Introduction

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory syndrome caused by

pathogens invading an organism, often resulting in organ

dysfunction (1). It has been

reported that the annual global incidence of sepsis ranges from

276-678 cases/100,000 population (2). Severe cases of sepsis can present as

septic cardiomyopathy (SCM), which is defined as sepsis combined

with cardiac dysfunction (3). Due

to the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria, the reported incidence

rates of SCM vary widely (4);

however, a recent meta-analysis estimated the incidence of SCM in

sepsis patients at ~20% (5).

Patients with sepsis-induced cardiovascular disease usually have a

poor prognosis, and according to previous studies, the mortality

rate of patients with SCM can be as high as 70% (6), presenting a notable challenge for the

healthcare community. The current low diagnostic rate and poor

therapeutic efficacy of SCM highlight the need to improve

diagnostic efficiency and explore novel therapeutic options.

The pathogenesis of sepsis has been partially

explored and is considered to mainly involve the inflammatory

response, mitochondrial damage, altered nitric oxide metabolism,

apoptosis, ferroptosis and autonomic dysregulation (7-10).

However, effective treatments for sepsis are still lacking;

therefore, exploring the pathogenesis of SCM and developing

targeted therapies would markedly improve the prognosis of patients

with sepsis. Programmed cell death includes apoptosis, pyroptosis

and necroptosis; in addition, Malireddi et al (11) proposed a novel type of programmed

cell death called PANoptosis, which is mainly regulated by the

PANoptosome complex. PANoptosis is characterized by three

simultaneous types of cell death, including apoptosis, pyroptosis

and necroptosis, and cannot be replaced with any single type of

cell death (12). PANoptosis is

associated with numerous conditions such as infectious and

autoimmune diseases (13), and in

sepsis-induced respiratory disease, it has been shown that

PANoptosis is involved in sepsis-induced lung injury (14). In sepsis-induced neurological

disorders, the inhibition of PANoptosis via the downregulation of

toll-like receptor 9 leads to improved survival in rats with

sepsis-associated encephalopathy (15). These studies suggest a strong

association between sepsis-related complications and PANoptosis.

However, there are few studies on PANoptosis and sepsis-induced

myocardial injury.

In the present study, gene expression profiles of

the appropriate samples from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)

database were analyzed. The differentially expressed

PANoptosis-related genes (PRGs) between the SCM group and the

control group were subsequently identified. Additionally, three

machine learning algorithms were employed to identify key genes,

and experimental validation was performed. This study aimed to

provide new insights into the diagnosis and treatment of SCM.

Materials and methods

Data sources

Gene expression datasets (GSE79962, GSE53007 and

GSE142615) (16-18)

were downloaded from the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The GSE79962

dataset (GPL6244 platform) contains 31 available myocardial tissue

samples (20 patients with SCM and 11 healthy controls). The

GSE142615 dataset (GPL27951 platform) contains eight available

myocardial tissue samples [four lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced

myocardial injury mice and four healthy mice]. The GSE53007 dataset

(GPL6885 platform) also contains eight available heart tissue

samples (four SCM mice and four healthy mice).

Identification of differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) and differentially expressed PRGs

Datasets were screened for DEGs using the ‘limma’ R

package (version 3.56.2) (19).

DEGs were defined as genes with adjusted P<0.05 and a fold

change (FC) of |log2FC|>1. For visual presentation of the

results, volcano maps and heatmaps were plotted using the ggplot2

package (version 3.5.1) (20) and

pheatmap package (version 1.0.12) (21) of R, respectively. A total of 902

PRGs were derived from published literature (22); subsequently, the PRGs were

intersected with DEGs to obtain differentially expressed PRGs. Venn

diagrams were created using an online tool (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

Functional enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) (23) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) (24) enrichment

analyses of the differentially expressed PRGs were performed using

the ‘clusterProfiler’ R package (25). GO analysis aimed to identify the

cellular component (CC), molecular function (MF) and biological

process (BP) terms enriched by the differentially expressed PRGs.

The KEGG analysis sought to determine the pathways in which the

differentially expressed PRGs were enriched. The results of the

enrichment analyses are presented in columns and bubble charts.

Identification of key genes by machine

learning and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

analysis

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

(LASSO) regression, support vector machine-recursive feature

elimination (SVM-RFE) and random forest (RF) methods are often used

in bioinformatics to screen characteristic genes (26,27).

These three machine learning algorithms were used to screen key

genes in the differentially expressed PRGs. The advantage of LASSO

is that it can automatically perform feature selection by reducing

the coefficients of unimportant features to zero. This method

eliminates most of the irrelevant or low-impact genes, leaving only

a few genes with nonzero coefficients. The ‘glmnet’ R package

(version 4.1-8) (28) was used to

perform the LASSO regression analysis, and the α parameter was set

to 1 and a 10-fold cross-validation scheme was used. The SVM-RFE

algorithm is a commonly used feature selection method that combines

the advantages of SVM and RFE. SVM is mainly used for solving

classification problems and enables the separation of samples from

different classes, and the RFE algorithm removes unimportant

features in each iteration. The SVM-RFE analysis was performed

using the ‘e1071’ (version 1.7-14) (29), ‘caret’ (version 6.0-94) (30) and ‘kernlab’ (version 0.9-32)

(31) R packages; a 10-fold

cross-validation scheme was used. The RF is used to build a more

robust model by combining multiple simple decision trees; this

algorithm can markedly reduce the risk of overfitting. The

‘randomForest’ package (version 4.7-1.1) (32) was used for RF analysis, with the

ntree parameter set to 500, and genes with MeanDecreaseGini >2

were screened. The key genes were obtained via intersection

analysis on the basis of the results of LASSO regression, SVM-RFE

and RF. ROC curves were generated via the ‘pROC’ R package (version

1.18.5) (33) to analyze the

diagnostic value of key genes for SCM.

Immune infiltration analysis

CIBERSORT (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/) was used for immune

infiltration analysis; it is a widely used computational method

(34,35) for immunological studies that

enables analysis of the proportions of different immune cell

subpopulations in tissues using gene expression data. The matrix

data of the related samples in the GSE79962 dataset were uploaded

to CIBERSORTx, with LM22 used as the feature matrix (36). The results from the website

provided the proportions of 22 immune cell types in each sample,

with the results presented in a bar chart. The associations between

the expression of key PRGs and 22 immune cell types were explored

using Spearman's correlation analysis, with the results presented

in lollipop charts.

Validation of key genes in the

external dataset

For the validation set, the GSE53007 and GSE142615

datasets were combined. The expression of key PRGs was studied in

the validation set, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to

determine whether the key genes were differentially expressed

between the SCM group and the control group. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The

results are presented in box plots.

Single-gene gene set enrichment

analysis (GSEA)

To investigate the effects of the expression of key

genes on pathways, single-gene GSEA was performed. Patients with

sepsis in the GSE79962 dataset were categorized into high- and

low-expression groups based on the median expression level of the

key PRGs. By comparing the transcriptomic profiles between the

high- and low-expression groups and performing enrichment analysis,

signaling pathways that are associated with changes in the

expression of the key gene were identified; this approach has been

applied in multiple previous studies (37-39).

The criterion for significant enrichment was defined as q<0.05,

adjusted P<0.05 and |normalized enrichment score|>1.

Single-gene GSEA was performed using the ‘clusterProfiler’ R

package (25), with part of the

results presented.

Construction of competitive endogenous

RNA (ceRNA) regulatory networks

A ceRNA regulatory network was constructed based on

the key genes. The miRanda (40),

miRDB (41), miRWalk (42) and TargetScan (43) databases were used to predict

microRNAs (miRNAs). The miRNAs that appeared simultaneously in the

aforementioned databases were used to construct the ceRNA

regulatory network. The miRNAs were matched using the spongeScan

(44) database to identify the

corresponding long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). Cytoscape (version

3.9.1; https://cytoscape.org/) was used to

visualize the ceRNA regulatory network.

Prediction of potential drugs

Currently, there are limited therapeutic drugs

available for the treatment of SCM; therefore, the drugs associated

with key PRGs were accessed through the Drug-Gene Interaction

Database (DGIDB; https://dgidb.org/). The results were

visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.9.1).

