1. Introduction

Since their initial discovery in the mid-1940s,

aminoglycoside (AG) antimicrobials have been used extensively to

treat severe infections. The first AG was streptomycin, which was

initially created to treat tuberculosis (1); gentamicin (1963), tobramycin (1967)

and amikacin (1972) are three of the other AGs that have been

discovered and are still widely used in modern medicine (2-4).

Due to the ability of AGs to specifically bind to the 30S ribosomal

subunit, which effectively prevents bacterial intracellular protein

synthesis, they demonstrate potent bactericidal activity (5). Due to their narrow therapeutic index

(a small range between the minimum effective dose and the minimum

toxic dose) and potential for ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity, AGs

must only be prescribed under strict guidelines and in accordance

with meticulous therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) (6). Currently, patients with sepsis or

septic shock who are at high risk of multidrug-resistant (MDR)

Gram-negative bacilli infections are frequently treated empirically

with AGs in combination with another antimicrobial drug (mostly a

β-lactam) (6).

Antimicrobial resistance has emerged as a

significant global threat to healthcare. By 2050, it is predicted

that 10 million individuals per year could die from infections that

are antimicrobial resistant (AMR), according to the World Health

Organization (7). The different

resistance mechanisms produced by MDR bacteria against

new-generation and broad-spectrum antibiotics are quickly growing,

limiting the treatment options for infections (8). Particularly relevant to carbapenem

resistance mechanisms is the identification of five carbapenemase

genes (oxa-48, imp, ndm, vim and

kpc) in Gram-negative bacteria (GNB). These genes are all

carried by plasmids, which allows for a high rate of horizontal

transmission. Extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs)-producing

Enterobacterales and carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter

baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacterales

were among the bacterial pathogens that indicated a strong ability

to be AMR. These infections are becoming more difficult to treat

empirically after being microbiologically confirmed (9).

The ESKAPE healthcare-associated infections are

caused by a group of GNB and Gram-positive bacterial pathogens

including Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus

aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter

baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Enterobacter. These healthcare-associated infections are

extremely resistant to antibiotics, including AGs (10). The two main mechanisms of

Enterobacterales resistance to AGs are enzymatic drug modification

or target site modification (11,12).

The most common mechanism is enzymatic drug modification by

aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs): N-acetyltransferases

(AACs), o-adenyl transferases (nucleotidyltransferases) and

o-phosphotransferases (APHs), are three major classes of AMEs, each

with several variants, and certain AGs are impacted by each

specific enzyme but not others. Gram-negative bacilli, especially

Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli, usually

have the aac(60) gene

encoding the acetyltransferase enzyme. This modification reduces

the antibacterial activity of AGs by preventing it from attaching

to the bacterial ribosome. Notably, the microbe may create several

enzymes from the same or distinct classes, resulting in high-level

resistance (6).

ArmA and RmtB are the most expressed 16S rRNA

methyltransferases (16RMT) that modify (by methylation) the target

site of AGs (12). Nevertheless,

they are rarely encountered in clinical settings, with only 1.28,

0.14 and 0.05% isolates reported from Europe and parts of Asia

(13), the US (14) and Canada (15), respectively, that have been

recorded expressing ArmA and RmtB. Additionally, drug

impermeability with porin channel down-regulation or active drug

elimination by efflux pumps (AcrD) might lead to resistance

against AGs, especially with Acinetobacter baumannii and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, explaining the higher minimum

inhibitory concentrations (MICs) frequently exhibited by these

bacterial pathogens (16,17).

The use of traditional AGs has been limited by AME

generation and the toxicity/benefit ratio experienced in patients

with infected with AME-producing bacteria (18). These factors highlight the need for

a next-generation AG antibiotics with unquestionable efficacy and

little toxicity. Plazomicin has exhibited notable bactericidal

action (observed in 2010) against most AG-resistant organisms with

lower toxicity (9,19-21).

The United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) approved

the plazomicin antibiotic (formerly known as ACHN-490) in June

2018(22). Plazomicin is a

semisynthetic antimicrobial that has been created to target MDR

Enterobacterales including carbapenemases, ESBLs and AME-producing

bacteria (23,24). These resistant bacteria have the

potential to cause dangerous bacterial infections that are a

problem all over the world, including ventilator-associated

pneumonia (VAP), healthcare-associated pneumonia (HAP) and blood

stream infection (BSI). Since the emergence of carbapenem-resistant

Enterobacterales (CRE), clinicians have had few alternatives for

treating MDR bacterial pathogens. Traditional AGs, such as

gentamicin, tobramycin and amikacin, have little effectiveness

against bacterial strains that can produce AMEs (22).

In the present review, the molecular

characteristics, chemical properties, mechanism of action,

antibacterial spectrum, pharmacokinetics, clinical therapeutic

indications, side effects, role in therapy and special

considerations of plazomicin are addressed.

2. Molecular characteristics, chemical

properties and mechanism of action

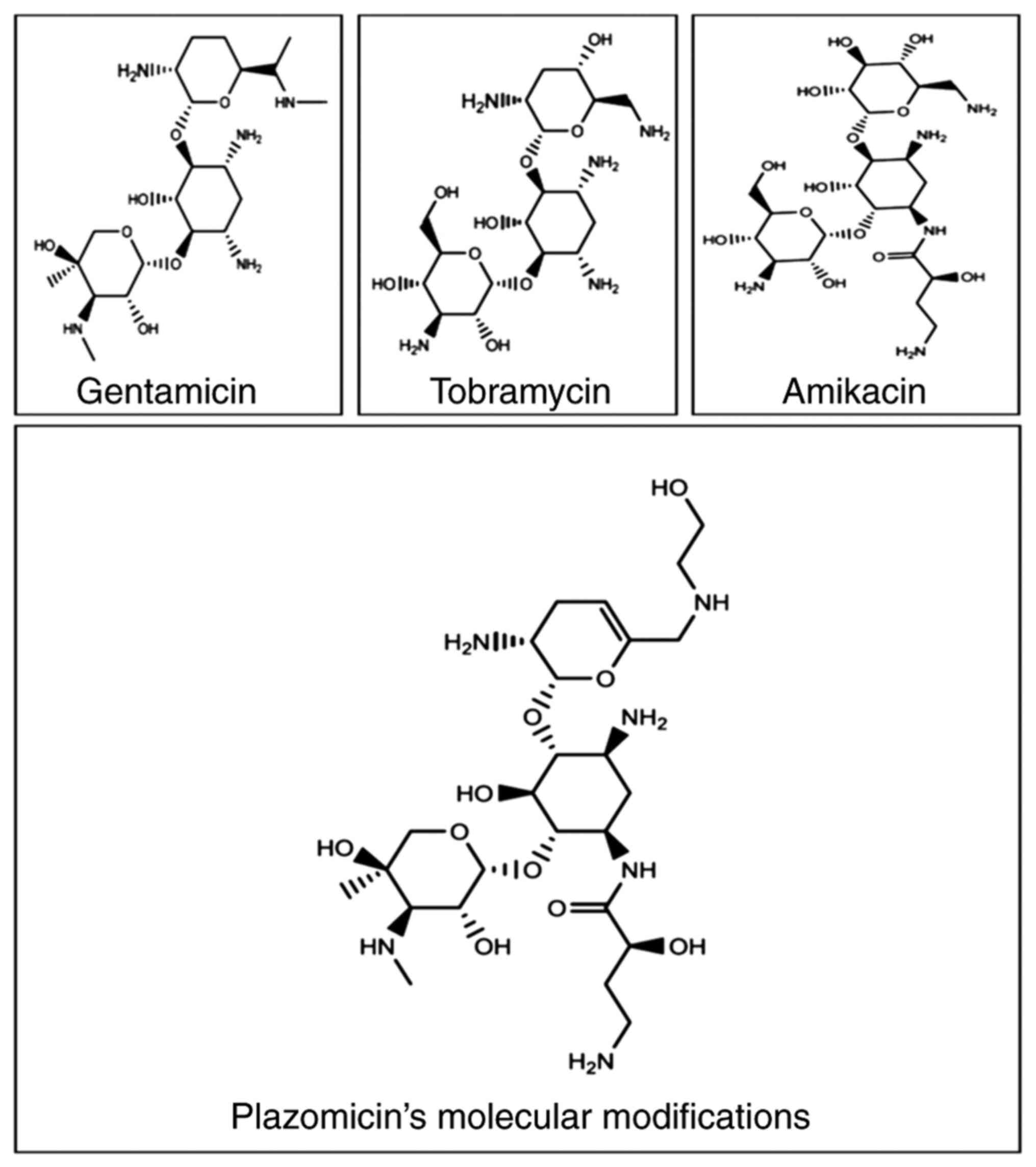

Being a semisynthetic antimicrobial, plazomicin

[6'-(hydroxylethyl)-1-(haba)-sisomicin] has a unique molecular

structure (Fig. 1) that makes it

resistant to being inactivated by a variety of enzymes produced by

MDR bacteria. Sisomicin (dehydro analog of gentamicin C1a) is the

source of plazomicin; sisomicin, similar to gentamicin, is

susceptible to several AMEs that GNB may produce (11). The majority of AMEs are inhibited

by sisomicin modifications when an N1 2(S)-hydroxy aminobutyryl and

a hydroxethyl group are added at the 6' position (25). The activity of plazomicin can be

improved against isolates producing AMEs due to these molecular

modifications, but not against 16RMT, which cause AGs (including

plazomicin) to have less affinity for the ribosomal target

(12). When compared with

sisomicin, the antibacterial effectiveness of plazomicin is only

slightly reduced by these molecular modifications; however, action

is restored in the presence of AMEs (26). Comparing plazomicin with

traditional AGs, the deleted or added domains (Table I) explain the resistance of

plazomicin to enzymatic inactivation by AMEs (9,27).

