Introduction

Radical mastoidectomy has been performed as early as

the 16th century and its main purpose is to eradicate chronic

otitis media or cholesteatoma and create anatomical conditions to

prevent reoccurrence (1). By

anatomic (drainage) results, it is understood that removing

lesions, maintaining unobstructed drainage and reducing

complications both intra and extracranial is required to obtain a

reliable, safe and disease-free middle-ear (2,3). The

usual surgical approach is represented by canal wall-up (CWU) and

the canal wall-down (CWD) mastoidectomies. Intact canal wall

procedures, such as CWU, are known to be associated with high risk

of recurrence and residual inflammatory lesions (4), but at the same time they preserve much

of the anatomy, while radical and radical modified mastoidectomy

techniques, such as CWD, allow for good visualization of structures

and consequently proportional good chances of complete removal of

lesions (5). It is however certain

that while pursuing anatomic results (complete drainage and cavity

cleanliness), the functional results are occasionally poor (hearing

is destroyed or at least gravely impaired) as we have stated in our

previous two studies involving the same cohort of patients

(6,7). We found that recreating the continuity

of the ossicular chain (OC) is paramount both for functional and

anatomical results in middle ear surgery (8,9), but

useless without a well-performed mastoidectomy. These aspects

should not be taken lightly since hearing loss represents one of

the most serious afflictions worldwide (World Health Organization

estimates that between 65 and 330 million individuals suffer from

some form of middle ear suppuration and 50% of them suffer from

hearing impairment) (10). Other

environmental and clinical risk factors cannot be ruled out and the

clinician must always bear in mind that a situation where genetic

predisposition is augmented by environmental factors is common and

even more complicated (10).

Thus, the aim of the present study was to determine

to what extent can a completely and permanently ‘dry ear’ be

expected and identify the potential parameters that most influence

the drainage results.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

The same cohort of patients used in our previous

studies on the long-term functional results of mastoidectomy and

long-term results of ossicular replacement with biovitroceramic

prosthesis (6,7) were used in the present study. We find

it important to be able to compare functional, anatomical and

reconstructive results for the same patients, using the same

surgical techniques and communicate long-term data. This

retrospective non-controlled study took into consideration the same

random selection of 200 long-term patients with both radical CWD

and modified radical mastoidectomy (MRM), performed over a 3-year

period. The techniques for both types of surgery are well-known and

described in literature (5,11,12).

The initial cohort was comprised of 209 patients, of which nine

died (eight of causes non-related to middle-ear disease, one

directly related to middle-ear disease after otogenic brain

abscess). The basic statistical criteria for the selection were

post-operative time span. Data analysis began in 2004, giving a

post-operative follow-up period of 8.12 years for the entire cohort

from the moment of surgery, and 7.86 years from the time of

complete epithelization of cavity, which allows us to consider it

as long-term evaluation. All patients were clinically evaluated

(microscope otoscopy), both before the surgery and after the

surgery as follows: i) Monthly for the first 6 months

post-operative; ii) every 2 months for the next 6 months (up to 1

year, corresponding to the moment of complete epithelization of

cavity for >80% of cases); iii) every 6 months in the 2nd year;

iv) every 8 months for the 3rd and 4th year post-op; and v) every

12-16 months for the 5th year post-op and also at any other

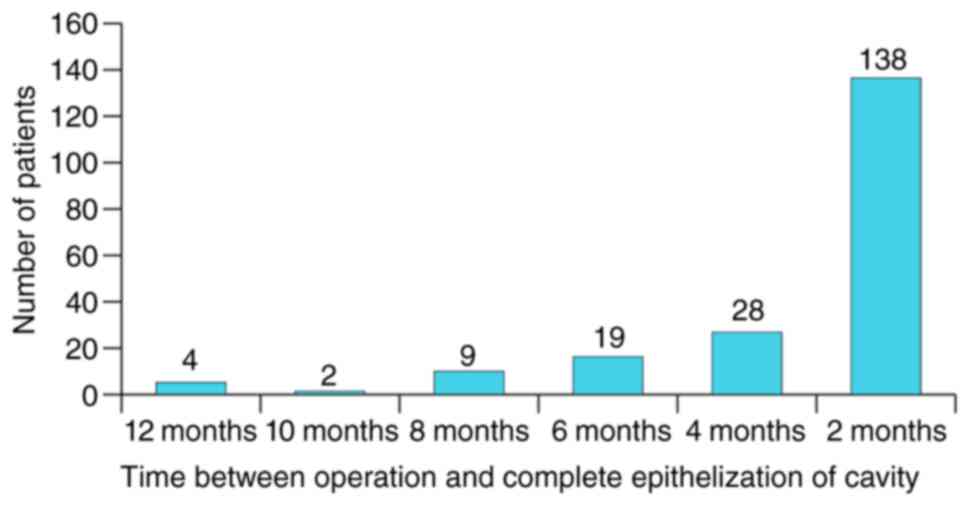

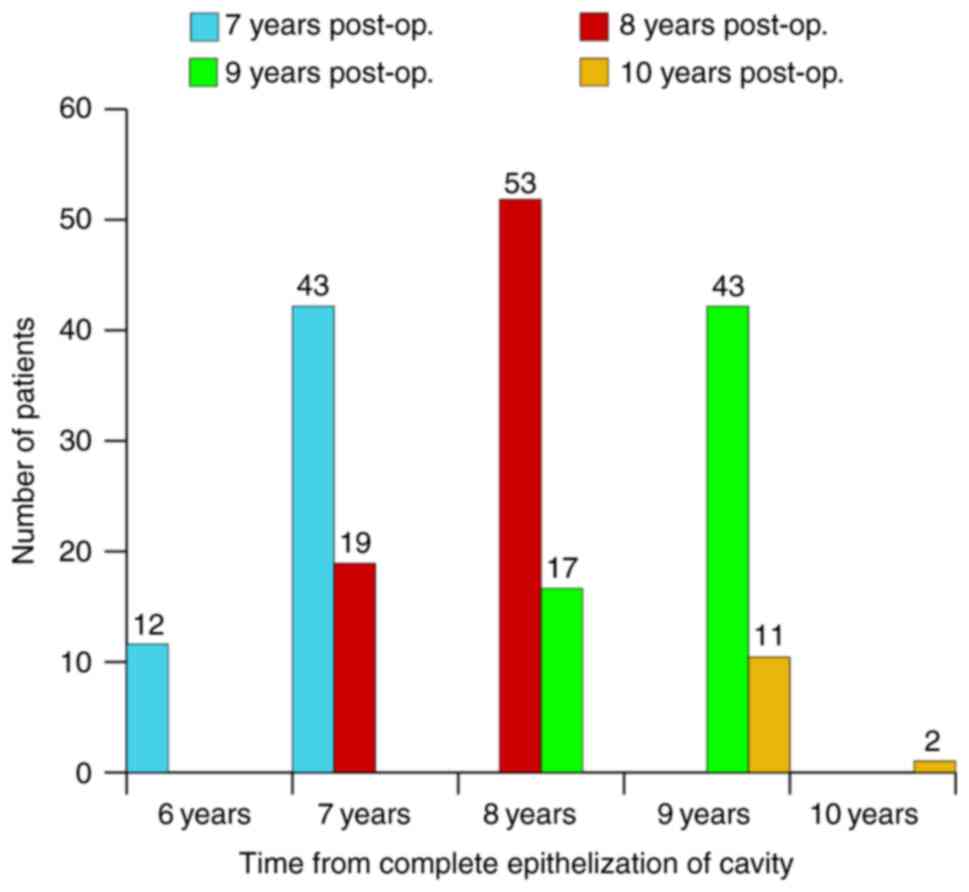

occurrent otorrhea episode. The follow-up of drainage results

started from the moment of complete epithelization of cavity for

each patient (Figs. 1 and 2).

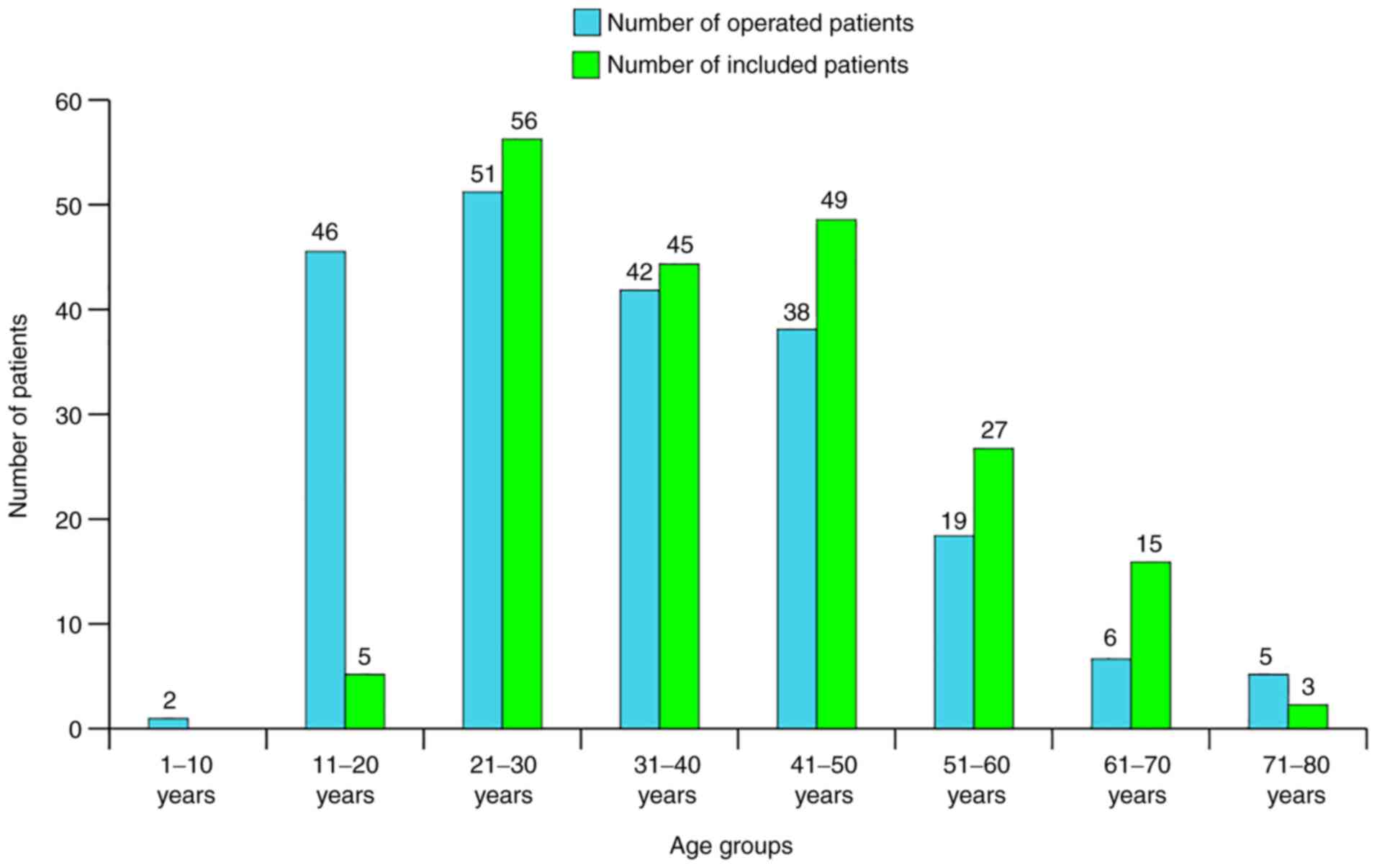

It is also noteworthy to point out the shift in the

age group distribution of patients that follows the long-term study

of a cohort (Fig. 3). Age was

defined at the time of surgery as: Physical time, duration of

evolution, aging (progressive degradation of function at different

rates), an unstoppable increase in damaged cells proportion,

increase of degree or intensity of disease, rise of hearing

thresholds-all of these being included in a formalized model

(physical-mathematical model).

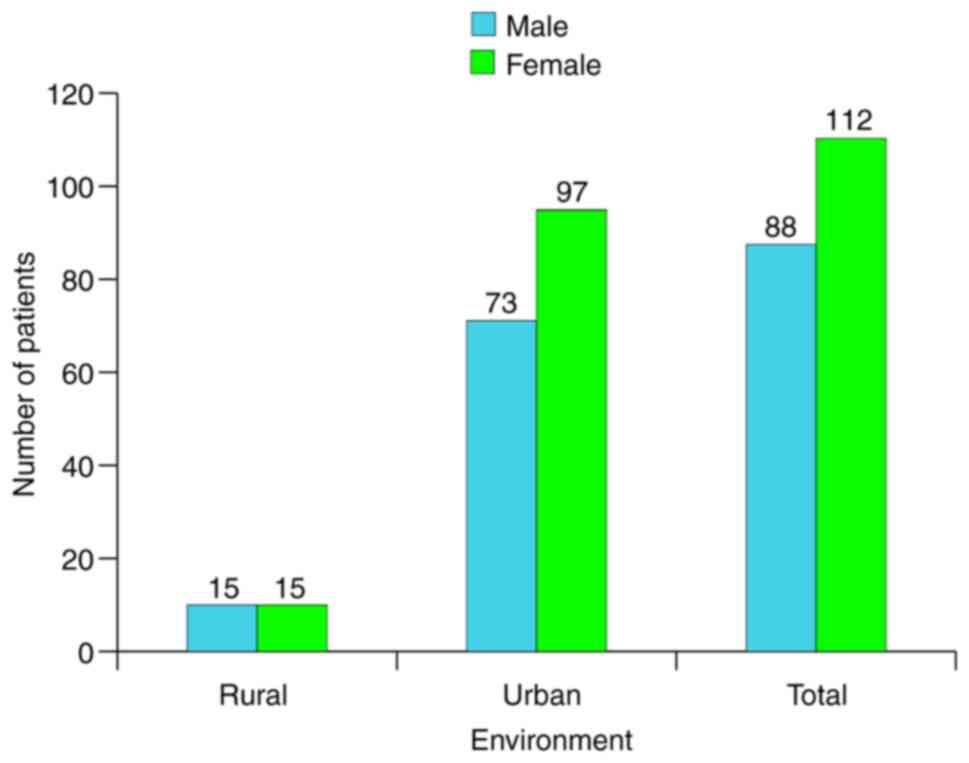

The distribution of sex and environment is presented

in absolute frequencies in Fig.

