Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common joint

diseases worldwide and its incidence in the world population

>60-years old is ~20%. The typical features of OA including

cartilage degeneration, osteophyte formation, subchondral bone

sclerosis and synovial inflammation (1,2).

Although a number of studies have shown that the sex, age and

obesity are the main risks factors of OA, the pathophysiology of OA

has not been fully demonstrated (3,4).

Increasing number of studies reveal that inflammation and

inflammatory cytokines seem to play a critical role in the

initiation and progression of OA. Among these inflammatory

cytokines, IL-1β is considered as the most important (5). IL-1β contributes to the cartilage

degradation via increasing the expression of matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs), NO and prostaglandin E2 (6,7).

Moreover, some small molecule also play a marked role, such as high

mobility group box 1 (8), free

fatty acids (9) and advanced

glycation end products (AGEs) (10). For example, AGEs could induce the

activation of NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3)

inflammasome to promote IL-1β production and inflammatory response

in human chondrocytes (11).

These results indicate that the pathophysiology of OA is

complicated and the mechanism underlying the occurrence and

development of OA remains to be elucidated.

Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRP) is a

172-amino acid protein and belongs to a family of cold-shock

proteins. The mature CIRP peptide contains one RNA recognition

motif domain in the N-terminal and one glycine-rich C-terminal

domain. CIRP was first identified as an RNA binding protein and is

lowly expressed in various tissues (12,13). It is a stress-inducible protein

which responds to a number of stresses, including hypoxia and UV

radiation. The stress-induced CIRP regulates target genes

expression through binding and stabilizing them (14,15). It has been reported that CIRP is

a new damage-associated molecular pattern molecule (DAMP) and can

function as an inflammatory mediator (16). Qiang et al (17) found that hypoxia stress could

induce CIRP secretion, the extracellular CIRP working as a DAMP to

promote inflammatory response in shock and sepsis. Sakurai et

al (18) reported that CIRP

increases the expression of TNF-α and IL-32, linking inflammation

and tumorigenesis in colitis-associated cancer. In cerebral

ischemia, CIRP activates the NF-κB signaling pathway, promotes the

TNF-α expression and mediates neuroinflammation (19). NLRP3 inflammasomes are key

regulators of inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of OA

(20-22). The activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome leads to the cleavage of caspase-1, which processes

pro-IL-1β into its mature form, IL-1β. This mature cytokine is then

secreted and further amplifies the inflammatory response (23). It has been reported CIRP can

trigger an inflammatory response through the Toll-like receptor 4

(TLR4)/NF-κB signaling pathway (17,24). The assembly of TLR4/NF-κB and

NLRP3/ASC/procaspase-1 complexes contributes to the activation of

canonical NLRP3 inflammasome signaling (25). Furthermore, CIRP has been

evaluated in the synovial fluid of OA and rheumatoid arthritis,

indicating a positive relationship between CIRP and OA (26,27). However, the roles of CIRP in OA

progression and the underlying mechanism remain to be

elucidated.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a cluster of short non-coding

RNAs with an average length of 22 nucleotides. They suppress target

genes expression by binding to their 3'-UTRs. Studies have

indicated that miRNAs play critical roles in maintaining cartilage

homeostasis as well as clinical treatment of OA (28,29). For example, miR-92a-3p enhances

chondrogenesis and suppresses cartilage degradation by targeting

WNT5A (30). As cell-secreted

nanovesicles, exosomes contain multiple types of cargo, including

non-coding RNA molecules, DNA, lipids and functional proteins.

Recent evidence has suggested that exosomes play a novel function

as attractive carriers for gene therapy or drug delivery (31). For example, exosome-mediated

miR-144-3p promotes ferroptosis to inhibit osteosarcoma

proliferation, migration and invasion by regulating ZEB1 (32). Moreover, umbilical cord

blood-derived M1 macrophage exosomes loaded with cisplatin reversed

cisplatin resistance of ovarian cancer in vivo (33). These studies indicate that

exosomes are novel carriers capable of delivering RNA molecules or

drugs to target cells, representing a potential strategy for OA

treatment.

The present study aimed to investigate the function

and molecular mechanisms of CIRP in OA progression. It also sought

to explore how CIRP regulates the inflammatory response and

extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation in human chondrocytes

through the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome. Additionally, it

identified CIRP as a target of miRNA-145-5p (miR-145-5p), a

microRNA previously shown to have protective effects in

chondrocytes and nucleus pulposus cells (34-36). This led the present study to

further examine whether miR-145-5p could prevent OA development by

targeting CIRP.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Human recombinant CIRP peptides were purchased from

Abcam. NF-κB inhibitor BAY 11-7082 and cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8)

was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. TLR4

inhibitor TAK-242 was purchased from Shanghai Xianding

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Primary antibodies directed against

inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2),

MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, Lamin B1, CD63, CD9, 130 kDa cis-Golgi matrix

protein 1 (GM130) and GAPDH were purchased from Proteintech Group,

Inc., ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 5

(ADAMTS5) was purchased from ABclonal. Human Reactive Inflammasome

Antibody Sampler Kit II, CIRP, IκBα and p65 were purchased from

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Collagen II was purchased from

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked

antibody and Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody were purchased

from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology.

Preparation and culture of human primary

chondrocytes

The collection of cartilage tissues from patients

was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Second People's

Hospital (2023-157-01YJ). Samples used in this study were collected

after all patients received detailed explanation of the research

and submitted written informed consents. Human articular cartilage

tissues were obtained from volunteer donors who had undergo joint

replacement or joint surgery (December 2023-September 2024). Normal

chondrocytes were obtained from the articular cartilage of patients

who underwent joint replacement surgery due to femoral neck

fractures. Notably, these patients did not have a diagnosis of OA.

The control group comprised 11 patients (5 males and 6 females),

all aged from 60-74 years old. By contrast, OA chondrocytes were

sourced from the articular cartilage of individuals diagnosed with

OA, comprising 11 patients (3 males and 8 females), also aged from

60 to 81 years old. Washing the cartilage samples 3 times with

phosphate buffer saline (PBS) containing penicillin and

streptomycin and then cutting them into small fragments (1-3

mm3). The minced samples were placed in 1 mg/ml

collagenase II (MilliporeSigma) for digestion at 37°C for 16 h in a

shaker, digesting the samples multiple times until collagen was

completely dissolved. After digestion, the suspension was filtered

with a 100-mm nylon cell strainer to remove matrix debris and the

cells collected via centrifugation at 108 × g for 10 min at 24°C.

After centrifugation, cells were resuspended and subcultures with

chondrocyte growth medium (DMEM/F12; 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml

streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells

were cultured in an incubator with 5% CO2 atmosphere at

37°C. The medium was changed when the cell was attached and the

cells were passaged at 80% confluence. Only the passage 1(P1) and

passage 2 (P2) chondrocytes were used for the experiments.

Toluidine blue staining was used to assess chondrocyte morphology.

Briefly, the samples were stained with toluidine blue solution for

5 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of an equal

volume of distilled water and mixed thoroughly. After allowing the

mixture to stand for 10 min at room temperature, images were

captured using an Olympus microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Cell viability

Human primary chondrocytes cells were seeded in

96-well cell culture plates at a density of 1×104/well

and cultured overnight. The concentration range of BAY 11-7082 and

TAK-242 used in this assay was based previous studies (37,38). The concentration range of CIRP

used in this assay was from 0-8 μg/ml. After incubation with

CIRP for 48 h at 37°C, the cell viability was measured using CCK-8

following the standard protocol. Briefly, the culture medium and

CCK-8 solution were mixed at a ratio of 10:1 and 100 μl

mixture was added into each well. After 1 h incubation at 37°C in a

cell culture incubator, the absorbance at 450 nm was detected using

a microplate reader.

RNA isolation, reveres transcription and

reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

Total RNA was extracted from human chondrocytes

using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In

brief, the cells were first lysed in TRIzol® to release

the RNA, and then chloroform was added to facilitate phase

separation. After mixing and centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15

min at 4°C, the upper aqueous phase containing the RNA was

transferred to a new tube. Isopropanol was subsequently added to

precipitate the RNA. The RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol,

dried and finally resuspended in RNase-free water. Then cDNA was

synthesized using PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser

(Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. RT-qPCR was conducted with SYBR Green Supermix

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) using aViiA 7 Real-Time PCR

System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR cycling

conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min,

followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing

at 60°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 30 sec. Transcript

levels were normalized to GAPDH (for mRNA) or the small U6 RNA (for

miRNA). The specific primers used for these analyses are listed in

Table I. Gene expression was

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (39) and each experiment was performed

in triplicate.

| Table ISequences of primers for PCR. |

Table I

Sequences of primers for PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer

(5'-3') | Reverse primer

(5'-3') |

|---|

| iNOS |

CCTTACGAGGCGAAGAAGGACAG' C |

AGTTTGAGAGAGGAGGCTCCG |

| COX-2 |

GAGAGATGTATCCTCCCACAGTCA |

GACCAGGCACCAGACCAAAG |

| IL-6 |

ACTCACCTCTTCAGAACGAATTG CC |

ATCTTTGGAAGGTTCAGGTTG |

| TNF-a |

GTCAGATCATCTTCTCGAACC |

CAGATAGATGGGCTCATACC |

| IL-1b |

ATGATGGCTTATTACAGTGGCAA |

GTCGGAGATTCGTAGCTGGA |

| MMP1 C |

TGTTCAGGGACAGAATGTGC |

TTGGACTCACACCATGTGTT |

| MMP3 |

TGCGTGGCAGTTTGCTCAGCC |

GAATGTGAGTGGAGTCACCTC |

| MMP13 |

GGCTCCGAGAAATGCAGTCTTTCTT |

ATCAAATGGGTAGAAGTCGCCATGC |

| Adamts5 |

GAACATCGACCAACTCTACTCCG C |

AATGCCCACCGAACCATCT |

| Aggrecan |

GTGCCTATCAGGACAAGGTCT |

GATGCCTTTCACCACGACTTC |

| Collagen II |

CTGTCCTTCGGTGTCAGGG |

CGGCTTCCACACATCCTTAT |

| CIRP C |

AAGTACGGACAGATCTCTG |

CGGATCTGCCGTCCATCTA |

| miR-145-5p |

GTCCAGTTTTCCCAGGAATC |

AGAACAGTATTTCCAGGAAT |

| U6 |

CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACATATACT |

ACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGTGTC |

| GAPDH |

GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT |

GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

Western blotting

The whole cell proteins were extracted from

chondrocytes using lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM

NaCl and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) with protease inhibitors

supplement. Separate extraction of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins

was conducted using a Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction

Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The determination of

protein concentration was conducted using the BCA protein

concentration detection kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Denatured protein solution (40 μg) was subjected to 12%

SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis. The sample was then

transferred to a PVDF membrane (Merck KGaA) that had been incubated

in methanol for 1 min at room temperature. After removing the

methanol, the membrane was equilibrated in transfer buffer until it

was ready for use. Following a transfer at 100 V for 1 h at 4°C,

the membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room

temperature before being incubated with primary antibodies against

GADPH (1:50,000; cat. no. 60004-1-Ig; ProteinTech Group, Inc.),

MMP1 (1:1,000, 10371-2-AP, ProteinTech Group, Inc.), MMP3 (1:5,000;

cat. no. 66338-1-Ig; ProteinTech Group, Inc.), MMP13 (1:1,000; cat.

no. 18165-1-AP; ProteinTech Group, Inc.), a disintegrin and

metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motif-5 (Adamts5; 1:500; cat.

no. A2836; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), iNOS (1:500; cat. no.

18985-1-AP; ProteinTech Group, Inc.), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2;

1:500; cat. no. 12375-1-AP; ProteinTech Group, Inc.), lamin B1

(1:5,000; cat. no. 12987-1-AP; ProteinTech Group, Inc.), CD63

(1:500; cat. no. 32151-1-AP, ProteinTech Group, Inc.), CD9 (1:500;

cat. no. 84801-13-RR, ProteinTech Group, Inc.), GM130 (1:500; cat.

no. 11308-1-AP, ProteinTech Group, Inc.), Human Reactive

Inflammasome Antibody Sampler Kit II (1:1,000; cat. no. 25620T;

Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), CIRP (1:1,000; cat. no. 68522;

Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), p65 (1:1,000; cat. no. 8242; Cell

Signaling Technology Inc.), IκBα (1:1,000, cat. no. 4814; Cell

Signaling Technology Inc.), and collagen II (1:500; cat. no.

AF6528, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C.

Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with a HRP-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit (1:1,000; cat. no. A0208; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology Inc.) or goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000; cat. no.

A0216; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology Inc.) secondary antibody

for 2 h at room temperature. ECL reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) was used for development according to the manufacturer's

protocol. The semi-quantitatively analysis of immunoreactive bands

was performed using ImageJ software 1.53e (National Institutes of

Health).

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence, cells were treated with CIRP

for 24 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min

at room temperature. Fixed samples were permeabilized with 0.3%

Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature and then blocked with

5% BSA for 30 min. Chondrocytes were incubated with p65 (1:50)

primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Afterwards, they were washed

with PBS 3 times and incubated with Cy3-conjugated secondary

antibodies for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Finally, the

cells were incubated with DAPI for nucleuses stain at room

temperature for 10 min. A fluorescence microscope was used to

acquire the images at a magnification of 400×. Collagen II (1:50)

and MMP13 (1:50) primary antibody were used to detect its

expression in human chondrocytes using the same immunofluorescence

protocol, and a fluorescence microscope was used to acquire the

images at a magnification of 100×. The cell density seeded onto the

slide was 1×105 cells per well.

Purification of exosomes

Exosomes were harvested through a sequential

centrifugation method. Cells were cultured in serum-free medium for

48 h. The medium was collected and centrifuged sequentially at 300

× g for 10 min, at 2,000 × g for 15 min and at 10,000 × g for 30

min at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered using a 0.22 mm filter

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) to remove remaining cells and

debris and then centrifuged at 120,000 × g for 70 min at 4°C to

harvest exosomes. PBS was used to re-suspend the purified exosomes.

Exosomes were kept either at −80°C for long term preservation or at

−20°C for short term preservation.

Characterization of exosomes

Exosomes were entrusted to Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd. for transmission electron microscopy. In

brief, fix the exosomes with 1 ml of 2% paraformaldehyde for 5 min

at room temperature. Then, 10 μl of exosomes was applied to

carbon-coated copper grids for 1 min, then washed with

double-distilled water and dried using filter paper. Afterwards,

~15 μl of 2% uranyl acetate staining solution was added for

1 min at room temperature. The grids were examined using a Hitachi

HT7700 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies

Corporation). The particle size and particle concentration were

determined by a Nano sight Tracking Analysis (NTA) system NanoSight

NS300 (Malvern Panalytical Instruments Corp.). Briefly, exosomes

were re-suspended in PBS at a concentration of ~3 μg protein

content/ml. Then the solution was further diluted by 100 to 500

hundred folds for analysis. A 1 min video was recorded by the NTA

software (NTA 3.4-Sample Assistant Build 3.4.003-SA, Malvern

Panalytical Ltd.) for further analysis. Western blotting was used

to detect the exosome marker protein expression.

