Introduction

Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death

distinct from necrosis, apoptosis, pyroptosis, and autophagy. It is

characterized by iron-dependent oxidative damage and lipid

peroxidation (1,2). The term ‘ferroptosis’ was first

introduced by Dixon et al (3) in 2012. This form of cell death can be

inhibited by iron chelators such as deferoxamine (DFO) and

radical-trapping antioxidants like ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) and

liproxstatin-1 (Lip-1) (4,5). A key step in the prevention of

ferroptosis is the synthesis of glutathione (GSH), which requires

intracellular cystine uptake via the system χc- on the cell

membrane (6). Consequently,

inhibitors of system χc- such as erastin are well-established

inducers of ferroptosis (3).

Recently, we reported that 2-deoxy-d-ribose (dRib)

also induces ferroptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs)

by increasing the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of

solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), a functional subunit

of system χc- (7). Ferroptosis has

been implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases, including

cancer, ischemia/reperfusion injury, chronic neurodegenerative

diseases, and acute kidney injury (8,9).

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), which affects 20–40%

of patients with diabetes, is the most common cause of end-stage

kidney disease (10). Although

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor

blockers, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors, and

nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists have been shown

to slow the progression of DKD, patients often still develop

chronic kidney disease (CKD) and require dialysis (11,12).

This highlights the urgent need for more effective therapies to

treat DKD. Ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death, has

recently been identified as a key factor in the progression of DKD,

particularly in renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) (13,14).

In patients with DKD, serum ferritin levels are elevated, whereas

the mRNA expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 in kidney tissue is

decreased-a molecular pattern strongly associated with ferroptosis

(15,16). Similarly, in animal models of DKD,

kidney tissues showed increased levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), a

marker of lipid peroxidation, and elevated expression of acyl-CoA

synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), a known ferroptosis

marker (17). Moreover, studies by

Wang et al (18) and Li

et al (19) have

demonstrated clear signs of ferroptosis, such as iron overload and

increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) from lipid peroxidation, in

kidney tissues from streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice and in

RTECs exposed to high glucose levels.

Bardoxolone methyl (BM) is a synthetic triterpenoid

derived from the natural compound oleanolic acid and possesses

antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. The primary mechanism

of BM involves disrupting the interaction between nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and Kelch-like ECH-associated

protein 1 (Keap1), thereby activating the intracellular Nrf2

signaling pathway. This prevents Nrf2 degradation, promotes its

nuclear translocation, and enables it to bind to antioxidant

response elements (ARE) in the promoter regions of target genes,

thereby regulating their expression (20,21).

Genes regulated by the Nrf2-ARE pathway include heme oxygenase-1

(HO-1), NADPH quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), and γ-glutamate

cysteine ligase (GCL) (22). In

addition, SLC7A11, a crucial component in ferroptosis inhibition,

is also regulated by Nrf2 (23).

Clinical studies involving patients with type 2

diabetes and CKD have shown the renoprotective effects of BM. In an

open-label, single-arm study, BM significantly increased estimated

glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline (24), and randomized controlled trials

also showed improvements in eGFR compared to baseline and placebo

groups (25–27). These findings highlight the

potential of BM as a novel therapeutic option for DKD (28).

The aim of our study was to investigate the

protective mechanisms of BM on RTECs in the context of DKD.

Specifically, we attempted to determine how BM inhibits ferroptosis

in RTECs, which contributes to DKD progression. We explored the

ability of BM to preserve RTEC viability and its mechanisms of

action when ferroptosis is induced by dRib-mediated system χc-

disruption. By elucidating the molecular mechanisms through which

BM suppresses ferroptosis in RTECs, our findings provide valuable

insights into the development of novel therapeutic strategies for

DKD.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The NRK-52E cell line, a proximal tubular epithelial

cell line derived from rats, was provided by Prof. Sang-Ho Lee from

Kyung Hee University College of Medicine. The cells were cultured

in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 mg/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml

streptomycin under a 5% CO2 and 95% O2

environment. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium

every 2 days. When the cells reached 70% confluence, they were

subcultured after treatment with trypsin.

To confirm the reproducibility of the experimental

results obtained from NRK-52E cells, primary cultures of rat

proximal tubular epithelial cells were also established and used

for experiments. Sprague Dawley rats (approximately 10 weeks old)

were euthanized using carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation in

accordance with the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal

Care and Use Committee of Jeju National University (protocol no.

2024–0088; approval no. 2022–0014). The animals were placed in a

dedicated sealed chamber, and CO2 was introduced at a

displacement rate of 30% of the chamber volume per minute until the

concentration reached 60–70%. After the concentration was raised,

the chamber was gently shaken up and down to maintain an

appropriate CO2 level. Following euthanasia, death was

confirmed by checking for the cessation of heartbeat, after which

the kidneys were removed. The kidneys were washed with Hanks'

Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), the renal capsule was removed, and

the kidneys were dissected into four pieces, isolating only the

cortical tissue. The HBSS was then removed, and the tissue was

washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The washed tissue

was transferred to a trypsin-treated flask, and 20 ml of a solution

containing DNase I (1 mg/ml) and Collagenase Type I (2 mg/ml) in

HBSS was added. The tissue was then sequentially passed through

sieves of different pore sizes to remove distal tubule and

glomerular cells. The proximal tubule cell suspension in HBSS was

centrifuged at 228 × g (1,000 rpm) for 10 min, and the collected

cells were cultured in rat tail collagen-coated plastic ware. After

1 week, the cells were harvested for intracellular

l-[14C]cystine uptake assays, intracellular GSH content

measurement, and lactate dehydrogenase assays.

Measurement of intracellular cystine

transport

NRK-52E cells (3×105 cells/well) or an

equivalent number of isolated RTECs were seeded into 24-well cell

culture plates and cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS for 2

days. After removing the culture medium, the cells were washed with

500 µl of extracellular fluid (ECF) buffer, pre-warmed to 37°C, and

composed of 122 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 3 mM KCl, 1.4 mM

CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM

K2HPO4, 10 mM d-glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH

7.4). The cells were then stimulated for 4 h with dRib, BM, ML385,

or brusatol. During the final 1 h of stimulation, 500 µl of 37°C

ECF buffer containing 0.1 µCi l-[14C]cystine (1.7 µM)

was added to each well to induce intracellular uptake of

l-[14C]cystine. After incubation, the buffer was

completely removed, and the cells were washed with cold,

radioisotope-free ECF buffer to terminate the uptake process. The

cells were lysed with 750 µl of 1% Triton X-100 in Dulbecco's

phosphate-buffered saline, after which 500 µl of the lysate was

mixed with 5 ml of scintillation cocktail for radioactivity

measurement using the Wallac MicroBeta TriLux 1450 Liquid

Scintillation and Luminescence Counter (PerkinElmer, San Juan, PR,

USA). The remaining cell lysate was used to determine protein

concentration using bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce,

Rockford, IL, USA). Intracellular l-[14C]cystine uptake

was expressed as counts per minute (cpm) per microgram of protein,

normalized to total protein concentration.

Measurement of intracellular GSH

levels

Intracellular GSH levels were measured using a GSH

Assay Kit (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) based on the enzymatic

recycling method using glutathione reductase. Briefly, NRK-52E

cells (3×105 cells/well) or an equivalent number of

isolated RTECs were seeded into 24-well cell culture plates and

cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS for 2 days. The cells

were then stimulated for 6 h with dRib, BM, ML385, or brusatol.

Following treatment, the cells were lysed by sonication, and the

lysates were centrifuged to obtain the supernatant. The GSH

concentration in the supernatant was measured according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Intracellular GSH levels were

normalized to total protein concentration and expressed as nmol/mg

protein.

Measurement of intracellular iron

levels

Intracellular iron levels were measured using the

Iron Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), a colorimetric

assay. NRK-52E cells were seeded at a density of 1×106

cells/well in a six-well culture plate and maintained in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were treated simultaneously

with dRib, BM, ML385, or brusatol and incubated for 6 h.

Subsequently, the cells were lysed using sonication, and the

supernatant was collected after centrifugation. Total iron levels

were measured according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Intracellular iron levels were normalized to the total protein

concentration of the cells and expressed as nmol/mg·protein.

Assessment of cell viability

Cytotoxicity was first assessed using a lactate

dehydrogenase assay. NRK-52E cells were seeded at a density of

1×105 cells/well in a 96-well cell culture plate,

whereas isolated RTECs were plated at an equal number of cells per

well in the same type of plate. The cells were maintained in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS and treated simultaneously with dRib, BM,

ML385, or brusatol for 6 h. Cytotoxicity was then measured using

the Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), and

calculated using the following formula: (((experimental value -

background control)-(low control - background control))/((high

control - background control)-(low control - background control)))

× 100. Finally, cell viability (% control) was expressed as: Cell

viability (% control)}=100 - cytotoxicity (%).

Measurement of intracellular MDA

levels

We selected MDA as a marker to evaluate

intracellular lipid peroxidation. NRK-52E cells were seeded in a

six-well culture plate at a density of 1×106 cells/well

and cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS for 48 h. The cells

were then stimulated with dRib, BM, ML385, or brusatol

simultaneously for 6 h. Subsequently, MDA levels were measured from

the cell lysate using the EZ-Lipid Peroxidation Assay Kit

(DoGenBio, Seoul, South Korea). The intracellular MDA levels were

normalized to the total protein concentration of the cells and

expressed as nmol/mg·protein.

Assessment of lipid ROS levels

Intracellular lipid peroxide levels were measured

using flow cytometry with C11-BODIPY dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene,

OR, USA). NRK-52E cells were seeded in a six-well culture plate at

a density of 1×106 cells/well and cultured in DMEM

medium containing 10% FBS. The cells were then stimulated

simultaneously with dRib, BM, ML385, or brusatol and incubated for

6 h. During the last 30 min, the cells were treated with 4 µM

C11-BODIPY, followed by harvesting using 0.05% trypsin. The

collected cells were centrifuged, resuspended in PBS, and analyzed

for intracellular lipid ROS levels using a FACScan instrument (BD

Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). A total of 10,000 cells per sample

were analyzed, and the results were expressed as the ratio (fold)

of the mean fluorescence intensity relative to the unstimulated

control group.

RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

All RT-qPCR experiments were performed in accordance

with the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative

Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines (29). Total RNA was extracted from cells

using TRIzol® (Gibco Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription

was performed using 2 µg of RNA with MMLV reverse transcriptase

(MGmed Corporation, Seoul, Korea), oligo (dT)15 primer, dNTP (10

mM), and 40 units/µl RNase inhibitor (MGmed Corporation). RT-qPCR

was conducted using the KAPA SYBR® FAST qPCR Master Mix

(KAPA Biosystems, MA, USA) and an iQTM 5 Multicolor Real-Time PCR

Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Synthesized cDNA was

amplified for 40 cycles at 95°C for 3 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and

72°C for 30 sec, with an initial cycle at 95°C for 1 min, using

specific primers. All primers were custom-synthesized by Bioneer

Corporation (Daejeon, Korea), and their sequences are listed in

Table I. Amplification specificity

was confirmed by melt curve analysis, which showed a single

distinct peak for each primer set. Standard curves generated from

5-fold serial dilutions of cDNA templates were used to determine

amplification efficiency. All primer pairs showed amplification

efficiencies ranging 92–105%, with R2 values of

>0.99. β-actin was used as a reference gene, and its stability

was validated across experimental conditions using NormFinder

analysis. All qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate, and

results represent the mean of three independent biological

replicates.

| Table I.Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. |

Table I.

Primer sequences used for reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Forward primer,

5′-3′ | Reverse primer,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| SLC7A11 |

GACAGTGTGTGCATCCCCTT |

GCATGCATTTCTTGCACAGTTC |

| ACSL4 |

ATATTCGTCACCACTCACA |

AACCTTGCTCATAACATTCTT |

| CHAC1 |

GCCCTGTGGATTTTCGGGTA |

ATCTTGTCGCTGCCCCTATG |

| PTGS2 |

GGGAGTCTGGAACATTGTGAA |

GTGCACATTGTAAGTAGGTGGACT |

| HO-1 |

ACCCCACCAAGTTCAAACAG |

GAGCAGGAAGGCGGTCTTAG |

| NQO1 |

AGAAGCGTCTGGAGACTGTCTGG |

GATCTGGTTGTCGGCTGGAATGG |

| GCLC |

GCACATCTACCACGCAGTCAAGG |

TCAAGAACATCGCCGCCATTCAG |

| GCLM |

CTGGACTCTGTCATCATGGCTTCC |

TCCGAGGTGCCTATAGCAACAATC |

| β-actin |

TCCTGGCCTCACTGTCCAC |

GGGCCGGACTCATCGTACT |

Western blotting (immunoblotting)

Cells were lysed using a lysis buffer, and equal

amounts of protein from each group were separated using 10% sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred

onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated in

Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween and 3% bovine serum

albumin to block non-specific antibody binding. It was then

incubated with primary antibodies specific to Nrf2 (#ab92946,

Abcam), SLC7A11 (#175186, Abcam), ACSL4 (#MA5-42523, Invitrogen),

CHAC1 (#217808, Abcam), and PTGS2 (#12282, Cell Signaling) at 4°C

for 2 h. β-Actin (#A2228, Sigma) was used as a loading control.

Afterward, the membrane was incubated with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit antibody (#PI-1000-1,

Vector Laboratories) or anti-mouse antibody (#PI-2000-1, Vector

Laboratories) for 2 h. Bands were visualized using Western

Lightning™ Plus-Enhanced Chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer).

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

assay

IP was performed using Dynabeads Protein G (#10003D,

Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). NRK-52E cells

were stimulated and cultured under the specified conditions, then

lysed using ultrasonication. After centrifugation, the supernatant

containing the cell lysate was collected. Dynabeads were conjugated

with anti-Nrf2 antibody (#ab92946, Abcam) and anti-rabbit IgG

antibody (#2729s, Cell Signaling) to prepare a bead-antibody

mixture. This mixture was incubated with the cell lysate overnight

at 4°C under rotation. The bead-antibody-antigen complex was washed

four times with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20. Lithium dodecyl

sulfate sample buffer was then added to the beads, followed by

incubation at 92°C for 5 min to elute the immunoprecipitant. The

eluted immunoprecipitant was analyzed and quantified using western

blot using anti-Keap1 and anti-Nrf2 antibodies.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

NRK-52E cells were cultured on coverslips and

divided into three groups: an untreated control group, a group

treated with 50 mM dRib for 6 h, and a group treated with 0.2 µM BM

and 50 mM dRib for 6 h. The cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min and then

permeabilized using a 0.1% Triton X-100 solution. Subsequently,

blocking was performed with 5% bovine serum albumin at room

temperature for 45 min. The cells were then incubated overnight at

4°C with primary antibodies: anti-Nrf2 antibody (1:100, #ab92946,

Abcam) and anti-Keap1 antibody (1:100, #D6B12, Cell Signaling).

After washing, the cells were incubated at room temperature for 1 h

with the secondary antibody, donkey anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 488

(1:300, #ab150073, Abcam). Nuclear counterstaining was performed

using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole at a 1:5,000 dilution. The

stained cells were visualized using a STELLARIS 5 confocal

microscope (Leica, Deerfield, IL, USA). To determine the ratio of

Nrf2 fluorescence expressed in the nucleus and cytoplasm, images

were analyzed using ImageJ software and displayed the values as a

bar graph.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version

14.0; SPSS Inc.), and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Homogeneity of variance was

assessed using Levene's test. When the assumption of equal

variances was met (P>0.05), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post hoc test was used. When the assumption was violated

(P<0.05), Welch's ANOVA followed by Dunnett's T3 post hoc test

was applied. For comparisons between two groups, an unpaired

Student's t-test was used.

Results

BM enhances cystine uptake, GSH

content, and cell viability, while reducing intracellular iron and

lipid peroxidation in dRib-treated RTECs

When NRK-52E cells were stimulated with dRib, there

was a significant, dose-dependent decrease in intracellular cystine

uptake, GSH content, and cell viability. However, co-treatment with

BM significantly prevented these reductions (Fig. 1). Similarly, in primary cultured

rat RTECs, dRib led to decreased cystine uptake, GSH levels and

cell viability. These impairments were effectively restored by BM

treatment (Fig. S1), indicating

its protective effect against dRib-induced cellular damage. This

shows that BM prevents cell death by increasing the intracellular

transport of cystine in RTECs, thereby restoring GSH levels.

Furthermore, intracellular iron levels, a key mediator of

ferroptosis, were increased by dRib but were reduced to control

levels by BM (Fig. 2C). Similarly,

intracellular MDA levels and C11-BODIPY fluorescence, indicators of

lipid peroxidation, were elevated by dRib but were nearly restored

to control levels by BM (Figs. 2D,

2E and S2). Therefore, BM prevents dRib-induced

ferroptosis in RTECs by counteracting the reduction in cystine

uptake.

![Effects of BM treatment on the

dRib-induced decreases in (A) l-[14C]cystine uptake, (B)

intracellular GSH content and (C) cell viability. (A) NRK-52E cells

were co-stimulated with 0, 10, 30 and 50 mM dRib with or without

0.2 µM BM for 4 h in the extracellular fluid buffer containing 1.7

µM l-[14C]cystine (0.1 µCi/ml) at 37°C. The

radioactivity incorporated into the cells was determined by a

liquid scintillation counter. (B and C) The cells were

co-stimulated with 0, 10, 30 and 50 mM dRib with or without 0.2 µM

BM for 6 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS. (B) Intracellular GSH

concentration was measured using a GSH assay kit. (C) Cell

viability was measured by LDH release assay. The data are presented

as the mean ± SD. These experiments were performed thrice, in

triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control and

††P<0.01 vs. dRib alone, as determined by one-way

analysis of variance and Tukey's post-hoc test or Welch's ANOVA

followed by Dunnett's T3 post hoc test, depending on the result of

Levene's test. BM, bardoxolone methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose; GSH,

glutathione; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; DMEM, Dulbecco's Modified

Eagle Medium; FBS, fetal bovine serum; SD, standard deviation.](/article_images/mmr/32/4/mmr-32-04-13632-g00.jpg) | Figure 1.Effects of BM treatment on the

dRib-induced decreases in (A) l-[14C]cystine uptake, (B)

intracellular GSH content and (C) cell viability. (A) NRK-52E cells

were co-stimulated with 0, 10, 30 and 50 mM dRib with or without

0.2 µM BM for 4 h in the extracellular fluid buffer containing 1.7

µM l-[14C]cystine (0.1 µCi/ml) at 37°C. The

radioactivity incorporated into the cells was determined by a

liquid scintillation counter. (B and C) The cells were

co-stimulated with 0, 10, 30 and 50 mM dRib with or without 0.2 µM

BM for 6 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS. (B) Intracellular GSH

concentration was measured using a GSH assay kit. (C) Cell

viability was measured by LDH release assay. The data are presented

as the mean ± SD. These experiments were performed thrice, in

triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control and

††P<0.01 vs. dRib alone, as determined by one-way

analysis of variance and Tukey's post-hoc test or Welch's ANOVA

followed by Dunnett's T3 post hoc test, depending on the result of

Levene's test. BM, bardoxolone methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose; GSH,

glutathione; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; DMEM, Dulbecco's Modified

Eagle Medium; FBS, fetal bovine serum; SD, standard deviation. |

![Effects of ML385 and brusatol on the

protective effects of BM treatment on dRib-induced changes in (A)

l-[14C]cystine uptake, (B) intracellular GSH and (C)

iron contents, (D) intracellular MDA, (E) lipid ROS levels and (F)

cell viability. (A) NRK-52E cells were co-stimulated with 0.2 µM

BM, 100 µM ML385, or 100 µM brusatol and 50 mM dRib for 4 h in the

extracellular fluid buffer containing 1.7 µM

l-[14C]cystine (0.1 µCi/ml) at 37°C. The radioactivity

incorporated into the cells was determined by a liquid

scintillation counter. (B-D and F) NRK-52E cells were co-stimulated

with 0.2 µM BM, 100 µM ML385, or 100 µM brusatol and 50 mM dRib for

6 h in DMEM media containing 10% FBS. The intracellular GSH and

iron levels, intracellular MDA levels, and cell viability were

measured using a GSH assay kit, an iron assay kit, MDA assay kit,

and LDH release assay kit, respectively. These experiments were

performed thrice, in triplicate. (E) Intracellular lipid ROS level

was quantified by flow cytometry using the lipophilic fluorescent

dye C11-BODIPY. Cells were incubated with 4 µM C11-BODIPY during

the final 30 min. Fold control of the mean fluorescence intensity

of experimental groups. This experiment was performed four times.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P<0.01 vs. control;

