Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS) is the common pathological

cause of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (1). Activation and injury of vascular

endothelial cells, sub-endothelial deposition of oxidized

low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), formation of foam cells under the

vascular intima and proliferation and migration of vascular smooth

muscle cells (VSMCs) are the main events in the pathogenesis of AS

(2). Aberrant proliferation and

migration of VSMCs are common pathological features of AS,

restenosis after stenting and hypertension (3,4).

Fibulin-5 is a glycoprotein that consists of 448

amino acids and is involved in regulating extracellular matrix

(5). Recent data showed that

fibulin-5 expression was decreased in atherosclerotic plaque

tissues in human aneurysmatic aortas compared with healthy vessels

(6). Another previous study

suggested that fibulin-5 overexpression reduces MMP levels by

inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (7). Yin Yang-1 (YY1) is a widely expressed

transcription factor belonging to the Gli-Kruppel class of zinc

finger proteins that can bind transcriptional initiation repeats to

alter the activities of target promoters (8,9). Its

overexpression can cause the abnormal transcription of downstream

genes, participating in disease occurrence, such as diabetes and B

lymphoma (8,10,11).

YY1 was reported to serve an important role in AS by mediating the

proliferation and migration of VSMCs (12). In addition, a previous study

indicated that YY1 was involved in the formation of foam cells in

response to oxLDL (13). The

present study was therefore designed to investigate the potential

interaction between YY1 and the promoter region of fibulin-5, and

the role of fibulin-5 in ox-LDL-treated VSMCs.

Materials and methods

Collection of clinical samples

In the present study, five patients with coronary

heart disease (CHD; male, n=2; female, n=3), with an average age of

65.1±2.4 years, were diagnosed by coronary angiography in The Laixi

Municipal Hospital (Laixi, China) between June 2019 and August

2020. The control group was also composed of five individuals

(male, n=2; female, n=3) with an average age of 62.3±3.1 years, who

were present in the Laixi Municipal Hospital for routine physical

examination. The inclusion criterion for coronary heart disease

cases was the diameter stenosis of at least one major coronary

artery of patients with stable angina (>80%). The exclusion

criteria were as follows: i) Unstable angina pectoris or myocardial

infarction; ii) comorbidity with other organic heart diseases, such

as rheumatic heart disease and myocardiopathy; iii) comorbidity

with severe liver and kidney disease; iv) comorbidity with familial

hypercholesterolemia; v) comorbidity with malignancies; and vi)

comorbidity with inflammatory diseases. A total of 3 ml venous

blood was collected from each participant. Oral informed consent

was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment in the

present study. The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Laixi Municipal Hospital (approval no.

ky-2020-041-03).

Human aortic (HA)-VSMC culture

HA-VSMCs were purchased from the American Type

Culture Collection (cat. no. CRL-1999) and cultured in DMEM (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C with 5% CO2. Different

concentrations of ox-LDL (Yeasen Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co.,

Ltd., Shanghai, China) dissolved into DMEM medium (0, 50, 100 and

150 µg/ml) were added to induce cell calcification at 37˚C for 48

or 72 h.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) assay

Total RNA from VSMCs was extracted with

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) according to the instructions of the supplier. A total of 1

µg mRNA per sample was reverse transcribed into cDNA using

PrimeScript™ RT Reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) at 37˚C for 15 min

and 85˚C for 5 sec. Subsequently, SYBR Green kit (cat. no. 208054;

Qiagen GmbH) was used to prepare a 20 µl qPCR reaction mix and qPCR

was performed on the StepOne Real Time PCR instrument (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The primer sequences were: Fibulin-5

Forward: 5'-CTCACTGTTACCATTCTGGCTC-3', Reverse:

5'-GACTGGCGATCCAGGTCAAAG-3'. YY1 Forward:

5'-ACGGCTTCGAGGATCAGATTC-3', Reverse: 5'-TGACCAGCGTTTGTTCAATGT-3'.

Smooth muscle α-actin (α-SMA) Forward: 5'-AAAAGACAGCTACGTGGGTGA-3',

Reverse: 5'-GCCATGTTCTATCGGGTACTTC-3'. GAPDH:

5'-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3', Reverse:

5'-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3'. PCR was performed at 95˚C for 30

sec, followed by 45 cycles of 95˚C for 5 sec and 60˚C for 30 sec.

GAPDH was used as an internal reference. The relative levels of

mRNA were calculated with the 2-ΔΔCq method (14).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

VSMCs (1x104 cells/well) were seeded into

96-well plates and then incubated for 24 h at 37˚C. Following

ox-LDL treatment or transfection of Ov-Fibulin-5 plasmids and

ox-LDL treatment, the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM

medium. A total of 10 µl CCK-8 solution (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) was added to each well for incubation at 37˚C for 1

h. The absorbance at 450 nm was subsequently detected using a

microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Western blotting

Following the x-LDL treatment or transfection of

Ov-Fibulin-5 plasmids plus ox-LDL treatment, or the co-treatment of

transfection of Ov-YY1 and siRNA-Fibulin-5 plus ox-LDL treatment,

VSMCs were collected and lysed by adding RIPA buffer (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) on ice for 30 min. The supernatant was

collected after centrifugation at 4˚C at 14,000 x g for 20 min. The

protein concentration of each group was detected by a BCA kit

(Abcam). A total of 20 µg each protein sample was separated by 10%

SDS-PAGE and then transferred into PVDF membrane. The membranes

were then blocked with 5% BSA (MilliporeSigma) at room temperature

for 2 h and incubated with primary antibodies (Fibulin-5; cat. no.

ab109428, 1:1,000; cyclin D1; cat. no. ab16663, 1:200; CDK2; cat.

no. ab32147, 1:1,000; MMP2; cat. no. ab92536, 1:1,000; MMP9; cat.

no. ab76003, 1:1,000; GAPDH; cat. no. ab8245, 1:5,000. Abcam) at

4˚C overnight. After incubation with a secondary antibody at 37˚C

for 2 h (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG; cat. no. ab7090, 1:10,000. Abcam,

England), a ECL color development reagent (cat. no. ab133409;

Abcam) was added to the membranes. The density of the protein bands

was analyzed using the ImageJ software (version 1.53b; National

Institutes of Health).

Wound healing assay

HA-VSMCs in a logarithmic proliferation phase were

seeded into six-well plates at 2x104 cells per well.

After routine overnight culture, the cells received transfection of

Ov-Fibulin-5 plasmids and ox-LDL treatment, or the transfection of

Ov-YY1 and siRNA- Fibulin-5 and ox-LDL treatment, with three

replicates per group. When 80% cell confluence was reached, a

scratch was performed using a horizontal line perpendicular to the

back with a 20-µl pipette tip. The cells were washed by phosphoric

acid buffer three times and cultured in serum-free DMEM medium. PBS

was used to rinse the plates and serum-free DMEM medium was added

at 37˚C. The cell migration was observed under a light microscope

at 0 and 24 h (Olympus Corporation; magnification, x100). The

relative migration was calculated using following formula: (Initial

width at 0 h-final width at 24 h)/width at 0 h.

Transwell assay

The HA-VSMCs received transfection with Ov-Fibulin-5

plasmids and ox-LDL treatment, or transfection of Ov-YY1 and

siRNA-Fibulin-5 and ox-LDL treatment and their concentration was

adjusted to 2x108 cells/ml. Diluted Matrigel (25 µl; BD

Biosciences) with DMEM medium without serum was added to upper

chamber at 37˚C. A total of 200 µl cell suspension prepared with

serum-free medium was added to the upper chambers of a Transwell

insert (cat. no. 3422; 8-µm; Corning). DMEM with 10% FBS was added

to the lower chamber. After 24 h of incubation at 37˚C, the cells

that have gone through the membrane were fixed using 4% methanol

and stained with crystal violet at room temperature for 10 min and

images were captured under an inverted microscope (Olympus

Corporation, magnification, x100).

