Introduction

Mesothelioma is a rare malignant tumor and arises in

the pleura of lung, peritoneum and pericardium (1). It is important to study malignant

mesothelioma because most patients with mesothelioma have worked in

careers such as mining. Many environmental factors such as erionite

and asbestos are related to carcinogenesis of mesothelioma

(2). Especially, asbestos can be

easily inhaled or ingested and it is collected in mesothelial

tissue, and thereby asbestos fibers cause cellular damage that

result in tumor growth (3).

Furthermore, asbestos influences epigenetic status of mesothelioma

(4). Despite treatment with

chemotherapy and radiation therapy, it has a poor prognosis.

Acetylation and deacetylation on histones are

controlled by two enzymes, histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and

histone deacetylase (HDAC), respectively. The aberrant histone

acetylation by the imbalance between HAT and HDAC can lead to

carcinogenesis in many cancer cells including colon and

mesothelioma (5,6). Especially, HDAC1 overexpression

promotes invasion and cell proliferation in cancer cells of the

prostate and ovary (7,8). Emerging evidence has demonstrated

that HDAC inhibitors are a potent therapeutic agent for treatment

of mesothelioma (9,10).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have important roles

in gene expression, cell signaling and cell differentiation

(11). However, excessive ROS

production may result in significant damage to cells through

oxidizing DNA, proteins and lipids. For this reason, there are

various antioxidants in the cells. Thioredoxin1 (Trx1), as a small

antioxidant protein increased in mesothelioma (12). It is also demonstrated that

asbestos modulates ROS level and the redox status of Trx and it

finally affects carcinogenesis of mesothelioma (13,14).

Moreover, many studies report that Trx1 is a target molecule for

drug-resistance and therapeutics of cancer (15,16).

Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), a first HDAC

inhibitor for cutaneous T cell lymphoma treatment has an

anti-cancer effect in diverse cancer cells (17,18).

SAHA induced apoptosis via FLICE-like inhibitory protein

(FLIP)/caspase-8 activation in mesothelioma cells (19). However, little is known about the

molecular mechanism of mesothelioma cell death caused by SAHA in

view of the levels of HDAC1, ROS and Trx1. Therefore, in the

present study we investigated the effects of SAHA on cell death in

various mesothelioma cells with regard to HDAC1, ROS and Trx1

levels.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human mesothelial cells (HM69 and HM72) and human

mesothelioma cells (ADA, CON, Hmeso, Mill, Phi, REN and ROB) were

obtained from the University of Hawaii Cancer Center (Honolulu, HI,

USA). These cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 media containing 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-BRL).

Reagents

SAHA purchased from Cayman Chemical Co., (Ann Arbor,

MI, USA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulf-oxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich,

St. Louis, MO, USA). The pan-caspase inhibitor (Z-VAD-FMK),

caspase-3 inhibitor (Z-DEVD-FMK), caspase-8 inhibitor (Z-IETD-FMK)

and caspase-9 inhibitor (Z-LEHD-FMK) were obtained from R&D

Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) and were dissolved in DMSO. NAC and

Vit.C obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical were dissolved in 20 mM

HEPES (pH 7.0) buffer and water, respectively. Based on previous

studies (20,21), cells were pretreated with 15 μM

caspase inhibitors, 2 mM NAC or 0.4 mM Vit.C for 1 h before SAHA

treatment.

Growth inhibition assay

The effect of SAHA on growth inhibition in human

mesothelioma cells was determined by measuring the absorbance of

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT;

Sigma-Aldrich) dye absorbance as previously described (22). Briefly, 5×103 cells were

incubated with the indicated concentrations of SAHA with or without

each caspase inhibitor, HDAC siRNA, NAC, Vit.C or Trx1 siRNA for 24

h.

Western blot analysis

The protein expression levels were evaluated by

western blot analysis. Briefly, 1×106 cells were

incubated with 5 μM SAHA for 24 h. Total protein (30 μg) was

resolved by 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels, and then transferred to

Immobilon-P PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) by

electroblotting. Then membranes were probed with anti-HDAC1,

anti-acetylated H4, anti-PARP, anti-cleaved PARP, anti-cleaved

caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-Trx1,

anti-GAPDH and anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz,

CA, USA). Membranes were incubated with fluorescence-conjugated

secondary antibodies.

Measurement of HDAC activity

The HDAC activity was measured by using a HDAC assay

kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Merck Millipore).

Briefly, 1×106 cells were incubated with 5 μM SAHA for

24 h. Total protein (30 μg) was used to measure the HDAC

activity.

Annexin V-FITC/ PI staining for apoptosis

detection

Apoptosis was detected by staining cells with

AnnexinV-fluoresceinisothiocyanate(FITC;Invitrogen-Life

Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA; Ex/Em=488 nm/519 nm) and propidium

iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich; Ex/Em=488 nm/617 nm) as previously

described (23). Briefly,

1×106 cells were incubated with the indicated

concentrations of SAHA with or without each caspase inhibitor, NAC,

Vit.C, HDAC1 and Trx1 siRNAs for 24 h. Annexin V/PI staining was

analyzed with the Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences,

Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Measurement of lactate dehydrogenase

(LDH) activity

Necrosis in cells was evaluated by an LDH kit

according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma-Aldrich).

Briefly, 1×106 cells were incubated with 5 μM SAHA with

or without each caspase inhibitor, NAC or Vit.C for 24 h. LDH

release was expressed as the percent of extracellular LDH activity

compared with the control cells.

Measurement of MMP (ΔΨm)

MMP (ΔΨm) levels were measured using JC-1 dyes (Enzo

Life Sciences, Plymouth Metting, PA, USA; Ex/Em=515 nm/529 nm).

Briefly, 5×104 cells were incubated with 5 μM SAHA for

24 h. Cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 10 μg/ml

JC-1 at 37°C for 30 min. Then cells were washed three times with

PBS and analyzed with the Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences). Green fluorescence indicates a monomeric state at the

low ΔΨm and red fluorescence presents an aggregate state at the

high ΔΨm.

Sub-G1 analysis

Sub-G1 analysis was determined by PI (Sigma-Aldrich)

staining as previously described (23). Briefly, 1×106 cells were

incubated with 5 μM SAHA with or without each caspase inhibitor,

HDAC1 and Trx1 siRNAs for 24 h. Sub-G1 DNA content cells were

measured and analyzed with Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences).

