The mitochondria are double-layered membrane

organelles composed of outer and inner membranes (foldable into

cristae), an inner membrane gap, matrix and mitochondrial DNA. They

mainly participate in energy metabolism, redox processes, calcium

ion (Ca2+) concentration regulation, cell apoptosis and

other cellular processes and serve a crucial role in maintaining

cellular homeostasis (1). The

outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) encloses the organelle, whereas

the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) forms intricate structures

known as cristae. The inner membrane cristae are involved in a wide

range of processes, including the electron transport chain, ATP

synthase, protein transport, metabolite exchange, protein

translation and degradation (2).

Protons and electrons can be distributed asymmetrically on both

sides of the membrane, resulting in a change in the membrane

potential and energy generation, thereby completing the cell energy

conversion. Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles

intrinsically linked to their function. There are several levels of

mitochondrial dynamics within a single mitochondrion, among

multiple mitochondria and between mitochondria and other organelles

(3). Mitochondria interact with

other cellular structures through contact points that facilitate

the transfer of ions, lipids, proteins or metabolites and regulate

mitochondrial dynamics, quality control and mitochondrial DNA

replication (4). The formation of

mitochondrial contact points is responsive to cellular and

metabolic states, which fine-tune the mitochondrial output in

numerous aspects. Crosstalk between organelles are essential for

numerous intracellular functions, with the

mitochondrial-endoplasmic reticulum (ER) axis exemplifying a

paradigmatic inter-organelle system (5,6). The

ER and mitochondria are physically interconnected, as demonstrated

by electron tomography, which reveals that these organelles are

adjoined by tethers and electron-dense structures (7,8).

Further research has revealed a protein complex that connects these

organelles (9).

Organelle dynamics, including mitochondrial

fission/fusion and ER-mitochondrial tethering, are critical for

maintaining cellular homeostasis through regulated oxidative

phosphorylation, ATP production, calcium storage and reactive

oxygen species. Mitochondrial dysfunction disrupts oxidative

phosphorylation and calcium handling, whilst ER stress induces

protein misfolding, exacerbating oxidative stress and apoptosis.

Emerging evidence highlights that ER-mitochondrial interorganellar

communication, particularly via inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

receptor (IP3R) type 1- voltage-dependent anion channel-1

(VDAC1)-glucose-regulated protein 75 (Grp75) complexes, directly

modulates calcium flux and apoptotic thresholds in cardiovascular

disease (CVD) pathogenesis (10–12).

Mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) are

crucial communication centers that facilitate the exchange of ions,

lipids, metabolites and signaling molecules (13). MAMs are maintained by interactions

between complementary tethering molecules located on their

surfaces. Several tethering proteins, such as VDAC1, Grp75 and

mitofusin-1/2, are crucial for the establishment and regulation of

this complex intracellular communication network and serve

essential roles in these interactions (14). Cellular physiology is coordinated

by the swift exchange of molecules between organelles at

specialized organelle-organelle contact sites (15). Numerous studies have demonstrated

that MAMs serve essential roles in calcium homeostasis, lipid

synthesis and transport and mitochondrial functions and homeostasis

(16–18). Additionally, these sites act as

signaling hubs for intracellular stress responses such as oxidative

stress, energy stress and stimulus signals (19). Moreover, MAMs are considered

pivotal sites for transmitting stress signals between the ER and

mitochondria. The cell fate also depends on these contact sites for

the decision between autophagy and apoptosis (20,21).

The interaction between organelles is a rapidly

emerging field that could allow the identification of key proteins,

help describe new regulatory pathways and clarify their

significance in CVD (22). Recent

research findings suggest that the pathogenic factors of CVD may

interfere with the interactions between mitochondria and other

organelles and the lack of specific functional proteins or

interactions involved in mitochondrial-organelle connections will

lead to several pathological changes in different tissues (23,24).

Understanding MAM proteins and their influence on cellular

physiological and pathological processes may help reveal their

diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Therefore, the present review

summarizes and discusses research progress on the interaction

between mitochondria and ER in CVD, specifically focusing on the

functional role and characteristics of MAM proteins in CVD.

Mitochondria are intimately juxtaposed to the ER and

their membrane contacts range from 10–50 nm in width, referred to

as MAMs or mitochondria-ER contacts (25). It has been observed that MAMs exist

in a wide range of species, from yeast to mammals. They facilitate

inter-organelle communication, help cells detect extracellular

signals and respond to stressful stimuli (26).

MAMs are integral to numerous cellular processes

such as lipid transport and synthesis, calcium exchange,

mitochondrial function and apoptosis/survival (26–28),

facilitated by protein complexes that exhibit both tethering

capabilities and specialized functions (29). MAM-localized proteins have been

categorized into three groups: i) MAM-specific proteins, (such as

the IP3R1-VDAC1-Grp75 complex, which directly mediates

ER-mitochondria calcium flux); ii) dual-organelle proteins [such as

phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein 2 (PACS-2), regulating

lipid transfer and mitophagy]; and iii) transient translocators

[such as σ-1 receptor (Sig-1R), dynamically adjusting MAM

organization under stress] (30,31).

Among these, six core protein complexes structurally organize MAMs

to mediate ER-mitochondria crosstalk: i) The IP3R1-VDAC1-Grp75

axis, critical for calcium signaling; ii) the vesicle-associated

membrane protein-associated protein B (VAPB)-protein tyrosine

phosphatase interacting protein 51 (PTPIP51) complex, integral to

the formation and stability of MAMs; iii) mitofusin 2 (Mfn2),

governing MAM structure and functional homeostasis; iv) PACS-2,

which binds to beclin 1 (BECN1) and mediates its relocation to the

MAM, facilitating MAM formation and mitophagy; v) Sig-1R, which

acts as a Ca2+-sensitive, ligand-operated chaperone; and

vi) mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system

(MICOS), which is evolutionarily conserved, connecting these inner

membrane domains by forming and stabilizing crista junctions

(Fig. 1).

In the context of the MAM, the most extensively

studied protein complexes related to the ER and mitochondria that

act as molecular tethers include IP3R1, VDAC1 and Grp75 (32). Structurally, IP3Rs serve as crucial

Ca2+ efflux channels on the ER membrane, facilitating

the transfer of Ca2+ from the ER lumen to the cytoplasm

(33). Voltage-dependent anion

channels (VDACs) are ion channels located on the OMM that regulate

the passage of metabolites and ions across the mitochondrial

membranes. Grp75 bridges IP3Rs and VDACs, thereby maintaining the

architecture of MAMs (34).

