Introduction

A period of >5 years has passed since the

emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), yet the world

continues to grapple with its impact (1). Successive waves of infection led to

case fatality rates as high as 15% in certain populations, with

mortality estimates suggesting that the true toll may be

significantly worse than this (2,3). The

cause of this lethal disease is severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and its worldwide effect was classified

as a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March

2020(4). Viral transmission is via

human-to-human bodily fluid contact (droplet and/or aerosol), and

the incubation period can be as long as 14-28 days before symptoms

develop (5). Quarantine has proven

effective in protecting susceptible people and reducing

transmission rate.

The initial symptoms of most COVID-19 infections are

often non-specific, such as coughing and dyspnea, while ~20% of

patients present with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms within the

first 2 days of infection (6).

Current interventions focus on supportive therapies, and novel

vaccines have proven effective at mitigating disease severity

(7,8).

The synergistic association between infection and

malnutrition has been established (9). As COVID-19 progresses, ~5% of

patients who become critically ill require an intensive care unit

(ICU) admission, and regulating nutritional balance in these

patients is vitally important for supportive care (10). Clinical reports have shown that the

severity of COVID-19 infection is compounded by nutritional

variables, especially for patients with GI symptoms (4). In this context, related studies have

also demonstrated that nutritional support is a promising treatment

for patients with COVID-19 and high nutritional risks (11-14).

To facilitate generalization of nutritional

interventions, the president of the American Society for Parenteral

and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) proposed a focused review of current

clinical nutrition practices, including nutrition assessment,

processing steps, monitoring and reassessment (15). The main points included: i) Early

EN initiation, within 24-36 h of ICU admission or 12 h of

intubation; ii) monitoring and reassessing patients during the

EN/PN regimens; and iii) early EN may not be preferential in a

subset of patients with GI symptoms; PN needing to be used early

instead. Several malnutrition screening tools, such as Nutrition

Risk Screen-2002 (NRS-2002), Global Leadership Initiative on

Malnutrition (GLIM) (13,16,17),

have gained widespread acceptance in recent years, largely due to

their clinical practicality. These tools typically incorporate

common clinical variables such as weight loss, body mass index

(BMI), fat-free mass indices (FFMI) and signs of eating

difficulties (such as appetite loss or reduced intake). The present

study included BMI and FFMI for nutritional evaluation since their

acquisitions were easy to access.

Recent studies on nutritional timing in ICU patients

with COVID-19 found mixed outcomes regarding early versus delayed

support. Some have reported that early enteral nutrition (EN)

(within 24-48 h) can lead to reduced mortality and ICU stay, while

others report equivocal findings with no clear advantage from early

or delayed support, and they do not raise any concerns about

tolerance during the acute phase (15-21).

Following ICU admission, EN could be started early

as an effective way to improve nutritional status through

nasogastric tube, even while patients are in a prone position

(12). However, after EN

initiation, refeeding syndrome (RS) can occur in patients who have

been undernourished for a substantial period of time, owing to the

wide range of metabolic and electrolyte imbalances, impaired

glucose tolerance and vitamin deficiency in these patients

(22,23). In severe cases, it can even lead to

organ failure and death. The current definition of RS is a decrease

in either serum potassium, phosphorus or magnesium level within 5

days of the reintroduction of calories (22). Based on the degree of reduction in

the levels of these nutrients, RS is classified as mild (10-20%),

moderate (20-30%) or severe (>30% or organ dysfunction resulting

from a decrease of any of the aforementioned electrolyte ions or

thiamine-deficiency) (22). It is

reasonable to speculate that a delay in nutritional support could

exacerbate RS since the period of nutrient restriction would be

prolonged. However, for most COVID-19 patients at high risk of

malnutrition, nutritional support is initiated as early as

possible. Once the starvation period is excluded as a contributing

factor, the method of nutritional intervention remains the key

determinant influencing RS incidence. As the preferred nutritional

therapy for patients with COVID-19, EN requires careful timing,

composition and monitoring of total daily intakes. However, it

remains unclear whether the timing of EN initiation influences RS

incidence or severity in critically ill patients with COVID-19. To

address this, a retrospective study was conducted on patients with

COVID-19 who were admitted to the ICU, comparing different EN

initiation times to assess their impact on RS incidence.

Patients and methods

Study population

The present study included critically ill patients

with established COVID-19 infection, confirmed by the standard

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction method, who were

admitted to Tongji Hospital (Wuhan, China) between January 1 and

December 31, 2020. Severe cases met at least one of the following

criteria: i) Shortness of breath (respiratory rate ≥30

breaths/min); ii) oxygen saturation ≤93% in resting state; iii)

partial pressure of arterial oxygen/inspired oxygen concentration

≤300 mmHg; and iv) obvious progress of lesion size by >50%

within 24-48 h, as determined by pulmonary imaging (24,25).

Study procedures

Nutritional support was given to severely ill

patients at high nutritional risk, as defined by ASPEN criteria

within 24-36 h of ICU admission (15). EN was the first line of nutrient

support for most patients, while parenteral nutrition (PN) was

administered if EN was contraindicated or insufficient. EN was

supplied with complete nutritional formula, such as whole protein

preparations or short peptide/amino acid-based preparations. PN was

provided with nutrient mixtures, including carbohydrates, fats,

proteins, vitamins and minerals. A previous study (26) showed that RS prevalence is

significantly associated withNRS-2002 scores. According to NRS-2002

scoring (27), a total of 304

cases in Tongji Hospital scored ≥3 points, representing those with

a high nutritional risk.

Nutritional support was administered as quickly as

possible following admission to the hospital. Energy requirement

was determined based on energy expenditure calculations from

indirect calorimetry measurements for each patient. Target

nutritional requirement ranges were 25-30 kcal/(kg/day) total

calories, 1.5-2.0 g/(kg/day) total protein and 7.8-11.1 mmol/l

blood glucose. After admission, EN was the preferred route of

administration. However, for patients with digestive symptoms or

elevated risk of aspiration, PN was administered within 24-48 h and

gradually shifted to EN thereafter. Once the nutritional ranges

were achieved using EN, PN was discontinued. In severe cases, EN

was administered through a nasogastric tube. Patients in a prone

position could also receive EN under the rationale of prophylaxis

for aspiration. The mean initial rate of EN therapy was 20 ml/h,

and gradually increased to 70-100 ml/h. The dosage of EN therapy

increased from 500 ml/day to 1,000 ml/day. During EN

administration, each patient's tolerance was evaluated by checking

the gastric residual volume every 4 h. If the residual volume was

>500 ml, or accompanied with severe nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

or other symptoms, EN infusion would be slowed, paused or changed

to another EN reagent. For all COVID-19 patients with malnutrition

risk, EN support was preferred for those without contraindications.

PN was only applied for those who were EN intolerant or

insufficient response from EN. To minimize the risk of RS

associated with PN, electrolyte levels were continuously monitored

throughout PN administration to ensure they remained within

relatively normal ranges prior to initiating EN.

During the nutritional support period, serum

electrolytes were measured daily. If any electrolyte levels dropped

below the following thresholds, sodium <130 mmol/l, potassium

<3.5 mmol/l, phosphorus<0.96 mmol/l and magnesium <0.70

mmol/l, then the corresponding electrolytes would be replenished as

needed and carefully monitored to ensure they remained within the

normal range. Throughout the entire course of nutritional support,

levels of thiamine and other essential vitamins (such as vitamins D

and E) were continuously monitored and promptly supplemented when

found to be deficient. RS in the present study was identified

according to the ASPEN definition as any one, two or three

electrolyte imbalances, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia and/or

hypomagnesemia, after starting EN. A time cut-off time of 3 days

after nutritional support was selected, which was within 5 days of

reintroduction of calories.

Data collection

All patients who received EN therapy in this study

were classified into two groups based on EN initiation intervals.

The early EN (EEN) group were those with an interval from admission

to first EN therapy of ≤2 days and the late EN (LEN) group were

those with an interval from admission to first EN therapy of ≥3

days.

