Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most prevalent

malignant neoplasm within the gastrointestinal tract, affecting

1.36 million individuals globally and accounting for ~10% of all

cancer cases worldwide (1).

Previous research studies have indicated that colon cancer results

in ~700,000 deaths each year, ranking it fourth in

cancer-associated deaths globally (2). While chemotherapeutic agents

significantly improve outcomes in advanced-stage CRC, their

efficacy is limited to only 15-25% of the patient population

(3,4). Consequently, the identification of

novel oncogenic mechanisms is essential for enhancing our

understanding of CRC pathophysiology and for developing novel

therapeutic approaches.

In recent years, advancements in the understanding

of tumor development have highlighted the involvement of autophagy

in CRC (5,6). Autophagy, a cellular

self-degradation mechanism that maintains a consistent energy

supply, acts as a quality control system during the early stages of

tumorigenesis by preventing tissue damage and genomic instability,

thereby inhibiting cancer progression (7-9).

Within the tumor microenvironment (TME), increased autophagic flux

generally facilitates tumor cell survival and proliferation

(10). Furthermore, the concept

of 'regulated cell death' encompasses the following three distinct

mechanisms: Apoptosis, autophagy-dependent cell death and necrosis.

The induction of cell death in cancer cells is fundamental to

numerous cancer treatment strategies (11). Biological agents that trigger

autophagy-dependent cell death in cancer cells are recognized as

valuable tools in cancer therapy.

In the previous study conducted by our group,

acetylated RNA immunoprecipitation and sequencing (acRIP-seq) of

CRC was performed indicating that YWHAH drives progression via ac4C

modification (12). Subsequent

bioinformatic analysis indicated that YWHAH could modulate

autophagy and apoptosis in CRC via the MAPK/ERK axis. 14-3-3

proteins, including YWHAH, are conserved regulators found in all

eukaryotes. YWHAH can interact with target proteins, thereby

modulating protein-protein interactions and the functionality of

their ligands. This is achieved via specific mechanisms, such as

induction of structural modifications, masking or unmasking of

functional sites and alteration of the intracellular localization

of the ligands (13,14). YWHAH exhibits high specificity

for various ligands and plays significant roles in numerous

physiological processes (13,14).

In the present study, the expression levels of YWHAH

in CRC were investigated, together with its relationship with

autophagy and associated mechanisms, thereby providing insights

into CRC pathogenesis.

Materials and methods

Tissue specimens

Tissue specimens from patients with primary CRC

treated at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical

University were collected from January 2018 to December 2023. Among

the 85 patients, there were 43 males and 42 females, with ages

ranging from 35 to 69 years and a median age of 56 years. The

Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Medical University approved the use of

these clinical samples (approval no. 2023100505) and all patients

provided written informed consent. The animal experiment of the

present study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Xuzhou

Medical University (approval no. 2023110512; Xuzhou, China).

Small interfering (si)-RNA, plasmid

synthesis and transfection

The CRC cell lines LOVO and HCT116, were provided

from the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Cell Bank. LOVO and HCT116

cells were cultured in DMEM (cat. no. G4515-500ML; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.). The media were supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.),

streptomycin and penicillin (×100). YWHAH-targeting siRNAs and a

negative control (NC) were synthesized by Ruijie Bio (https://www.11467.com/shanghai/co/936727.htm). LOVO

and HCT116 cells were transfected using Endo-Free Plasmid Midi Kit

(Omega Corporation) with YWHAH siRNAs (15 pmol) or NC-siRNA at 37°C

for 24-48 h, and the effects were assessed using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). The siRNA sequences are

provided in Table SI. The

verification of knockdown and overexpression efficiency is shown in

Fig. S1, and siR-2 was selected

for subsequent studies.

RT-qPCR

The CRC cell and tissue RNAs were extracted using

TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Reverse

transcription reaction was used to convert the RNA to cDNA and

YWHAH primers synthesized by Takara Bio USA, Inc according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The cDNA was chilled for subsequent use.

qPCR was conducted on a LongGene Q2000B, starting hybridization for

2 min at 50°C and subsequent amplification for 40 cycles at 95°C

for 2 min, 95°C for 15 sec (denaturation), and 60°C for 60 sec

(extension). Primer sequences for qPCR experiments are provided in

Table SII. The

2−∆∆Cq method was applied for mRNA analysis and GAPDH

was used as the reference gene.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assays

CCK-8 assays were conducted using a kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). CRC cells (5×103

cells/well) were incubated in 96-well plates. Following reagent

treatments, the medium in each well was substituted with 100

μl CCK-8 solution (comprising 90 μl fresh medium and

10 μl CCK-8 reagent). The color reaction starts at 37°C and

was allowed to proceed for 2 h to maintain consistency. The

measurement of optical density at 450 nm was performed using a

spectrophotometer.

Flow cytometry

During Bisphenol A (BPA, 99%; MilliporeSigma)

treatment, 5×105 CRC cells per well were incubated in

6-well plates and cultured overnight; they were harvested 48 h

later and resuspended in binding buffer. The cell suspension was

incubated away from light for 20 min with Annexin V-fluorescein

isothiocyanate and propidium iodide (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Late apoptosis was subsequently assessed via flow

cytometry (CellQuestPro software; BD FACSCalibur; BD

Biosciences).

Western blotting

The proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) with protease inhibitors,

incubated at 4°C for 30 min and centrifuged (12,000 × g, 20 min, at

4°C). The protein concentration levels in the supernatants were

assessed by BCA assays and 30 μg samples were

electrophoresed using 8% SDS-PAGE gels prior to their transfer to

nitrocellulose membrane. Following blocking (5% skimmed milk) at

37°C for 30 min, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies (Table SIII)

at a ratio of 1:5,000 according to the antibody instructions (GAPDH

was diluted at a ratio of 1:5,000), followed by incubation for 30

min at room temperature with a Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L

secondary antibody (cat. no. 111-035-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch

Laboratories, Inc.), which was diluted and prepared according to

the antibody instructions. The protein bands were detected and

visualized using the ChemiDocTM XRS+ system (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) and Ultra-sensitive ECL chemiluminescence kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Image software (V.1.8.0;

National Institutes of Health) was used for densitometric

analysis.

RFP-GFP-hLC3 dual fluorescence

microscopy

A two-color fluorescence fusion protein, namely

RFP-GFP-hLC3, was used to monitor autophagy. The fusion protein

emits green and red fluorescence signals upon localization to

autophagosomes, resulting in yellow signals in merged images during

autophagy induction. The cells were plated onto glass cover slips

(1×1.5 cm) in Corning 6-well plates overnight to adhere. A total of

6 h after transfection with siRNA and plasmids, cells were

subsequently transfected with tandem RFP-GFP-hLC3 adenoviruses

[pGMLV-CMV-RFP-GFP-hLC3-Puro Lentivirus, Genomeditech (Shanghai)

Co., Ltd.] according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following

the 24-h incubation, the cells were rinsed with PBS at room

temperature, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for

10-20 min, counterstained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and

subsequently covered with coverslips. Confocal images were obtained

with the Olympus FV1000 laser scanning confocal fluorescence

microscope. Quantification of autophagosomes with green and red

fluorescence was performed using ImageJ software (V.1.8.0, National

institutes of Health) by counting the LC3 puncta per cell.

Animal models

To establish the model, the cells in the logarithmic

growth phase were selected; the old culture medium was discarded

from the dish, followed by washing once with PBS. The cells were

subsequently digested with 0.25% trypsin for 1-2 min and FBS was

added promptly to terminate digestion and prevent over-digestion.

Following low-speed centrifugation (1,000 × g, 5 min) to collect

the cells, they were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in

serum-free medium, pipetted evenly, counted and adjusted to a

density of 3×107 cells/ml with sterile PBS. A total of

24 4-6-week-old healthy SPF-grade female BALB/c-nu nude mice with

similar body weights SPF-grade female BALB/c-nu nude mice were

randomly selected from the breeding cage, and 100-μl tumor

cells (3×106 cells) were subcutaneously incubated at the

axilla of the right forelimb, with the injection site pressed with

a sterile cotton swab to terminate bleeding prior to returning the

mice to a sterilized cage for continuous feeding. The temperature

was controlled at 20-26°C, and the humidity maintained between

40-70%. For the light/dark cycle, a 12/12-h light/dark cycle was

adopted. The air exchange rate was 10-15-fold per h, and clean,

special breeders provided food and sterile drinking water. The

daily observations of the mental state of the mice, their activity,

diet and defecation were conducted, while their body weights were

measured weekly with an electronic balance and the longest and

shortest diameters of the subcutaneous xenografts were obtained

with a vernier caliper to calculate the volume using the following

formula: V (mm3)=longest diameter (mm) × shortest

diameter × shortest diameter × 0.5. This equation was used for

plotting the growth curve with time on the abscissa and tumor

volume on the ordinate (The maximum volume of a single tumor did

not exceed 1,000 mm3). A total of 5 weeks later, the

nude mice were weighed, euthanized by cervical dislocation and the

xenografts were completely removed. The excised tumors were washed

with sterile PBS, images were captured by experimental group on

white paper, weighed and the data were recorded prior to storage at

−80°C.

Transwell detect cell migration and

invasion

Cells were collected and gently blown into a fresh

complete medium to obtain a uniform suspension. The cells were

counted and spread onto 6-well plates in a 37°C 5% CO2

incubator overnight before transfection. After 24 h, the cells were

collected for analysis. Pancreatic enzyme digestion was performed

at 1,000 rpm for 5 min, then the supernatant was removed. Cells

were resuspended in 5-ml sterile PBS, a small sample was counted

using a hemocytometer at 1,000 rpm, and cells were collected again

after 5 min. In total, 3 ml of serum-free medium was added to

adjust cell density to 2×105/ml. Cells were added to

sterile 24-well plates with 500-μl complete medium per

well.; cells were transferred to 8-μm Transwell chambers

using forceps and gently inserted into the plate. The cell

suspension was mixed and 200 μl were added to the Transwell

chamber. Incubation lasted for 48 h, then cells were rinsed twice

with PBS. In total, 500 μl 4% PFA was added at room

temperature for 20 min. PFA was removed, washing three times with

PBS, and cells were stained with crystal violet for 20 min. Washing

three times with PBS was performed to remove unbound dye. The

Transwell chamber surface was gently wiped with a cotton swab to

remove residual dye, then rinsed once with PBS and allowed to

air-dry. Chambers were placed directly on a microscope slide and

images of purple-stained cells were captured.

