Introduction

Lung cancer is the most prevalent and lethal

malignancy in the world, with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) being the

predominant pathological subtype (1). Despite significant advances in early

diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, the 5-year overall survival

(OS) rate remains <20% (2).

Platinum-based chemotherapy is currently the most important

adjuvant therapy for patients with advanced lung cancer (3). However, adverse reactions and drug

resistance limit the ultimate efficacy of chemotherapy (4). Therefore, novel strategies are in

demand to supplement conventional therapeutic strategies (5). Over the past decade, knowledge on the

molecular features of cancer has been steadily accumulating thanks

to advances in genomic technology (6). Consequently, the preferred treatment

strategy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer is shifting from

traditional histopathology-based chemotherapy to individualized and

precise treatment regimens based on oncogenic factors (7). Although the biomarkers and

therapeutic targets previously identified have contributed to the

diagnosis and treatment of LUAD, a demand remains for novel genetic

data for optimizing treatment protocols due to its biological

complexity and poor prognosis (8).

To explore common biomarkers associated with cancer that can be

used for treatment, diagnosis and assessment of prognosis, large

quantities of cancer microarray and high-throughput sequence data

has been reported and become available over recent years (8,9). In

addition, to overcome the limitations caused by small sample sizes,

differential platform data and standards, bioinformatics are

becoming increasingly popular in the field of cancer biology, which

have yielded valuable information (8).

Cyclins are a class of proteins that control cell

cycle progression by activating CDK enzymes (10). The cyclin gene family is comprised

of 31 members according to the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee

(https://www.genenames.org/data/genegroup/#!/group/473).

Through bioinformatics technology, it was found that certain genes

in certain cyclin families are significantly overexpressed in LUAD,

but there is a lack of further experiments to verify their

expression and specific molecular mechanisms (11). Although numerous studies have

previously reported that cyclins serve important roles in the

development of a variety of tumors (12,13),

the specific genes in the cyclin family that are associated with

the development of LUAD remain largely unexplored.

Based on the RNA microarray data of GSE33532,

GSE40791 and GSE19188, the present study used bioinformatics

methods to search for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between

LUAD and adjacent normal lung tissue. A protein-protein interaction

(PPI) network was then established to screen for key genes enriched

in the cyclin gene family. Online databases were implemented to

validate the expression, PPI and clinical relevance of the hub

genes. The purpose of the present study was to search for genes in

the cyclin family that are associated with LUAD in addition to

their potential upstream regulators. It is anticipated that this

information could reveal potential targets for subsequent

experimental validation.

Materials and methods

Microarray data source

In the present study, the microarray datasets were

searched and downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) using

the following criteria: i) Choose Affymetrix array under GPL570

platform; ii) the tissue source was from human LUAD samples and

adjacent normal samples; and iii) study containing ≥20 LUAD and 20

normal samples. Finally, three datasets based on the GPL570

platform were selected, namely GSE19188, GSE33532 and GSE40791.

Specifically, GSE19188 included 40 LUAD samples and 65 adjacent

normal lung tissue samples (14),

whereas GSE33532 included 40 LUAD samples and 20 adjacent normal

lung tissue samples (15).

GSE40791 included 94 LUAD samples and 100 adjacent normal lung

tissue samples (16).

Microarray data analysis

The gene expression matrix and associated annotation

files of the three aforementioned datasets were downloaded from the

GEO database before the probe matrix in the expression profiling

following the array was converted into a gene matrix through ‘affy’

package of R software (17). Under

the R environment (version 4.0.3; https://www.r-project.org/), using the ‘affy’ package

(17), the raw gene expression

matrix was background corrected and normalized and the ‘limma’

package (18) was used to screen

out the DEGs between the LUAD and normal samples |log2

fold change|>1 and P<0.05 were applied as the threshold for

this screen.

Screening DEGs using robust rank

aggregation (RRA) analysis

The RRA method is a tool that can be used for

integrating data from multiple microarray studies with minimal

inconsistencies to robustly identify DEGs (19,20).

First, a list of the upregulated DEGs and downregulated DEGs by

fold change in expression between the LUAD and normal samples was

obtained from each dataset. Using the ‘RRA’ package (19), all lists of ranked genes from each

dataset were integrated. Genes with an adjusted score <0.05 were

significant DEGs.

Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto

encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis

Enrichment analysis of GO and KEGG has been

extensively utilized for deciphering microarray data to further

understanding into the biological functions of each gene (21). In the present study, the

‘ClusterProfiler’ package (22)

was used to analyze the GO and KEGG enrichment of the DEGs under

the R environment (version 4.0.3).

PPI network establishment and module

identification

Using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of

Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING; https://cn.string-db.org/, version 11.5) (23), a PPI network of DEGs was

constructed to predict interactions among the proteins. A

comprehensive score threshold ≥0.4 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant interaction. In addition, the Cytoscape

software (version 6.3; http://www.cytoscape.org/) (24) was used to further analyze and

visualize the PPI network. Within Cytoscape, the ‘NetworkAnalyzer’

plugin was used to analyze the PPI network, whereas the ‘MCODE’

plugin was used to screen the functional module (25,26).

The parameters set for screening the function module were as

follows: MCODE score >5; degree cut-off=2; node score

cut-off=0.2; Max depth=100; and k-score=2.

Screening for hub genes through

co-expression and external databases

The enriched gene family was selected according to

the gene module screened by Cytoscape. An expression correlation

matrix was then made for the family genes in the three datasets,

before genes with high positive correlation (R>0.6; P<0.05)

were selected to be key genes according to Pearson's methods.

Subsequently, three datasets (GSE33532, GSE40791 and

GSE19188) and the Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA; http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/GSCA/#/)

database were utilized to verify the expression of the key genes.

The Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA;

http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) database was

used to assess the correlation in the expression of key genes,

which genes that sufficiently correlate with each other (R>0.7;

P<0.001) were selected as hub genes (27). The BioCarta (https://maayanlab.cloud/Harmonizome/) database was

used to screen for the commonly predicted upstream transcription

factors of the hub genes (28).

Key genes in the cyclin family and their predicted upstream

transcription factors were the ultimate hub genes of the present

study.

Identifying and analyzing the hub

genes

In the present study, the UALCAN database

(http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) (29) was used to compare the expression of

hub genes in LUAD samples and normal samples, in addition to

assessing the association between the expression of hub genes and

tumor stage and prognosis of patients with LUAD. In addition, the

GEPIA database was used for the OS analysis of hub genes to explore

their prognostic values (27).

Cells and cell culture

The LUAD cell line Beas-2B was cultured in

high-glucose DMEM medium (cat. no. 23-10-013-CV; Corning, Inc.),

the LUAD cell line A549 was cultured in high-glucose F12K medium

(cat. no. 21127022; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the human

bronchial epithelial cell line 16-HBE and LUAD cell line H1299 cell

line were cultured in high-glucose RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no.

10-040-CV; Corning, Inc.). All mediums contained 10% FBS (cat. no.

10091148; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin and cells were incubated

routinely in a cell incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37˚C.

The three cell lines were purchased from FuHeng Cell Center

(https://www.fudancell.com/). Cells at

logarithmic growth phrases were used for subsequent

experiments.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

According to the manufacturer's protocol, the

TRIzol® reagent (cat. no. 15596026; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to isolate total RNA from the 16-HBE,

A549, Beas-2B and H1299 cells. Reverse transcription was performed

using super script first strand synthesis system cat. no. 18080051;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with oligo (DT) 20

primer and 5.0 µg RNA to synthesize the first strand of cDNA. Using

GAPDH as the endogenous control, the primers were synthesized by

Beijing Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Primer sequences are

provided in Table SI. Master qPCR

mix (2X TSINGKE® SYBR Green I; cat. no. 4367659;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to detect

mRNAs level according to the manufacturer's protocol (initial

denaturation: 95˚C for 3 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation

at 95˚C for 10 sec, annealing at 55˚C for 10 sec and extension at

72˚C for 30 sec.). Application of the 2-ΔΔCq method was

used to calculate the relative expression level of mRNA (30).

Western blot analysis

The protein samples lysate for western blot were

collected from 16-HBE, Beas-2B, A549 and H1299 cell lines with RIPA

lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

containing protease inhibitor cocktail. Concentrations of protein

samples were detected using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no.

A53225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 20 µg protein lysate

was loaded in 10% SDS-PAGE gel respectively and transferred to PVDF

membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). After blocking in 5% non-fat

milk dissolved in TBST buffer for 60 min at room temperature, the

membranes were washed 3 times by TBST containing 1% Tween 20 (cat.

no. P1379; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and then incubated with the

following 5% BSA-diluted (cat. no. ST2254; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) primary antibodies: CCNA2 (1:1,000; cat. no.

18202-1-AP), CCNB1 (1:1,000; cat. 28603-1-AP), CCNB2 (1:1,000; cat.

no. 21644-1-AP; all from ProteinTech Group, Inc.) and ACTB

(1:10,000; cat. no. AC026; Abclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 6-8 h at

4˚C; the HRP-linked secondary antibodies (1:20,000; cat. no.

SA00001-2; ProteinTech Group, Inc.) were used to probe the primary

antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the immunoreactive

protein bands were visualized by ECL kit (cat. no. WBKLS0500;

MilliporeSigma), and the images were obtained by scanning using a

fluorescence imager (Typhoon FLA 7000; Cytiva). The quantification

of blot bands was calculated using ImageJ (Version. 1.52; National

Institutes of Health).

Immunohistochemistry of hub genes

In total, 10 pairs of LUAD and adjacent normal

tissues were collected from the Second Hospital of Shandong

University (Jinan, China) from 2021/01/01 to 2021/12/31, with

complete pathological data. The age of the patients was 61.2±6.3

years, including 4 women and 6 men. The present study was approved

[approval no. KYLL-2020(KJ)P-0099] by the Medical Ethics Committee

of the Second Hospital of Shandong University (Jinan, China).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The

human LUAD specimens were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded for

24 h at 4˚C and cut into 4-µm thin slices. The IHC staining kit

(cat. no. PV-6000; ZSGB-BIO) was used for the experiment according

to the manufacturer's instructions. DAB (cat. no. ZLI-9017;

ZSGB-BIO) was used for staining (37˚C for 90 sec). The final

immunostaining images were obtained using a NanoZoomer Digital

Pathology scanner (NanoZoomer S60; Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.).

