Introduction

The role of glucagon-like peptide-1

(GLP1)-dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) axis in the pathogenesis of

type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been well documented (1). GLP1, an incretin hormone secreted by

L-cells is released into the circulation in response to nutrients

and glucose, and improves insulin secretion, lowers glucose levels

by binding to GLP1 receptor (GLP1R), prevents glucagon secretion

and helps gastric emptying. By contrast, DPP4 rapidly cleaves GLP1

into an inactive metabolite, which is eliminated from the body

within 1 min; thus limiting the insulinotropic ability of GLP1.

Based on this, multiple drugs targeting GLP1 signaling through its

receptor, GLP1R and DPP4 are currently available for obesity and/or

T2DM treatments (1,2).

Various conditions have been suggested as risk

factors of T2DM; due to increases in weight gain in the population,

obesity and being overweight have been reported to be among the

prominent risk factors of T2DM (3). Several obesity-related genes, such as

CD36 and protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 1

(PTP1N) intersect with GLP1-DPP4 signaling (4-7).

CD36, a fatty acid transporter that is involved in fat metabolism

of adipose tissue (8), is

associated with an increased risk of T2DM (9-11).

In addition, it has previously been reported that human carriers of

CD36 rs3211938 (G/T) exhibit a marked decrease in GLP1

secretion in response to high-fat meals (12); consequently, a hypothetical model

has been proposed in which GLP1 might bind to CD36(5).

PTPN1 inhibition has been shown to increase GLP1

secretion in colonic culture after exposure to inflammatory

stimulation (6) and is

downregulated in skeletal muscle following treatment with a GLP1R

agonist, liraglutide, indicating the interaction of PTPN1 and

GLP1(7). The levels of GLP1 in

obese individuals are comparable to those in healthy weight

individuals; however, the postprandial GLP1 response is attenuated

in overweight and obese individuals (13). Circulating DPP4 is elevated in

insulin-resistant patients despite its unknown tissue origin

(14). Furthermore, levels of

circulating CD36 or expression of CD36 has been reported to be

elevated in overweight/obese individuals and to be associated with

unhealthy fat accumulation (15).

In addition, an animal study demonstrated that

PTPN1-deficient mice are resistant to weight gain (16). Therefore, this evidence suggests

that GLP1R, DPP4, CD36 and PTPN potentially serve a role in obesity

and T2DM pathogenesis.

Recent studies have indicated that GLP1R,

DPP4, CD36 and PTPN1 polymorphisms are associated

with obesity and T2DM. GLP1R rs3765467 and rs761387

polymorphisms are linked to T2DM susceptibility and antidiabetic

drug response, respectively (17,18)

whereas DPP4 rs3788979 and rs7608798 polymorphisms are

associated with T2DM predisposition (19). In addition, CD36 rs1761667

and rs3211867, and PTPN1 rs2206656, rs1570179, rs3787345,

rs754118, rs3215684, rs2282147, rs718049 and 1484insG, -1023(C)

polymorphisms are related to obesity or T2DM risk (20-23).

However, since the genetic link between obesity and T2DM cannot be

explained by the GLP1R-DPP4 axis alone, it is important to

investigate how these four genes jointly contribute to T2DM risk

across different body weight categories. The present systematic

review aimed to explore the associations between four different

diabetes-associated genes (DPP4, GLP1R, PTPN1

and CD36) and T2DM risk among individuals in different body

weight categories.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection

criteria

A search strategy was developed by combining the

terms ‘diabetes mellitus’ and (‘polymorphism’ or ‘genetic

variation’) and (‘DPP4’ or ‘GLP1R’ or ‘CD36’ or ‘PTP1B’ or

‘PTPN1’). Animal studies were excluded as well as other unrelated

publication types, including grey literature. The search was

restricted to English-language articles published online with no

limit to publication date. The search strategy was applied to the

following databases: Academic Search Complete and CINAHL via

EBSCOHost (https://research.ebsco.com/), PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and ProQuest

(https://www.proquest.com/) until March

31, 2024. Following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of

Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023) (24), the search strategy was developed as

broad as the present study aimed for a high sensitivity search.

Subsequently, search findings were exported to

EndNote (version 21; Clarivate), deduplicated and uploaded to

Rayyan systematic review web-based software (25). Two authors independently screened

the titles and abstracts, and assessed the full texts, and data

extraction and quality assessment were performed independently by

four authors, with the extracted data reviewed for completeness by

one author. Any disagreement was solved by discussion among all

authors until a consensus was reached.

The standardized data collection form of the

Cochrane Collaboration Public Health Group (26) was deployed to extract the following

information from each selected study: Authors, publication date and

journal, country, type of study, aims and objectives, sampling

techniques and dates of data collection, sample size, age and sex

of participants, exposures and outcomes, including outcome

measures, key conclusions, limitations and recommendations.

Next, the Q-Genie tool (27) was used to assess the quality of

included studies. Specifically, the tool was applied for genetic

association studies, and was tailored to focus on the specific

methodological aspects crucial for evaluating genetic associations.

The tool consists of the following 11 items: Rationale for study,

selection and definition of outcome of interest, selection and

comparability of comparison groups, technical classification of the

exposure, non-technical classification of the exposure, other

sources of bias, sample size and power, a priori planning of

analyses, statistical methods and control for confounding, testing

of assumption and inferences for genetic analyses, and

appropriateness of inferences drawn from results. Studies with a

Q-Genie score of ≤35 were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Assessment of the risk of bias due to missing

evidence was subsequently performed by following the Risk of Bias

due to Missing Evidence (ROB-ME) framework (28). The results matrix was created to

indicate whether study results were available for inclusion in each

meta-analysis. Symbols were used to indicate inclusion/exclusion,

following the predefined criteria outlined in the key for the

results matrix.

Following the Cochrane handbook for systematic

reviews and the STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association

Studies guidelines to guide the process of planning the

comparisons, preparing for synthesis, undertaking the synthesis and

interpreting and describing the results (29), >2 studies were pooled to perform

a meta-analysis, provided that those two studies could be

meaningfully pooled and that their results were sufficiently

‘similar’.

The present systematic review and meta-analysis were

registered with PROSPERO (2024 CRD42024531067; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024531067)

and were published prior to initiating the search (30).

Data analysis

The odds ratio (OR) was used as the effect size for

each meta-analysis, with corresponding variances calculated for

binary outcomes. A random-effects model was employed to account for

potential heterogeneity between studies, estimating the

between-study variance τ2 using the restricted

maximum-likelihood method (31).

Pooled ORs and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated

to summarize the findings. Most studies included in the present

systematic review used the per-allele genetic model. As such, the

association was assessed by measuring the corresponding OR and 95%

CI retrieved from the per-allele model from each study.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore

variations in risk across different body weight categories, as

reported by each included study (0: Healthy weight; 1: Obese),

aiming to identify potential differences in effect sizes based on

this stratification. To assess potential publication bias, funnel

plots were visually inspected for any evidence of bias, followed by

Egger's test for testing funnel plot asymmetry (32). Sensitivity analyses were also

performed by running leave-one-out analyses for each meta-analysis

(33). Notably, all statistical

tests were two-tailed. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

The meta-analysis was performed using R (version

4.4.1; RStudio, Inc.) and the metafor package (version 4.6-0)

(34). The overall study process

was illustrated in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic

Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 flow chart (35).

Results

Search results

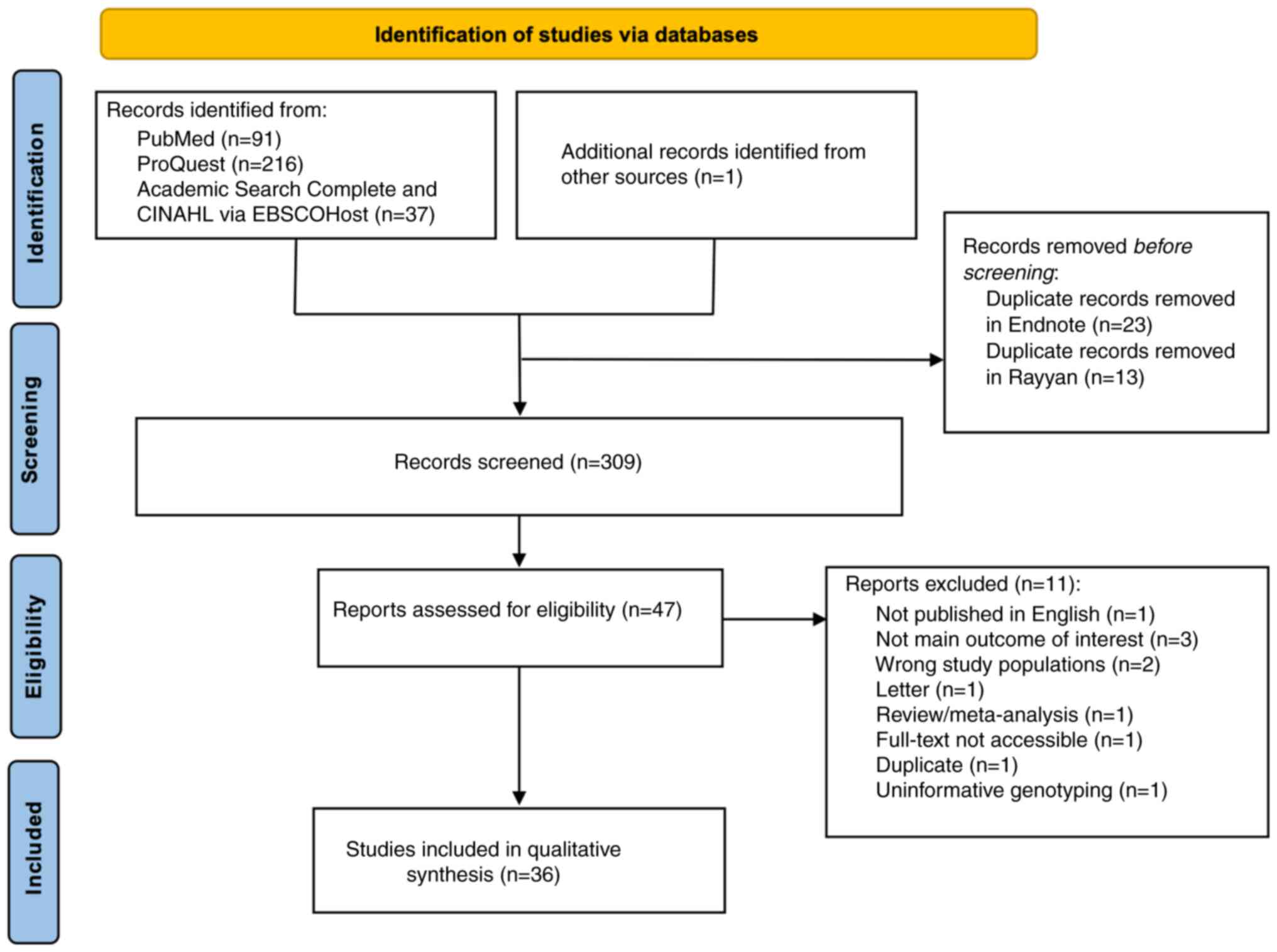

The search retrieved 345 studies, 36 of which were

duplicates. Of the 309 unique records, 262 were excluded during the

title and/or abstract screening. At the full-text review stage, 11

were excluded for reasons outlined in the PRISMA flow chart

(Fig. 1). The final numbers

included 36 relevant studies (Table

I).

