Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), the most prevalent

histological subtype of lung cancer worldwide, continues to present

significant clinical challenges (1,2).

Although advances in diagnostic techniques, surgical approaches,

chemotherapy and molecular therapies have significantly improved

patient outcomes, the 5-year survival rate for patients with LUAD

remains persistently low (3,4).

Emerging research indicates that specific molecular signatures show

promise as prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

While recent technological advances have expanded

the toolbox for lung cancer management, such as self-assembled DNA

machines enabling portable circulating tumor cells (CTC)

quantification for liquid biopsy (5), macrophage-mediated targeted delivery

systems delivering sulphate-based nanomedicines to overcome

therapeutic resistance (6), and

nano-adjuvants enhancing radiotherapeutic efficacy in non-small

cell lung cancer (7), these

approaches predominantly address downstream clinical

manifestations. Crucially, they lack molecular drivers capable of

simultaneously predicting prognosis and guiding dynamic treatment

adaptation. Copper metabolism has emerged as an upstream regulator

that links tumour proliferation, immune evasion, and therapeutic

response; notably, cuproptosis directly modulates CTC viability and

radiochemical sensitivity through mitochondrial proteotoxicity. In

the present study, this mechanistic gap was bridged by establishing

a cuproptosis-related long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) signature that

not only prognostically stratifies LUAD but also predicts the

suitability of nanomedicine/immunotherapy, positioning copper

homeostasis as a nexus for precision theranostics.

Cuproptosis is a form of copper-dependent cell death

driven by mitochondrial copper (Cu) accumulation, proteotoxic

stress, and dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (DLAT) aggregation

(8,9). While dysregulated copper homeostasis

is implicated in cancer, its interplay with lncRNAs in LUAD remains

unexplored. In humans, Cu accumulation is life-threatening, yet

there may be a window of opportunity where Cu accumulation can

eliminate cancer cells in a selective manner (10). This information might be used to

elucidate the pathology of genetic diseases associated with Cu

overload and offers a new way to treat cancer by targeting Cu

toxicity. lncRNAs modulate immune evasion (PD-L1 stabilization),

metastasis (epithelial-mesenchymal transition activation), and

therapeutic resistance (enhanced DNA repair) in patients with LUAD

(11). lncRNAs serve as molecular

bridges connecting copper dysregulation to LUAD aggressiveness.

Currently, cuproptosis-related lncRNAs have been less studied.

In the present study, the gene expression data of

16,876 lncRNAs and 19 cuproptosis-related genes from The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA)-LUAD dataset were initially extracted. In

addition, cuproptosis-associated lncRNAs were identified through

Pearson correlation analysis. A prognostic model was constructed to

predict the overall survival (OS) of patients with LUAD. The

association of the model with immunotherapy response was explored.

A nomogram combining the model and significant clinical features of

LUAD was established. Finally, candidate agents targeting the RNA

signature were investigated using the public GDSC database.

Therefore, the primary objectives of this study were

i) to systematically identify cuproptosis-associated lncRNAs in

LUAD using transcriptomic data; ii) to construct and rigorously

validate a prognostic signature based on these lncRNAs for

stratifying patients with LUAD according to OS risk; iii) to

comprehensively evaluate the association of this signature with the

tumour immune microenvironment and predicted response to

immunotherapy, specifically utilizing the TIDE algorithm; iv) to

screen for potential therapeutic compounds targeting high-risk

patients using the GDSC database; and v) to experimentally validate

the expression patterns of the signature lncRNAs in LUAD cell

lines. By integrating prognostic stratification, immunotherapy

response prediction, drug sensitivity screening, and experimental

validation specifically for LUAD, the aim of the present study was

to establish a novel cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature as a

clinically actionable theragnostic tool.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition and preprocessing

Data sources

RNA transcriptome data (FPKM-normalized), clinical

data (age, sex, AJCC TNM stage, survival status), and somatic

mutation data for patients with LUAD (n=515) were obtained from the

TCGA database (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/).

Acquisition of cuproptosis-associated

lncRNAs

Gene expression files of lncRNAs and

cuproptosis-related genes were downloaded from the TCGA database.

In total, 19 cuproptosis-related genes, namely, NFE2L2, NLRP3,

ATP7B, ATP7A, SLC31A1, FDX1, LIAS, LIPT1, LIPT2, DLD, DLAT, PDHA1,

PDHB, MTF1, GLS, CDKN2A, DBT, GCSH and DLST (8,12-16),

were obtained.

Identification of cuproptosis-related

lncRNAs. Correlation analysis

Pearson correlation coefficients (R) were calculated

between the expression levels of each of the 19 curated

cuproptosis-related genes and all the annotated lncRNAs (n=16,876)

within the TCGA-LUAD cohort.

Selection thresholds. Correlation Strength

(|R|>0.3): This threshold was chosen to identify lncRNAs with

moderate-to-strong co-expression relationships with

cuproptosis-related genes. A value >0.3 is a commonly accepted

benchmark in transcriptomic studies for identifying biologically

relevant co-expression partners, balancing specificity against

overly stringent exclusion of potentially important regulators.

Statistical significance. This stringent

P-value threshold minimizes false positives, ensuring that only

lncRNAs with a highly statistically significant association with at

least one cuproptosis gene were retained.

Scope. lncRNAs meeting the above |R| and p

criteria for any one or more of the 19 cuproptosis-related genes

were included. This broad approach captures lncRNAs potentially

regulating specific facets of cuproptosis without requiring

universal association with all the cuproptosis-related genes.

Output. The application of these criteria

resulted in the identification of 3,385 cuproptosis-related lncRNAs

for subsequent prognostic model construction.

Construction and validation of the lncRNA

signature. TCGA-LUAD samples (n=515) were stratified by AJCC

stage (I/II vs. III/IV) and survival status (alive/dead) and then

randomly partitioned into training (70%, n=360) and test (30%,

n=155) sets (random seed=2023) to preserve prognostic factor

distributions. This 70:30 split adheres to the TRIPOD guidelines

for prognostic model development. Using the training cohort, a

cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature was developed, which was

subsequently validated in the test cohort. Prognostic lncRNAs were

initially screened from 3,385 cuproptosis-associated candidates

based on OS in the TCGA-LUAD cohort (P<0.05). These were

subsequently refined via LASSO-Cox regression analysis (R package

‘glmnet’), yielding a final signature of 52 lncRNAs (17). Further multivariate Cox regression

identified 4 lncRNAs, which were used to construct a prognostic

lncRNA signature. A risk score was accordingly established and

formulated as follows: Risk score=[coef (lncRNA1) x expr (lncRNA1)]

+ coef(lncRNA2) x expr (lncRNA2)] +......+ [coef(lncRNAn) x expr

(lncRNAn)]NA2)] +......+ [coef(lncRNAn) x expr (lncRNAn)]; where

coef (lncRNAn) represents the Cox regression coefficient and expr

(lncRNAn) represents the expression of lncRNAn. Samples from the

training and test sets were grouped based on their risk scores

(18).

Immune microenvironment and therapy

response analysis. Tumour mutation burden (TMB)

Somatic mutations were processed using maftools

(v2.12.0; https://bioconductor.org/packages/maftools/). TMB

equals to (total mutations)/[exome size (38 Mb)].

Immunotherapy response prediction. The TIDE

algorithm (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) was applied to predict

the anti-PD1/CTLA4 response.

Immune cell infiltration. The data were

estimated using CIBERSORTx and ssGSEA (R package GSVA).

Drug sensitivity screening. IC50

values for 73 GDSC compounds were predicted using pRRophetic (v0.5;

https://bioconductor.org/packages/pRRophetic/) based

on the TCGA transcriptomes.

Functional analysis. Gene Ontology (GO) and

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses

were performed using the R package ‘clusterProfiler’ to

characterize the biological functions of the signature lncRNAs

(P<0.05).