Construction of a Venn diagram of CIRP

targeting micro-RNAs

To predict the miRNAs that could potentially

regulate CIRP expression, the miRWalk (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/), TargetScan

(http://www.targetscan.org/), StarBase

(http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/), miRDIP

(http://ophid.utoronto.ca/mirDIP/) and a

chondrogenesis-related microRNA databases (GSE135588) were used to

find CIRP targeting miRNAs. A Venn diagram (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/cgi-bin/liste/Venn/calculate_venn.htpl)

was created based on comparisons of these miRNAs.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

To study the interaction between miR-145-5p and the

3' untranslated region (UTR) of the CIRP gene, plasmid vectors

containing the wild-type CIRP 3' UTR that included the predicted

binding sites for miR-145-5p were constructed. These plasmids were

transfected into 293 cells using GP-transfect-Mate (GenePharma,

Inc.). To evaluate transfection efficiency, a Renilla

luciferase vector was co-transfected in each experiment. After

transfecting the cells, incubate them in a 37°C incubator for 24 h,

the luciferase activity was measured in relative light units, with

the firefly luciferase activity normalized against the

Renilla luciferase activity using Dual-Luciferase Reporter

Assay System (Promega Corporation). In brief, 250 μl of 1X

cell lysis buffer was added to each well, and 50 μl of the

lysate transferred to a microplate, setting up three replicates.

Then, 10 μl of firefly luciferase reaction solution was

added, gently mixed, and the firefly luciferase activity measured

within 30 min. Finally, 30 μl of Renilla luciferase

reaction solution was added, mixed immediately and the

Renilla luciferase activity measured.

Loading exosomes with miRNA mimic

Electroporation method was used to load miR-145-5p

mimics into exosomes. Exosomes at a final concentration of 100

μg/μl protein (measured by BCA) were mixed with

electroporation buffer (in a 1:1 ratio) and 100 pmol of synthetic

miR-145-5p mimics (sense 5'-GUCCAGUUUUCCCAGGAAUCCCU-3', antisense

5'-GGAUUCCUGGGAAAACUGGACUU-3') or negative control (mimics NC,

sense 5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3', antisense

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3') and electroporated at 0.400 kV using

an electroporation instrument. After the loading of miR-145-5p

mimics, the exosome samples were diluted with PBS and centrifuged

at 10,000 × g for 30 min and 100,000 × g for 70 min at 4°C to

remove unloaded miR-145-5p mimics.

Establishment of a mice model of OA

All procedures were approved by the Animal Research

Committee of Southwest Medical University (approval no.

20220307-004). A total of 20 six-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were

randomized into four groups: normal group, OA group, miR-NC-Exos OA

group and miR-145-Exos OA group, with each group comprising five

mice. The OA model was built on the instability of the medial

meniscus (DMM) caused by surgical therapy (40). The normal and OA group were given

articular cavity injections of PBS. MiR-NC-Exos OA group were given

articular cavity injections of 100 μg exosomes from cells

overexpressed miR-NC mimics and miR-145-Exos OA group were given

articular cavity injections of 100 μg exosomes from cells

overexpressed miR-145 mimics. The injections were carried out twice

a week for four consecutive weeks. All animals were sacrificed via

cervical dislocation while under anesthesia induced by an

intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg).

Mortality was confirmed through the observation of respiratory

arrest. a total of 10 cartilage samples were collected for

safranin-O staining, hematoxylin and eosin staining and

immunohistochemical (IHC) staining.

Histopathological analysis

The calcification of the knee joint was removed with

a 10% EDTA solution after it had been fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde (24 h; 4°C). The tissue was then dehydrated by

immersing it in 70% ethanol for 30 min, followed by 80% ethanol for

30 min, 95% ethanol for 30 min, and finally 100% ethanol for 1 h to

ensure complete dehydration. After dehydration, the tissue was

cleared and placed in melted paraffin wax at approximately 60°C for

3 h, which was then transferred into a mold filled with fresh

paraffin wax to cool and solidify. The paraffin blocks were sliced

into frontal serial slices with a thickness of 5 mm. Hematoxylin

and eosin (H&E) staining was performed at room temperature,

with hematoxylin applied for 10 min, and eosin applied for 3 min.

Safranin O-fast green (S-O) staining was also performed at room

temperature, with safranin O staining lasting 5 min, and fast green

staining for 15 sec. And a light microscope was used to identify

the degree of cartilage degeneration.

Immunohistochemical assay

MMP3 and collagen II expression levels were detected

in the cartilage by immunohistochemistry. Briefly, the slides were

dewaxed and rehydrated. The slide was sealed with 5% BSA for 30 min

after a 20 min incubation with 0.4% pepsin (Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) in 5 mM HCl to repair the antigen. Then, with primary

antibodies specific to MMP3 (1:500) and collagen II (1:50)

overnight (at 4°C), incubation of the slides was performed. After

50 min (room temperature) of incubation, the slides were subjected

to incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:50; cat. no.

A0208; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Inc.) and images were

captured with an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus Corporation).

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

RNA-seq was conducted and analyzed by Genedenov Co.,

Ltd. Briefly, total RNA extraction from the cells was performed

using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and genomic DNA removal was performed with DNase

I (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). After preparation of the

RNA-seq transcriptome library, the Illumina HiSeq xten/NovaSeq 6000

sequencer (Illumina, Inc.) was used to perform RNA-seq. Gene

Ontology (GO) functional enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes

and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis were conducted using omicshare

(https://www.omicshare.com). The RNA-seq

dataset has been deposited in the BioProject database under the

accession number PRJNA1302182 and the URL is https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1302182.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as the mean ± SD and all

experiments were repeated three times with independent cultures.

Prior to statistical analysis, the normality of the data

distribution was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The

statistical significance of differences for the mean values between

two groups was determined with an unpaired two-tailed Student's

t-test and multiple groups compared using one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

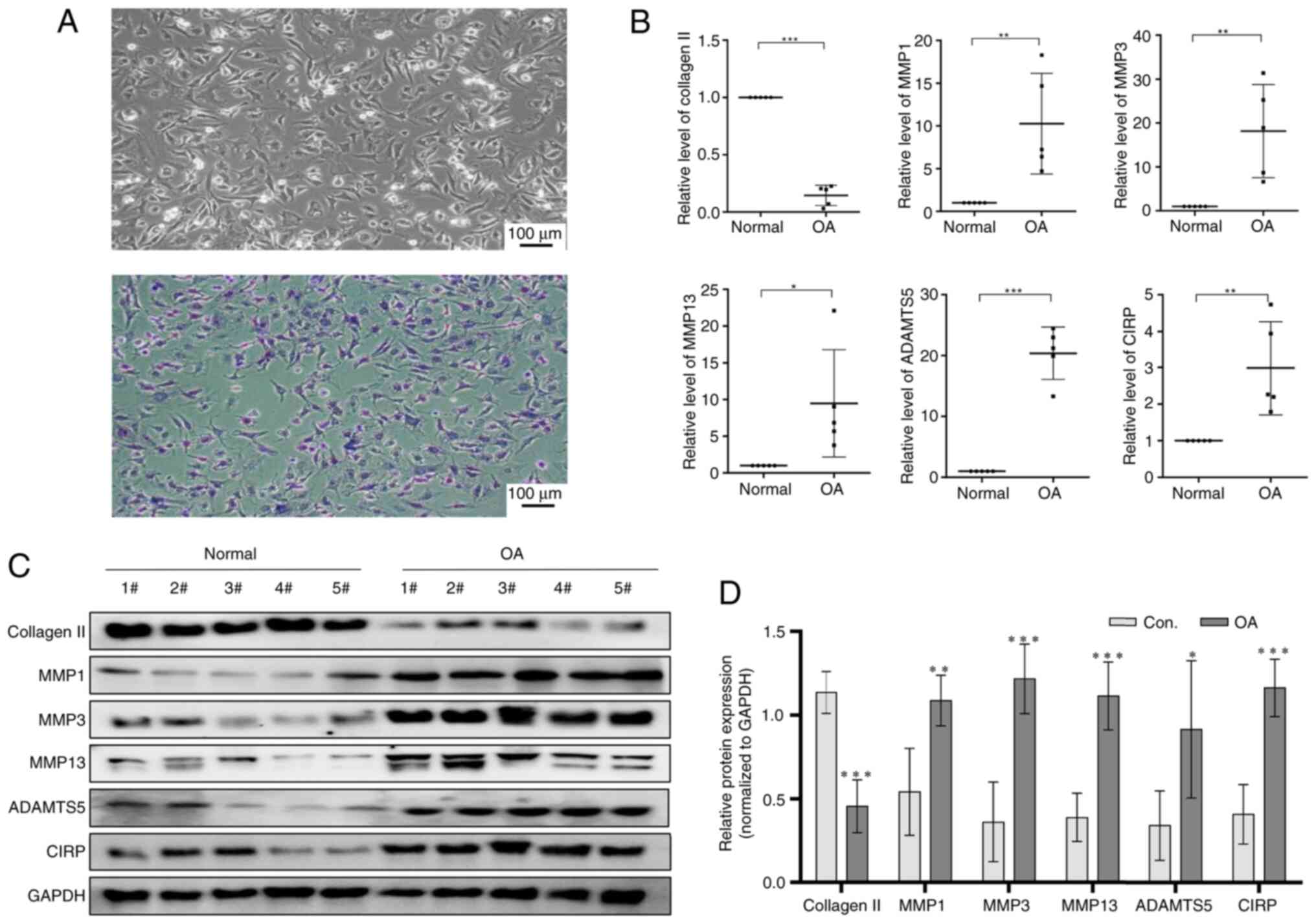

Overexpression and secretion of CIRP in

OA human chondrocytes

To assess the effect of CIRP on OA progression,

chondrocytes were first collected from patients with fractures or

OA undergoing joint replacement surgery to evaluate its expression.

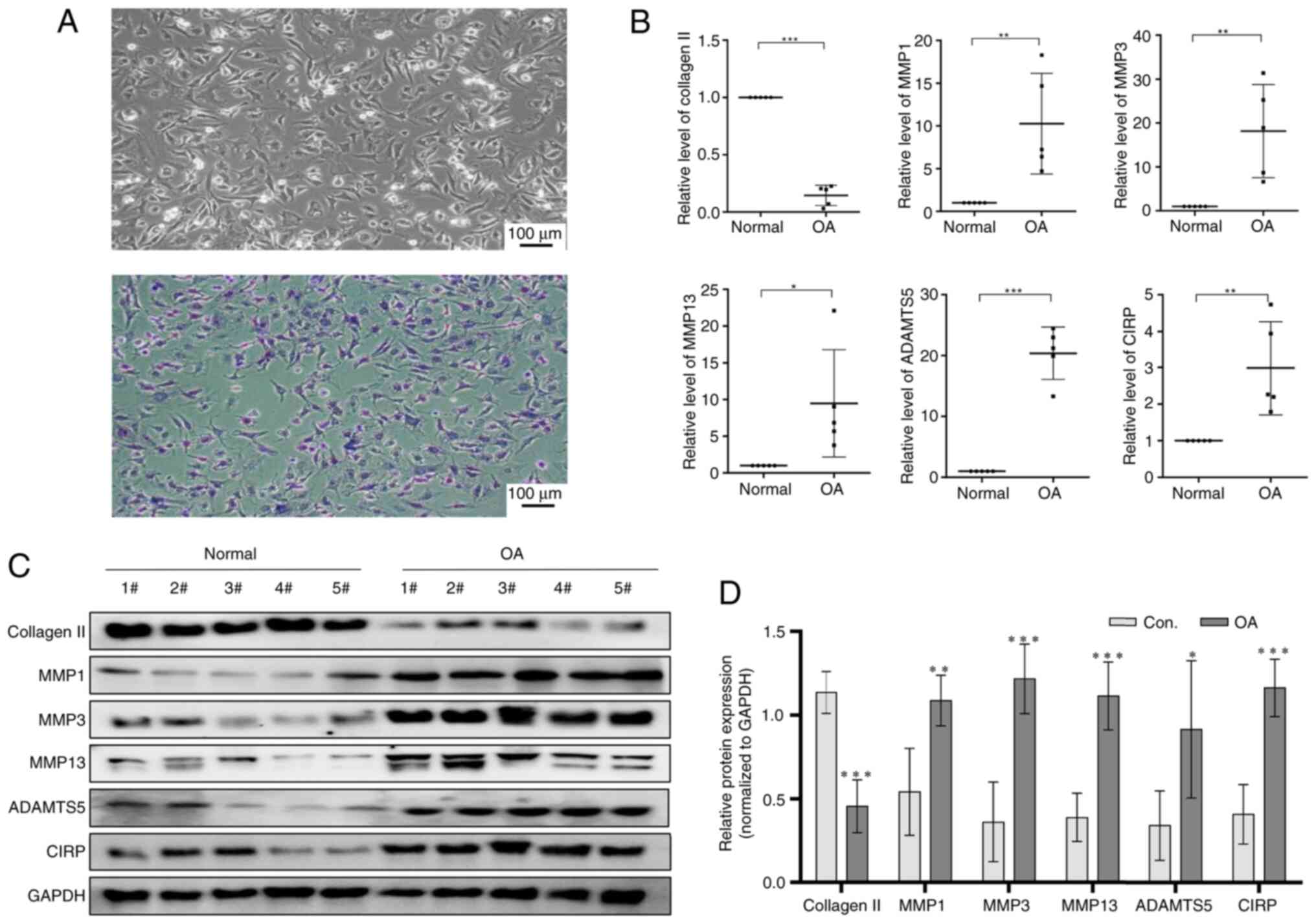

As shown in Fig. 1A, the

extracted human chondrocytes were stained with toluidine blue,

confirming that the isolated cells were indeed human chondrocytes

and suitable for further study. In Fig. 1B, qPCR analysis revealed that the

expression of CIRP was markedly increased, while collagen Ⅱ levels

decreased in OA chondrocytes compared with normal chondrocytes.

