Introduction

Liver fibrosis represents a reparative response to

sustained hepatic injury caused by autoimmune hepatitis, primary

cholangitis, alcoholic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma,

with advanced fibrotic stages often progressing to cirrhosis

(1,2). The activation of hepatic stellate

cells (HSCs) is a central event in the onset and progression of

fibrosis, and its inhibition has been shown to attenuate disease

severity (3,4). Disruption of hepatic circadian

regulation has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of both

acute and chronic liver disorders (5,6). The

circadian clock, a ubiquitous endogenous regulatory mechanism, is

conserved across nearly all living organisms and enables

physiological adaptation to temporal environmental fluctuations

(7). Core components of the

circadian machinery include Clock, brain and muscle arnt-like

protein 1 (Bmal1), period circadian regulator (Per)1/2/3,

cryptochrome (Cry)1/2 and nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D

member 1 (Rev-erbα), among others (6,8).

Genetic ablation of Per1/2 or Bmal1 in mouse models resulted in

impaired hepatic function, persistent inflammation and fibrotic

remodeling (9–11). In a cholestasis-induced liver

injury model, Per2 deficiency led to upregulation of liver

fibrosis-related genes and excessive extracellular matrix

deposition (11,12), indicating that circadian disruption

contributes to chronic hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis.

Rev-erbα regulates transcriptional networks involved

in metabolism, circadian rhythm and inflammation, positioning it as

a therapeutic target for metabolic disorders, malignancies,

epilepsy, inflammatory conditions and neurodegenerative diseases

(13–19). Notably, a marked reduction in both

the baseline expression and oscillatory amplitude of Rev-erbα has

been observed in carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced

mouse liver fibrosis models and in vitro activated HSCs

(10,20). Previous functional studies

indicated that Rev-erbα knockdown activated the cyclic GMP-AMP

synthase (cGAS) pathway, promoting a pro-inflammatory

microenvironment and accelerating fibrogenic progression (21), whereas its overexpression

suppressed cGAS signaling and mitigated fibrosis (21). Additionally, Rev-erbα has been

identified as a key negative regulator of NLR family domain

containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome expression, with evidence

showing its protective role against ulcerative colitis in mice

(22). Given that NLRP3

inflammasomes can directly activate HSCs and exacerbate liver

fibrosis (23,24), the mechanistic association between

Rev-erbα and NLRP3 signaling in hepatic fibrosis warrants further

elucidation.

To investigate the regulatory role of Rev-erbα in

liver fibrosis and its interaction with the NLRP3 inflammasome, in

the present study, in vivo experiments employed the Rev-erbα

agonist GSK4112 and antagonist SR8278 to pharmacologically enhance

or suppress Rev-erbα expression in a CCl4-induced mouse

model of hepatic fibrosis. In parallel, stable LX-2 cell lines with

Rev-erbα knockdown or overexpression were generated via lentiviral

transduction. Following 24-h transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)

stimulation, cellular activation and downstream signaling events

were evaluated. Based on a comprehensive analysis of the molecular

mechanisms underlying hepatic fibrosis pathogenesis, the present

study aims to elucidate the role of key regulatory factors in

disease progression, thus laying the theoretical groundwork for

developing more effective therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Reagents

CCl4 (cat. no. 5623-5) for liver fibrosis

induction was obtained from National Pharmaceutical Chemical

Reagent (https://www.reagent.com.cn/). TGF-β1

(cat. no. PRT221-0020), used to stimulate LX-2 cell activation, was

sourced from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. The Rev-erbα

agonist GSK4112 (cat. no. 1216744-19-2) and antagonist SR8278 (cat.

no. 1254944-66-5) were purchased from MedChemExpress. Serum alanine

aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels

were quantified using ALT (cat. no. C009-2-1) and AST (cat. no.

C010-2-1) assay kits from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute. For liver tissue staining, Masson's trichrome kit (cat.

no. G1006), hematoxylin solution (cat. no. G1077) and

diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogenic kit (cat. no. G1212) were

obtained from Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., while the

Sirius Red staining kit (cat. no. 2610-10-8) was sourced from

ChemicalBook Inc. Xylene (cat. no. 1330-20-7), glycerol (cat. no.

56-81-5), citrate buffer (cat. no. 6132-04-3) and glacial acetic

acid (cat. no. 64-19-7), used for immunohistochemistry, were

supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Cell culture

reagents included DMEM (cat. no. 8119054) and FBS (cat. no.

A5670701) from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. The CCK-8 cell

viability assay kit (cat. no. 40203ES80) was provided by Shanghai

Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Custom lentiviral transfection

reagents for Rev-erbα overexpression and knockdown were obtained

from Jikai Biotechnology, and puromycin (cat. no. ST551-50mg) used

for selection was purchased from Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology. Total RNA was extracted using a commercial RNA

extraction kit (cat. no. 19211ES60) from Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd., followed by reverse transcription with a

kit from Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd. (cat. no. KR118). SYBR Green

qPCR mix (cat. no. 11201E03) was purchased from Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Primers targeting α-smooth muscle actin

(α-SMA), TGF-β1, Rev-erbα, NLRP3, Caspase-1, apoptosis associated

speck (ASC), interleukin (IL)-18, IL-1β and β-actin were designed

based on GenBank cDNA sequences and synthesized by Shanghai

Shanjing Molecular Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Protein extraction was

performed using RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. WB0102) with protease

inhibitors (cat. no. WB0122), both from Shanghai Weiao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Protein concentration was determined using

a BCA assay kit (cat. no. MA-0082-2) from Dalian Meilun Biology

Technology Co., Ltd., and chemiluminescent detection was performed

with an ECL kit (cat. no. SW-WB012) from Shanghai Weiao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Primary antibodies against Rev-erbα (cat.

no. ab305753), Caspase-1 (cat. no. ab207802), IL-18 (cat. no.

ab243091), IL-1β (cat. no. ab254360), α-SMA (cat. no. ab124964),

collagen 1 (COL-1) (cat. no. ab34710) and TGF-β1 (cat. no. ab27937)

were obtained from Abcam. Antibodies against NLRP3 (cat. no. 15101)

and ASC (cat. no. 67824S) were sourced from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. β-actin (cat. no. GB15003) and HRP-conjugated

Affinipure Goat Anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. GB22303) were provided by

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.

Animal experiments

A total of 42 male C57BL/6 mice, SPF grade, 6 weeks

(22±2 g) were obtained from Shanghai Jiesijie Experimental Animal

Co., Ltd., and housed under standard conditions at the Animal

Facility of Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese

Medicine. Mice were kept at a standard temperature of 25–27°C and a

humidity of 55–65%, in a light/dark cycle of 12/12 h, and with

ad libitum access to sterilized food and water. After a

1-week acclimatization period, animals were randomly assigned to

experimental groups as follows: i) A total of 12 mice were divided

into a control group (Con) and a CCl4-induced model

group (CCl4) (n=6 per group). Liver fibrosis was induced

by intraperitoneal injection of a 20% CCl4 solution in

olive oil (5 ml/kg), administered twice weekly for 6 weeks

(25). Control mice received an

equal volume of physiological saline. ii) The remaining 30 mice

were randomly allocated into three groups: Control (n=12), GSK4112

(n=12) and SR8278 (n=12). For pharmacological modulation of

Rev-erbα, lyophilized GSK4112 and SR8278 were reconstituted in

DMSO. Mice in the SR8278 group received daily intraperitoneal

injections of SR8278 (25 mg/kg) (26), while those in the GSK4112 group

were administered GSK4112 (20 µg/mouse) (27,28).

Control mice were treated with equivalent volumes of DMSO.

Injections were performed once daily for 14 consecutive days. After

treatment, six mice from each group were randomly selected and

reassigned to receive CCl4 treatment as described above,

forming the CCl4 group (n=6), SR8278 + CCl4

group (n=6) and GSK4112 + CCl4 group (n=6).

Upon completion of modeling, mice were anesthetized

with 1% pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg). Livers were harvested,

with a 1×1-cm section from the central lobe fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for histological analysis at ~25°C. The remaining

tissue was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for

subsequent experiments. Euthanasia was performed via cervical

dislocation (29). All animal

procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai

Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Shanghai,

China; approval no. 2022033).

Cell culturing and treatment

The human HSC LX-2 cell line was obtained from

Shanghai Kanglang Biological Technology Co., Ltd., and cultured in

DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS under standard conditions (37°C and

5% CO2).

For fibrogenic induction, LX-2 cells were divided

into a control group and a TGF-β1-treated group, with the latter

exposed to 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 24 h (25).