Cell culture and treatment

HL-1 cells (Procell Life Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) were cultured in minimum essential medium (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (Cellmax) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics (NCM

Biotech) in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37˚C. To mimic

SCM, cardiomyocytes were treated with 10 µg/ml LPS (MilliporeSigma)

for 12 h at 37˚C.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

(qPCR)

Total RNA from cells was extracted using RNA

extraction solution (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA synthesis was

performed using a reverse transcription kit (TransGen Biotech Co.,

Ltd.). The conditions for reverse transcription were 42˚C for 15

min and then 85˚C for 5 sec. The qPCR was carried out on a Roche

Light Cycler 96 Real-Time System (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) using

PerfectStart® Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech Co.,

Ltd.). The qPCR was performed with an initial denaturation at 94˚C

for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 5 sec at 94˚C and 30 sec at

60˚C. The following primers were used: GADD45B forward,

5'-TGCCTCCTGGTCACGAACTG-3' and reverse,

5'-CCATTGGTTATTGCCTCTGCTCTC-3'; RIPK2 forward,

5'-TCGTGTTCCTTGGCTGTAATAAGTC-3' and reverse,

5'-CATCTGGCTCACAATGGCTTCC-3'; and β-actin forward,

5'-CTATTGGCAACGAGCGGTTCC-3' and reverse,

5'-GCACTGTGTTGGCATAGAGGTC-3'. The relative gene expression was

calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method

(45).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of two data groups was conducted utilizing

either Student's t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as

appropriate. R software (version 4.3.1; RStudio, Inc.) and GraphPad

Prism version 9 (Dotmatics) were used for analysis and plotting.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

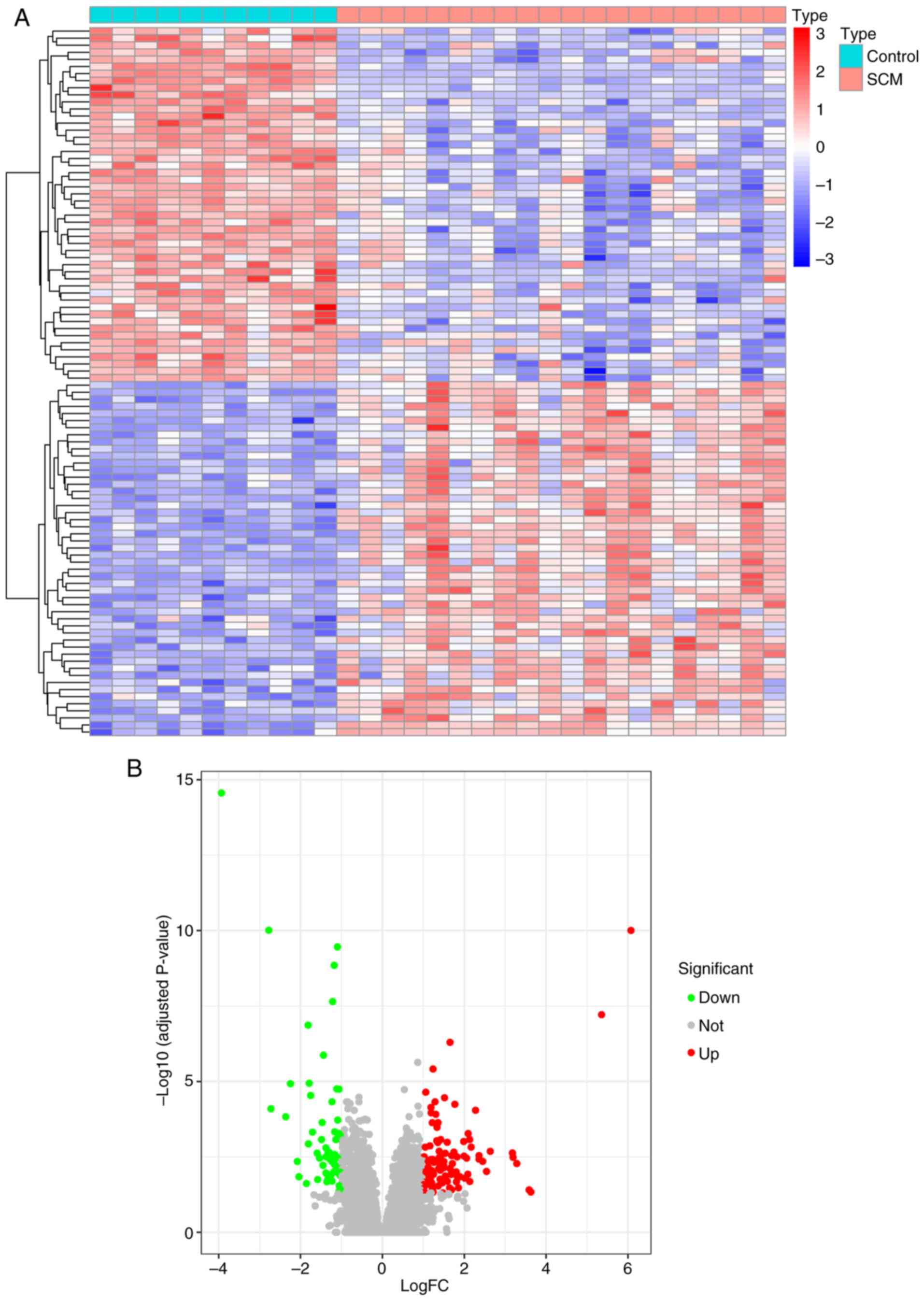

Screening of DEGs

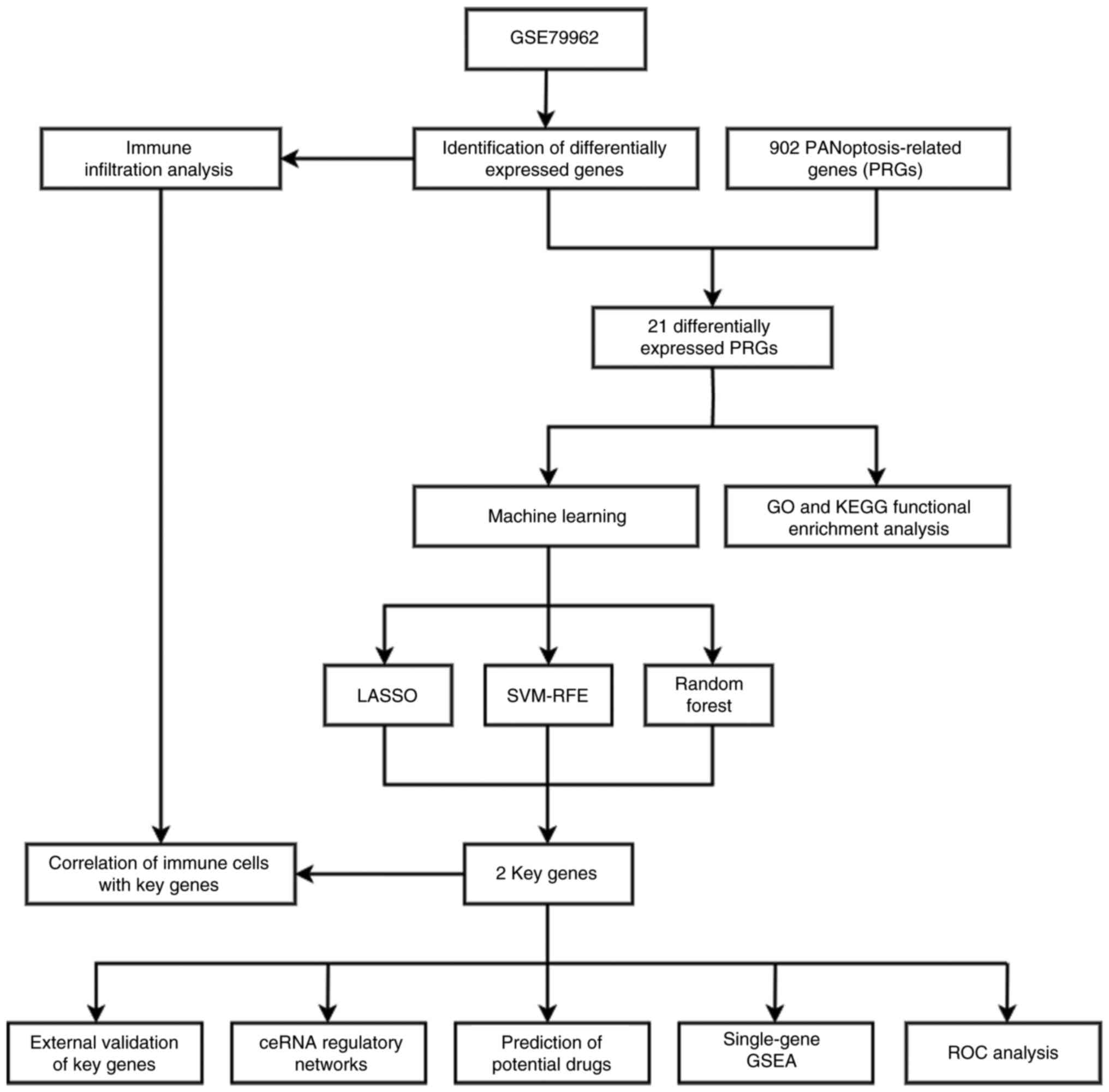

The flowchart of the present study is shown in

Fig. 1. A total of 31 samples from

the GSE79962 dataset were included in the present study. The SCM

group included 20 samples, and the control group included 11

samples. A total of 157 DEGs, including 59 downregulated genes and

98 upregulated genes, were obtained using the ‘limma’ R package.

DEGs are presented in heatmaps (Fig.