The VAPB-PTPIP51 complex is another important

component of MAMs. The membrane protein VAPB is located in the ER

membrane, whilst the membrane protein PTPIP51 is located in the

OMM. Together, VAPB and PTPIP51 are integral to the formation and

stability of MAMs (45). Emerging

evidence reveals that VAPB molecules can rapidly enter and exit

MAMs within seconds, allowing MAM to dynamically reshape according

to the intracellular and extracellular environment to precisely

regulate cellular metabolic demands. This demonstrates the critical

role of VAPB diffusion kinetics in maintaining MAMs homeostasis

(46). Oxysterol-binding

protein-related protein 5 is found at the interface and interacts

with OMM protein PTPIP51, thereby serving a role in mitochondrial

function (47). Following ischemic

stroke, the expression of VAPB-PTPIP51 is downregulated, which

damages the MAMs structure, potentially exacerbating cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting the phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase pathway and activating autophagy (48). Nucleoporin 358, a nucleoporin

resident in the annulate lamellae, can interact with the

VAPB-PTPIP51 complex, thereby suppressing the mTORC2/Akt/glycogen

synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) signaling pathway activation and

disrupting the MAMs (49). The

VAPB-PTPIP51 tethers also serve a crucial role in the regulation of

autophagy by mediating the transfer of Ca2+ from ER

stores to the mitochondria (50).

Additionally, neuronal protein α-synuclein interacts with the VAPB,

thereby disrupting MAMs and Ca2+ homeostasis, as well as

mitochondrial ATP production (51).

Mfn2-mediated MAM structure and functional

homeostasis are crucial for coordinating vital cellular homeostatic

processes. There are three main mechanisms by which the

mitochondrial dynamics protein Mfn2 affects MAMs are as follows: i)

It directly affects the linkage of MAMs; ii) it promotes

oligomerization; and iii) it facilitates the formation of complexes

with other proteins, thereby affecting MAMs linkages (52,53).

Splicing of Mfn2 produces ER-specific variants ERMIT2 and ERMIN2.

ERMIN2 regulates the morphology of the ER, whereas ERMIT2

associates with Mfn2 and engages with mitochondrial mitofusins to

facilitate the tethering of the ER to mitochondria. This

interaction promotes enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake

and phospholipid transfer (54).

The substantial expression of dimethylarginine

dimethylaminohydrolase-1 in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia

nigra may confer neuroprotective effects by sustaining the

formation of MAMs and preserving mitochondrial function through

oligomerization of Mfn2 (55).

Mfn2 not only mediates MAM formation but also regulates

mitochondria-ER interactions by binding to Diaphanous-1, modulating

MAM proximity and ischemia-reperfusion injury susceptibility

(56). Knocking out Mfn2 reduces

the interaction between the ER and mitochondria via the

VAPB-PTPIP51 tethering complex, whilst overexpressing Mfn2

increases the interaction (57).

PDZ-domain-containing protein synaptojanin-2 binding protein

(SYNJ2BP) maintains mitochondrial Zn2+ homeostasis in

nucleus pulposus cells during intervertebral disc degeneration by

stabilizing MAM contacts via Mfn2 and facilitating the formation of

the NOD-like receptor X1-the zinc transporter solute carrier family

39 member 7 complex (58). Mfn2

regulates protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

(PERK) and inositol-requiring enzyme 1 axis signaling and maintains

MAM integrity. Its deficiency disrupts MAM structure, inducing ER

stress, mitochondrial ROS accumulation and apoptosis in cisplatin

nephropathy (59). Exposure to

Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induces the downregulation of Mfn2,

which impairs MAMs by inhibiting Mfn2-PERK interaction (60). Conversely, skeletal muscle-specific

knockdown of the mitochondrial fusion mediator optic atrophy 1

(OPA1) upregulates Mfn2 but impairs MAM formation through

activating transcription factor 4-dependent mechanisms (61).

Rab32 is a small GTPase located in the ER and

mitochondria, where it regulates ER Ca2+ handling in the

ER and disrupts calnexin enrichment on MAM without affecting the ER

distribution of protein-disulfide isomerase or Mfn2. Furthermore,

Rab32 influences the targeting of protein kinase A to mitochondrial

and ER membranes, thereby regulating the phosphorylation of Bcl-2

agonist of cell death and dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)

(72). Moreover, Rab32 modulates

the positioning of the Ca2+ regulatory transmembrane

protein calnexin to MAM (72).

Thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 1 is selectively degraded

via a Rab32-dependent process with the long isoform of reticulon-3

(RTN3L) acting as a Rab32 effector. Together, Rab32 and RTN3L

promote autophagic degradation of the mitochondrial-proximal ER

membranes (73). Proteins in the

Rab32 subfamily, including Rab32A, Rab32B, Rab29 and Rab38, serve

an evolutionarily conserved role in interacting with Drp1, which is

essential for mitochondrial dynamics and dependent on their

localization in the ER and MAM (74).

The outer mitochondria membrane links the

mitochondria to other organelles, whereas the inner membrane

consists of a boundary region and a folded crista. The MICOS

system, which is evolutionarily conserved, connects these inner

membrane domains by forming and stabilizing crista junctions.

Moreover, MICOS creates contact sites between the inner and outer

membranes through interactions with outer membrane proteins

(75). Mitochondrial contact site

and cristae organizing system complex (Mic)19 forms the sorting and

assembly machinery (Sam) 50-Mic19-Mic60 axis by interacting with

Sam50 (the outer membrane protein) and Mic60 (the inner membrane

protein), linking the S-adenosylmethionine and MICOS

complexes to the MIB super complex that connects the mitochondrial

outer and inner membranes (76).

As a key MICOS subunit, Mic19 also regulates ER-mitochondria

contacts via the EMC2/SLC25A46/Mic19 pathway, with disruptions

potentially leading to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver

fibrosis (77).

ER and mitochondria are key sites for membrane

biogenesis in eukaryotes, facilitating lipid exchange through

membrane contact sites (78,79).

In yeast, this process is mediated by the endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondria encounter structure (ERMES) (9,80), a

complex composed of at least four proteins: The mitochondrial outer

membrane proteins (Mdm10 and Mdm34), the ER membrane component

(Mmm1) and the cytoplasmic protein (Mdm12). ERMES forms ~25

bridge-like complexes at contact sites, each featuring three

synaptotagmin-like domains in a zig-zag pattern (79). These ER-mitochondrial contact sites

are essential for importing hydrophobic mitochondrial precursor

proteins into the IMM through the ER- syndrome of undifferentiated

recurrent fever pathway. ERMES, in conjunction with translocase of

outer mitochondrial membrane 70 (Tom 70), Djp1 and Lam6, form two

parallel, partially redundant pathways for ER-to-mitochondrial

transport. Disruption of these contact sites results in several

mitochondrial inner membrane protein precursors becoming trapped in

the ER membrane, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction (81). Djp1, a chaperone involved in the

mitochondrial import of ER-resident proteins, is located near the

ER exit sites (ERES)-ERMES region, suggesting a potential link

between the proximity of ERES and ERMES and mitochondrial protein

import. Besides lipid transport, ERMES facilitates protein transfer

from the ER to mitochondria, overlapping with the function of the

Tom70-Djp1/Lam6 contact site (82). To date, ERMES components have only

been identified in fungi, to the best of the authors' knowledge

(83). Further investigations are

required to determine whether these proteins are involved in lipid

transfer in other species.

