Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive

neurodegenerative disorder that is predominantly characterized by

senile plaques (SP), neurofibrillary tangles and regional neuronal

loss (1,2). The primary component of SP is β-amyloid

(Aβ), which has previously been demonstrated to damage synaptic

structures and induce neuronal cell death (1–4). In

addition, oxidative stress and ageing promote Aβ production, which

has been associated with the occurrence of AD (5). The p66shc adaptor protein is important

for the regulation of cellular senescence and oxidative stress

(6–12); under oxidative stress, the brain is

more susceptible to damage, as compared with other tissues and

organs. In the early stages of AD, oxidative stress occurs prior to

the appearance of pathological characteristics, and accelerates

neurodegeneration and Aβ formation; thus suggesting that oxidative

stress may be involved in the neuropathological process of AD

(1–6).

Anisomycin is an antibiotic produced by

Streptomyces griseolus, which is capable of binding to the

60S ribosomal subunit and blocking polypeptide chain elongation,

thereby inhibiting protein synthesis (13–17). As

a result, anisomycin exhibits some degree of toxicity towards all

cells, including inducing inflammatory responses and oxidative

stress injuries that are associated with neuron oxidation and

ageing (13–17). As such, anisomycin-induced cell

damage may be used to explore the relationship between

p66shc-mediated oxidative stress responses and the development and

progression of AD. By treating SH-SY5Y cells with anisomycin, Guo

et al (13) demonstrated that

anisomycin was able to enhance the production of Aβ and increase

the expression of presenilin-1 and other ageing-associated

proteins.

Astragaloside IV, cinnamic acid, paeoniflorin, and

gallic acid are small-molecule compounds with antioxidant

properties (2). In the present

study, a cell model was established in which Aβ deposition was

induced via exposure of SH-SY5Y cells to anisomycin. Subsequently,

the cell model was used to verify whether downregulation of p66shc

expression via small molecule compounds was able to alleviate

anisomycin-induced damage to SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells obtained from

the Cell Bank of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences

(Shanghai, China) were cultured in a routine manner using

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5%

CO2. The culture medium was changed every 3 days. Upon

reaching confluence, the cells were trypsinized (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and passaged. Cells in the logarithmic

growth phase were selected for subsequent experiments.

Model construction

The SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 0, 1, 3, 6, 12,

25, 50 or 100 µmol/l anisomycin (Shanghai Yuanye Bio Co., Ltd.,

Shanghai, China) for 0, 12, 24 or 48 h. The anisomycin

concentration and treatment duration for optimizing SH-SY5Y cell

damage and Aβ deposition were selected for construction of the AD

model. The cells were trypsinized and seeded into cell culture

plates. Four replicate wells were set up for each group. Upon

reaching 70 to 80% confluence, the culture medium was discarded and

the cells were incubated with either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) or one of the various

concentrations of medium-diluted anisomycin. In addition, a control

group and blank control group were constructed: The control group

was treated with equal volumes of DMSO, and the blank control group

was cultured in equal volumes of medium for an additional 24 hours.

Cell morphology was observed under a microscope (DMI3000; Leica

Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). At specified times,

the cells were centrifuged (Allegra 64R; Beckman Coulter, Inc.,

Miami, FL, USA) at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 10°C, and the resulting

supernatant and cell pellets were collected for subsequent assays.

After examining relevant indices, an anisomycin concentration of 3

µmol/l was selected. Subsequently, cells were cultured for 0, 12,

24 and 48 h in the presence of anisomycin prior to being harvested

and centrifuged. The resulting supernatant and cell pellets were

collected for assays.

Screening of small molecule

compounds

The SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 500 µmol/l of

the small molecule compounds astragaloside IV, cinnamic acid,

paeoniflorin and gallic acid (all Shanghai Yuanye Bio Co., Ltd.).

Initially, SH-SY5Y cells cultured in petri dishes were subjected to

tryptic digestion, and subsequently harvested and seeded into cell

culture plates at a density of 1×104 cells/ml, after

which the cells were incubated with 3 µmol/l anisomycin for 48 h in

order to establish the AD model. Subsequently, the cells were

treated with 50 µmol/l small molecule compounds, which had been

diluted in culture medium. In addition, the control group

(DMSO-treated group) and blank control group (non-treated group)

were constructed. Neither the control group nor the blank control

group were treated with small molecule compounds, and the blank

control group did not receive anisomycin treatment; instead, an

equal volume of culture medium was added to the blank control

group, and the cells were cultured for another 24 h. Cell

morphology was observed under a phase contrast microscope (DMI3000;

Leica Microsystems, Inc.). At predetermined times, the cells were

centrifuged, and the resulting supernatant and cell pellets were

collected for future assays.

Real time-quantitative polymerase

chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

qPCR was conducted according to the method outlined

in previous studies (18,19). Briefly, the cell pellets were

collected following treatment, after which total RNA was extracted

from the cells grown in culture flasks using TRIzol® reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the concentration

(>10 µg/µl) and purity (OD260/280>1.80) of the

total RNA were determined. All RNA samples were stored at −80°C

prior to analysis. The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using

a Reverse Transcription kit (TOYOBO, Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan),

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting cDNA

was stored at −20°C. RT-qPCR was performed using a MasterCycler

RealPlex4 RT-qPCR detection system from Eppendorf (Hamburg,

Germany), with the SYBR-Green RealTime PCR Master mix (TOYOBO Co.,

Ltd.) as the detection dye. RT-qPCR amplification was performed

over 40 cycles, with denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec and annealing

at 58°C for 45 sec, and a final extension step at 72°C for 42 sec.

The target cDNA was quantified using the relative quantification

method. Briefly, a comparative quantification cycle (Cq) was used

to determine gene expression levels relative to the 18S ribosomal

RNA (rRNA), which served as an internal control. The steady state

mRNA levels were reported as an n-fold difference relative to the

internal control. For each sample, the Cq values of the marker

genes were normalized using the following equation: ΔCq =

Cq(genes)-Cq(18S rRNA). The relative expression levels were

determined using the equation: ΔΔCq = ΔCq(sample

groups)-ΔCt(control group). The values used to plot the relative

expression of markers were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq

values. The primers used were as follows: Forward

5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′, and reverse 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′

for 18S rRNA; and forward 5′-GTATGTGCTCACTGGCTTGC-3′, and reverse

5′-CTGACACTTTCAAAGCGGTG-3′ for p66.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed according to a method

outlined in previous studies (18,19).

Briefly, the SH-SY5Y cells were removed from culture flasks using

cell scrapers and lysed in precooled (4°C) cell lysis buffer

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). The protein

concentration (50 µg/µl) was measured using the bicinchoninic acid

assay. Total protein extract (15 µl) was separated by 12% sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred

onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica,

MA, USA). The membranes were then blocked with a solution

containing 10% calf serum, followed by four times washing for 15

min with Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBST;

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature.

Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with primary rabbit

anti-human p66 (1:1,000; ab87633; Abcam, Shanghai, China) and

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:1,000; 5174, Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) polyclonal antibodies

at 4°C overnight. Following extensive washing, the membranes were

incubated with secondary peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

immunoglobulin G antibodies (1:1,000; sc-2004; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) for 1 h. Following further

washing steps (15 min each) with TBST at room temperature, the

target proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL

kit; Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) and exposure to

Kodak Biomax XAR-5 films (Sigma-Aldrich).

