Introduction

Cardiac hypertrophy is associated with the

thickening of the heart muscle (1)

and the risk factors of cardiac hypertrophy include hypertension,

obesity, muscular dystrophy, cardiomyopathy or heart failure

(2). Furthermore, it has been

demonstrated that genetic factors and signaling pathways may

participate in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy, which may

be associated with an enhanced risk of sudden cardiac death and

cardiovascular mortality (3,4). As the early symptoms of this disease

are difficult to detect, it is crucial that novel molecular markers

for the early therapy of cardiac hypertrophy are identified.

Molecular markers of cardiac hypertrophy have been

identified (5). In particular,

Kontaraki et al (6)

identified GATA4, myocardin and β-myosin heavy

chain as early cardiac marker genes. Furthermore, smooth muscle

α-actin has been demonstrated to be a molecular marker for

pressure-overload hypertrophy (7).

Using mouse models, Qing et al (8) have previously reported that

miR-22 serves a crucial function in the regulation of

cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac remodeling. Fibroblast growth

factor 21, which is an endocrine factor, has a protective role

in cardiac cells (9). As an

increasing number of molecular markers are identified, mathematical

models can be constructed to predict the risk of cancer (10).

Various types of mathematical models have

contributed to the prediction of diseases. Flux balance models of

cellular metabolism have been used to analyze and predict

transcriptional regulation under certain conditions, including

catabolite repression and amino acid biosynthesis pathway

repression (11). Furthermore,

various genes and pathways associated with differentiation,

including MAOA and ADH1B metabolic genes in human pulmonary type II

cells (12) and nuclear

factor-kappaB pathway in a mouse model of genitourinary

inflammation (13), have been

identified via mathematical cluster analysis using GENECLUSTER,

which is a publicly available computer package that contributed to

the establishment of an effective treatment for acute promyelocytic

leukemia (14). According to a

previous study conducted by Kondo and Miura (15), the reaction-diffusion model is

effective in biological pattern formation. Thus, these previous

studies suggest the mathematical modeling is a useful tool for the

prediction of disease.

Using microarray data downloaded from the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession, GSE21600), which

included 35 heart samples harvested from a Wistar rat on

postoperative days 1, 6 and 42 following aorta ligation and

sham-operated Wistar rats, respectively. Hellman et al

(16) demonstrated a correlation

between hyaluronan concentration and specific gene expression

levels using SPSS software. Analysis of the correlation matrix was

performed according to the Principal components method (17), and orthogonal partial least

squares-discrimination analysis was used to analyze the datasets of

GSE21600, in which the previous clustering, including extracellular

matrix and adhesion molecules were confirmed, and fatty acid

metabolism, glucose metabolism, mitochondria and atherosclerosis

were detected as the new clustering (18). However, these previous two studies

failed to predict the changing trends of genes in this disease.

Hence, the present study aimed to reanalyze the expression profiles

of GSE21600 in order to construct a predictive model of cardiac

hypertrophy using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) method.

GSE21600 microarray data was used to identify differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) using a Limma package in R (version.

3.26.5), which calculates linear models of microarray data. Common

DEGs were used to construct a mathematical model in order to

predict the expression levels of genes in the cardiac hypertrophy

samples. The mathematical model was verified receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve and the consistency of predictive and

measurement data. The present study may be useful for the early

prediction of changing trends in cardiac hypertrophy disease at the

gene level.

Materials and methods

Data preprocessing and DEGs

screening

GSE21600 microarray data were downloaded from the

GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (16). GSE21600 included data from 35 heart

samples harvested from 36 Wistar rats which were excised on

postoperative days 1, 6 and 42 following aorta ligation and

sham-operated groups, respectively. Each group contained six

samples at each time point, with the exception of the samples

harvested from the aorta ligated group at 6 days, where n=5. The

microarray platform of GSE21600 was Illumina GPL6101 RatRef-12

expression bead chip (version 1.0; Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA,

USA).

Samples were divided into three groups: Day 1 (D1),

day 6 (D6) and day 42 (D42). DEGs between the postoperative and

sham-operated samples were identified in these three groups,

respectively. Firstly, normalization of the microarray data was

performed in the R language (19,20), and

DEGs were subsequently identified using a Limma package in R

(21). False discovery rate (FDR)

was used to adjust the P-value, according to the method outlined by

Benjamin and Hochberg (22).

FDR<0.05 and >1 log2fold change (FC) were chosen

as the cut-off criteria.

Specific gene screening

In order to screen the specific expression levels of

genes at each time point, DEGs were compared between the two

groups. Subsequently, hierarchical clustering analysis (23) was performed on the common DEGs in the

three groups.

Sorting algorithm and construction of

the mathematical model

Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) is a method that

is commonly widely used in microarray classification to obtain

discrimination function. LDA analysis can be performed when there

are ≥2 groups and each group contains >2 variables (24,25). In

this method, a linear equation based on the variations in the two

groups is established: Y=a + b11 + b22 +…+ bnXn, where ‘a’

represents a constant and ‘b1,b2 … and bn’ represents the

regression coefficient. In the present study, the cardiac

hypertrophy samples were defined as ‘1’ and the control samples

were defined as ‘-1’. Based on the dynamic expression changes of

the common DEGs detected in the D1 group, the expression pattern in

the D42 group was predicted via the calculated mathematical model

constructed using the LDA method (26).