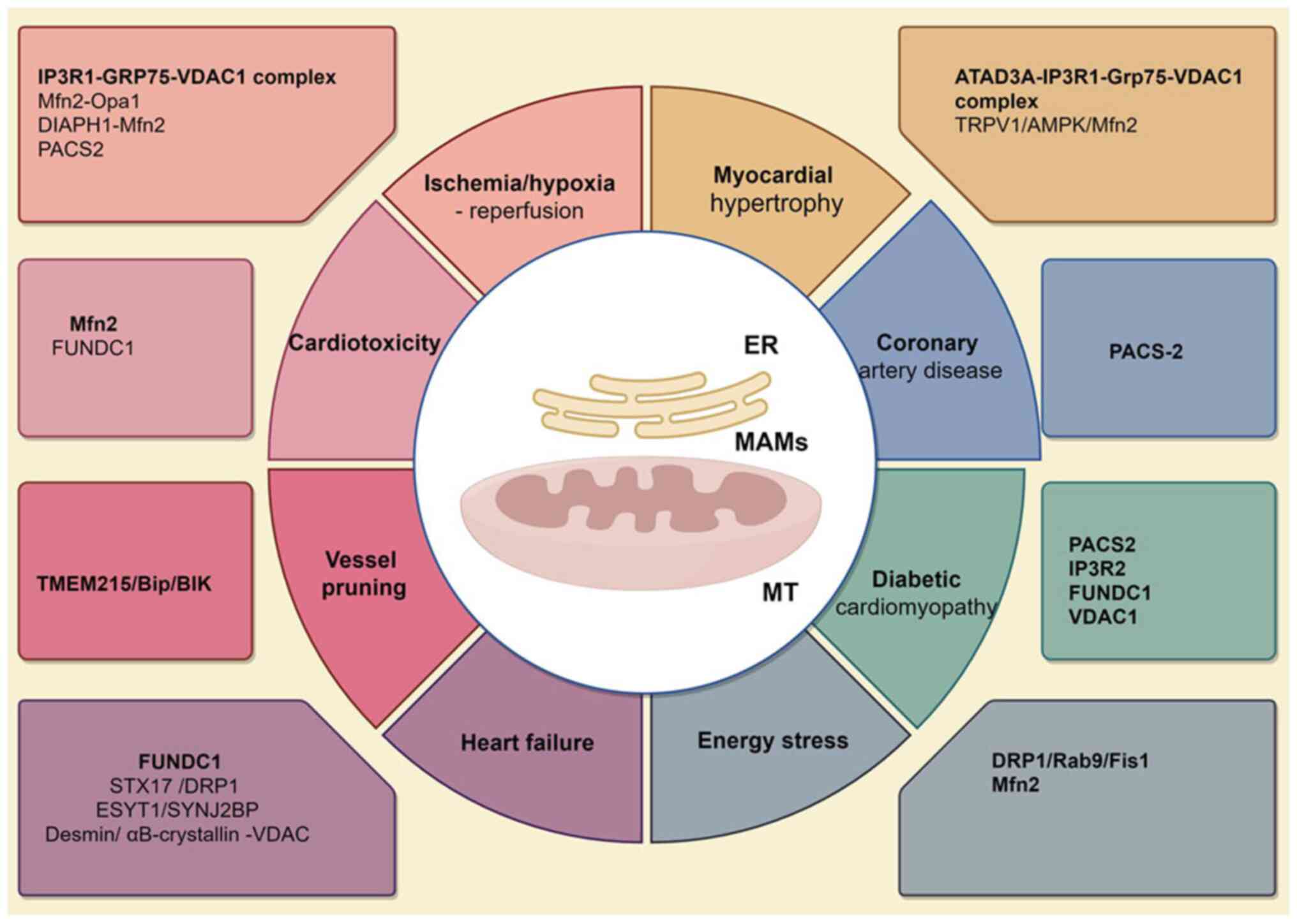

MAMs critically regulate pathological processes in

ischemic heart disease through coordinated control of calcium

homeostasis, mitochondrial dynamics and metabolic signaling. The

IP3R1-GRP75-VDAC1 complex serves as a central hub: GRP75 mediates

ER-mitochondrial tethering, enabling VDAC1-dependent calcium flux

that modulates apoptosis and glycolytic adaptation under hypoxia.

Experimental ablation of GRP75 disrupts this coupling, exacerbating

calcium overload and impairing adaptive stress responses in

cardiomyocytes (84).

GRP75-mediated ER-mitochondrial interactions via the IP3R1-VDAC1

complex are essential for Ca2+ homeostasis and ER stress

adaptation in cardiomyocyte hypoxia-ischemia. Targeting GRP75

regulates Ca2+ flux, glycolysis and cell survival

(38). In pulmonary hypertension,

downregulation of OPA1/Mfn2 impairs mitochondrial fusion,

accelerating right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy via reactive oxygen

species overproduction, whereas their overexpression preserves

mitochondrial integrity and attenuates maladaptive remodeling

(85). Diaphanous related formin 1

(DIAPH1)-Mfn2 interaction governs MAM architecture by regulating

ER-mitochondrial proximity, as synthetic linkers disrupting this

interaction negate the silencing of the DIAPH1 cardioprotective

effects during ischemia (86).

CypD-VDAC1/GRP75/IP3R1 complex dynamics further fine-tune calcium

transfer, with hypoxia-reoxygenation enhancing CypD binding to

amplify mitochondrial calcium overload, making this complex a

therapeutic target for reperfusion injury (87). Finally, Pacs2 deficiency disrupts

MAM-mediated mitophagy and energy metabolism, exacerbating RV

dysfunction in hypobaric hypoxia, whilst Pacs2 overexpression

restores calcium flux and mitophagic flux, highlighting its role as

a metabolic checkpoint (88).

ATPase family AAA-domain containing protein 3A

(ATAD3A), which is located in the MAM, maintains ER-mitochondrial

contact homeostasis, prevents mitochondrial Ca2+

overload and protects the mitochondrial bioenergetics from ER

stress. It is a substrate of sirtuin 3 and its acetylation at K134

disrupts its oligomerization. ATAD3A monomer interacts with the

IP3R1-GRP75-VDAC1 complex, leading to mitochondrial Ca2+

overload and dysfunction in myocardial hypertrophy (29). A nonselective cation channel,

transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1, enhances the

formation of MAMs and maintains mitochondrial function through the

AMP/APK/Mfn2 pathway, reducing myocardial hypertrophy caused by

pressure overload in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2) (89).