With this design, plazomicin can be prescribed not only to treat

infections caused by traditional AG-resistant Enterobacterales, but

also to treat infections caused by Enterobacterales that resist

colistin (polymyxin B) and carbapenems (carbapenemases producers),

including the bacteria that produce ESBLs (23).

| Table IRelationship between plazomicin

molecular structure and its resistance to inactivation by AMEs when

compared with traditional aminoglycosides (9). |

Table I

Relationship between plazomicin

molecular structure and its resistance to inactivation by AMEs when

compared with traditional aminoglycosides (9).

| Traditional

aminoglycosides inactivated by AMEs | Molecular of

plazomicin modifications | Plazomicin's

protection against AMEs granted from the molecular

modifications |

|---|

| Amikacin | Hydroxyl (-OH)

groups deletion |

O-phosphotransferase [APH (3')] |

| Amikacin and

tobramycin | in the C-3' and 4'

positions |

O-adenyltransferases [ANT (4')] |

| Amikacin,

gentamicin, and tobramycin | Unsaturated

hydroxyethyl group addition at the C-6' position | N-acetyltransferase

[AAC (6')] |

| Gentamicin and

tobramycin | Addition of

4-amino-2-hydroxybutanoic | N-acetyltransferase

[AAC (3')] |

| Gentamicin and

tobramycin | acid

(hydroxy-aminobutyric acid; HABA) |

O-adenyltransferases [ANT (2')] |

| Amikacin,

gentamicin, and tobramycin | at the C-1'

position. |

O-phosphotransferase [APH (2')] |

Due to the fact AGs are hydrophilic cationic

compounds, they are hypothesised to enter GNB via porin channels or

breakdown of the lipopolysaccharide outer membrane (28). AGs must be transported across the

cytoplasmic membrane, and the transport of plazomicin inside

bacterial cell cytoplasm is an aerobic energy-dependent process

that can be slowed down by a drop in pH and/or anaerobic condition.

AGs are not very effective in an anaerobic and/or acidic

environment due to the drop in their antibacterial action. The

effect of AGs relies on the proton motive force, which consists of

Δψ (electrical potential across membrane) and ΔpH (transmembrane

difference in hydrogen ion concentration) (29). The aminoacyl-transfer RNA

recognition site (A-site) of the 16S rRNA of the 30S ribosomal

subunit is the main intracellular target of action for AGs,

including plazomicin, where they interfere with bacterial protein

synthesis. Following their binding to the target site, several

intracellular steps (including severe translocation inhibition,

miscoding and complete collapse of the proteome) occur that prevent

translation, elongation of the nascent protein sequence and enhance

the bactericidal activity of AGs (30).

3. Antibacterial spectrum of plazomicin

Overall, the Gram-negative in vitro activity

of plazomicin is comparable with or superior to that of other AGs

(20,23). In nearly half of the cases

(46.97%), the bacterial pathogens tested for plazomicin activity

belong to the order Enterobacterales (9). The

Enterobacterales-susceptible/-resistant breakpoints for plazomicin

are ≤2/≥8, ≤2/≥8 and ≤4/≥8 µg/ml according to the Clinical and

Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI 2023) (31), US FDA 2019(32) and United States Committee on

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (USCAST 2019) (33), respectively. The discrepancies

between CLSI, US FDA and USCAST breakpoints were based on the most

recent pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data (34).

Between 2017 and 2021, 9,809 Enterobacterales

isolates (1/patient) were obtained in 37 medical centers in USA,

and the antimicrobial susceptibility was assessed using the broth

microdilution method, and CLSI 2023 and US FDA 2019 criteria were

used to calculate susceptibility rates. Plazomicin had strong

activity against isolates that produced ESBLs (98.9%), MDR (94.8%)

and CRE (94.0%), and it was active against 96.4% of the total

isolates. Plazomicin was markedly more effective against AMR

Enterobacterales compared with gentamicin, tobramycin or amikacin.

AMEs-encoding genes were detected in 801 (8.2%) isolates, whereas

11 (0.1%) isolates included 16RMT-encoding genes; plazomicin

inhibited 97.3% of the AMEs and none (0.0%) of the 16RMT producers

(Table II) (34,35).

| Table IIPlazomicin and comparator

antimicrobial activity against Enterobacterales (34). |

Table II

Plazomicin and comparator

antimicrobial activity against Enterobacterales (34).

| A, Enterobacterales

(n=9,809)a |

|---|

| | US FDAb | CLSI

(2023)c |

|---|

| Plazomicin and

comparator antimicrobials | MIC50,

µg/ml | MIC90,

µg/ml | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % |

|---|

| Plazomicin | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.8 | 96.4 | 0.8 | 96.4 |

| Amikacin | 2.00 | 4.00 | 0.2 | 99.4d | 1.4 | 94.6 |

| Tobramycin | 0.50 | 4.00 | 6.1 | 90.6d | 9.4 | 88.0 |

| Gentamicin | 0.50 | 2.00 | 7.7 | 91.5d | 8.5 | 90.6 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.06 | 1.0 | 98.7d | 1.0 | 98.7 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.06 | 8.00 | 16.4 | 80.3d | 16.4 | 80.3 |

| Colistin | 0.25 | >8.00 | - | - | 15.3 | 84.7e |

| B,

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases producer-Enterobacterales

(n=1,011)f |

| | US FDAb | CLSI

(2023)c |

| Plazomicin and

comparator antimicrobials | MIC50,

µg/ml | MIC90,

µg/ml | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % |

| Plazomicin | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.9 | 98.9 | 0.9 | 98.9 |

| Amikacin | 4.00 | 8.00 | 1.3 | 96.9d | 8.4 | 79.7 |

| Tobramycin | 8.00 | >16.00 | 41.7 | 43.9d | 56.1 | 40.4 |

| Gentamicin | 1.00 | >16.00 | 42.2 | 55.7d | 44.3 | 54.5 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | 5.5 | 93.5d | 5.5 | 93.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 8.00 | >16.00 | 67.2 | 23.2d | 67.2 | 23.2 |

| Colistin | 0.25 | 0.25 | - | - | 1.8 | 98.2 |

| C,

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (n=117)g |

| | US FDAb | CLSI

(2023)c |

| Plazomicin and

comparator antimicrobials | MIC50,

µg/ml | MIC90,

µg/ml | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % |

| Plazomicin | 0.25 | 1.00 | 5.1 | 94.0 | 5.1 | 94.0 |

| Amikacin | 4.00 | 32.00 | 8.5 | 75.2d | 31.6 | 59.0 |

| Tobramycin | 16.00 | >16.00 | 61.5 | 29.9d | 70.1 | 27.4 |

| Gentamicin | 4.00 | >16.00 | 35.9 | 56.4d | 43.6 | 47.0 |

| Meropenem | - | - | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| Levofloxacin | 16.00 | >16.00 | 78.6 | 14.5d | 78.6 | 14.5 |

| Colistin | 0.25 | 0.50 | - | - | 8.6 | 91.4e |

| D,

Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes producer-Enterobacterales