Quantification of Aβ1–42 levels by

ELISA

The cell pellets were suspended in cell lysis buffer

and a double-antibody sandwich ELISA was performed, according to

the manufacturer's instructions (Human Aβ1–42 ELISA kit; cat no.

h022931; Westang Bio, Shanghai, China). The primary antibody

working solution, enzyme-labeled antibody working solution,

substrate working solution and stop solution, were added

sequentially to the cell lysates. The Aβ1–42 concentration was

calculated according to the absorbance values of a standard

curve.

Quantification of levels of superoxide

dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), and acetylcholine

(Ach)

The SH-SY5Y cells and their supernatants were

collected, and cell pellets were suspended in buffer solution

(phosphate-buffered saline or physiological saline; 0.3–0.5 ml per

106 cells). Cells were lysed in an ice bath using

sonication, in which the tip of an ultrasonic probe was immersed in

the liquid. Enzyme and substrate working solutions were then added

sequentially. The absorbance of various concentrations of the

standard compounds was determined. The SOD, MDA and Ach

concentrations were calculated by comparing the absorbance of the

samples to those of the standards. The SOD Assay kit, MDA Assay

kit, and Ach Assay kit were all purchased from Westang Bio

(Shanghai, China).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Differences were evaluated using the Student's t-test and GraphPad

Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for

statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Anisomycin increases the expression

levels of Aβ1–42 in SH-SY5Y cells

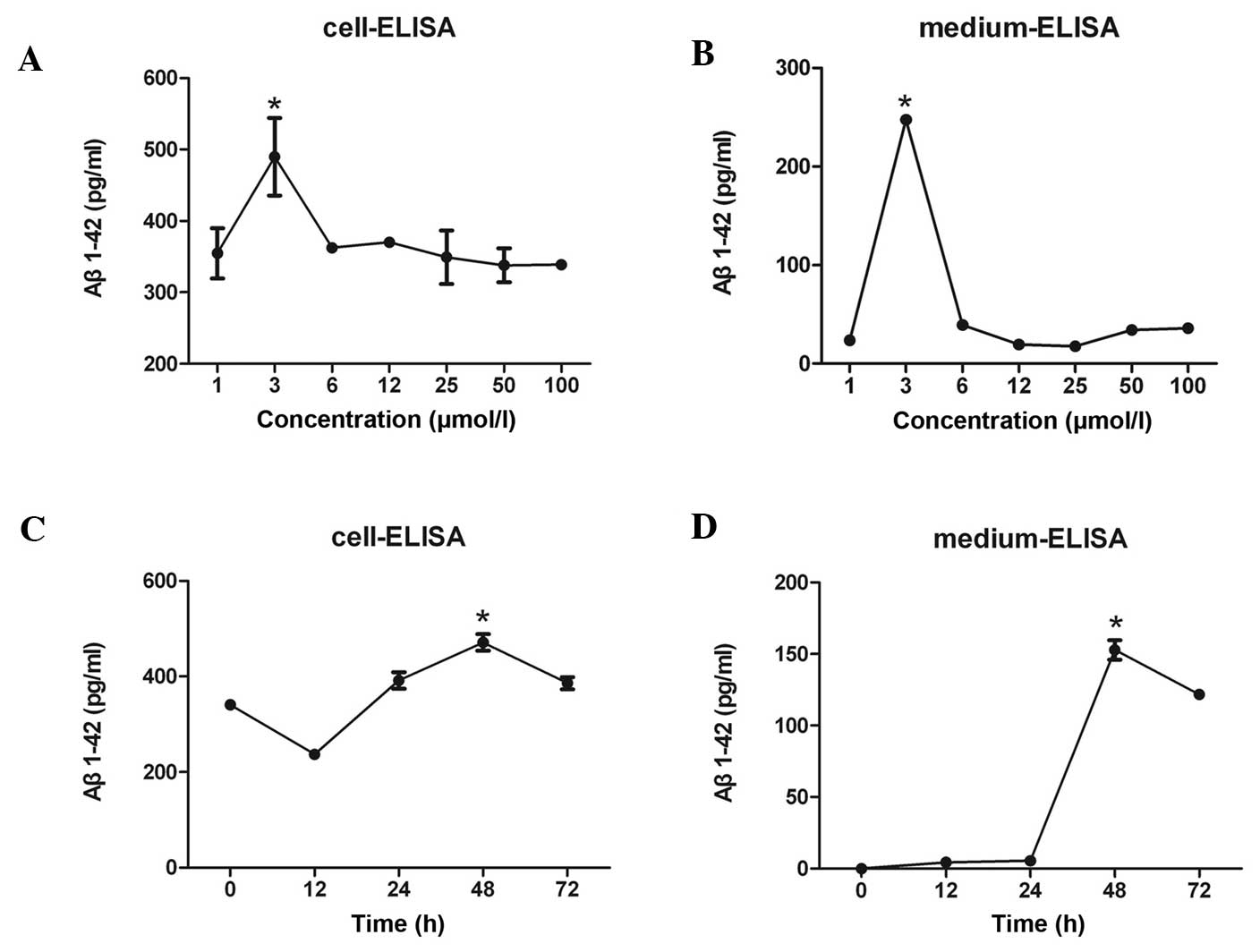

The levels of Aβ1–42 in the SH-SY5Y cell pellets and

culture supernatants were determined using an ELISA. The Aβ1–42

levels in the SH-SY5Y cells reached a maximum value following

treatment of the cells with 3 µmol/l anisomycin (Fig. 1A and B), and this occurred after 48 h

of stimulation (Fig. 1C and D).