The Rev-erbα overexpression plasmid and knockdown

shRNA plasmid utilized in this study were constructed by Shanghai

Jikai Biotechnology, employing a triple-plasmid co-transfection

system in 293T cells for lentiviral production; the lentiviral

supernatant was concentrated and purified into high-titer stocks

within 48–72 h post-transfection. For Rev-erbα overexpression

lentivirus, the plasmid combination consisted of the transfer

plasmid GV208 carrying the target gene Rev-erbα (4 µg), the

packaging plasmid Helper 1.0 (3 µg), and the envelope plasmid

Helper 2.0 (1 µg). For Rev-erbα knockdown lentivirus, the plasmids

included the transfer plasmid pLKO.1-shRNA (4 µg), the packaging

plasmid psPAX2 (3 µg) and the envelope plasmid pMD2.G (1 µg). LX-2

cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 5×104 cells/ml (1

ml/well) and were assigned to the following groups: Con522

(negative control for Rev-erbα overexpression), con313 (negative

control for Rev-erbα knockdown), OvRev-erbα (Rev-erbα

overexpression; MOI=10) and Rev-erbα sh1/sh2/sh3 (shRev-erbα

knockdown groups; MOI=30/20/10, respectively). After adherence to

24-well plates and reaching 20–30% confluency, transduction was

performed with Rev-erbα lentiviruses at different multiplicities of

infection. The viral volume was calculated using the formula: Virus

volume (µl)=(MOI × cell number)/viral titer (TU/ml). After 12 h of

incubation at 37°C, the DMEM was replaced with culture medium

containing 10% FBS, and cells were cultured for an additional 72 h.

Transduction efficiency was assessed via fluorescence inverted

microscopy (Olympus IX73; Olympus Coporation) to determine optimal

conditions. Puromycin selection (2 µg/ml) was initiated at 72 h

post-transduction and maintained for 7–14 days. Successful Rev-erbα

modulation was validated by RT-qPCR for mRNA expression and western

blotting for protein expression, as performed below, with

successfully transfected cells subsequently used for further

experiments.

To assess the effect of Rev-erbα on TGF-β1-induced

activation, LX-2 cells were categorized into TGF-β1, OvRev-erbα +

TGF-β1 and shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 groups. Based on preliminary

findings, OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 was transduced with Rev-erbα at

MOI=10 and shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 received interference at MOI=20. The

TGF-β1 group was treated with DMEM without viral particles. All

groups were subsequently treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 24 h at

37°C and in 5% CO2.

Serum liver function analysis

For serum collection, blood samples from each mouse

group were left at room temperature (25°C) for 4 h, centrifuged at

3,000 rpm and 4°C for 15 min, and serum was harvested. AST and ALT

levels were measured using the aforementioned commercially

available detection kits, following the manufacturer's

protocols.

Masson and Sirius red staining

Fresh liver specimens (~1×1 cm) were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h. After paraffin

embedding, tissue sections were stained using Masson's trichrome

and Sirius red protocols. For liver tissues, sections of 5–7 µm in

thickness were used. Collagen fiber staining was performed at room

temperature, with Masson's trichrome staining for 10 min and Sirius

red staining for 30 min. Histopathological alterations were

assessed using a light microscope at ×200 magnification (BX41,

Beijing Ruike Zhongyi Technology Co., Ltd.).

Cellular immunofluorescence

detection

For immunofluorescence, cells from the TGF-β1,

OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 and shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 groups were fixed with

4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min and subjected to

10% FBS blocking at 37°C for 30 min. The TGF-β1, OvRev-erbα +

TGF-β1 and shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 groups were incubated with an α-SMA

antibody (1:200) at 4°C for 16 h, followed by secondary antibody

incubation at room temperature for 50 min. After PBS washing (pH

7.4), nuclei were counterstained with DAPI at 25°C for 10 min in

the dark. Slides were rinsed, spin-dried and mounted using an

anti-fade glycerol medium. Fluorescence imaging was performed with

a fluorescence inverted microscope (Olympus IX73 microscope).

Quantification of positive staining was carried out using ImageJ

1.8.0 software (National Institutes of Health), and statistical

analyses of protein expression levels were performed using GraphPad

Prism 8.3.0 (Dotmatics).

Immunohistochemical detection of liver

tissue

Following fixation (4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature for 24 h), liver tissues were dehydrated at room

temperature for 30 min and embedded in paraffin (melting point

~60°C). Paraffin blocks were sectioned into 5-µm slices, rinsed and

air-dried prior to staining. The procedure included the following

steps: i) At room temperature, dewaxing with xylene for 30 min and

graded ethanol hydration (100, 95, 80 and 75%) for 20 min; ii)

rehydration through a descending ethanol series followed by

distilled water rinses; iii) nuclear staining with hematoxylin at

room temperature for 10 min; iv) rinsing in distilled water; v)

antigen retrieval by heating sections in 200 ml 0.01Μ citrate

buffer (pH6.0) at 70°C for 10 min; vi) washing in PBS three times

(5 min each), then incubating in 3% hydrogen peroxide at room

temperature for 10 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity;

vii) blocking with 2% FBS in PBS at 37°C for 2 h; viii) incubation

with primary antibodies, α-SMA (1:500), COL-1 (1:600) and TGF-β1

(1:800), at 4°C for 16 h; ix) after PBS washes, incubation with

HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200) at 37°C

for 2 h; x) DAB chromogenic development for 10 min; xi) rinsing

with distilled water; and xii) clearing with xylene for 10 min,

followed by mounting with neutral resin and drying at 70°C.

Microscopic images were captured using a Horiba BX41 light

microscope (Beijing Ruike Zhongyi Technology Co., Ltd.) from five

randomly selected fields per section at magnifications of ×100 and

×400. Quantitative analysis of antibody-positive staining areas was

performed using ImageJ 1.8.0 software (National Institutes of

Health). Statistical analysis of target protein expression levels

was conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.3.0 (Dotmatics).

Cell viability detection

Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. A

suspension of 2×103 cells in 100 µl complete culture

medium containing 10% FBS was seeded into each well of a 96-well

plate and incubated under standard conditions (37°C and 5%

CO2) for 6 h. Subsequently, 10 µl CCK-8 solution were

added to each well. After 2 h of incubation, optical density (OD)

was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Epoch2;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.). OD values were used to calculate cell

viability, and results were presented in histogram form for

comparative analysis.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

For RT-qPCR analysis, 40–50 mg of liver tissue was

collected from each group, and total RNA was extracted using

TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

precipitated in ethanol. Reverse transcription was performed using

the FastKing gDNA Dispelling RT SuperMixJun (cat. no. KR118;

Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.), and the resulting cDNA was diluted

10-fold with ddH2O for amplification. qPCR was performed

using SYBR Green PCR Mastermix (cat. no. 11201E03). The results

were analyzed on an ABI StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied

Biosystems) using the 2−ΔΔCq method (30). Values were normalized to β-actin.

The reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C predenaturation once

for 5 min, followed by denatured at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at

60°C for 20 sec and extension at 72°C for 20 sec, for 40 cycles.

Primer sequences are provided in Table SI.

Western blotting analysis

The quantity of whole-protein extracts from cells

and livers of mice, extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no.

WB0102) with protease inhibitors (cat. no. WB0122), were determined

using the BCA assay. Equal amounts of total protein (20–30 µg) were

resolved by 7.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes.

After blocking with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 2 h,

the membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies for

16 h at 4°C [Rev-erbα (1:1,000), Caspase-1 (1:1,000), IL-18

(1:1,000), IL-1β (1:1,000), α-SMA (1:1,000), collagen 1 (1:1,000),

TGF-β1 (1:1,000), NLRP3 (1:1,000), ASC (1:1,000) and β-actin

(1:3,000)], followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated Affinipure

Goat Anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000) at room temperature for 2 h. Signal

detection was performed using a chemiluminescence imaging system

(Amersham Imager 600; Cytiva), and band intensities were

semi-quantified using ImageJ 1.8.0 software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism 8.3.0 (Dotmatics). Comparisons between two groups were

performed using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests, while multiple-group

comparisons were evaluated by one-way ANOVA. When comparing ≥3

groups (e.g., shRev-erbα 1, shRev-erbα 2 and shRev-erbα3) requiring

assessment of all possible pairwise comparisons (shRev-erbα 1 vs.

shRev-erbα 2, shRev-erbα 1 vs. shRev-erbα 3 and shRev-erbα 2 vs.

shRev-erbα 3), Tukey's test was employed for post-hoc evaluation.

When analyzing ≥3 groups (e.g., CCl4, GSK4112 +

CCl4 and SR8287 + CCl4) focusing on specific

pairwise comparisons between predetermined groups (CCl4

vs. GSK4112 + CCl4 and CCl4, vs. SR8287 +

CCl4), Bonferroni's correction was applied for post-hoc

statistical assessment. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

P<0.05 was used to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Reduced expression of circadian clock