(n=801)h |

| | US FDAb | CLSI

(2023)c |

| Plazomicin and

comparator antimicrobials | MIC50,

µg/ml | MIC90,

µg/ml | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % |

| Plazomicin | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.4 | 97.3 | 1.4 | 97.3 |

| Amikacin | 4.00 | 16.00 | 2.0 | 94.3d | 13.1 | 68.4 |

| Tobramycin | 16.00 | >16.00 | 68.0 | 12.0d | 88.0 | 2.0 |

| Gentamicin | >16.00 | >16.00 | 83.3 | 15.2d | 84.8 | 14.0 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.25 | 7.7 | 91.4d | 7.7 | 91.4 |

| Levofloxacin | 8.00 | >16.00 | 63.4 | 29.0d | 63.4 | 29.0 |

| Colistin | 0.25 | 0.25 | - | - | 4.3 | 95.7e |

| E,

Multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales (n=844)i |

| | US FDAb | CLSI

(2023)c |

| Plazomicin and

comparator antimicrobials | MIC50,

µg/ml | MIC90,

µg/ml | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % |

| Plazomicin | 0.25 | 1.00 | 2.5 | 94.8 | 2.5 | 94.8 |

| Amikacin | 4.00 | 16.00 | 2.0 | 94.0d | 13.3 | 71.0 |

| Tobramycin | 16.00 | >16.00 | 59.1 | 20.1d | 79.9 | 15.2 |

| Gentamicin | >16.00 | >16.00 | 59.0 | 36.4d | 63.6 | 33.8 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 4.00 | 12.0 | 85.5d | 12.0 | 85.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 8.00 | >16.00 | 72.8 | 16.5d | 72.8 | 16.5 |

| Colistin | 0.25 | 0.50 | - | - | 8.6 | 91.4e |

| F, Extensively drug

resistant Enterobacterales (n=84)j |

| | US FDAb | CLSI

(2023)c |

| Plazomicin and

comparator antimicrobials | MIC50,

µg/ml | MIC90,

µg/ml | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % |

| Plazomicin | 0.25 | 1.00 | 6.0 | 94.0 | 6.0 | 94.0 |

| Amikacin | 8.00 | >32.00 | 11.9 | 65.5d | 44.0 | 41.7 |

| Tobramycin | >16.00 | >16.00 | 86.9 | 0.0d | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Gentamicin | 8.00 | >16.00 | 48.8 | 40.5d | 59.5 | 29.8 |

| Meropenem | 16.00 | >32.00 | 88.1 | 2.4d | 88.1 | 2.4 |

| Levofloxacin | >16.00 | >16.00 | 95.2 | 0.0d | 95.2 | 0.0 |

| Colistin | 0.25 | 0.50 | - | - | 7.1 | 92.9e |

| G,

Amikacin-non-susceptible Enterobacterales based on 2023 CLSI

criteria (n=528) |

| | US FDAb | CLSI

(2023)c |

| Plazomicin and

comparator antimicrobials | MIC50,

µg/ml | MIC90,

µg/ml | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % | Resistant, % | Susceptible, % |

| Plazomicin | 1.00 | 4.00 | 6.4 | 86.4 | 6.4 | 86.4 |

| Amikacin | 8.00 | 32.00 | 3.6 | 89.4d | 26.5 | 0.0 |

| Tobramycin | 8.00 | >16.00 | 49.4 | 46.0d | 54.0 | 42.2 |

| Gentamicin | 2.00 | >16.00 | 31.8 | 66.9d | 31.1 | 66.9 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.50 | 8.7 | 90.7d | 8.7 | 90.7 |

| Levofloxacin | 4.00 | >16.00 | 54.4 | 42.6d | 54.4 | 42.6 |

| Colistin | 0.25 | >8.00 | - | - | 16.5 | 83.5e |

Plazomicin use can be an effective method for

treating carbapenems-resistant bacterial infections, particularly

in countries where the prevalence of AMR is rising, including

countries in Europe and Asia (9).

Plazomicin was found to be more effective compared with the other

tested AGs and comparable with ceftazidime/avibactam and

merpenem/vaborbactam when tested against ESBLs-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae, ESBL-producing Escherichia

coli, CRE and colistin-resistant Enterobacterales (Table III) (22). Alternatively, it was reported that

plazomicin displayed low activity against Acinetobacter

species (mostly A. baumannii) (17,23),

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (24) and Stenotrophomonas

maltophilia (22) with an MIC

to inhibit 90% of tested strains (MIC90) of ≥16, ≥16 and

>64 µg/ml, respectively. Moreover, plazomicin has been tested by

Castanheira et al (13)

against 99 Acinetobacter species isolated from European

nations (13), and the results

showed that it had a MIC90 of >128 µg/ml and a

susceptibility of 40.0%. This low activity was not superior to

those of other comparator drugs, including gentamicin, amikacin,

levofloxacin and meropenem, which displayed susceptibilities

ranging from 34-41%. A total of 90% of these Acinetobacter

species strains were susceptible to colonistin. Furthermore, the

authors tested plazomicin against 60 Enterobacterales isolates that

are producers of 16RMT, but it displayed no activity with

MIC50/MIC90 of >128/>128 µg/ml

(13).

| Table IIIPlazomicin and comparator

antimicrobial in vitro MIC90 against some

resistant Gram-negative bacterial isolates (22). |

Table III

Plazomicin and comparator

antimicrobial in vitro MIC90 against some

resistant Gram-negative bacterial isolates (22).

| | MIC90,

µg/ml (% susceptible) |

|---|

| Organism | Plazomicin | Amikacin | Tobramycin | Gentamicin | Meropenem |

Meropenem/vaborbactam |

Ceftazidime/avibactam |

|---|

| ESBLs-producing

Escherichia coli (n=343) | 1.00 (100.0) | 8.00 (98.8) | 32.00 (55.7) | >32.00

(67.1) | 0.06 (99.7) | 1.00 (100.0) | 0.50 (NA) |

| ESBLs-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=73) | 0.50 (98.6) | 8.00 (100.0) | 32.00 (37.0) | >32.00

(49.3) | 0.50 (93.2) | 0.50 (99.3) | 1.00 (NA) |

|

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales

(n=110) | 1.00 (98.1) | 32.00 (23.6) | 64.00 (3.6) | 16.00 (81.8) | ≥16.00 (2.7) | 32.00 (79.6) | 2.00 (97.5) |

| Colistin-resistant

Enterobacterales (n=95) | 4.00 (93.7) | 32.00 (21.0) | 32.00 (8.0) | 64.00 (12.0) | 16.00 (12.0) | NA | 2.00 (99.5) |

Plazomicin had comparable anti-Gram-positive isolate

activity to other AGs (22,24)

(Table IV); methicillin-resistant

and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus are both

susceptible with an MIC90 of 1 µg/ml and a

MIC90 ≤0.5 µg/ml, respectively. Plazomicin also

demonstrated strong efficacy against Staphylococcus

epidermidis. Plazomicin are not effective against streptococci;

its MIC90 values for Streptococcus agalactiae,

Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes

are 64, 32 and 32 µg/ml, respectively. Plazomicin is similarly

ineffective against Enterococcus faecalis and

Enterococcus faecium strains with MIC90 >64

and 16 µg/ml, respectively (22).

No notable activity of plazomicin has been demonstrated against the

Clostridium species, other Gram-positive anaerobes and

Gram-negative anaerobes (specifically Bacteroides and

Prevotella species) (18).

| Table IVPlazomicin and comparator

antimicrobial in vitro MIC90 against some

Gram-positive bacterial isolates (22). |

Table IV

Plazomicin and comparator

antimicrobial in vitro MIC90 against some

Gram-positive bacterial isolates (22).

| | MIC90,

µg/ml (% susceptible) |

|---|

| Organism | Plazomicin | Amikacin | Tobramycin | Gentamicin | Vancomycin |

|---|

|

Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus

aureus (n=3,009) | 1.00 (NA) | 4.00 (NA) | ≤0.50 (NA) | ≤0.50 (98.6) | 1.00 (100.0) |

|

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus (n=687) | 1.00 (NA) | 32.00 (NA) | >64.00 (NA) | ≤0.50 (96.2) | 1.00 (99.7) |

|

Methicillin-susceptible Staph.

epidermidis (n=339) | 0.25 (NA) | 4.00 (NA) | 16.00 (NA) | >32.00

(69.3) | 2.00 (100.0) |

|

Methicillin-resistant Staph.

epidermidis (n=25) | 0.50 (NA) | 16.00 (NA) | >64.00 (NA) | >32.00

(20.0) | 2.00 (100.0) |

Recently, it was reported that plazomicin was

effective in monotherapy (9).

Plazomicin in combination with numerous antibiotics appears to

inhibit the development of AMR without posing any hazards (36). The synergy of plazomicin with other

antibiotics (such as carbapenems, ceftazidime and

piperacillin/tazobactam) used to treat complicated infections is

notable; it can be utilized in combination to treat severe

Gram-negative infections caused by MDR Enterobacterales, including

isolates that are resistant to β-lactams and AGs. Carbapenems in

combination with plazomicin showed synergism against

Acinetobacter baumannii (22).

Plazomicin has also been shown to have in

vitro synergistic activity against Pseudomonas

aeruginosa when combined with cefepime, imipenem, doripenem or

piperacillin-tazobactam, as well as against methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus, heteroresistant

vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA), VISA

and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus when combined

with ceftobiprole or daptomycin (37).