Additionally, the expression of MMP1, MMP3, MMP13 and ADAMTS5 were

also overexpressed in OA chondrocytes. The present study then

analyzed the protein levels of these genes and the data presented

in Fig. 1C and D supported the

mRNA findings. These results indicated that CIRP is overexpression

in OA chondrocytes and may contribute to the progression of OA.

| Figure 1CIRP expression in chondrocytes from

healthy individuals and OA patients. (A) Trypan blue staining of

chondrocytes. (B) Representative quantitative PCR showing the

expression of CIRP, collagen Ⅱ, MMP1, MMP3, MMP13 and ADAMTS5 in

chondrocytes from healthy individuals and OA patients. (C and D)

Western blotting showing the expression of CIRP, collagen Ⅱ, MMP1,

MMP3, MMP13 and ADAMTS5 in chondrocytes from healthy individuals

and OA patients. (n=5), *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. CIRP,

cold-inducible RNA-binding protein; OA, osteoarthritis; MMPs,

matrix metalloproteinases; ADAMTS5, ADAM metallopeptidase with

thrombospondin type 1 motif 5. |

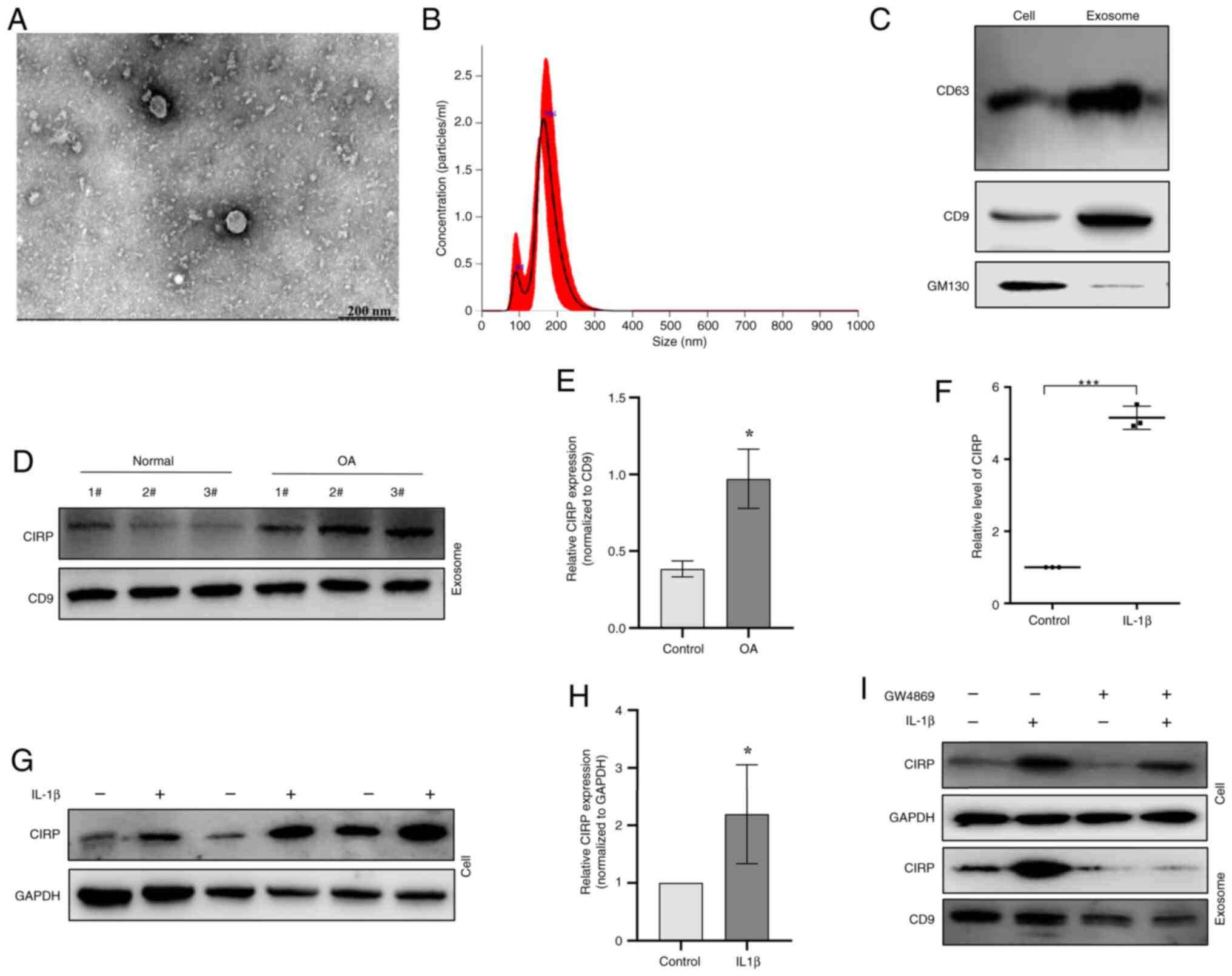

Secretion of CIRP in OA human

chondrocytes via exosomes

Recent studies revealed that CIRP can be released

into extracellular space by various cell types, including

cardiomyocytes (41-43). The exosomes released by OA

chondrocytes were next collected and analyzed using TEM (Fig. 2A). The observations indicated

that the exosomes derived from chondrocytes were round or

oval-shaped with uneven sizes and ranging in diameter from 150-200

nm (Fig. 2B). Western blotting

revealed positive expression of CD63 and CD9, along with negative

expression of GM130 in the exosomes (Fig. 2C). It was then examined whether

CIRP was present in chondrocyte-derived exosomes. The western

blotting results showed that chondrocyte exosomes indeed contained

CIRP and its expression was markedly increased in OA chondrocytes

compared with normal chondrocytes (Fig. 2D and E). Moreover, treatment of

chondrocytes with 10 ng/ml IL-1β also resulted in an increase in

CIRP expression (Fig. 2F-H).

Furthermore, the exosome release inhibitor GW4869 suppressed the

secretion of CIRP in human chondrocytes (Fig. 2I). These results indicate that

CIRP is overexpressed and released in an exosomal manner in OA

chondrocytes, which may contribute to the progression of OA.

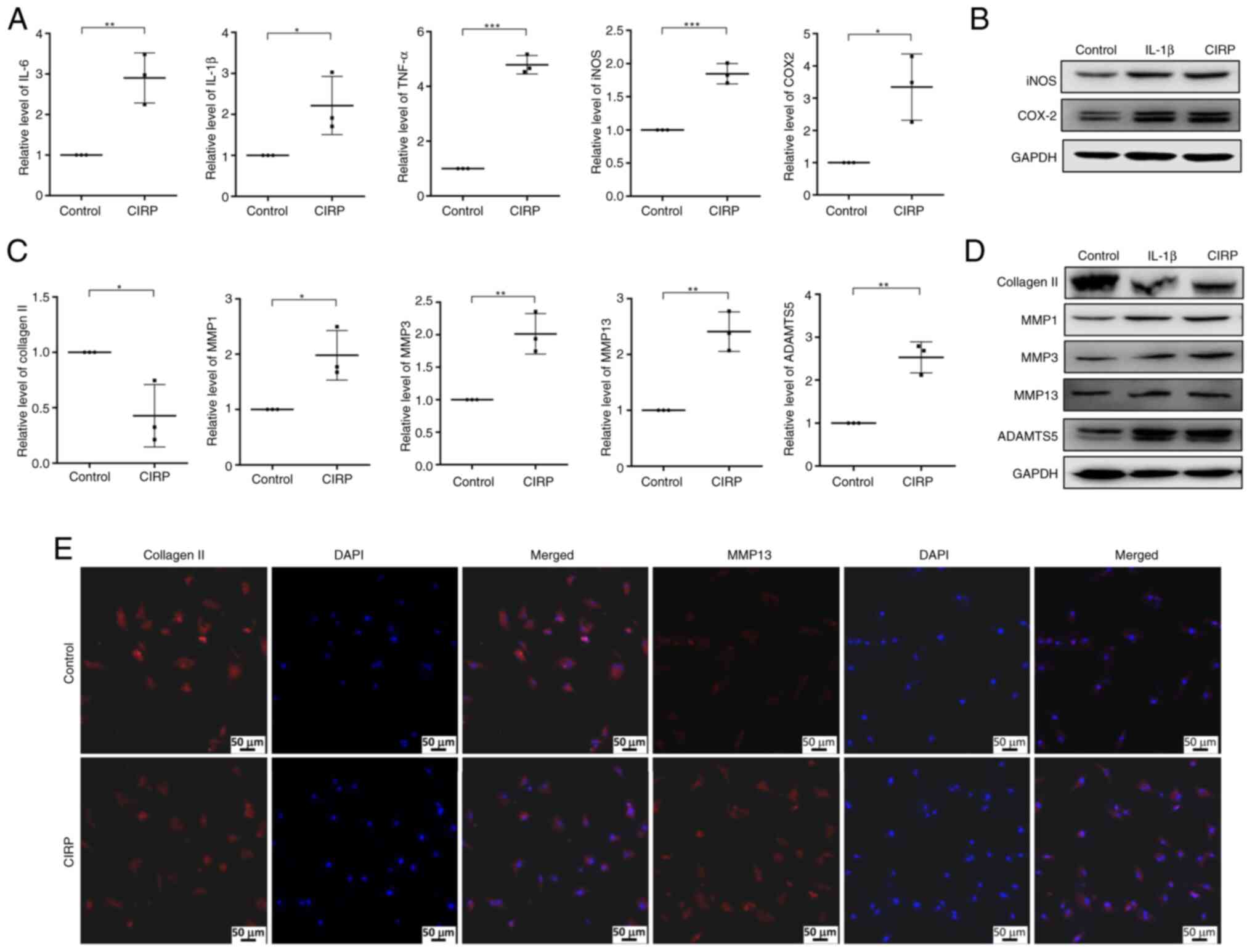

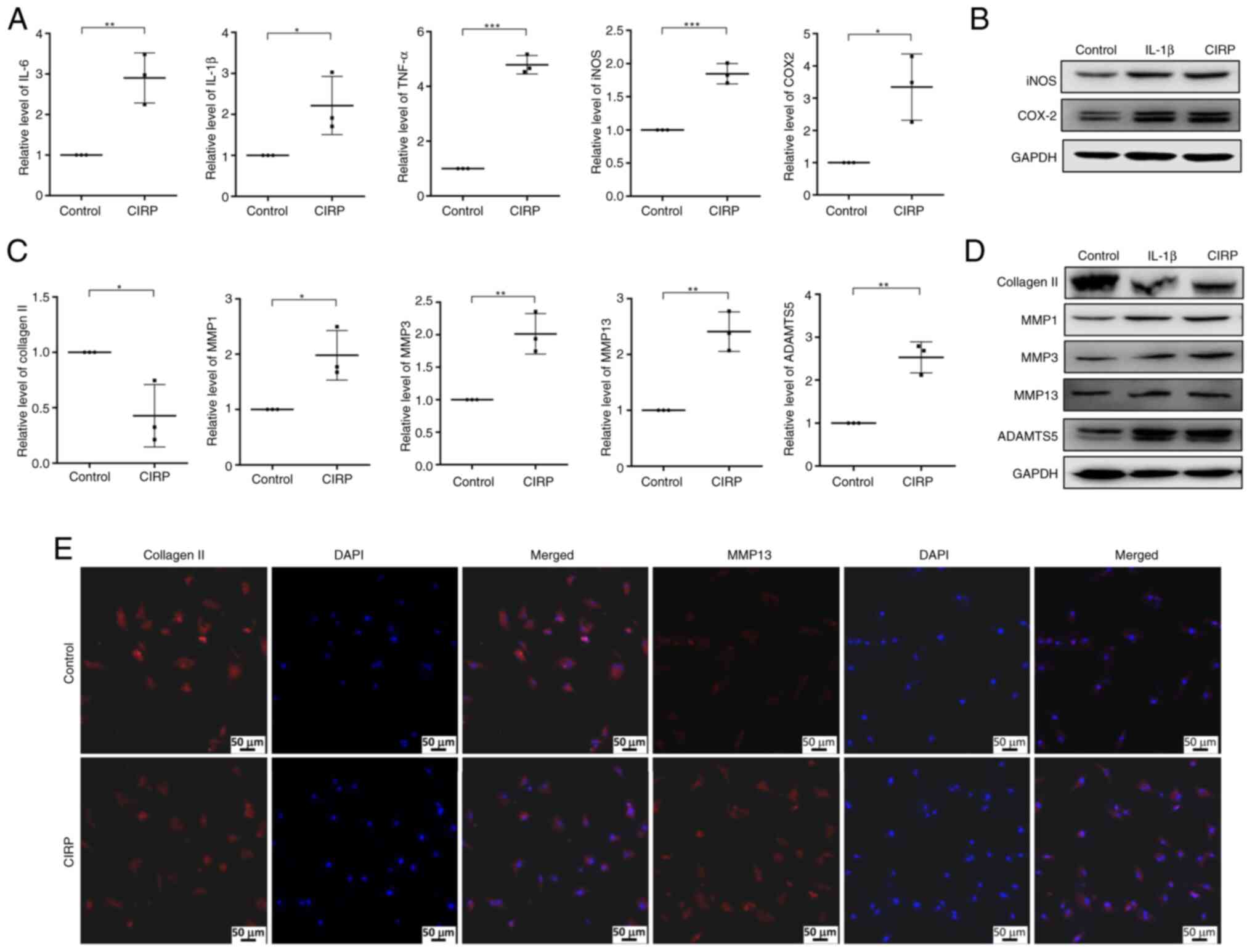

CIRP enhances inflammatory cytokine

expression and ECM degradation in chondrocytes

From the aforementioned results, it was observed

that the expression of CIRP was upregulated in human OA

chondrocytes. This upregulation was associated with increased

expression of inflammatory cytokines and MMPs, suggesting that CIRP

may play a role in progression of OA. OA progression is strongly

associated with inflammatory responses and ECM degradation in

chondrocytes. To study the role of CIRP in OA, chondrocytes were

treated with CIRP concentrations ranging from 0-8 μg/ml. It

was found that 4 μg/ml CIRP did not affect cell viability,

while 8 μg/ml CIRP did (data not shown). Therefore, the

present study chose to use 4 μg/ml CIRP to treat

chondrocytes and analyze its effect on inflammatory cytokines

expression. The results demonstrated that CIRP treatment increased

the expression of IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα (Fig. 3A). Additionally, the expression

of iNOS and COX-2, two crucial inflammatory response factors in OA,

was also markedly upregulated following CIRP treatment (Fig. 3A and B). The present study then

examined the effect of CIRP on the expression of extracellular

matrix proteins. As shown in Fig.

3C, treatment with 4 μg/ml CIRP markedly decreased

collagen Ⅱ expression and increased the expression of MMP1, MMP3,

MMP13 and ADAMTS5 at mRNA level. The western blotting results in

Fig. 3D also showed that CIRP

induced the upregulation of MMP1, MMP3, MMP13 and ADAMTS5, along

with the downregulation of collagen II, with IL-1β treatment

serving as a positive control. Furthermore, Immunofluorescence

results indicated that collagen Ⅱ expression was markedly reduced,

while MMP13 expression was induced by CIRP treatment (Fig. 3E).

| Figure 3CIRP promotes inflammatory response

and ECM degradation in human chondrocytes. (A) Quantitative PCR

analysis showing the effect of CIRP on the expression of

inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, iNOS and

COX-2. (B) Western blotting showing the protein expression of iNOS

and COX-2. (C and D) Quantitative PCR and western blotting showing

the effect of CIRP on the expression of MMP1, MMP3, MMP13, ADAMTS5

and collagen Ⅱ. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis of collagen Ⅱ and

