Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an autosomal recessive

hematologic disorder caused by a single nucleotide mutation,

leading to the production of abnormal hemoglobin S (HbS). First

described by Dr Herrick in 1910, this mutation replaces glutamic

acid with valine in the β-globin chain, altering red blood cell

shape and function. Under hypoxic or acidic conditions, these cells

sickle, triggering vaso-occlusive crises, hemolysis and multi-organ

dysfunction (1).

SCD comprises several genotypes, with sickle cell

anemia (HbSS) being the most prevalent (70%), followed by

hemoglobin SC disease (HbSC) and sickle β-thalassemia

(HbS/β-thalassemia). The severity of symptoms varies, with HbSS

being the most severe. HbSC results from inheriting an HbS allele

from one parent and hemoglobin C from the other, typically causing

a milder course. In HbS/β-thalassemia, severity depends on the

degree of β-globin production (1).

Globally, SCD remains a major health challenge,

particularly in malaria-endemic regions, where the sickle cell

trait provides a survival advantage against malaria. Each year,

>500,000 infants are born with SCD, with the highest prevalence

in Sub-Saharan Africa, India, the Mediterranean and the Middle East

(2,3).

The disease's pathophysiology is driven by HbS

polymerization, which stiffens red blood cells, reducing

flexibility and increasing their tendency to block small vessels.

This leads to ischemia, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.

Chronic hemolysis releases free hemoglobin into the circulation,

depleting nitric oxide (NO), which worsens vasoconstriction and

vascular injury. Adhesion molecules such as selectins further

contribute to vaso-occlusion and disease progression (4).

SCD manifests through acute and chronic

complications. The hallmark is vaso-occlusive crises, characterized

by severe pain, anemia, fatigue, jaundice and increased

susceptibility to infections, particularly from encapsulated

bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus

influenzae. Long-term complications include pulmonary

hypertension, left-sided heart disease, stroke, renal impairment,

avascular necrosis and growth delays (1). Among the most severe complications is

acute chest syndrome (ACS), an acute lung injury presenting with

respiratory distress, fever and hypoxia. It is a leading cause of

morbidity and mortality in SCD and can be triggered by infections,

pulmonary vasoconstriction and fat embolism. Management includes

oxygen therapy, hydration, analgesics, broad-spectrum antibiotics

and, in severe cases, blood transfusions (1,5).

Diagnosing asthma in patients with SCD presents a

unique clinical challenge due to overlapping respiratory

manifestations. Symptoms such as wheezing, cough and

dyspnea-typical of asthma-are also common during vaso-occlusive

crises and episodes of ACS, both of which are prevalent in SCD.

These overlapping features can lead to misclassification or delayed

diagnosis. Furthermore, pulmonary function testing may reveal

restrictive or obstructive patterns in SCD that do not clearly

align with classic asthma profiles, further complicating

differentiation (6). Additionally,

chronic airway inflammation due to SCD itself may mimic or mask

asthma, and standard biomarkers such as elevated IgE or

eosinophilia may be variably expressed (6), necessitating a multifaceted

diagnostic approach incorporating spirometry, detailed history and

longitudinal symptom monitoring (6).

Asthma is a common comorbidity in SCD, further

complicating disease management. It exacerbates airway

inflammation, increasing the risk of hypoxia, vaso-occlusive events

and ACS. Patients with SCD and asthma or recurrent wheezing have

higher rates of painful crises, stroke and mortality (7). The mechanisms linking asthma and ACS

include chronic airway inflammation, heightened vulnerability to

respiratory infections and exacerbation of pulmonary complications

(6).

Cohort studies and biomarker research have

emphasized the immunological and pulmonary complexity in patients

with both SCD and asthma. It has been demonstrated that increased

eosinophilic airway inflammation, as evidenced by elevated

fractional exhaled NO (FeNO) and sputum eosinophils, is

significantly associated with higher rates of ACS in children with

SCD (8). Furthermore, convergence

points within key inflammatory signaling pathways have been

identified. For instance, the activation of signal transducer and

activator of transcription 6 by interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13, a

well-established mechanism in asthma, was highlighted.

Additionally, the nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of

activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway, which plays a central role in

regulating immune responses, was found to be active in both SCD and

asthma. These shared molecular pathways suggest potential

overlapping mechanisms of inflammation between the two conditions

(9).

Recognizing ACS as a significant complication of SCD

highlights the need for further research into its risk factors and

optimal management. The link between asthma and ACS is particularly

critical. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, in the present study,

the first meta-analysis was conducted to quantify ACS risk in

patients with SCD and asthma.

Materials and methods

General

This systematic review and meta-analysis was

conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (10) and the Meta-analysis Of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (11). This systematic review has been

registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic

Reviews (PROSPERO; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) with ID no.

CRD420251012367.

Search strategy

Articles were searched in the electronic databases

PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Cochrane library

(https://www.cochrane.org/) and Scopus

(https://www.scopus.com/home.uri?zone=header&origin=sbrowse),

as well as gray literature, including conference proceedings, from

inception until the 4th of March, 2025. No restriction regarding

sample size, study setting or publication language was imposed.

MeSH terms were used for both intervention (asthma) and outcome

(ACS), along with free-text words. The Boolean operators ‘OR’ and

‘AND’ were also used. The detailed search strategy applied in

PubMed is presented in Table SI.

Equivalent search terms and Boolean logic were adapted and applied

appropriately to the Cochrane Library, Scopus and gray literature

sources to ensure consistency across databases.

Eligibility criteria

Studies enrolling patients with SCD and asthma of

any age with asthma, compared with patients with SCD without

asthma, assessing ACS episodes, were searched for. Case reports,

case series, previous meta-analyses (if any), editorials, opinion

papers and narrative reviews were excluded.