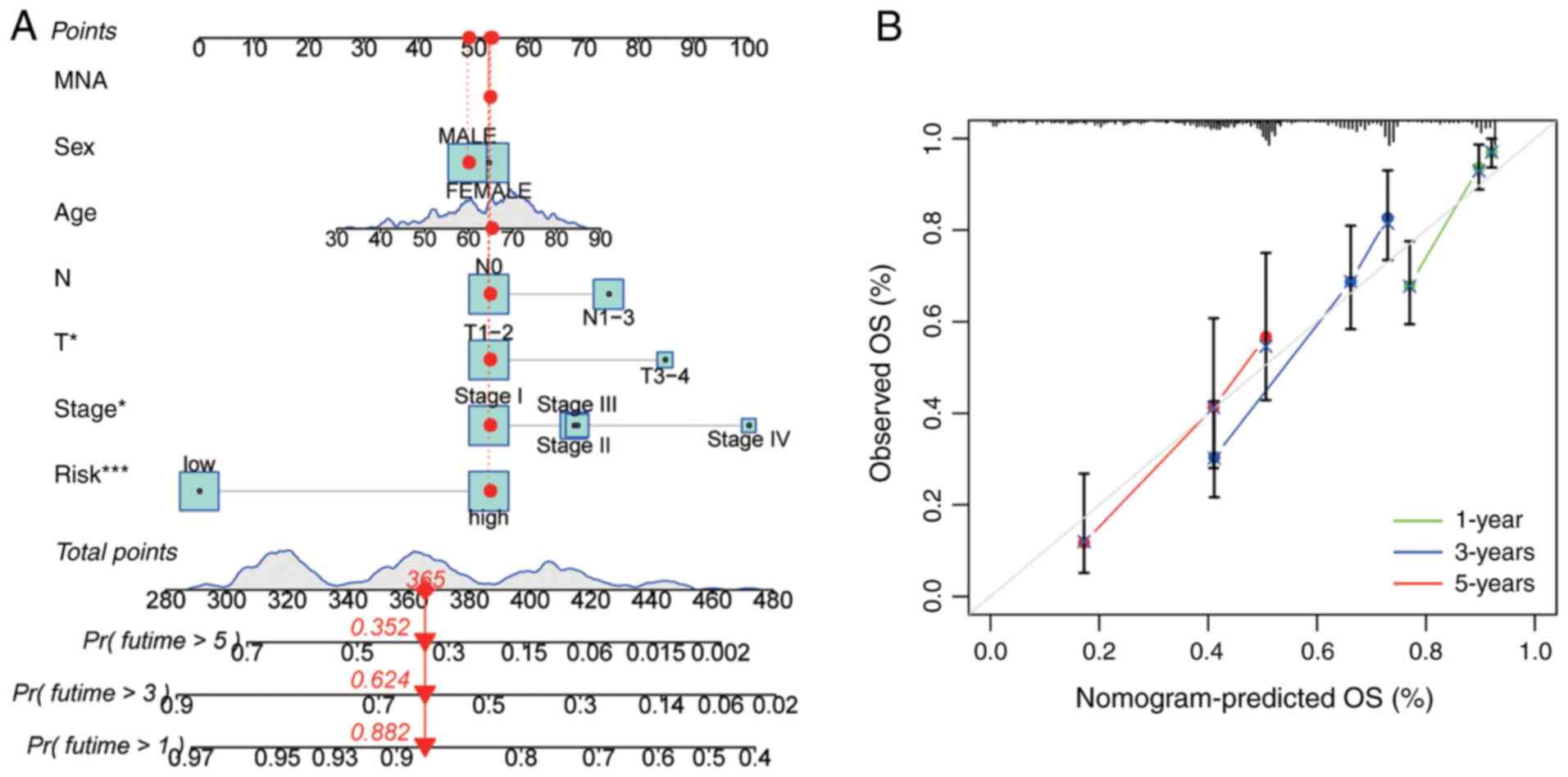

Nomogram construction and validation. A

nomogram incorporating the risk score, age, sex, and TNM stage

classification was developed to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS in

patients with LUAD. Calibration performance was assessed using the

Hosmer-Lemeshow test to evaluate the agreement between the

predicted and observed outcomes.

Survival analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival

analysis was performed to compare OS and other survival endpoints

[including progression-free interval (PFI), disease-specific

survival (DSS), and disease-free interval (DFI)] between the

high-risk and low-risk patient groups stratified by the median risk

score. The statistical significance of the differences in survival

curves was assessed using the two-sided log-rank test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Construction of an ARHGEF26-AS1-associated

competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) Network. The ceRNA network

focused on ARHGEF26-AS1 was constructed by first predicting its

interacting miRNAs using miRanda (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do) and

DIANA-LncBase (https://diana.imis.athena-innovation.gr/DianaTools/index.php).

The downstream target genes of these miRNAs were then retrieved

from the StarBase database (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/), focusing on

interactions supported by experimental evidence. The integrated

network, depicting ARHGEF26-AS1, miRNAs, and target genes, was

finally assembled and visualized using Cytoscape.

Cell culture. Normal human bronchial

epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) and human LUAD cells (A549) (Fuheng

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were maintained in DMEM (HyClone; Cytiva)

and RPMI 1640-medium (HyClone; Cytiva), respectively. Both media

were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were

incubated at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5%

CO2.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR). Total RNA was extracted from BEAS-2B and A549 cells

using TRIzol® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). RNA purity/concentration was measured by a NanoDrop 2000

(A260/A280 >1.8). For lncRNA analysis, 1 µg of total RNA was

treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to remove

genomic DNA contamination, followed by cDNA synthesis using M-MLV

Reverse Transcriptase (Promega Corporation) with random hexamers

(50 ng/µl) and dNTPs (0.5 mM) in a 20 µl reaction. The thermal

profile for reverse transcription was as follows: 25˚C for 10 min

(priming), 42˚C for 50 min (synthesis), and 70˚C for 15 min

(inactivation). qPCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq™

(TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) on a QuantStudio 6 Flex system (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the following

thermal cycling conditions: An initial denaturation at 95˚C for 30

sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95˚C for 5 sec and 60˚C for 30 sec. A

melt curve analysis was generated at the end of each run.

lncRNA-specific primers (Table

SI) were designed with the following criteria: amplicon length:

80-150 bp; GC content: 40-60%; no secondary structures (validated

by OligoAnalyzer); and spanning exon-exon junctions (where

applicable). β-actin was used as a reference gene. The

2-ΔΔCq method (19) was

utilized to assess fold changes. Raw Ct values and amplification

curves are provided in Table

SII.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software

(version 4.1.2; https://cran.r-project.org). A two-sided P<0.05 was

considered to indicate statistical significance. For the

differential expression analysis of the 4 lncRNAs in LUAD (A549)

versus normal bronchial (BEAS-2B) cells (Fig. S3), an unpaired Student's t-test

was applied to compare the means between the two groups, with

results presented as the mean ± SEM from three technical

replicates; P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Identification of cuproptosis-related

lncRNAs

The present study included 515 patients with LUAD

from the TCGA database. The baseline clinicopathological

characteristics of the entire cohort are summarized in Table SIII. The expression matrices of 19

