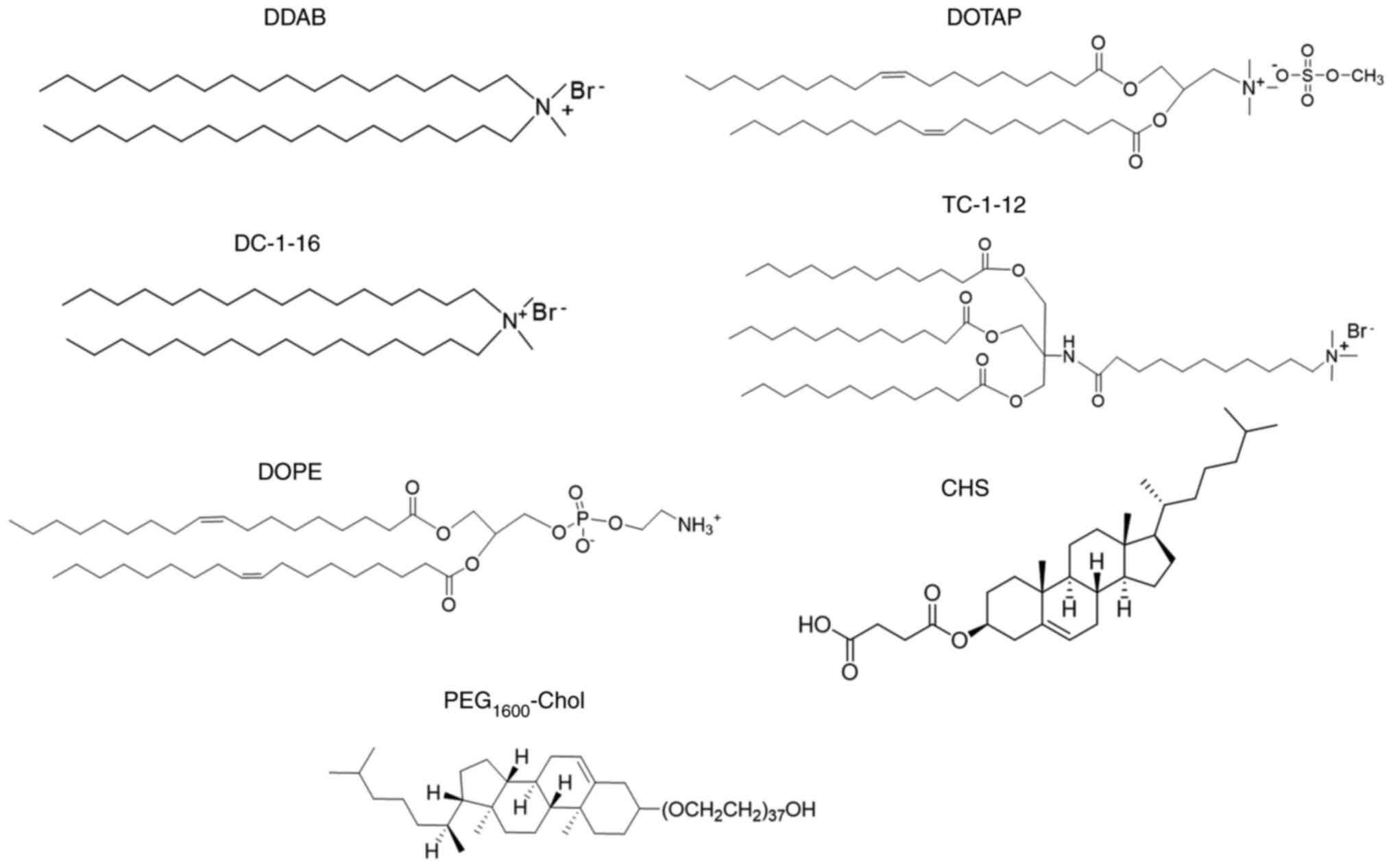

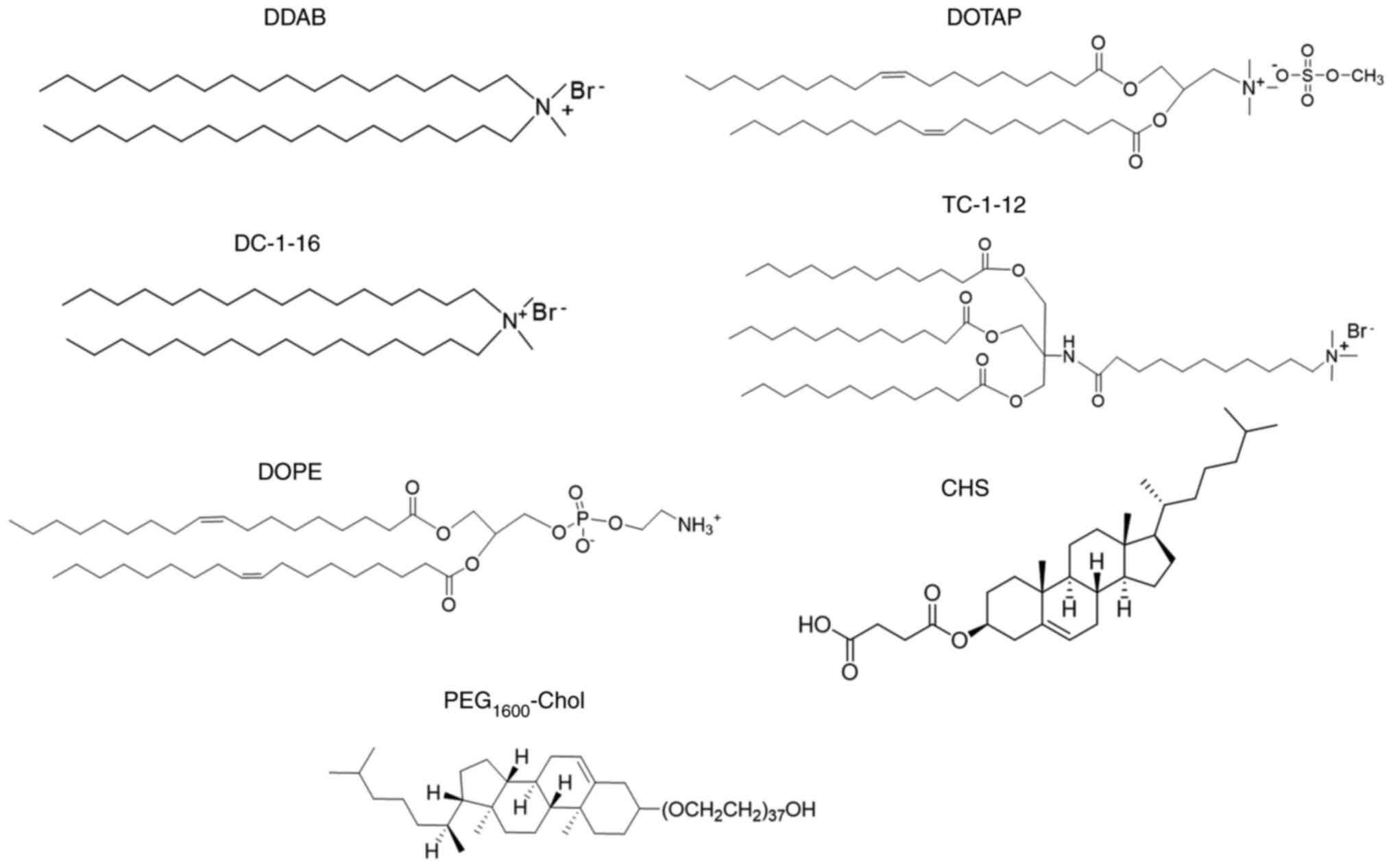

To prepare cationic siRNA lipoplexes, DOTAP,

DC-1-16, DDAB, and TC-1-12 were used as cationic lipids, with DOPE

as a neutral lipid and PEG-Chol as a PEG-lipid (Fig. 1). Cationic lipoplexes were formed by

the MEI method with a 49.5:49.5:1 molar ratio of cationic lipid,

DOPE, and PEG-Chol (Table I). The

resulting LP-DOTAP, LP-DC116, LP-DDAB, and LP-TC112 lipoplexes

measured 148, 224, 200, and 92 nm in size, respectively (PDI: 0.10,

0.08, 0.11, and 0.16, respectively), and had positive ζ-potentials

(~4.6-11 mV).

| Figure 1Structures of cationic lipids, anionic

lipid, neutral lipid and PEG-lipid. DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N, N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; DOPE,

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; CHS,

cholesteryl hemisuccinate; PEG-Chol, poly(ethylene glycol)

cholesteryl ether. |

| Table ISize and ζ-potential of cationic and

anionic siRNA lipoplexes prepared using modified ethanol injection

method. |

Table I

Size and ζ-potential of cationic and

anionic siRNA lipoplexes prepared using modified ethanol injection

method.