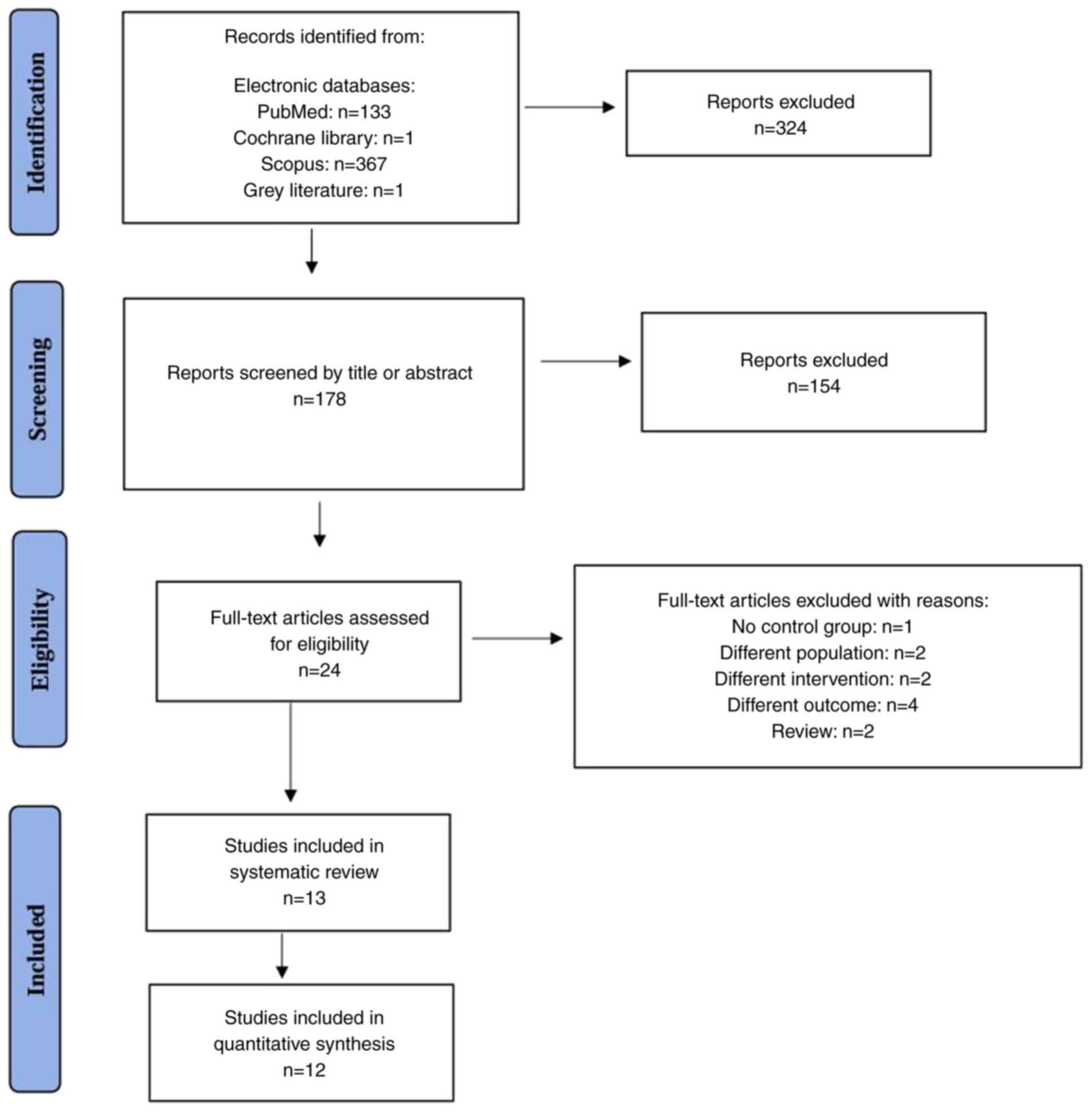

PRISMA screening process

A total of 501 records were identified from

electronic databases: PubMed (n=133), Cochrane Library (n=1),

Scopus (n=367) and grey literature (n=1). After removing

duplicates, 178 records remained for screening.

During the screening process, 178 records were

reviewed based on titles and abstracts and 154 were excluded. This

left 24 full-text articles for eligibility assessment. Of these 24

full-text articles, 11 were excluded for the following reasons: 1

lacked a control group; 2 included a different intervention (i.e.,

they evaluated asthma treatment efficacy without specifically

assessing its association with ACS); 2 included populations without

confirmed SCD; 4 examined outcomes other than ACS (e.g., general

hospitalization rates or pulmonary function indices); and 2 were

narrative review articles rather than original research.

Ultimately, 13 studies were included in the systematic review and

12 were included in the quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis).

The flowchart of the study selection process is

illustrated in Fig. 1.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (12) was used by two independent reviewers

(T-VK, KD) to assess the quality of the included observational

studies. The included studies were evaluated based on the following

broad perspectives: Study groups, group comparability and

ascertainment of either the exposure or outcomes of interest.

According to the NOS, studies are evaluated across three domains:

Selection (maximum 4 stars), comparability (maximum 2 stars) and

outcome/exposure (maximum 3 stars), for a total of up to 9 stars. A

higher number of stars indicates higher methodological quality and

lower risk of bias. Studies scoring 7-9 stars were considered high

quality, 4-6 stars moderate quality and <4 stars low quality.

The individual scores for each study are presented in Tables SII and SIII. Divergent views among reviewers

were settled through debate, consensus or arbitration by a third

senior reviewer (VEG).

Data extraction

A total of three independent reviewers (TVK, KD,

VEG) extracted the data from the eligible reports. Relevant

information was extracted and recorded in a data collection form

developed in Excel© (Microsoft Corp.). Extracted

information included the following: First author, year of study

conduction, country of origin, study sample size, key clinical

outcome (ACS), diagnostic method of asthma and ACS.

Data synthesis and analysis

The study aimed to assess the major clinical

endpoint (ACS) representing a dichotomous variable; thus, the risk

ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was estimated. To

generate the pooled estimates of the outcome, the Mantel-Haenszel

random-effects formula was implemented. The I2 statistic

was used for the evaluation of the extent to which statistical

heterogeneity in a meta-analysis is due to differences among

studies. Low heterogeneity was present if I2 was between

0 and 25%, moderate if I2 was between 25 and 50%, or

high if I2 was >75%. Forest plots were created for a

visual representation of the presence and nature of statistical

heterogeneity (13). All analyses

were performed with the Meta-Mar software (version 3.5.1) (14) and P<0.05 was considered to

indicate statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of the included

studies

A detailed description of characteristics of the

included studies (8,15-26)

is provided in Table I. In cases

where the number of episodes of ACS per patient per year was

available, appropriate calculations were made in order to determine

the number of events in the asthma group and in the non-asthma

group. The inclusion of the study by Strunk et al (22) in the meta-analysis was not

possible, as the number of ACS episodes per group was unknown.