4.

Paraclinical diagnosis

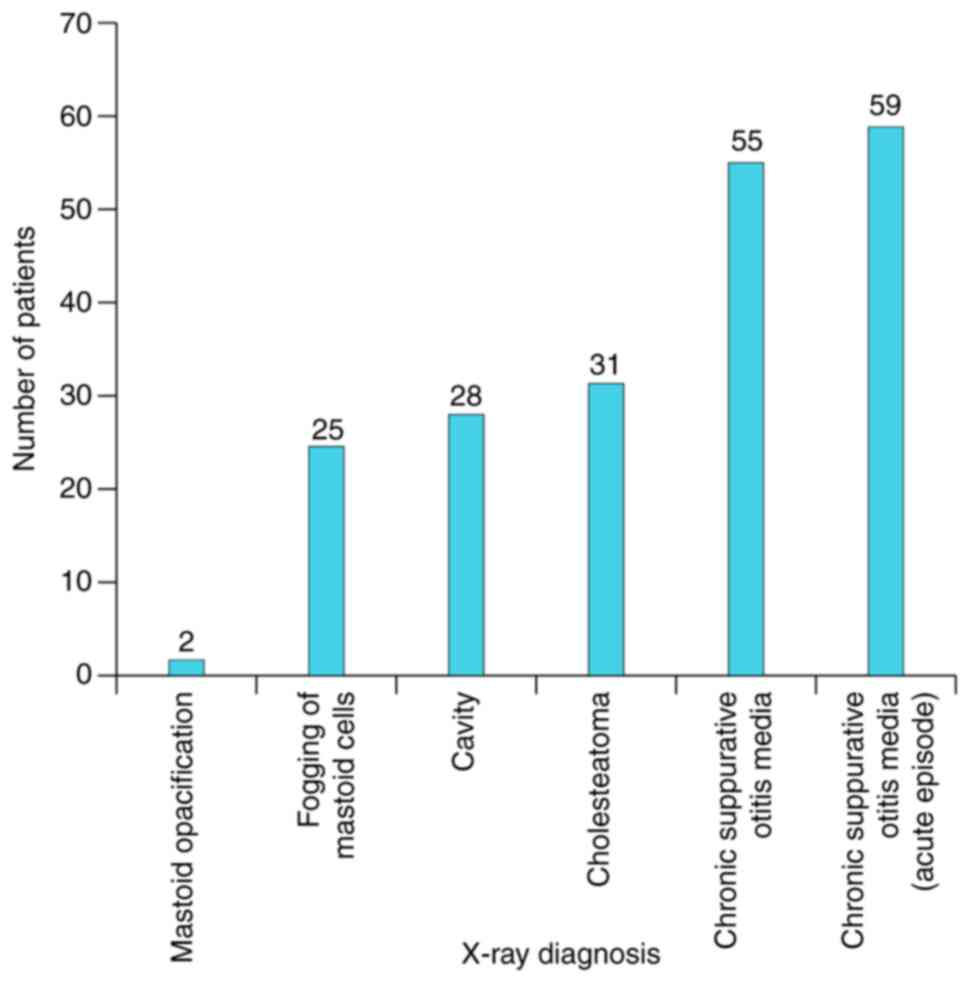

Radiological examination was also performed for all

patients (bilateral X-ray in Schuller's view) with high degree of

sensitivity and specificity for mastoid diagnosis. A total of 55%

(n=31) of the cholesteatoma cases and 61% (n=28) of previously

operated ears could be correctly diagnosed (Fig. 5).

The main goal of the present study was to define the

situations and factors that influence the drainage results of

mastoidectomy that could provide us with some type of anatomical

prognosis. Based on the selection criteria of the studied group and

by performing statistical analysis of the correlation of anatomic

results and statistically significant variables, pertinent

conclusions could be formulated regarding the drainage success rate

of mastoidectomy.

Statistical analysis

Although largely clinical, this study also included

some statistical analysis, including creating Microsoft Excel

databases and attributing codes to facilitate data analysis using

Excel (Microsoft Corporation) and SPSS v15 (SPSS, Inc.). Factors

such as age of patient, presence of cholesteatoma, stage of disease

etc., were associated with the functional results of mastoidectomy.

Data were synthesized as percentage, mean values and standard

deviation. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. Parametric (unpaired Student's t-test) or

non-parametric (Mann-Whitney) tests were also applied.

Studied variables Pre-surgery

variables

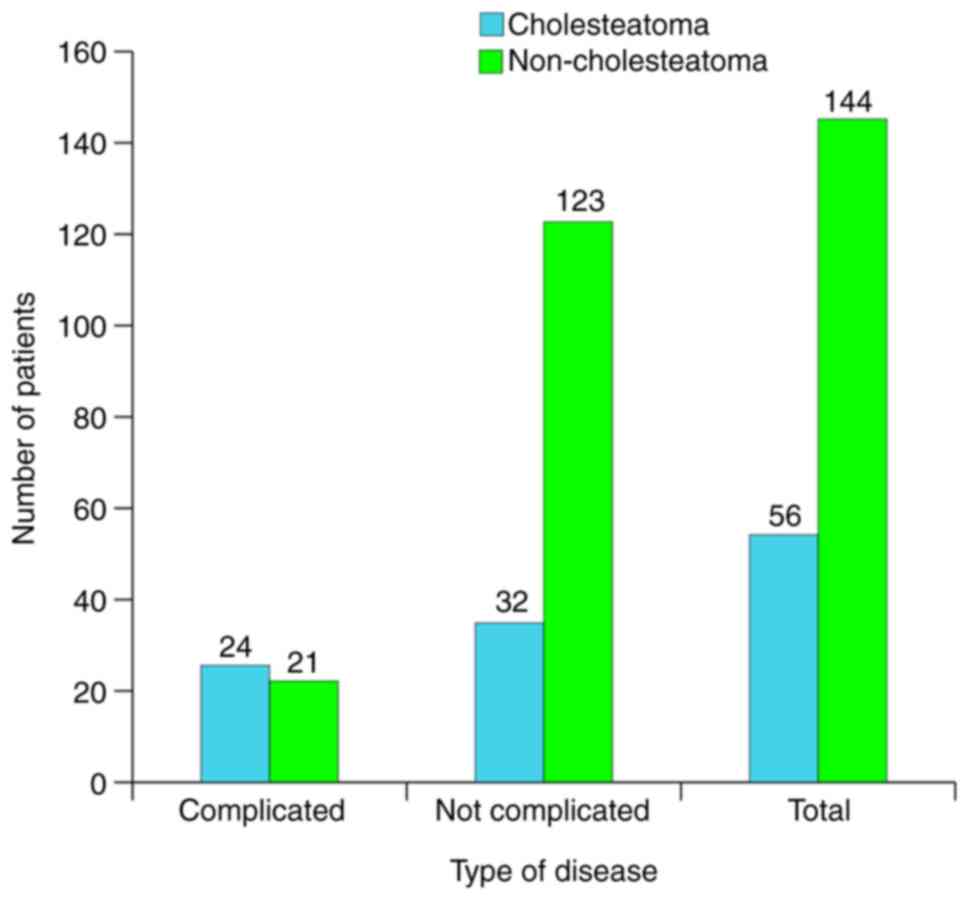

Pre-surgery variables were as follows: i) Age group,

0-10 years (n=1), 11-20 years (n=4), 21-30 years (n=56), 31-40

years (n=45), 41-50 years (n=49), 51-60 years (n=27), 61-70 years

(n=15) or 71-80 years (n=3); ii) clinical stage of disease,

complicated (n=45) or not complicated (n=155); iii) type of

disease, cholesteatoma (n=56) or non-cholesteatoma (n=144); and iv)

type of tympanic membrane perforation, marginal (n=75) or central

(n=125).