Protein expression was analyzed by calculating the integrated

optical density (IOD/area) of each stained region using Image-Pro

Plus version 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Diagnostic model and evaluation of hub

genes

To evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of the hub genes

for LUAD, the three data sets GSE33532, GSE40791 and GSE19188 were

combined. The raw expression data were then normalized by Affy

package (17) using robust

multi-array average (RMA), before the inter-batch differences were

removed and the data were integrated into a large expression

matrix. The percentage of normal tissue in all samples was

calculated, and the cut-off value was selected according to the

percentage of normal tissue in the sample. Those whose expression

value was higher than the cut-off value were regarded as high

expression samples, and those whose expression value was lower than

the cut-off value were regarded as low expression samples. The

expression of samples was converted from numerical variables to

factor variables for subsequent analysis. This integrated

expression matrix was used as the training set. To verify the

diagnostic efficacy, two external datasets were also selected,

namely GSE10072(31) and

GSE75037(32) for external data

validation. GSE10072 belongs to the same GPL570 platform as the

three datasets used for the training set. The raw data of GSE10072

were analyzed after RMA normalization. By contrast, the GSE75037

dataset belongs to the GPL6884 platform. To verify the

applicability of the data from other platforms, the matrix

expression data from this dataset were chosen for analysis. The

training set contains 179 LUAD samples and 185 normal tissue

samples in total. The external validation set GSE10072 contains 58

LUAD samples and 49 normal tissue samples. The external validation

set GSE75037 contains 83 LUAD samples and 83 normal tissue

samples.

MASS package (33)

and glm function (34) were used

for forward stepwise logistic regression analysis of hub gene, and

the appropriate genes were selected and included into the effect

variables. Then glm function was used to conduct logistic

regression analysis on the key genes included in the effect

variables. Finally, rms package (35) was used to construct nomograph of

regression analysis results.

A ROC curve for this model was constructed using the

‘pROC package’ (36). ROC curves

were generated for the training set and two validation sets to

distinguish patients with LUAD from healthy individuals. Area under

the ROC curve (AUC) and confidence intervals were calculated to

assess the predictive values of the selected hub genes for LUAD

diagnosis. Finally, the diagnostic efficacy of the nomograms was

evaluated further and validated using calibration plots and

decision curve analysis (DCA) plots through rms package (35).

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed using SPSS

25.0 (IBM Corp.). The Pearson correlation coefficient between

cyclin family genes was calculated using R (https://www.R-project.org/). In the GEPIA database,

Pearson's method was used to analyze the expression correlation

between hub genes in TCGA datasets. GEPIA used the Kaplan-Meier

method to estimate the OS associated with gene expression levels.

GEPIA uses the Mantel-Cox test for hypothesis testing. The cox

proportional hazard ratio and the 95% confidence interval

information are shown in the survival plot. One-way ANOVA was used

to analyze whether the results of western blotting and RT-qPCR were

statistically different. In the multiple comparisons post hoc test,

Dunnett's test was used to compare the non-small cell lung cancer

cell lines A549, Beas-2B and H1299 with the control cell line

16-HBE, respectively. In the results of immunohistochemical study,

paired t-test was used to analyze whether the staining results of

hub gene in normal adjacent tissues and tumor tissues were

statistically different. The significance of the difference between

the two groups was estimated by UALCAN using the t-test, but the

statistical analysis method used for the comparison of multiple

groups was not described. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

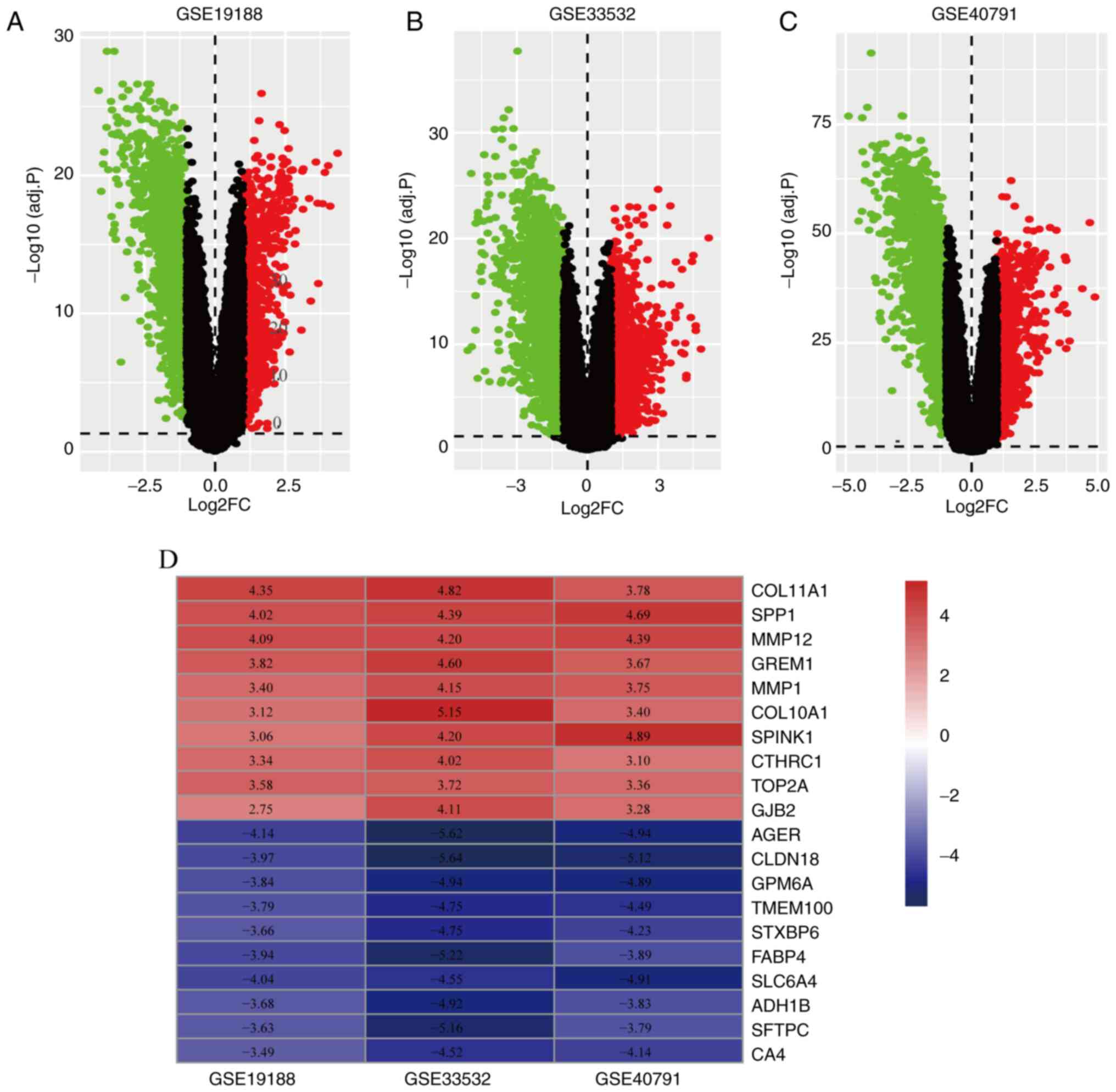

Analysis of LUAD microarray data

In the present study, GSE19188, GSE33532 and

GSE40791 were included for analysis, with a total of 179 LUAD

samples and 185 normal samples. These three microarray datasets

were first standardized by quantiles to mitigate individual

differences among samples. A total of 1,883, 3,079 and 2,258 DEGs

were screened from the GSE19188, GSE33532 and GSE40791 datasets,

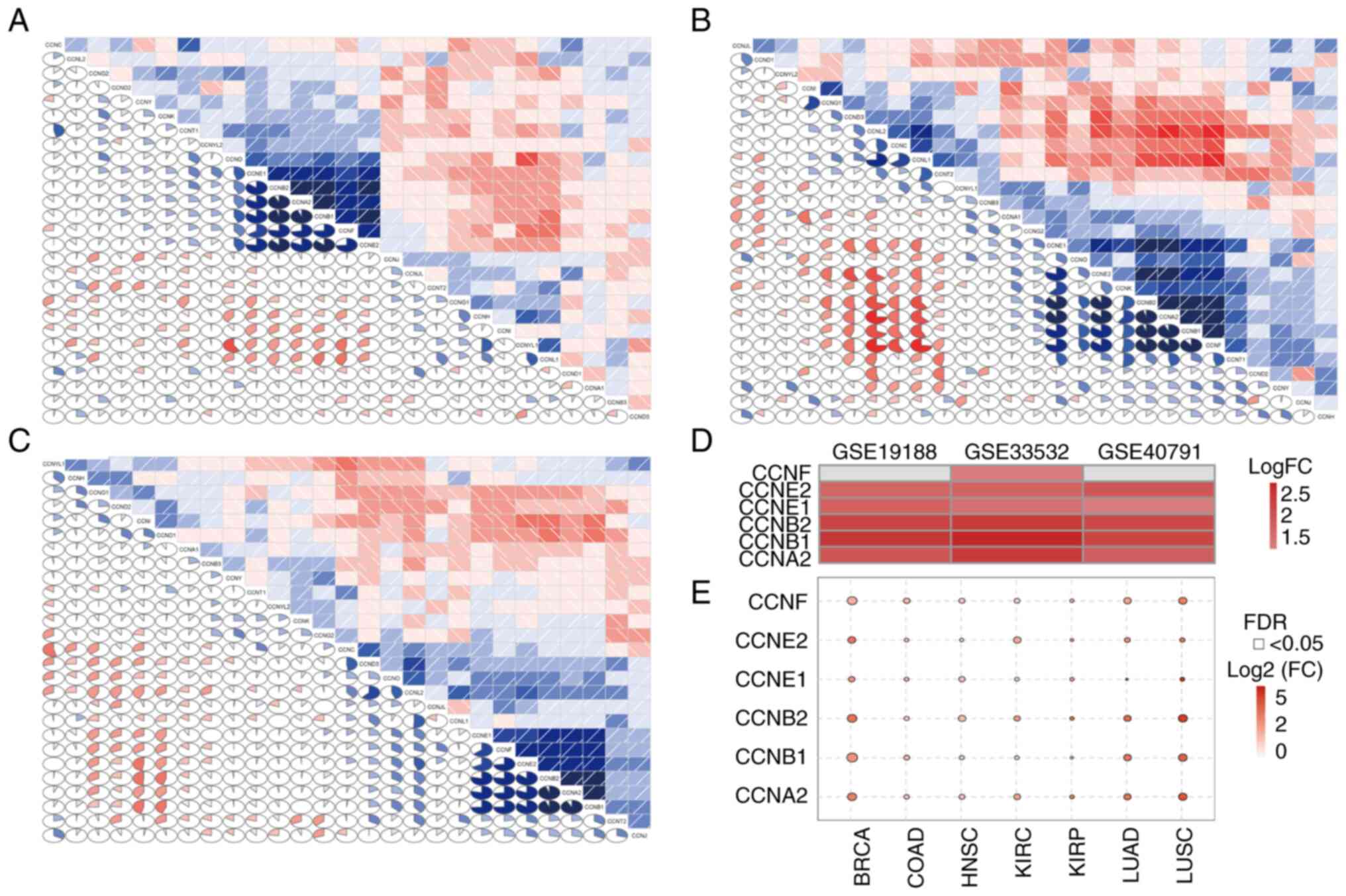

respectively (Fig. 1A-C).