Verification of the mathematical

model

Disease classification models are typically

determined using multivariate regression analysis (27,28), ROC

curve (29–32) or prospective validation (33). ROC curve was used in the present

study in order to evaluate the discriminant effect of the

mathematical model and directly observe the accuracy of the present

analysis method. Indices, including specificity and sensitivity,

were calculated in order to estimate the predictive ability of LDA,

in addition to area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curve, which

was also calculated to estimate accuracy. In the present study, AUC

was used to distinguish non-accuracy (AUC≤0.5), low accuracy

(0.5<AUC≤0.7), moderate accuracy (0.7<AUC≤0.9) and high

accuracy (0.9<AUC<1). Furthermore, by comparing the

prediction data with the measurement data in the D42 samples, the

consistency of two sets of data was evaluated.

Results

Identification, comparison and feature

selection of DEGs

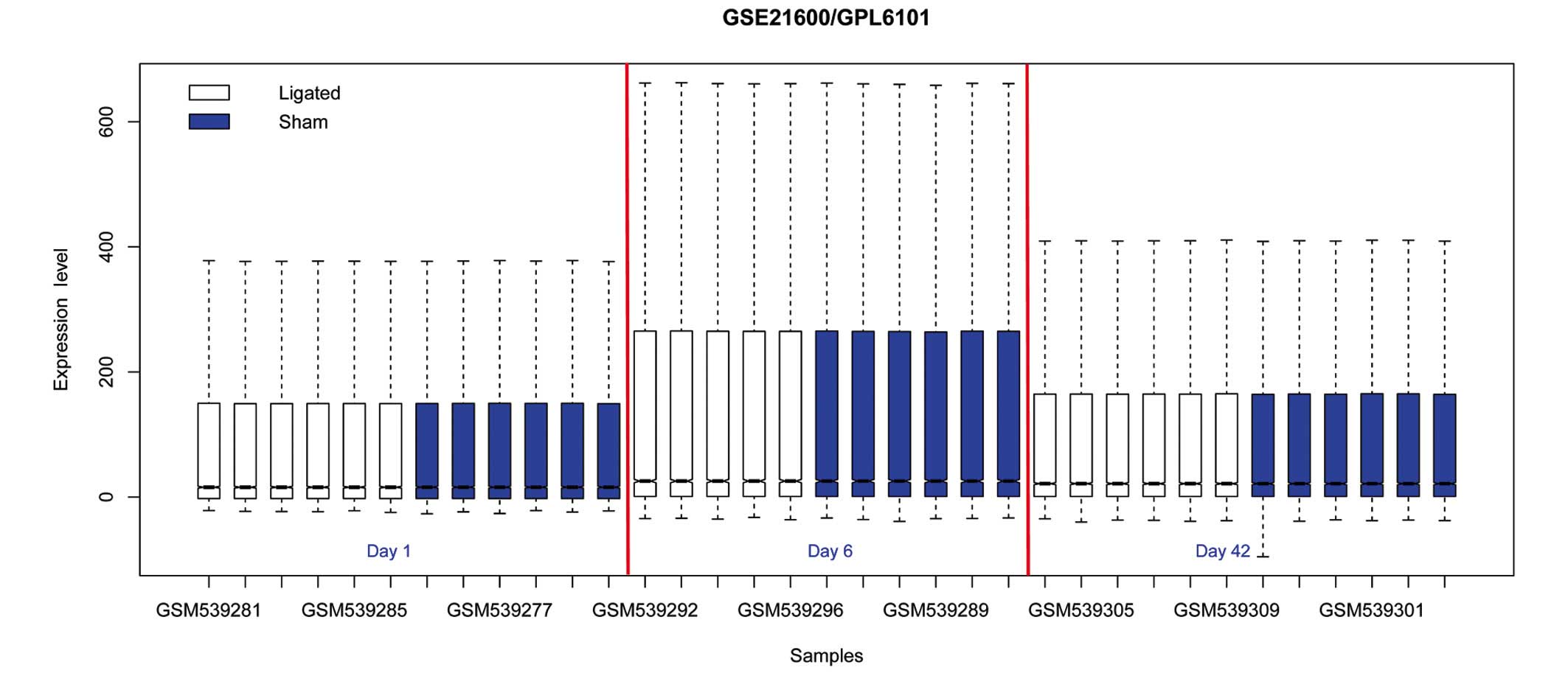

Normalization of the microarray data is presented in

Fig. 1. DEGs were identified, and

the genes with FDR<0.05 and >1 log2FC were considered as

differentially expressed between the ligated samples and

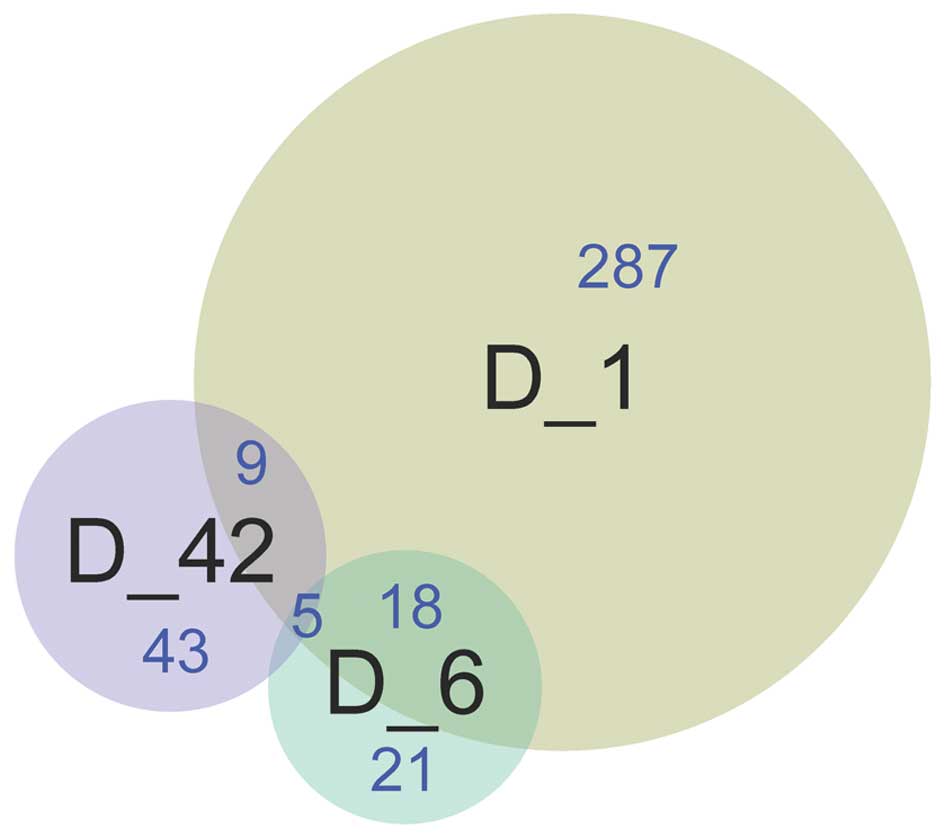

sham-operated samples. A total of 319, 44 and 57 DEGs were

identified in the D1, D6 and D42 groups respectively.

A total of 23 DEGs were detected between the D1 and

D6 groups, 14 DEGs were detected between the D1 and D42 groups, and

five DEGs were identified between the D6 and D42 groups. Five

common DEGs, including A kinase interacting protein 1

(AKIP1), ankyrin repeat domain 23 (ANKRD23), latent

transforming growth factor beta binding protein (LTBP2),

transforming growth factor (TGF)-β2 and tumor necrosis

factor receptor superfamily member 12a (TNFRSF12A), were

identified among the three groups (Fig.

2).