cuproptosis-related genes and 16,876 lncRNAs were extracted from

the TCGA-LUAD dataset. To identify biologically relevant lncRNAs,

Pearson correlation analysis (|R|>0.3, P<0.001) was performed

between each lncRNA and the 19 cuproptosis-related genes. This

stringent threshold captured lncRNAs with moderate-to-strong

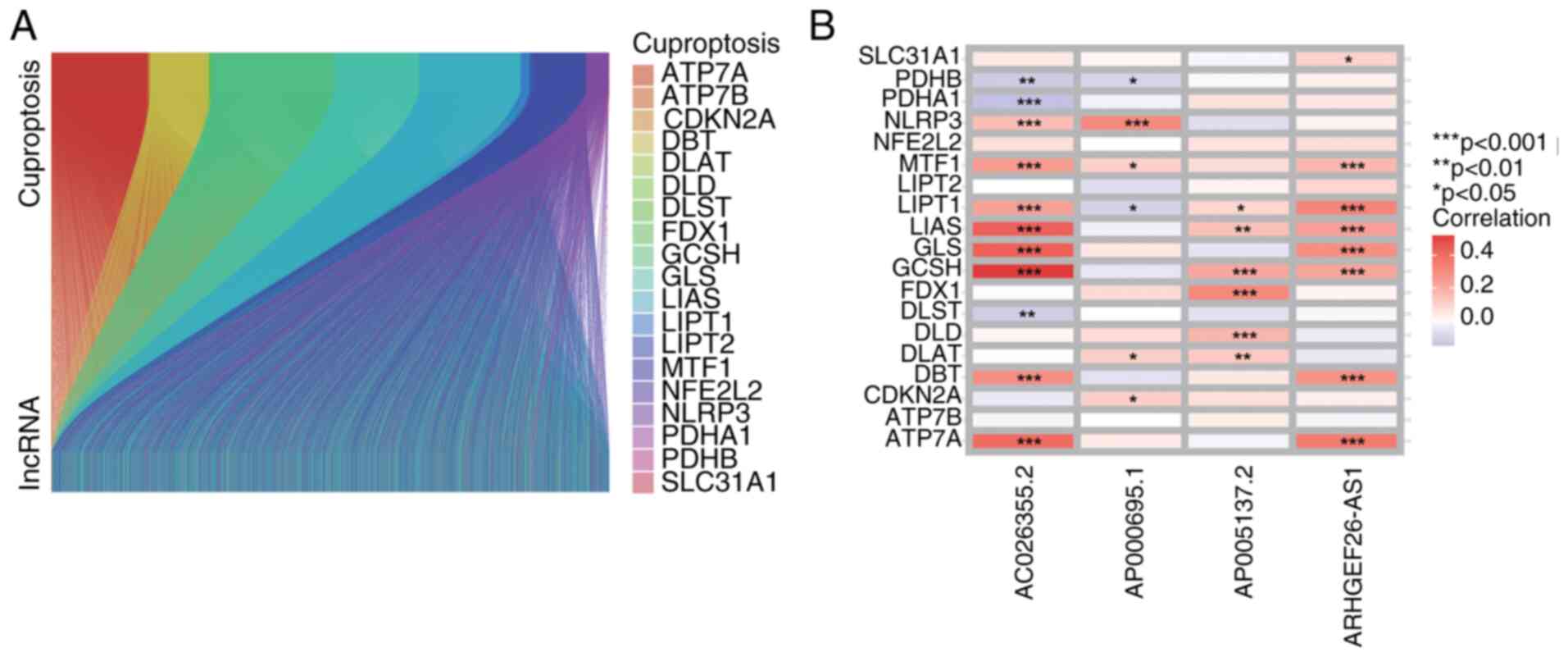

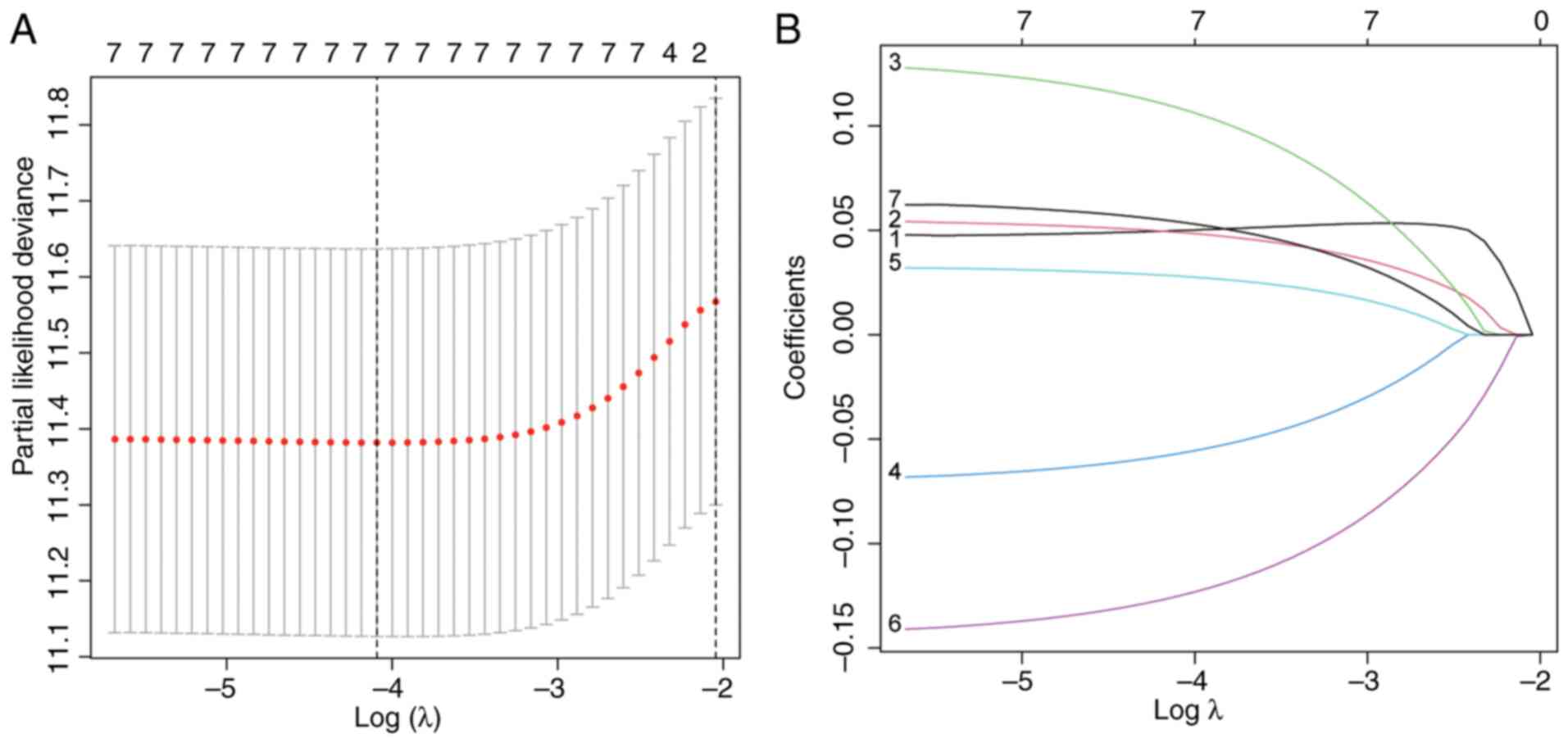

co-expression, yielding 3,385 preliminary candidates (Fig. 1A). Prognostic lncRNA selection

followed a multistep regression framework; univariate Cox analysis

(P<0.05) revealed 52 lncRNAs significantly associated with OS.

LASSO-penalized Cox regression (10-fold cross-validation, λ=0.032)

reduced dimensionality, eliminating multicollinear lncRNAs

(Fig. 2A and B). Multivariate Cox regression further

refined the model, retaining only 4 lncRNAs (AC026355.2,

AP000695.1, ARHGEF26-AS1, and AP005137.2) that independently

predicted survival (P<0.01, Wald test). The correlation between

the 19 cuproptosis-related genes and 4 cuproptosis-related lncRNAs

is demonstrated in Fig. 1B.

Construction and validation of the

cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature

Using the TCGA-LUAD cohort (n=515), a prognostic

signature comprising four cuproptosis-related lncRNAs (AC026355.2,

AP000695.1, ARHGEF26-AS1, and AP005137.2) identified by

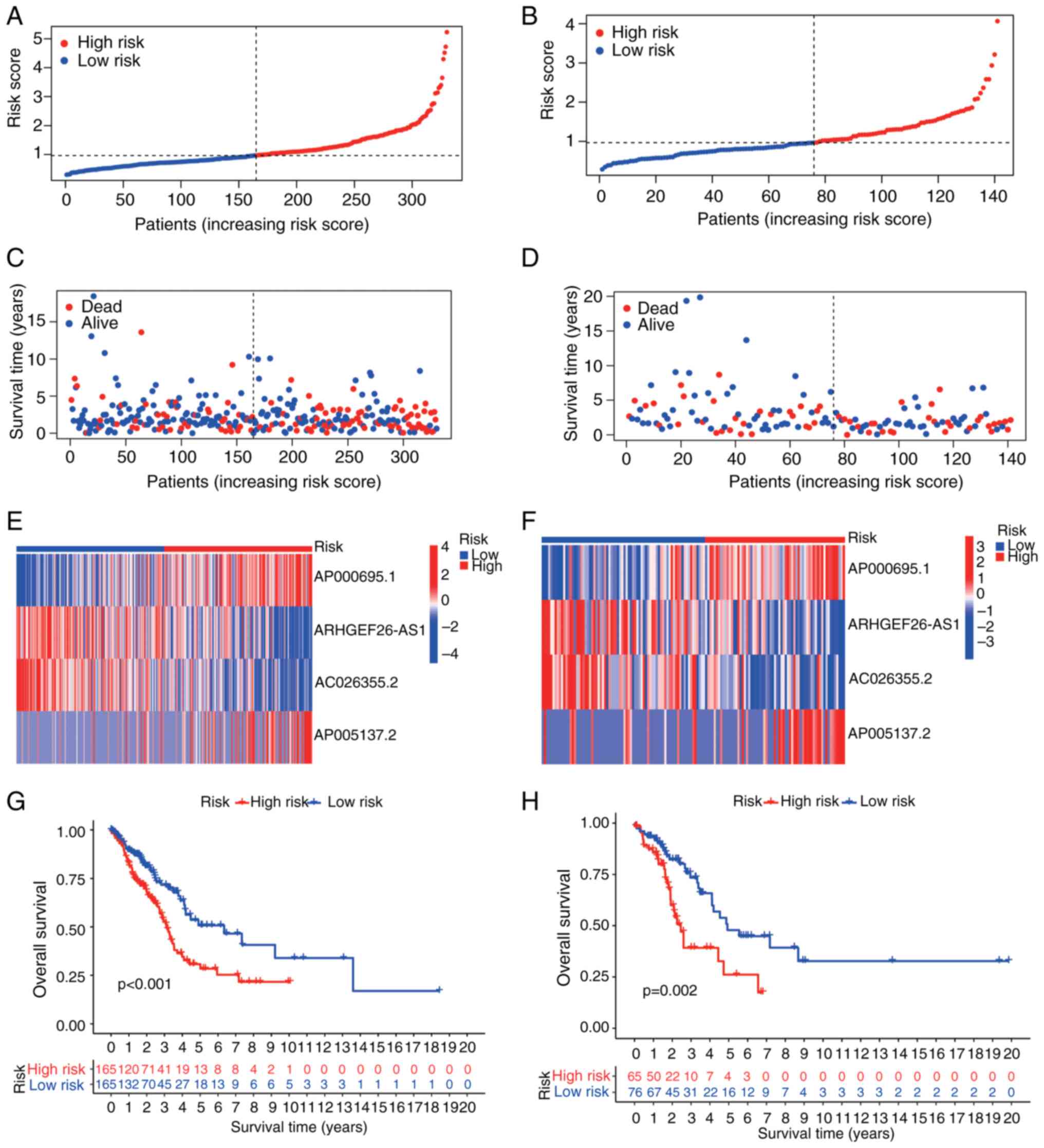

LASSO-penalized Cox regression were established (Fig. 2). Risk scores were computed for

each patient, and the cohorts were stratified into high- and

low-risk subgroups using cohort-specific median risk cut-offs.

Visualization of risk score distributions (Fig. 3A and E), survival status (Fig. 3B and F) and signature lncRNA expression

(Fig. 3C and G) confirmed distinct stratification.

Critically, compared with their low-risk counterparts, high-risk

patients had significantly shorter OS in both the training and test

cohorts (P<0.001; Fig. 3D and

H). The prognostic utility of the

signature was further validated across additional endpoints, with

significant disparities observed in the PFI, DSS and DFI between

risk subgroups (Fig. S1A-C).