RRA-integrated analysis and

identification of DEGs

The RRA method assumes that the number of ranked

each gene is known (19). The

smaller the RRA score, the higher the gene ranks in term of the

credibility of differential expression. Finally, 556 significant

DEGs were screened by the integrated analysis, including 203

significantly upregulated genes and 353 significantly downregulated

genes. A heatmap containing the top 10 up- and downregulated genes

is shown in Fig. 1D.

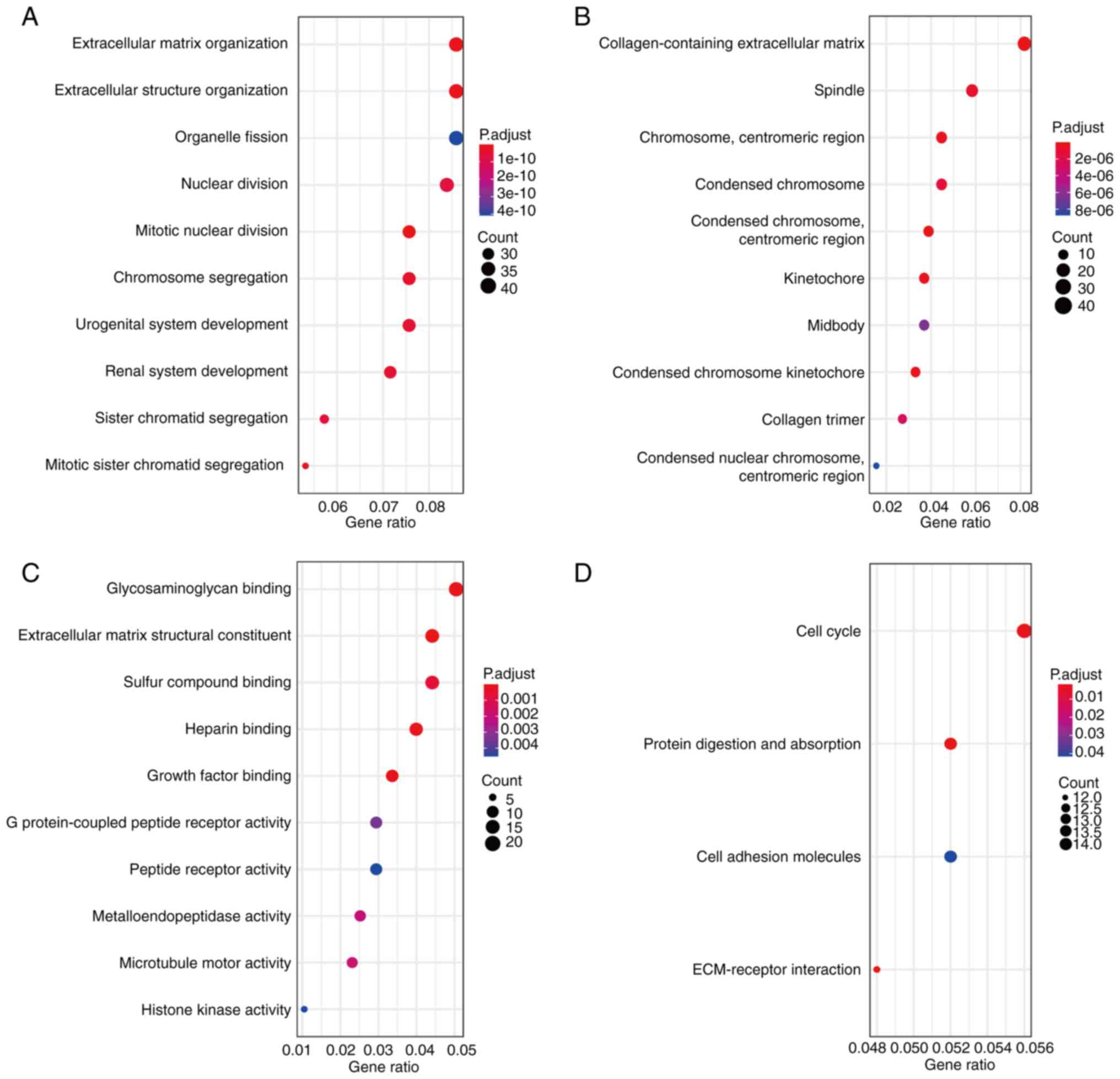

Functional and pathway enrichment

analysis of the DEGs

GO analysis revealed that biological processes of

the significant DEGs were associated with the cell cycle, including

‘mitotic nuclear division’, ‘extracellular matrix organization’,

‘extracellular structure organization’, ‘mitotic sister chromatid

segregation’ and ‘chromosome segregation’ (Fig. 2A). Significantly enriched cellular

components included ‘collagen-containing extracellular matrix’,

‘condensed chromosome’ and ‘centromeric region’ (Fig. 2B). In addition, the molecular

functions that were significantly enriched include ‘extracellular

matrix structural constituent’, ‘glycosaminoglycan binding’ and

‘growth factor binding’ (Fig. 2C).

KEGG analysis revealed that DEGs were significantly enriched in

‘ECM-receptor interaction’, ‘protein digestion and absorption’,

‘cell cycle’ and ‘cell adhesion molecules’ (Fig. 2D).

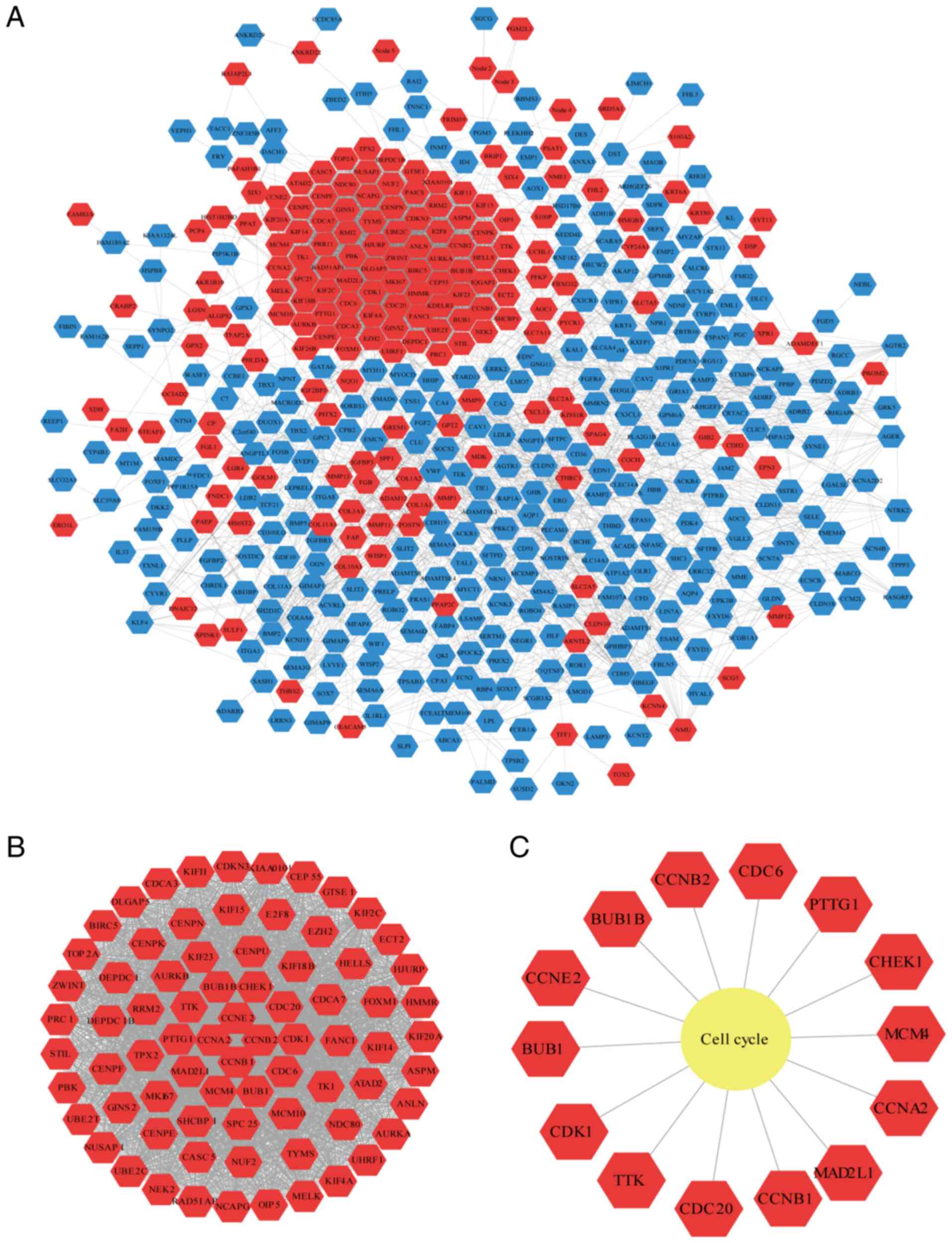

PPI network of DEGs and module

identification

A total of 499 nodes and 4,311 edges were found in

the PPI network (Fig. 3A). Using

the ‘Networkanalyzer’ plugin, the basic parameters of the PPI

network were obtained, where the clustering coefficient was 0.342,

the network density was 0.035 and the network centralization was

0.147. Using the Cytoscape plugin ‘MCODE’, the most critical module

was acquired from the PPI network, which contains 76 nodes and 2631

edges (Fig. 3B). The most

significantly enriched pathway for module 1 is cell cycle (Fig. 3C).

