Introduction

The gastrointestinal epithelium serves as a barrier

between the external environment and the internal milieu of the

body. This barrier is crucial for preventing the translocation of

bacteria and toxins into systemic circulation (1). Intestinal permeability occurs via two

main pathways: Paracellular and transcellular. The transcellular

pathway involves the passage of molecules through the epithelial

cells, via processes such as endocytosis, vesicular transport, and

exocytosis, and is regulated by membrane transporters and channels.

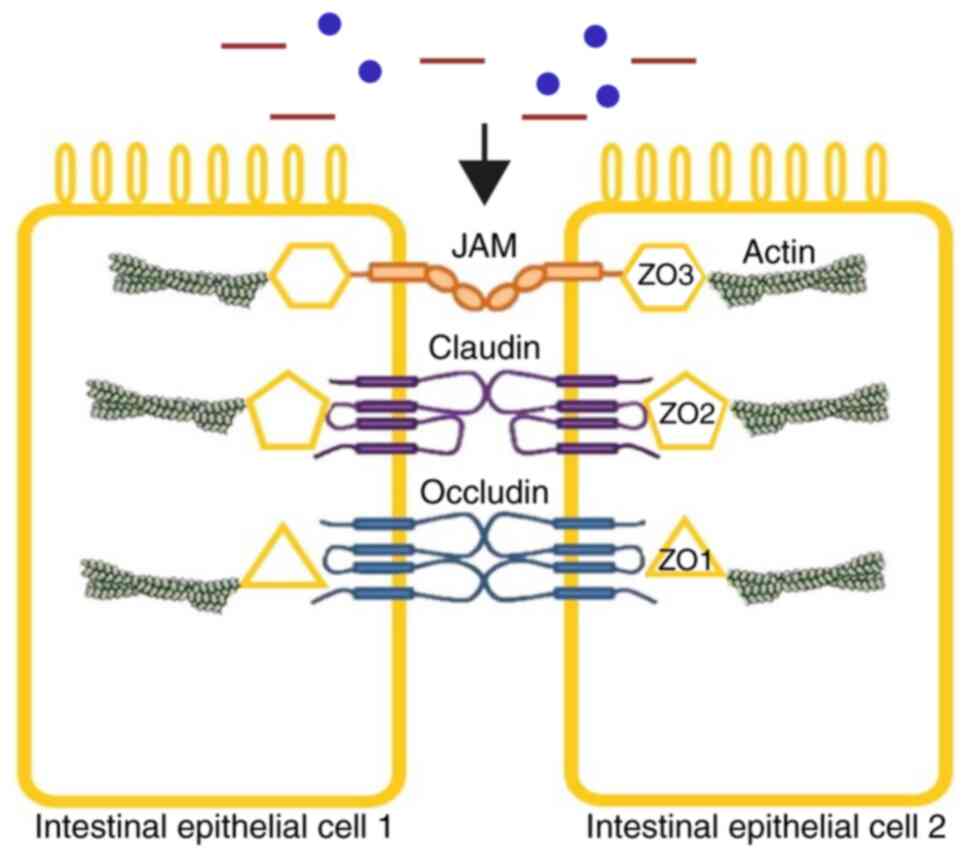

Paracellular permeability is governed by tight junction (TJ)

proteins; TJs consist of several complex membrane proteins,

including claudins, occludin and zonula occludens (ZO) (Fig. 1). Epithelial TJs can be dynamically

modulated by various signals, including humoral and neural factors

that engage multiple cellular pathways, and alterations in the

expression of these proteins are implicated in various diseases

such as inflammatory bowel and celiac disease, and irritable bowel

syndrome (2,3).

Intestinal barrier function is influenced by

numerous factors such as diet, stress, microbiota and drugs.

Increased intestinal permeability has been associated with

gastrointestinal disorders, including celiac disease, inflammatory

bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome and food allergies, as well

as systemic conditions such as schizophrenia, multiple sclerosis,

diabetes mellitus and sepsis (4).

The mucosal barrier is essential for human health, and several

strategies have been developed to strengthen this barrier. One such

strategy is to maintain intestinal integrity through enteral

nutrition, which refers to the delivery of nutrients directly into

the gastrointestinal tract via oral intake or feeding tubes

(nasogastric or gastrostomy tubes). Additional approaches include

the use of probiotics and prebiotics to enhance TJ stability and

support beneficial microbiota composition, as well as dietary

fibers and short-chain fatty acids (5). Enteral nutrition preserves mucosal

structure by providing luminal nutrients that stimulate epithelial

cell turnover, enhance TJ protein expression, and support local

immune function. This strategy is commonly implemented in clinical

and perioperative settings to prevent intestinal atrophy and

maintain barrier integrity. Developing strategies such as this is

important as compromised intestinal integrity can lead to

endotoxemia and a proinflammatory state (6).

Bile and pancreatic secretions are important for

digestion, particularly for fatty acid absorption, and contribute

to cholesterol homeostasis. Furthermore, bile contributes to

intestinal barrier function by modulating glucose and lipid

metabolism, and may influence enterocyte proliferation and

apoptosis (7). The present study

aimed to evaluate the impact of the presence of luminal nutrients

(food) and biliopancreatic secretions on intestinal integrity to

guide clinical strategies in settings where maintaining intestinal

barrier function is critical.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 30 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (8-10

weeks; weight, 240-380 g) were housed under controlled conditions

(22˚C; 50-60% humidity; 12-h light/dark cycle) and fed a standard

diet (DSA Agrifood Products Inc.) with free access to both food and

water for 10 days prior to surgery.