| Lipoplex | Liposomal

formulation (molar ratio) | Sizea, nm | PDI |

ζ-potentiala, mV |

|---|

| LP-DOTAP |

DOTAP/DOPE/PEG1600-Chol

(49.5:49.5:1.0) | 147.8±1.5 | 0.10±0.01 | 10.9±3.2 |

| LP-DOTAP-1CHS |

DOTAP/DOPE/CHS/PEG1600-Chol

(24.9:49.7:24.9:0.5) | 229.2±4.3 | 0.06±0.01 | -2.2±1.8 |

| LP-DOTAP-2CHS |

DOTAP/DOPE/CHS/PEG1600-Chol

(16.6:49.8:33.2:0.3) | 206.5±1.6 | 0.12±0.02 | -26.5±1.8 |

| LP-DC116 |

DC-1-16/DOPE/PEG1600-Chol

(49.5:49.5:1.0) | 223.5±1.6 | 0.08±0.01 | 11.1±0.6 |

| LP-DC116-1CHS |

DC-1-16/DOPE/CHS/PEG1600-Chol

(24.9:49.7:24.9:0.5) | 374.4±4.0 | 0.23±0.01 | 0.3±0.7 |

| LP-DC116-2CHS |

DC-1-16/DOPE/CHS/PEG1600-Chol

(16.6:49.8:33.2:0.3) | 228.5±0.5 | 0.30±0.01 | -16.2±4.6 |

| LP-DDAB |

DDAB/DOPE/PEG1600-Chol

(49.5:49.5:1.0) | 199.9±0.9 | 0.11±0.01 | 4.6±0.0 |

| LP-DDAB-1CHS |

DDAB/DOPE/CHS/PEG1600-Chol

(24.9:49.7:24.9:0.5) | 213.6±2.3 | 0.19±0.01 | -4.8±0.1 |

| LP-DDAB-2CHS |

DDAB/DOPE/CHS/PEG1600-Chol

(16.6:49.8:33.2:0.3) | 161.8±1.5 | 0.25±0.01 | -17.8±2.8 |

| LP-TC112 |

TC-1-12/DOPE/PEG1600-Chol

(49.5:49.5:1.0) | 91.9±0.4 | 0.16±0.02 | 8.0±1.3 |

| LP-TC112-1CHS |

TC-1-12/DOPE/CHS/PEG1600-Chol

(24.9:49.7:24.9:0.5) | 156.0±1.7 | 0.10±0.01 | -12.8±0.5 |

| LP-TC112-2CHS |

TC-1-12/DOPE/CHS/PEG1600-Chol

(16.6:49.8:33.2:0.3) | 145.7±2.8 | 0.08±0.02 | -19.5±1.5 |

To prepare anionic liposomes, CHS and DOPE were

mixed at a 1:1 ratio in ethanol. Using the MEI method, LP-CHS was

obtained with a particle size of 97 nm and a ζ-potential of -63 mV

(Table SI), indicating a strong

negative charge capable of neutralizing cationic charges.

To determine the optimal amount of CHS required to

neutralize cationic liposomes, anionic liposomes were prepared

using the two-step MEI method by sequentially combining a

lipid-ethanol solution of cationic lipid, DOPE, and PEG-Chol with

PBS without siRNA, followed by the addition of a CHS-DOPE

lipid-ethanol solution. CHS was incorporated at either equimolar

(1CHS) or double the molar amount (2CHS) relative to the cationic

lipid. Adding CHS at twice the molar ratio consistently restored a

negative charge to the liposomes (Table SI).

Anionic siRNA lipoplexes were prepared using a

two-step MEI method: a lipid-ethanol solution containing cationic

lipids, DOPE, and PEG-Chol was rapidly mixed with siRNA in PBS,

followed by the addition of a CHS-DOPE ethanol solution (Fig. 2). LP-DOTAP-1CHS, LP-DC116-1CHS, and

LP-DDAB-1CHS lipoplexes had near-neutral ζ-potentials (-4.8 to 0.3

mV), and increased sizes (230, 374, and 214 nm, respectively)

compared to lipoplexes without CHS (Table I). Meanwhile, their 2CHS

counterparts exhibited strongly negative ζ-potentials (-16.2 to

-26.5 mV) and smaller sizes (207, 229, and 162 nm, respectively).

LP-TC112-1CHS and LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes measured 156 and 146 nm

with ζ-potentials of -12.8 and -19.5 mV, respectively.