Transfection of cells with HDAC1 and Trx1

siRNAs

Gene silencing of HDAC1 and Trx1 was performed by

using small interference RNA (siRNA) delivery system. A

non-specific control siRNA duplex [5′-CCUACGCCACCAAUUUCGU

(dTdT)-3′], HDAC1 siRNA duplex [5′-GAGUCAAAACAGA GGAUGA(dTdT)-3′]

and Trx1 siRNA duplex [5′-GCAUGCC AACAUUCCAGUU(dTdT)-3′] were

purchased from the Bioneer Corp. (Daejeon, South Korea). In brief,

2.5×105 cells were incubated in RPMI-1640 supplemented

with 10% FBS. The next day, cells (~30–40% confluence) in each well

were transfected with the control, HDAC1 siRNA or Trx1 siRNA [100

pmol in Opti-MEM (Gibco-BRL)] using Lipofectamine 2000 according to

the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen-Life Technologies). One

day later, cells were treated with or without 5 μM SAHA for

additional 24 h. The transfected cells were collected and used for

western blot analysis, cell growth, sub-G1, Annexin V-FITC and

O2•− level measurements.

Detection of intracellular ROS

levels

Intracellular ROS were detected by a fluorescent

probe dye, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydro-fluorescein diacetate

(H2DCFDA, Ex/Em=495 nm/529 nm; Invitrogen-Molecular

Probes) as previously described (23). Dihydroethidium (DHE, Ex/Em=518

nm/605 nm; Invitrogen-Molecular Probes) is a fluorogenic probe that

is highly selective for O2•− among ROS.

Briefly, 1×106 cells were incubated with 5 μM SAHA with

or without Trx1 siRNA for 24 h. DCF and DHE fluorescence were

detected by using the Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences).

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted by using E.Z.N.A. Total RNA

kit (Omega Bio-Tek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) according to the

manufacturer's instruction. cDNA was obtained from 0.8 μg of total

RNA by using High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Life

Technologies). Real-time PCR was performed using a SYBR-Green

SuperMix (Quanta Bioscience, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in real-time

PCR cycler, LightCyclerR 480 instrument (Roche Diagnostics,

Mannheim, Germany), setting the cycles as follows: 10 min/95°C PCR

initial activation step; 40 cycles of denaturation for 15 sec/95°C

and annealing/extenstion step for 25 sec/58°C. Trx1 (P115235) and

hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT, P160523) were

obtained from the Bioneer Corp. The changes in mRNA level were

determined by the formula 2−ΔΔCT. The relative amount of

mRNA in the sample was normalized to HPRT mRNA.

Statistical analysis

The results represent the mean of at least three

independent experiments (mean ± SD). The data were analyzed using

an Instat software (GraphPad Prism5; GraphPad Software, Inc., San

Diego, CA, USA). The Student's t-test or one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) with post hoc analysis using Tukey's multiple

comparison test was used for parametric data. Statistical

significance was defined as P<0.05.