MMP13 expression following CIRP treatment, with DAPI staining for

nuclei (scale bar, 50 μm). n=3, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. CIRP,

cold-inducible RNA-binding protein; ECM, extracellular matrix;

iNOS, nitric oxide synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; MMPs, matrix

metalloproteinases; ADAMTS5, ADAM metallopeptidase with

thrombospondin type 1 motif 5. |

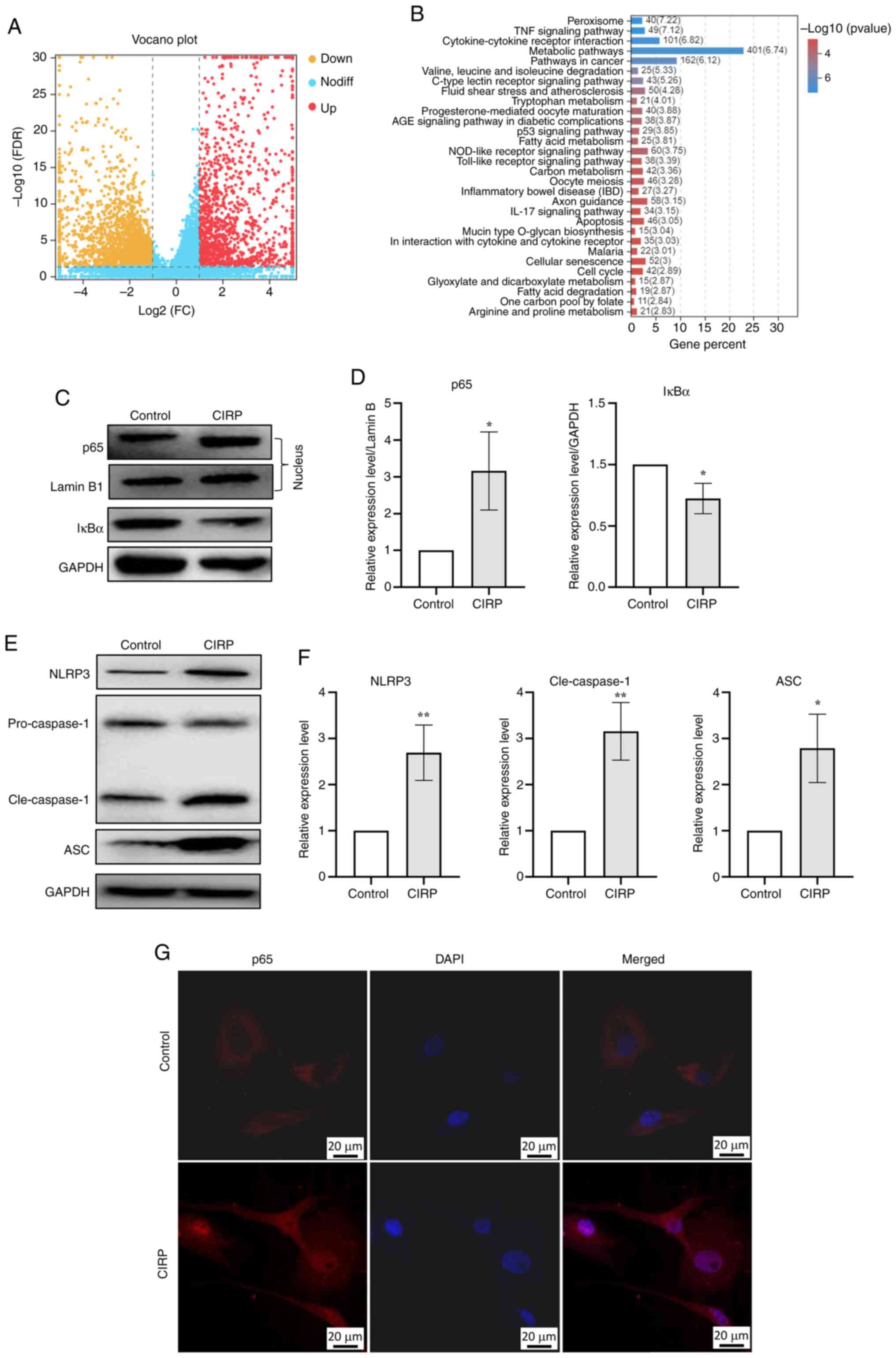

CIRP-induced inflammatory response and

ECM degradation dependent on TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling

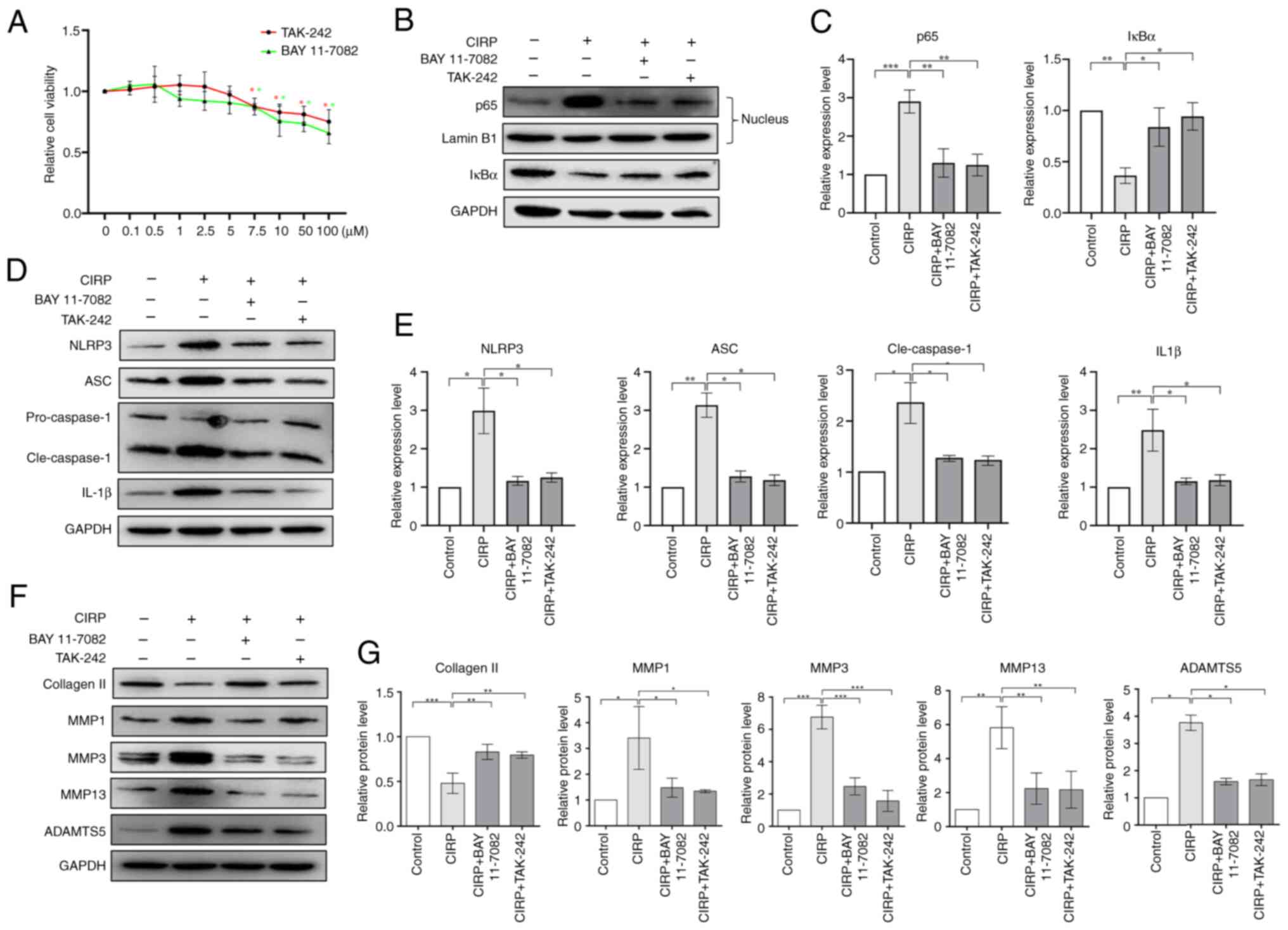

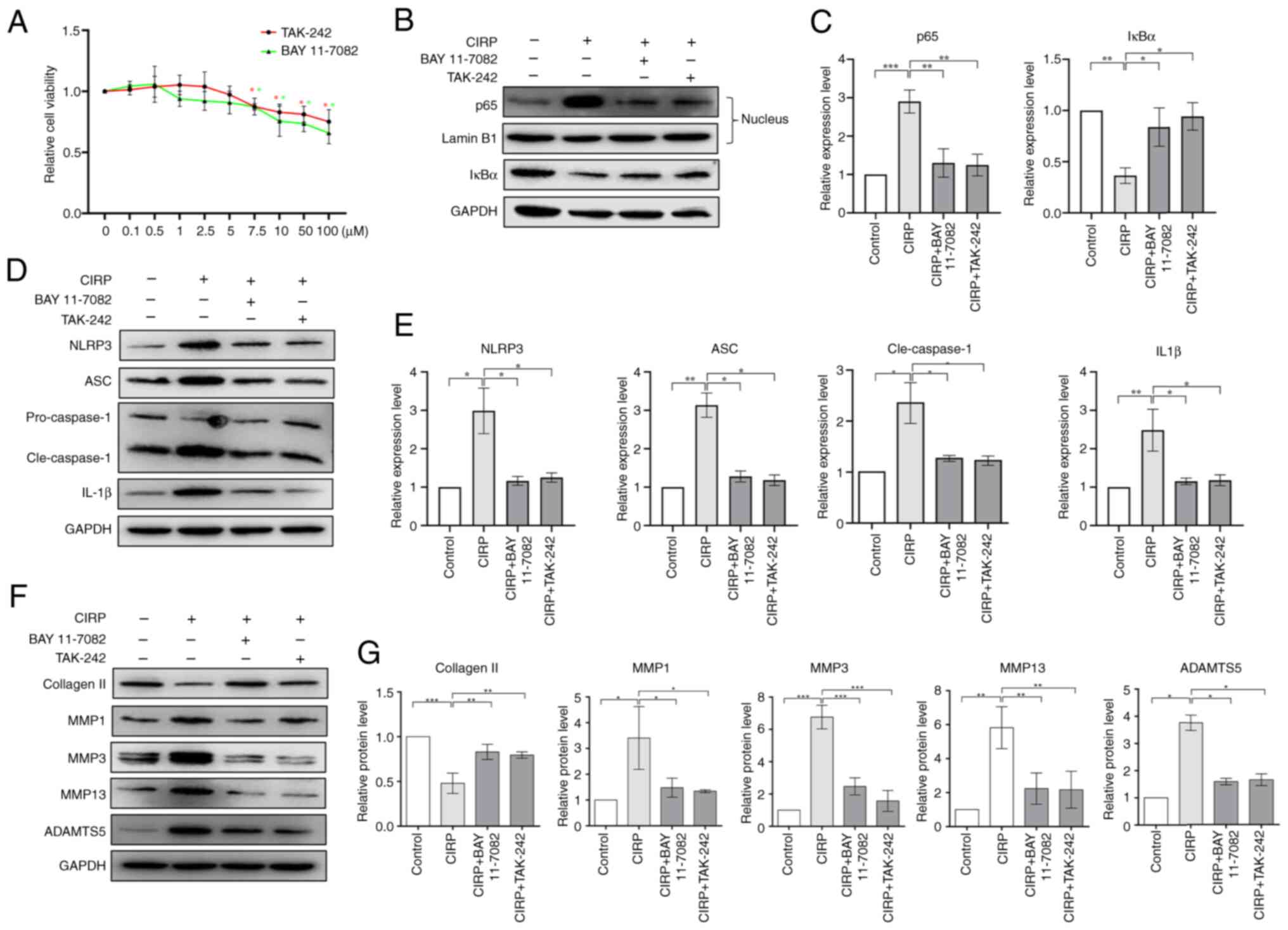

Next, chondrocytes were treated with 4 μg/ml

CIRP and cells were collected for RNA-seq. Fig. 4A shows the genes affected by CIRP

treatment. KEGG signaling pathway enrichment analysis indicated

that the differentially expressed genes were highly enriched in

functions related to inflammatory processes, including TNF-α

signaling, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, NOD-like

receptor signaling and Toll-like receptor signaling pathways

(Fig. 4B). The activation of

NF-κB signaling pathway plays crucial roles in the inflammatory

response and cartilage degradation associated with OA. Studies have

reported that CIRP can activate the NF-κB signaling pathway via

TLR4/MD2. The present study found that 4 μg/ml CIRP

increased the expression of p65 in the nucleus and promoted the

degradation of IκBα (Fig. 4C and

D). It was observed that CIRP markedly induced the nuclear

translocation of p65 in chondrocytes (Fig. 4G). These results demonstrate that

CIRP induces NF-κB activation in human chondrocytes. The present

study also analyzed the activation of NF-κB downstream NLRP3

inflammasome signaling pathway and the results showed that CIRP

induced the upregulation of NLRP3, ASC and cleaved-caspase1

(Fig. 4E and F).

It has been reported that extracellular CIRP

stimulates inflammatory responses by activating its receptors,

including TLR4, IL-6R and TREM-1 (41,44,45). Based on the RNA-seq analysis, the

present study sought to determine whether inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB

signaling pathway would eliminate CIRP's function. The inhibitors

BAY 11-7082 and TAK-242 were used to block the TLR4/NF-κB signaling

pathway. Fig. 5A shows their

toxicity on human chondrocytes. Next, chondrocytes were pretreated

with 5 μM BAY 11-7082 or TAK-242 and then treated with 4

μg/ml CIRP to analyze the effects of NF-κB signaling pathway

inhibition on CIRP. The results in Fig. 5B and C indicate that treatment

with 5 μM BAY 11-7082 and TAK-242 inhibited the activation

of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Furthermore, these two inhibitors

suppressed CIRP-induced activation of the NLRP3 signaling pathway

(Fig. 5D and E). Additionally,

these two inhibitors suppressed CIRP-induced downregulation of

collagen Ⅱ and upregulation of MMP1, MMP3, MMP13 and ADAMTS5

(Fig. 5F and G). These results

indicate that CIRP-induced inflammatory responses and ECM

degradation in human chondrocytes are dependent on the

TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway.

| Figure 5Dependence of CIRP-induced

chondrocyte damage on TLR4/NF-κB signaling. (A) Cytotoxicity of BAY

11-7082 and TAK-242 on chondrocytes at various concentration for 48

h, assessed using a CCK-8 assay. (B and C) Western blotting showing

the protein expression of IκBα in chondrocytes and p65 in the

nucleus of chondrocytes following treatment with the two

inhibitors. (D and E) Western blotting showing the protein

expression NLRP3, cleaved-caspase-1, ASC and IL-1β following

treatment with the two inhibitors. (F and G) Western blotting

showing the expression of extracellular matrix proteins in

chondrocytes following treatment with the two inhibitors. n=3,

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. CIRP, cold-inducible RNA-binding protein;

TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3; Cle, cleaved. |

CIRP as a putative target of

miR-145-5p

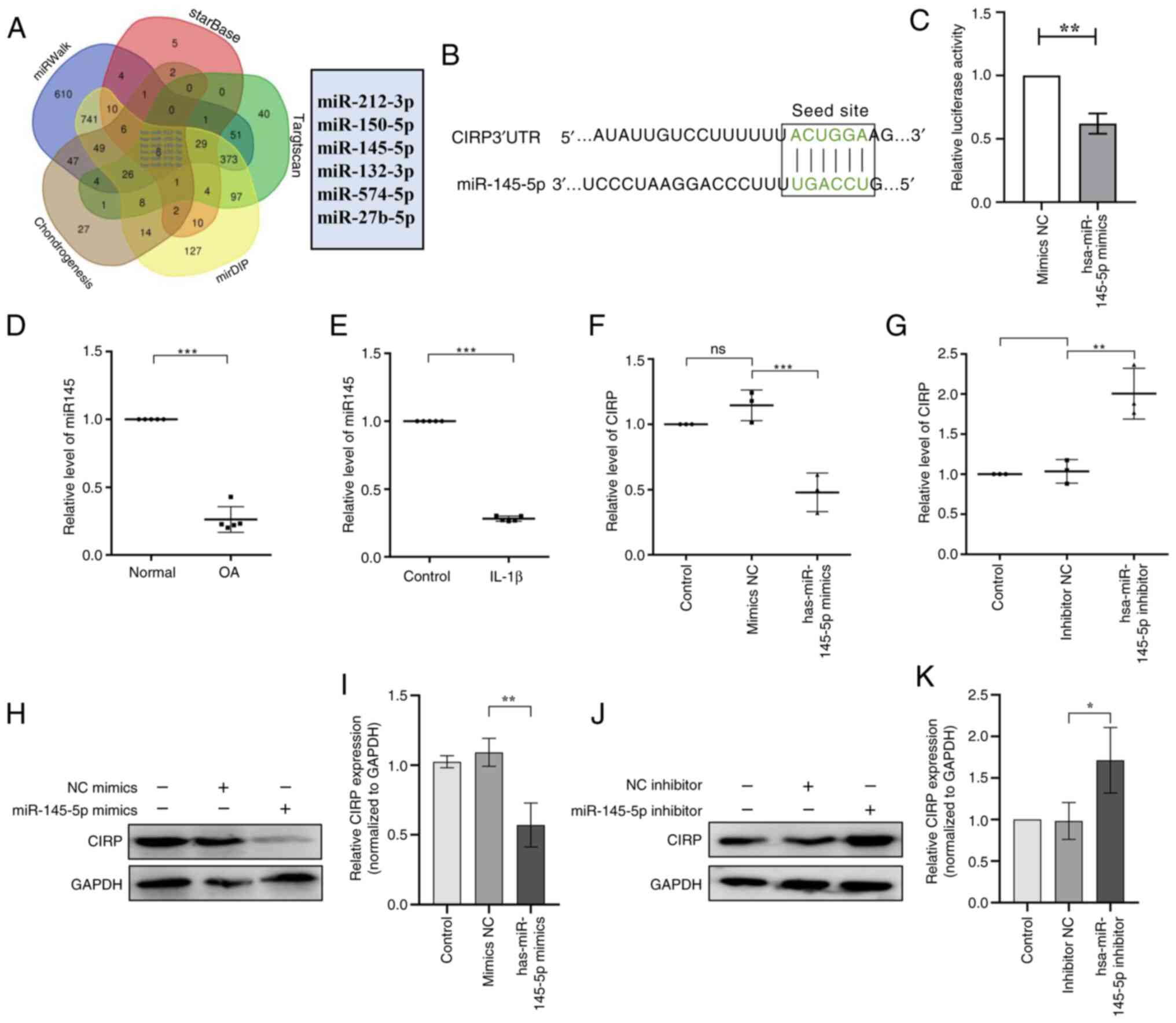

Subsequently, miRWalk, TargetScan, StarBase, miRDIP

and a chondrogenesis-related microRNA databases were applied to

predict the miRNAs that could potentially regulate CIRP expression.