2A) and volcano plots (Fig.

2B), and the top 50 differentially expressed up- and

downregulated genes are shown in the heatmap.

Differentially expressed PRGs and

GO/KEGG enrichment analysis

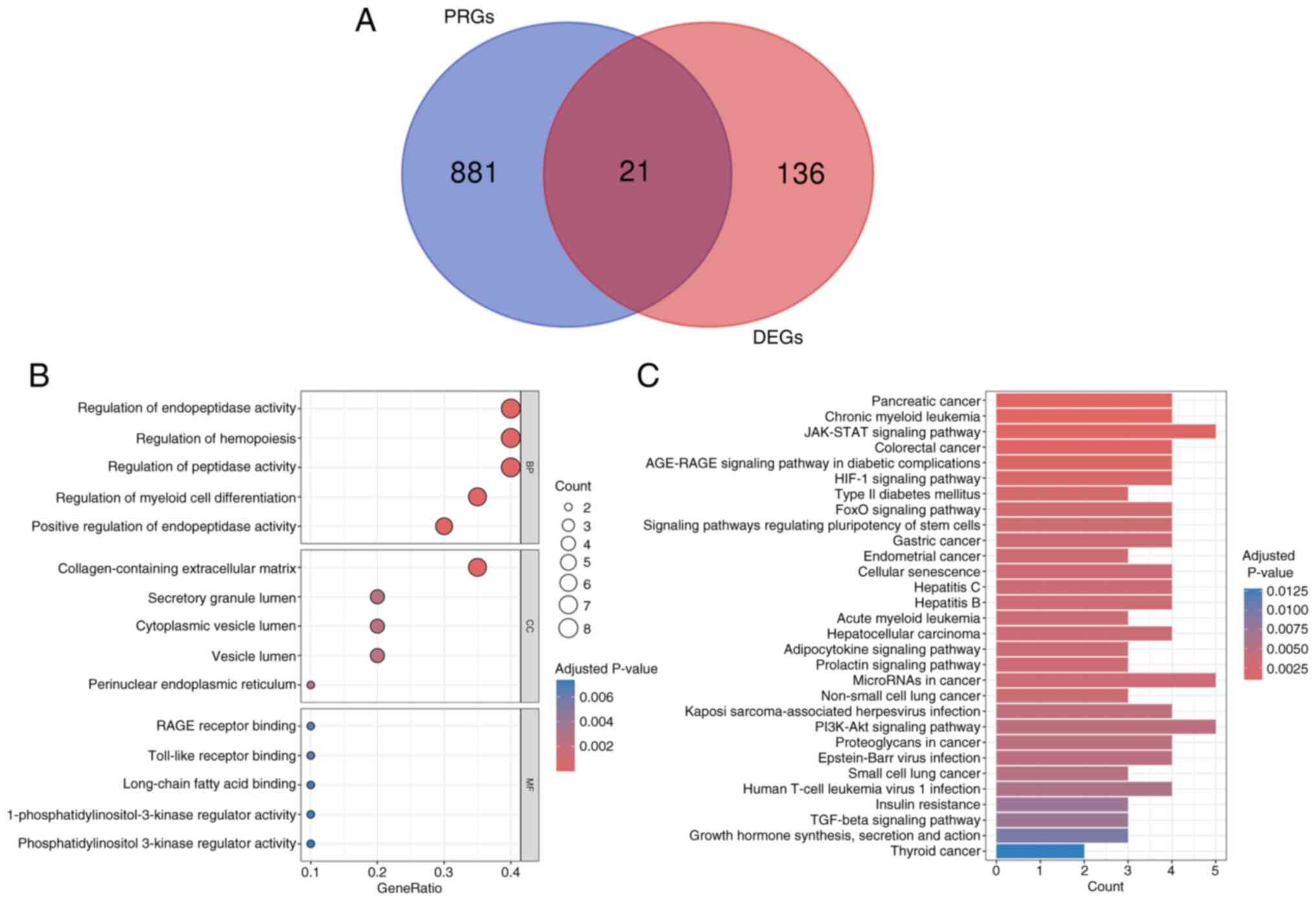

A total of 21 differentially expressed PRGs were

identified by intersecting 157 DEGs with 902 PRGs, and the results

are displayed in the Venn diagram (Fig. 3A). To investigate the potential

biological functions of the differentially expressed PRGs, these 21

genes were subjected to GO and KEGG enrichment analyses. The top

five BPs, CCs and MFs were shown using a bubble diagram (Fig. 3B). The top 5 relevant BP terms were

‘regulation of endopeptidase activity’, ‘regulation of

hemopoiesis’, ‘regulation of peptidase activity’, ‘regulation of

myeloid cell differentiation’ and ‘positive regulation of

endopeptidase activity’. The top 5 relevant CC terms were

‘collagen-containing extracellular matrix’, ‘secretory granule

lumen’, ‘cytoplasmic vesicle lumen’, ‘vesicle lumen’ and

‘perinuclear endoplasmic reticulum’. The top 5 relevant MF terms

were ‘RAGE receptor binding’, ‘Toll-like receptor binding’,

‘long-chain fatty acid binding’, ‘1-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

regulator activity’ and ‘phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulator

activity’. The top 30 KEGG pathways are presented using a bar plot,

and these KEGG pathways included ‘JAK-STAT signaling pathway’,

‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’ and ‘HIF-1 signaling pathway’

(Fig. 3C).

Identification of key genes and

diagnostic value assessment

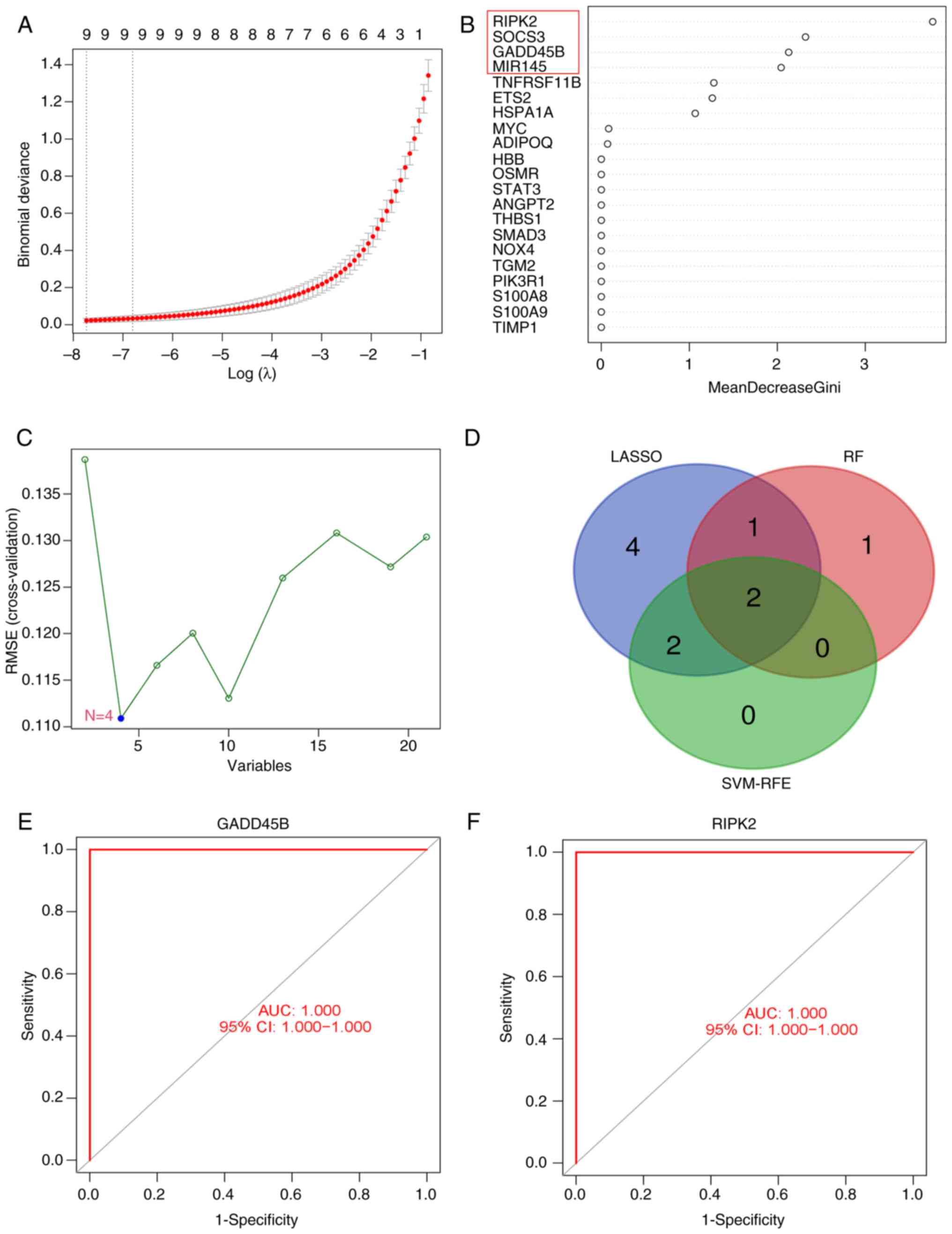

To further mine key genes for SCM, three machine

learning algorithms were used to evaluate the 21 differentially

expressed PRGs: Nine candidate key genes were screened by LASSO

regression analysis (Fig. 4A); the

RF algorithm identified four candidate key genes with importance

scores >2 (Fig. 4B); and the

SVM-RFE algorithm identified four candidate key genes (Fig. 4C). Two key genes were identified on

the basis of the results of three algorithms (Fig. 4D), and these genes were GADD45B and

RIPK2. These findings suggested that GADD45B and RIPK2 may play

important roles in SCM. Additionally, to explore the diagnostic

ability of these two key genes for SCM, ROC curves were plotted and

the AUC values of GADD45B and RIPK2 were both 1.00 (Fig. 4E and F). The results indicated that both key

genes had superior diagnostic abilities.