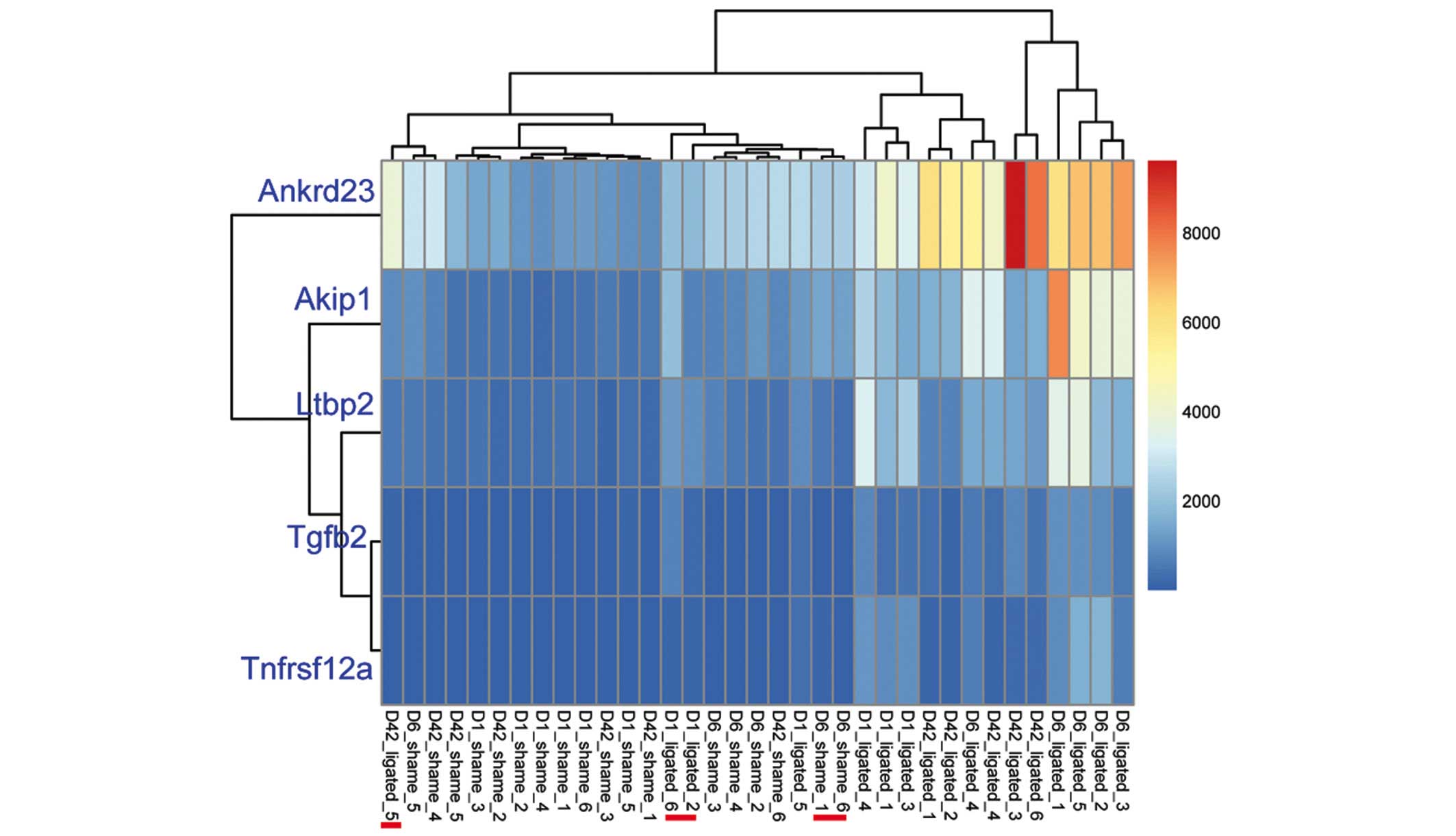

Clustering analysis of the five common DEGs

demonstrated that the sham operated and ligated samples were

respectively clustered together; however, three ligated samples

(16.67%; 3/18) were mixed into the operated group and two

sham-operated samples (11.76%; 2/17) were mixed into the ligated

group (Fig. 3). These five common

DEGs were identified as downregulated genes (Table I).

| Table I.Expression levels of five common

differentially expressed genes the in aorta ligated operation group

were calculated, as compared with the sham operated group. |

Table I.

Expression levels of five common

differentially expressed genes the in aorta ligated operation group

were calculated, as compared with the sham operated group.

| Gene | Day 1 | Day 6 | Day 42 |

|---|

| AKIP1 | −1.24914 | −1.36699 | −1.80092 |

| ANKRD23 | −2.90253 | −3.69624 | −2.85077 |

| LTBP2 | −3.68846 | −4.20566 | −2.02513 |

| TGFB2 | −2.15313 | −2.11814 | −1.75841 |

|

TNFRSF12A | −1.99987 | −2.08827 | −1.54923 |

Construction and verification of the

mathematical model

Based on the expression levels and dynamic changes

detected in the five common DEGs, a linear equation between the D1

and D42 groups was calculated as follows: y=1.526×-186.671; where

‘y’ and ‘x’ represent the expression levels in the D42 and D1

groups, respectively.