Results

Effects of SAHA on cell growth and HDAC

activities in human mesothelioma cells

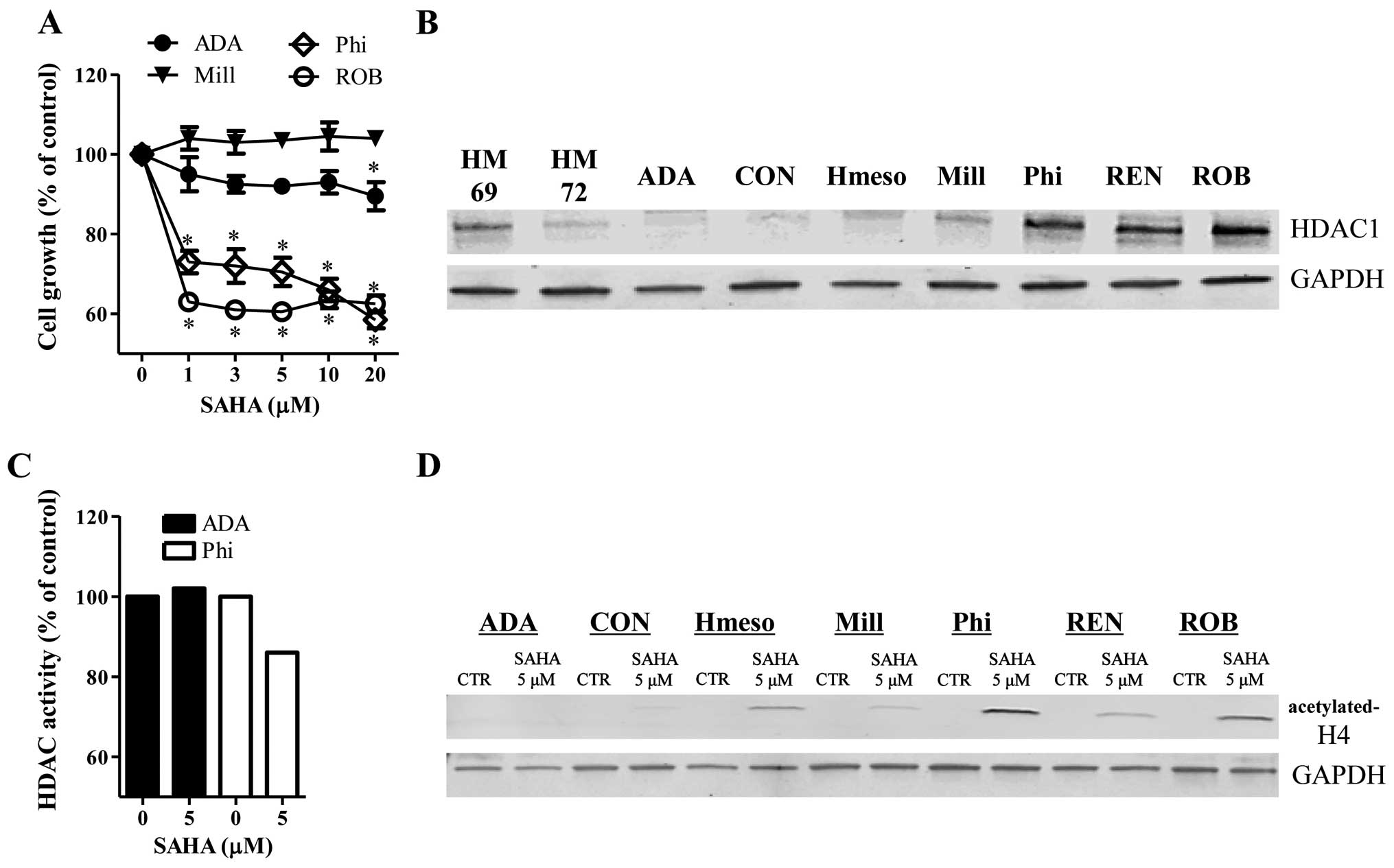

SAHA inhibited the growth of Phi and ROB

mesothelioma cells at 24 h (Fig.

1A). Treatment with 5 μM SAHA reduced the growth of Phi and ROB

cells ~30–40% compared to control cells (Fig. 1A). However, 5 μM SAHA did not

significantly affect the growth of ADA and Mill cells at 24 h

(Fig. 1A). The basal levels of

HDAC1 were increased in Phi, REN and ROB cells, whose cells were

sensitive to SAHA (Fig. 1B). ADA

and Mill cells resistant to SAHA showed lower levels of HDAC1

(Fig. 1B). The HDAC1 levels were

different between the two normal mesothelial cells (Fig. 1B).

After the exposure of mesothelioma cells to SAHA for

24 h, SAHA strongly decreased the activity of HDAC in Phi cells but

this agent did not change the activity of HDAC in ADA cells

(Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the levels

of acetylated-H4 were increased in SAHA-treated Hmeso, Phi, REN and

ROB cells (Fig. 1D). However, SAHA

did not alter the levels of the acetylated-H4 in ADA, CON and Mill

cells (Fig. D).

Effects of SAHA on cell death and

mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP; ΔΨm) in ADA and Phi

cells

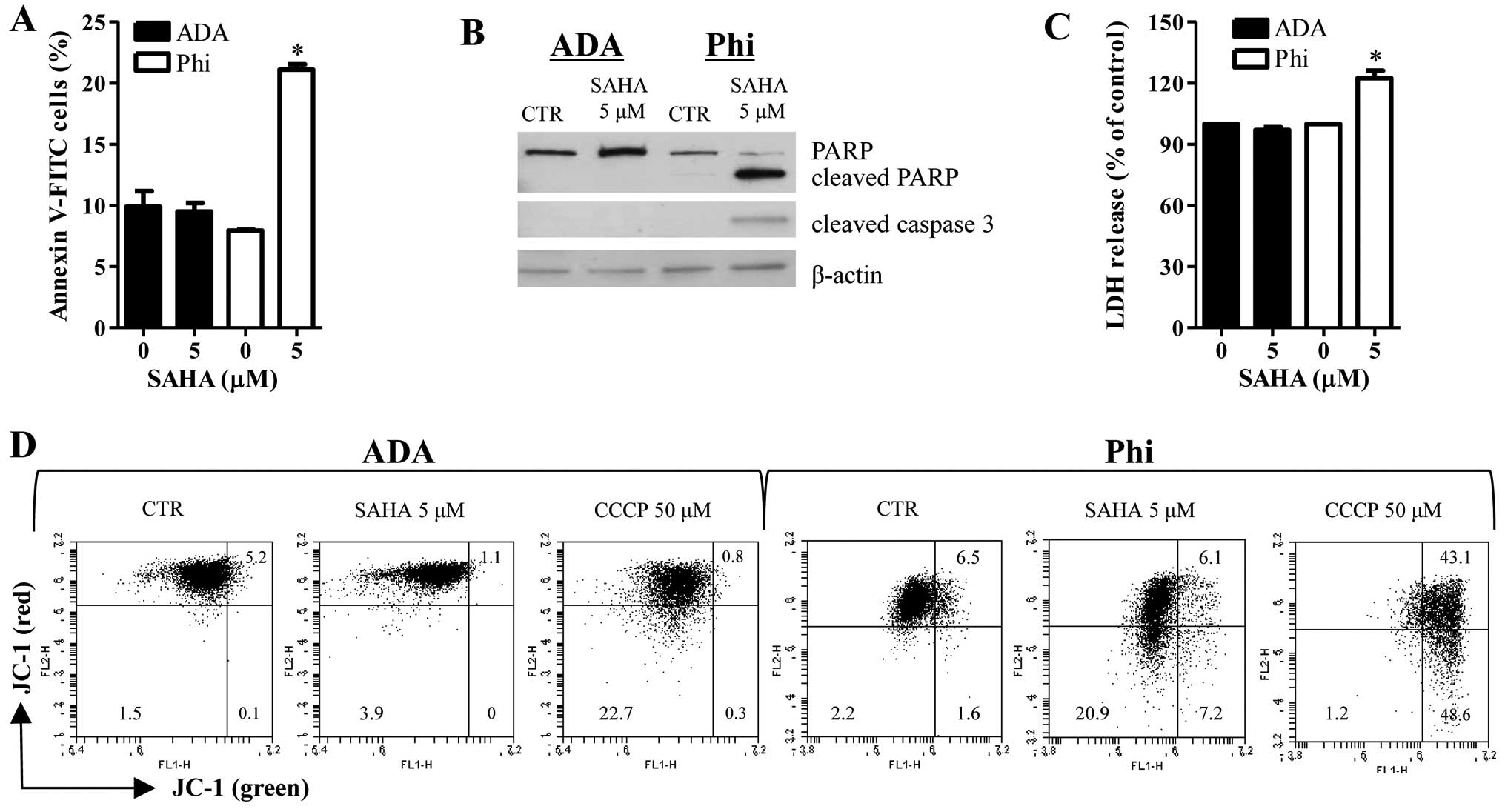

Treatment with 5 μM SAHA increased the numbers of

Annexin V-FITC cells in Phi cells (Fig. 2A). In addition, SAHA induced the

cleavages of PARP and caspase-3 in Phi cells (Fig. 2B). Moreover, this agent

significantly increased LDH release in Phi cells (Fig. 2C). These results implied that

SAHA-induced Phi cell death occurred via apoptosis as well as

necrosis. However, SAHA did not influence the percent of Annexin

V-FITC cells, apoptosis-related protein levels and LDH release in

ADA cells (Fig. 2A–C). The loss of

MMP (ΔΨm) can lead to cell death. As shown in Fig. 2D, red fluorescence of JC-1

indicating the high ΔΨm was decreased in 5 μM SAHA-treated Phi

cells whereas green fluorescence of JC-1 indicating the low ΔΨm was

increased in these cells (Fig.