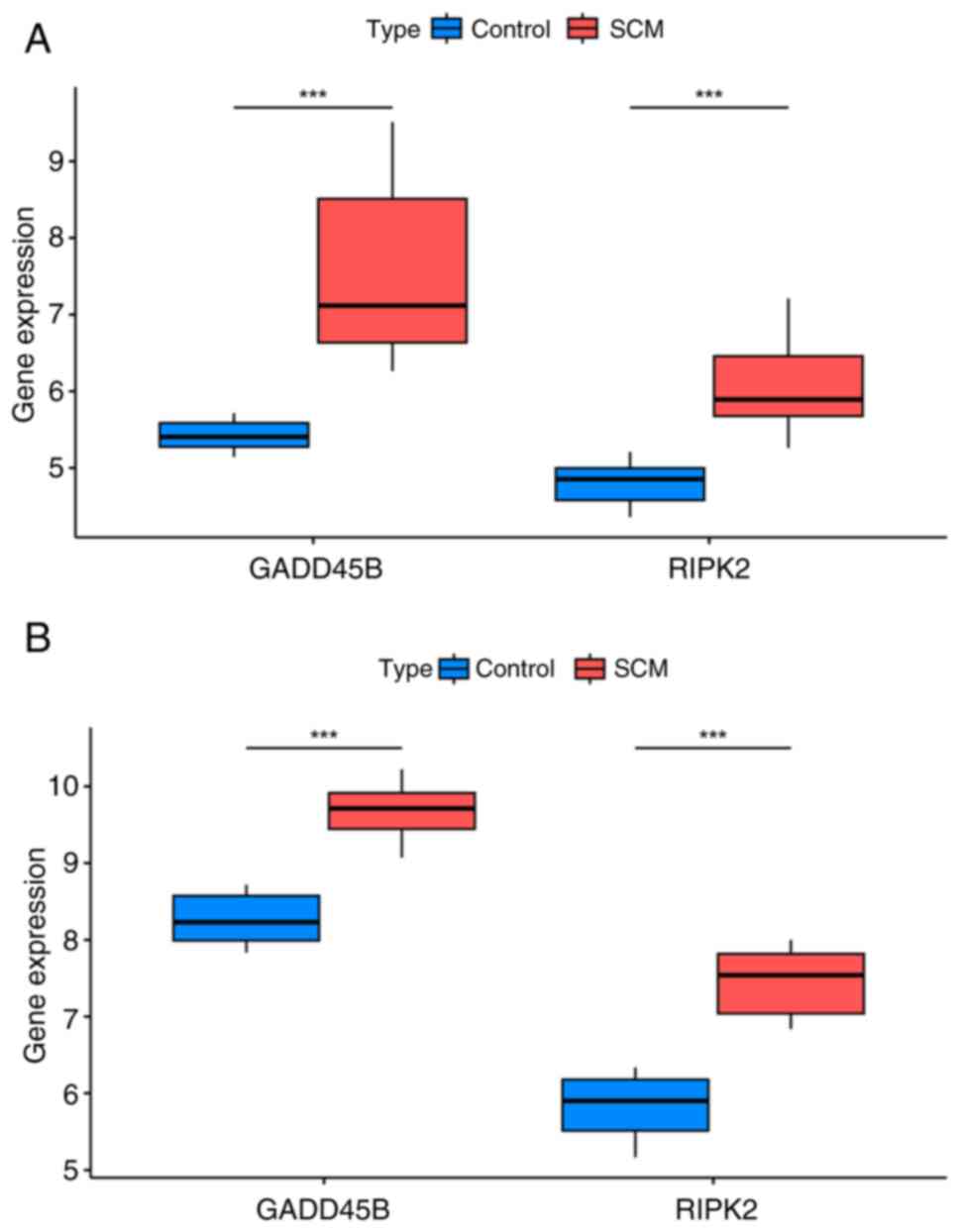

External dataset validation of GADD45B

and RIPK2 expression

In the GSE79962 dataset, the levels of GADD45B and

RIPK2 were significantly elevated in the SCM group (Fig. 5A); in the validation set, GADD45B

with RIPK2 remained highly expressed in the SCM group (Fig. 5B). The aforementioned results were

consistent and all the differences were statistically significant.

These results suggested that the expression of GADD45B and RIPK2 is

elevated in the myocardial tissues of both SCM patients and SCM

mice compared with their respective controls.

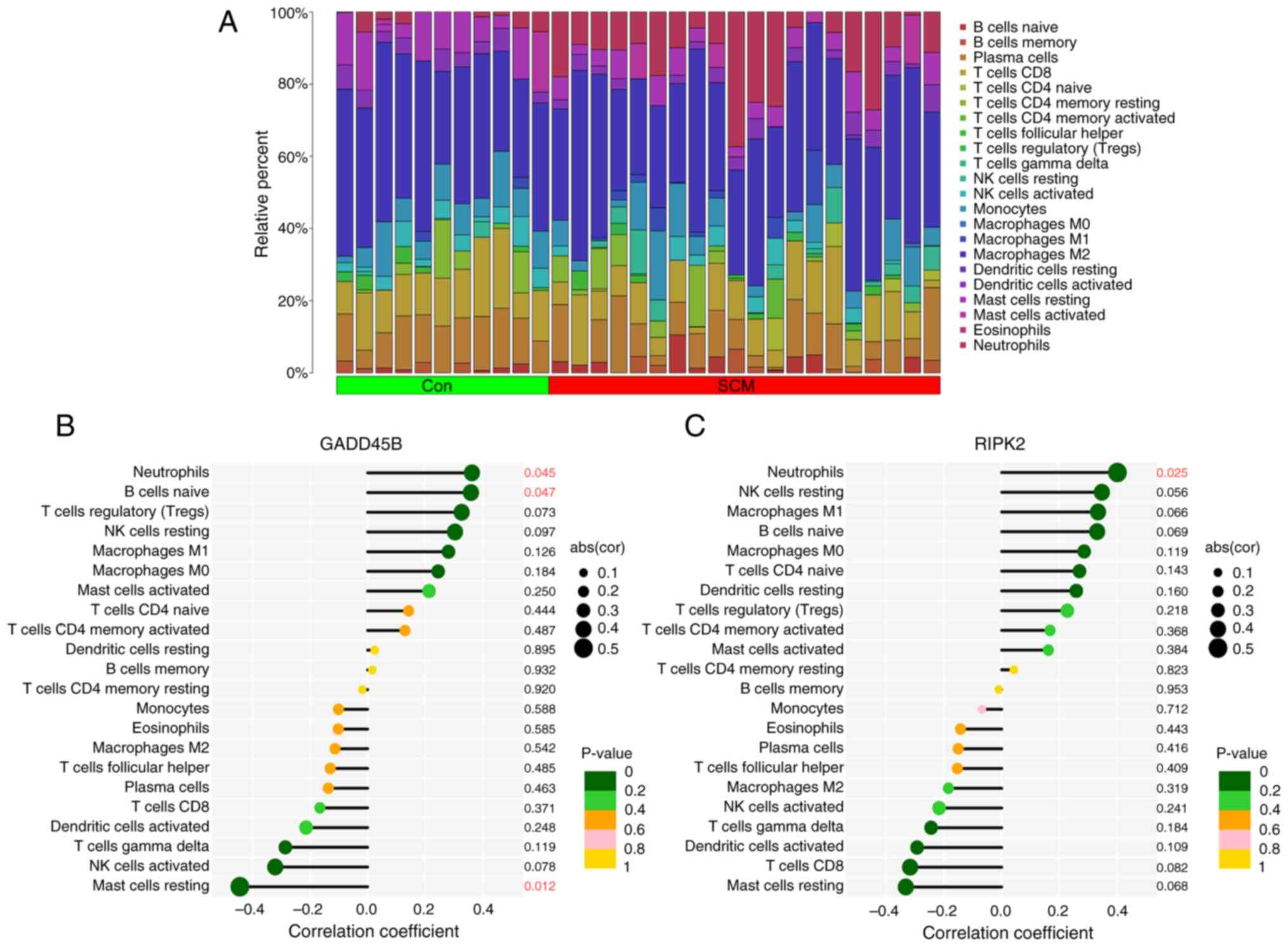

Assessment of immune cell infiltration

and correlation of key genes with immune cells

The CIBERSORT algorithm was used to analyze the

relative abundance of different immune cell types across the 31

samples in the GSE79962 dataset. The bar-plot diagram shows the

proportions of 22 immune cell types in each sample (Fig. 6A). The expression level of GADD45B

was positively correlated with the proportions of naive B cells and

neutrophils; conversely, the expression level of GADD45B was

inversely related to the proportion of mast cells resting (Fig. 6B). The expression level of RIPK2

showed a positive relationship with the proportion of neutrophils

(Fig. 6C). The findings of the

immune infiltration analysis indicated that RIPK2 and GADD45B may

be involved in regulating immune cell infiltration in SCM.