To ensure adequate sample size in the power

estimates, an odds ratio (OR) of 2 was assumed for the association

between LEN and RS, with a significance level (α) of 0.05

(two-sided) and a statistical power (1-β) of 0.8. Based on these

parameters (OR, α, 1-β), the calculated minimum required sample

size was 280 participants (case group, n=140; control group,

n=140). A total of 211 cases were included in the final analysis,

owing to limitations in patient volume and implementing

inclusion/exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Severe COVID-19, ii) NRS-2002 scores ≥3 points, iii)

receiving EN support, iv) age ≥18 years and v) no immunodeficiency

or malignant diseases. Exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Mild

or moderate COVID-19, ii) NRS-2002 scores <3 points, iii) not

needing nutritional support, or only PN support, iv) age <18

years and v) presence of immunodeficiency or malignant

diseases.

The requirement for informed consent was waived from

Tongji Hospital as this was a retrospective analysis. Data on

patient demographics, symptoms, underlying diseases and laboratory

examinations were collected from electronic medical records. Some

interventions that could potentially affect nutritional status and

RS incidence [for example, mechanical ventilation and renal

replacement therapy (RRT)], were also compared between the two

groups. Inflammatory and biochemical markers, including serum

albumin, globulin, pH and creatinine, were measured upon admission.

Additionally, serum phosphorus, potassium and magnesium levels were

assessed on admission and 3 days after EN initiation as

aforementioned.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome of the present study was the

incidence and degree of RS 3 days after EN initiation. Patients

were defined as RS-positive if they experienced a decrease below

the aforementioned thresholds in serum phosphorus, potassium or

magnesium level 3 days after EN initiation. Secondary outcomes were

3-month overall survival rate, in-hospital length of stay, ICU

length of stay, incidence of airway complications and GI

intolerance. Airway complications were defined as any episode of

vomiting, followed by desaturation and formation of a mucus plug.

Subjects who required frequent sputum suction (>2 times/h) and

had episodes of temporary desaturation caused by airway obstruction

due to sputum were defined as having a mucus plug (21). GI intolerance was defined as the

appearance of serious diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal

discomfort or GI bleeding after EN, which required therapeutic

intervention (28).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation and were confirmed by Student's t-test or

Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as

percentages and analyzed by the χ2 test or Fisher's

exact test. The 6-month survival curve was plotted using the

Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test for analysis. Receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted, and the area

under the curve (AUC) was calculated to analyze the potential

predictors for RS. Independent risk factors for RS were determined

using logistic regression. Variables with a P-value <0.2 in the

univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. To further decrease the type I error, Bonferroni's

correction adjustment was applied if necessary. All statistical

analyses and plotting were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp.)

and GraphPad Prism 6.0 (Dotmatics).

Results

Baseline patient demographics and

clinical variables

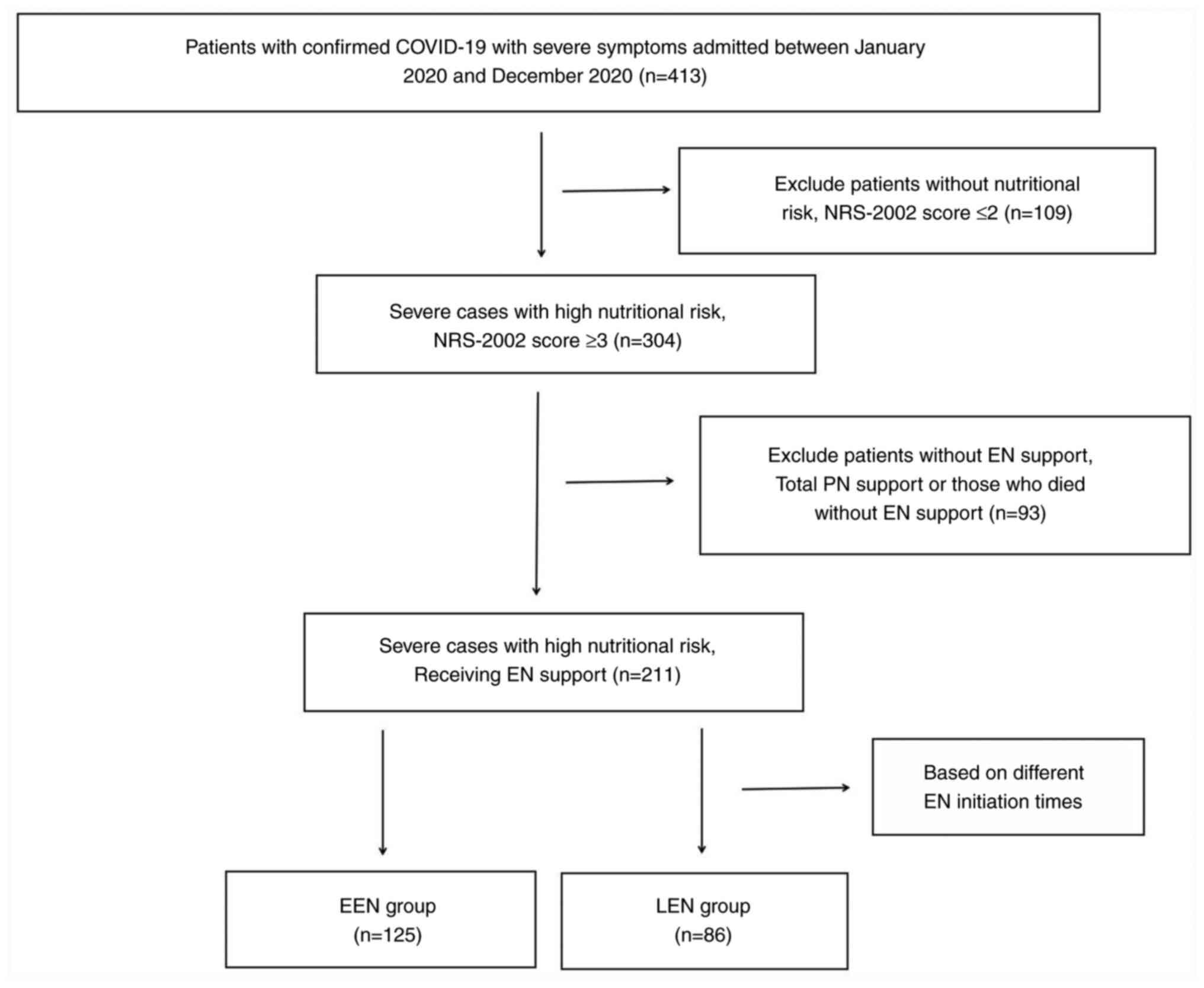

A total of 413 consecutive hospitalized patients

with severe symptoms of COVID-19 infection were evaluated at Tongji

Hospital (Wuhan, China) between January 2020 and December 2020.

