Introduction

Calcifying fibrous tumour (CFT) is a very rare,

non-cancerous lesion that can develop in various body parts

(1). Its key microscopic features

are spindle-shaped cells, collagen, chronic inflammation and

distinctive dystrophic calcification (2). Despite its benign nature, CFT can

grow in an invasive manner and appear as a poorly defined mass on

scans. This makes it difficult to tell apart from other tumours,

often leading to misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment.

Diagnosing CFT is challenging for two main reasons.

First, on imaging like CT scans, it typically shows a mass with

coarse calcifications. On MRI, it often appears dark on both T1-

and T2-weighted images due to its fibrous content (3,4).

However, these features are not unique and overlap with other

conditions, including cancers. Second, even a tissue biopsy can be

misleading if it doesn't sample the characteristic calcified areas,

potentially leading to a misdiagnosis of a more aggressive

tumour.

Due to its rarity, reported cases of CFT are limited

worldwide. While they have been found in numerous locations, this

report presents, to the best of our knowledge, the first documented

case of a CFT located in the diaphragm of a living patient.

Previous reports of diaphragmatic involvement have been

exceptionally scarce and just identified post-mortem (5).

This unique case describes the patient's journey,

from clinical presentation and imaging to pathological findings,

treatment and outcome. By detailing this process and comparing it

with existing literature, we aim to improve the recognition of this

rare tumour and help guide its diagnosis and management, ultimately

preventing overtreatment.