Sorafenib (SOR), a first-line drug for the treatment

of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, induces cardiac dysfunction

via mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, activating

calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II δ (CaMKIIδ) and the

receptor interacting protein 3 (RIP3)/mixed lineage kinase

domain-like protein (MLKL) cascade, with excessive MAM formation

and tight ER-mitochondria contact serving as the key pathogenic

mechanisms (90). SOR also

downregulates Mfn2 expression. Lowering Mfn2 enhances SOR-induced

MAM biosynthesis and mitochondrial MAM binding in cardiomyocytes.

Furthermore, SOR inactivates mTOR, activated transcription factor

EB and promotes mitochondrial phagocytosis and Mfn2 degradation.

Sorafenib triggers necroptosis through the

Mfn2-MAM-Ca2+-CaMKIIδ pathway, but Mfn2 overexpression

prevents cardiac dysfunction and necroptosis caused by sorafenib by

blocking the MAM-CaMKIIδ-RIP3/MLKL pathway (90). Upon tunicamycin treatment, the

oxidoreductase ER oxidoreductase 1 α (ERO1α) has been reported to

form a covalent bond with the protein kinase PERK, which requires

the C-terminal active site of ERO1α and cysteine 216 of PERK. This

interaction oxidizes MAMs and regulates mitochondrial dynamics,

enhancing ER-mitochondria Ca2+ flux to maintain

bioenergetics and reduce oxidative stress (91). MAMs initiate autophagy and form

autophagosomes, whilst FUN14 domain containing 1 (FUNDC1) acts as a

tethering protein. Overexpression of FUNDC1 is reported to restore

autophagosome biogenesis by maintaining the MAM structure and

aiding in the formation of the autophagy-related

(ATG)5-ATG12/ATG16L1 complex without affecting mitophagy (92). FUNDC1 also reduces doxorubicin

(DOX)-induced oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte death through

autophagy. Therefore, FUNDC1-mediated MAMs provide

cardio-protection against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by restoring

autophagosome biogenesis (Fig.

2).

In patients with coronary heart disease, the

mitochondria exhibit increased oxygen consumption, higher ATP

production and tighter connections with the ER, thereby forming

MAMs. This Ca2+ transfer through MAMs sustains

mitochondrial hyperactivity and is dependent on the inactivation of

GSK3β (93). Moulis et al

(66) reported that PACS-2

accumulates at MAM sites in VSMCs exposed to oxidized low-density

lipoprotein. PACS-2 enhances MAM contacts and its deletion disrupts

these connections, leading to impaired mitophagosome formation and

enhanced VSMC apoptosis. Further research by Assis et al

(94) reported that Pravastatin

reduces ER-mitochondrial interactions, leading to increased

mitochondrial branching. Moreover, Pravastatin upregulated the

expression of the mitochondrial dynamics regulators fission 1

protein (Fis1) and Mfn2 in bone marrow-derived macrophage from

Ldlr−/− mice. Mendelian randomization-transcriptomic

analysis further identified MAM-related KLRC1/SOCS2 as protective

AS resistance genes with reduced expression in atherosclerotic

plaques (Fig. 2) (95).

Under high glucose conditions, the formation of MAMs

is markedly increased through the involvement of PACS2, IP3R2,

FUNDC1 and VDAC1 in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts. This increase in MAMs

coincides with decreased mitochondrial biogenesis, fusion and

oxidative phosphorylation. However, ferulic acid has been reported

to effectively counteract changes in MAM formation and the

associated cellular dysfunction (102). IP3R1-GRP75-VDAC1 complex mediates

ER-mitochondrial calcium dysregulation, driving atrial remodeling

and atrial fibrillation in type 2 diabetes mellitus via exacerbated

oxidative stress. GRP75 ablation attenuates these pathological

processes in diabetic rat and cell models, identifying this complex

as a therapeutic target for diabetes-associated atrial fibrillation

(103).

Transmembrane protein 215 (TMEM215) is a two-pass

protein located in the ER. Knockdown of TMEM215 in endothelial

cells triggers apoptosis. TMEM215 interacts with chaperone-BiP and

facilitates its interaction with the pro-apoptotic protein BCL-2

interacting killer (BIK). Reducing TMEM215 levels increases the

number and proximity of mitochondria-associated ER membranes,

leading to enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ influx. It also

reduces the distance between MAMs, leading to a higher

mitochondrial Ca2+ influx. TMEM215, induced by shear

stress through enhancer of zeste homolog 2 downregulation,

safeguards endothelial cells from BIK-induced mitochondrial

apoptosis via Ca2+ influx during vessel pruning

(Fig. 2) (104).

During the chronic phase of HFD consumption, DRP1 is

phosphorylated at Ser616, localizes to MAMs and interacts with Rab9

and Fis1. By contrast, during the acute phase, DRP1 regulates

mitophagy independently of MAMs (105). Under energy stress, AMPK

translocated from the cytosol to MAMs and mitochondria during

mitochondrial fission, where it directly interacts with Mfn2.

Mfn2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) have

been reported to exhibit notably reduced autophagic ability under

energy stress compared with wildtype MEFs, but re-expressing Mfn2

restored their autophagy. Furthermore, Mfn2−/−

cells were reported to have a markedly lower abundance of MAMs

compared to control (17).

The emerging evidence emphasizes that the MAM is a

key hub for cellular homeostasis, integrating lipid metabolism,

calcium signaling (IP3R-VDAC1-Grp75 complex) and mitochondrial

dynamics (MFN2-mediated binding and Drp1-regulated fission)

(16). The existing research

results indicate that MAM dysfunction serves a key role in the

pathogenesis of CVD, particularly through mechanisms involving ER

mitochondrial calcium overload and lipid toxicity induced membrane

remodeling (107,108).

There are still three limitations of the present

review: i) The complexity of MAM regulatory networks: Current

models inadequately capture the multi-layered regulation of MAM

integrity. Whilst canonical pathways (such as Sig-1R-mediated ER

stress modulation) have been characterized, systemic

interconnections between MAM signaling nodes remain poorly defined;

ii) Causal inference in MAM-CVD relationships: Despite robust

associative data linking MAM disruption with CVD phenotypes, causal

validation remains elusive. The need for cell-type-specific MAM

editing tools (such as CRISPRa/i in human induced cardiomyocytes)

to dissect tissue-specific patho-mechanisms; and iii) Translational

barriers in MAM-targeted therapeutics: The MAM simultaneously

participates in pathways such as calcium signaling

(IP3R-VDAC1-GRP75), lipid metabolism (Sig-1R-ER stress) and

mitochondrial dynamics (MFN2-mediated mitochondrial anchoring).

Targeting a single node may trigger compensatory feedback.