Animal groups and surgical design

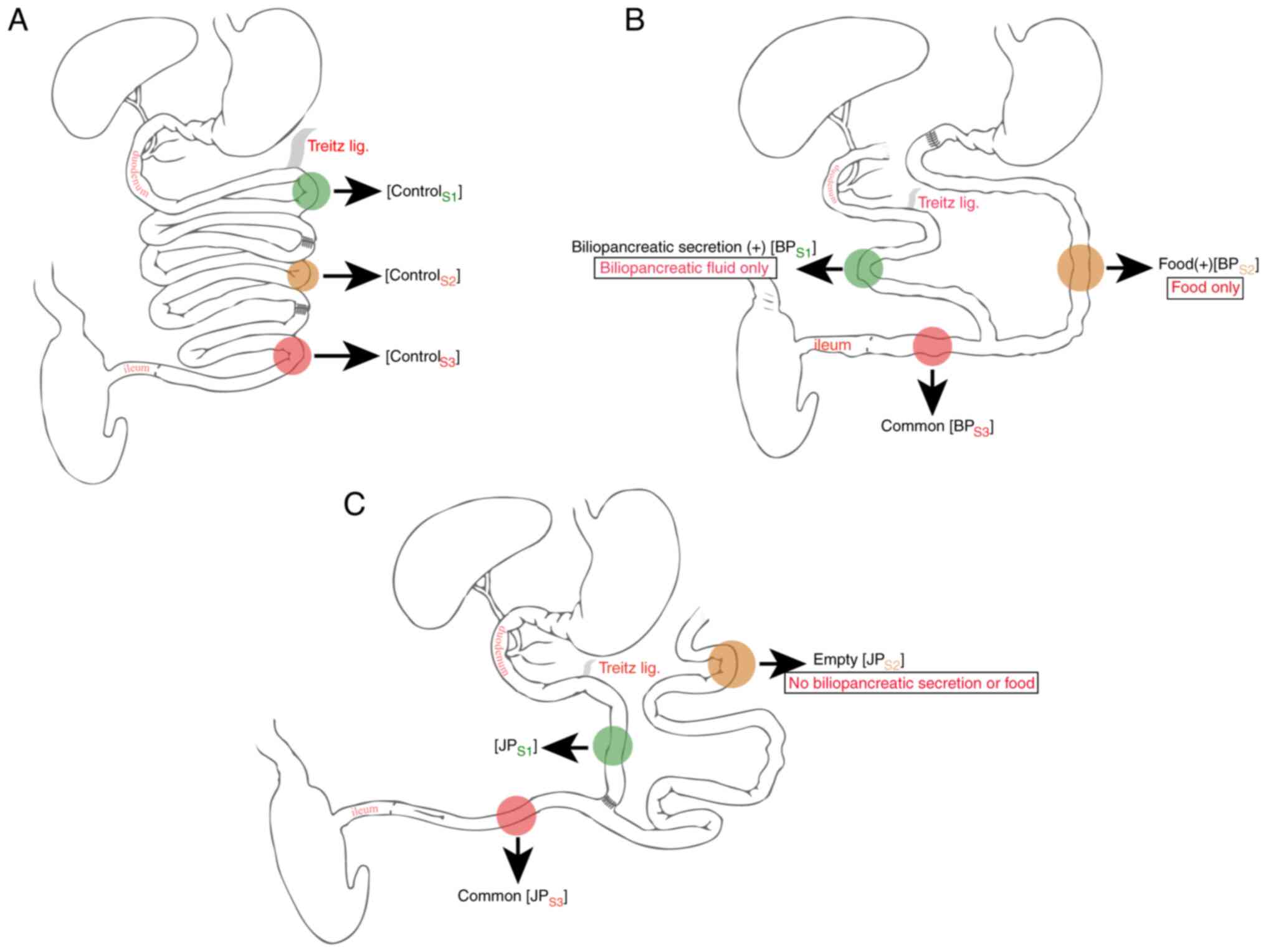

Rats were randomly divided into three groups (n=10

each): i) Group 1 (control), laparotomy + two jejunal enterotomies

and re-anastomoses; ii) group 2, biliopancreatic diversion (BP)

with separated food and biliopancreatic secretion segments; and

iii) group 3, jejunal bypass (JP) with food and biliary-deficient

isolated jejunal segments.

Anaesthesia was induced with ketamine (40 mg/kg) and

xylazine (10 mg/kg), and the skin was prepped with 10%

povidone-iodine. Sterile conditions were maintained throughout.

Prophylactic cefazolin (60 mg/kg) and subcutaneous morphine (1

mg/kg) were administered. All laparotomies were midline.

In group 1 (control), the jejunum was transected 30

and 90 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz, then re-anastomosed

using 6-0 polydioxanone sutures (Fig.

2A). The abdomen was irrigated with saline and closed using

standard techniques. In group 2 (BP), the duodenum was transected

and closed; the jejunum was divided 20 cm from Treitz. The distal

jejunum was anastomosed to the duodenum and the proximal segment

was reconnected 40 cm downstream (Figs. 2B-3A). Anastomotic integrity was tested

before closure (Video S1). In

group 3 (JP), the jejunum was transected 30 cm from Treitz, and the

proximal and distal ends were reconnected 40 cm apart (Fig. 2C). The bypassed segment was closed

and fixed to the abdominal wall.

Once surgery was complete, the surgical sites were

disinfected with chloramphenicol and iodine. Postoperatively, rats

recovered for 30 min before being returned to individual cages. On

day 1, a standard diet and water (with 100 mg/kg acetaminophen) was

resumed. Body weights were recorded every 3 days. On day 24,

animals were re-anesthetized using ketamine (40 mg/kg) and xylazine

(10 mg/kg). Euthanasia was performed via exsanguination through

portal vein puncture under deep anaesthesia. Cessation of heartbeat

and respiration were used to confirm the death of all animals.

Sample collection

Blood samples were collected from the portal vein at

the time of sacrifice. Intestinal tissue samples were then

harvested immediately. Samples intended for microbiological

analysis were processed fresh, while tissues for

immunohistochemistry were fixed in formalin and embedded in

paraffin blocks prior to staining. Samples were collected for

histopathological and microbiological examination as follows:

Control group (n=10): ControlS1, 10 cm from the ligament

of Treitz; controlS2, 50 cm from the ligament of Treitz;

controlS3, 80 cm from the ligament of Treitz (Fig. 2A). Group 2, BP (n=9):

BPS1, 10 cm from the ligament of Treitz, biliopancreatic

secretion (+); BPS2, 30 cm from the gastrojejunostomy,

food (+); BPS3, 20 cm from the jejunojejunostomy,

representing the common limb through which both food and

biliopancreatic secretions pass (Fig.

2B). Group 3, JP (n=8): JPS1, 10 cm from the

ligament of Treitz; JPS2, 20 cm from the stump of the

blind loop, biliopancreatic secretion (-) and food (-);

JPS3, 10 cm from the jejuno-jejunostomy, common

intestinal limb (i.e., the segment where luminal contents and

biliopancreatic secretions mix) (Fig.

2C). Analyses of histopathological and immunohistochemical

findings were performed, comparing the intestinal segment samples

to other segments within the same group and also to those of the

control group (Fig. S1A).

Histopathology and

immunohistochemistry

For histopathological examination, tissue samples

were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for

24 h, embedded in paraffin blocks, and sectioned at 3 µm thickness.

Sections were stained with hematoxylin (4 min) and eosin (30 sec)

at room temperature. The stained slides were examined under a light

microscope (Olympus SL-50). Villus height/crypt depth ratios were

evaluated (2:1=atrophic, 5:1=normal) based on literature standards

(8). Intraepithelial lymphocytes

(IELs) counting was performed on H&E-stained sections. For each

sample, four randomly selected high-power fields (x400

magnification) were evaluated. The number of intraepithelial

lymphocytes was manually counted and expressed as the number of

IELs/100 epithelial cells (≤20=normal, >20=high). IELs were

identified as small, round intraepithelial cells with darkly

stained, round nuclei and minimal cytoplasm. Neutrophils were

excluded from IEL counts based on their characteristic multilobed

nuclei and lighter cytoplasmic staining. Tissue samples were also

stained for the TJ proteins occludin, claudin-1 and ZO-3. All

immunohistochemistry examinations were performed on

paraffin-embedded sections. Following deparaffinization, endogenous

peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min

for 5 min at room temperature. Non-specific binding was blocked

using 5% normal goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no.

