Introduction

Prostate cancer remains the second leading cause of

cancer death for men in the United States. According to the

National Cancer Institute, it is estimated that there will be

238,590 new cases and 29,720 deaths from prostate cancer in 2013

(http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/prostate).

Initially, prostate cancer cells depend upon androgen stimulation

for growth and proliferation, and sensitivity to hormone (androgen

deprivation) therapy, which effectively blocks the

androgen-mediated signaling pathway. Unfortunately most recurrent

tumors return within two years with castration-resistant growth and

a more aggressive, metastatic phenotype. As of yet, there is no

effective treatment for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC)

(1,2).

Recently, several mechanisms have been proposed for

the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer (3,4)

including mutation, amplification (4,5),

expression alternative-splice variants of the androgen receptor

(6), or the increase of natural

testosterone biosynthesis by cancer cells. These mechanisms suggest

that most CRPC cells may depend on androgen receptor function, but

are adaptive to low hormone levels. However, clinical evidence and

basic research studies support the hypothesis that there are

alternative signaling pathways in AR-negative prostate cancer cells

or cancer-stem cells (7–10).

The hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF)

and its receptor c-Met kinase are key components of the c-Met

signaling pathway, which plays a critical role in the regulation of

cell growth, cell motility, morphogenesis and angiogenesis during

normal development and tissue regeneration (11,12).

However, the overexpression of HGF/SF and c-Met are often detected

in multiple types of human cancers and associated with poor

prognosis for cancer patients (13). In fact, the c-Met signaling pathway

has been confirmed to be involved in survival, growth,

proliferation, migration, angiogenesis and metastasis of cancer

cells during cancer progression (14,15).

Our previous studies revealed the concomitant

down-regulation of both AR and prostate specific membrane antigen

(PSMA) expression during long-term androgen-deprivation in an

established in vitro model (16). We further explored whether long

androgen-deprived LNCaP cells develop an alternative signaling

pathway for growth and proliferation to replace the loss of AR

signaling pathway. Our data suggest that long-term androgen

deprivation may induce overexpression of c-Met with the

downregulation of both AR and PSMA to progress toward a more

aggressive, androgen-independent prostate cancer disease state.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

The human prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP and PC-3

were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas,

VA, USA). The rabbit polyclonal anti-AR antibody (N-20) was

obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

The goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody-FITC and the rabbit

anti-actin antibody were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis,

MO, USA). The mouse monoclonal anti-PSMA antibody 7E11 was

graciously provided by Cytogen Corporation (Princeton, NJ, USA).

Protein blocking solution was obtained from BioGenex (San Ramon,

CA, USA). Rabbit monoclonal anti-c-Met (C-terminus) antibody was

obtained from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA). Rabbit monoclonal

anti-c-Met (N-terminus) antibody was obtained from Abcam

(Cambridge, MA, USA). Hoechst 33342 were obtained from

Invitrogen-Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cy5.5-CTT-54.2 was

prepared by our lab as described previously (17). Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail

(100X) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL,

USA). All other chemicals and cell-culture reagents were purchased

from Fisher Scientific (Sommerville, NJ, USA) or Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell culture

LNCaP and PC-3 cells were grown in T-75 flasks with

normal growth media [RPMI-1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated

fetal calf serum (FBS), 100 units of penicillin and 100

μg/ml streptomycin] in a humidified incubator at 37°C with

5% CO2. Otherwise, for androgen-deprivation growth,

cells were cultured with conditioned media [RPMI-1640 containing

10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, 100 units of penicillin

and 100 μg/ml streptomycin]. Confluent cells were detached

with a 0.25% trypsin 0.53 mM EDTA solution, harvested, and plated

in 2-well slide chambers at a density of 4×104

cells/well. Cells were grown for three days before conducting the

following experiments.