Luc activity suppression by cationic

and anionic Luc siRNA lipoplexes

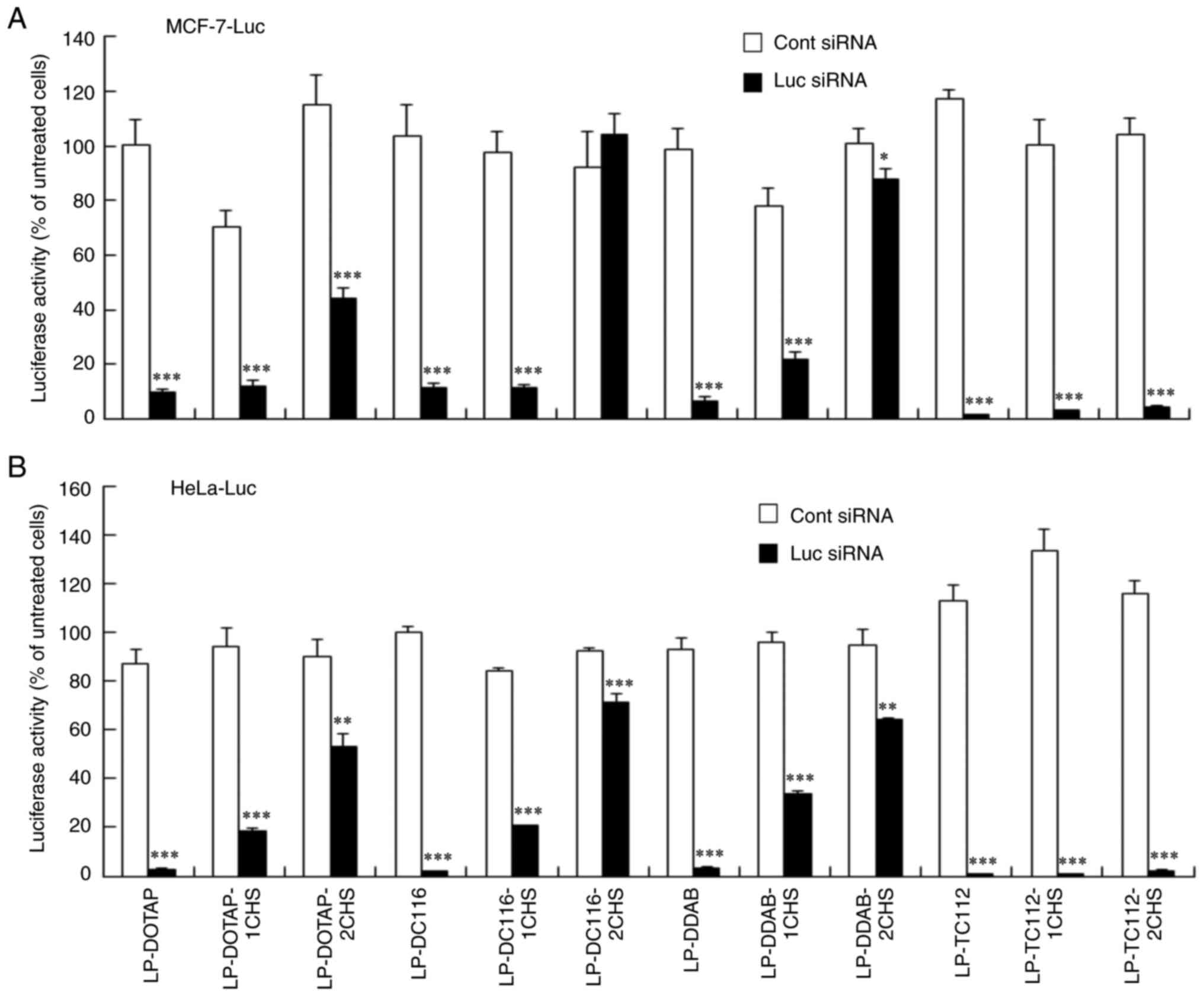

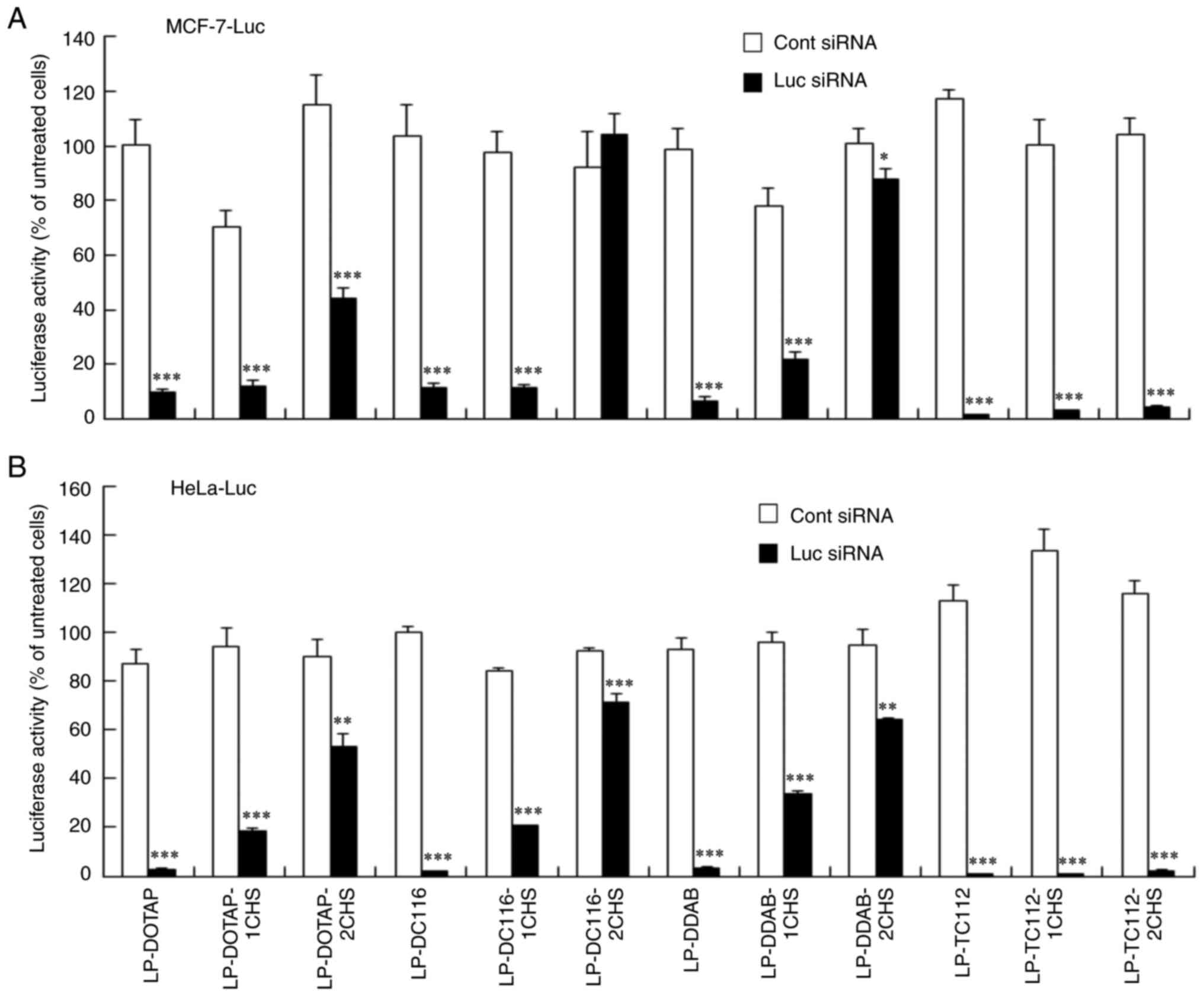

Cationic and anionic lipoplexes containing Luc siRNA

were transfected into MCF-7-Luc and HeLa-Luc cells, with Luc

activity measured 48 h post-transfection. Cationic siRNA lipoplexes

exhibited strong gene-silencing activity in both cell lines,

regardless of the cationic lipid type (Fig. 3A and B). However, for DOTAP, DC116, and DDAB

formulations, increasing CHS reduced silencing activity. Notably,

LP-DC116-2CHS and LP-DDAB-2CHS showed no silencing in MCF-7-Luc

cells. In contrast, LP-TC-112-1CHS and LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes did

not exhibit decreased gene silencing activity in either cell type

compared with LP-TC-112 lipoplexes.

| Figure 3Luc activity suppression by cationic

and anionic siRNA lipoplexes. Cationic and anionic lipoplexes

containing Cont and Luc siRNAs were prepared using the modified

ethanol injection method. These lipoplexes were then added to (A)

MCF-7-Luc and (B) HeLa-Luc cells at a final siRNA concentration of

50 nM. Luc activity was measured 48 h post-transfection. Data are

represented as the mean + standard deviation (n=3).

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. Cont siRNA. Luc, luciferase; siRNA,

small interfering RNA; Cont, control; LP, liposome; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N, N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; CHS, cholesteryl hemisuccinate. |