However, it should be noted that the result of this study (patients

with SCD and asthma had a higher risk of ACS) was similar to that

of the present meta-analysis. Regarding the outcome ACS, data were

combined from 12 studies with a total of 2,269 enrolled subjects,

of which 497 (21.9%) had asthma. Overall, 725 episodes of ACS were

recorded. Among patients with SCD and asthma, 270 out of 497

(54.3%) experienced at least one episode of ACS. By contrast, the

proportion of ACS among patients with SCD without asthma was

significantly lower, at 25.7%.

| Table ICharacteristics of the included

studies. |

Table I

Characteristics of the included

studies.

| First author,

year | Design | Country | SCD type | Age | A/NA subjects | Follow-up | ACS episodes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| De, 2023 | Retrospective | USA | HbSS 85.5%, HbSC

9.1%, HbSB 3.6%, HbS/HPFH 1.8%, | 3-18 y | 16/39 | 2 y | A: 13 NA: 27 | (8) |

| Boyd, 2004 | Retrospective

case-control | USA | HbSS HbSβ HbSC | 2-21 y | 31/108 | - | A: 22 NA: 41 | (15) |

| Knight-Madden,

2005 | Retrospective | Jamaica | HbSS | 5-10 y | 38/42 | - | A: 38 NA: 3 | (16) |

| Boyd, 2006 | Prospective | USA | HbSS | <6 m at

entry | 49/242 | 11.7 y | A: 19 NA: 48 | (17) |

| Sylvester,

2007 | Retrospective | UK | HbSS | <18 y | 12/153 | - | A: 6 NA: 27 | (18) |

| Bartram, 2008 | Retrospective | UK | HbSS HbSC | 1-15 y | 16/47 | - | A: 10 NA: 12 | (24) |

| Bernaudin,

2008 | Retrospective | France | HbSS | 0-18 y | 25/272 | 6-7 y | A: 18 NA: 118 | (25) |

| An, 2011 |

Cross-sectional | North America,

Europe | HbSS 94%, HbSβο

6% | 5-14 y | 140/381 | - | A: 27 NA: 46 | (19) |

| Glassberg,

2012 | Retrospective | USA | HbSS 68.4%, HbSβο

10.5%, HbSβ+ 7.9%, HbSC 13.2% | 6 m-67.5 y | 48/214 | - | A: 16 NA: 37 | (20) |

| Intzes, 2013 | Retrospective | USA | HbSS 79.6%, HbSβο

3.2%, HbSβ+ 14.1%, HbSC 30.2% HbSα 1.1% | 5-18 y | 58/61 | - | A: 45 NA: 9 | (21) |

| Strunk, 2014 | Prospective | USA, UK | HbSS HbSβ | 4-18 y | 53/134 | 4.61±1.16 y | IRR=2.21 (CI 95%