Among them, 211 patients with high nutritional risk received EN

support. Of these, 122 patients required electrolyte

supplementation during the first 3 days of EN. Table I shows the key demographic and

clinical characteristics of participants based on EN initiation

intervals, with 125 patients (59.24%) assigned to the EEN group and

86 patients (40.76%) assigned to the LEN group. Patient selection

and group assignment criteria are shown in Fig. 1.

| Table IDemographic characteristics of

patients with coronavirus disease 2019 according to EN

initiation. |

Table I

Demographic characteristics of

patients with coronavirus disease 2019 according to EN

initiation.

| Variables | All (n=211) | EEN (n=125) | LEN (n=86) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 64±1.4 | 64±1.5 | 64±1.3 | 0.6974 |

| Male sex, n

(%) | 101 (47.87) | 51 (40.80) | 50 (58.14) | 0.1473 |

| Weight, kg | 60±1.6 | 59±1.6 | 60±1.5 | 0.5847 |

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | 22±0.4 | 22±0.4 | 22±0.3 | 0.5698 |

| Fat-free mass

indices, kg/m2 | 17±0.5 | 17±0.4 | 16±0.7 | 0.5022 |

| APACHE II

scorea | 22±0.5 | 22±0.6 | 23±0.5 | 0.7872 |

| Symptoms, n

(%) | | | | |

|

Fever | 184 (87.20) | 104 (83.20) | 80 (93.02) | 0.4383 |

|

Cough | 174 (82.46) | 99 (79.20) | 75 (87.21) | 0.0788 |

|

Respiratory

distress | 103 (48.82) | 65 (52.00) | 38 (44.19) | 0.7431 |

| Underlying

diseases, n (%) | | | | |

|

Hypertension | 124 (58.77) | 73 (58.40) | 51 (59.30) | 0.9803 |

|

Diabetes

mellitus | 78 (36.97) | 42 (33.60) | 36 (41.86) | 0.4555 |

|

Chronic

cardiovascular disease | 47 (22.27) | 28 (22.40) | 19 (22.09) | 0.5838 |

|

Chronic

respiratory disease | 42 (19.91) | 24 (19.20) | 18 (20.93) | 0.4125 |

| Past history, n

(%) | | | | |

|

Smoking | 56 (26.54) | 34 (27.20) | 22 (25.58) | 0.4449 |

|

Drinking | 24 (11.37) | 16 (12.80) | 8 (9.30) | 0.4535 |

| Mechanical

ventilation, n (%) | 110 (52.13) | 70 (56.00) | 40 (46.51) | 0.4380 |

| Renal replacement

therapy, n (%) | 24 (11.37) | 16 (12.80) | 8 (9.30) | 0.1075 |

| Caloric intake,

Kcal/day | 1778±11.4 | 1773±14.3 | 1785±10.5 | 0.5063 |

| Protein intake,

g/day | 115±1.2 | 115±1.1 | 114±1.1 | 0.7304 |

| Electrolyte

supplementation from days 1 to day 3, n (%) | 132 (62.56) | 77 (61.60) | 55 (63.95) | 0.3020 |

| NRS-2002 score | 4±0.1 | 4±0.2 | 4±0.1 | 0.3897 |

| Time interval to

EN, days | 3±0.1 | 2±0.1 | 5±0.1 | 0.0413b |

The mean age of all patients was 64 years, ranging

from 46 to 92 years, and 101 patients (47.87%) were male. General

symptoms of COVID-19 included fever, cough and respiratory

distress. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (58.77% of

the entire cohort). Both mechanical ventilation and RRT, which may

be confounders for nutrition consumption, were similar between the

groups (P=0.4380 and P=0.1075, respectively). Daily mean calories

and protein intake were also not significantly different between

groups (P=0.5063 and P=0.7304, respectively), which excluded some

confounding factors for RS incidence. The nutritional state,

including weight, BMI, FFMI and NRS-2002 scores on admission, was

comparable between the two groups (all P≥0.05). The only

significant difference between the two groups was the mean time

interval to EN therapy initiation, which at 2 days in the EEN

group, was significantly lower than the interval of 5 days in the

LEN group (P=0.0413).

Serum electrolytes and blood

variables

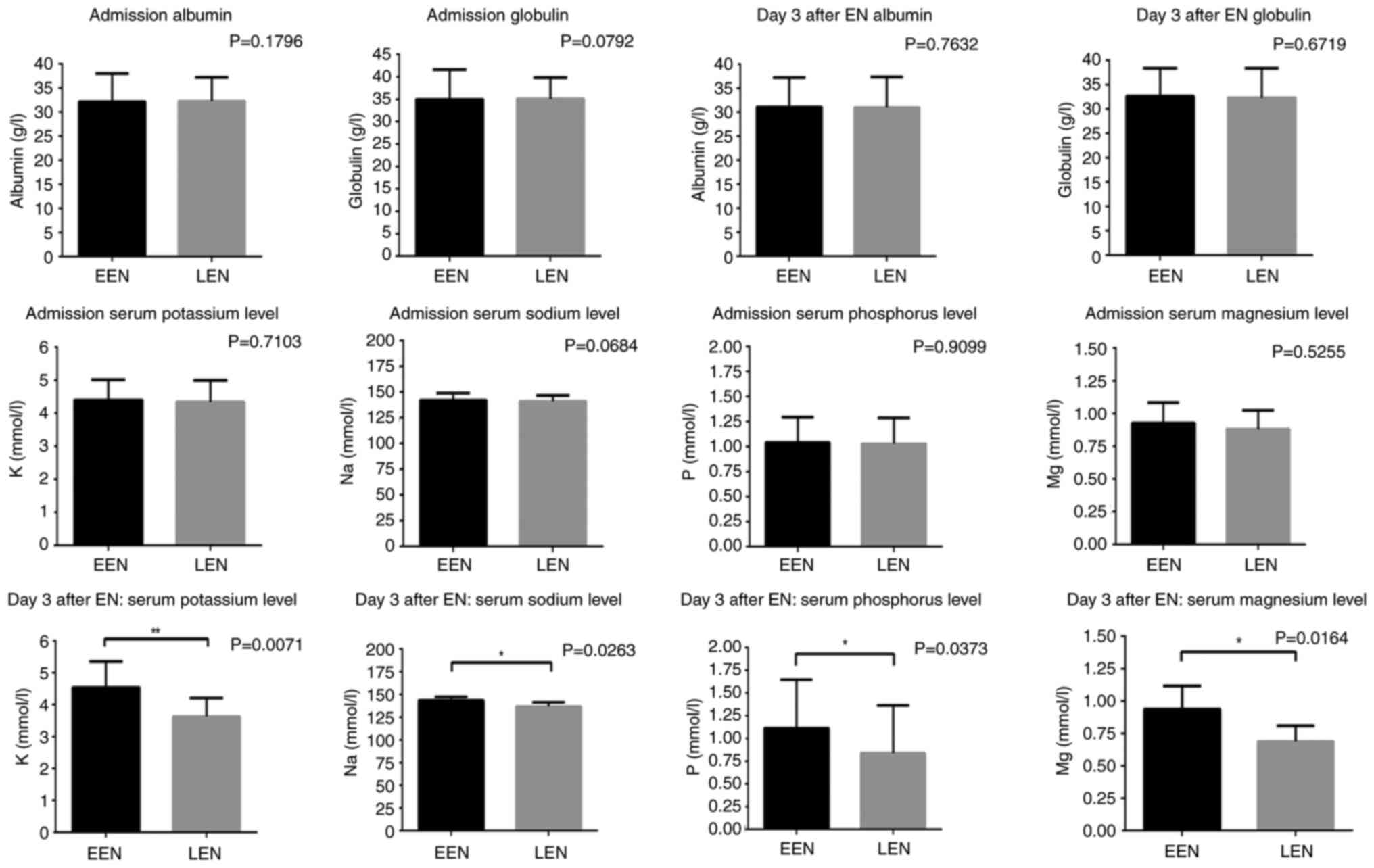

Baseline laboratory results for all patients were

collected on admission and again 3 days after EN initiation

(Table II; Fig. 2). At time of admission, blood cell

counts for leukocytes, neutrophils and lymphocytes were similar

between the two groups (all P>0.05). Likewise, serum levels of

albumin, globulin, pH and creatinine were also not significantly

different between groups (all P>0.05). Both groups displayed

similar electrolyte balance, all within the acceptable range (all

P>0.05). At 3 days post-EN initiation, there was a significant

reduction in potassium, sodium, phosphorus and magnesium levels in

the LEN group compared with those in the EEN group (P=0.0071,

P=0.0263, P=0.0373 and P=0.0164, respectively), with all of these

electrolytes falling below the clinically acceptable range. In

order to decrease the type I error incidence, Bonferroni's

correction was applied. After adjustment, only the changes in serum

potassium (P=0.0213) and magnesium (P=0.0492) levels at 3 days

post-EN initiation remained statistically significant (Table II; Fig. S1).