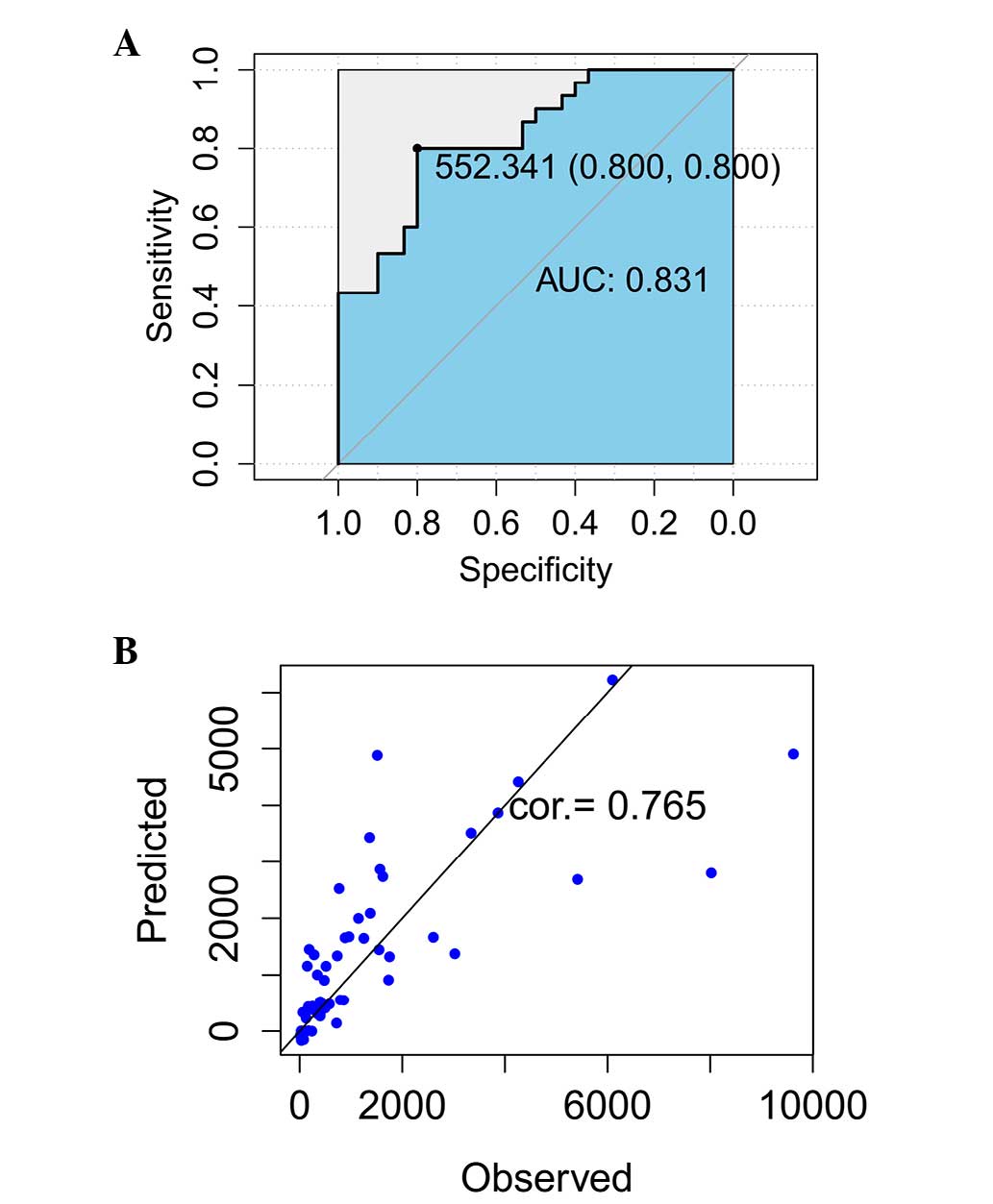

Assessment of the ROC curve demonstrated that AUC

was 0.831, which indicated that the predictive accuracy was 83.1%

and the specificity and sensitivity were 0.8, respectively

(Fig. 4A). By comparing the

predictive and measurement data at 42 days (Table II), the consistency of these two

datasets was calculated to be 76.5% (Fig. 4B).

| Table II.Predicted data at day 42 using a

linear equation of the gene expression levels of cardiac

hypertrophy. |

Table II.

Predicted data at day 42 using a

linear equation of the gene expression levels of cardiac

hypertrophy.