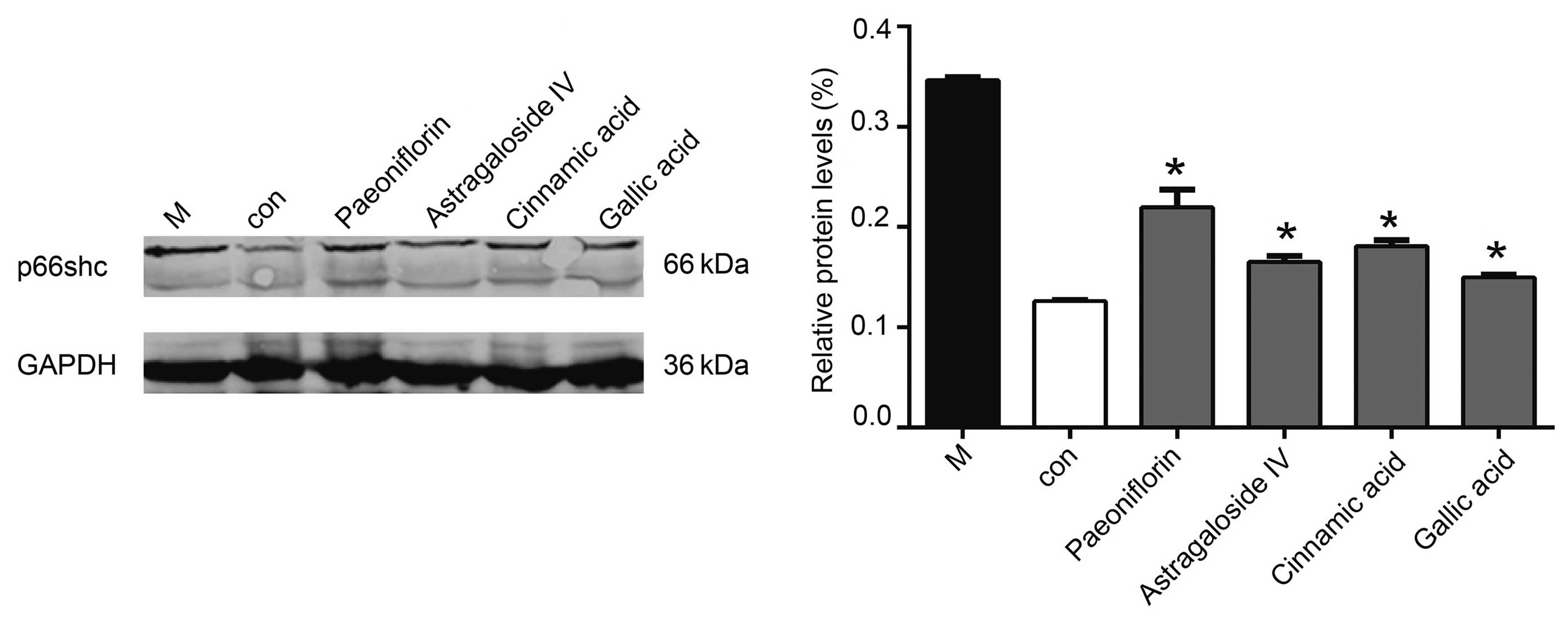

| Figure 1.(A) Various concentrations of Aβ1–42

were detected in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells following

treatment of the cells with 1, 3, 6, 12, 25, 50 or 100 µmol/l

anisomycin. Aβ1–42 levels in SH-SY5Y cells reached a maximum value

following treatment of the cells with 3 µmol/l anisomycin. (B)

Various concentrations of secreted Aβ1–42 were detected in the cell

culture medium following treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with 1, 3, 6,

12, 25, 50 or 100 µmol/l anisomycin. The level of secreted Aβ1–42

in cell culture supernatant reached a peak following treatment of

SH-SY5Y cells with 3 µmol/l anisomycin. (C) Treatment of SH-SY5Y

cells with 3 µmol/l anisomycin for 0, 12, 24, 48 or 72 h resulted

in various Aβ1–42 concentrations in the cells. The Aβ1–42

concentration in SH-SY5Y cells reached a maximum value following

stimulation with anisomycin for 48 h. (D) Stimulation of SH-SY5Y

cells with 3 µmol/l anisomycin for 0, 12, 24, 48 or 72 h resulted

in various levels of secreted Aβ1–42 into the cell culture

supernatant. The level of secreted Aβ1–42 in cell culture

supernatant reached a peak following 48 h of treatment with 3

µmol/l anisomycin. Data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation of triplicate experiments. *P<0.05 vs. 0 h. Aβ,

β-amyloid. |

Anisomycin increases the expression

levels of p66shc in SH-SY5Y cells

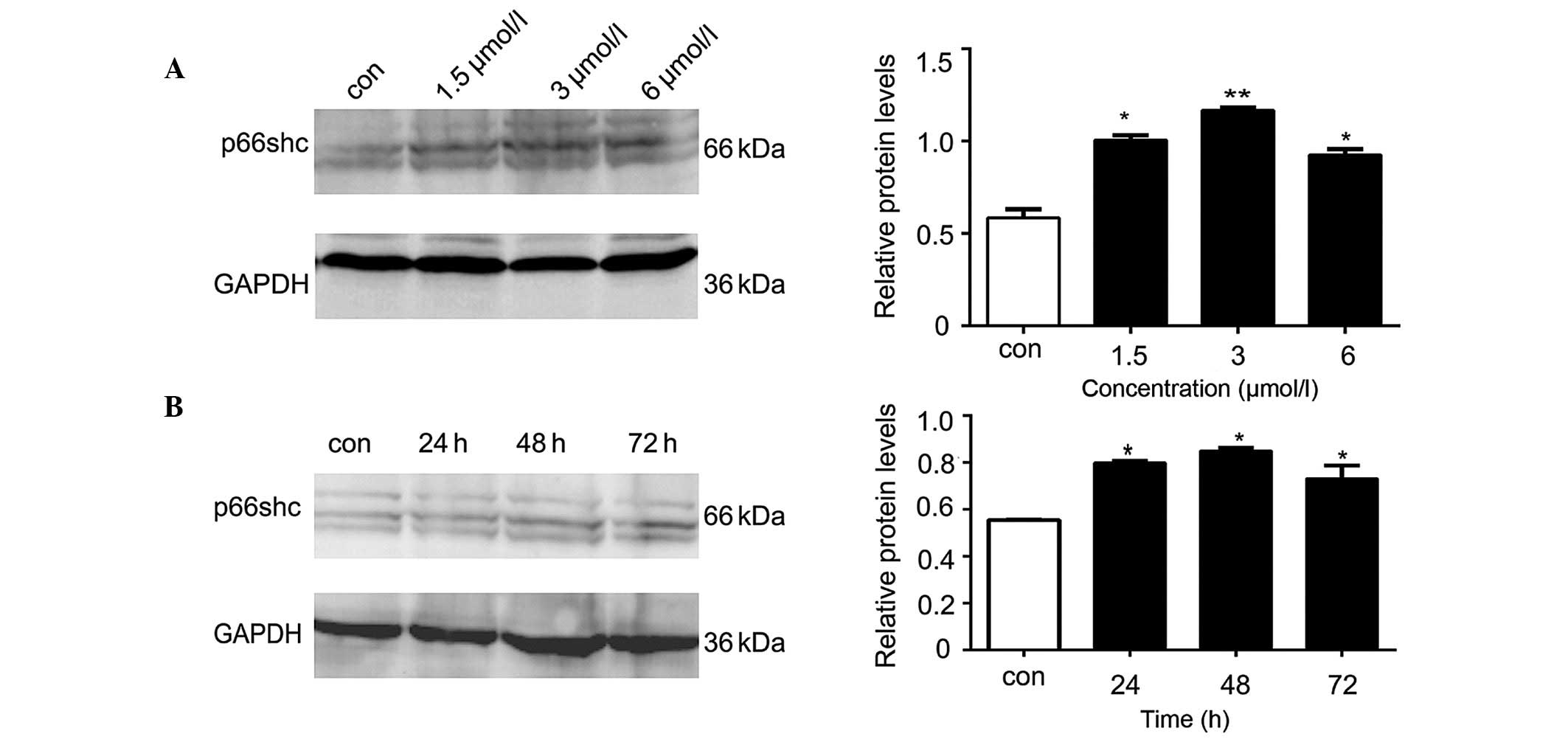

The western blot analysis demonstrated that the

protein expression levels of p66shc in the SH-SY5Y cells

significantly increased following treatment with various

concentrations of anisomycin (1.5, 3 or 6 µmol/l), as compared with

the control group (P<0.05; Fig.

2A). The increase in p66shc protein expression levels was most

significant when the cells were treated with 3 µmol/l anisomycin

(P<0.01; Fig. 2A). Compared with

the p66shc levels at 0 h, the protein expression levels of p66shc

were significantly increased at various time points (24, 48 and 72

h) following treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with 3 µmol/l anisomycin

(P<0.05; Fig. 2B). The p66shc

protein expression levels peaked after 48 h of treatment with 3

µmol/l anisomycin (P<0.01; Fig.

