Introduction

Nail discoloration is an abnormal change in nail

(toenail) color that can provide important clues to potential

systemic and skin diseases. The causes of nail discoloration are

mainly divided into internal factors and external factors,

including infection, systemic disease, trauma and drug influence.

White nail is the most common nail discoloration; white nail can be

divided into true white nail, white spot and false white nail

(1). It is caused by the change of

the structure of the nail substance itself, the pathological change

of the nail bed, and the superficial invasion and dissemination of

fungi. Blue nail beds can be caused by cyanosis, hereditary

acrotelangiectasia, antimalarial drugs, argyria and glomus tumors,

and the use of systemic drugs can also cause blue nails (2).

Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic commonly

used to treat acne and rosacea. Common side effects of minocycline

associated with pigment include the following: Minocycline may

affect the development of bones and teeth in children, causing

teeth to turn yellow or brown. There have been numerous reports of

patients taking minocycline for a period of time and their nails

changed from the normal light color to gray or blue (2).

Pigmentation caused by minocycline can be divided

into five types, among which the ‘blue nail’ phenomenon caused by

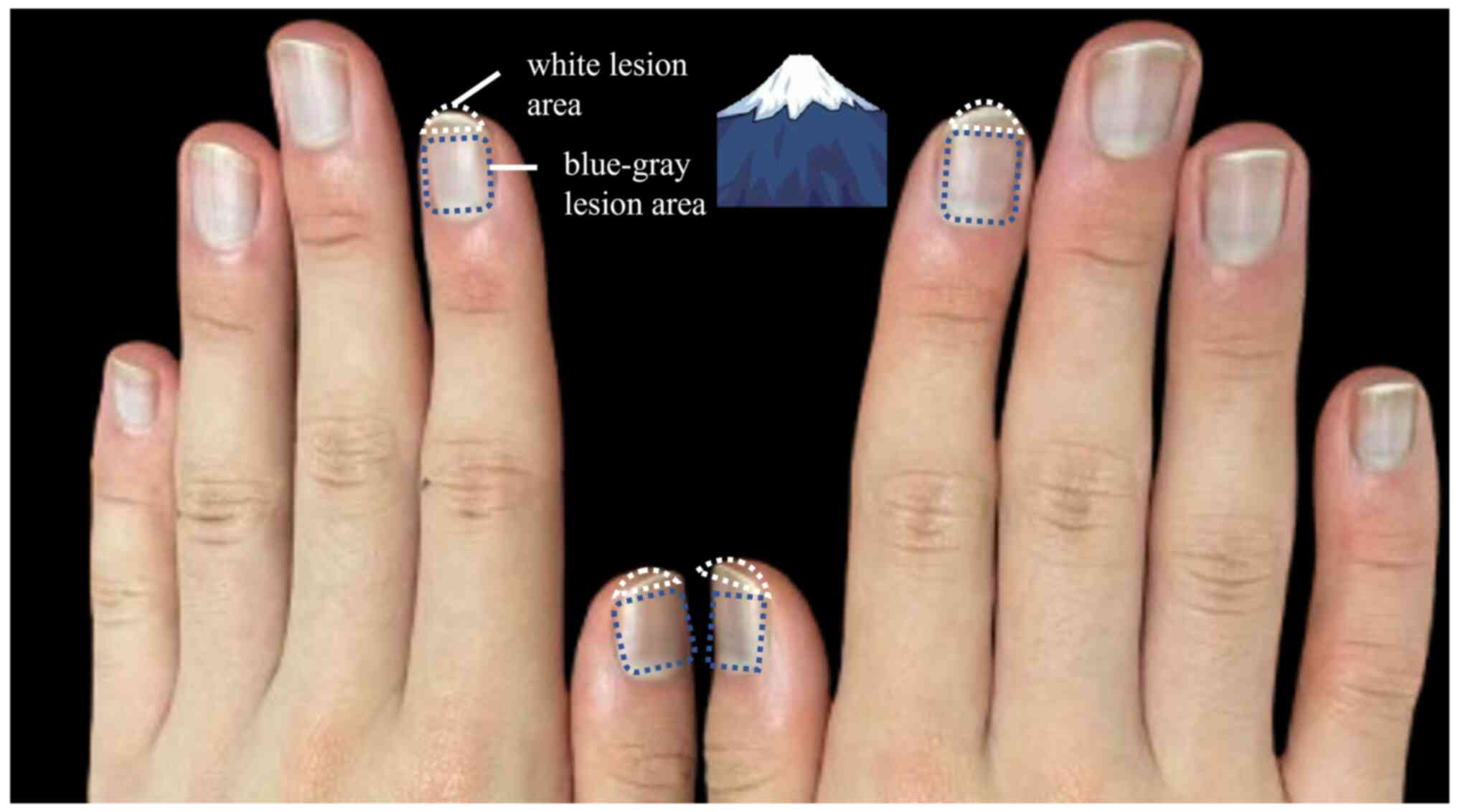

minocycline is considered to be type II pigmentation (3). However, in this case, the report of

minocycline-related tinea is significantly different from the

traditional type II pigmentation, which is manifested as a snowy

mountain of nail bed changes, i.e., the unique clinical

characteristics of blue gray pigmentation and bright white nail bed

changes, providing new phenotypic characteristics for

minocycline-related nail bed pigment changes and contributing to

further research on its pathogenesis and clinical diagnosis.

Case report

In July 2022, a 19-year-old male presented to the

Department of Dermatology with facial acne vulgaris, featuring

hyperplastic nasal scars, atrophic scars and persistent papular