gene Rev-erbα in liver fibrosis

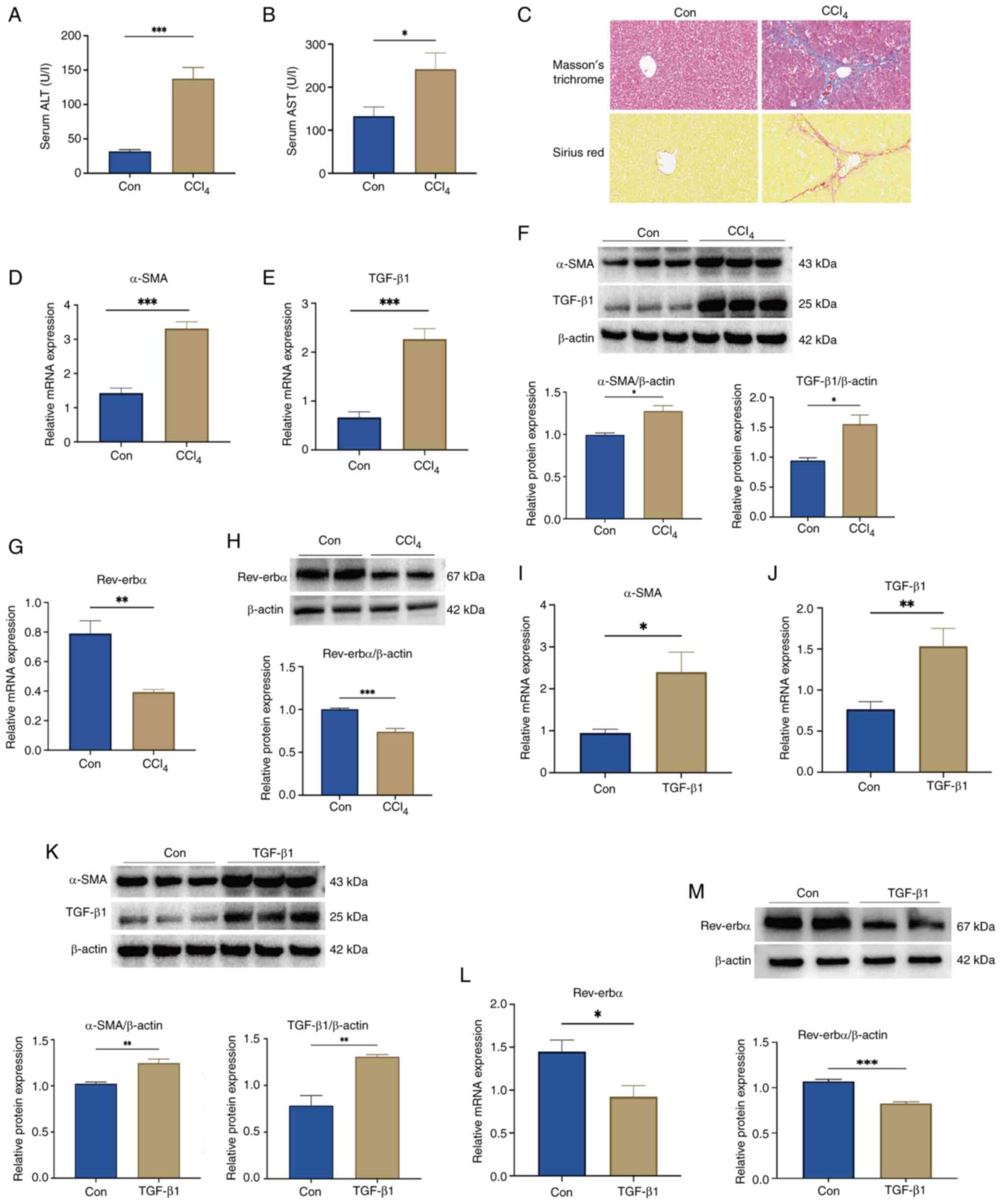

To investigate the expression dynamics of the

circadian clock gene Rev-erbα in liver fibrosis, a mouse model was

established using CCl4 administration. Compared with

those in the Con group, serum ALT and AST levels were significantly

elevated in the CCl4-treated mice, indicating

substantial hepatic injury (Fig. 1A

and B). Histological analysis via Masson's trichrome and Sirius

red staining revealed well-preserved hepatic architecture in the

control group, whereas CCl4-treated mice exhibited

marked collagen deposition and expanded fibrotic areas, consistent

with progressive fibrosis (Fig.

1C). In parallel, mRNA and protein expression levels of TGF-β1

and α-SMA were significantly upregulated in the livers of

CCl4-treated mice compared with levels in the controls

(Fig. 1D-F), confirming successful

model induction. Notably, Rev-erbα mRNA and protein levels were

significantly reduced in the liver tissue of CCl4 group

mice relative to the controls (Fig. 1G

and H). This downregulation was further corroborated in

vitro, where TGF-β1-stimulated LX-2 cells showed significant

upregulation of fibrotic markers (α-SMA and TGF-β1) (Fig. 1I-K) and a concomitant decrease in

Rev-erbα expression at both the transcript and protein levels

(Fig. 1L and M). These results

suggest that Rev-erbα may act as a negative regulator in the

progression of liver fibrosis, with its reduced expression

potentially facilitating fibrogenic and pro-inflammatory responses

in hepatic tissue.