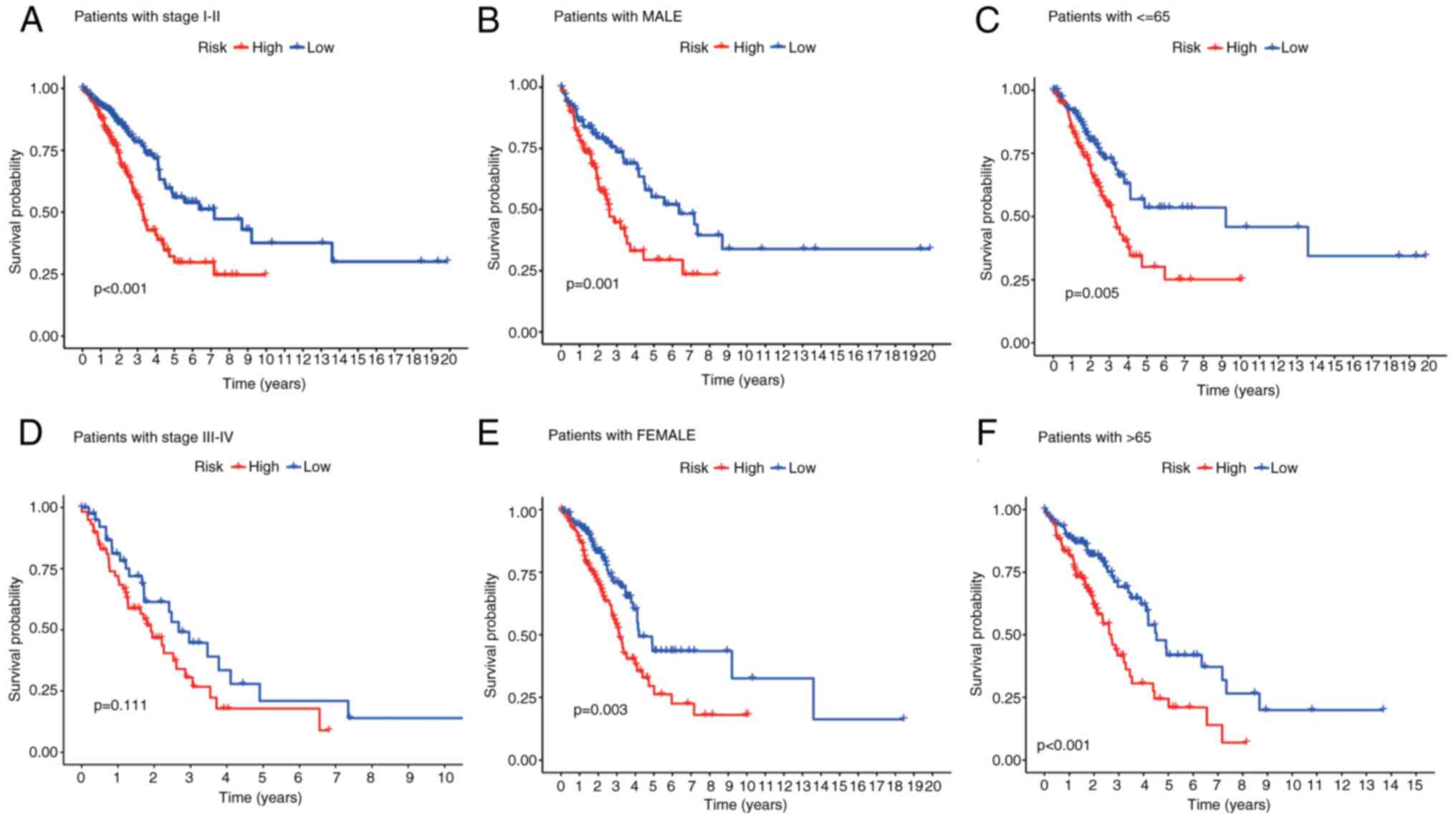

Patient cohorts were further stratified by age, sex

and TNM stage. Across all the subgroups, compared with their

high-risk counterparts, low-risk patients consistently demonstrated

superior OS (Fig. 4A-F). To assess

clinical relevance, the associations of the signature with key

clinicopathological parameters were examined. High-risk patients

had significantly more advanced TNM stages (Stage III-IV) than

low-risk patients did (P=0.002; Fig.

4D). Elevated risk scores were also observed in patients with

lymph node metastasis (N1-N3) compared with N0 patients

(P<0.001; Fig. S2).

Collectively, these findings highlight the utility of the signature

in stratifying LUAD disease severity.

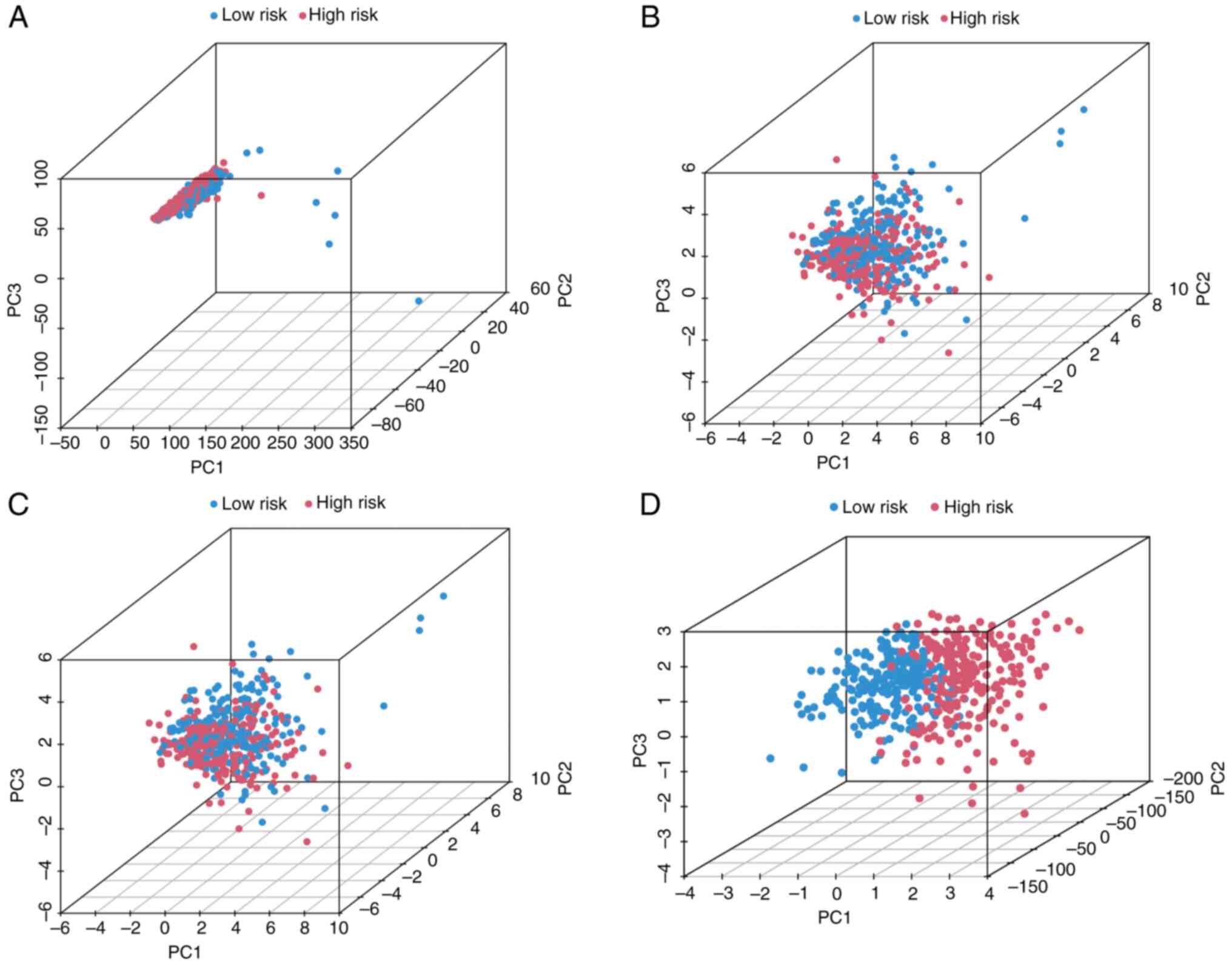

PCA proves the classification

capability of the lncRNA signature

Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted

using four distinct feature sets in the TCGA-LUAD samples: i) the 4

signature cuproptosis-related lncRNAs, ii) 19 established

cuproptosis-associated genes, iii) whole-genome expression

profiles, and iv) risk stratification based on the lncRNA signature

(Fig. 5). The first three

principal components collectively accounted for 58.7% of the total

variance (PC1: 32.4%; PC2: 16.1%; PC3: 10.2%), indicating that

substantial biological heterogeneity was captured by the signature

(Fig. 5A-C). Notably, high- and

low-risk patients presented distinct spatial clustering in PCA

space based on the signature alone (Fig. 5D). This clear separation confirms

the effectiveness of the signature in stratifying patient risk

groups.