1.31-3.76) | (22) |

| Pahl, 2016 | Retrospective | USA | HbSS HbSβο HbSβ+

HbSC | 2-21 y | 29/73 | - | A: 23 NA: 17 | (26) |

| Bafunyembaka,

2024 | Retrospective

nested case control | French Guiana | HbSS HbSβ+

HbSC | 6 m-18 y | 35/140 | - | A: 33 NA: 70 | (23) |

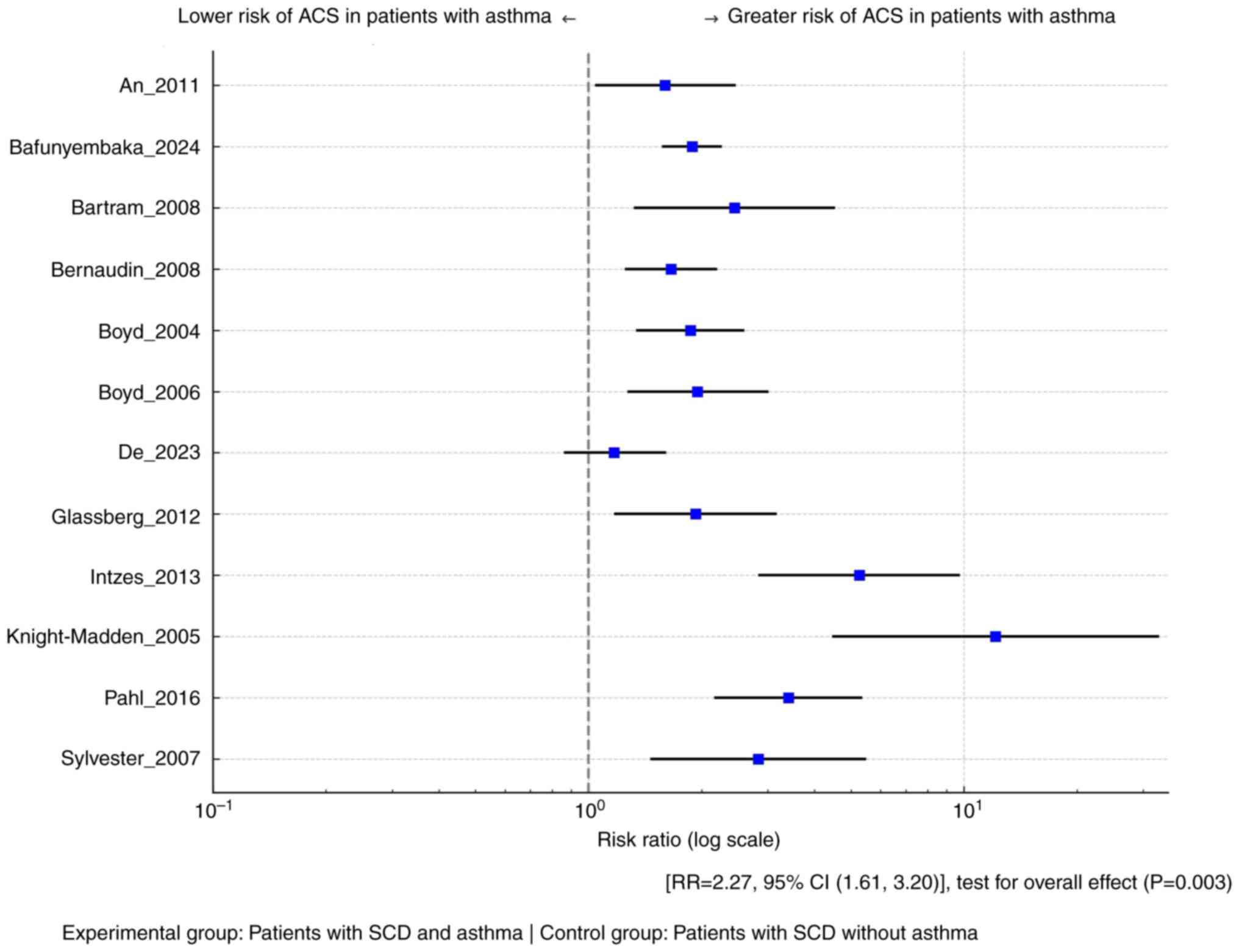

Meta-analysis

As presented in Fig.

2, it was demonstrated that asthma is associated with a

significantly higher risk for ACS in patients with SCD [RR=2.27,

95% CI (1.61, 3.20)], with the test for the overall effect

confirming statistical significance (P=0.0003). The heterogeneity

of the included studies was substantial (I2=74%). The

funnel plot is provided in Fig.

S1.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

Subgroup analysis revealed that studies with a

prospective design exhibited no heterogeneity (I²=0%), indicating

that the overall heterogeneity observed in the meta-analysis

originated primarily from retrospective studies. To further explore

this, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding the studies

by Knight-Madden et al (16) and Intzes et al (21), which contributed substantially to

heterogeneity in the retrospective group. This exclusion reduced

the I² of the retrospective subgroup from 85.5 to 68%, confirming

their disproportionate influence on variability. Following these

exclusions, 10 studies remained, comprising 401 participants in the

asthma (experimental) group and 1,669 in the non-asthma (control)

group. Using a Mantel-Haenszel random-effects model, the pooled RR

for ACS was 1.88 (95% CI: 1.59-2.24), demonstrating a significantly

increased risk in the asthma group (P<0.05). Moderate

heterogeneity was detected (I²=52%, P=0.03), indicating that just

over half of the observed variation among studies was due to real

differences rather than chance (Figs.

S2 and S3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic

evaluation and meta-analysis of the association between asthma and

ACS episodes. A notable systematic review and qualitative analysis

of the existing evidence was presented in 2016 by DeBaun and Strunk

(6), who performed a literature

search in PubMed investigating the association between asthma and

ACS in children with SCD. The authors concluded that asthma is

common in children with SCD, leading to higher rates of severe

vaso-occlusive pain and ACS and indicating that there is strong

justification for routinely assessing asthma risk factors and

symptoms at each clinic visit and that spirometry should complement

respiratory histories to detect and monitor lower airway

obstruction and treatment responses. Three years later, Willen

et al (27) reported on the

relationship between asthma and ACS in their review article,

focusing on three important studies (17,19,22).

More specifically, the study by Willen et al (27) found that a physician's diagnosis of

asthma in children with SCD is significantly associated with

increased incidence of both vaso-occlusive pain episodes and ACS.

The analysis of three major cohorts including 1,685 children

demonstrated a 1.89-fold increased risk of ACS [incidence rate

ratio=1.89; 95% CI: 1.61-2.22; P<0.001] among those with asthma.

The authors emphasized that pulmonary symptoms-whether due to

asthma or asthma-like features-substantially contribute to SCD

morbidity and warrant routine respiratory screening and specialist

referral (27).

The present study demonstrates a statistically

significant association between asthma and an increased risk of ACS

in patients with SCD, with a pooled RR of 2.27 (95% CI: 1.31-3.20;

P=0.0003). By synthesizing all available observational data, this

meta-analysis provides the first quantitative estimate of ACS risk

in patients with asthma and SCD, contributing valuable evidence to

the existing literature.

This finding is particularly important given the

complex interplay between asthma and the pulmonary complications

associated with SCD. The underlying mechanisms for this association

warrant further exploration. Understanding the potential

pathogenetic relationship between these two conditions is crucial

for improving clinical outcomes and guiding management

strategies.