lesions. The patient took minocycline, a medication prescribed by

the attending physician, twice a day at 50 mg each time, totaling

100 mg per day, and maintained this dosage for 1 month. During the

1-month treatment, the patient's nails developed a unique

appearance, ‘snow mountain nails’ (Fig. 1), with a blue-gray pigmentation

near the nail bed. There was also a distinct bright white nail

change at the free end, where parallel bright white stripes were

visible on the nail bed, complementing the blue-gray area to form a

unique bicolor change. It is worth noting that the patient did not

have abnormal pigmentation of the skin, teeth or toenails during

the course of the disease. When white nails appeared at the free

end of the nail, the treatment plan was adjusted. Minocycline was

discontinued, and the patient was instructed by the attending

physician to take isotretinoin soft capsules orally twice a day at

a dose of 10 mg to treat the acne. The abnormal nail appearance did

not improve until 2 months after the initial medication was

stopped. Biochemical tests and complete blood count analyses

conducted before and after minocycline treatment revealed an

abnormal elevation in plateletcrit at 2 weeks post-administration,

increasing from 0.256 to 0.303% (reference range: 0.108-0.303%).

All other results were within the normal ranges. Routine blood

tests were performed using the Sysmex XN-10 automatic hematology

analyzer (Sysmex Corporation). Biochemistry tests were conducted

with the Abbott Alinity C automatic biochemistry analyzer (Abbott).

Dry biochemistry tests were carried out using the Ortho Vitros 5600

automatic biochemistry and immunoassay analyzer (QuidelOrtho

Corporation). The patient was followed up every 2 weeks, where a

physical examination was conducted. Throughout the follow-up

period, the dosage of isotretinoin was adjusted based on the

patient's facial acne condition and nail status. At 2 months after

discontinuation of the medication, the color of the nail had

gradually improved: The blue-gray pigmentation range of the nail

bed was obviously reduced and the color changed from dark to light.