Case report

A 45-year-old immunocompetent female patient

presented with a pulmonary nodule that was incidentally detected

during routine health screening 2 months prior to admission (the

examination was conducted in an external hospital and no report

could be retrieved). The asymptomatic patient denied any

respiratory symptoms, including cough, sputum production,

haemoptysis, dyspnoea or systemic manifestations, such as fever,

night sweats or weight loss. Initial surveillance over a two-month

period at a referring institution demonstrated that the left lower

lobe nodule slightly increased in size from 1.6 to 1.7 cm in

maximal diameter on serial computed tomography (CT) imaging

(baseline images unavailable for comparison). No therapeutic

interventions were initiated during the observation period. For

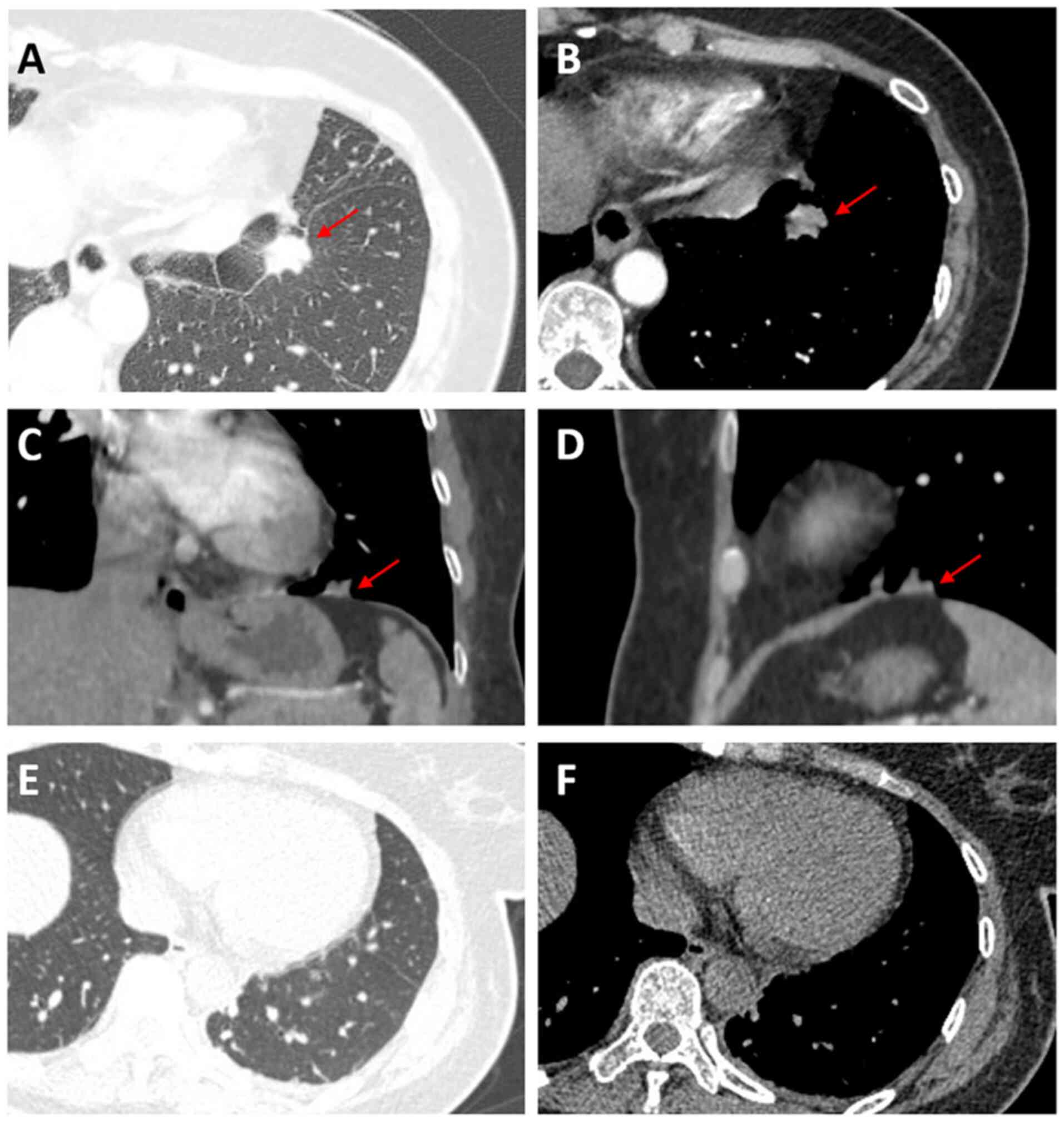

further evaluation, contrast-enhanced chest CT was performed in

July 2024, at the outpatient clinic of Taihe Hospital (Shiyan,

China) and revealed a well-circumscribed solid pulmonary nodule

(1.7x1.3 cm) in the anteromedial basal segment of the left lower

lobe with focal pleural thickening and retraction (Fig. 1A and B). Physical examination was within normal

ranges. It revealed a body temperature of 36.6˚C (normal range,

36.0-37.2˚C), a pulse of 90 bpm (normal range, 60-100 bpm), a

respiratory rate of 20 bpm (normal range, 12-20 breaths/min), a

blood pressure of 122/87 mmHg (normal range, systolic 120-129 mmHg

and diastolic 80-84 mmHg), a pulse oxygen saturation of 98% (normal

range, ≥95%, without oxygen supplementation), clear breath sounds

in both lungs, no dry or wet rales and no positive physical signs

of other systems such as heart, abdomen, etc. Laboratory tests

after admission revealed a white blood cell count of

5.66x109/l (normal range, 4-10x109/l), a red

blood cell count of 5.54x10¹²/l (normal range, 4.3-5.8x10¹²/l), a

haemoglobin concentration of 109 g/l (normal range, 130-175 g/l)

and a platelet count of 209x109/l (normal range,

125-350x109/l). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate, IL-6

level, procalcitonin level, cardiac troponin I level, N-terminal

pro-brain natriuretic peptide level, coagulation profile, liver

function, renal function, electrolytes and thyroid function were

all within normal ranges, and respiratory tumour markers and

tuberculosis IgG antibodies were negative. Pulmonary function

tests, electrocardiogram, cardiac ultrasound and lower limb venous

ultrasound showed no abnormalities. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy

revealed inflammatory changes in the bronchi without neoplastic

lesions. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid smears revealed no acid-fast

bacilli but a small number of Gram-positive cocci. A CT-guided lung

biopsy planned for two days after admission was cancelled due to

the high risk associated with the lesion's proximity to the heart.

A multidisciplinary consultation on four days after admission

concluded that compared to two months ago, the pulmonary nodule had

increased in size and exhibited imaging features such as

lobulation, fine spiculation and pleural retraction (Fig. 1A and B). Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction

(Fig. 1C and D) demonstrated extensive connectivity

between the lesion base and the diaphragm, raising suspicion of

malignancy. Owing to the high risk of CT-guided percutaneous

fine-needle aspiration biopsy, surgical biopsy was recommended.