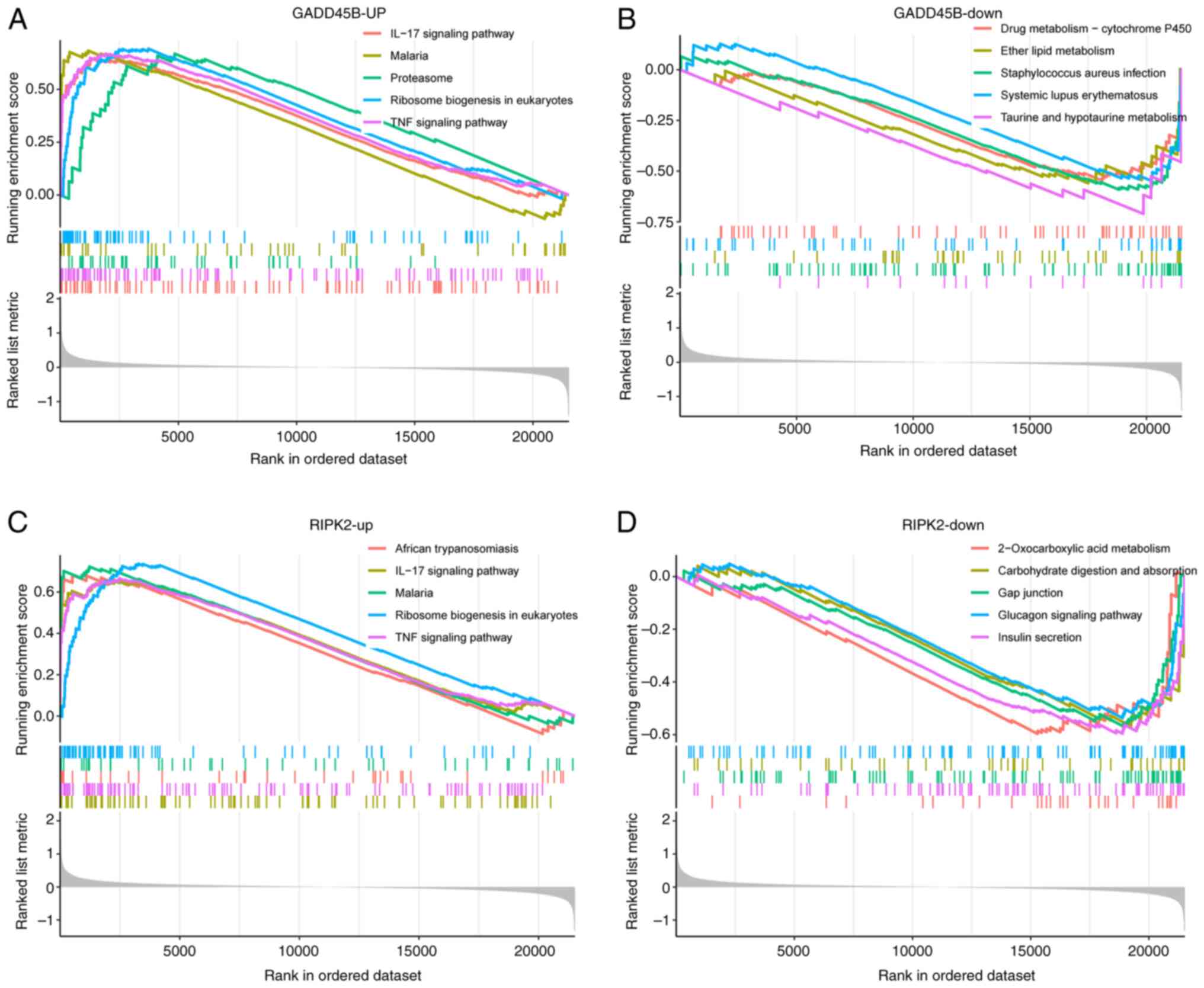

Single-gene GSEA analysis of GADD45B

and RIPK2

To further explore the possible molecular mechanisms

associated with key PRGs in SCM, single-gene GSEA was conducted.

The findings indicated that pathways enriched in the high GADD45B

expression group were predominantly ‘IL-17 signaling pathway’,

‘malaria’, ‘proteasome’, ‘ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes’ and

‘TNF signaling pathway’ (Fig. 7A).

Pathways enriched in the low GADD45B expression group were

primarily the ‘drug metabolism-cytochrome P450’, ‘ether lipid

metabolism’, ‘Staphylococcus aureus infection’, ‘systemic

lupus erythematosus’ and ‘taurine and hypotaurine metabolism’

(Fig. 7B). In addition, pathways

enriched in the high RIPK2 expression group were mainly ‘African

trypanosomiasis’, ‘IL-17 signaling pathway’, ‘malaria’, ‘ribosome

biogenesis in eukaryotes’ and ‘TNF signaling pathway’ (Fig. 7C). On the other hand, pathways

enriched in the low RIPK2 expression group were mainly

‘2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism’, ‘carbohydrate digestion and

absorption’, ‘gap junction’, ‘glucagon signaling pathway’ and

‘insulin secretion’ (Fig. 7D).