4. Bacterial resistance to plazomicin

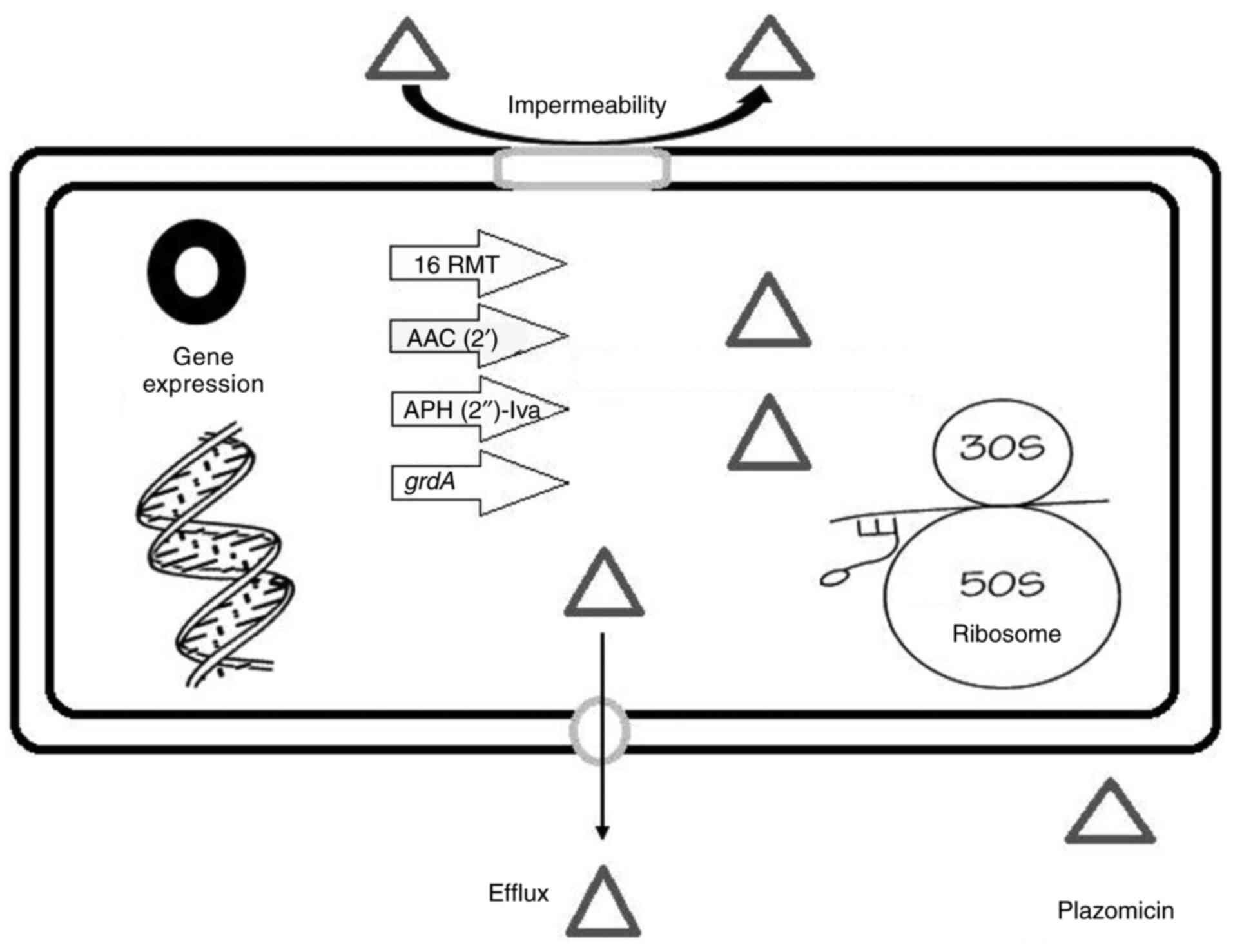

Fig. 2 shows a

schematic representation of the resistance determinants of

plazomicin. Clark and Burgess (38) reported that the identification of

plazomicin-resistant bacteria was uncommon, and the expression of

16RMT was confirmed among the plazomicin-resistant isolates.

High-level resistance to classical AGs (gentamicin, tobramycin and

amikacin) as well as plazomicin is caused by acquired 16RMT such as

ArmA and RmtC (18). Plazomicin is

ineffective against bacteria that express 16RMT isolated mainly in

East Asia and occasionally co-expressed with the New Delhi

metallo-β-lactamase (NDM). Furthermore, the bacterial phenotypes

co-expressing 16RMT with NDM have occasionally been observed in the

US, other nations in Europe and Asia have reported a more

widespread frequency (9).

Co-expression of 16RMT with OXA-48-carbapenemases is not uncommon.

Thus, plazomicin should be used with caution when treating

Enterobacterales that express NDM or OXA-48, and it is advisable to

use commercially available rapid detection kits capable of

detecting carbapenemases production, particularly NDM, prior to

empirical administration of plazomicin (9).

As previously established, structural changes in

plazomicin shield it against all clinically notable AMEs. The AAC

(2')-I is an AME that is known to have anti-plazomicin activity

among GNB, and it is chromosomally expressed in some isolates of

Providencia stuartii (17).

Notably, the AAC (2')-I encoding gene appears not to have

transferred to any other bacterial species (17). APH (2')-Iva is another known AME

with anti-plazomicin activity; however, this enzyme has only been

found in the Enterococcus species for which plazomicin would

not be considered a recommended therapy option (25).

Bacterial resistance against plazomicin (as in

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter) can also be

generated by additional AG resistance mechanisms, such as efflux

pumps or drug impermeability with down-regulation of porin

channels. Therefore, traditional AGs can be more effective against

Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Acinetobacter baumannii

compared with plazomicin regardless of the absence or presence of

AMEs (18).

Salmonella enterica strains with the

gentamicin resistance gene (grdA) are extremely resistant to

plazomicin (MIC >256 µg/ml) according to a study from the USA

(39). Compared with the

previously identified plazomicin-resistant AMEs AAC

(2')-Ia and APH (2')-Iva, these results show

that grdA confers markedly greater resistance to plazomicin

(39). Healthcare professionals

should continue to use plazomicin susceptibility testing because

tests for identifying the genetic type of bacterial resistance are

not always easily available (22).

5. Pharmacokinetics and dosing

As with other AGs, plazomicin has modest plasma

protein binding (~20%) and first-order linear elimination and is

mainly excreted by the kidneys (glomerular filtration) without

undergoing plasma or hepatic metabolism (9). Plazomicin must be taken parenterally

because, similar to other AGs, it is poorly absorbed. The volume of

distribution (Vd) of the AGs is ~25% of body weight, which is

comparable with the volume of extracellular fluid, and they do not

penetrate most cells. Adults with cUTIs and healthy adults both had

mean Vd values of 18 and 31 liters, respectively, for plazomicin.

In patients with cUTI, the mean maximum serum concentration was 51

mg/l and the area under the concentration time curve was 226 mg h/l

after receiving a single intravenous (IV) dosage of plazomicin (15

mg/kg). Plazomicin neither induces nor inhibits the cytochrome P450

drug-metabolizing enzymes, it is not metabolized to any

considerable level and in patients with normal renal function, the

typical serum elimination half-life of plazomicin is ~3.5 h

(22).

Assessing the effectiveness of plazomicin against

respiratory infections, particularly in patients with resistant

bacteria, requires an understanding of its distribution in lung

tissue. Plazomicin can infiltrate the lungs to a comparable extent

to amikacin even without lung inflammation (40). Plazomicin showed little to no

affinity for melanin; therefore, it is unlikely that it will be

retained in pigmented skin tissues (18). Plazomicin is supplied as a single

use, fliptop, 10-ml vial containing 500 mg plazomicin (50 mg/ml),

and sterilely compounded products are stable for 24 h at room

temperature (41). The US FDA has

approved a single daily IV infusion dose of 15 mg/kg, given over 30

min in 0.9% sodium chloride or lactated Ringers. After the initial

dose, TDM should be used to adjust the dosing interval by 1.5 folds

to keep the plasma trough concentration (the concentration of drug

in the blood immediately before the next dose is given) <3 µg/ml

(38). Plazomicin's renal

clearance is comparable with its overall body clearance; following

a single 15 mg/kg IV injection, 56 and 97.5% of the unmodified

plazomicin is excreted in urine within the first 4 h and a week,

respectively, with <0.2% recovered in stool (42).

To reduce toxicity, a reduction in the dose of

plazomicin is recommended in patients suffering from moderate

(creatinine clearance <60 ml/min) and severe (creatinine

clearance <30 ml/min) renal impairment to 10 mg/kg every 24 h

and 10 mg/kg every 48 h, respectively (22). The following formula should be used

to determine the adjusted body weight (ABW): For patients whose

total body weight (TBW) is >25% greater than IBW, ABW=ideal body

weight (IBW) + 0.4 (TBW-IBW) (41).

6. Clinical therapeutic indications

The US FDA has approved plazomicin for cUTIs and

acute pyelonephritis (AP) treatment in patients aged 18 years and

older when these infections are caused by susceptible bacteria with

few or no other therapeutic options (41,43).

