Introduction

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder closely

related to ageing, which is characterized by changes in bone

structure and the loss of bone density (1). According to the International

Osteoporosis Foundation 2024 report (2), ~500 million individuals aged 50 years

and older worldwide are affected by osteoporosis, with 37 million

fragility fractures occurring annually (equivalent to 70 fractures

per minute). This includes over 10 million hip fractures, a subset

of fragility fractures that account for significant morbidity and

mortality (3). Hence,

investigating the pathogenesis of osteoporosis in older individuals

is important in the search for novel intervention strategies and

treatment modalities.

Cellular ageing is a complex biological process. As

the normal cell passage time increases, the mitotic activity

decreases and genomic instability increases, leading to cell

degradation, fragment accumulation and gradual ageing (4). A study has shown that, as primary

cells continue to divide, telomeres shorten. When telomere DNA

shortens to a certain extent, cells reach the limit of normal cell

division and then automatically initiate an ageing process termed

cellular replicative ageing (5). A

number of classical signaling pathways regulate the ageing process

of bone mesenchymal stromal cells (BMSCs). For instance, research

findings have shown that micro RNA (miR)-34a can activate the

sirtuin 1/FOXO3a pathway and induce the ageing of BMSCs under

hypoxia and serum deficiency (6).

Xiang et al (7) found that

the AKT/FOXO3a/PTEN-induced kinase 1/Parkin axis suppresses the

mitosis-induced senescence of BMSCs. In addition, signaling

pathways such as p53/p21WAF1/CIP1 (8), p16/retinoblastoma (9), AKT/mTOR (10) and MAPK (11) are associated with cellular

senescence. These signaling pathways universally participate in the

cellular senescence process of BMSCs. Senescence-related signaling

pathways in BMSCs may be a potential target for small molecule

inhibitors, thereby preventing and treating age-related

degenerative diseases.

BMSCs have the potential to self-replicate and

differentiate into multiple cell types, including osteoblasts and

adipocytes (12). Age-related

functional changes in BMSCs play an essential role in the onset and

progression of osteoporosis (13).

It has been shown that the senescence-associated secretory

phenotype (SASP) secreted by BMSCs increases with age. This

secretion includes various biologically active substances that

modify the functionality of stem and progenitor cells (14). Tian et al (15) found that a reduction in crystallin

αB expression can facilitate the degradation of ferritin heavy

chain 1, leading to elevated iron-induced cell death in BMSCs and a

decline in osteogenic differentiation. Multinucleated osteoclasts

are formed by the fusion of monocyte and macrophage progenitor

cells and play a critical role in osteoporosis initiation. The

functional imbalance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts is a

significant contributing factor to osteoporosis (16). A notable study by Ma et al

(17) found that BMSCs can affect

the differentiation of osteoclasts, a process important in

maintaining bone metabolism equilibrium. Recent research indicates

that the high-fat diet-induced senescence of BMSCs impacts their

proliferation and osteogenic capacity, thereby contributing to the

development of osteoporosis (18).

A prior study on ageing BMSCs have mainly focused on their impact

on osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation (19). However, the precise mechanisms

through which ageing BMSCs influence osteoclast differentiation in

age-related osteoporosis remains ambiguous and necessitates

additional investigation.

The primary objective of the present study was to

identify genes with high expression levels in bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) of osteoporosis patients. Initially,

the GSE35959 transcriptome sequencing dataset was analyzed.

Subsequently, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes

and Genomes (KEGG) functional enrichment analyses were performed to

annotate gene functions and signaling pathways. Principal component

analysis (PCA) was then conducted to visualize sample variations

and groupings, providing insights into inter-sample differences.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was employed to determine the

enrichment of predefined gene sets associated with cellular

processes, exploring potential biological implications at the gene

set level. Furthermore, a replicative senescence model of mouse

BMSCs was established. Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)

PCR and western blotting were utilized to detect the expression of

AKT1 at both mRNA and protein levels in senescent BMSCs.

Gain-of-function experiments were carried out by overexpressing

AKT1 in young BMSCs. To investigate the effects of AKT1 on BMSC

senescence and osteoclast activation, activated senescent BMSCs

were co-cultured with osteoclast precursors and osteoclast

formation was quantified. Through these comprehensive approaches,

the present study aimed to identify novel targets for the

prevention and treatment of age-related osteoporosis.

Materials and methods

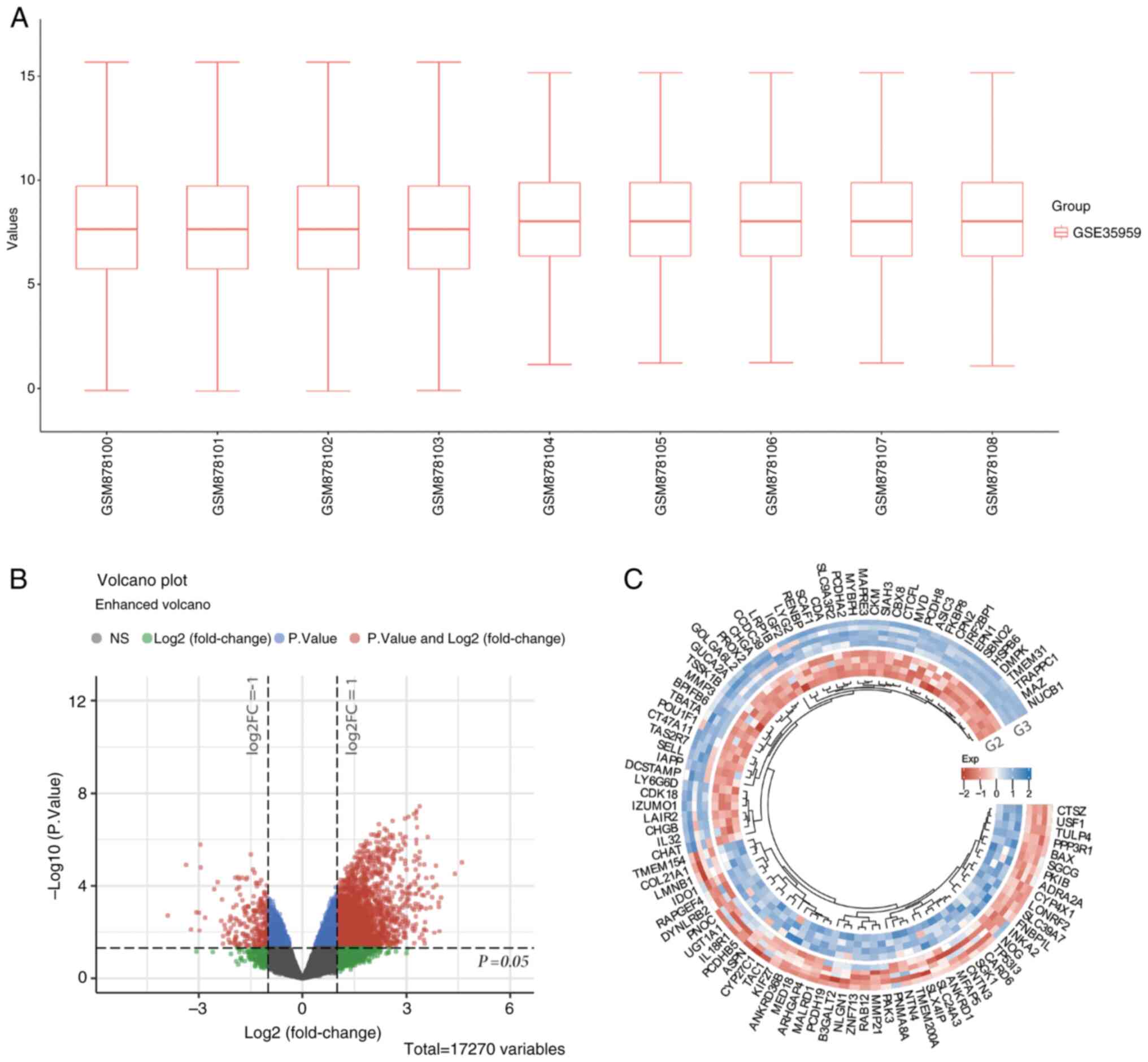

Differential gene screening in BMSCs

from elderly individuals diagnosed with osteoporosis

The transcriptome sequencing data from the GSE35959

dataset were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)

(20). In this analysis, the

population was divided into three groups, G1 (42–67 year healthy

control group, mean age 57.6±9.56 years), G2 (79–89 year

non-osteoporotic control group, mean age 81.75±4.86 years) and G3

(79–94 year osteoporosis patient group, mean age 86.2±5.89 years),

as shown in Table I. Subsequently,

the differential gene expression in the BMSCs from G2 and G3 in the

dataset was analyzed. Differential analysis was conducted using the

‘limma’ package (v3.40.2; http://bioconductor.org/packages/3.10/bioc/html/limma.html)

in R software (v4.0.3) (21),

selecting results with |log2foldchange (FC)|≥1 and Padj<0.05 as

differential genes. Volcano plots were drawn using the ‘ggplot2’

package (v3.3.5; http://cran.r-project.org/package=ggplot2) in R.