Plasmid transfection

Lipofectamine® 3000 transfection reagent

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used according to the

manufacturer's instructions to transfect YY1-overexpressing

plasmids (0.5 µg; pcDNA-YY1; Ov-YY1; Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.)

or its control (0.5 µg; pcDNA), or siRNA targeting fibulin-5 (15

pmol; 5'-GAUUGUUGUGAGGAGUCUAGC-3') or its negative control (15

pmol; siRNA-NC, scrambled RNA, 5'-GUGAUUGCAUGAUUGUGCGGA-3') into

HA-VSMCs, which were constructed and purchased from Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. After 24 h at 37˚C, the cells were treated

with 100 µg/ml ox-LDL (100 µg/ml ox-LDL significantly promoted cell

proliferation) for 24 h at 37˚C for further experiments.

Bioinformatics

Using PROMO (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3,

access date: 10.09.2020) and Transcription Factor DataBase (TFDB;

http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/HumanTFDB#!/, access

date: 10.09.2020) tools, YY1 was predicted to bind to the promoter

region of fibulin-5.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

(ChIP)

After chromatin was subjected to ultrasonication,

magnetic beads (60 µl) coated with anti-YY1 or anti-IgG (EMD

Millipore) were added to form immune complex. The immune complex

was washed with wash buffer (low salt wash buffer, high salt wash

buffer, LiCl wash buffer and TE buffer, in sequence) and then was

centrifuged at 4˚C at 16,000 x g for 2 min. Next, collected

immunoprecipitation was eluted with eluent including 10% SDS,

NaHCO3 and ddH2O at 65˚C for 15 min. 20 µl NaCl was added for

incubation at 65˚C overnight. After de-crosslink, 1 µl RNaseA was

added for incubation for 1 h at 37˚C. RT-qPCR was performed to

analyze precipitated DNA fragments.

Dual-luciferase reporter gene

assay

Luciferase activity was detected after

co-transfection of fibulin-5 promoter site 1 (TCCCAGCCCCCGCACC)

with mutations or wild-type sequence luciferase reporter genes (0.1

µg; pGL3-basic; Promega Corporation) and YY1 overexpressing

plasmids (0.2 µg)or its control plasmids (empty plasmids) into 293T

cells (ATCC, USA) with Lipofectamine® 3000 following the

manufacturer's protocol. Renilla luciferase was used as

control reporter gene. After 48 h, luciferase activity was detected

using Dual luciferase reporter gene assay kit according to the

manufacturer's instructions (cat. no. RG028; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology).

Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analyzed by GraphPad

Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The measurement data

were represented by the mean ± SD and one-way ANOVA was used for

comparison between multiple groups, followed by Tukey's test.

Chi-square test was used to compare the two rates of age, smoking,

drinking, or hypertension between CHD and control. Each experiment

was repeated at least three times. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Ox-LDL induces low fibulin-5

expression in HA-VSMCs

The level of high-density lipoprotein in the

peripheral blood samples of patients with CHD was significantly

lower than that in the control group (Table I). However, there was no statistical

significance in the comparison of all other indicators between the

two groups (Table I).

| Table IClinical characteristics of patients

with CHD. |

Table I

Clinical characteristics of patients

with CHD.

|

Characteristics | CHD (n=5) | Control (n=5) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 65.1±2.4 | 62.3±3.1 | >0.05 |