A general review of plazomicin data has clearly highlighted two

clinical indications (38) as

presented in Table V: cUTI

(approved by the US FDA after passing the phase 2 clinical trial

NCT01096849(44) and the

Evaluating Plazomicin In cUTI (EPIC) trial (45) and serious CRE infections including

BSI, VAP and HAP (up to date, it is not approved by the US FDA

after premature termination of the Combating Antibiotic-Resistant

Enterobacteriaceae (CARE) trial (46).

| Table VSummary of plazomicin clinical trials

in phase II and III. |

Table V

Summary of plazomicin clinical trials

in phase II and III.

| Trial | Phase | Indication | Primary

outcome | Results, n (%) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| P2-01 (trial no.

NCT01096849) | II | cUTI | Microbiological

recurrence at TOC visit (1 month following the final dose of the

study drug) | Plazomicin 9

(6.5) | Levofloxacin 34

(23.5) | (44) |

| | | | Serum creatinine

increases ≥0.5 mg/dl | 5 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| EPIC (trial no.

NCT02486627) | III | cUTI | Composite

curea on 5th day of

therapy | Plazomicin 168

(88.0) | Meropenem 180

(91.4) | (45) |

| | | | | Statistical

difference, 3.4% (95% CI, -10.0-3.1%) in favor of plazomicin | |

| | | | Composite

curea at TOC visit

(after IV therapy initiation by 15-19 days) | 156 (81.7) | 138 (70.1) | |

| | | | | Statistical

difference, 11.6% (95% CI, 2.7-20.3%) in favor of plazomicin | |

| CARE (trial no.

NCT01970371) | III | Serious CRE

infections (including BSI, HAP and VAP) | Disease-related

complications or all-cause mortality at 28 days in the

microbiologic modified intent-to-treat population (those with a

confirmed CRE infection who received at least one dosage of the

trial drug) |

Plazomicinb 4(24) |

Colistinb 10(50) | (46) |

| | | | | Statistical

difference, 26% (95% CI, -55-6%) in favor of plazomicin | |

Connolly et al (44) performed the phase 2 clinical trial

(trial no. NCT01096849) for comparing the efficacy and safety of

plazomicin (15 mg/kg/day) with levofloxacin (750 mg/day) by IV for

the treatment of cUTI and AP. In this multicenter, randomized,

double-blind research, 145 patients participated. In comparison

with the levofloxacin treatment group, the plazomicin treatment

group experienced a lower rate of microbiological recurrence (6.5

vs. 23.5%) 1 month following the final dose of the study drug.

Furthermore, 3.4% of the plazomicin therapy group experienced an

increase in serum creatinine of ≥0.5 mg/dl, although none of the

levofloxacin treatment groups did.

The EPIC study group (45) reported that plazomicin was

non-inferior when compared with meropenem for the treatment of cUTI

and AP. This study was a multicenter, international, randomized,

double-blind phase 3 trial. Plazomicin was demonstrated to be

non-inferior to meropenem regarding composite (microbiological and

clinical) cure on day 5 of therapy and at the test-of-cure (TOC)

visit, which occurred 15 to 19 days after the start of IV therapy.

In brief, after at least 4 days, the trial assessed the

effectiveness of IV plazomicin (15 mg/kg once daily) and IV

meropenem (1 g/8 h) for 7-10 days, followed by optional oral

levofloxacin 500 mg once a day, and there was no TDM performed. The

main goals were to show that plazomicin was non-inferior to

meropenem based on the variance in the clinical cure rates and

microbiological cure rates on days 5 and 15-19 after the start of

therapy. A 15% non-inferiority margin was applied during the

trials. Escherichia coli was the most prevalent uropathogen,

followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae. On day 5 of therapy,

plazomicin had a composite (microbiological and clinical) rate of

168 out of 191 cases (88%), whereas meropenem had a cure rate of

180 out of 197 cases (91.4%). Plazomicin and meropenem had

composite cure rates of 156 of 191 (81.7%) and 138 of 197 (70.1%),

respectively at the TOC visit. Furthermore, a rise in serum

creatinine of ≥0.5 mg/dl occurred in 3.7 and 3.0% of plazomicin and

meropenem treatment groups, respectively. Moreover, 100 and 81.8%

of patients taking meropenem and plazomicin, respectively,

experienced complete renal recovery.

In the CARE trial, plazomicin (15 mg/kg/day)-based

combinations were compared with colistin (5 mg/kg/day)-based

combinations with adjunctive meropenem or tigecycline in patients

with CRE-related BSI, HAP and VAP. Although preliminary findings

suggested that the plazomicin group had lower all-cause mortality

(at 28 days) and fewer major adverse events including

nephrotoxicity, the study was discontinued early due to the limited

number of the enrolled patients (a total of 39 individuals were

enrolled as the following; 29 patients having proven CRE-related

BSI, 8 patients having proven CRE-related HAP or VAP and

CRE-related infection was not proven in 2 patients) (46). Thus, the US FDA has not approved

plazomicin's use in case of bacterial infections causing BSI, HAP

and VAP as the findings lacked the strength required for accurate

hypothesis testing (22). Data

from the USA has demonstrated notable bactericidal activity against

a wide range of bacteria that are resistant to AGs, β-lactams,

fluoroquinolones and carbapenems, including the MDR isolates

(resistant to ≥1 agent in ≥3 different antibiotic classes)

(34). The data presented by

Alfieri et al (9) is

encouraging for the use of plazomicin monotherapy or in combination

with another antibiotic in three key scenarios (cUTI, BSI and VAP);

however, the research team recommended that data meta-analysis is

required to characterize the benefits.

7. Side effects and safety profile

The safety profile of traditional AGs reveals that

they have always had a wide range of adverse effects, particularly

when compared with the β-lactam antibiotics (9). Nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity and

neuromuscular inhibition are the three most reported toxicities of

AGs. Nephrotoxicity affects 3-11% of individuals, whereas

vestibular and cochlear toxicity affect 10 and 26% of patients,

respectively (Table VI) (6). The nephrotoxicity caused by AGs is

caused by drug accumulation in the cortical portion of the kidney.

It is a reversible process that relies on the capacity of tubular

epithelial cells to regenerate. As a result, in cases of patients

with poor kidney functions, a dose reduction must be considered

(9). Ototoxicity, on the other

hand, is the result of direct oxidative damage to the vestibular

organ, cochlea and its hairy cells and related cranial nerves. The

resulted harm is permanent; thus, it must be avoided. When used in

combination with AGs, aspirin, N-acetylcysteine, dexamethasone and

antioxidant compounds as N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists

have been shown to effectively reduce ototoxicity (9).

| Table VIMain side effects of AGs (6). |

Table VI

Main side effects of AGs (6).

| | | Risk factors of

toxicity | | |

|---|

| Toxicity types | Effects of

toxicity | Clinical | Therapeutic | Potential treatment

of toxicity | Prevention of

toxicity |

|---|

| Renal | Acute injury of the

kidney with preserved diuresis; tubular necrosis | Age; chronic renal

disease; dehydration; hyperthermia | Previous treatment

with AG; cumulative dose; treatment duration >5 days | Dose adaptation

through TDM; stop AG when unnecessary | Avoid

co-nephrotoxic drugs; avoid cumulative risk factors; TDM |

|

Cochleovestibular | Cochlear-hearing

loss, tinnitus; vestibular-ataxia, vertigo, nystagmus | Past history of

hearing loss | Previous treatment

with AG; cumulative dose; treatment duration >5 days | Dose adaptation

through TDM; stop AG when unnecessary | Avoid

co-nephrotoxic drugs; avoid cumulative risk factors; TDM |

| Neuromuscular | Neuromuscular

block | Myasthenia gravis;

immediate postoperative period; respiratory acidosis | - | Anti-cholinesterase

drugs | Avoid

co-nephrotoxic drugs; avoid cumulative risk factors; TDM |

The US FDA added a black box warning for

nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, neuromuscular blockade and pregnancy

risk when approving plazomicin (41,43).

Plazomicin is an AG, hence notable renal damage is to be expected;

however, the renal toxicity of plazomicin is near that of

meropenem, a rise in serum creatinine of ≥0.5 mg/dl from baseline

occurred in 3.7 and 3.0% of plazomicin and meropenem treatment

group, respectively. It is important to remember that the kidney

damage induced by plazomicin is reversible, with most patients

(81.8%) having complete renal function at the time of discharge in

the EPIC study (45). Both

plazomicin and meropenem groups reported the same adverse events in

the EPIC study including hypotension (1.0%), headache (1.3%),

nausea (1.3%), vomiting (1.3%), diarrhea (2.3%) and hypertension

(2.3%). Moreover, in the EPIC trial, there was only one instance of

Clostridoides difficile in the comparator group and none in

the plazomicin group. On the other hand, there was a single

mortality in the plazomicin group (a patient passed away on trial

day 18 from metastatic uterine cancer that had been discovered 48 h

after enrolment) (45).