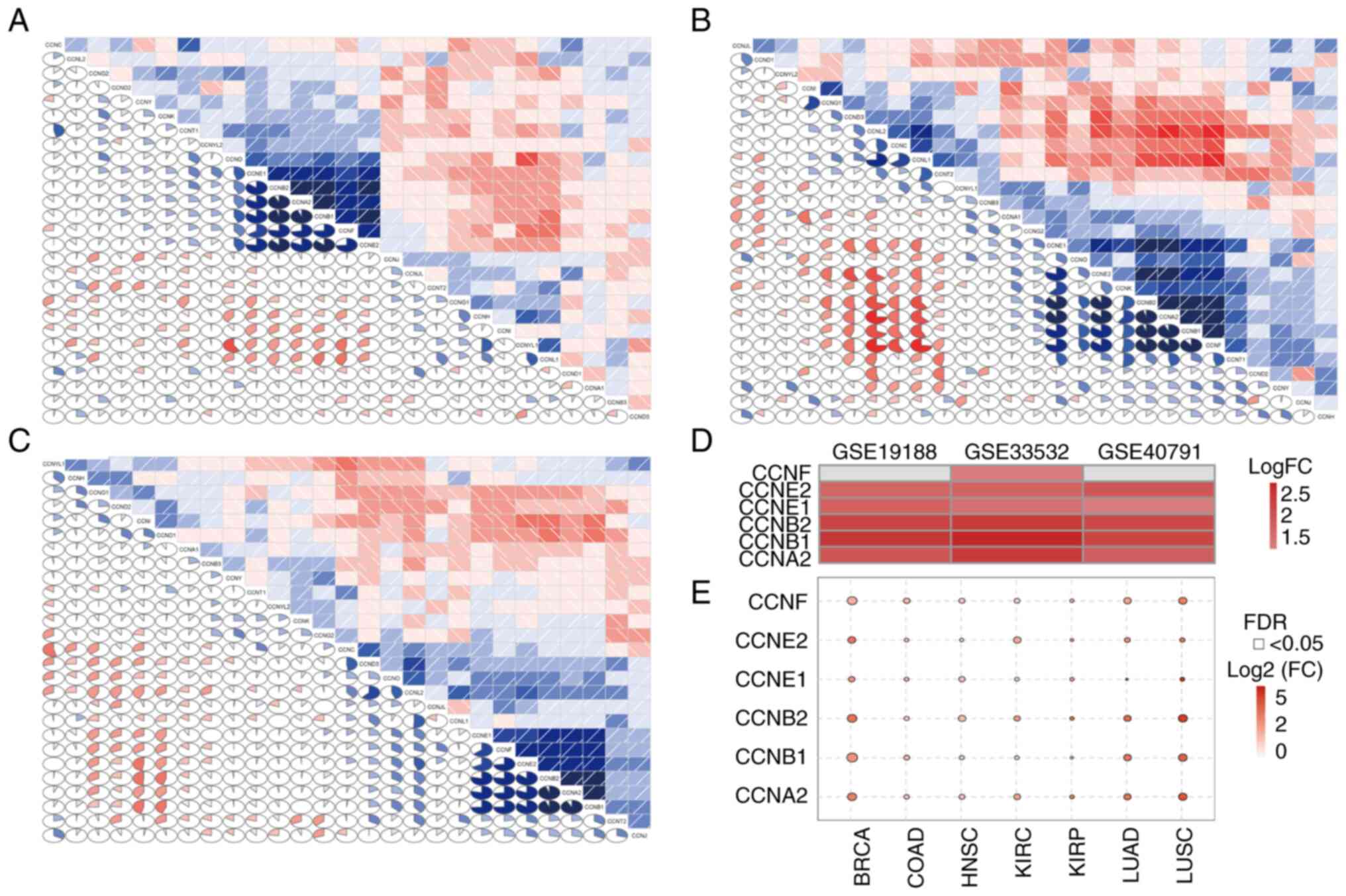

Screening for key genes in the cyclin

family

A total of four cyclin family genes (CCNA2, CCNB1,

CCNB2 and CCNE2) were clustered in module 1. To analyze the cyclin

family genes, a cyclin family gene expression correlation matrix

was made for the three datasets. The results revealed that

CCNE1, CCNE2, CCNB1, CCNB2,

CCNA2 and CCNF correlated with each other (Fig. 4A-C). The expression of six cyclin

family genes was then analyzed in the three datasets: CCNE1, CCNE2,

CCNB1, CCNB2 and CCNA2 were all highly expressed in the three data

sets, while CCNF was only highly expressed in GSE33532, while there

was no significant difference in the other two data sets (Fig. 4D). The expression profile of

CCNE1, CCNE2, CCNB1, CCNB2,

CCNA2 and CCNF was subsequently analyzed in various

tumors using the GSCA database. It was found that the expression of

most if not all the genes examined were upregulated in multiple

human tumors, including LUAD, breast and colon cancer (Fig. 4E).

| Figure 4Cyclin family gene expression

profile. Correlation matrix of the expression levels of all genes

in the cyclin family in the (A) GSE19188, (B) GSE33532 and (C)

GSE40791 datasets. (D) Expression of sex cyclin family genes

(CCNE1, CCNE2, CCNB1, CCNB2,

CCNA2 and CCNF) in the three datasets. (E) Expression

of sex cyclin family genes in various tumors according to the Gene

Set Cancer Analysis database. BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma;

COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; KIRP, kidney

renal papillary cell carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC,

lung squamous cell carcinoma. |

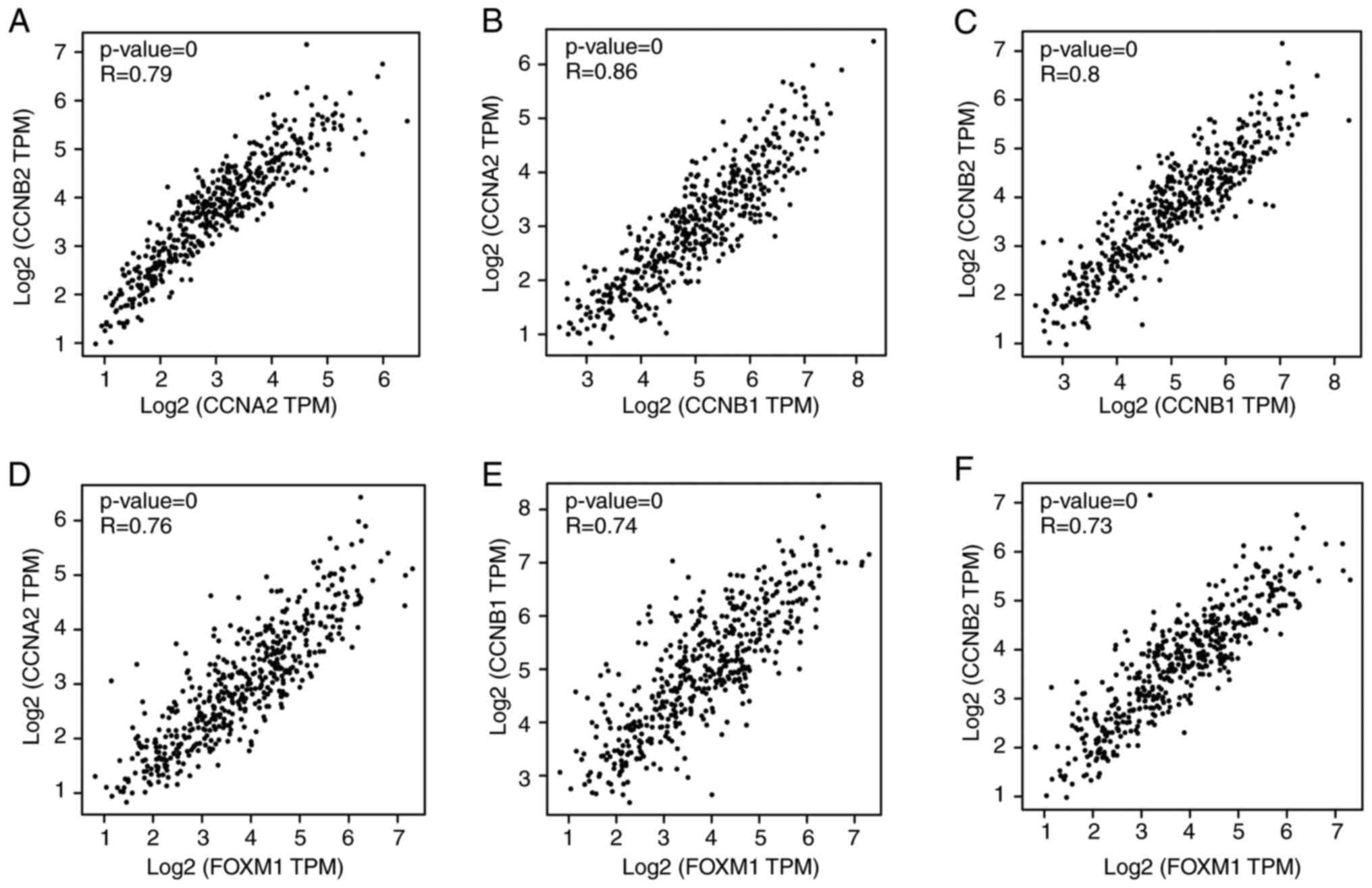

Analysis of hub gene

co-expression

To investigate the correlation in the expression of

the six cyclin family genes, the GEPIA online tool was used to

obtain the Pearson's rank coefficient results among these genes.

According to the pairwise gene expression correlation analysis,

GEPIA revealed significant positive correlation among CCNB1,

CCNB2 and CCNA2 expression (Fig. 5A-C). The BioCarta database was next

used to screen for possible upstream transcription factors of

CCNB2, CCNB1 and CCNA2. FOXM1 was

predicted to be their common upstream transcription factor. In

addition, FOXM1 was also found to be an upregulated gene

clustered in module 1 (Fig. 3B).

According to the GEPIA database, FOXM1 also appeared to be a

co-expressed gene with the three cyclins (Fig. 5D-F). Therefore, these four genes

were chosen to be hub genes for further verification.