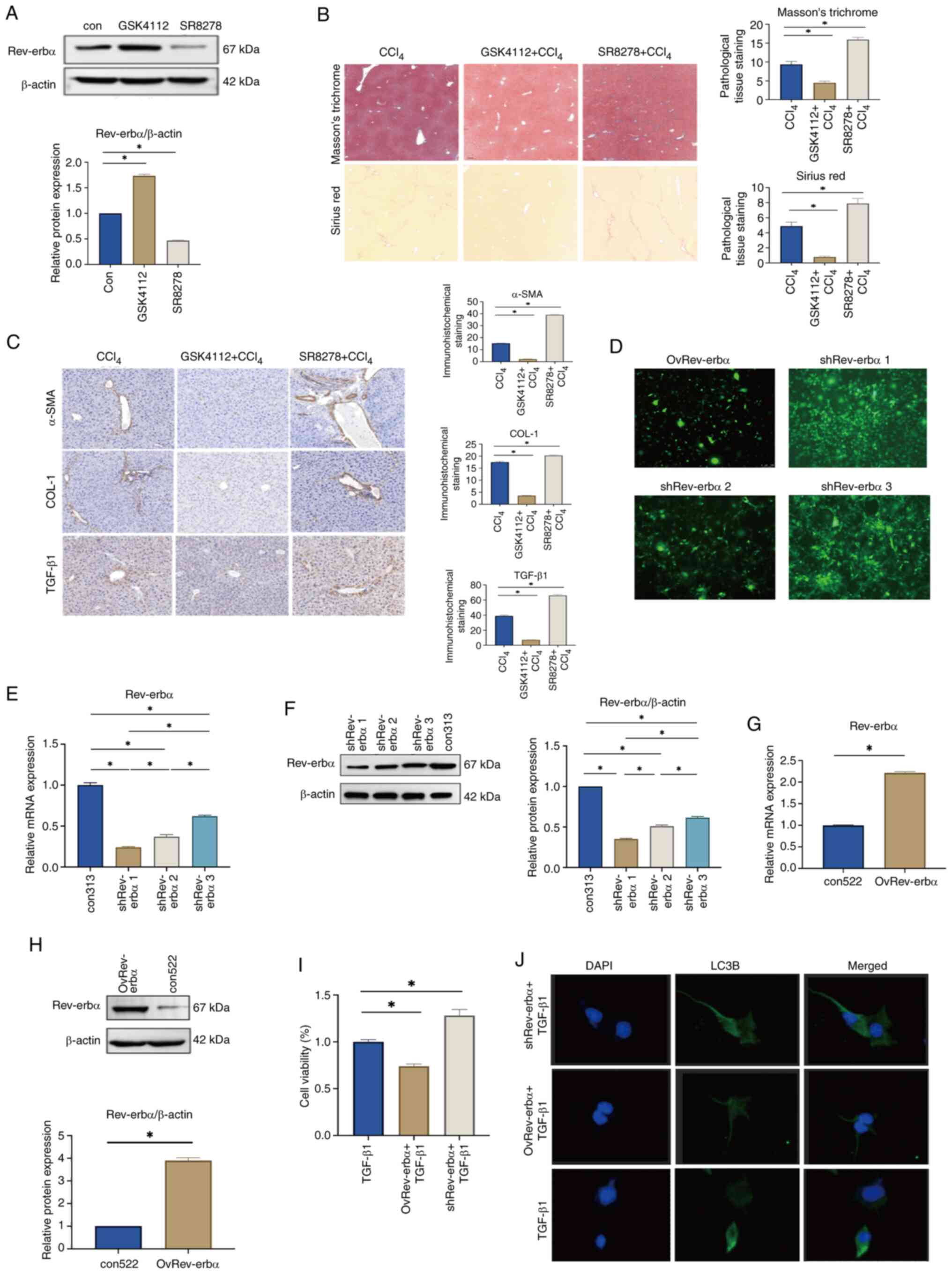

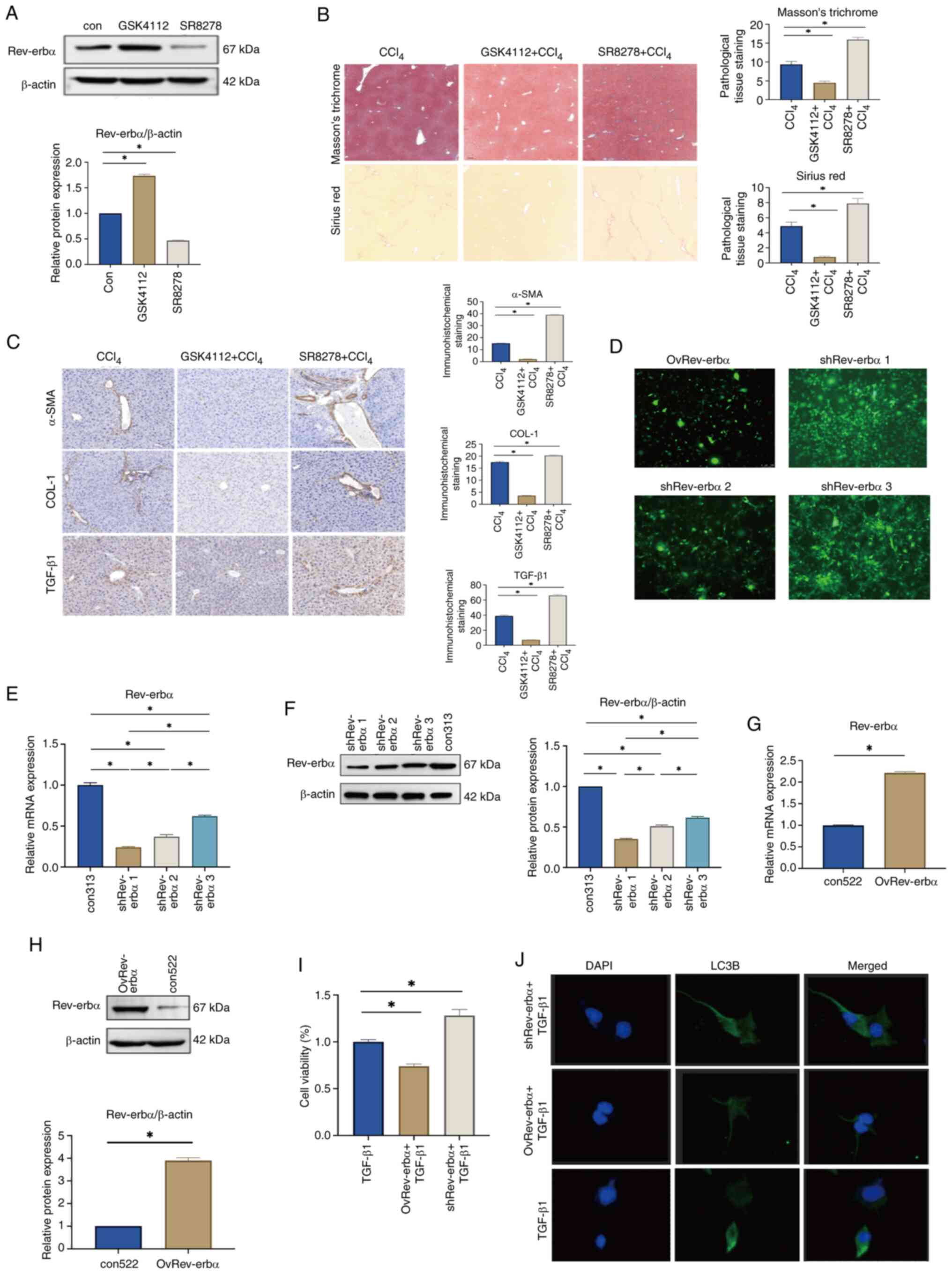

Rev-erbα has a significant inhibitory

impact on liver fibrosis

Rev-erbα serves as a critical transcriptional

regulator of metabolic, circadian and inflammatory pathways,

rendering it a promising therapeutic target for metabolic

disorders, malignancies, epilepsy, inflammatory conditions and

neurodegenerative diseases (22,31).

To evaluate its role in liver fibrosis progression, C57BL/6 mice

received intraperitoneal injections of the Rev-erbα agonist GSK4112

(25 mg/kg) or the antagonist SR8278 (20 µg/mouse). Western blot

analysis confirmed successful pharmacological modulation, with

Rev-erbα expression significantly reduced in the SR8278 group and

significantly elevated in the GSK4112 group (Fig. 2A).

| Figure 2.Rev-erbα significantly inhibits liver

fibrosis. (A) Rev-erbα protein expression in mouse liver tissue

following administration of Rev-erbα agonist GSK4112 or inhibitor

SR8278 (n=3). (B) Liver histopathology in the CCl4,

GSK4112 + CCl4 and SR8278 + CCl4 groups

(Masson's trichrome and Sirius red staining; ×100 magnification)

(n=3). (C) Expression of α-SMA, COL-1 and TGF-β1 in liver tissue of

CCl4-induced liver fibrosis mice from in the

CCl4, GSK4112 + CCl4 and SR8278 +

CCl4 groups (×400 magnification) (n=3). (D) Lentiviral

fluorescence expression in stable Rev-erbα gene knockdown or

overexpression cell lines (×200 magnification). The greater the

extent of green fluorescent areas, the better the lentiviral

transduction efficacy. (E) The mRNA expression of Rev-erbα in

shRev-erbα cell groups (n=6). (F) Protein expression of Rev-erbα in

the shRev-erbα cell group (n=6). (G) The mRNA expression of

Rev-erbα in the OvRev-erbα cell group (n=6). (H) Protein expression

of Rev-erbα in the OvRev-erbα cell group (n=6). (I) LX-2 cell

viability in the TGF-β1, OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 and shRev-erbα +

TGF-β1 groups (n=3). (J) Expression of α-SMA in the TGF-β1,

OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 and shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 groups

(immunofluorescence; ×200 magnification). Data are expressed as the

mean ± SEM; *P<0.05. Con, control; Rev-erbα, nuclear receptor

subfamily 1 group D member 1; TGF-β1, transforming growth

factor-β1; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; CCl4, carbon

tetrachloride; COL-1, collagen 1; DAPI,

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; LC3B, microtubule-associated protein

1A/1B light chain 3β. |

Following model establishment, liver fibrosis was

induced using CCl4. Histological staining with Masson's

trichrome and Sirius red revealed pronounced pseudolobule

formation, extensive collagen accumulation and expanded fibrotic

areas in the CCl4 + SR8278 group. By contrast, the

CCl4 + GSK4112 group exhibited more preserved hepatic

architecture, reduced fibrous proliferation and an absence of

steatosis compared with the CCl4 group (Fig. 2B). Immunohistochemical analysis

further demonstrated that expression levels of α-SMA, COL-1 and

TGF-β1 were significantly upregulated in the CCl4 +

SR8278 group, whereas these markers were significantly

downregulated in the CCl4 + GSK4112 group (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that

Rev-erbα suppression exacerbates fibrogenesis, while its activation

attenuates hepatic inflammation, collagen deposition and fibrotic

remodeling. Lentiviral transduction was employed to establish LX-2

cell lines with stable Rev-erbα knockdown or overexpression for

subsequent in vitro investigations. Fluorescence microscopy

confirmed that Rev-erbα sh1 (MOI=20) achieved the most effective

knockdown (Fig. 2D), with

significantly reduced mRNA and protein expression levels of

Rev-erbα in LX-2 cells (Fig. 2E and

F). This condition was subsequently selected for downstream

experiments. Fluorescence microscopy confirmed efficient

overexpression of Rev-erbα in the MOI=10 group (Fig. 2D), accompanied by a significant

increase in both mRNA and protein levels of Rev-erbα in LX-2 cells

(Fig. 2G and H). LX-2 cells were

then allocated into three groups: TGF-β1, OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 and

shRev-erbα + TGF-β1. Following lentiviral transduction at the

defined MOIs, cells were stimulated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 24 h to

induce activation. CCK-8 assays revealed a significant reduction in

cell viability in the OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 group, while the

shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 group exhibited a significant increase in

viability, compared with the TGF-β1 group (Fig. 2I). Immunofluorescence analysis

further demonstrated that α-SMA expression was substantially

downregulated in the OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 group, whereas notable

upregulation was observed in the shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 group

(Fig. 2J). These results suggest

that decreased Rev-erbα expression promotes HSC activation and

fibrogenic responses, whereas its overexpression exerts a

suppressive, anti-fibrotic effect.

Rev-erbα inhibits NLRP3 and alleviates

liver fibrosis

The NLRP3 inflammasome consists of ASC, caspase-1

and NLRP3, with ASC serving as a key adaptor that promotes the

recruitment and activation of caspase-1 and NLRP3. Caspase-1

processes the inactive precursors of IL-1β and IL-18 into their

mature, bioactive forms, thereby initiating pyroptosis and

inflammatory responses that play central roles in the progression

of alcoholic liver disease, viral hepatitis and liver fibrosis

(32,33).

In the present study, following CCl4

induction in three groups of mice, Rev-erbα protein expression was

assessed. Compared with those in the CCl4 group, the

protein levels of Rev-erbα in the GSK4112 + CCl4 group

were significantly elevated and those in the SR8278 +

CCl4 group were significantly decreased (Fig. 3A). To examine whether the

anti-fibrotic effect of Rev-erbα is mediated through modulation of

the NLRP3 inflammasome, liver fibrosis models were generated in

C57BL/6 mice subjected to CCl4 combined with either

GSK4112 or SR8278 treatment. Expression levels of NLRP3, caspase-1,

ASC and downstream proinflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-1β were

analyzed in liver tissue. Relative to the CCl4 group,

mRNA expression of NLRP3, caspase-1, ASC, IL-18 and IL-1β was

significantly reduced in the GSK4112 + CCl4 group,

whereas significant increases were observed in the SR8278 +

CCl4 group (Fig. 3B),

with protein expression showing consistent trends (Fig. 3C). To further substantiate these

findings, validation was performed in three groups of LX2 cells.