A Venn diagram was created based on comparisons of these miRNAs

(Fig. 6A), which revealed six

candidate miRNAs of interest. Among them, has-miR-145-5p has been

reported to play an important role in chondrogenesis (34-36). Therefore, it was hypothesized

that miR-145-5p could influence OA progression by targeting CIRP.

To validate this hypothesis, online tools indicated the presence of

specific binding sites between CIRP mRNA and miR-145-5p (Fig. 6B), suggesting that CIRP might be

a downstream target gene of miR-145-5p. Moreover, a dual luciferase

reporter gene assay showed that, compared with the NC-mimic

control, luciferase activity decreased after the introduction of

miR-145-5p mimic and the CIRP-WT reporter plasmid (Fig. 6C). Next, the expression of

miR-145-5p in OA human chondrocytes and IL-1β treated human

chondrocytes was analyzed by qPCR. The results revealed that the

miR-145-5p expression was reduced in OA chondrocytes compared with

normal chondrocytes. Moreover, chondrocytes treated with IL-1β

exhibited lower miR-145-5p expression compared with untreated

chondrocytes (Fig. 6D and E).

Subsequently, the expression of CIRP in human chondrocytes treated

with miR-145-5p mimic or miR-145-5p inhibitor was assessed. The

results revealed that miR-145-5p mimic led to increased miR-145-5p

expression (Fig. S1A) and decreased CIRP expression (Fig. 6F, H and I), whereas the

miR-145-5p inhibitor decreased miR-145-5p (Fig. S1B) induced the opposite effects

(Fig. 6G, J and K). Taken

together, these results indicated that miR-145-5p is downregulated

in OA and specifically binds to and suppresses CIRP expression.

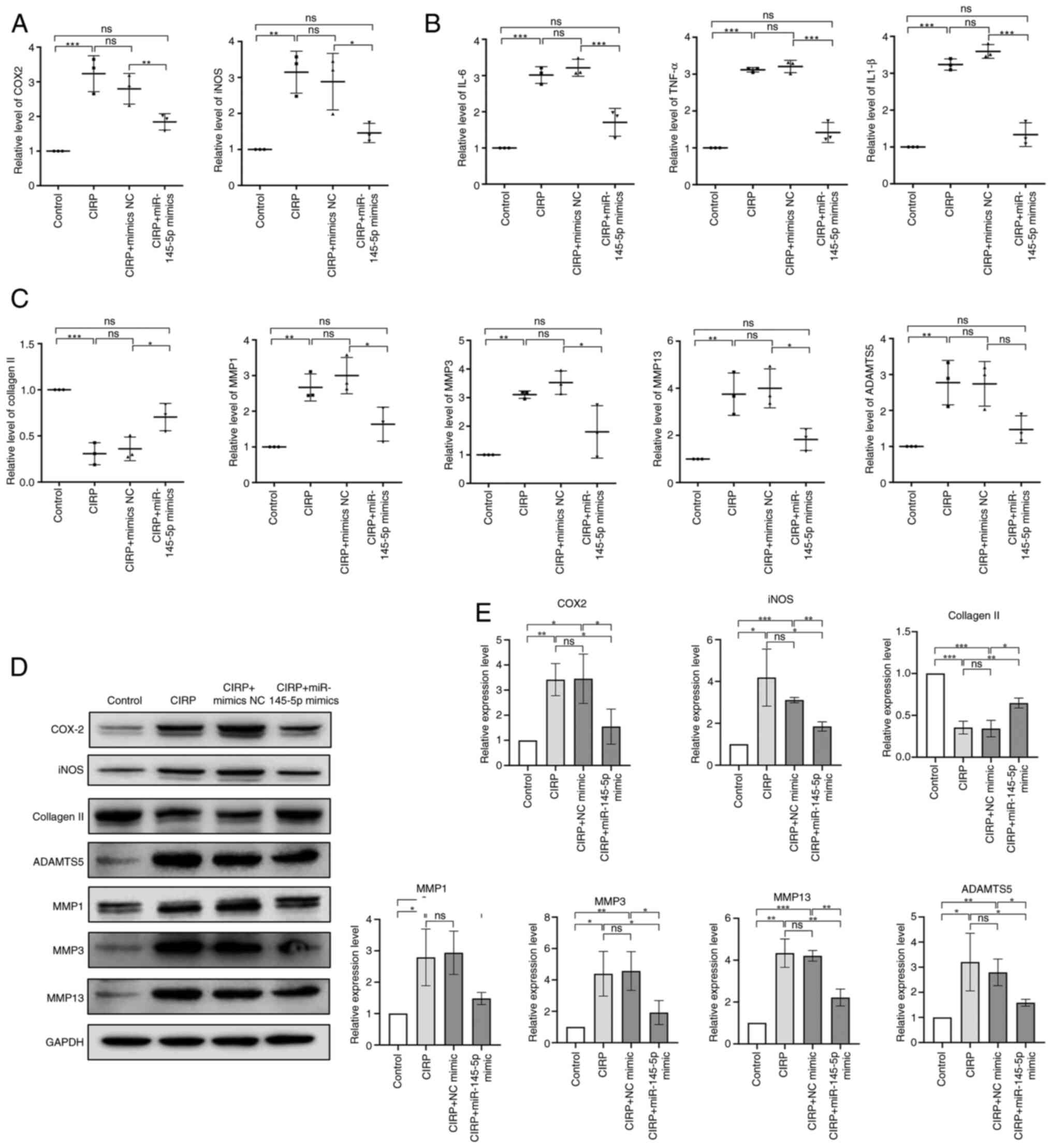

miR-145-5p maintains chondrocyte function

in vitro

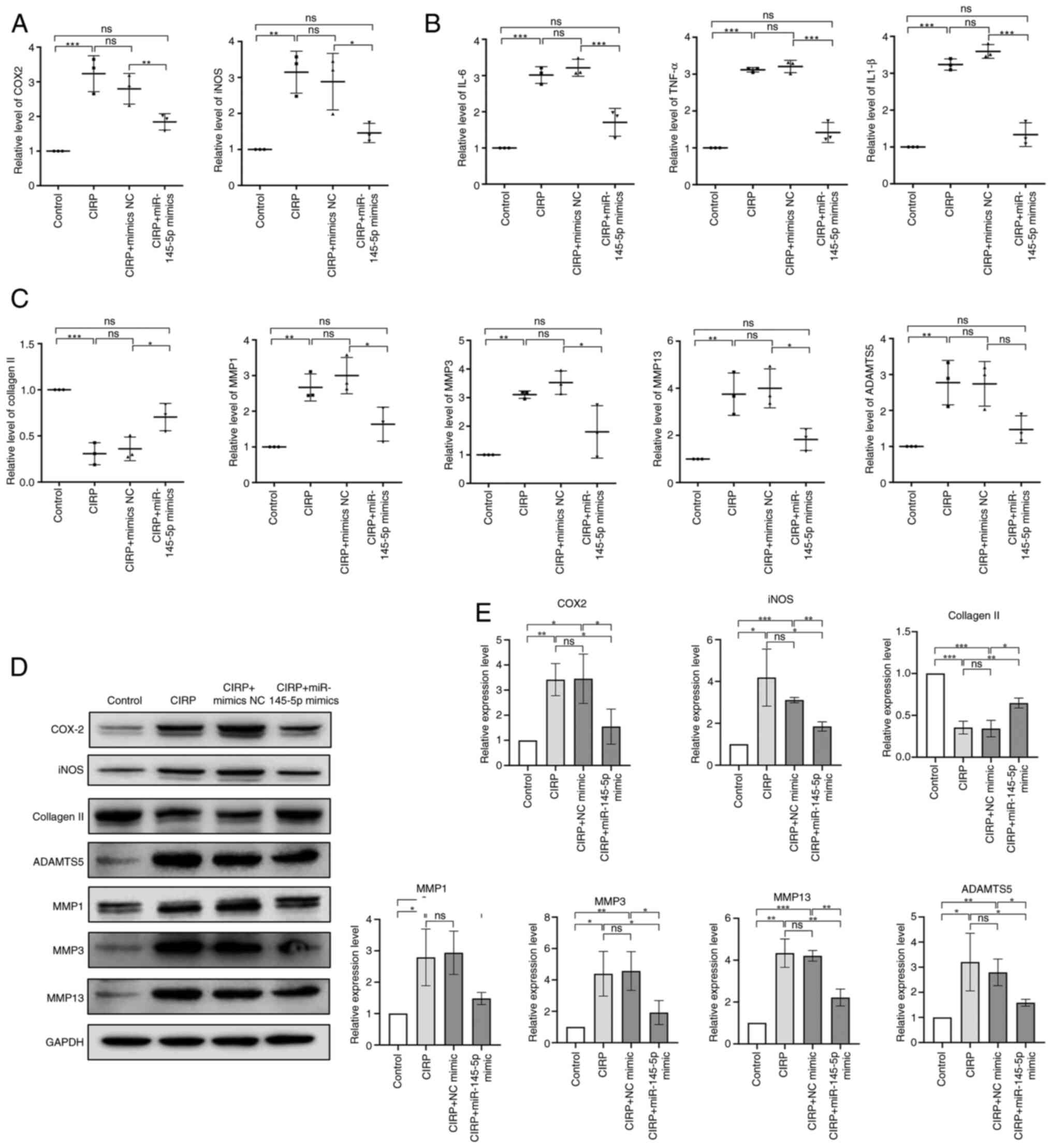

Subsequently, to investigate the effect of

miR-145-5p on human chondrocytes, the cells were transfected with

miR-145-5p mimic, followed by overexpression of CIRP to induce the

inflammation and ECM degradation in chondrocytes. qPCR and western

blotting analysis were conducted to evaluate the mRNA and protein

expression of ECM-related proteins (collagen Ⅱ, ADAMTS5 and MMPs)

as well as pro-inflammatory factors (iNOS, COX-2, IL-6, TNF-α and

IL-1β). As shown in Fig. 7A, B and

E, the expression of pro-inflammatory factors was markedly

increased after CIRP overexpression but was reduced by miR-145-5p

mimic treatment. In Fig. 7C-E,

the expression of collagen Ⅱ was markedly decreased following CIRP

overexpression but was increased by miR-145-5p mimic treatment,

with the expression of other ECM-related proteins showing inverse

results. These findings indicated that miR-145-5p overexpression

markedly increased collagen Ⅱ expression, decreased the expression

of MMP1, MMP3, MMP13 and ADAMTS5 and reduced inflammatory response

in human chondrocytes. Moreover, the damage induced by CIRP

overexpression in human chondrocytes was alleviated by

overexpressed miR-145-5p overexpression. These results indicate

that miR-145-5p plays a key role in maintaining the function of

chondrocytes in vitro.

| Figure 7miR-145-5p elevation suppresses CIRP

induced damage of chondrocytes. (A and B) Chondrocytes were

transfected with miR-145-5p mimics or CIRP, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α,

iNOS and COX-2 expression were analyzed by qPCR. (C) Chondrocytes

were transfected with miR-145-5p mimics or CIRP, the mRNA

expression of extracellular matrix proteins of chondrocytes were

analyzed by qPCR. (D and E) Chondrocytes were transfected with

miR-145-5p mimics or CIRP, the protein expression of iNOS, COX-2

and extracellular matrix proteins of chondrocytes were analyzed by

western blotting. n=3, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. miR, microRNA;

CIRP, cold-inducible RNA-binding protein; iNOS, inducible nitric

oxide synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; qPCR, quantitative