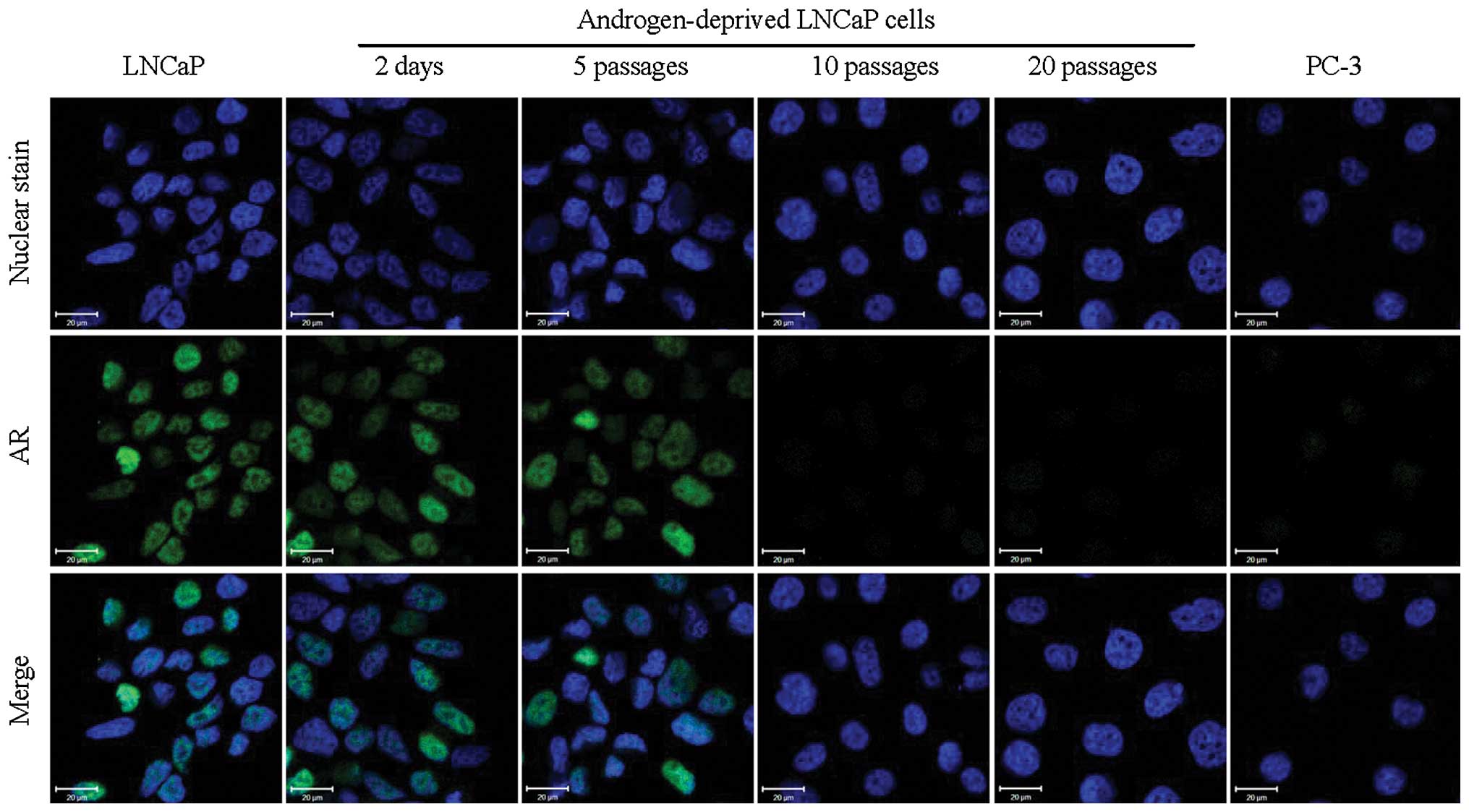

Immunofluorescence detection of AR

The LNCaP cells grown under androgen deprivation

condition over time (5, 10 and 20 passages) were cultured for 3

days on the slides in the conditioned media. For 2-day

androgen-deprivation treatment, LNCaP cells were seeded on slides

with normal growth media for 1-day growth, and replaced with

conditioned media for another 2-day growth. Normal LNCaP cells and

PC-3 cells were used for the AR-positive and AR-negative control,

respectively. These cells were seeded on slides with normal growth

media for 3 days. Slides with cells grown for 3 days in normal

growth media or conditioned media were washed twice in

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in

PBS buffer for 15 min at room temperature, and permeabilized with

0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS buffer for 5 min at room temperature. The

permeabilized cells were blocked in block buffer (0.1% Tween-20, 5%

goat normal serum in PBS buffer) for 2 h at room temperature and

incubated with primary anti-AR antibody (100X diluted in block

buffer) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the cells were incubated

with a secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC, 40X diluted

in 1% BSA, PBS buffer) for 2 h at room temperature, counterstained

with Hoechst 33342, and mounted in Vectashield® Mounting

Medium (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) for confocal

microscopy.