Following TGF-β1 stimulation, Rev-erbα protein expression was

assessed. Compared with that in the TGF-β1 group, Rev-erbα

expression was significantly upregulated in the OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1

group and markedly downregulated in the shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 group

(Fig. 3D). Subsequent analysis

focused on the regulatory effect of Rev-erbα on the NLRP3

inflammasome in LX2 cells. RT-qPCR and western blotting results

demonstrated that, relative to the TGF-β1 group, mRNA and protein

levels of NLRP3, caspase-1, ASC and the downstream cytokines, IL-18

and IL-1β, were significantly suppressed in the OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1

group, whereas marked increases were observed in the ShRev-erbα +

TGF-β1 group (Fig. 3E and F).

These results indicate that Rev-erbα knockdown promotes

inflammatory responses during liver fibrosis by enhancing NLRP3

inflammasome activation in HSCs, thereby elevating the expression

of IL-18 and IL-1β. By contrast, overexpression of Rev-erbα

reverses these effects.

| Figure 3.Rev-erbα inhibits NLRP3 and reduces

liver fibrosis. (A) Protein expression of Rev-erbα in the

CCl4, GSK4112 + CCl4 and SR8278 +

CCl4 groups (n=3). (B) The mRNA expression of NLRP3,

caspase-1, ASC, IL-18 and IL-1β in the CCl4, GSK4112 +

CCl4 and SR8278 + CCl4 groups (n=3). (C)

Protein expression of NLRP3, caspase-1, ASC, IL-18 and IL-1β in the

CCl4, GSK4112 + CCl4 and SR8278 +

CCl4 groups (n=3). (D) Protein expression of Rev-erbα in

the TGF-β1, OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 and shRev-erbα + TGF-β1 groups

(n=3). (E) The mRNA expression of NLRP3, caspase-1, ASC, IL-18 and

IL-1β in the TGF-β1, OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 and shRev-erbα + TGF-β1

groups (n=3). (F) Protein expression of NLRP3, caspase-1, ASC,

IL-18 and IL-1β in the TGF-β1, OvRev-erbα + TGF-β1 and shRev-erbα +

TGF-β1 groups (n=3). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; ns, not

significant; *P<0.05. Rev-erbα, nuclear receptor

subfamily 1 group D member 1; TGF-β1, transforming growth

factor-β1; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; NLRP3, NLR family

domain containing protein 3; ASC, apoptosis associated speck; IL,

interleukin. |

Collectively, the data support a role for Rev-erbα

as an upstream negative regulator of the NLRP3 inflammasome,

contributing to its anti-fibrotic function by attenuating

inflammasome-mediated inflammation in liver fibrosis and activated

HSCs.

Discussion

Liver fibrosis represents a key pathological process

in the development of cirrhosis. Hepatic injury and inflammation,

triggered by factors such as drug toxicity, excessive alcohol

intake, viral infections and autoimmune responses, drive this

progression (34). Upon

stimulation, HSCs undergo transdifferentiation into

myofibroblast-like cells, which secrete extracellular matrix

components that accumulate as scar tissue, thereby advancing

fibrogenesis (1,3). Accumulating evidence indicates that

disruptions in circadian rhythms significantly impact the

pathogenesis of various liver disorders, including fibrosis

(10,35,36).

While the master circadian clock resides in the suprachiasmatic

nucleus of the hypothalamus, peripheral tissues and organs,

including the liver, kidney, myocardium, pancreas and skeletal

muscle, possess autonomous clocks that regulate local rhythmic gene

expression to maintain physiological homeostasis (37).

Alterations in hepatic circadian regulation

profoundly affect the initiation and progression of liver disease.

Bmal1 is a core component of the molecular clock and plays a

pivotal role in regulating lipid, bile acid and glucose metabolism;

its suppression leads to metabolic dysregulation and hepatic

dysfunction (38). Bmal1-deficient

mice, especially under chronic alcohol exposure, exhibit

exacerbated hepatic steatosis and injury (39). Clock gene dysfunction promotes

lipid accumulation in the liver, contributing to the development of

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (40). In addition, NAD-dependent protein

deacetylase sirtuin-1 modulates hepatic insulin sensitivity through

the Clock/Bmal1 axis (41).

Genetic ablation of Clock and Bmal1 results in hypoglycemia,

whereas loss of Per and Cry leads to hyperinsulinemia (42). Notably, Rev-erbα knockdown

activates the cGAS pathway, induces a localized proinflammatory

microenvironment and accelerates liver fibrosis progression

(21).

The liver clock genes Rev-erbα and Rev-erbβ, both

classified as orphan nuclear receptors, cooperatively regulate

circadian rhythms and metabolic homeostasis (14,43).

Rev-erbα has been shown to modulate bile acid and cholesterol

biosynthesis by regulating SREBP regulating gene protein expression

in mice, and its genetic deletion leads to impaired bile acid

metabolism (44). Simultaneous

ablation of both Rev-erbα and Rev-erbβ in double-knockout models

severely disrupts the rhythmic expression of lipid

metabolism-related genes (14,45).

Beyond hepatic functions, Rev-erbα also plays a critical role in

maintaining intestinal barrier permeability and treating NASH

(46). In NASH mouse models

induced by a high-cholesterol, high-fat diet, intestinal expression

of Rev-erbα and tight junction-associated genes is downregulated,

resulting in increased intestinal permeability. Pharmacological

activation of Rev-erbα with SR9009 ameliorates hepatic lipid

accumulation, insulin resistance, inflammation and fibrosis, in

part by enhancing intestinal barrier function (46). Additionally, Rev-erbα has been

implicated in the regulation of the long non-coding RNA Platr4,

which attenuates NASH progression by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome

activation (47). Another study

demonstrated that intestinal Rev-erbα deficiency exacerbates

high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity. Pharmacological modulation of

the Rev-erbα/Bmal1 axis using small-molecule compounds alleviated

HFD-induced metabolic dysfunction (48). Collectively, these findings

highlight the critical role of the gut circadian clock,

particularly Rev-erbα, in regulating lipid absorption and energy

balance, offering potential therapeutic targets for obesity and

related metabolic disorders.

Rev-erbα also plays a pivotal role in liver

ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (49). Additionally, Rev-erbα deficiency

exacerbates hepatic I/R injury in mice, as evidenced by elevated

plasma levels of ALT and AST, higher histopathological injury

scores and increased hepatic myeloperoxidase activity. Moreover,

the absence of Rev-erbα leads to heightened expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, enhanced NLRP3 inflammasome activation

and greater infiltration of inflammatory cells. Pharmacological

activation of Rev-erbα significantly mitigates hepatic injury and

the associated inflammatory response, indicating its protective

role through suppression of inflammation (49). Rev-erbα is also critically involved

in the pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver (AFL) (50). In ethanol-fed mice and

ethanol-treated L02 hepatocytes, Rev-erbα expression is markedly

upregulated, and its activation promotes hepatic steatosis.

Inhibition or downregulation of Rev-erbα alleviates lipid

accumulation, primarily by restoring autophagic activity.

Mechanistically, Rev-erbα impairs autophagy via Bmal1-dependent

pathways (50). Treatment with the

Rev-erbα antagonist SR8278 reduces hepatic lipid deposition and

enhances autophagic flux in ethanol-fed mice (50), suggesting that Rev-erbα acts as a

key modulator in AFL progression and represents a potential

therapeutic target. Furthermore, Rev-erbα deficiency in ALD mice

increases CYP4A expression, lipid accumulation and oxidative

stress. Intervention with either the Rev-erbα agonist SR9009 or the

CYP4A inhibitor HET0016 attenuates alcohol-induced hepatic

steatosis and injury, highlighting both Rev-erbα and CYP4A as

viable therapeutic targets in ALD management (51). In addition, the Rev-erbα agonist

GSK4112 has demonstrated protective effects in Fas-induced acute

liver injury (26). In a mouse

model established by administration of the anti-Fas antibody Jo2,

GSK4112 treatment (25 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) significantly

reduced plasma ALT and AST levels, ameliorated liver histological

damage and improved survival. Mechanistically, GSK4112 suppressed

caspase-3 and caspase-8 activity, decreased hepatocyte apoptosis,

downregulated Fas expression and enhanced Akt phosphorylation

(26).

In the context of liver fibrosis research, Wang

et al (52) reported that

Rev-erbα binds directly to the promoter region of the pro-fibrotic

coagulation regulator PAI-1, thereby suppressing its expression and

exerting anti-fibrotic effects. A recent study further revealed

rhythmic oscillations in the expression of TGF-β signaling

components and fibrosis-associated genes in liver tissue from

hepatocyte-specific Rev-erbα/β knockout mice (53). In LX2 cells subjected to circadian

rhythm synchronization, silencing of Rev-erbα led to upregulation

of pro-fibrotic gene expression. Activation of Rev-erbα by SR9009

was shown to reduce SMAD2/3 phosphorylation in TGF-β-stimulated

human lung myofibroblasts, indicating that Rev-erbα activation

impairs TGF-β signaling in both HSCs and myofibroblasts (53). To evaluate the therapeutic

potential of targeting Rev-erbα in MASH-induced fibrosis, the

pharmacological agonist SR9009 was administered to mice fed a

choline-deficient, amino acid-defined, HFD. SR9009 treatment

significantly attenuated hepatic fibrosis, as evidenced by reduced

collagen deposition (Sirius red staining), diminished HSC

activation (α-SMA expression) and downregulation of

fibrosis-related genes (53).