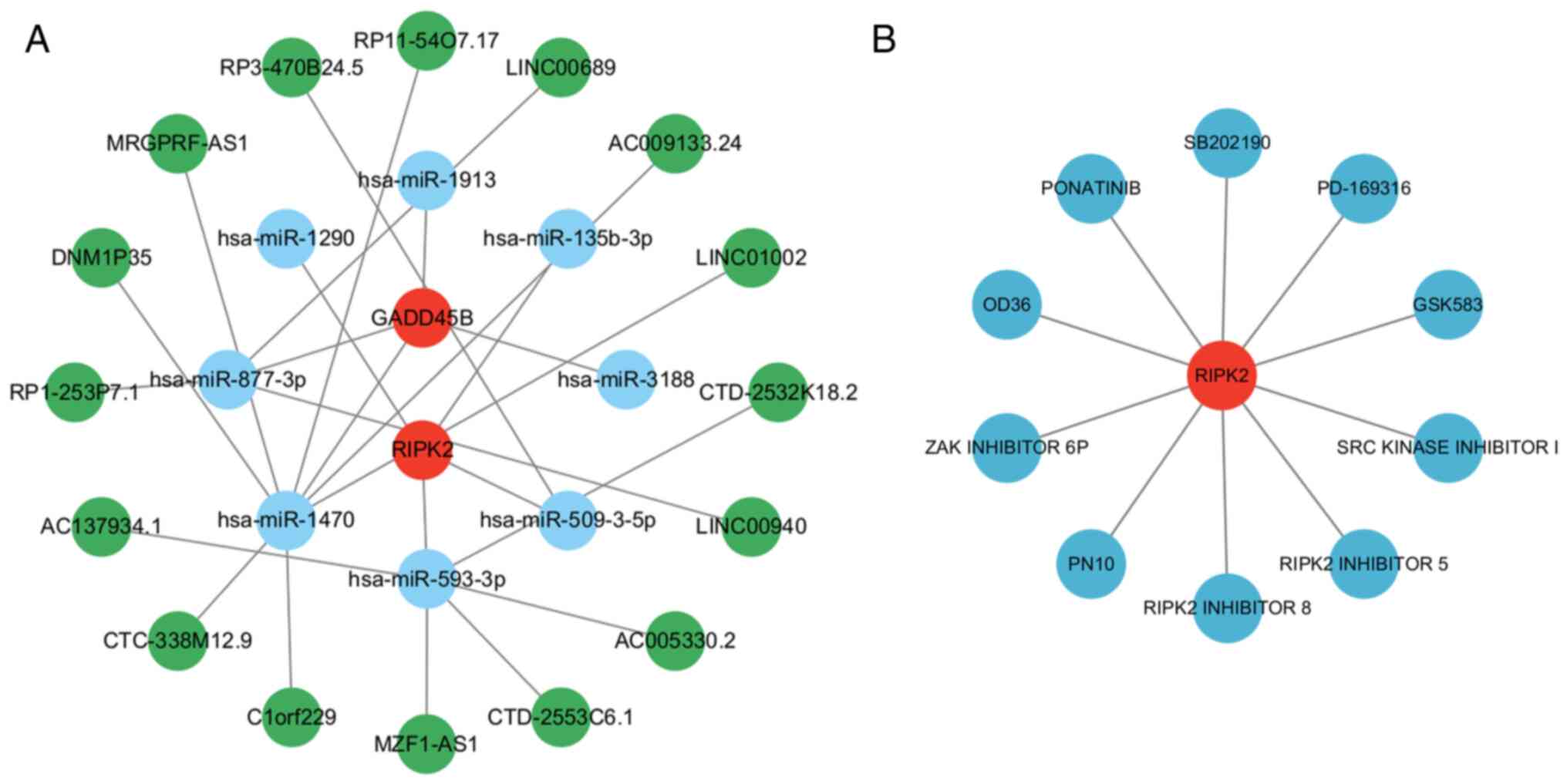

GADD45B- and RIPK2-based ceRNA network

and potential therapeutic agents for SCM

To further explore gene functions and regulatory

mechanisms, a ceRNA regulatory network was constructed. Eight

miRNAs and 16 lncRNAs were found to be associated with the key

genes and were visualized using Cytoscape (Fig. 8A). To explore potential therapeutic

agents for SCM, the DGIDB database was used to obtain drugs

associated with the key genes; the results showed that 10 drugs or

molecular compounds were related to RIPK2, whereas no drugs related

to GADD45B were found (Fig. 8B).

Among the 10 drugs or molecular compounds related to RIPK2, the

five with the highest interaction scores were OD36, SRC kinase

inhibitor I, RIPK2 inhibitor 8, GSK583 and RIPK2 inhibitor 5.

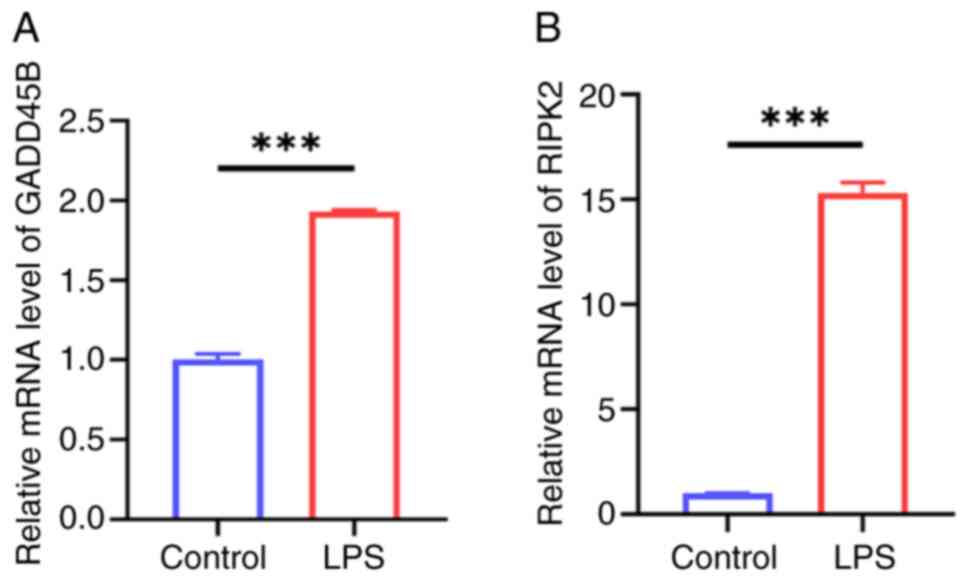

Experimental validation of GADD45B and

RIPK2 expression

The LPS-induced HL-1 cell injury model was used to

explore the expression levels of the key PRGs. As hypothesized, the

mRNA expression levels of GADD45B and RIPK2 were significantly

elevated in the LPS-induced HL-1 cell injury group compared with

the control group (Fig. 9A and

B). This was consistent with the

previous bioinformatics analyses.

Discussion

Previously published data have shown that the

prevalence of sepsis is increasing worldwide (46). Sepsis typically leads to myocardial

damage and the mortality rate of septic patients with cardiac

dysfunction is notably high. The illness compromises both the

physical and mental well-being of the patient, while simultaneously

imposing a notable strain on families and society, and there are

currently limited treatment options available for patients with

SCM. Research indicates that the development of SCM involves

various forms of cell death, including apoptosis, autophagy and

ferroptosis (47,48). To the best of our knowledge, there

are few studies focused on the role of PANoptosis, a new type of

programmed cell death, and its association in SCM. In the present

study, two key PRGs potentially associated with the progression of

SCM were identified using bioinformatics analysis and machine

learning techniques. The findings suggested that PANoptosis may be

associated with the development of SCM.

In the present study, 157 DEGs were screened in the

SCM group compared with the control group, and 21 differentially

expressed PRGs were obtained by intersecting these 157 DEGs with

PANoptosis-related genes. The functional enrichment analysis

indicated that the 21 differentially expressed PRGs were involved

primarily in the ‘regulation of endopeptidase activity’, ‘toll-like

receptor binding’, ‘JAK-STAT signaling pathway’ and ‘PI3K-Akt

signaling pathway’. According to previous studies, these enrichment

results are strongly associated with SCM. For instance, it has been

shown that apoptosis and inflammation are improved by regulating

JAK2/STAT6 in an LPS-induced myocardial injury model (10). Another study demonstrated that

modulation of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway can alleviate

LPS-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis (49). In addition, LASSO regression, RF

and SVM-RFE were used to further screen 2 key PRGs, GADD45B and

RIPK2, involved in the pathogenesis of SCM. The AUC values for both

key genes were 1, suggesting that both GADD45B and RIPK2 have high

diagnostic value.

GADD45B belongs to the GADD45 family, a group that

plays a role in regulating apoptosis and cellular proliferation

(50), and previous studies on

GADD45B have focused on tumors, stroke and kidney injury (50-52).

In cardiovascular diseases, ischemia/hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte

apoptosis can be markedly attenuated by downregulation of GADD45B,

suggesting that GADD45B plays a key role in cardiomyocyte apoptosis

(53). Additionally, earlier

research has reported elevated expression of GADD45B in the

myocardium of diabetic mice compared with controls, with further

increases observed in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in diabetic

mice (54). In the present study,

the expression level of GADD45B was elevated in the SCM group, and

it was also found to be elevated in the LPS-induced cardiomyocyte

model. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet

identified a role for GADD45B in SCM and further research is

required to elucidate its role.

RIPK2 is a member of the RIP family, of which

members of the family have been reported to have serine/threonine

kinase activity; additionally, RIPK2 has tyrosine kinase activity

(55). Previous studies have found

that RIPK2 is involved mainly in gene transcription regulation,

inflammation, autophagy and apoptosis (56). Current studies on RIPK2 are related

mainly to tumors, autoimmune diseases and inflammation-related

diseases (57-59),

and there are fewer studies related to RIPK2 and cardiovascular

disease. One study showed that RIPK2 knockdown ameliorated cardiac

hypertrophy in pressure-overloaded mice (60); this finding highlights that RIPK2

could serve as a promising target for addressing myocardial

hypertrophy or heart failure. A different investigation revealed

that RIPK2 deficiency in a mouse model of myocardial ischemia led

to a notable decline in cardiac function (61); therefore, these findings suggest

that RIPK2 is expected to be a new effective target in ischemic

heart disease. In the present study, it was observed that RIPK2

expression was elevated in SCM, and as RIPK2 is closely related to

inflammation and apoptosis, it was hypothesized that RIPK2 may be

associated with the development of SCM.

An immune infiltration analysis was performed, which

revealed that the proportion of neutrophils in the SCM group was

notably greater than that in the control group. A previous study

has also demonstrated marked neutrophil infiltration in the

myocardium of SCM mice (62).

Neutrophils play a dual role in sepsis, and while they effectively

eliminate pathogens, overactivated neutrophils can also exacerbate

tissue damage (63). During

sepsis, neutrophils release large amounts of reactive oxygen

species and proteolytic enzymes, thereby exacerbating the

inflammatory response; therefore, inhibiting excessive neutrophil

infiltration is a potential therapeutic approach for SCM.

Pretreatment with the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 notably

suppressed neutrophil infiltration in the myocardium and reduced

the expression of myocardial inflammatory cytokines after cecal

ligation and puncture in mice (64). Additionally, a correlation analysis

was conducted between key genes and 22 types of immune cells, and

the findings revealed a significant correlation between the

expression of both key genes and the percentage of neutrophils. A

more detailed exploration of the connections between key PRGs and

immune cells may be critical for the treatment of SCM.