PCR. |

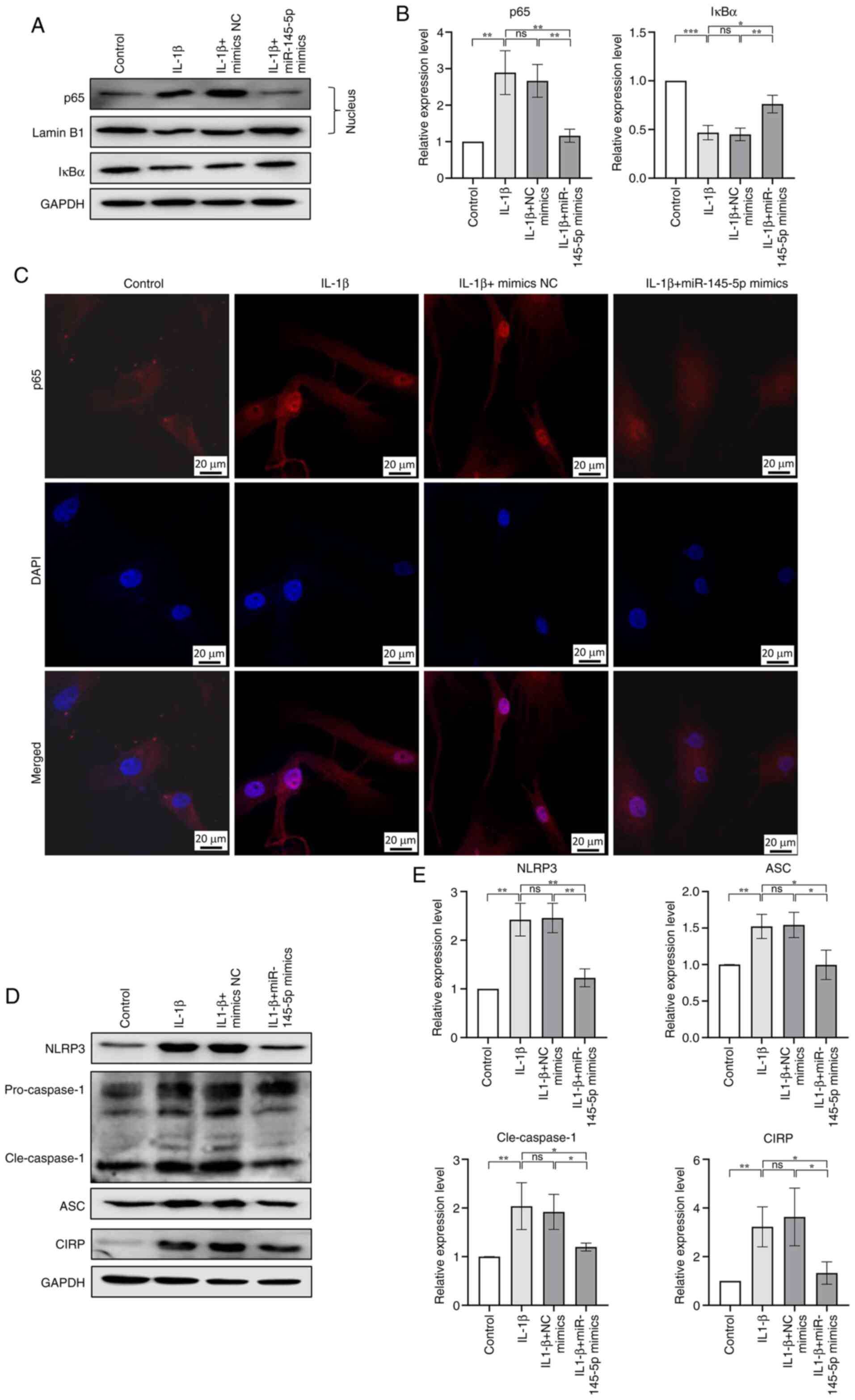

miR-145-5p suppresses IL-1β-induced

CIRP/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway activation

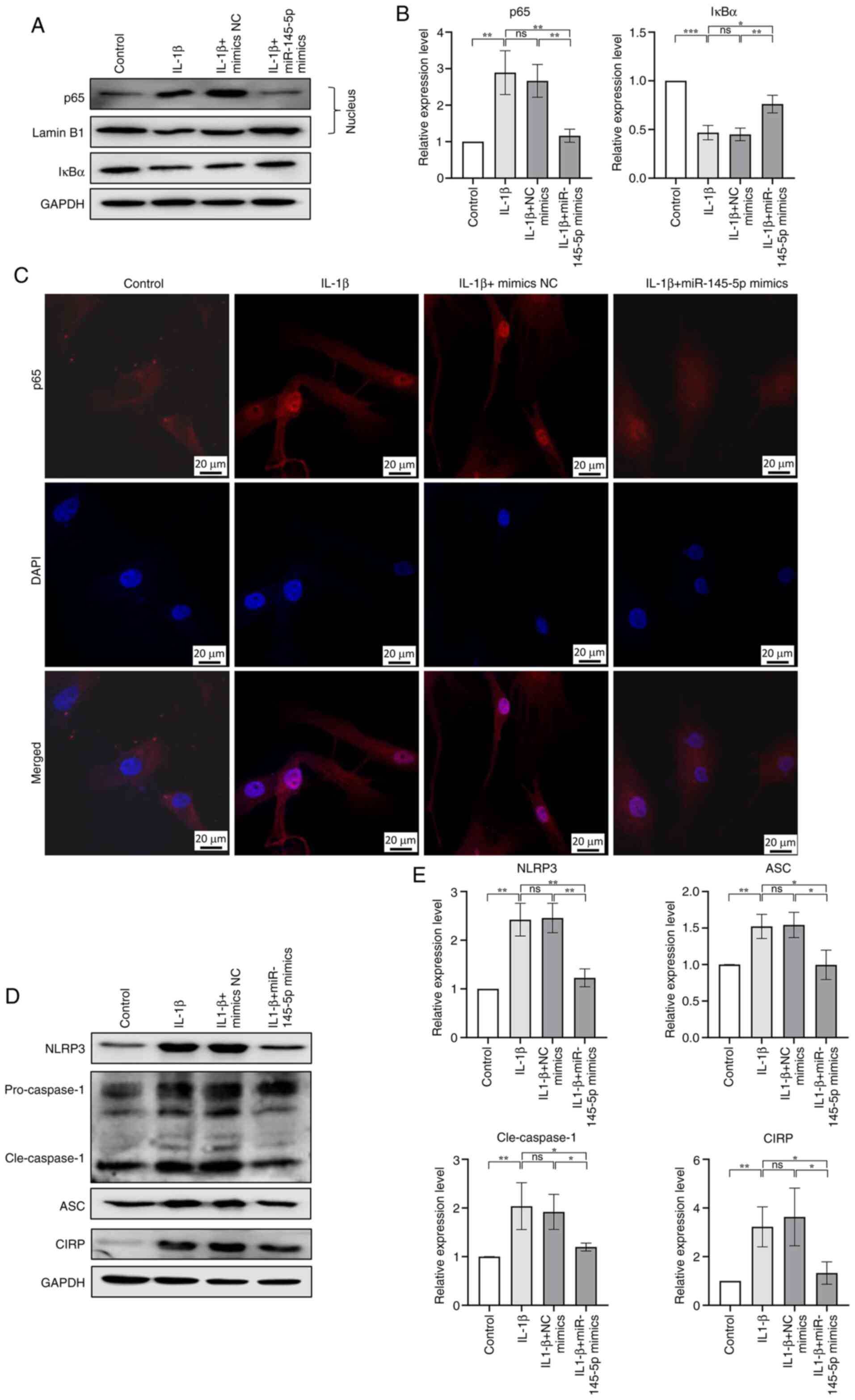

The present study investigated the role of

miR-145-5p in IL-1β-induced activation of the CIRP/NF-kB/NLRP3

signaling pathway. It was found that treatment with 10 ng/ml IL-1β

increased the expression of p65 in the nucleus and promoted the

degradation of IκBα in human chondrocytes (Fig. 8A and B). Additionally, IL-1β

induced the nuclear translocation of p65 (Fig. 8C). However, the activation of the

NF-κB signaling pathway was suppressed by treatment with miR-145-5p

mimics (Fig. 8A-C). Moreover,

IL-1β-induced expression of CIRP and activated the downstream NLRP3

inflammasome signaling pathway, both of which were suppressed by

treatment with miR-145-5p mimics (Fig. 8D and E). These results indicated

that miR-145-5p exerts a protective function in chondrocytes by

inhibiting the CIRP/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway.

| Figure 8miR-145-5p elevation suppressed CIRP

induced NF-κB/NLRP3 activation. (A and B) Chondrocytes were

transfected with miR-145-5p mimics or IL-1β treatment, western

blotting results showed the protein expression of IκBα in the

cytoplasm and p65 in the nucleus of chondrocytes. (C) The nuclei

translocation of p65 was detected by the immunofluorescence

combined with DAPI staining for the nuclei. (D and E) western

blotting results showed the protein expression NLRP3,

cleaved-caspase-1, ASC and CIRP in chondrocytes transfected with

miR-145-5p mimics or IL-1β treatment. n=3, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. miR, microRNA;

CIRP, cold-inducible RNA-binding protein; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin

domain containing 3; Cle, cleaved. |

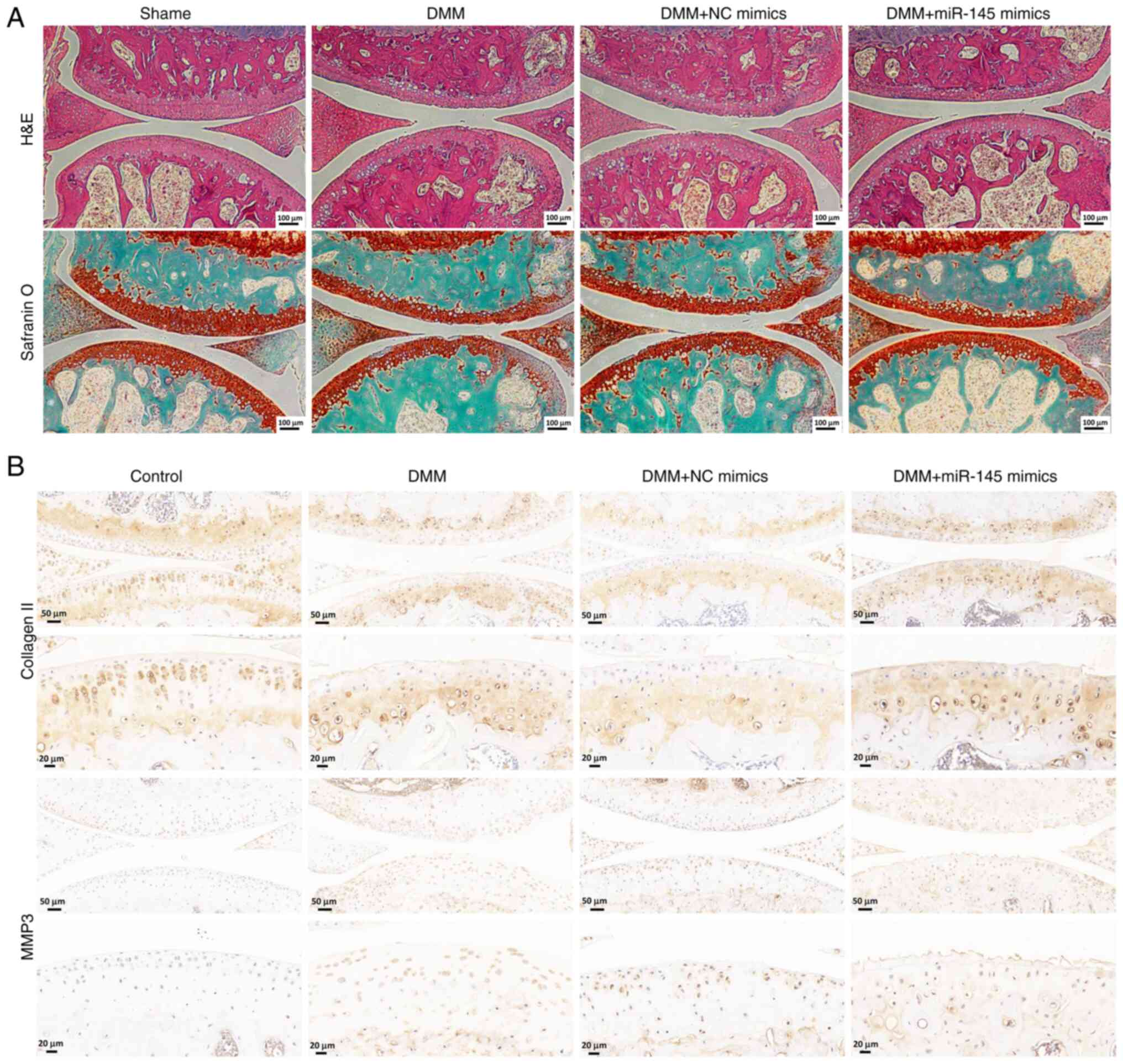

miR-145-5p inhibits articular cartilage

degradation in vivo

Finally, the effect of miR-145-5p on mice with OA

was evaluated in vivo. The mice were divided into four

groups: One sham group and three DMM groups (DMM group, DMM

injected with miR-NC exosomes group and DMM injected with

miR-145-5p mimic exosomes group). hematoxylin and eosin staining

was conducted to observe the pathological changes in the articular

cartilage of the knee joint and S/O staining was used to assess

articular cartilage degeneration. The S/O staining revealed that

the articular cartilage in the sham control group exhibited a

normal, red-dyed area and a smooth surface. By contrast, the

thickness of the articular cartilage was markedly reduced in both

the DMM group and the DMM injected with miR-NC exosomes group

compared with the sham control group. Notably, the DMM injected

with miR-145-5p mimic exosomes group showed a thicker red-dyed area

and a smoother surface of articular cartilage compared with the DMM

injected with miR-NC exosomes group (Fig. 9A), suggesting that miR-145-5p

plays a role in attenuating cartilage matrix degradation.

Additionally, immunohistochemical assays for MMP3 and collagen Ⅱ

were also performed in the OA model. In the DMM group and the DMM

injected with miR-NC exosomes group, the expression of MMP3 was

markedly increased compared with the sham group, while the DMM

injected with miR-145-5p mimic exosomes group exhibited decreased

expression of MMP3 (Fig. 9B).

Similarly, the expression of collagen Ⅱ was markedly reduced in the

DMM group and the DMM injected with miR-NC group compared with the

sham group, while the DMM injected with miR-145-5p mimic exosomes

group exhibited elevated expression levels (Fig. 9B). Therefore, these results

indicate that, as demonstrated by the in vivo experiments,

overexpressing of miR-145-5p can hinder OA-related damage.

Discussion

OA is a chronic, age-associated degenerative joint

disease featured by cartilage degeneration and inflammatory

response, which imposes a significant social and economic burden

(1,46). Currently, pain management and

end-stage joint replacement surgery are the most used strategies

for OA treatment. However, these approaches do not stop or reverse

cartilage degeneration and destruction (3,47). Therefore, research has shifted

its focus toward understanding the pathogenesis of OA and

identifying new strategies to prevent its early onset (4). An increasing number of studies have

highlighted that the diagnostic and therapeutic potential of miRNAs

in treatment of OA (28,48). Additionally, exosomes have

emerged as potential natural vehicles for miRNA delivery in disease

therapy. The current study aimed to investigate the effects of the

novel pro-inflammatory factor CIRP on OA progression through the

activation of the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway.

Furthermore, its key findings provided evidence that exosomes

overexpressing miR-145-5p can attenuate OA damage by repressing

CIRP.

CIRP is an RNA-binding protein known for its

tumor-promoting function and our research group has focused on it

for an extended period (15,49). CIRP has been identified as a

significant pro-inflammatory factor, playing important roles in

various inflammation diseases, including sepsis, neuroinflammation,

colitis-associated cancer and endothelial cell inflammation

(17,18,24,50). Two studies have been reported

that CIRP levels were evaluated in the synovial fluid of patients

with OA and rheumatoid arthritis, indicating a positive correlation

between CIRP and OA (26,27).

However, the specific roles of CIRP in OA progression and the

underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The present study aimed to

investigate the function of CIRP in OA progression. It first

assessed its expression and found that CIRP was markedly

upregulated in OA chondrocytes. Additionally, a previous study has

detected CIRP in the synovial fluid of OA patients and it has been

reported that CIRP can be released by macrophages during sepsis

(51). The present study then

examined the expression of CIRP in the exosomes derived from OA

chondrocytes and discovered that these chondrocytes released higher

levels of CIRP in an exosomal manner. Furthermore, treatment with

IL-1β increased the expression of CIRP in both whole chondrocyte

cells and their exosomes. These findings may help to explain the

elevated levels of CIRP observed in the synovial fluid of OA

patients.

Next, the present study investigated the influence

of CIRP on the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and MMP.

During OA progression, the balance of metabolic process is

disrupted. In response to inflammatory cytokines, such as iNOS,

chondrocytes secret many metalloproteinases that contribute to

extracellular matrix degradation (52,53). The results demonstrated that CIRP

markedly upregulated the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines,

including iNOS and COX-2. Additionally, the expression of matrix

metalloproteinase, such as MMP1, MMP3, MMP13 and ADAMTS5, was

markedly elevated following CIRP treatment. Importantly, CIRP also

decreased the expression of collagen Ⅱ. These findings suggested

that CIRP is positively associated with inflammation and

extracellular matrix degradation in OA and the underlying molecular

mechanisms require further investigation.