2D). SAHA affected neither red fluorescence nor green

fluorescence of JC-1 in ADA cells (Fig. 2D). Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl

hydrazine (CCCP) was used as a positive control to induce the loss

of ΔΨm.

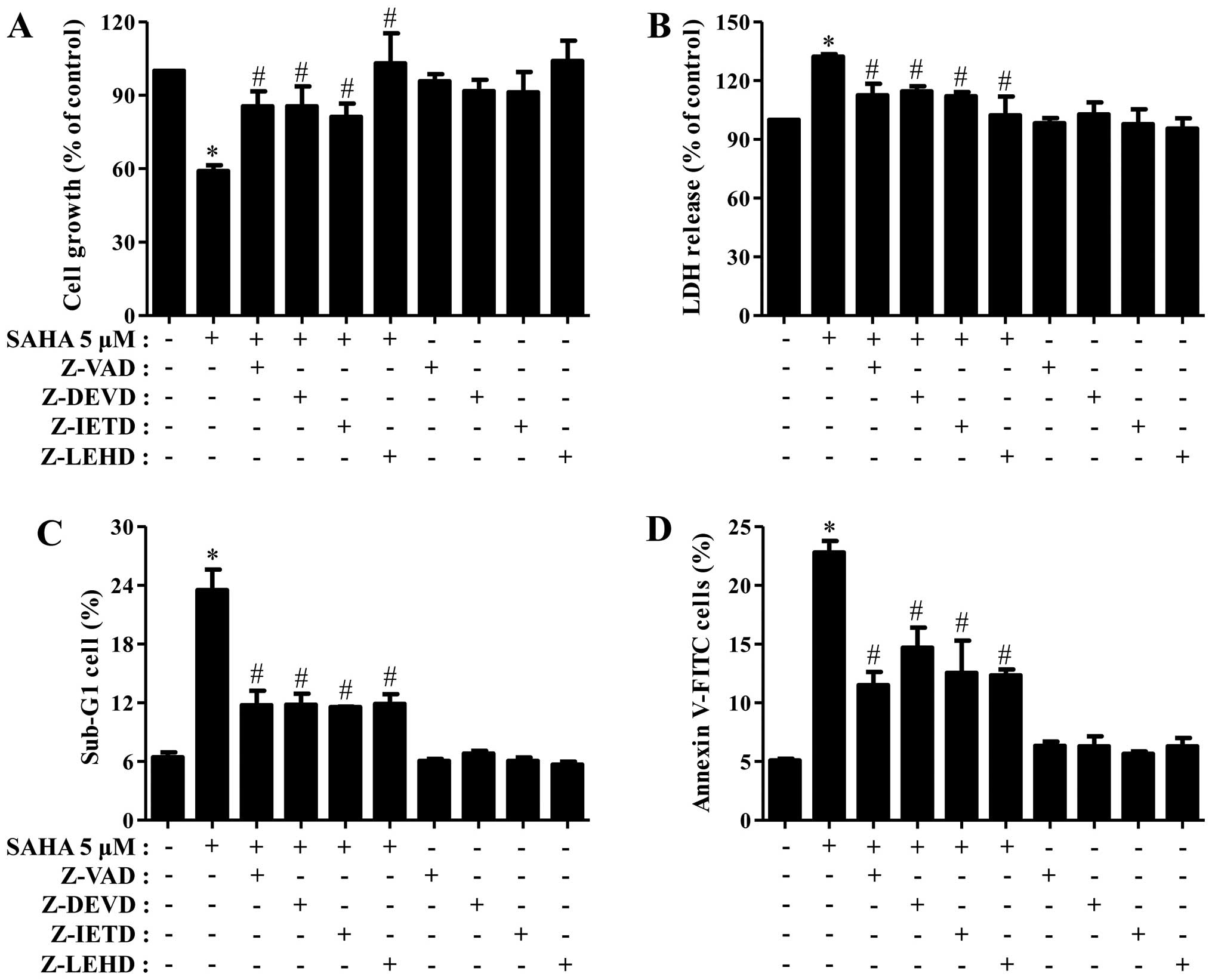

Next, we determined which caspase is involved in Phi

cell death and growth inhibition induced by SAHA. As shown Fig. 3A and B, all the tested caspase

inhibitors partially recovered the growth inhibition and LDH

release of SAHA-treated Phi cells. In addition, all the inhibitors

strongly reduced the percents of sub-G1 cells and Annexin V-FITC

cells in these cells (Fig. 3C and

D).