| Table IILaboratory examination of patients

with coronavirus disease 2019 according to EN initiation. |

Table II

Laboratory examination of patients

with coronavirus disease 2019 according to EN initiation.

| A, Admission |

|---|

| Variables | All (n=211) | EEN (n=125) | LEN (n=86) | P-value | P-value

(Bonferroni's correction) |

|---|

| Leukocytes

(x109/l) | 8.874±0.7250 | 8.901±0.7324 | 8.846±0.6977 | 0.5470 | / |

| Neutrophils

(x109/l) | 7.512±0.7158 | 7.520±0.7443 | 7.507±0.6869 | 0.6984 | / |

| Lymphocytes

(x109/l) | 0.855±0.0715 | 0.822±0.0794 | 0.881±0.0637 | 0.4631 | / |

| Albumin, g/l | 32.19±0.6886 | 32.13±0.7904 | 32.24±0.5867 | 0.1796 | / |

| Globulin, g/l | 35.03±0.7327 | 34.98±0.8993 | 35.07±0.5642 | 0.0792 | / |

| pH | 7.401±0.0039 | 7.401±0.0043 | 7.402±0.0034 | 0.7953 | / |

| Creatinine,

µmol/l | 130.5±5.2535 | 135.8±5.8310 | 124.4±4.6760 | 0.1253 | / |

| Potassium,

mmol/l | 4.372±0.0803 | 4.403±0.0834 | 4.349±0.0771 | 0.7103 | / |

| Sodium, mmol/l | 141.5±0.7088 | 142.0±0.9232 | 141.1±0.6445 | 0.0684 | / |

| Phosphorus,

mmol/l | 1.032±0.0448 | 1.039±0.0482 | 1.027±0.0394 | 0.9099 | / |

| Magnesium,

mmol/l | 0.899±0.0273 | 0.928±0.0299 | 0.882±0.0216 | 0.5255 | / |

| B, 3 days after EN

initiation |

| Variables | All (n=211) | EEN (n=125) | LEN (n=86) | P-value | P-value

(Bonferroni's correction) |

| Potassium,

mmol/l | 4.029±0.0889 | 4.540±0.1093 | 3.432±0.0683 | 0.0071a | 0.0213a |

| Sodium, mmol/l | 139.8±0.5276 | 143.6±0.5226 | 134.8±0.5287 | 0.0263a | 0.0789 |

| Phosphorus,

mmol/l | 0.944±0.0913 | 1.114±0.1023 | 0.838±0.0802 | 0.0373a | 0.1119 |

| Magnesium,

mmol/l | 0.789±0.0257 | 0.938 ± 0.0337 | 0.691 ± 0.0181 | 0.0164a | 0.0492a |

Primary and secondary outcomes

RS incidence was significantly lower in the EEN

group compared with that in the LEN group (27.20% vs. 60.47%,

P=0.0440), with RS severity higher in the LEN group, since 63.46%

of patients had ‘moderate’ RS compared with 41.18% in the EEN group

(P=0.0236) (Table III). There

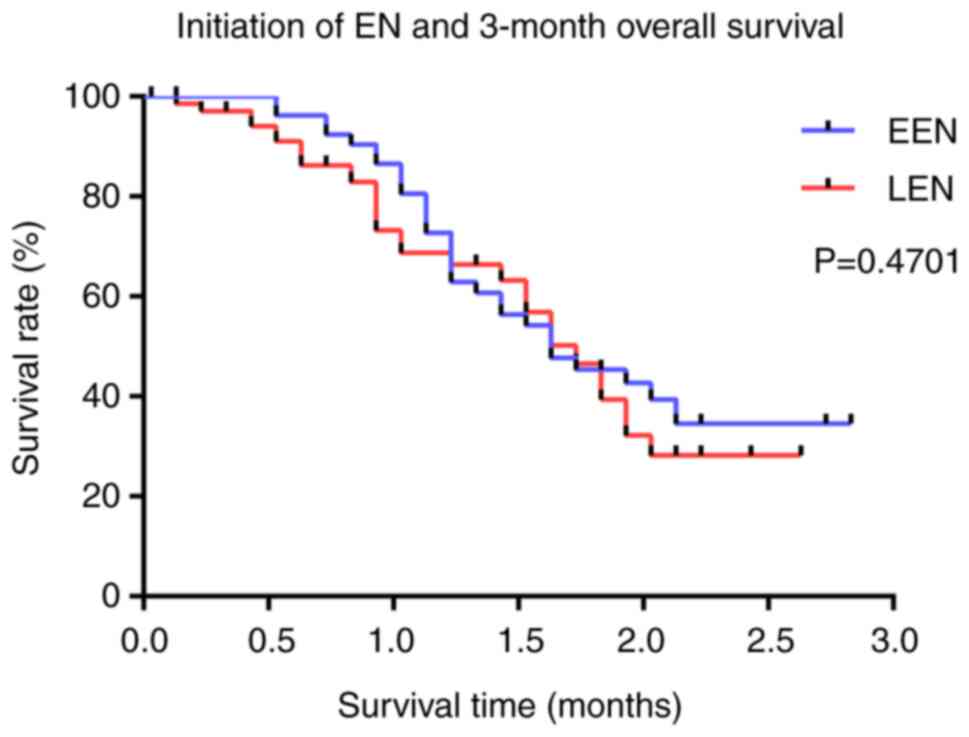

were no significant differences in overall survival between the two

groups at 3 months (P=0.4701) (Fig.

3). Notably, despite the similar mortality rates, in-hospital

and ICU stay lengths were significantly lower in the EEN group

(19.46±0.81 vs. 29.22±1.10, P<0.0001; and 17.16±1.04 vs.

22.39±1.50, P=0.0099, respectively). Moreover, the EEN group did

not experience any significant increase in risk of airway

complications or GI intolerance (P=0.0742 and P=0.3392,

respectively) (Table III).

| Table IIIOutcomes of subjects with coronavirus

disease 2019 in the groups receiving early versus late EN. |

Table III

Outcomes of subjects with coronavirus

disease 2019 in the groups receiving early versus late EN.