To understand the related pathways and molecular

functions of key genes, single-gene GSEA was performed in the

current study. The results revealed that both GADD45B and RIPK2

show a significant correlation with the upregulation of gene sets

related to the ‘IL-17 signaling pathway’ and ‘TNF signaling

pathway’. These findings are consistent with previous research; for

instance, in a mouse model of acute pancreatitis induced by

hypertriglyceridemia, knockdown of GADD45B markedly attenuated the

serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α (65). In another study, it was found that

RIPK2 knockdown could enhance the cytosolic level of IKBα, block

p65 nuclear translocation and inhibit the expression of TNF-α and

IL-17 in an ovalbumin-induced mouse asthma model (66). These studies suggest that knockdown

of GADD45B and RIPK2 can suppress the progression of certain

diseases by inhibiting inflammation. The pathogenesis of SCM is

closely related to excessive inflammatory responses, and in SCM,

both the TNF-α pathway and the IL-17 pathway play important roles

in the inflammatory response (67,68),

and their synergistic action can amplify the inflammatory reaction

(69). This may further exacerbate

the inflammatory response in cardiomyocytes; therefore, an

investigation into the roles and mechanisms of GADD45B and RIPK2 in

inflammation will facilitate the development of novel therapeutic

approaches for SCM.

In the present study, a ceRNA regulatory network was

constructed that comprises two mRNAs, eight miRNAs and 16 lncRNAs.

It has been suggested that miR-1290 may be associated with sepsis

and associated lung injury (70),

whereas another study on miR-1290 showed that increasing the level

of miR-1290 in cardiomyocytes reduced apoptosis under hypoxic

conditions (71). The ceRNA

regulatory network provides promising targets for the treatment of

SCM, but further experimental studies are required. Additionally,

drugs or chemical compounds associated with key genes were obtained

through the DGIDB database. The results showed that there were 10

drugs or chemical compounds related to RIPK2, whereas no drugs or

chemical compounds related to GADD45B were found. Among these 10

drugs or chemical compounds, OD36, a RIPK2 inhibitor, has been

reported to reduce neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltration in the

peritoneal cavity of mice with peritonitis (72). However, to the best of our

knowledge, no studies have reported the application of OD36 in SCM.

This finding indicates that there is still notable room for

improvement in the treatment of SCM.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was

the first to explore the role of PANoptosis in SCM, which provides

a theoretical basis for subsequent related studies. However, there

are certain limitations. First, a small sample size was used and

more samples need to be included in subsequent studies. Second, it

is essential to conduct both in vivo and in vitro

experiments to confirm the function of key PRGs in SCM. Finally,

due to the lack of complete information, it was not possible to

compare the baseline populations between the SCM group and the

healthy control group. In the future, it is the aim to explore the

pathogenesis of SCM further, hoping to provide more options for SCM

treatment.

In conclusion, in the present study, two key PRGs,

RIPK2 and GADD45B, were screened through bioinformatics and machine

learning. Both genes demonstrated good diagnostic capabilities for

SCM. In addition, these genes may play a role in SCM by regulating

certain immune cells. Finally, a novel theoretical foundation for

the treatment of SCM was established by constructing a ceRNA

regulatory network and a drug-gene interaction network.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Data related to this study are available from the

GEO database, including GSE79962, GSE53007 and GSE142615

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

The data generated in the present study may be requested from the

corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QT, ZZ and YY contributed to the overall design of

the research. PY and JZ collected the relevant data. PY and YY

performed the data analysis. YY and JZ conducted the experiments.

YY and JZ wrote the original draft. QT and ZZ edited the

manuscript. QT, ZZ and YY revised the manuscript. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript. YY and QT confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang YY and Ning BT: Signaling pathways

and intervention therapies in sepsis. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

6(407)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Fleischmann-Struzek C and Rudd K:

Challenges of assessing the burden of sepsis. Med Klin Intensivmed

Notfmed. 118 (Suppl 2):S68–S74. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zaky A, Deem S, Bendjelid K and Treggiari

MM: Characterization of cardiac dysfunction in sepsis: An ongoing

challenge. Shock. 41:12–24. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hollenberg SM: Sepsis-associated

cardiomyopathy: Long-term prognosis, management, and

Guideline-directed medical therapy. Curr Cardiol Rep.

27(5)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hasegawa D, Ishisaka Y, Maeda T,

Prasitlumkum N, Nishida K, Dugar S and Sato R: Prevalence and

prognosis of Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and

Meta-analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 38:797–808. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Li Y, Ge S, Peng Y and Chen X:

Inflammation and cardiac dysfunction during sepsis, muscular

dystrophy, and myocarditis. Burns Trauma. 1:109–121.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Dickson K and Lehmann C: Inflammatory

response to different toxins in experimental sepsis models. Int J

Mol Sci. 20(4341)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

van der Slikke EC, Star BS, van Meurs M,

Henning RH, Moser J and Bouma HR: Sepsis is associated with

mitochondrial DNA damage and a reduced mitochondrial mass in the

kidney of patients with sepsis-AKI. Crit Care.

25(36)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Oliveira F, Assreuy J and Sordi R: The

role of nitric oxide in sepsis-associated kidney injury. Biosci

Rep. 42(BSR20220093)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Jiang L, Zhang L, Yang J, Shi H, Zhu H,

Zhai M, Lu L, Wang X, Li XY, Yu S, et al: 1-Deoxynojirimycin

attenuates septic cardiomyopathy by regulating oxidative stress,

apoptosis, and inflammation via the JAK2/STAT6 signaling pathway.

Biomed Pharmacother. 155(113648)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Malireddi RKS, Kesavardhana S and

Kanneganti TD: ZBP1 and TAK1: Master Regulators of NLRP3

Inflammasome/Pyroptosis, Apoptosis, and Necroptosis (PAN-optosis).

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 9(406)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Christgen S, Tweedell RE and Kanneganti

TD: Programming inflammatory cell death for therapy. Pharmacol

Ther. 232(108010)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhu P, Ke ZR, Chen JX, Li SJ, Ma TL and

Fan XL: Advances in mechanism and regulation of PANoptosis:

Prospects in disease treatment. Front Immunol.

14(1120034)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

He YQ, Deng JL, Zhou CC, Jiang SG, Zhang

F, Tao X and Chen WS: Ursodeoxycholic acid alleviates

sepsis-induced lung injury by blocking PANoptosis via STING

pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 125(111161)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhou R, Ying J, Qiu X, Yu L, Yue Y, Liu Q,

Shi J, Li X, Qu Y and Mu D: A new cell death program regulated by

toll-like receptor 9 through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

signaling pathway in a neonatal rat model with sepsis associated

encephalopathy. Chin Med J (Engl). 135:1474–1485. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Matkovich SJ, Al Khiami B, Efimov IR,

Evans S, Vader J, Jain A, Brownstein BH, Hotchkiss RS and Mann DL:

Widespread Down-regulation of cardiac mitochondrial and sarcomeric

genes in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 45:407–414.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Zhu H, Wu J, Li C, Zeng Z, He T, Liu X,

Wang Q, Hu X, Lu Z and Cai H: Transcriptome analysis reveals the

mechanism of pyroptosis-related genes in septic cardiomyopathy.

PeerJ. 11(e16214)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Shi Y, Zheng X, Zheng M, Wang L, Chen Y

and Shen Y: Identification of mitochondrial function-associated

lncRNAs in septic mice myocardium. J Cell Biochem. 122:53–68.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43(e47)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Gustavsson EK, Zhang D, Reynolds RH,

Garcia-Ruiz S and Ryten M: ggtranscript: An R package for the

visualization and interpretation of transcript isoforms using

ggplot2. Bioinformatics. 38:3844–3846. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhang X, Chao P, Zhang L, Xu L, Cui X,

Wang S, Wusiman M, Jiang H and Lu C: Single-cell RNA and

transcriptome sequencing profiles identify immune-associated key

genes in the development of diabetic kidney disease. Front Immunol.

14(1030198)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sun W, Li P, Wang M, Xu Y, Shen D, Zhang X

and Liu Y: Molecular characterization of PANoptosis-related genes

with features of immune dysregulation in systemic lupus

erythematosus. Clin Immunol. 253(109660)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

The Gene Ontology Consortium. The gene

ontology resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids

Res. 47:D330–D338. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kanehisa M and Goto S: KEGG: Kyoto

encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:27–30.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z,

Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, et al: clusterProfiler 4.0: A

universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation

(Camb). 2(100141)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Li Y, Yu J, Li R, Zhou H and Chang X: New

insights into the role of mitochondrial metabolic dysregulation and

immune infiltration in septic cardiomyopathy by integrated

bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Cell Mol Biol

Lett. 29(21)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chen G, Qi H, Jiang L, Sun S, Zhang J, Yu

J, Liu F, Zhang Y and Du S: Integrating single-cell RNA-Seq and

machine learning to dissect tryptophan metabolism in ulcerative

colitis. J Transl Med. 22(1121)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Engebretsen S and Bohlin J: Statistical

predictions with glmnet. Clin Epigenetics. 11(123)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang Q and Liu X: Screening of feature

genes in distinguishing different types of breast cancer using

support vector machine. Onco Targets Ther. 8:2311–2317.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kuhn M: Building predictive models in R

using the caret package. J Stat Software. 28:1–26. 2008.

|

|

31

|

Scharl T, Grü B and Leisch F: Mixtures of

regression models for time course gene expression data: Evaluation

of initialization and random effects. Bioinformatics. 26:370–377.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Alderden J, Pepper GA, Wilson A, Whitney

JD, Richardson S, Butcher R, Jo Y and Cummins MR: Predicting

pressure injury in critical care patients: A Machine-learning

model. Am J Crit Care. 27:461–468. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N,

Lisacek F, Sanchez JC and Müller M: pROC: An open-source package

for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics.