| Smoking, % | 20 | 20 | >0.05 |

| Drinking, % | 20 | 20 | >0.05 |

| Hypertension,

% | 60 | 60 | >0.05 |

| Cholesterol,

mmol/l | 3.98±0.66 | 4.01±0.42 | >0.05 |

| High-density

lipoprotein, mmol/l | 0.94±0.12 | 1.35±0.29 | <0.01 |

| Low density

lipoprotein, mmol/l | 2.12±0.63 | 2.15±0.64 | >0.05 |

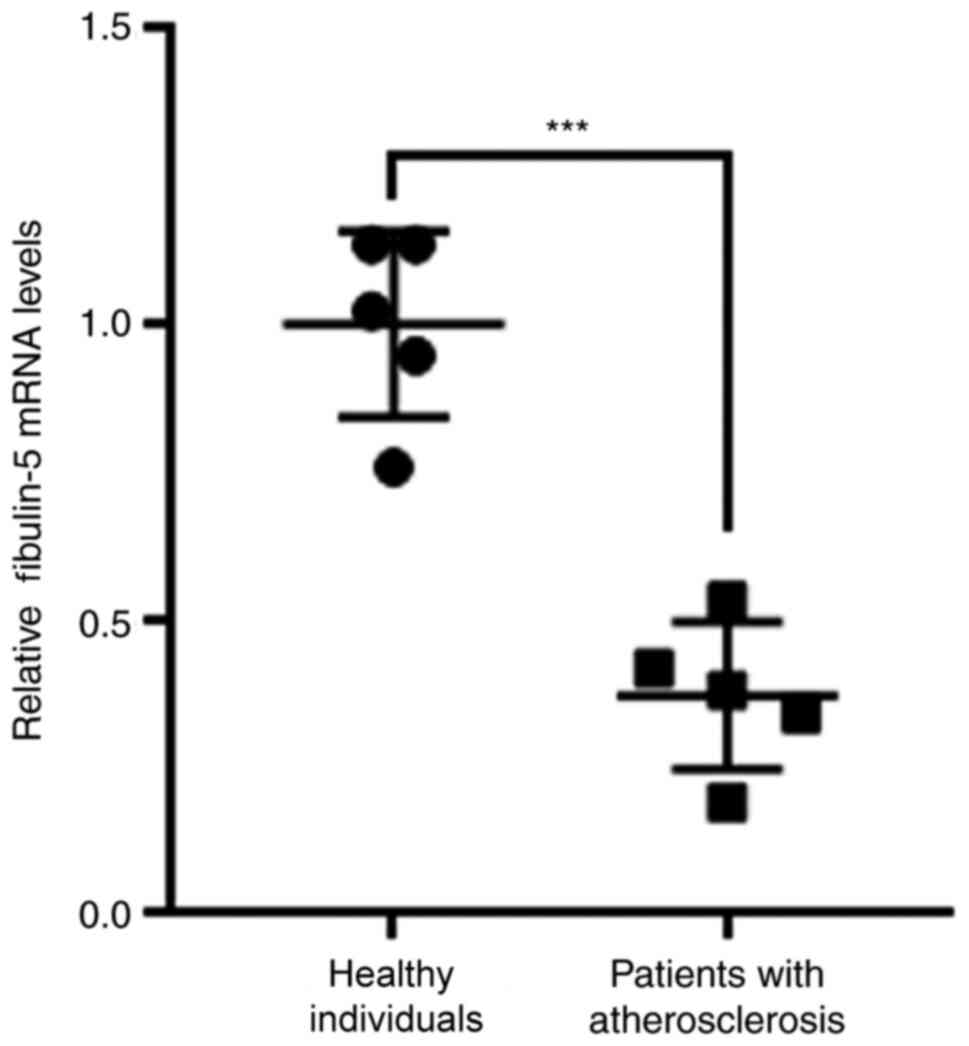

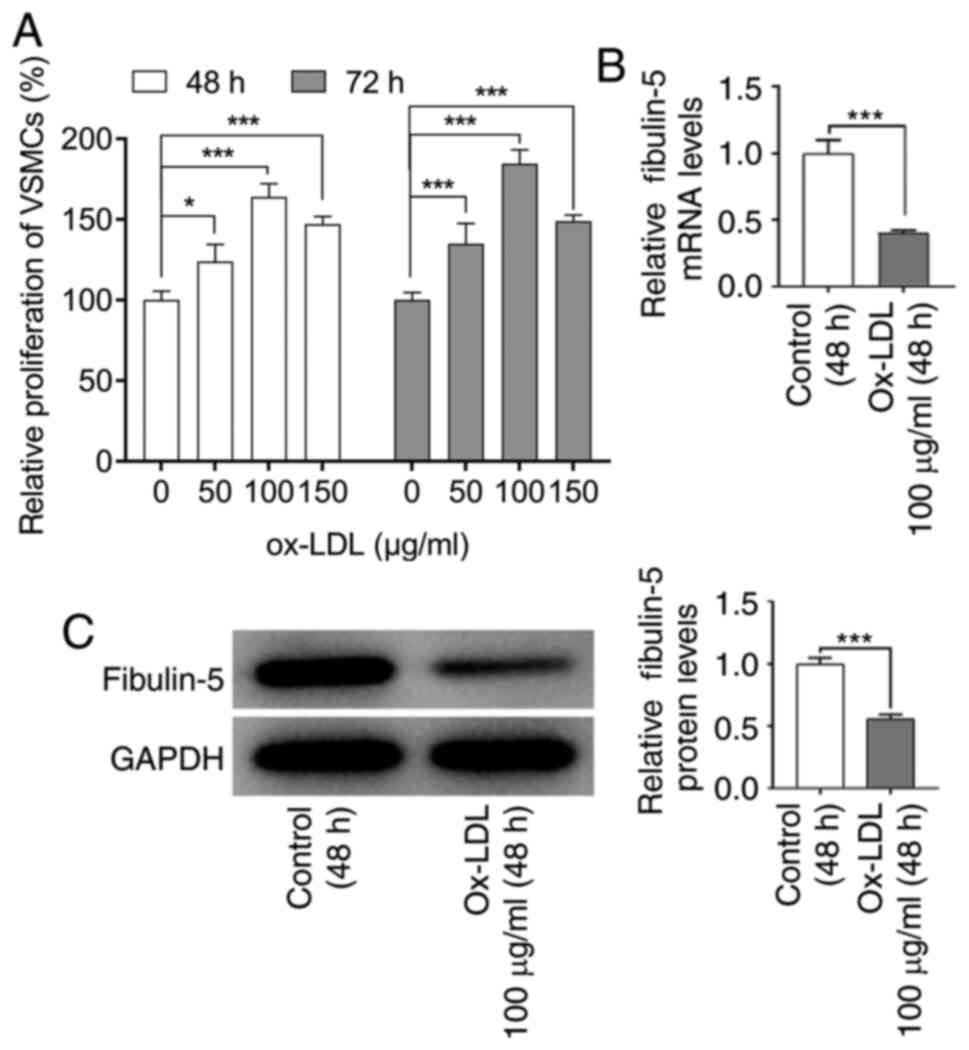

To explore the role of fibulin-5 in AS, fibulin-5

mRNA expression was quantified in the peripheral blood of patients

with AS. Fibulin-5 mRNA expression was significantly increased in

patients with AS compared with that in healthy individuals

(P<0.001; Fig. 1). VSMCs have

been previously reported to serve an important role in

atherogenesis (15). As indicated

in Fig. 2A, 100 µg/ml ox-LDL was

the concentration that increased VSMC viability the strongest

(P<0.001). This concentration was therefore selected for further

experiments. RT-qPCR and western blotting analyses of fibulin-5

expression in VSMCs indicated that the mRNA and protein levels of

fibulin-5 were significantly reduced after ox-LDL treatment

compared with those in the control group (P<0.001; Fig. 2B and C). To further investigate the role of

fibulin-5, HA-VSMCs treated with ox-LDL were transfected with a

fibulin-5-overexpressing plasmid.

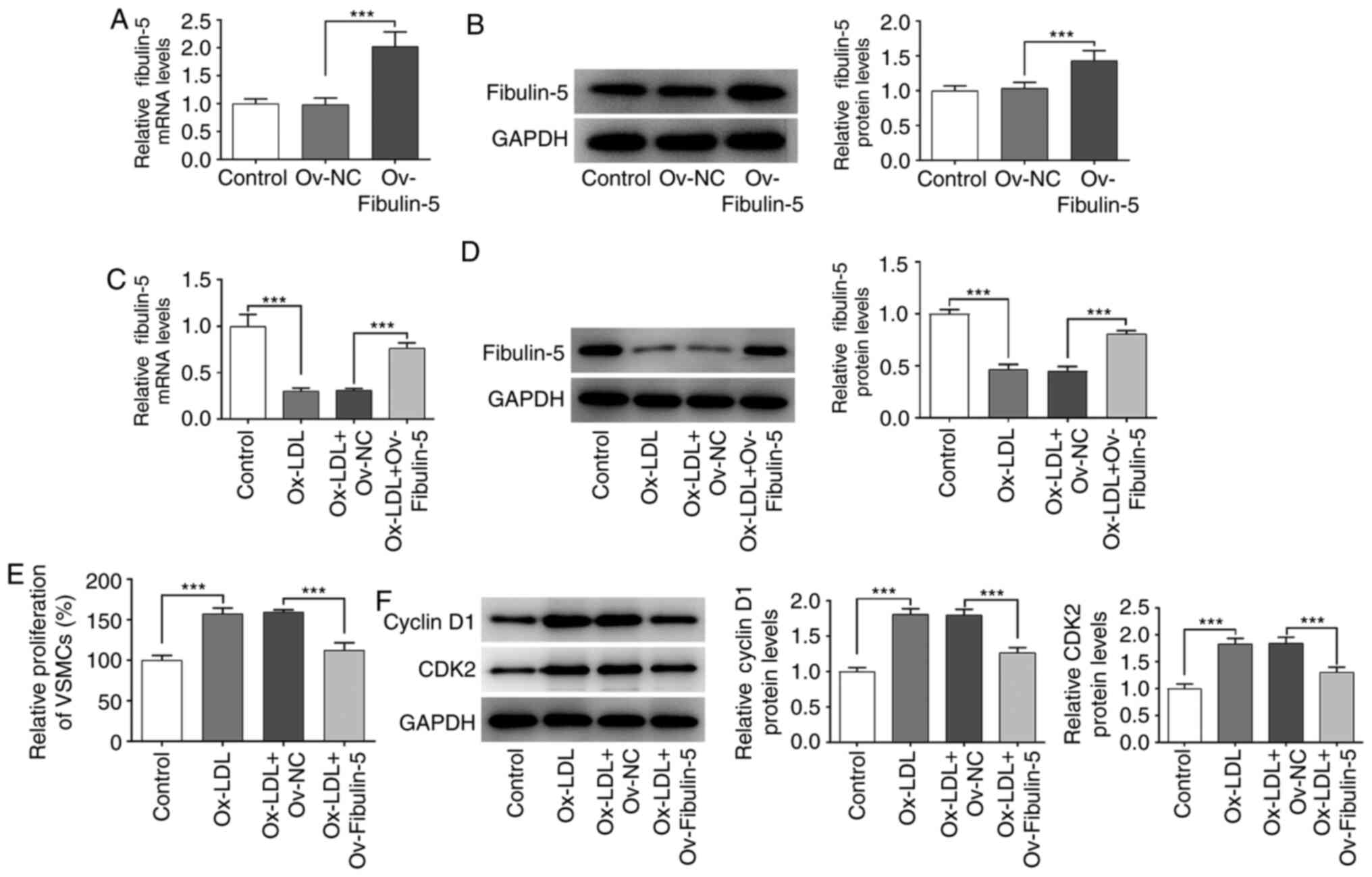

Fibulin-5 overexpression suppresses

HA-VSMC proliferation in response to ox-LDL

Since ox-LDL decreased fibulin-5 expression, it was

hypothesized that fibulin-5 serve a role in HA-VSMCs in response to

ox-LDL. As a transfection control, a vector overexpressing

(Ov)-fibulin-5 significantly increased the mRNA and protein

expression levels of fibulin-5 compared with that in the

Ov-negative control (NC) group (P<0.001; Fig. 3A and B). Analyzes of fibulin-5 expression in