††P<0.01 vs. 50 mM dRib-alone group;

‡‡P<0.01 vs. 50 mM dRib plus 0.2 µM BM group, as

determined by one way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc

test. BM, bardoxolone methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose; GSH,

glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen

species.](/article_images/mmr/32/4/mmr-32-04-13632-g01.jpg) | Figure 2.Effects of ML385 and brusatol on the

protective effects of BM treatment on dRib-induced changes in (A)

l-[14C]cystine uptake, (B) intracellular GSH and (C)

iron contents, (D) intracellular MDA, (E) lipid ROS levels and (F)

cell viability. (A) NRK-52E cells were co-stimulated with 0.2 µM

BM, 100 µM ML385, or 100 µM brusatol and 50 mM dRib for 4 h in the

extracellular fluid buffer containing 1.7 µM

l-[14C]cystine (0.1 µCi/ml) at 37°C. The radioactivity

incorporated into the cells was determined by a liquid

scintillation counter. (B-D and F) NRK-52E cells were co-stimulated

with 0.2 µM BM, 100 µM ML385, or 100 µM brusatol and 50 mM dRib for

6 h in DMEM media containing 10% FBS. The intracellular GSH and

iron levels, intracellular MDA levels, and cell viability were

measured using a GSH assay kit, an iron assay kit, MDA assay kit,

and LDH release assay kit, respectively. These experiments were

performed thrice, in triplicate. (E) Intracellular lipid ROS level

was quantified by flow cytometry using the lipophilic fluorescent

dye C11-BODIPY. Cells were incubated with 4 µM C11-BODIPY during

the final 30 min. Fold control of the mean fluorescence intensity

of experimental groups. This experiment was performed four times.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P<0.01 vs. control;

††P<0.01 vs. 50 mM dRib-alone group;

‡‡P<0.01 vs. 50 mM dRib plus 0.2 µM BM group, as

determined by one way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc

test. BM, bardoxolone methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose; GSH,

glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen

species. |

Nrf2 inhibitors abolish the

BM-mediated recovery of cystine uptake, GSH content, and cell

viability, while reversing the BM-induced reduction in iron levels

and lipid peroxidation in dRib-treated RTECs

To determine whether the ferroptosis-inhibitory

effect of BM depends on Nrf2 activation, we used the specific Nrf2

inhibitors, ML385 and brusatol. In isolated rat RTECs, ML385 and

brusatol significantly attenuated the effects of BM in restoring

cystine uptake, GSH content, and viability, which were reduced by

dRib (Fig. S1). The same results

were observed in NRK-52E cells (Fig.

2A, B and F). In addition, the ability of BM to suppress

intracellular iron, MDA, and C11-BODIPY fluorescence levels, which

were elevated by dRib, was also counteracted by ML385 and brusatol

(Figs. 2C-E and S2). These findings indicate that the

ferroptosis-inhibitory effect of BM is dependent on Nrf2

activation.

BM increases the expression of SLC7A11

and Nrf2 target genes while reducing the expression of

ferroptosis-related markers

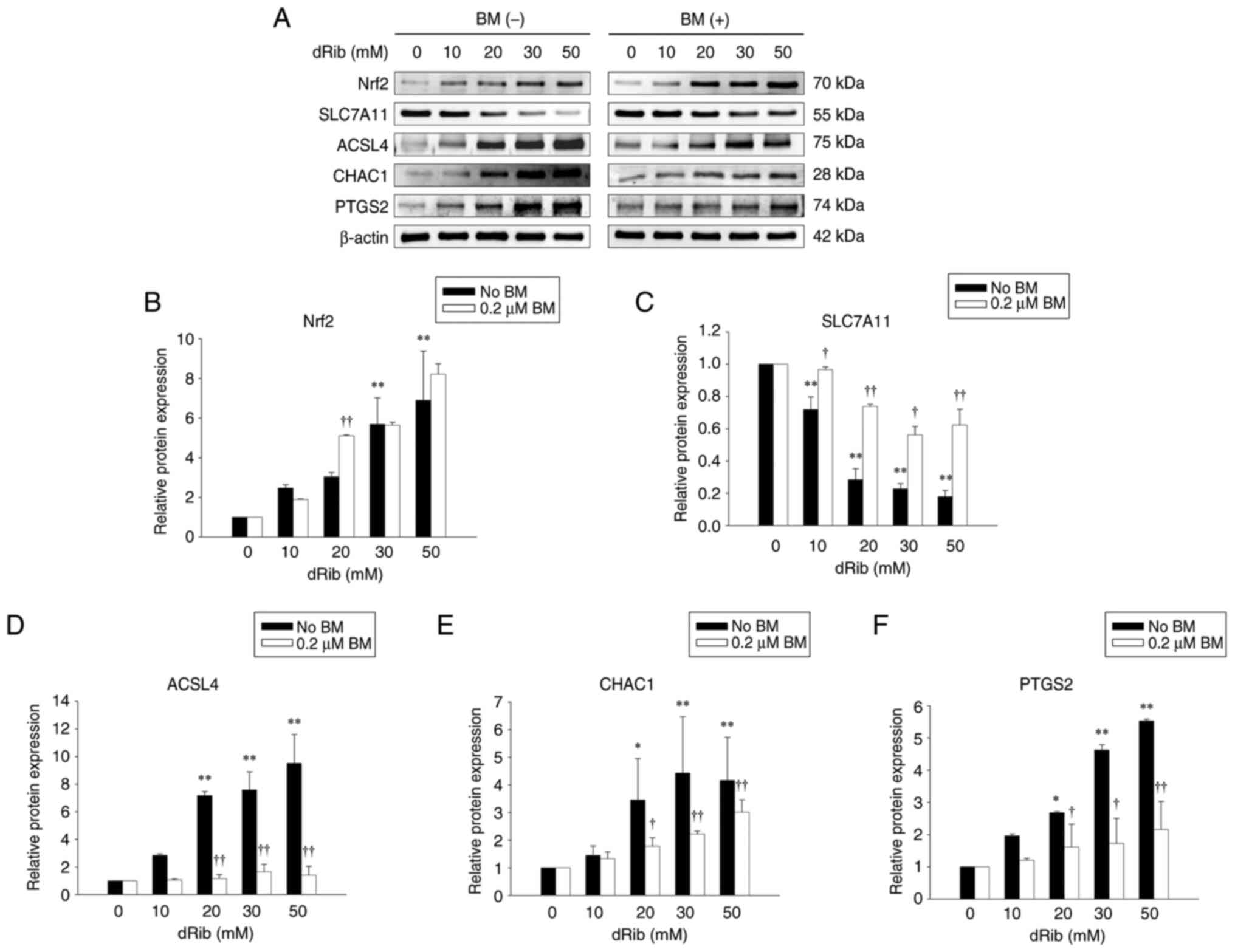

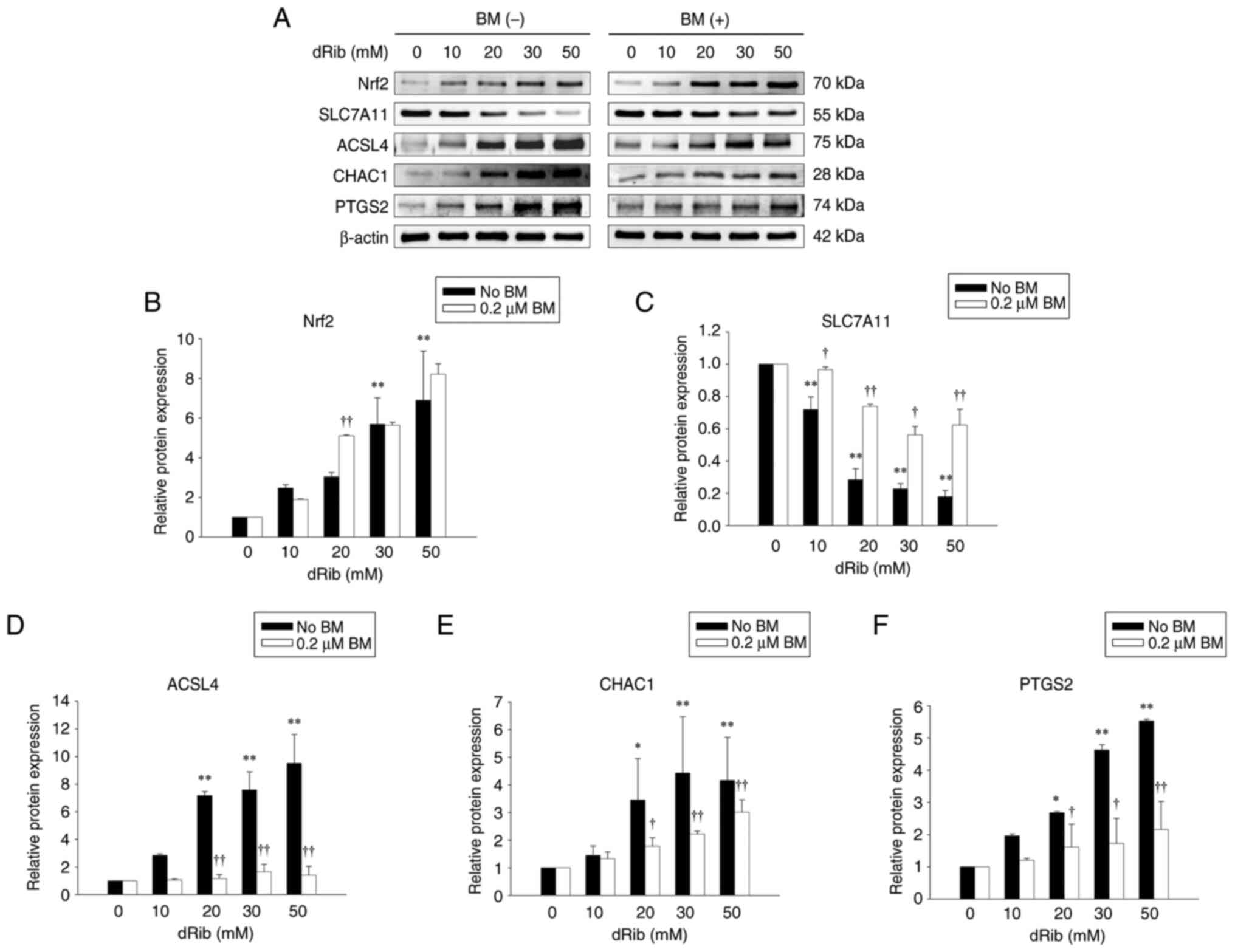

Nrf2 protein expression was increased in a

dose-dependent manner by dRib and was further enhanced by the

addition of BM (Fig. 3A and B).