| Gene accession | State | Expression on day

1 | Expression on day

42 | Predicted on day

42 |

|---|

| GSM539275 | 1 | 332.1987 | 337.3279 | 326.1898781 |

| GSM539276 | 1 | 272.2375 | 126.1764 | 235.327208 |

| GSM539277 | 1 | 485.7471 | 792.9784 | 558.8706386 |

| GSM539278 | 1 | 778.9512 | 344.6311 | 1,003.179749 |

| GSM539279 | 1 | 320.8331 | 108.7458 | 308.9669279 |

| GSM539280 | 1 | 716.3563 | 479.7876 | 908.3260809 |

| GSM539281 | −1 | 85.13754 | 66.26252 | −48.1961695 |

| GSM539282 | −1 | 71.55708 | 13.26508 | −68.775425 |

| GSM539283 | −1 | 50.69723 | 41.25237 | −100.385561 |

| GSM539284 | −1 | 23.54682 | 75.99313 | −141.528145 |

| GSM539285 | −1 | 124.7012 | 29.73599 | 11.75692997 |

| GSM539286 | −1 | 49.61586 | 52.55618 | −102.024223 |

| GSM539275 | 1 | 4,201.869 | 6,096.354 | 6,190.124821 |

| GSM539276 | 1 | 1,882.365 | 5,415.158 | 2,675.24642 |

| GSM539277 | 1 | 3,337.275 | 9,621.91 | 4,879.955589 |

| GSM539278 | 1 | 3,016.572 | 4,261.265 | 4,393.975807 |

| GSM539279 | 1 | 2,658.368 | 3,865.638 | 3,851.168593 |

| GSM539280 | 1 | 1,956.894 | 8,021.108 | 2,788.184519 |

| GSM539281 | −1 | 1,219.844 | 959.4762 | 1,671.290077 |

| GSM539282 | −1 | 1,070.036 | 1,546.261 | 1,444.277361 |

| GSM539283 | −1 | 1,431.854 | 1,145.456 | 1,992.561078 |

| GSM539284 | −1 | 1,024.116 | 3,023.837 | 1,374.692133 |

| GSM539285 | −1 | 988.543 | 1,751.745 | 1,320.786311 |

| GSM539286 | −1 | 1,213.691 | 2,605.091 | 1,661.966081 |

| GSM539275 | 1 | 880.5447 | 147.3087 | 1,157.130248 |

| GSM539276 | 1 | 126.5936 | 169.5375 | 14.62459301 |

| GSM539277 | 1 | 1,011.612 | 281.1071 | 1,355.744099 |

| GSM539278 | 1 | 1,073.774 | 185.5347 | 1,449.941769 |

| GSM539279 | 1 | 340.023 | 62.10585 | 338.0464919 |

| GSM539280 | 1 | 122.0065 | 237.4351 | 7.673495398 |

| GSM539281 | −1 | 36.33411 | 32.24878 | −122.150826 |

| GSM539282 | −1 | 50.67635 | 24.24548 | −100.417201 |

| GSM539283 | −1 | 36.68185 | 45.16885 | −121.623876 |

| GSM539284 | −1 | 30.85578 | 71.55927 | −130.452456 |

| GSM539285 | −1 | 15.40947 | 32.20256 | −153.859142 |

| GSM539286 | −1 | 34.06184 | 51.90232 | −125.594128 |

| GSM539275 | 1 | 1,915.488 | 1,621.039 | 2,725.439616 |

| GSM539276 | 1 | 719.9728 | 1,732.95 | 913.8063723 |

| GSM539277 | 1 | 1,491.145 | 1,375.875 | 2,082.408155 |

| GSM539278 | 1 | 2,425.283 | 3,341.205 | 3,497.961428 |

| GSM539279 | 1 | 1,208.035 | 885.0079 | 1,653.395218 |

| GSM539280 | 1 | 1,999.254 | 1,564.762 | 2,852.375074 |

| GSM539281 | −1 | 391.4185 | 495.3794 | 415.929062 |

| GSM539282 | −1 | 355.6202 | 400.3427 | 361.6818301 |

| GSM539283 | −1 | 437.2545 | 578.2272 | 485.3870006 |

| GSM539284 | −1 | 215.4102 | 719.1659 | 149.2135176 |

| GSM539285 | −1 | 464.529 | 402.5466 | 526.717626 |

| GSM539286 | −1 | 483.1193 | 857.3302 | 554.8885815 |

| GSM539275 | 1 | 1,776.678 | 768.9708 | 2,515.092804 |

| GSM539276 | 1 | 998.7648 | 732.2133 | 1,336.275995 |

| GSM539277 | 1 | 2,373.809 | 1,362.486 | 3,419.959903 |

| GSM539278 | 1 | 3,322.548 | 1,513.086 | 4,857.638915 |

| GSM539279 | 1 | 879.2261 | 513.2602 | 1,155.132097 |

| GSM539280 | 1 | 1,201.621 | 1,250.521 | 1,643.675713 |

| GSM539281 | −1 | 411.144 | 251.4373 | 445.8202516 |

| GSM539282 | −1 | 375.7809 | 208.7139 | 392.2325034 |

| GSM539283 | −1 | 406.536 | 168.1061 | 438.837483 |

| GSM539284 | −1 | 297.8341 | 399.4494 | 274.1152146 |

| GSM539285 | −1 | 322.7278 | 352.2844 | 311.8380763 |

| GSM539286 | −1 | 316.283 | 400.1669 | 302.0718985 |

Discussion

In the present study, the expression profiles of

sham operated and ligated heart samples harvested from a Wistar rat

were analyzed and 319, 44 and 57 DEGs were subsequently identified

in the D1, D6 and D42 groups, respectively. AKIP1,

ANKRD23, LTBP2, TGF-β2 and TNFRSF12A

were identified as common DEGs among the three groups, and their

association with cardiac hypertrophy has previously been

demonstrated (34–37). AKIP1 was identified as a key

regulator of heart function via the cAMP-dependent protein kinase

signaling pathway (38). During

periods of the oxidant stress, the expression of AKIP1 is

capable of protecting cardiac myocytes from the ischemic injury via

enhanced mitochondrial integrity (38). Furthermore, the expression of

AKIP1 may also protect the heart via mitochondrial stress