| Table IMain characteristics of the included

studies and quality assessment. |

Table I

Main characteristics of the included

studies and quality assessment.

| | | Case group | Control group | |

|---|

| First author,

year | Country | N | Mean age,

years | Sex proportion,

% | N | Mean age,

years | Sex proportion,

% | Study design | Gene of

interest | Q-Genie quality

score | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ahmed et al,

2016 | Malaysia | 314 | 51.25 | M: 46.5 F:

53.5 | 235 | 50.03 | M: 39.0 F:

61.0 | Case-control | DPP4 | 37 | (36) |

| Alves et al,

2022 | Brazil | 172 | 74.80 | M: 32.6 F:

67.4 | 628 | 73.80 | M: 33.0 F:

67.0 | Case-control | DPP4 | 35 | (37) |

| Bento et al,

2004 | USA | Total: 575 T2DM +

ESRD: 300 T2DM: 275 | T2DM + ESRD: 46.50

T2DM: 50.90 | N/A | 510 | 50.90 | N/A | Case-control | PTPN1 | 38 | (22) |

| Bhargave et

al, 2022 | India | 100 | 49.33±12.02 | M: 54.0 F:

46.0 | 100 | 48.84±13.10 | M: 53.0 F:

47.0 | Case-control | DPP4 | 36 | (19) |

| Bodhini et

al, 2011 | India | 262 | 49.00 | N/A | 249 | 46.00 | N/A | Case-control | PTPN1 | 26 | (39) |

| Cheyssac et

al, 2006 | France | Total: 2,531 T2DM

(first group): 325 T2DM (second group):902 Moderately obese: 616

Severely obese: 688 | T2DM (first group):

61.83 T2DM (second group): 62.55 Moderately obese: 50.11 Severely

obese: 46.03 | T2DM (first group)

M: 53.8 F: 46.2 T2DM (second group) M: 57.4 F: 42.6 Moderately

obese M: 44.6 F: 55.4 Severely obese M: 23.9 F: 76.1 | Total 1,047 Control

(first group) 311 Control (second group) 736 | Control (first

group) 62.99 Control (second group) 53.47 | Control (first

group) M: 39.5 F:60.5 Control second group) M: 39.8 F: 60.2 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 45 | (60) |

| Corpeleijn et

al, 2006 | The

Netherlands | Total: 367 IGT: 216

T2DM: 151 | IGT: 57.90 T2DM:

60.30 | IGT M: 52.0 F: 48.0

T2DM M: 66.0 F: 34.0 | 308 | 58.10 | M: 61.0 F:

39.0 | Case-control | CD36 | 37 | (40) |

| Echwald et

al, 2002 | Denmark | 527 | 60.00 | M: 58.0 F:

42.0 | 542 | 56.00 | M: 49.0 F:

51.0 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 39 | (41) |

| Fang et al,

2023 | China | Total: 286 T2DM

EOD: 137 T2DM LOD: 179 | T2DM EOD: 46.90

T2DM LOD: 60.30 | T2DM EOD M: 62.1.0

F: 37.9.0 T2DM LOD M: 40.8 F: 59.2 | 145 | 53.10 | M: 40.0 F:

60.0 | Case-control | GLP1R | 36 | (17) |

| Florez et

al, 2005 | Multiple countries

(USA, Sweden, Scandinavian countries, Canada, Poland) | Total case-control

samples: 7,883 Total case samples: 6,694 Scandinavian countries,

case samples: 942 Sweden, total case-control samples: 1,028 Canada,

total case-control samples: 254 USA, total case-control samples:

2,452 Poland, total case-control samples: 2,018 | N/A | N/A | Scandinavian

countries: 1,189 | N/A | N/A | Case-control | PTPN1 | 51 | (42) |

| Gautam et

al, 2015 | India | 450 | N/A | N/A | 400 | N/A | N/A | Case-control | CD36 | 23 | (43) |

| Gautam et

al, 2013 | India | 100 | 53.74 | N/A | 100 | 48.12 | N/A | Case-control | CD36 | 29 | (44) |

| Gautam et

al, 2011 | India | 300 | 48.61 | M: 57.7 F:

42.3 | 100 | 42.88 | N/A | Case-control | CD36 | 25 | (45) |

| Gouni-Berthold | Germany | 402 | 63.10 | M: 57.5 F:

42.5 | 434 | 64.40 | M: 57.1 F:

42.9 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 39 | (46) |

| Hatmal et

al, 2021 et al, 2005 | Jordan | 177 | 57.33 | M: 53.1 F:

46.9 | 173 | 50.81 | M: 46.8 F:

53.2 | Case-control | CD36 | 38 | (47) |

| Kwak et al,

2018 | South Korea | Stage 1: 619 Stage

2: 2,013 Stage 3: 5,218 | Stage 1: 56.40

Stage 2: 58.40 Stage 3: N/A | Stage 1 M: 46.4 F:

53.6 Stage 2 M: 46.3 F: 53.7 Stage 3: N/A | Stage 1 298 Stage 2

1,013 Stage 3 7, 904 | Stage 1 66.90 Stage

2 65.50 Stage 3: N/A | Stage 1 M: 44.6 F:

55.4 Stage 2 M: 50.8 F: 49.2 Stage 3: N/A | Case-control | GLP1R | 43 | (48) |

| Leprêtre et

al, 2004 | France | 96 Additional

subsequent genotyping in 1,132 unrelated French subjects. | N/A | N/A | 96 | N/A | N/A | Case-control | CD36 | 27 | (51) |

| Malodobra et

al, 2011 | Poland | 130 | 55.00 | M: 52.3 F:

47.7 | 98 | 50.00 | M: 39.8 F:

60.2 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 27 | (49) |

| Malodobra-Mazur

et al, 2007 | Poland | 48 | 57.70 | M: 100.0 F:

0.0 | 50 | 49.50 | M: 100.0 F:

0.0 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 22 | (50) |

| Martín-Márquez

et al, 2020 | Mexico | 57 | 47.70 | M: 32.3 F:

67.7 | 58 | 42.08 | M: 30.2 F:

69.8 | Case-control | CD36 | 35 | (52) |

| Meshkani et

al, 2007 | Iran | 174 | 55.10 | M: 44.8 F:

55.2 | 412 | 40.35 | M: 54.9 F:

45.1 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 35 | (23) |

| Meshkani et

al, 2007 | Iran | 286 | 55.80 | M: 46.5 F:

53.5 | 412 | 40.40 | M: 46.5 F:

53.5 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 48 | (62) |

| Meyre et al,

2019 | France | 184 | 63.50 | M: 66.8 F:

33.2 | FREX 566 GnomAD

31,413 Global European 77,061 | N/A | N/A | Case-control | CD36 | 23 | (56) |

| Mok et al,

2001 | Canada | Total: 354 IGT or

T2DM: 177 IGT: 70 T2DM: 107 | IGT: 39.00 T2DM:

45.20 | IGT M: 18.6 F: 81.4

T2DM M: 40.2 F: 59.8 | 476 | 25.70 | M: 45.8 F:

54.2 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 22 | (53) |

| Nishiya et

al, 2020 | Japan | 1,560 | 53.30 | M: 37.6 F:

62.4 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Cross-sectional | GLP1R | 40 | (64) |

| Rać et al,

2012 | Poland | 90 | N/A | M: 73.3 F:

47.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Cross-sectional | CD36 | 31 | (65) |

| Santaniemi et

al, 2004 | Finland | 257 | 58.16 | M: 52.1 F:

47.9 | 258 | 55.69 | N/A | Case-control | PTPN1 | 44 | (54) |

| Shukla et

al, 2024 | India | Total: 325

T2DM+obese: 75 T2DM: 250 | T2DM + obese: 48.27

T2DM: 48.21 | N/A | 150 | 46.11 | N/A | Case-control | CD36 | 36 | (20) |

| Tokuyama et

al, 2004 | Japan | 791 | 61.50 | M: 68.1 F:

31.9 | 318 | 68.80 | M: 45.6 F:

54.4 | Case-control | GLP1R | 40 | (57) |

| Touré et al,

2022 | Senegal | 100 | Obese: 50.50 Obese

+ T2DM: 51.06 | M: 0.0 F:

100.0 | 50 | 49.98 | M: 0.0 F:

100.0 | Case-control | CD36 | 44 | (21) |

| Touré et al,

2022 | Senegal | 50 | 50.80 | M: 0.0 F:

100.0 | 50 | 49.98 | M: 0.0 F:

100.0 | Case-control | CD36 | 44 | (61) |

| Traurig et

al, 2007 | India | 573 | 44.70 | M: 35.6 F:

64.4 | 464 | 31.40 | M: 56.5 F:

43.5 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 44 | (55) |

| Wang et al,

2012 | China | Total: 581 IGT/IFG:

468 T2DM: 113 | IGT/IFG: 55.70

T2DM: 59.50 | IGT/IFG M: 60.3 F:

39.7 T2DM M: 60.2 F: 39.8 | 676 | 53.20 | M: 59.5 F:

40.5 | Case-control | CD36 | 45 | (58) |

| Wanic et al,

2007 | Poland | 474 | 58.00 | M: 48.0 F:

52.0 | 411 | 49.00 | M: 35.0 F:

65.0 | Case-control | PTPN1 | 49 | (38) |

| Wessel et

al, 2015 | Multiple countries

(USA, Iceland, China, Switzerland, Germany, Netherlands, UK,

Sweden, Scotland, Greece, Denmark, Italy, Australia, Canada) | 81,877 | N/A | N/A | 16,491 | N/A | N/A | Cohort | GLP1R | 49 | (63) |

| Zhang et al,

2018 | China | 546 | 53.50 | M: 35.7 F:

64.3 | 546 | 53.00 | M: 35.7 F:

64.3 | Case-control | CD36 | 41 | (59) |

Study characteristic

Most studies utilized longitudinal data (Table I); most were case-control studies

(n=33) (17,19-23,36-62),

one was a cohort study (63) and

two studies were performed with a cross-sectional study design

(64,65). All studies employed non-T2DM

individuals as a control group.