Furthermore, the present study treated human

chondrocytes with CIRP and performed RNA-seq to explore the

downstream effects. The RNA-seq analysis revealed that CIRP

treatment induced differential gene expression enriched in pathways

related to TNF-α signaling, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction,

IL-17 signaling, NOD-like receptor signaling and TLR signaling

pathway. These pathways are well-established contributors to OA

progression. For example, elevated circulating TNF-α levels are

associated with severe OA and cartilage loss and small molecules

that targeting TNF-α receptors have demonstrated protective effects

against OA (54,55). Previous studies have shown that

extracellular CIRP can stimulate inflammatory responses by

interacting with its receptors such as TLR4, IL-6R and triggering

receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (24,56,57). The RNA-seq data also suggested

that CIRP affects the TLR signaling pathway. Notably, TLR4 is

overexpressed in human OA chondrocytes (58,59) and is a well-studied upstream

activator of the NF-κB signaling pathway (60), implying that CIRP may activate

NF-κB through TLR4 signaling. To investigate this hypothesis, the

present study assessed the activation of NF-κB and found that CIRP

increased the nuclear translocation of p65, a hallmark of NF-κB

pathway activation. Additionally, CIRP upregulated the expression

of IL-1β, a key pro-inflammatory cytokine. The TLR4/NF-κB axis and

NLRP3/ASC/procaspase-1 inflammasome complex are critical for the

maturation and secretion of IL-1β (61,62). It was further confirmed that CIRP

activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. These findings suggested that

CIRP promotes inflammation and ECM degradation in OA by activating

NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway via TLR4. To validate

this mechanism, two inhibitors, BAY 11-7082 (an NF-κB inhibitor)

and TAK-242 (a TLR4 inhibitor), were used to inhibit the TLR4/NF-κB

signaling pathway. The two inhibitors effectively suppressed

CIRP-induced nuclear translocation of p65. Furthermore, they

inhibited the activation of downstream NLRP3 inflammasome and the

expression of IL-1β. Importantly, treatment with these inhibitors

also reversed CIRP-induced ECM degradation.

miRNAs, a type of conserved endogenous non-coding

RNAs, regulate target mRNA stability or translation by directly

binding to their targets. Growing evidence demonstrates that a

number of miRNAs exert protective functions in chondrocytes by

directly targeting multiple mRNAs involved in the development of

OA. miR-145 is a well-known non-coding RNA involved in the

pathogenesis of various inflammation-related diseases, such as

colitis and inflammation-associated colon cancer (63), rheumatoid arthritis (64) and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

injury (65). The current study

found that the expression of miR-145 was decreased in the cartilage

of OA patients and in chondrocytes treated with IL-1β, highlighting

its possible role in the pathogenesis of OA. More importantly, CIRP

was identified as a target of miR-145-5p in chondrocytes. The

chondrocyte-protective function of miR-145-5p was assessed both

in vivo and in vitro. It was found that miR-145-5p

could suppress the inflammatory response, ECM degradation and

activation of NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway induced by

overexpression of CIRP or IL-1β treatment in vitro. The

results were consistent with a previous study showing that miR-145

plays a protective role in chondrocytes during OA progression

(34). In vivo

experiments further supported the idea that exosomal delivery of

miR-145 could suppress OA progression. The present study found that

miR-145 suppresses the expression of CIRP in OA, suggesting that

miR-145 may play an important role in modulating the inflammatory

response and pathological progression of OA. While miR-145 is a

significant microRNA that suppresses CIRP expression, it is not the

only one identified in the literature. Previous study has reported

that miR-383-5p can target CIRP mRNA and inhibit its expression in

ovarian granulosa cells (66).

Additionally, Lin et al (67) recently demonstrated that CIRP is

a direct target of miR-377-3p in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Aside

from these two miRNAs, no other microRNAs have been documented to

inhibit CIRP expression in the literature. Analysis using databases

such as miRWalk, TargetScan, StarBase, miRDIP and

chondrogenesis-related microRNA resources revealed six candidate

microRNAs that may also regulate CIRP expression. Further

investigation demonstrated specific binding sites between CIRP mRNA

and miR-145-5p, with decreased expression of miR-145-5p observed in

OA chondrocytes. Consequently, the present study focused on miR-145

for more detailed study. The dual luciferase reporter gene assay

confirmed that miR-145-5p suppresses CIRP expression in OA

chondrocytes. Further research is needed to explore the potential

existence of other microRNAs that may regulate CIRP expression in

the context of OA.

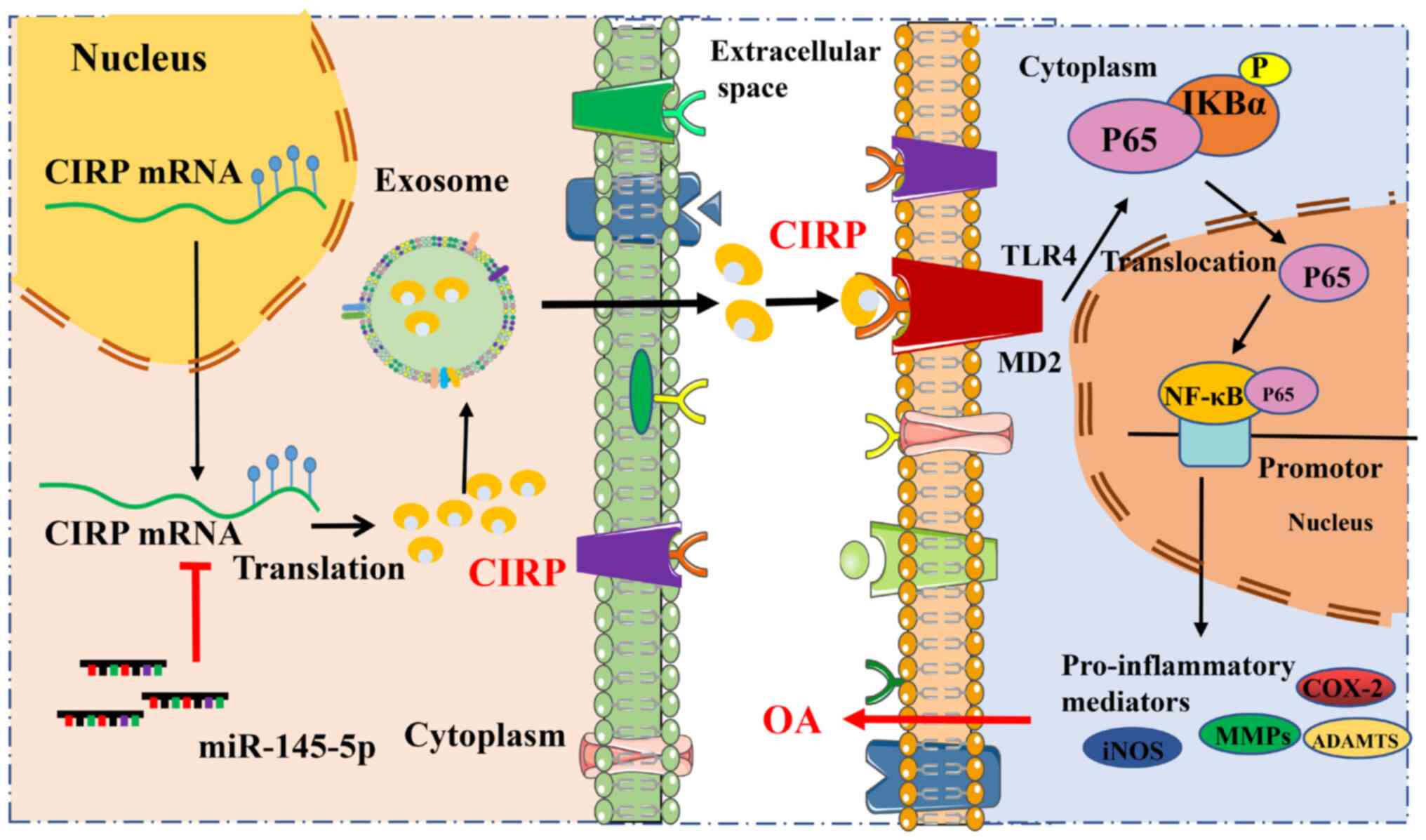

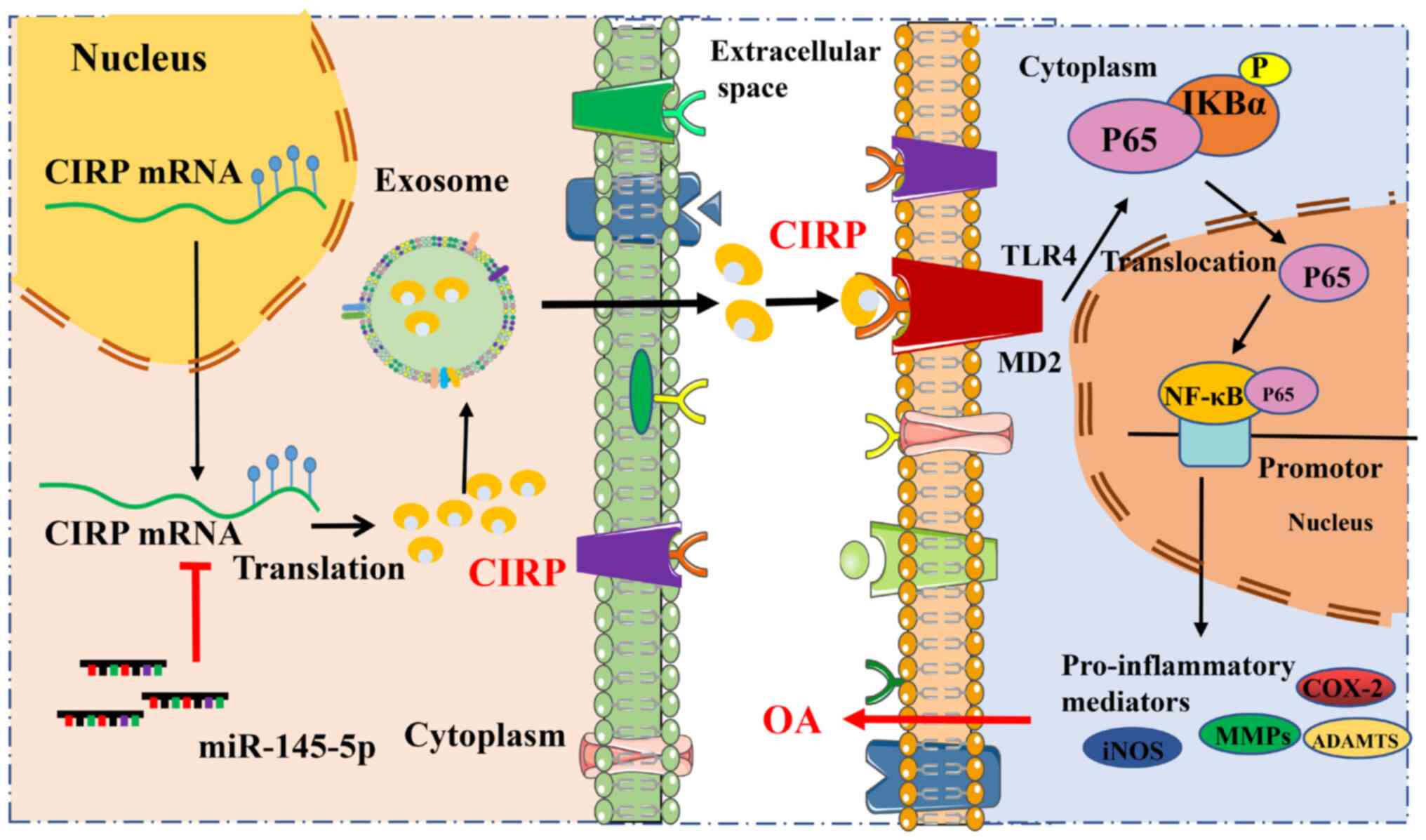

In conclusion, the present study confirmed that CIRP

can be secreted in the form of exosomes, functions as a

pro-inflammatory factor and activates the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3

signaling pathway, thereby promoting the inflammatory response, ECM

degradation and the progression of OA (Fig. 10). It also established that CIRP

is a target of miR-145-5p, which inhibits CIRP expression in OA.

In vitro, miR-145-5p was shown to suppress the inflammatory

response, ECM degradation and the activation of the NF-κB/NLRP3

signaling pathway induced by either CIRP overexpression or IL-1β

treatment. Furthermore, in vivo delivery of miR-145-5p via

exosomes was effective in inhibiting OA progression, highlighting

the potential of exosome-based miR-145-5p delivery as a therapeutic

strategy. Overall, the findings suggested a novel strategy for OA

treatment by targeting pro-inflammatory factors such as CIRP, with

miR-145-5p acting as a key regulator of CIRP expression. However,

the clinical relevance of CIRP in alleviating OA is still in its

early stages. While there is promising potential for targeting CIRP

in OA treatment, this area remains an emerging field of research.

The therapeutic implications of CIRP inhibition warrant further

exploration through clinical trials to determine whether CIRP

suppression can indeed provide significant relief or disease

modification in OA patients. It is important to note the

limitations of the present study. It would be an oversimplification

to assert that suppressing CIRP expression will directly lead to

the suppression of OA. Although CIRP has been implicated in the

inflammatory response and cartilage degradation associated with OA,

the relationship between CIRP and OA is probably complex and

multifactorial. Therefore, while targeting CIRP may present

therapeutic potential, it is unlikely to be a sufficient strategy

for fully mitigating OA. A comprehensive understanding of

additional factors and pathways is essential when considering CIRP

as a therapeutic target for OA. Future investigations should focus

on identifying the underlying mechanisms at play in this

relationship to improve the informing of therapeutic

strategies.

| Figure 10Schematic illustration of targeting

of CIRP attenuates osteoarthritis progression and the underlying

mechanism. CIRP can be secreted in the form of exosomes and acts as

a pro-inflammatory factor that activates the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3

signaling pathway, promoting the inflammatory response, ECM

degradation and the progression of OA. Additionally, CIRP is

identified as a target of miR-145, which inhibits its expression in

OA. CIRP, cold-inducible RNA-binding protein; TLR4, Toll-like

receptor 4; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; OA,

osteoarthritis; ECM, extracellular matrix; miR, microRNA; iNOS,

inducible nitric oxide synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; MMPs,

matrix metalloproteinases. |

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WCS was responsible for data curation, formal

analysis, funding acquisition and original draft. YL was

responsible for data curation, formal analysis, the original draft

manuscript and methodology. JGF was responsible for data curation,

formal analysis and validation. JHL was responsible for formal

analysis and validation. QFH was responsible for formal analysis

and investigation. DXH and YXC were responsible for formal analysis

and investigation. HYS and WY were responsible for investigation

and validation. WS was responsible for conceptualization, funding

acquisition, formal analysis and validation. QY was responsible for

conceptualization, funding acquisition, formal analysis and

original draft. WCS and QY confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The collection of cartilage tissues from patients

was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Second People's

Hospital (approval no. 2023-157-01YJ). Samples used in this study

were collected after all patients received detailed explanation of

the research and submitted written informed consents. All in

vivo experiments procedures were approved by the Animal

Research Committee of Southwest Medical University (approval no.

20220307-004).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

OA

|

osteoarthritis

|

|

MMPs

|

matrix metalloproteinases

|

|

AGEs

|

advanced glycation end products

|

|

CIRP

|

cold-inducible RNA-binding

protein

|

|

DAMP

|

damage-associated molecular pattern

molecule

|

|

TLR4

|

Toll-like receptor 4

|

|

NLRP3

|

NLR family pyrin domain containing

3

|

|

ECM

|

extracellular matrix

|

|

COX-2

|

cyclooxygenase-2

|

|

iNOS

|

inducible nitric oxide synthase

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the joint foundation of

Luzhou Government and Southwest Medical University (grant no.