| Outcomes | All (n=211) | EEN (n=125) | LEN (n=86) | P-value |

|---|

| Refeeding syndrome,

n (%) | 86 (40.76) | 34 (27.20) | 52 (60.47) | 0.0440a |

|

Mild | 39 (45.35) | 20 (58.82) | 19 (36.54) | 0.0236a |

|

Moderate | 47 (54.65) | 14 (41.18) | 33 (63.46) | |

| 3-Month mortality,

n (%) | 106 (50.24) | 69 (55.20) | 37 (43.02) | 0.4701 |

| In-hospital stay

length, days | 24.95±0.964 | 19.46±0.813 | 29.22±1.095 |

<0.0001a |

| ICU stay length,

days | 20.23±1.277 | 17.16±1.037 | 22.39±1.495 | 0.0099a |

| Airway

complications, n (%) | 82 (38.86) | 54 (43.20) | 28 (32.56) | 0.0742 |

| GI intolerance, n

(%) | 80 (37.91) | 44 (35.20) | 36 (41.86) | 0.3392 |

Prediction of RS incidence

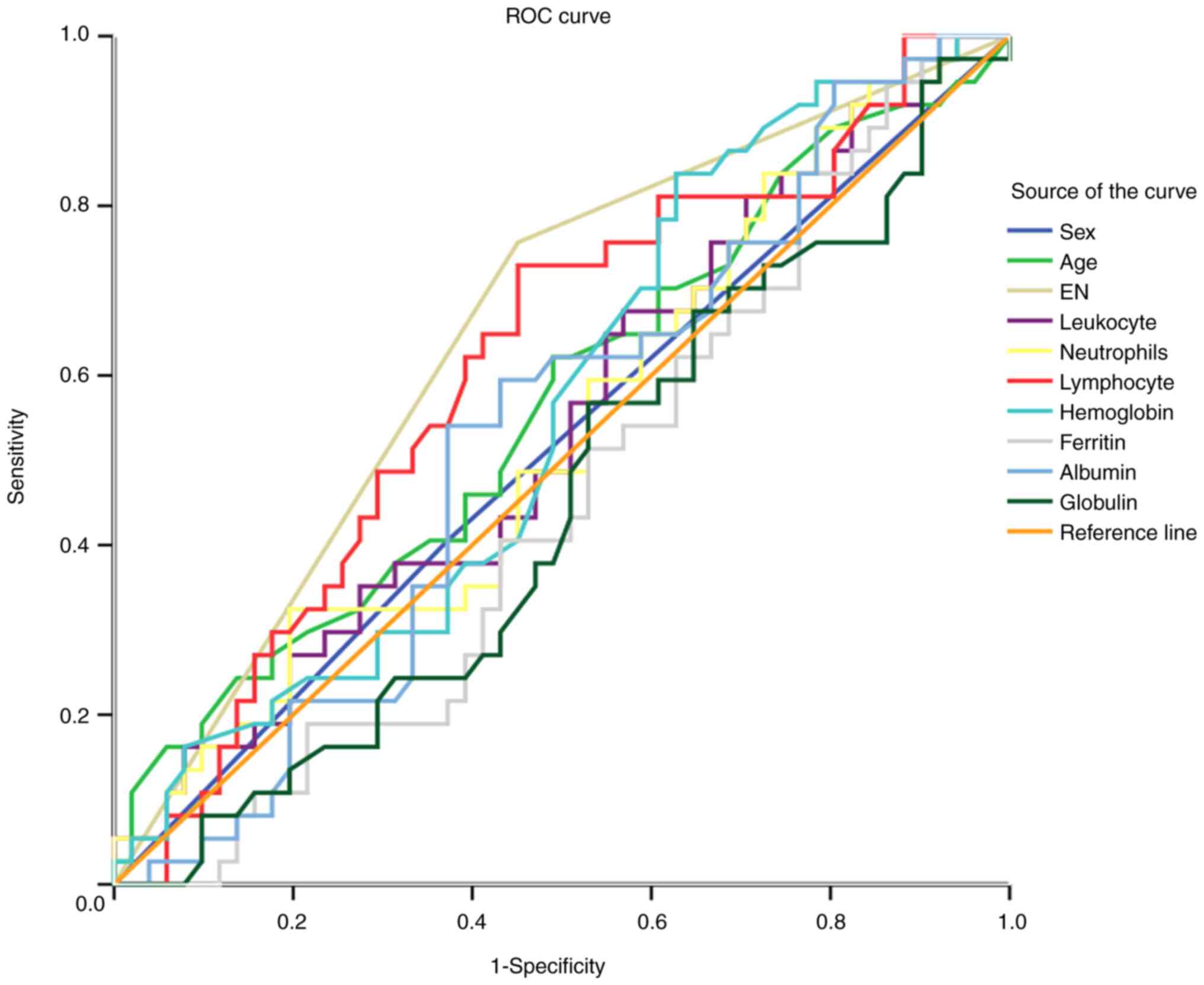

ROC curves and their associated AUCs for both the

EEN and LEN groups are shown in Fig.

4 and Table IV, respectively.

AUC values for most parameters, including age, sex, and serum

electrolytes at admission, were within the range of 0.447-0.573

(all P>0.05), which could not effectively predict RS incidence.

However, the EN initiation AUC was 0.667 (P=0.022), indicating a

reasonable predictive value for this variable.

| Table IVROC curve of risk model for refeeding

syndrome with coronavirus disease 2019. |

Table IV

ROC curve of risk model for refeeding

syndrome with coronavirus disease 2019.

| | Asymptotic 95%

confidence interval |

|---|

| Variables | AUROC | Standard error | P-value | Lower bound | Upper bound |

|---|

| Age | 0.573 | 0.072 | 0.316 | 0.431 | 0.715 |

| Sex | 0.530 | 0.075 | 0.676 | 0.383 | 0.677 |

| EN | 0.667 | 0.072 | 0.022a | 0.526 | 0.808 |

| Admission | | | | | |

|

Potassium | 0.486 | 0.072 | 0.844 | 0.345 | 0.627 |

|

Sodium | 0.447 | 0.071 | 0.470 | 0.308 | 0.587 |

|

Phosphorus | 0.472 | 0.074 | 0.698 | 0.328 | 0.616 |

|

Magnesium | 0.470 | 0.072 | 0.685 | 0.330 | 0.611 |

Logistic regression analysis for RS

incidence

Potential independent risk factors for RS incidence

were analyzed using logistical regression. Univariate analysis

revealed that EN initiation time was associated with RS

(P<0.001). Using a P-value of <0.2 as a cut-off, age, EN

initiation, hypertension, and chronic respiratory disease were

included in the multivariate analysis. It was determined that RS

incidence was 6.530-fold higher in the LEN group compared with that

in the EEN group (OR, 6.530; confidence interval, 2.895-14.727;

P<0.001), suggesting EN initiation as an independent predictor

for RS (Table V).

| Table VUnivariate and multivariate analysis

of risk factors related to refeeding syndrome. |

Table V

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of risk factors related to refeeding syndrome.

| | Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex (female vs.

male) | 1.435

(0.705-2.920) | 0.319 | | |

| Age | 1.019

(0.987-1.053) | 0.145 | 1.013

(0.975-1.053) | 0.497 |

| EN (LEN vs.

EEN) | 6.327

(2.863-13.982) |

<0.001a | 6.530

(2.895-14.727) |

<0.001a |

| Weight | 0.991

(0.964-1.020) | 0.556 | | |

| Body mass

index | 1.012

(0.899-1.139) | 0.843 | | |

| APACHE II

score | 1.013

(0.931-1.102) | 0.766 | | |

| Smoking | 0.263

(0.029-2.419) | 0.238 | | |

| Drinking | 0.871

(0.223-3.409) | 0.843 | | |

| Hypertension | 1.669

(0.824-3.377) | 0.115 | 1.781

(0.792-4.001) | 0.163 |

| Diabetes

mellitus | 1.500

(0.637-3.531) | 0.353 | | |

| Chronic

cardiovascular disease | 0.769

(0.287-2.063) | 0.602 | | |

| Chronic respiratory

disease | 2.333

(0.557-9.777) | 0.146 | 2.182

(0.454-10.494) | 0.330 |

| Mechanical

ventilation | 1.487

(0.735-3.009) | 0.269 | | |

| Calories

intake | 0.999

(0.995-1.003) | 0.550 | | |

| Protein intake | 0.989

(0.952-1.028) | 0.574 | | |

| Admission | | | | |

|

Potassium | 1.350

(0.720-2.529) | 0.350 | | |

|

Sodium | 0.969

(0.911-1.031) | 0.317 | | |

|

Phosphorus | 0.453

(0.062-3.318) | 0.436 | | |

|

Magnesium | 0.289

(0.010-8.266) | 0.468 | | |

Discussion

COVID-19 has brought immeasurable adverse health

effects to the world, including nutritional deficiency, which can

affect as many as 30% of infected patients, according to most

reports. Moreover, if such patients have protein deficiencies or

electrolyte imbalance, their mortality rate will further increase

(9). There are several ways in

which COVID-19 can adversely impact nutrition, digestion and

absorption. First, it has been shown that SARS-CoV-2 binds human

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor on hepatocytes

derived from bile duct epithelial cells, thus causing liver tissue

injury via ACE-2 upregulation (6).

Second, ACE-2 receptors are also expressed on ileum and colon

enterocytes, and proliferation of these cells caused by

viral-mediated ACE-2 activation can disrupt the intestinal flora

(5). Finally, inflammatory

responses to the virus can induce dysbiosis and GI disturbance,

especially diarrhea (4). Several

studies have identified the association between nutritional risk

and mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Zhao et

al (28) reported that

critical COVID-19 patients had significantly higher NRS-2002

scores, leading to longer hospital stays and a higher risk of

mortality. Furthermore, a report by Li et al (16) confirmed the prevalence of

malnutrition in elderly patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. The

nutritional status of the participants was determined by a clinical

nutritionist, and the mean NRS-2002 score was 3, indicating a high

risk of malnutrition and the need for nutritional support (17).