Five studies reported GLP1R polymorphisms

(17,48,57,63,64),

three reported DPP4 polymorphisms (19,36,37),

14 studies reported PTPN1 polymorphisms (22,23,38,39,41,42,46,49,50,53-55,60)

and 14 studies reported CD36 polymorphisms (20,21,40,43-45,47,51,52,56,58,59,61,65).

The genotyping methods used in the studies were predominantly

polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) (29 studies), using either

multiplex quantitative PCR (17,21,36,37,49,50,55,57,59,61)

or conventional PCR combined with restriction fragment length

polymorphism analysis (19,20,23,39-41,43-46,52,54,62).

One study used an exome-based genotyping array (48), six studies used Sanger sequencing

(47,51,53,56,62,63),

three studies used chip-based matrix-assisted laser

desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry or MassARRAY

Sequenom (22,42,58),

one study used Japonica Array based genotyping (64), an improved genotype imputation

designed for the Japanese population, one study used fluorescence

polarization based-single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection

(38), and one study used exome

array and whole exome sequencing (63). All studies reported <5%

genotyping error and observed allele frequencies were in agreement

with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Table II presents a comprehensive

overview of the SNPs analyzed across the four genes in the

systematic review. Three studies reported 11 DPP4

polymorphisms and their association with T2DM, only one DPP4

rs7608798 polymorphism was reported by two studies (19,36).

However, neither of these studies used the per-allele genetic

model, and thereby, meta-analysis was not performed for

DPP4. Furthermore, six GLP1R polymorphisms and their

associations with T2DM were reported by five studies (17,48,57,63,64);

however, only one GLP1R (rs3765467) polymorphism was

reported by two studies (17,48).

Each study contained two or more data sets and used the per-allele

genetic model, and were eventually included in a meta-analysis.

| Table IISummary of the SNPs studied across

four genes in all included studies. |

Table II

Summary of the SNPs studied across

four genes in all included studies.

| Gene | SNPs (Refs.) |

|---|

| DPP4 | rs7608798 (19,36);

rs1014444(36);

rs12617656(36);

rs7633162(36); rs4664443(36); rs2160927(36); rs17574(36); rs1861978(36); rs1558957(36); rs2268894(37); rs6741949(37) |

| GLP1R | rs3765467 (17,48,64);

Pro7Leu (57); Arg44His (57); Thr149Met (57); Leu260Phe (57); rs10305492(63) |

| PTPN1 | rs2904268 (22,55);

rs803742 (22,55); rs1967439 (22,55);

rs718630 (22,55); rs4811078 (22,55);

rs2206656 (22,55); rs932420 (22,55);

rs93240(22); rs3787335 (22,55,60);

rs2426158 (22,55); rs2904269 (22,55);

rs941798 (22,39,42,60);

rs1570179 (22,39,60);

rs3787345 (22,38,39,55,60);

rs1885177 (22,55); rs754118 (22,38,60);

rs3215684 (22,42,55);

rs968701 (22,42,55);

rs2282147 (22,38,39,42);

rs718049 (22,39); rs718050 (22,38,39,42,55,60);

rs3787348 (22,38,42,55);

rs914458 (22,60); rs2230604(39); rs16989673 (1484insG) (22,39,49,50,55,62);

7077G/C (60); rs6020563(60); rs2426157(60); rs6126033(60); rs2426159(60); rs6020608(60); rs2282146(60); rs17847901(50); 51 del A (23); 451A>G (23); 467T>C (23); rs6126029 (1023C>A) (23); 1045G>A (23); 1286 3bp del ACA (23); 1291 9bp del CTAGACTAA (23); IVS6 + G82A (54); 981C>T (54); Pro303Pro (54); Pro387Leu (54); rs6020546(55); rs803742(55); rs4811074(55); rs4811075(55); rs6512651(55); rs3787334(55); rs24261(55); rs2038526(55); G381S (55); P387L (55); rs2426164(55); rs1060402(55), 981C>T (53) |

| CD36 | rs1527479 (40,43,44);

rs1984112 (43,44); rs1761667 (20,21,43,44,61);

rs3211938 (44,52); rs1527483 (21,58,43);

rs3212018 16 bp del (43);

478C>T (45); 478delAC

(45); p.L360X T>G (51); c.1079T T>G (51); rs143150225(56); rs147624636(56); rs3173798(65); rs3211892(65); rs3211867 (21,61);

rs1049673(58); rs1194(59); rs2151916(59); rs3211956(59); rs7755(59) |

Multiple studies have reported PTPN1

polymorphisms and their associations with T2DM. A total of 56

PTPN1 polymorphisms were reported by 14 studies (22,23,38,39,41,42,46,49,50,53-55,60,62);

however, only nine studies (22,38,39,42,49,50,55,60,62)

demonstrated 17 SNPs (rs2904268, rs803742, rs1967439, rs718630,

rs4811078, rs2206656, rs3787345, rs3787335, rs941798, rs1570179,

rs754118, rs2282147, rs718050, rs3215684, rs968701, rs16989673 and

rs3787345) which were reported by two or more studies. Furthermore,

Bento et al (22) showed

that multiple PTPN1 SNPs are associated with T2DM; however,

the authors analyzed PTPN1 SNPs association to T2DM based on

subject haplotype. Indeed, the effect sizes from this study were

unsuitable for the method utilized in the present study, using OR

and 95% CI from the per-allele genetic model. Therefore, all these

previous studies (22,23,38,39,41,42,46,49,50,53-55,60,62)

and their reported SNPs, which were not demonstrated by other

studies, were excluded from the present meta-analysis. In addition,

Bodhini et al (39)

demonstrated the association between PTPN1 polymorphisms and

T2DM, but based on Q-Genie quality assessment (score, 26), their

study was also excluded. Both PTPN1 rs968701 and rs3215684

SNPs were reported by three studies (22,42,55),

but due to non-uniform allelic nomenclature reports by Traurig

et al (55) and Florez

et al (42), these two SNPs

were excluded from the analysis. Although PTPN1 rs16989673

SNP was reported by six studies (22,39,49,50,55,62),

estimates that could be included in the present meta-analysis were

only reported by one study. Finally, a total of eight PTPN1

SNPs (rs3787345, rs3787335, rs941798, rs1570179, rs754118,

rs2282147, rs718050 and rs3787348) from four studies (38,42,55,60)

were obtained for meta-analysis.

A total of 14 studies reported 20 CD36

polymorphisms (20,21,40,43-45,47,51,52,56,58,59,61,65).

Five CD36 polymorphisms (rs1527479, rs1761667, rs1984112,

rs3211938 and rs3211867) were reported by six studies (20,21,43,44,58,61);

however, due to their qualities after Q-Genie assessment, data

reported by Gautam et al (43) and Gautam et al (44) were excluded. Wang et al

(58) also reported CD36

rs1527483 polymorphism, but their report did not contain any

association based on the per-allele model. Shukla et al

(20) and Touré et al

(21) conducted subgroup analyses

for patients with T2DM with normal body weight or obesity, whereas

Touré et al (61) only

reported results of analysis in patients with T2DM with normal body

weight. In total, two polymorphisms were retrieved for

meta-analysis, CD36 rs1761667 and rs3211867 SNPs.

Table III

presents the results matrix, which provides an overview of the

availability of study data for inclusion in each meta-analysis. For

each meta-analysis, the matrix identifies whether the study results

were available and eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis of a

specific SNP. Based on the results matrix, results were available

from only a small subset of studies, which may limit the

statistical power to detect true associations, increasing the

potential for both false-positive and false-negative results.

| Table IIIResults matrix indicating whether

study results were available for inclusion in each

meta-analysis. |

Table III

Results matrix indicating whether

study results were available for inclusion in each

meta-analysis.