G9023) for 30 min at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was

performed by boiling the sections in citrate buffer for claudin-1

or EDTA buffer for occludin and ZO-3 at 95˚C for 20 min. Sections

were incubated with primary rabbit monoclonal antibodies at ~95˚C

against claudin-1 (Abcam, cat. no. ab140349, 1:200), occludin

(Abcam, ab168986, 1:150), and ZO-3 (Abcam, ab191143, 1:200) for 20

min. Detection was performed using the Leica HRP-conjugated

detection kit (DS9800, New Castle, UK), followed by sequential

incubation with 3% hydrogen peroxide (10 min at room temperature)

and DAB (6 min at room temperature). Slides were counterstained

with hematoxylin for 1-2 min at room temperature. Skin, kidney, and

intestinal tissue were used as positive controls for claudin-1,

occludin, and ZO-3, respectively.

Results were scored for staining intensity of

occludin as weak (400x), moderate (100x), or strong (40x). Results

were scored for staining intensity of ZO-3 as weak (400x), moderate

(200x), or strong (40x). Results were scored for staining pattern

of claudin-1 as weak (≤1/3 of villi) or strong (>1/3 of villi)

(9) Staining intensity was

evaluated semi-quantitatively based on the brown DAB chromogenic

signal and the proportion of positively stained epithelial cells.

All histopathological and immunohistochemical samples were

initially evaluated by a pathologist. Subsequently, the samples

were blindly reviewed by another pathologist.

Microbiological and biochemical

analyses

After laparotomy and blood sampling, the intestinal

segments were excised and immediately placed into pre-weighed

sterile containers containing 0.9% normal saline. The containers

were weighed again to determine the tissue mass by difference. Each

tissue sample was then homogenized using a sterile tissue

homogenizer in saline at a 1:10 (w/v) ratio. Ten-fold serial

dilutions (10-¹-10-5) were prepared, and 100

µl from each dilution was plated on blood agar and Endo agar. The

plates were incubated aerobically at 37˚C for 24 h, after which

colony numbers were counted. Bacterial load was expressed as

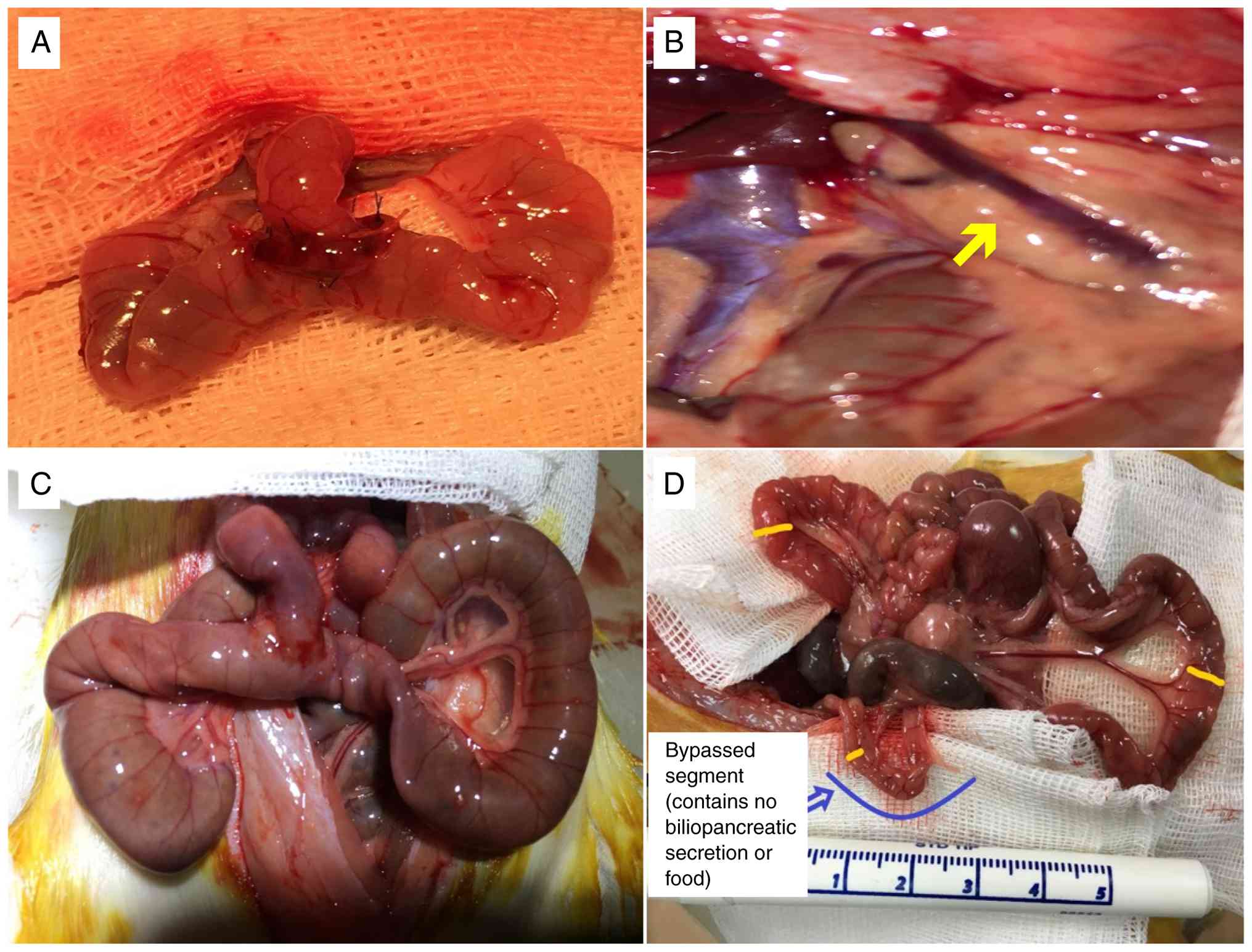

colony-forming units per gram of tissue (CFU/g). Portal blood was

sampled from the portal vein, as demonstrated in Fig. 3B, for the measurement of plasma

lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and citrulline levels. Plasma was isolated

from heparinized portal blood samples and stored at -80˚C until

analysis. Plasma concentrations of lipopolysaccharides were

measured using an ELISA kit (Elabscience, cat. no: E-EL-0025), and

plasma citrulline levels were measured using an ELISA kit

(MyBioSource; cat. no. MBS2600386), according to the manufacturers'

instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

Statistics version 23 (IBM Corp.). Proportions of histopathological

and immunohistochemical data (ordinal variables) were presented

using cross-tabulations. χ² or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate,

was used to compare the proportions in the different groups. The

results of descriptive analyses are presented as the mean and

standard deviation for weight and biochemical variables. The

Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare those parameters. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Macroscopic findings

Three animals (two from the JP group and one from

the BP group) died spontaneously prior to day 24. Necropsy revealed

major intra-abdominal complications consistent with leakage and

infection, as the cause of death. These deaths were excluded from

the final histopathological and biochemical analyses. Overall, no

other major intra-abdominal complications (such as abscess or fluid

accumulation) were observed in the animals used for analysis. Some

animals had mild adhesions between bowel loops, but no obstruction

or stenosis was detected. Gross intestinal atrophy was most evident

in segments deprived of both food and biliopancreatic secretions

(Fig. 3D).