adaptation (39), and it has been

demonstrated that mitochondrial DNA damage may contribute to the

development of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (40). These results suggested that

AKIP1 may serve a crucial function in the development of

cardiac hypertrophy via mitochondrial stress adaptation mechanisms.

Hellman et al (16) have

previously demonstrated that LTBP2 and TGF-β2 are

associated with the development of cardiac hypertrophy.

LTBP2, which belongs to the fibrillin superfamily, regulates

the release of TGF-β1 (41,42).

Previous studies have demonstrated that TGF-β, including

TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3, have an important

role in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy by stimulating the

proliferation of cardiomyocytes (43,44).

These results demonstrated that LTBP2 and TGF-β2 are

associated with the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. However, the

role of ANKRD23 and TNFRSF12A in the development of

cardiac hypertrophy is yet to be elucidated. As the results of the

present study demonstrated that they were detected as common genes

in the three groups, we hypothesize that AKIP1,

ANKRD23, LTBP2, TGF-β2 and TNFRSF12A

may contribute to the development of cardiac hypertrophy.

Numerous mathematical techniques have been developed

in order to analyze large datasets, and mathematical modeling is a

useful and powerful tool for the analysis of gene expression

patterns (14). LDA is a well-known

multivariate technique that is used for dimension reduction and

classification (45). A 3-gene

model, TNFRSF8, BATF3 and TMOD1, which was

obtained by LDA and leave-one-out cross-validation, was previously

used to separate ALK (−) and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma from

peripheral T-cell lymphoma, and the accuracy of the model was ~97%

(46). Furthermore, a

class-prediction model of patients with Graft-vs-host disease was

previously constructed using LDA, and the accuracy was 63–80%, as

estimated by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction (47). ROC, which directly

displays the correlation of specificity and sensitivity can be used

to assess the accuracy of diagnostic tests (48). In a previous study conducted by

Barretina et al (49), Cancer

Cell Line Encyclopedia, which is a predictive model, was

cross-validated by specificity and sensitivity of the ROC curve and

used to predict the drug response to gene expression, including

topoisomerase inhibitors associated with Schlafen family member 11.

Similarly, a predictions model has previously been constructed for

dementia using LDA and verified by ROC curve, and the accuracy of

the model was 66%; whereas the specificity and sensitivity were 73%

and 64%, respectively (50). In the

present study, a prediction model of cardiac hypertrophy was

constructed. The assessment of ROC curve demonstrated that the

predictive accuracy of the model was ~83.1% and the specificity and

sensitivity were 0.8, respectively. By comparing the predictive and

measurement data at 42 days, the consistency of these two datasets

was calculated to be 76.5%. These results suggested that the

present prediction model provides improved predictive ability,

which may contribute to the early prediction of the changing trends

in gene expression exhibited in patients with cardiac hypertrophy

disease. However, to elevate the discrimination ability of the

model, further studies with an increased number of samples and more

suitable machine learning algorithm are required.

In the present study, 319, 44 and 57 DEGs were

detected in D1, D6 and D42 groups, respectively. AKIP1,

ANKRD23, LTBP2, TGF-β2 and TNFRSF12A

were identified as common DEGs. A linear equation was calculated

between the D1 and D42 groups, as follows: y=1.526×-186.671. This

linear equation, which acted as a prediction model of gene

expression levels, may contribute to the early prediction of the

changing trends in cardiac hypertrophy disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors of the present study would like to thank

Fenghe Information Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China) for

in-depth editing and language assistance.