The future directions of MAMs in CVD include: i)

Dynamic MAM profiling, with implementation of live-cell

super-resolution imaging (such as lattice light-sheet microscopy)

to resolve MAM remodeling kinetics during CVDs; ii) multi-omic

integration, with the combining of spatial lipidomics with

proximity-dependent biotinylation (BioID2) to construct

disease-specific MAM interaction networks; and iii) organoid

models, where patient-derived cardiac organoids are developed with

engineered MAM architectures to test genotype-specific

therapies.

In conclusion, while the present MAM research

provides potential for CVD treatment, bridging molecular mechanisms

to clinical applications requires addressing methodological

heterogeneity, refining causal inference frameworks and innovating

organelle-specific delivery platforms. The present review

highlighted the urgency of establishing standardized MAM assessment

protocols to accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The present study was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82100475), Sichuan Science and

Technology Program (grant no. 2023NSFSC0617) and Chengdu Women's

and Children's Central Hospital Talent Program (grant nos.

YC2021003 and YC2022002).

Not applicable.

SX and YL contributed to conceptualization. SX, YL

and XG contributed to the methodology. The formal analysis,

investigation and preparation of the original draft was performed

by YL and XG. The review and editing of the manuscript, acquisition

of funding and supervision was performed by SX. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Suomalainen A and Nunnari J: Mitochondria

at the crossroads of health and disease. Cell. 187:2601–2627. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Caron C and Bertolin G: Cristae shaping

and dynamics in mitochondrial function. J Cell Sci.

137:jcs2609862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kondadi AK and Reichert AS: Mitochondrial

dynamics at different levels: From cristae dynamics to

interorganellar cross talk. Annu Rev Biophys. 53:147–168. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhang Y, Wu Y, Zhang M, Li Z, Liu B, Liu

H, Hao J and Li X: Synergistic mechanism between the endoplasmic

reticulum and mitochondria and their crosstalk with other

organelles. Cell Death Discov. 9:512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wu H, Chen W, Chen Z, Li X and Wang M:

Novel tumor therapy strategies targeting endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondria signal pathways. Ageing Res Rev.

88:1019512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Daw CC, Ramachandran K, Enslow BT, Maity

S, Bursic B, Novello MJ, Rubannelsonkumar CS, Mashal AH,

Ravichandran J, Bakewell TM, et al: Lactate elicits

ER-mitochondrial Mg(2+) dynamics to integrate cellular metabolism.

Cell. 183:474–489. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mannella CA, Buttle K, Rath BK and Marko

M: Electron microscopic tomography of rat-liver mitochondria and

their interaction with the endoplasmic reticulum. Biofactors.

8:225–228. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Csordas G, Renken C, Varnai P, Walter L,

Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA and Hajnóczky G:

Structural and functional features and significance of the physical

linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 174:915–921.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kornmann B, Currie E, Collins SR,

Schuldiner M, Nunnari J, Weissman JS and Walter P: An

ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology

screen. Science. 325:477–481. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Giacomello M, Pyakurel A, Glytsou C and

Scorrano L: The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:204–224. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ali MA, Gioscia-Ryan R, Yang D, Sutton NR

and Tyrrell DJ: Cardiovascular aging: Spotlight on mitochondria. Am

J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 326:H317–H333. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen Z and Zhang SL: Endoplasmic reticulum

stress: A key regulator of cardiovascular disease. DNA Cell Biol.

42:322–335. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hernandez-Alvarez MI, Sebastian D, Vives

S, Ivanova S, Bartoccioni P, Kakimoto P, Plana N, Veiga SR,

Hernández V, Vasconcelos N, et al: Deficient endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondrial phosphatidylserine transfer causes liver

disease. Cell. 177:881–895. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mao H, Chen W, Chen L and Li L: Potential

role of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane

proteins in diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 199:1150112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Salvador-Gallego R, Hoyer MJ and Voeltz

GK: SnapShot: Functions of endoplasmic reticulum membrane contact

sites. Cell. 171:1224. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhao WB and Sheng R: The correlation

between mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes

(MAMs) and Ca(2+) transport in the pathogenesis of diseases. Acta

Pharmacol Sin. 46:271–291. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang N, Wang C, Zhao H, He Y, Lan B, Sun L

and Gao Y: The MAMs structure and its role in cell death. Cells.

10:6572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Barbuti PA, Guardia-Laguarta C, Yun T,

Chatila ZK, Flowers X, Santos BF, Larsen SB, Hattori N, Bradshaw E,

Dettmer U, et al: The role of alpha-synuclein in synucleinopathy:

Impact on lipid regulation at mitochondria-ER membranes. NPJ

Parkinsons Dis. 11:1032025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Elwakiel A, Mathew A and Isermann B: The

role of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria-associated membranes in

diabetic kidney disease. Cardiovasc Res. 119:2875–2883. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hu Y, Chen H, Zhang L, Lin X, Li X, Zhuang

H, Fan H, Meng T, He Z, Huang H, et al: The AMPK-MFN2 axis

regulates MAM dynamics and autophagy induced by energy stresses.

Autophagy. 17:1142–1156. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cao Y, Chen Z, Hu J, Feng J, Zhu Z, Fan Y,

Lin Q and Ding G: Mfn2 regulates high glucose-induced MAMs

dysfunction and apoptosis in podocytes via PERK pathway. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 9:7692132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yao H, Xie Y, Li C, Liu W and Yi G:

Mitochondria-Associated organelle crosstalk in myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 17:1106–1118.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang M, Ding Y, Hu Y and Li Z, Luo W, Liu

P and Li Z: SIRT3 improved peroxisomes-mitochondria interplay and

prevented cardiac hypertrophy via preserving PEX5 expression. Redox

Biol. 62:1026522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hu L, Tang D, Qi B, Guo D, Wang Y, Geng J,

Zhang X, Song L, Chang P, Chen W, et al: Mfn2/Hsc70 complex

mediates the formation of mitochondria-lipid droplets membrane

contact and regulates myocardial lipid metabolism. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e23077492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Vance JE: MAM (mitochondria-associated

membranes) in mammalian cells: Lipids and beyond. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1841:595–609. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lang A, Peter AT and Kornmann B:

ER-mitochondria contact sites in yeast: Beyond the myths of ERMES.

Curr Opin Cell Biol. 35:7–12. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Naon D and Scorrano L: At the right

distance: ER-mitochondria juxtaposition in cell life and death.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1843:2184–2194. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Prudent J and McBride HM: The

mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum contact sites: A signalling

platform for cell death. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 47:52–63. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Barazzuol L, Giamogante F and Cali T:

Mitochondria associated membranes (MAMs): Architecture and

physiopathological role. Cell Calcium. 94:1023432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Poston CN, Krishnan SC and Bazemore-Walker

CR: In-depth proteomic analysis of mammalian

mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM). J Proteomics. 79:219–230.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang X, Wen Y, Dong J, Cao C and Yuan S:

Systematic in-depth proteomic analysis of mitochondria-associated

endoplasmic reticulum membranes in mouse and human testes.