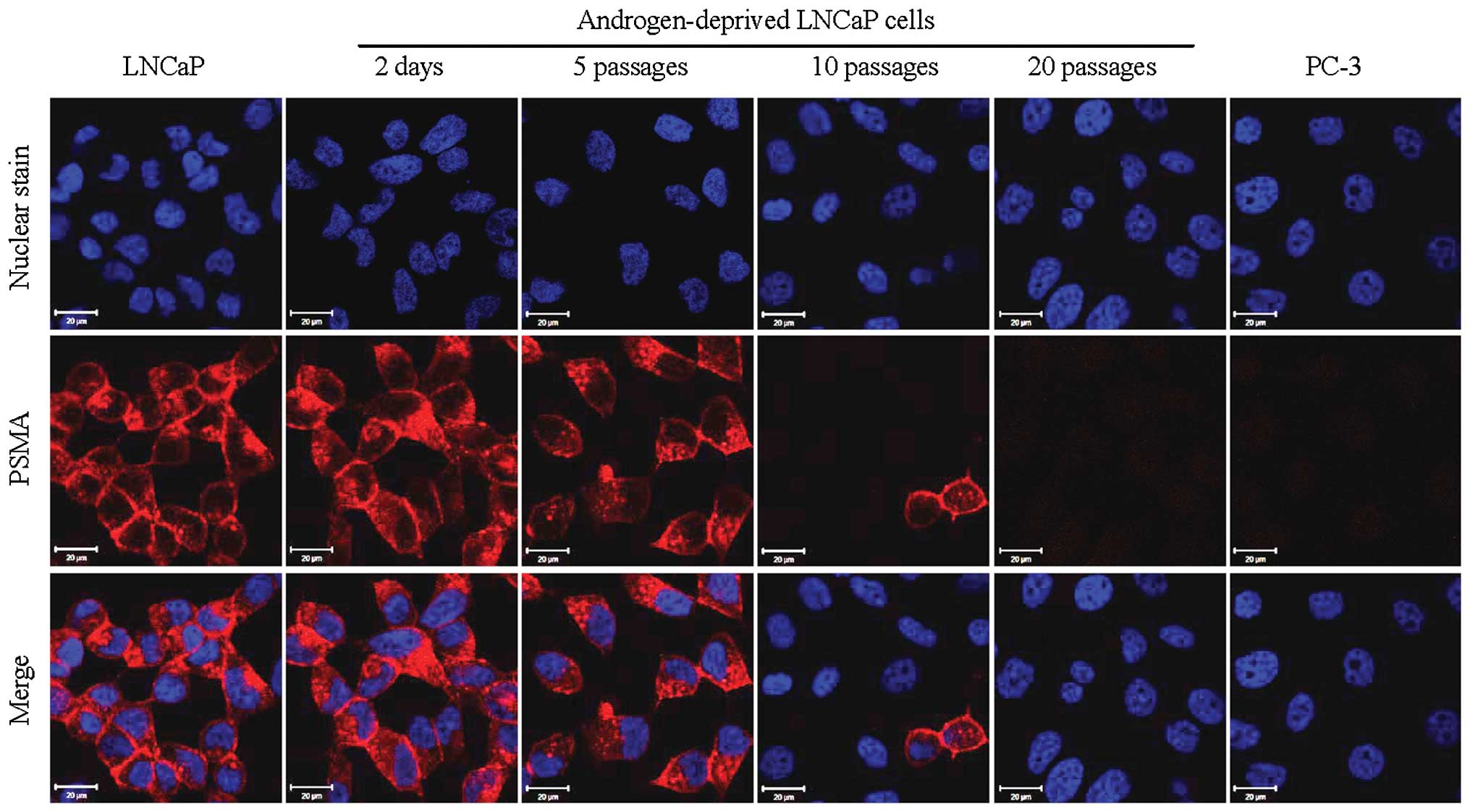

Chemofluorescence detection of PSMA

The cells cultured on the 2-well slides were washed

twice with warm medium (37°C) A (phosphate-free RPMI-1640

containing 1% FBS), then incubated with 1 ml of Cy5.5-CTT-54.2 (10

μM) in warm medium A for 1 h in a humidified incubator at

37°C and 5% CO2. The above treated cells were washed

three times with cold-KRB buffer pH 7.4 (mmol/l: NaCl 154.0, KCl

5.0, CaCl2 2.0, MgCl2 1.0, HEPES 5.0,

D-glucose 5.0) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in KRB for 15 min

at room temperature. The cellular nuclei were counterstained with

Hoechst 33342, and then mounted in Vectashield Mounting medium for

confocal microscopy.