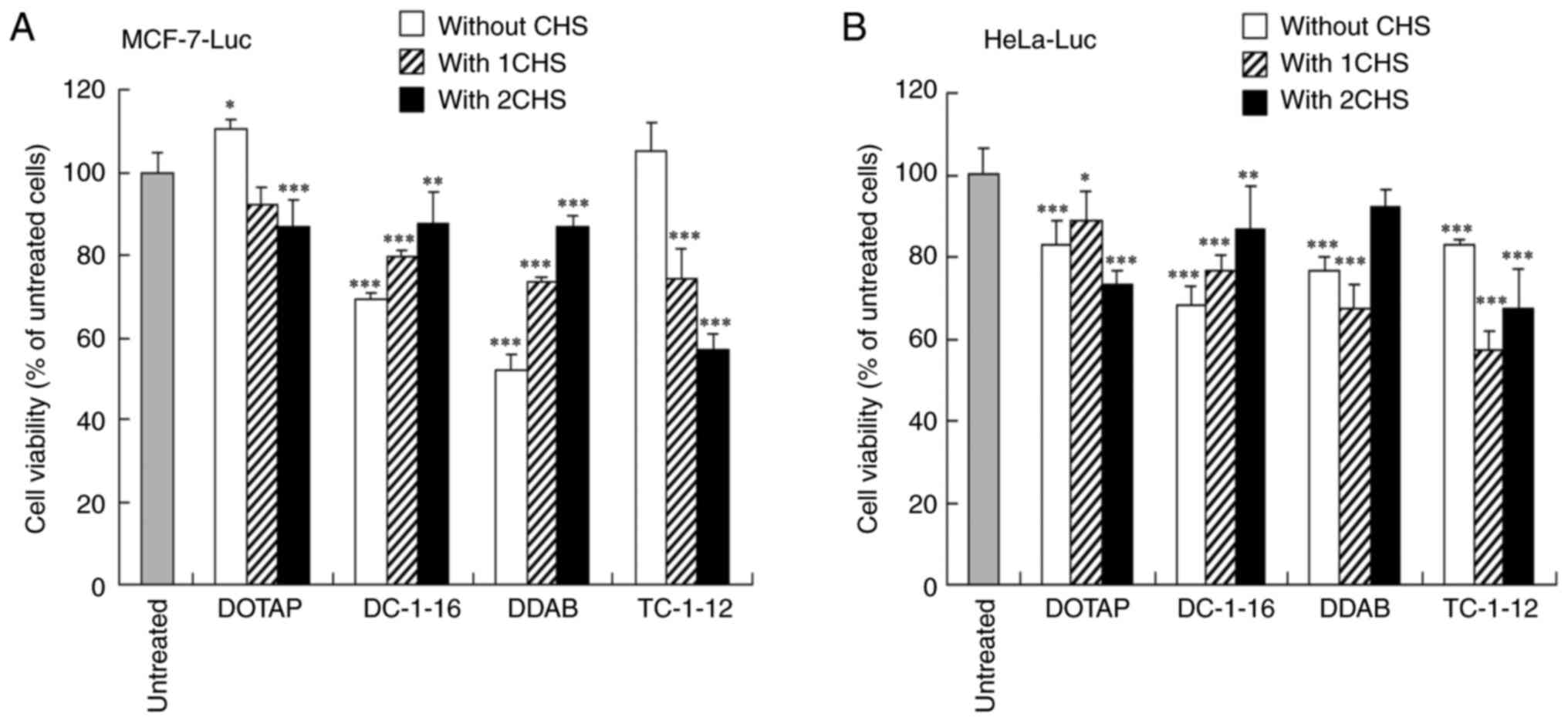

Cytotoxicity of cationic and anionic

siRNA lipoplexes

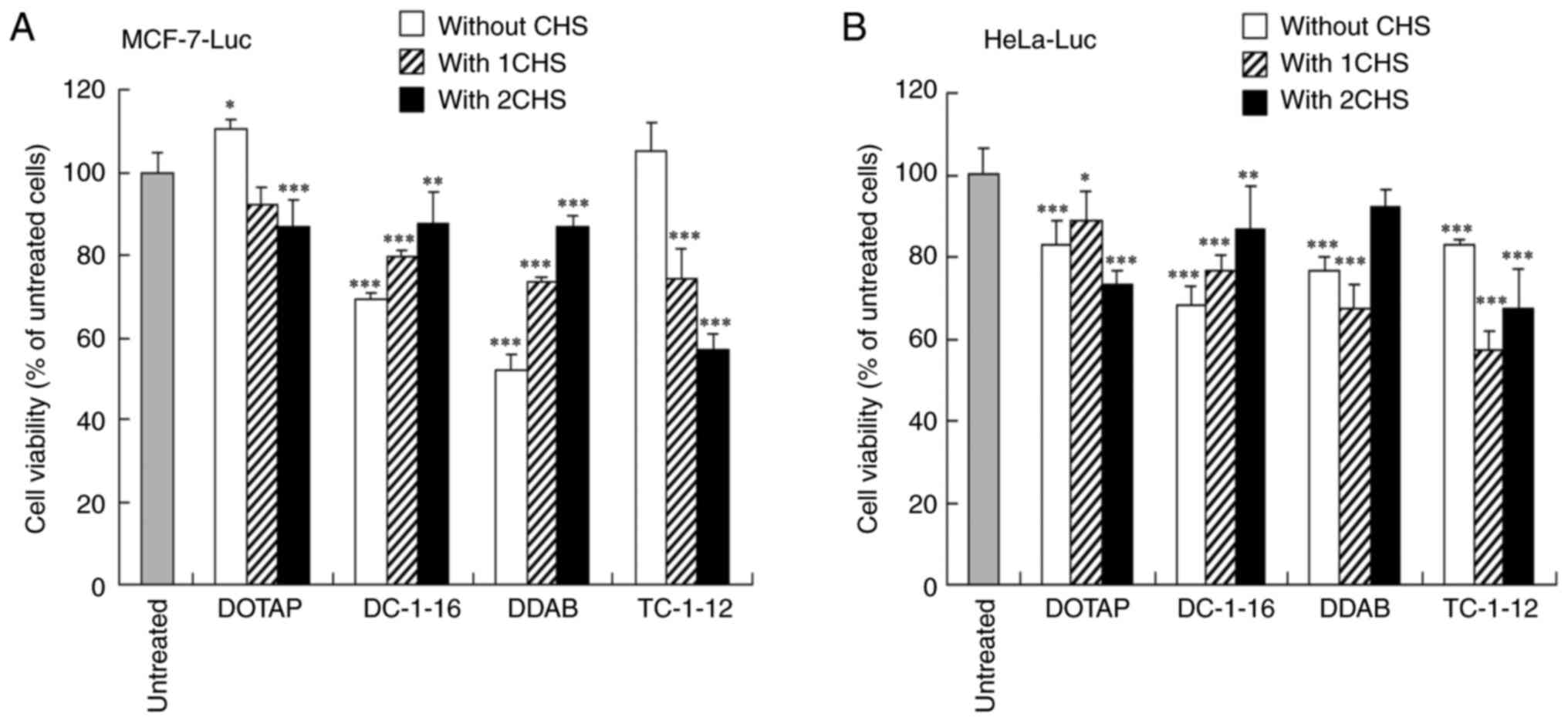

Cationic and anionic siRNA lipoplexes were

transfected into MCF-7-Luc and HeLa-Luc cells, with viability

measured after 48 h. Cytotoxicity of DOTAP and TC-1-12 formulations

increased in both cell types with more CHS added to LP-DOTAP and

LP-TC-1-12 lipoplexes, respectively (Fig. 4A and B). Conversely, the cytotoxicity of DC-1-16

and DDAB formulations decreased with increased CHS added to

LP-DC116 and LP-DDAB lipoplexes, respectively.

| Figure 4Cell viability after transfection

with cationic and anionic siRNA lipoplexes. Cationic and anionic

lipoplexes containing Cont siRNA were prepared by the modified

ethanol injection method and subsequently added to (A) MCF-7-Luc

and (B) HeLa-Luc cells at a final siRNA concentration of 50 nM.

Cell viability was assessed 48 h after transfection. Data are

represented as the mean + standard deviation (n=5).

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. untreated cells. Luc, luciferase;

siRNA, small interfering RNA; Cont, control; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N, N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; CHS, cholesteryl hemisuccinate. |

When anionic siRNA lipoplexes with 2CHS were

transfected into the cells, the culture medium contained 7.8 µg/ml

of CHS. To examine the cytotoxicity of CHS, CHS was added into

MCF-7-Luc and HeLa-Luc cells. CHS was found to be more toxic to

MCF-7-Luc cells than to HeLa-Luc cells (Fig. S1A). Furthermore, when cationic and

anionic liposomes without siRNA were added into both cell lines,

LP-TC112-2CHS increased cytotoxicity in MCF-7-Luc cells compared to

LP-TC112 (Fig. S1B, C).