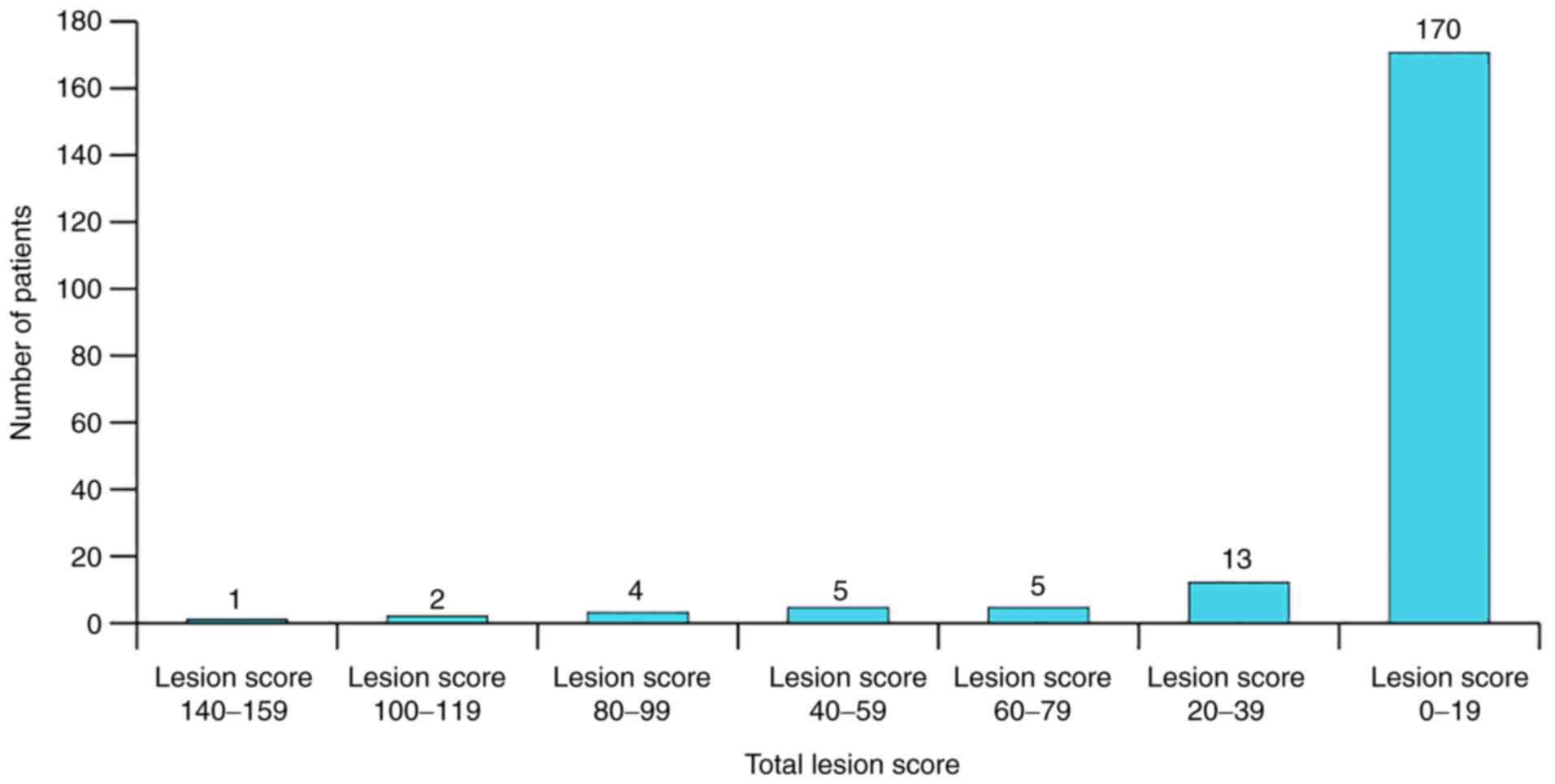

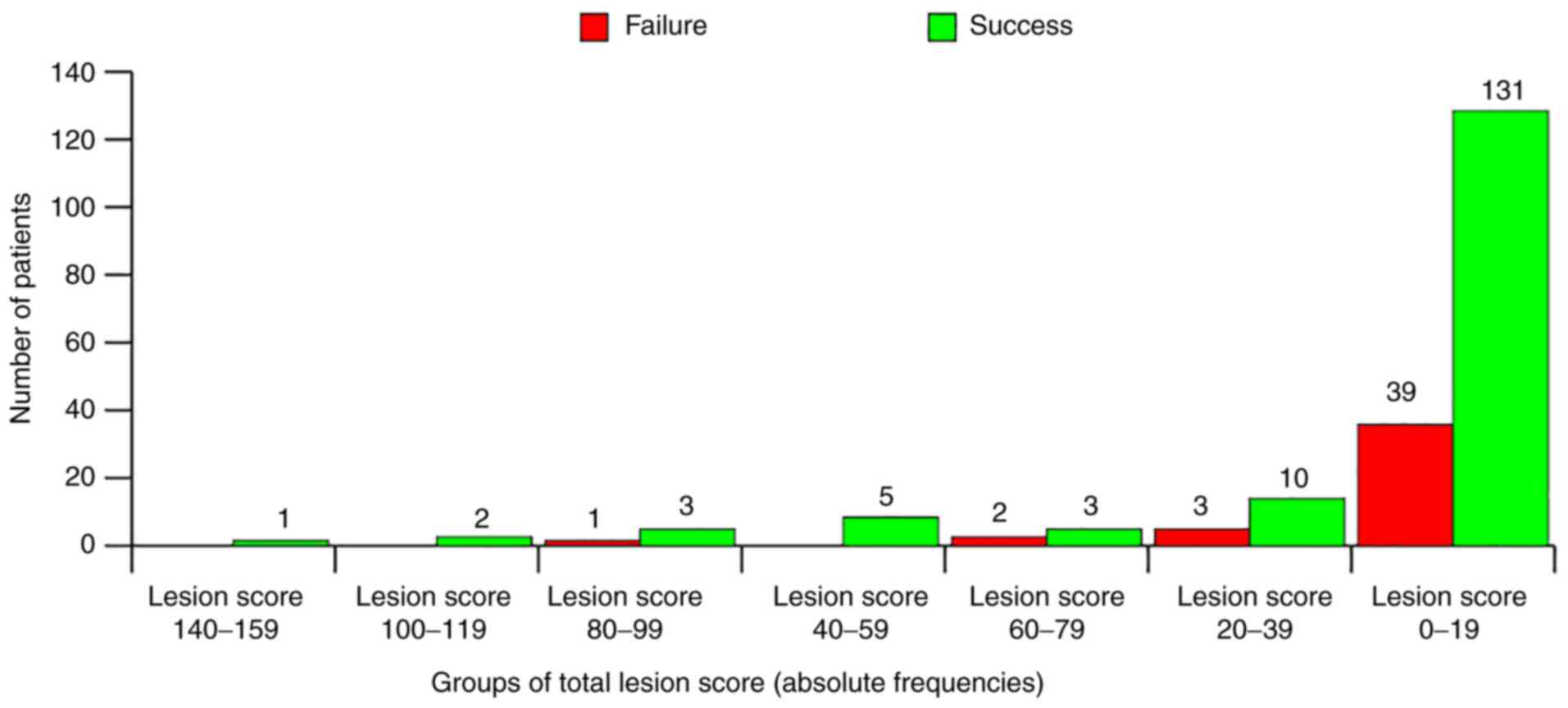

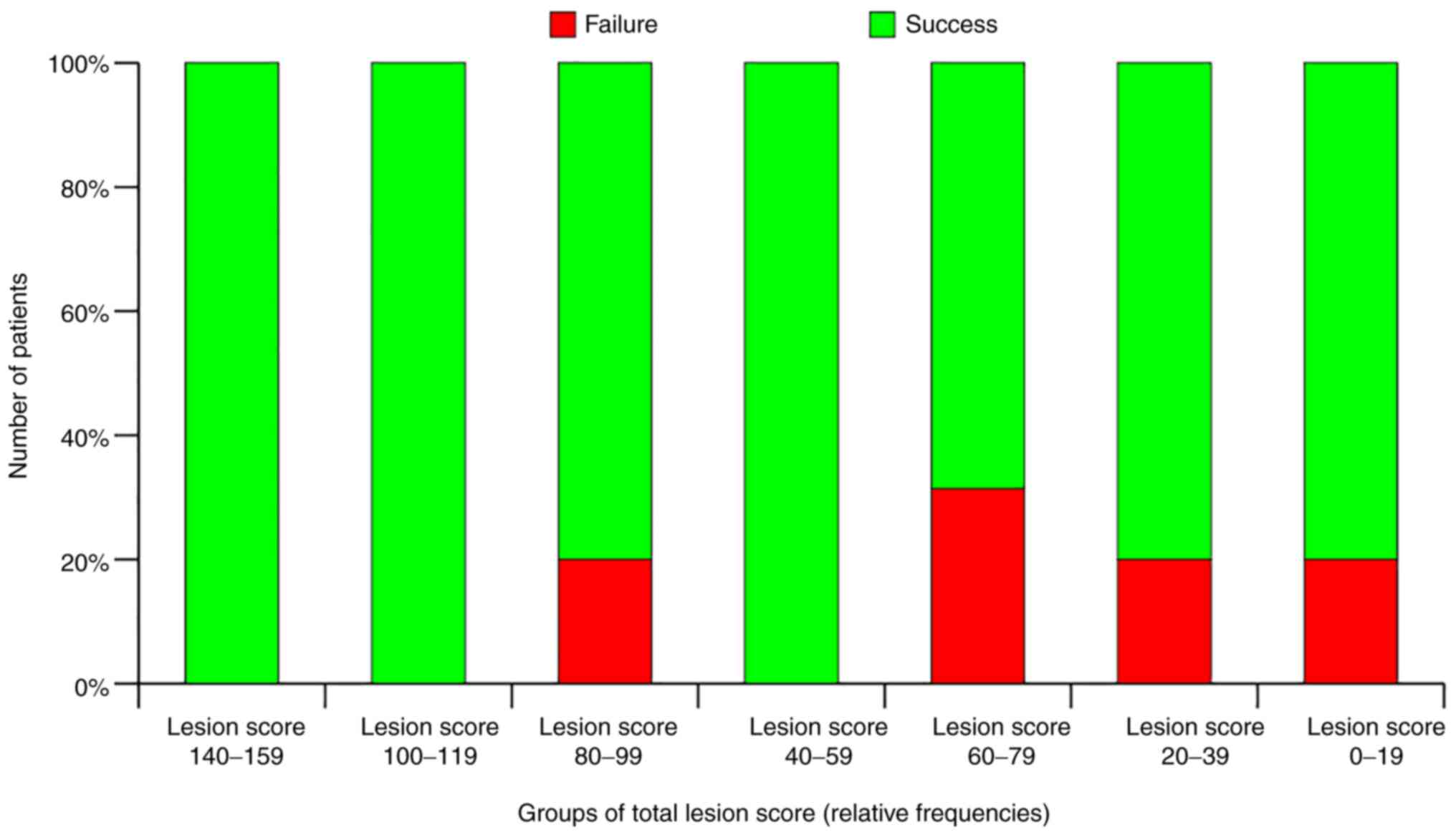

Intraoperative data

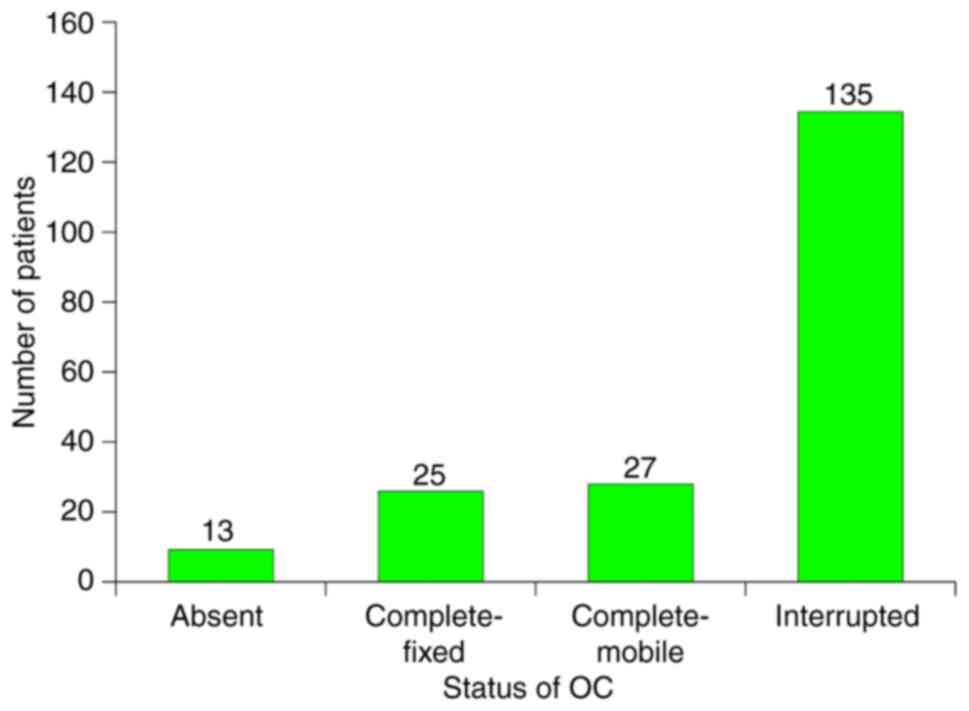

Intraoperative data variables were as follows: i)

Type of mastoidectomy, modified radical (n=125) or radical (n=75);

ii) OC status, absent (n=13), complete and mobile (n=27), complete

and fixed (n=25), or interrupted (n=135); and iii) total lesion

score, 0-19 (n=170), 20-39 (n=13), 40-59 (n=5), 60-79 (n=5), 80-99

(n=4), 100-119 (n=2) or 140-159 (n=1).

Follow-up data

Follow-up data variables were as follows: i) Period

for complete epithelization of cavity, 2 months, 1 year, 2 years,

3-4 years or 8 years; ii) cavity self-cleansing, present or absent;

and iii) mastoidectomy result (drainage effect), failure or

success.

Results and Discussion

Successful mastoidectomy was defined in the present

study as the total absence of otorrhea episodes after total

epithelization of cavity and by failure of the presence of at least

one such episode. According to this definition the global drainage

results of mastoidectomy could be appreciated in this study. What

remained to be determined was to what extent could a completely and

permanently ‘dry ear’ be expected, and to identify the potential

parameters that most influenced the outcome.

Fig. 6 shows the

distribution of patients associated with the type of disease and

presence of complications. A total of 23% of patients (n=45)

presented with complications, but it was observed that

cholesteatoma cases had a 43% rate of complications, whilst

non-cholesteatoma cases had only 16%.

Complications of disease have predictive clinical

significance, which can be hierarchized (Table I). For obtaining an exact

quantitative lesion profile (including all other lesions except

those of the middle-ear mucosa, protympanum, tympanic cavity,

aditus to mastoid antrum, mastoid bone and petrous apex), points

were assigned (directly proportional to presumed gravity) for each

type of lesion (Table II). Vertigo

for instance was 3.36 times more significant than facial paralysis

and exteriorization and 4.56 times less significant than sudden

hearing loss (Tables I and II). It was considered most surprising

that the proportion of middle cranial fossa dehiscence was the

largest, and equally surprising was the proportion of Fallopian

canal dehiscence and its ratio to clinically documented facial

paralysis. This meant that patients could be categorized by this

lesion score, as seen in Fig.

7.

| Table IAbsolute and relative frequencies of

complications. |

Table I

Absolute and relative frequencies of

complications.

| Type of

complication | Number of

patientsa | Relative frequency,

% |

|---|

| MCF internal

cortical dehiscence | 39 | 20.0 |

|

Vertigob | 37 | 18.5 |

| Fallopian canal

dehiscence | 24 | 12.0 |

|

Deafnessb | 22 | 11.0 |

| Macroscopic

labyrinth lesion | 17 | 8.5 |

| Sigmoid cortical

dehiscence | 15 | 7.5 |

| PCF internal

cortical dehiscence | 14 | 7.0 |

| Fungal

pachymeningitis | 14 | 7.0 |

| Facial

paralysisb | 11 | 5.5 |

| Exteriorization of

suppurative processb | 11 | 5.5 |

| Lateral

semicircular canal fistula | 11 | 5.5 |

| Sudden hearing

lossb | 8 | 4.0 |

| Macroscopic facial

nerve lesion | 7 | 3.5 |

| Sigmoid sinus

phlebitis | 6 | 3.0 |

| Labyrinthine

fistula | 6 | 3.0 |

| Posterior

semicircular canal fistula | 5 | 2.5 |

| Extradural abscess

PCF | 3 | 1.5 |

| Extradural abscess

MCF | 2 | 1.0 |

| Acute

meningitis | 1 | 0.5 |

| Mandibular fossa

abscess (extra-articular) | 1 | 0.5 |

| Cerebellum

abscess | 1 | 0.5 |

| Table IILesion scores for complications. |

Table II

Lesion scores for complications.

| Intra-operative

lesion | Attributed

score | Ordinal of

scores |

|---|

| Cerebellum

abscess | 20 | 1 |

| Cerebral

abscess | 20 | 1 |

| Sigmoid sinus

thrombophlebitis | 15 | 2 |

| Extradural abscess

MCF | 10 | 3 |

| Extradural abscess

PCF | 10 | 3 |

| Acute

meningitis | 10 | 3 |

| Sigmoid sinus

periphlebitis | 10 | 3 |

| Total lysis of

stapes footplate | 9 | 4 |

| Lateral

semicircular canal fistula | 9 | 4 |

| Posterior

semicircular canal fistula | 9 | 4 |

| Labyrinthine

fistula | 9 | 4 |

| Macroscopic

labyrinth lesion | 9 | 4 |

| Fungal

pachymeningitis | 9 | 4 |

| Mandibular fossa

abscess (extra-articular) | 8 | 5 |

| MCF internal

cortical dehiscence | 8 | 5 |

| PCF internal

cortical dehiscence | 8 | 5 |

| Sigmoid cortical

dehiscence | 8 | 5 |

| Exteriorization of

suppurative processa | 8 | 5 |

| Fallopian canal

dehiscence | 7 | 6 |

| Macroscopic facial

nerve lesion | 7 | 6 |

| Facial

paralysisa | 7 | 6 |

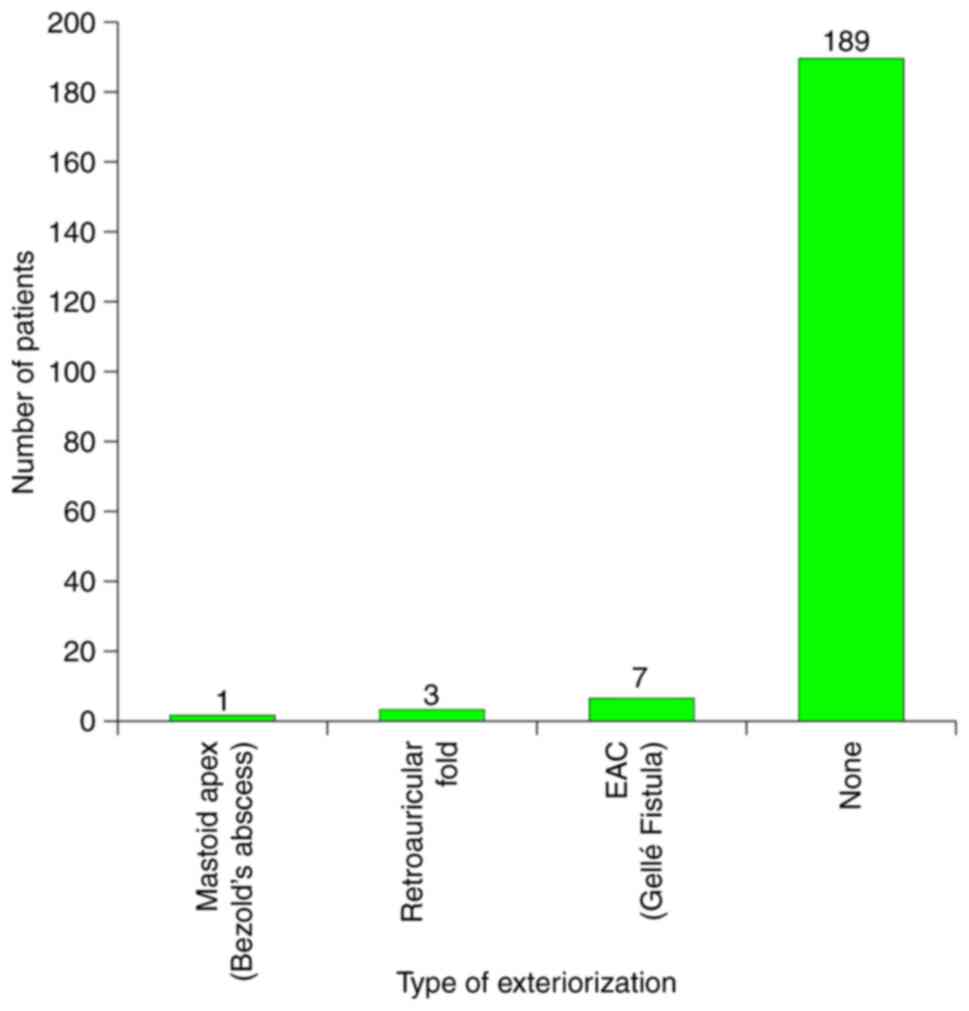

Another important parameter studied was the type of

exteriorization of the suppurative mastoid disease. The relative

frequency of these exteriorizations is presented in Fig. 8 and yielded noteworthy results.