Additionally, the expression of differentially expressed genes was

visualized through the ‘pheatmap’ package (v1.0.12; http://cran.r-project.org/package=pheatmap) in R.

| Table I.Population grouping in the present

study. |

Table I.

Population grouping in the present

study.

| Group | Average age

(years) | Osteoporosis

status | Dataset number | Age, years |

|---|

| G1 | 57.6±9.56 | None | GSM878095 | 42 |

|

|

|

| GSM878096 | 67 |

|

|

|

| GSM878097 | 61 |

|

|

|

| GSM878098 | 62 |

|

|

|

| GSM878099 | 56 |

| G2 | 81.75±4.86 | None | GSM878100 | 79 |

|

|

|

| GSM878101 | 79 |

|

|

|

| GSM878102 | 80 |

|

|

|

| GSM878103 | 89 |

| G3 | 86.2±5.89 | Present | GSM878104 | 79 |

|

|

|

| GSM878105 | 94 |

|

|

|

| GSM878106 | 87 |

|

|

|

| GSM878107 | 82 |

|

|

|

| GSM878108 | 89 |

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

The R software package, ‘clusterProfiler’ (v3.18.0;

http://bioconductor.org/packages/3.12/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html)

was used to perform GO and KEGG enrichment analyses on the

downregulated genes in the BMSCs from G2 and to visualize the

results in a bubble chart form.

PCA and GSEA

The R software package ‘ggplot2’ (v3.3.5) was used

to perform PCA visualization on the gene expression data from three

groups (G1, G2 and G3) and to present the results in both

two-dimensional (PC1 vs. PC2) and three-dimensional (PC1 vs. PC2

vs. PC3) scatter plot formats. The R software packages

‘clusterProfiler’ (v3.18.0) and ‘fgsea’ (v1.16.0; http://bioconductor.org/packages/3.12/bioc/html/fgsea.html)

were used to perform GSEA on the differentially expressed genes

between G2 and G3, calculate enrichment scores (ES), conduct

pathway-related analyses using signaling pathways in the KEGG

pathway database and visualize the results via enrichment plots and

running enrichment score plots.

Cell lines

Mouse BMSCs were acquired through primary isolation

from mouse bone marrow tissue by a subsidiary of the Eli Lilly and

Company (Sichuan Lilaisinuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) (cat. no.

LL-A1-80093). Cell lines were obtained as commercially prepared

primary cells or cell lines, without additional animal procurement

or primary isolation by the research team. RAW 264.7 cells (cat.

no. CL-0190) were procured from Procell Life Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.

Establishment of a replicative ageing

BMSCs model

Primary BMSCs were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no.

16000-044) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). All cells were maintained at 37°C with 95%

humidity and 5% CO2 and regularly tested for mycoplasma

by PCR (Genlantis Diagnostics Inc.). Based on established

replicative ageing models, the P3 (early passage) and P10 (late

passage) timepoints were selected for analysis, as P10 BMSCs are

known to exhibit elevated senescence markers (22,23).

The cells were continuously passaged for 10 generations to generate

the replicative ageing cell model (P10-BMSCs).

Western blotting (WB)

The mouse BMSC samples were collected and then lysed

using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor and

phosphatase inhibitor (all Biosharp Life Sciences). The protein

concentration was detected using a BCA protein detection kit

(Shanghai Biyuntian Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Next, ~30 µg of

protein sample was separated on a Bis-Tris 10% high-resolution

precast gel (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and then

transferred onto an Immobilon PSQ PVDF membrane (MilliporeSigma).

The membrane was subsequently incubated with 5% skimmed milk (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology, Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room temperature. The

membrane was then incubated with primary antibodies against AKT1

(ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.; cat. no. A17909; 1:1,000), p16

(ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.; cat. no. A23882; 1:1,000), p21

(Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no. 28248-1-AP, 1:2,000) and β-actin

(ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.; cat. no. AC026; 1:50,000) overnight at

4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with a Goat Anti

Rabbit IgG (H+L) HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Affinity

Biosciences; cat. no. S0001; 1:5,000) at room temperature for 1 h.

Finally, protein bands were visualized using the ‘Torchlight’

Hypersensitive ECL Western HRP Substrate (Chengdu Zen-Bioscience

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 17046) and imaged using a 5200 Multi

chemiluminescence image analysis system (Tanon Science and

Technology Co., Ltd.). Densitometric analysis of the bands was

performed using Gel-Pro Analyzer software (version 4.0; Media

Cybernetics, Inc.).

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse sample cells

using the Molpure® Cell/Tissue Total RNA Kit (Shanghai

Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). For RNA extraction, cells were

lysed with 350 µl lysis buffer LB (supplied in the kit) at a

density of 1–5×106 cells per sample (the lysate was

repeatedly pipetted until no cell clumps were visible). After

quantification, 1 µg RNA was reverse transcribed using the

PrimeScript RT kit (Baoriyi Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) with a

protocol of 37°C for 15 min followed by 85°C for 5 sec; this step

was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was

performed using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH

Plus; Bao Ri Yi Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), with thermocycling

conditions as follows: 95°C for 30 sec (pre-denaturation), followed

by 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec (denaturation), 55°C for 30 sec

(annealing) and 72°C for 30 sec (extension with fluorescence

acquisition); qPCR was also performed according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The Cq (quantification cycle) values of

the samples were detected using QuantStudio Design & Analysis

SE Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). GAPDH was used as the

reference gene and quantification was performed using the

2−ΔΔCq method (24).

All experiments (RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR) were

independently replicated three times. The primer sequences used in

this experiment are shown in Table

II.

| Table II.Primer sequences used in the present

study. |

Table II.

Primer sequences used in the present

study.

| Primer | Forward primer,

5′-3′ | Reverse primer,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| β-actin |

CTACCTCATGAAGATCCTGACC |

CACAGCTTCTCTTTGATGTCAC |

| AKT1 |

TGCACAAACGAGGGGAATATAT |

CGTTCCTTGTAGCCAATAAAGG |

| NFATc1 |

GAGAATCGAGATCACCTCCTAC |

TTGCAGCTAGGAAGTACGTCTT |

| RANK |

CTGAAAAGCACCTGACAAAAGA |

CTGTGTAGCCATCTGTTGAGTT |

| TRAF6 |

GAAAATCAACTGTTTCCCGACA |

ACTTGATGATCCTCGAGATGTC |

Plasmid transfection

Logarithmically growing bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells (BMSCs) were washed with PBS, trypsinized, centrifuged at 250

× g for 5 min at room temperature, resuspended in culture medium,

counted, adjusted to 1×105 cells/ml and seeded at 2

ml/well in 6-well plates. After adhesion, transfection complexes

were prepared by adding 15 µg AKT1 cDNA recombinant plasmid

[pcDNA3.1(+); plasmid (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

containing mouse AKT1 ORF sequence (cat. no. MG50254-M; Sino

Biological Inc.)] to 300 µl Opti-MEM I in one tube and 30 µl

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) to 300 µl Opti-MEM I in another, incubating both

for 5 min, combining them, incubating for 10 min and adjusting the

volume to 6 ml with Opti-MEM I. Control cells (NC group) were

transfected with 15 µg empty cloning vector (Sino Biological Inc.).

After 6 h at 37°C, the medium was replaced with a complete medium

(cat. no. CM-M131; Procell Life Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.), and the cells underwent further culturing such that the

total duration from transfection to subsequent experiments was 48

h. For validation, supernatants were collected, cells were washed

with PBS, trypsinized, centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min at room

temperature, washed again with PBS and centrifuged at 250 × g for 5

min at room temperature to obtain cell pellets for qPCR and western

blot analysis.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase

(SA-β-gal) staining

Logarithmically growing RAW264.7 cells were

dissociated into a single-cell suspension, centrifuged at 250 × g

for 5 min at room temperature and resuspended in culture medium.

Cells were counted and seeded at 0.5×105 cells/ml (2

ml/well) in 6-well plates, then incubated at 37°C with 5%

CO2. After adhesion, transfection complexes were

prepared by mixing 15 µg of AKT1 cDNA ORF Clone (plasmid backbone:

Cloning Vector; cat. no. MG50254-M; Sino Biological Inc.) in 300 µl

Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) with 30 µl Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in 300 µl Opti-MEM I, incubating both

tubes for 5 min, combining them and further incubating for 10 min.

The mixture was adjusted to 6 ml with Opti-MEM I before adding to

cells. Control cells (NC group) were transfected with an equal mass

of empty cloning vector. After 48 h, cells were washed with PBS,

fixed with 1 ml β-galactosidase staining fixative (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology; C0602) for 15 min at room temperature

and washed twice with PBS (3 min each). Staining working solution

(1 ml/well) was prepared by mixing 10 µl β-galactosidase staining

solution A, 10 µl solution B, 930 µl solution C and 50 µl X-Gal

solution (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. C0602) and

applied to cells overnight at 37°C. Images were captured using an

inverted biological microscope (DMI1; Leica Microsystems,

Ltd.).