| |

Result

available for inclusion in meta-analysis number | |

|---|

| Author, year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ahmed et al,

2016 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (36) |

| Alves et al,

2022 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (37) |

| Bento et al,

2004 | X | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | X | X | (22) |

| Bhargave et

al, 2022 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (19) |

| Bodhini et

al, 2011 | X | ? | X | X | X | X | ? | ? | X | X | X | (39) |

| Cheyssac et

al, 2006 | X | V | V | V | V | X | X | V | X | X | X | (60) |

| Corpeleijn et

al, 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (40) |

| Echwald et

al, 2002 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (41) |

| Fang et al,

2023 | V | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (17) |

| Florez et

al, 2005 | X | V | X | V | X | V | V | V | V | X | X | (42) |

| Gautam et

al, 2015 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ? | X | (43) |

| Gautam et

al, 2013 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ? | X | (44) |

| Gautam et

al, 2011 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (45) |

| Gouni-Berthold

et al, 2005 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (46) |

| Hatmal et

al, 2021 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (47) |

| Kwak et al,

2018 | V | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (48) |

| Leprêtre et

al, 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (51) |

| Malodobra et

al, 2011 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (49) |

| Malodobra-Mazur

et al, 2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (50) |

| Martín-Márquez

et al, 2020 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (52) |

| Meshkani et

al, 2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (23) |

| Meshkani et

al, 2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (62) |

| Meyre et al,

2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (56) |

| Mok et al,

2001 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (53) |

| Nishiya et

al, 2020 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (64) |

| Rać et al,

2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (65) |

| Santaniemi et

al, 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (54) |

| Shukla et

al, 2024 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | V | X | (20) |

| Tokuyama et

al, 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (57) |

| Touré et al,

2022 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | V | V | (21) |

| Touré et al,

2022 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | V | V | (61) |

| Traurig et

al, 2007 | X | V | V | X | V | V | X | V | V | X | X | (55) |

| Wang et al,

2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (58) |

| Wanic et al,

2007 | X | V | X | X | X | V | V | V | V | X | X | (38) |

| Wessel et

al, 2015 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (63) |

| Zhang et al,

2018 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | (59) |

Associations between polymorphisms

across three genes and T2DM risk

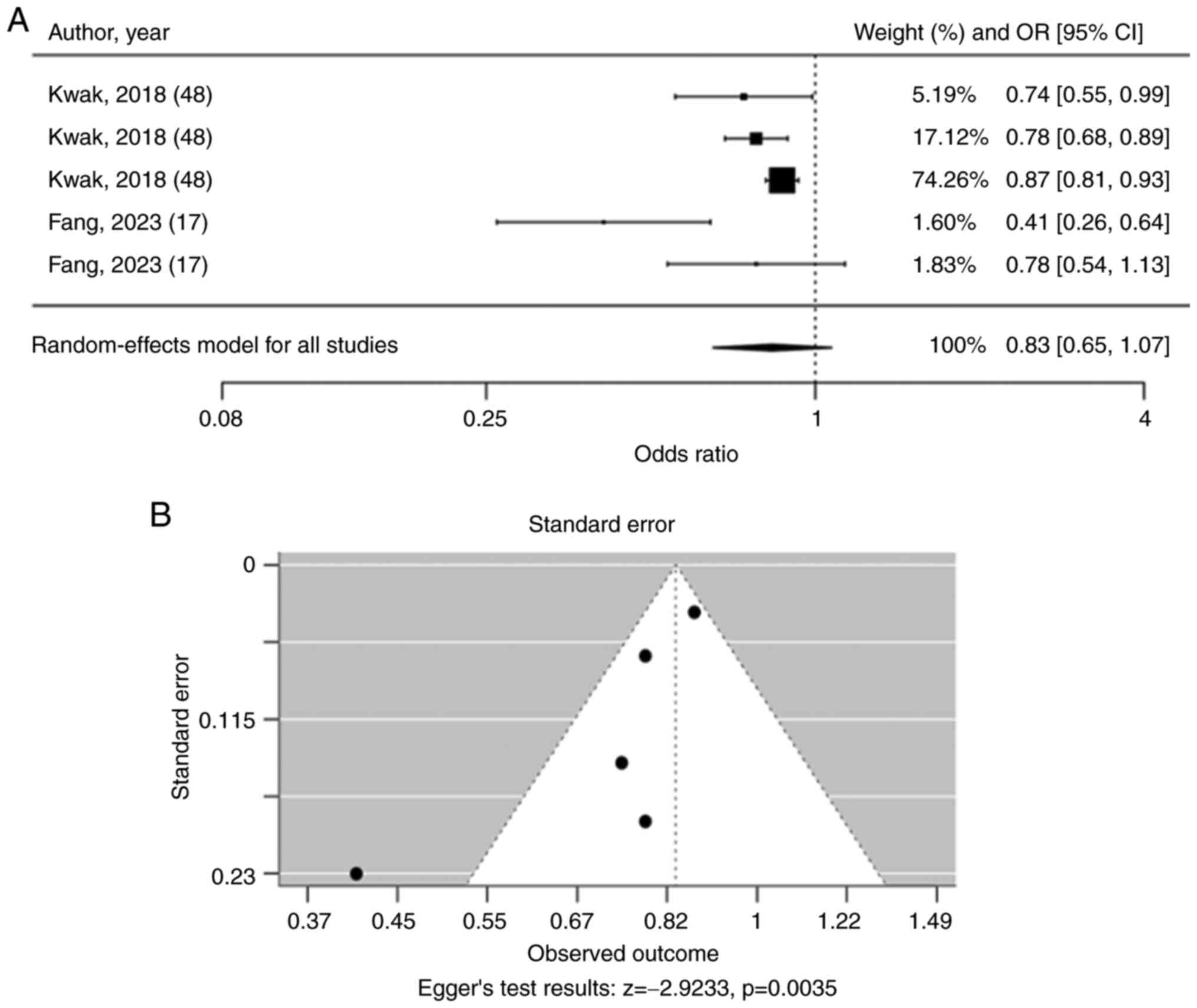

After plotting the results matrix (Table III), nine studies were included

for meta-analysis (17,20,21,38,42,48,55,63,64),

investigating multiple SNPs across three genes: GLP1R,

PTPN1 and CD36. The SNP rs3765467 from the gene

GLP1R was analyzed across five studies from two research

articles (Fig. 2A). The pooled OR

for rs3765467 was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.65-1.07), suggesting no

significant association with T2DM risk. The funnel plot showed

asymmetry, and Egger's test for funnel plot asymmetry was

statistically significant (P=0.0035), suggesting significant

asymmetry, which might indicate publication bias or small-study

effects (Fig. 2B).

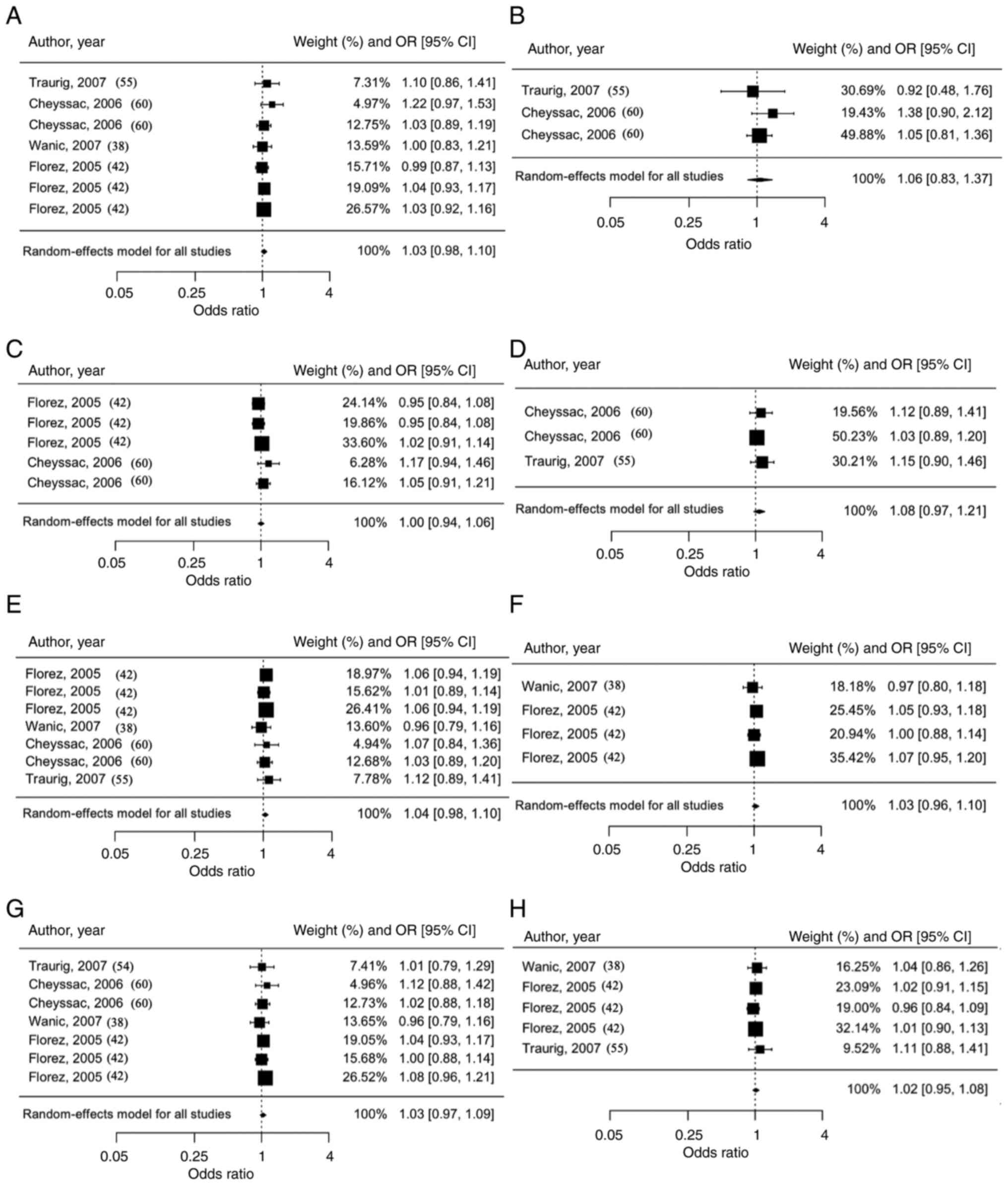

For PTPN1, eight SNPs (rs3787345, rs3787335,

rs941798, rs1570179, rs754118, rs2282147, rs718050 and rs3787348)

were analyzed from a total of 75,595 individuals. Each PTPN1

SNP did not show significant associations with T2DM risk

(rs3787345: OR=1.03, 95% CI=0.98-1.10; rs3787335: OR=1.06, 95%

CI=0.83-1.37; rs941798: OR=1.00, 95% CI=0.94-1.06; rs1570179:

OR=1.08, 95% CI=0.97-1.21; rs754118: OR=1.04, 95% CI=0.98-1.10;

rs2282147: OR=1.03, 95% CI=0.96-1.10; rs718050: OR=1.03, 95%

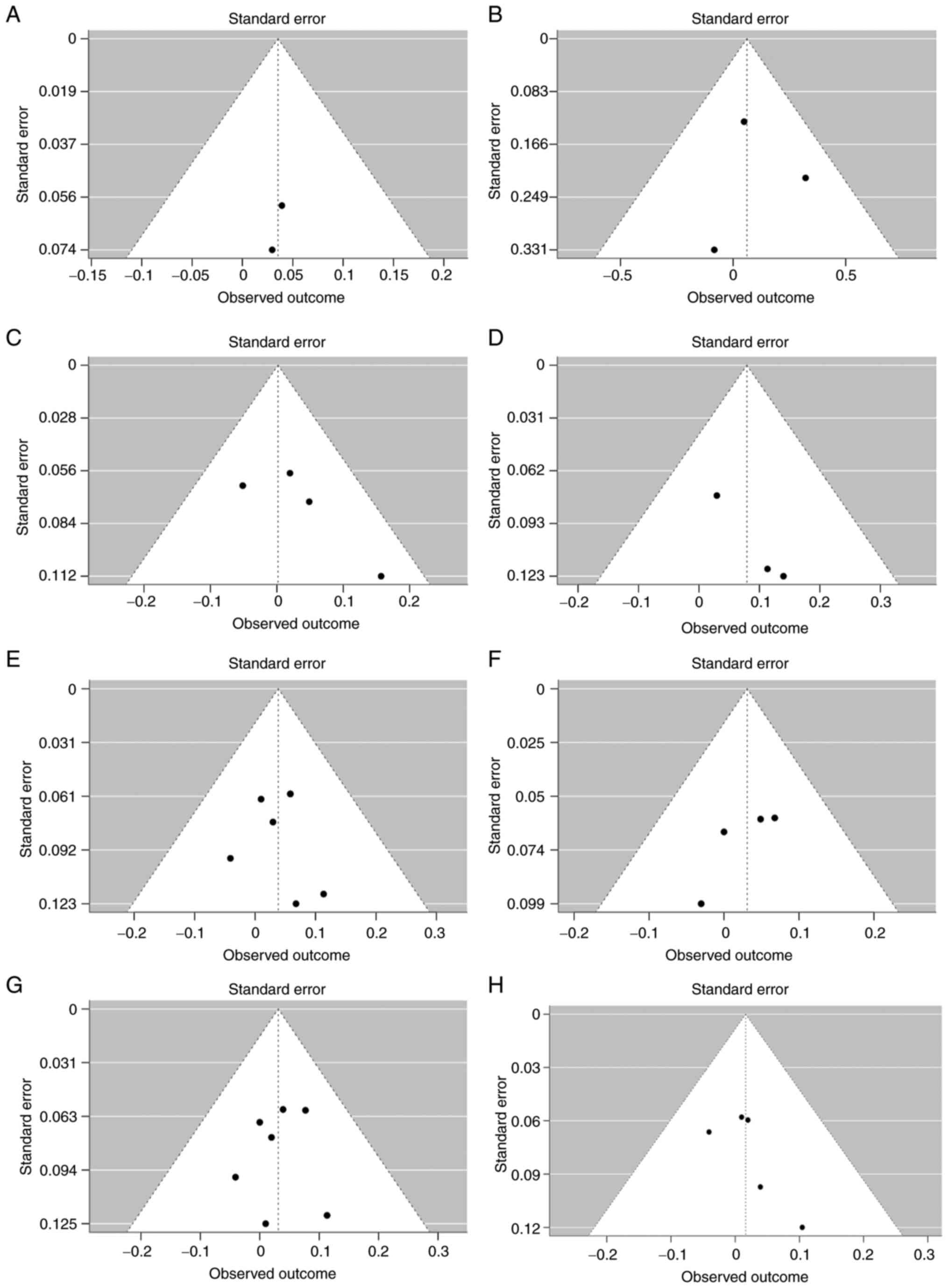

CI=0.97-1.09; and rs3787348: OR=1.02, 95% CI=0.95-1.08) (Fig. 3). Fig.