These findings support the therapeutic efficacy of Rev-erbα

agonists in mitigating fibrosis progression. Consistent with these

observations, the present study identified a significant decrease

in Rev-erbα expression in both CCl4-induced liver

fibrosis mouse models and TGF-β-stimulated LX2 cells. These results

suggest that reduced Rev-erbα expression may contribute to the

progression of liver fibrosis.

Studies have identified porphyrin heme as the

endogenous ligand of Rev-erbα. Binding of heme is essential for

Rev-erbα to recruit corepressor complexes, such as nuclear receptor

co-repressor (NCoR), enabling it to actively repress transcription

of its target genes, including Bmal1, glucose-6-phosphatase

(G6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) (26,54).

GSK4112 (also known as SR6452), a synthetic non-porphyrin small

molecule, functions as a Rev-erbα agonist by mimicking the action

of heme (54). Conversely, SR8278

acts as an antagonist, inhibiting the transcriptional repression

activity of Rev-erbα. Structural analyses show that SR8278 closely

resembles agonist molecules, and treatment of HepG2 cells with

SR8278 results in increased expression of Rev-erbα target genes

such as Bmal1, G6Pase and PEPCK, consistent with its ability to

block the effects of endogenous heme (28,55).

Both GSK4112 and SR8278 serve as valuable chemical tools for

probing Rev-erbα functions in transcriptional repression, circadian

regulation and metabolic pathways (26,27).

The repressive function of Rev-erbα is mediated through recruitment

of the NCoR/HDAC3 corepressor complex (56,57).

In addition to transcriptional regulation, protein stability is a

critical mechanism controlling Rev-erbα activity. Rev-erbα is

intrinsically unstable, with a half-life of less than 1 h,

indicating continuous proteolytic turnover (58). Phosphorylation by glycogen synthase

kinase 3β (GSK3β) at serine residues 55 and 59 has been implicated

in modulating Rev-erbα stability (59). Furthermore, a ubiquitin E3 ligase

complex composed of ADP-ribosylation factor binding protein 1 and

MYC binding protein 2 has been shown to mediate lithium-induced

degradation of Rev-erbα (58).

SR8278 (administered via micro slow injection at 20 µg/mouse) has

also been reported to restore the DNA-binding activity of Rev-erbα

and nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 2 at the tyrosine

hydroxylase promoter, promoting enrichment at R/N motifs [The ‘R/N

motif’ specifically refers to a DNA sequence pattern recognized by

transcription factors, wherein R denotes a purine base (adenine (A)

or guanine (G)), and N represents any nucleotide (A, T, C or G)]

recognized by both transcription factors (28). Additionally, SR8278 exerts

antidepressant and anxiolytic effects in 6-OHDA-induced mouse

models in a circadian rhythm-dependent manner, restoring rhythmic

patterns of emotion-related behaviors (27).

To investigate the role of Rev-erbα in liver

fibrosis, in vivo experiments were conducted using the

Rev-erbα agonist GSK4112 (25 mg/kg) and the antagonist SR8278 (20

µg/mouse) to pharmacologically activate or inhibit Rev-erbα

signaling in mice. Liver fibrosis was induced through

intraperitoneal administration of a CCl4 mixture. In

parallel, in vitro experiments involved stable lentiviral

transfection to generate LX-2 cell lines with either Rev-erbα

overexpression or knockdown, followed by TGF-β1 stimulation for 24

h to induce cellular activation. Inhibition of Rev-erbα expression

in mice resulted in increased collagen deposition and elevated

hepatic levels of α-SMA, COL-1 and TGF-β1, while activation of

Rev-erbα reversed these pathological features. Comparable effects

were observed in LX-2 cells, consistent with the established role

of activated HSCs in upregulating α-SMA and COL-1 expression

(60), with α-SMA serving as a

well-recognized marker of HSC activation and fibrosis severity

(61,62). TGF-β1, a key pro-fibrotic cytokine,

is known to drive HSC activation and sustain fibrogenesis (63,64).

Taken together, these findings indicate that downregulation of

Rev-erbα promotes liver fibrosis, whereas its upregulation exerts a

protective, anti-fibrotic effect.

The NLRP3 inflammasome has been implicated in

various inflammatory conditions, including colitis, type 2 diabetes

and atherosclerosis. Loss of Rev-erbα has been shown to exacerbate

atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability and rupture by activating the

NF-κB/NLRP3 axis, thereby increasing macrophage infiltration,

oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine production (65). In breast cancer cells, Rev-erbα

inhibition activates the cGAS-stimulator of interferon genes

pathway, leading to elevated levels of type I interferons and

downstream chemokines, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 and CXC motif

chemokine ligand 10, enhancing antitumor immune responses (66). In HSCs, Rev-erbα degradation

impairs mitochondrial fission and promotes mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA) release, triggering cGAS activation and contributing to a

pro-inflammatory microenvironment that accelerates liver fibrosis

(21). Additionally, Rev-erbα

regulates the circadian rhythm of the NLRP3 inflammasome activity,

and its activation has been shown to alleviate hepatitis in mouse

models (31). The Rev-erbα agonist

SR9009 exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing

pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and preventing monocyte

infiltration during inflammation. Notably, SR9009 alleviated

colitis in wild-type mice but failed to confer protection in NLRP3-

or Rev-erbα-deficient models (67). In models of neuroinflammation,

SR9009 inhibited NLRP3 activation, and reduced IL-6, IL-1β and

IL-18 production, attenuating microglial and astrocyte activation,

and ameliorating status epilepticus (31). Similarly, in degenerative disc

disease, Rev-erbα activation suppressed NLRP3 inflammasome assembly

and IL-1β production, reducing local inflammation (68). These findings underscore the

central role of the Rev-erbα/NLRP3 axis in inflammatory disease

progression. Consistent with this mechanistic framework, the

present study demonstrated that Rev-erbα inhibition in both in

vivo and in vitro liver fibrosis models led to

upregulation of NLRP3, caspase-1, ASC, IL-18 and IL-1β. Conversely,

pharmacological or genetic activation of Rev-erbα suppressed the

expression of these inflammasome components. These results support

the hypothesis that Rev-erbα functions as a negative upstream

regulator of the NLRP3 inflammasome in activated HSCs and fibrotic

liver tissue, thereby mediating its anti-fibrotic effects through

suppression of inflammasome-driven inflammation (Fig. 4).

| Figure 4.Mechanism of Rev-erbα promoting the

progression of liver fibrosis. The decrease in the expression of

the biological clock gene Rev-erbα promotes the activation of NLRP3

inflammasomes (ASC, caspase-1 and NLRP3) and downstream

inflammatory pathways (IL-18 and IL-1β), and promotes the

progression of liver fibrosis. ASC, apoptosis-associated speck;

α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; CCl4, carbon

tetrachloride; COL-1, collagen 1; IL, interleukin; NLRP3, NLR

family domain containing protein 3; Rev-erbα, nuclear receptor

subfamily 1 group D member 1; TGF-β1, transforming growth

factor-β1. |

Although significant progress has been made in

elucidating the role of Rev-erbα in liver fibrosis and its

association with the NLRP3 inflammasome, several limitations remain

that require further investigation. First, the molecular mechanisms

underlying these observations have not been fully explored. While

the present study demonstrates that Rev-erbα negatively regulates

the NLRP3 inflammasome, the specific molecular interactions remain

unclear. Future research should focus on understanding how Rev-erbα

interacts with the various components of the NLRP3 inflammasome and

how this interaction influences the onset and progression of liver

fibrosis. Second, the animal model used in this study,

CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, only partially mimics the

pathological processes of human liver fibrosis and does not fully

reflect clinical conditions. Third, the study's focus on HSCs

limits its scope. Liver fibrosis is a complex, multifactorial

condition involving interactions between various cell types,

including hepatocytes, fibroblasts and immune cells. A broader

examination of the role of these other cell types would provide a

more comprehensive understanding of the disease process. Finally,

while Rev-erbα shows promise as a therapeutic target in liver

fibrosis, translating this potential into clinical applications

faces significant challenges. These include the optimization of

drug delivery systems, addressing inter-individual variability, and

ensuring safety and efficacy in clinical settings.

In light of these limitations, several future

research directions are proposed. Regarding the molecular

mechanisms, building upon existing findings and recent

international advancements, a preliminary hypothesis can be formed

concerning how Rev-erbα regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome in liver

fibrosis. The first potential mechanism involves direct

transcriptional regulation. As a nuclear receptor, Rev-erbα may

bind directly to the promoter regions of NLRP3 inflammasome-related

genes and suppress their transcription. For instance, Rev-erbα

could bind to the promoters of NLRP3, caspase-1 or ASC, inhibiting

their expression and thus reducing NLRP3 inflammasome activity. The

second mechanism involves indirect signaling pathways. Rev-erbα may

modulate NLRP3 inflammasome activity by influencing other cellular

signaling pathways, such as inhibiting the NF-κB pathway, thereby

reducing NLRP3 activation. Additionally, Rev-erbα could regulate

oxidative stress and mitochondrial function, indirectly affecting

inflammasome activity. The third mechanism entails protein-protein

interactions, where Rev-erbα may physically interact with one or

more components of the NLRP3 inflammasome, interfering with its

assembly and function. For example, Rev-erbα might bind to NLRP3,

caspase-1 or ASC, preventing the formation of active inflammasome

complexes. To validate these hypotheses and elucidate the precise

molecular mechanisms by which Rev-erbα regulates the NLRP3

inflammasome in liver fibrosis, advanced molecular biology

techniques such as chromatin immunoprecipitation and RNA sequencing

should be employed. These tools will enable the exploration of how

Rev-erbα interacts with each component of the inflammasome and how

these interactions influence the progression of liver fibrosis.