Proteomics. 18:e17004782018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li Z, Hu O, Xu S, Lin C, Yu W, Ma D, Lu J

and Liu P: The SIRT3-ATAD3A axis regulates MAM dynamics and

mitochondrial calcium homeostasis in cardiac hypertrophy. Int J

Biol Sci. 20:831–847. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Woll KA and Van Petegem F: Calcium-release

channels: Structure and function of IP(3) receptors and ryanodine

receptors. Physiol Rev. 102:209–268. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Massa R, Marliera LN, Martorana A, Cicconi

S, Pierucci D, Giacomini P, De Pinto V and Castellani L:

Intracellular localization and isoform expression of the

voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) in normal and dystrophic

skeletal muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 21:433–442. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yu F, Courjaret R, Assaf L, Elmi A, Hammad

A, Fisher M, Terasaki M and Machaca K: Mitochondria-ER contact

sites expand during mitosis. iScience. 27:1093792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Narayanan D, Adebiyi A and Jaggar JH:

Inositol trisphosphate receptors in smooth muscle cells. Am J

Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 302:H2190–H2210. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Garcia MI and Boehning D: Cardiac inositol

1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res.

1864:907–914. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kim JC, Son MJ, Subedi KP, Li Y, Ahn JR

and Woo SH: Atrial local Ca2+ signaling and inositol

1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 103:59–70.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Nandwani A, Rathore S and Datta M: LncRNA

H19 inhibition impairs endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contact

in hepatic cells and augments gluconeogenesis by increasing VDAC1

levels. Redox Biol. 69:1029892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Honrath B, Metz I, Bendridi N, Rieusset J,

Culmsee C and Dolga AM: Glucose-regulated protein 75 determines

ER-mitochondrial coupling and sensitivity to oxidative stress in

neuronal cells. Cell Death Discov. 3:170762017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang C, Liu B, Sheng J, Wang J, Zhu W,

Xie C, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Meng Q and Li Y: Potential targets for the

treatment of MI: GRP75-mediated Ca(2+) transfer in MAM. Eur J

Pharmacol. 971:1765302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li Y, Zhu L, Cai MX, Wang ZL, Zhuang M,

Tan CY, Xie TH, Yao Y and Wei TT: TGR5 supresses cGAS/STING pathway

by inhibiting GRP75-mediated endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial

coupling in diabetic retinopathy. Cell Death Dis. 14:5832023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Basso V, Marchesan E and Ziviani E: A trio

has turned into a quartet: DJ-1 interacts with the IP3R-Grp75-VDAC

complex to control ER-mitochondria interaction. Cell Calcium.

87:1021862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Liu Y, Ma X, Fujioka H, Liu J, Chen S and

Zhu X: DJ-1 regulates the integrity and function of ER-mitochondria

association through interaction with IP3R3-Grp75-VDAC1. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 116:25322–25328. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Jiang T, Ruan N, Luo P, Wang Q, Wei X, Li

Y, Dai Y, Lin L, Lv J, Liu Y and Zhang C: Modulation of

ER-mitochondria tethering complex VAPB-PTPIP51: Novel therapeutic

targets for aging-associated diseases. Ageing Res Rev.

98:1023202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Obara CJ, Nixon-Abell J, Moore AS, Riccio

F, Hoffman DP, Shtengel G, Xu CS, Schaefer K, Pasolli HA, Masson

JB, et al: Motion of VAPB molecules reveals ER-mitochondria contact

site subdomains. Nature. 626:169–176. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Galmes R, Houcine A, van Vliet AR,

Agostinis P, Jackson CL and Giordano F: ORP5/ORP8 localize to

endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts and are involved in

mitochondrial function. EMBO Rep. 17:800–810. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Li M, Zhang Y, Yu G, Gu L, Zhu H, Feng S,

Xiong X and Jian Z: Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum

membranes tethering protein VAPB-PTPIP51 protects against ischemic

stroke through inhibiting the activation of autophagy. CNS Neurosci

Ther. 30:e147072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kalarikkal M, Saikia R, Oliveira L,

Bhorkar Y, Lonare A, Varshney P, Dhamale P, Majumdar A and Joseph

J: Nup358 restricts ER-mitochondria connectivity by modulating

mTORC2/Akt/GSK3β signalling. EMBO Rep. 25:4226–4251. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Gomez-Suaga P, Paillusson S, Stoica R,

Noble W, Hanger DP and Miller CCJ: The ER-mitochondria tethering

complex VAPB-PTPIP51 regulates autophagy. Curr Biol. 27:371–385.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Paillusson S, Gomez-Suaga P, Stoica R,

Little D, Gissen P, Devine MJ, Noble W, Hanger DP and Miller CCJ:

α-Synuclein binds to the ER-mitochondria tethering protein VAPB to

disrupt Ca2+ homeostasis and mitochondrial ATP

production. Acta Neuropathol. 134:129–149. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

de Brito OM and Scorrano L: Mitofusin 2

tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 456:605–610.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang T, Zhu Q, Cao B, Cai Y, Wen S, Bian

J, Zou H, Song R, Gu J, Liu X, et al: Ca2+ transfer via

the ER-mitochondria tethering complex in neuronal cells contribute

to cadmium-induced autophagy. Cell Biol Toxicol. 38:469–485. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Naon D, Hernandez-Alvarez MI, Shinjo S,

Wieczor M, Ivanova S, de Brito OM, Quintana A, Hidalgo J, Palacín

M, Aparicio P, et al: Splice variants of mitofusin 2 shape the

endoplasmic reticulum and tether it to mitochondria. Science.

380:eadh93512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhao Y, Shen W, Zhang M, Guo M, Dou Y, Han

S, Yu J, Cui M and Zhao Y: DDAH-1 maintains endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondria contacts and protects dopaminergic neurons

in Parkinson's disease. Cell Death Dis. 15:3992024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Kirshenbaum LA, Dhingra R, Bravo-Sagua R

and Lavandero S: DIAPH1-MFN2 interaction decreases the endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondrial distance and promotes cardiac injury

following myocardial ischemia. Nat Commun. 15:14692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Han S, Zhao F, Hsia J, Ma X, Liu Y, Torres

S, Fujioka H and Zhu X: The role of Mfn2 in the structure and

function of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial tethering in vivo.

J Cell Sci. 134:jcs2534432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Song Y, Geng W, Zhu D, Liang H, Du Z, Tong

B, Wang K, Li S, Gao Y, Feng X, et al: SYNJ2BP ameliorates

intervertebral disc degeneration by facilitating

mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane formation

and mitochondrial Zn(2+) homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med.