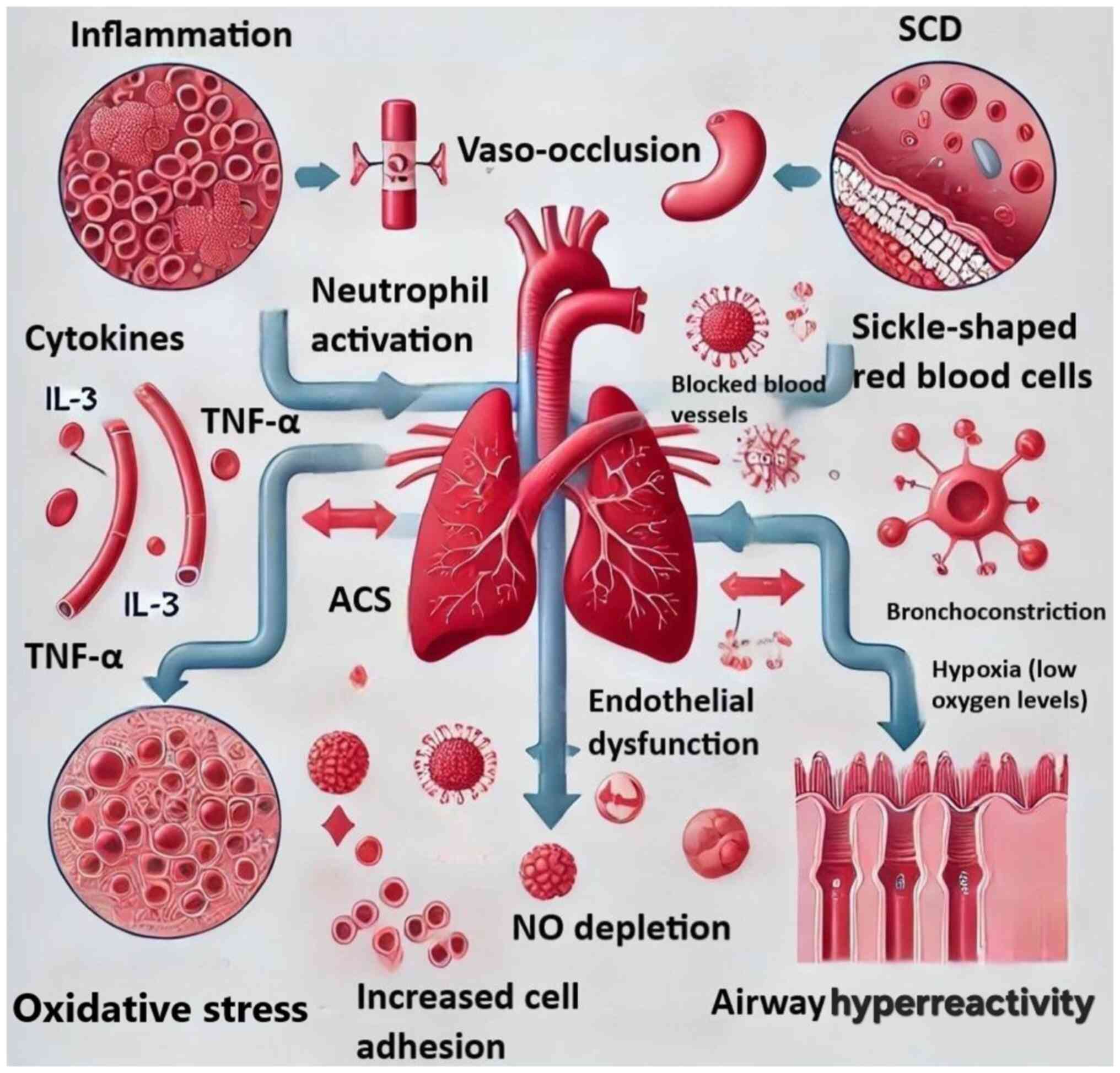

Asthma and SCD exhibit several similarities

regarding the immunological factors linked to their disease states.

Both conditions lead to inflammation and airway hyperreactivity,

affect vulnerability to respiratory infections and necessitate

targeted interventions to alleviate their associated complications

(7,28). The link between asthma and ACS in

patients with SCD can be possibly unraveled through several

interrelated mechanisms, including inflammation, hypoxemia,

oxidative stress and vascular complications (7).

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition

characterized by persistent inflammation that activates a range of

immune cell types, including eosinophils, mast cells and T

lymphocytes. This inflammatory reaction produces cytokines and

chemokines, which enhance bronchial hyperreactivity and airway

obstruction, imitating or intensifying ACS symptoms, including

dyspnea and chest pain. SCD also has higher levels of endothelial

activation markers, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Shared inflammatory pathways

between SCD and asthma may result in an asthma-like phenotype in

patients with SCD, potentially increasing the likelihood of

developing asthma. Exacerbation of airway inflammation caused by

asthma may significantly increase the possibility of developing ACS

in patients with SCD who are already at risk of pulmonary

complications due to vaso-occlusive crises and impaired gas

exchange (8,29).

Endothelial activation and oxidative stress are

critical processes that connect sickled red blood cells with

vaso-occlusion. Sickle cells bind to endothelium integrins,

inducing damage via reactive oxygen species and sustaining

additional endothelial activation. This mechanism causes the influx

of monocytes and neutrophils, which contributes to increased cell

adhesion in patients with SCD. The combination of sickling and

inflammation can worsen vascular integrity, increasing the risk of

an ACS. SCD is characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, such as IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), as well as steady-state levels

of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and other cytokines. Increased

neutrophil counts contribute to acute lung injury by forming

neutrophil extracellular traps, which worsens pulmonary functioning

and infection susceptibility (9).

Asthma may exacerbate SCD-related vascular issues.

Inflammation and oxidative stress may cause endothelial

dysfunction, which is a precursor to atherosclerosis and acute

coronary events. In patients with SCD, the combination of sickling

and inflammation can worsen vascular integrity, increasing the risk

of ACS. Furthermore, asthma can cause hemodynamic changes such as

increased heart rate and blood pressure fluctuations, which can

contribute to cardiovascular stress. Asthma can increase acute

coronary events in patients with SCD, whose cardiovascular systems

are already stressed by chronic hemolysis and vaso-occlusive crises

(30).

Although the present discussion outlines

inflammation, hypoxemia, oxidative stress and vascular

complications as potential mechanisms linking asthma to ACS in

patients with SCD, a deeper exploration of molecular pathways can

provide clearer targets for intervention. Inflammatory mediators

play a central role in both asthma and SCD-related pulmonary

events. In asthma, allergen-induced activation of type 2 T-helper

(Th2) cells leads to the release of interleukins such as IL-4, IL-5

and IL-13, promoting eosinophilic inflammation, mucus production

and airway hyperresponsiveness (9,28).

In patients with SCD, a parallel increase in pro-inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-3, TNF-α and GM-CSF is observed (9,30),

which contributes to neutrophil activation and adhesion to the

endothelium, further exacerbating vascular occlusion. These

cytokines converge on NF-κB, a key transcription factor regulating

inflammatory gene expression. Activation of NF-κB in both airway

epithelial cells and endothelial cells promotes a pro-inflammatory

milieu conducive to ACS onset (9).

Furthermore, oxidative stress from repeated hemolysis in SCD

diminishes NO bioavailability, impairing vasodilation and

amplifying endothelial injury, while concurrently asthma-associated

hypoxemia further aggravates pulmonary vasoconstriction (30). Collectively, these overlapping

pathways-particularly those involving IL-5 and GM-CSF signaling in

eosinophils and neutrophils-highlight actionable targets such as

anti-IL-5 or NF-κB inhibitors.

It is important to consider how age influences the

risk of ACS among patients with both asthma and SCD. The majority

of included studies focused on pediatric populations, with most

participants being children or adolescents. Evidence suggests that

the risk of ACS is highest in early childhood and tends to decline

with age (6). This may be due to

developmental changes in lung structure, immune response maturation

and a reduced frequency of upper respiratory infections, which are

common triggers for both asthma exacerbations and ACS in younger

children. Boyd et al (17)

conducted a prospective study with a median follow-up of 11.7

years, while Bernaudin et al (25) reported follow-up durations of 6-7

years in a large pediatric cohort. These extended observation

periods enabled the identification of asthma-related complications

well into adolescence and early adulthood. The findings from these

cohorts support the hypothesis that younger children with SCD and

coexisting asthma are particularly susceptible to ACS. This

increased vulnerability likely stems from age-related physiological

factors, including heightened airway hyperresponsiveness,

underdeveloped immune regulation and narrower airway calibers,

which interact with the pro-inflammatory and vaso-occlusive state

characteristic of SCD.