12(77)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li J, Zhang Y, Lu T, Liang R, Wu Z, Liu M,

Qin L, Chen H, Yan X, Deng S, et al: Identification of diagnostic

genes for both Alzheimer's disease and Metabolic syndrome by the

machine learning algorithm. Front Immunol.

13(1037318)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhang WY, Chen ZH, An XX, Li H, Zhang HL,

Wu SJ, Guo YQ, Zhang K, Zeng CL and Fang XM: Analysis and

validation of diagnostic biomarkers and immune cell infiltration

characteristics in pediatric sepsis by integrating bioinformatics

and machine learning. World J Pediatr. 19:1094–1103.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ,

Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M and Alizadeh AA: Robust enumeration

of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods.

12:453–457. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Peng H, Hu Q, Zhang X, Huang J, Luo S,

Zhang Y, Jiang B and Sun D: Identifying therapeutic targets and

potential drugs for diabetic retinopathy: Focus on oxidative stress

and immune infiltration. J Inflamm Res. 18:2205–2227.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zheng Z, Li K, Yang Z, Wang X, Shen C,

Zhang Y, Lu H, Yin Z, Sha M, Ye J and Zhu L: Transcriptomic

analysis reveals molecular characterization and immune landscape of

PANoptosis-related genes in atherosclerosis. Inflamm Res.

73:961–678. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Huang X, Liu J and Huang W: Identification

of S100A8 as a common diagnostic biomarkers and exploring potential

pathogenesis for osteoarthritis and metabolic syndrome. Front

Immunol. 14(1185275)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T,

Sander C and Marks DS: Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol.

2(e363)2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Chen Y and Wang X: miRDB: An online

database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucleic

Acids Res. 48:D127–D131. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Sticht C, De La Torre C, Parveen A and

Gretz N: miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA

binding sites. PLoS One. 13(e0206239)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Lewis BP, Burge CB and Bartel DP:

Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that

thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 120:15–20.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Furió-Tarí P, Tarazona S, Gabaldón T,

Enright AJ and Conesa A: spongeScan: A web for detecting microRNA

binding elements in lncRNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res.

44:W176–W180. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Deutschman CS and Tracey KJ: Sepsis:

Current dogma and new perspectives. Immunity. 40:463–475.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Lu JS, Wang JH, Han K and Li N: Nicorandil

regulates ferroptosis and mitigates septic cardiomyopathy via

TLR4/SLC7A11 signaling pathway. Inflammation. 47:975–988.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Yuan X, Chen G, Guo D, Xu L and Gu Y:

Polydatin alleviates septic myocardial injury by promoting

SIRT6-Mediated autophagy. Inflammation. 43:785–795. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Han X, Liu X, Zhao X, Wang X, Sun Y, Qu C,

Liang J and Yang B: Dapagliflozin ameliorates sepsis-induced heart

injury by inhibiting cardiomyocyte apoptosis and electrical

remodeling through the PI3K/Akt pathway. Eur J Pharmacol.

955(175930)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Salvador JM, Brown-Clay JD and Fornace AJ

Jr: Gadd45 in stress signaling, cell cycle control, and apoptosis.

Adv Exp Med Biol. 793:1–19. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Xu W, Jiang T, Shen K, Zhao D, Zhang M,

Zhu W, Liu Y and Xu C: GADD45B regulates the carcinogenesis process

of chronic atrophic gastritis and the metabolic pathways of gastric

cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 14(1224832)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Xie M, Xie R, Huang P, Yap DYH and Wu P:

GADD45A and GADD45B as novel biomarkers associated with chromatin

regulators in renal Ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Sci.

24(11304)2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kim MY, Seo EJ, Lee DH, Kim EJ, Kim HS,

Cho HY, Chung EY, Lee SH, Baik EJ, Moon CH and Jung YS: Gadd45beta

is a novel mediator of cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by

ischaemia/hypoxia. Cardiovasc Res. 87:119–126. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Sheng M, Huang Z, Pan L, Yu M, Yi C, Teng

L, He L, Gu C, Xu C and Li J: SOCS2 exacerbates myocardial injury

induced by ischemia/reperfusion in diabetic mice and H9c2 cells

through inhibiting the JAK-STAT-IGF-1 pathway. Life Sci.

188:101–109. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Tigno-Aranjuez JT, Asara JM and Abbott DW:

Inhibition of RIP2's tyrosine kinase activity limits NOD2-driven

cytokine responses. Genes Dev. 24:2666–2677. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Tian E, Zhou C, Quan S, Su C, Zhang G, Yu

Q, Li J and Zhang J: RIPK2 inhibitors for disease therapy: Current

status and perspectives. Eur J Med Chem. 259(115683)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Zhao W, Leng RX and Ye DQ: RIPK2 as a

promising druggable target for autoimmune diseases. Int

Immunopharmacol. 118(110128)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Pham AT, Ghilardi AF and Sun L: Recent

advances in the development of RIPK2 modulators for the treatment

of inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol.

14(1127722)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

You J, Wang Y, Chen H and Jin F: RIPK2: A

promising target for cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol.

14(1192970)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Zhao CH, Ma X, Guo HY, Li P and Liu HY:

RIP2 deficiency attenuates cardiac hypertrophy, inflammation and

fibrosis in pressure overload induced mice. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 493:1151–1158. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Andersson L, Scharin Täng M, Lundqvist A,

Lindbom M, Mardani I, Fogelstrand P, Shahrouki P, Redfors B,

Omerovic E, Levin M, et al: Rip2 modifies VEGF-induced signalling

and vascular permeability in myocardial ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res.

107:478–486. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Zhang J, Wang M, Ye J, Liu J, Xu Y, Wang

Z, Ye D, Zhao M and Wan J: The Anti-inflammatory mediator resolvin

E1 protects mice against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced heart injury.

Front Pharmacol. 11(203)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Brown KA, Brain SD, Pearson JD, Edgeworth

JD, Lewis SM and Treacher DF: Neutrophils in development of

multiple organ failure in sepsis. Lancet. 368:157–169.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Li J, Xiao F, Lin B, Huang Z, Wu M, Ma H,

Dou R, Song X, Wang Z, Cai C, et al: Ferrostatin-1 improves acute

sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy via inhibiting neutrophil

infiltration through impaired chemokine axis. Front Cell Dev Biol.

12(1510232)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Zhou S, Xu Y, Tu J and Zhang M: Inhibiting

NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis: A new role of GADD45B's

role in hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis. Discov

Med. 37:1105–1116. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Goh FY, Cook KL, Upton N, Tao L, Lah LC,

Leung BP and Wong WS: Receptor-interacting protein 2 gene silencing

attenuates allergic airway inflammation. J of Immunol.

191:2691–2699. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Chen XS, Wang SH, Liu CY, Gao YL, Meng XL,

Wei W, Shou ST, Liu YC and Chai YF: Losartan attenuates

sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy by regulating macrophage polarization

via TLR4-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling. Pharmacol Res.

185(106473)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Yang Y, Li XY, Li LC, Xiao J, Zhu YM, Tian

Y, Sheng YM, Chen Y, Wang JG and Jin SW: γδ T/Interleukin-17A

contributes to the effect of maresin conjugates in tissue

regeneration 1 on Lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac injury. Front

Immunol. 12(674542)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Csiszar A and Ungvari Z: Synergistic

effects of vascular IL-17 and TNFalpha may promote coronary artery

disease. Med Hypotheses. 63:696–698. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Ahmad S, Ahmed MM, Hasan PMZ, Sharma A,

Bilgrami AL, Manda K, Ishrat R and Syed MA: Identification and

validation of Potential miRNAs, as biomarkers for sepsis and

associated lung injury: A Network-based approach. Genes (Basel).

11(1327)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Wu K, Hu M, Chen Z, Xiang F, Chen G, Yan

W, Peng Q and Chen X: Asiatic acid enhances survival of human AC16

cardiomyocytes under hypoxia by upregulating miR-1290. IUBMB Life.

69:660–667. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Tigno-Aranjuez JT, Benderitter P, Rombouts

F, Deroose F, Bai X, Mattioli B, Cominelli F, Pizarro TT, Hoflack J

and Abbott DW: In vivo inhibition of RIPK2 kinase alleviates

inflammatory disease. J Biol Chem. 289:29651–2964. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|