Weight changes

All animals gained weight postoperatively, with no

significant differences between the groups (Fig. S1B). The mean weights prior to

euthanasia were 404±54 in the Control group, 361±65 g in the BP

group, and 397±50 g in the JP group.

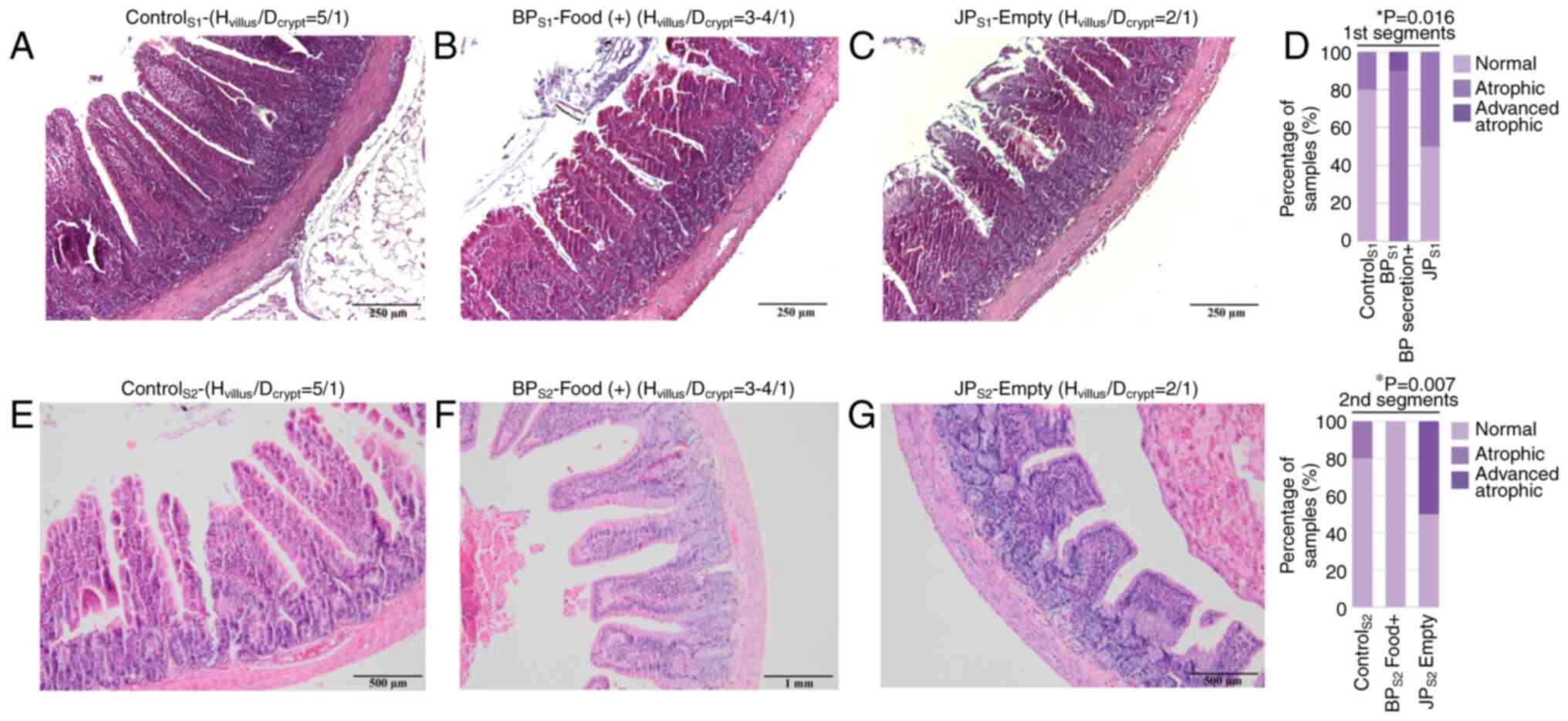

Villus/crypt ratio

Villus/crypt ratios were assessed to evaluate

mucosal integrity across intestinal segments, and representative

histological images are presented in Fig. 4A-C, E-F. When villus height/crypt

depth ratios of the first segments (S1) in all groups were

compared, a significant decrease in villus height/crypt depth ratio

was observed in the BPS1 segment, where only

biliopancreatic secretions were present. When the villus

height/crypt depth ratio of the second segments (S2) of all groups

were compared, the most severe atrophy occurred in JPS2

(no food or bile; Fig. 4D). No

significant differences were found in the third segments (common

limb; S3).