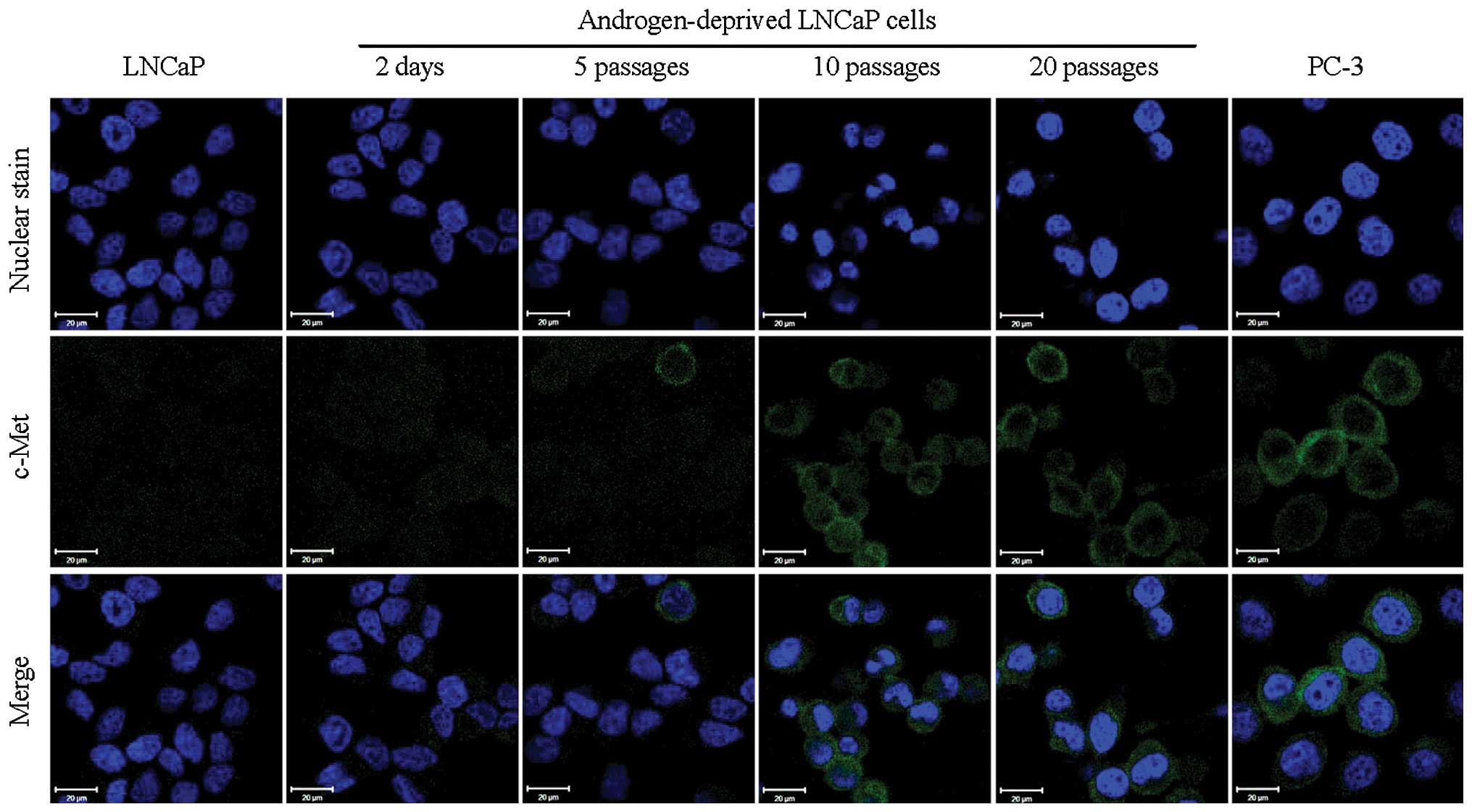

Immunofluorescence detection of

c-Met

The cells cultured on the 2-well slides were washed

twice with PBS buffer and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS

buffer for 15 min at room temperature, and permeabilized with

pre-chilled methanol for 5 min at −20°C. The fixed cells were

blocked in blocking buffer (0.1% Tween-20, 5% goat normal serum in

PBS buffer) for 2 h at room temperature and incubated with primary

rabbit anti-human c-Met antibody (100X diluted in blocking buffer)

overnight at 4°C. After washing, the cells were incubated with a

secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC, 40X diluted in 1%

BSA, PBS buffer) for 2 h at room temperature, counterstained with

Hoechst 33342, and mounted in Vectashield Mounting medium (Vector

Laboratories Inc.) for confocal microscopy.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Cells were visualized under 40X oil immersion

objective using an LSM 510 META Laser Scanning Microscope. Hoechst

33342 was excited with a Diode laser (405 nm), and the emission was

collected with a BP420–480 nm filter. AR immunofluorescence (with

goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC) was excited at 488 nm using an Argon

Laser, and the emission was collected with an LP505 nm filter.

PSMA-targeted imaging with Cy5.5-CTT-54.2 was excited using 633 nm

from a HeNe Laser, and the emission collected with an LP 650 nm

filter. To reduce interchannel crosstalk, a multi-tracking

technique was used, and images were taken at a resolution of

1,024×1,024 pixels. Confocal scanning parameters were set up so

that the control cells without treatment did not display background

fluorescence. The imaging colors of the fluorescent dyes, Hoechst

33342 and FITC, were defined as blue and green, respectively. When

the emission wavelength of the near-infrared fluorescent dye Cy5.5

was beyond visible ranges, fluorescence pseudocolor of Cy5.5 was

assigned as red. The pictures were edited by National Institutes of

Health (NIH) Image J software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) and Adobe Photoshop

CS2.