Preoperative evaluations, including non-contrast brain CT, adrenal

ultrasound, carotid ultrasound and coronary CT angiography,

revealed no abnormalities; abdominal ultrasound showed gallbladder

wall thickening. On the eighth day after admission, the patient was

administered a prophylactic antibiotic regimen of intravenous

cefradine (1 g, BID) at a rate of 40 drops per minute for two days

to prevent postoperative infection. On the subsequent day,

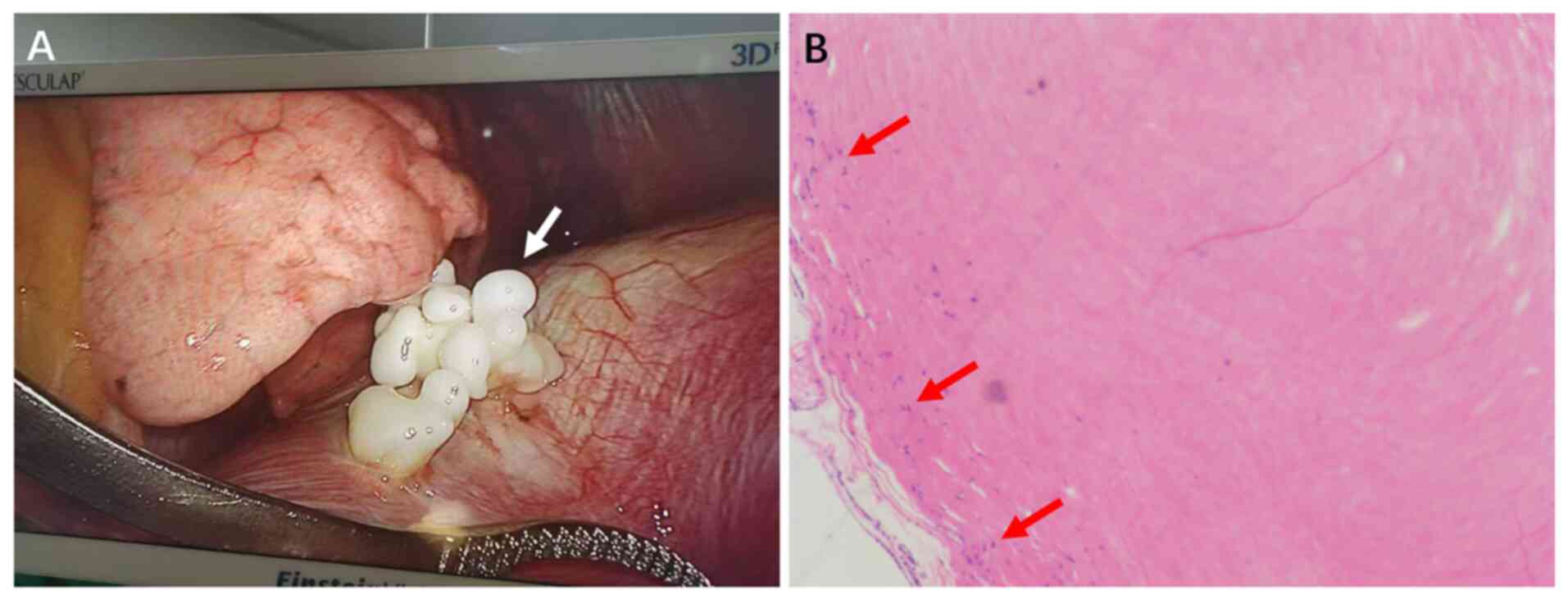

video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was performed. Intraoperative

findings included multiple white, firm, coral-like nodules observed

on the diaphragmatic pleural surface without pleural effusion or

adhesions. The largest nodule was approximately 2 cm (Fig. 2A). Biopsy samples were fixed in 10%

neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for 4-6 h, dehydrated

using an increasing alcohol series, embedded in paraffin and

sectioned into 3-µm slices. Haematoxylin and eosin staining was

performed at room temperature for 40 min and sections imaged using

a CX31 light microscope (Olympus Corp.). Pathological examination

(Fig. 2B) of the diaphragmatic

nodule revealed fibrous tissue hyperplasia with hyaline

degeneration. Biopsy samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered

formalin at room temperature for 4-6 h, dehydrated using an

increasing alcohol series, embedded in paraffin and sectioned into

3-µm slices. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed at room

temperature for 40 min and sections were imaged using a CX31 light

microscope (Olympus Corp.).

Postoperative chest CT performed one day

postoperatively revealed postresection changes in the left

diaphragm (Fig. 1E and F). Attempted supplemental

immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies on the specimen from the first

surgery were non-diagnostic due to tissue detachment artefacts. The

patient was discharged on the second day after surgery, and the

patient underwent two serial follow-up CT scans of the chest

performed at six-month intervals, both of which demonstrated no

evidence of recurrence. Subsequent follow-up with annual CT

surveillance is planned.