IEL count

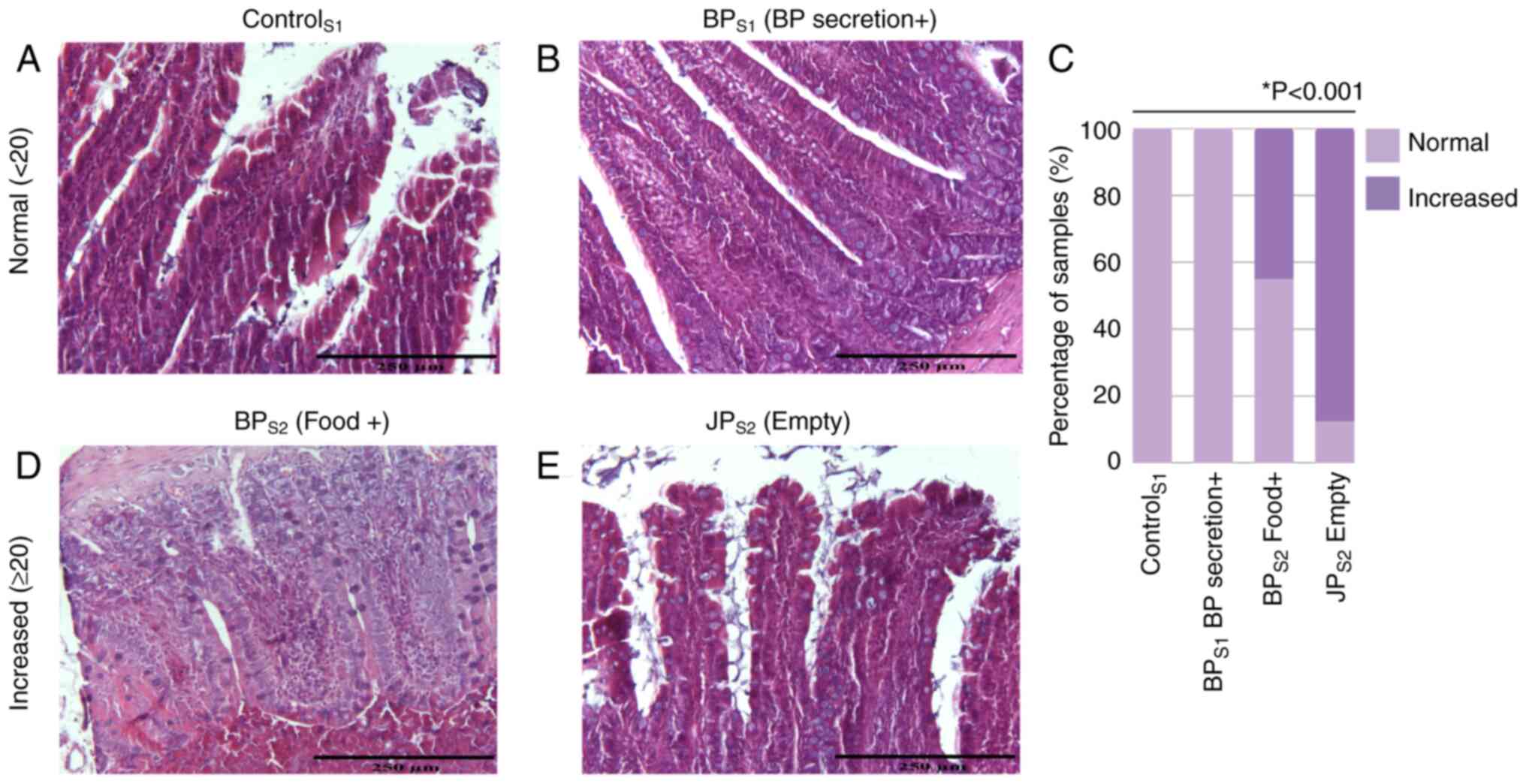

IEL counts were assessed based on the number of

intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells as described

(Fig. 5A, B, D-E). IEL counts were

compared across segments with differing exposure to luminal

contents: Control S1 (food + biliopancreatic secretions), BPS1

(biliopancreatic secretions only), BPS2 (food only), and JPS2

(neither food nor biliopancreatic secretions). IEL counts were

significantly higher in the segments lacking biliopancreatic

secretions (BPS2 and JPS2), with the highest counts observed in

JPS2 (Fig. 5C). No significant

differences were observed in the S3 (common limb) segments when

comparing the Control, BP, and JP groups, as this region receives

both luminal nutrients and biliopancreatic secretions in all

models.

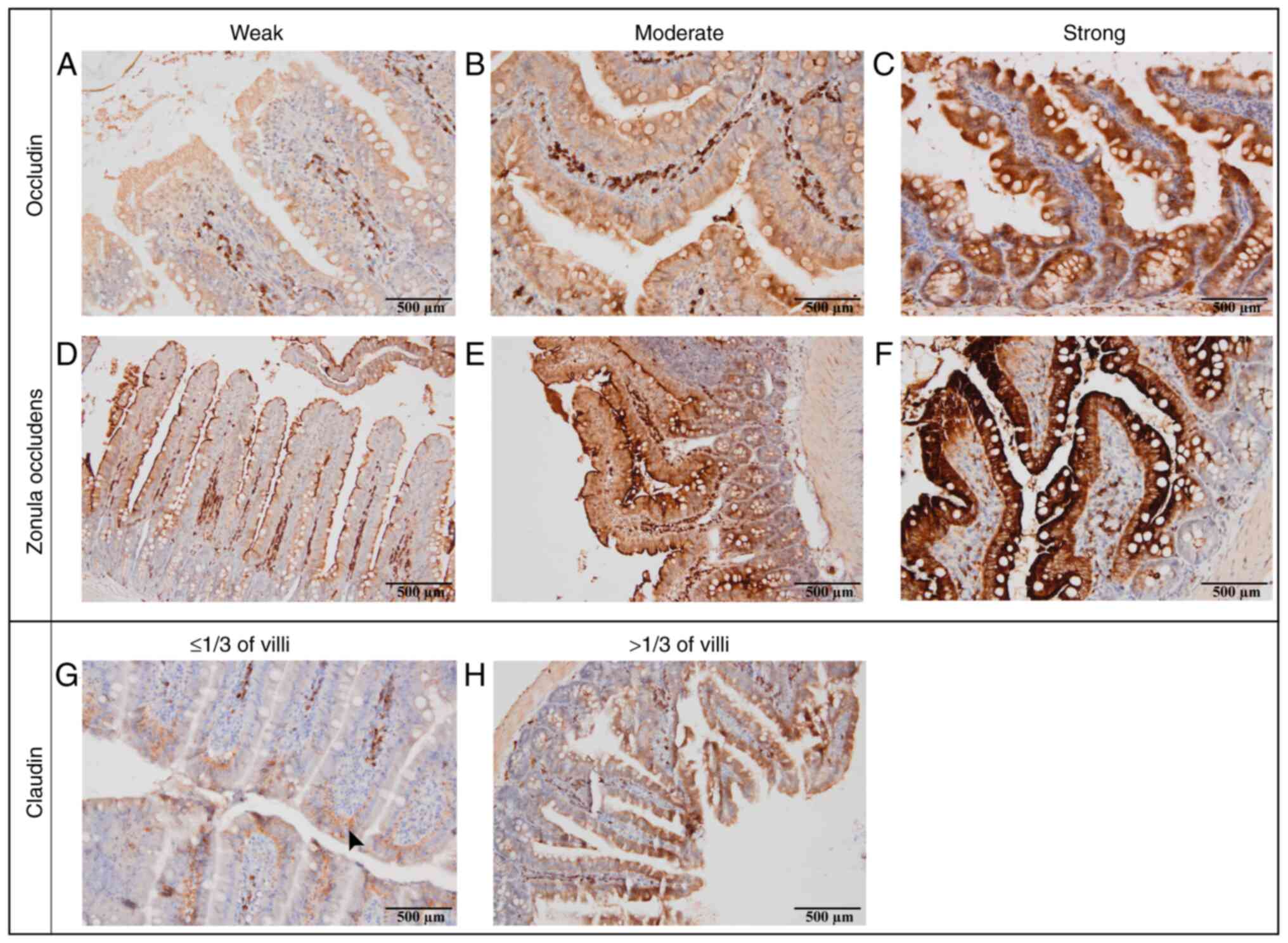

TJ protein expression

The staining intensity and distribution patterns of

occludin, ZO-3, and claudin-1 were evaluated according to the

semi-quantitative criteria shown in Fig. 6A-H (weak, moderate or strong

staining for occludin and ZO-3; and ≤1/3 vs. >1/3 villus height

for claudin-1). No statistically significant changes in ZO-3

expression were observed across any segment. The results

demonstrated slight variations in BPS1 and

BPS2, but this did not reach statistical

significance.