Cochlear and vestibular function were assessed in a

study performed on healthy participants, at baseline and up to 6

months after starting plazomicin treatment, and revealed no signs

of ototoxicity, suggesting that plazomicin has a low potential for

ototoxicity (40). As the

plazomicin reports in the phase 3 trial were not based on cochlear

and vestibular examinations, adverse events with possible

ototoxicity seemed to be rare. Although there is a documented risk

of ototoxicity connected with AGs, the plazomicin phase 3 trials

were unable to identify any possible ototoxicity associated with

plazomicin treatment (22).

According to previous findings, plazomicin is not ototoxic; thus,

it is safe, as well as practical and effective (47). Alfieri et al (9) reported that ototoxicity occurred in

<2% of patients in numerous trials, on average.

The clinical investigations of plazomicin to date

have not revealed any evidence of the AG class danger of

neuromuscular blocking leading to respiratory depression. However,

care should be taken when prescribing plazomicin to patients who

have a neuromuscular condition such as myasthenia gravis or to

individuals who are receiving neuromuscular blockers such as

succinylcholine because doing so could delay the neuromuscular

function recovery (22).

When provided to patients who are pregnant, AGs,

including plazomicin, can cross the placenta and cause fetal harm.

Streptomycin has been linked to multiple reports of complete,

irreversible, bilateral congenital deafness in young children who

were exposed in utero. Female patients should be informed of

the potential risk to the fetus if they use plazomicin while

pregnant or become pregnant while using plazomicin. To the best of

our knowledge, there is no data available on the presence of

plazomicin in human milk, its effects on breastfed infants or its

effects on milk production, but minimal levels are anticipated in

milk based on the excretion of other AGs; however, plazomicin has

been found in rat milk (41,43).

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

expects low plazomicin excretion in human milk (based on the

excretion of other AGs). Thus, the institute recommends the

inspection of any effects on the gastrointestinal flora of the

baby, such as diarrhea, candidiasis (such as thrush or diaper rash)

or infrequently, blood in the stool, which could be a sign of

antibiotic-associated colitis, when prescribing plazomicin to

lactating females (48). The

safety and effectiveness of plazomicin in patients <18 years

have not been demonstrated (41,43).

8. Role in therapy and special

considerations

Due to the potential for antimicrobials to lose

their effectiveness in treating infectious diseases, it is

imperative to consider newly developed antimicrobials and put

preventive measures in place to stop the emergence of AMR (49). The real-world therapeutic

experience will define the role of plazomicin as a monotherapy

and/or combination therapy. The therapeutic usage of AGs and

polymyxin antibiotics has increased because of the global spread of

MDR GNB. The majority of Enterobacterales that are resistant to the

traditional AGs can still be killed by plazomicin (20); thus, there are multiple potential

roles for plazomicin in therapy depending on its higher potency

(lower MICs) against numerous bacterial pathogens.

Plazomicin is effective in vitro against a

variety of isolates that produce ESBLs and carbapenemase enzymes

(19). However, with this class of

antibiotics, strong in vitro activity does not always

indicate clinical efficacy. A poor outcome was noticed while using

AGs in treating patients suffering from pneumonia and explained by

their low concentrations in alveolar lining fluid and inactivation

by the acidic pH within the inflamed lung tissue (50). Therefore, before accepting

plazomicin for extended usage, more clinical trials using

plazomicin in a variety of diseases, particularly pneumonias, are

required. However, due to the lack of therapeutic options for the

management of MDR bacterial infections, plazomicin may thus play a

special role in antibacterial therapy.

For patients with cUTI, AGs, including plazomicin,

were suggested over tigecycline (9,51).

Plazomicin offers certain dosage advantages compared with other

antimicrobials, including β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors, which

are effective against MDR GNB. Plazomicin can be administered

intravenously, once daily over a brief period of 30 min, and

hospitalized patients may benefit from this administration

schedule, but those undergoing outpatient parenteral antibiotic

therapy will especially benefit from it (52). However, plazomicin-associated

toxicity, especially nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity, is an area of

doubt, and it is important to monitor renal function. Notably, when

the benefits of plazomicin use as antibacterial therapy are weighed

against its side effects, the drug safety in comparison to

conventional AGs is notable (9).

In terms of drug-drug interactions, 90% of metformin

is eliminated via renal tubular secretion through three

transporters (multidrug and toxin extrusion 2-K, multidrug and

toxin extrusion 1 and organic cation transporter 2). Although

plazomicin selectively inhibits these transporters with variable

degrees, there are no noticeable changes in the blood metformin

levels when plazomicin was administered concurrently with

metformin, according to a study assessing the possibility of

interaction (53). Furthermore,

another study investigating the effect of plazomicin intake on the

heart found no discernible changes in the QT interval length

(54). Similar to other AGs, the

major drug interaction of concern would likely be additive toxicity

when combined with other nephrotoxic drugs (18).

As with other antimicrobials created for the

treatment of MDR GNB, plazomicin has a high acquisition cost

(55). The actual market entry

price of plazomicin per treatment course was $4,955.11 at the time

of commercialization in 2018(56).

The price of the recently approved antimicrobials with anti-CRE

activity against cUTIs, such as ceftazidime-avibactam (February

2015) and meropenem-vaborbactam (August 2017), was taken into

consideration while setting the price of plazomicin. In 2019, the

cost of purchasing plazomicin at wholesale was $945.00 a day, based

on a dosage of a patient weighing 75 kg, and ceftazidime-avibactam

and meropenem-vaborbactam were $1,076 and $990, respectively,

whereas colistin ($56.00 per day) and polymixin B ($21.78-45.00)

were markedly less expensive (57).

As a result, healthcare professionals may have

concerns about the cost of plazomicin therapy. Antimicrobial

stewardship will be necessary to avoid this cost and the cost of

its TDM. On the other hand, clinicians should also consider that

plazomicin monotherapy can improve the prognosis of patients with

MDR bacteria, reduce the likelihood of infection progression to

septic shock and shorten the hospitalization duration (58). For patients with severe infections,

plazomicin therefore may enable the reduction of the overall cost

of treatment (59). The additional

hospital expenses per patient for antibiotic-resistant

healthcare-associated infections among U.S. patients were estimated

by Achaogen to be >$15,000(60).

As mentioned before, cUTIs are the focus of most

plazomicin related therapeutic data (9). The scarcity of data from clinical

trials other than cUTIs is the main issue with non-extensive

therapeutic use of plazomicin (59). Randomized controlled trials were

identified by a recent systematic literature review that aimed to

evaluate the relative effectiveness of different treatment options

for cUTIs and AP. The study concluded that plazomicin demonstrated

notably higher relative efficacy vs. carbapenems for both composite

outcome and microbiological eradication at TOC (61).

The role of certain AG in therapy should be

connected to the susceptibility of the organism producing the

infection rather than the infection site (62). A study from Egypt concluded that

plazomicin displayed the most potent in vitro activity

against carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative intensive care unit

(ICU) and non-ICU isolates when compared with meropenem-vaborbactam

(carbapenem combined with a β-lactamase inhibitor) and omadacycline

(a semisynthetic minocycline derivative), with plazomicin

inhibiting 82.22% of CRE isolates. The tested samples in the study

included non-ICU samples (urine and surgical wound swabs), and ICU

samples (urine, blood, sputum, endotracheal aspirates,

bronchoalveolar lavage, peritoneal fluid aspirate, pericardial

fluid aspirate, pleural fluid aspirates, CSF, infected burn wounds

swabs and surgical wound samples) (63).

Most likely, plazomicin will be utilized either

alone to treat MDR cUTIs or in combination to treat severe CRE

infections, especially those having a variety of AMEs (38). Moreover, plazomicin has been used

in the treatment of patients with infections including the UTIs,

BSIs and VAPs if caused by plazomicin susceptible organisms. The

European Medicines Agency approved the drug because of these

encouraging results against the susceptible bacteria, but it is not

yet available in the market (6).

Despite their hydrophilicity, AGs effectively

penetrate bone and joint tissues (64). Plazomicin was discovered to be

active and superior to traditional AGs against CRE isolates from

skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) (65); however, the relevance of plazomicin

in the treatment of SSTIs, bone infections and diabetic foot

infections is still understudied (66). In the US, plazomicin showed little

or no activity against Achromobacter infections (including

respiratory, blood, genitourinary and wound infections), with

MIC50/MIC90 of >4/>4 µg/ml (67).

Plazomicin research has been limited by the fact

that it has only been used for conditions that affect the urinary

system and by the fact that varied ethnicities and patients who are

seriously unwell, such as those who have bacteremia and pneumonia,

are underrepresented (22).

According to the aforementioned information, plazomicin is a

reasonably expensive drug that should be used sparingly, but it can

enable patients with serious infections to save money on their

entire course of treatment (9).