ox-LDL-treated HA-VSMCs demonstrated that the reduced fibulin-5

expression was significantly reversed by fibulin-5 overexpression

(P<0.001; Fig. 3C and D). In VSMCs cycle progression, cyclin D1

and CDK2 are involved in promoting Rb phosphorylation, the

inhibition of which can lead to cycle arrest (16). VSMCs were subsequently subjected to

CCK-8 analysis to measure cell viability (P<0.001; Fig. 3E) whereas western blotting was used

to quantify protein levels of cell cycle proteins cyclin D1 and

CDK2 (P<0.001; Fig. 3F). The

present results demonstrated that the overexpression of fibulin-5

in HA-VSMCs reversed the increase in cell viability induced by

ox-LDL treatment, in addition to reversing the increased protein

expression of cyclin D1 and CDK2 induced by ox-LDL treatment

(P<0.001; Fig. 3E and F).

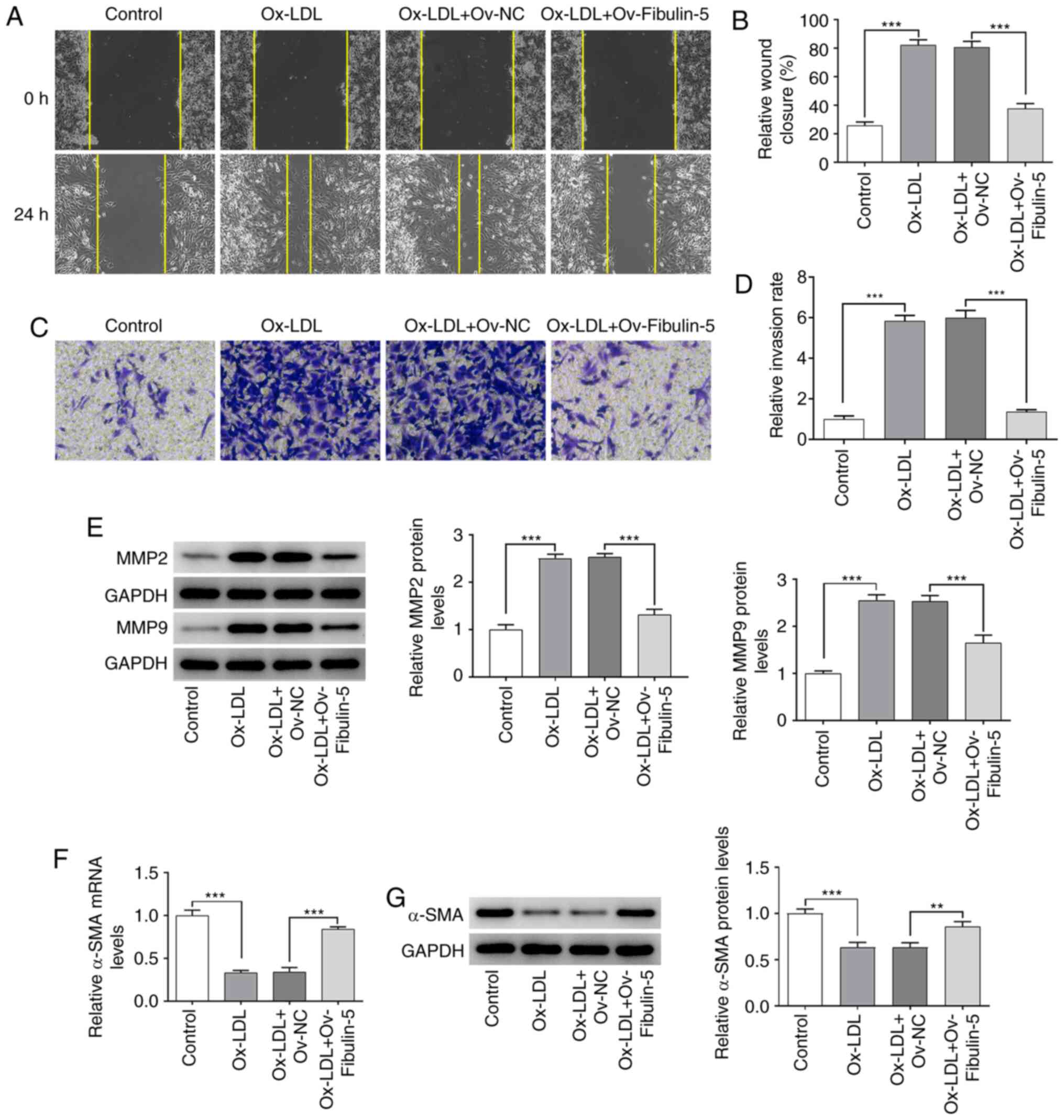

Cell migration and invasion were studied by

performing wound healing and Transwell assays, respectively. The

present results demonstrated that HA-VSMCs exhibited significantly

increased migration and invasion after ox-LDL treatment, which were

significantly reversed following fibulin-5 overexpression (all

P<0.001; Fig. 4A-D). MMP-2 and

MMP-9 expressed in VSMCs, modulated the collagen degradation of the

extracellular matrix and served a vital role in AS progression

(17).

Additionally, the protein expression of MMP2 and

MMP9, which participate in phenotype transition (18,19),

was quantified by western blotting, whilst the mRNA and protein

expression of α-SMA was measured by RT-qPCR and western blotting,

respectively. MMP2 and MMP9 protein expression was significantly

increased after ox-LDL treatment, an effect that was significantly

reversed by fibulin-5 overexpression (all P<0.001; Fig. 4E). Similarly, α-SMA mRNA and protein

expression were significantly decreased after ox-LDL treatment

(P<0.001), which was significantly reversed by fibulin-5

overexpression (P<0.01 and P<0.001; Fig. 4E-G).