Gellé's fistula (collapse of the posterosuperior meatal wall) had

the highest baring of 63% (n=7), followed by retroauricular fistula

27% (n=3), Bezold's abscess 9% (n=1).

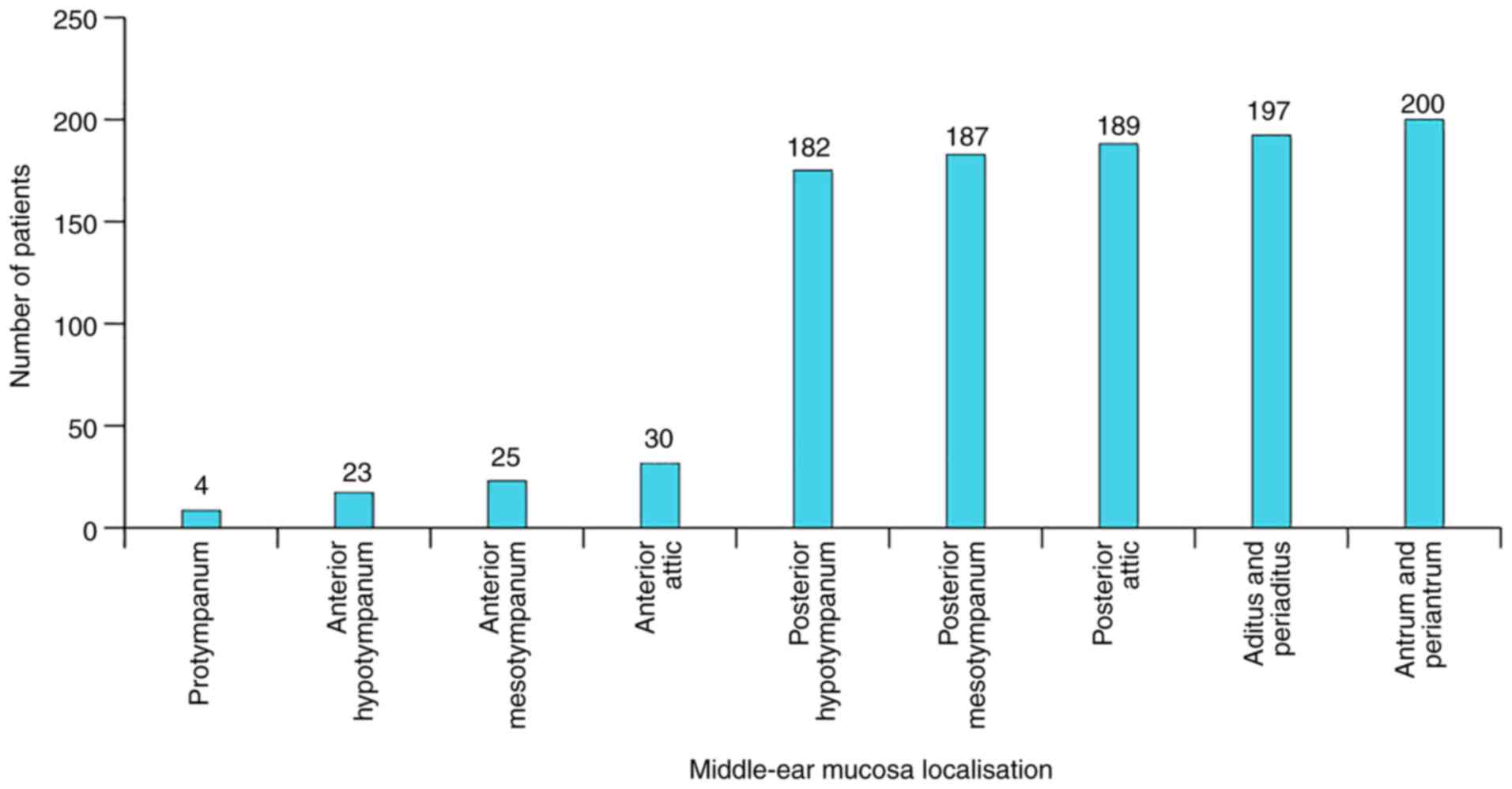

It is of note that the lesions of middle-ear mucosa

followed the frequency internal distribution law. By internal, it

is meant that the structure of the distribution is identical to the

topographic structure of middle-ear cavities. If these cavities are

considered as a co-axial suite, it could be observed that the

structure of absolute frequencies acted similarly to a non-linear

orderly series with an inflexion corresponding to the barrier

between the anterior and posterior half of the tympanic cavity

(Fig. 9).

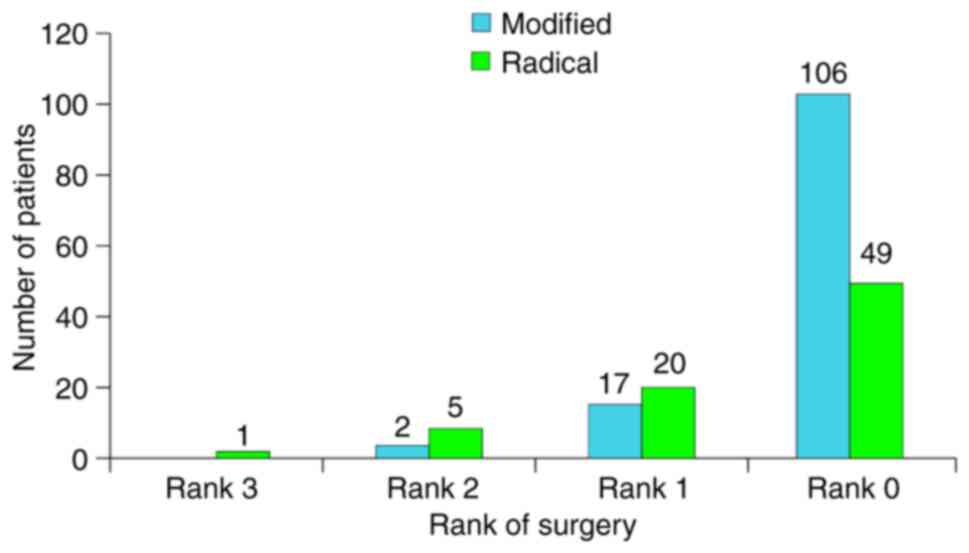

Distribution of patients according to the type and

rank of surgery is presented in Fig.

10. The rank of surgery became significant when it was

considered that the main study comparison criteria was time.

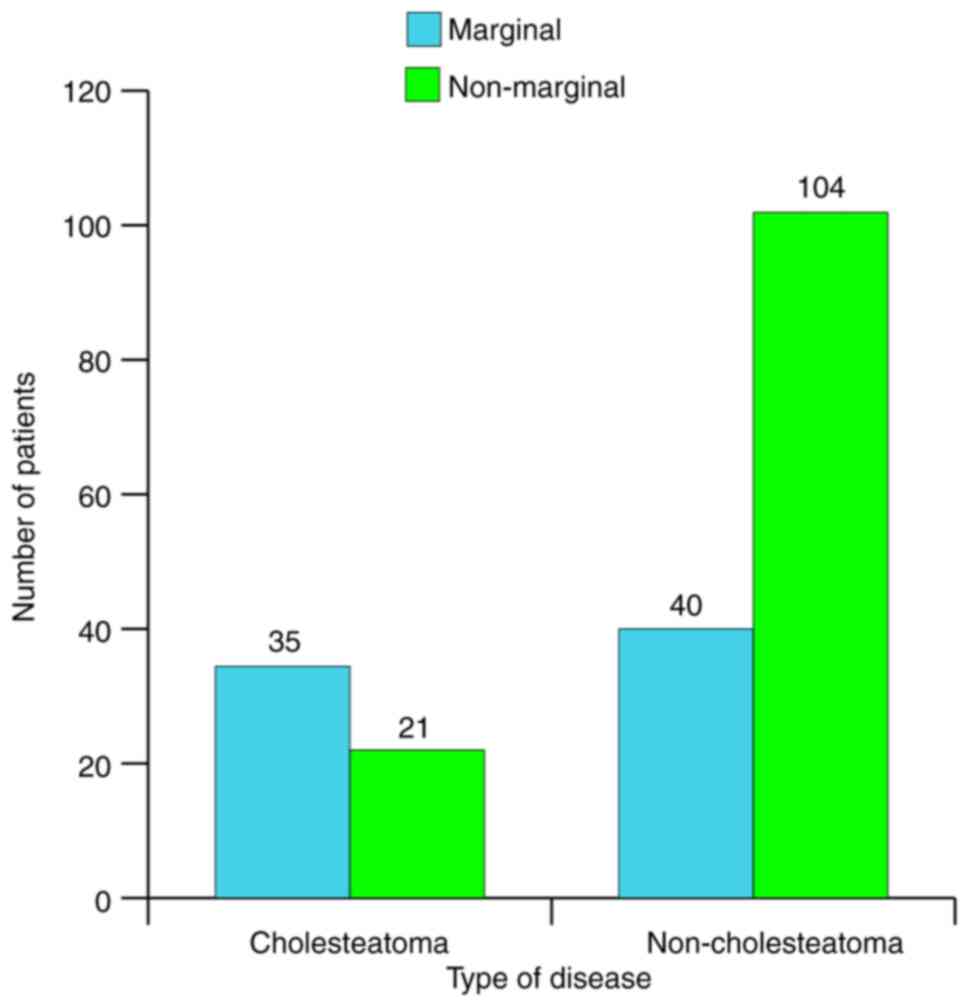

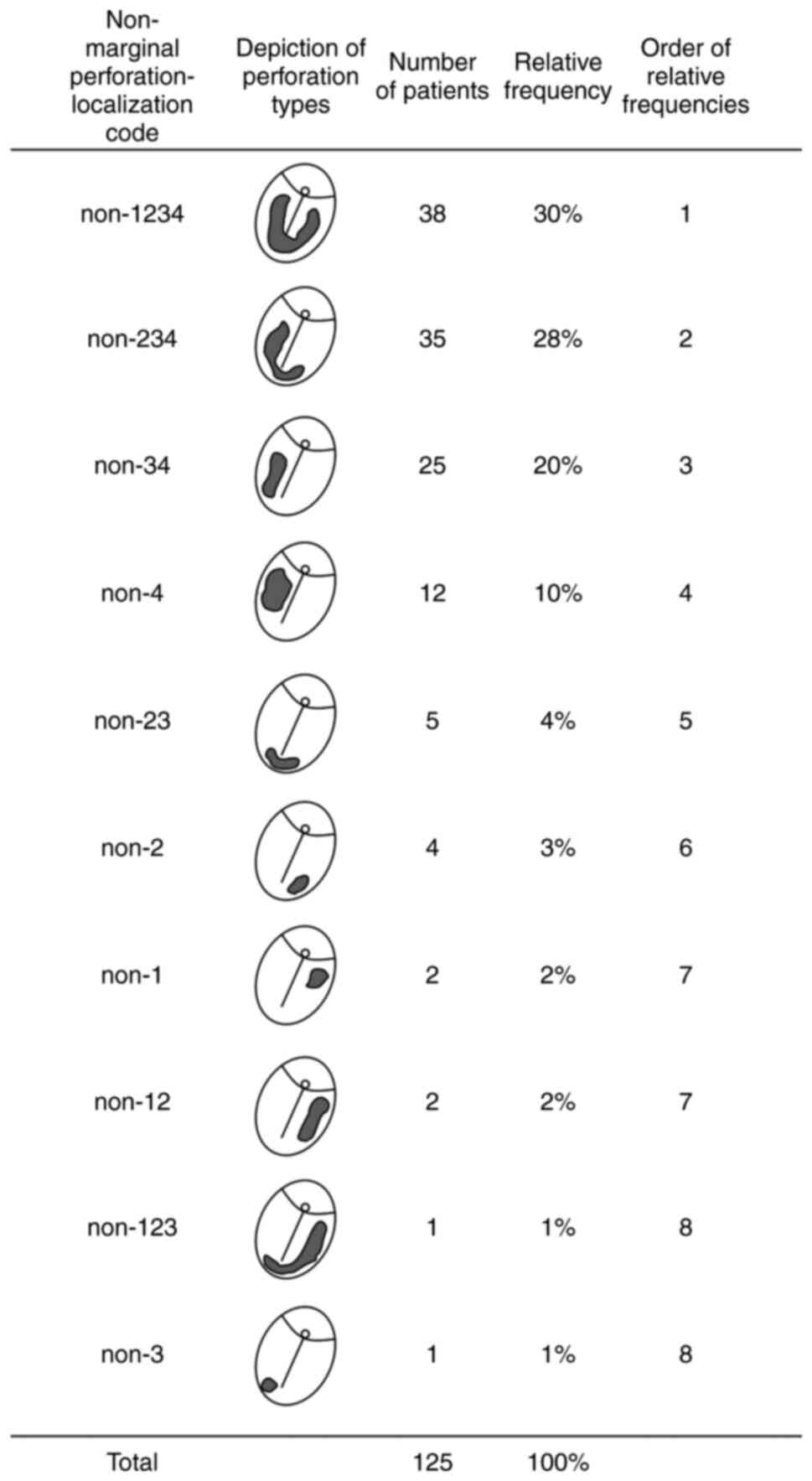

Fig. 11 presents

the distribution of patients according to type of disease and type

of tympanic membrane (TM) perforation. The relative frequency of

marginal perforation was 37.5% and that of cholesteatoma 28%.