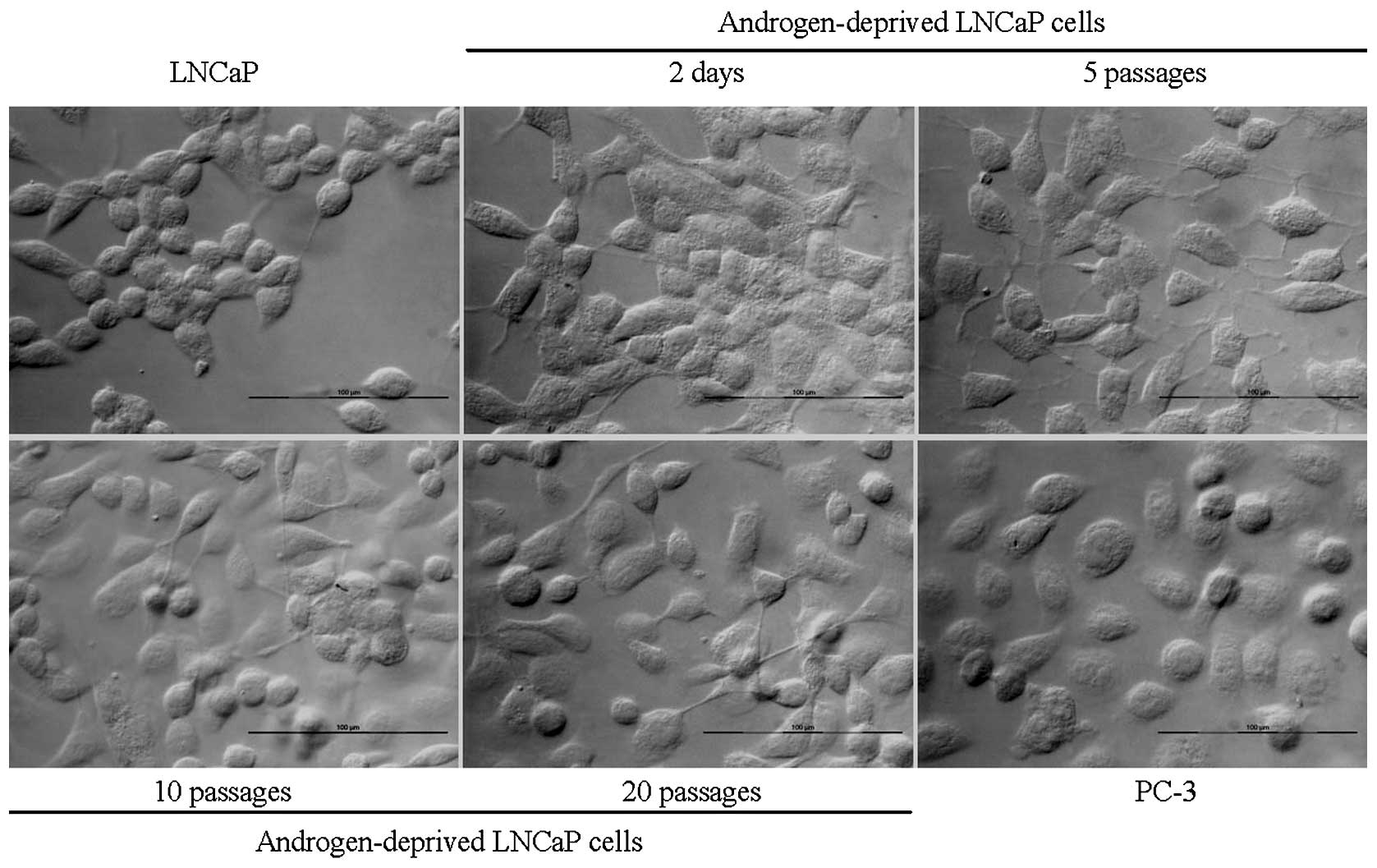

Cell morphology

The change in cell morphology was visualized using a

compound light microscope (Olympus BH-2, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd.,

Tokyo, Japan) at ×20 magnification (objective lens numerical

aperture =1.25). Digital images were obtained using a digital

camera system (Jenoptik ProgRes Camera, C12plus, Jenoptik laser,

Optical Systems GmbH, Jena, Germany) mounted on the microscope.

Whole cell lysate extraction and western

blot analysis

The controls: PC-3 and LNCaP cells (cultured in

normal growth media) and LNCaP cells under androgen deprivation

over time (2 days, 5, 10, or 20 passages) were collected by

scraping, washed once in ice-cold PBS, re-suspended in 3-fold cell

pellet volumes of lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 137 mM

NaCl, 10% glycerol) (18,19) supplemented with 1X Halt Protease

Inhibitor Cocktail for 15 min on ice, then transferred to Eppendorf

tubes for centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, the

supernatant was saved as whole-cell protein extracts. Protein

concentrations were determined using Non-Interfering Protein Assay

(G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO, USA). Western blot analysis was

performed as described previously with only minor modifications

(19,20). In brief, detergent-soluble proteins

(30 μg) were loaded and separated on a NuPAGE™ 4–12%

Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) by electrophoresis for

40 min at a constant 200 V under reducing conditions, and then

transferred to a 0.45 μm PVDF Immobilon-P Transfer Membrane

(Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA) at 400 mA for 100 min in

a transfer apparatus-Owl Bandit VEP-2 (Owl, Portsmouth, NH, USA)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Membranes were

incubated with primary antibody at corresponding dilution overnight

at 4°C and then with horseradish peroxidase conjugated-second

antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The immunoreactive bands were

visualized using Protein Detector TMB Western Blot kit (KPL,

Gaithersburg, MD, USA) following the manufacturer’s

instructions.

Results

An expression-switch from AR to c-Met

induced by androgen deprivation

Cell immunofluorescence imaging clearly demonstrated

that downregulation of AR was observed in androgen-deprived LNCaP

cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig.