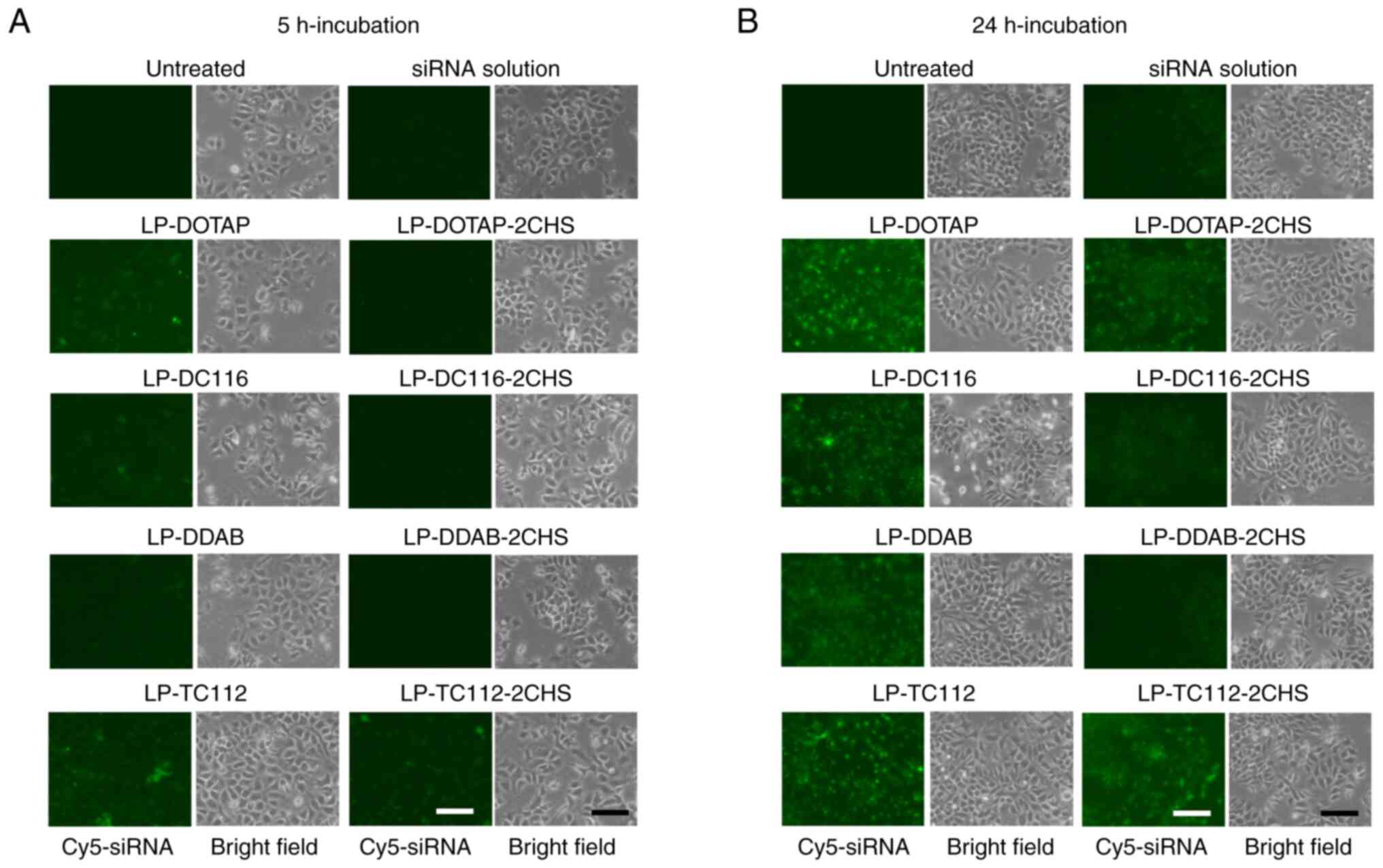

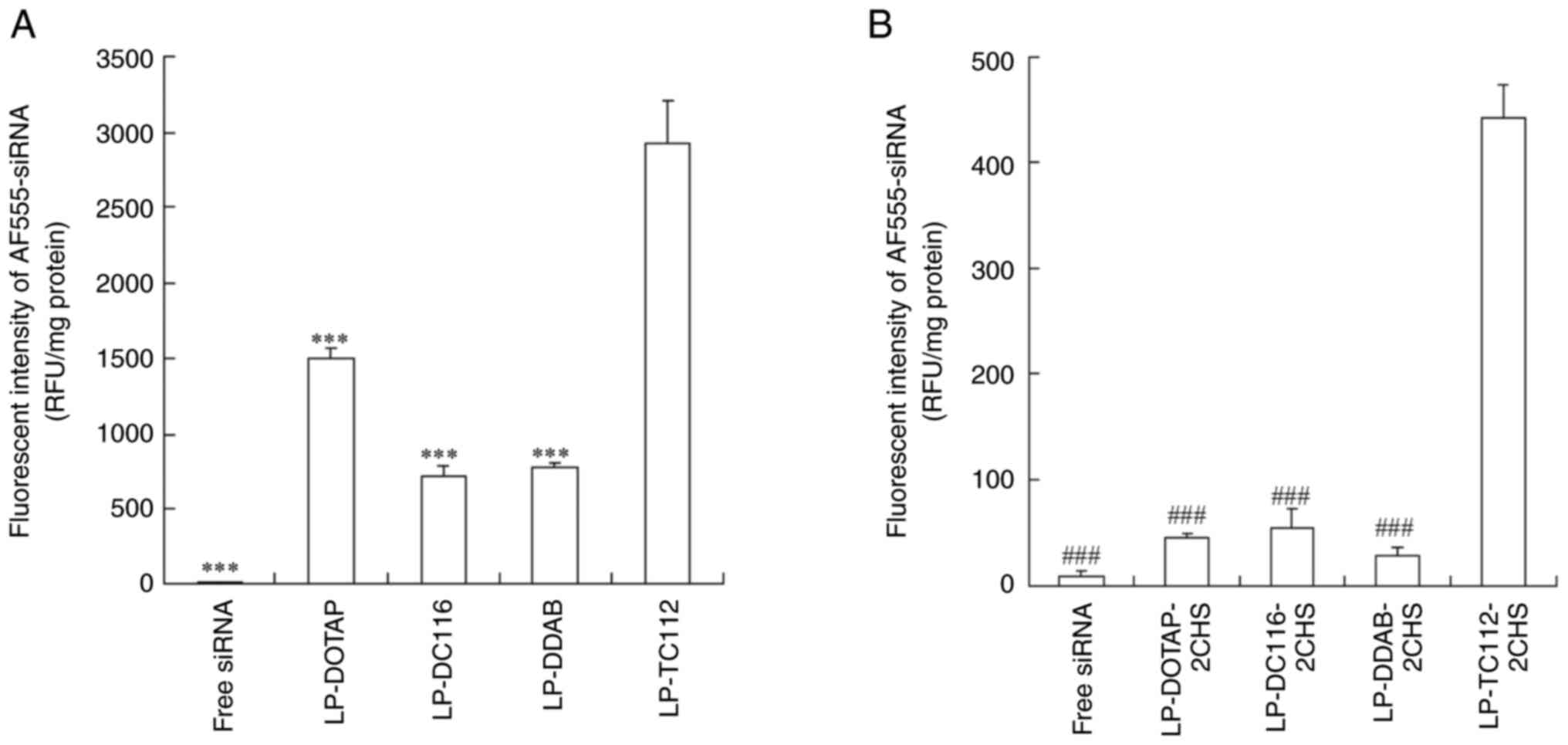

siRNA cellular uptake after

transfection with cationic and anionic lipoplexes

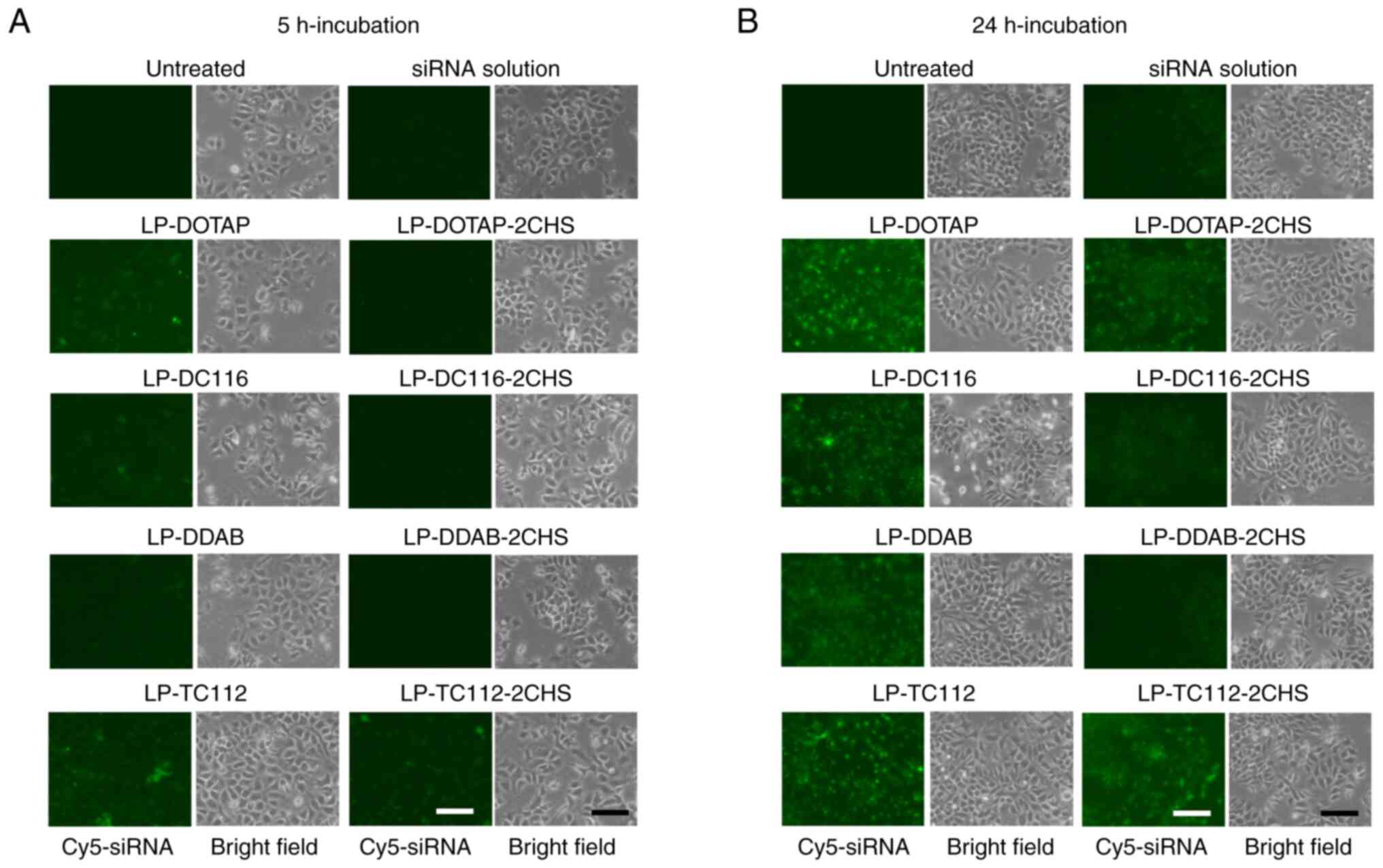

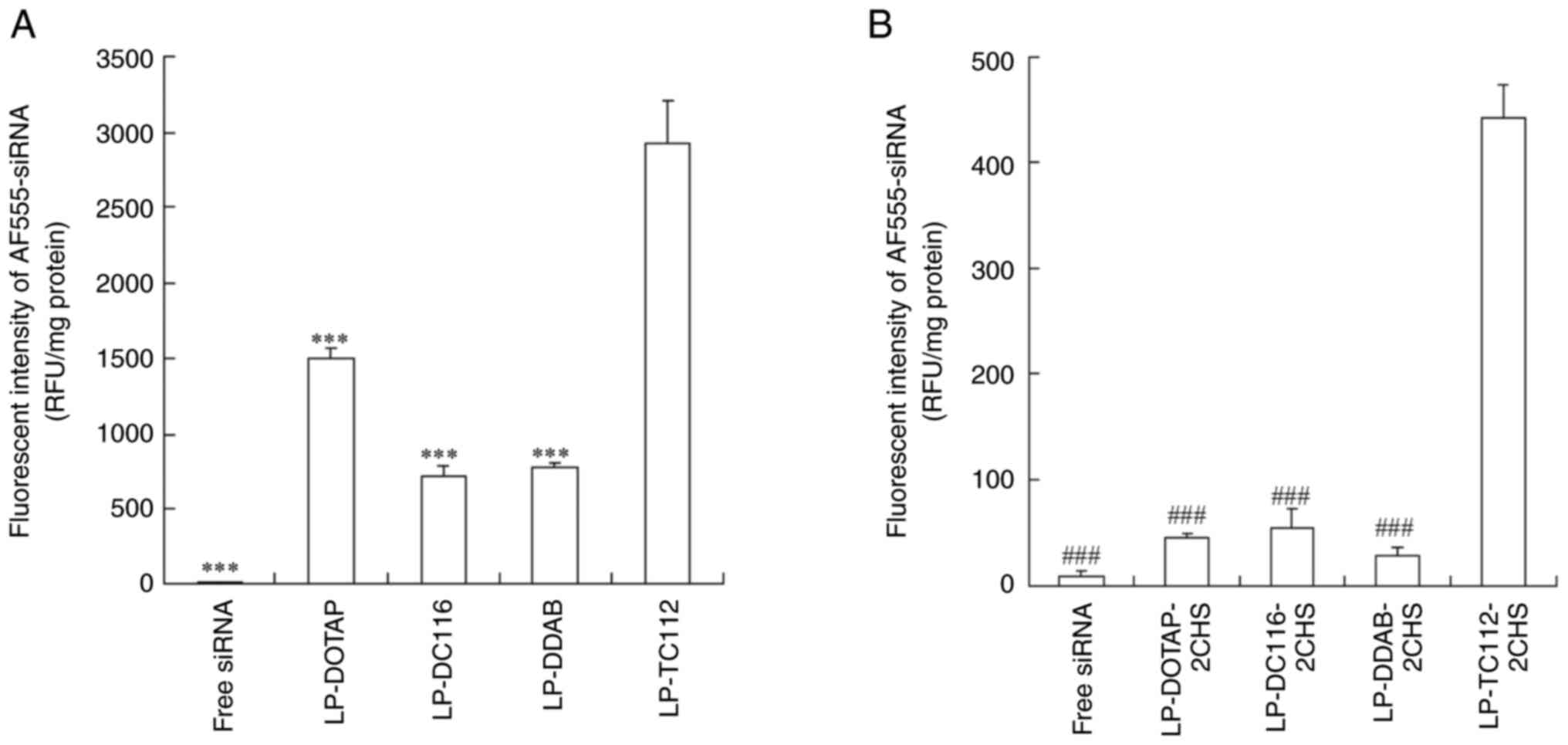

siRNA uptake in MCF-7-Luc cells was examined 5 or 24

h post-transfection with cationic and anionic lipoplexes. Among the

cationic lipoplexes, LP-TC112 lipoplexes exhibited the highest

siRNA uptake, showing approximately twofold higher uptake than

LP-DOTAP lipoplexes and fourfold higher uptake than both LP-DDAB

and LP-DC116 lipoplexes (Figs. 5A,

B, 6A). In contrast, all anionic lipoplexes

showed reduced siRNA uptake compared to their cationic counterparts

(Fig. 5A, B). However, LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes

exhibited higher siRNA uptake compared to the other anionic

lipoplexes (Figs. 6B, S2).

| Figure 5Cellular uptake of siRNA by MCF-7-Luc

cells after transfection with cationic and anionic lipoplexes.

Cationic and anionic lipoplexes containing Cy5-siRNA were prepared

using the modified ethanol injection method and added to MCF-7-Luc

cells at a final siRNA concentration of 50 nM. As a control,

Cy5-siRNA solution was added to the MCF-7-Luc cells. Localization

of Cy5-siRNA (green) was observed at (A) 5 and (B) 24 h

post-incubation, respectively. Scale bar, 100 µm. siRNA, small

interfering RNA; Luc, luciferase; LP, liposome; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N, N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; CHS, cholesteryl hemisuccinate. |

| Figure 6Cellular uptake of siRNA by MCF-7-Luc

cells after transfection with cationic and anionic lipoplexes. (A)

Cationic and (B) anionic lipoplexes containing AF555-siRNA were

prepared using the modified ethanol injection method and added to

MCF-7-Luc cells at a final siRNA concentration of 50 nM. As a

control, AF555-siRNA solution (free siRNA) was added to the

MCF-7-Luc cells. After 24 h, the cells were lysed, and the amount

of AF555-siRNA within the cells was measured using a fluorescence

plate reader. Data are represented as the mean + standard deviation

(n=3). ***P<0.001 vs. LP-TC112;

###P<0.001 vs. LP-TC112-2CHS. LP, liposome; siRNA,

small interfering RNA; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N, N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; CHS, cholesteryl hemisuccinate. |