The therapeutic benefits of nutritional support to

reduce the severity of COVID-19 illness has been described by

several recent reviews (15,18-21).

Specifically, experts from ASPEN extrapolated the results of

previous studies and recommended initiating nutritional support

within 24-36 h of admission for critically ill patients with

COVID-19(15). The expert

consensus from the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and

Metabolism suggests that nutritional support could be initiated

within 1-2 days for patients with COVID-19 undergoing mechanical

ventilation therapy (18). Recent

reports have further demonstrated the benefits of early nutritional

support in ICU patients with COVID-19. For instance, Haines et

al (19) found that early

nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients was associated with

faster weaning from mechanical ventilation and decreased length of

stay in the ICU and hospital overall. A meta-analysis by Ojo et

al (20) further concluded

that early nutritional intervention significantly reduced mortality

risk among critically ill patients with COVID-19(20). Additionally, Yuan et al

(21) reported that EEN was the

preferred method of support for elderly patients with common-type

COVID-19(21). Some studies also

suggest that non-critically ill patients would benefit from early

nutritional supplementation, particularly increased protein and

calorie intake through oral supplements (29-31).

Carbohydrates, lipids, amino acid supplements, vitamins and

minerals have been shown to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection

and death (30). For example,

vitamin C supplementation may reduce the susceptibility to lower

respiratory tract infections, while vitamin D could induce

cathelicidins and defensins to inhibit the viral replication rate

(31).

Although EN and PN are the most commonly employed

routes of administration for nutritional support, most clinicians

prefer EN (15). Theoretical

benefits of EN include the preservation of integral mucosal

architecture, gut-associated lymphoid tissue and hepatic immune

function. EN may also reduce inflammatory responses during

nutritional input and prevent antigen leak from the gut, as

previously shown (32). A

practical nutritional guideline for patients with COVID-19,

published by Thibault et al (12), states that EN delivered within 48 h

of ICU admission should be the first-line intervention, while PN

should be prescribed if EN is contraindicated or insufficient

(12). Adequate early EN support

has contributed to improved clinical outcomes in mechanically

ventilated patients with COVID-19(33). For these reasons, EN support was

applied for the most severe COVID-19 cases in Tongji Hospital

during the study period. Patients in the EEN group received EN

support within 2 days of admission and gradually transitioned to

oral nutrition after that. For patients with digestive symptoms or

those at high risk of aspiration, PN support was initiated within

24-48 h and gradually transitioned to EN. In the present cohort, PN

was applied to all patients in the LEN group within 2 days of

admission. Although previous observations have shown that

nutritional supplements administered at an early stage are

important for enhancing host resistance to virus infection, there

is still no consensus on the best time to initiate EN (34). For patients with severe COVID-19

and high nutritional risk, it is difficult to avoid RS after EN

support, even with adequate daily electrolyte supplementation

(35). However, whether there is

an association between EN initiation time and the incidence of RS

is still unclear.

RS encompasses a range of metabolic and electrolyte

imbalances that occur due to the reintroduction or increased

provision of calories after a period of caloric restriction

(22). All patients included in

the study had a reduction of caloric intake with high nutritional

risk upon admission, therefore were at higher risk of RS. To

prevent RS in these patients, the strategy was to provide essential

electrolyte supplementation if they were below a daily threshold.

Furthermore, some measures were also taken to ensure that proper

nutrition and electrolytes were within a normal range during the PN

period, in order to ensure a smooth transition to EN support. Since

RS often occurs within 5 days of reintroduction of calories, serum

electrolytes were monitored 3 days after initiating EN to identify

RS incidence and degree of severity. A time cut-off of 3 days was

chosen since it was the median for peak incidence of the RS. The

relative electrolytes were significantly changed from the start of

monitoring to the end. Hypophosphatemia is often considered the

hallmark of this syndrome owing to the rapid egress of phosphorus

ions from the intravascular to intracellular space after EN

initiation (36). Intracellular

phosphate plays a key role in adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

production and transfer within cells, and increased consumption of

phosphate during refeeding can indirectly lead to reduced ATP and

2,3-diphosphoglycerate generation due to enhanced production of

phosphorylated intermediates, thereby causing impairments in

cardiac and respiratory functions (37). Hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia are

also of equal importance. Decreased serum potassium causes an

imbalance in the electrochemical membrane potential and disturbs

cardiac electromechanical function and nerve impulses, resulting in

abnormal cardiac rhythm and neurotransmitter release (38). Hypokalemia also causes paralysis in

the neuromuscular junction (39).

Serum magnesium is essential for activating the sodium/potassium

ATP-pump (Na+/K+-ATPase), and magnesium

deficiency could aggravate potassium loss in cardiomyocytes,

reflected by lengthening of the PR and QT intervals in an

electrocardiogram (ECG) and widening of the QRS complex, all of

which leads to an increased risk of tachyarrhythmias (40).

In the present study, serum electrolyte and blood

cell values upon hospital admission were similar between the two

groups and were within the normal ranges. Although measures were

taken to maintain electrolyte levels within normal limits before

transitioning to EN, the potential risk of RS could not be entirely

avoided. There were no differences in daily calories or protein

intake, and nutritional content and composition were similar

between groups. BMI, as a commonly used anthropometric index

applied in clinical and research settings, has well-recognized

limitations when used as a standalone marker of nutritional status.

BMI alone does not accurately reflect muscle mass and may obscure

underlying sarcopenia or malnutrition, especially in older adults

or critically ill patients (10,16).

FFMI was therefore included as another nutritional assessment

indicator for the present study. Certain confounding factors, such

as mechanical ventilation and RRT, which can potentially affect

electrolyte balances, were also excluded, since these interventions

were equally administered in both groups. At 3 days post-EN

initiation, the serum electrolyte levels were significantly lower

in the LEN group compared with those in the EEN group. Moreover,

each of these electrolytes was below clinically acceptable levels

in the LEN group, suggesting that delayed EN initiation may have

adverse effects on homeostasis. A significantly higher incidence

and severity of RS was also observed in the LEN group. It was

reasoned that 2 days was the appropriate time interval to

distinguish early from late EN initiation, as studies show that

intestinal dysbacteriosis occurs within 48 h of discontinuing

normal gut nutritional support. Later initiation of EN further

impairs integral mucosal architecture and increases the risk of

bacterial translocation (41).

Delayed EN support is a known risk factor for RS. Notably, the ROC

analysis in the present study found that the AUC for EN was 0.667,

which is favorable for RS prediction. Additionally, logistical

regression demonstrated that the risk of RS was 4-fold higher in

the LEN group compared with that in the EEN group.

Two important physiological processes occur after

initiating EN. Increased insulin secretion drives glucose into

cells, which results in increased uptake of serum phosphorus,

potassium, magnesium, calcium and thiamine. This causes

Na+/K+-ATPase to increase active exchange of

these ions across the plasma membrane (Na+ pumped out

and K+ pumped into the cell). In turn, cellular uptake

of serum phosphorus and magnesium is further increased (42). In light of the aforementioned two

effects, early nutritional support is beneficial for regulating the

body's ability to tolerate changes in the internal environment

following initiation, thereby reducing the likelihood of RS.