The MAPK/ERK signaling pathway inhibitor PD98059 was

purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, while its

agonist U-46619 and the autophagy inducer RAPA were obtained from

MedChemExpress. Additionally, 3-methoxyamphetamine (3-MA) was

purchased from OriLeaf Biotechnology. Based on the concentration

screening results, 2 μmol/l rapamycin, 5 mmol/l 3-MA, 20

μM PD98059, and 2 μM U46619 were selected for the

experiment.

Immunohistochemical assay

The tissues were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde at

room temperature for 24 h, rinsed in running water and dehydrated

using gradient alcohols. Dehydrated tissues were embedded in wax

using an embedding machine, cooled at −20°C, trimmed and sectioned

at 4-μm thickness slices. Following incubation at 40°C for

1-3 min (on a water surface to flatten), the sections were

retrieved with glass slides, incubated at 60°C and stored. For

immunohistochemical staining, the sections were incubated at 62°C

for 1 h, the wax was removed and rehydrated prior to antigen

retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) with microwave treatment

(high-power for 1 min, medium-low for 9 min). Following cooling,

the sections were washed with PBS and treated with 3%

H2O in methanol to block endogenous peroxidase activity,

followed by PBS washing. Blocking was performed with diluted sheep

serum (1:10) (ZSGM-BIO) for 1 h at 37°C. Primary antibody

incubation with anti-rabbit YWHAH (1:1,000) was carried out

overnight at 4°C, followed by 30 min at room temperature, and

washing with PBST (1X PBS + 0.05% Tween-20). An HRP-labeled

secondary antibody (1:1,000) was added for 30 min at 37°C, followed

by PBST washing. DAB color development lasted for 1 min; it was

terminated with water and examined under a microscope.

Counterstaining with hematoxylin for 30 sec was followed by washing

and examination. The sections underwent dehydration, clearing and

mounting with neutral gum.

Online database

The RNA-sequencing expression (level 3) profiles and

the corresponding clinical information for CRC were downloaded from

The Cancer Genome Atlas (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/analysis_page?app=Downloads).

Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to analysis using SPSS

version 21.0 (IBM Corp.) or GraphPad Prism version 10.1.2

(Dotmatics). The nominal and absolute values were assessed

employing either paired t-tests or one-way ANOVA. All analyses were

conducted utilizing R version 4.0.3 (https://www.r-project.org/), along with the

appropriate R packages. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Data are expressed as the

mean ± standard deviation (SD). Error bars in all figures indicate

SD from three biological replicates.

Results

Association between YWHAH and clinical

pathological characteristics of CRC

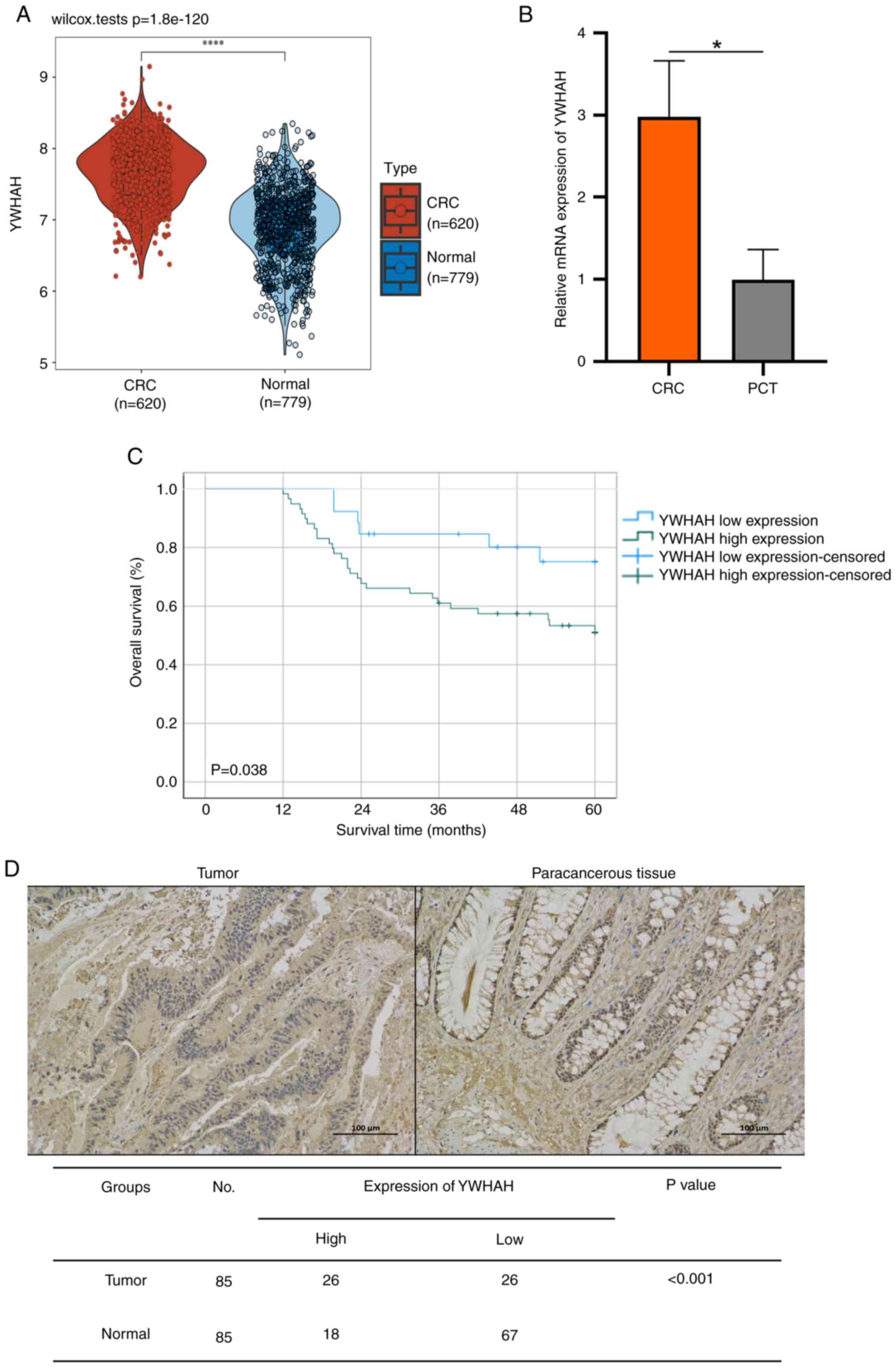

In a previous study using acRIP-seq, the involvement

of YWHAH in CRC was established. The analysis with the R software

markedly raised YWHAH levels in tumors relative to normal tissues

(Fig. 1A). RT-qPCR confirmed

this result in CRC tumor and paracancerous tissue (PCT) (Fig. 1B). Immunohistochemical analysis

was performed on 85 CRC tissue pairs (tumor and PCT), revealing

notably high YWHAH levels in tumors (P<0.001; Fig. 1D) and a strong association with

poor overall survival (P=0.038; Fig.

1C). YWHAH expression was significantly linked to CRC tissue

differentiation (P=0.024), tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage

(P=0.011), N stage (P=0.028) and vascular invasion (P=0.04;

Table I).

| Table IThe relationship between YWHAH

protein expression and clinicopathological parameters in patients

with CRC. |

Table I

The relationship between YWHAH

protein expression and clinicopathological parameters in patients

with CRC.

| Clinicopathological

characteristics | Total (n=85) | Expression level of

YWHAH

| P-value |

|---|

| High | Low |

|---|

| CRC | 85 | 59 (69.4%) | 26 (30.6%) | |

| Age, years | | | | 0.806 |

| ≥60 | 48 | 36 | 12 | |

| <60 | 37 | 23 | 14 | |

| Sex | | | | 0.174 |

| Female | 42 | 29 | 13 | |

| Male | 43 | 30 | 13 | |

| Tumor size | | | | 0.335 |

| ≥5 cm | 36 | 22 | 14 | |

| <5 cm | 49 | 37 | 12 | |

| G stage | | | | 0.024 |

| G1 | 33 | 22 | 11 | |

| G2 | 34 | 24 | 10 | |

| G3 | 18 | 13 | 5 | |

| T stage | | | | 0.673 |

| T1/T2 | 17 | 11 | 6 | |

| T3/T4 | 68 | 48 | 20 | |

| TNM stage | | | | 0.011 |

| I/II | 49 | 35 | 14 | |

| III/IV | 36 | 24 | 12 | |

| N stage | | | | 0.028 |

| N0 | 49 | 28 | 21 | |

|

N1+2 | 36 | 31 | 5 | |

| Perineural

invasion | | | | 0.3725 |

| No | 56 | 40 | 16 | |

| Yes | 29 | 19 | 10 | |

| Vascular

invasion | | | | 0.04 |

| No | 53 | 34 | 19 | |

| Yes | 32 | 25 | 7 | |

These studies are in consistency with previous

research, suggesting that YWHAH is a major factor in CRC

tumorigenesis and could function as a biomarker and a target for

therapy.