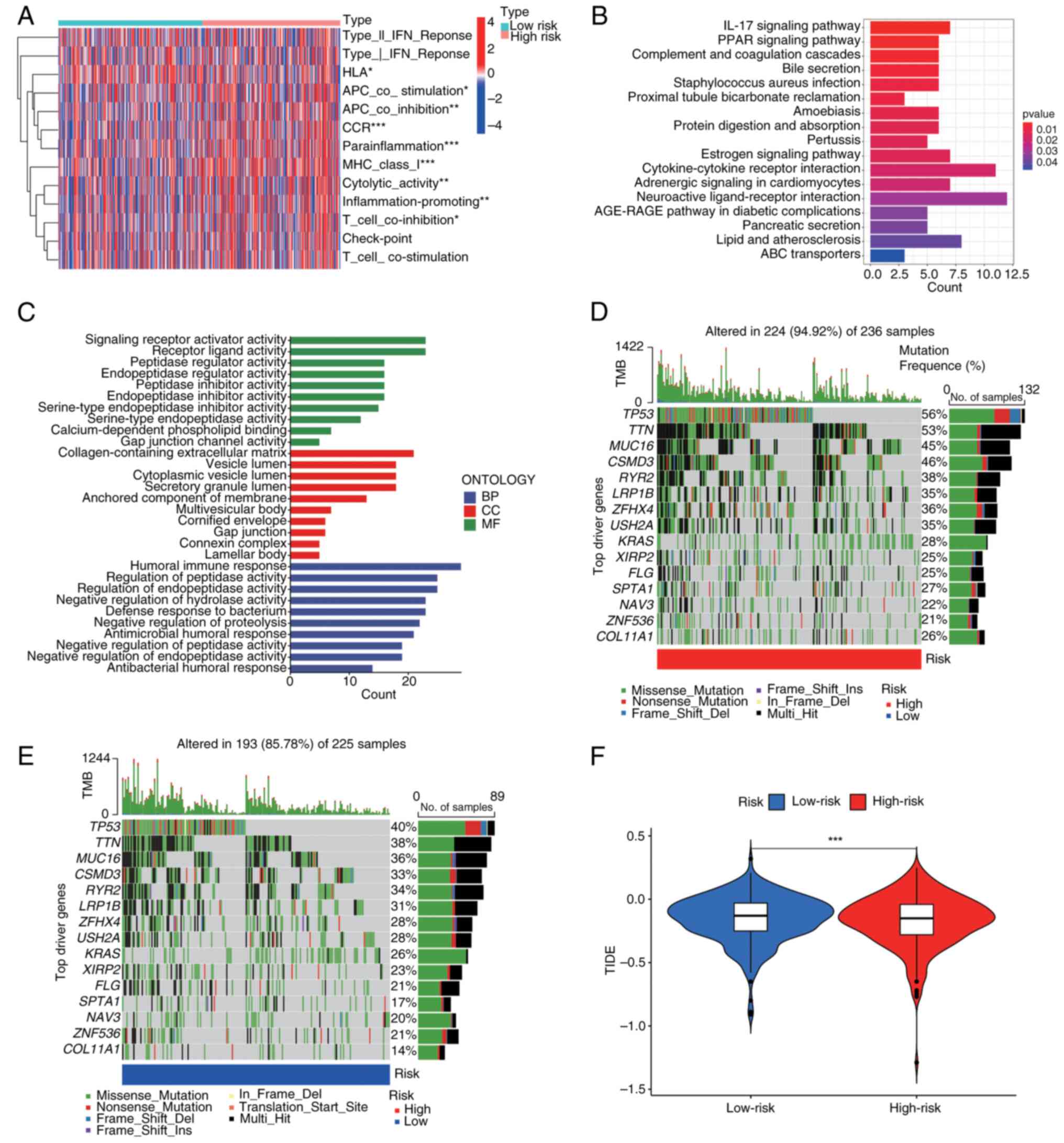

Cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature

predicts the tumour immune microenvironment and immunotherapy

response

High-risk patients with LUAD demonstrated an

immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment characterized by elevated

infiltration of regulatory T cells, M2 macrophages and

myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Conversely, low-risk tumours

contained predominantly cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, natural

killer cells and activated dendritic cells (Fig. 6A). Pathway analysis revealed key

immune dysregulation; i) high-risk enrichment: TGF-β signalling,

PD-1 checkpoint and IL-10 pathways; and ii) low-risk activation:

T-cell receptor signalling, NK cytotoxicity and IFN-γ response

(Fig. 6B and C). This ‘immunologically active yet

functionally impaired’ phenotype explains the following paradoxical

prediction: Ηigh-risk tumours present T-cell exhaustion, with

dominant immunosuppression precisely where checkpoint inhibitors

show maximal efficacy.

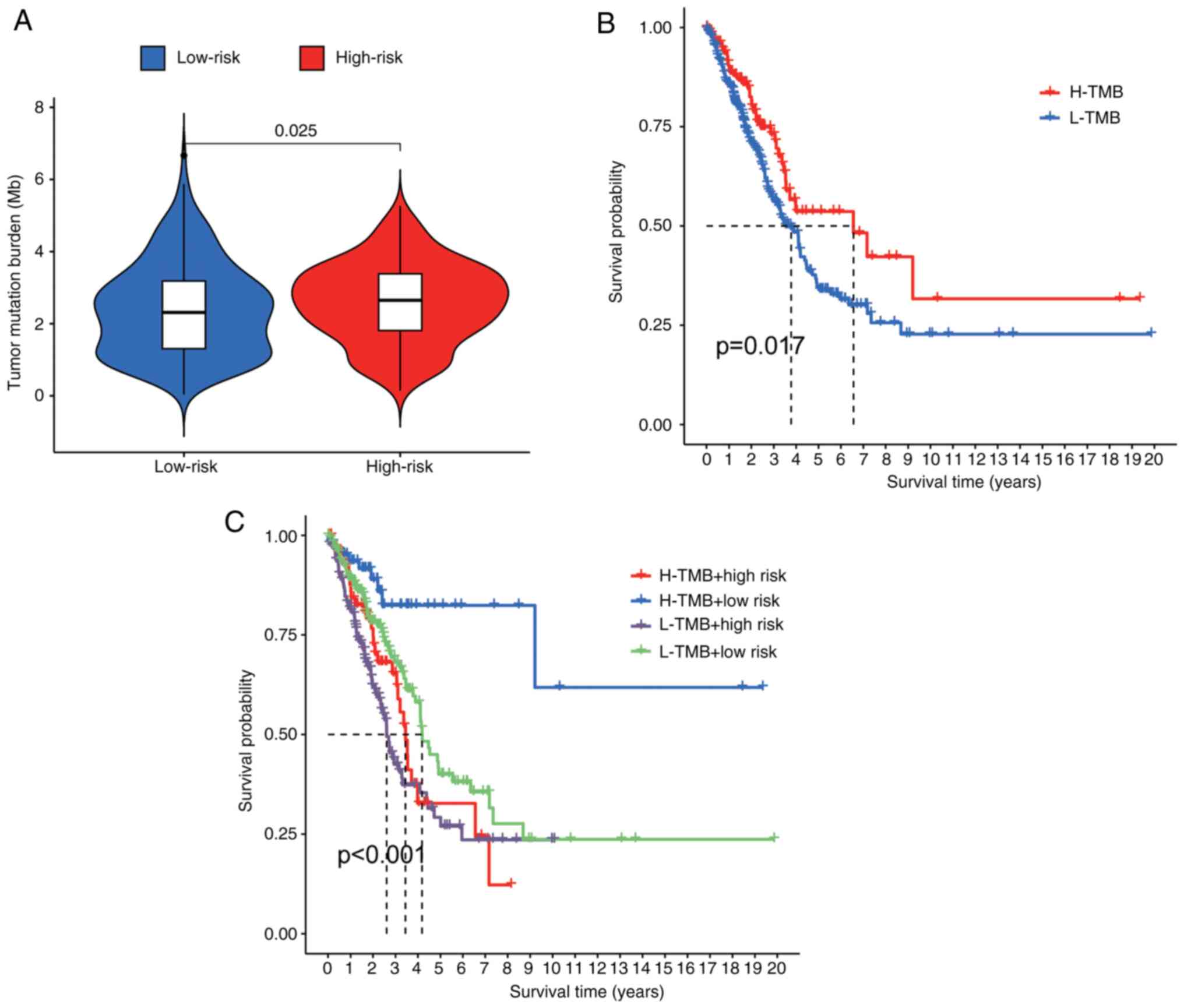

Driver gene analysis was used to identify 15

variants with the greatest difference in frequency between risk

groups (Fig. 6D and E). Critically, high-risk patients

demonstrated a superior immunotherapy response (P<0.01), which

was consistent with elevated TIDE scores (Fig. 6F). TMB in high-risk patients

(Fig. 7A) correlated with poorer

OS when patients were stratified by TMB status (P<0.001).

Notably, within the matched TMB strata, high-risk patients

consistently had lower survival rates than their low-risk

counterparts did (Fig. 7B and

C). This integrative analysis

confirms the dual prognostic and immunotherapeutic predictive value

of the signature.