References

|

1

|

Heineke J and Molkentin JD: Regulation of

cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 7:589–600. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM and

Castelli WP: Obesity as an independent risk factor for

cardiovascular disease: A 26-year follow-up of participants in the

Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 67:968–977. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang AY, Wang M, Woo J, Lam CW, Lui SF, Li

PK and Sanderson JE: Inflammation, residual kidney function and

cardiac hypertrophy are interrelated and combine adversely to

enhance mortality and cardiovascular death risk of peritoneal

dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 15:2186–2194. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dunn FG, Burns JM and Hornung RS: Left

ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension. Am Heart J. 122:312–315.

1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Osio A, Tan L, Chen SN, Lombardi R, Nagueh

SF, Shete S, Roberts R, Willerson JT and Marian AJ: Myozenin 2 is a

novel gene for human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res.

100:766–768. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kontaraki JE, Parthenakis FI, Patrianakos

AP, Karalis IK and Vardas PE: Altered expression of early cardiac

marker genes in circulating cells of patients with hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Pathol. 16:329–335. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Black FM, Packer SE, Parker TG, Michael

LH, Roberts R, Schwartz RJ and Schneider MD: The vascular smooth

muscle alpha-actin gene is reactivated during cardiac hypertrophy

provoked by load. J Clin Invest. 88:1581–1588. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Qing YF, Zhou JG, Zhang QB, Wang DS, Li M,

Yang QB, Huang CP, Yin L, Pan SY, Xie WG, et al: Association of

TLR4 Gene rs2149356 polymorphism with primary gouty arthritis in a

case-control study. PLoS One. 8:e648452013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Planavila A, Redondo I, Hondares E,

Vinciguerra M, Munts C, Iglesias R, Gabrielli LA, Sitges M, Giralt

M, van Bilsen M and Villarroya F: Fibroblast growth factor 21

protects against cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Nat Commun.

4:20192013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, Wheatley

K, Harrison C, Harrison G, Rees J, Hann I, Stevens R, Burnett A and

Goldstone A: The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome

in AML: Analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10

trial. The medical research council adult and children's leukaemia

working parties. Blood. 92:2322–2333. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Covert MW, Schilling CH and Palsson B:

Regulation of gene expression in flux balance models of metabolism.

J Theor Biol. 213:73–88. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wade KC, Guttentag SH, Gonzales LW,

Maschhoff KL, Gonzales J, Kolla V, Singhal S and Ballard PL: Gene

induction during differentiation of human pulmonary type II cells

in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 34:727–737. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Saban MR, Hellmich H, Nguyen NB, Winston

J, Hammond TG and Saban R: Time course of LPS-induced gene

expression in a mouse model of genitourinary inflammation. Physiol

Genomics. 5:147–160. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tamayo P, Slonim D, Mesirov J, Zhu Q,

Kitareewan S, Dmitrovsky E, Lander ES and Golub TR: Interpreting

patterns of gene expression with self-organizing maps: Methods and

application to hematopoietic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 96:2907–2912. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kondo S and Miura T: Reaction-diffusion

model as a framework for understanding biological pattern

formation. Science. 329:1616–1620. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hellman U, Mörner S, Engström-Laurent A,

Samuel JL and Waldenström A: Temporal correlation between

transcriptional changes and increased synthesis of hyaluronan in

experimental cardiac hypertrophy. Genomics. 96:73–81. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Revell LJ: Size-correction and principal

components for interspecific comparative studies. Evolution.

12:3258–3268. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Gennebäck N, Malm L, Hellman U,

Waldenström A and Mörner S: Using OPLS-DA to find new hypotheses in

vast amounts of gene expression data-Studying the progression of

cardiac hypertrophy in the heart of aorta ligated rat. Gene.

522:27–36. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Troyanskaya O, Cantor M, Sherlock G, Brown

P, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Botstein D and Altman RB: Missing value

estimation methods for DNA microarrays. Bioinformatics. 17:520–525.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fujita A, Sato JR, de Rodrigues LO,

Ferreira CE and Sogayar MC: Evaluating different methods of

microarray data normalization. BMC Bioinformatics. 7:4692006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Smyth GK Limma: Linear models for

microarray data. Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions

using R and Bioconductor. Gentleman R, Carey V, Huber W, Irizarry R

and Dudiot S: Springer-Verlag London Ltd. (London). 397–420. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Benjamini Y and Hochberg Y: Controlling

the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to

multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 57:289–300. 1995.

|

|

23

|

Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO and

Botstein D: Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression

patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95:14863–14868. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liang J and Du R: Model-based fault

detection and diagnosis of HVAC systems using support vector

machine method. Int J Refrig. 30:1104–1114. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Polat K and Güneş S: Breast cancer

diagnosis using least square support vector machine. Digit Signal

Process. 17:694–701. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Chen LF, Liao HYM, Ko MT, Lin JC and Yu

GJ: A new LDA-based face recognition system which can solve the

small sample size problem. Pattern Recognition. 33:1713–1726. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Jiang H, Deng Y, Chen HS, Tao L, Sha Q,

Chen J, Tsai CJ and Zhang S: Joint analysis of two microarray

gene-expression data sets to select lung adenocarcinoma marker

genes. BMC Bioinformatics. 5:812004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Imai K: Multivariate regression analysis

for the item count technique. J Amer Statist Assoc. 106:407–416.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhou L, Cheng L, Tao L, Jia X, Lu Y and