Osteolysis induction and co-culturing

of RAW264.7 cells and osteoclasts

Logarithmically growing RAW264.7 cells were

dissociated into a single-cell suspension, centrifuged at 250 × g

for 5 min at room temperature, resuspended in culture medium,

counted, adjusted to 0.5×105 cells/ml and seeded at 2

ml/well (1×105 cells/well) in 6-well plates. After

adhesion, cells were induced to differentiate into osteoclasts with

α-MEM medium (cat. no. 41061029; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 50 µg/l RANK ligand (cat. no. C28A;

Novoprotein Scientific Inc.), incubated at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 atmosphere and the medium was replaced every 2 days

for 5 days. Transfected BMSCs were then counted, adjusted to

2×105 cells/ml and 2 ml/well (4×105

cells/well) were seeded into the upper chamber of a Transwell

plate, while the induced osteoclasts remained in the lower chamber

of the 6-well plate for 48 h of co-culture under the same

conditions before subsequent staining.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

(TRAP) staining

After removing the supernatant, co-cultured cells

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature

and washed three times with distilled water. Cells were

permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 30

min, followed by three light washes with distilled water. The TRAP

staining kit (cat. no. G1492; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) was used according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Mature osteoclasts were identified as multinucleated

cells (≥3 nuclei) and images were captured using an inverted

biological microscope (DMI1; Leica Microsystems, Ltd.) (25).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.0 statistical software (Dotmatics)

was used to perform graphical analysis and statistical testing on

experimental data, which are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. For experimental datasets, comparisons between two

groups were conducted using an unpaired two-tailed Student's

t-test. For comparisons among three or more groups, one-way

analysis of variance was used for normally distributed data with

homogeneous variances, followed by Tukey's Honestly Significant

Difference test for pairwise comparisons when overall differences

were significant, and Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to

non-normally distributed or heteroscedastic data, with Dunn's

multiple comparisons test for post hoc pairwise comparisons upon

significant differences. For bioinformatics data analyses (such as

high-throughput sequencing or -omics data), R software 4.2.2 was

used to handle complex statistical modeling and computational

pipelines. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Screening of differentially expressed

genes in BMSCs from G3

The GSE35959 dataset was selected to analyze the

effects of primary osteoporosis on BMSC gene expression. Initially,

no abnormal outliers were observed in the BMSC samples from G2 and

G3 (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, the

differential gene expression between BMSCs from G2 and G3 was

analyzed. According to the results, BMSCs obtained from G2 had 274

upregulated genes and 2,592 downregulated genes (Fig. 1B). The heatmap shown in Fig. 1C depicts the expression of the

differentially expressed genes in the two groups. Due to the large

number of differentially expressed genes, the top 50 upregulated

and the top 50 downregulated genes with the greatest differential

changes are displayed separately.

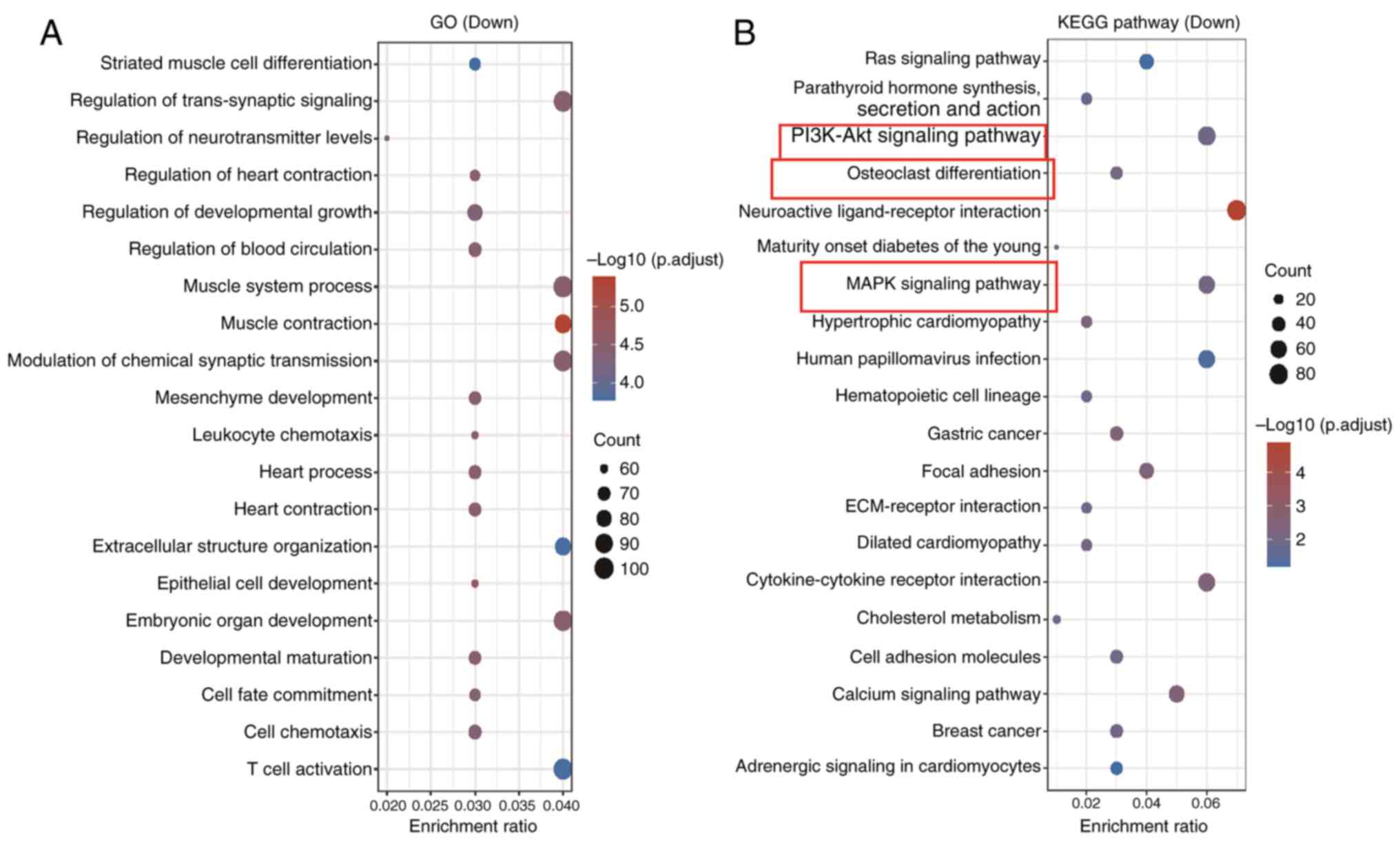

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed on

the 2,592 genes that were upregulated in BMSCs from G3. The GO

results showed that these genes mainly participate in processes

such as ‘striated muscle cell differentiation,’ ‘regulation of

trans-synaptic signaling’ and ‘regulation of neurotransmitter

levels’ (Fig. 2A). The KEGG

enrichment analysis revealed a significant association with the

‘PI3K/Akt signaling pathway’, ‘osteoclast differentiation’ and

‘MAPK signaling pathway’ (Fig.

2B). Several classical signaling pathways, including

PI3K/AKT/mTOR, p53/p21 and MAPK, have been demonstrated to

influence BMSC ageing (26,27).

Subsequent analysis indicated the enrichment of AKT1, MAPK3,

RELA and CSF1 in the MAPK signaling, PI3K/AKT signaling

and osteoclast differentiation pathways. Subsequently, using the

GSE35959 dataset, the levels of the aforementioned four genes in

BMSCs from G1, G2 and G3 were further analyzed (Fig. S1). According to the results, the

expression levels of the four genes were markedly lower in BMSCs

from G2 than those from G1, while the expression levels of the four

genes were markedly higher in BMSCs from G3 than those from G1.

Hence, it was hypothesized that the overactivation of AKT1,

MAPK3, RELA and CSF1 in the stem cells of G3 may

contribute to the pathogenesis of osteoporosis.

PCA and GSEA

PCA analysis revealed differences in gene expression

patterns between the three groups: G1, G2 and G3. Fig. S2A displays a two-dimensional PCA

plot, where PC1 explains 22.4% of the variation and PC2 explains

13% of the variation. The three sample groups form distinct

clusters, indicating significant differences in gene expression

between them. Fig. S2B shows the

three-dimensional PCA plot, adding PC3 (explaining 9.2% of the

variation), further reinforcing the separation pattern between the

sample groups. This clustering pattern suggests that both age (G1

vs. G2) and disease status (G2 vs. G3) have significant effects on

gene expression that can be clearly distinguished through PCA. GSEA

revealed significant positive enrichment of the

‘KEGG_PI3K-Akt_signaling_pathway’ in the comparison between the G3

and G2 groups (Fig. S2C). The

normalized enrichment score was 1.552 with an adjusted P-value of

0.004, indicating statistically significant activation of this

pathway. The running enrichment score (RES) curve displayed a

prominent positive peak (maximum RES ~0.3) and genes within the

pathway were predominantly clustered on the left side of the ranked

list (red area), reflecting their upregulated expression in the G3

group. These results suggested that the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

is markedly activated during the progression from healthy aging

(G2) to osteoporosis (G3). This differential regulation highlights

the potential role of this pathway in the pathophysiology of

osteoporosis, offering critical insights for identifying

therapeutic targets.