2B).

Anisomycin increases the mRNA

expression levels of p66shc in SH-SY5Y cells

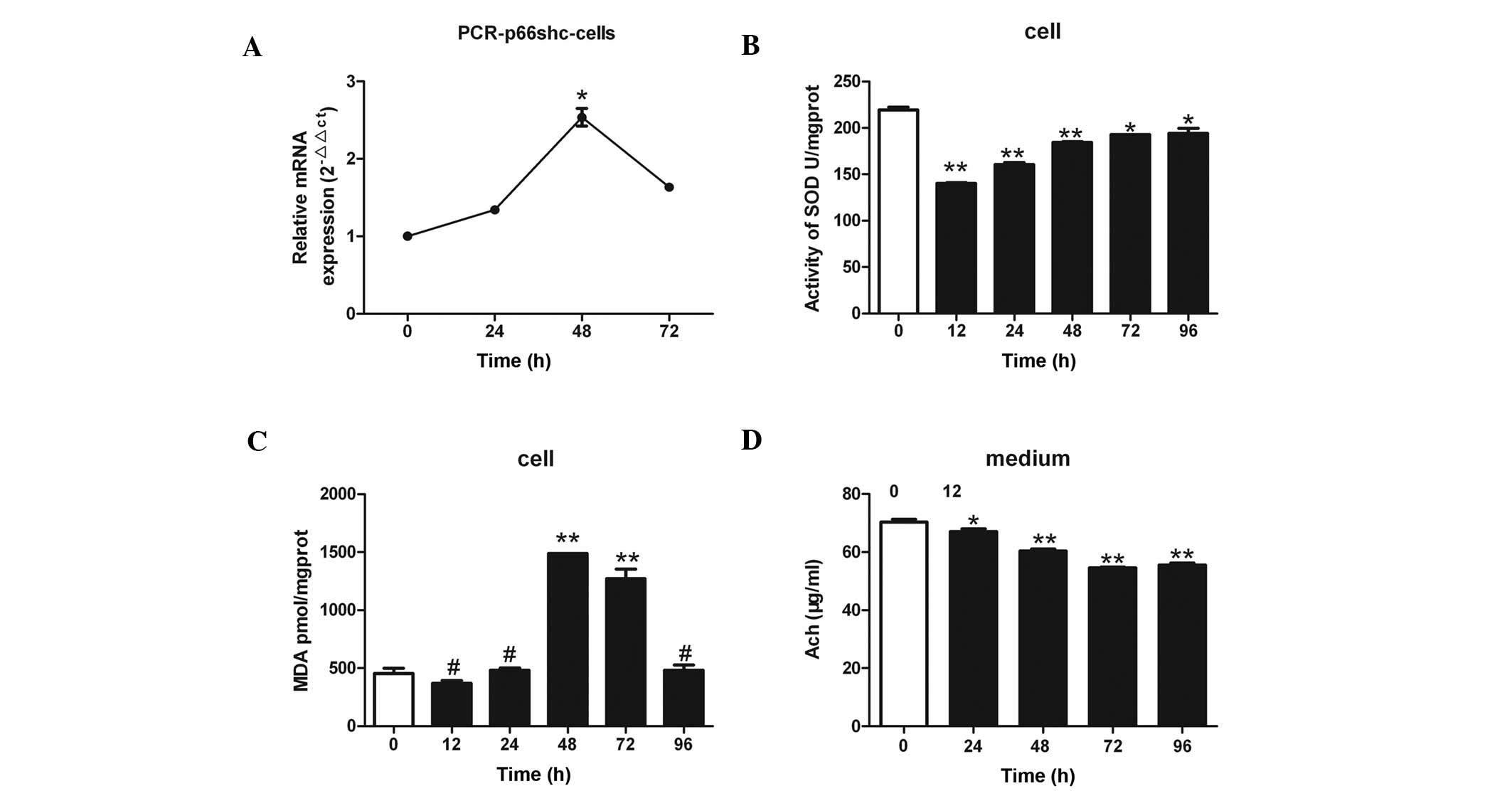

The results of the qPCR demonstrated that the mRNA

expression levels of p66shc were significantly increased in the

SH-SY5Y cells following treatment with 3 µmol/l anisomycin, in a

time-dependent manner (P<0.01; Fig.

3A), as compared with the mRNA expression levels at 0 h. The

differences in the threshold cycle (Ct) values between p66shc mRNA

and 18S rRNA were compared. The mRNA expression levels of p66shc

increased 2.5 fold following treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with 3

µmol/l anisomycin for 48 h, as compared with the mRNA expression

levels at 0 h. (P<0.01; Fig. 3A).

These results suggest that anisomycin-induced damage in SH-SY5Y

cells may be associated with significantly increased p66shc

expression.