Cell and animal experiments for the

verification of YWHAH on CRC proliferation

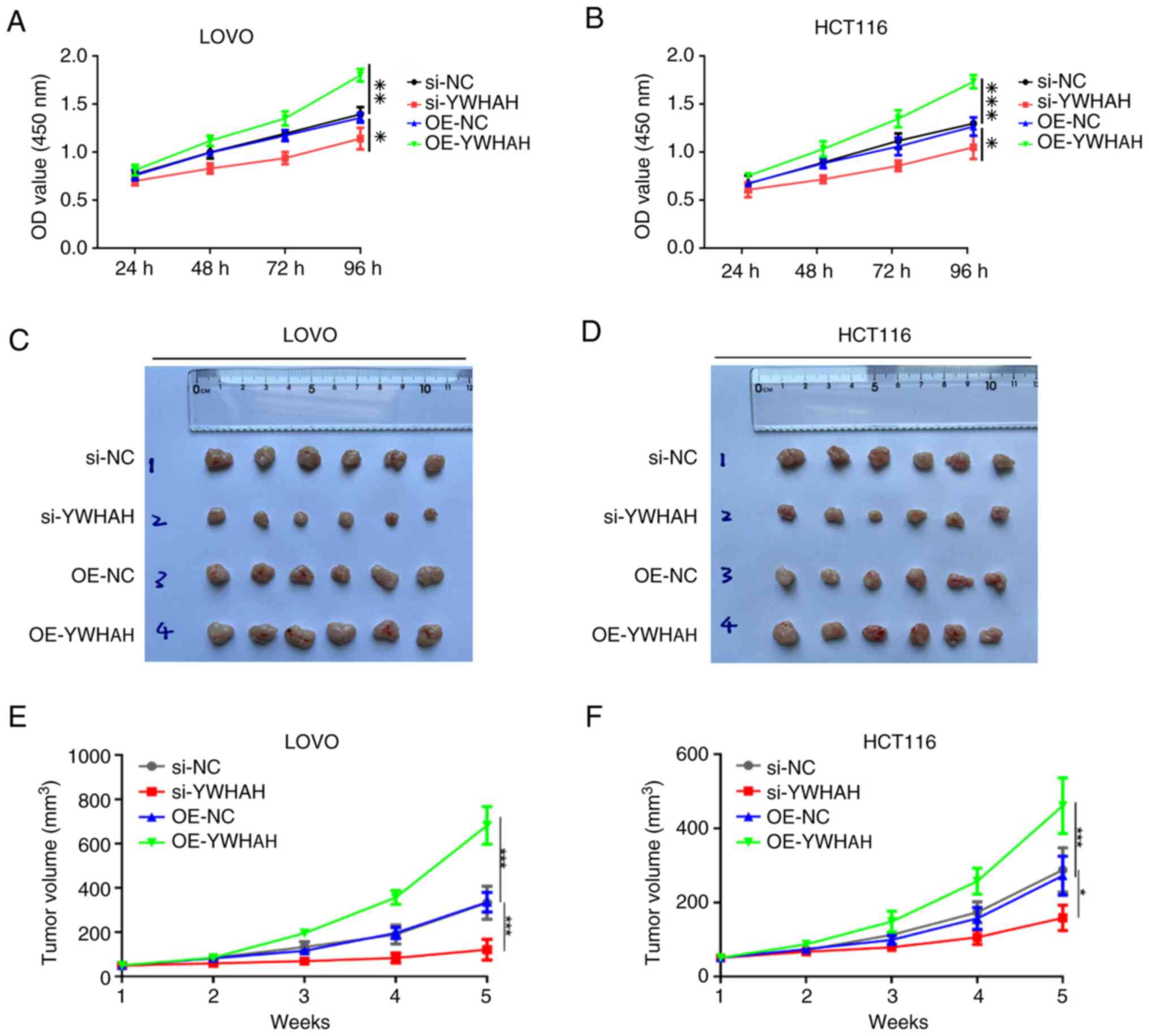

In our previous study, colony formation assays were

conducted, and the results showed that YWHAH overexpression

markedly increased colony numbers in both cell lines (12). In the present study, the CCK-8

assay was performed to assess the influence of varying YWHAH

expression levels on the proliferative capacity of CRC cells. As

illustrated in Fig. 2A and B,

YWHAH overexpression significantly enhanced the proliferative

ability of LOVO cells, whereas YWHAH suppression markedly

diminished their proliferative capacity (P<0.05). Similar

results were observed in HCT116 cells.

To assess the oncogenic potential of YWHAH in

vivo, subcutaneous xenograft models in nude mice were performed

utilizing cells transfected with si-NC, si-YWHAH, overexpression

(OE)-NC and OE-YWHAH constructs. Tumor growth was monitored on a

weekly basis and growth curves were subsequently generated.

Following a period of 5 weeks, the mice were euthanized, and the

tumors were excised to measure their volumes. The findings

indicated that tumors in the YWHAH overexpression group exhibited a

significantly larger volume compared with those in the OE-NC group.

Conversely, knockdown of YWHAH expression resulted in a

significantly reduced tumor volume compared with the si-NC group

(Fig. 2C-F). These in

vitro and in vivo results collectively suggest that

YWHAH facilitates the proliferation of CRC cells.

Impact of YWHAH on the

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of CRC cells

The authors' previous study found that knockdown of

YWHAH expression levels significantly lowered the numbers of

migratory and invasive cells in both cell lines (P<0.01). In

contrast to these observations, YWHAH overexpression exhibited the

opposite effect, increasing both these processes. These results

suggested that YWHAH positively regulated the migratory and

invasive capabilities of CRC cells (12).

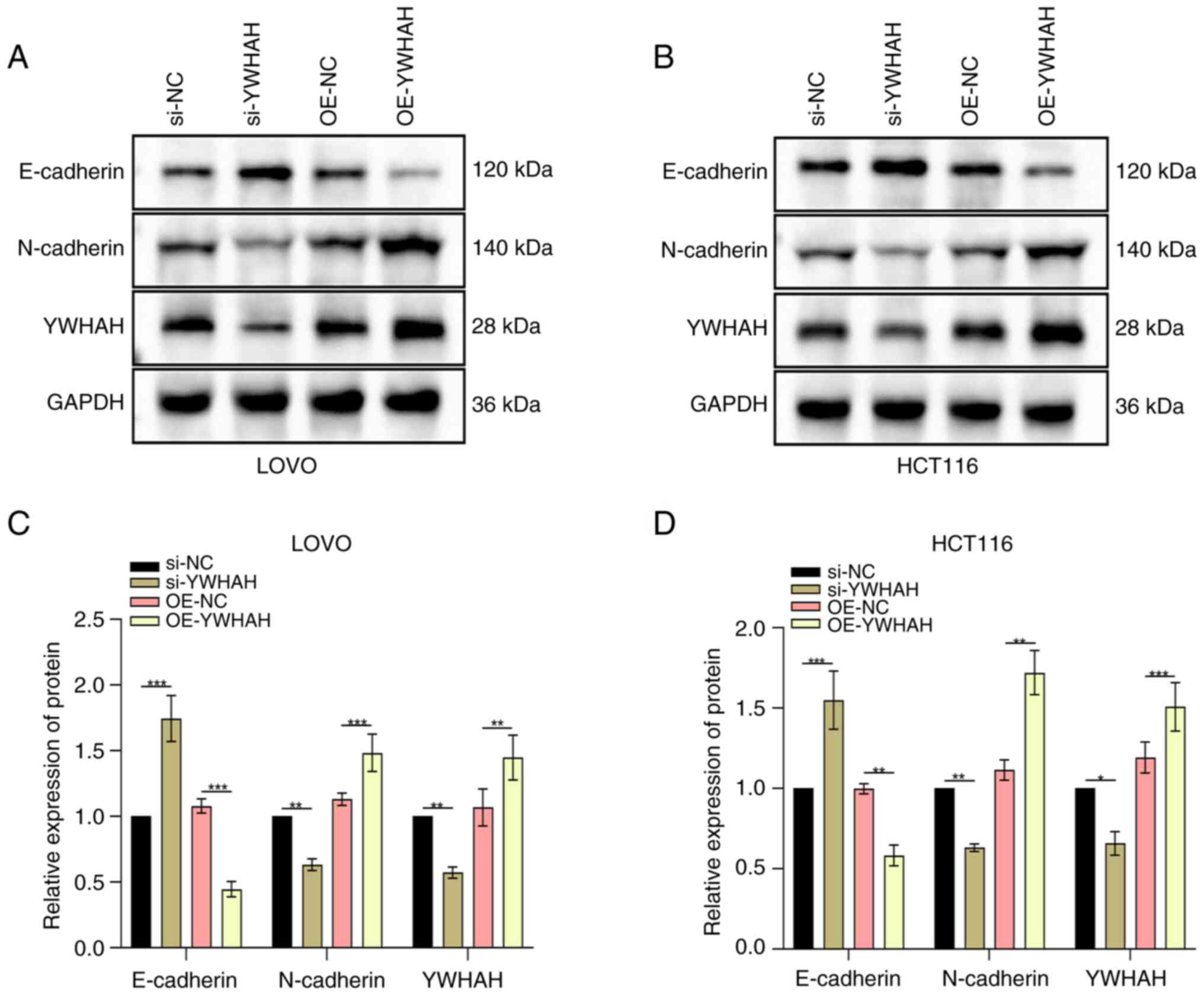

To further assess the influence of YWHAH on the EMT

of CRC cells, western blotting was utilized to assess the changes

in EMT markers. These indicated a decrease in E-cadherin and an

increase in N-cadherin levels in cells overexpressing YWHAH.

Conversely, in knockdown cells, E-cadherin was elevated, while

N-cadherin levels declined (Fig.

3A-D).