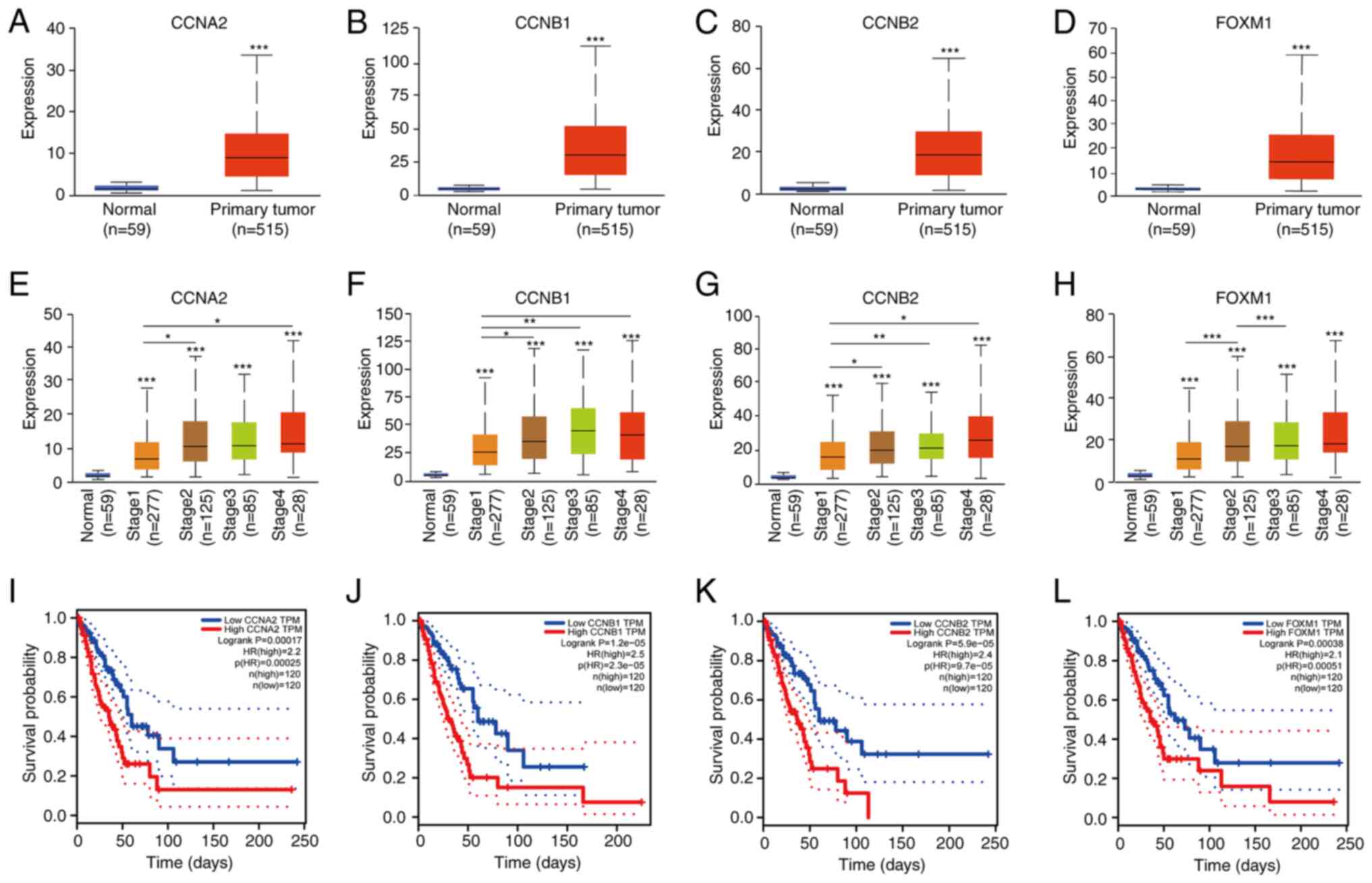

Expression of hub genes and their

prognostic value

The UALCAN database is based on The Cancer Genome

Atlas data (29). Therefore, this

online tool was used to assess the expression profile of the hub

genes. The expression of these hub genes was found to be higher in

the LUAD samples compared with that in the normal samples (Fig. 6A-D). The association between hub

gene expression and tumor stage was next assessed (Fig. 6E-H). All four hub genes were

revealed to be expressed in tumors of different stages, but the

levels were higher in advanced LUAD compared with those in their

early-stage counterparts. The GEPIA website was next used to assess

the prognostic value of these hub genes in the clinical setting,

where a total of 240 patients with LUAD were included from the

database available for overall survival (OS) analysis. Higher

expression of all these hub genes was associated with more

unfavorable OS among patients with LUAD (Fig. 6I-L).