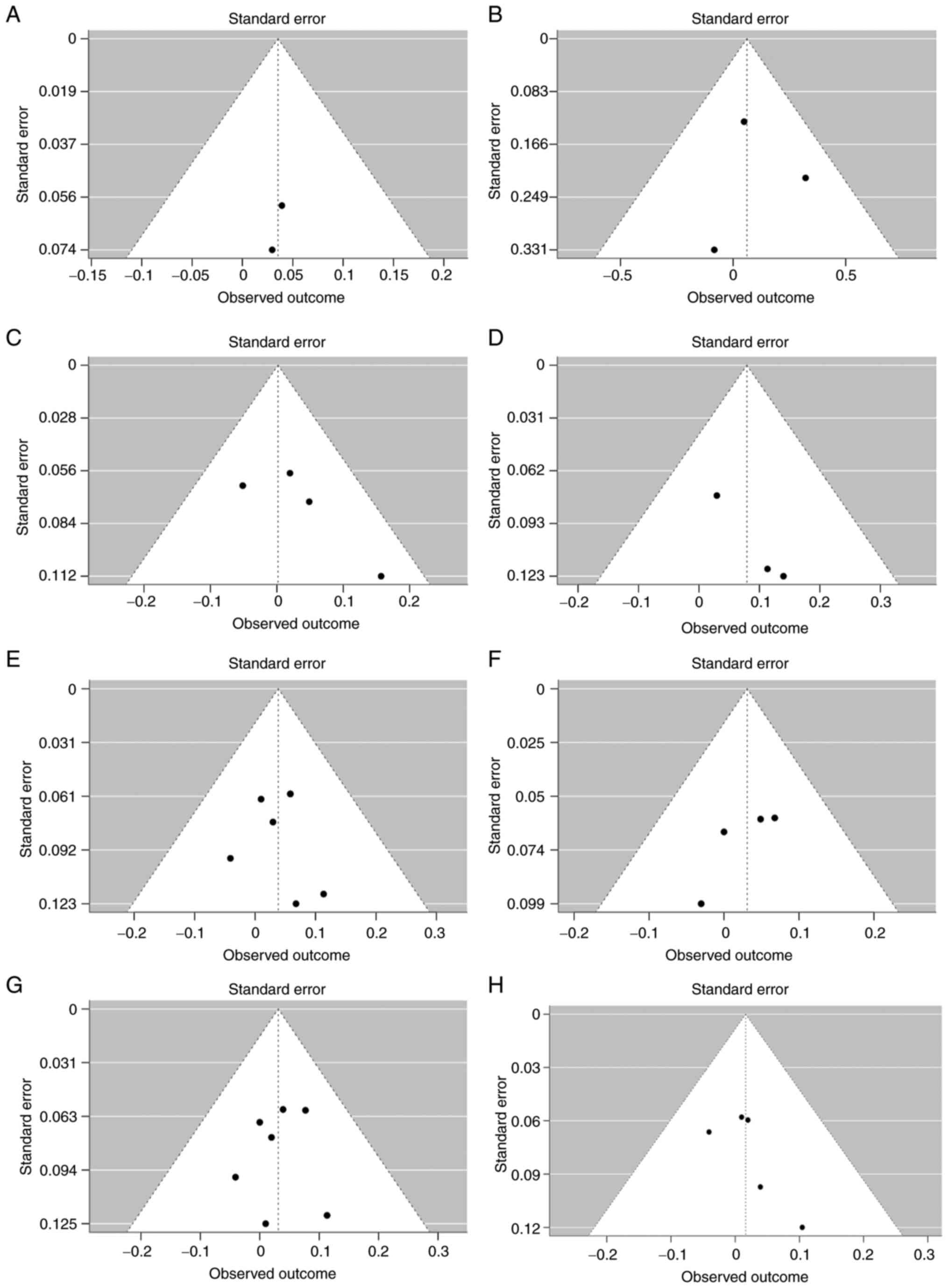

4 shows funnel plots for PTPN1, with each panel

representing a different SNP analyzed for publication bias.

Overall, the results of Egger's tests suggested that all funnel

plots were symmetric (P≥0.05), and therefore, publication bias was

not of concern.

| Figure 4Funnel plot of PTPN1

meta-analyses, separated according to polymorphisms with the

observed outcome on the x-axis and the standard error on the

y-axis. Funnel plots of the PTPN1 polymorphisms (A)

rs3787345, Egger's test: z=0.7744, P=0.4387; (B) rs3787335, Egger's

test: z=-0.2818, P=0.7781; (C) rs941798, Egger's test: z=1.3135,

P=0.1890; (D) rs1570179, Egger's test: z=0.8535, P=0.3934; (E)

rs754118, Egger's test: z=-0.0047, P=0.9963; (F) rs2282147, Egger's

test: z=-0.8002, P=0.4236; (G) rs718050, Egger's test: z=-0.4236,

P=0.6719; (H) rs3787348, Egger's test: z=0.7685; P=0.4422.

PTPN1, protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 1. |

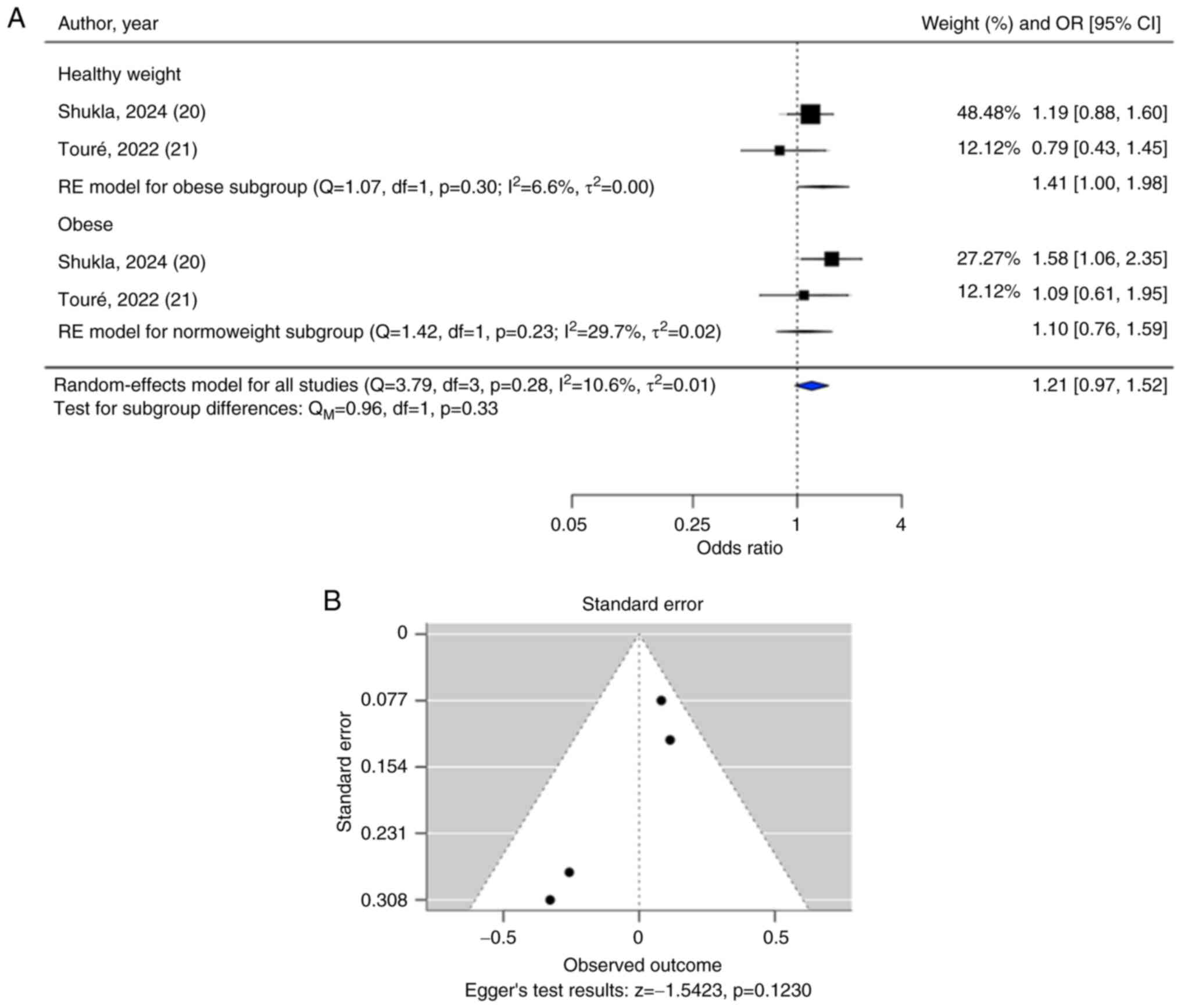

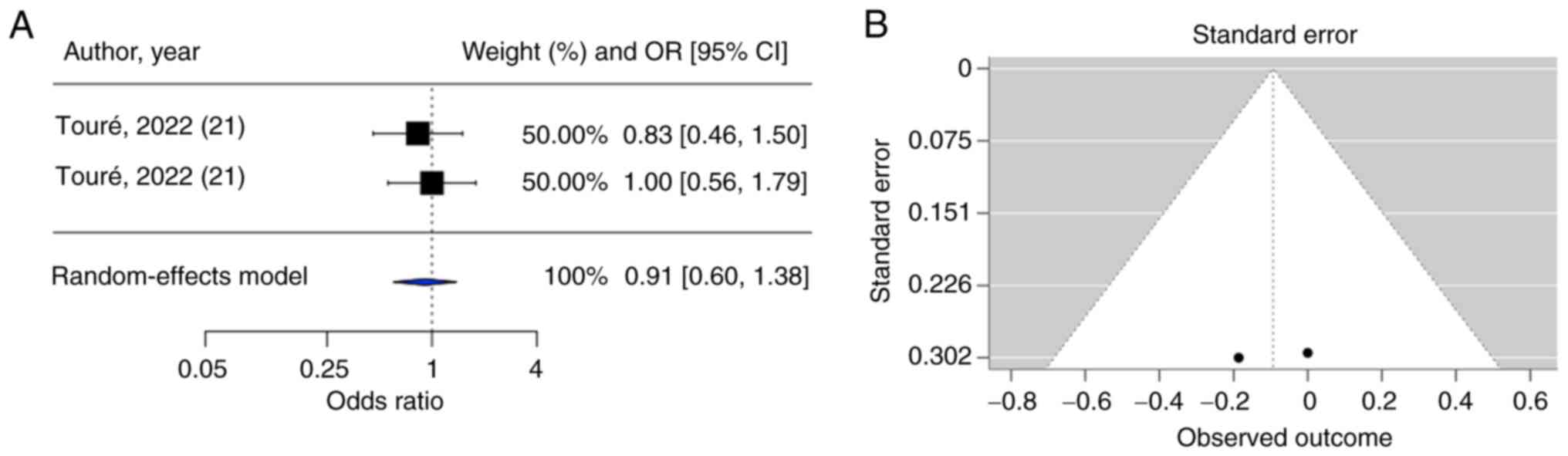

Both meta-analyses on CD36 rs1761667 and

rs3211867 polymorphisms showed that no significant overall

association was observed with the risks of T2DM (rs1761667:

OR=1.21, 95% CI=0.97-1.52; rs3211867: OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.60-1.38)

(Figs. 5A and 6A). After categorizing studies based on

the body weight category of the participants, a subgroup analysis

of CD36 rs1761667 also showed no significant associations

for both the subgroup of patients with T2DM with normal body weight

(OR=1.41; 95% CI=1.00-1.98) and the subgroup of patients with T2DM

who were obese (OR=1.10; 95% CI=0.76-1.59).

The funnel plot for the CD36 rs1761667

polymorphism (Fig. 5B) and the

result of Egger's test suggested that the funnel plot was symmetric

(P≥0.05), indicating that publication bias was not a concern.

However, for the CD36 rs3211867 polymorphism (Fig. 6B), the inclusion of only two

studies precluded regression-based tests for small-study effects;

accordingly, the funnel plot for this analysis should be

interpreted with caution, as no formal inference about small-study

bias was feasible.

Sensitivity analyses

Leave-one-out analyses were conducted for

GLP1R and PTPN1, where each individual study was

systematically omitted to assess the influence of each study on the

overall results. With regard to the GLP1R polymorphism,

exclusion of the study by Wanic et al (38) yielded results that exhibited some

variation in comparison to the overall meta-analysis (Fig. S1). The association between the

GLP1R rs3765467 polymorphism and T2DM became statistically

significant in each iteration. Similarly, the results of

leave-one-out analyses of the PTPN1 polymorphisms indicated

some minor fluctuations in effect estimates across iterations, in

comparison to the findings of the overall meta-analyses. However,

none of these changes altered the statistical significance or

overall direction of the pooled outcomes, indicating that the

results were robust to the exclusion of any single study (Fig. S2).

This suggests that the particular studies may have

had some influence on the findings; however, this should be

considered part of a broader sensitivity analysis rather than a

definitive indication of its impact. Further investigation, such as

examining the methodology, sample size or population

characteristics of studies, would be needed before making any

strong conclusions about its influence.

Discussion

In the present study, the genetic polymorphisms of

four genes, DPP4, GLP1R, PTPN1 and

CD36, and their association with T2DM risk were evaluated.

Due to study limitations in the genetic model and the number of

SNPs reported by fewer than two studies, a meta-analysis on

DPP4 polymorphisms was not performed. The meta-analysis of

GLP1R polymorphisms included 17,661 individuals, whereas

meta-analyses of PTPN1 and CD36 polymorphisms were

performed with data from 75,595 and 825 individuals,

respectively.

Metabolic gene polymorphism can lead to different

protein regulation (14,15) and therefore increases the risk for

T2DM (36,64). However, since T2DM is a complex

disease that cannot be explained by defects on a single gene alone

(66,67), and due to a complex interaction of

DPP4, GLP1R, CD36 and PTPN1 in obesity and T2DM, an

overlapping polymorphism of these four genes might occur in obese

and T2DM individuals and determine the cumulative risk of T2DM in

obese individuals. To the best of our knowledge, the present study

is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis

reporting DPP4, GLP1R, CD36 and PTPN1 and the risk of

T2DM. The present meta-analysis showed no association of

PTPN1 and T2DM risk, which is in line with results reported

in the literature reviewed in the present study (22,23,38,39,41,42,46,49,50,53-55,60,62).

The present study has shown that multiple SNPs of

DPP4, GLP1R, PTPN and CD36 are frequent

in both diabetic and non-diabetic individuals. Although

associations of DPP4 (19,36),

GLP1R (17,48,57,63,64)

and CD36 (20,21,40,43,44,51,52,58,59,61,65)

polymorphisms and T2DM risk and or relevant biochemical parameters

were previously reported, including primary studies that were

included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis, the

present study uncovered no significant associations between

GLP1R and CD36 polymorphisms and T2DM risk. All

referenced studies are based on primary data, their methodological

approaches are therefore not directly comparable to the present

systematic review and meta-analysis. Primary studies are

constrained by their individual design features, including sampling

techniques, measurement instruments and analytic strategies. By

contrast, systematic reviews and meta-analyses apply explicit

inclusion criteria, weight individual effect sizes according to

their precision and model between-study heterogeneity through

random-effects variance components. These methodological

distinctions limit the direct comparability of findings from

primary studies with those derived from pooled evidence.

The present findings emphasize the strength of

meta-analysis as the random-effects model incorporates

between-study heterogeneity, providing pooled estimates that are

less influenced by outliers and offering a more robust,

generalizable summary of the available evidence. The outcome of the

meta-analysis does not negate the findings of the individual

studies, it rather indicates the underlying variability and that

when considering all of the evidence, the overall association is

more uncertain. In all meta-analyses, the random-effects analyses

estimate the average and variability of effects across studies. The

95% CIs for the overall estimates in the present study (shown as

diamonds) are wide because there are few studies available for all

meta-analyses, some of which have small sample sizes.

In the sensitivity analyses, using the

leave-one-out technique, the association between the GLP1R

rs3765467 polymorphism and T2DM became statistically significant in

each iteration. This finding suggests that the overall results are

sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of individual studies,

which may point to potential limitations such as heterogeneity,

publication and variability in study quality. The fact that

statistical significance was achieved in this leave-one-out

iteration indicates that some studies may have been masking a true

effect when included together. This sensitivity to individual

studies suggests that there may be underlying differences in the

study designs, populations or outcomes that contributed to the

overall non-significant result when all studies were included.

Moreover, heterogeneity between studies could be driven by

variations in study methodologies, sample sizes or differences in

how outcomes were measured, which might dilute the pooled effect

and make it difficult to detect statistically significant results.

Publication bias could also be a factor, although funnel plot

inspection and Egger's test did not reveal clear evidence.

Nevertheless, the possibility of residual bias cannot be fully

dismissed, given the potential under-representation of studies

reporting non-significant findings.

It is also important to note that although the

meta-analysis aggregated data from multiple studies, some of the

studies originated from the same manuscripts but reported on

different subpopulations. These subpopulations were pooled together

without adjusting for potential covariates that might influence the

results. Combining these subpopulations without accounting for

differences in important covariates, such as age, sex or baseline

characteristics (such as T2DM disease onset and comorbidity

conditions) might ignore the structural differences from this

population stratification and could introduce bias and confound the

true effect size (68). In the

present study, the focus was on the risk of T2DM and obesity only,

without considering the other outcomes which are related to T2DM,

such as DM stage, blood sugar level and clinical response to

antidiabetic drugs.

Additionally, phenotypic misclassification is a

further source of variability; variably separated subtypes or

subphenotypes could overestimate or underestimate the true effect

size. Environmental effect modifiers vary markedly across settings

represented in the present meta-analysis, including unmeasured

long-term air pollution exposure, dietary patterns, socioeconomic

context and urbanization. The present analysis did not account for

these gene-environment interactions, which could therefore manifest

as between-study heterogeneity or dilute the pooled estimates.

Future analyses should consider adjusting for these covariates or

performing subgroup analyses to ensure a more accurate

interpretation of the pooled estimates (69,70).

The present study benefited from several strengths

which should be acknowledged; Firstly, the systematic review

utilized broad search terms across four different research

databases, ensuring high sensitivity in capturing relevant

literature. Secondly, studies from all available publication years

were included, thus providing a comprehensive overview of the

field. In addition, to ensure the quality of the primary studies

included in the meta-analysis, a rigorous two-step assessment

process was implemented, utilizing the Q-Genie tool and the ROB-ME

framework to evaluate potential biases and methodological quality.

This thorough evaluation helps to ensure that the studies included

in the present analysis meet high standards of scientific rigor,

therefore strengthening the validity of this meta-analysis. All

aforementioned steps were conducted following a protocol which has

been registered in PROSPERO prior to the study. Moreover, the

extensive analyses focused on four different genes, encompassing a

total of 11 SNPs. This multifaceted approach not only provides

insight into the specific genetic variations of interest but also

contributes to a deeper comprehension of the genetic factors

associated with the risk of T2DM. Finally, a comprehensive

assessment of publication was employed through two rigorous steps:

Visually inspecting funnel plots and conducting Egger's test for a

more thorough examination of the potential impact of publication

bias on the results.

Although GLP1R has a critical role in

glucose metabolism (1,2) and serves as a pharmacological target

of the previously reported drug semaglutide, which is effective in

lowering blood glucose and body weight (71), the present results indicated that

the GLP1R polymorphism assessed in the present study should

not be used as a base for the GLP1R agonist therapeutic option, as

previously outlined in the study limitations section (and similarly

observed in the meta-analysis of other genes). The inclusion of a

wide range of data variability from different cohorts and studies

that employ different methodologies in the present study may result

in varying degrees of data availability for meta-analysis and

affect the result of the meta-analysis. This distinction should

guide the clinical interpretation of the results, as some included

studies reported significant associations under fixed-effect

assumptions, whereas our meta-analysis applied a random-effects

model that accounts for between-study heterogeneity, resulting in a

non-significant pooled effect.

Future studies should focus on more comprehensive

and diverse cohorts to generate robust data from populations by

employing polygenic risk score analysis on genome-wide association

studies or using a multi-omics integration approach. This will

allow reproducibility, reliability and quality of evidence for

future systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

In conclusion, the 11 meta-analyses performed in

the present study did not identify significant associations between

specific genetic variants of interest and the risk of T2DM. Despite

the extensive systematic review and meta-analysis of data from

multiple studies, the evidence for the influence of various SNPs

across key metabolic-associated genes, such as DPP4,

GLP1R, PTPN1 and CD36, on T2DM risk, was not

statistically significant.