1) and after 10 passages, AR was no longer detectable. In

contrast, there were strong signals in the nuclei of normal growth

medium-cultured LNCaP cells. As expected, no signal for AR was

observed in AR-negative PC-3 cells. However, the immunofluorescence

signals for c-Met exhibited a reversed trend of increased

expression with time (Fig. 2) with

considerable expression of c-Met by 10 passages in androgen

deprived growth medium. These results suggest that the switch from

AR to c-Met expression is an adaptable response by the LNCaP cell

line to prolonged androgen deprivation. Although these results were

not consistent with a previous report which demonstrated that the

administration of androgens resulted in increased AR mRNA levels in

LNCaP cells (21), our data are

strongly supported by the analysis of clinical prostate cancer

specimens (22,23).

Loss of PSMA during prolonged androgen

deprivation

Cy5.5-CTT-54.2, a specific PSMA fluorescent

inhibitor (IC50 = 0.55 nM) was prepared and evaluated

for PSMA-targeted fluorescence imaging of LNCaP cells in a previous

investigation from our group (17). In the present study, Cy5.5-CTT-54.2

was employed to detect the change of functional PSMA on the cell

surface of androgen-deprived LNCaP cells by fluorescence imaging.

Consistent with the results for AR immunofluorescence study above,

the considerable cell labeling by Cy5.5-CTT-54.2 observed for LNCaP

cells either cultured in normal growth media or proliferated under

androgen deprivation conditions for up to 5 passages. However, PSMA

expression was significantly reduced by 10 passages in LNCaP cells

(Fig. 3) and by 20 passages PSMA

expression was similar to that of PSMA-negative PC-3 cells.

Changes of cell morphology

The main morphological change of androgen-deprived

LNCaP is the loss of cell to cell tight contact and changed to

scattered growth. The change is clearly correlated with the protein

expression switch from AR to c-Met, which indicated that cells

became more aggressive (Fig.

4).

Western blot analysis

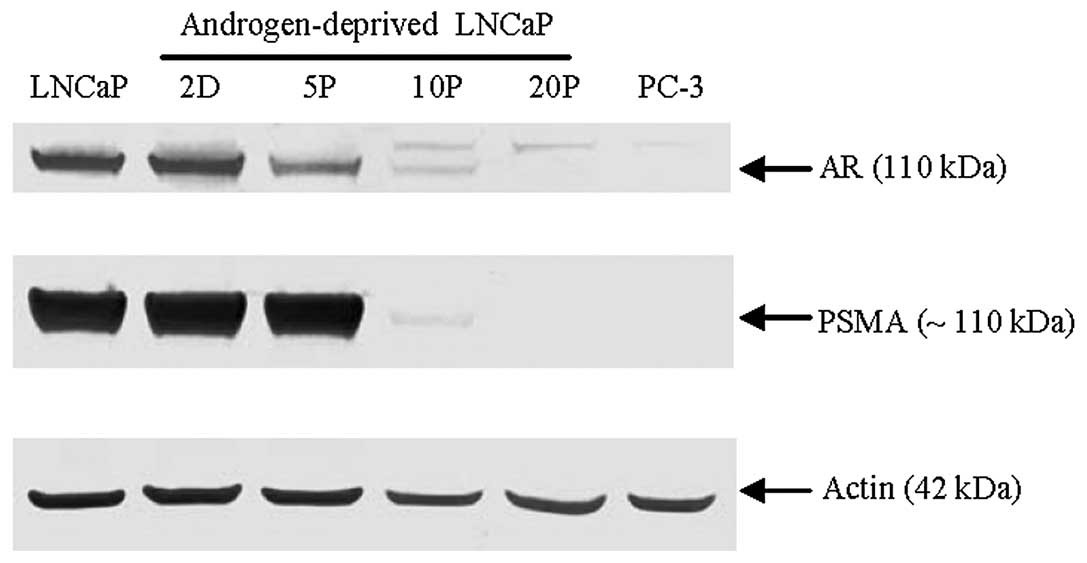

Western blot analysis further confirmed that the

total amount of AR and PSMA expression decreased in LNCaP cells

over the course of androgen deprivation conditions with a dramatic

loss by 10 passages and absence after 20 passages; actin served as

a protein loading control (Fig.