The association between EN initiation and mortality

in other respiratory diseases has been widely investigated. Zhong

et al (41) (2017) found

that early EN support could improve nutritional status, decrease

blood glucose fluctuations and further improve the 28-day mortality

rate in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a

common complication of severe COVID-19. Subsequently, Yan et

al (43) (2018) showed a

similar result wherein early EN support reduced the incidence of

infection, improved lung function, and reduced the duration of

mechanical ventilation and length of ICU stay in patients with

ARDS. By contrast, Peterson et al (44) (2017) suggested that early

administration of high-calorie support was associated with

increased mortality in patients with ARDS, while initiating support

after day 8 decreased the risk. An important finding in the present

study was that EEN support was significantly associated with

decreased length of stay in the hospital and in the ICU, without

affecting the 3-month overall survival rate. During the course of

treatments, all patients with severe COVID-19 receive similar

therapies, including respiratory and circulatory monitoring,

electrolyte supplementation and use of glucocorticoids. After

excluding these treatment confounding factors, EEN support showed

no effect on long-term mortality. The patients in the LEN group had

worse GI symptoms, characterized by severe nausea, vomiting and

diarrhea. Given that it takes some time to transition from PN to EN

to ensure EN efficacy and safety, it is not unexpected to see that

the patients in the LEN group took a longer time for proper GI

function, or that they required longer stays in the ICU and in the

hospital.

Finally, to evaluate the safety of early EN

initiation in the present study, the incidence rates of airway

complications and GI intolerance were evaluated. According to an

earlier report, nearly 20% of critically ill patients who received

EN during non-invasive positive pressure ventilation developed at

least one adverse event, including pneumonia and progressive

respiratory failure (43). Efforts

to provide early EN can be further impaired by GI intolerance and

bleeding (44). In the present

study, the incidence of airway complications and GI intolerance

were similar between the two groups, in part owing to the excellent

quality of patient care and regular monitoring provided by the

hospital staff. Collectively, these findings indicate that early EN

can be safely initiated for patients with severe COVID-19 and high

nutritional risk.

The present study has several limitations. First,

only the NRS-2002 clinical scoring tool was used, which, although

validated for identifying malnutrition, does not provide a formal

diagnosis or severity grading. A more recent and globally endorsed

tool named the GLIM criteria offers a standardized diagnostic

framework based on etiological and phenotypic criterion (45), but this was not applied and

measured in the present study, since we could not obtain

comprehensive data regarding the participants' weight losses over

the previous 6-month period. Its inclusion in future studies could

improve diagnostic consistency and enable severity classification.

Second, the retrospective single-center design may introduce

selection bias and limit the generalizability of the present

findings. The observed association between EN interval timing and

RS incidence reflects association, not causation. Moreover, the

study failed to reach a sufficient calculated sample size owing to

limitations in patient volume and implementing inclusion/exclusion

criteria, and as a result, adjustment with Bonferroni's correction

was only applied to a significantly certain criterion

(electrolytes), since it was the most important variable for RS

incidence. Furthermore, due to limited sample sizes within certain

subgroups, stratified analyses were not performed in the current

study, and this may bring about poor stability for the results. To

better address the issue of insufficient sample size, a large,

prospective study is needed to confirm these findings, provided

that patient safety is ensured. Third, the present study population

was limited to patients with severe COVID-19 with NRS scores ≥ 3,

excluding those with milder symptoms or lower nutritional risk. As

a result, the potential benefit of early EN in less severe cases

remains unclear. Fourth, there was no way to determine how long

participants had been undernourished prior to admission, despite

all presenting with high nutritional risk. Additionally, to meet

baseline caloric needs, patients in the LEN group received PN

before EN. This introduced a key limitation, as PN is a known risk

factor for RS owing to its high carbohydrate content and potential

for electrolyte shifts. Therefore, the association between delayed

EN and increased RS incidence may be confounded by prior PN

exposure rather than EN timing alone. The present study design did

not permit full adjustment for this variable, and future studies

should control for PN use either through stratification or

multivariable analysis or compare early PN and EN cohorts

separately to reduce this bias. The lack of propensity score

matching or covariate adjustment must all be acknowledged, as this

may have introduced bias. Causal inference would be strengthened

with larger studies that incorporate these methods. It is also

plausible that routine use of thiamine, multivitamins and

electrolyte management among each patient in their daily lives may

have reduced RS risk, although the extent of this effect could not

be fully assessed in the present retrospective analysis. Lastly,

only 3-month survival rate was recorded in this cohort, and it may

not have been sufficient to adequately differentiate mortality risk

between the EEN and LEN groups. Longer-term outcomes should be

evaluated in future studies.

In conclusion, EN initiation within 2 days after

hospital admission was associated with reduced RS incidence and

decreased length of stay in the hospital and in the ICU, although

this therapy had no effect on overall survival rate at 3 months

post-infection. These findings suggest that early initiation of EN

support is recommended to reduce RS incidence for severely ill

patients with COVID-19 and high nutritional risk if they do not

have EN contraindications.

Supplementary Material

Laboratory examinations 3 days after

EN initiation after adjustment with Bonferroni’s correction. EN,

enteral nutrition; EEN, early EN; LEN, late EN.

*P<0.05.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by the COVID-19 Rapid Response

Research Project of Huazhong University of Science and Technology

(grant no. 2020kfyXGYJ049).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LX contributed to the conception and design of the

research. XR contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the

data. LX and XR contributed to the interpretation of the data. SL

contributed to the statistical analysis. XR and SL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. SL agreed to be accountable for

all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the

accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved. LX and SL drafted the manuscript and

revised it critically for important intellectual content. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was a retrospective study, so the

requirement for informed consent was waived by Tongji Hospital

Ethics Committee (Wuhan, China). The requirement for ethical

approval was also waived by the ethics committee, and clinical

research related to the severe corona virus disease 2019 was

strongly encouraged by Tongji Hospital Affiliated to Tongji Medical

College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang J, Yu M, Tong S, Liu LY and Tang LV:

Predictive factors for disease progression in hospitalized patients

with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. J Clin Virol.

127(104392)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Cambon L, Bergeron H, Castel P, Ridde V

and Alla F: When the worldwide response to the COVID-19 pandemic is

done without health promotion. Glob Health Promot. 28:3–6.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

McDermott KT, Perry M, Linden W, Croft R,

Wolff R and Kleijnen J: The quality of COVID-19 systematic reviews

during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic: An exploratory comparison.

Syst Rev. 13(126)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Aguila EJT, Cua IHY, Fontanilla JAC, Yabut

VLM and Causing MFP: Gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19:

Impact on nutrition practices. Nutr Clin Pract. 35:800–805.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Aguila EJT, Cua IHY, Dumagpi JEL,

Francisco CPD, Raymundo NTV, Sy-Janairo MLL, Cabral-Prodigalidad

PAI and Lontok MAD: COVID-19 and its effects on the digestive

system and endoscopy practice. JGH Open. 4:324–331. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Pan L, Mu M, Yang P, Sun Y, Wang R, Yan J,

Li P, Hu B, Wang J, Hu C, et al: Clinical characteristics of

COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: A

descriptive, cross-sectional, multicenter study. Am J

Gastroenterol. 115(766)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Haq EU, Yu J and Guo J: Frontiers in the

COVID-19 vaccines development. Exp Hematol Oncol.

9(24)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kumar V, Srinivasan V and Kumara S: Smart

vaccine manufacturing using vovel biotechnology platforms: A study

during COVID-19. J Comput Inf Sci Eng. 22(040903)2022.

|

|

9

|

Hakeem R and Sheikh MA: Beyond

transmission: Dire need for integration of nutrition interventions

in COVID-19 pandemic-response strategies in Developing Countries

like Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 36(COVID19-S4):S85–S89.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Martindale R, Patel JJ, Taylor B, Arabi

YM, Warren M and Mcclave SA: Nutrition therapy in critically Ill

patients with coronavirus disease 2019. JPEN J Parenter Enteral

Nutr. 44:1174–1184. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chapple LS, Fetterplace K, Asrani V,

Burrell A, Cheng AC, Collins P, Doola R, Ferrie S, Marshall AP and

Ridley EJ: Nutrition management for critically and acutely unwell

hospitalised patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in

Australia and New Zealand. Aust Crit Care. 33:399–406.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Thibault R, Seguin P, Tamion F, Pichard C

and Singer P: Nutrition of the COVID-19 patient in the intensive

care unit (ICU): A practical guidance. Crit Care.