212:220–233. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Liu YT, Zhang H, Duan SB, Wang JW, Chen H,

Zhan M, Zhang W, Li AM, Liu Y, Yang Y and Yang S: Mitofusin2

ameliorated endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial reactive

oxygen species through maintaining mitochondria-associated

endoplasmic reticulum membrane integrity in cisplatin-induced acute

kidney injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 40:16–39. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhao Y, Chang YH, Ren HR, Lou M, Jiang FW,

Wang JX, Chen MS, Liu S, Shi YS, Zhu HM and Li JL: Phthalates

induce neurotoxicity by disrupting the Mfn2-PERK axis-mediated

endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interaction. J Agric Food Chem.

72:7411–7422. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Hinton A Jr, Katti P, Mungai M, Hall DD,

Koval O, Shao J, Vue Z, Lopez EG, Rostami R, Neikirk K, et al:

ATF4-dependent increase in mitochondrial-endoplasmic reticulum

tethering following OPA1 deletion in skeletal muscle. J Cell

Physiol. 239:e312042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

van Vliet AR, Verfaillie T and Agostinis

P: New functions of mitochondria associated membranes in cellular

signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1843:2253–2262. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Xue M, Fang T, Sun H, Cheng Y, Li T, Xu C,

Tang C, Liu X, Sun B and Chen L: PACS-2 attenuates diabetic kidney

disease via the enhancement of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic

reticulum membrane formation. Cell Death Dis. 12:11072021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Li C, Li L, Yang M, Yang J, Zhao C, Han Y,

Zhao H, Jiang N, Wei L, Xiao Y, et al: PACS-2 Ameliorates tubular

injury by facilitating endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contact

and mitophagy in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 71:1034–1050.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Liu S, Han S, Wang C, Chen H, Xu Q, Feng

S, Wang Y, Yao J, Zhou Q, Tang X, et al: MAPK1 mediates MAM

disruption and mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease

via the PACS-2-dependent mechanism. Int J Biol Sci. 20:569–584.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Moulis M, Grousset E, Faccini J, Richetin

K, Thomas G and Vindis C: The multifunctional sorting protein

PACS-2 controls mitophagosome formation in human vascular smooth

muscle cells through mitochondria-ER contact sites. Cells.

8:6382019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Hayashi T and Su TP: Sigma-1 receptor

chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+)

signaling and cell survival. Cell. 131:596–610. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Leonard A, Grose V, Paton AW, Paton JC,

Yule DI, Rahman A and Fazal F: Selective inactivation of

intracellular BiP/GRP78 attenuates endothelial inflammation and

permeability in acute lung injury. Sci Rep. 9:20962019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Hayashi T, Lewis A, Hayashi E, Betenbaugh

MJ and Su TP: Antigen retrieval to improve the immunocytochemistry

detection of sigma-1 receptors and ER chaperones. Histochem Cell

Biol. 135:627–637. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Mahamed Z, Shadab M, Najar RA, Millar MW,

Bal J, Pressley T and Fazal F: The protective role of

mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM)

protein sigma-1 receptor in regulating endothelial inflammation and

permeability associated with acute lung injury. Cells. 13:52023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhang Z, Zhou H, Gu W, Wei Y, Mou S, Wang

Y, Zhang J and Zhong Q: CGI1746 targets σ1R to modulate

ferroptosis through mitochondria-associated membranes. Nat Chem

Biol. 20:699–709. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Bui M, Gilady SY, Fitzsimmons RE, Benson

MD, Lynes EM, Gesson K, Alto NM, Strack S, Scott JD and Simmen T:

Rab32 modulates apoptosis onset and mitochondria-associated

membrane (MAM) properties. J Biol Chem. 285:31590–31602. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Herrera-Cruz MS, Yap MC, Tahbaz N,

Phillips K, Thomas L, Thomas G and Simmen T: Rab32 uses its

effector reticulon 3L to trigger autophagic degradation of

mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) proteins. Biol Direct.

16:222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Ortiz-Sandoval CG, Hughes SC, Dacks JB and

Simmen T: Interaction with the effector dynamin-related protein 1

(Drp1) is an ancient function of Rab32 subfamily proteins. Cell

Logist. 4:e9863992014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Rampelt H, Zerbes RM, van der Laan M and

Pfanner N: Role of the mitochondrial contact site and cristae

organizing system in membrane architecture and dynamics. Biochim

Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1864:737–746. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Tang J, Zhang K, Dong J, Yan C, Hu C, Ji

H, Chen L, Chen S, Zhao H and Song Z: Sam50-Mic19-Mic60 axis

determines mitochondrial cristae architecture by mediating

mitochondrial outer and inner membrane contact. Cell Death Differ.

27:146–160. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Dong J, Chen L, Ye F, Tang J, Liu B, Lin

J, Zhou PH, Lu B, Wu M, Lu JH, et al: Mic19 depletion impairs

endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial contacts and mitochondrial

lipid metabolism and triggers liver disease. Nat Commun.

15:1682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Vance JE: Phospholipid synthesis in a

membrane fraction associated with mitochondria. J Biol Chem.

265:7248–7256. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Wozny MR, Di Luca A, Morado DR, Picco A,

Khaddaj R, Campomanes P, Ivanović L, Hoffmann PC, Miller EA, Vanni

S and Kukulski W: In situ architecture of the ER-mitochondria

encounter structure. Nature. 618:188–192. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Peter AT, Petrungaro C, Peter M and

Kornmann B: METALIC reveals interorganelle lipid flux in live cells

by enzymatic mass tagging. Nat Cell Biol. 24:996–1004. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Koch C, Lenhard S, Raschle M,

Prescianotto-Baschong C, Spang A and Herrmann JM: The ER-SURF

pathway uses ER-mitochondria contact sites for protein targeting to

mitochondria. EMBO Rep. 25:2071–2096. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Chakraborty N, Jain BK, Shembekar S and

Bhattacharyya D: ER exit sites (ERES) and ER-mitochondria encounter

structures (ERMES) often localize proximally. FEBS Lett.

597:320–336. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Cheema JY, He J, Wei W and Fu C: The

endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria encounter structure and its

regulatory proteins. Contact (Thousand Oaks).

4:251525642110644912021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Varnai P, De

Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, Nagy AI, Balla T and Rizzuto

R: Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and

mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol. 175:901–911. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Luo F, Fu M, Wang T, Qi Y, Zhong X, Li D

and Liu B: Down-regulation of the mitochondrial fusion protein

Opa1/Mfn2 promotes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in

Su5416/hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension rats. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 747:1097432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Yepuri G, Ramirez LM, Theophall GG,

Reverdatto SV, Quadri N, Hasan SN, Bu L, Thiagarajan D, Wilson R,

Díez RL, et al: DIAPH1-MFN2 interaction regulates

mitochondria-SR/ER contact and modulates ischemic/hypoxic stress.