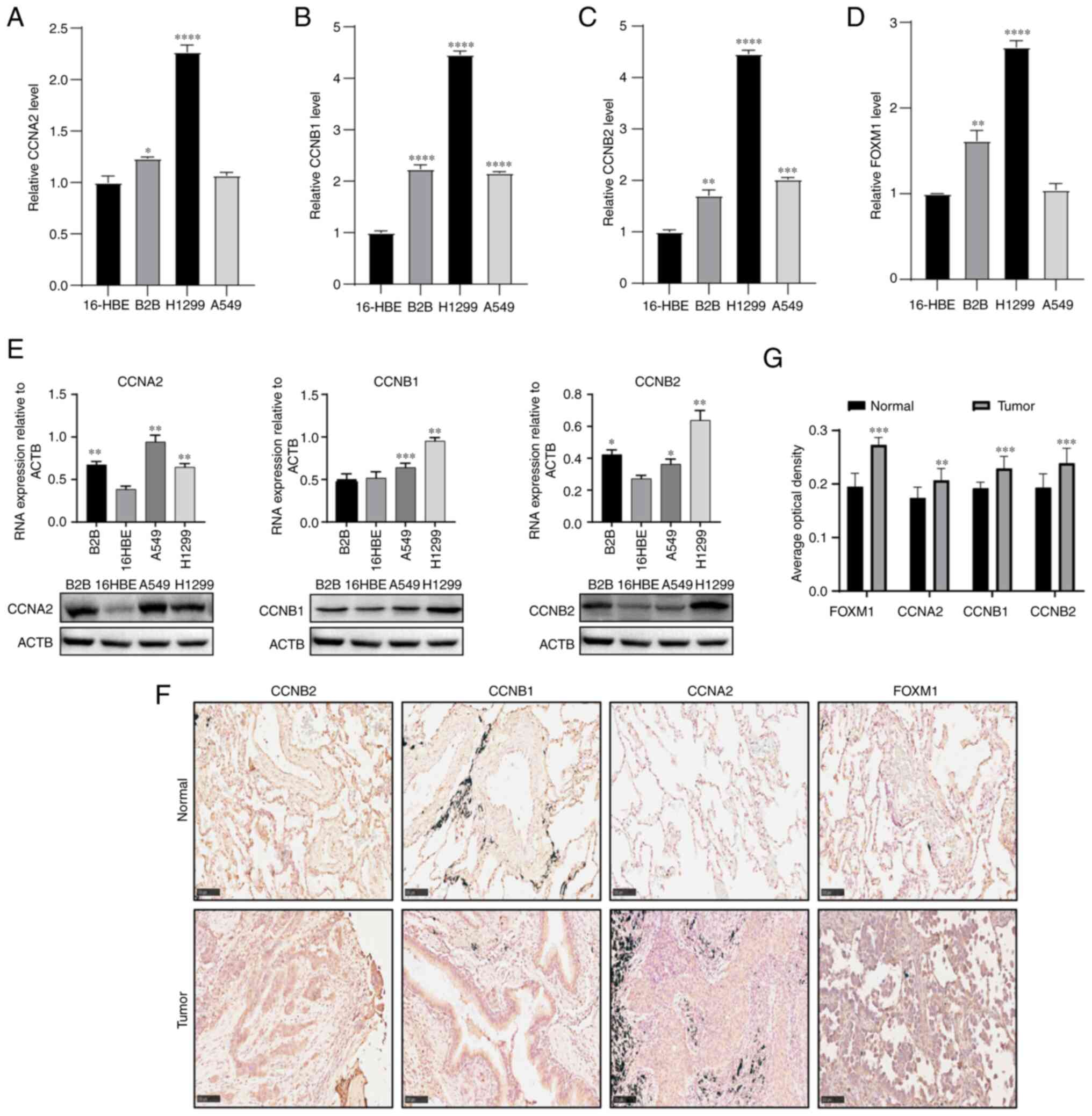

Validation of hub gene expression in

vitro

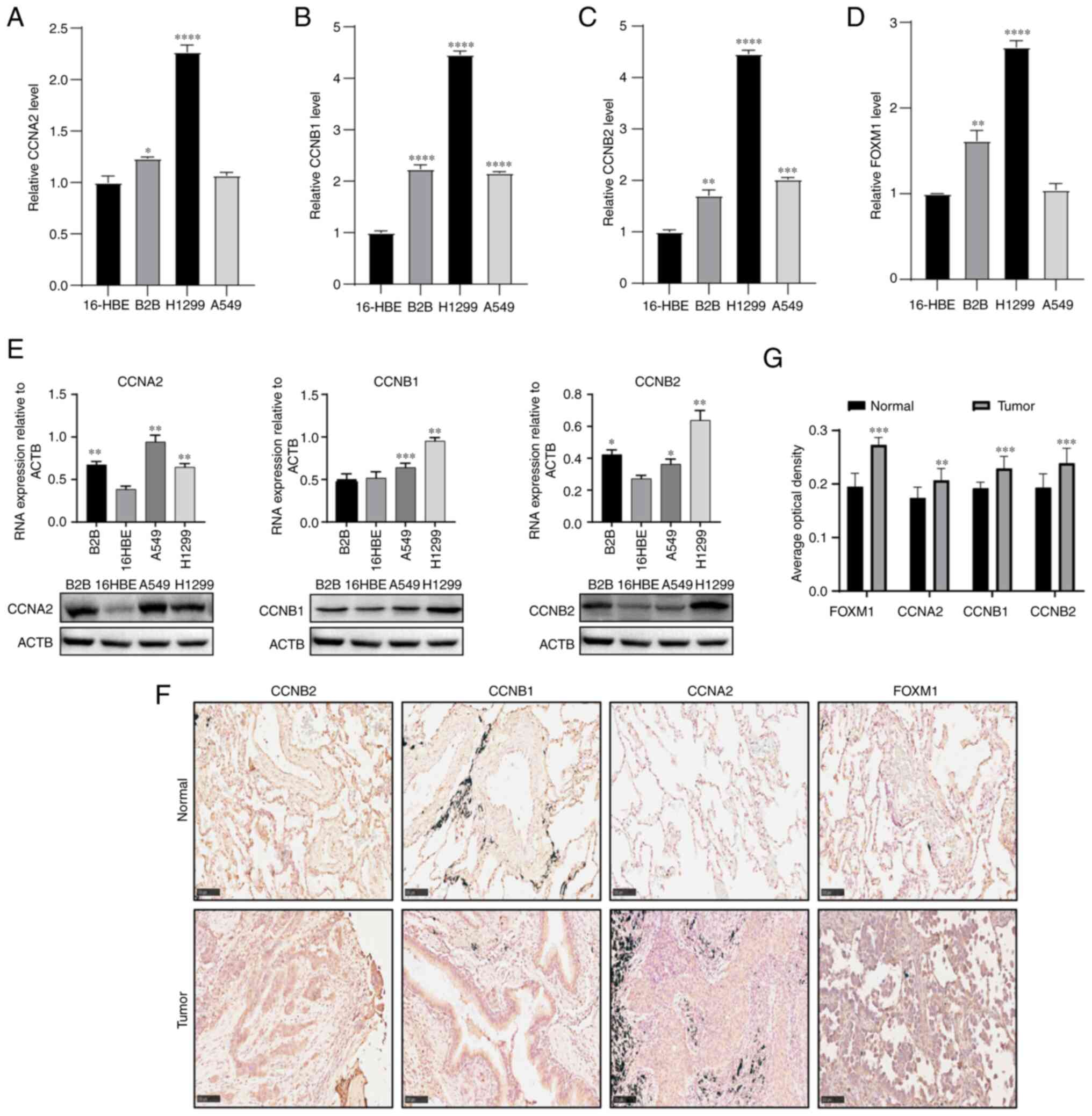

RT-qPCR was used to verify the mRNA expression

levels of these genes in the cell lines. The results showed that

the mRNA expression of the hub genes was significantly higher in

the two non-small cell lung cancer cell lines Beas-2B and H1299

compared with human bronchial epithelial cell line 16-HBE, and the

expression of four hub genes was upregulated in A549 cell line, in

which there was a significantly high expression in CCNB1 and CCNB2

(Fig. 7A-D, Table SII, Table SIII, Table SIV and Table SV). Subsequently, western blotting

revealed that the CCNA2, CCNB1 and CCNB2 were also highly expressed

in the three non-small cell lung cancer cell lines A549, Beas-2B

and H1299 compared with human bronchial epithelial cell line 16-HBE

(Fig. 7E, Table SVI, Table SVII and Table SVIII). According to the

immunohistochemistry staining images of the hub genes in 10 pairs

of human LUAD tissues and adjacent normal tissues, their expression

in tumors was found to be significantly higher compared with that

in the adjacent normal tissues (Fig.

7F-G).

| Figure 7Expression of hub genes in LUAD cells

and tissues. The expression levels of (A) CCNA2, (B) CCNB1, (C)

CCNB2 and (D) FOXM1 mRNA in the non-small cell lung cancer cell

lines A549, Beas-2B and H1299 and the control cell line 16-HBE were

validated by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (E) Western

blot analysis was used to detect the expression of CCNA2, CCNB1 and

CCNB2 in LUAD cell lines; ACTB was used as loading control. Each

column represents the mean ± SD from independent experiment. (F)

Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze the expression of hub

genes in LUAD and adjacent normal tissues (magnification, x200;

scale bar, 100 µm). (G) Image-Pro Plus version 6.0 was used to

calculate the integral optical density/area and analyze the hub

gene protein expression level. Statistical analysis of results in

panels A-E was performed using one-way ANOVA, and comparisons

between groups were performed using Dunnett's test. Statistical

analysis of results in panel F was performed using t-test.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 compared

with 16-HBE. LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; CCN, cyclin. |

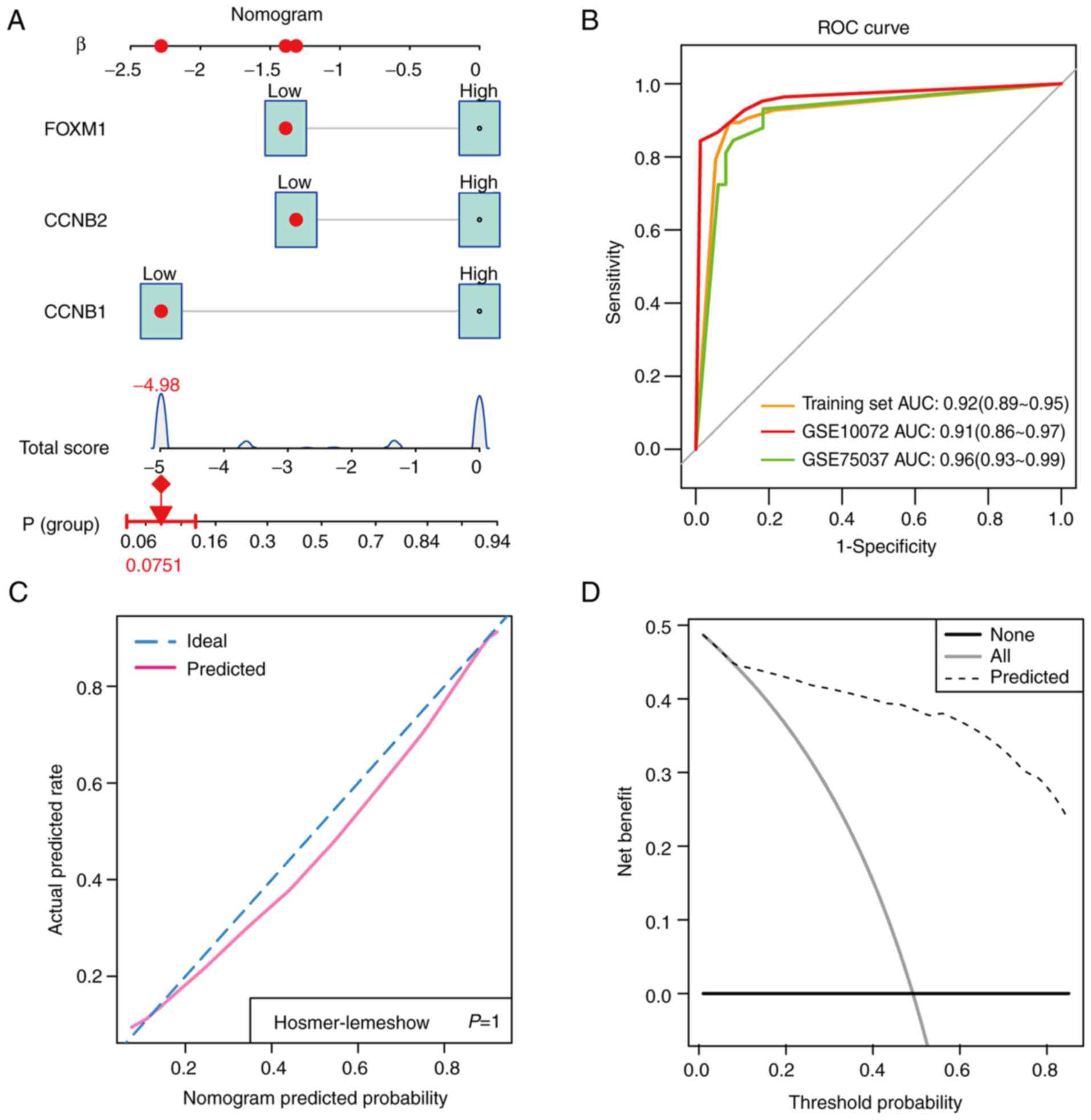

Diagnostic model and evaluation of hub

genes

The diagnostic efficacy of all hub genes was

assessed by constructing multi-factorial logistic regression models

from the training set, where CCNB1, CCNB2 and

FOXM1 were statistically significant (Table SIX). CCNB1, CCNB2

and FOXM1 were analyzed further after their inclusion as

possible effect variables (Table

SX). All hub genes were found to be statistically

significant.

Since the expression levels of CCNB1,

CCNB2 and FOXM1 appeared to be predictors of LUAD,

the nomogram plots were constructed to assess their diagnostic

efficacy (Fig. 8A). ROC analysis

was subsequently applied to evaluate the potential diagnostic value

of these hub genes in LUAD. The results showed that CCNB1,

CCNB2 and FOXM1 had AUC values of 0.92 (95%

confidence interval=0.89-0.95) in the training set, 0.91 (95%

confidence interval=0.86-0.97) in the GSE10072 validation set for

the diagnosis of LUAD and 0.96 (95% confidence interval=0.93-0.99)

in the GSE75037 validation set (Fig.

8B). This suggested that CCNB1, CCNB2 and

FOXM1 are viable biomarkers for LUAD diagnosis (Fig. 8B). The calibration plot also

revealed consistent predictive accuracy for the diagnosis of LUAD

using the hub genes (Fig. 8C). DCA

plot results revealed that clinical benefit could be obtained by

developing clinical strategies based on this nomogram (Fig. 8D).

Discussion

Dysregulation in cell cycle control can lead to

tumor progression. Cyclins are cell cycle regulators that are

associated with numerous types of cancer (12,13).

However, it remains unclear the role and possible regulatory

mechanism of cyclins in LUAD.

In the present study, expression profiling and

functional enrichment analysis revealed that four significant DEGs,

namely CCNA2, CCNB1, CCNB2 and CCNE2,

were highly expressed in module 1. An expression correlation matrix

containing 31 cyclin family genes in three datasets also showed

that six genes (CCNE1, CCNE2, CCNB1,

CCNB2, CCNA2 and CCNF) are significantly

co-expressed. Further analysis of their expression in the datasets

and pan-tumor data demonstrated that they were significantly

overexpressed in a variety of tumors, such as breast cancer and

colon cancer. Further co-expression analysis also revealed that the

correlation among the expression levels of CCNA2,

CCNB1 and CCNB2 was particularly striking. In

addition, FOXM1 was predicted to be their upstream

transcription factor according to the BioCarta database, where the

co-expression results reported significant co-expression between

FOXM1 and the three cyclin family genes. Since further study

revealed that FOXM1 was also enriched in module 1, it was included

as one of the hub genes for further analysis and validation.