Effects of HDAC1 siRNA on cell growth and

death in SAHA-treated Phi cells

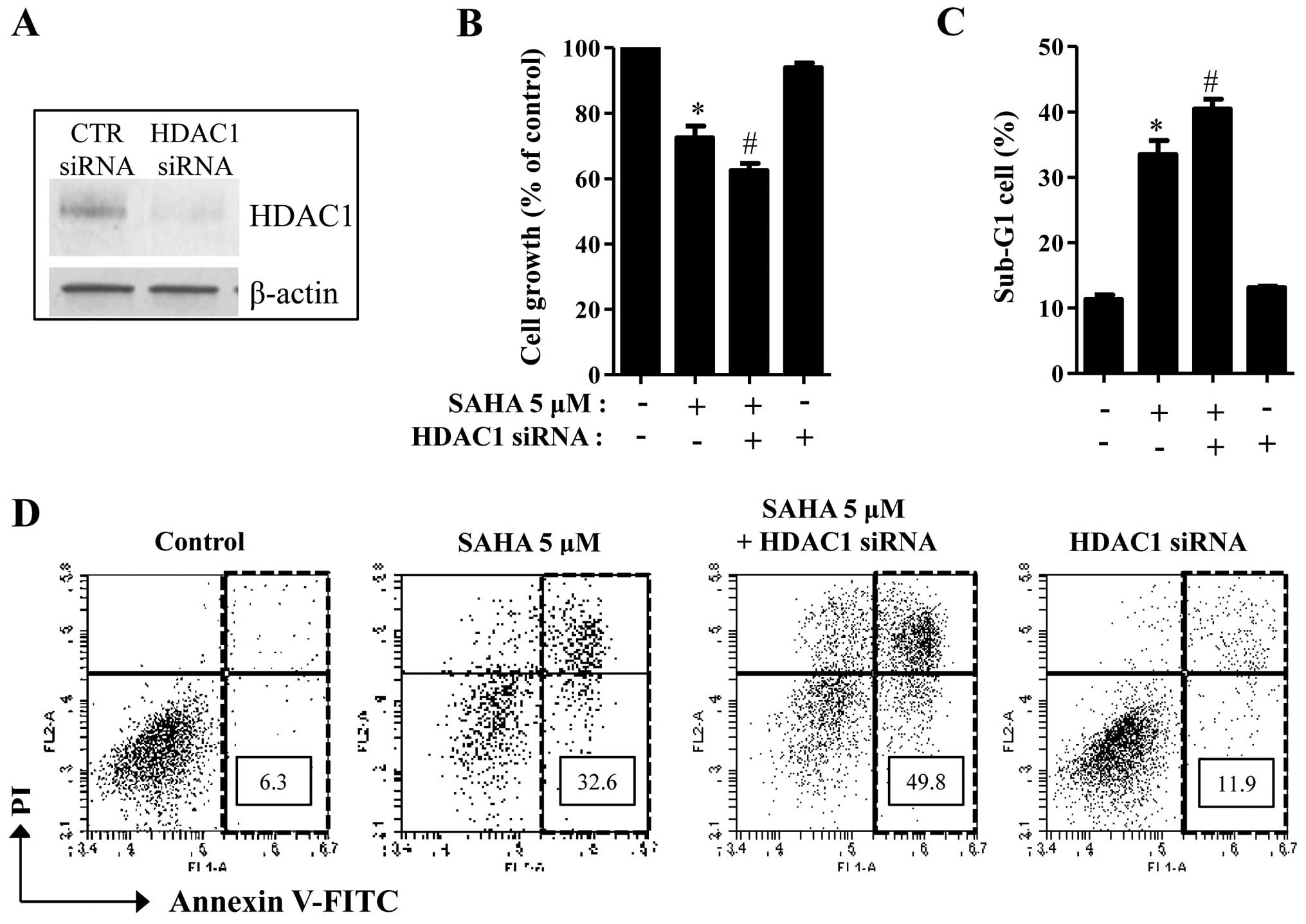

Because the basal levels of HDAC1 were different

between SAHA-sensitive and SAHA-resistant mesothelioma cells

(Figs. 1 and 2), the status of HDAC1 might influence

mesothelioma cell death caused by SAHA. To investigate whether

HDAC1 protein affects SAHA-induced cell death in mesothelioma, the

mRNA level of HDAC1 was knocked downed by the administration of

siRNA. The knockdown of HDAC1 successfully occurred in Phi cells

via its siRNA (Fig. 4A). HDAC1

siRNA significantly promoted cell growth inhibition in SAHA-treated

Phi cells (Fig. 4B). In addition,

HDAC1 siRNA increased the numbers of sub-G1 cells and Annexin

V-positive cells in these cells (Fig.

4C and D). HDAC1 siRNA alone induced cell death in

SAHA-untreated Phi control cells (Fig.

4D).