These findings suggest that the genetic factors

investigated in the present study may not serve a crucial role in

the etiology of T2DM, or that their effects may be masked by other

determinants, such as lifestyle and environmental factors. The lack

of significant associations also highlights the complexity of T2DM

as a multifactorial condition where genetic and non-genetic factors

interact.

The rigorous assessment of study quality and

publication bias in the present study reinforces the validity of

the results, suggesting that the absence of significant findings is

robust and not a result of methodological limitations. Future

research should continue to explore this area with larger and more

diverse populations, potentially considering additional genetic

variants and their interactions with other contributing factors to

improve the understanding of the multifaceted nature of this

disease.

Supplementary Material

Forest plot of the leave-one-out

analysis for the GLP1R rs3765467 polymorphism. CI,

confidence interval. Study removed for each iteration: Study 1,

n=917 (48); study 2, n=3,026

(48); study 3, n=13,122 (48); study 4, n=282 (17); and study 5, n=324 (17). *P<0.05.

Forest plot of the leave-one-out

analyses for the PTPN1 polymorphisms. (A) rs3787345. Study

removed for each iteration: Study 1, n=939 (55); study 2, n=638 (60); study 3, n=1,638 (60); study 4, n=1,746 (38); study 5, n=2,018 (42); study 6, n=2,452 (42); and study 7, n=3,413 (42). (B) rs3787335. Study removed for

each iteration: Study 1, n=1,008 (55); study 2, n=638 (60); and study 3, n=1,638 (60). (C) rs941798. Study removed for each

iteration: Study 1, n=2,452 (42);

study 2, n=2,018 (42); study 3,

n=3,413 (42); study 4, n=638

(60); and study 5, n=1,638

(60). (D) rs1570179. Study

removed for each iteration: Study 1, n=638 (60); study 2, n=1,638 (60); and study 3, n=985 (55). (E) rs754118. Study removed for each

iteration: Study 1, n=2,452 (42);

study 2, n=2,018 (42); study 3,

n=3,413 (42); study 4, n=1,758

(38); study 5, n=638 (60); study 6, n=1,638 (60); and study 7, n=1,006 (55). (F) rs2282147. Study removed for

each iteration: Study 1, n=1,752 (38); study 2, n=2,452 (42); study 3, n=2,018 (42); and study 4, n=3,413 (42). (G) rs718050. Study removed for each

iteration: Study 1, n=954 (55);

study 2, n=638 (60); study 3,

n=1,638 (60); study 4, n=1,756

(38); study 5, n=2,452 (42); study 6, n=2,018 (42); and study 7, n=3,413 (42). (H) rs3787348. Study removed for

each iteration: Study 1, n=1,726 (38); study 2, n=2,452 (42); study 3, n=2,018 (42); study 4, n=3,413 (42); and study 5, n=1,011 (55). CI, confidence interval.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank two research assistants (Dr Ghina

Widiasih and Dr Inggrit Bela Thesman; Department of Physiology,

Faculty of Medicine, Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta,

Indonesia) for their valuable help during article screening. The

authors also express their appreciation to Dr Alice Blandino from

the Institute for Medical Biometry, Heidelberg University,

Heidelberg, Germany for her valuable inputs in genetic statistical

methodology.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Institute of

Research and Community Services, Universitas Sebelas Maret through

the International Research Collaboration Scheme (grant no.

194.2/UN27.22/PT.01.03/2024) between Universitas Sebelas Maret,

Indonesia and Heidelberg University, Germany.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DI was responsible for the conceptualization of the

present study, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology,

project administration, supervision, validation, and reviewing and

editing the manuscript. TNS, YHS, PSR and YF curated the data and

were involved in the investigation, and reviewing and editing of

the manuscript. YCW was responsible for the conceptualization of

the present study, funding acquisition, data curation,

investigation, supervision, methodology, validation, and reviewing

and editing the manuscript. MRM was responsible for the

conceptualization of the present study, funding acquisition, data

curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software

(analysis using software and generation of figures), supervision,

validation, visualization, writing the original draft preparation

and writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. MRM and DI

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sun EW, de Fontgalland D, Rabbitt P,

Hollington P, Sposato L, Due SL, Wattchow DA, Rayner CK, Deane AM,

Young RL and Keating DJ: Mechanisms controlling Glucose-induced

GLP-1 secretion in human small intestine. Diabetes. 66:2144–2149.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Deacon CF: Physiology and pharmacology of

DPP-4 in glucose homeostasis and the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 10(80)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Regmi D, Al-Shamsi S, Govender RD and Al

Kaabi J: Incidence and risk factors of type 2 diabetes mellitus in

an overweight and obese population: A long-term retrospective

cohort study from a Gulf state. BMJ Open.

10(e035813)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ying Z, van Eenige R, Ge X, van Marwijk C,

Lambooij JM, Guigas B, Giera M, de Boer JF, Coskun T, Qu H, et al:

Combined GIP receptor and GLP1 receptor agonism attenuates NAFLD in

male APOE*3-Leiden.CETP mice. EBioMedicine.

93(104684)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tomas E and Habener JF: Insulin-like

actions of Glucagon-like peptide-1: A dual receptor hypothesis.

Trends Endocrinol Metab. 21:59–67. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Rubio C, Puerto M, García-Rodríquez JJ, Lu

VB, García-Martínez I, Alén R, Sanmartín-Salinas P, Toledo-Lobo MV,

Saiz J, Ruperez J, et al: Impact of global PTP1B deficiency on the

gut barrier permeability during NASH in mice. Mol Metab.

35(100954)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ji W, Chen X, Lv J, Wang M, Ren S, Yuan B,

Wang B and Chen L: Liraglutide exerts antidiabetic effect via PTP1B

and PI3K/Akt2 signaling pathway in skeletal muscle of KKAy Mice.

Int J Endocrinol. 2014(312452)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chen Y, Zhang J, Cui W and Silverstein RL:

CD36, a signaling receptor and fatty acid transporter that

regulates immune cell metabolism and fate. J Exp Med.

219(e20211314)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Alkhatatbeh MJ, Enjeti AK, Acharya S,

Thorne RF and Lincz LF: The origin of circulating CD36 in type 2

diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. 3(e59)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Handberg A, Norberg M, Stenlund H,

Hallmans G, Attermann J and Eriksson JW: Soluble CD36 (sCD36)

clusters with markers of insulin resistance, and high sCD36 is

associated with increased type 2 diabetes risk. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 95:1939–1946. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Handberg A, Levin K, Højlund K and

Beck-Nielsen H: Identification of the oxidized Low-density

lipoprotein scavenger receptor CD36 in plasma. Circulation.

114:1169–1176. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Shibao CA, Celedonio JE, Tamboli R, Sidani

R, Love-Gregory L, Pietka T, Xiong Y, Wei Y, Abumrad NN, Abumrad NA

and Flynn CR: CD36 Modulates fasting and preabsorptive hormone and

bile acid levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 103:1856–1866.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Adam TCM and Westerterp-Plantenga MS:

Glucagon-like peptide-1 release and satiety after a nutrient

challenge in normal-weight and obese subjects. Br J Nutr.

93:845–851. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sell H, Blüher M, Klöting N, Schlich R,

Willems M, Ruppe F, Knoefel WT, Dietrich A, Fielding BA, Arner P,

et al: Adipose Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 and Obesity: Correlation with

insulin resistance and depot-specific release from adipose tissue

in vivo and in vitro. Diabetes Care. 36:4083–4090. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bonen A, Tandon NN, Glatz JFC, Luiken JJFP

and Heigenhauser GJF: The fatty acid transporter FAT/CD36 is

upregulated in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues in human

obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Obes (Lond). 30:877–883.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Elchebly M, Payette P, Michaliszyn E,

Cromlish W, Collins S, Loy AL, Normandin D, Cheng A, Himms-Hagen J,

Chan CC, et al: Increased insulin sensitivity and obesity

resistance in mice lacking the protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B

gene. Science. 283:1544–1548. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Fang Y, Zhang J, Ji L, Zhu C, Xiao Y, Gao

Q, Song W and Wei L: GLP1R rs3765467 Polymorphism is associated

with the risk of early onset type 2 diabetes. Int J Endocrinol.

2023(8729242)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Dorsey-Trevino EG, Kaur V, Mercader JM,

Florez JC and Leong A: Association of GLP1R polymorphisms with the

incretin response. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 107:2580–2588.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Bhargave A, Devi K, Ahmad I, Yadav A and

Gupta R: Genetic variation in DPP-IV gene linked to predisposition

of T2DM: A case control study. J Diabetes Metab Disord.

21:1709–1716. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Shukla AK, Shamsad A, Kushwah AS, Singh S,

Usman K and Banerjee M: CD36 gene variant rs1761667(G/A) as a

biomarker in obese type 2 diabetes mellitus cases. Egypt J Med Hum

Genet. 25(9)2024.

|

|

21

|

Touré M, Hichami A, Sayed A, Suliman M,

Samb A and Khan NA: Association between polymorphisms and

hypermethylation of CD36 gene in obese and obese diabetic

Senegalese females. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 14(117)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Bento JL, Palmer ND, Mychaleckyj JC, Lange

LA, Langefeld CD, Rich SS, Freedman BI and Bowden DW: Association

of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B gene polymorphisms with type 2

diabetes. Diabetes. 53:3007–3012. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Meshkani R, Taghikhani M, Al-Kateb H,

Larijani B, Khatami S, Sidiropoulos GK, Hegele RA and Adeli K:

Polymorphisms within the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTPN1)

gene promoter: Functional characterization and association with

type 2 diabetes and related metabolic traits. Clin Chem.

53:1585–1592. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Lefebvre C, Manheimer E and Glanville J:

Searching for Studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews

of Interventions (eds J.P. Higgins and S. Green), 2008. Available

from: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184.ch6.

|

|

25

|

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z and

Elmagarmid A: Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews.

Syst Rev. 5(210)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Li T, Higgins JPT and Deeks JJ: Chapter 5:

Collecting data. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of

Interventions version 6.5. Cochrane, 2024. Higgins JPT, Thomas J,

Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ and Welch VA (eds). Available

from https://cochrane.org/handbook.

|

|

27

|

Sohani ZN, Sarma S, Alyass A, de Souza RJ,

Robiou-du-Pont S, Li A, Mayhew A, Yazdi F, Reddon H, Lamri A, et

al: Empirical evaluation of the Q-Genie tool: A protocol for

assessment of effectiveness. BMJ Open. 6(e010403)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Page MJ, Sterne JAC, Boutron I,

Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham JJ, Li T, Lundh A, Mayo-Wilson E, McKenzie

JE, Stewart LA, et al: ROB-ME: A tool for assessing risk of bias

due to missing evidence in systematic reviews with meta-analysis.