Literature review

Only PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) was used for the

literature search and 200 case reports (199 in English and 1 in

French) published between 1946 and 2024 were manually searched,

using ‘calcifying fibrous tumour’ and ‘calcifying fibrous

pseudotumour’ as search terms. Multiple reports have reported more

than one patient, resulting in a total of 215 cases being included.

In the search process, review articles that only conducted

retrospective analyses and duplicate reports were excluded, and

only the first published cases with sufficient case descriptions

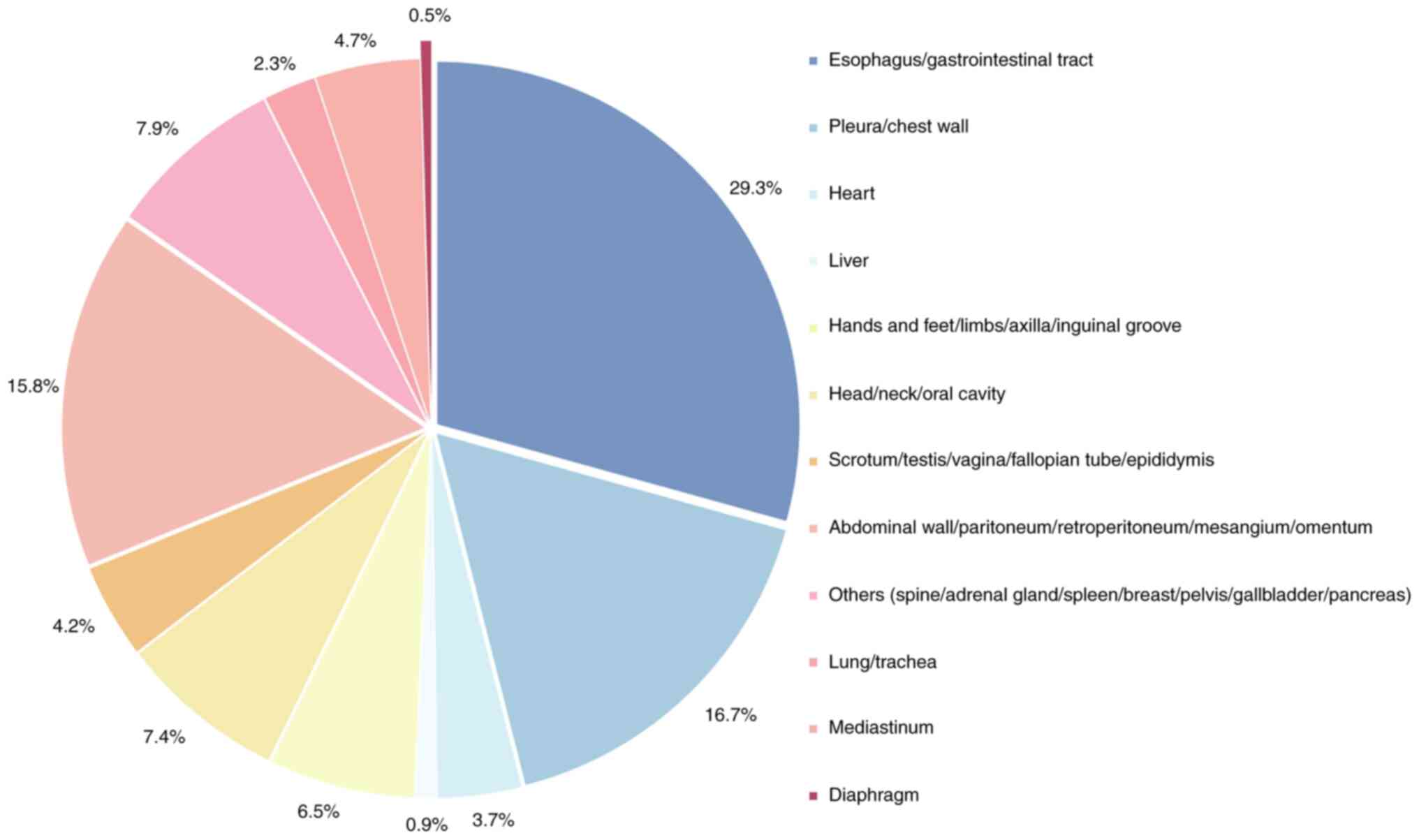

were included for analysis (Fig.