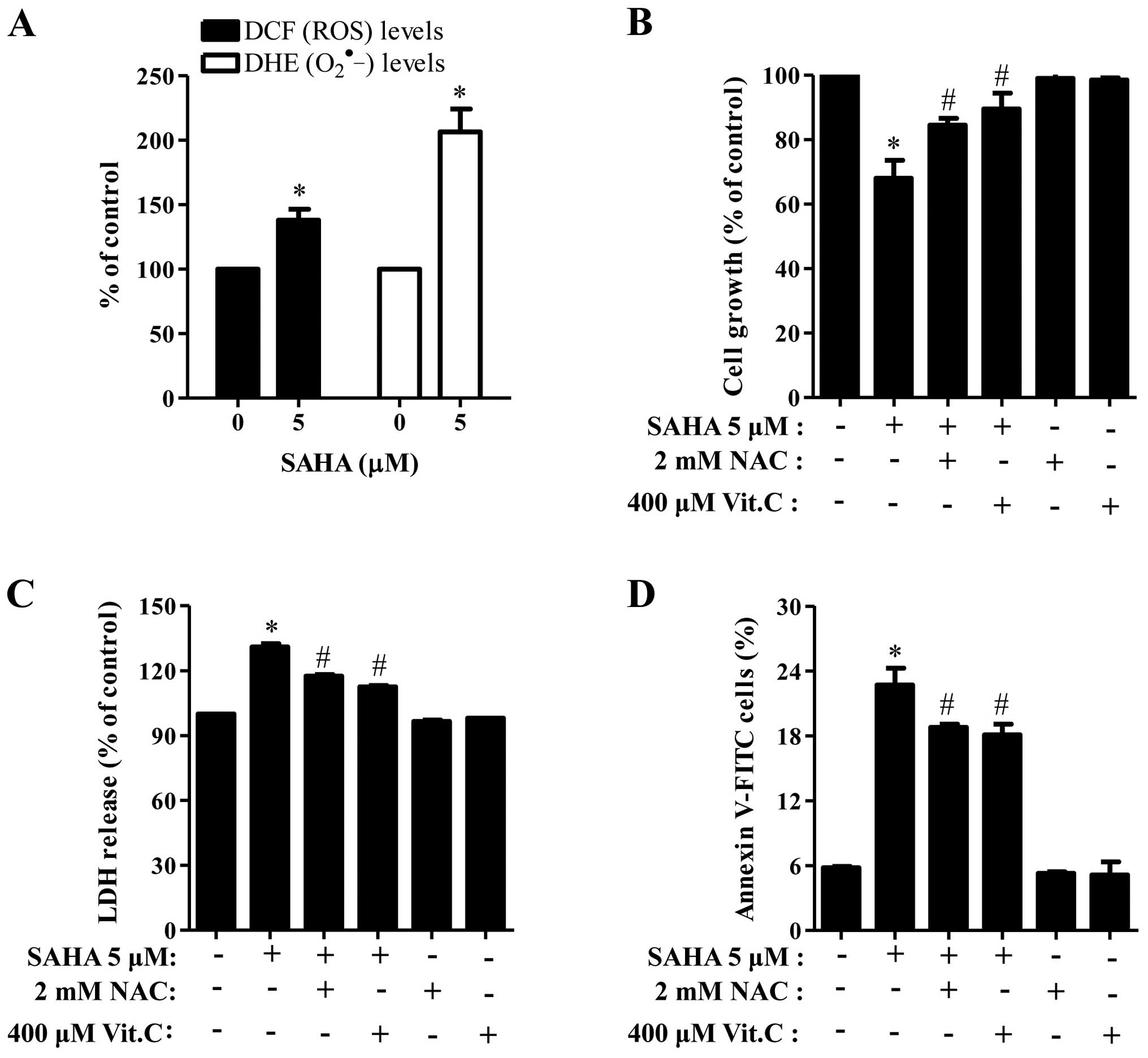

Effects of SAHA on intracellular ROS and

Trx1 levels in SAHA-treated Phi cells

When we measured the intracellular ROS levels by

DCFDA and DHE dyes, 5 μM SAHA significantly increased ROS levels

including O2•− in Phi cells (Fig. 5A). Moreover, well-known

antioxidants, NAC and Vit.C effectively blocked cell growth

inhibition and LDH release in SAHA-treated Phi cells (Fig. 5B and C) and both of them

significantly reduced the number of Annexin V-positive cells in the

cells (Fig. 5D).

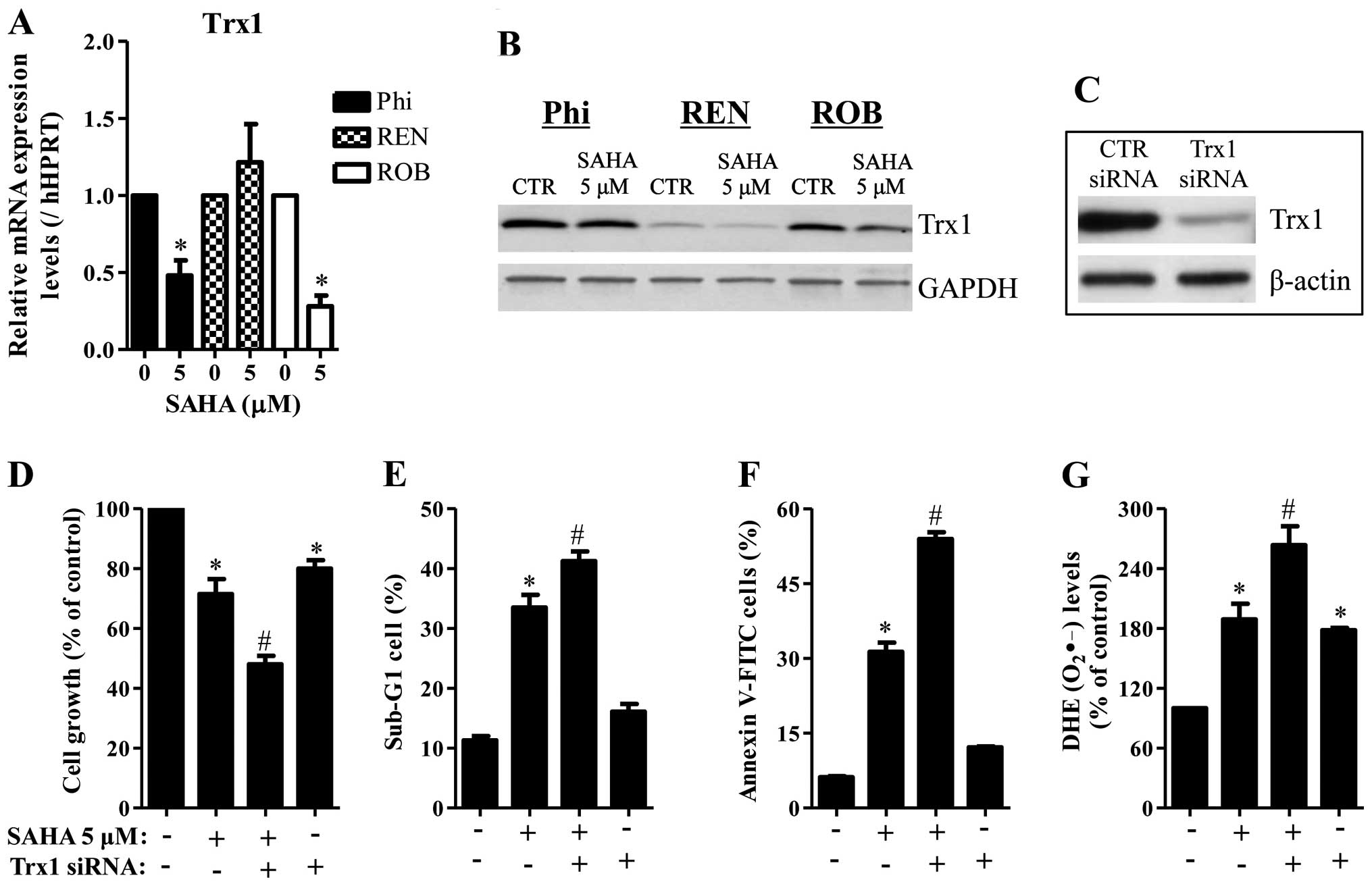

It is reported that SAHA decreased Trx1 in cancer

cells (24). Cellular antioxidants

can change intracellular ROS levels and affect cell death such as

apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 6A and

B, 5 μM SAHA decreased the mRNA and protein levels of Trx1 in

Phi and ROB cells. While SAHA decreased the protein level of Trx1

in REN cells, this agent did not alter the mRNA level of Trx1 in

these cells (Fig. 6A and B). Next,

it was determined whether Trx1 knockdown affects cell growth, cell

death and ROS levels in SAHA-treated Phi cells. Administration of

Trx1 siRNA markedly decreased the level of Trx1 (Fig. 6C) and this siRNA enhanced cell

growth inhibition in SAHA-untreated and -treated Phi cells

(Fig. 6D). Trx1 siRNA also

increased the percents of sub-G1 cells and apoptotic cells in these

cells (Fig. 6E and F).