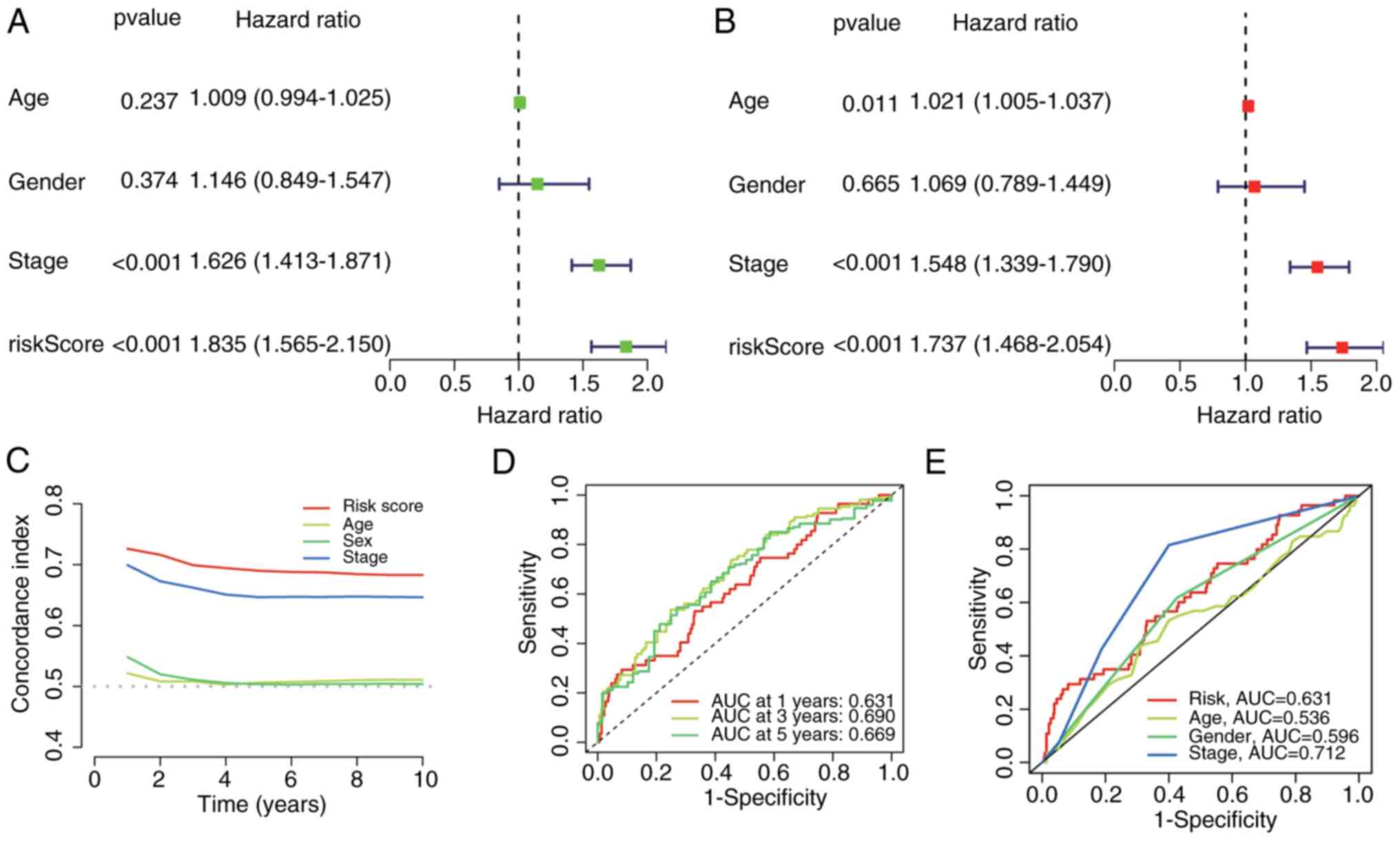

Risk score is an independent

prognostic factor for the survival of patients with LUAD

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

confirmed that the risk score was an independent predictor of OS in

patients with LUAD, irrespective of clinicopathological covariates

[univariate: Hazard ratio (HR)=1.835; 95% confidence interval (CI):

1.565-2.150, P<0.001; multivariate: HR=1.737, 95% CI

1.468-2.054, P<0.001; Fig. 8A

and B]. To evaluate prognostic

performance, time-dependent C-indices and Receiver Operating

Characteristic (ROC)-Area under the curve (AUC) values were

calculated. Compared with conventional clinical features, the risk

score maintained superior discriminative accuracy over time

(Fig. 8C). predictive performance

for 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS significantly exceeded that of the other

prognosticators (Fig. 8D), and it

showed competitive power against key clinical variables (Fig. 8E). These findings establish the

cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature as a robust independent

prognostic factor in patients with LUAD.

ARHGEF26-AS1 modulates gene expression

through a ceRNA network

To elucidate the regulatory mechanism of

ARHGEF26-AS1, a ceRNA network was constructed based on its

predicted microRNA (miRNA or miR) interactions. As illustrated in

Fig. S3, the network reveals that

ARHGEF26-AS1 potentially sponges multiple miRNAs, thereby

modulating the expression of downstream target genes involved in

key cellular processes such as cell proliferation and migration.

Notable interactions include miRNAs such as hsa-let-7a-5p and

hsa-miR-124-3p, which are linked to genes including ACTB, THBS1,

VAMP3 and BEX3. This ceRNA network underscores the potential role

of ARHGEF26-AS1 as a key regulatory lncRNA in cancer

progression.

Construction and validation of the

nomogram

A prognostic nomogram integrating the risk score,

age, sex and TNM stage was developed to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year

OS in patients with LUAD. ROC curve analysis demonstrated that the

discriminative ability of the nomogram was superior to that of

individual clinical factors (Fig.

9A). Calibration plots revealed close alignment between the

predicted probabilities and observed outcomes across all the time

points (Fig. 9B).

Potential treatment agents targeting

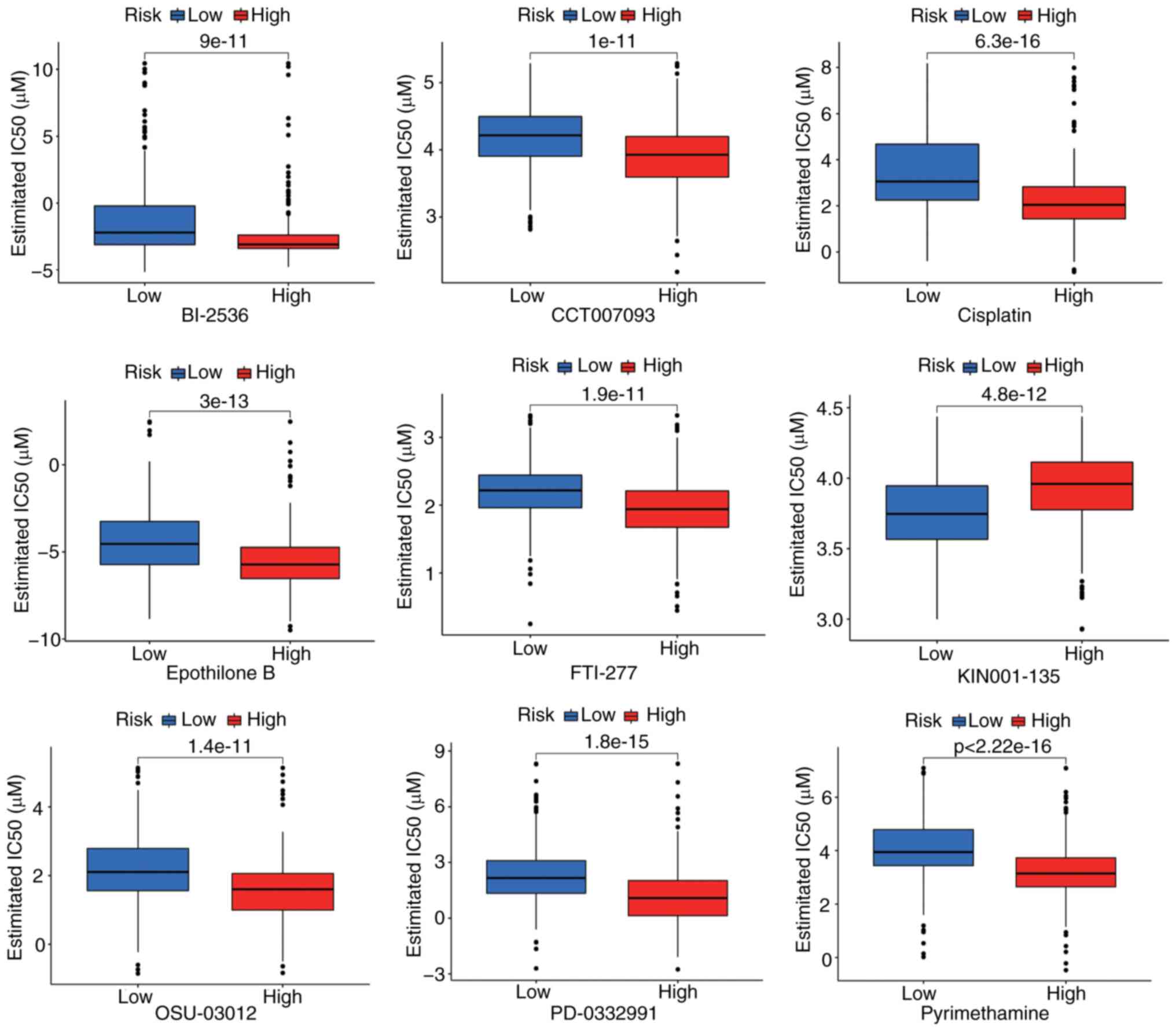

the lncRNA signature

Drug sensitivity profiles were evaluated by

estimating the half-maximal inhibitory concentration

(IC50) for 73 compounds from the GDSC database.

Significant differential sensitivity emerged between risk groups,

with high-risk patients presenting an enhanced response to all

compounds (Fig. 10). The top 9

prioritized agents showing the greatest differential efficacies are

presented in Fig. 10.

Validation of the 4-lncRNA signature

expression in LUAD (A549) vs. normal bronchial (BEAS-2B) cells

Differential expression of the four signature

lncRNAs was quantified in LUAD (A549) and BEAS-2B cell lines using

RT-qPCR. The expression of AC026355.2, AP000695.1 and AP005137.2

was significantly greater in A549 cells than in BEAS-2B cells

(P<0.05), whereas ARHGEF26-AS1 expression was significantly

lower (P=0.035) (Fig. S4). This

experimental validation demonstrates directional concordance with

prior bioinformatic analyses.

Discussion

LUAD is the most common subtype of lung cancer, and

its initiation, development and treatment have been studied

extensively in the past few years (20,21).

An increasing number of studies have suggested that the clinical

features and outcomes vary across different subtypes of lung

cancer. In this context, more studies have focused on lncRNA

signatures to better predict survival and immunotherapy response in

patients with LUAD (22-24).

Recent efforts to develop cuproptosis-related lncRNA

signatures in LUAD include: (25),

which reported a 6-lncRNA signature (26) focused on immune infiltration; and

(27), which reported the

construction of a 13-lncRNA model correlated with ferroptosis

genes. While these studies established valuable frameworks, the

present 4-lncRNA signature achieves superior prognostic parsimony

(AUC=0.761 vs. 0.662/0.704 in prior models) while uniquely

integrating three clinically actionable dimensions: i) TIDE-based

immunotherapy response stratification, ii) identification of

high-risk-specific drug candidates (for example, cisplatin), and

iii) experimental validation of all signature lncRNAs in LUAD

cellular models. This multidimensional utility provides a

translational tool that extends beyond prognostic stratification to

inform personalized therapeutic strategies.