9. Conclusions and recommendations

Plazomicin is a promising semisynthetic

antimicrobial that has been created to target MDR bacterial

pathogens, especially GNBs. Except for the approved use of

plazomicin to treat cUTIs, there is a gap in the literature

regarding its clinical uses for treatment of severe complicated

infections such as BSIs, HAPs and VAPs after premature termination

of the CARE trial. For the treatment of cUTIs, it is considered the

best treatment option against bacterial pathogens with poor

sensitivity to carbapenems and other alternatives. It has been

demonstrated to be non-inferior to meropenem, it is a convenient

treatment choice for outpatient antibiotic therapy settings (given

IV, once daily, with a short 30 min administration duration) and it

has low frequency side effects. Due to the rising prevalence of

highly resistant GNB and the absence or limited alternative

treatment options, plazomicin is a valuable non-β-lactam treatment

option against MDR bacterial infections such as BSIs, HAPs and

VAPs. This costly new antibacterial drug should be properly

exploited, prescribed when necessary and sparingly to maintain its

effectiveness over time. To help improve understanding of its

clinical and therapeutic importance in various bacterial illnesses,

a meta-analysis on this trending issue is advised. Clinicians using

plazomicin should recognize that the setting of clinical practice

is distinct from that of clinical trials. Thus, clinicians are

urged, as always, to review their local antibiograms and adhere to

the optimal guidelines which include proper plazomicin dosing and

administration with TDM, to achieve maximum effectiveness and least

toxicity especially for patients with a history of inner ear or

kidney diseases who should always be treated with caution.

Moreover, healthcare professionals should keep using plazomicin

susceptibility testing because tests for identifying the genetic

type of bacterial resistance are not always easily available.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present review was funded by the Deanship of

Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University, Saudi

Arabia (grant no. DGSSR-2024-01-02130).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

The present review was conceptualized by MA and AET;

the data was curated by MA, AET, IAT, HMS and GAB; funding was

acquired by MA; MA, AET, IAT, HMS and GAB were responsible for

resources and project administration; the project was supervised by

MA, AET, IAT, HMS and GAB; validation of references was performed

by MA, AET, IAT, HMS and GAB. Writing of the original draft was

completed by MA and AET and reviewing and editing of the manuscript

was performed by MA, AET, IAT, HMS and GAB. Data authentication is

not applicable. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Schatz A, Bugie E and Waksman SA:

Streptomycin, a substance exhibiting antibiotic activity against

gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. 1944. Clin Orthop Relat

Res. 437:3–6. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Weinstein MJ, Luedemann GM, Oden EM and

Wagman GH: Gentamicin, a new broad-spectrum antibiotic complex.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother (Bethesda). 161:1–7. 1963.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kluge RM, Standiford HC, Tatem B, Young

VM, Greene WH, Schimpff SC, Calia FM and Hornick RB: Comparative

activity of tobramycin, amikacin, and gentamicin alone and with

carbenicillin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob

Agents Chemother. 6:442–446. 1974.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Reynolds AV, Hamilton-Miller JM and

Brumfitt W: Newer aminoglycosides-amikacin and tobramycin: An

in-vitro comparison with kanamycin and gentamicin. Br Med J.

3:778–780. 1974.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Degtyareva NN, Gong C, Story S, Levinson

NS, Oyelere AK, Green KD, Garneau-Tsodikova S and Arya DP:

Antimicrobial activity, AME resistance, and A-site binding studies

of anthraquinone-neomycin conjugates. ACS Infect Dis. 3:206–215.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Thy M, Timsit JF and de Montmollin E:

Aminoglycosides for the treatment of severe infection due to

resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Antibiotics (Basel).

12(860)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

World Health Organization (WHO): Deaths

due to AMR estimated to reach 10 million people by 2050. WHO,

Geneva, 2024. https://www.who.int/indonesia/news/detail/20-08-2024-deaths-due-to-amr-estimated-to-reach-10-million-people-by-2050--ministry-of-health-and-who-launch-national-strategy.

Accessed August 31, 2025.

|

|

8

|

Coppola N, Maraolo AE, Onorato L, Scotto

R, Calò F, Atripaldi L, Borrelli A, Corcione A, De Cristofaro MG,

Durante-Mangoni E, et al: Epidemiology, mechanisms of resistance

and treatment algorithm for infections due to carbapenem-resistant

Gram-negative bacteria: An expert panel opinion. Antibiotics

(Basel). 11(1263)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Alfieri A, Di Franco S, Donatiello V,

Maffei V, Fittipaldi C, Fiore M, Coppolino F, Sansone P, Pace MC

and Passavanti MB: Plazomicin against multidrug-resistant bacteria:

A scoping review. Life (Basel). 12(1949)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Rice LB: Federal funding for the study of

antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: No ESKAPE. J

Infect Dis. 197:1079–1081. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ramirez MS and Tolmasky ME: Aminoglycoside

modifying enzymes. Drug Resist Updat. 13:151–171. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Doi Y, Wachino JI and Arakawa Y:

Aminoglycoside resistance: The emergence of acquired 16S ribosomal

RNA methyltransferases. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 30:523–537.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Woosley LN,

Serio AW, Krause KM and Flamm RK: Activity of plazomicin compared

with other aminoglycosides against isolates from European and

adjacent countries, including Enterobacteriaceae molecularly

characterized for aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and other

resistance mechanisms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 73:3346–3354.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Castanheira M, Davis AP, Serio AW, Krause

KM and Mendes RE: In vitro activity of plazomicin against

Enterobacteriaceae isolates carrying genes encoding

aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes most common in US Census

divisions. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 94:73–77. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Walkty A, Karlowsky JA, Baxter MR, Adam

HJ, Boyd D, Bharat A, Mulvey MR, Charles M, Bergevin M and Zhanel

GG: Frequency of 16S ribosomal RNA methyltransferase detection

among Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae

clinical isolates obtained from patients in Canadian hospitals

(CANWARD, 2013-2017). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 94:199–201.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Nikaido H and Takatsuka Y: Mechanisms of

RND multidrug efflux pumps. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1794:769–781.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Aggen JB, Armstrong ES, Goldblum AA, Dozzo

P, Linsell MS, Gliedt MJ, Hildebrandt DJ, Feeney LA, Kubo A, Matias

RD, et al: Synthesis and spectrum of the neoglycoside ACHN-490.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 54:4636–4642. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Eljaaly K, Alharbi A, Alshehri S, Ortwine

JK and Pogue JM: Plazomicin: A novel aminoglycoside for the

treatment of resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Drugs.

79:243–269. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Haidar G, Alkroud A, Cheng S, Churilla TM,

Churilla BM, Shields RK, Doi Y, Clancy CJ and Nguyen MH:

Association between the presence of aminoglycoside-modifying

enzymes and in vitro activity of gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin,

and plazomicin against Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-

and extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing enterobacter species.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 60:5208–5214. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Thwaites M, Hall D, Shinabarger D, Serio

AW, Krause KM, Marra A and Pillar C: Evaluation of the bactericidal

activity of plazomicin and comparators against multidrug-resistant

Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 62:e00236–18.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Karaiskos I, Lagou S, Pontikis K, Rapti V

and Poulakou G: The ‘old’ and the ‘new’ antibiotics for MDR

Gram-negative pathogens: For whom, when, and how. Front Public

Health. 7(151)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Saravolatz LD and Stein GE: Plazomicin: A

new aminoglycoside. Clin Infect Dis. 70:704–709. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Castanheira M, Davis AP, Mendes RE, Serio

AW, Krause KM and Flamm RK: In vitro activity of plazomicin against

Gram-negative and gram-positive isolates collected from U.S.

Hospitals and comparative activities of aminoglycosides against

carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and isolates carrying

carbapenemase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 62:e00313–18.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Walkty A, Karlowsky JA, Baxter MR, Adam HJ

and Zhanel GG: In vitro activity of plazomicin against

Gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial pathogens isolated from

patients in Canadian hospitals from 2013 to 2017 as part of the

CANWARD surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.

63:e02068–18. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Cox G, Ejim L, Stogios PJ, Koteva K,

Bordeleau E, Evdokimova E, Sieron AO, Savchenko A, Serio AW, Krause

KM and Wright GD: Plazomicin retains antibiotic activity against

most aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. ACS Infect Dis. 4:980–987.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Sonousi A, Sarpe VA, Brilkova M, Schacht

J, Vasella A, Böttger EC and Crich D: Effects of the 1-N-(4-Amino-2

S-hydroxybutyryl) and 6'-N-(2-Hydroxyethyl) substituents on

ribosomal selectivity, cochleotoxicity, and antibacterial activity

in the sisomicin class of aminoglycoside antibiotics. ACS Infect

Dis. 4:1114–1120. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Armstrong ES and Miller GH: Combating

evolution with intelligent design: The neoglycoside ACHN-490. Curr

Opin Microbiol. 13:565–573. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Garneau-Tsodikova S and Labby KJ:

Mechanisms of resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics: Overview

and perspectives. Medchemcomm. 7:11–27. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lebeaux D, Chauhan A, Létoffé S, Fischer

F, de Reuse H, Beloin C and Ghigo JM: pH-mediated potentiation of

aminoglycosides kills bacterial persisters and eradicates in vivo

biofilms. J Infect Dis. 210:1357–1366. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Parajuli NP, Mandava CS, Pavlov MY and

Sanyal S: Mechanistic insights into translation inhibition by

aminoglycoside antibiotic arbekacin. Nucleic Acids Res.