YY1 binds to the promoter of fibulin-5

to induce its upregulation in HA-VSMCs

To further explore the role of fibulin-5 in AS,

PROMO and TFDB databases were used to predict whether YY1 can bind

to the promoter region of fibulin-5 to regulate fibulin-5

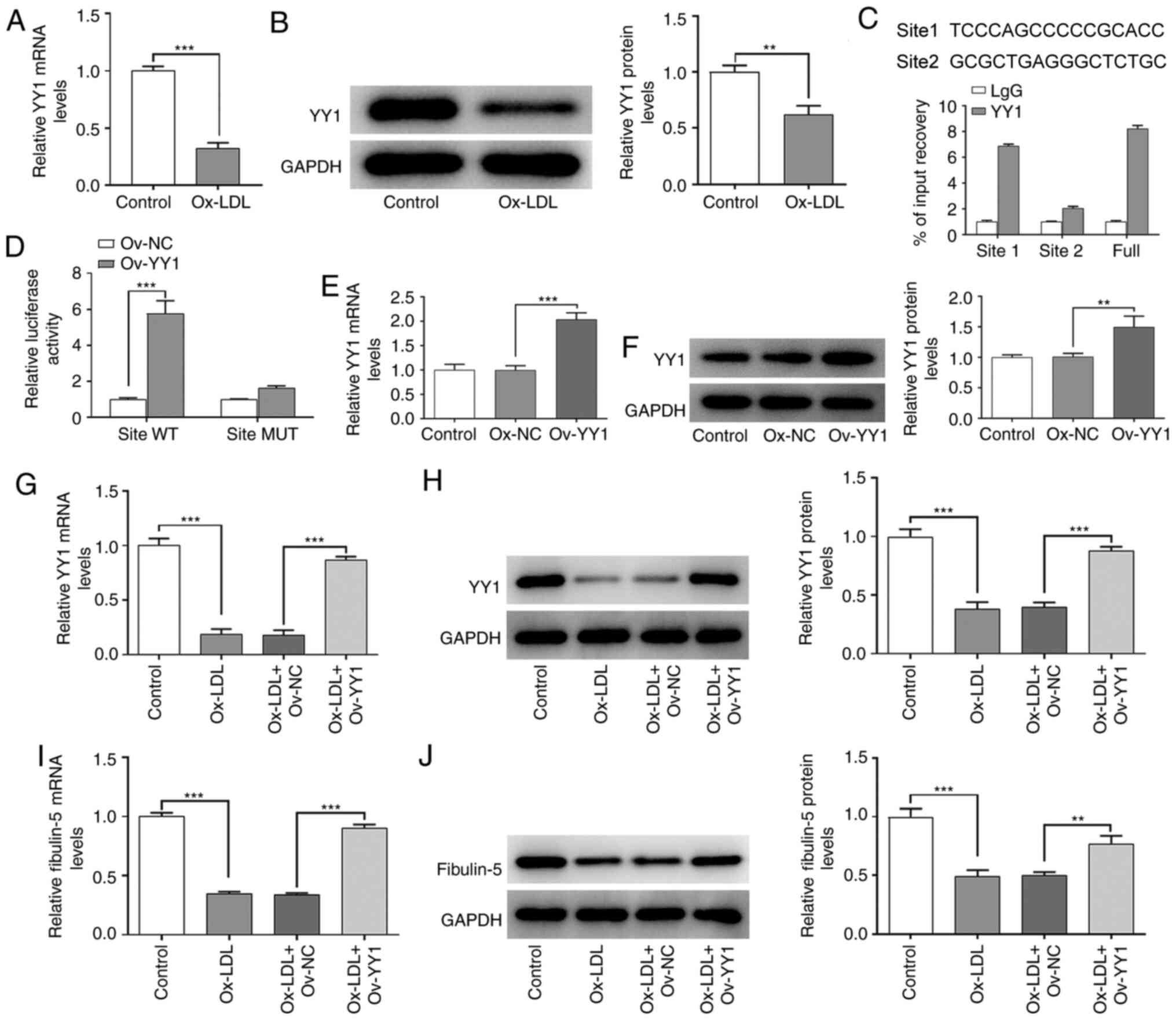

expression in ox-LDL-treated HA-VSMCs. The mRNA and protein

expression levels of YY1 were significantly decreased in

ox-LDL-treated HA-VSMCs compared with those in the control group

(P<0.01 and P<0.001; Fig. 5A

and B). Next, the two promoter

sites and the overall promoter region level of fibulin-5, were

detected by qPCR in an immunoprecipitation complex formed by using

YY1 antibody. Promoter site 1 was shown to be markedly enriched

(Fig. 5C). The luciferase activity

of the pGL4 luciferase reporter vectors containing the promoter

region of fibulin-5 with binding site (site 1) for YY1 was

significantly increased when YY1-overexpressing plasmids were

co-transfected into HA-VSMCs, compared with that in cells

co-transfected with the Ov-NC plasmid (P<0.001, Fig. 5D). When the pGL4 luciferase reporter

vectors with muted sites and Ov-NC or Ov-YY1 were co-transfected

into 293T cells, there was no significant difference in luciferase

activities between Ov-NC and Ov-YY1 (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that YY1

can bind to site 1 of the fibulin-5 promoter. The transfection

efficiency of the YY1-overexpressing plasmid was tested in Fig. 5E and F. As shown in Fig. 5E and F, cells transfected with Ov-YY1 showed

significantly higher YY1 expression levels compared with those in

cells transfected with Ov-NC (P<0.01 and P<0.001). As

indicated in Fig. 5G and H, overexpression of YY1 in the HA-VSMCs

significantly reversed the decreased mRNA and protein expression of

YY1 induced by ox-LDL treatment (P<0.001). Similarly, YY1

overexpression also significantly restored the expression of

fibulin-5, which was decreased after ox-LDL treatment (P<0.01

and P<0.001; Fig. 5I and

J).