Incorporating recent molecular evidence also

broadens the implications of the present findings. The work by

Habib et al (28) and De

et al (8) supports a

precision medicine approach, where monitoring Th2 cytokines and

airway eosinophilic activity may guide tailored interventions in

patients with SCD with asthma. This is crucial in light of the

emerging evidence that biologics such as anti-IL-5 or anti-IL-13

agents (e.g., mepolizumab, dupilumab) not only reduce asthma

exacerbations but may also minimize inflammatory triggers of ACS

(28). Similarly, Pahl and Mullen

(26) reported differential ACS

risk based on genotype (HbSS vs. HbSC), suggesting that genetic

stratification should be combined with the asthma phenotype for

effective risk assessment and personalized treatment planning.

The present results underscore the importance of

comprehensive management of asthma in patients with SCD. While the

study demonstrates a significant association between asthma and

ACS, it is important to acknowledge potential limitations.

Substantial heterogeneity of the studies included in the present

meta-analysis was noted. Variations in study design should be

highlighted, as some of the studies were cohort studies, either

prospective or retrospective, and others were case-control and

cross-sectional studies. The retrospective design frequently lacks

complete access to risk factor data and comorbidities. Population

variability was also present, as the studies enrolled participants

with different characteristics, such as age (ranging from infancy

to elderly) and geographic contexts. Furthermore, the duration of

asthma diagnosis was different among studies, which can also lead

to varied outcomes. Of course, random variation should be

acknowledged, as some heterogeneity may be due to random chance,

particularly in the present study, where the number of the pooled

studies is relatively small. Nonetheless, the present findings

should be highlighted, even if they need to be verified in future

large-scale prospective, well-designed studies.

One of the primary strengths of the present

meta-analysis is its comprehensive approach to synthesizing

existing research. By systematically reviewing numerous studies in

the SCD field, the precision of the estimates was increased, which

enhances the reliability of the conclusions drawn in the present

study. This large sample size allows for more robust

generalizations. In addition, the inclusion of diverse study

designs and populations strengthens the external validity of the

present findings. By aggregating data from various settings, it is

possible to better understand the broader implications of the

results and their applicability across different demographic

groups. Another significant advantage of this meta-analysis is the

rigorous methodology employed throughout the research process. A

comprehensive literature search was conducted, adhering to

established guidelines for meta-analyses. This careful selection

process helped ensure that the studies included were of high

quality and relevant to the research question. Furthermore, the use

of advanced statistical techniques allowed for the assessment of

heterogeneity and publication bias, providing a more nuanced

understanding of the data. By aggregating results from various

studies, a more unified perspective on the topic was offered, which

is beneficial for both researchers and practitioners. This

synthesis not only reinforces existing evidence but also highlights

areas where further research is needed, guiding future

investigations in the fields. While this meta-analysis provides

strong evidence of a significant association between asthma and

increased risk of ACS in patients with SCD, the generalizability of

these findings may be influenced by variations in demographic and

geographic factors. Most of the included studies were conducted in

specific populations, often in high-income countries with

predominantly African or African-American cohorts. Future research

should aim to validate these findings across diverse ethnic and

geographic groups to ensure broader applicability. A well-designed,

multicenter, prospective cohort study encompassing diverse clinical

settings and populations would offer a more comprehensive

understanding of how asthma modifies ACS risk in the global SCD

population. Such an approach would also allow the evaluation of

potential interactions between genetic, environmental and

socio-economic determinants that may influence disease severity and

comorbidity burden.

Furthermore, although this review suggests a

biological interplay between asthma and ACS, the causal mechanisms

remain inadequately understood. The overlap in clinical

presentation between asthma exacerbations and early ACS episodes

adds to the diagnostic complexity and may contribute to

under-recognition or misclassification. To explore the underlying

pathophysiology in greater depth, future studies should incorporate

translational approaches, including animal models and in

vitro experiments. These models can help delineate the specific

roles of airway inflammation, eosinophilic activity, oxidative

stress and endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of ACS among

individuals with coexisting asthma and SCD. Additionally,

population-based interventional studies, such as randomized

controlled trials evaluating asthma-specific therapies (e.g.,

inhaled corticosteroids or leukotriene inhibitors) in patients with

SCD, would be valuable in determining whether asthma management can

effectively reduce the incidence or severity of ACS episodes.

Another important consideration to be addressed in

future studies is the possible inconsistency of the asthma

diagnostic criteria, ranging from self-reported asthma history to

physician-diagnosed cases without standardized pulmonary function

testing, which can lead to misclassification and impact the

strength of the observed association between asthma and ACS. To

enhance the validity and reproducibility of future findings, it is

essential that unified and clearly defined asthma diagnostic and

evaluation criteria are employed. Ideally, studies should

incorporate objective measures such as spirometry, bronchodilator

responsiveness and biomarkers of airway inflammation to ensure

accurate asthma classification. Standardizing asthma diagnosis will

not only reduce methodological bias but also facilitate more robust

cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses, ultimately contributing

to a clearer understanding of the interplay between asthma and ACS

in SCD.

Although subgroup or meta-regression analyses could

potentially help identify sources of heterogeneity, the current

meta-analysis was limited by the small number of included studies

and the incomplete reporting of relevant stratifying variables,

such as age, region, gender and genotype. These limitations

restricted the feasibility and statistical power of conducting such

additional analyses. However, the significant heterogeneity

observed highlights the need for future research that incorporates

more detailed and standardized demographic and clinical data,

enabling more granular subgroup analyses. Large-scale, multicenter

cohort studies with harmonized reporting standards would be

particularly valuable for disentangling the influence of various

factors on the relationship between asthma and ACS in patients with

SCD. The convergence of inflammatory mediators, endothelial

dysfunction and oxidative stress represents a mechanistic continuum

linking asthma and ACS in SCD. By visually consolidating these

interactions, Fig. 3 serves as a

conceptual tool for clinicians and researchers evaluating

therapeutic targets such as IL-5 inhibition or NF-κB pathway

modulation.