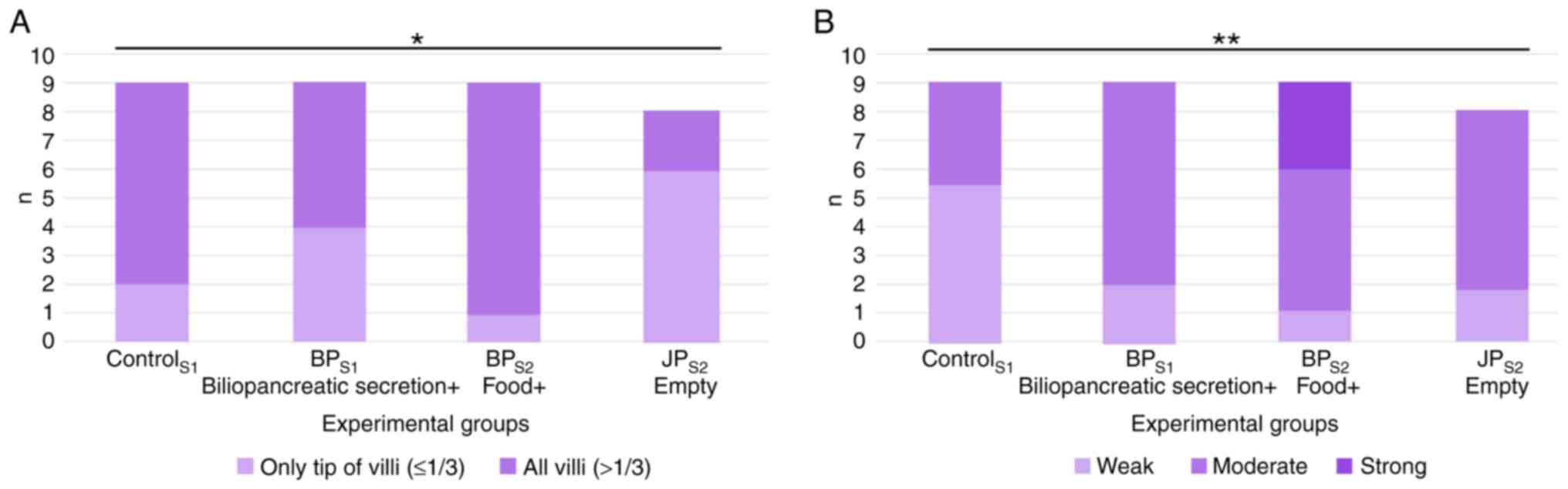

For claudin-1, when the first segments (S1) across

all groups were compared, no significant differences in claudin-1

staining patterns were observed. Expression levels of claudin-1

were significantly reduced in intestinal JPS2 segment

when compared with expression in the control group (Fig. 7A). No differences were noted in the

third segments (S3). In the S1 segment, occludin staining intensity

was significantly higher in the JP group compared with the Control

and BP groups. By contrast, no significant differences were

observed among the groups in the S2 and S3 segments. Compared with

the control segment (S1, where both food and biliopancreatic

secretions were present), occludin staining intensity was slightly

increased in the BPS1 segment (bile only) and the JPS2 segment

(neither food nor bile). The highest occludin expression was

observed in the BPS2 segment, where only food was present (Fig. 7B).

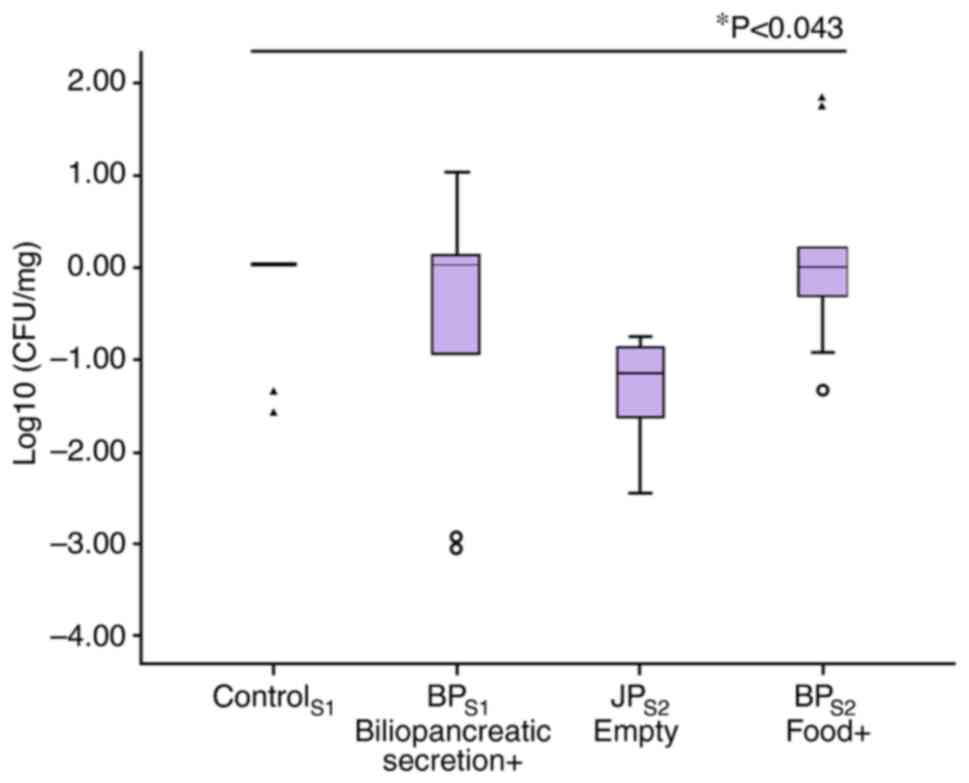

Jejunal aerobic bacteria

Compared with control group, bacteria population in

related segments on values of log10(CFU/mg) had no noticeable

change in segment where only bile passed, an increase in segment

where only food passed, a decrease in segment which included

neither food nor bile (Fig. 8).

The difference among them was recorded statistically

significant.

Plasma LPS and citrulline

Plasma LPS and citrulline levels represent one

measurement per animal obtained from portal blood and are reported

as group mean values. Plasma LPS levels did not differ

significantly between groups. Plasma citrulline levels were highest

in controls (8±2.0 nmol/ml) and lowest in JP group segments (6±1.7

nmol/ml), but this difference was not significant (Fig. S1C).

Discussion

The largest microorganism reserve in the human body

is found in the gastrointestinal tract (10). The physical, chemical and immune

barrier functions of the gastrointestinal system prevent bacteria

from spreading and invading the systemic circulation (11). TJ proteins between intestinal cells

serve a major role in the regulation of intestinal permeability;

notably, altered intestine permeability is associated with

endotoxemia and may be involved in the pathogenesis of a number of

diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease,

type 2 diabetes, obesity, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

(12). The effects of enteral

nutrition on intestinal integrity have been widely studied; the

literature consistently highlights enteral nutrition in maintaining

intestinal structure and function due to its physiological

engagement of the gut (13,14).