Using online databases, the high expression of hub

genes was found in LUAD. Furthermore, the expression of

CCNA2, CCNB1, CCNB2 and FOXM1 was found

to be higher in patients with advanced LUAD compared with that with

early-stage LUAD. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that patients with

higher levels of hub gene expression had poorer prognoses,

suggesting that they are viable prognostic indicators of LUAD. In

terms of biological function, the hub genes were enriched in the

cell cycle, DNA damage, DNA repair, invasion and proliferation

according to the single-cell pan-tumor function enrichment study.

These results may provide phenotypic directions for further

experimental verification. On protein level, results from

immunohistochemical analysis also confirmed the higher protein

expression levels of hub genes in LUAD compared with those in

normal tissues. To validate the results on a cellular level, the

mRNA and protein expression of these hub genes were found to be

upregulated in the cancer cell lines Beas-2B and H1299 compared

with those in the control cell line 16-HBE. Immunohistochemistry

results also showed that the hub genes are expressed highly in LUAD

tissues.

The protein encoded by CCNB1 is a

mitosis-associated regulatory protein (37). It functions as a controller of

mitosis entry (38). CCNB1

recombines with Cdk1, which divides the nuclear envelope to allow

the mitotic spindle to enter the chromosome. The role of CCNB1 is

to facilitate entry from the G2 phase to the M phase

(39). CCNB1 overexpression can

lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation by binding Cdk1(40). Previous studies have shown that the

expression level of CCNB1 was increased in a variety of solid

tumors, including breast and colorectal, where the survival rate of

patients with cancer with higher CCNB1 expression was lower

(41). In pituitary adenomas, the

upregulated CCNB1 expression has been reported to serve an

important role in the pathological development of the disease,

suggesting that it can be used as a marker to evaluate tumor

invasiveness (42). In another

study, Chen et al (43)

previously revealed that higher expression levels of CCNB1 promoted

the proliferation, migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells

(43). In terms of the mechanism,

inhibiting the expression of CCNB1 can inhibit the proliferation of

pancreatic cancer cells through the p53 signaling pathway (44).

CCNB2 is a B-type cyclin (45). Qian et al (46) previously found that the higher

expression of CCNB2 is associated with the progression and poor

prognosis of non-small-cell lung cancer (46). In addition, CCNB2 has been reported

to be expressed highly in bladder cancer, where inhibiting CCNB2

expression can inhibit tumor invasion and metastasis (47). CCNB2 was also revealed to affect

the CCNB2/polo-like kinase pathway to promote cell proliferation

and migration in hepatocellular carcinoma (48). In another recent study, Wang et

al (49) found that

microRNA-335-5p may be a negative upstream regulator of CCNB2 to

inhibit the proliferation of LUAD cells.

CCNA2 belongs to a highly conserved cyclin family

(50). CCNA2 has been found to be

expressed highly in pancreatic cancer, where its expression levels

were positively associated with tumor stage and poorer prognosis

(51). In non-small-cell lung

cancer, higher expression levels of CCNA2 have been proposed to be

a biomarker of poor prognosis (52). In addition, higher expression of

CCNA2 in patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer may

indicate a worse prognosis and higher recurrence rates (53). Mechanistically, tanshinone has been

shown to inhibit the progression of LUAD by regulating the

expression of CCNA2(54). Several

bioinformatics studies also previously revealed that CCNA2 is a

potential therapeutic target and prognostic marker of breast and

gastric tumors (55,56).

FOXM1 is a member of the FOX transcription factor

family that serves an important role in cell proliferation,

differentiation and survival (57,58).

Several studies have shown that higher expression levels of FOXM1

are closely associated with poorer prognosis in small cell lung

cancer (58,59). In terms of mechanism, FOXM1 can

regulate cell cycle progression and improve the invasiveness of

bladder cancer (60). Furthermore,

FOXM1 can be indirectly recruited to the homologous region element

of the cell cycle gene through the Myb-MuvB complex, which enables

it to specifically control the expression of CCNB1 and

CCNB2 during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle

(61). A previous study showed

that higher expression of FOXM1 can increase the expression of

CCNB1, where FOXM1 mainly mediates its biological function through

inhibiting the activation of the p53 pathway by recruiting

CBP/P300(62). Chai et al

(63) previously found that the

FOXM1/CCNB1 axis can promote the proliferation of liver cancer

cells, which can be reversed by blocking this axis.

Nomograms have been widely applied for predicting

prognosis and outcome in a clinical setting by combining multiple

risk factors (35). In the present

study, CCNB1, CCNB2 and FOXM1 were found to be

predictors of LUAD. By combining the variables, a nomogram was then

plotted. This nomogram appeared to be effective for in malignancy

prediction with an AUC of 0.92, where it yielded superior findings

in both external validation datasets, with AUCs of 0.91 and 0.96

for GSE10072 and GSE75037, respectively.

In the training set and validation set, all the AUC

values of the present diagnostic model were >0.9. Therefore,

according to this nomogram, the diagnostic evaluation of LUAD based

on the expression levels of CCNB1, CCNB2 and

FOXM1 yielded high accuracy and specificity. These three

genes therefore have potential as biomarkers for the diagnosis of

LUAD.

However, many limitations remain associated with the

present study. Although the present study found that the higher

expression of CCNB1, CCNB2 and CCNA2 is

associated with poorer prognosis in LUAD, high expression of other

cyclin family genes (CCNA2, CCNB1, CCNE1, CCNF and CCNJL) was

associated with superior prognosis in colon cancer (64). Therefore, the prognostic impact of

using the expression of genes in the cyclin family will likely be

dependent on the type of tumors, which remains a topic of further

study. In addition, the specific mechanistic role of these four hub

genes on LUAD remain to be verified by in vitro or in

vivo experiments.

In conclusion, in the present study bioinformatics

analysis identified that FOXM1, CCNB1, CCNB2

and CCNA2 have hub genes that may the important for the

development and prognosis of LUAD. In addition, the expression of

these hub genes was found to be increased in Beas-2B and H1299 cell

lines compared with those in the control cell line 16-HBE.

Therefore, CCNB1, CCNB2 and FOXM1 may have

potential diagnostic and prognostic value for LUAD in the

future.

Supplementary Material

Primer pairs of 4 hub genes.

Multiple comparisons test results of

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR for cyclin A2.

Multiple comparisons test results of

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR for cyclin B1.

Multiple comparisons test results of

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR for cyclin B2.

Multiple comparisons test results of

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR for FOXM1.

Multiple comparisons test results of

western blot analysis for cyclin A2.

Multiple comparisons test results of

western blot analysis for cyclin B1.

Multiple comparisons test results of

western blot analysis for cyclin B2.

Multi-factorial logistic regression of

CCNB2, CCNB1, CCNA2 and FOXM1.

multi-factorial logistic regression of

CCNB2, CCNB1 and FOXM1

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated and/or analyzed during the

current study are available in the GEO database under accession

number (GSE19188, GSE33532, GSE40791, GSE10072 and GSE75037) or at

the following URLs: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE19188;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE33532;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE40791;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE10072;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE75037.

Authors' contributions

XZ and XY confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. XZ provided the funding support of the study and designed

this project. XY wrote the manuscript, and analyzed and interpreted

the data. HG and ZT organized all the figures and interpreted data.

YZ and PL performed tissue culture, RT-qPCR and western blot

experiments, and revised the manuscript, figures and table. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved [approval no.

KYLL-2020(KJ)P-0099] by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second

Hospital of Shandong University (Jinan, China). Written informed

consent was obtained from all participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Torre LA, Siegel RL and Jemal A: Lung

cancer statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 893:1–19. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Boolell V, Alamgeer M, Watkins DN and

Ganju V: The evolution of therapies in non-small cell lung cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 7:1815–1846. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zenke Y, Tsuboi M, Chiba Y, Tsujino K,

Satouchi M, Sawa K, Shimizu J, Daga H, Fujimoto D, Mori M, et al:

Effect of second-generation vs third-generation chemotherapy

regimens with thoracic radiotherapy on unresectable stage III

non-small-cell lung cancer: 10-year follow-up of a WJTOG0105 phase

3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 7:904–909. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Min HY and Lee HY: Mechanisms of

resistance to chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Arch

Pharm Res. 44:146–164. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Lu X, Zhou D, Hou B, Liu QX, Chen Q, Deng

XF, Yu ZB, Dai JG and Zheng H: Dichloroacetate enhances the

antitumor efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents via inhibiting

autophagy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Manag Res.

10:1231–1241. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhang Z, Zhang C, Yang Z, Zhang G, Wu P,

Luo Y, Zeng Q, Wang L, Xue Q, Zhang Y, et al: m6A regulators as

predictive biomarkers for chemotherapy benefit and potential

therapeutic targets for overcoming chemotherapy resistance in

small-cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 14(190)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Pang Z, Chen X, Wang Y, Wang Y, Yan T, Wan

J and Du J: Comprehensive analyses of the heterogeneity and

prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in

non-small-cell lung cancer: Development and validation of an

individualized prognostic model. Int Immunopharmacol.

86(106744)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Riess JW, Gandara DR, Frampton GM, Madison

R, Peled N, Bufill JA, Dy GK, Ou SI, Stephens PJ, McPherson JD, et

al: Diverse EGFR exon 20 insertions and co-occurring molecular

alterations identified by comprehensive genomic profiling of NSCLC.

J Thorac Oncol. 13:1560–1568. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhang F, Wang J, Ma M, Xu Y, Lu X and Wei

S: Genomic alteration profiles of lung cancer and their

relationship to clinical features and prognosis value using

individualized genetic testing. J Thorac Dis. 13:5007–5015.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Jirawatnotai S, Dalton S and

Wattanapanitch M: Role of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases in

pluripotent stem cells and their potential as a therapeutic target.

Semin Cell Dev Biol. 107:63–71. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gong K, Zhou H, Liu H, Xie T, Luo Y, Guo

H, Chen J, Tan Z, Yang Y and Xie L: Identification and integrate

analysis of key biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis of non-small

cell lung cancer based on bioinformatics analysis. Technol Cancer

Res Treat. 20(15330338211060202)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Thoma OM, Neurath MF and Waldner MJ:

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and their therapeutic potential

in colorectal cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol.