Fig. 12 shows the frequency

distribution of marginal perforations with the highest frequency

for posterosuperior quadrant and posterior part of Shrapnell's

membrane and the lowest for anterosuperior localization. Fig. 13 addresses non-marginal

perforations with the highest frequency for subtotal perforations.

The specific weights of posterior localization for both types of

perforations were as follows: 76% for marginal and 88% for

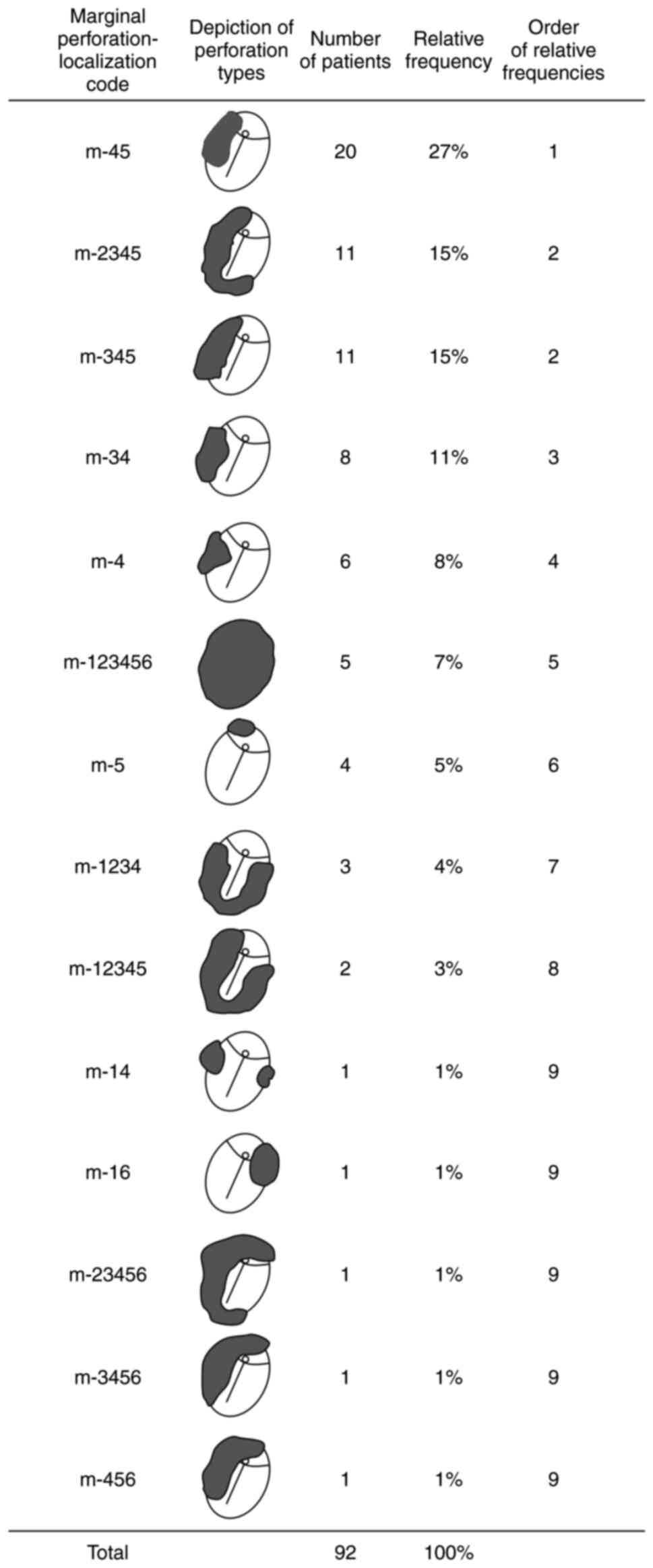

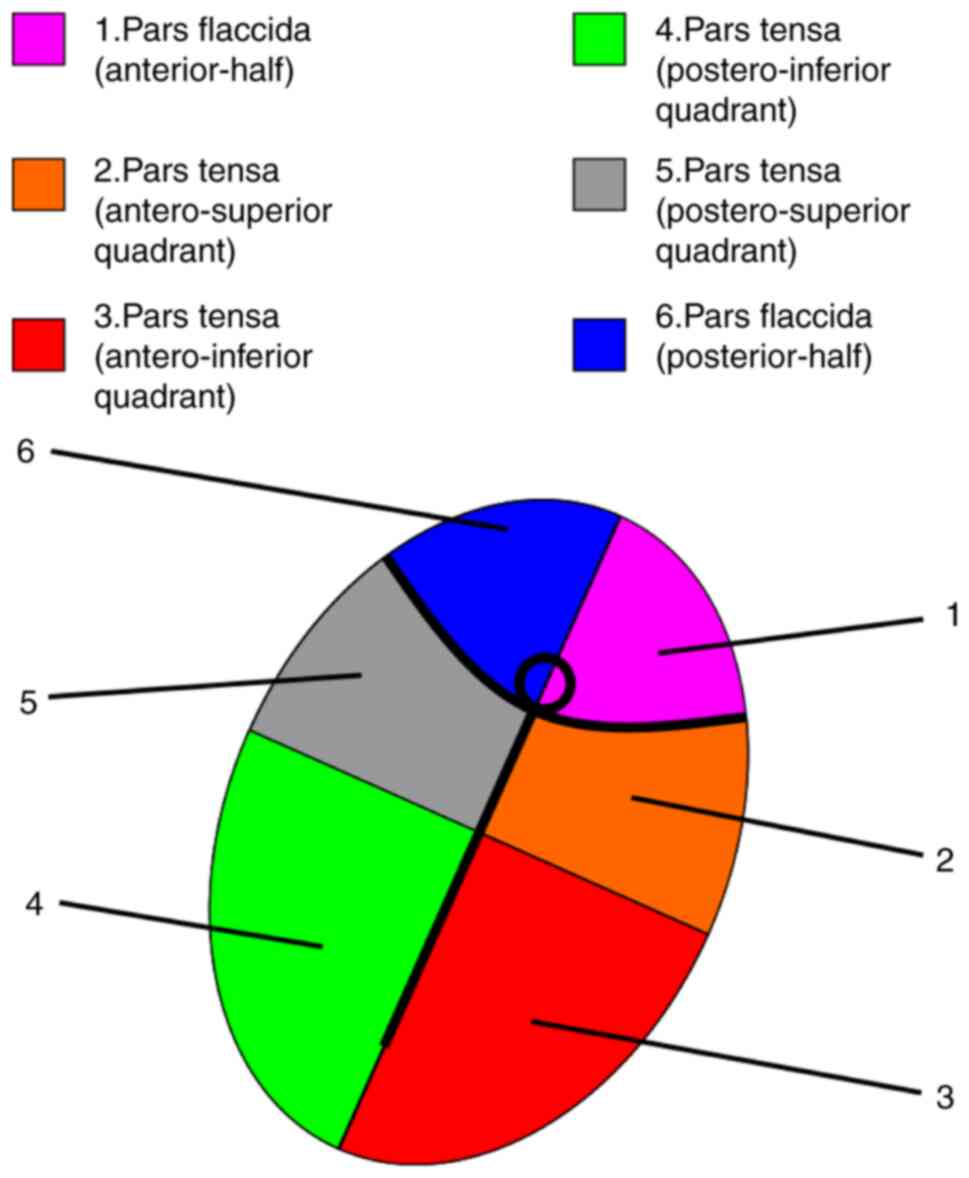

non-marginal. Fig. 14 represents

an explanation for the localization codes from Figs. 12 and 13. The letter ‘m’ stands for marginal

perforation, whilst ‘non’ stands for non-marginal. The numbers

refer to the area covered by the perforation and define the

specific quadrants of the pars tensa of the TM as well as the

halves of the pars flaccida (Shrapnell's membrane). As depicted,

some large perforations cover several neighbouring areas.