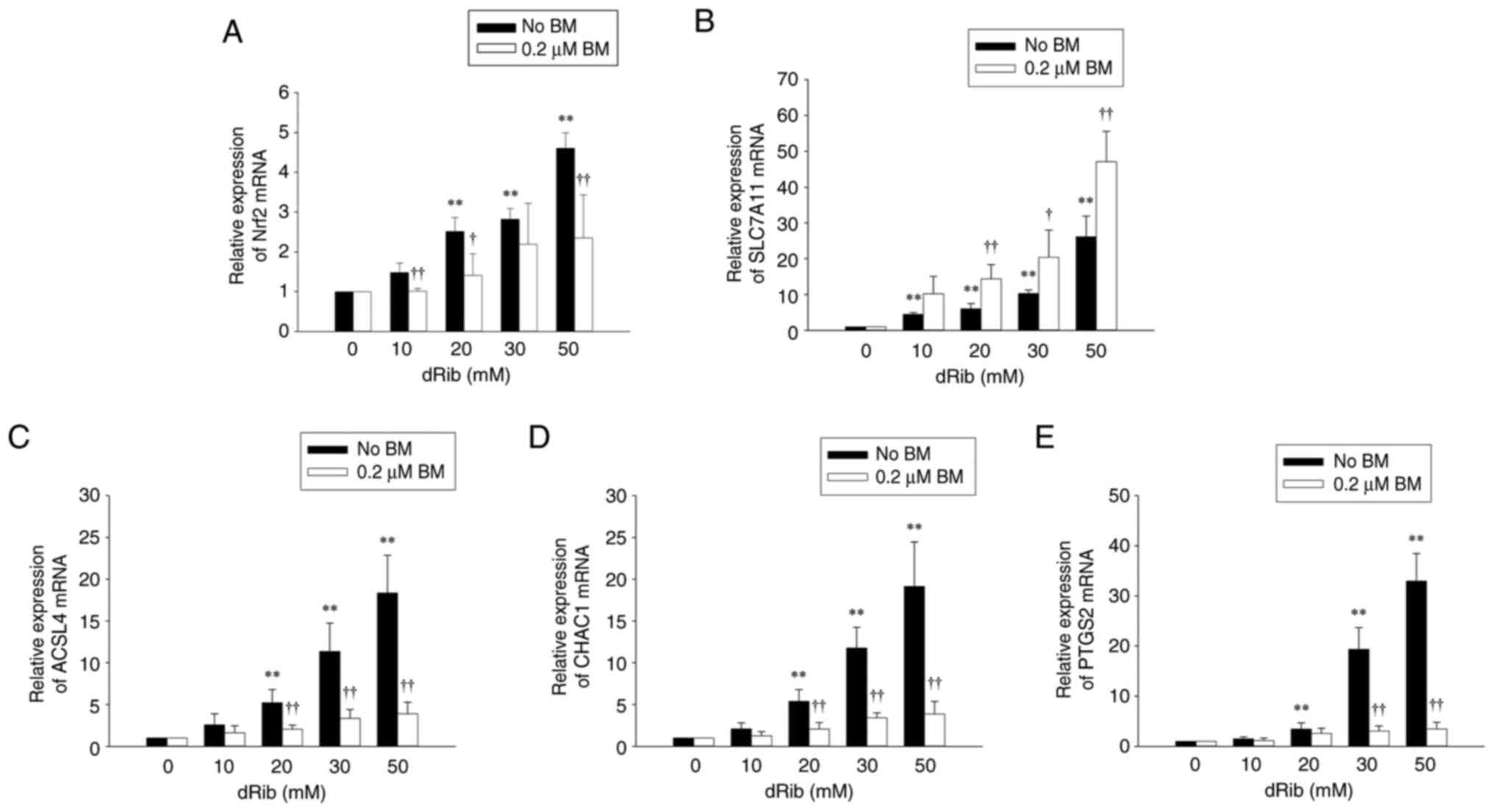

Although Nrf2 mRNA expression was also increased dose-dependently

by dRib, the addition of BM significantly suppressed the

dRib-induced increase (Fig. 4A).

Meanwhile, SLC7A11 protein, which is known to be degraded by dRib

(7), showed a dose-dependent

decrease upon dRib treatment, but this decrease was significantly

prevented by BM (Fig. 3A and

C).

| Figure 3.Effects of BM treatment on

dRib-induced changes in Nrf2, SLC7A11, ACSL4, CHAC1 and PTGS2

protein expressions in NRK-52E cells after treatment with various

concentrations of dRib. The cells were stimulated with 0, 10, 20,

30 or 50 mM dRib with or without 0.2 µM BM for 6 h in DMEM

containing 10% FBS. The protein expression was analyzed by western

blotting. β-Actin was used as loading control. (A) Representative

blots of two independent experiments are shown. Densitometric

quantification of (B) Nrf2, (C) SLC7A11, (D) ACSL4, (E) CHAC1 and

(F) PTGS2 protein levels normalized to β-actin. Data are presented

as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. 0 mM dRib group;

†P<0.05 and ††P<0.01 vs. dRib alone, as

determined by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post-hoc

test or Welch's ANOVA followed by Dunnett's T3 post hoc test,

depending on the result of Levene's test. SLC7A11, solute carrier

family 7 member 11; ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family

member 4; CHAC1, ChaC glutathione-specific

gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1; PTGS2, prostaglandin-endoperoxide

synthase 2; BM, bardoxolone methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose. |

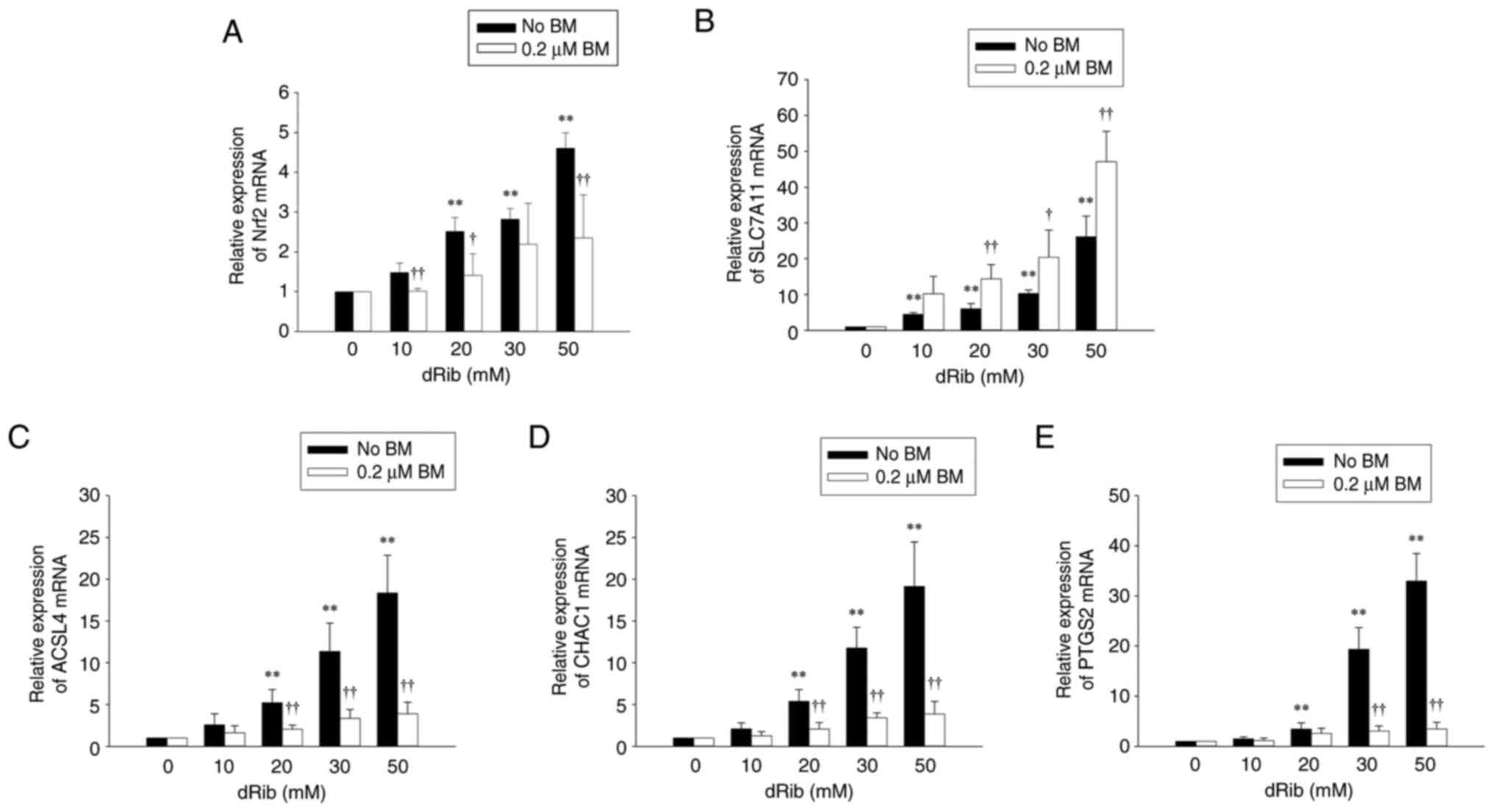

| Figure 4.Effects of BM treatment on

dRib-induced changes in (A) Nrf2, (B) SLC7A11, (C) ACSL4, (D) CHAC1

and (E) PTGS2mRNA expressions. NRK-52E cells were stimulated with

0, 10, 20, 30 or 50 mM dRib for 6 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS. The

mRNA levels were analyzed by reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction. Relative expression of target genes was