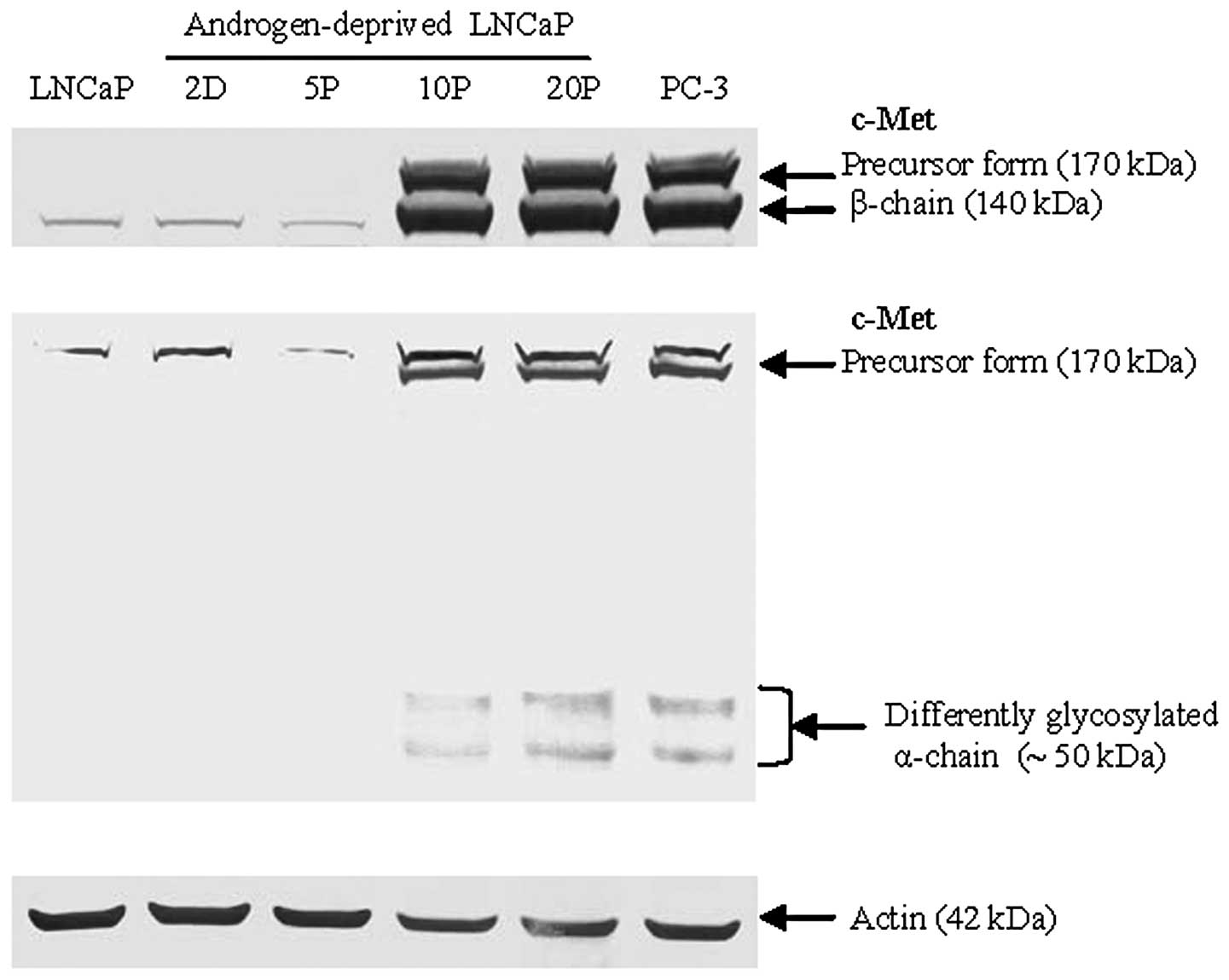

5). In contrast, an inducible upregulation of c-Met expression

was strongly detected by 10 passages of LNCaP cells proliferated

under androgen deprivation conditions using two different epitope

antigen-binding antibodies (Fig.

6). These data suggest that downregulation of AR and the

expression of c-Met in the model LNCaP cell line is dependent on

androgen levels and the duration of androgen deprivation during

cell culture. A cell signaling pathway switch from AR to c-Met in

prostate cancer may originate from the selective pressure of

long-term androgen deprivation.

Discussion

Although CRPC cells may retain active AR and be

sensitive to anti-AR therapies, our data suggest that long-term

androgen-depletion may induce a signaling pathway switch from AR to

c-Met, which may lead to a diagnostically and therapeutically

elusive androgen-independent disease state. However, this switch to

c-Met dependence for proliferation may help to define new

therapeutic strategies tailored specifically against CRPC by

targeting the c-Met signaling pathway through the use of a c-Met

inhibitor, some of which are currently being investigated

clinically (24).

The HGF/c-Met signaling pathway plays a key role in

tumorigenesis and tumor progression. Overexpression of c-Met has

been frequently found in advanced, metastatic, and

castration-resistant prostate cancers (25). An inverse correlation between the

expression of AR and c-Met has been observed in prostate epithelium

and prostate cancer cell lines (9,25),

implying that these receptors may represent the state of the

androgen switch in prostate cancer cells. This is also supported by

findings revealing that AR negatively regulates c-Met expression in

cell models (12). In addition,

high expression of c-Met in prostate cancer may also be correlated

to bone metastasis (26).

In summary, our present data support the concept

that long-term androgen deprivation promotes a signaling pathway

switch from AR to c-Met leading to the development of an aggressive

phenotype of prostate cancer. It is expected that early detection

of this signaling switch may provide critical information in

treatment planning for prostate cancer patients with recurrent,

metastatic and castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Cytogen Corporation

(Princeton, NJ, USA) for the gift of the mouse monoclonal antibody

7E11, and extend their gratitude for technical assistance from C.