YY1 mediates the effects of fibulin-5

on proliferation, migration and invasion in HA-VSMCs stimulated

with ox-LDL

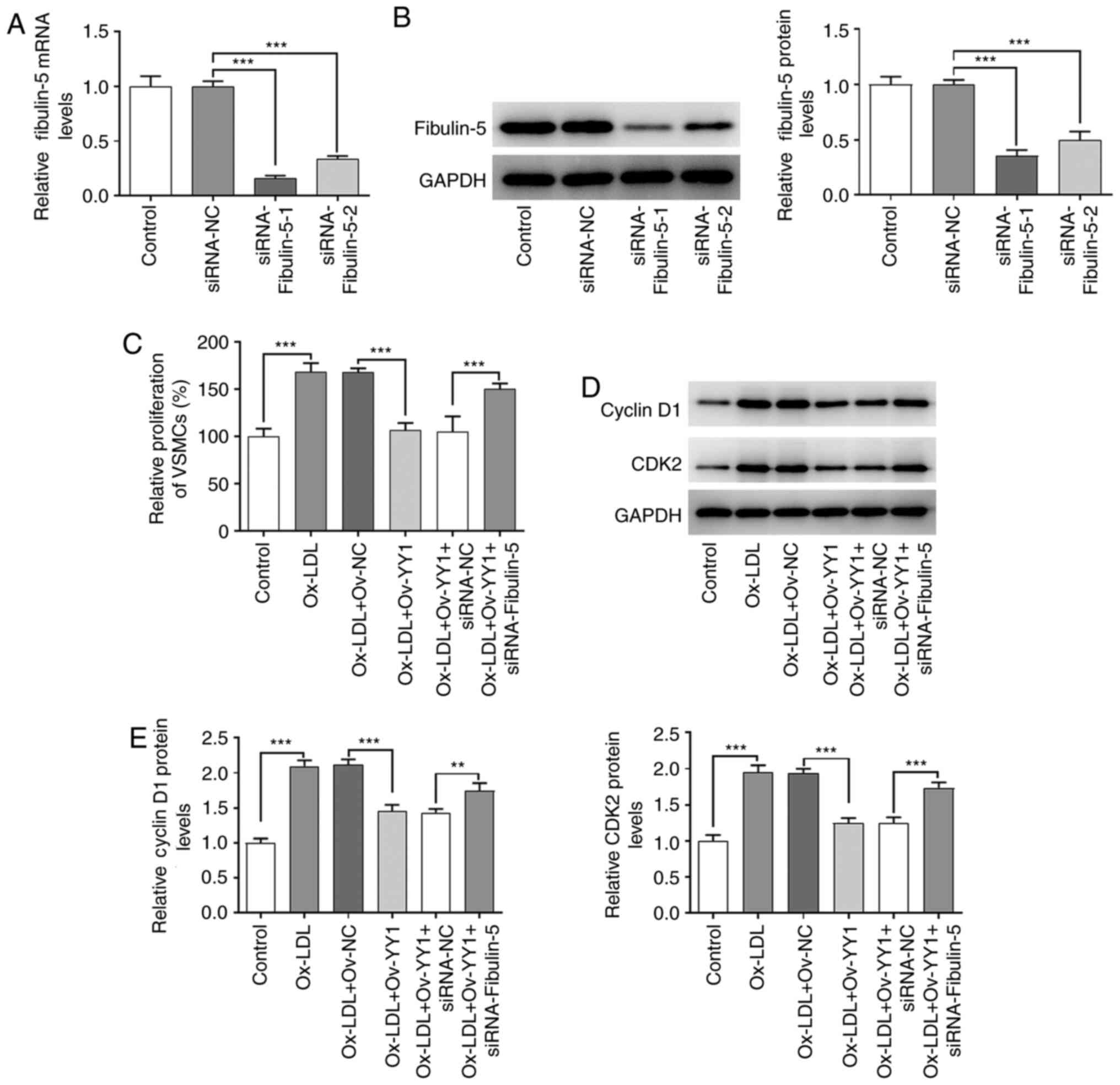

The present study next aimed to determine whether

fibulin-5 mediated the effects of YY1 in cultured HA-VSMCs

stimulated with ox-LDL. First, the transfection efficiency of small

interfering (si)RNA-fibulin-5 was tested in the HA-VSMCs. Analyzes

of fibulin-5 expression in HA-VSMCs demonstrated that it was

effectively knocked down by siRNA-Fibulin-5 transfection compared

with cell transfected with siRNA-NC (P<0.001; Fig. 6A and B). Since it was the most efficient in

knocking down fibuin-5 expression, si-fibulin-1 was selected for

further experiments. Based on the present results, it was

hypothesized that YY1 interacted with the promoter sites of

fibulin-5 to regulate cell proliferation, migration and invasion in

VSMCs treated with ox-LDL. First, cell viability was compared

between VSMCs transfected with siRNA-NC and with siRNA-fibulin-5.

Fibulin-5 silencing induced a significant reversal of the

potentiating effects due to YY1 overexpression on cell viability,

cyclin D1 and CDK2 expression (P<0.01 and P<0.001; Fig. 6C-E). Significant differences were