Association between YWHAH and apoptosis

in CRC cells

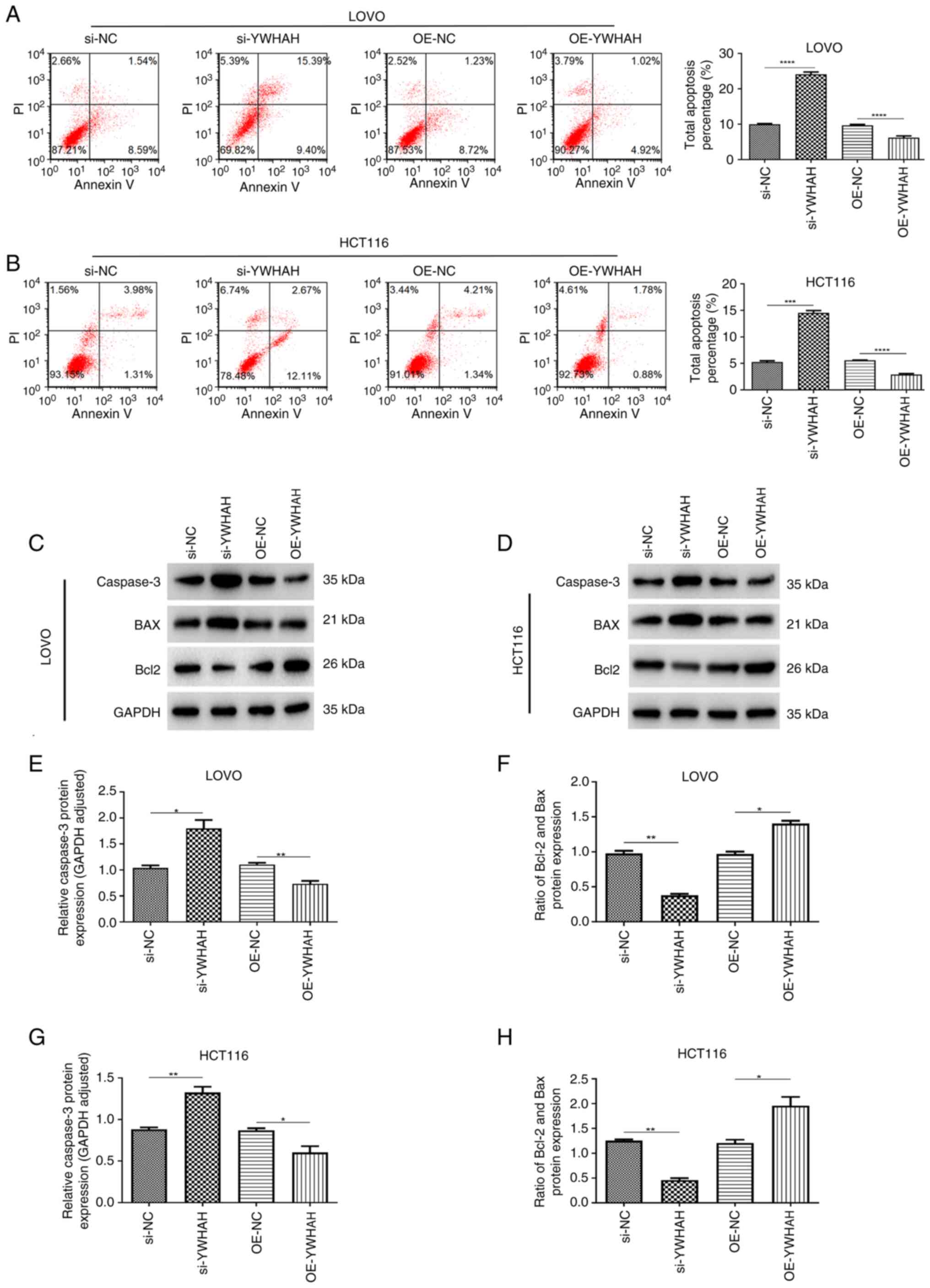

The induction of apoptosis is closely associated

with tumor suppression. Flow cytometry was used to assess the

function of YWHAH in modulating the apoptotic response in CRC

cells. As illustrated in Fig. 4,

knockdown of YWHAH expression via siRNA (si-YWHAH) significantly

increased the apoptotic rate in both cell lines, while OE-YWHAH

resulted in reduced apoptotic rates in these cell lines (Fig. 4A and B). Western blot analysis

further revealed that knockdown of YWHAH expression led to an

upregulation of caspase 3 and a decrease of Bcl-2/BAX protein

levels in LOVO and HCT116 cell lines. Conversely, YWHAH

overexpression significantly inhibited the expression of caspase 3

whilst it enhanced the Bcl-2/BAX protein in both cell lines

(Fig. 4C-H). Collectively, these

findings suggested that YWHAH overexpression suppresses apoptosis

in CRC cells.

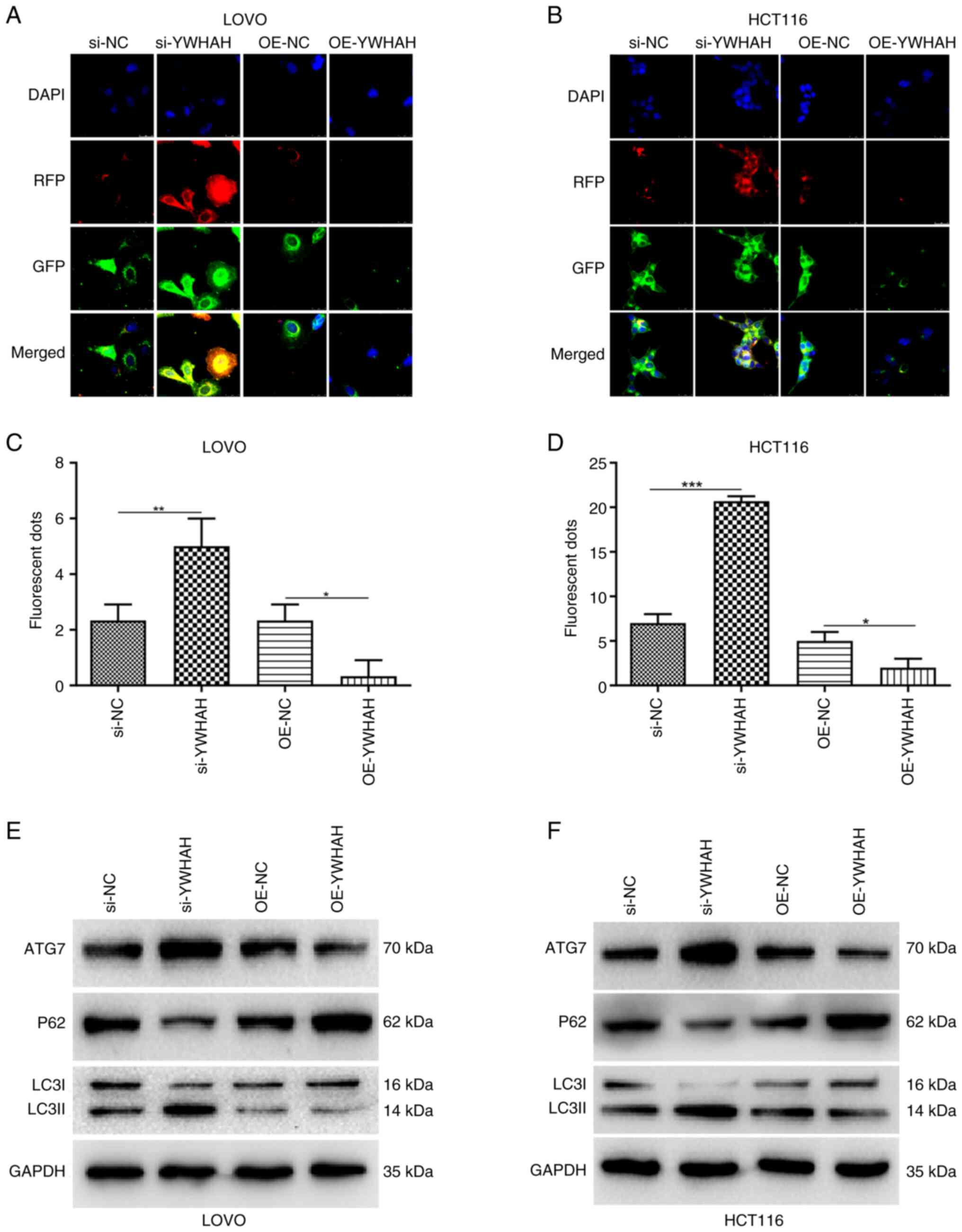

Association between YWHAH and autophagy

in CRC cells

A dual-labeled LC3B construct enables the distinct

visualization of autophagosomes and autolysosomes, capitalizing on

the divergent pH stabilities of its two fluorescent components.

Specifically, within the acidic environment of lysosomes, the

fluorescent signals from the red (mRFP) and green (GFP) proteins

undergo differential quenching. By utilizing the mRFP-GFP-LC3 dual

fluorescence system, a more profound understanding of the role of

YWHAH in autophagy was obtained. Fluorescence microscopy indicated

significantly increased numbers of fluorescent puncta in

YWHAH-knockdown CRC cells compared with those of the controls.

These observations indicated that the disruption of YWHAH

expression could enhance autophagy. Furthermore, the red

fluorescent puncta were substantially more abundant than the green

ones and their co-localization resulted in a predominantly red

region, corroborating the efficient progression of autophagy.

Conversely, the opposite effects were observed in YWHAH-OE CRC

cells (Fig. 5A-D). These

findings were subsequently validated by western blot analysis

(Fig. 5E-F). Specifically,

knockdown of YWHAH expression via siRNA led to an upregulation of

autophagy related 7 (ATG7) and LC3II/I protein expression in both

LOVO and HCT116 cells, while it resulted in a downregulation of P62

protein expression. In contrast to these observations, YWHAH

overexpression significantly suppressed the levels of ATG7 and the

LC3II/I ratio in both cell lines, while increasing P62 expression

specifically in LOVO cells. In addition, YWHAH overexpression

exhibited a tendency to increase P62 expression in the HCT116 cell

line.