However, to the best of our knowledge, there are limited studies on

the individual effects of bile and pancreatic secretion or

food.

In the present study an experimental rat model was

used, jejunum segments were surgically created through which

biliopancreatic secretions, food or both did not pass. The

intestinal segments were long enough to prevent malnutrition as a

confounding factor. Consequently, there were no significant changes

in body weight among the groups throughout the experimental

period.

The present study showed that occludin expression,

which has a key regulatory role among TJ proteins, was

significantly affected depending on the presence of food within the

lumen. Specifically, the staining intensity of occludin was

increased in the segment where only food passed (BPS2), indicating

that direct luminal nutrient exposure was associated with enhanced

occludin expression. The present finding is supported by another

experimental study, which showed that occludin increases with

enteral nutrition compared with parenteral nutrition (15). Oral nutrients are key in building

up the gastrointestinal system from the beginning of life (16). The segment receiving only luminal

nutrients (BPS2) demonstrated the strongest occludin staining,

supporting the concept that direct exposure to dietary content

helps preserve TJ integrity throughout the lifespan. A decrease in

the expression of TJ proteins is associated with necrotizing

enterocolitis in the neonatal period, highlighting the importance

of proper nutrition in the intestines (17).

Claudin-1 is a TJ protein found in numerous tissues

besides the intestine, including the epidermal TJs in skin, the

bile canalicular membrane in the liver, and the distal renal

tubules in the kidney. These distributions highlight its broader

role in maintaining epithelial barrier function across organ

systems (18,19). Its expression has been shown to be

decreased in enterocytes in a number of conditions including

allergies, pancreatitis, cholangitis, colon cancer and inflammatory

bowel disease (20). In the

present study, claudin-1 expression was decreased in the absence of

food, and the decrease was more pronounced in the absence of both

biliopancreatic secretions and food. However, no change was

observed in the absence of biliopancreatic secretions alone.

Identifying the components of food that are most important for

improving the condition of TJ proteins will require further studies

(21).

In the present study, the expression of ZO-3 was

examined; ZO-3 is a member of the ZO protein family, which

functions as a cytoplasmic scaffold linking transmembrane TJ

proteins to the actin cytoskeleton (22,23).

No statistically significant differences in ZO-3 expression among

the experimental groups were observed, suggesting that this

structural protein may remain relatively stable in response to

luminal changes such as the absence of food or biliopancreatic

secretions. Similarly, in a high-fat diet mouse model by Murakami

et al (15) ZO-1 expression

remained unchanged, and no alterations were reported in the small

intestine, supporting the idea that ZO proteins are more resistant

to such changes. Collectively, these findings support the notion

that members of the ZO protein family, particularly ZO-1 and ZO-3,

may exhibit greater resistance to environmental or dietary

perturbations compared with transmembrane TJ components.

The intestinal mucosa can adapt in response to

different stimuli; this adaptation is key for survival in different

conditions including short bowel syndrome and after bariatric

surgery (24). In the present

study, it was observed that after the surgical procedures, the

animals in the experimental groups lost weight for 4-5 days and

regained weight after this period. Therefore, preserving the weight

of the animals and avoiding malnutrition are strengths of the

present study. In the study by Taqi et al (25), weight loss and reduced mucosal

growth were observed, particularly in segments deprived of luminal

nutrients. In contrast, in our study, animal body weights were

preserved throughout the experimental period, preventing

malnutrition and reducing its potential confounding effects. In

addition, citrulline levels, which were used as an indicator of

functional enterocyte mass, did not differ between the groups. This

suggests that functional enterocyte mass was preserved across the

groups, helping to prevent malnutrition and its systemic effects.

Although segment-specific structural and TJ protein differences

were detected, the overall functional integrity of the intestine

was maintained across groups. The intestinal segments through which

food passed demonstrated gross enlargement (increased segment

diameter and wall thickness). This macroscopic change may represent

an adaptive response, helping to compensate for the bypassed

segments that receive reduced luminal stimulation.

Mucosal integrity and growth are mediated by

hormonal, neural, immune and mechanical signals (26). A reduction in mucosal integrity and

barrier function is recognized as an early step preceding villous

atrophy, as the breakdown of TJs increases permeability and

compromises epithelial turnover. Mucosal atrophy is characterized

by morphological changes of villus height, crypt depth, surface

area and the number of epithelial cells (27). In the present study, it was shown

that there was notable atrophy in the segments through which

biliopancreatic secretions and food did not pass. The atrophy was

less notable if either food or biliopancreatic secretions were

present. The findings of the present study showed that food may

induce enhanced adaptation compared with biliopancreatic secretions

in terms of morphological features.

The interaction between the intestinal microflora

and the host has been a subject of research in numerous studies

(28,29). The current study presented that

intestinal bacterial content significantly decreased in the

segments through which food and biliopancreatic secretions did not

pass. On the other hand, there was an increasing trend in the

bacterial populations of the intestinal segments that had food but

not biliopancreatic secretions [BPS2-food(+)] compared within the

four-segment (Control S1, BP S1, BP S2, and JP S2). The effects of

food and different diets on intestinal microbiota have been

intensively explored in other studies and it has been shown that

diet is one of the major factors affecting the microbiota (30,31).

The present study has some limitations: i) The

effects of food and biliopancreatic secretions on intestinal

morphology were examined; however, the individual effects of bile

and pancreatic secretions were not determined; and ii) the focus

was only on the aerobic population and other bacterial subgroups

were not studied. Therefore future research should explore these

areas further.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

biliopancreatic secretions and food regulate intestinal morphology,

IEL count and the levels of TJ proteins, including occludin and

claudin-1. Similarly, the intestinal microbiota was shown to be

affected by food and gastrointestinal secretions. The present

findings indicated that food has a more prominent role than

gastrointestinal secretions in maintaining the morphology and

integrity of the gastrointestinal tract.

Supplementary Material

Representative immunohistochemical

images from all experimental groups and all intestinal segments

(S1-S3) stained for occludin, ZO-1 and claudin-1 (27 images total).

These images demonstrate staining intensity and localization

patterns along the villi, including segments that were not shown in

the main figures. (B) Weight change of animals during the study

period. Body weights were recorded every three days for all groups.

No significant weight loss was observed in the intervention groups

compared with the control group throughout the study duration. (C)

Plasma citrulline and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels.

Completion of gastrojejunostomy and

jejunojejunostomy anastomoses by hand-sewn technique in a rat

model. The video demonstrates the final stages of both anastomoses

and includes intraoperative assessment of anastomotic patency and

integrity.