Davitt and V. Lynch-Holm at the WSU Franceschi Microscopy and

Imaging Center. This study was supported in part by the National

Institute of Health (R01CA140617).

References

|

1.

|

Gustavsson H, Welen K and Damber JE:

Transition of an androgen-dependent human prostate cancer cell line

into an androgen-independent subline is associated with increased

angiogenesis. Prostate. 62:364–373. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Niu Y, Altuwaijri S, Lai KP, et al:

Androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor and proliferator in

prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 105:12182–12187. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Lee SO, Dutt SS, Nadiminty N, Pinder E,

Liao H and Gao AC: Development of an androgen-deprivation induced

and androgen suppressed human prostate cancer cell line. Prostate.

67:1293–1300. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Saraon P, Jarvi K and Diamandis EP:

Molecular alterations during progression of prostate cancer to

androgen independence. Clin Chem. 57:1366–1375. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Devlin HL and Mudryj M: Progression of

prostate cancer: multiple pathways to androgen independence. Cancer

Lett. 274:177–186. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Watson PA, Chen YF, Balbas MD, et al:

Constitutively active androgen receptor splice variants expressed

in castration-resistant prostate cancer require full-length

androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:16759–16765. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7.

|

Hendriksen PJ, Dits NF, Kokame K, et al:

Evolution of the androgen receptor pathway during progression of

prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 66:5012–5020. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Lorenzo GD, Bianco R, Tortora G and

Ciardiello F: Involvement of growth factor receptors of the

epidermal growth factor receptor family in prostate cancer

development and progression to androgen independence. Clin Prostate

Cancer. 2:50–57. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Maeda A, Nakashiro K, Hara S, et al:

Inactivation of AR activates HGF/c-Met system in human prostatic

carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 347:1158–1165. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Nishida S, Hirohashi Y, Torigoe T, et al:

Prostate cancer stem-like cells/cancer-initiating cells have an

autocrine system of hepatocyte growth factor. Cancer Sci.

104:431–436. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Matsumoto K and Nakamura T: Emerging

multipotent aspects of hepatocyte growth factor. J Biochem.

119:591–600. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Verras M, Lee J, Xue H, Li TH, Wang Y and

Sun Z: The androgen receptor negatively regulates the expression of

c-Met: implications for a novel mechanism of prostate cancer

progression. Cancer Res. 67:967–975. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Christensen JG, Burrows J and Salgia R:

c-Met as a target for human cancer and characterization of

inhibitors for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Lett. 225:1–26.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Gherardi E, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C and

Vande Woude G: Targeting MET in cancer: rationale and progress. Nat

Rev Cancer. 12:89–103. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Peruzzi B and Bottaro DP: Targeting the

c-Met signaling pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 12:3657–3660.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Liu T, Wu LY, Fulton MD, Johnson JM and

Berkman CE: Prolonged androgen deprivation leads to downregulation

of androgen receptor and prostate-specific membrane antigen in

prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 41:2087–2092. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Liu T, Wu LY, Hopkins MR, Choi JK and

Berkman CE: A targeted low molecular weight near-infrared

fluorescent probe for prostate cancer. Bioorg Med Chem Lett.

20:7124–7126. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Matroule JY, Carthy CM, Granville DJ,

Jolois O, Hunt DW and Piette J: Mechanism of colon cancer cell

apoptosis mediated by pyropheophorbide-a methylester

photosensitization. Oncogene. 20:4070–4084. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Liu T, Wu LY and Berkman CE:

Prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted photodynamic therapy

induces rapid cytoskeletal disruption. Cancer Lett. 296:106–112.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Liu T, Toriyabe Y and Berkman CE:

Purification of prostate-specific membrane antigen using

conformational epitope-specific antibody-affinity chromatography.

Protein Expr Purif. 49:251–255. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21.

|

Wolf DA, Herzinger T, Hermeking H,

Blaschke D and Horz W: Transcriptional and posttranscriptional

regulation of human androgen receptor expression by androgen. Mol

Endocrinol. 7:924–936. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Hu P, Chu GC, Zhu G, et al: Multiplexed

quantum dot labeling of activated c-Met signaling in

castration-resistant human prostate cancer. PLoS One. 6:e286702011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Suzuki H, Ueda T, Ichikawa T and Ito H:

Androgen receptor involvement in the progression of prostate

cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 10:209–216. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Smith DC, Smith MR, Sweeney C, et al:

Cabozantinib in patients with advanced prostate cancer: results of

a phase II randomized discontinuation trial. J Clin Oncol.

31:412–419. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25.

|

Humphrey PA, Zhu X, Zarnegar R, et al:

Hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor (c-MET) in prostatic

carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 147:386–396. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Colombel M, Eaton CL, Hamdy F, et al:

Increased expression of putative cancer stem cell markers in

primary prostate cancer is associated with progression of bone

metastases. Prostate. 72:713–720. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|