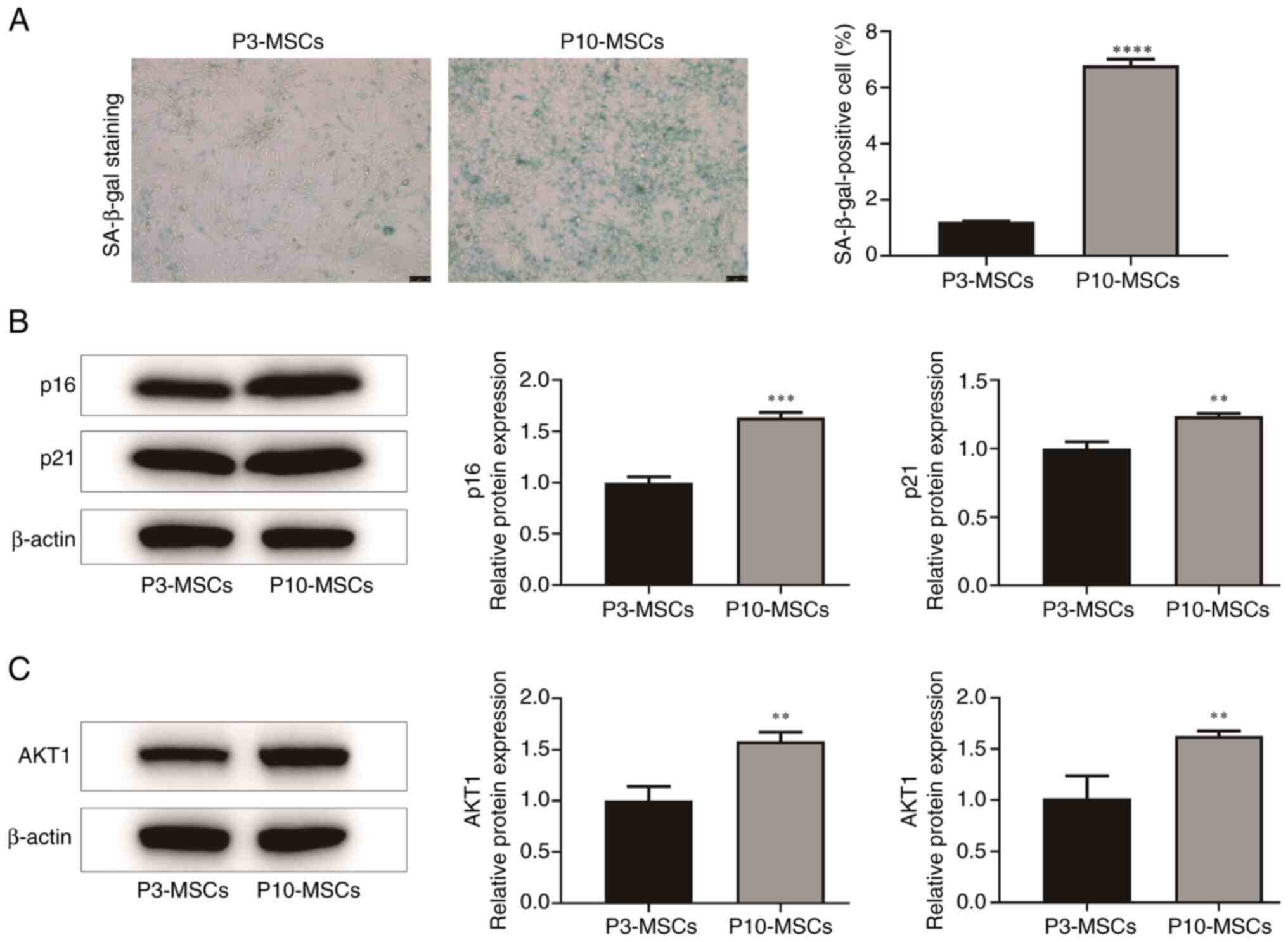

Changes in AKT1 expression levels in

BMSCs with replicative ageing

In the present study, P3 and P10 denoted early

(younger) and late (older) passage numbers of BMSCs, respectively,

with higher passage numbers reflecting increased replicative

cycles. It is well established that SA-β-gal staining, p21

expression and p16 expression serve as significant biomarkers of

the ageing process in BMSCs (28,29).

The results indicated that the number of SA-β-gal positive cells

was markedly higher in the P10-MSCs group than in the P3-MSCs group

(P<0.0001). Additionally, the relative protein expression levels

of the cell ageing markers, p16 (P<0.001) and p21 (P<0.01),

were also markedly increased in the P10-MSCs group compared with

the P3-MSCs group. These results suggested the successful

establishment of a replicative ageing model of BMSCs in the

P10-MSCs group (Fig. 3A and

B).

AKT is a serine/threonine kinase that is dependent

on PI3K. Research indicates that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is

essential for regulating cell differentiation (30). As a member of the AKT family, AKT1

is integral to the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Consequently, a

further examination of the AKT1 expression levels in both the

P3-MSCs and the P10-MSCs groups was conducted. The results of the

PCR and WB analyses indicated that, compared with the P3-MSCs

group, P10-MSCs had markedly higher AKT1 protein and mRNA

expression levels (P<0.05; Fig.

3C). These findings suggest that replicative ageing may enhance

the expression of AKT1 protein in BMSCs.

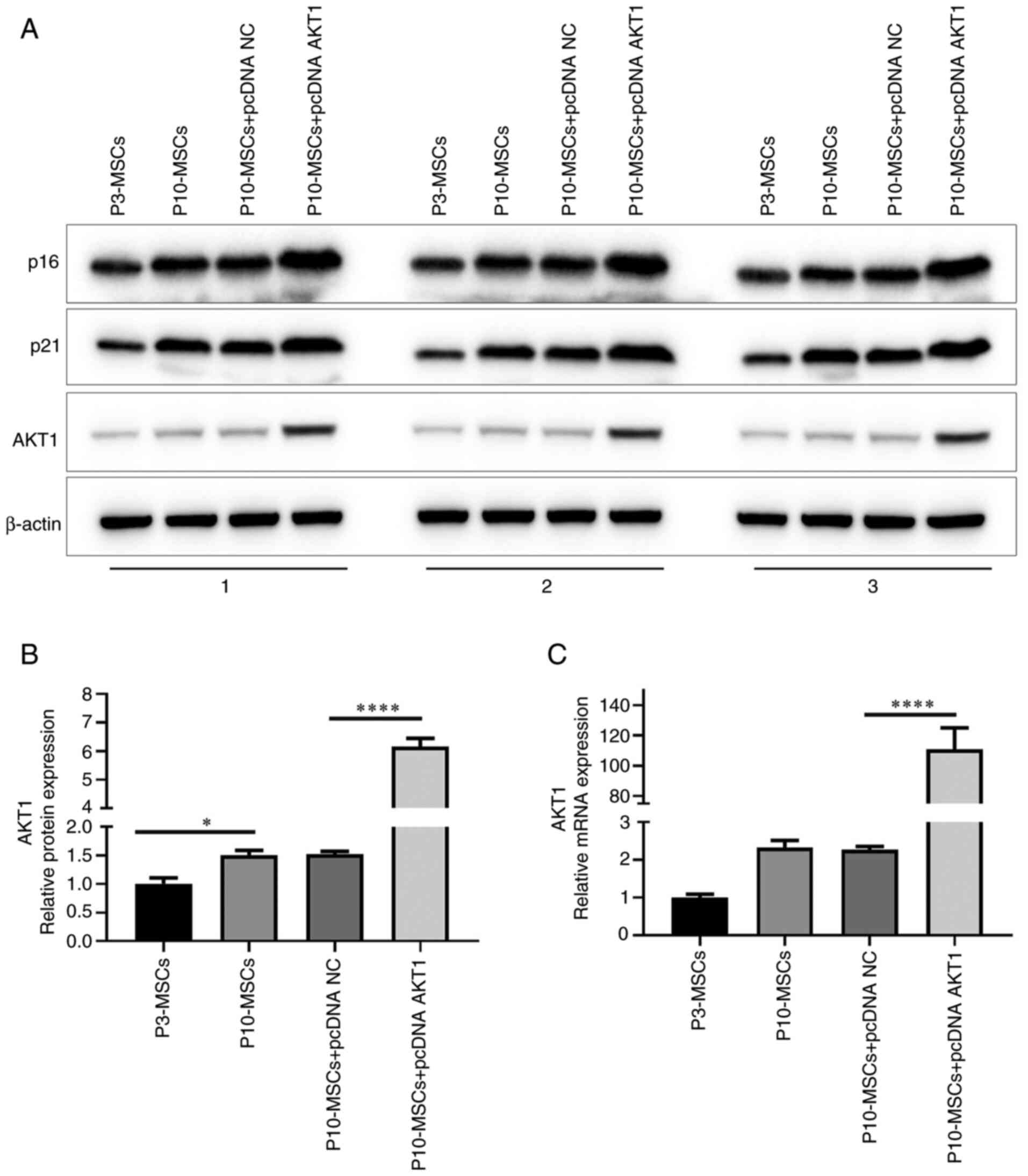

Confirmation of the transfection

efficiency of the AKT1 overexpression plasmid

To further investigate the effect of AKT1 on the

ageing of BMSCs, the gene encoding the AKT1 protein was cloned into

a pcDNA expression vector and subsequently transfected into

P10-MSCs. As shown in Fig. 4A, the

WB results showed that P10-MSCs transfected with pcDNA AKT1 had

higher levels of AKT1 protein. Following statistical analysis of

the results, it was found that in transfected P10-MSCs, AKT1

protein levels exhibited a significant increase compared with

transfected P3-MSCs (P<0.05). This finding suggests that

replicative ageing has a notable effect on elevating AKT1 protein

levels in BMSCs. In addition, compared with the P10-MSCs + pcDNA

negative control (NC) group, the P10-MSCs + pcDNA AKT1 group

exhibited a statistically significant increase in AKT1 protein

levels (P<0.0001; Fig. 4B).