Supplementary Video

Acknowledgements

This study was presented as an oral presentation at

the 41st ESPEN Congress, Krakow, Poland.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Hacettepe

University Scientific Research Unit (grant no: THD-2016-9077;

project number: 9077).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

OC performed the investigation, analyzed data and

wrote the original draft of the manuscript. AH performed

experiments, data interpretation and formal analysis, and assisted

in manuscript drafting and revision. BŞ and FA performed

experiments. CS analyzed and interpreted data. OA conceived and

designed the study, supervised the research process, interpreted

data, and critically revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. OC and AH confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Animal Ethics

Committee of Hacettepe University (approval no. 15/54-03; Ankara,

Turkey).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ghosh SS, Wang J, Yannie PJ and Ghosh S:

Intestinal barrier dysfunction, LPS translocation, and disease

development. J Endocr Soc. 4(bvz039)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Macura B, Kiecka A and Szczepanik M:

Intestinal permeability disturbances: Causes, diseases and therapy.

Clin Exp Med. 24(232)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Fung KY, Fairn GD and Lee WL:

Transcellular vesicular transport in epithelial and endothelial

cells: Challenges and opportunities. Traffic. 19:5–18.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Neurath MF, Artis D and Becker C: The

intestinal barrier: A pivotal role in health, inflammation, and

cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 10:573–592. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Rose EC, Odle J, Blikslager AT and Ziegler

AL: Probiotics, prebiotics and epithelial tight junctions: A

promising approach to modulate intestinal barrier function. Int J

Mol Sci. 22(6729)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Xu F, Lu G and Wang J: Enhancing sepsis

therapy: The evolving role of enteral nutrition. Front Nutr.

11(1421632)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Fleishman JS and Kumar S: Bile acid

metabolism and signaling in health and disease: Molecular

mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

9(97)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Serra S and Jani PA: An approach to

duodenal biopsies. J Clin Pathol. 59:1133–1150. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Resnick MB, Konkin T, Routhier J, Sabo E

and Pricolo VE: Claudin-1 is a strong prognostic indicator in stage

II colonic cancer: A tissue microarray study. Mod Pathol.

18:511–518. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sender R, Fuchs S and Milo R: Revised

estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body.

PLoS Biol. 14(e1002533)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Yu LC, Wang JT, Wei SC and Ni YH:

Host-microbial interactions and regulation of intestinal epithelial

barrier function: From physiology to pathology. World J

Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 3:27–43. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Horowitz A, Chanez-Paredes SD, Haest X and

Turner JR: Paracellular permeability and tight junction regulation

in gut health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

20:417–432. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Villalona G, Price A, Blomenkamp K,

Manithody C, Saxena S, Ratchford T, Westrich M, Kakarla V,

Pochampally S, Phillips W, et al: No gut no gain! enteral bile acid

treatment preserves gut growth but not parenteral

nutrition-associated liver injury in a novel extensive short bowel

animal model. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 42:1238–1251.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Chen R, Yin W, Gao H, Zhang H and Huang Y:

The effects of early enteral nutrition on the nutritional statuses,

gastrointestinal functions, and inflammatory responses of

gastrointestinal tumor patients. Am J Transl Res. 13:6260–6269.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shen TY, Qin HL, Gao ZG, Fan XB, Hang XM

and Jiang YQ: Influences of enteral nutrition combined with

probiotics on gut microflora and barrier function of rats with

abdominal infection. World J Gastroenterol. 12:4352–4358.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Al-Sadi R, Khatib K, Guo S, Ye D, Youssef

M and Ma T: Occludin regulates macromolecule flux across the

intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol

Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 300:G1054–G1064. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Garg PM, Denton MX, Ravisankar S, Herco M,

Shenberger JS and Chen YH: Tight junction proteins and intestinal

health in preterm infants. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 18:409–418.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Yu AS: Claudins and the kidney. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 26:11–19. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Németh Z, Szász AM, Tátrai P, Németh J,

Gyorffy H, Somorácz A, Szíjártó A, Kupcsulik P, Kiss A and Schaff

Z: Claudin -1, -2, -3, -4, -7, -8, and -10 protein expression in

biliary tract cancers. J Histochem Cytochem. 57:113–121.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yuan B, Zhou S, Lu Y, Liu J, Jin X, Wan H

and Wang F: Changes in the expression and distribution of claudins,

increased epithelial apoptosis, and a mannan-binding

lectin-associated immune response lead to barrier dysfunction in

dextran sodium sulfate-induced rat colitis. Gut Liver. 9:734–740.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Bertrand J, Ghouzali I, Guerin C,

Bôle-Feysot C, Gouteux M, Déchelotte P, Ducrotté P and Coëffier M:

Glutamine restores tight junction protein claudin-1 expression in

colonic mucosa of patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable

bowel syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 40:1170–1176.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Fanning AS, Jameson BJ, Jesaitis LA and

Anderson JM: The tight junction protein ZO-1 establishes a link

between the transmembrane protein occludin and the actin

cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 273:29745–29753. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Alizadeh A, Akbari P, Garssen J,

Fink-Gremmels J and Braber S: Epithelial integrity, junctional

complexes, and biomarkers associated with intestinal functions.

Tissue Barriers. 10(1996830)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Feris F, McRae A, Kellogg TA, McKenzie T,

Ghanem O and Acosta A: Mucosal and hormonal adaptations after

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 19:37–49.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Taqi E, Wallace LE, de Heuvel E, Chelikani

PK, Zheng H, Berthoud HR, Holst JJ and Sigalet DL: The influence of

nutrients, biliary-pancreatic secretions, and systemic trophic

hormones on intestinal adaptation in a Roux-en-Y bypass model. J

Pediatr Surg. 45:987–995. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Jacobson A, Yang D, Vella M and Chiu IM:

The intestinal neuro-immune axis: Crosstalk between neurons, immune

cells, and microbes. Mucosal Immunol. 14:555–565. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Sugita K, Kaji T, Yano K, Matsukubo M,

Nagano A, Matsui M, Murakami M, Harumatsu T, Onishi S, Yamada K, et

al: The protective effects of hepatocyte growth factor on the

intestinal mucosal atrophy induced by total parenteral nutrition in

a rat model. Pediatr Surg Int. 37:1743–1753. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Afzaal M, Saeed F, Shah YA, Hussain M,

Rabail R, Socol CT, Hassoun A, Pateiro M, Lorenzo JM, Rusu AV and

Aadil RM: Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the

relationship. Front Microbiol. 13(999001)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Tremaroli V and Bäckhed F: Functional

interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism.

Nature. 489:242–249. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yu J, Wu Y, Zhu Z and Lu H: The impact of

dietary patterns on gut microbiota for the primary and secondary

prevention of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Nutr J.

24(17)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Singh RK, Chang HW, Yan D, Lee KM, Ucmak

D, Wong K, Abrouk M, Farahnik B, Nakamura M, Zhu TH, et al:

Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human

health. J Transl Med. 15(73)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|