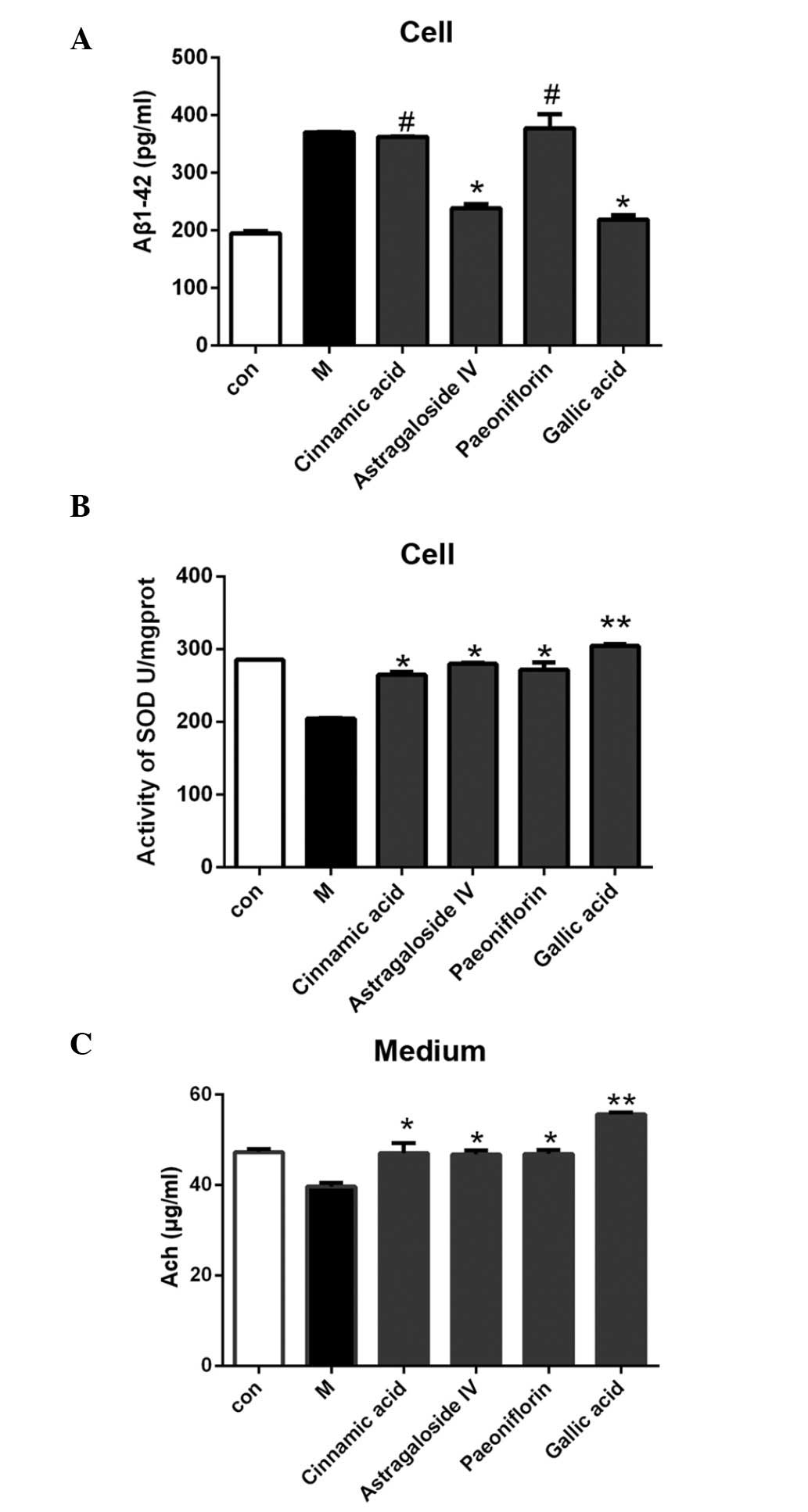

| Figure 3.(A) Treatment of SH-SY5Y human

neuroblastoma cells with 3 µmol/l anisomycin was associated with

significant changes in p66shc mRNA expression levels. The p66shc

mRNA expression levels increased by 2.5-fold after 48 h of

anisomycin treatment, as compared with 0 h. (B) Treatment of

SH-SY5Y cells with 3 µmol/l anisomycin for various lengths of time

(0, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h) resulted in significantly reduced SOD

activity in the cells, as compared with 0 h of treatment. The

decrease in SOD activity was more evident after 12, 24 and 48 h of

anisomycin treatment. (C) SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 3 µmol/l

anisomycin for various lengths of time (0, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96

h). The protein expression levels of MDA were significantly

increased after 48 and 72 h of treatment, as compared with 0 h. (D)

SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 3 µmol/l anisomycin for various

lengths of time (0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h) and the levels of Ach

secreted from the cells were significantly reduced after 24, 48, 72

and 96 h, as compared with 0 h. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation of triplicate experiments. #P>0.05

vs. 0 h; *P<0.05 vs. 0 h; **P<0.01 vs. 0 h. SOD, superoxide

dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; Ach, acetylcholine. |

Anisomycin decreases the activity of

SOD and increases the levels of MDA in SH-SY5Y cells

SOD activity was significantly reduced in a

time-dependent manner in the SH-SY5Y cells following treatment with

3 µmol/l anisomycin, as compared with SOD activity at 0 h

(P<0.01; Fig. 3B), and this was

most pronounced after 12, 24, and 48 h of anisomycin treatment

(P<0.01). In addition, the protein expression levels of MDA in

the SH-SY5Y cells were significantly increased after 48 and 72 h of

anisomycin treatment, as compared with 0 h of treatment (P<0.01;

Fig. 3C).

Anisomycin reduces the levels of Ach

in cell culture supernatants

The levels of Ach secreted by the SH-SY5Y cells

significantly decreased over time following treatment of the cells

with 3 µmol/l anisomycin, as compared with the levels at 0 h

(P<0.01; Fig 3D). The most

significant decreases in Ach secretion occurred following 48, 72

and 96 h treatment with anisomycin (P<0.01).

Screening of the small molecule

compounds cinnamic acid, astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin and gallic

acid

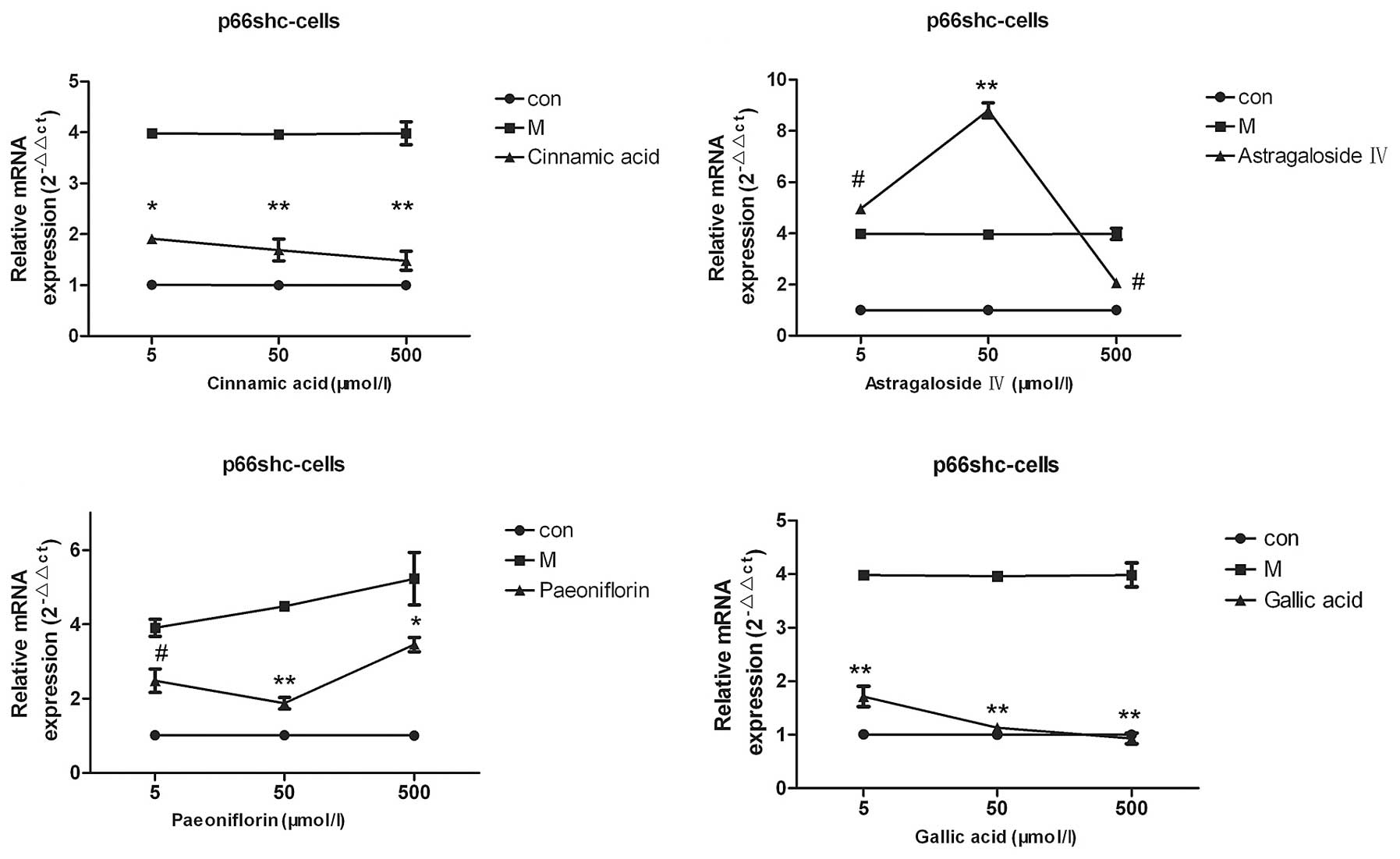

The results of the qPCR demonstrated that various

concentrations (5, 50 or 500 µmol/l) of cinnamic acid, paeoniflorin

and gallic acid were able to reduce the p66shc mRNA expression

levels, as compared with the model group (P<0.05; Fig. 4), whereas, only 500 µmol/l

astragaloside IV was able to decrease the p66shc mRNA expression

levels in the cell model (P<0.05). Of the four compounds

screened, cinnamic acid and gallic acid exerted the most pronounced

effects and decreased the p66shc mRNA expression levels to those

that resembled the mRNA expression levels of the cells in the

normal group (Fig. 4).