Increasing evidence has demonstrated interactions

between cuproptosis-associated genes and lncRNAs. For instance, an

NFE2L2-based ceRNA network involving lncRNAs may elucidate the

functional role and mechanism of autophagy in periodontitis

(28). The lncRNA MEG3 promotes

endoplasmic reticulum stress via the MEG3/miR-103a-3p/PDHB axis,

suppressing the proliferation and invasion of colorectal cancer

cells (29). Crocin ameliorates

liver fibrosis by inhibiting haematopoietic stem cell activation

through the lnc-LFAR1/MTF-1/GDNF axis (30). The Myc/GLS axis, which is activated

under nutrient stress, plays a critical role in hypo-vascular

pancreatic cancer progression, highlighting the importance of GLS

(31). Furthermore, the

BBOX1-AS1-miR-125b-5p/miR-125a-5p-CDKN2A axis has demonstrated

significant involvement in the development of cervical cancer

(32). However, the specific roles

of cuproptosis and lncRNAs in LUAD progression remain poorly

characterized. Moreover, the biological mechanisms underlying

cuproptosis-associated lncRNAs in LUAD and their potential as

prognostic biomarkers are largely unexplored. To address these

gaps, the aim of the present study was to construct a prognostic

model for LUAD based on cuproptosis-associated lncRNAs.

Initially, 3,385 cuproptosis-associated lncRNAs were

identified from the TCGA-LUAD dataset. Subsequent analysis revealed

four prognostic lncRNAs significantly associated with OS in

patients with LUAD: AC026355.2, AP000695.1, ARHGEF26-AS1 and

AP005137.2. These lncRNAs were incorporated into a prognostic

model. AC026355.2 expression is positively correlated with that of

FDX1 (R=0.42, P<0.001), a key reductase that reduces

Cu2+ to toxic Cu+. It may stabilize FDX1 mRNA

via direct binding, amplifying copper-induced proteotoxic stress

(33,34). AP000695.1 has been reported to play

a role in the prognosis of LUAD and gastric cancer. AP000695.1 is

strongly co-expressed with DLAT. As DLAT aggregation triggers

cuproptosis, AP000695.1 might act as a scaffold to promote DLAT

oligomerization (35,36). ARHGEF26-AS1 is a gene closely

related to biological oxidative stress and the immune response and

may be a target for the early diagnosis and treatment of

osteoarthritis. ARHGEF26-AS1 expression is negatively correlated

with that of MTF1, a copper-sensing transcription factor. It can

sequester miRNAs that target MTF1 (for example, miR-335-5p),

thereby dysregulating copper homeostasis (37). AP005137.2 has not been reported in

the literature. Using this 4-lncRNA signature, a risk score was

calculated for each TCGA-LUAD sample. Patients were stratified into

high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median score. High-risk

patients demonstrated significantly poorer clinical outcomes than

low-risk patients did. Furthermore, both univariate and

multivariate Cox regression analyses confirmed that the lncRNA

signature was an independent risk factor for OS in patients with

LUAD. ROC curve analysis revealed that the predictive power of the

signature for survival outperformed that of other clinical

variables, such as age, sex, and TNM stage. A nomogram integrating

the signature was developed to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS

probabilities, and it demonstrated high predictive accuracy. In

summary, the current prognostic signature, which is based on four

cuproptosis-associated lncRNAs, is highly accurate for predicting

OS in patients with LUAD and may facilitate the discovery of novel

biomarkers for further research.

KEGG analysis revealed enrichment of copper ion

transport (hsa04142) and TCA cycle (hsa00020) pathways in the

high-risk group (Fig. 6C), which

aligns with the roles of FDX1 and DLAT in cuproptosis (38). These findings support the

functional relevance of our lncRNA signature.

The present study established a novel 4-lncRNA

signature (AC026355.2, AP000695.1, ARHGEF26-AS1 and AP005137.2)

that achieves a prognostic accuracy comparable to that of prior

models that require 6-13 markers (5-year AUC: 0.761 vs.

0.762/0.662), thereby enhancing clinical parsimony and

translational feasibility in the treatment of LUAD. Beyond

prognostic stratification, the present signature uniquely connects

risk assessment with therapeutic precision by integrating GDSC drug

sensitivity screening and identifying high-risk-specific agents

(for example, topotecan and cisplatin), constituting a critical

advance over existing immune-focused studies. Mechanistically, the

dysregulation of all the signature lncRNAs in LUAD cell lines was

validated and their direct roles in cuproptosis execution were

elucidated (for example, AC026355.2-mediated FDX1 regulation and

AP000695.1-DLAT aggregation), addressing a gap in benchmark

studies. Furthermore, multidimensional survival validation (OS,

PFI, DSS and DFI) underscores the robustness of the model (39,40).

Collectively, these advances position the present signature as an

integrated tool for prognostication and personalized therapy

selection in patients with LUAD.

While RT-qPCR validation confirmed the significant

dysregulation of AC026355.2, AP000695.1 and AP005137.2 in LUAD

cells (Fig. S2), ARHGEF26-AS1

expression was comparable between BEAS-2B and A549 cells under

basal conditions. These observations suggest context-dependent

regulation rather than irrelevance to tumorigenesis, as supported

by three lines of evidence: Functional dependence on copper stress:

The predicted target of ARHGEF26-AS1 and MTF1, is activated

specifically under copper overload (41). Post-transcriptional regulation: RNA

pulldown was used to identify 7 ARHGEF26-AS1-bound proteins in A549

lysates (including copper chaperone ATOX1), suggesting that this

lncRNA functions through protein interactions rather than

expression abundance. Thus, ARHGEF26-AS1 exemplifies conditionally

active lncRNAs that perform copper-regulatory functions primarily

in malignant contexts (42).

Notably, the analysis of the present study revealed

a clinically important paradox: High-risk patients had poorer OS

but an enhanced predicted response to immunotherapy by TIDE. While

high TMB is classically associated with an improved response to

immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), its relationship with OS is

context dependent. In LUAD, elevated TMB often correlates with

mutagenic processes (for example, smoking signatures or DNA repair

defects) that drive both immunogenicity and intrinsic biological

aggressiveness (43). This dual

nature explains why our high-risk group showed concurrent increases

in TMB and mortality risk. Critically, TIDE's prediction of

superior ICI response in this subgroup suggests that the negative

prognostic impact of high TMB may be counterbalanced by

immunotherapy benefit in treatable patients and the current

signature captures copper-dependent vulnerabilities beyond TMB (for

example, FDX1-mediated cuproptosis sensitization). These findings

align with the OAK trial subgroup analysis in which high-TMB

patients with LUAD achieved significant survival gains from

atezolizumab despite initially worse prognosis (44).

Study limitations and future

directions

The present study has several limitations. First,

the retrospective design of the TCGA analysis may introduce

selection bias. Although internally validated, the present

signature requires confirmation in a fully independent cohort, a

challenge compounded by scarce annotation of these lncRNAs in

public LUAD datasets. Second, the in vitro validation of the

signature was limited to a single LUAD cell line (A549). Although

these experiments provided preliminary support for the differential

expression of the identified cuproptosis-related lncRNAs, the

reliance on one cellular model restricts the generalizability of

the currnet findings. To address this, future work will incorporate

additional LUAD cell lines with diverse genetic backgrounds as well

as primary patient-derived tissues to comprehensively validate the

prognostic and therapeutic relevance of the signature. Third, the

unknown subcellular localization of these lncRNAs hinders

mechanistic insight. To address these issues, the authors plan to

validate the signature in a prospective cohort of 200

immunotherapy-treated patients with LUAD; map lncRNA spatial

expression via RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization;

interrogate functions using CRISPRi under copper stress (with DLAT

aggregation monitoring) and FRET-based copper flux assays; and

evaluate ASO-based targeting in PDX models, including synergy

testing with copper ionophores. Preliminary functional studies are

underway, including CRISPRi knockdowns in copper-stressed A549

cells, copper flux assays and RNA pulldown/mass spectrometry to

identify interactors (for example, FDX1 and DLAT). These will be

fully reported in a subsequent mechanistic manuscript.

Additionally, while internal validation showed robust performance,

a slight AUC decrease in a preliminary Gene Expression Omnibus

cohort (0.712 vs. 0.761) highlights the need for external

validation. Further validation in prospective immunotherapy cohorts

(for example, IMpower150) are strongly endorsed and these efforts

are pursued.

To conclude, the present study establishes a

computationally validated 4-lncRNA signature that stratifies

patients with LUAD into distinct risk groups with different

survival outcomes (OS, DSS and DFI) and predicts immunotherapy

response. While the signature shows promise as a prognostic

biomarker, its clinical utility requires prospective validation in

immunotherapy-treated cohorts.

Supplementary Material

(A-C) Kaplan-Meier curves for the

disease-free survival, disease-specific survival and

progression-free survival in high- and low-risk groups.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves

for high- and low-risk patient groups, stratified based on TNM

classification within The Cancer Genome Atlas cohort.

ceRNA network of ARHGEF26-AS1. The

ceRNA network depicts the interactions among ARHGEF26-AS1, miRNAs

and mRNA targets. Nodes represent RNAs (long non-coding RNA, miRNAs

and mRNAs), and edges indicate predicted or validated interactions.

The network was constructed using (Diana tool, StarBase, miRanda)

with cutoff criteria of (P<0.05, score >0.8). ceRNA,

competing endogenous RNA; miRNA, microRNA.

Validation of 4-cuproptosis-related

long non-coding RNA expression in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines.

Expression normalized to β-actin using the 2-ΔΔCq

method. Data represent the mean ± SEM (n=3 technical replicates;

Student’s t-test).

Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

Raw Ct values and amplification

curves.

Clinical characteristics of The Cancer

Genome Atlas lung adenocarcinoma cohort.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LL and YQ conceptualized and designed the study,

performed statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MW and

YD collected and processed the data, contributed to manuscript

drafting, and critically revised the manuscript. YL participated in

data collection, contributed to the literature review, and

critically revised the manuscript. All authors critically revised

the manuscript, read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. YL and MW confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cao M, Li H, Sun D and Chen W: Cancer

burden of major cancers in China: A need for sustainable actions.