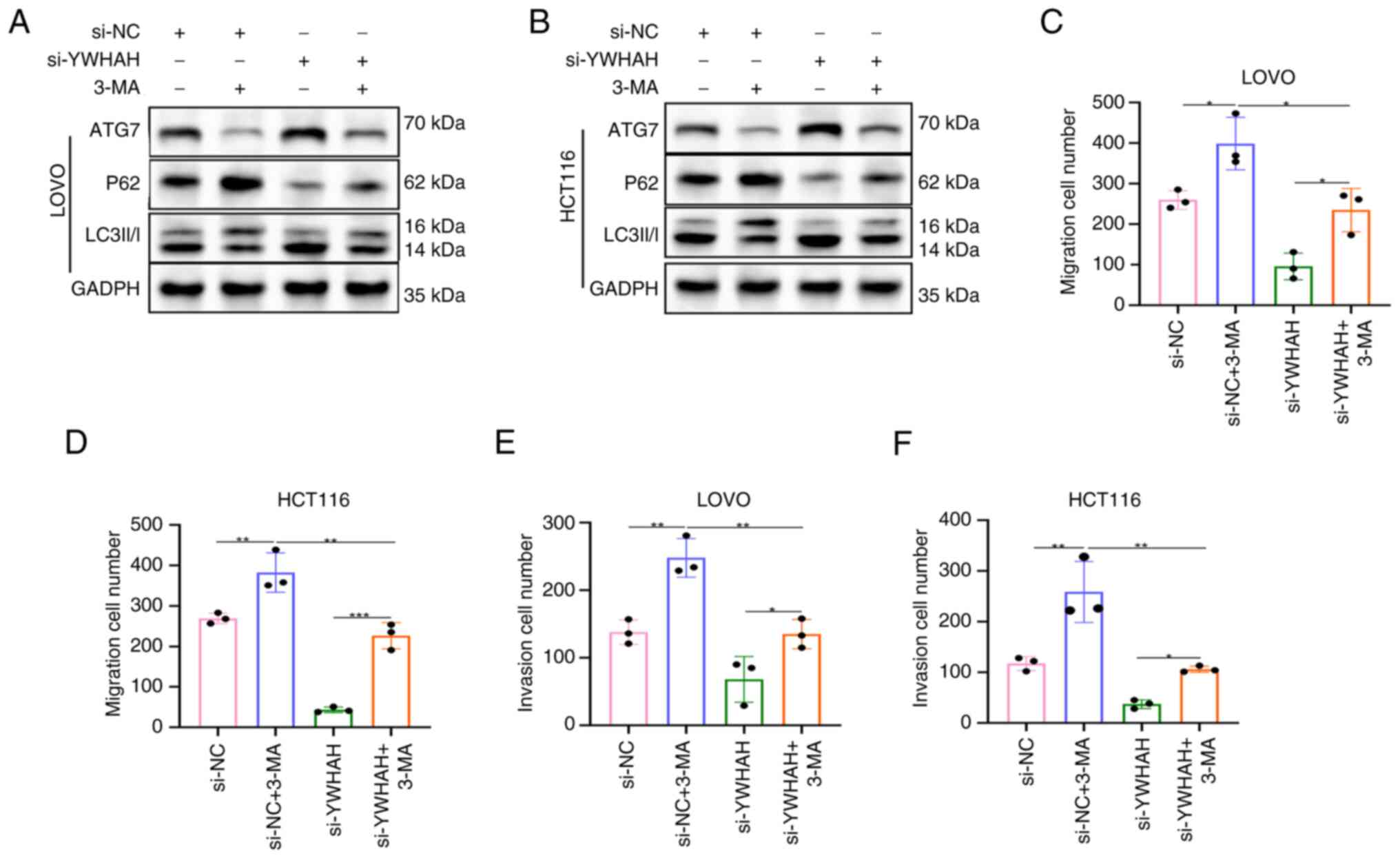

Inhibition of autophagy reverses the

suppressive effects of si-YWHAH on CRC cell migration and

invasion

It has been found that YWHAH inhibits autophagy in

CRC cells. To explore if this affects cell migration and invasion,

experiments altering autophagic flux were conducted. Initially,

autophagy was inhibited and the data indicated that si-YWHAH

increased ATG7 and LC3II/I levels, while it decreased those of P62,

confirming that it induced autophagy. In contrast to these

observations, the addition of 3-methoxyamphetamine (3-MA) to both

si-NC and si-YWHAH groups reduced ATG7 and LC3II/I levels, while it

increased P62 levels (Fig. 6A and

B), indicating that 3-MA suppressed autophagy in these

cells.

The Transwell assay indicated that the si-NC + 3-MA

group exhibited a significantly higher number of migratory and

invasive cells than the si-NC group, suggesting increased migration

and invasion following inhibition of autophagy. In the si-YWHAH +

3-MA group, cell migratory and invasive activities were lower than

those noted in the si-NC + 3-MA group, yet higher than those of the

si-YWHAH group, indicating that 3-MA reversed the inhibitory

effects of si-YWHAH on CRC cell migration and invasion (Figs 6C-F and S2). This confirmed that inhibition of

autophagy could counteract the suppressive impact of knockdown of

YWHAH expression on these processes.

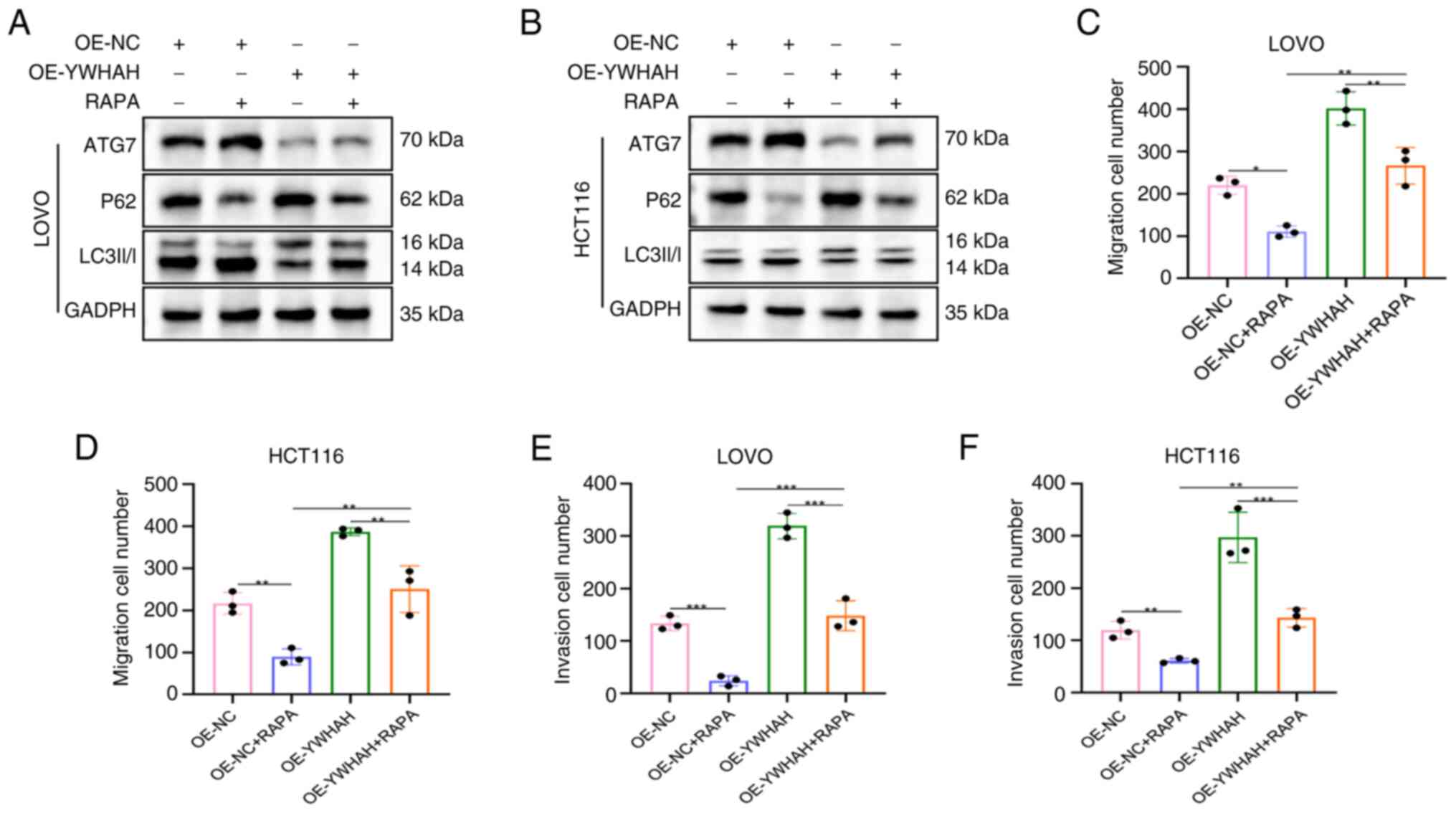

Activation of autophagy reverses the

promoting effect of OE-YWHAH on CRC cell migration and

invasion

An in-depth analysis of migration and invasion in

CRC cells was performed with stable knockdown and overexpression

models of YWHAH by introducing the autophagy inducer Rapamycin

(RAPA). In the OE-YWHAH group, the levels of ATG7 and LC3II/I were

markedly reduced compared with those of OE-NC cells, while P62

levels were notably elevated, suggesting that OE-YWHAH inhibits

autophagy in CRC cells, corroborating previous research findings.

In contrast to these observations, OE-NC + RAPA cells exhibited a

marked rise in ATG7 and LC3II/I levels together with reduced P62

levels compared with those noted in OE-NC cells. Similarly,

OE-YWHAH + RAPA cells demonstrated markedly elevated ATG7 and

LC3II/I levels and decreased P62 levels compared with OE-YWHAH

cells, indicating that RAPA effectively activated autophagy in CRC

cells (Fig. 7A and B).