24(447)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Stachowska E, Folwarski M, Jamioł-Milc D,

Maciejewska D and Skonieczna-Żydecka K: Nutritional support in

coronavirus 2019 disease. Medicina (Kaunas). 56(289)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhang L and Liu Y: Potential interventions

for novel coronavirus in China: A systematic review. J Med Virol.

92:479–490. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wells Mulherin D, Walker R, Holcombe B and

Guenter P: ASPEN report on nutrition support practice processes

with COVID-19: The first response. Nutr Clin Pract. 35:783–791.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Li T, Zhang Y, Gong C, Wang J, Liu B, Shi

L and Duan J: Prevalence of malnutrition and analysis of related

factors in elderly patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Eur J

Clin Nutr. 74:871–875. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cederholm T, Jensen GL, Correia MITD,

Gonzalez MC, Fukushima R, Higashiguchi T, Baptista G, Barazzoni R,

Blaauw R, Coats AJS, et al: GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of

malnutrition-A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition

community. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 10:207–217.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Barazzoni R, Bischoff SC, Breda J,

Wickramasinghe K, Krznaric Z, Nitzan D, Pirlich M and Singer P:

endorsed by the ESPEN Council. ESPEN expert statements and

practical guidance for nutritional management of individuals with

SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Nutr. 39:1631–1638. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Haines K, Parker V, Ohnuma T,

Krishnamoorthy V, Raghunathan K, Sulo S, Kerr KW, Besecker BY,

Cassady BA and Wischmeyer PE: Role of early enteral nutrition in

mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. Crit Care Explor.

4(e0683)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ojo O, Ojo OO, Feng Q, Boateng J, Wang X,

Brooke J and Adegboye ARA: The effects of enteral nutrition in

critically Ill patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Nutrients. 14(1120)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yuan J, Guan Y, Zhao Z, Shen J, Tan D,

Zhao F, Ge L, Xie R and Li T: Enteral nutrition therapy for elderly

patients with common-type COVID-19, a retrospective study based on

medical records. Int Health. 17:678–684. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Da Silva JSV, Seres DS, Sabino K, Adams

SC, Berdahl GJ, Citty SW, Cober MP, Evans DC, Greaves JR, Gura KM,

et al: ASPEN consensus recommendations for refeeding syndrome. Nutr

Clin Pract. 35:178–195. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Meira APC, Santos COD, Lucho CLC,

Kasmirscki C and Silva FM: Refeeding syndrome in patients receiving

parenteral nutrition is not associated to mortality or length of

hospital stay: A retrospective observational study. Nutr Clin

Pract. 36:673–678. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zhu Z, Cai T, Fan L, Lou K, Hua X, Huang Z

and Gao G: Clinical value of immune-inflammatory parameters to

assess the severity of coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Infect Dis.

95:332–339. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Liu F, Li L, Xu M, Wu J, Luo D, Zhu Y, Li

B, Song X and Zhou X: Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive

protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol.

127(104370)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Pourhassan M, Cuvelier I, Gehrke I,

Marburger C, Modreker MK, Volkert D, Willschrei HP and Wirth R:

Risk factors of refeeding syndrome in malnourished older

hospitalized patients. Clin Nutr. 37:1354–1359. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kogo M, Nagata K, Morimoto T, Ito J, Sato

Y, Teraoka S, Fujimoto D, Nakagawa A, Otsuka K and Tomii K: Enteral

nutrition is a risk factor for airway complications in subjects

undergoing noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure.

Resp Care. 62:459–467. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhao X, Li Y, Ge Y, Shi Y, Lv P, Zhang J,

Fu G, Zhou Y, Jiang K, Lin N, et al: Evaluation of nutrition risk

and its association with mortality risk in severely and critically

Ill COVID-19 patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 45:32–42.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Caccialanza R, Laviano A, Lobascio F,

Montagna E, Bruno R, Ludovisi S, Corsico AG, Di Sabatino A,

Belliato M, Calvi M, et al: Early nutritional supplementation in

non-critically ill patients hospitalized for the 2019 novel

coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Rationale and feasibility of a

shared pragmatic protocol. Nutrition. 74(110835)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Grant WB, Lahore H, Mcdonnell SL, Baggerly

CA, French CB, Aliano JL and Bhattoa HP: Evidence that vitamin D

supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19

infections and deaths. Nutrients. 12(988)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Rozga M, Cheng FW, Moloney L and Handu D:

Effects of micronutrients or conditional amino acids on

COVID-19-related outcomes: An evidence analysis center scoping

review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 121:1354–1363. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ohbe H, Jo T, Matsui H, Fushimi K and

Yasunaga H: Early enteral nutrition in patients undergoing

sustained neuromuscular blockade: A propensity-matched analysis

using a nationwide inpatient database. Crit Care Med. 47:1072–1080.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Melchers M, Hubertine Hermans AJ, Hulsen

SB, Kehinde Kouw IW and Hubert van Zanten AR: Individualised energy

and protein targets achieved during intensive care admission are

associated with lower mortality in mechanically ventilated COVID-19

patients: The COFEED-19 study. Clin Nutr. 42:2496–2492.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Seres DS, Valcarcel M and Guillaume A:

Advantages of enteral nutrition over parenteral nutrition. Therap

Adv Gastroenterol. 6:157–167. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Alexander J, Tinkov A, Strand TA, Alehagen

U, Skalny A and Aaseth J: Early nutritional interventions with

zinc, selenium and vitamin D for raising anti-viral resistance

against progressive COVID-19. Nutrients. 12(2358)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ribeiro AC, Dock-Nascimento DB, Silva JM

Jr, Caporossi C and Aguilar-Nascimento JE: . Hypophosphatemia and

risk of refeeding syndrome in critically ill patients before and

after nutritional therapy. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 66:1241–1246.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ponzo V, Pellegrini M, Cioffi I, Scaglione

L and Bo S: The refeeding syndrome: A neglected but potentially

serious condition for inpatients. A narrative review. Intern Emerg

Med. 16:49–60. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Matthews-Rensch K, Capra S and Palmer M:

Systematic review of energy initiation rates and refeeding syndrome

outcomes. Nutr Clin Pract. 36:153–168. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

De Silva A and Nightingale JMD: Refeeding

syndrome: Physiological background and practical management.

Frontline Gastroenterol. 11:404–409. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yoshida M, Izawa J, Wakatake H, Saito H,

Kawabata C, Matsushima S, Suzuki A, Nagatomi A, Yoshida T, Masui Y

and Fujitani S: Mortality associated with new risk classification

of developing refeeding syndrome in critically ill patients A

cohort study. Clin Nutr. 40:1207–1213. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zhong C, Ji C, Dai Z, Fu K, Wen X and Pan

H: Effect of early enteral nutrition standardized treatment on

blood glucose and prognosis in acute respiratory distress syndrome

patients with mechanical ventilation. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji

Jiu Yi Xue. 29:1133–1137. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

42

|

Ghaddar R, Chartrand J, Benomar A,

Jamoulle O, Taddeo D, Frappier JY and Stheneur C: Excessive

laboratory monitoring to prevent adolescent's refeeding syndrome:

Opportunities for enhancement. Eat Weight Disord. 25:1021–1027.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Guo Y, Cheng J and Li Y: Influence of

enteral nutrition initiation timing on curative effect and

prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome patients with

mechanical ventilation. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue.

30:573–577. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Peterson SJ, Lateef OB, Freels S, Mckeever

L, Fantuzzi G and Braunschweig CA: Early exposure to recommended

calorie delivery in the intensive care unit is associated with

increased mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress

syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 42:739–747. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Yildirim M, Halacli B, Yuce D, Gunegul Y,

Ersoy EO and Topeli A: Assessment of admission COVID-19 associated

hyperinflammation syndrome score in critically-III COVID-19

patients. J Intensive Care Med. 38:70–77. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|