Finally, qPCR demonstrated that, compared with the P10-MSCs + pcDNA

NC group, the relative mRNA expression level of AKT1 was

statistically elevated in the P10-MSCs + pcDNA AKT1 group

(P<0.0001; Fig. 4C). In

summary, these experimental findings indicated the successful

transfection of pcDNA AKT1 into P10-MSCs.

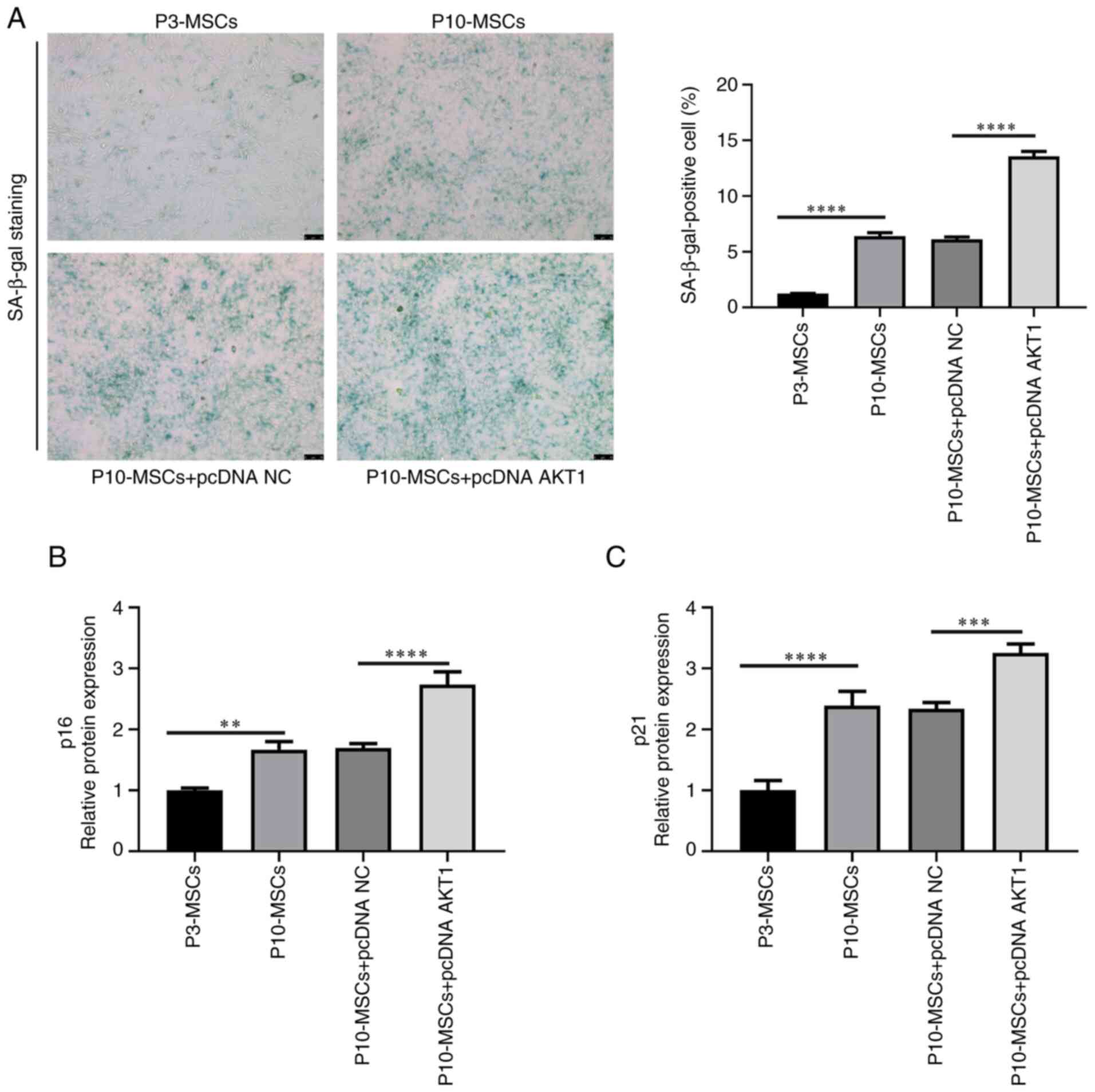

Effect of AKT1 overexpression on the

replicative ageing of BMSCs

Subsequently, the effect of AKT1

overexpression on the replicative ageing of BMSCs was verified.

Following SA-β-gal staining, the P10-MSCs + pcDNA AKT1 group had a

markedly higher proportion of SA-β-gal positive cells than the

P10-MSCs + pcDNA group (Fig. 5A).

Subsequently, a comprehensive analysis of the protein levels of the

cell ageing markers, p16 and p21, in all four experimental groups

was conducted through WB experiments (Fig. 4A). In addition, compared with the

P10 MSCs + pcDNA group, the levels of the p16 and p21 proteins were

markedly increased in the P10 MSCs + pcDNA AKT1 group (P<0.001;

Fig. 5B and C). In conclusion,

these findings indicated that the overexpression of AKT1

promotes the ageing process of BMSCs.