The free end of the bright white nail was gradually blurred, but

certain residual color changes were still observed. At 2 years

post-discontinuation of the medication, the patient's nail color

improved, with the bluish-gray and white tones gradually

disappearing, but the nails still did not regain their normal

appearance. The patient has been consistently taking isotretinoin

for acne treatment ever since. The periungual erythema and swelling

of the right hand may be associated with a chronic low-grade

inflammatory response triggered by the deposition of

minocycline-iron chelate complexes (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Blue-gray nail pigmentation is affected by a variety

of factors, such as infectious factors, including green nail

syndrome caused by bacterial infection, which can be identified by

direct fungal microscopy or positive culture, and lesions usually

start at the nail margin and gradually expand to the entire nail

(4). If Pseudomonas

aeruginosa is detected in nail culture, green nail syndrome

caused by bacterial infection can be diagnosed. Furthermore, nail

discoloration also requires a differential diagnosis with other

causes. For example, mechanical injury may lead to subungual

bleeding (appearing bluish-black), while prolonged exposure to

chemicals may directly cause nail discoloration (5).

Systemic diseases such as liver disease can cause

white nails. One study found that 82% of patients with ‘alcohol,

necrosis and cholangitis’ cirrhosis had a red or brown distal nail

bed that included <20% of the total nail length, kidney failure

leading to half nails, cardiovascular disease leading to pale

nails, and in addition, nail bed edema in lymphedema (1). Pale nail bed in severe anemia, scar

changes after whole-skin electron beam irradiation and selenium

deficiency can also cause obvious leukonychia (6). Drug reactions from long-term

medication use can turn nails yellow or black (7). The most common genetic factor is

autosomal dominant inheritance; for example, patients with

congenital leukonychia typically have milky white nails (1).

Minocycline, as a broad-spectrum antibiotic, is

commonly used to treat bacterial infections, particularly those

associated with acne and chlamydia. However, some side effects may

occur with the use of minocycline, among which pigmentation and

nail discoloration are the more common skin and appearance changes.

Long-term use of minocycline can cause pigmentation of nails, skin

and sclera without affecting function. Discontinuation is one of

the treatments for blue nails. In one study, it was found that nail

pigmentation can be resolved after discontinuation of oral

minocycline and the resolution time varies from 1 month to 3 years

(2). In the 2024 treatment

guidelines for common acne, it is stated that oral minocycline is a

commonly used medication for treating moderate to severe acne and

the patient in this case does not fall into the prohibited

population category (8). During

the 16-week treatment period for inflammatory skin lesions

associated with rosacea, the treatment success rate for the 40 mg

dose of minocycline was 66%, which was significantly higher than

the 11.5% in the placebo group, and it also demonstrated a

significant advantage in reducing the number of inflammatory

lesions (9). Compared to

tetracycline, minocycline has a stronger antibacterial effect

(10).

There are five types of pigmentation caused by

minocycline: Type I develops blue-black discoloration in previously

inflamed areas, such as acne secondary scarring; Type II skin has

blue-gray pigmentation in normal areas; Type III is a rare diffuse

mud-brown pigmentation, aggravated in sun-exposed areas; Type IV

appears with bluish-gray spots on the scarred area of the back; and

Type V is associated with hyperpigmentation and subcutaneous

involvement and is considered a progression of Types I and II to

subcutaneous infiltration. The ‘blue nail’ phenomenon caused by

minocycline is considered type II pigmentation. The incidence of

type II and III pigmentation increases with the cumulative dose of

minocycline (3). The

minocycline-associated nail pigmentation reported in the present

case showed significant differences from traditional type II

pigmentation. In addition to the blue-gray pigmentation of the nail

bed, the presentation was also uniquely accompanied by a bright

white change of the free end of the nail and the cross-distribution

of bright white stripes on the nail bed, and with the blue-gray

area near the nail root, it exhibited a sharp two-color contrast.

This unique nail manifestation not only enriches the scope of the

clinical phenotype of minocycline-associated pigmentation, but also

provides new ideas and research directions for further exploration

of its pathogenesis and diagnostic value.