Furthermore, the results from the Transwell migration and invasion

assays revealed that the number of migratory and invasive cells in

the si-NC + RAPA cells was significantly decreased compared with

that of OE-NC cells (Figs. 7C-F

and S3), suggesting that

autophagy activation led to a relative reduction in migratory and

invasive activities.

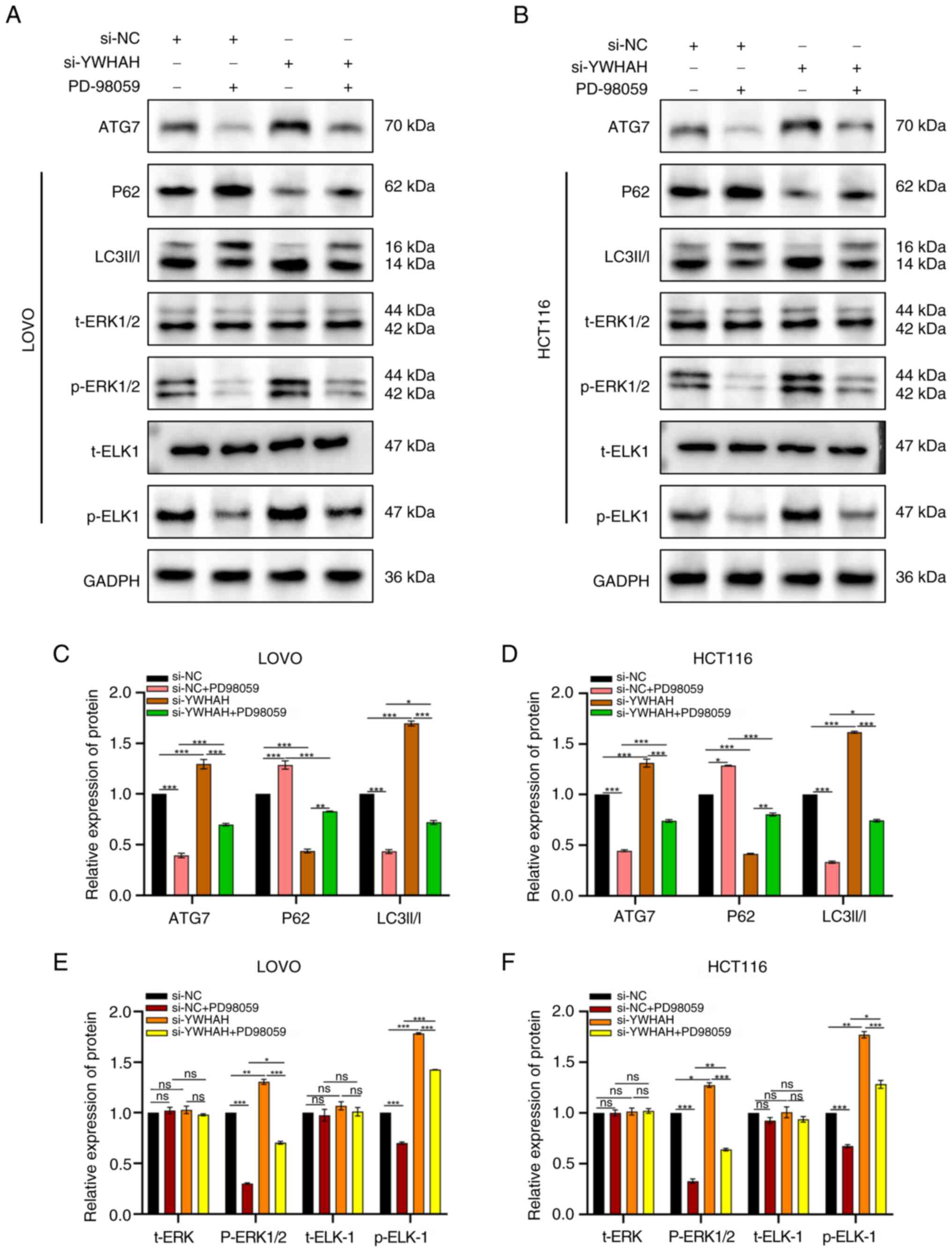

YWHAH induces autophagy via the MAPK/ERK

signaling pathway

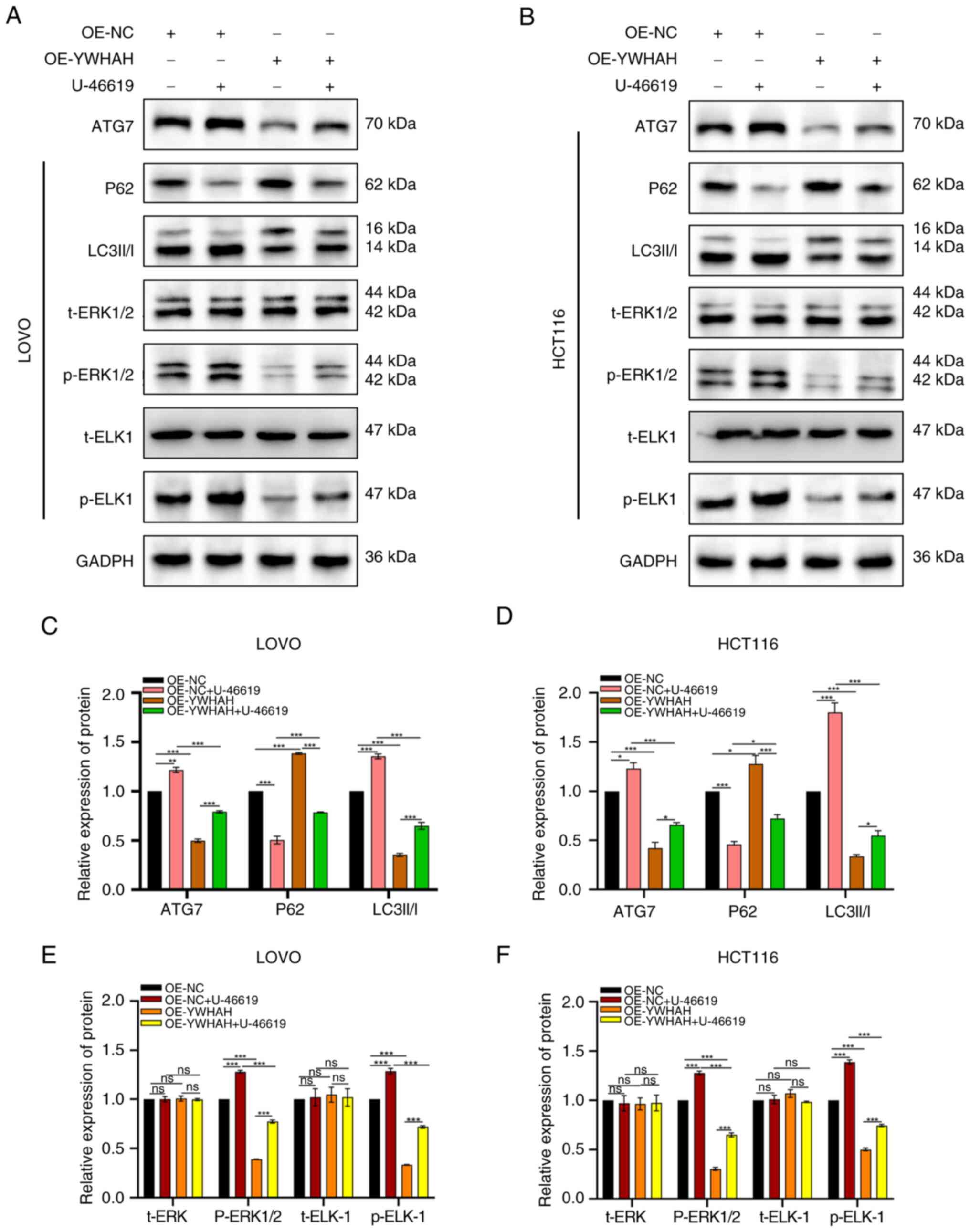

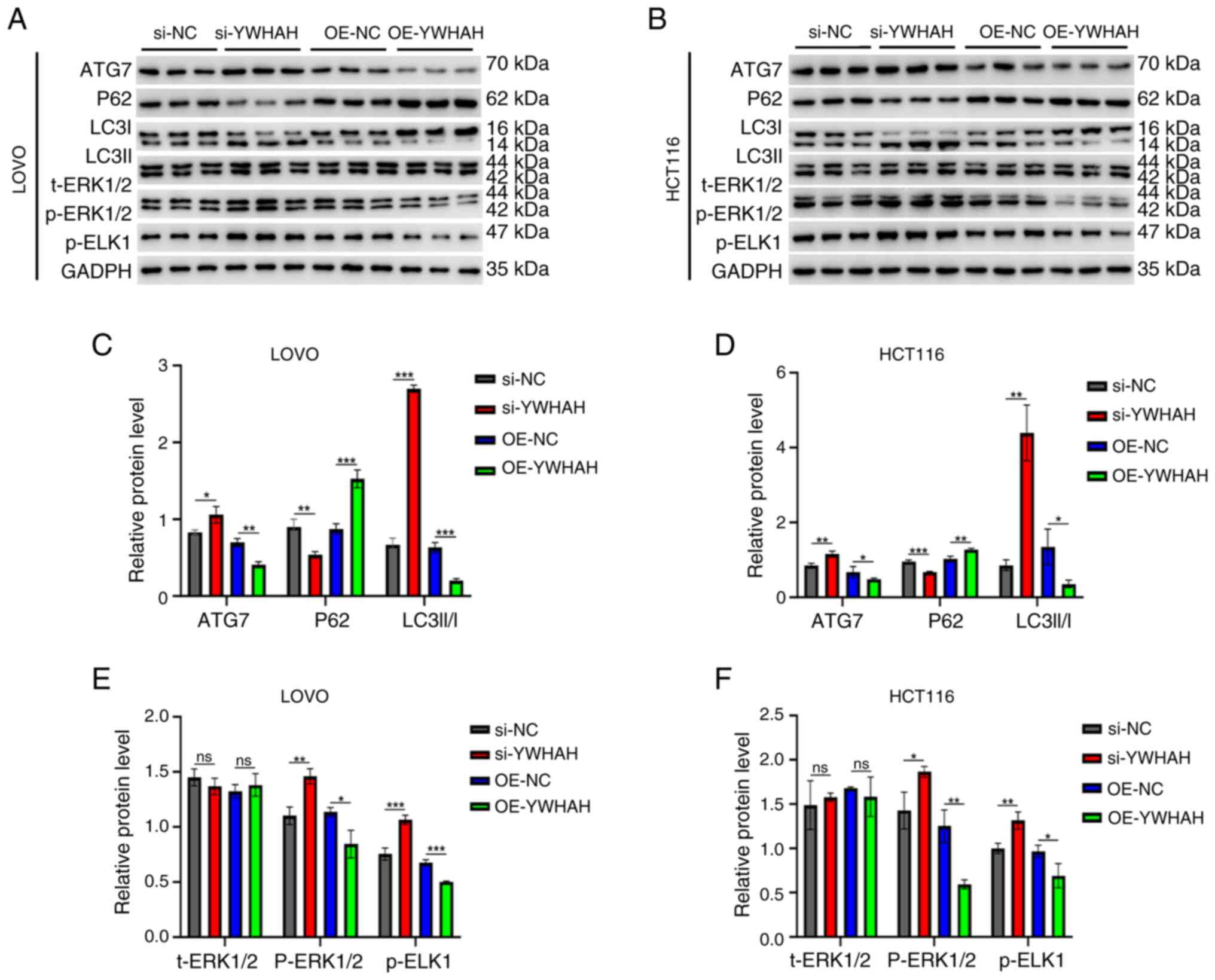

In subsequent studies, the MAPK/ERK signaling

pathway inhibitor PD98059 and the agonist U-46619 were used to

evaluate the levels of the related pathway proteins ERK1/2,

phosphorylated (p)-ERK1/2, and p-ETS Like-1 protein (ELK)-1 by

western blotting. The aim of these experiments was to assess

whether YWHAH exhibited regulatory effects on the ERK signaling

pathway.

Previous studies have demonstrated that YWHAH

overexpression inhibits autophagy, whereas its knockdown promotes

autophagy. The present study explored the ERK pathway-related

protein expression following alteration of the YWHAH levels. The

results revealed that si-YWHAH increased p-ERK1/2 and p-ELK-1

expression levels, activating the MAPK/ERK pathway, while OE-YWHAH

decreased their expression levels, suppressing the pathway. In

addition, si-YWHAH reversed the inhibitory effect of PD98059 on the

pathway, as p-ERK1/2 and p-ELK-1 levels were higher in si-YWHAH +

PD98059 cells compared with those of the si-NC + PD98059 cells

(Fig. 8). Subsequent

investigations indicated that p-ERK1/2 and p-ELK-1 levels were

significantly elevated in OE-NC + U46619 cells compared with those

of the OE-NC cells. They were also higher in OE-YWHAH + U46619

cells compared with those of the OE-YWHAH cells; however, they were

lower than those noted in the OE-NC + U46619 cells (Fig. 9). This suggested that YWHAH

overexpression could counteract the activation of the signaling

pathway by U46619. The protein expression levels were statistically

significant, with the exception of t-ERK. Overall, these results

indicated that YWHAH negatively regulated the ERK axis in CRC

cells.

To further investigate the relationship between the

regulation of autophagy by YWHAH in CRC and the involvement of the

MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, the expression levels of

autophagy-related proteins were investigated following inhibition

and activation of the ERK signaling pathway.

Western blotting indicated that in si-YWHAH cells,

ATG7 and LC3II/I levels were significantly elevated, while P62

levels were lower compared with those noted in si-NC cells

(Fig. 8). The introduction of

the inhibitor PD98059 to the si-YWHAH group decreased the levels of

ATG7 and LC3II/I, while it increased those of P62, indicating

reduced autophagy and reversal of the activation effect of si-YWHAH

on autophagy in CRC cells (Fig.