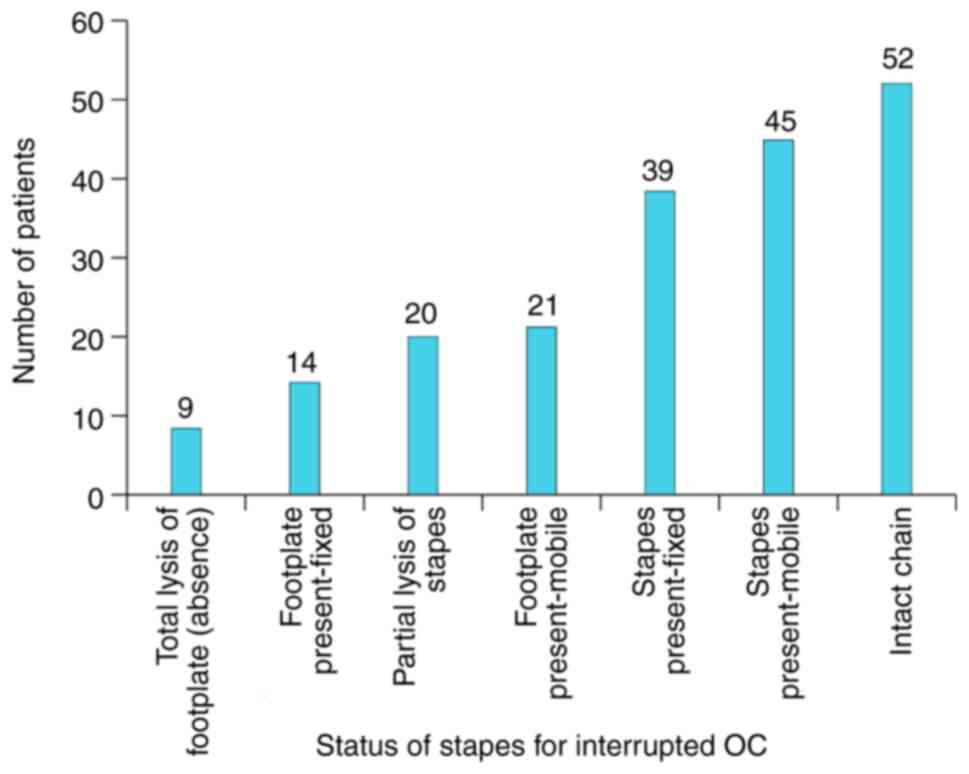

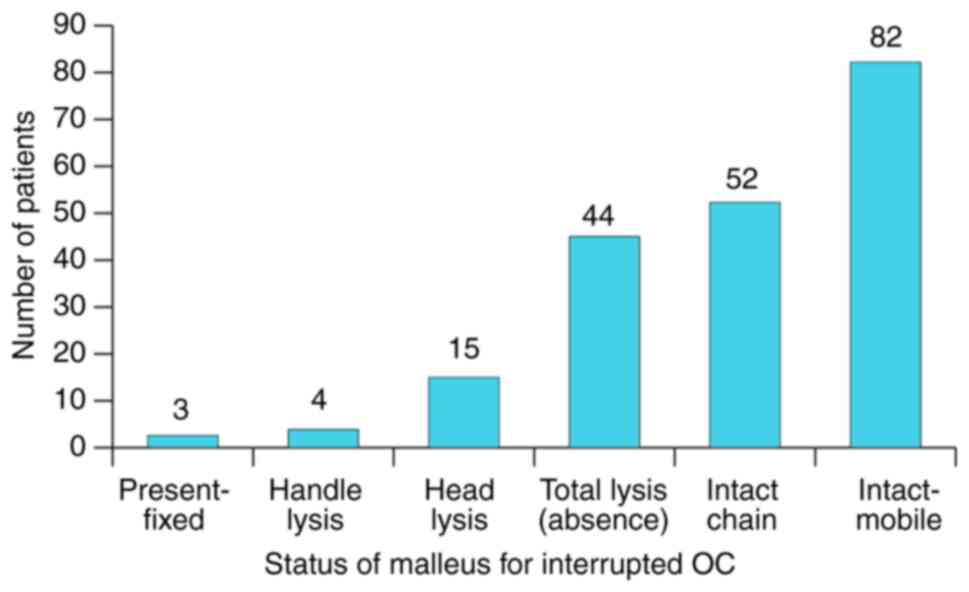

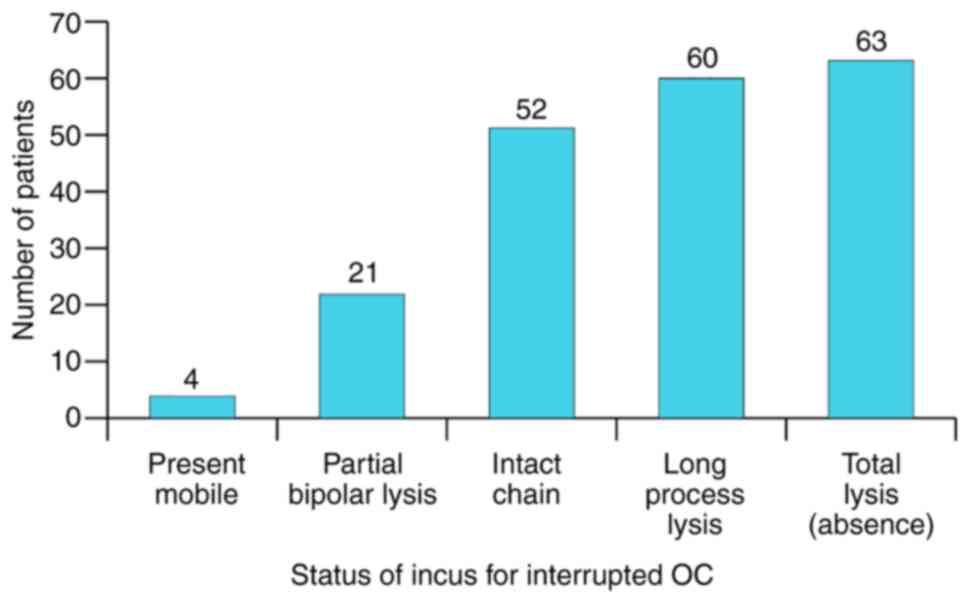

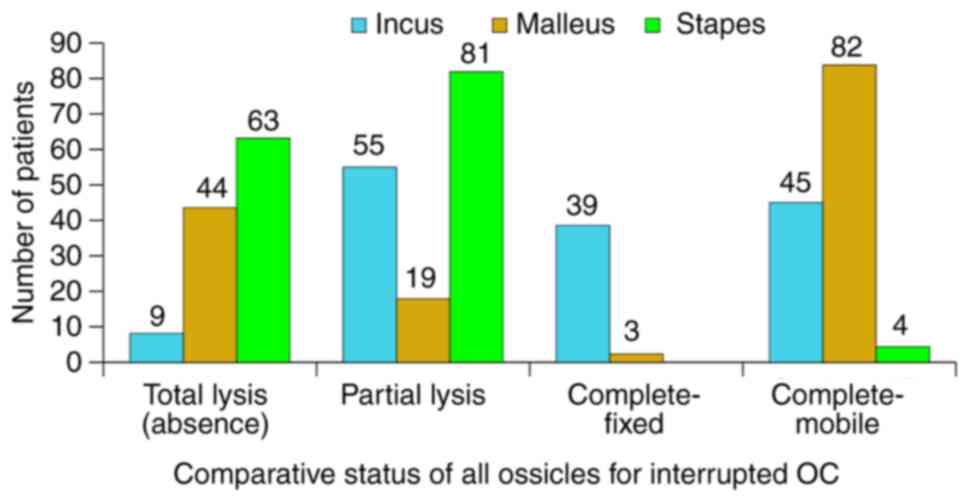

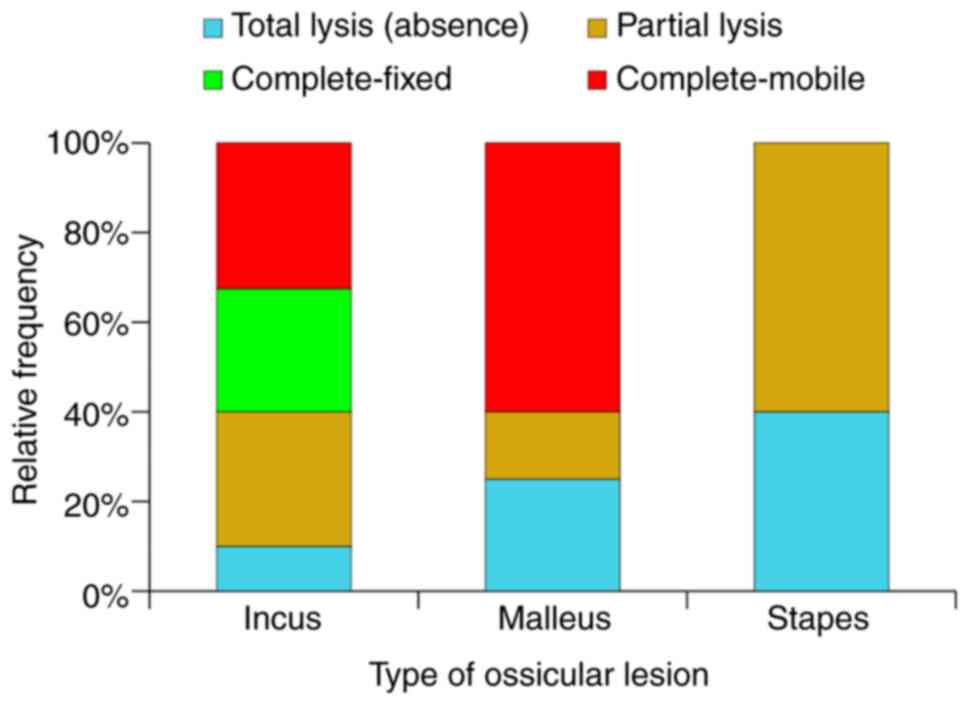

The state of the OC, as documented intra-op is

presented in Fig. 15. The specific

behaviour for each component of the OC in rapport to the

inflammatory status of the adjacent area was noted. Thus, the

stapes reacts by partial lysis and fixation to the oval window, the

malleus by total lysis, whilst the incus by osteolysis. The most

resistant towards total osteolysis was the stapes, followed by the

malleus. The incus was the most susceptible to this process. This

type of differentiated behaviour means that the total absence of

the OC (including stapes footplate) is relatively rare (7%),

fixation of a complete OC in almost double the cases (13%),

preserved complete and mobile OC in 14% and interrupted OC with the

highest frequency of 68%. This last situation represents the

characteristic response of the OC to chronic inflammatory disease

of the middle-ear (Fig. 16,

Fig. 17, Fig. 18, Fig.

19 and Fig. 20).

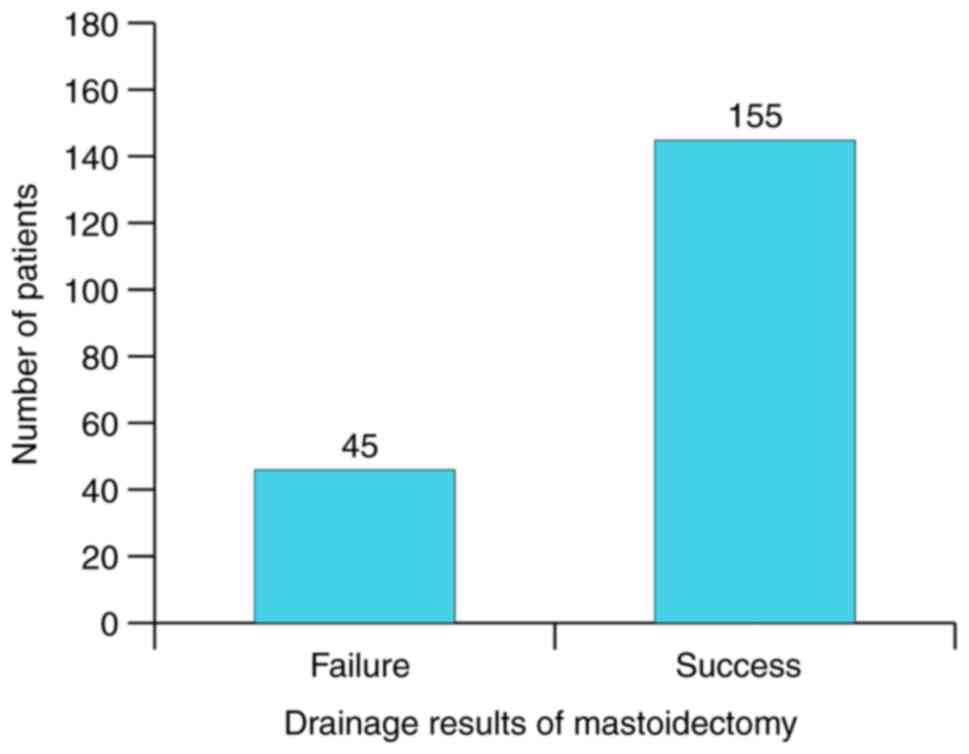

As far as success goes, the objective of the surgery

is to drain the inflammatory process and to create a new

self-cleaning external ear, a cavity with uniform walls that does

not allow cerumen deposits to form. Fig. 21 shows the global drainage results

of mastoidectomy in absolute frequencies with a success rate of

77.5%. Since completely self-cleaning ears are rather rare even in

healthy individuals, this objective was considered to be optional.

It would however instore quality of life (QoL) in the sense that

the patient could become independent from periodic visits to

clinical settings for cerumen removal. If the functional status of

the ear is also satisfactory it would bring total independence for

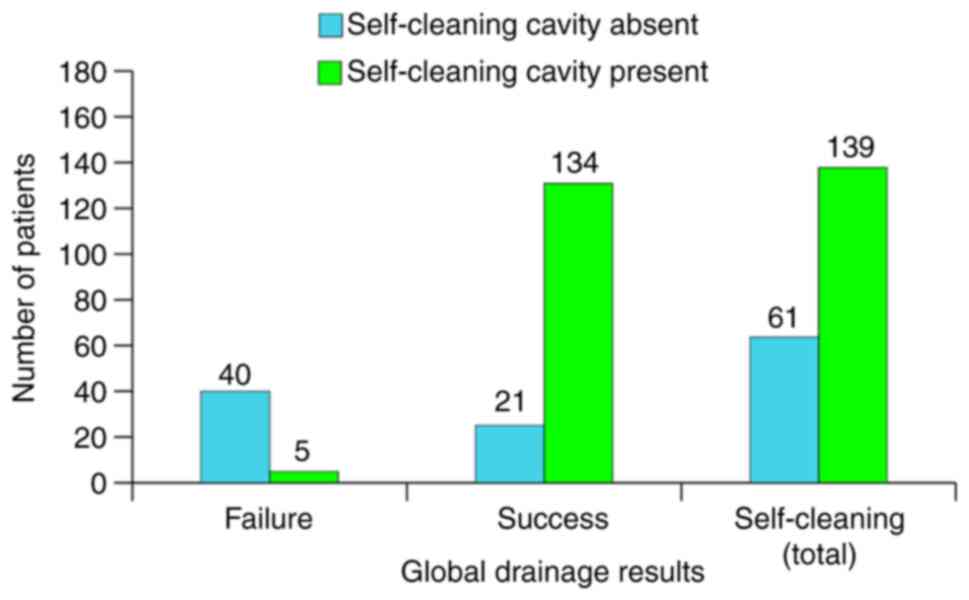

the patient, which is the purpose of surgery. Paradoxically,

self-cleaning was present in 11% of mastoidectomy failures

(Fig. 22) where it would be

expected to be completely absent. In the successful cases, there

was an 86% self-cleaning rate, which was lower than expected.

Overall, the global rate was 70%, which is probably the limit of

our future expectations on the subject. It can therefore be stated

that self-cleansing of a cavity is an intrinsic property of the

cavity and is governed by unclear internal laws, such as normal

keratosis and type of desquamation.

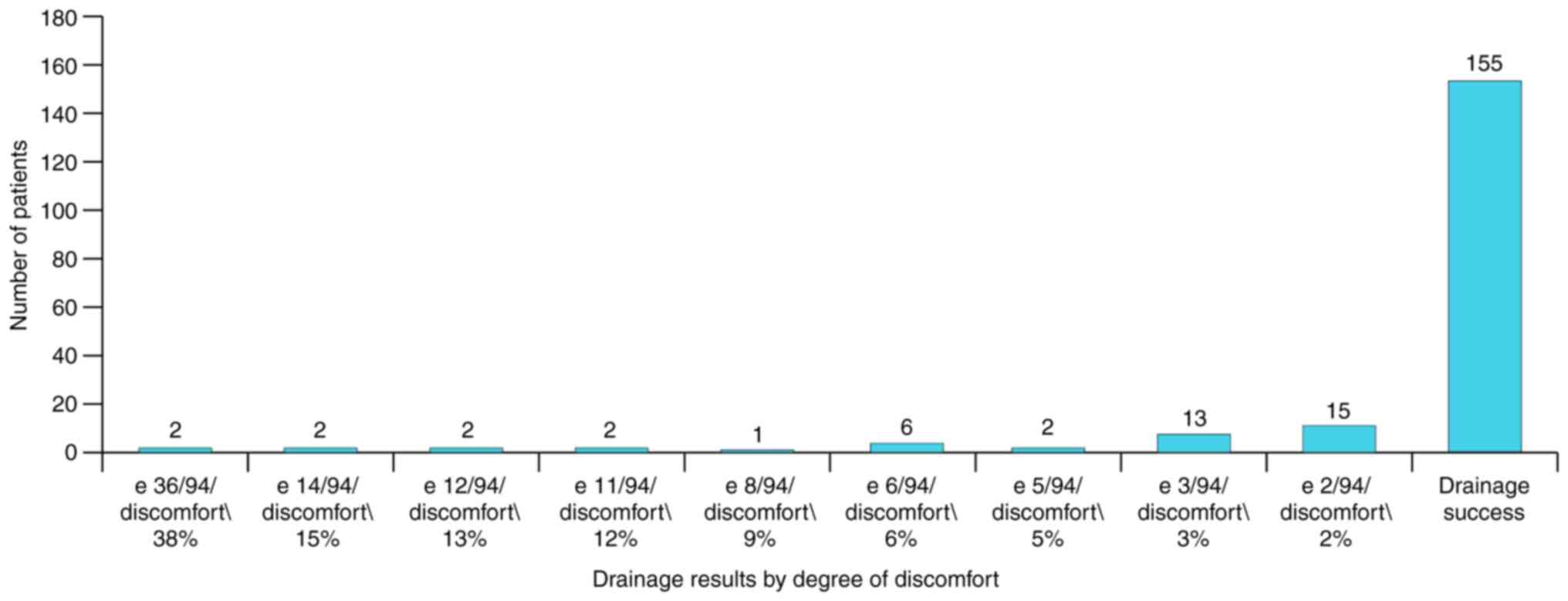

Failure of drainage requires further discussion

since it was defined by the appearance of one otorrhea episode in

7.86 years (one every 94 months), but the appearance of 36 episodes

(one every 3 months) also represented failure. In principle, both

situations are failures, but the specific situation is different

for each case, especially from the patient's point of view. This

meant that we had to find a way to differentiate failure and for

this purpose an arbitrary scale was created to quantify

comfort/discomfort of patient related to the number of otorrhea

episodes. Maximum discomfort (100% drainage failure) was considered

as monthly otorrhea episodes for the entire 7.86 years (94 months =

94 episodes). This meant that the most notable failure, 36 episodes

in 7.86 years (one episode every 3 months) corresponded to a 38%

discomfort rate and the smallest failure of two episodes in 7.86

years (one every 48 months) to a 2% discomfort rate. Fig. 23 shows the success of drainage