Furthermore, the development of more clinically relevant animal

models is needed. Models that better replicate the etiology of

human liver fibrosis, such as cholestatic liver disease or viral

hepatitis models, would provide more accurate insights into the

role of Rev-erbα in different types of liver fibrosis. The

interaction between various cell types should also be explored.

Specifically, studying Rev-erbα expression and function in

hepatocytes, immune cells and other cell types will help clarify

how these interactions contribute to the progression of liver

fibrosis. Finally, efforts to promote clinical translation are

essential. Optimizing drug delivery systems and improving the

stability and bioavailability of Rev-erbα modulators will be key to

advancing their therapeutic potential in vivo. Clinical

trials should also be conducted to assess the efficacy and safety

of Rev-erbα regulators in patients with liver fibrosis.

In summary, by deepening our understanding of the

function and regulatory network of Rev-erbα, novel drug targets can

be identified, leading to the development of more effective

anti-fibrotic therapies. This progress not only promises to advance

medical research but also offers new hope for the treatment of

fibrotic diseases, ultimately contributing to a transformative

shift in clinical practice.

In conclusion, expression of the circadian clock

gene Rev-erbα is significantly suppressed in liver fibrosis, which

contributes to fibrogenesis by driving the upregulation of the

downstream NLRP3 inflammasome.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Shanghai Natural Science

Foundation (grant no. 22ZR1459400), the Shanghai Science and

Technology Innovation Project (grant no. 22S21901100), the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82304932), and the

Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project of Shanghai Municipal

Health Commission (grant no. 2022QN052).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JW was responsible for conceptualization,

validation, writing the original draft of the manuscript, using

software, visualization, and reviewing and editing the manuscript.

YW and LL contributed to investigation and the methodology. WP and

YL were responsible for the acquisition of funding, project

administration and formal analysis. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. WP and YL confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiment protocols were approved by the

Ethics Committee of Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional

Chinese Medicine (Shanghai, China; approval no. 2022033).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ASC

|

apoptosis associated speck

|

|

α-SMA

|

α-smooth muscle actin

|

|

Bmal1

|

brain and muscle arnt-like protein

1

|

|

CCl4

|

carbon tetrachloride

|

|

Cry

|

cryptochrome

|

|

cGAS

|

cGMP-AMP synthase

|

|

COL-1

|

collagen 1

|

|

HSC

|

hepatic stellate cell

|

|

IL-1β

|

interleukin-1β

|

|

IL-18

|

interleukin-18

|

|

NLRP3

|

NLR family domain containing protein

3

|

|

Per

|

period circadian regulator

|

|

Rev-erbα

|

nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D

member 1

|

|

TGF-β1

|

transforming growth factor-β1

|

References

|

1

|

Hernandez-Gea V and Friedman SL:

Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 6:425–456. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Parola M and Pinzani M: Liver fibrosis:

Pathophysiology, pathogenetic targets and clinical issues. Mol

Aspects Med. 65:37–55. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Higashi T, Friedman SL and Hoshida Y:

Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv Drug

Deliv Rev. 121:27–42. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tsuchida T and Friedman SL: Mechanisms of

hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

14:397–411. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Frazier K, Manzoor S, Carroll K, DeLeon O,

Miyoshi S, Miyoshi J, St George M, Tan A, Chrisler EA, Izumo M, et

al: Gut microbes and the liver circadian clock partition glucose

and lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 133:e1625152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Mukherji A, Bailey SM, Staels B and

Baumert TF: The circadian clock and liver function in health and

disease. J Hepatol. 71:200–211. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Piggins HD: Human clock genes. Ann Med.

34:394–400. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cox KH and Takahashi JS: Circadian clock

genes and the transcriptional architecture of the clock mechanism.

J Mol Endocrinol. 63:R93–R102. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tsang AH, Sánchez-Moreno C, Bode B,

Rossner MJ, Garaulet M and Oster H: Tissue-specific interaction of

Per1/2 and Dec2 in the regulation of fibroblast circadian rhythms.

J Biol Rhythms. 27:478–489. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

González-Fernández B, Sánchez DI, Crespo

I, San-Miguel B, de Urbina JO, González-Gallego J and Tuñón MJ:

Melatonin attenuates dysregulation of the circadian clock pathway

in mice with CCl4-Induced fibrosis and human hepatic stellate

cells. Front Pharmacol. 9:5562018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen P, Kakan X, Wang S, Dong W, Jia A,

Cai C and Zhang J: Deletion of clock gene Per2 exacerbates

cholestatic liver injury and fibrosis in mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol.

65:427–432. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen P, Han Z, Yang P, Zhu L, Hua Z and

Zhang J: Loss of clock gene mPer2 promotes liver fibrosis induced

by carbon tetrachloride. Hepatol Res. 40:1117–1127. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Laitinen S, Fontaine C, Fruchart JC and

Staels B: The role of the orphan nuclear receptor Rev-Erb alpha in

adipocyte differentiation and function. Biochimie. 87:21–25. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cho H, Zhao X, Hatori M, Yu RT, Barish GD,

Lam MT, Chong LW, DiTacchio L, Atkins AR, Glass CK, et al:

Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-α and

REV-ERB-β. Nature. 485:123–127. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Stujanna EN, Murakoshi N, Tajiri K, Xu D,

Kimura T, Qin R, Feng D, Yonebayashi S, Ogura Y, Yamagami F, et al:

Rev-erb agonist improves adverse cardiac remodeling and survival in

myocardial infarction through an anti-inflammatory mechanism. PLoS

One. 12:e01893302017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ding G, Li X, Hou X, Zhou W, Gong Y, Liu

F, He Y, Song J, Wang J, Basil P, et al: REV-ERB in GABAergic

neurons controls diurnal hepatic insulin sensitivity. Nature.

592:763–767. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

da Rocha AL, Pinto AP, Bedo BLS, Morais

GP, Oliveira LC, Carolino ROG, Pauli JR, Simabuco FM, de Moura LP,

Ropelle ER, et al: Exercise alters the circadian rhythm of

REV-ERB-α and downregulates autophagy-related genes in peripheral

and central tissues. Sci Rep. 12:200062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Luo X, Song S, Qi L, Tien CL, Li H, Xu W,

Mathuram TL, Burris T, Zhao Y, Sun Z and Zhang L: REV-ERB is

essential in cardiac fibroblasts homeostasis. Front Pharmacol.

13:8996282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Griffin P, Dimitry JM and Musiek ES:

Rev-erbs and Glia-implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J

Exp Neurosci. 13:11790695198532332019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hu C, Zhao L, Tao J and Li L: Protective

role of melatonin in Early-stage and end-stage liver cirrhosis. J

Cell Mol Med. 23:7151–7162. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen L, Xia S, Wang F, Zhou Y, Wang S,

Yang T, Li Y, Xu M, Zhou Y, Kong D, et al: m6A methylation-induced

NR1D1 ablation disrupts the HSC circadian clock and promotes

hepatic fibrosis hepatic fibrosis. Pharmacol Res. 189:1067042023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang S, Lin Y, Yuan X, Li F, Guo L and Wu

B: REV-ERBα integrates colon clock with experimental colitis

through regulation of NF-κB/NLRP3 axis. Nat Commun. 9:42462018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tao Y, Wang N, Qiu T and Sun X: The Role

of Autophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome in liver fibrosis. Biomed Res

Int. 2020:72691502020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wree A, McGeough MD, Inzaugarat ME, Eguchi

A, Schuster S, Johnson CD, Peña CA, Geisler LJ, Papouchado BG,

Hoffman HM, et al: NLRP3 inflammasome driven liver injury and

fibrosis: Roles of IL-17 and TNF in mice. Hepatology. 67:736–749.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang K, Lin L, Zhu Y, Zhang N, Zhou M and

Li Y: Saikosaponin d alleviates liver fibrosis by negatively

regulating the ROS/NLRP3 inflammasome through activating the ERβ

pathway. Front Pharmacol. 13:8949812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shao R, Yang Y, Fan K, Wu X, Jiang R, Tang

L, Li L, Shen Y, Liu G and Zhang L: REV-ERBα Agonist GSK4112

attenuates Fas-induced Acute Hepatic Damage in Mice. Int J Med Sci.

18:3831–3838. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kim J, Park I, Jang S, Choi M, Kim D, Sun

W, Choe Y, Choi JW, Moon C, Park SH, et al: Pharmacological rescue

with SR8278, a circadian nuclear receptor REV-ERBα antagonist as a

therapy for mood disorders in Parkinson's disease.