Although the association between asthma and

increased risk of ACS in SCD is well established, future research

should focus on elucidating the underlying pathophysiological

mechanisms and developing targeted interventions. Chronic hemolysis

and NO depletion in SCD contribute to endothelial dysfunction,

while Th2-driven airway inflammation in asthma-characterized by

elevated IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13-promotes eosinophilic infiltration,

mucus overproduction and airway hyperreactivity (6,17,25).

These converging pathways exacerbate pulmonary vascular occlusion,

leading to ACS. Furthermore, asthma-related hypoxemia may amplify

sickling and microvascular adhesion, further increasing pulmonary

complications (8,9).

To improve outcomes, future clinical studies should

evaluate whether biomarker-guided asthma management (e.g., FeNO or

eosinophil counts) reduces ACS incidence in SCD. Investigations

into leukotriene receptor antagonists and biological therapies

targeting IL-5 or IL-4/IL-13 signaling are also warranted, as these

may modulate the shared inflammatory environment. Additionally,

integrated treatment strategies combining disease-modifying

therapies such as hydroxyurea with optimized asthma control should

be explored to determine their synergistic potential in preventing

ACS.

A key limitation of this meta-analysis is the

presence of substantial heterogeneity (I²=74%) across the included

studies. Although subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed,

more advanced statistical approaches such as meta-regression were

not conducted. Such analyses could have provided deeper insights

into potential sources of heterogeneity, including age

distribution, sickle cell genotypes, asthma diagnostic methods and

regional or ethnic differences among study populations (13,15,17).

Future meta-analyses incorporating these variables could help

clarify their individual contributions and improve the precision of

pooled estimates.

Another important limitation is the inconsistency in

asthma diagnostic criteria across the included studies. While

certain studies relied on self-reported asthma history, others used

physicians' diagnosis, and only a minority incorporated objective

assessments such as spirometry, bronchodilator responsiveness or

airway inflammatory biomarkers (16,18,21).

This variability increases the likelihood of diagnostic

misclassification, which could have influenced the observed

association between asthma and acute chest syndrome. Standardizing

diagnostic approaches in future research-ideally using objective

pulmonary function tests and validated biomarkers-will be essential

to improve the reliability and reproducibility of results.

A further limitation of this meta-analysis is that

it focused exclusively on the risk of ACS occurrence without

evaluating how asthma may influence the severity of ACS episodes.

Clinically relevant outcomes such as the duration of

hospitalization, need for intensive care unit admission,

requirement for mechanical ventilation or mortality were not

consistently reported across studies and, therefore, could not be

included in the pooled analysis (17,20,25).

Incorporating these severity-related endpoints in future research

would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the clinical

impact of asthma in patients with sickle cell disease and better

inform risk stratification and management strategies.

Another methodological limitation concerns the

assessment of publication bias. Although a funnel plot was

presented, no quantitative statistical tests, such as Egger's

regression test or Begg's rank correlation test, were performed to

evaluate the potential presence of small-study effects (13,14).

The absence of these tests limits the objectivity of the

publication bias assessment and may leave residual uncertainty

regarding the robustness of the pooled estimates. Future

meta-analyses should incorporate both graphical and statistical

methods for publication bias evaluation to strengthen the validity

of their conclusions.

Finally, although subgroup analyses based on study

design were performed, the statistical power of these analyses was

not assessed or reported. This omission raises concerns that some

non-significant findings may reflect insufficient power rather than

a true absence of association (12,15,19).

Future studies should predefine subgroup analyses and ensure

adequate sample sizes to detect clinically meaningful differences,

thereby minimizing the risk of false-negative results and enhancing

the interpretability of subgroup findings.

In conclusion, the association between asthma and

ACS in patients with SCD highlights the need for heightened

awareness and targeted management of asthma in this population. By

addressing asthma as a significant comorbidity, healthcare

providers can potentially mitigate the risk of ACS and improve the

overall health and quality of life for individuals with SCD. The

present results have clinical implications, as careful evaluation

by a respiratory medicine specialist should be included in patient

monitoring and assessment, so that asthma is diagnosed early and is

appropriately treated. The significant association between asthma

and increased risk for ACS in patients with SCD highlights a

critical area for clinical attention and further research.

Supplementary Material

Funnel plot assessing publication

bias. Funnel plot of standard error against risk ratio for the

included studies examining the association between asthma and acute

chest syndrome in patients with sickle cell disease. Each green dot

represents an individual study. The symmetrical distribution of

studies around the central line suggests low likelihood of

publication bias. The vertical dashed line indicates the overall

pooled effect estimate, while the triangle represents the 95%

confidence boundaries. The white and darker grey triangles indicate

different confidence regions. The white triangle represents the 95%

confidence region, showing where study results are expected to lie

if there is no publication bias and only random variation around

the true effect. The darker grey regions represent wider confidence

limits, such as 99% or 90% intervals, providing additional context

for how study results should be distributed with varying levels of

precision. Notably, Knight-Madden et al (16) appears as an outlier, contributing

to observed heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis by study design

(prospective vs. retrospective). Forest plot comparing the risk of

ACS in patients with sickle cell disease and asthma vs. those

without asthma, stratified by study design. The pooled RR in

prospective studies was 1.85 (95% CI: 1.58-2.17) with no

heterogeneity (I2=0%), while retrospective studies

showed a higher pooled RR of 2.56 (95% CI: 1.72-3.82) and

substantial heterogeneity (I2=85.5%). The prediction

interval (0.93 to 5.38) suggests variability in future study

outcomes. The red line indicates the overall pooled effect. These

results support the robustness of the asthma-ACS association, while

highlighting study design as a contributor to heterogeneity. MH,

Mantel-Haenszel; df, degrees of freedom; RR, risk ratio; ACS, acute

chest syndrome.

Sensitivity analysis excluding

high-heterogeneity studies. Forest plot showing the association

between asthma and ACS in patients with sickle cell disease

following the exclusion of the studies by Knight-Madden et

al (16) and Intzes et

al (21), which were

identified as major contributors to heterogeneity. The remaining 10

studies (401 experimental vs. 1,669 control participants) yielded a

pooled risk ratio of 1.88 (95% CI: 1.59-2.24; P<0.05),

indicating a significant association between asthma and increased

ACS risk. Heterogeneity was reduced to moderate levels

(I2=52%), suggesting improved consistency across

studies. The prediction interval (1.17 to 3.02) reinforces the

robustness of the association. MH, Mantel-Haenszel; df, degrees of

freedom; ACS, acute chest syndrome.