corresponding to each comfort/discomfort group in absolute

frequencies. Out of 45 patients with drainage failure two had the

highest discomfort score of 38% and most of them (n=15) had the

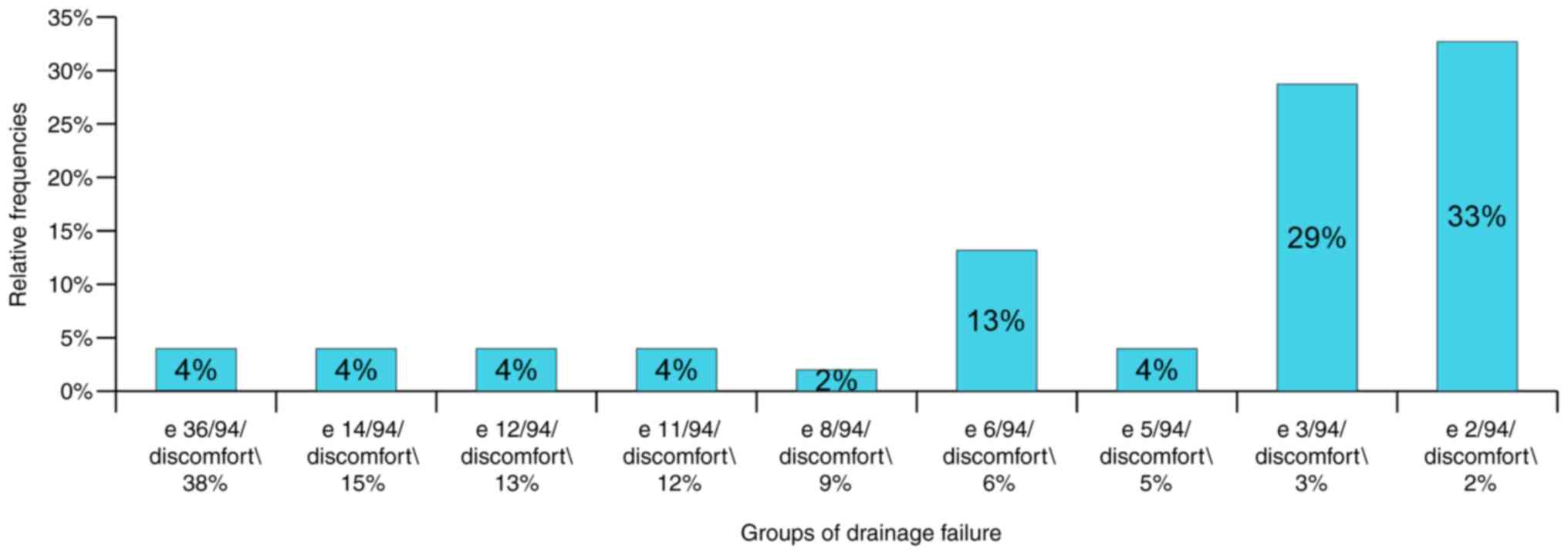

lowest score of 2%. Fig. 24

presents the same scores for failure patients; it was found that

81% of them had a discomfort score of up to 10%.

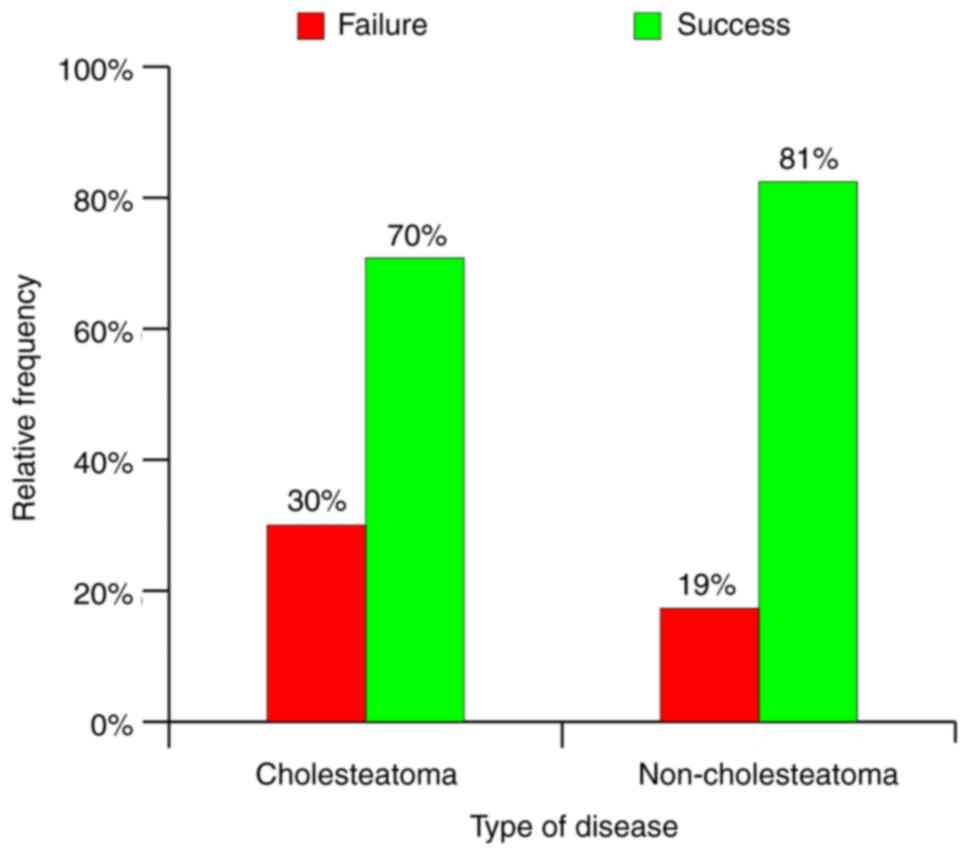

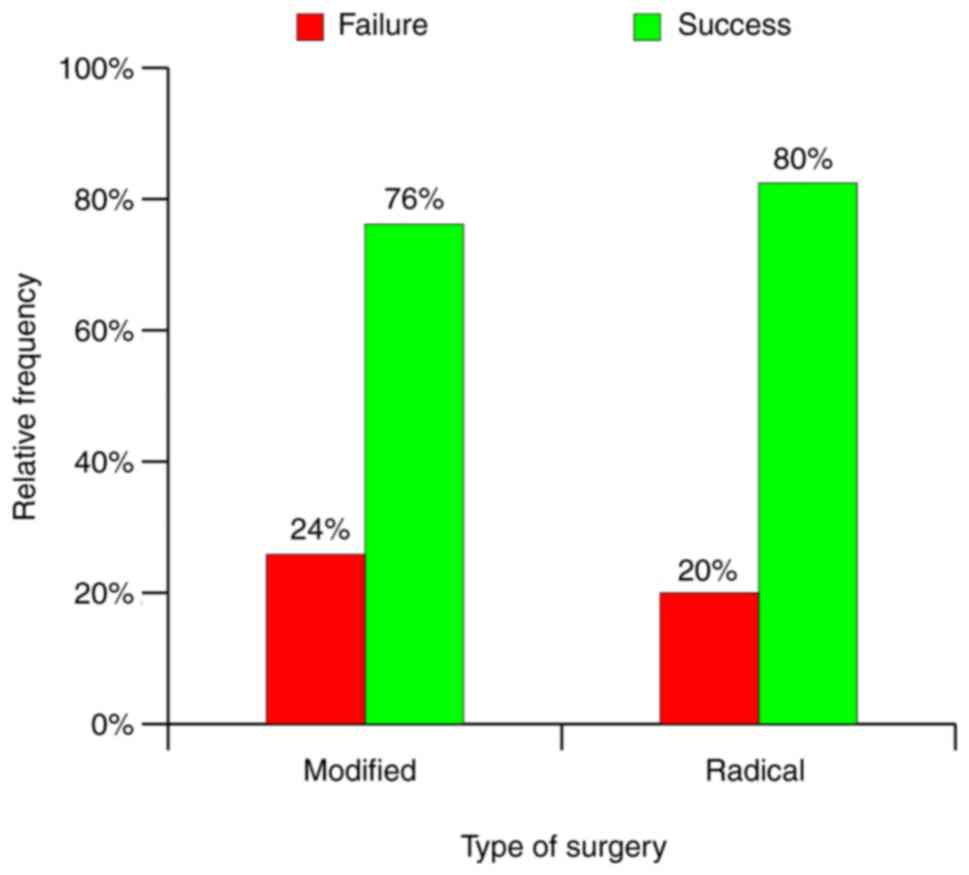

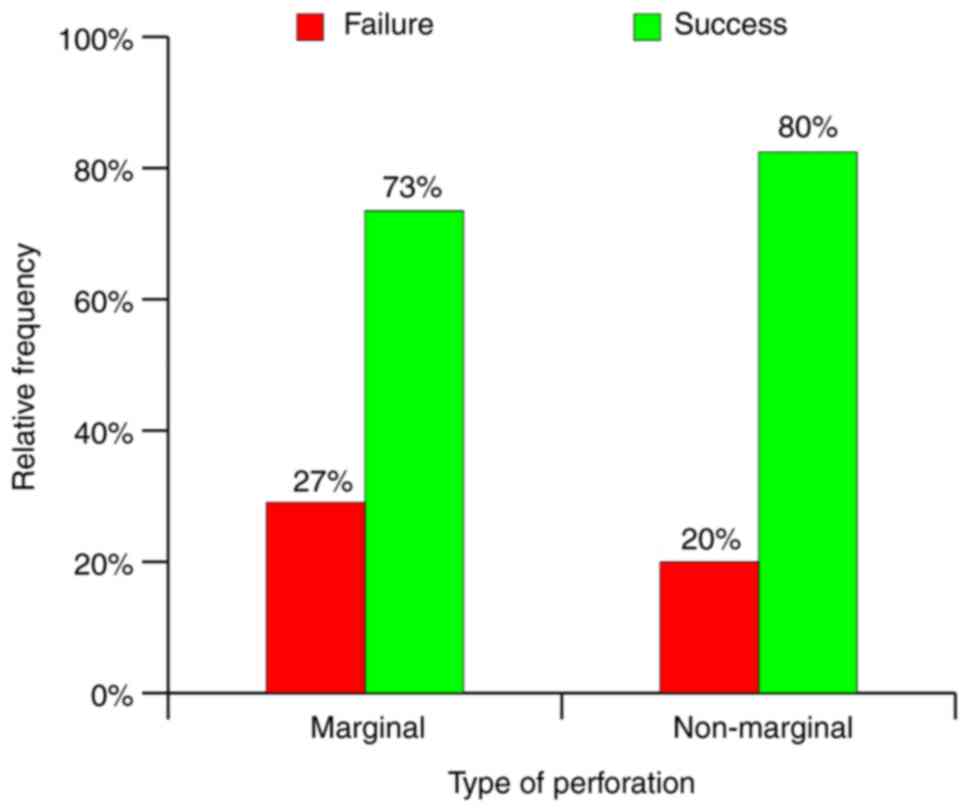

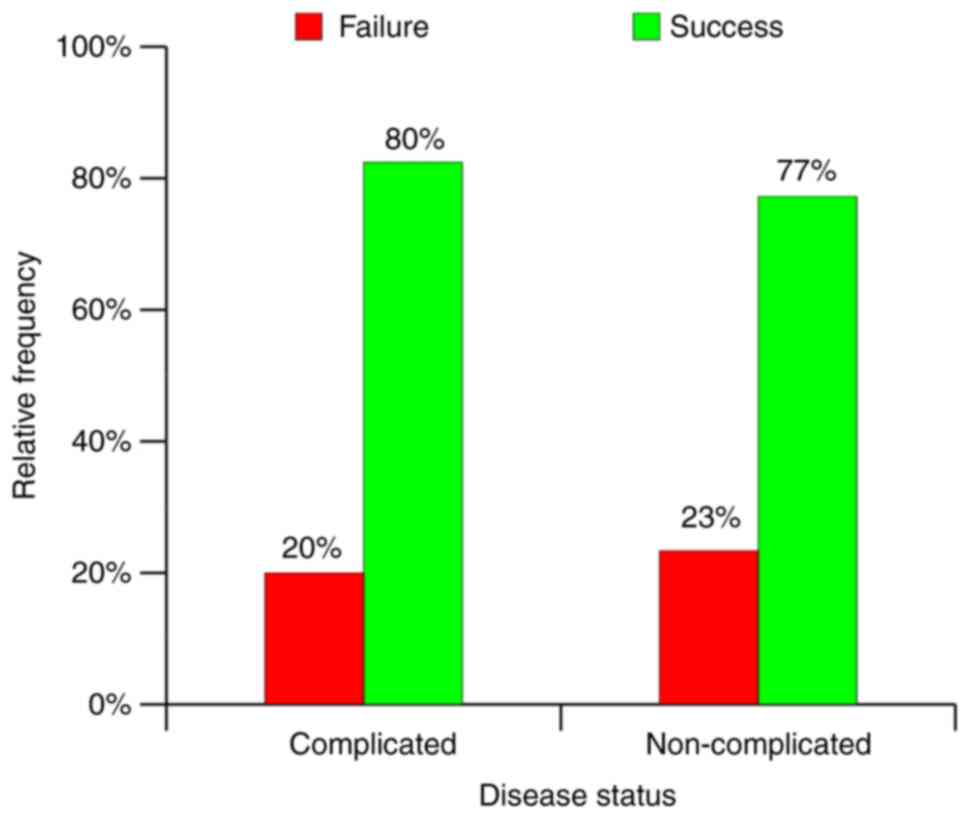

Although in our previous articles concerning

functional results of mastoidectomy for the same cohort of patients

(11,12), we encountered several factors that

influenced results, in the present study only three seemed to have

the expected influence on drainage results, including type of

disease, type of perforation and type of surgery. Presence of

cholesteatoma increased the rate of drainage success by 11%,

marginal perforation by 7% and MRM by 4% (Fig. 25, Fig.

26 and Fig. 27). By comparing

the global rates of success and/or failure to variables proven to

modify as expected the said rates, an influence of maximum 8% of

cholesteatoma presence was defined. Statistically the value was

significant, but a definitive conclusion cannot be stated in the

present study. Some of the variables, such as presence of

complications, clinical stage and total lesion score, yielded

paradoxical results and did not allow us to draw an applicable

conclusion concerning the involvement of these factors in the

evolution of long-term drainage results (Fig. 28, Fig.

29 and Fig. 30).