Furthermore, Trx1 siRNA increased the O2•−

levels in SAHA-untreated and -treated Phi cells (Fig. 6G).

Discussion

Mesothelioma is a rare form of cancer derived from

the pleura, peritoneum or pericardium. Epigenetic changes affect

drug resistance and pathogenesis of mesothelioma. In the present

study, we determined an anticancer effect of SAHA on various

mesothelioma cells in view of HDAC1 and Trx1 levels. SAHA inhibited

the growth of Phi and ROB mesothelioma cells. This result supports

that HDAC inhibitor shows anti-tumor effect on mesothelioma

(9,25). However, this drug did not affect

the growth of ADA and Mill mesothelioma cells. Interestingly,

SAHA-sensitive Phi and ROB cells strongly expressed the basal level

of HDAC1 protein whereas SAHA-resistant ADA and Mill cells showed

lower basal levels of HDAC1. Moreover, SAHA notably inhibited HDAC

activity and induced acetylation of H4 in SAHA-sensitive Phi cells.

This result implies that SAHA as an HDAC inhibitor especially works

well in mesothelioma cells having overexpressed HDAC1 protein. In

addition, the different levels of HDAC1 among mesothelioma cells

seemed to differently influence the sensitivity of mesothelioma

cells to HDAC inhibitor. Many studies have reported that inhibition

of HDAC1 enhances cell death in various cancer cells including

ovarian and liver (26,27). Likewise, HDAC1 knockdown enhanced

Phi cell death caused by SAHA. Taken together, HDAC1 might be a

target for the mesothelioma therapy.

SAHA induced apoptosis in Phi cells which was

accompanied by the cleavages of PARP and caspase-3 and the loss of

MMP (ΔΨm). In addition, all the tested caspase inhibitors strongly

prevented cell death in these cells. Therefore, it seems that

apoptosis occurs via intrinsic and extrinsic pathways and that cell

death is the main mechanism for the inhibition of cell growth by

SAHA. We also observed that SAHA induced LDH release in

SAHA-treated Phi cells. However, NecroX-2 and necrostatin1,

necrosis inhibitors did not significantly attenuate cell death in

SAHA-treated Phi cells (data not shown). Therefore, necrosis seems

to be in part related to SAHA-induced Phi cell death.

Oxidative stress is an important cause in

mesothelioma cell death and antioxidant contributes the drug

resistance of mesothelioma cells. Likewise, SAHA increased the

intracellular ROS levels including O2•− in

Phi cells. Both NAC and Vit.C prevented the growth inhibition and

cell death in SAHA-treated Phi cells. SAHA did not change ROS level

in ADA cells which was resistant to this drug (data not shown).

Therefore, these results suggest that oxidative stress induced by

SAHA leads to apoptotic cell death in Phi mesothelioma cells.

Trx is an important antioxidant protein in cells and

it protects the cell from oxidative stress damage by facilitating

the reduction of other oxidative proteins via cysteine

thiol-disulfide exchange (28).

HDAC inhibitor changes the redox state of Trx (29). In the present study, SAHA

downregulated the mRNA and protein levels of Trx1 in Phi and ROB

cells. In addition, Trx1 siRNA sensitized Phi cells to SAHA and it

alone induced apoptosis in SAHA-untreated Phi cells. These results

imply that Trx1 has a critical role in cell death in mesothelioma

cells. In regard to ROS levels, Trx1 siRNA intensified the

O2•− level in SAHA-treated and untreated Phi

cells. This result suggests that Trx1 also act as a strong

antioxidant in mesothelioma cells.

In conclusion, SAHA inhibited the growth of Phi and

ROB cells among the tested human mesothelioma cells. These cells

relatively have higher levels of HDACs. SAHA-induced Phi cell death

was related to oxidative stress and Trx1 levels.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Peter R. Hoffmann and Dr Pietro

Bertino for providing mesothelioma cells. The present study was

supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant

funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (no. 2008-0062279) and

supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the NRF

funded by the Ministry of Education (2013006279).

Abbreviations:

|

SAHA

|

suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

|

|

HAT

|

histone acetyltransferase

|

|

HDAC

|

histone deacetylase

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

FITC

|

fluorescein isothiocyanate

|

|

MMP (ΔΨm)

|

mitochondrial membrane potential

|

|

NAC

|

N-acetylcysteine

|

|

Vit.C

|

vitamin C

|

|

LDH

|

lactate dehydrogenase

|

|

H2DCFDA

|

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein

diacetate

|

|

DHE

|

dihydroethidium

|

|

Trx

|

thioredoxin

|

|

siRNA

|

small interfering RNA

|

References

|

1

|

Comertpay S, Pastorino S, Tanji M,

Mezzapelle R, Strianese O, Napolitano A, Baumann F, Weigel T,

Friedberg J, Sugarbaker P, et al: Evaluation of clonal origin of

malignant mesothelioma. J Transl Med. 12:3012014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Carbone M and Yang H: Molecular pathways:

Targeting mechanisms of asbestos and erionite carcinogenesis in

mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res. 18:598–604. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

3

|

Matsuzaki H, Maeda M, Lee S, Nishimura Y,

Kumagai-Takei N, Hayashi H, Yamamoto S, Hatayama T, Kojima Y,

Tabata R, et al: Asbestos-induced cellular and molecular alteration

of immuno-competent cells and their relationship with chronic

inflammation and carcinogenesis. J Biomed Biotechnol.

2012:4926082012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Godleski JJ,

Marsit CJ, Longacker JL, Roelofs CR, Karagas MR, Wrensch MR, Yeh

RF, Nelson HH, et al: Epigenetic profiles distinguish pleural

mesothelioma from normal pleura and predict lung asbestos burden

and clinical outcome. Cancer Res. 69:227–234. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Karczmarski J, Rubel T, Paziewska A,

Mikula M, Bujko M, Kober P, Dadlez M and Ostrowski J: Histone H3

lysine 27 acetylation is altered in colon cancer. Clin Proteomics.