Effect of AKT1 overexpression on

regulating osteoclast differentiation in replicative ageing

BMSCs

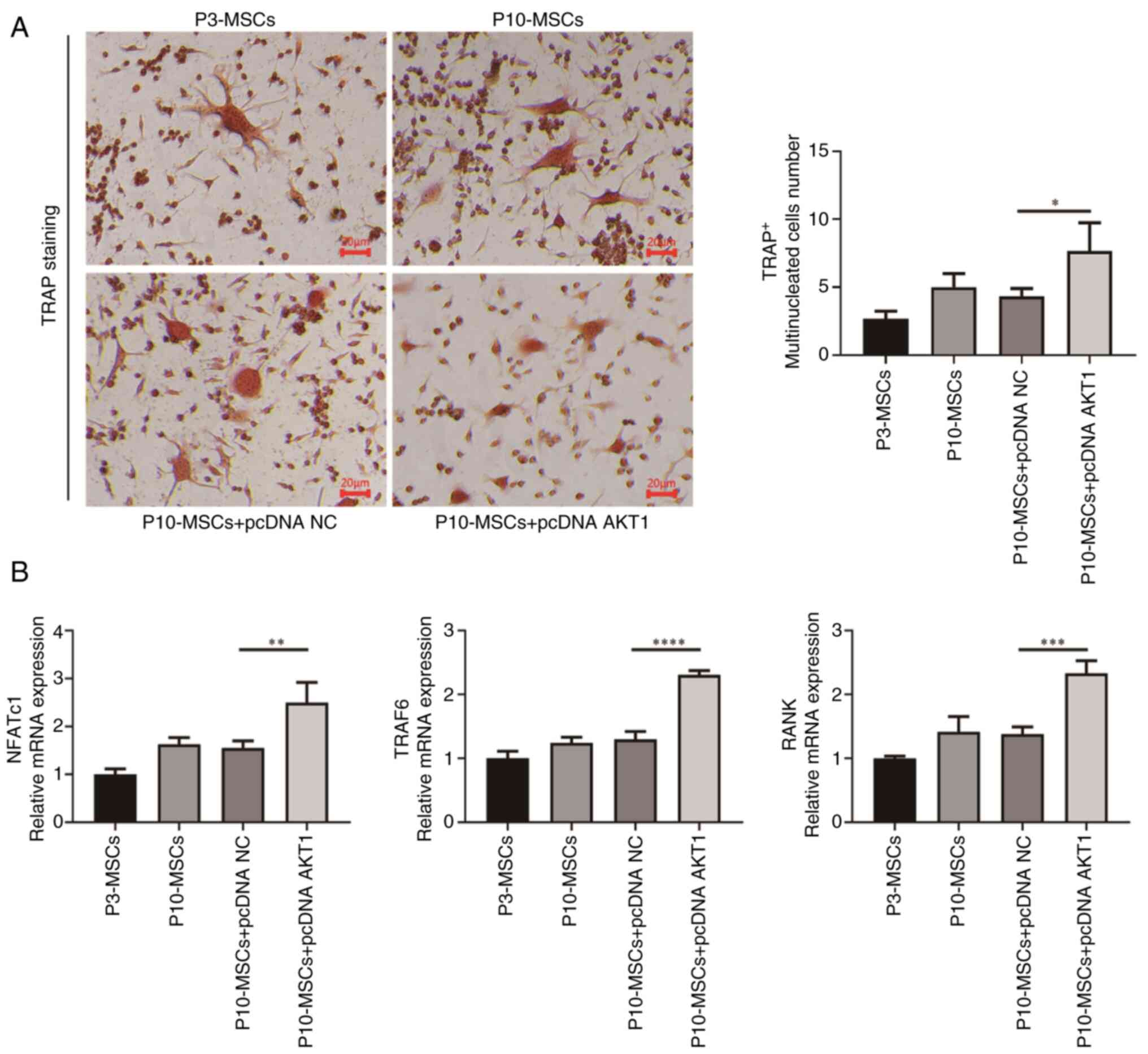

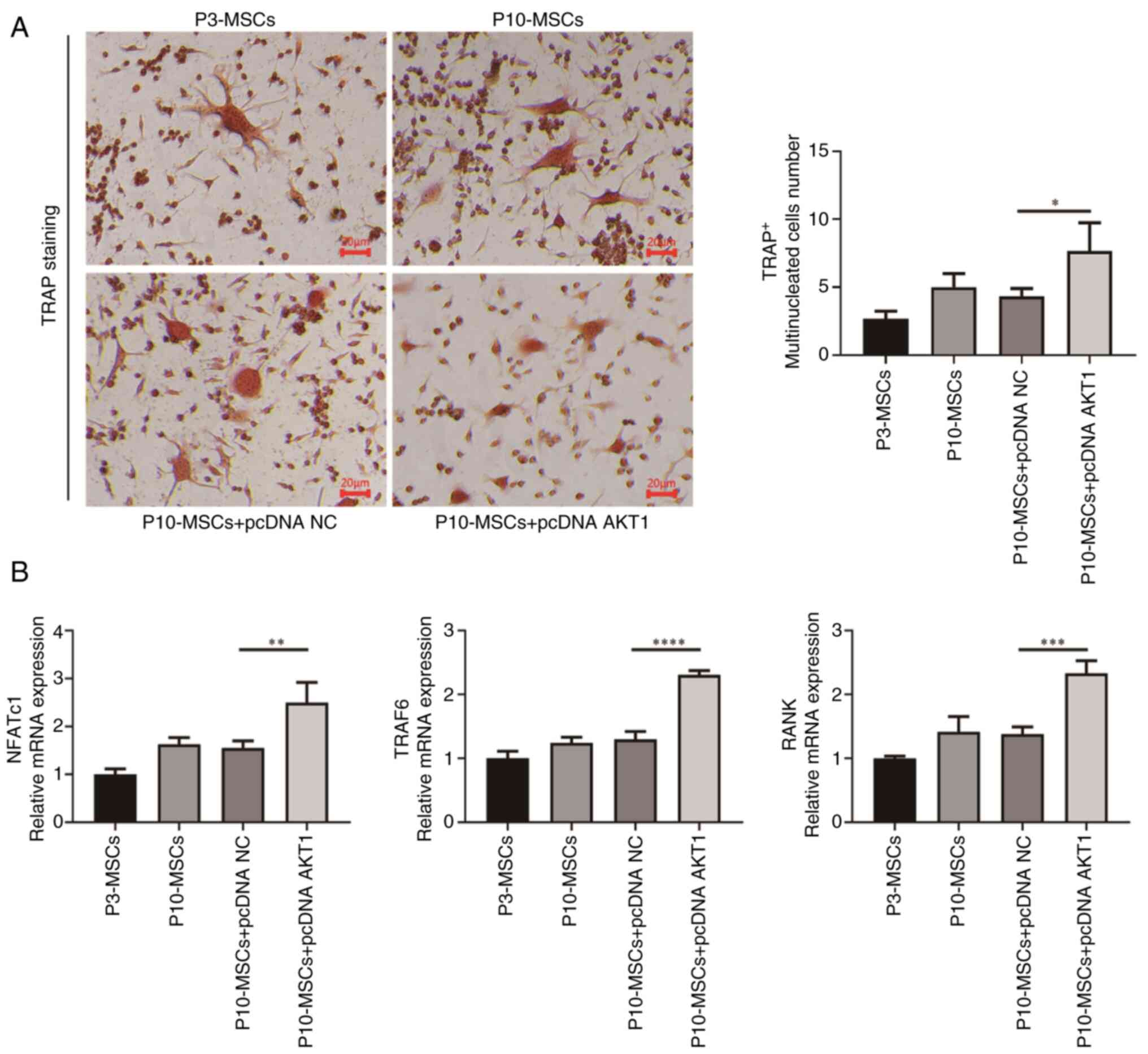

In the aforementioned enrichment analysis, it was

indicated that AKT1 may be markedly associated with the

differentiation of osteoclasts in G3. Therefore, experiments using

replication-aged BMSCs were performed to further test the

regulatory role of AKT1 in osteoclast differentiation.

Initially, the supernatant derived from BMSCs was co-cultured with

osteoclasts, as shown in Fig. 6.

It was found that the quantity of TRAP+ multinucleated

cells in the P10-MSCs group was higher than that in the P3-MSCs

group, but this difference was not statistically significant

(P>0.05). Additionally, the P10-MSCs showed a tendency to

express osteoclast differentiation markers. The nuclear factor of

activated T cells, cytoplasmic 1 (NFATc1), tumor necrosis

factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and RANK

mRNA levels were higher in P10-MSCs than in the P3-MSCs group, but

this difference was not statistically significant (P>0.05).

Subsequently, a comparative analysis of the number of

TRAP+ multinucleated cells and the relative mRNA

expression levels of osteoclast differentiation markers, including

NFATc1, TRAF6 and RANK, between the P10-MSCs group

and the P10-MSCs + pcDNA NC group was conducted. There were no

significant differences (P>0.05) in these markers between these

groups. However, the results of the PCR experiment indicated that,

compared with the P10-MSCs + pcDNA NC group, the relative mRNA

expression levels of the osteoclast differentiation markers,

NFATc1 (P<0.01), TRAF6 (P<0.0001) and

RANK (P<0.001), were markedly increased in the P10-MSCs +

pcDNA AKT1 group. In summary, these findings suggested that BMSCs

experiencing replicative ageing may facilitate the differentiation

of osteoclasts. Furthermore, an elevated AKT1 expression

level in ageing BMSCs may be associated with the promotion of

osteoclast differentiation.

| Figure 6.Replicative-aged BMSCs regulate

osteoclast differentiation. (A) TRAP staining to detect osteoclast

differentiation (×200 magnification). (B) PCR to detect the mRNA

expression of the osteoblast markers, NFATc1, TRAF6 and

RANK, in each group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. BMSCs, bone mesenchymal stromal cells; TRAP,

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; NFATc1, nuclear factor of

activated T cells, cytoplasmic 1; TRAF6, tumor necrosis factor

receptor-associated factor 6; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear

factor κB. |

Discussion

Research has demonstrated that the ageing of BMSCs

influences the equilibrium between bone formation and resorption,

serving as a significant contributor to age-related bone diseases

(31). Jin et al (32) found that optineurin facilitates the

osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and inhibits adipogenic

differentiation by delaying cellular ageing and enhancing

autophagy. According to Hu et al (22), nucleosome assembly protein 1 like 2

is responsible for driving the ageing of mesenchymal stem cells and

preventing their differentiation into osteoblasts. However, current

research on the effects of ageing BMSCs in age-related bone

diseases predominantly emphasizes the differentiation processes

between osteoblasts and adipocytes. By contrast, there is a paucity

of studies investigating the influence of ageing BMSCs on

osteoclast differentiation. Ageing BMSCs can promote the

differentiation of bone marrow monocytes into osteoclasts,

ultimately leading to the occurrence of osteoporosis (33). Research on the novel mechanisms

that ageing BMSCs use to influence osteoclast activation is

essential for age-related osteoporosis discovery, prevention and

treatment. In the present study, it was observed that replicative

ageing enhanced the expression of AKT1 protein in BMSCs and this

increase in AKT1 expression further exacerbated the ageing process

of BMSCs. Furthermore, the overexpression of AKT1 was shown to

promote osteoclast activation in ageing BMSCs, which may contribute

to the development of osteoporosis.

Previous research has confirmed that cellular ageing

is influenced by the regulation of various signaling pathways. For

instance, Prince et al (34) identified a correlation between the

AKT/mTOR pathway and the progression of ageing in ACP epithelial

cells. In addition, Li et al (35) demonstrated that deoxynivalenol

induces cellular senescence in RAW264.7 macrophages through

modulation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α/p53/p21 signaling

pathway. The present study initially conducted a screening of

highly expressed genes in BMSCs from G3, using bioinformatics

methodologies. Then, an enrichment analysis of the highly expressed

genes was conducted. Bubble plots revealed a significant

association between these genes and the PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling

pathways, as well as osteoclast differentiation processes. It is

noteworthy that the four genes, AKT1, MAPK3, RELA and

CSF1, exhibited significant enrichment in the aforementioned

three pathways. PCA confirmed transcriptional divergence with aging

and disease and GSEA revealed significant enrichment of the

PI3K/AKT pathway in G3 vs. G2. Previous research has indicated that

AKT is crucial in the ageing process across various cell types

(36,37). Nevertheless, there has been a lack

of research to ascertain whether the expression of AKT1

influences the replicative ageing of BMSCs.