The most useful conclusion came from the

distribution of middle-ear mucosa lesions (Fig. 9). If the series of data are

concatenated from the chart, we obtain 10% for lesions localized

anterior and 90% posterior to a frontal conventionally drawn

geometric plan running through the middle of the tympanic cavity,

dividing the axial and coaxial spaces of the ME (by ME we

understand the sum of protympanum and the cells around it, tympanic

cavity with corresponding cells, aditus and antrum with peri-adital

cells, mastoid antrum with peri-antral cells) into two

segments-anterior and posterior to the defined geometric plan. The

concatenation involved calculating the mean value and adjusting it

to 100% of the newly obtained structure. By comparing these

empirical series to the theoretic series of endo-temporal cavity

distribution with variable geometry of the ME similar structures

were obtained: i) Peri-protympanum, 7%; ii) peri-tympanic cavity,

18%; iii) peri-aditus, 10%; and iv) peri-antrum, 65%.

Considering this series, in accordance with the

geometrical plane defined above, the following distribution was

obtained: i) Peri-protympanum, 7%; ii) peri-tympanic

cavity-anterior of plane, 9%; conventional frontal plane; iii)

peri-tympanic cavity-posterior of plane, 9%; iv) peri-aditus, 10%;

and v) peri-antrum, 65%.

This in turn led to the new theoretical series: i)

Protympanum 7%; ii) peri-tympanic cavity-anterior of plane, 9=16%;

conventional frontal plane; iii) peri-tympanic cavity-posterior of

plane 9% + peri-aditus 10% + peri-antrum 65 = 84%.

The empirical series in turn (Fig. 9) became: peri-protympanum +

peri-tympanic cavity = 10%; conventional frontal plane;

peri-tympanic cavity-posterior of plane + peri-aditus + peri-antrum

= 90%.

The two series (theoretical and experimental)

obviously had similar structures. They were compared with the

drainage results of 78% success and 22% failure. To do so it was

stated that, theoretically, radical mastoidectomy completely

cleaned the peri-antrum cells (65% of total), almost all of the

peri-aditus cells (10% of total), less than half of the

peri-tympanic cavity cells (18%) and none of the peri-protympanum

cells (7%). Practically the surgery cleaned much less than the

theoretically predicted ratio: Peri-antrum=0.65x (x→1), peri-aditus

= 0.1y (y→1), peri-tympanic cavity = 0.18z (z→0.5) and

peri-protympanum = 0.07w (w→0). The maximum obtainable value for

the sum 0.65x + 0.1y + 0.18z + 0.07w was 84%. This meant that

practically and ideally, a maximum of 84% could be cleaned out of

the mastoid and petrous cells. The remaining 16% may contain

irreversible lesions. The results of almost 78% were congruent to

this theory.

From a practical point of view, no surgeon should

expect to drain the entire endo-temporal structure since this type

of exercise is rarely realized in experiments or dissections. This

means that we must admit that some of the pneumatic cavities cannot

be surgically approached, dividing the mastoid bone into surgical

cavities and non-surgical cavities. The rate of success of

mastoidectomy is entirely dependent on the chance that all lesions

will be in a surgical area and this chance is a function of the

proportion of pneumatic cells for each of the mentioned areas.

Simplifying the process, it was stated in the present study that

the proportion of surgical cavities was 75% (antrum, aditus and

adjacent cells) and non-surgical cavities was 25% (tympanic cavity,

protympanum and adjacent cells). Failure should, in turn, be

discussed as medical research can occasionally require a high

degree of abstraction (13) and

failure itself is not an unequivocal clinical fact and it requires

divisions and nuances as we have previously stated (Figs. 23 and 24). The cause of failure is obvious

whilst the cause of its division is the normal law of probability

distribution that guides the division of remnant lesions in the

non-surgical cells. In other words, the more remnant lesions in

non-surgical cells, the higher the failure rate and intensity

(higher number of otorrhea episodes, lower patient comfort).

In comparison, Mukherjee et al (2) proposed a study on 133 patients with

MRM and published long-term functional and anatomical results.

Their criteria included the notion of waterproof ears (no otorrhea

after exposure to water) and the study reported 95% (n=126) as such

(2). The anatomical status of the

stapes and the degree of ventilation within the middle-ear are also

considered proof of a successful operation, in accordance with the

conclusions of the present study and those of other authors

(5,14). Comparing results of different

studies is however complicated by case-mix variation as some

centres may have a larger number of complicated cases with higher

probability for poor post-operative results (2). These concerns can be addressed by

using scores such as the SPITE score described by Black (15) (points for various factors, such as

presence of infection and previous surgery) or our own previously

presented complication score (7)

(Tables I and II).

A smaller study by Lucidi et al (16) published the results of 31 patients

with both CWU and CWD mastoidectomies and followed the QoL over an

average of 12 months post-op. They concluded that after 12 months,

epithelization is complete, and the patient can provide reliable

self-assessment concerning QoL. However, the authors noted that

such a short follow-up may not be sufficient to consider these

results as conclusive. The recurrence rate for CWU was 20-30% and

5-9% for CWD, in accordance with the conclusions of the present

study and those of other published studies (16,17).

A more extensive study by Kos et al (1) analysed 259 cases for both functional

and anatomical results for a period of 1 to 24 years (mean period

of 7 years, very similar to the present study). Recurring

infections of the cavity were reported in 11.9% (n=31) of cases

within 6 years post-op and in 6.5% (n=17) of cases >6 years

post-op. Overall, a dry and self-cleaning cavity was obtained in

95% of cases. Complications included polyps, recurrent

cholesteatoma, TM perforation and meatal stenosis (1). These results were considered congruent

with those reported by a significant number of other researchers

(18-21).

In comparison, a study by Kuo et al (22) reported a total of 4.9% ear discharge

with residual cholesteatoma mainly affecting the attic and

retrotympanum, which was similar to other previously published

studies (22-24).

Nadol (25) defined the sigmoid

sinus and tegmen air cells as the most common recurrence site,

while Veldman and Braunius (20)

considered the facial nerve and sigmoid sinus as most frequent

(20). A previous study by Prasanna

Kumar et al (26) defined

the mastoid cells as the most common recurrence site, followed by

sinodural angle, sinus tympani and tegmen antri region.

A similar study was performed by Pareschi et

al (27) reported long-term

anatomical and functional results (10 years follow-up) for a total

of 895 patients with a total recidivism rate of 7.7% (n=69), of

which 6.7% (n=60) showed persistence of disease and 1% (n=9) showed

recurrence. Of the 60 cases, the largest rate of persistence was in

the posterior mesotympanum (n=52), followed by the anterior

mesotympanum (n=5) and hypotympanum (n=3), which validates our

previously stated conclusions on lesion distribution (7). Pareschi et al (27) and Vartiainen (28) also stated that prognostic factors

for recidivism include the status of the TM and middle-ear mucosa,

age of the patient and length of follow-up, since cholesteatoma

recurrence can develop even after 12 years, thus confirming the

conclusions of the present study.

Blanco et al (29) also reported on 45 cases of CWD

surgery with a success rate of 93.3 and 6.6% recurrence, which was

less than other similar studies such as Lin and Oghala (30). The main limitation of the previous

study by Blaco et al was the short follow-up period of only

28 months (29).

To conclude, successful mastoidectomy was defined in

the current study as the total absence of otorrhea episodes after

total epithelization of cavity and failure of the presence of at

least one such episode. A successful drainage (anatomical results)

ensured long-term stability of hearing (functional results). The

two types of results of mastoidectomy were expressions of the same

phenomenon defined as a conversion of a static population by binary

division in respect to the spatial distribution of its constituting

units. Drainage results were found to be linked by an analytical

function to factors with clinical predictive significance, such as

complications of disease, exteriorization of suppurative disease,

lesions of the ME mucosa and TM, rank of surgery, status of the OC,

age of patient and length of follow-up. The global drainage success

rate was 77.5%, and the best self-cleaning rate was 86% with a

global self-cleaning rate of 70%. From a practical point of view,

no surgeon should expect to drain the entire endo-temporal

structure since this type of exercise is rarely realized in

experiments or dissections. This means that we must admit that some

of the pneumatic cavities cannot be surgically approached, dividing

the mastoid bone into surgical cavities and non-surgical cavities.

Practically and ideally, we can clean out a maximum of 84% of the

mastoid and petrous cells. Our results of almost 78% are congruent

to this theory. The remaining 16% may contain irreversible lesions.

The rate of success of mastoidectomy is entirely dependent on the

chance that all lesions be in a surgical area and this chance is a

function of the proportion of pneumatic cells for each of the

mentioned areas. Most of the non-surgical cavities are located in

the tympanic cavity, protympanum and adjacent cells. The more

remnant lesions in non-surgical cells, the higher the failure rate

and intensity (higher number of otorrhea episodes, lower patient

comfort).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

HM and MR contributed equally to this work and

should, therefore, both be considered first authors of this

article. HM and MR were responsible for the original idea,

conception, patient selection and care, operations, data collection

and editing structure. AIM, GC AB and MAS made substantial

contributions to acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data

and gave a final view of the article. MAS was also responsible for

the data analysis and graphical representation of the results. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript. HM and MR

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

For this study, ethical approval was obtained from

the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Titu

Maiorescu University (approval no. 1/25.05.2021; Bucharest,

Romania). All patients provided informed written consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kos MI, Castrillon R, Montandon P and

Guyot JP: Anatomic and functional long-term results of canal

wall-down mastoidectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 113:872–826.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mukherjee P, Sauders N, Liu R and Fagan P:

Long-term outcome of modified radical mastoidectomy. J Laryngol

Otol. 118:612–616. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lv J, Li H, Wu X, Chen X and Huang Y:

Functional results of revision canal wall down mastoidectomy. J

Bio-X Res. 2:98–103. 2019.

|

|

4

|

Nyrop M and Bonding P: Extensive

cholesteatoma: Long-term results of three surgical techniques. J

Laryngol Otol. 111:521–526. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cook J, Krishnan S and Fagan PA: Hearing

results following modified radical versus canal-up mastoidectomy.

Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 105:379–383. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mocanu H, Mocanu AI, Drăgoi AM and

Rădulescu M: Long-term histological results of ossicular chain

reconstruction using bioceramic implants. Exp Ther Med.

21(260)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mocanu H, Mocanu AI, Bonciu A, Coadă G,

Schipor MA and Rădulescu M: Analysis of long-term functional

results of radical mastoidectomy. Exp Ther Med.

22(1216)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Neudert M, Bornitz M, Mocanu H,

Lasurashvili N, Beleites T, Offergeld C and Zahnert T: Feasibility

study of a mechanical real-time feedback system for optimizing the

sound transfer in the reconstructed middle ear. Otol Neurotol.

39:e907–e920. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mocanu H, Bornitz M, Lasurashvili N and

Zahnert T: Evaluation of Vibrant® Soundbridge™

positioning and results with laser Doppler vibrometry and the

finite element model. Exp Ther Med. 21(262)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Neagu A, Mocanu AI, Bonciu A, Coadă G and

Mocanu H: Prevalence of GJB2 gene mutations correlated to presence

of clinical and environmental risk factors in the etiology of

congenital sensorineural hearing loss of the Romanian population.

Exp Ther Med. 21(612)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Fagan PA: Modified radical mastoid surgery

for chronic ear disease. Ann Acad Med Singap. 20:665–673.

1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Perez de Tagle JR, Fenton JE and Fagan PA:

Mastoid surgery in the only hearing ear. Laryngoscope. 106:67–70.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Alecu I, Mocanu H and Călin IE:

Intellectual mobility in higher education system. Rom J Mil Med.

120:16–21. 2017.

|

|

14

|

Fisch U and Schmid S: Radical

mastoido-epitympanectomy with tympanoplasty and partial

obliteration: A new surgical procedure? Ann Acad Med Singap.

20:614–617. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Black B: Prevention of recurrent

cholesteatoma: Use of hydroxyapatite plates and composite grafts.

Am J Otol. 13:273–278. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lucidi D, de Corso E, Paludetti G and

Sergi B: Quality of life and functional results in canal wall down

vs canal wall up mastoidectomy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital.

39:53–60. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kerckhoffs KG, Kommer MB, van Strien TH,

Visscher SJ, Bruijnzeel H, Smit A and Grolman W: The disease

recurrence rate after the canal wall up or canal wall down

technique in adults. Laryngoscope. 126:980–987. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Austin OF: Staging in cholesteatoma

surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 103:143–148. 1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Parisier SC, Hanson MB, Han JC, Cohen AJ

and Selkin BA: Pediatric cholesteatoma: An individualized,

single-stage approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 115:107–114.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Veldman JE and Braunius WW: Revision

surgery for chronic otitis media: A learning experience. Report on

389 cases with a long-term follow-up. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol.

107:486–491. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lau T and Tos M: Treatment of sinus

cholesteatoma. Long-term results and recurrence rate. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 114:1428–1434. 1988.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kuo CY, Huang BR, Chen HC, Shih CP, Chang

WK, Tsai YL, Lin YY, Tsai WC and Wang CH: Surgical results of

retrograde mastoidectomy with primary reconstruction of the ear

canal and mastoid cavity. Biomed Res Int.

2015(517035)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gaillardin L, Lescanne E, Moriniere S,

Cottier JP and Robier A: Residual cholesteatoma: Prevalence and

location. Follow-up strategy in adults. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol

Head Neck Dis. 129:136–140. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Haginomori AI, Takamaki A, Nonaka R and

Takenaka H: Residual cholesteatoma: Incidence and localization in

canal wall down tympanoplasty with soft-wall reconstruction. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134:652–657. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Nadol JB Jr: Causes of failure of

mastoidectomy for chronic otitis media. Laryngoscope. 95:410–413.

1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Prasanna Kumar S, Ravikumar A and Somu L:

Modified radical mastoidectomy: A relook at the surgical pitfalls.

Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 65 (Suppl 3):S548–S552.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Pareschi R, Lepera D and Nucci R: Canal

wall down approach for Tympano-mastoid cholesteatoma: Long-term

results and prognostic factors. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital.

39:122–129. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Vartiainen E: Ten-year results of canal

wall down mastoidectomy for acquired cholesteatoma. Auris Nasus

Larynx. 27:227–229. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Blanco P, González F, Holguín J and Guerra

C: Surgical management of middle ear cholesteatoma and

reconstruction at the same time. Colomb Med (Cali). 45:127–131.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lin JW and Oghalai JS: Can radiologic

imaging replace second-look procedures for cholesteatoma.

Laryngoscope. 121:4–5. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|