3). CFT can arise in multiple anatomical sites, most frequently

the gastrointestinal tract and pleura, and less commonly the liver

or reproductive tract. According to statistical data, only one case

of a solitary CFT localized to the diaphragm has been documented,

highlighting its exceptional rarity in clinical practice. For

statistical purposes, only the most characteristic disease location

was recorded in instances of multifocal involvement (excluding the

current case). To better characterize chest calcifying fibrous

tumour (CFT), seven published cases with the closest clinical

association were analysed to enable comparison (Table I) (6-9).

Regarding chest CFT, most patients present with ipsilateral chest

pain or are incidentally diagnosed. Chest CT typically shows

nodules with punctate enhancement at the margins, and the nodules

generally appear as milky-white, lobulated solid masses. These

features are highly consistent with those observed in the present

case. However, unlike most chest CFTs, pathological examination in

this case revealed fibrous tissue and inflammatory cell

infiltration but no typical calcified bodies. Literature review

revealed only one previously reported case of primary diaphragmatic

CFT, which was incidentally discovered during autopsy following

traumatic death (5). To the best

of our knowledge, the current study presents the first documented

case of primary diaphragmatic CFT successfully managed with

complete surgical resection (R0). Notably, the morphological

characteristics of the gross specimen of the present case are

highly consistent with those of CFT reported by Mylapalli et

al (5) and Kashizaki et

al (10,11), suggesting that the appearance of

this characteristic gross specimen may become an important basis

for the diagnosis of CFT.

| Table ISummary of the characteristics of

seven previously reported cases of calcifying fibrous tumours that

are most similar to the present case. |

Table I

Summary of the characteristics of

seven previously reported cases of calcifying fibrous tumours that

are most similar to the present case.

| Author/year | Age, years/sex | Symptoms | Location | Chest CT/X-ray | Gross appearance | Pathological

features | Therapy | Prognosis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pinkard et al,

1996 | 23, F | Chest pain | Pleural | Multiple

pleural-based masses with central areas of increased

attenuation | Well-demarcated,

unencapsulated, lobulated masses; 1.5-12.5 cm | The calcifications

had a laminated appearance typical of psammoma bodies | Surgical

excision | NED | (9) |

| Pinkard et al,

1996 | 28, F | Incidental

finding | Pleural | Heterogeneous

extra-parenchymal pleural-based mass; central area of increased

attenuation | Smooth, lobulated

firm, whorled mass; 6.5 and 1.2 cm in maximum diameter | The calcifications

had a laminated appearance typical of psammoma bodies | Surgical

excision | NED | (9) |

| Pinkard et al,

1996 | 34, M | Chest pain | Pleural | Heterogeneous

extra-parenchymal pleural-based mass in left anteroinferior

cardio-phrenic angle; central area of increased attenuation | Attached by a short

pedicle to parietal pleura; 4.0 cm | The calcifications

had a laminated appearance typical of psammoma bodies | Surgical

excision | NA | (9) |

| Mylapalli et

al, 2024 | 48, M | Incidental

finding | Diaphragm | NA | Nodule-papillary

pearly white coral-like outgrowth; 2.0 cm in maximum diameter | Dense hyalinized

fibrocollagenous bundles with perivascular foci of scanty

lymphoplas-macytic infiltration | NA | NA | (5) |

| Mito et al,

2005 | 54, M | Incidental

finding | Pleural | Several nodular

lesions, no calcifications were detected | Solid, white, fibrous

matrix; 1.0x1.5x0.8 cm, 0.5x0.5x0.5 cm | Bland spindle cells,

scant lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and small calcification | Surgical

excision | NED | (8) |

| Jang et al,

2004 | 31, F | Incidental

finding | Pleural | Well demarcated

calcifying mass | Smooth and lobulated;

8x7x5 cm | Psammomatous

calcifi-cations and areas of inflammatory infiltrate | Surgical

excision | NED | (7) |

| Jia et al,

2021 | 38, M | Chest pain | Pleural | Subpleural mass

with dystrophic calcification | Firm, pearly white

masses; 5.0 cm in maximum diameter | Inflammatory

lymphocytic infiltration, minute psammomatous calcifications | Incomplete

resection | NA | (6) |

| Guo et al,

2025 | 45, F | Incidental

finding | Diaphragm | Lobulated solid

nodule | Pearl-white,

lobulated mass with coral-like nodularity | Hyalinized collagen

bundles with sparse lymphocytic infiltration | Surgical

excision | NED | Present case |

Discussion

CFT represents a rare benign fibroblastic

proliferation (12,13); it was initially described by

Rosenthal and Abdul-Karim (13)

1988 as a ‘calcifying fibrous tumour of childhood’ on the basis of

paediatric cases. A subsequent clinicopathological analysis of 10

cases by Fetsch et al (14)

in 1993 led to the revised nomenclature ‘calcifying fibrous

pseudotumor’. In 2013, the World Health Organization Classification

of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone formally defined CFT as a rare

benign fibroblastic disorder (15).