12(757120)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Susanti NMP and Tjahjono DH:

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors in cell cycle

dysregulation for breast cancer treatment. Molecules.

26(4462)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hou J, Aerts J, den Hamer B, van Ijcken W,

den Bakker M, Riegman P, van der Leest C, van der Spek P, Foekens

JA, Hoogsteden HC, et al: Gene expression-based classification of

non-small cell lung carcinomas and survival prediction. PLoS One.

5(e10312)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Quek K, Li J, Estecio M, Zhang J, Fujimoto

J, Roarty E, Little L, Chow CW, Song X, Behrens C, et al: DNA

methylation intratumor heterogeneity in localized lung

adenocarcinomas. Oncotarget. 8:21994–22002. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhang Y, Foreman O, Wigle DA, Kosari F,

Vasmatzis G, Salisbury JL, van Deursen J and Galardy PJ: USP44

regulates centrosome positioning to prevent aneuploidy and suppress

tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 122:4362–4374. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM and Irizarry

RA: Affy-analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level.

Bioinformatics. 20:307–315. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43(e47)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kolde R, Laur S, Adler P and Vilo J:

Robust rank aggregation for gene list integration and

meta-analysis. Bioinformatics. 28:573–580. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yan S, Wang W, Gao G, Cheng M, Wang X,

Wang Z, Ma X, Chai C and Xu D: Key genes and functional

coexpression modules involved in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus

erythematosus. J Cell Physiol. 233:8815–8825. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Sherman BT, Hao M, Qiu J, Jiao X, Baseler

MW, Lane HC, Imamichi T and Chang W: DAVID: A web server for

functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene

lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (W1):W216–W221.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

22

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, Kuhn M,

Wyder S, Simonovic M, Santos A, Doncheva NT, Roth A, Bork P, et al:

The STRING database in 2017: Quality-controlled protein-protein

association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res.

45 (D1):D362–D368. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS,

Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T: Cytoscape: A

software environment for integrated models of biomolecular

interaction networks. Genome Res. 13:2498–2504. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Bader GD and Hogue CW: An automated method

for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction

networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 4(2)2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Assenov Y, Ramírez F, Schelhorn SE,

Lengauer T and Albrecht M: Computing topological parameters of

biological networks. Bioinformatics. 24:282–284. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C and

Zhang Z: GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression

profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45

(W1):W98–W102. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Rouillard AD, Gundersen GW, Fernandez NF,

Wang Z, Monteiro CD, McDermott MG and Ma'ayan A: The harmonizome: A

collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine

knowledge about genes and proteins. Database (Oxford).

2016(baw100)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya

SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi BVSK and

Varambally S: UALCAN: A Portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene

expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 19:649–658.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Landi MT, Dracheva T, Rotunno M, Figueroa

JD, Liu H, Dasgupta A, Mann FE, Fukuoka J, Hames M, Bergen AW, et

al: Gene expression signature of cigarette smoking and its role in

lung adenocarcinoma development and survival. PLoS One.

3(e1651)2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Girard L, Rodriguez-Canales J, Behrens C,

Thompson DM, Botros IW, Tang H, Xie Y, Rekhtman N, Travis WD,

Wistuba II, et al: An expression signature as an aid to the

histologic classification of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 22:4880–4889. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Venables WN and Ripley BD: Modern applied

statistics with S. 4th edition. Statistics and Computing, 2002.

|

|

34

|

Dobson AJ: An introduction to generalized

linear models, second edition. Chapman & Hall/crc, 2001.

|

|

35

|

Harrell FE Jr: Regression modeling

strategies: With applications to linear models, logistic

regression, and survival analysis. Springer, 2010.

|

|

36

|

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N,

Lisacek F, Sanchez JC and Müller M: pROC: An open-source package

for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics.

12(77)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Eichhorn JM, Kothari A and Chambers TC:

Cyclin B1 overexpression induces cell death independent of mitotic

arrest. PLoS One. 9(e113283)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Gavet O and Pines J: Progressive

activation of CyclinB1-Cdk1 coordinates entry to mitosis. Dev Cell.

18:533–543. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chang CC, Hung CM, Yang YR, Lee MJ and Hsu

YC: Sulforaphane induced cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase via

the blockade of cyclin B1/CDC2 in human ovarian cancer cells. J

Ovarian Res. 6(41)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Chu R, Terrano DC and Chambers TC:

Cdk1/cyclin B plays a key role in mitotic arrest-induced apoptosis

by phosphorylation of Mcl-1, promoting its degradation and freeing

Bak from sequestration. Biochem Pharmacol. 83:199–206.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Ye C, Wang J, Wu P, Li X and Chai Y:

Prognostic role of cyclin B1 in solid tumors: A meta-analysis.

Oncotarget. 8:2224–2232. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Zhao P, Zhang P, Hu W, Wang H, Yu G, Wang

Z, Li C, Bai J and Zhang Y: Upregulation of cyclin B1 plays

potential roles in the invasiveness of pituitary adenomas. J Clin

Neurosci. 43:267–273. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chen EB, Qin X, Peng K, Li Q, Tang C, Wei

YC, Yu S, Gan L and Liu TS: HnRNPR-CCNB1/CENPF axis contributes to

gastric cancer proliferation and metastasis. Aging (Albany NY).

11:7473–4791. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Zhang H, Zhang X, Li X, Meng WB, Bai ZT,

Rui SZ, Wang ZF, Zhou WC and Jin XD: Effect of CCNB1 silencing on

cell cycle, senescence, and apoptosis through the p53 signaling

pathway in pancreatic cancer. J Cell Physiol. 234:619–631.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Sarafan-Vasseur N, Lamy A, Bourguignon J,

Le Pessot F, Hieter P, Sesboüé R, Bastard C, Frébourg T and Flaman

JM: Overexpression of B-type cyclins alters chromosomal

segregation. Oncogene. 21:2051–2057. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Qian X, Song X, He Y, Yang Z, Sun T, Wang

J, Zhu G, Xing W and You C: CCNB2 overexpression is a poor

prognostic biomarker in Chinese NSCLC patients. Biomed

Pharmacother. 74:222–227. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Lei CY, Wang W, Zhu YT, Fang WY and Tan

WL: The decrease of cyclin B2 expression inhibits invasion and

metastasis of bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 34:237.e1–e10.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Li R, Jiang X, Zhang Y, Wang S, Chen X, Yu

X, Ma J and Huang X: Cyclin B2 overexpression in human

hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis. Arch

Med Res. 50:10–17. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wang X, Xiao H, Wu D, Zhang D and Zhang Z:

miR-335-5p regulates cell cycle and metastasis in lung

adenocarcinoma by targeting CCNB2. Onco Targets Ther. 13:6255–6263.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Lees EM and Harlow E: Sequences within the

conserved cyclin box of human cyclin A are sufficient for binding

to and activation of cdc2 kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 13:1194–1201.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Jiang P, Zhang M, Gui L and Zhang K:

Expression patterns and prognostic values of the cyclin-dependent

kinase 1 and cyclin A2 gene cluster in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J

Int Med Res. 48(300060520930113)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Brcic L, Heidinger M, Sever AZ, Zacharias

M, Jakopovic M, Fediuk M, Maier A, Quehenberger F, Seiwerth S and

Popper H: Prognostic value of cyclin A2 and B1 expression in lung

carcinoids. Pathology. 51:481–486. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Ko E, Kim Y, Cho EY, Han J, Shim YM, Park

J and Kim DH: Synergistic effect of Bcl-2 and cyclin A2 on adverse

recurrence-free survival in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann

Surg Oncol. 20:1005–1012. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Li Z, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Wang F, Yin C, Ding

L and Zhang S: Tanshinone IIA suppresses the progression of lung

adenocarcinoma through regulating CCNA2-CDK2 complex and AURKA/PLK1

pathway. Sci Rep. 11(23681)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wang Y, Zhong Q, Li Z, Lin Z, Chen H and

Wang P: Integrated profiling identifies CCNA2 as a potential

biomarker of immunotherapy in breast cancer. Onco Targets Ther.

14:2433–2448. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lee Y, Lee CE, Oh S, Kim H, Lee J, Kim SB

and Kim HS: Pharmacogenomic analysis reveals CCNA2 as a predictive

biomarker of sensitivity to polo-like kinase I inhibitor in gastric

cancer. Cancers (Basel). 12(1418)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Priller M, Pöschl J, Abrão L, von Bueren

AO, Cho YJ, Rutkowski S, Kretzschmar HA and Schüller U: Expression

of FoxM1 is required for the proliferation of medulloblastoma cells

and indicates worse survival of patients. Clin Cancer Res.

17:6791–6801. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Liu B, Su F, Lin R, Teng H and Ju Y:

Overexpression of forkhead box M1 is associated poor survival in

patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 14

(Suppl):S1121–S1123. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Liang SK, Hsu CC, Song HL, Huang YC, Kuo

CW, Yao X, Li CC, Yang HC, Hung YL, Chao SY, et al: FOXM1 is

required for small cell lung cancer tumorigenesis and associated

with poor clinical prognosis. Oncogene. 40:4847–4858.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Yi L, Wang H, Li W, Ye K, Xiong W, Yu H

and Jin X: The FOXM1/RNF26/p57 axis regulates the cell cycle to

promote the aggressiveness of bladder cancer. Cell Death Dis.

12(944)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Chen X, Müller GA, Quaas M, Fischer M, Han

N, Stutchbury B, Sharrocks AD and Engeland K: The forkhead

transcription factor FOXM1 controls cell cycle-dependent gene

expression through an atypical chromatin binding mechanism. Mol

Cell Biol. 33:227–236. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Li S, Liu N, Piao J, Meng F and Li Y:

CCNB1 expedites the progression of cervical squamous cell carcinoma

via the regulation by FOXM1. Onco Targets Ther. 13:12383–12395.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Chai N, Xie HH, Yin JP, Sa KD, Guo Y, Wang

M, Liu J, Zhang XF, Zhang X, Yin H, et al: FOXM1 promotes

proliferation in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by

transcriptional activation of CCNB1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

500:924–929. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Li J, Zhou L, Liu Y, Yang L, Jiang D, Li

K, Xie S, Wang X and Wang S: Comprehensive analysis of cyclin

family gene expression in colon cancer. Front Oncol.

11(674394)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|