Nat Commun. 14:69002023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Paillard M, Tubbs E, Thiebaut PA, Gomez L,

Fauconnier J, Da Silva CC, Teixeira G, Mewton N, Belaidi E, Durand

A, et al: Depressing mitochondria-reticulum interactions protects

cardiomyocytes from lethal hypoxia-reoxygenation injury.

Circulation. 128:1555–1565. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Yang J, Sun M, Chen R, Ye X, Wu B, Liu Z,

Zhang J, Gao X, Cheng R, He C, et al: Mitochondria-associated

membrane protein PACS2 maintains right cardiac function in

hypobaric hypoxia. iScience. 26:1063282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wang Y, Li X, Xu X, Qu X and Yang Y:

Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 protects against

pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy by promoting

mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes. J

Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 80:430–441. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Song Z, Song H, Liu D, Yan B, Wang D,

Zhang Y, Zhao X, Tian X, Yan C and Han Y: Overexpression of MFN2

alleviates sorafenib-induced cardiomyocyte necroptosis via the

MAM-CaMKIIdelta pathway in vitro and in vivo. Theranostics.

12:1267–1285. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Bassot A, Chen J, Takahashi-Yamashiro K,

Yap MC, Gibhardt CS, Le GNT, Hario S, Nasu Y, Moore J, Gutiérrez T,

et al: The endoplasmic reticulum kinase PERK interacts with the

oxidoreductase ERO1 to metabolically adapt mitochondria. Cell Rep.

42:1118992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

He W, Sun Z, Tong G, Zeng L, He W, Chen X,

Zhen C, Chen P, Tan N and He P: FUNDC1 alleviates

doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by restoring

mitochondrial-endoplasmic reticulum contacts and blocked autophagic

flux. Theranostics. 14:3719–3738. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Zeisbrich M, Yanes RE, Zhang H, Watanabe

R, Li Y, Brosig L, Hong J, Wallis BB, Giacomini JC and Assimes TL:

Hypermetabolic macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis and coronary

artery disease due to glycogen synthase kinase 3b inactivation. Ann

Rheum Dis. 77:1053–1062. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Assis LHP, Dorighello GG, Rentz T, de

Souza JC, Vercesi AE and de Oliveira HCF: In vivo pravastatin

treatment reverses hypercholesterolemia induced

mitochondria-associated membranes contact sites, foam cell

formation, and phagocytosis in macrophages. Front Mol Biosci.

9:8394282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Wang LR, Zhang CX, Tian LB, Huang J, Jia

LJ, Tao H, Yu NW and Li BH: Identification and validation of

mitochondrial endoplasmic reticulum membrane-related genes in

atherosclerosis. Mamm Genome. 36:665–682. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Wu S, Lu Q, Wang Q, Ding Y, Ma Z, Mao X,

Huang K, Xie Z and Zou MH: Binding of FUN14 domain containing 1

with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in

mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes maintains

mitochondrial dynamics and function in hearts in vivo. Circulation.

136:2248–2266. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Xu H, Yu W, Sun M, Bi Y, Wu NN, Zhou Y,

Yang Q, Zhang M, Ge J, Zhang Y and Ren J: Syntaxin17 contributes to

obesity cardiomyopathy through promoting mitochondrial

Ca2+ overload in a Parkin-MCUb-dependent manner.

Metabolism. 143:1555512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Xu H, Wang X, Yu W, Sun S, Wu NN, Ge J,

Ren J and Zhang Y: Syntaxin 17 protects against heart failure

through recruitment of CDK1 to promote DRP1-dependent mitophagy.

JACC Basic Transl Sci. 8:1215–1239. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Janer A, Morris JL, Krols M, Antonicka H,

Aaltonen MJ, Lin ZY, Anand H, Gingras AC, Prudent J and Shoubridge

EA: ESYT1 tethers the ER to mitochondria and is required for

mitochondrial lipid and calcium homeostasis. Life Sci Alliance.

7:e2023023352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Liu IF, Lin TC, Wang SC, Yen CH, Li CY,

Kuo HF, Hsieh CC, Chang CY, Chang CR, Chen YH, et al: Long-term

administration of Western diet induced metabolic syndrome in mice

and causes cardiac microvascular dysfunction, cardiomyocyte

mitochondrial damage, and cardiac remodeling involving caveolae and

caveolin-1 expression. Biol Direct. 18:92023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Diokmetzidou A, Soumaka E, Kloukina I,

Tsikitis M, Makridakis M, Varela A, Davos CH, Georgopoulos S,

Anesti V, Vlahou A and Capetanaki Y: Desmin and αB-crystallin

interplay in the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis and

cardiomyocyte survival. J Cell Sci. 129:3705–3720. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Raj PS, Nair A, Rani MR, Rajankutty K,

Ranjith S and Raghu KG: Ferulic acid attenuates high

glucose-induced MAM alterations via PACS2/IP3R2/FUNDC1/VDAC1

pathway activating proapoptotic proteins and ameliorates

cardiomyopathy in diabetic rats. Int J Cardiol. 372:101–109. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Yuan M, Gong M, He J, Xie B, Zhang Z, Meng

L, Tse G, Zhao Y, Bao Q, Zhang Y, et al: IP3R1/GRP75/VDAC1 complex

mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mitochondrial oxidative

stress in diabetic atrial remodeling. Redox Biol. 52:1022892022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhang P, Yan X, Zhang X, Liu Y, Feng X,

Yang Z, Zhang J, Xu X, Zheng Q, Liang L and Han H: TMEM215 prevents

endothelial cell apoptosis in vessel regression by blunting

BIK-regulated ER-to-mitochondrial ca influx. Circ Res. 133:739–757.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Tong M, Mukai R, Mareedu S, Zhai P, Oka

SI, Huang CY, Hsu CP, Yousufzai FAK, Fritzky L, Mizushima W, et al:

Distinct roles of DRP1 in conventional and alternative mitophagy in

obesity cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 133:6–21. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Lu X, Gong Y, Hu W, Mao Y, Wang T, Sun Z,

Su X, Fu G, Wang Y and Lai D: Ultrastructural and proteomic

profiling of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum

membranes reveal aging signatures in striated muscle. Cell Death

Dis. 13:2962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Li YE, Sowers JR, Hetz C and Ren J: Cell

death regulation by MAMs: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic

implications in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Dis.

13:5042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Chen X, Yang Y, Zhou Z, Yu H, Zhang S,

Huang S, Wei Z, Ren K and Jin Y: Unraveling the complex interplay

between mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) and cardiovascular

inflammation: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications.

Int Immunopharmacol. 141:1129302024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|