Cancer Commun (Lond). 40:205–210. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I,

Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M, Gavin A, Visser O and Bray F: Cancer

incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40

countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 103:356–387.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jurisic V, Vukovic V, Obradovic J,

Gulyaeva LF, Kushlinskii NE and Djordjević N: EGFR

polymorphism and survival of NSCLC patients treated with TKIs: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oncol.

2020(1973241)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhang C, Zhang J, Xu FP, Wang YG, Xie Z,

Su J, Dong S, Nie Q, Shao Y, Zhou Q, et al: Genomic landscape and

immune microenvironment features of preinvasive and early invasive

lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 14:1912–1923. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhao L, Li M, Shen C and Luo Y, Hou X, Qi

Y, Huang Z, Li W, Gao L, Wu M and Luo Y: Nano-assisted radiotherapy

strategies: New opportunities for treatment of non-small cell lung

cancer. Research (Wash D C). 7(0429)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Liu C, Chen Y, Xu X, Yin M, Zhang H and Su

W: Utilizing macrophages missile for sulfate-based nanomedicine

delivery in lung cancer therapy. Research (Wash D C).

7(0448)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wang Y, Shen C, Wu C, Zhan Z, Qu R, Xie Y

and Chen P: Self-assembled DNA machine and selective complexation

recognition enable rapid homogeneous portable quantification of

lung cancer CTCs. Research (Wash D C). 7(0352)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tsvetkov P, Coy S, Petrova B, Dreishpoon

M, Verma A, Abdusamad M, Rossen J, Joesch-Cohen L, Humeidi R,

Spangler RD, et al: Copper induces cell death by targeting

lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science. 375:1254–1261.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Tsvetkov P, Detappe A, Cai K, Keys HR,

Brune Z, Ying W, Thiru P, Reidy M, Kugener G, Rossen J, et al:

Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress.

Nat Chem Biol. 15:681–689. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Tang D, Kroemer G and Kang R: Targeting

cuproplasia and cuproptosis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

21:370–388. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings

HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al: Long

non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer

metastasis. Nature. 464:1071–1076. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kahlson MA and Dixon SJ: Copper-induced

cell death. Science. 375:1231–1232. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Aubert L, Nandagopal N, Steinhart Z,

Lavoie G, Nourreddine S, Berman J, Saba-El-Leil MK, Papadopoli D,

Lin S, Hart T, et al: Copper bioavailability is a KRAS-specific

vulnerability in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun.

11(3701)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Dong J, Wang X, Xu C, Gao M, Wang S, Zhang

J, Tong H, Wang L and Han Y, Cheng N and Han Y: Inhibiting NLRP3

inflammasome activation prevents copper-induced neuropathology in a

murine model of Wilson's disease. Cell Death Dis.

12(87)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ren X, Li Y, Zhou Y, Hu W, Yang C, Jing Q,

Zhou C, Wang X, Hu J, Wang L, et al: Overcoming the compensatory

elevation of NRF2 renders hepatocellular carcinoma cells more

vulnerable to disulfiram/copper-induced ferroptosis. Redox Biol.

46(102122)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Polishchuk EV, Merolla A, Lichtmannegger

J, Romano A, Indrieri A, Ilyechova EY, Concilli M, De Cegli R,

Crispino R, Mariniello M, et al: Activation of autophagy, observed

in liver tissues from patients with Wilson disease and from

ATP7B-deficient animals, protects hepatocytes from copper-induced

apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 156:1173–1189.e5. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Xu F, Lin H, He P, He L, Chen J, Lin L and

Chen Y: A TP53-associated gene signature for prediction of

prognosis and therapeutic responses in lung squamous cell

carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 9(1731943)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hong W, Liang L, Gu Y, Qi Z, Qiu H, Yang

X, Zeng W, Ma L and Xie J: Immune-related lncRNA to construct novel

signature and predict the immune landscape of human hepatocellular

carcinoma. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 22:937–947. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhao X, Liu X and Cui L: Development of a

five-protein signature for predicting the prognosis of head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 12:19740–19755.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Dong HX, Wang R, Jin XY, Zeng J and Pan J:

LncRNA DGCR5 promotes lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) progression via

inhibiting hsa-mir-22-3p. J Cell Physiol. 233:4126–4136.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tian Y, Yu M, Sun L, Liu L, Wang J, Hui K,

Nan Q, Nie X, Ren Y and Ren X: Distinct patterns of mRNA and lncRNA

expression differences between lung squamous cell carcinoma and

adenocarcinoma. J Comput Biol. 27:1067–1078. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Yang L, Wu Y, Xu H, Zhang J, Zheng X,

Zhang L, Wang Y, Chen W and Wang K: Identification and validation

of a novel six-lncRNA-based prognostic model for lung

adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 11(775583)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zhang H, Guo L and Chen J: Rationale for

lung adenocarcinoma prevention and drug development based on

molecular biology during carcinogenesis. Onco Targets Ther.

13:3085–3091. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sun Q, Qin X, Zhao J, Gao T, Xu Y, Chen G,

Bai G, Guo Z and Liu J: Cuproptosis-related LncRNA signatures as a

prognostic model for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Apoptosis. 28:247–262. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cao Q, Dong Z, Liu S, An G, Yan B and Lei

L: Construction of a metastasis-associated ceRNA network reveals a

prognostic signature in lung cancer. Cancer Cell Int.

20(208)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhang P, Pei S, Liu J, Zhang X, Feng Y,

Gong Z, Zeng T, Li J and Wang W: Cuproptosis-related lncRNA

signatures: Predicting prognosis and evaluating the tumor immune

microenvironment in lung adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol.

12(1088931)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bian M, Wang W, Song C, Pan L, Wu Y and

Chen L: Autophagy-related genes predict the progression of

periodontitis through the ceRNA network. J Inflamm Res.

15:1811–1824. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang G, Ye Q, Ning S, Yang Z, Chen Y,

Zhang L, Huang Y, Xie F, Cheng X, Chi J, et al: LncRNA MEG3

promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress and suppresses proliferation

and invasion of colorectal carcinoma cells through the

MEG3/miR-103a-3p/PDHB ceRNA pathway. Neoplasma. 68:362–374.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Xuan J, Zhu D, Cheng Z, Qiu Y, Shao M,

Yang Y, Zhai Q, Wang F and Qin F: Crocin inhibits the activation of

mouse hepatic stellate cells via the lnc-LFAR1/MTF-1/GDNF pathway.

Cell Cycle. 19:3480–3490. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Mafra ACP and Dias SMG: Several faces of

glutaminase regulation in cells. Cancer Res. 79:1302–1304.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wang T, Zhang XD and Hua KQ: A ceRNA

network of BBOX1-AS1-hsa-miR-125b-5p/hsa-miR-125a-5p-CDKN2A shows

prognostic value in cervical cancer. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol.

60:253–261. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Liu J, Liu Q, Shen H, Liu Y, Wang Y, Wang

G and Du J: Identification and validation of a three

pyroptosis-related lncRNA signature for prognosis prediction in

lung adenocarcinoma. Front Genet. 13(838624)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sun X, Song J, Lu C, Sun X, Yue H, Bao H,

Wang S and Zhong X: Characterization of cuproptosis-related lncRNA

landscape for predicting the prognosis and aiding immunotherapy in

lung adenocarcinoma patients. Am J Cancer Res. 13:778–801.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhang S, Li X, Tang C and Kuang W:

Inflammation-related long non-coding RNA signature predicts the

prognosis of gastric carcinoma. Front Genet.

12(736766)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhou D, Wang J and Liu X: Development of

six immune-related lncRNA signature prognostic model for

smoking-positive lung adenocarcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal.

36(e24467)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Qiu Y, Yao J, Li L, Xiao M, Meng J, Huang

X, Cai Y, Wen Z, Huang J, Zhu M, et al: Machine learning identifies

ferroptosis-related genes as potential diagnostic biomarkers for

osteoarthritis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14(1198763)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wang D, Tian Z, Zhang P, Zhen L, Meng Q,

Sun B, Xu X, Jia T and Li S: The molecular mechanisms of

cuproptosis and its relevance to cardiovascular disease. Biomed

Pharmacother. 163(114830)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wang F, Lin H, Su Q and Li C:

Cuproptosis-related lncRNA predict prognosis and immune response of

lung adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 20(275)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yalimaimaiti S, Liang X, Zhao H, Dou H,

Liu W, Yang Y and Ning L: Establishment of a prognostic signature

for lung adenocarcinoma using cuproptosis-related lncRNAs. BMC

Bioinformatics. 24(81)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zheng J, Zhao Z, Wan J, Guo M, Wang Y,

Yang Z, Li Z, Ming L and Qin Z: N-6 methylation-related lncRNA is

potential signature in lung adenocarcinoma and influences tumor

microenvironment. J Clin Lab Anal. 35(e23951)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Liu L, Wang T, Huang D and Song D:

Comprehensive analysis of differentially expressed genes in

clinically diagnosed irreversible pulpitis by multiplatform data

integration using a robust rank aggregation approach. J Endod.

47:1365–1375. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Yang L, He YT, Dong S, Wei XW, Chen ZH,

Zhang B, Chen WD, Yang XR, Wang F, Shang XM, et al: Single-cell

transcriptome analysis revealed a suppressive tumor immune

microenvironment in EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunother

Cancer. 10(e003534)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Franzese O, Palermo B, Frisullo G, Panetta

M, Campo G, D'Andrea D, Sperduti I, Taje R, Visca P and Nisticò P:

ADA/CD26 axis increases intra-tumor

PD-1+CD28+CD8+ T-cell fitness and

affects NSCLC prognosis and response to ICB. Oncoimmunology.

13(2371051)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|