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method. This experiment was

performed thrice, in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean ±

SD. **P<0.01 vs. 0 mM dRib group; †P<0.05 and

††P<0.01 vs. dRib alone, as determined by one-way

analysis of variance and Tukey's post-hoc test or Welch's ANOVA

followed by Dunnett's T3 post hoc test, depending on the result of

Levene's test. SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7 member 11; ACSL4,

acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4; CHAC1, ChaC

glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1; PTGS2,

prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2; BM, bardoxolone methyl;

dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose. |

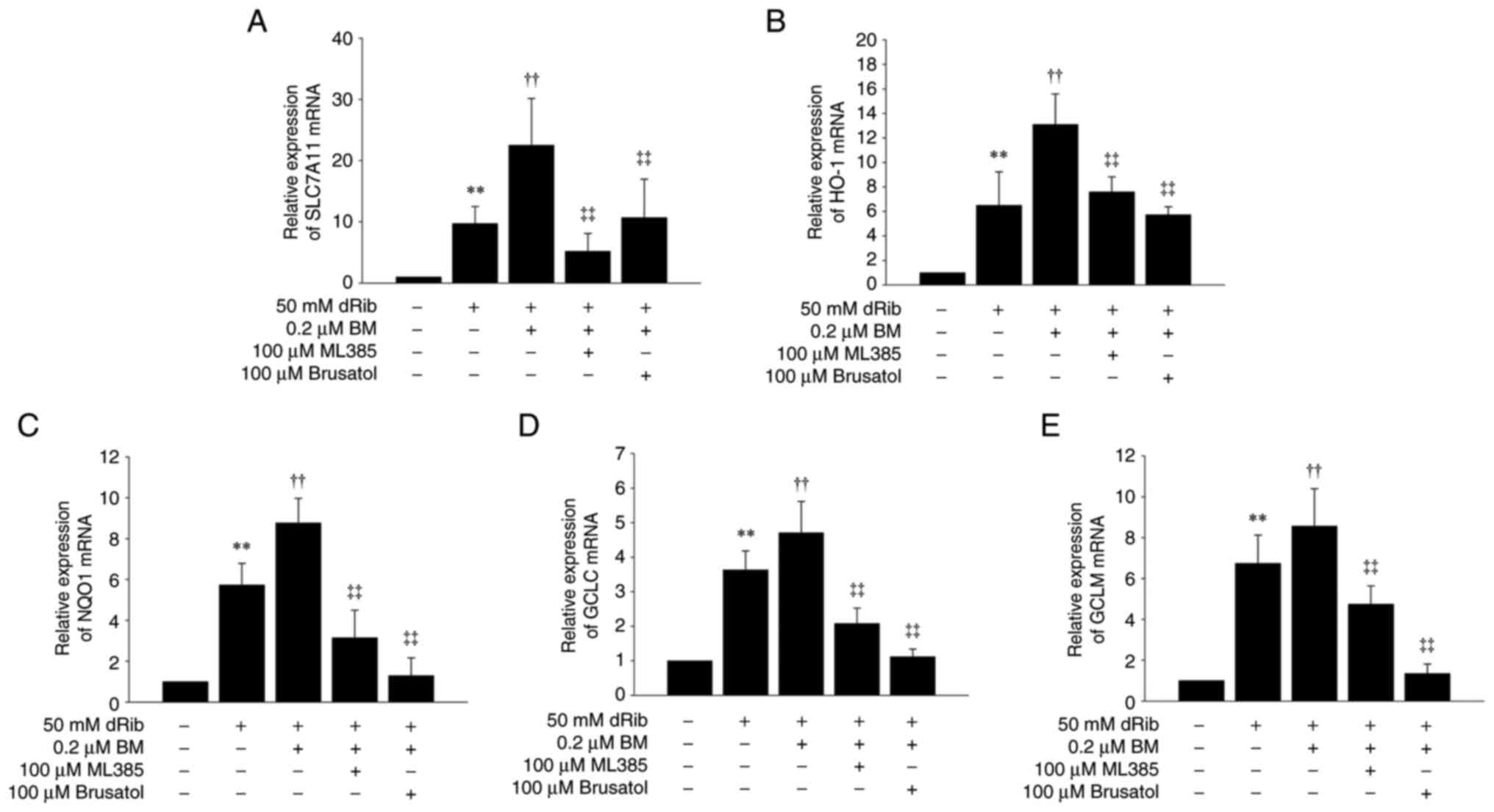

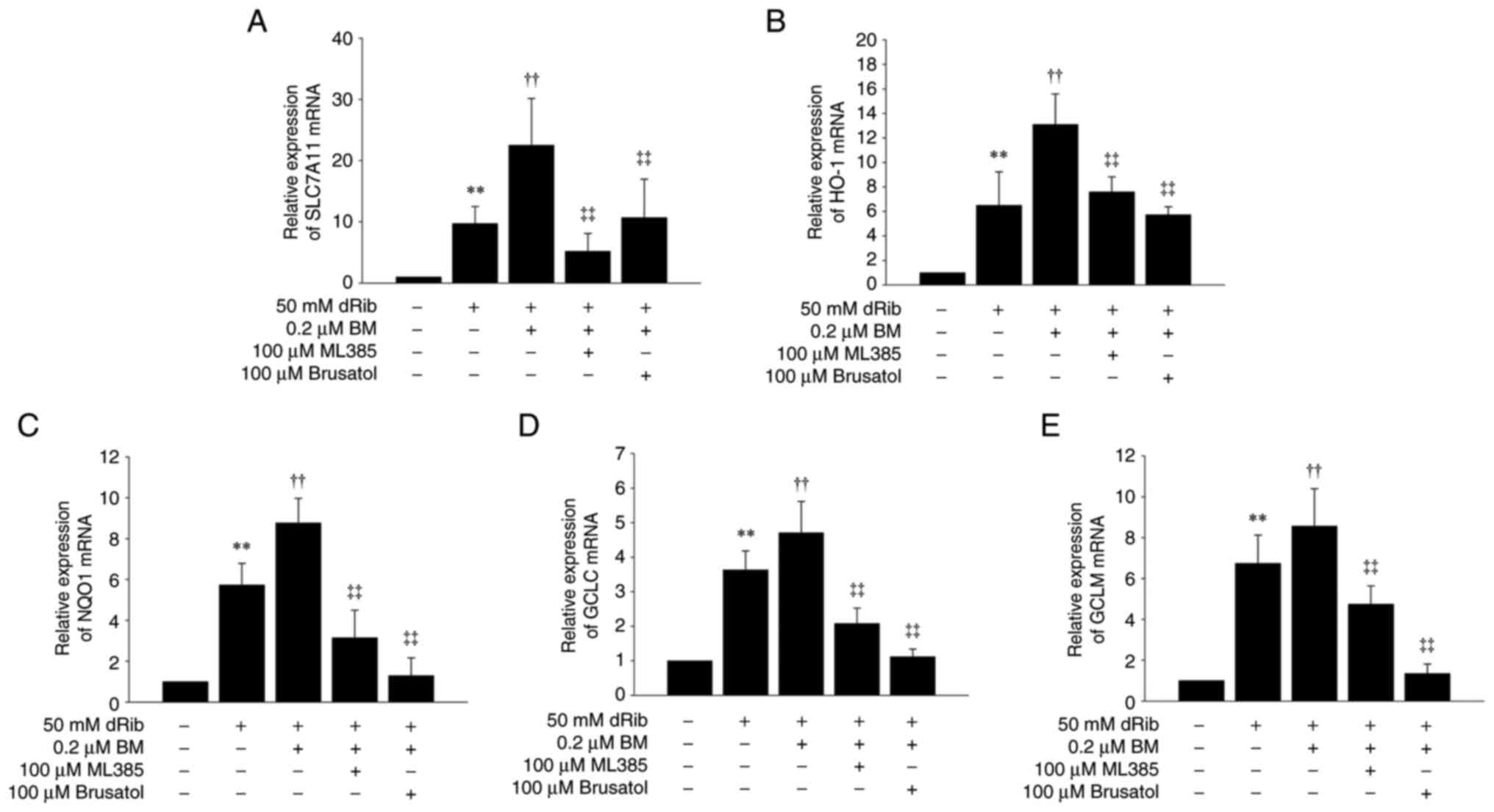

We further examined the expression of Nrf2 target

genes, including SLC7A11, HO-1, NQO1, the catalytic subunit of

glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCLC), and the modifier subunit of

glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCLM). These genes were upregulated by

dRib and showed a further increase upon BM treatment. The

BM-induced increase in these Nrf2 target genes was significantly

attenuated by ML385 and brusatol (Figs. 4B and 5).

| Figure 5.Effects of BM and ML385 or brusatol

treatments on dRib-induced changes in SLC7A11 and Nrf2-antioxidant

response element-dependent genes. NRK-52E cells were co-stimulated

with 0.2 µM BM, 100 µM ML385, or 100 µM brusatol and 50 mM dRib for

6 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS. The mRNA levels of (A) SLC7A11, (B)

HO-1, (C) NQO1, (D) GCLC and (E) GCLM were analyzed by reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Relative

expression of target genes was calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method. This experiment was performed thrice, in

triplicate. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P<0.01 vs.

control; ††P<0.01 vs. 50 mM dRib-alone group;

‡‡P<0.01 vs. 50 mM dRib plus 0.2 µM BM group, as

determined by one way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc

test. BM, bardoxolone methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose; SLC7A11,

solute carrier family 7 member 11; GCLC, glutamate-cysteine ligase

catalytic subunit; GCLM, glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier

subunit; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; NQO1, NADPH quinone oxidoreductase

I. |

Next, we investigated the effect of BM on the

expression of ferroptosis biomarkers. The mRNA and protein levels

of ACSL4, ChaC glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase

1 (CHAC1), and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) were

all significantly increased by dRib in a dose-dependent manner.