Search strategy applied in

PubMed.

NOS quality assessment form regarding

included studies.

NOS quality assessment form regarding

included studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

KD and VEG conceptualized the study. KD, VEG, TVK,

AC and DAS made a substantial contribution to data interpretation

and analysis and wrote and prepared the draft of the manuscript. KD

and VEG analyzed the data and provided critical revisions. KD, TVK,

DAS, AC and VEG confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors contributed to manuscript revision, and read and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DAS is the Editor-in-Chief for the journal, but had

no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence

in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article.

The other authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, the AI tool

ChatGPT was used to improve the readability and language of the

manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised and edited the

content produced by the AI tool as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Rees DC, Williams TN and Gladwin MT:

Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 376:2018–2031. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kochhar M and McGann PT: Sickle cell

disease in India: Not just a mild condition. Br J Haematol.

206:380–381. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease

Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence and

mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000-2021: A systematic

analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet

Haematol. 10:e585–e599. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sundd P, Gladwin MT and Novelli EM:

Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. Annu Rev Pathol.

14:263–292. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tentolouris A, Stafylidis C, Siafarikas C,

Dimopoulou MN, Makrodimitri S, Bousi S, Papalexis P, Damaskos C,

Trakas N, Sklapani P, et al: Favorable outcomes of patients with

sickle cell disease hospitalized due to COVID-19: A report of three

cases. Exp Ther Med. 23(338)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

DeBaun MR and Strunk RC: The intersection

between asthma and acute chest syndrome in children with

sickle-cell anaemia. Lancet. 387:2545–2553. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Lunt A, Sturrock SS and Greenough A:

Asthma and the outcome of sickle cell disease. Expert Opin Orphan

Drugs. 6:733–740. 2018.

|

|

8

|

De A, Williams S, Yao Y, Jin Z, Brittenham

GM, Kattan M, Lovinsky-Desir S and Lee MT: Acute chest syndrome,

airway inflammation and lung function in sickle cell disease. PLoS

One. 18(e0283349)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Samarasinghe AE and Rosch JW: Convergence

of inflammatory pathways in allergic asthma and sickle cell

disease. Front Immunol. 10(3058)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I,

Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA and Thacker

SB: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A

proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in

epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 283:2008–2012. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, O'Connell

D, Peterson J, Welch Losos M, Tugwell P, Ga SW, Zello G and

Petersen J: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the

quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. American Academy

of General Practice, Kansas City, MO, 2000.

|

|

13

|

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT and Altman DG:

Analyzing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Chapter 9: In:

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Higgins

JPT and Green S (eds). The Cochrane Collaboration, London,

2011.

|

|

14

|

Meta-Mar. Meta Mar: A tool for

meta-analysis. Available from https://www.meta-mar.com/.

|

|

15

|

Boyd JH, Moinuddin A, Strunk RC and DeBaun

MR: Asthma and acute chest in sickle-cell disease. Pediatr

Pulmonol. 38:229–232. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Knight-Madden JM, Forrester TS, Lewis NA

and Greenough A: Asthma in children with sickle cell disease and

its association with acute chest syndrome. Thorax. 60:206–210.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Boyd JH, Macklin EA, Strunk RC and DeBaun

MR: Asthma is associated with acute chest syndrome and pain in

children with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 108:2923–2927.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sylvester KP, Patey RA, Broughton S,

Rafferty GF, Rees D, Thein SL and Greenough A: Temporal

relationship of asthma to acute chest syndrome in sickle cell

disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 42:103–106. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

An P, Barron-Casella EA, Strunk RC,

Hamilton RG, Casella JF and DeBaun MR: Elevation of IgE in children

with sickle cell disease is associated with doctor diagnosis of

asthma and increased morbidity. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

127:1440–1446. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Glassberg JA, Chow A, Wisnivesky J,

Hoffman R, Debaun MR and Richardson LD: Wheezing and asthma are

independent risk factors for increased sickle cell disease

morbidity. Br J Haematol. 159:472–479. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Intzes S, Kalpatthi RV, Short R and Imran

H: Pulmonary function abnormalities and asthma are prevalent in

children with sickle cell disease and are associated with acute

chest syndrome. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 30:726–732. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Strunk RC, Cohen RT, Cooper BP, Rodeghier

M, Kirkham FJ, Warner JO, Stocks J, Kirkby J, Roberts I, Rosen CL,

et al: Wheezing symptoms and parental asthma are associated with a

physician diagnosis of asthma in children with sickle cell anemia.

J Pediatr. 164:821–826.e1. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bafunyembaka G, Nacher M, Maniassom C,

Birindwa AM and Elenga N: Asthma is an independent risk factor for

acute chest syndrome in children with sickle cell disease in French

Guiana. Children (Basel). 11(1541)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Bartram JL, Fine-Goulden MR, Green D,

Ahmad R and Inusa BP: Asthma in pediatric sickle cell acute chest

syndrome: In an inner City London hospital. Blood.

112(2481)2008.

|

|

25

|

Bernaudin F, Strunk RC, Kamdem A, Arnaud

C, An P, Torres M, Delacourt C and DeBaun MR: Asthma is associated

with acute chest syndrome, but not with an increased rate of

hospitalization for pain among children in France with sickle cell

anemia: A retrospective cohort study. Haematologica. 93:1917–1918.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Pahl K and Mullen CA: Original research:

Acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease: Effect of genotype and

asthma. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 241:745–758. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Willen SM, Rodeghier M and DeBaun MR:

Asthma in children with sickle cell disease. Curr Opin Pediatr.

31:349–356. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Habib N, Pasha MA and Tang DD: Current

understanding of asthma pathogenesis and biomarkers. Cells.

11(2764)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gomez E and Morris CR: Asthma management

in sickle cell disease. Biomed Res Int. 2013(604140)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Miller AC and Gladwin MT: Pulmonary

complications of sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

185:1154–1165. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|