According to earlier literature, the predilection

sites of CFT were predominantly concentrated in soft tissues of the

extremities, trunk and head/neck regions. However, with an

increasing number of case reports, it is now evident that CFT can

arise in virtually any anatomical location (12). The most frequent sites include the

gastrointestinal tract, pleura, peritoneum and mesentery, which

aligns with the trends summarized in the present study. A

literature review by Chorti et al (1) reported a broad age range for CFT

onset (1-85 years), with a slight female predominance.

CFT typically lacks distinctive clinical symptoms.

However, when critical organs such as the lungs, spleen or pancreas

are involved, it may not only induce compressive symptoms but also

lead to functional impairments of the affected organs (16).

On CT images, thoracic CFT typically manifests as

well-circumscribed solitary masses or multiple solid soft-tissue

lesions. The lesions demonstrate either broad-based sessile

attachment or pedunculated growth to the chest wall, exhibiting

characteristic punctate to amorphous calcifications with a

predominantly peripheral distribution (3,4).

Enhanced CT revealed mild heterogeneous enhancement with preserved

homogeneity of the non-enhancing tumour parenchyma and no

radiologic evidence of peritumoral infiltration (3,17).

Magnetic resonance imaging findings of CFT lack

specificity, generally presenting as masses with isointensity on

T1-weighted (T1W) sequences and hypointensity on T2W sequences,

with calcified regions showing marked signal voids. However, few

reports describe CFT cases lacking detectable calcifications,

suggesting potential heterogeneity in imaging manifestations

(18). When CFT involves the

diaphragm or pleura, tumour margins are frequently obscured by

adhesions and traction to adjacent pleural tissues, posing

challenges for radiological diagnosis and surgical planning. In the

present case, 3D reconstruction was utilized to improve the

anatomical assessment of tumour-adjacent tissue relationships. 3D

imaging demonstrated extensive connectivity between the tumour base

and the diaphragm, offering vital anatomical guidance for precise

intraoperative resection. However, since this technology increases

costs without proven prognostic benefits, it should remain a

selective rather than standard preoperative tool.

CFT demonstrates distinct histopathological

features: Solid, firm, lobulated masses with well-defined margins;

smooth surfaces lacking encapsulation; and homogeneous grey-white

fibrous cut surfaces devoid of haemorrhage or necrosis (17,19).

Microscopically, spindle cells embedded in abundant collagenous

stroma are characteristic and accompanied by dystrophic

calcifications or psammoma bodies, with scattered lymphoplasmacytic

infiltrates in the interstitium (1,2). IHC

aids in differential diagnosis. Reported IHC profiles show diffuse

positivity for vimentin and focal CD34 expression in spindle cells,

whereas desmin, S-100 protein, STAT6 and anaplastic lymphoma kinase

(ALK) are typically negative (7,20).

In the current case, the gross specimen presented as white, hard,

coral-like nodules. Microscopic examination revealed prominent

fibrosis and scattered lymphocytes, although typical calcified

nodules were absent, which is potentially attributable to sampling

limitations in pathological sectioning or indication of early

disease progression. Despite technical challenges (such as the

tissue detachment in paraffin sections compromising IHC

interpretability), the diagnosis of CFT was confirmed through an

integrative analysis of morphological, pathological and

radiological features, consistent with the diagnostic frameworks

established by Mylapalli et al (5) and Kashizaki et al (5,10).

CFT generally has a favourable prognosis and the

literature seldom emphasizes the necessity of differentiating it

from malignant neoplasms. However, in the present case, the

thoracic CFT presented on axial CT as a solid nodule with

spiculated margins, lobulation and suspected pleural retraction.

Compared with prior imaging, the lesion demonstrated slight

interval growth, sharing overlapping radiological features with

those of primary pulmonary malignancies. Thus, distinguishing

thoracic CFT, particularly subpleural lesions, from primary lung

malignancies is imperative in imaging interpretation.