2024LZXNYDJ104); the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (grant no.

A2403030); Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

82172831); Shenzhen Science and Technology Projects (grant no.

JSGG20220831110400001, KCXFZ20230731093059012) and Shenzhen

High-level Hospital Construction Fund (grant no. 1801024).

References

|

1

|

Martel-Pelletier J, Barr AJ, Cicuttini FM,

Conaghan PG, Cooper C, Goldring MB, Goldring SR, Jones G, Teichtahl

AJ and Pelletier JP: Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

2:160722016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR and

Goldring MB: Osteoarthritis: A disease of the joint as an organ.

Arthritis Rheum. 64:1697–1707. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bijlsma JW, Berenbaum F and Lafeber FP:

Osteoarthritis: An update with relevance for clinical practice.

Lancet. 377:2115–2126. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJ, Agricola R, Price

AJ, Vincent TL, Weinans H and Carr AJ: Osteoarthritis. Lancet.

386:376–387. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yang B, Kang X, Xing Y, Dou C, Kang F, Li

J, Quan Y and Dong S: Effect of microRNA-145 on IL-1beta-induced

cartilage degradation in human chondrocytes. FEBS Lett.

588:2344–2352. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tu C, Huang X, Xiao Y, Song M, Ma Y, Yan

J, You H and Wu H: Schisandrin A inhibits the IL-1β-Induced

inflammation and cartilage degradation via suppression of MAPK and

NF-κB signal pathways in rat chondrocytes. Front Pharmacol.

10:412019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chabane N, Zayed N, Afif H, Mfuna-Endam L,

Benderdour M, Boileau C, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Duval N

and Fahmi H: Histone deacetylase inhibitors suppress

interleukin-1beta-induced nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2

production in human chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

16:1267–1274. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhou S, Liu G, Si Z, Yu L and Hou L:

Glycyrrhizin, an HMGB1 inhibitor, suppresses interleukin-1β-induced

inflammatory responses in chondrocytes from patients with

osteoarthritis. Cartilage. 13(2_Suppl): 947S–955S. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Frommer KW, Schaffler A, Rehart S, Lehr A,

Muller-Ladner U and Neumann E: Free fatty acids: Potential

proinflammatory mediators in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis.

74:303–310. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Xu HC, Wu B, Ma YM, Xu H, Shen ZH and Chen

S: Hederacoside-C protects against AGEs-induced ECM degradation in

mice chondrocytes. Int Immunopharmacol. 84:1065792020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gao F and Zhang S: Loratadine alleviates

advanced glycation end Product-induced activation of NLRP3

inflammasome in human chondrocytes. Drug Des Devel Ther.

14:2899–2908. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liao Y, Tong L, Tang L and Wu S: The role

of cold-inducible RNA binding protein in cell stress response. Int

J Cancer. 141:2164–2173. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhong P and Huang H: Recent progress in

the research of cold-inducible RNA-binding protein. Future Sci OA.

3:FSO2462017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wellmann S, Buhrer C, Moderegger E, Zelmer

A, Kirschner R, Koehne P, Fujita J and Seeger K: Oxygen-regulated

expression of the RNA-binding proteins RBM3 and CIRP by a

HIF-1-independent mechanism. J Cell Sci. 117:1785–1794. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sun W, Liao Y, Yi Q, Wu S, Tang L and Tong

L: The mechanism of CIRP in regulation of STAT3 phosphorylation and

Bag-1/S expression Upon UVB radiation. Photochem Photobiol.

94:1234–1239. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Aziz M, Brenner M and Wang P:

Extracellular CIRP (eCIRP) and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol.

106:133–146. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Qiang X, Yang WL, Wu R, Zhou M, Jacob A,

Dong W, Kuncewitch M, Ji Y, Yang H, Wang H, et al: Cold-inducible

RNA-binding protein (CIRP) triggers inflammatory responses in

hemorrhagic shock and sepsis. Nat Med. 19:1489–1495. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sakurai T, Kashida H, Watanabe T, Hagiwara

S, Mizushima T, Iijima H, Nishida N, Higashitsuji H, Fujita J and

Kudo M: Stress response protein cirp links inflammation and

tumorigenesis in colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Res.

74:6119–6128. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhou M, Yang WL, Ji Y, Qiang X and Wang P:

Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein mediates neuroinflammation in

cerebral ischemia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1840:2253–2261. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Vande Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Jacques

P, Fossoul A, Verheugen E, Vogel P, Beyaert R, Elewaut D,

Kanneganti TD, van Loo G and Lamkanfi M: Negative regulation of the

NLRP3 inflammasome by A20 protects against arthritis. Nature.

512:69–73. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

McAllister MJ, Chemaly M, Eakin AJ, Gibson

DS and McGilligan VE: NLRP3 as a potentially novel biomarker for

the management of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

26:612–619. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen Z, Zhong H, Wei J, Lin S, Zong Z,

Gong F, Huang X, Sun J, Li P, Lin H, et al: Inhibition of Nrf2/HO-1

signaling leads to increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome

in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 21:3002019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu Q, Zhang D, Hu D, Zhou X and Zhou Y:

The role of mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Mol

Immunol. 103:115–124. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhou K, Cui S, Duan W, Zhang J, Huang J,

Wang L, Gong Z and Zhou Y: Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein

contributes to intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury via

TLR4 signaling. Brain Behav. 10:e016182020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Elliott EI and Sutterwala FS: Initiation

and perpetuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and assembly.

Immunol Rev. 265:35–52. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yu L, Li QH, Deng F, Yu ZW, Luo XZ and Sun

JL: Synovial fluid concentrations of cold-inducible RNA-binding

protein are associated with severity in knee osteoarthritis. Clin

Chim Acta. 464:44–49. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yoo IS, Lee SY, Park CK, Lee JC, Kim Y,

Yoo SJ, Shim SC, Choi YS, Lee Y and Kang SW: Serum and synovial

fluid concentrations of cold-inducible RNA-binding protein in

patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 21:148–154.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Felekkis K, Pieri M and Papaneophytou C:

Exploring the feasibility of circulating miRNAs as diagnostic and

prognostic biomarkers in osteoarthritis: Challenges and

opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 24:131442023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lin Z, Jiang T, Zheng W, Zhang J, Li A, Lu

C and Liu W: N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methyltransferase

WTAP-mediated miR-92b-5p accelerates osteoarthritis progression.

Cell Commun Signal. 21:1992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mao G, Zhang Z, Hu S, Zhang Z, Chang Z,

Huang Z, Liao W and Kang Y: Exosomes derived from

miR-92a-3p-overexpressing human mesenchymal stem cells enhance

chondrogenesis and suppress cartilage degradation via targeting

WNT5A. Stem Cell Res Ther. 9:2472018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chen H, Yao H, Chi J, Li C, Liu Y, Yang J,

Yu J, Wang J, Ruan Y, Pi J and Xu JF: Engineered exosomes as drug

and RNA co-delivery system: New hope for enhanced therapeutics?

Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 11:12543562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jiang M, Jike Y, Liu K, Gan F, Zhang K,

Xie M, Zhang J, Chen C, Zou X, Jiang X, et al: Exosome-mediated

miR-144-3p promotes ferroptosis to inhibit osteosarcoma

proliferation, migration, and invasion through regulating ZEB1. Mol

Cancer. 22:1132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang X, Wang J, Liu N, Wu W, Li H, Lu W

and Guo X: Umbilical cord Blood-derived M1 macrophage exosomes

loaded with cisplatin target ovarian cancer in vivo and reverse

cisplatin resistance. Mol Pharm. 20:5440–5453. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hu G, Zhao X, Wang C, Geng Y, Zhao J, Xu

J, Zuo B, Zhao C, Wang C and Zhang X: MicroRNA-145 attenuates

TNF-α-driven cartilage matrix degradation in osteoarthritis via

direct suppression of MKK4. Cell Death Dis. 8:e31402017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhou J, Sun J, Markova DZ, Li S, Kepler

CK, Hong J, Huang Y, Chen W, Xu K, Wei F and Ye W: MicroRNA-145

overexpression attenuates apoptosis and increases matrix synthesis

in nucleus pulposus cells. Life Sci. 221:274–283. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tian K, Deng B, Han X, Zheng H, Lin T,

Wang Z, Zhang Y and Wang G: Over-expression of microRNA-145

elevating autophagy activities via downregulating FRS2 expression.

Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 27:127–135. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Wang X, Lu W, Xia X, Zhu Y, Ge C, Guo X,

Zhang N, Chen H and Xu S: Selenomethionine mitigate PM2.5-induced

cellular senescence in the lung via attenuating inflammatory

response mediated by cGAS/STING/NF-κB pathway. Ecotoxicol Environ

Saf. 247:1142662022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Chen Z, Zhang M, Zhao Y, Xu W, Xiang F, Li

X, Zhang T, Wu R and Kang X: Hydrogen sulfide contributes to

uterine quiescence through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome

activation by suppressing the TLR4/NF-κB signalling pathway. J

Inflamm Res. 14:2753–2768. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

39

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wang S, Li W, Zhang P, Wang Z, Ma X, Liu

C, Vasilev K, Zhang L, Zhou X, Liu L, et al: Mechanical overloading

induces GPX4-regulated chondrocyte ferroptosis in osteoarthritis

via Piezo1 channel facilitated calcium influx. J Adv Res. 41:63–75.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gong T, Wang QD, Loughran PA, Li YH, Scott

MJ, Billiar TR, Liu YT and Fan J: Mechanism of lactic

acidemia-promoted pulmonary endothelial cells death in sepsis: Role

for CIRP-ZBP1-PANoptosis pathway. Mil Med Res. 11:712024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhou M, Aziz M, Yen HT, Ma G, Murao A and

Wang P: Extracellular CIRP dysregulates macrophage bacterial

phagocytosis in sepsis. Cell Mol Immunol. 20:80–93. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhang P, Bai L, Tong Y, Guo S, Lu W, Yuan

Y, Wang W, Jin Y, Gao P, Liu J, et al: CIRP attenuates acute kidney

injury after hypothermic cardiovascular surgery by inhibiting

PHD3/HIF-1α-mediated ROS-TGF-β1/p38 MAPK activation and

mitochondrial apoptotic pathways. Mol Med. 29:612023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Ye L, Tang X, Liu F, Wei T, Xu T, Jiang Z,

Xu L, Xiang C, Yuan X, Shen L, et al: Targeting CIRP and

IL-6R-mediated microglial inflammation to improve outcomes in

intracerebral hemorrhage. J Adv Res. Sep 9–2025. View Article : Google Scholar : Epub ahead of

print.

|

|

45

|

Han J, Zhang Y, Ge P, Dakal TC, Wen H,

Tang S, Luo Y, Yang Q, Hua B, Zhang G, et al: Exosome-derived CIRP:

An amplifier of inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol.

14:10667212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Palazzo C, Nguyen C, Lefevre-Colau MM,

Rannou F and Poiraudeau S: Risk factors and burden of

osteoarthritis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 59:134–138. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ,

Arden NK, Judge A and Beard DJ: Knee replacement. Lancet.

379:1331–1340. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Liu J, Wu X, Lu J, Huang G, Dang L, Zhang

H, Zhong C, Zhang Z, Li D, Li F, et al: Exosomal transfer of

osteoclast-derived miRNAs to chondrocytes contributes to

osteoarthritis progression. Nat Aging. 1:368–384. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Sun W, Bergmeier AP, Liao Y, Wu S and Tong

L: CIRP sensitizes cancer cell responses to ionizing radiation.

Radiat Res. 195:93–100. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang F, Yang WL, Brenner M and Wang P:

Attenuation of hemorrhage-associated lung injury by adjuvant

treatment with C23, an oligopeptide derived from Cold-inducible

RNA-binding protein. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 83:690–697. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Murao A, Tan C, Jha A, Wang P and Aziz M:

Exosome-mediated eCIRP release from macrophages to induce

inflammation in sepsis. Front Pharmacol. 12:7916482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ying X, Peng L, Chen H, Shen Y, Yu K and

Cheng S: Cordycepin prevented IL-β-induced expression of

inflammatory mediators in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Int

Orthop. 38:1519–1526. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Schmidt N, Pautz A, Art J, Rauschkolb P,

Jung M, Erkel G, Goldring MB and Kleinert H: Transcriptional and

post-transcriptional regulation of iNOS expression in human

chondrocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 79:722–732. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Stannus O, Jones G, Cicuttini F,

Parameswaran V, Quinn S, Burgess J and Ding C: Circulating levels

of IL-6 and TNF-α are associated with knee radiographic

osteoarthritis and knee cartilage loss in older adults.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 18:1441–1447. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhao Y, Li Y, Qu R, Chen X, Wang W, Qiu C,

Liu B, Pan X, Liu L, Vasilev K, et al: Cortistatin binds to TNF-α

receptors and protects against osteoarthritis. EBioMedicine.

41:556–570. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhou M, Aziz M, Denning NL, Yen HT, Ma G

and Wang P: Extracellular CIRP induces macrophage endotoxin

tolerance through IL-6R-mediated STAT3 activation. JCI Insight.

5:e1337152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Denning NL, Aziz M, Murao A, Gurien SD,

Ochani M, Prince JM and Wang P: Extracellular CIRP as an endogenous

TREM-1 ligand to fuel inflammation in sepsis. JCI Insight.

5:e1341722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Gomez R, Villalvilla A, Largo R, Gualillo

O and Herrero-Beaumont G: TLR4 signalling in osteoarthritis-finding

targets for candidate DMOADs. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 11:159–170. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Barreto G, Senturk B, Colombo L, Brück O,

Neidenbach P, Salzmann G, Zenobi-Wong M and Rottmar M: Lumican is

upregulated in osteoarthritis and contributes to TLR4-induced

pro-inflammatory activation of cartilage degradation and macrophage

polarization. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 28:92–101. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Liu L, Gu H, Liu H, Jiao Y, Li K, Zhao Y,

An L and Yang J: Protective effect of resveratrol against

IL-1β-induced inflammatory response on human osteoarthritic

chondrocytes partly via the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway: An

'in vitro study'. Int J Mol Sci. 15:6925–6940. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang A, Wang P, Ma X, Yin X, Li J, Wang

H, Jiang W, Jia Q and Ni L: Mechanisms that lead to the regulation

of NLRP3 inflammasome expression and activation in human dental

pulp fibroblasts. Mol Immunol. 66:253–262. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang C, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Chen C, Chi Q, Xu

K and Yang L: Ursolic acid protects chondrocytes, exhibits

anti-inflammatory properties via regulation of the NF-κB/NLRP3

inflammasome pathway and ameliorates osteoarthritis. Biomed

Pharmacother. 130:1105682020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Dougherty U, Mustafi R, Zhu H, Zhu X, Deb

D, Meredith SC, Ayaloglu-Butun F, Fletcher M, Sanchez A, Pekow J,

et al: Upregulation of polycistronic microRNA-143 and microRNA-145

in colonocytes suppresses colitis and Inflammation-associated colon

cancer. Epigenetics. 16:1317–1334. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Tang J, Yi S and Liu Y: Long non-coding

RNA PVT1 can regulate the proliferation and inflammatory responses

of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes by targeting

microRNA-145-5p. Hum Cell. 33:1081–1090. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Liu Z, Tao B, Fan S, Pu Y, Xia H and Xu L:

MicroRNA-145 protects against myocardial ischemia reperfusion

injury via CaMKII-Mediated antiapoptotic and Anti-inflammatory

pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019:89486572019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Li Y, Wu X, Miao S and Cao Q: MiR-383-5p