However, treatment with BM markedly reduced the expression of these

ferroptosis-related markers (Figs.

3 and 4C-E). These regulatory

effects on SLC7A11, ACSL4, CHAC1, and PTGS2 gene expression were

also consistently observed in primary cultured rat RTECs (Fig. S3). These findings further support

the notion that BM prevents ferroptosis by activating Nrf2

pathway.

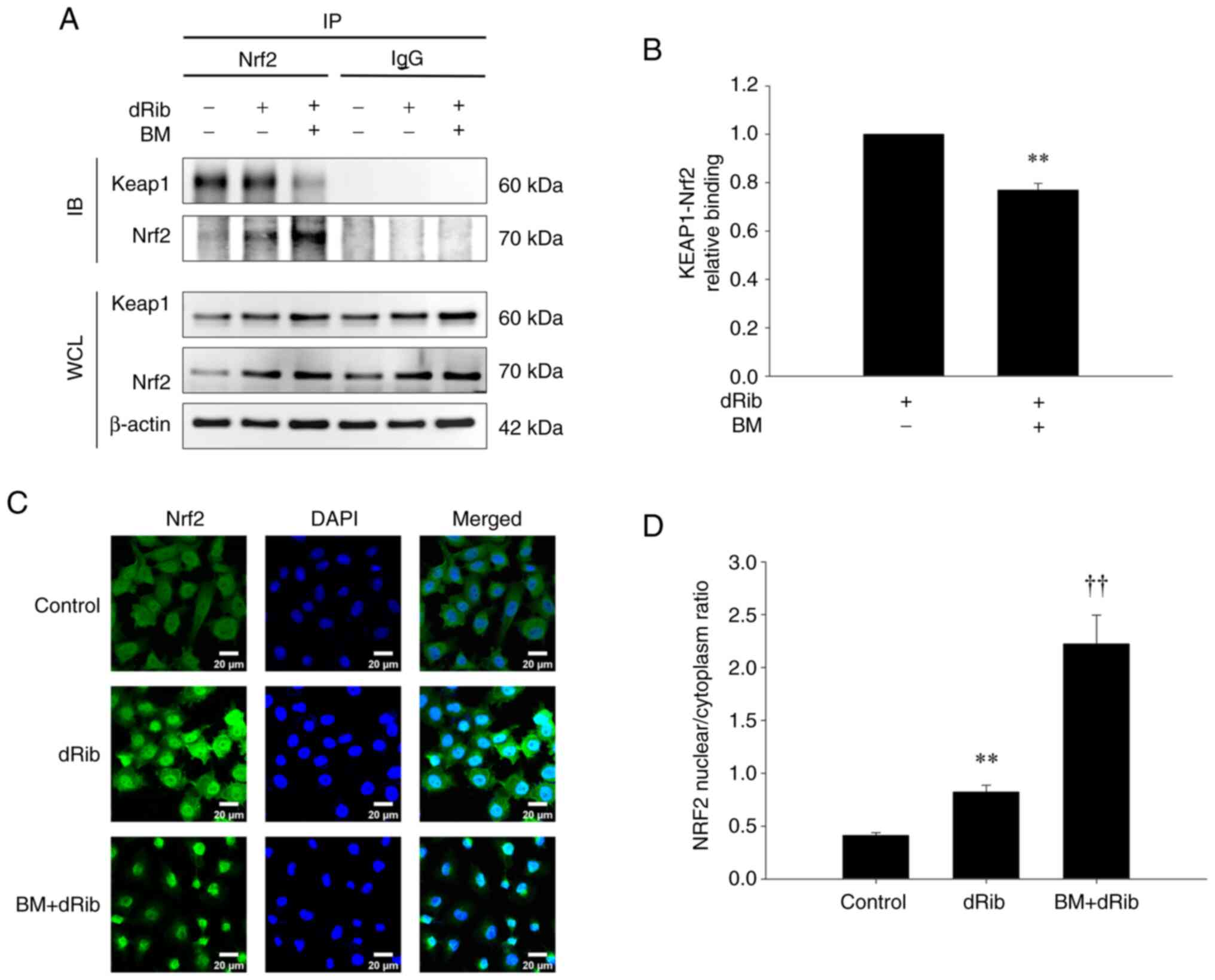

BM disrupts Nrf2-Keap1 interaction and

promotes the nuclear translocation of Nrf2

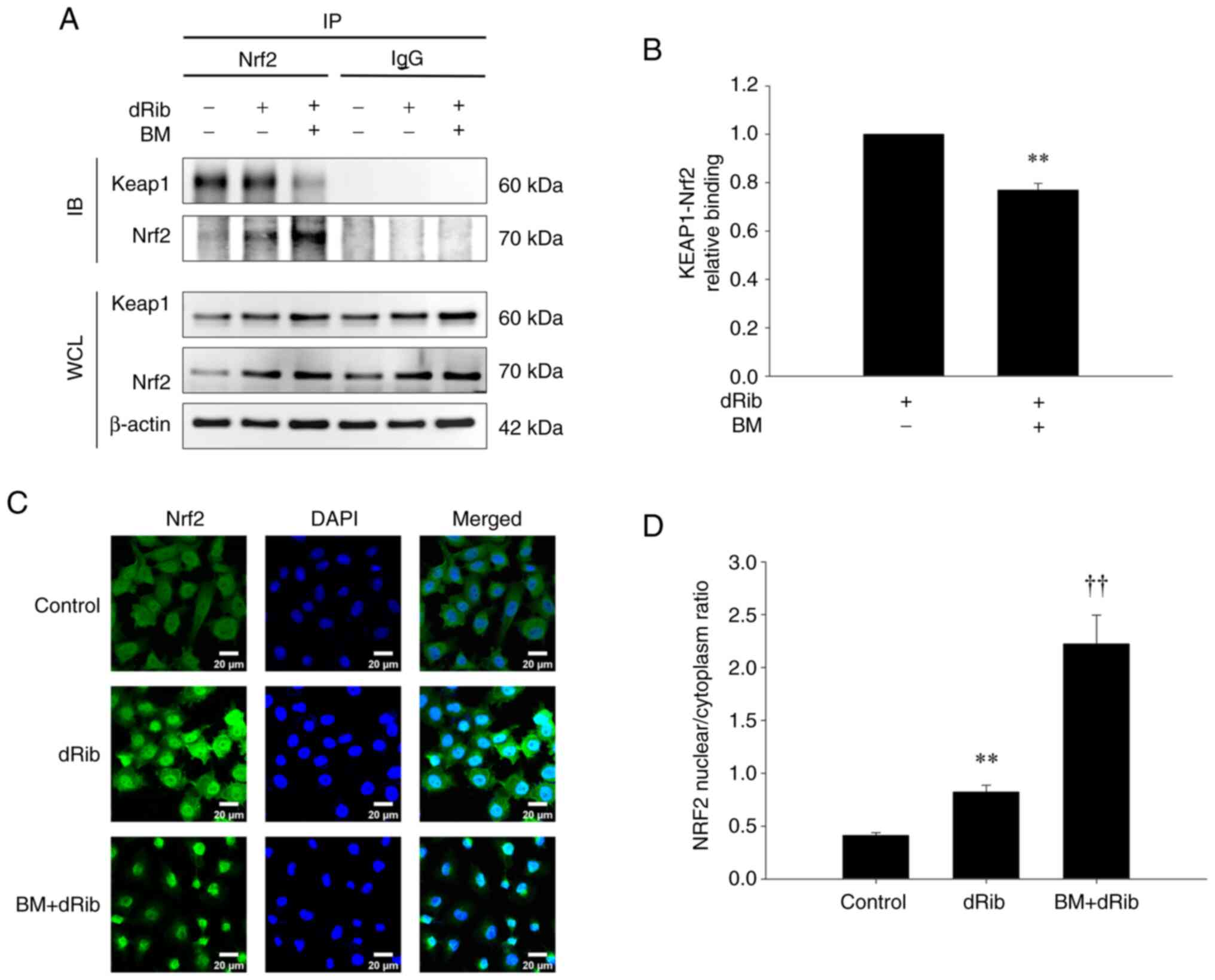

To elucidate the mechanism through which BM

activates the Nrf2 pathway, we investigated the interaction between

Nrf2 and Keap1 and their intracellular localization.