The blue-gray pigmentation effect of minocycline is

mainly related to its metabolic process in vivo and its

interaction with tissues. It usually occurs in patients taking high

doses and using it for a longer period of time. Minocycline itself

can be deposited in the basal layer of the skin by chelating with

iron to form a stable complex, and minocycline can also affect

melanin production in the skin or interact directly with the

melanin synthesis mechanism, resulting in increased local

pigmentation. The chelation of minocycline with iron may accumulate

within the cuticle of the nail, and due to the high protein and

metal ions in the nail, the binding of minocycline with these

components may cause nail discoloration. In one study, it was

reported that patient who used minocycline for a long time may have

blue or gray pigmentation of their skin (11). The metabolism of minocycline in the

body may cause the drug to bind to metal ions in the skin, causing

this type of pigmentation change. A patient who had taken

minocycline for 4 years also experienced diffuse blue-gray

pigmentation on the face and ears (12). This pigmentation may occur not only

in the skin, but discoloration of the nails may also be observed,

another one of the more common side effects of minocycline. After

taking minocycline for several months, the patient developed a

significant discoloration of the nails, which changed from a normal

light color to gray or blue. Masuyama et al (13) found that after 10 weeks of

minocycline use, a patient's nail bed turned grayish-blue and its

thickness increased to 9 mm. This phenomenon is usually associated

with the accumulation of drugs. A 66-year-old male patient had

persistent blue-gray discoloration of the nails during the

treatment of rosacea with minocycline for 22 years (3). This blue nail was likely to be

misdiagnosed as a change in nail bed color related to heart

disease, and further cardiac-related tests were needed (3). It may take several months for the

nail color to recover after stopping the drug. Long-term use of

minocycline may lead to pigmentation when the cumulative dose

exceeds the threshold of 100 grams (3). This pigmentation is dose-dependent

and a daily dose of 100 mg for patients falls within the low-dose

range, which may also be one of the reasons for the regression of

‘snow mountain nail’. In addition to the blue-gray pigmentation

near the nail base of the nail bed, there is also a significant

bright white nail change at the free end. This comprehensive nail

change provides a new clinical feature for drug-induced nail

lesions, and its pathogenesis and diagnostic significance need to

be further studied. The formation of white stripes on the nail

plate may be due to the indirect effect of minocycline on the local

blood supply or inflammation of the nail bed during the

anti-inflammatory treatment of acne, which leads to a color change

of the nail plate (13). The

formation and deposition of iron-minocycline chelates may affect

the normal function of nail bed keratinocytes, including keratin

production and metabolism, making nails look pale. In addition, the

long-term use of minocycline may reactively interfere with local

melanin production and distribution, or it may be a rare

manifestation related to individual differences or local

environmental factors such as light exposure, inflammation and

metabolic status. In the present case, the clinical manifestations

improved markedly following discontinuation of minocycline,

supporting the hypothesis that the occurrence of ‘snow mountain

nails’ represents an adverse reaction associated with minocycline

therapy. However, the persistent bluish discoloration at the

proximal nail bed is likely attributable to the slow degradation of

minocycline-iron complexes deposited within the keratinized layer

and superficial dermis, resulting in residual blue-gray

pigmentation. Under these circumstances, the coexistence of

proximal bluish pigmentation and distal whitish striations did not

resolve after drug withdrawal or improved circulation, thereby

excluding hypoperfusion or systemic hypoxemia as potential

underlying mechanisms. This observation may further indicate the

persistence of local inflammatory activity, which could account for

the erythematous swelling observed over the dorsal aspect of the

interphalangeal joints.

In conclusion, side effects of minocycline, a common

antibiotic used to treat acne, include pigmentation of the nails

and other areas, but are generally reversible. To the best of our

knowledge, the present study reports the first case of a ‘snow

mountain nail’ characterized by blue-gray pigmentation near the

root of the nail accompanied by bright white changes at the free

end and parallel bright white stripes, which was different from the

blue pigmentation caused by minocycline reported in the past.

Although it was only a single case report, the clinical

manifestations of this case were relatively important, and this is

highly likely to be a new type of minocycline-based disease.

Therefore, the present case was reported for reference. This

clinical manifestation not only expands the phenotype spectrum of

minocycline-associated pigmentation, but also provides a new clue

for clinicians to monitor drug-related pigmentation during

minocycline use. It provides an important reference for further

study on the pathogenesis and diagnostic value of drug-related nail

lesions.