Liao P: Detection of hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma using

serum proteomics. Acta Otolaryngol. 126:853–860. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Navaglia F, Fogar P, Basso D, Greco E,

Padoan A, Tonidandel L, Fadi E, Zambon CF, Bozzato D, Moz S, et al:

Pancreatic cancer biomarkers discovery by surface-enhanced laser

desorption and ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin

Chem Lab Med. 47:713–723. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hewett R and Kijsanayothin P: Tumor

classification ranking from microarray data. BMC Genomics. 9(Suppl

2): S212008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Roepman P, Schuurman A, Delahaye LJ,

Witteveen AT, Floore AN and Glas AM: A gene expression profile for

detection of sufficient tumour cells in breast tumour tissue:

Microarray diagnosis eligibility. BMC Med Genomics. 2:522009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ye QH, Qin LX, Forgues M, He P, Kim JW,

Peng AC, Simon R, Li Y, Robles AI, Chen Y, et al: Predicting

hepatitis B virus-positive metastatic hepatocellular carcinomas

using gene expression profiling and supervised machine learning.

Nat Med. 9:416–423. 2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yu H, Tigchelaar W, Lu B, van Gilst WH, de

Boer RA, Westenbrink BD and Silljé HH: AKIP1, a cardiac hypertrophy

induced protein that stimulates cardiomyocyte growth via the Akt

pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 14:21378–21393. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Bang ML, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Peterson KL,

Chien KR and Chen J: The muscle ankyrin repeat proteins CARP,

Ankrd2, and DARP are not essential for normal cardiac development

and function at basal conditions and in response to pressure

overload. PloS One. 9:e936382014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kuba K, Zhang L, Imai Y, Arab S, Chen M,

Maekawa Y, Leschnik M, Leibbrandt A, Markovic M, Schwaighofer J, et

al: Impaired heart contractility in Apelin gene-deficient mice

associated with aging and pressure overload. Circ Res. 101:e32–e42.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Dobaczewski M, Chen W and Frangogiannis

NG: Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling in cardiac

remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 51:600–606. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Sastri M, Haushalter KJ, Panneerselvam M,

Chang P, Fridolfsson H, Finley JC, Ng D, Schilling JM, Miyanohara

A, Day ME, et al: A kinase interacting protein (AKIP1) is a key

regulator of cardiac stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:E387–E396.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yu H, Tigchelaar W, Koonen DP, Patel HH,

de Boer RA, van Gilst WH, Westenbrink BD and Silljé HH: AKIP1

expression modulates mitochondrial function in rat neonatal

cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 8:e808152013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dai DF, Johnson SC, Villarin JJ, Chin MT,

Nieves-Cintrón M, Chen T, Marcinek DJ, Dorn GW II, Kang YJ, Prolla

TA, et al: Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediates angiotensin

II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and Galphaq overexpression-induced

heart failure. Circ Res. 108:837–846. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Sinha S, Heagerty AM, Shuttleworth CA and

Kielty CM: Expression of latent TGF-beta binding proteins and

association with TGF-beta1 and fibrillin-1 following arterial

injury. Cardiovasc Res. 53:971–983. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Sterner-Kock A, Thorey IS, Koli K, Wempe

F, Otte J, Bangsow T, Kuhlmeier K, Kirchner T, Jin S, Keski-Oja J

and von Melchner H: Disruption of the gene encoding the latent

transforming growth factor-beta binding protein 4 (LTBP-4) causes

abnormal lung development, cardiomyopathy, and colorectal cancer.

Genes Dev. 16:2264–2273. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bujak M and Frangogiannis NG: The role of

TGF-beta signaling in myocardial infarction and cardiac remodeling.

Cardiovasc Res. 74:184–195. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Dobaczewski M, Chen W and Frangogiannis

NG: Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling in cardiac

remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 51:600–606. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Roth V and Steinhage V: Nonlinear

discriminant analysis using kernel functions. Advances in Neural

Information Processing Systems. 12:Solla SA, Leen TK and Müller KR:

MIT Press. (Cambridge, MA). 568–574. 2000.

|

|

46

|

Agnelli L, Mereu E, Pellegrino E, Limongi

T, Kwee I, Bergaggio E, Ponzoni M, Zamò A, Iqbal J, Piccaluga PP,

et al: European T-Cell Lymphoma Study Group: Identification of a

3-gene model as a powerful diagnostic tool for the recognition of

ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 120:1274–1281.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Baron C, Somogyi R, Greller LD, Rineau V,

Wilkinson P, Cho CR, Cameron MJ, Kelvin DJ, Chagnon P, Roy DC, et

al: Prediction of graft-versus-host disease in humans by donor

gene-expression profiling. PLoS Med. 4:e232007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Beck JR and Shultz EK: The use of relative

operating characteristic (ROC) curves in test performance

evaluation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 110:13–20. 1986.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N,

Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehár J, Kryukov GV,

Sonkin D, et al: The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables

predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature.

483:603–607. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Maroco J, Silva D, Rodrigues A, Guerreiro

M, Santana I and de Mendonça A: Data mining methods in the

prediction of Dementia: A real-data comparison of the accuracy,

sensitivity and specificity of linear discriminant analysis,

logistic regression, neural networks, support vector machines,

classification trees and random forests. BMC Res Notes. 4:2992011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|