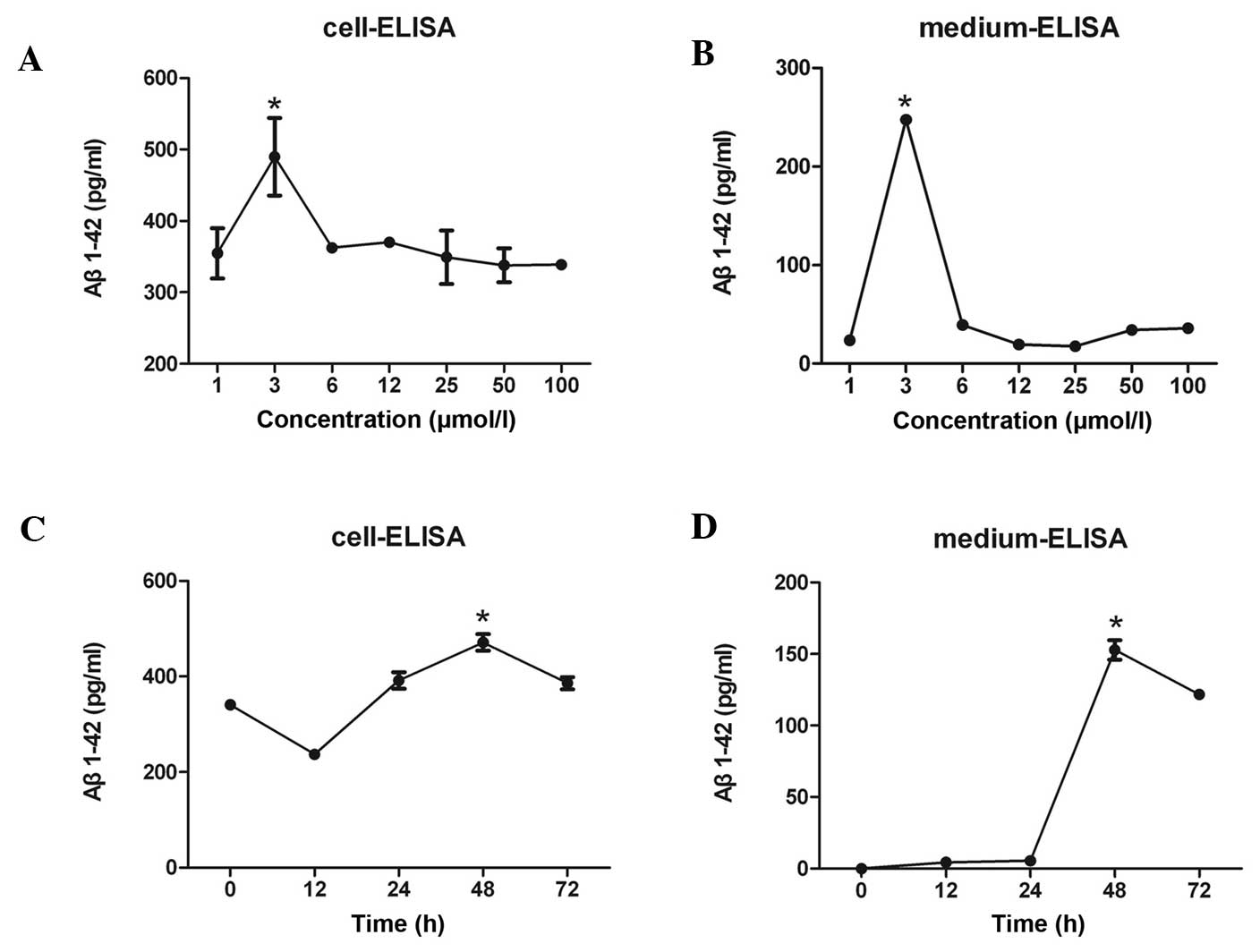

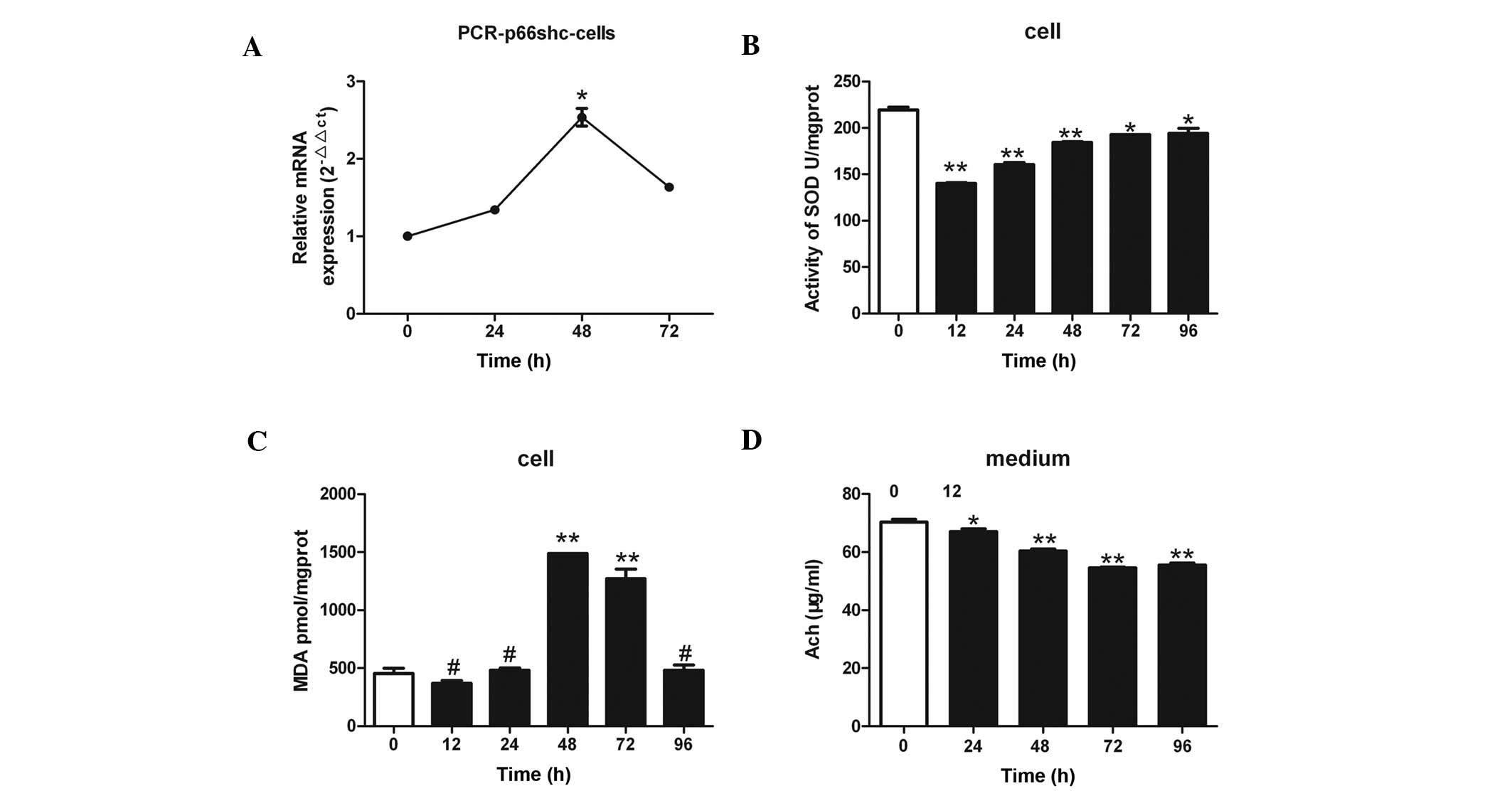

Western blotting demonstrated that 50 µmol/l

cinnamic acid, paeoniflorin or gallic acid reduced the protein

expression levels of p66shc, although the effects of gallic acid

were the most significant (P<0.05; Fig. 5).

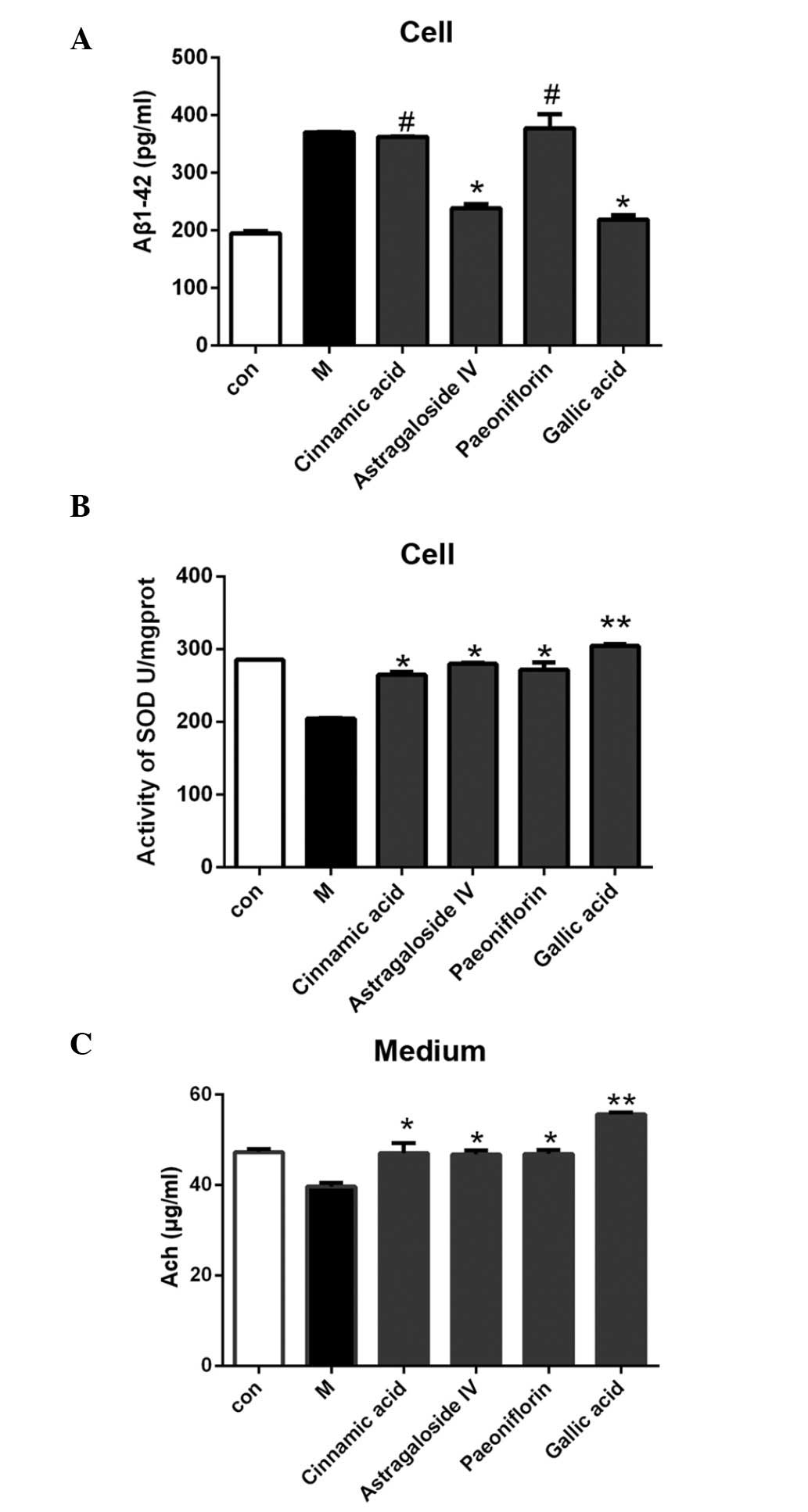

As compared with the model group, treatment with 50

µmol/l cinnamic acid and paeoniflorin exerted no significant

effects on the secretion of Aβ1–42 from the SH-SY5Y cells, whereas

treatment with 50 µmol/l astragaloside IV or gallic acid was

associated with decreased Aβ1–42 secretion levels; however, the

effects of gallic acid were more significant (P<0.05; Fig. 6A). As compared with the model group,

treatment of the cells with 50 µmol/l cinnamic acid, astragaloside

IV, paeoniflorin or gallic acid increased the SOD activity and Ach

expression levels in the model cells, with the effects of gallic

acid being particularly significant (P<0.01; Fig. 6B and C).

| Figure 6.(A) As compared with the cells in the

model group, Aβ secretion was reduced following treatment with 50

µmol/l astragaloside IV or gallic acid, with the effects of gallic

acid being more significant. (B) The cell model was treated with 50

µmol/l cinnamic acid, astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin or gallic

acid. As compared with the untreated model group, the SOD activity

was significantly elevated following treatment with the small

molecule compounds. (C) As compared with the untreated model group,

the Ach level was elevated after treatment with 50 µmol/l cinnamic

acid, astragaloside IV, paeoniflorin, or gallic acid. The effects

of gallic acid on Aβ secretion, SOD activity, and Ach secretion,

were the most significant of all the small molecule compounds. Data

are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

#P>0.05 vs. the model group; *P<0.05 vs. the model

group; **P<0.01 vs. the model group. Aβ, β-amyloid; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; Ach, acetylcholine, Con, the control group;

M, the model group. |

Discussion

The pathogenesis of AD is very complex. Currently,

the Aβ hypothesis, in which Aβ destroys synaptic structures and

impairs hippocampal long-term potentiation, resulting in a decline

in learning and memory functions, is widely accepted (17). Extracellular Aβ is associated with

neuronal dysfunction by permeabilising lipid bilayers, reducing

membrane fluidity and inducing the inflammatory cascade and

oxidative stress (1–6).

Previous studies have associated the loss of p66shc

with reduced levels of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress

responses in the brain, improved spatial learning and memory, and

prevention of ageing-induced behavioral changes (7–13,20,21).