Beyond primary lung cancer, CFT must be

differentiated from the following thoracic fibrous tumours: i)

Solitary fibrous tumour (SFT), typically arising from the pleura,

appears on CT as a solitary, well-demarcated, hypervascular

soft-tissue mass with homogeneous density. Larger SFTs may exhibit

hypodense or heterogeneous areas because of necrosis or

haemorrhage, facilitating differentiation from CFT. On IHC, STAT6

expression serves as the most specific and sensitive diagnostic

marker for SFT (21), whereas CFT

is STAT6-negative. ii) Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT):

IMT often manifests on thoracic CT as a solitary, well-defined

lobulated mass, predominantly in the lower lung lobes, mimicking

CFT. However, IMT typically displays heterogeneous attenuation and

enhancement, with frequent ALK positivity on IHC, a feature rarely

observed in CFT (22,23). iii) Desmoid tumours: Desmoid

tumours on CT usually present as round or oval dense shadows with

minimal enhancement. Key discriminators include their infiltrative

growth pattern, ill-defined margins and high postoperative

recurrence rates. Definitive diagnosis relies on β-catenin

positivity via IHC (24).

With respect to management, individualized treatment

decisions are made on the basis of clinical evaluation. Given the

indolent growth of CFT and its potential for local compressive

effects, surgical resection is recommended for surgically eligible

young patients (clinical judgment) (25). Upon review of prior cases, CFT

demonstrates an unequivocally benign biological behaviour, with low

recurrence rates after complete excision, no evidence of malignant

transformation during long-term follow-up and a 100% survival rate

(1). For asymptomatic patients

with CFT with a high surgical risk (such as advanced age or severe

cardiopulmonary dysfunction), active surveillance rather than

intervention is advised. As reported in the present study, a

45-year-old female patient underwent thoracoscopic resection for a

solitary thoracic mass and was ultimately diagnosed with CFT.

Surveillance over one year has demonstrated no evidence of

recurrence. The present case underscores the clinical importance of

recognizing CFT to avoid misdiagnosis, inappropriate management and

related complications.

The precise aetiology and pathogenesis of CFT remain

elusive. It has been hypothesized that CFT may represent a late

sclerotic phase of IMT (23).

Another study has suggested associations with pathogenic mutations

in the ZN717, FRG1 and CDC27 genes, leading to copy number

variations in chromosomes 6 and 8 and altered coding regions.

However, the underlying mechanisms require further investigation

(6).

In summary, CFT is a benign tumour characterized by

a slow growth tendency and easy misdiagnosis as other pulmonary

nodules. Macroscopically, it typically presents as a white, firm,

coral-like nodule. Radiological findings reveal a

well-circumscribed, homogeneous mass with punctate calcifications.

The identification of characteristic calcified nodules through IHC

analysis serves as the gold standard for definitive diagnosis.

Surgical resection represents the primary intervention and is

associated with a favourable prognosis and a low rate of

recurrence. Despite its rarity, CFT warrants consideration in the

routine evaluation of pulmonary nodules because of its distinct

clinical implications. As a benign neoplasm with indolent

progression, CFT is frequently misclassified as granulomatous

inflammation or malignancy on initial assessment, a diagnostic

pitfall that may lead to overtreatment and substantial patient

distress. Therefore, more evidence from accumulating case reports

could aid in refining diagnostic and treatment approaches. When

thoracic CT reveals homogeneous nodules with peripheral punctate or

amorphous calcifications, CFT should be suspected. Through

comprehensive case analyses and a literature review, the present

study aimed to enhance the understanding of CFT and promote

diagnostic and therapeutic progress, thereby facilitating accurate

identification and more appropriate clinical management for these

patients. Since the present literature search only used PubMed, it

is expected that future studies will provide reviews with more

complete evidence in this area.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by the Innovation Development

Joint Fund of Hubei Provincial Science Foundation (grant no.

2025AFD181).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SG conceptualized the study and wrote the original

manuscript. LY, GC and YT searched the literature and obtained

case-related data. CX and WH analysed the data and relevant

literature. MW and HW edited the final draft and assisted with

language translation. JG provided surgical specimens. JG and MW

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of

Taihe Hospital (Shiyan, China; approval no. 2025KS127) and was

performed in accordance with the principles of good clinical

practice following the Tri-Council guidelines. Informed consent for

both the study and publication was obtained from the patient.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of case information and images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chorti A, Papavramidis TS and

Michalopoulos A: Calcifying fibrous tumor: Review of 157 patients

reported in international literature. Medicine (Baltimore).