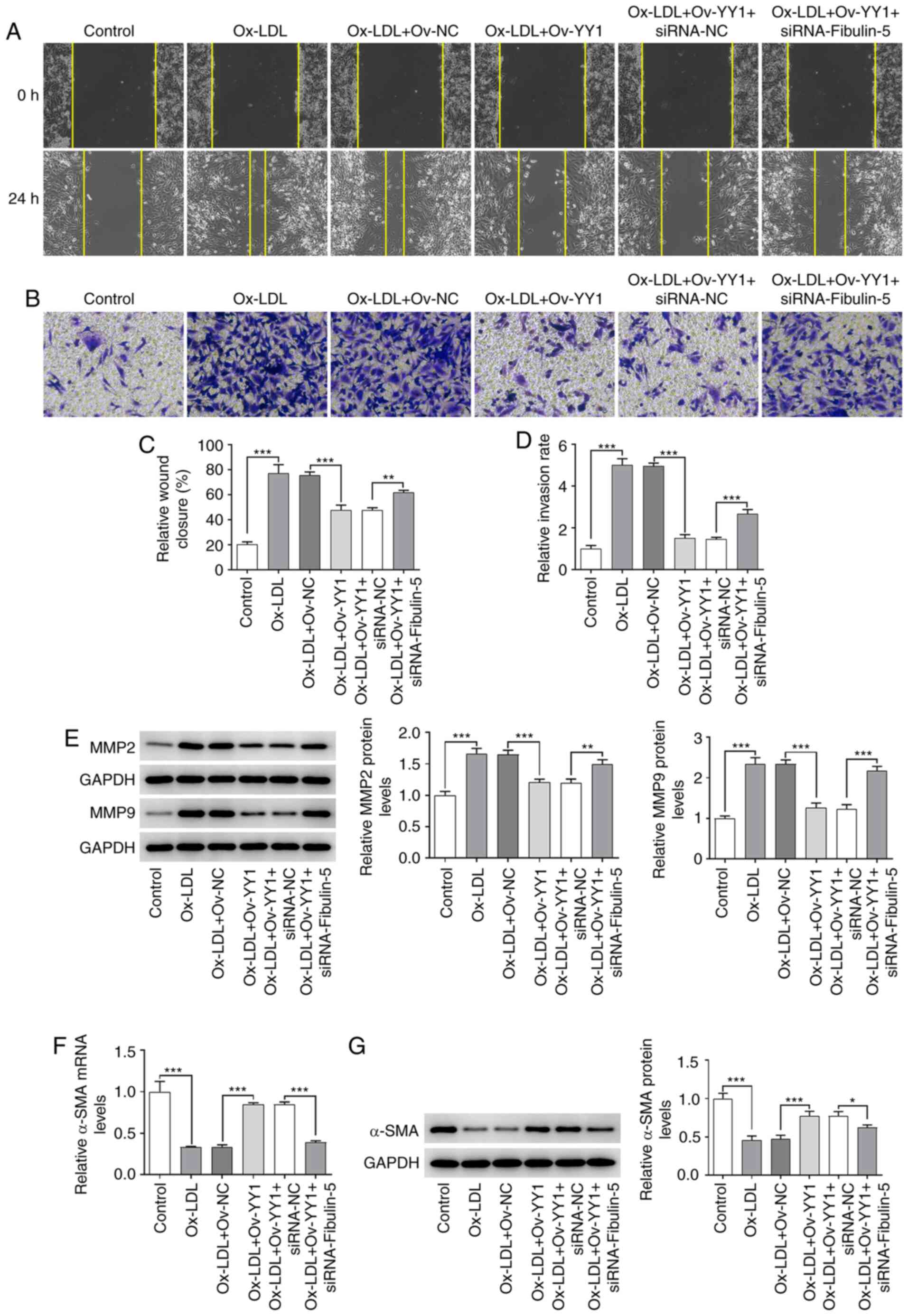

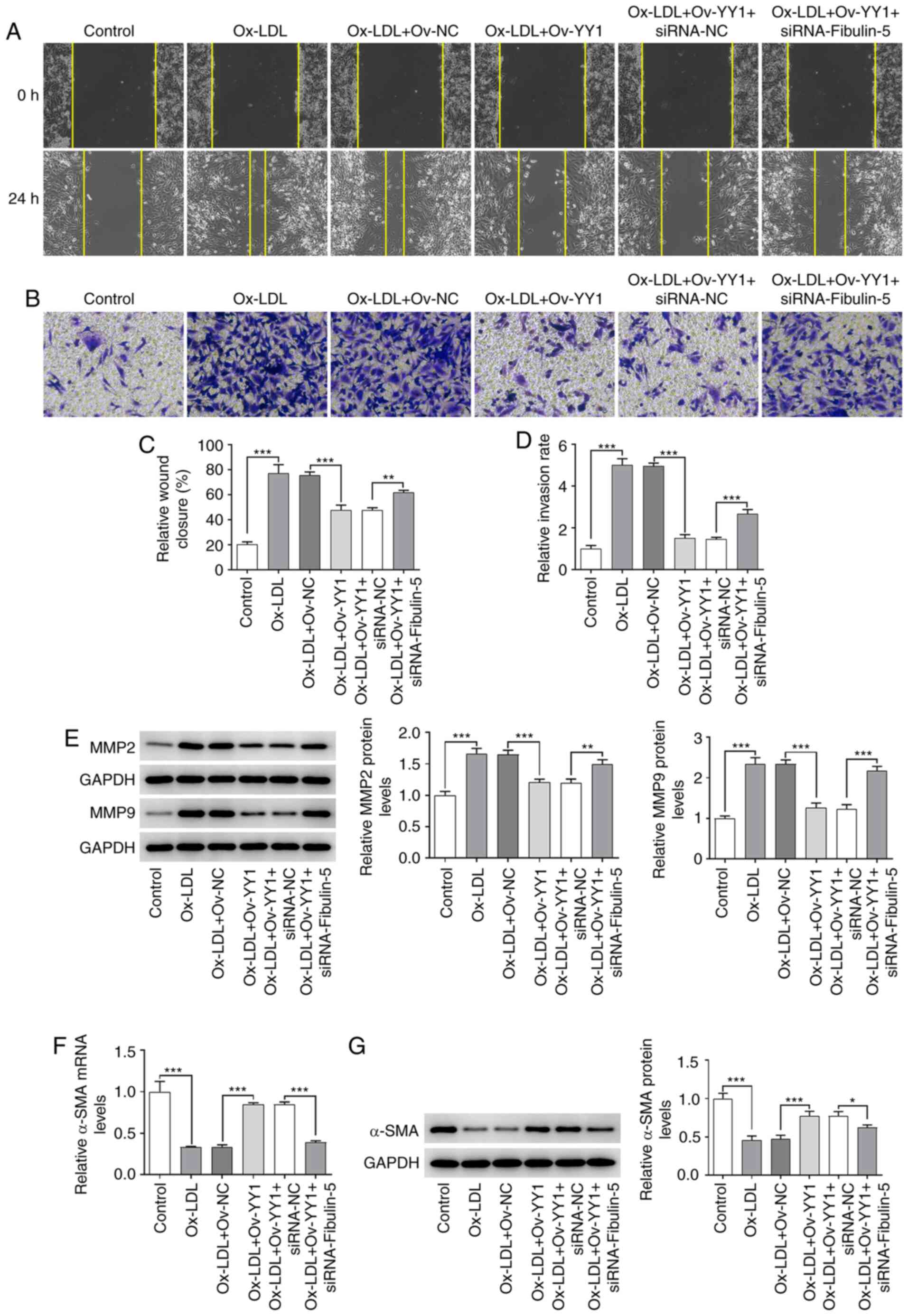

also observed in the cell migration and invasion of HA-VSMCs, and

the expression of MMP2, MMP9 and α-SMA between Ov-YY1 vs. Ov-NC and

between Ov-YY1+siRNA-NC and with Ov-YY1+siRNA-fibulin-5 (P<0.05,

P<0.01 and P<0.001; Fig.

7A-G). This suggests that YY1 participated in mediating the

effects of fibulin-5 on cell viability, migration and invasion

induced by ox-LDL.

| Figure 7The effects of YY1 overexpression

migration and invasion were reversed by fibulin-5 silencing.

HA-VSMCs after ox-LDL treatment, YY1 overexpression and/or

fibulin-5 knockdown were subjected to (A) wound healing and (B)

Transwell assays to compare (C) cell migration and (D) invasion.

Magnification, x100. (E) Western blot analyses were performed after

ox-LDL treatment, YY1 overexpression and/or fibulin-5 knockdown to

measure the protein expression of MMP2 and MMP9. (F) Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and (G) western blotting were

performed to determine α-SMA expression levels. Data are presented

as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. HA-VSMC, human aortic-vascular smooth

muscle cell; ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; YY1, Yin

Yang-1; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control; α-SMA,

smooth muscle α-actin. |

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that fibulin-5

participated in ox-LDL-induced cell viability, invasion and

migration in VSMCs. A previous study on the fibulin-5 mechanism

revealed that fibulin-5 was involved in arterial stiffening in

patients with AS (20). The present

study indicated that YY1 regulated the promoter activity and

expression levels of fibulin-5 in VSMCs under ox-LDL treatment,

which provided a new insight in the understanding of the role of

fibulin-5 in AS.

The role of fibulin-5 in AS was found to involve the

binding of extracellular superoxide dismutase to the vascular

tissue to modulate vascular superoxide production, which was

identified to serve a vital role in AS (21). As for the regulatory mechanism of

fibulin-5 promoter activity, a previous report indicated that SOX9

could regulate the fibulin-5 promoter activity in VSMCs under the

stimulus of TNF-α (22). In the

present study, a YY1 binding sequence on the fibulin-5 promoter was

identified and predicted, where it was verified further that YY1

could directly bind to the fibulin-5 promoter and regulate its

expression. This translated downstream to the regulation of the

biological processes of VSMCs in response to ox-LDL. However, the

molecular mechanism by which YY1 binding activates fibulin-5

transcription was not uncovered in the present study, which was

predicted to be associated with YY1 involvement in transcriptional

activation by forming complexes with some proteins, such as INO80

or Sp1(23) in the promoter of

fibulin-5. YY1 has been reported to be a transcriptional activator

of some genes, such as Xist in ES cells and CDC6 in HEK293 cells,

(24,25). For instance, YY1 initiated the

activity of the X-inactive specific transcript (Xist) promoter by

directly binding to the Xist 5' region in ES cells (24). Downstream, YY1 was also revealed to

be involved in the pathophysiology of AS by regulating cell

proliferation and apoptosis (12,26,27).

For example, a previous study reported that YY1 was involved in the

promoting effects of miR-544 on the maturation and antioxidative

effects of stem cell-derived endothelial-like cells (28). A previous mechanistic analysis of

YY1 in ox-LDL-treated macrophages of AS demonstrated that YY1 can

translocate into the nucleus and increase the expression of miR-29a

by binding to its transcriptional promoter region (27).

In addition to its regulatory role in cell

viability, invasion and migration, fibulin-5 overexpression

markedly reduced the expression levels of cyclin D1 and CDK2, which

regulate G1-phase cell cycle progression and

subsequently proliferation in VSMCs (29,30). A

previous study found that the expression levels of YY1, which is a

negative regulator of cyclin D1, could be regulated by miR-29a

(31). The present results suggest

that cyclin D1 and CDK2 can participate in the regulation of

YY1/fibulin-5 during cell proliferation. Although the present study

revealed that fibulin-5/YY1 affected the viability, invasion and

migration of HA-VSMCs stimulated with ox-LDL, whether this axis is

involved in the pathogenesis of AS requires further study, which is

a limitation of the present study.

In conclusion, the present study presented evidence

that fibulin-5, regulated by YY1, can suppress the viability,

invasion and migration of HA-VSMCs stimulated with ox-LD. The

present results provided a new insight for the further

investigation of the mechanism of AS. Targeting fibulin-5/YY1 can

be a potential therapeutic option for AS. However, further studies

should be performed, mainly on the molecular mechanism by which the

binding of YY1 can activate fibulin-5 transcription. In addition,

the mechanism of YY1/fibulin-5 would need to be validated in

vivo.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

LW and YZ made substantial contributions to the

conception and design of the study. LW collected clinical samples

and interpreted the patient data regarding fibulin-5 expression.

LW, CL, CF and YZ performed other experiments and collected data.

LW and YZ interpreted the data, drafted and revised the manuscript

for important intellectual content. LW and YZ confirm the

authenticity of the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Laixi Municipal Hospital (approval no.

ky-2020-041-03). Oral informed consent was obtained from all

participants prior to enrollment in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cao Q, Guo Z, Du S, Ling H and Song C:

Circular RNAs in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Life Sci.