Ageing-related biomarkers such as SA-β-gal staining,

p21 expression and p16 expression are used to evaluate the process

of cellular ageing (38,39). The present study initially observed

a significant increase in ageing-related markers, specifically in

the p21 and p16 protein levels as well as the number of SA-β-gal

positive cells, in the P10-MSCs group (cultured continuously for 10

generations) compared with the P3-MSCs group (cultured for three

generations). This indicated that a replicative ageing model was

successfully established using P10-MSCs. In addition, it was found

that P10-MSCs expressed markedly higher levels of AKT1 mRNA and

protein, which indicated that senescent BMSCs have higher AKT1

protein levels. Additionally, the overexpression of AKT1 in

the P10-MSCs group resulted in an increased proportion of SA-β-gal

positive cells, as well as higher p21 and p16 levels. This finding

suggested that AKT1 may facilitate the promotion of

senescence in BMSCs. Consistent with these findings, the study

conducted by Xiang et al (7) demonstrated that CSE can induce ageing

in BMSCs through the upregulation of phosphorylated AKT. Overall,

in the present study, the expression of AKT1 was found to be

elevated in senescent BMSCs and the overexpression of AKT1 was

shown to promote senescence in these cells. Accordingly, it is

hypothesized that AKT1 represents a novel therapeutic target

for treating and preventing replicative senescence in BMSCs. To the

best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to indicate

that AKT1 upregulation enhances the regulation of osteoclast

differentiation in BMSCs undergoing replicative ageing.

The overactivation of osteoclasts is a significant

contributor to the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. A previous study

showed that the pro-inflammatory SASP released by senescent cells

activates osteoclast precursors to promote osteoclast

differentiation, ultimately leading to a decrease in bone density

(40). In addition, a study has

shown that CSF1 regulated by nuclear paraspeckle assembly

transcript 1 can be delivered extracellularly through paracrine

pathways in ageing BMSCs, thereby promoting osteoclast

differentiation (41). In the

present study, a greater percentage of TRAP+

multinucleated cells was observed in the P10-MSCs group than in the

P3-MSCs group, it has been documented that RANK, NFATc1 and

TRAF6 serve as significant biomarkers in the differentiation

process of osteoclasts (42,43).

The present study found that the RANK, NFATc1 and

TRAF6 mRNA expression levels were increased in P10-MSCs.

These findings suggested that ageing BMSCs may facilitate the

activation of osteoclasts. Xie et al (44) found that the SHIP1

activator, AQX-1125, modulates the differentiation of osteoblasts

and osteoclasts via the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways.

However, there are some shortcomings in the present

research. First, further investigation is needed on how the

upregulation of AKT1 promotes the replicative ageing of

BMSCs. A previous report has indicated that epigenetics can

regulate gene transcription and translation processes by modifying

gene expression through various pathways and cellular ageing is

regulated by DNA methylation, histone modification, chromatin

remodeling and non-coding RNA (45). While the present study links AKT1

upregulation to senescence, the upstream triggers (such as DNA

damage and telomere attrition) remain unexplored. Future research

should assess AKT1 phosphorylation and its interaction with the

PI3K/AKT pathway components to elucidate mechanistic drivers. The

present study has certain room for improvement in the construction

of the senescence model and mechanistic analysis. The current

research only selected two timepoints, passage 3 (early passage)

and passage 10 (late passage), to establish the senescence model.

While this selection was based on the classical replicative

senescence model (where passage 10 BMSCs are known to highly

express senescence markers), it indeed failed to fully characterize

the continuous trajectory of BMSCs transitioning from a highly

proliferative state to degenerative senescence. Such a jump-type

analysis between two passages may have obscured key

intermediate-stage changes during the senescence process. The

present study started from molecular characteristics of clinical

senescent samples to validate pathological key pathways, selecting

senescent cells as subjects. The role of AKT1 in proliferative

cells needs upstream mechanism exploration via independent

experiments. AKT1 overexpression may have ‘enhancing/inducing

senescence’ dual effects, with mechanisms needing further study.

Expanding this area will aid revealing the role of AKT1 in the

senescence continuum and provide early osteoporosis intervention

targets. In addition, a recent study found that aldehyde

dehydrogenase 2 regulates mesenchymal stem cell ageing by

maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis (46), which provides direction for future

research. Second, regarding how ageing BMSCs regulate osteoclast

differentiation, the study by Yin et al (33) demonstrated that the extracellular

vesicles containing miR-144-5p secreted by ageing BMSCs play a

significant role in osteoclast differentiation but the specific

mechanism is unclear. Third, while rigorous thresholds (|log2FC|≥1,

Padj<0.05) support the findings of the present study, the

limited sample size of the GSE35959 dataset may affect

generalizability. Larger-scale studies incorporating broader age

ranges are warranted to validate the current observations. Future

studies should incorporate functional assays (such as bone

resorption pits) to validate the osteoclast-promoting effects of

AKT1-overexpressing BMSCs.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study

indicated that ageing increased the expression of AKT1 in

BMSCs and this elevated expression of AKT1 further

exacerbates the ageing process. In addition, ageing BMSCs that

upregulate AKT1 can promote osteoclast differentiation. The

present study provided new insights into the mechanisms of

age-related osteoporosis, as well as potential prevention and

treatment targets.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the funding of the ‘Kunlun

Talent Plateau Famous Doctor’ Talent Project of Qinghai Province in

2022.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

CL was responsible for writing the original draft,

reviewing and editing, methodology (including design of

experimental protocols and analytical approaches) and investigation

(acquisition of data). XP contributed to core study conception and

design, managed data acquisition, organization, and statistical

analysis/interpretation of key results, revised core content

(conclusion rigor, discussion depth), reviewed and approved the

final publication version, and took responsibility for the work's

accuracy and integrity. BZ performed experimental data validation

for reliability in addition to data archiving and structured

storage. QY focused on experimental quality control (instrument

calibration and reagent validation). BD was responsible for

validation of the data analysis methods and results, as well as

analysis and interpretation of key data. GK was responsible for

validation, reviewing, writing and conception of the study design.

WG was responsible for validation of the data analysis methods and

results, as well as analysis and interpretation of key data. PK was

responsible for validation, reviewing, writing and interpretation

of experimental data. KL was responsible for resources,

supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, and

conception and design of the overall study. BD and WG confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures, including the use of primary BMSCs,

were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Qinghai

University Affiliated Hospital (approval no. P-SL-202481). The

extraction of primary BMSCs from mice used in the experiment was

approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Sichuan

Lilaisinuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (approval no. LLSN-2023170).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

BMSCs

|

bone mesenchymal stromal cells

|

|

TRAP

|

tartrate-resistant acid

phosphatase

|

|

SASP

|

senescence-associated secretory

phenotype

|

|

MSCs

|

mouse BMSCs

|

|

SA-β-gal

|

senescence-associated

β-galactosidase

|

|

RANK

|

receptor activator of nuclear factor κ

B

|

|

NFATc1

|

nuclear factor of activated T cells,

cytoplasmic 1

|

|

CSE

|

cystathionine γ-lyase

|

|

TRAF6

|

tumor necrosis factor

receptor-associated factor 6

|

|

SHIP1

|

src homology 2 domain-containing

inositol 5-phosphatase 1

|

References

|

1

|

Roux C and Briot K: The crisis of

inadequate treatment in osteoporosis. Lancet Rheumatol.

2:e110–e119. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

International Osteoporosis Foundation

(IOF), . Epidemiology of osteoporosis and fragility fractures. IOF

Official Report. 2024.https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/facts-statistics/epidemiology-of-osteoporosis-and-fragility-fracturesMay

21–2025

|

|

3

|

Salari N, Darvishi N, Bartina Y, Larti M,

Kiaei A, Hemmati M, Shohaimi S and Mohammadi M: Global prevalence

of osteoporosis among the world older adults: A comprehensive

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 16:6692021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ogrodnik M: Cellular aging beyond cellular

senescence: Markers of senescence prior to cell cycle arrest in

vitro and in vivo. Aging Cell. 20:e133382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhu Y, Liu X, Ding X, Wang F and Geng X:

Telomere and its role in the aging pathways: Telomere shortening,

cell senescence and mitochondria dysfunction. Biogerontology.

20:1–16. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang F, Cui J, Liu X, Lv B, Liu X, Xie Z

and Yu B: Roles of microRNA-34a targeting SIRT1 in mesenchymal stem

cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 6:1952015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Xiang K, Ren M, Liu F, Li Y, He P, Gong X,

Chen T, Wu T, Huang Z, She H, et al: Tobacco toxins trigger bone

marrow mesenchymal stem cells aging by inhibiting mitophagy.

Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 277:1163922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cheng Y, Wang S, Zhang H, Lee JS, Ni C,

Guo J, Chen E, Wang S, Acharya A, Chang TC, et al: A non-canonical

role for a small nucleolar RNA in ribosome biogenesis and

senescence. Cell. 187:4770–4789.e23. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chicas A, Wang X, Zhang C, McCurrach M,

Zhao Z, Mert O, Dickins RA, Narita M, Zhang M and Lowe SW:

Dissecting the unique role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor

during cellular senescence. Cancer Cell. 17:376–387. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu G, Li X, Yang F, Qi J, Shang L, Zhang

H, Li S, Xu F, Li L, Yu H, et al: C-phycocyanin ameliorates the

senescence of mesenchymal stem cells through ZDHHC5-mediated

autophagy via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Aging Dis. 14:1425–1440.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wan D, Ai S, Ouyang H and Cheng L:

Activation of 4-1BB signaling in bone marrow stromal cells triggers

bone loss via the p-38 MAPK-DKK1 axis in aged mice. Exp Mol Med.

53:654–666. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gao Q, Wang L, Wang S, Huang B, Jing Y and

Su J: Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells: Identification,

classification and differentiation. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9:7871182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Infante A and Rodríguez CI: Osteogenesis

and aging: Lessons from mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther.

9:2442018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yin Y, Chen H, Wang Y, Zhang L and Wang X:

Roles of extracellular vesicles in the aging microenvironment and

age-related diseases. J Extracell Vesicles. 10:e121542021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tian B, Li X, Li W, Shi Z, He X, Wang S,

Zhu X, Shi N, Li Y, Wan P and Zhu C: CRYAB suppresses ferroptosis

and promotes osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow stem

cells via binding and stabilizing FTH1. Aging (Albany NY).

16:8965–8979. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gambari L, Grassi F, Roseti L, Grigolo B

and Desando G: Learning from monocyte-macrophage fusion and

multinucleation: Potential therapeutic targets for osteoporosis and

rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 21:60012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ma QL, Fang L, Jiang N, Zhang L, Wang Y,

Zhang YM and Chen LH: Bone mesenchymal stem cell secretion of

sRANKL/OPG/M-CSF in response to macrophage-mediated inflammatory

response influences osteogenesis on nanostructured Ti surfaces.

Biomaterials. 154:234–247. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chen J, Kuang S, Cen J, Zhang Y, Shen Z,

Qin W, Huang Q, Wang Z, Gao X, Huang F and Lin Z: Multiomics

profiling reveals VDR as a central regulator of mesenchymal stem

cell senescence with a known association with osteoporosis after

high-fat diet exposure. Int J Oral Sci. 16:412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li H, Qu J, Zhu H, Wang J, He H, Xie X, Wu

R and Lu Q: CGRP regulates the age-related switch between

osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9:6755032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Benisch P, Jakob F and Ebert R: Effects of

aging, primary osteoporosis and cellular senescence on human

mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One. 7:e514522012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

R Core Team, . R: A language and

environment for statistical computing (version 4.0.3). R Foundation

for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2020, https://www.R-project.org/October 16–2023

|

|

22

|

Hu M, Xing L, Zhang L, Liu F, Wang S, Xie

Y, Wang J, Jiang H, Guo J, Li X, et al: NAP1L2 drives mesenchymal

stem cell senescence and suppresses osteogenic differentiation.

Aging Cell. 21:e135512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang Y, Zhang W, Wang X, Yang J, Cui Y,

Song H, Li W, Li W, Wu L, Du Y, et al: A passage-dependent network

for estimating the in vitro senescence of mesenchymal stromal/stem

cells using microarray, bulk and single cell RNA sequencing. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 11:9986662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pánczél Á, Nagy SP, Farkas J, Jakus Z,

Győri DS and Mócsai A: Fluorescence-based real-time analysis of

osteoclast development. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6579352021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Huo S, Tang X, Chen W, Gan D, Guo H, Yao

Q, Liao R, Huang T, Wu J, Yang J, et al: Epigenetic regulations of

cellular senescence in osteoporosis. Ageing Res Rev. 99:1022352024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Qi L, Fang X, Yan J, Pan C, Ge W, Wang J,

Shen SG, Lin K and Zhang L: Magnesium-containing bioceramics

stimulate exosomal miR-196a-5p secretion to promote senescent

osteogenesis through targeting Hoxa7/MAPK signaling axis. Bioact

Mater. 33:14–29. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zheng Y, Wu S, Ke H, Peng S and Hu C:

Secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 in the senescence of bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells is regulated by autophagy via FoxO3a. Exp

Gerontol. 172:1120622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhang W, Huang C, Sun A, Qiao L, Zhang X,

Huang J, Sun X, Yang X and Sun S: Hydrogen alleviates cellular

senescence via regulation of ROS/p53/p21 pathway in bone

marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vivo. Biomed Pharmacother.

106:1126–1134. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tanaka Y, Sonoda S, Yamaza H, Murata S,

Nishida K, Hama S, Kyumoto-Nakamura Y, Uehara N, Nonaka K, Kukita T

and Yamaza T: Suppression of AKT-mTOR signal pathway enhances

osteogenic/dentinogenic capacity of stem cells from apical papilla.

Stem Cell Res Ther. 9:3342018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chen G, Wang S, Wei R, Liu Y, Xu T, Liu Z,

Tan Z, Xie Y, Yang D, Liang Z, et al: Circular RNA circ-3626

promotes bone formation by modulating the miR-338-3p/Runx2 axis.

Joint Bone Spine. 91:1056692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jin J, Huang R, Chang Y and Yi X: Roles

and mechanisms of optineurin in bone metabolism. Biomed

Pharmacother. 172:1162582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yin S, Lin S, Xu J, Yang G, Chen H and

Jiang X: Dominoes with interlocking consequences triggered by zinc:

Involvement of microelement-stimulated MSC-derived exosomes in

senile osteogenesis and osteoclast dialogue. J Nanobiotechnol.

21:3462023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Prince EW, Apps JR, Jeang J, Chee K,

Medlin S, Jackson EM, Dudley R, Limbrick D, Naftel R, Johnston J,

et al: Unraveling the complexity of the senescence-associated

secretory phenotype in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma using

multimodal machine learning analysis. Neuro Oncol. 26:1109–1123.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li J, Wang X, Nepovimova E, Wu Q and Kuca

K: Deoxynivalenol induces cell senescence in RAW264.7 macrophages

via HIF-1α-mediated activation of the p53/p21 pathway. Toxicology.

506:1538682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tragoonlugkana P, Pruksapong C, Ontong P,

Kamprom W and Supokawej A: Fibronectin and vitronectin alleviate

adipose-derived stem cells senescence during long-term culture

through the AKT/MDM2/P53 pathway. Sci Rep. 14:142422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bai L and Wang Y: Mesenchymal stem

cells-derived exosomes alleviate senescence of retinal pigment

epithelial cells by activating PI3K/AKT-Nrf2 signaling pathway in

early diabetic retinopathy. Exp Cell Res. 441:1141702024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang L, Deng Z, Li Y, Wu Y, Yao R, Cao Y,

Wang M, Zhou F, Zhu H and Kang H: Ameliorative effects of

mesenchymal stromal cells on senescence associated phenotypes in

naturally aged rats. J Transl Med. 22:7222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Geng N, Xian M, Deng L, Kuang B, Pan Y,

Liu K, Ye Y, Fan M, Bai Z and Guo F: Targeting the

senescence-related genes MAPK12 and FOS to alleviate

osteoarthritis. J Orthop Translat. 47:50–62. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kohli J, Veenstra I and Demaria M: The

struggle of a good friend getting old: Cellular senescence in viral

responses and therapy. EMBO Rep. 22:e522432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang H, Xu R, Li B, Xin Z, Ling Z, Zhu W,

Li X, Zhang P, Fu Y, Chen J, et al: LncRNA NEAT1 controls the

lineage fates of BMSCs during skeletal aging by impairing

mitochondrial function and pluripotency maintenance. Cell Death

Differ. 29:351–365. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Huang CY, Le HHT, Tsai HC, Tang CH and Yu

JH: The effect of low-level laser therapy on osteoclast

differentiation: Clinical implications for tooth movement and bone

density. J Dent Sci. 19:1452–1460. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhao Y, Wang C, Qiu F, Liu J, Xie Y, Lin

Z, He J and Chen J: Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes osteoclast

differentiation and oxidative stress by activating NF-κB pathway.

Aging (Albany NY). 16:9251–9263. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xie X, Hu L, Mi B, Panayi AC, Xue H, Hu Y,

Liu G, Chen L, Yan C, Zha K, et al: SHIP1 activator AQX-1125

regulates osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis through PI3K/Akt and

NF-κb signaling. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8260232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Li Y, Hu M, Xie J, Li S and Dai L:

Dysregulation of histone modifications in bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells during skeletal ageing: Roles and therapeutic prospects.

Stem Cell Res Ther. 14:1662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Shen Y, Hong Y, Huang X, Chen J, Li Z, Qiu

J, Liang X, Mai C, Li W, Li X and Zhang Y: ALDH2 regulates

mesenchymal stem cell senescence via modulation of mitochondrial

homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med. 223:172–183. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|