95(e3690)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zhang L, Wei JG, Fang SG, Luo RK, Xu ZG,

Li DJ and Kong LF: Calcifying fibrous tumor: A clinicopathological

analysis of 32 cases. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 49:129–133.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

3

|

Yu C, Wen X and Sun M: CT and MRI features

of calcified fibrous tumor: A case report. Asian J Surg.

48:872–873. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Miyashita S, Ryu Y, Takata H, Asaumi Y,

Sakatoku M, Seike T, Okamura T, Inamura K, Kawai H, Okuno N and

Terahata S: Imaging findings of gastric calcifying fibrous tumour.

Bjr Case Rep. 2(20160064)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Mylapalli JL, Jangir H, Sharma M,

Prabhakar V, Sandhu PR, Subramanian A, Barwad A and Lalwani S:

Post-mortem detection of a calcifying fibrous pseudotumor at a rare

site-a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 67:669–671.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Jia B, Zhao G, Zhang ZF and Sun BS:

Multiple calcifying fibrous tumor of the pleura: A case report.

Thoracic Cancer. 12:2271–2274. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Jang KS, Oh YH, Han HX, Chon SH, Chung WS,

Park CK and Paik SS: Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor of the pleura.

Ann Thorac Surg. 78:e87–e88. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Mito K, Kashima K, Daa T, Kondoh Y, Miura

T, Kawahara K, Nakayama I and Yokoyama S: Multiple calcifying

fibrous tumors of the pleura. Virchows Arch. 446:78–81.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Pinkard NB, Wilson RW, Lawless N, Dodd LG,

McAdams HP, Koss MN and Travis WD: Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor

of pleura. A report of three cases of a newly described entity

involving the pleura. Am J Clin Pathol. 105:189–194.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kashizaki F, Kano T, Kameda Y and Osawa H:

Calcifying fibrous tumors resembling coral. Intern Med.

63:3111–3112. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Takabatake K, Arita T, Kuriu Y, Shimizu H,

Kiuchi J, Takaki W, Konishi H, Yamamoto Y, Morimura R, Shiozaki A,

et al: Calcifying fibrous tumor of the ileum resected by

single-port laparoscopic surgery: A case report. Surg Case Rep.

8(64)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Larson BK and Dhall D: Calcifying fibrous

tumor of the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

139:943–947. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Rosenthal NS and Abdul-Karim FW: Childhood

fibrous tumor with psammoma bodies. Clinicopathologic features in

two cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 112:798–800. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fetsch JF, Montgomery EA and Meis JM:

Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 17:502–508.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink

HK and Harris C: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung,

Pleura, Thymus and Heart. In: International Agency for Research on

Cancer. IARC Press, Lyon, 2007.

|

|

16

|

Abd Kahar NN and Al-Mukhtar A: Calcifying

fibrous tumour-a rare cause of anaemia. J Surg Case Rep.

2021(rjaa573)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Shibata K, Yuki D and Sakata K: Multiple

calcifying fibrous pseudotumors disseminated in the pleura. Ann

Thorac Surg. 85:e3–e5. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lee HJ, Jeong JS and Lee YC: Calcifying

fibrous tumour of the pleura without gross calcification. Respirol

Case Rep. 12(e01365)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Suh JH, Shin OR and Kim YH: Multiple

calcifying fibrous pseudotumor of the pleura. J Thorac Oncol.

3:1356–1358. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lisowska H, Marciniak M, Cianciara J and

Pawełczyk K: A rare case of calcifying fibrous pseudotumor of the

pleura with an accompanying vascular anomaly in the pulmonary

ligament. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 15:59–61. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kazazian K, Demicco EG, de Perrot M,

Strauss D and Swallow CJ: Toward better understanding and

management of solitary fibrous tumor. Surg Oncol Clin N Am.

31:459–483. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, Narla S

and Kolli R: Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics. 23:719–729.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Sigel JE, Smith TA, Reith JD and Goldblum

JR: Immunohistochemical analysis of anaplastic lymphoma kinase

expression in deep soft tissue calcifying fibrous pseudotumor:

Evidence of a late sclerosing stage of inflammatory myofibroblastic

tumor? Ann Diagn Pathol. 5:10–14. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Prendergast K, Kryeziu S and Crago AM: The

evolving management of desmoid fibromatosis. Surg Clin N Am.

102:667–677. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Azam F, Chatterjee M, Kelly S, Pinto M,

Aurangabadkar A, Latif MF and Marshall E: Multifocal calcifying

fibrous tumor at six sites in one patient: A case report. World J

Surg Oncol. 12(235)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|