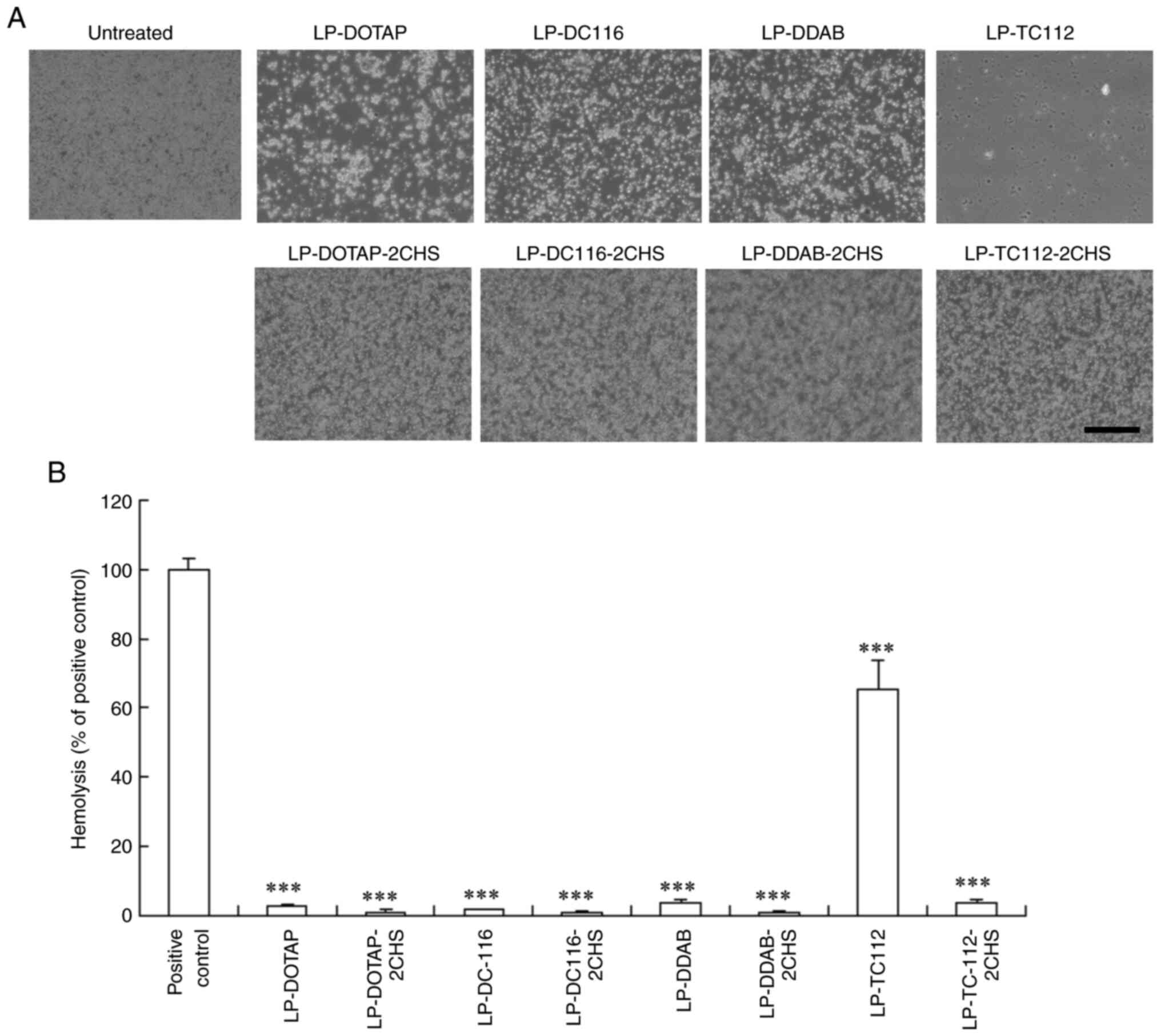

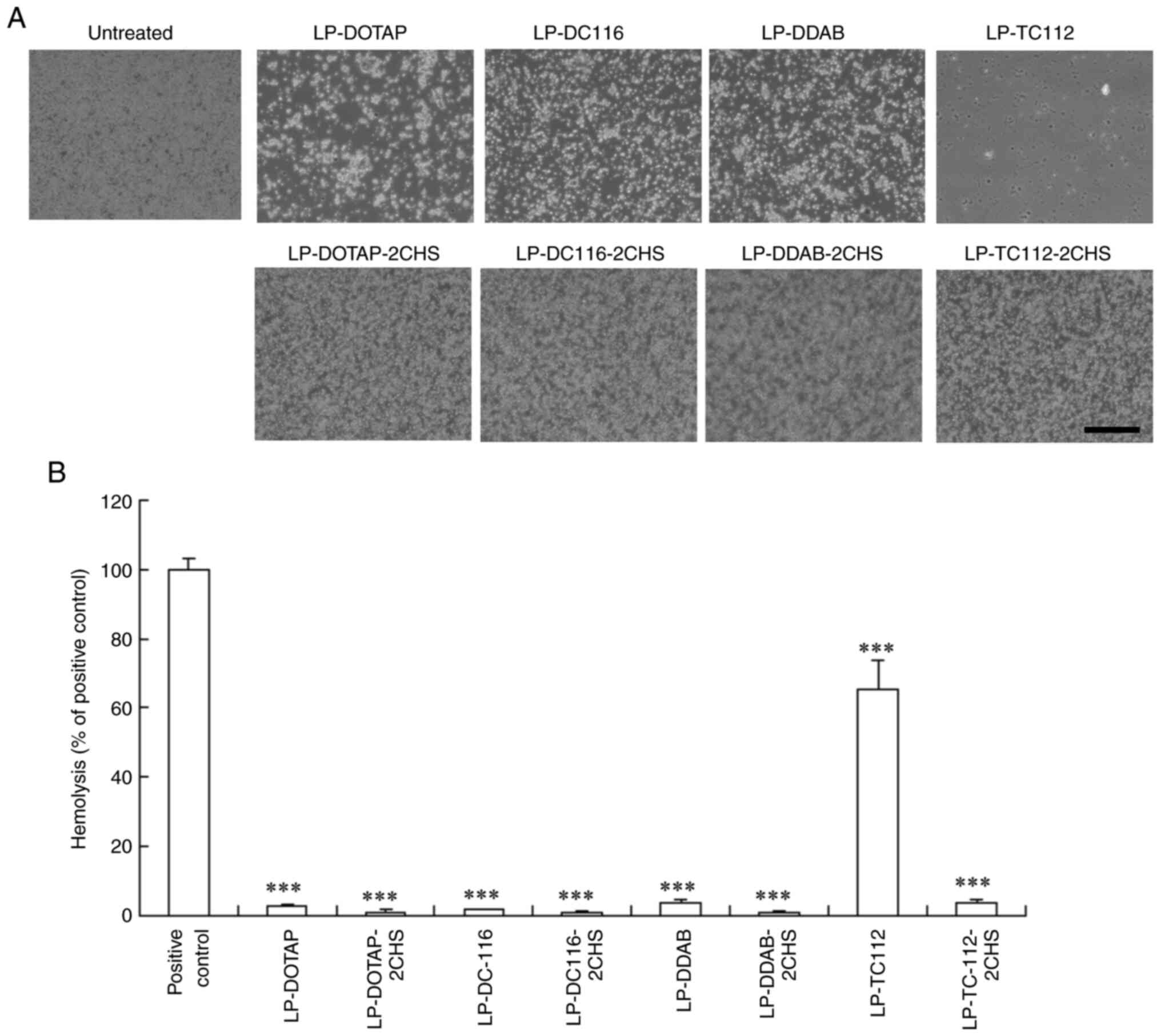

Hemolysis and erythrocyte aggregation

by cationic and anionic lipoplexes

Considering that positively charged lipoplexes can

disrupt erythrocytes through electrostatic interactions, hemolysis

and aggregation of mouse erythrocytes were investigated following

incubation with cationic and anionic siRNA lipoplexes. LP-DOTAP,

LP-DC116, and LP-DDAB lipoplexes caused marked erythrocyte

aggregation (Fig. 7A) but minimal

hemolysis (<5%; Fig. 7B).

Notably, LP-TC112 lipoplexes induced high levels of hemolysis

(65%). In contrast, LP-DOTAP-2CHS, LP-DC116-2CHS, LP-DDAB-2CHS, and

LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes did not cause erythrocyte aggregation or

hemolysis (<5%).

| Figure 7Hemolysis and erythrocyte

agglutination induced by cationic and anionic siRNA lipoplexes.

Cationic and anionic lipoplexes containing 50 pmol of Cont siRNA

were prepared using the modified ethanol injection method and

incubated with erythrocyte suspensions at 37˚C for 15 min. (A)

Erythrocyte agglutination after mixing with the siRNA lipoplexes.

Scale bar, 200 µm. (B) Hemolysis (%) calculated relative to the

absorbance of the hypotonic solution and presented as the mean +

standard deviation (n=3). Erythrocytes suspended in a hypotonic

solution (water) serve as a positive control for 100% hemolysis.

***P<0.001 vs. positive control. LP, liposome; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N, N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; CHS, cholesteryl hemisuccinate. |

Discussion

This study presents a two-step MEI method to prepare

anionic siRNA lipoplexes. CHS served as the anionic lipid to

neutralize the positive charge of siRNA lipoplexes. Adding a

lipid-ethanol solution of CHS and DOPE to the cationic siRNA

lipoplex suspensions reversed the surface potential from positive

to negative. It is hypothesized that either CHS and DOPE directly

integrate into the lipid membrane of the cationic siRNA lipoplexes,

forming anionic siRNA lipoplexes, or pre-formed CHS/DOPE anionic

liposomes bind and fuse electrostatically with cationic lipoplexes

to yield anionic siRNA lipoplexes.

Neutral charged siRNA lipoplexes (LP-DOTAP-1CHS,

LP-DC116-1CHS, and LP-DDAB-1CHS) were larger than their negatively

charged counterparts (LP-DOTAP-2CHS, LP-DC116-2CHS, and

LP-DDAB-2CHS), likely due to reduced electrostatic repulsion in the

neutral charged lipoplexes. At a cationic lipid to CHS ratio of

1:2, all siRNA lipoplexes exhibited strong negative ζ-potentials

(-16 to -27 mV), regardless of the cationic lipid used, indicating

that twice the molar ratio of CHS relative to the cationic lipid is

required to form anionic siRNA lipoplexes.

LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes with Luc siRNA achieved

strong gene silencing in both MCF-7-Luc and HeLa-Luc cells, whereas

LP-DOTAP-2CHS lipoplexes had a moderate effect. LP-DC116-2CHS and

LP-DDAB-2CHS lipoplexes were less effective. However, LP-TC112-2CHS

lipoplexes exhibited increased cytotoxicity in MCF-7-Luc cells. CHS

is an amphipathic cholesterol ester with anticancer activity

against MCF-7 cells (23). It was

found that CHS was more toxic to MCF-7-Luc cells than to HeLa-Luc

cells. In addition, LP-TC112-2CHS without siRNA also exhibited

higher cytotoxicity than LP-TC112 without siRNA in MCF-7-Luc cells.

These suggest that the LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes were efficiently

delivered into MCF-7 cells, and the CHS might induce

cytotoxicity.

All anionic lipoplexes reduced siRNA uptake in

MCF-7-Luc cells compared to their cationic counterparts, indicated

that the negative charge on the surface of the lipoplexes may have

weakened their interaction with cells. However, intracellular siRNA

was detected at high levels following transfection with

LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes, indicating better cellular uptake and

gene silencing. The reduced gene-silencing efficacy of

LP-DOTAP-2CHS, LP-DC116-2CHS and LP-DDAB-2CHS lipoplexes is likely

due to poor cellular uptake. However, the precise mechanisms

underlying the differential internalization of these lipoplexes

remain unclear. In our study, siRNA uptake after transfection with

cationic lipoplexes was highest in the order of LP-TC112

>LP-DOTAP >LP-DDAB=LP-DC116 lipoplexes. It has been reported

that the linker structure of a cationic lipid significantly impacts

the cellular uptake of lipoplexes, thereby affecting transfection

efficiency (24,25). TC-1-12 and DOTAP have a

biodegradable ester linker, while DDAB and DC-1-16 have a

non-biodegradable linker. This suggests that the difference in

linker structure may affect the interaction between the cell

membrane and the siRNA lipoplexes. In addition, TC-1-12, a lipid

with trialkyl chains, exhibits high cell membrane fusion activity

(20). Koulov et al. reported that

vesicles with cationic trialkyl chains promote greater membrane

fusion than those with structurally analogous cationic dialkyl or

monoalkyl chains (26). Therefore,

LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes may enhance cellular uptake and gene

silencing due to their strong membrane fusion activity, even though

they have a negative charge. Future studies should assess how

different cationic lipids used in anionic siRNA lipoplexes impact

cellular uptake.

LP-DOTAP, LP-DC116, and LP-DDAB lipoplexes caused

erythrocyte agglutination without hemolysis, while LP-TC112

lipoplexes exhibited strong hemolytic activity due to their

fusogenic properties. However, adding 2CHS prevented agglutination

after incubation with LP-DOTAP-2CHS, LP-DC116-2CHS, or LP-DDAB-2CHS

lipoplexes, whereas LP-TC112-2CHS lipoplexes did not cause

agglutination or hemolysis. Notably, LP-TC112-2CHS maintained high

cellular uptake and gene-silencing efficiency while suppressing

erythrocyte interaction. Positively charged siRNA lipoplexes

interact with erythrocytes and form agglutination in the

bloodstream, leading to their entrapment in highly vascularized

lung capillaries. However, negatively charged lipoplexes may reduce

siRNA accumulation in the lungs by avoiding interaction with

erythrocytes in the bloodstream, resulting in improved blood

stability. Further research is warranted to assess its

biodistribution and in vivo gene-silencing effects.

Erythrocytes from female mice were utilized in this study.

Nonetheless, male erythrocytes are reportedly more susceptible to

hemolysis than female ones (21),

suggesting that differences in hemolytic potential across species

should be considered carefully.