It was further confirmed that minocycline-induced

nail discoloration was improvable by withdrawal of minocycline and

detailed follow-up observation. The nail changes gradually returned

to normal after drug withdrawal, suggesting that this phenomenon

was an adverse reaction caused by minocycline. Case observations in

the literature suggest that such pigment alterations may involve

the chelation of minocycline and iron and their interference with

melanin production and metabolism, and are closely related to

inter-individual differences or local inflammatory states. The

report of this case not only provides important clues for the

diagnosis and differential diagnosis of minocycline-related

hyperpigmentation, but also highlights the importance of focusing

on hyperpigmentation of parts such as nails during minocycline

treatment. Future studies can further explore the pathogenesis,

diagnostic criteria and application value of ‘snow mountain nail’

in the monitoring of adverse drug reactions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82473556), Huadong Hospital Elite

Talent (grant no. JYRC2204) and the Clinical Research Plan of SHDC

(grant no. SHDC22025306).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

As the attending physician for this patient, LS was

the first to observe the ‘Snow Mountain Nail’ phenomenon. KL

performed a literature review and revised and supplemented the

manuscript. YTQ conducted the biopsy and initially analyzed the

medical record data. WJZ was responsible for the language editing

of the article. YTQ and WJZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. KL, WJZ, YTQ and LS were involved in the conception of the

study and the interpretation of the data, and have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of case information and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Iorizzo M, Starace M and Pasch MC:

Leukonychia: What can white nails tell us? Am J Clin Dermatol.

23:177–193. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hwang JK and Lipner SR: Blue nail

discoloration: Literature review and diagnostic algorithms. Am J

Clin Dermatol. 24:419–441. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Varghese K, Dykstra J and Bisbee E:

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation of nails. Cureus.

15(e38640)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Reynolds RV, Yeung H, Cheng CE,

Cook-Bolden F, Desai SR, Druby KM, Freeman EE, Keri JE, Stein Gold

LF, Tan JKL, et al: Guidelines of care for the management of acne

vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 90:1006.e1–1006.e30. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tsianakas A, Pieber T, Baldwin H,

Feichtner F, Alikunju S, Gautam A, Shenoy S, Singh P and Sidgiddi

S: Minocycline Extended-release comparison with doxycycline for the

treatment of rosacea: A randomized, Head-to-Head, clinical trial. J

Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 14:16–23. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Asadi A, Abdi M, Kouhsari E, Panahi P,

Sholeh M, Sadeghifard N, Amiriani T, Ahmadi A, Maleki A and Gholami

M: Minocycline, focus on mechanisms of resistance, antibacterial

activity, and clinical effectiveness: Back to the future. J Glob

Antimicrob Resist. 22:161–174. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Taniguchi Y and Yamamoto H: Clinical

images: Methotrexate-induced melanonychia. Arthritis Rheumatol: Jul

28, 2025 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

8

|

Forouzan P and Cohen PR: Fungal

viridionychia: Onychomycosis-induced chloronychia caused by Candida

parapsilosis-associated green nail discoloration. Cureus.

13(e20335)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Gregoriou S, Platsidaki E, Sidiropoulou P

and Rigopoulos D: Nails with bloodstained discoloration. BMJ.

375(n1951)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Hasunuma N, Umebayashi Y and Manabe M:

True leukonychia in Crohn disease induced by selenium deficiency.

JAMA Dermatol. 150:779–780. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ricardo JW, Shah K, Minkis K and Lipner

SR: Blue Skin, Nail, and Scleral Pigmentation Associated with

Minocycline. Case Rep Dermatol. 14:239–242. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wang P, Farmer JP and Rullo J:

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. JAMA Dermatol.

57(992)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Masuyama T, Branch J, Ishizuka K, Uchida

R, Otsuki T, Ie K and Okuse C: Minocycline-induced blue nails. Am J

Med. 137:e190–e191. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|