8). Conversely, in the OE-YWHAH group, ATG7 and LC3II/I levels

were lower, and P62 expression was higher. The addition of the

activator U-46619 increased ATG7 and LC3II/I levels and reduced P62

expression (Fig. 9), suggesting

enhanced autophagy and reversal of the inhibitory effect of

OE-YWHAH on autophagy in these cells. In summary, these results

indicated that in CRC cells, YWHAH regulated autophagy in a manner

dependent on the MAPK/ERK axis.

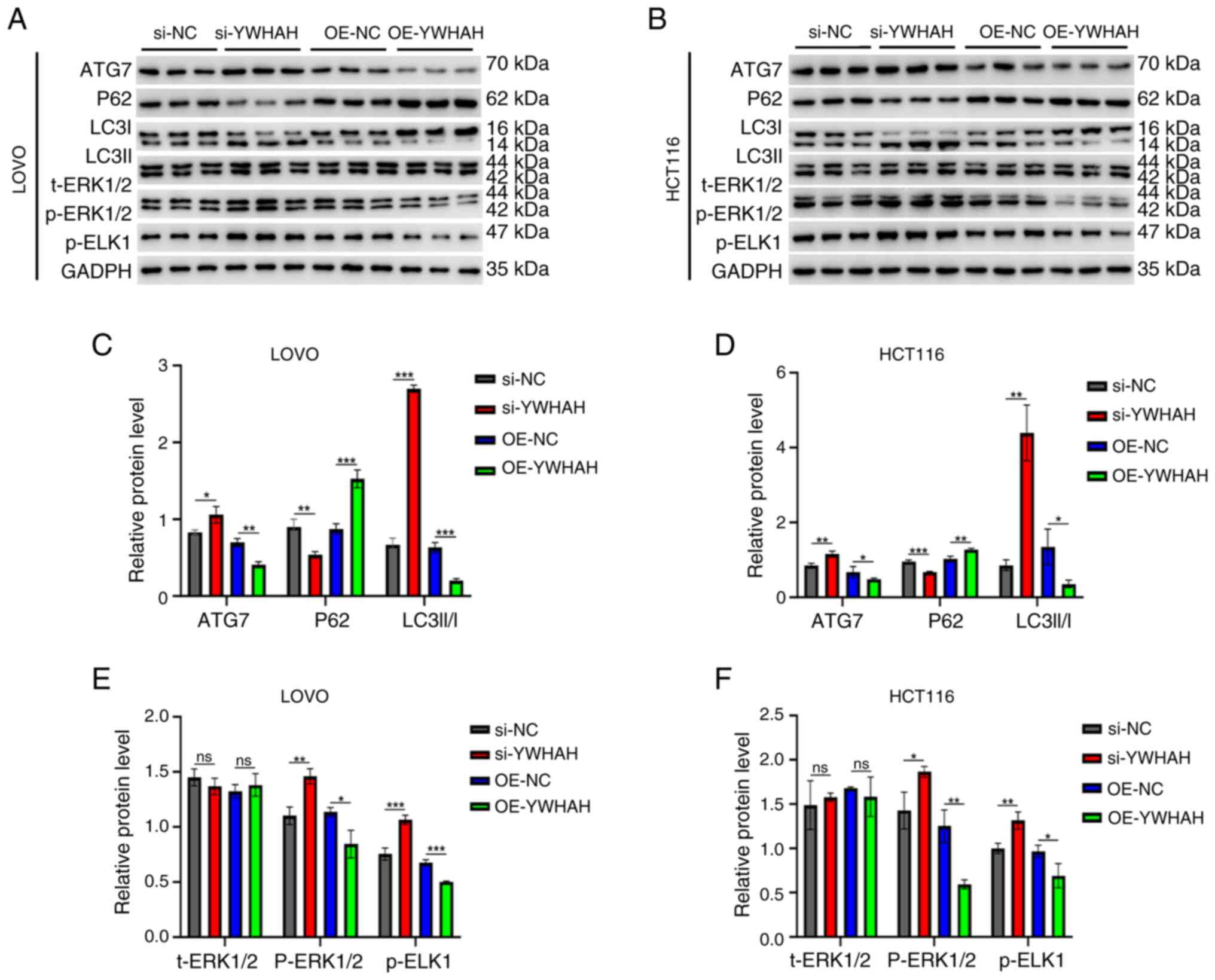

YWHAH regulates autophagy in CRC tissues

via the MAPK/ERK axis in vivo

To evaluate if YWHAH inhibits autophagy in CRC via

the MAPK/ERK pathway, the expression levels of autophagic and

signaling proteins were investigated in nude mouse tumors. In the

si-YWHAH group, the expression levels of the autophagic markers

ATG7 and LC3II/I were increased, while the levels of P62 were

reduced, indicating enhanced autophagy. Conversely, in OE-YWHAH

cells, the expression levels of ATG7 and LC3II/I were lowered,

while those of P62 were increased, suggesting reduced autophagy. In

addition, p-ERK1/2 and p-ELK-1 levels were increased in the

si-YWHAH group and decreased in the OE-YWHAH group (Fig. 10A-F). These results confirmed

that YWHAH inhibited autophagy in CRC via the MAPK/ERK pathway.

| Figure 10YWHAH inhibits autophagy through

MAPK/ERK signaling pathway in vivo. (A and B) Western

blotting was used to evaluate the protein expression of ATG7, P62,

LC3II/I, t-ERK1/2, p-ERK1/2 and p-ELK-1 when the nude mice were

injected with CRC cells. (C-F) Semi-quantitative analysis of

autophagy related proteins and MAPK/ERK signaling related proteins

when the nude mice were injected with CRC cells.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. Data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation (n=3 independent experiments). YWHAH, tyrosine

3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein Eta;

t-, total; p-, phosphorylated; CRC, colorectal cancer; ATG7,

autophagy related 7; OE, overexpression; si-, small interfering;

NC, negative control; ns, not significant (P>0.05). |

Discussion

The 14-3-3 protein, YWHAH, is integral to processes,

such as cell signaling, apoptosis, cell cycle modulation,

transcription and the malignant transformation of cells (15-18). In a previous investigation,

ac4C-acetylation sequencing was employed to identify YWHAH; the

data substantiated that acetylation significantly influenced the

stability of YWHAH (12). In the

present study, a comprehensive examination of the role of YWHAH in

CRC was performed; moreover, its association with the clinical

pathological characteristics was investigated. By using various

cellular and animal experiments, the effects of YWHAH were examined

on cellular proliferation, migration, invasion and autophagy of CRC

cells. These findings enhance the understanding of the involvement

of YWHAH in CRC progression and offer novel insights for future

therapeutic approaches.