Previous studies have described the preparation of

cationic

3β-[N-(N',N'-dimethylaminoethyl)carbamoyl]

cholesterol (DC-Chol)/DOPE and anionic CHS/DOPE liposomes

separately via thin-film hydration, followed by neutralizing

positively charged DC-Chol/DOPE-plasmid DNA lipoplexes through

incubation with CHS/DOPE liposomes (27). However, this requires specialized

equipment, including evaporators, sonicators, and extruders. In the

current study, a simple two-step MEI method was developed for

preparing anionic siRNA lipoplexes without the need for evaporation

or sonication. Overall, the results suggest that TC-1-12-based

anionic siRNA lipoplexes prepared using lipid-ethanol solutions may

be suitable for siRNA transfection.

Supplementary Material

Effect of CHS on cell viability. (A)

MCF-7-Luc and HeLa-Luc cells were treated with CHS at

concentrations ranging from 1.56 to 50 μg/ml. Cell viability

was assessed 48 h after treatment. Data are represented as the mean

+ standard deviation (n=3). ***P<0.001 vs. untreated

cells. Cationic and anionic liposomes without siRNA were prepared

by the modified ethanol injection method and subsequently added to

(B) MCF-7-Luc and (C) HeLa-Luc cells. Cell viability was assessed

48 h after transfection. Data are represented as the mean +

standard deviation (n=5 for B; n=4 for C). **P<0.01

and ***P<0.001 vs. untreated cells. CHS, cholesteryl

hemisuccinate; Luc, luciferase; LP, liposome; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N, N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-

N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; CHS, cholesteryl hemisuccinate.

siRNA localization after transfection

with anionic lipoplexes. Anionic lipoplexes with Cy5-siRNA were

prepared using the modified ethanol injection method and added to

MCF-7-Luc cells at a final siRNA concentration of 50 nM. As a

control, Cy5-siRNA solution was added to the MCF-7-Luc cells. The

cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 to label the cell nuclei 24 h

after incubation. Localizations of Cy5-siRNA (green) and nuclei

(blue) were observed by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar, 100

μm. LP, liposome; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N, N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; TC-1-12, 11-((1,3-bis

(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl)propan-2-yl)amino)-

N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; CHS, cholesteryl hemisuccinate.

Size and ζ-potential of cationic and

anionic liposomes prepared using modified ethanol injection

method.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Mina Kameishi and Mr. Keita

Kariya (Department of Molecular Pharmaceutics, Hoshi University,

Tokyo, Japan) for their assistance with the siRNA transfection

experiments.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YH conceptualized the study, developed the

methodology, conducted the investigation, curated the data,

performed the formal analysis, prepared the original draft, and

wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. AK and MS conducted the

study. YH and AK confirmed the authenticity of the raw data. All

the authors have read and approved the final version of this

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal

Care and Use Committee of Hoshi University (approval no.

P24-151).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kim DH, Behlke MA, Rose SD, Chang MS, Choi

S and Rossi JJ: Synthetic dsRNA Dicer substrates enhance RNAi

potency and efficacy. Nat Biotechnol. 23:222–226. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kubowicz P, Żelaszczyk D and Pękala E:

RNAi in clinical studies. Curr Med Chem. 20:1801–1816.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Xue HY, Guo P, Wen WC and Wong HL:

Lipid-based nanocarriers for RNA delivery. Curr Pharm Des.

21:3140–3147. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhang S, Zhi D and Huang L: Lipid-based

vectors for siRNA delivery. J Drug Target. 20:724–735.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hattori Y, Tamaki K, Sakasai S, Ozaki KI

and Onishi H: Effects of PEG anchors in pegylated siRNA lipoplexes

on in vitro gene-silencing effects and siRNA biodistribution in

mice. Mol Med Rep. 22:4183–4196. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hattori Y, Tamaki K, Ozaki KI, Kawano K

and Onishi H: Optimized combination of cationic lipids and neutral

helper lipids in cationic liposomes for siRNA delivery into the

lung by intravenous injection of siRNA lipoplexes. J Drug Deliv Sci

Technol. 52:1042–1050. 2019.

|

|

7

|

Lechanteur A, Furst T, Evrard B, Delvenne

P, Hubert P and Piel G: PEGylation of lipoplexes: The right balance

between cytotoxicity and siRNA effectiveness. Eur J Pharm Sci.

93:493–503. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hatakeyama H, Akita H and Harashima H: The

polyethyleneglycol dilemma: Advantage and disadvantage of

PEGylation of liposomes for systemic genes and nucleic acids

delivery to tumors. Biol Pharm Bull. 36:892–899. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Fang Y, Xue J, Gao S, Lu A, Yang D, Jiang

H, He Y and Shi K: Cleavable PEGylation: A strategy for overcoming

the ‘PEG dilemma’ in efficient drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 24

(Supp1):S22–S32. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kapoor M and Burgess DJ: Physicochemical

characterization of anionic lipid-based ternary siRNA complexes.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1818:1603–1612. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Han X, Lu Y, Xu Z, Chu Y, Ma X, Wu H, Zou

B and Zhou G: Anionic liposomes prepared without organic solvents

for effective siRNA delivery. IET Nanobiotechnol. 17:269–280.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Hattori Y, Nakamura A, Arai S, Nishigaki

M, Ohkura H, Kawano K, Maitani Y and Yonemochi E: In vivo siRNA

delivery system for targeting to the liver by poly-l-glutamic

acid-coated lipoplex. Results Pharm Sci. 4:1–7. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ribeiro MCS, de Miranda MC, Cunha PDS,

Andrade GF, Fulgêncio GO, Gomes DA, Fialho SL, Pittella F,

Charrueau C, Escriou V and Silva-Cunha A: Neuroprotective effect of

siRNA entrapped in hyaluronic acid-coated lipoplexes by

intravitreal administration. Pharmaceutics. 13(845)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Maeki M, Okada Y, Uno S, Niwa A, Ishida A,

Tani H and Tokeshi M: Production of siRNA-loaded lipid

nanoparticles using a microfluidic device. J Vis Exp.

22(181)2022.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Maeki M, Uno S, Niwa A, Okada Y and

Tokeshi M: Microfluidic technologies and devices for lipid

nanoparticle-based RNA delivery. J Control Release. 344:80–96.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hattori Y, Saito H, Nakamura K, Yamanaka

A, Tang M and Ozaki KI: In vitro and in vivo transfections using

siRNA lipoplexes prepared by mixing siRNAs with a lipid-ethanol

solution. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 75(103635)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Hattori Y, Tang M, Suzuki H, Hattori A,

Endo S, Ishii A, Aoki A, Ezaki M and Sakai H: Optimization of

transfection into cultured cells with siRNA lipoplexes prepared

using a modified ethanol injection method. J Drug Deliv Sci

Technol. 99(106000)2024.

|

|

18

|

Hattori Y, Tang M, Aoki A, Ezaki M, Sakai

H and Ozaki KI: Effect of the combination of cationic lipid and

phospholipid on gene-knockdown using siRNA lipoplexes in breast

tumor cells and mouse lungs. Mol Med Rep. 28(180)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hattori Y, Kikuchi T, Ozaki KI and Onishi

H: Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo therapeutic antitumor

efficacy of transduction of polo-like kinase 1 and heat shock

transcription factor 1 small interfering RNA. Exp Ther Med.

14:4300–4306. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Hattori Y and Shimizu R: Effective mRNA

transfection of tumor cells using cationic triacyl lipid-based mRNA

lipoplexes. Biomed Rep. 22(25)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Alshalani A, AlSudais H, Binhassan S and

Juffermans NP: Sex discrepancies in blood donation: Implications

for red blood cell characteristics and transfusion efficacy.

Transfus Apher Sci. 63(104016)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hattori Y, Shinkawa M, Kurihara A and

Shimizu R: Optimization of PEGylation for cationic triacyl

lipid-based siRNA lipoplexes prepared using the modified ethanol

injection method for tumor therapy. J Liposome Res. 35:300–311.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Djuric Z, Heilbrun LK, Lababidi S,

Everett-Bauer CK and Fariss MW: Growth inhibition of MCF-7 and

MCF-10A human breast cells by alpha-tocopheryl hemisuccinate,

cholesteryl hemisuccinate and their ether analogs. Cancer Lett.

111:133–139. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Rajesh M, Sen J, Srujan M, Mukherjee K,

Sreedhar B and Chaudhuri A: Dramatic influence of the orientation

of linker between hydrophilic and hydrophobic lipid moiety in

liposomal gene delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 129:11408–11420.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hattori Y, Hagiwara A, Ding W and Maitani

Y: NaCl improves siRNA delivery mediated by nanoparticles of

hydroxyethylated cationic cholesterol with amido-linker. Bioorg Med

Chem Lett. 18:5228–5232. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Koulov AV, Vares L, Jain M and Smith BD:

Cationic triple-chain amphiphiles facilitate vesicle fusion

compared to double-chain or single-chain analogues. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1564:459–465. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chen Y, Sun J, Lu Y, Tao C, Huang J, Zhang

H, Yu Y, Zou H, Gao J and Zhong Y: Complexes containing cationic

and anionic pH-sensitive liposomes: Comparative study of factors

influencing plasmid DNA gene delivery to tumors. Int J

Nanomedicine. 8:1573–1593. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|