255(117837)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kattoor AJ, Goel A and Mehta JL: LOX-1:

Regulation, signaling and its role in atherosclerosis. Antioxidants

(Basel). 8(218)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Cheng YC, Sheen JM, Hu WL and Hung YC:

Polyphenols and oxidative stress in atherosclerosis-related

ischemic heart disease and stroke. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2017(8526438)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lu QB, Wan MY, Wang PY, Zhang CX, Xu DY,

Liao X and Sun HJ: Chicoric acid prevents PDGF-BB-induced VSMC

dedifferentiation, proliferation and migration by suppressing

ROS/NF-κB/mTOR/P70S6K signaling cascade. Redox Biol. 14:656–668.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ito S, Yokoyama U, Nakakoji T, Cooley MA,

Sasaki T, Hatano S, Kato Y, Saito J, Nicho N, Iwasaki S, et al:

Fibulin-1 integrates subendothelial extracellular matrices and

contributes to anatomical closure of the ductus arteriosus.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 40:2212–2226. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Xu BF, Liu R, Huang CX, He BS, Li GY, Sun

HS, Feng ZP and Bao MH: Identification of key genes in ruptured

atherosclerotic plaques by weighted gene correlation network

analysis. Sci Rep. 10(10847)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Gao JB, Lin L, Men XQ, Zhao JB, Zhang MH,

Jin LP, Gao SJ, Zhao SQ and Dong JT: Fibulin-5 protects the

extracellular matrix of chondrocytes by inhibiting the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and relieves osteoarthritis. Eur

Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 24:5249–5258. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Meliala ITS, Hosea R, Kasim V and Wu S:

The biological implications of Yin Yang 1 in the hallmarks of

cancer. Theranostics. 10:4183–4200. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Liu H, Schmidt-Supprian M and Shi Y,

Hobeika E, Barteneva N, Jumaa H, Pelanda R, Reth M, Skok J,

Rajewsky K and Shi Y: Yin Yang 1 is a critical regulator of B-cell

development. Genes Dev. 21:1179–1189. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Blättler SM, Cunningham JT, Verdeguer F,

Chim H, Haas W, Liu H, Romanino K, Rüegg MA, Gygi SP, Shi Y and

Puigserver P: Yin Yang 1 deficiency in skeletal muscle protects

against rapamycin-induced diabetic-like symptoms through activation

of insulin/IGF signaling. Cell Metab. 15:505–517. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Sui G, Affar el B and Shi Y, Brignone C,

Wall NR, Yin P, Donohoe M, Luke MP, Calvo D, Grossman SR and Shi Y:

Yin Yang 1 is a negative regulator of p53. Cell. 117:859–872.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yue Y, Lv W, Zhang L and Kang W: miR-147b

influences vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration

via targeting YY1 and modulating Wnt/β-catenin activities. Acta

Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 50:905–913. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tian FJ, An LN, Wang GK, Zhu JQ, Li Q,

Zhang YY, Zeng A, Zou J, Zhu RF, Han XS, et al: Elevated

microRNA-155 promotes foam cell formation by targeting HBP1 in

atherogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 103:100–110. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Grootaert MOJ, Moulis M, Roth L, Martinet

W, Vindis C, Bennett MR and De Meyer GRY: Vascular smooth muscle

cell death, autophagy and senescence in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc

Res. 114:622–634. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kavurma MM and Khachigian LM: Sp1 inhibits

proliferation and induces apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells

by repressing p21WAF1/Cip1 transcription and cyclin

D1-Cdk4-p21WAF1/Cip1 complex formation. J Biol Chem.

278:32537–32543. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Nasiri-Ansari Ν, Dimitriadis GK,

Agrogiannis G, Perrea D, Kostakis ID, Kaltsas G, Papavassiliou AG,

Randeva HS and Kassi E: Canagliflozin attenuates the progression of

atherosclerosis and inflammation process in APOE knockout mice.

Cardiovasc Diabetol. 17(106)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Terzuoli E, Nannelli G, Giachetti A,

Morbidelli L, Ziche M and Donnini S: Targeting

endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: The protective role of

hydroxytyrosol sulfate metabolite. Eur J Nutr. 59:517–527.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Viedma-Rodríguez R, Martínez-Hernández MG,

Martínez-Torres DI and Baiza-Gutman LA: Epithelial mesenchymal

transition and progression of breast cancer promoted by diabetes

mellitus in mice are associated with increased expression of

glycolytic and proteolytic enzymes. Horm Cancer. 11:170–181.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Paapstel K, Zilmer M, Eha J, Tootsi K,

Piir A and Kals J: Association between Fibulin-1 and aortic

augmentation index in male patients with peripheral arterial

disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 51:76–82. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Nguyen AD, Itoh S, Jeney V, Yanagisawa H,

Fujimoto M, Ushio-Fukai M and Fukai T: Fibulin-5 is a novel binding

protein for extracellular superoxide dismutase. Circ Res.

95:1067–1074. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Orriols M, Varona S, Martí-Pàmies I, Galán

M, Guadall A, Escudero JR, Martín-Ventura JL, Camacho M, Vila L,

Martínez-González J and Rodríguez C: Down-regulation of Fibulin-5

is associated with aortic dilation: role of inflammation and

epigenetics. Cardiovasc Res. 110:431–442. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Sarvagalla S, Kolapalli SP and

Vallabhapurapu S: The two sides of YY1 in cancer: A friend and a

foe. Front Oncol. 9(1230)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Makhlouf M, Ouimette JF, Oldfield A,

Navarro P, Neuillet D and Rougeulle C: A prominent and conserved

role for YY1 in Xist transcriptional activation. Nat Commun.

5(4878)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Cai Y, Jin J, Yao T, Gottschalk AJ,

Swanson SK, Wu S, Shi Y, Washburn MP, Florens L, Conaway RC and

Conaway JW: YY1 functions with INO80 to activate transcription. Nat

Struct Mol Biol. 14:872–874. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wei SY, Shih YT, Wu HY, Wang WL, Lee PL,

Lee CI, Lin CY, Chen YJ, Chien S and Chiu JJ: Endothelial Yin Yang

1 phosphorylation at S118 induces atherosclerosis under flow. Circ

Res. 129:1158–1174. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Jian D, Dai B, Hu X, Yao Q, Zheng C and

Zhu J: ox-LDL increases microRNA-29a transcription through

upregulating YY1 and STAT1 in macrophages. Cell Biol Int.

41:1001–1011. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Guo J, Xiang Q, Xin Y, Huang Y, Zou G and

Liu T: miR-544 promotes maturity and antioxidation of stem

cell-derived endothelial like cells by regulating the YY1/TET2

signalling axis. Cell Commun Signal. 18(35)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Qin L, Yang YB, Yang YX, Gong YZ, Li XL,

Li GY, Luo HD, Xie XJ, Zheng XL and Liao DF: Inhibition of smooth

muscle cell proliferation by ezetimibe via the cyclin D1-MAPK

pathway. J Pharmacol Sci. 125:283–291. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Vadiveloo PK, Filonzi EL, Stanton HR and

Hamilton JA: G1 phase arrest of human smooth muscle cells by

heparin, IL-4 and cAMP is linked to repression of cyclin D1 and

cdk2. Atherosclerosis. 133:61–69. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhang Y, Li YH, Liu C, Nie CJ, Zhang XH,

Zheng CY, Jiang W, Yin WN, Ren MH, Jin YX, Liu SF, et al: miR-29a

regulates vascular neointimal hyperplasia by targeting YY1. Cell

Prolif. 50(e12322)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|