In addition, p66shc has been associated with an increased lifespan,

which is predominantly reflected in the reduction of brain atrophy,

the maintenance of behavioral plasticity and the increase in the

overall level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (22). Furthermore, Sone et al

(23) demonstrated a positive

correlation between the gene expression levels of p66shc and

ageing, and this correlation was particularly evident in the

brain.

The levels of p66shc have been associated with

oxidation and ageing of the nervous system (10). AD is a neurodegenerative disorder, in

which Aβ formation represents an important mechanism underlying its

pathogenesis; therefore, compounds that are able to reduce the

production of Aβ in neurons and block cell damage may be considered

in the prevention and treatment of patients with AD.

The results of the present study demonstrated that

anisomycin-induced neuronal damage increased Aβ1–42 secretion, and

this was associated with concomitant upregulation of p66shc

expression, an increase in the cellular response to oxidative

stress, and a reduction in neurotransmitter production. Thus

suggesting that anisomycin may induce neuronal damage and increase

cellular deposition of Aβ1–42 via an oxidative stress pathway.

Among the four small molecule compounds examined in

the present study, gallic acid was able to downregulate p66shc

expression in the SH-SY5Y cells, and reduce anisomycin-induced Aβ

deposition, enhance SOD activity and increase Ach secretion. These

results suggested that gallic acid was able to reduce

anisomycin-induced Aβ deposition in the SH-SY5Y cells via the

downregulation of p66shc expression. In addition, cinnamic acid,

astragaloside IV and paeoniflorin were able to suppress the

expression of p66shc, and were able to attenuate anisomycin-induced

Aβ deposition. Astragaloside IV reduced Aβ secretion from cells,

possibly via mechanisms other than downregulation of p66shc.

Although cinnamic acid and paeoniflorin were unable to directly

decrease Aβ secretion, they did reduce the oxidative stress

responses to varying extents and enhanced neurotransmitter

production; thus suggesting that they were able to exhibit minor

neuroprotective effects, although these were less significant than

those detected for gallic acid.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

treatment of SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells with anisomycin was

associated with nerve damage and increased Aβ secretion. In

addition, gallic acid was able to downregulate p66shc expression in

SH-SY5Y cells, which may have reduced anisomycin-induced Aβ

deposition; thus suggesting that gallic acid exerted protective

effects on SH-SY5Y cells, which may be considered a novel

therapeutic strategy in the treatment of patients with AD.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by a grant from The

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81373706,

81373619 and 81202811).

References

|

1

|

Götz J, Deters N, Doldissen A, Bokhari L,

Ke Y, Wiesner A, Schonrock N and Ittner LM: A decade of tau

transgenic animal models and beyond. Brain Pathol. 17:91–103. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mattson MP: Pathways towards and away

fromA lzheimer's disease. Nature. 430:631–639. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Minter MR, Taylor JM and Crack PJ: The

contribution of neuro-inflammation to amyloid toxicity in

Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem Oct. 28:2015.(Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

4

|

Wimo A: Long-term effects of A lzheimer's

disease treatment. Lancet Neurol. doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00302-6. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V,

Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris JC, Yarasheski KE and Bateman RJ:

Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease.

Science. 330:17742010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci

G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L and Pelicci PG: The p66shc

adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in

mammals. Nature. 402:309–313. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shan W, Gao L, Zeng W, Hu Y, Wang G, Li M,

Zhou J, Ma X, Tian X and Yao J: Activation of the SIRT1/p66shc

antiapoptosis pathway via carnosic acid-induced inhibition of

miR-34a protects rats against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Cell Death Dis. 6:e18332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Priami C, De Michele G, Cotelli F,

Cellerino A, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG and Migliaccio E: Modelling the

p53/p66Shc Aging Pathway in the Shortest Living Vertebrate

Nothobranchius Furzeri. Aging Dis. 6:95–108. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Li X, Gao D, Wang H, Li X, Yang J, Yan X,

Liu Z and Ma Z: Negative feedback loop between p66Shc and ZEB1

regulates fibrotic EMT response in lung cancer cells. Cell Death

Dis. 6:e17082015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bhat SS, Anand D and Khanday FA: p66Shc as

a switch in bringing about contrasting responses in cell growth,

Implications on cell proliferation and apoptosis. Mol Cancer.

14:762015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Perrini S, Tortosa F, Natalicchio A,

Pacelli C, Cignarelli A, Palmieri VO, Caccioppoli C, De Stefano F,

Porro S, Leonardini A, et al: The p66Shc Protein Controls Redox

Signaling and Oxidation-Dependent DNA Damage in Human Liver Cells.

Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol: Sep. 3:2015.(Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

12

|

Sampaio SF, Branco AF, Wojtala A,

Vega-Naredo I, Wieckowski MR and Oliveira PJ: p66Shc signaling is

involved in stress responses elicited by anthracycline treatment of

rat cardiomyoblasts. Arch Toxicol Aug. 30:2015.(Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

13

|

Guo X, Wu X, Ren L, Liu G and Li L:

Epigenetic mechanisms of amyloid-β production in anisomycin-treated

SH-SY5Y cells. Neuroscience. 194:272–281. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pena RR, Pereira-Caixeta AR, Moraes MF and

Pereira GS: Anisomycin administered in the olfactory bulb and

dorsal hippocampus impaired social recognition memory consolidation

in different time-points. Brain Res Bull. 109:151–157. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sorg BA, Todd RP, Slaker M and Churchill

L: Anisomycin in the medial prefrontal cortex reduces

reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memories in the rat

self-administration model. Neuropharmacology. 92:25–33. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Dubue JD, McKinney TL, Treit D and Dickson

CT: Intrahippocampal Anisomycin Impairs Spatial Performance on the

Morris Water Maze. J Neurosci. 35:11118–11124. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hardy J and Selkoe DJ: The amyloid

hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: Progress and problems on the

road to therapeutics. Science. 297:353–356. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zou G, Du X, Duan T and Liu T: Application

of a NotI subtraction and methylation specific genome subtractive

hybridization technique in the detection of genomic DNA methylation

differences between hydatidiform moles and villi. Mol Med Rep.

7:77–82. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen Q, Qiu C, Huang Y, Jiang L, Huang Q,

Guo L and Liu T: Human amniotic epithelial cell feeder layers

maintain iPS cell pluripotency by inhibiting endogenous DNA

methyltransferase 1. Exp Ther Med. 6:1145–1154. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Berry A, Greco A, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG,

de Kloet R, Alleva E, Minghetti L and Cirulli F: Deletion of the

lifespan determinant p66(Shc) improves performance in a spatial

memory task, decreases levels of oxidative stress markers in the

hippocampus and increases levels of the neurotrophin BDNF in adult

mice. Exp Gerontol. 43:200–208. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Berry A, Capone F, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG,

de Kloet ER, Alleva E, Minghetti L and Cirulli F: Deletion of the

life span determinant p66Shc prevents age-dependent increases in

emotionality and pain sensitivity in mice. Exp Gerontol. 42:37–45.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Berry A and Cirulli F: The p66(Shc) gene

paves the way for healthspan: Evolutionary and mechanistic

perspectives. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 37:790–802. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sone K, Mori M and Mori N: Selective

upregulation of p66-Shc gene expression in the liver and brain of

aged rats. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 55:744–748. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|