Neurotherapeutics. 19:592–607. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kojetin D, Wang Y, Kamenecka TM and Burris

TP: Identification of SR8278, a synthetic antagonist of the nuclear

heme receptor REV-ERB. ACS Chem Biol. 6:131–134. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lin L, Zhou M, Que R, Chen Y, Liu X, Zhang

K, Shi Z and Li Y: Saikosaponin-d protects against liver fibrosis

by regulating the estrogen receptor-β/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway.

Biochem Cell Biol. 99:666–674. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yue J, He J, Wei Y, Shen K, Wu K, Yang X,

Liu S, Zhang C and Yang H: Decreased expression of Rev-Erbα in the

epileptic foci of temporal lobe epilepsy and activation of Rev-Erbα

have anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in the

pilocarpine model. J Neuroinflammation. 17:432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Niu WX, Bao YY, Zhang N, Lu ZN, Ge MX, Li

YM, Li Y, Chen MH and He HW: Dehydromevalonolactone ameliorates

liver fibrosis and inflammation by repressing activation of NLRP3

inflammasome. Bioorg Chem. 127:1059712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang X, Kuang G, Wan J, Jiang R, Ma L,

Gong X and Liu X: Salidroside protects mice against CCl4-induced

acute liver injury via down-regulating CYP2E1 expression and

inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Int Immunopharmacol.

85:1066622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kisseleva T and Brenner D: Molecular and

cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its regression. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 18:151–166. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Pan X, Mota S and Zhang B: Circadian clock

regulation on lipid metabolism and metabolic diseases. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1276:53–66. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bailey SM: Emerging role of circadian

clock disruption in Alcohol-induced liver disease. Am J Physiol

Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 315:G364–G373. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Richards J and Gumz ML: Advances in

understanding the peripheral circadian clocks. FASEB J.

26:3602–3613. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Horii R, Honda M, Shirasaki T, Shimakami

T, Shimizu R, Yamanaka S, Murai K, Kawaguchi K, Arai K, Yamashita

T, et al: MicroRNA-10a impairs liver metabolism in Hepatitis C

Virus-related cirrhosis through deregulation of the circadian clock

gene brain and Muscle Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear

Translocator-Like 1. Hepatol Commun. 3:1687–1703. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang D, Tong X, Nelson BB, Jin E, Sit J,

Charney N, Yang M, Omary MB and Yin L: The hepatic

BMAL1/AKT/lipogenesis axis protects against alcoholic liver disease

in mice via promoting PPARα pathway. Hepatology. 68:883–896. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Pan X, Queiroz J and Hussain MM:

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in CLOCK mutant mice. J Clin

Invest. 130:4282–4300. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhou B, Zhang Y, Zhang F, Xia Y, Liu J,

Huang R, Wang Y, Hu Y, Wu J, Dai C, et al: CLOCK/BMAL1 regulates

circadian change of mouse hepatic insulin sensitivity by SIRT1.

Hepatology. 59:2196–2206. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gnocchi D, Custodero C, Sabbà C and

Mazzocca A: Circadian rhythms: A possible new player in

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease pathophysiology. J Mol Med

(Berl). 97:741–759. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Forman BM, Chen J, Blumberg B, Kliewer SA,

Henshaw R, Ong ES and Evans RM: Cross-talk among ROR alpha 1 and

the Rev-erb family of orphan nuclear receptors. Mol Endocrinol.

8:1253–1261. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Le Martelot G, Claudel T, Gatfield D,

Schaad O, Kornmann B, Lo Sasso G, Moschetta A and Schibler U:

REV-ERBalpha participates in circadian SREBP signaling and bile

acid homeostasis. PLoS Biol. 7:e10001812009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhou D, Wang Y, Chen L, Jia L, Yuan J, Sun

M, Zhang W, Wang P, Zuo J, Xu Z and Luan J: Evolving roles of

circadian rhythms in liver homeostasis and pathology. Oncotarget.

7:8625–8639. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ni Y, Zhao Y, Ma L, Wang Z, Ni L, Hu L and

Fu Z: Pharmacological activation of REV-ERBα improves nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis by regulating intestinal permeability. Metabolism.

114:1544092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lin Y, Wang S, Gao L, Zhou Z, Yang Z, Lin

J, Ren S, Xing H and Wu B: Oscillating lncRNA Platr4 regulates

NLRP3 inflammasome to ameliorate nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in

mice. Theranostics. 11:426–444. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yu F, Wang Z, Zhang T, Chen X, Xu H, Wang

F, Guo L, Chen M, Liu K and Wu B: Deficiency of intestinal Bmal1

prevents obesity induced by high-fat feeding. Nat Commun.

12:53232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lin Y, Lin L, Gao L, Wang S and Wu B:

Rev-erbα regulates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 529:916–921. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Liu Q, Xu L, Wu M, Zhou Y, Yang J, Huang

C, Xu T, Li J and Zhang L: Rev-erbα exacerbates hepatic steatosis

in alcoholic liver diseases through regulating autophagy. Cell

Biosci. 11:1292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yang Z, Smalling RV, Huang Y, Jiang Y,

Kusumanchi P, Bogaert W, Wang L, Delker DA, Skill NJ, Han S, et al:

The role of SHP/REV-ERBα/CYP4A axis in the pathogenesis of

Alcohol-associated liver disease. JCI Insight. 6:e1406872021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang J, Yin L and Lazar MA: The orphan

nuclear receptor Rev-erb alpha regulates circadian expression of

plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. J Biol Chem.

281:33842–33848. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Crouchet E, Dachraoui M, Jühling F,

Roehlen N, Oudot MA, Durand SC, Ponsolles C, Gadenne C,

Meiss-Heydmann L, Moehlin J, et al: Targeting the liver clock

improves fibrosis by restoring TGF-β signaling. J Hepatol.

82:120–133. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Grant D, Yin L, Collins JL, Parks DJ,

Orband-Miller LA, Wisely GB, Joshi S, Lazar MA, Willson TM and

Zuercher WJ: GSK4112, a small molecule chemical probe for the cell

biology of the nuclear heme receptor Rev-erbα. ACS Chem Biol.

5:925–932. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Dong D, Sun H, Wu Z, Wu B, Xue Y and Li Z:

A validated ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass

spectrometry method to identify the pharmacokinetics of SR8278 in

normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Chromatogr B

Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 1020:142–147. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ishizuka T and Lazar MA: The N-CoR/histone

deacetylase 3 complex is required for repression by thyroid hormone

receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 23:5122–5131. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yin L and Lazar MA: The orphan nuclear

receptor Rev-erbalpha recruits the N-CoR/histone deacetylase 3

corepressor to regulate the circadian Bmal1 gene. Mol Endocrinol.

19:1452–1459. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yin L, Joshi S, Wu N, Tong X and Lazar MA:

E3 ligases Arf-bp1 and Pam mediate lithium-stimulated degradation

of the circadian heme receptor Rev-erb alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 107:11614–11619. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yin L, Wang J, Klein PS and Lazar MA:

Nuclear receptor Rev-erbalpha is a critical lithium-sensitive

component of the circadian clock. Science. 311:1002–1005. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Kisseleva T and Brenner DA: Hepatic

stellate cells and the reversal of fibrosis. J Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 21 (Suppl 3):S84–S87. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Liu XY, Liu RX, Hou F, Cui LJ, Li CY, Chi

C, Yi E, Wen Y and Yin CH: Fibronectin expression is critical for

liver fibrogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Mol Med Rep.

14:3669–3675. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Friedman SL: Hepatic stellate cells:

Protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol

Rev. 88:125–172. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Xiang D, Zou J, Zhu X, Chen X, Luo J, Kong

L and Zhang H: Physalin D attenuates hepatic stellate cell

activation and liver fibrosis by blocking TGF-β/Smad and YAP

signaling. Phytomedicine. 78:1532942020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Zhang J, Jiang N, Ping J and Xu L:

TGF-β1-induced autophagy activates hepatic stellate cells via the

ERK and JNK signaling pathways. Int J Mol Med. 47:256–266. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wu Z, Liao F, Luo G, Qian Y, He X, Xu W,

Ding S and Pu J: NR1D1 Deletion induces Rupture-prone vulnerable

plaques by regulating macrophage pyroptosis via the NF-κB/NLRP3

inflammasome pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021:52175722021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ka NL, Park MK, Kim SS, Jeon Y, Hwang S,

Kim SM, Lim GY, Lee H and Lee MO: NR1D1 Stimulates antitumor immune

responses in breast cancer by activating cGAS-STING signaling.

Cancer Res. 83:3045–3058. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Kou L, Chi X, Sun Y, Han C, Wan F, Hu J,

Yin S, Wu J, Li Y, Zhou Q, et al: The circadian clock protein

Rev-erbα provides neuroprotection and attenuates neuroinflammation

against Parkinson's disease via the microglial NLRP3 inflammasome.

J Neuroinflammation. 19:1332022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Huang ZN, Wang J, Wang ZY, Min LY, Ni HL,

Han YL, Tian YY, Cui YZ, Han JX and Cheng XF: SR9009 attenuates

inflammation-related NPMSC pyroptosis and IVDD through

NR1D1/NLRP3/IL-1β pathway. iScience. 27:1097332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|