49:6880–6892. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Clinical and Laboratory Standards

Institute (CLSI): M100Ed33. Performance standards for antimicrobial

susceptibility testing. CLSI, Wayne, PA, 2023.

|

|

32

|

US Food and Drug Administration:

Antibacterial susceptibility test interpretive criteria 2019.

https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/antibacterial-susceptibility-test-interpretive-criteria.

Accessed June 6, 2025.

|

|

33

|

The United States Committee on

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (USCAST): Breakpoint tables

for interpretation of MIC and zone diameter results. Version 5.3,

July 2019. https://app.box.com/s/cru62wluz4qq64vd5izk41wle9ss172x.

Accessed June 6, 2025.

|

|

34

|

Sader HS, Mendes RE, Kimbrough JH, Kantro

V and Castanheira M: Impact of the recent clinical and laboratory

standards institute breakpoint changes on the antimicrobial

spectrum of aminoglycosides and the activity of plazomicin against

multidrug-resistant and carbapenem-resistant enterobacterales from

United States medical centers. Open Forum Infect Dis.

10(ofad058)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Clinical and Laboratory Standards

Institute (CLSI): M100Ed32. Performance standards for antimicrobial

susceptibility testing. CLSI, Wayne, PA, 2022.

|

|

36

|

Earle W, Bonegio RGB, Smith DB and

Branch-Elliman W: Plazomicin for the treatment of

multidrug-resistant Klebsiella bacteraemia in a patient with

underlying chronic kidney disease and acute renal failure requiring

renal replacement therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 14(e243609)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ramirez MS and Tolmasky ME: Amikacin:

Uses, resistance, and prospects for inhibition. Molecules.

22(2267)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Clark JA and Burgess DS: Plazomicin: A new

aminoglycoside in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. Ther

Adv Infect Dis. 7(2049936120952604)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hikal AF, Zhao S, Foley S and Khan AA: The

newly identified grdA gene confers high-level plazomicin resistance

in Salmonella enterica serovars. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother. 69(e0160624)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Cass R, Kostrub CF, Gotfried M, Rodvold K,

Tack KJ and Bruss J: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled

study to assess the safety, tolerability, plasma pharmacokinetics

and lung penetration of intravenous plazomicin in healthy subjects.

In: Proceedings of the 23rd European Congress of Clinical

Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID). ECCMID, Berlin,

poster 1637, 2013.

|

|

41

|

U.S. Food and Drug Administration and

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Zemdri Approval Letter

Reference ID: 4282864. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver

Spring, MD, USA, 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210303orig1s000lbl.pdf.

Accessed June 6, 2025.

|

|

42

|

Choi T, Seroogy JD, Sanghvi M and Dhuria

SV: 1400 Mass balance, metabolism, and excretion of

(14C)-plazomicin in healthy human subjects. Open Forum Infect Dis.

5 (Suppl 1)(S431)2018.

|

|

43

|

Zemdri (plazomicin) (package insert).

South Achaogen, Inc., San Francisco, CA, 2021. https://zemdri.com/assets/pdf/Prescribing-Information.pdf.

Accessed June 6, 2025).

|

|

44

|

Connolly LE, Riddle V, Cebrik D, Armstrong

ES and Miller LG: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase 2

study of the efficacy and safety of plazomicin compared with

levofloxacin in the treatment of complicated urinary tract

infection and acute pyelonephritis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.

62:e01989–17. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wagenlehner FME, Cloutier DJ, Komirenko

AS, Cebrik DS, Krause KM, Keepers TR, Connolly LE, Miller LG,

Friedland I and Dwyer JP: EPIC Study Group. Once-daily plazomicin

for complicated urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med.

380:729–740. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

McKinnell JA, Dwyer JP, Talbot GH,

Connolly LE, Friedland I, Smith A, Jubb AM, Serio AW, Krause KM and

Daikos GL: CARE Study Group. Plazomicin for infections caused by

carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. N Engl J Med. 380:791–793.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Jospe-Kaufman M, Siomin L and Fridman M:

The relationship between the structure and toxicity of

aminoglycoside antibiotics. Bioorg Med Chem Lett.

30(127218)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Drugs and Lactation Database

(LactMed®) (Internet). National Institute of Child

Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD, 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513053/.

Accessed June 6, 2025.

|

|

49

|

Başaran SN and Öksüz L: Newly developed

antibiotics against multidrug-resistant and carbapenem-resistant

Gram-negative bacteria: Action and resistance mechanisms. Arch

Microbiol. 207(110)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Edson RS and Terrell CL: The

aminoglycosides. Mayo Clin Proc. 74:519–528. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Paul M, Carrara E, Retamar P, Tängdén T,

Bitterman R, Bonomo RA, de Waele J, Daikos GL, Akova M, Harbarth S,

et al: European society of clinical microbiology and infectious

diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused

by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by European

society of intensive care medicine). Clin Microbiol Infect.

28:521–547. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Gilchrist M and Seaton RA: Outpatient

parenteral antimicrobial therapy and antimicrobial stewardship:

Challenges and checklists. J Antimicrob Chemother. 70:965–970.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Choi T, Komirenko AS, Riddle V, Kim A and

Dhuria SV: No effect of plazomicin on the pharmacokinetics of

metformin in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 8:818–826.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Gall J, Choi T, Riddle V, Van Wart S,

Gibbons JA and Seroogy J: A phase 1 study of intravenous plazomicin

in healthy adults to assess potential effects on the QT/QTc

interval, safety, and pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev.

8:1032–1041. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

No authors listed. Plazomicin (Zemdri)-a

new aminoglycoside antibiotic. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 60:180–182.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Althobaiti H, Seoane-Vazquez E, Brown LM,

Fleming ML and Rodriguez-Monguio R: Disentangling the cost of

orphan drugs marketed in the United States. Healthcare (Basel).

11(558)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Clancy CJ, Potoski BA, Buehrle D and

Nguyen MH: Estimating the treatment of carbapenem-resistant

Enterobacteriaceae infections in the United States using antibiotic

prescription data. Open Forum Infect Dis. 6(ofz344)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Hawkey PM, Warren RE, Livermore DM,

McNulty CAM, Enoch DA, Otter JA and Wilson APR: Treatment of

infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria:

report of the British society for antimicrobial

chemotherapy/healthcare infection society/British infection

association joint working party. J Antimicrob Chemother. 73 (Suppl

3):iii2–iii78. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Theuretzbacher U and Paul M: Developing a

new antibiotic for extensively drug-resistant pathogens: The case

of plazomicin. Clin Microbiol Infect. 24:1231–1233. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

United States Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC 2019). Achaogen 10K fiscal year 2018. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1301501/000156459019010412/akao-10k_20181231.htm.

Accessed September 05, 2025.

|

|

61

|

Wagenlehner F, Caballero VR, Maheshwari V,

Biswas A, Saini P, Quevedo J, Polifka J, Ruiz L and Cure S:

Efficacy of treatment options for complicated urinary tract

infections including acute pyelonephritis: A systematic literature

review and network meta-analysis. J Comp Eff Res.

14(e240214)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Leibovici L, Vidal L and Paul M:

Aminoglycoside drugs in clinical practice: An evidence-based

approach. J Antimicrob Chemother. 63:246–251. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Abd El-Aziz Gadallah M, El-Sayed WM,

Hussien MZ, Elheniedy MA and Maxwell SY: In-vitro activity of

plazomicin, meropenem-vaborbactam, and omadacycline against

carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative isolates in Egypt. J Chemother.

13:205–218. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Thabit AK, Fatani DF, Bamakhrama MS,

Barnawi OA, Basudan LO and Alhejaili SF: Antibiotic penetration

into bone and joints: An updated review. Int J Infect Dis.

81:128–136. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Hubler CM,

Mendes RE, Serio AW, Krause KM and Flamm RK: Activity of plazomicin

against Enterobacteriaceae isolates collected in the United States

including isolates carrying aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes

detected by whole genome sequencing. Open Forum Infect Dis. 4

(Suppl 1)(S377)2017.

|

|

66

|

Mougakou E, Mastrogianni E, Kyziroglou M

and Tziomalos K: The role of novel antibiotics in the management of

diabetic foot infection. Diabetes Ther. 14:251–263. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Ray S, Flemming LK, Scudder CJ, Ly MA,

Porterfield HS, Smith RD, Clark AE, Johnson JK and Das S:

Comparative phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial susceptibility

surveillance in Achromobacter spp. through whole genome

sequencing. Microbiol Spectr. 13(e0252724)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|