CRC development is a multi-stage process marked by

gene expression changes and phenotypic shifts that activate

signaling pathways, enhancing malignancy via inhibition of

apoptosis, increased angiogenesis and EMT (19-22). These factors collectively drive

CRC initiation and progression. Tumor cell migration and invasion

are key to malignancy, with autophagy playing a complex role by

affecting cell survival, proliferation, migration and invasion via

intracellular homeostasis (23-26). BMP9, for instance, promotes

autophagy and inhibits breast cancer cell migration via the

c-Myc/SNHG3/mTOR pathway, suggesting similar mechanisms in CRC

(27). CD133 influences CRC cell

migration and invasion by modulating autophagy, while interactions

between inflammatory factors and autophagy in the TME may also aid

CRC metastasis (27). Elevated

levels of YWHAH have been observed in CRC tissues; this protein was

linked to tissue differentiation, lymph node metastasis, vascular

invasion and TNM staging. In cells, YWHAH overexpression boosted

CRC cell proliferation, migration and invasion, while knockdown of

its expression inhibited these activities. In vivo, YWHAH

overexpression increased tumor size and weight, whereas knockdown

of its expression reduced them. YWHAH also promoted CRC cell

invasion and metastasis by regulating EMT. Autophagy involves

pathways such as the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK family members, such as

ERK, which exhibit a complex interaction with autophagy (27-31).

In the present study, it was revealed that YWHAH

influences the MAPK/ERK pathway activation, regulating autophagy in

CRC cells. Overexpression of YWHAH enhances CRC cell migration and

invasion by negatively affecting autophagy and mediating the

MAPK/ERK pathway. However, the small sample size of the tissues

used may limit the findings and other mechanisms may also play a

role in the oncogenic effects of YWHAH. Current models may not

fully capture human CRC complexity. Future research should examine

the interactions of YWHAH with other pathways, validate findings in

larger studies and develop models that mimic human CRC more

efficiently. The exploration of the targeted therapies of YWHAH in

combination with the existing treatments can improve the outcomes

of CRC.

In summary, the current data indicated that YWHAH

plays a pivotal role in the progression of CRC by modulating

apoptosis and autophagy via the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway.

Targeting YWHAH or its downstream pathways can provide novel

therapeutic strategies for the treatment of CRC.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QL was responsible for conceptualizing, developing

methods, conducting formal analysis, managing resources, validating

findings, curating data, drafting the original manuscript, and

reviewing and editing the final version. YW contributed to

conceptualization, resource allocation, and reviewing and editing

of the writing. ZY contributed to the methodology, formal analysis,

resources, and writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. PZ

developed methodology. JW conducted formal analysis and data

validation. CZ performed formal analysis and data curation. ZS

developed methodology and validated data. CX contributed to

conceptualization, investigation, data validation, and writing,

reviewing and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. QLi and PZ confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures conducted in studies involving human

participants adhered to the ethical standards set by the Ethics

Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical

University (approval no. 2023100505), as well as the principles

outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent

amendments concerning research involving human subjects. Written

informed consent was provided by all participants or their legal

representatives. All animal experiments received approval (approval

no. 2023110512) from the Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Medical

University (Xuzhou, China) for the use of animals and were

performed in compliance with the National Institutes of Health

Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All

institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of

laboratory animals were strictly followed.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

YWHAH

|

tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan

5-monooxygenase activation protein Eta

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

3-MA

|

3-methoxyamphetamine

|

|

RAPA

|

rapamycin

|

|

acRIP-seq

|

acetylated RNA immunoprecipitation and

sequencing

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Key

Laboratory of Tumor Biotherapy (grant no. XZSYSKF2023033).

References

|

1

|

Keum N and Giovannucci E: Global burden of

colorectal cancer: Emerging trends, risk factors and prevention

strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:713–732. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Baidoun F, Elshiwy K, Elkeraie Y, Merjaneh

Z, Khoudari G, Sarmini MT, Gad M, Al-Husseini M and Saad A:

Colorectal cancer epidemiology: Recent trends and impact on

outcomes. Curr Drug Targets. 22:998–1009. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gonzalez NS, Ros Montana FJ, Illescas DG,

Argota IB, Ballabrera FS and Elez Fernandez ME: New insights into

adjuvant therapy for localized colon cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin

North Am. 36:507–520. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Long J, He Q, Yin Y, Lei X, Li Z and Zhu

W: The effect of miRNA and autophagy on colorectal cancer. Cell

Prolif. 53:e129002020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Orlandi G, Roncucci L, Carnevale G and

Sena P: Different roles of apoptosis and autophagy in the

development of human colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci.

24:102012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang D, He J, Dong J, Wu S, Liu S, Zhu H

and Xu T: UM-6 induces autophagy and apoptosis via the Hippo-YAP

signaling pathway in cervical cancer. Cancer Lett. 519:2–19. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jiao YN, Wu LN, Xue D, Liu XJ, Tian ZH,

Jiang ST, Han SY and Li PP: Marsdenia tenacissima extract induces

apoptosis and suppresses autophagy through ERK activation in lung

cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 18:1492018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pohl C and Dikic I: Cellular quality

control by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Science.

366:818–822. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li X, He S and Ma B: Autophagy and

autophagy-related proteins in cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:122020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Green DR: The coming decade of cell death

research: Five riddles. Cell. 177:1094–1107. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li Q, Yuan Z, Wang Y, Zhai P, Wang J,

Zhang C, Shao Z and Xing C: Unveiling YWHAH: A potential

therapeutic target for overcoming CD8(+) T cell exhaustion in

colorectal cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 135:1123172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kacirova M, Novacek J, Man P, Obsilova V

and Obsil T: Structural basis for the 14-3-3 protein-dependent

inhibition of phosducin function. Biophys J. 112:1339–1349. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Obsil T and Obsilova V: Structural basis

of 14-3-3 protein functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 22:663–672. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Darling DL, Yingling J and Wynshaw-Boris

A: Role of 14-3-3 proteins in eukaryotic signaling and development.

Curr Top Dev Biol. 68:281–315. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Nguyen NM, Meyer D, Meyer L, Chand S,

Jagadesan S, Miravite M, Guda C, Yelamanchili SV and Pendyala G:

Identification of YWHAH as a novel brain-derived extracellular

vesicle marker post long-term midazolam exposure during early

development. Cells. 12:9662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Huang Y, Yang M and Huang W: 14-3-3 σ: A

potential biomolecule for cancer therapy. Clin Chim Acta.

511:50–58. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Munier CC, Ottmann C and Perry MWD: 14-3-3

modulation of the inflammatory response. Pharmacol Res.

163:1052362021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Malki A, ElRuz RA, Gupta I, Allouch A,

Vranic S and Al Moustafa AE: Molecular Mechanisms of colon cancer

progression and metastasis: Recent insights and advancements. Int J

Mol Sci. 22:1302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Nicolini A and Ferrari P: Involvement of

tumor immune microenvironment metabolic reprogramming in colorectal

cancer progression, immune escape, and response to immunotherapy.

Front Immunol. 15:13537872024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shin AE, Giancotti FG and Rustgi AK:

Metastatic colorectal cancer: Mechanisms and emerging therapeutics.

Trends Pharmacol Sci. 44:222–236. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lu J, Kornmann M and Traub B: Role of

epithelial to mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:148152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang Y, Yang Y, Qi X, Cui P, Kang Y, Liu

H, Wei Z and Wang H: SLC14A1 and TGF-β signaling: A feedback loop

driving EMT and colorectal cancer metachronous liver metastasis. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:2082024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Li W, Zhou C, Yu L, Hou Z, Liu H, Kong L,

Xu Y, He J, Lan J, Ou Q, et al: Tumor-derived lactate promotes

resistance to bevacizumab treatment by facilitating autophagy

enhancer protein RUBCNL expression through histone H3 lysine 18

lactylation (H3K18la) in colorectal cancer. Autophagy. 20:114–130.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

25

|

Xie Q, Liu Y and Li X: The interaction

mechanism between autophagy and apoptosis in colon cancer. Transl

Oncol. 13:1008712020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Foerster EG, Mukherjee T, Cabral-Fernandes

L, Rocha JDB, Girardin SE and Philpott DJ: How autophagy controls

the intestinal epithelial barrier. Autophagy. 18:86–103. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Adebayo AS, Agbaje K, Adesina SK and

Olajubutu O: Colorectal cancer: Disease process, current treatment

options, and future perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 15:26202023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ma L, Zhang R, Li D, Qiao T and Guo X:

Fluoride regulates chondrocyte proliferation and autophagy via

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Chem Biol Interact.

349:1096592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yang K, Luan L, Li X, Sun X and Yin J: ERK

inhibition in glioblastoma is associated with autophagy activation

and tumorigenesis suppression. J Neurooncol. 156:123–137. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Guo YJ, Pan WW, Liu SB, Shen ZF, Xu Y and

Hu LL: ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp Ther Med.

19:1997–2007. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lee S, Rauch J and Kolch W: Targeting MAPK

signaling in cancer: Mechanisms of drug resistance and sensitivity.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:11022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|