In the co-IP assay assessing their interaction,

Keap1 was pulled down by Nrf2 in both the control and dRib-treated

groups, indicating a physical association. However, when BM was

added, the pull-down of Keap1 by Nrf2 was reduced (Fig. 6A and B). This indicates that

although the physical interaction between Nrf2 and Keap1 remained

intact under dRib treatment alone, the addition of BM weakened

their association, implying that BM disrupts the Nrf2-Keap1

interaction.

| Figure 6.Investigation of Nrf2 and Keap1

interaction and intracellular localization using (A and B) co-IP

and (C and D) immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. (A) NRK-52E

cells were stimulated with 50 mM dRib with or without 0.2 µM BM for

6 h in DMEM media containing 10% FBS. The cell lysates were

immunoprecipitated using an anti-Nrf2 antibody or control

immunoglobulin (IgG), followed by IB with anti-Keap1 and anti-Nrf2

antibodies. The lower panels show IB of WCL. (B) Densitometric

quantification of the immunoprecipitated Keap1 and Nrf2 protein

bands from (A), normalized to IgG controls. Data represent the mean

± SD from three independent experiments. **P<0.01 vs. dRib

alone, as determined by unpaired Student's t-test. (C) Cells were

treated with dRib (50 mM) alone or in combination with BM (0.2 µM)

for 6 h. Representative images from three independent experiments

show Nrf2 (green), Keap1 (red), and DAPI (blue) staining, with

merged images illustrating nuclear translocation of Nrf2 under

different conditions. Scale bar=20 µm. (D) The nuclear/cytoplasmic

ratio of Nrf2 expression was measured using the ImageJ program.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P<0.01 vs. control group;

††P<0.01 vs. dRib alone, as determined by one-way

analysis of variance and Tukey's post-hoc test. BM, bardoxolone

methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose; IB, immunoblotting; IP,

immunoprecipitation; WCL, whole cell lysates. |

To examine changes in the intracellular localization

of Nrf2 and Keap1 upon dRib and BM treatment, we performed IF

staining and observed the cells using confocal microscopy. In the

control group, Nrf2 was evenly distributed between the cytoplasm

and nucleus, whereas in the dRib-treated group, nuclear

translocation of Nrf2 was increased. Notably, in the BM-treated

group, nuclear translocation of Nrf2 was markedly enhanced, with

minimal Nrf2 observed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6C and D). However, Keap1

localization remained unchanged, as it was consistently retained in

the cytoplasm regardless of dRib or BM treatment (Fig. S4). Results from co-IP and confocal

microscopy indicate that BM disrupts the interaction between

Nrf2-Keap1, thereby facilitating the nuclear translocation of

Nrf2.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that BM inhibits

ferroptosis in RTECs by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway and

upregulating SLC7A11 expression. These findings provide further

insight into the renal protective mechanisms of BM in DKD and show

a novel strategy to overcome the clinical limitations of current

DKD treatments.

As ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of

oxidative cell death caused by lipid peroxidation, our finding that

BM lowers intracellular iron levels and lipid peroxidation markers

supports its role in preventing ferroptosis. This is further

confirmed by BM's ability to reduce the expression of ferroptosis

markers such as ACSL4, CHAC1, and PTGS2. ACSL4 promotes lipid

peroxidation by catalyzing the esterification of polyunsaturated

fatty acids (30). CHAC1 increases

during ferroptosis triggered by system χc- inhibitors (31), and PTGS2 is a recognized marker of

ferroptosis (32). BM inhibits

ferroptosis mainly by increasing the expression of SLC7A11, which

is essential for cystine transport through system χc−.

We found that BM raises both the mRNA and protein levels of

SLC7A11, and also enhances cystine uptake and intracellular GSH

levels. Notably, while dRib increased SLC7A11 mRNA expression, it

decreased the protein levels. This matches our earlier work showing

that dRib causes SLC7A11 protein degradation via the

ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (7).

This explains why SLC7A11 mRNA is upregulated as a compensatory

response to reduced cystine uptake, but protein levels drop because

of increased degradation. In contrast, BM activates Nrf2 and

restores SLC7A11 protein levels, counteracting the degradation

caused by dRib. Furthermore, the ferroptosis induced by dRib, which

was prevented by BM, was primarily caused by impaired intracellular

cystine transport (7). BM

upregulates SLC7A11 by activating the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Keap1

normally inhibits Nrf2 activation (33). In our study, BM increased Nrf2

protein expression and promoted its intranuclear translocation by

disrupting the interaction between Nrf2 and Keap1. Although BM does

not directly enhance the transcription of Nrf2, it stabilizes the

Nrf2 protein by interfering with its binding to Keap1, thereby

inhibiting Keap1-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal

degradation of Nrf2 (20). As a

result, Nrf2 accumulates in the cytoplasm and is subsequently

translocated into the nucleus. Therefore, the observed increase in

Nrf2 protein levels following BM treatment is primarily attributed

to post-translational stabilization instead of increased gene

expression. Consequently, the expression of Nrf2 target genes,

including HO-1, NQO1, and GCL, was upregulated. Furthermore, the

ferroptosis-inhibitory effects of BM were abolished by the Nrf2

inhibitors ML385 and brusatol, providing strong evidence that Nrf2

activation is essential for the protective effects of BM.

Meanwhile, Nrf2 mRNA expression was increased by dRib, and this

increase was prevented by the addition of BM. It is well known that

Nrf2 mRNA expression increases in response to oxidative stress

stimuli (34,35). Since BM promotes the stabilization

of Nrf2 protein as described above, there is no need for increased

transcription of Nrf2, and thus the addition of BM is thought to

prevent the dRib-induced increase in Nrf2 mRNA expression.

BM has shown renoprotective effects in clinical

trials involving patients with DKD; however, one trial failed to

confirm these benefits. The BEACON trial, which aimed to verify the

nephroprotective effects of BM in 2,185 patients with type 2

diabetes and reduced eGFR, was terminated early after only 9 months

owing to an increased incidence of heart failure in the BM-treated

group, thus preventing definitive confirmation of its

kidney-protective effects (36).

Subsequent studies conducted in Japanese patients with DKD, such as

the TSUBAKI study (37) and the

AYAME study (27), excluded

patients with risk factors for heart failure. These studies

revealed the nephroprotective effects of BM without significant

adverse events. Therefore, heart failure remains a major obstacle

in the development of BM as a therapeutic agent for DKD. Based on

the results of our present study, a treatment strategy targeting

SLC7A11 rather than BM, which activates Nrf2, may have the

potential to prevent ferroptosis in RTECs while minimizing adverse

effects. Therefore, the development of a novel compound that

selectively upregulates SLC7A11 expression in RTECs could offer a

safer and more effective therapeutic option for DKD. In addition to

approaches targeting SLC7A11, other strategies may help reduce the

cardiovascular risks associated with BM. First, tissue-specific

drug delivery systems that selectively target the kidney can limit

systemic exposure (38), thereby

lowering the risk of off-target side effects such as heart failure.

Second, combining BM with other renoprotective agents may allow for

dose reduction, thereby improving its safety profile (39). Further research is required to

develop structural analogs of BM (21) that retain Nrf2-activating capacity

while reducing cardiotoxicity.

This study has some limitations. First, the

concentration of dRib used in our study is considerably high.

Erastin, a well-known system χc− inhibitor, is typically

used at micromolar concentrations, whereas we used dRib at

concentrations of 10–50 mM. Unlike erastin, dRib is not a small

molecule but rather a reducing sugar. Studies that have used

reducing sugars to induce oxidative stress have consistently

employed high concentrations, and some have even used

concentrations higher than those used in our study (40,41).

Second, it was conducted at the cellular level using NRK-52E cells

and primary cultured RTECs. Therefore, it does not fully replicate

the complex physiological environment of DKD, and further studies

are required to verify whether similar results are observed in

animal models of DKD. Third, instead of using erastin, a widely

used ferroptosis inducer, we induced ferroptosis in RTECs using

dRib. However, both erastin and dRib induce ferroptosis through

cysteine deprivation. Erastin inhibits system χc-, leading to a

compensatory increase in SLC7A11 gene expression. Ferroptosis

induced by erastin is known to be prevented by 2-mercaptoethanol,

which bypasses system χc- to enhance cystine uptake (3). Similarly, dRib increases SLC7A11 gene

expression in RTECs and enables dRib-induced ferroptosis to be

prevented by 2-ME (7). Therefore,

even if erastin had been used as a ferroptosis inducer, we believe

the results would have been the same as those obtained in this

study. Moreover, the reason we used dRib instead of erastin is that

dRib is more suitable for in vitro studies using RTECs.

Erastin does not dissolve well and is difficult to handle (42). In contrast, dRib dissolves readily

in water, induces ferroptosis in RTECs in a dose-dependent manner,

and its detailed mechanisms are well understood (7). For these reasons, we chose to use

dRib in our study on ferroptosis in RTECs. Fourth, further research

on intracellular signaling pathways that may contribute to the

off-target effects of BM is required. Adverse effects of BM, such

as heart failure, remain a major obstacle to its development as a

therapeutic agent for DKD. Thus, elucidating these detailed

mechanisms is as crucial as understanding the renoprotective

mechanisms of BM, as it could contribute to the development of an

optimal DKD treatment.

This study showed that BM inhibits ferroptosis in

renal tubular epithelial cells by activating the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway

and increasing the expression of SLC7A11. BM reversed the

dRib-induced decrease in cystine uptake, GSH depletion,

intracellular iron accumulation, and lipid peroxidation, and these

effects were noted to be dependent on Nrf2 activation. Although BM

appears to be a promising therapeutic strategy for DKD, adverse

effects such as heart failure remain a significant concern. Future

research should focus on developing safer therapeutic agents that

selectively enhance SLC7A11 activity to inhibit ferroptosis.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from Jeju National

University Hospital in 2023.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

GK, SAL and MK conceived and designed the research.

GK, JYB and SY performed experiments. GK and SY analyzed data. GK,

JYB and SY interpreted results of experiments. GK and SAL acquired

funding. GK, JYB and SY confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. GK, JYB and SY prepared figures. GK, SY and MK drafted the

manuscript, and GK edited and revised the manuscript. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Jeju National University (approval

no. 2022-0014).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao

N, Sun B and Wang G: Ferroptosis: Past, present and future. Cell

Death Dis. 11:882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhu J, Xiong Y, Zhang Y, Wen J, Cai N,

Cheng K, Liang H and Zhang W: The molecular mechanisms of

regulating oxidative stress-induced ferroptosis and therapeutic

strategy in tumors. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020:88107852020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yan HF, Zou T, Tuo QZ, Xu S, Li H, Belaidi

AA and Lei P: Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zilka O, Shah R, Li B, Friedmann Angeli

JP, Griesser M, Conrad M and Pratt DA: On the mechanism of

cytoprotection by ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1 and the role of

lipid peroxidation in ferroptotic cell death. ACS Cent Sci.