BMJ. 383(e076754)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Little J, Higgins JPT, Ioannidis JPA,

Moher D, Gagnon F, von Elm E, Khoury MJ, Cohen B, Davey-Smith G,

Grimshaw J, et al: STrengthening the REporting of Genetic

Association Studies (STREGA)-an extension of the STROBE statement.

Genet Epidemiol. 33:581–598. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Mahanani M, Susilawati T, Wibowo Y and

Indarto D: The risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and

metabolic-related gene polymorphism. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024531067,

PROSPERO 2024.

|

|

31

|

Jackson D, Law M, Stijnen T, Viechtbauer W

and White IR: A comparison of seven Random-effects models for

meta-analyses that estimate the summary odds Ratio. In: Statistics

in Medicine. Wiley Online Library, 2018.

|

|

32

|

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M and

Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical

test. BMJ. 315:629–634. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Willis BH and Riley RD: Measuring the

statistical validity of summary meta-analysis and meta-regression

results for use in clinical practice. Stat Med. 36:3283–3301.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Viechtbauer W: Conducting Meta-analyses in

R with the metafor package. J Stati Software. 36:1–48. 2010.

|

|

35

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ahmed RH, Huri HZ, Al-Hamodi Z, Salem SD,

Al-Absi B and Muniandy S: Association of DPP4 gene polymorphisms

with type 2 diabetes mellitus in malaysian subjects. PLoS One.

11(e0154369)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Alves ES, Tonet-Furioso AC, Alves VP,

Moraes CF, Pérez DIV, Bastos IMD, Córdova C and Nóbrega OT: A

haplotype in the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 gene impacts

glycemic-related traits of Brazilian older adults. Braz J Med Biol

Res. 55(e12148)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wanic K, Malecki MT, Klupa T, Warram JH,

Sieradzki J and Krolewski AS: Lack of association between

polymorphisms in the gene encoding protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B

(PTPN1) and risk of Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 24:650–655.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Bodhini D, Radha V, Ghosh S, Majumder PP

and Mohan V: Lack of association of PTPN1 gene polymorphisms with

type 2 diabetes in south Indians. J Genet. 90:323–326.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Corpeleijn E, Van Der Kallen CJH,

Kruijshoop M, Magagnin MG, de Bruin TW, Feskens EJ, Saris WH and

Blaak EE: Direct association of a promoter polymorphism in the

CD36/FAT fatty acid transporter gene with Type 2 diabetes mellitus

and insulin resistance. Diabet Med. 23:907–911. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Echwald SM, Bach H, Vestergaard H,

Richelsen B, Kristensen K, Drivsholm T, Borch-Johnsen K, Hansen T

and Pedersen O: A P387L variant in protein tyrosine Phosphatase-1B

(PTP-1B) is associated with type 2 diabetes and impaired serine

phosphorylation of PTP-1B in vitro. Diabetes. 51:1–6.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Florez JC, Agapakis CM, Burtt NP, Sun M,

Almgren P, Råstam L, Tuomi T, Gaudet D, Hudson TJ, Daly MJ, et al:

Association testing of the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B gene

(PTPN1) with type 2 diabetes in 7,883 people. Diabetes.

54:1884–1891. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Gautam S, Agrawal CG and Banerjee M: CD36

gene variants in early prediction of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 19:144–149. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Gautam S, Pirabu L, Agrawal CG and

Banerjee M: CD36 gene variants and their association with type 2

diabetes in an Indian population. Diabetes Technol Ther.

15:680–687. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Gautam S, Agrawal CG, Bid HK and Banerjee

M: Preliminary studies on CD36 gene in type 2 diabetic patients

from north India. Indian J Med Res. 134:107–112. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gouni-Berthold I, Giannakidou E,

Müller-Wieland D, Faust M, Kotzka J, Berthold HK and Krone W: The

Pro387Leu variant of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B is not

associated with diabetes mellitus type 2 in a German population. J

Intern Med. 257:272–280. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Hatmal MM, Alshaer W, Mahmoud IS,

Al-Hatamleh MAI, Al-Ameer HJ, Abuyaman O, Zihlif M, Mohamud R,

Darras M, Al Shhab M, et al: Investigating the association of CD36

gene polymorphisms (rs1761667 and rs1527483) with T2DM and

dyslipidemia: Statistical analysis, machine learning based

prediction, and meta-analysis. PLoS One.

16(e0257857)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Kwak SH, Chae J, Lee S, Choi S, Koo BK,

Yoon JW, Park JH, Cho B, Moon MK, Lim S, et al: Nonsynonymous

Variants in PAX4 and GLP1R are associated with type 2 diabetes in

an East Asian population. Diabetes. 67:1892–1902. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Malodobra M, Pilecka A, Gworys B and

Adamiec R: Single nucleotide polymorphisms within functional

regions of genes implicated in insulin action and association with

the insulin resistant phenotype. Mol Cell Biochem. 349:187–193.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Malodobra-Mazur M, Lebioda A, Majda F,

Skoczyńska A and Dobosz T: Correlation of SNP polymorphism in GAD2

and PTPN1 genes with type 2 diabetes in obese people. Diabetologia

Doswiadczalna i Kliniczna. (7)2007.

|

|

51

|

Leprêtre F, Vasseur F, Vaxillaire M,

Scherer PE, Ali S, Linton K, Aitman T and Froguel P: A CD36

nonsense mutation associated with insulin resistance and familial

type 2 diabetes. Hum Mutat. 24(104)2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Martín-Márquez BT, Sandoval-Garcia F,

Vazquez-Del Mercado M, Martínez-García EA, Corona-Meraz FI,

Fletes-Rayas AL and Zavaleta-Muñiz SA: Contribution of rs3211938

polymorphism at CD36 to glucose levels, oxidized low-density

lipoproteins, insulin resistance, and body mass index in Mexican

mestizos with type-2 diabetes from western Mexico. Nutr Hosp.

38:742–748. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Mok A, Cao H, Zinman B, Hanley AJG, Harris

SB, Kennedy BP and Hegele RA: A single nucleotide polymorphism in

protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP-1B is associated with protection

from diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance in Oji-Cree. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 87:724–727. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Santaniemi M, Ukkola O and Kesäniemi YA:

Tyrosine phosphatase 1B and leptin receptor genes and their

interaction in type 2 diabetes. J Intern Med. 256:48–55.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Traurig M, Hanson RL, Kobes S, Bogardus C

and Baier LJ: Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B is not a major

susceptibility gene for type 2 diabetes mellitus or obesity among

Pima Indians. Diabetologia. 50:985–989. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Meyre D, Andress EJ, Sharma T, Snippe M,

Asif H, Maharaj A, Vatin V, Gaget S, Besnard P, Choquet H, et al:

Contribution of rare coding mutations in CD36 to type 2 diabetes

and cardio-metabolic complications. Sci Rep.

9(17123)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Tokuyama Y, Matsui K, Egashira T, Nozaki

O, Ishizuka T and Kanatsuka A: Five missense mutations in

glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor gene in Japanese population.

Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 66:63–69. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Wang Y, Zhou XO, Zhang Y, Gao PJ and Zhu

DL: Association of the CD36 gene with impaired glucose tolerance,

impaired fasting glucose, type-2 diabetes, and lipid metabolism in

essential hypertensive patients. Genet Mol Res. 11:2163–2170.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Zhang D, Zhang R, Liu Y, Sun X, Yin Z, Li

H, Zhao Y, Wang B, Ren Y, Cheng C, et al: CD36 gene variants is

associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus through the interaction of

obesity in rural Chinese adults. Gene. 659:155–159. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Wessel J, Chu AY, Willems SM, Wang S,

Yaghootkar H, Brody JA, Dauriz M, Hivert MF, Raghavan S, Lipovich

L, et al: Low-frequency and rare exome chip variants associate with

fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes susceptibility. Nat Commun.

6(5897)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Nishiya Y, Daimon M, Mizushiri S, Murakami

H, Tanabe J, Matsuhashi Y, Yanagimachi M, Tokuda I, Sawada K and

Ihara K: Nutrient consumption-dependent association of a

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor gene polymorphism with insulin

secretion. Sci Rep. 10(16382)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Rać ME, Suchy J, Kurzawski G, Kurlapska A,

Safranow K, Rać M, Sagasz-Tysiewicz D, Krzystolik A, Poncyljusz W,

Jakubowska K, et al: Polymorphism of the CD36 gene and

cardiovascular risk factors in patients with coronary artery

disease manifested at a young age. Biochem Genet. 50:103–111.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Cheyssac C, Lecoeur C, Dechaume A, Bibi A,

Charpentier G, Balkau B, Marre M, Froguel P, Gibson F and

Vaxillaire M: Analysis of common PTPN1 gene variants in type 2

diabetes, obesity and associated phenotypes in the French

population. BMC Med Genet. 7(44)2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Touré M, Samb A, Sène M, Thiam S, Mané

CAB, Sow AK, Ba-Diop A, Kane MO, Sarr M, Ba A and Gueye L: Impact

of the interaction between the polymorphisms and hypermethylation

of the CD36 gene on a new biomarker of type 2 diabetes mellitus:

Circulating soluble CD36 (sCD36) in Senegalese females. BMC Med

Genomics. 15(186)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Meshkani R, Taghikhani M, Mosapour A,

Larijani B, Khatami S, Khoshbin E, Ahmadvand D, Saeidi P, Maleki A,

Yavari K, et al: 1484insG polymorphism of the PTPN1 gene is

associated with insulin resistance in an Iranian population. Arch

Med Res. 38:556–562. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Ali O: Genetics of type 2 diabetes. World

J Diabetes. 4:114–123. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Groop L and Pociot F: Genetics of

diabetes-are we missing the genes or the disease? Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 382:726–739. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Szczerbinski L, Mandla R, Schroeder P,

Porneala BC, Li JH, Florez JC, Mercader JM, Manning AK and Udler

MS: Algorithms for the identification of prevalent diabetes in the

All of Us Research Program validated using polygenic scores. Sci

Rep. 14(26895)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Zhang JS, Gui ZH, Zou ZY, Yang BY, Ma J,

Jing J, Wang HJ, Luo JY, Zhang X, Luo CY, et al: Long-term exposure

to ambient air pollution and metabolic syndrome in children and

adolescents: A national cross-sectional study in China. Environ

Int. 148(106383)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Kapellou A, Salata E, Vrachnos DM,

Papailia S and Vittas S: Gene-diet interactions in diabetes

mellitus: Current insights and the potential of personalized

nutrition. Genes (Basel). 16(578)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S,

Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, McGowan BM, Rosenstock J, Tran

MTD, Wadden TA, et al: Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with

overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 384:989–1002. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|