11:242014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kalari S, Moolky N, Pendyala S, Berdyshev

EV, Rolle C, Kanteti R, Kanteti A, Ma W, He D, Husain AN, et al:

Sphingosine kinase 1 is required for mesothelioma cell

proliferation: Role of histone acetylation. PLoS One. 7:e453302012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kim NH, Kim SN and Kim YK: Involvement of

HDAC1 in E-cadherin expression in prostate cancer cells; its

implication for cell motility and invasion. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 404:915–921. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hayashi A, Horiuchi A, Kikuchi N, Hayashi

T, Fuseya C, Suzuki A, Konishi I and Shiozawa T: Type-specific

roles of histone deacetylase (HDAC) overexpression in ovarian

carcinoma: HDAC1 enhances cell proliferation and HDAC3 stimulates

cell migration with downregulation of E-cadherin. Int J Cancer.

127:1332–1346. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Paik PK and Krug LM: Histone deacetylase

inhibitors in malignant pleural mesothelioma: Preclinical rationale

and clinical trials. J Thorac Oncol. 5:275–279. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Katafygiotis P, Giaginis C, Patsouris E

and Theocharis S: Histone deacetylase inhibitors as potential

therapeutic agents for the treatment of malignant mesothelioma.

Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 13:476–482. 2013.

|

|

11

|

Schieber M and Chandel NS: ROS function in

redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 24:R453–R462.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tabata C, Terada T, Tabata R, Yamada S,

Eguchi R, Fujimori Y and Nakano T: Serum thioredoxin-1 as a

diagnostic marker for malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. J Clin

Gastroenterol. 47:e7–e11. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Thompson JK, Westbom CM, MacPherson MB,

Mossman BT, Heintz NH, Spiess P and Shukla A: Asbestos modulates

thioredoxin-thioredoxin interacting protein interaction to regulate

inflammasome activation. Part Fibre Toxicol. 11:242014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Murthy S, Adamcakova-Dodd A, Perry SS,

Tephly LA, Keller RM, Metwali N, Meyerholz DK, Wang Y, Glogauer M,

Thorne PS, et al: Modulation of reactive oxygen species by Rac1 or

catalase prevents asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol

Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 297:L846–L855. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Powis G and Kirkpatrick DL: Thioredoxin

signaling as a target for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol.

7:392–397. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang J, Yang H, Li W, Xu H, Yang X and Gan

L: Thioredoxin 1 upregulates FOXO1 transcriptional activity in drug

resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1852:395–405. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Min A, Im SA, Kim DK, Song SH, Kim HJ, Lee

KH, Kim TY, Han SW, Oh DY, Kim TY, et al: Histone deacetylase

inhibitor, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), enhances

anti-tumor effects of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)

inhibitor olaparib in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast

Cancer Res. 17:332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ding L, Zhang Z, Liang G, Yao Z, Wu H,

Wang B, Zhang J, Tariq M, Ying M and Yang B: SAHA triggered MET

activation contributes to SAHA tolerance in solid cancer cells.

Cancer Lett. 356:828–836. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hurwitz JL, Stasik I, Kerr EM, Holohan C,

Redmond KM, McLaughlin KM, Busacca S, Barbone D, Broaddus VC, Gray

SG, et al: Vorinostat/SAHA-induced apoptosis in malignant

mesothelioma is FLIP/caspase 8-dependent and HR23B-independent. Eur

J Cancer. 48:1096–1107. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Han YH, Kim SZ, Kim SH and Park WH:

Pyrogallol inhibits the growth of lung cancer Calu-6 cells via

caspase-dependent apoptosis. Chem Biol Interact. 177:107–114. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

You BR and Park WH: Gallic acid-induced

lung cancer cell death is related to glutathione depletion as well

as reactive oxygen species increase. Toxicol In Vitro.

24:1356–1362. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

You BR, Kim SH and Park WH: Reactive

oxygen species, glutathione, and thioredoxin influence suberoyl

bishydroxamic acid-induced apoptosis in A549 lung cancer cells.

Tumour Biol. 36:3429–3439. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

You BR, Shin HR, Han BR and Park WH: PX-12

induces apoptosis in Calu-6 cells in an oxidative stress-dependent

manner. Tumour Biol. 36:2087–2095. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Butler LM, Zhou X, Xu WS, Scher HI,

Rifkind RA, Marks PA and Richon VM: The histone deacetylase

inhibitor SAHA arrests cancer cell growth, up-regulates

thioredoxin-binding protein-2, and down-regulates thioredoxin. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 99:11700–11705. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Crisanti MC, Wallace AF, Kapoor V,

Vandermeers F, Dowling ML, Pereira LP, Coleman K, Campling BG,

Fridlender ZG, Kao GD, et al: The HDAC inhibitor panobinostat

(LBH589) inhibits mesothelioma and lung cancer cells in vitro and

in vivo with particular efficacy for small cell lung cancer. Mol

Cancer Ther. 8:2221–2231. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Xie HJ, Noh JH, Kim JK, Jung KH, Eun JW,

Bae HJ, Kim MG, Chang YG, Lee JY, Park H, et al: HDAC1 inactivation

induces mitotic defect and caspase-independent autophagic cell

death in liver cancer. PLoS One. 7:e342652012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Cacan E, Ali MW, Boyd NH, Hooks SB and

Greer SF: Inhibition of HDAC1 and DNMT1 modulate RGS10 expression

and decrease ovarian cancer chemoresistance. PLoS One.

9:e874552014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chae JS, Gil Hwang S, Lim DS and Choi EJ:

Thioredoxin-1 functions as a molecular switch regulating the

oxidative stress-induced activation of MST1. Free Radic Biol Med.

53:2335–2343. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ungerstedt J, Du Y, Zhang H, Nair D and

Holmgren A: In vivo redox state of human thioredoxin and redox

shift by the histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide

hydroxamic acid (SAHA). Free Radic Biol Med. 53:2002–2007. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|