3:232–243. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dringen R and Hirrlinger J: Glutathione

pathways in the brain. Biol Chem. 384:505–516. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kim M, Bae JY, Yoo S, Kim HW, Lee SA, Kim

ET and Koh G: 2-Deoxy-d-ribose induces ferroptosis in renal tubular

epithelial cells via ubiquitin-proteasome system-mediated xCT

protein degradation. Free Radic Biol Med. 208:384–393. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yao MY, Liu T, Zhang L, Wang MJ, Yang Y

and Gao J: Role of ferroptosis in neurological diseases. Neurosci

Lett. 747:1356142021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru

RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, Collins BS, Hilliard ME, Isaacs D,

Johnson EL, et al: 11. chronic kidney disease and risk management:

standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 46 (Suppl

1):S191–S202. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Barnett AH, Bain SC, Bouter P, Karlberg B,

Madsbad S, Jervell J and Mustonen J; Diabetics Exposed to

Telmisartan and Enalapril Study Group, : Angiotensin-receptor

blockade versus converting-enzyme inhibition in type 2 diabetes and

nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 351:1952–1961. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Solomon J, Festa MC, Chatzizisis YS,

Samanta R, Suri RS and Mavrakanas TA: Sodium-glucose co-transporter

2 inhibitors in patients with chronic kidney disease. Pharmacol

Ther. 242:1083302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang XD and Yang YY: Ferroptosis as a

novel therapeutic target for diabetes and its complications. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:8538222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang X and Li X: Abnormal iron and lipid

metabolism mediated ferroptosis in kidney diseases and its

therapeutic potential. Metabolites. 12:582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kim S, Kang SW, Joo J, Han SH, Shin H, Nam

BY, Park J, Yoo TH, Kim G, Lee P and Park JT: Characterization of

ferroptosis in kidney tubular cell death under diabetic conditions.

Cell Death Dis. 12:1602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mengstie MA, Seid MA, Gebeyehu NA, Adella

GA, Kassie GA, Bayih WA, Gesese MM, Anley DT, Feleke SF, Zemene MA,

et al: Ferroptosis in diabetic nephropathy: Mechanisms and

therapeutic implications. Metabol Open. 18:1002432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang Y, Bi R, Quan F, Cao Q, Lin Y, Yue C,

Cui X, Yang H, Gao X and Zhang D: Ferroptosis involves in renal

tubular cell death in diabetic nephropathy. Eur J Pharmacol.

888:1735742020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang WJ, Jiang X, Gao CC and Chen ZW:

Salusin-β participates in high glucose-induced HK-2 cell

ferroptosis in a Nrf-2-dependent manner. Mol Med Rep. 24:6742021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li S, Zheng L, Zhang J, Liu X and Wu Z:

Inhibition of ferroptosis by up-regulating Nrf2 delayed the

progression of diabetic nephropathy. Free Radic Biol Med.

162:435–449. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rojas-Rivera J, Ortiz A and Egido J:

Antioxidants in kidney diseases: The impact of bardoxolone methyl.

Int J Nephrol. 2012:3217142012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang YY, Yang YX, Zhe H, He ZX and Zhou

SF: Bardoxolone methyl (CDDO-Me) as a therapeutic agent: An update

on its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Drug Des

Devel Ther. 8:2075–2088. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Suzuki T and Yamamoto M: Molecular basis

of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic Biol Med. 88((Pt B)): 93–100.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yu H, Guo P, Xie X, Wang Y and Chen G:

Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death, and its relationships with

tumourous diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 21:648–657. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Pergola PE, Krauth M, Huff JW, Ferguson

DA, Ruiz S, Meyer CJ and Warnock DG: Effect of bardoxolone methyl

on kidney function in patients with T2D and Stage 3b-4 CKD. Am J

Nephrol. 33:469–476. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Nangaku M, Takama H, Ichikawa T, Mukai K,

Kojima M, Suzuki Y, Watada H, Wada T, Ueki K, Narita I, et al:

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of

bardoxolone methyl in patients with diabetic kidney disease: Design

and baseline characteristics of the AYAME study. Nephrol Dial

Transplant. 38:1204–1216. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Pergola PE, Raskin P, Toto RD, Meyer CJ,

Huff JW, Grossman EB, Krauth M, Ruiz S, Audhya P, Christ-Schmidt H,

et al: Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2

diabetes. N Engl J Med. 365:327–336. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tadao A, Kengo Y, Tomohiro I, Kazuya M and

Masaomi N: AYAME Study: Randomized, Double-Blind,

Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Study of Bardoxolone Methyl in Diabetic

Kidney Disease (DKD) Patients FR-OR110. JASN. 34:pB12023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kanda H and Yamawaki K: Bardoxolone

methyl: Drug development for diabetic kidney disease. Clin Exp

Nephrol. 24:857–864. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans

J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL,

et al: The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of

quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 55:611–622.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ye L, Jin F, Kumar SK and Dai Y: The

mechanisms and therapeutic targets of ferroptosis in cancer. Expert

Opin Ther Targets. 25:965–986. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R,

Lee ED, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason CE, Tatonetti NP, Slusher BS

and Stockwell BR: Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate

exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis.

Elife. 3:e025232014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen X, Comish PB, Tang D and Kang R:

Characteristics and biomarkers of ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9:6371622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hayes JD, Dayalan Naidu S and

Dinkova-Kostova AT: Regulating Nrf2 activity: Ubiquitin ligases and

signaling molecules in redox homeostasis. Trends Biochem Sci.

50:179–205. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Taqi MO, Saeed-Zidane M, Gebremedhn S,

Salilew-Wondim D, Tholen E, Neuhoff C, Hoelker M, Schellander K and

Tesfaye D: NRF2-mediated signaling is a master regulator of

transcription factors in bovine granulosa cells under oxidative

stress condition. Cell Tissue Res. 385:769–783. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zeng XP, Li XJ, Zhang QY, Liu QW, Li L,

Xiong Y, He CX, Wang YF and Ye QF: Tert-butylhydroquinone protects

liver against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through

Nrf2-activating anti-oxidative activity. Transplant Proc.

49:366–372. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

de Zeeuw D, Akizawa T, Audhya P, Bakris

GL, Chin M, Christ-Schmidt H, Goldsberry A, Houser M, Krauth M,

Lambers Heerspink HJ, et al: Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes

and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 369:2492–2503.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Nangaku M, Kanda H, Takama H, Ichikawa T,

Hase H and Akizawa T: Randomized clinical trial on the effect of

bardoxolone methyl on GFR in diabetic kidney disease patients

(TSUBAKI Study). Kidney Int Rep. 5:879–890. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lu Y, Aimetti AA, Langer R and Gu Z:

Bioresponsive materials. Nat Rev Mater. 2:160752017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Alicic RZ, Neumiller JJ and Tuttle KR:

Combination therapy: An upcoming paradigm to improve kidney and

cardiovascular outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial

Transplant. 40 (Supplement 1):i3–i17. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kaneto H, Fujii J, Myint T, Miyazawa N,

Islam KN, Kawasaki Y, Suzuki K, Nakamura M, Tatsumi H, Yamasaki Y

and Taniguchi N: Reducing sugars trigger oxidative modification and

apoptosis in pancreatic beta-cells by provoking oxidative stress

through the glycation reaction. Biochem J. 320((Pt 3)): 855–863.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tanaka Y, Tran PO, Harmon J and Robertson

RP: A role for glutathione peroxidase in protecting pancreatic beta

cells against oxidative stress in a model of glucose toxicity. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 99:12363–12368. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang L, Chen X and Yan C: Ferroptosis: An

emerging therapeutic opportunity for cancer. Genes Dis. 9:334–346.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![Effects of BM treatment on the

dRib-induced decreases in (A) l-[14C]cystine uptake, (B)

intracellular GSH content and (C) cell viability. (A) NRK-52E cells

were co-stimulated with 0, 10, 30 and 50 mM dRib with or without

0.2 µM BM for 4 h in the extracellular fluid buffer containing 1.7

µM l-[14C]cystine (0.1 µCi/ml) at 37°C. The

radioactivity incorporated into the cells was determined by a

liquid scintillation counter. (B and C) The cells were

co-stimulated with 0, 10, 30 and 50 mM dRib with or without 0.2 µM

BM for 6 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS. (B) Intracellular GSH

concentration was measured using a GSH assay kit. (C) Cell

viability was measured by LDH release assay. The data are presented

as the mean ± SD. These experiments were performed thrice, in

triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control and

††P<0.01 vs. dRib alone, as determined by one-way

analysis of variance and Tukey's post-hoc test or Welch's ANOVA

followed by Dunnett's T3 post hoc test, depending on the result of

Levene's test. BM, bardoxolone methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose; GSH,

glutathione; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; DMEM, Dulbecco's Modified

Eagle Medium; FBS, fetal bovine serum; SD, standard deviation.](/article_images/mmr/32/4/mmr-32-04-13632-g00.jpg)

![Effects of ML385 and brusatol on the

protective effects of BM treatment on dRib-induced changes in (A)

l-[14C]cystine uptake, (B) intracellular GSH and (C)

iron contents, (D) intracellular MDA, (E) lipid ROS levels and (F)

cell viability. (A) NRK-52E cells were co-stimulated with 0.2 µM

BM, 100 µM ML385, or 100 µM brusatol and 50 mM dRib for 4 h in the

extracellular fluid buffer containing 1.7 µM

l-[14C]cystine (0.1 µCi/ml) at 37°C. The radioactivity

incorporated into the cells was determined by a liquid

scintillation counter. (B-D and F) NRK-52E cells were co-stimulated

with 0.2 µM BM, 100 µM ML385, or 100 µM brusatol and 50 mM dRib for

6 h in DMEM media containing 10% FBS. The intracellular GSH and

iron levels, intracellular MDA levels, and cell viability were

measured using a GSH assay kit, an iron assay kit, MDA assay kit,

and LDH release assay kit, respectively. These experiments were

performed thrice, in triplicate. (E) Intracellular lipid ROS level

was quantified by flow cytometry using the lipophilic fluorescent

dye C11-BODIPY. Cells were incubated with 4 µM C11-BODIPY during

the final 30 min. Fold control of the mean fluorescence intensity

of experimental groups. This experiment was performed four times.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P<0.01 vs. control;

††P<0.01 vs. 50 mM dRib-alone group;

‡‡P<0.01 vs. 50 mM dRib plus 0.2 µM BM group, as

determined by one way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc

test. BM, bardoxolone methyl; dRib, 2-deoxy-d-ribose; GSH,

glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen

species.](/article_images/mmr/32/4/mmr-32-04-13632-g01.jpg)