Introduction

Leukemia disrupts the homeostasis of the

hematopoietic system and causes abnormal proliferation of blast

cells (1). Acute myeloid leukemia

(AML), including its M2 subtype, reduces survival in adults;

therefore, establishing effective treatment strategies is critical

for improving prognosis (2,3).

Chemotherapy, such as the ‘7+3’ regimen, remains the standard

first-line treatment for AML. However, in some relapsed or

refractory cases, total body irradiation (TBI) is used as part of

conditioning regimens before hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation to eradicate residual leukemic cells (4,5).

Repeated exposure to radiation in such settings may, in rare cases,

contribute to the emergence of leukemic cells with reduced

radiosensitivity, potentially impeding complete remission. Although

the concept of ‘radiation-resistant AML’ is not widely recognized

in clinical settings, where resistance is more commonly associated

with chemotherapy, TBI has been implicated as a contributing factor

in therapy-related AML (6).

Furthermore, a phase II clinical trial evaluating treosulfan,

fludarabine, and low-dose TBI in pediatric and young adult AML/MDS

patients highlighted the clinical relevance and complex outcomes of

TBI-based regimens, including relapse and non-relapse mortality

(7). While radiation resistance is

not a routine concern in AML treatment, these findings support the

relevance of exploring the molecular basis of radiation

response.

In the present study, we employed an in vitro

AML model to investigate the acquisition of radioresistance.

Specifically, we previously established a radioresistant AML cell

line (Res-HL60) derived from HL60 cells, an AML M2 subtype cell

line of human origin, and investigated the molecular mechanisms

underlying radioresistance. Through repeated irradiation, the

Res-HL60 cells acquired smaller morphology, increased proliferative

potency, and showed elevated expression of CD38 cell surface

antigen and several mRNAs (8–12).

However, the upstream regulatory mechanism governing these gene

expression changes remains unclear, necessitating further

investigation.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), a class of noncoding RNAs that

regulate mRNA translation, have been implicated in cancer

progression and cell behavior, and their expression patterns are

increasingly recognized as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers

(13,14). Additionally, miRNAs have emerged as

potential therapeutic targets in cancer. Despite this, the profile

of miRNA expression in radioresistant AML cells such as Res-HL60

has not been previously reported. Given that chromosomal

abnormalities, epigenetic dysregulation, and impaired miRNA

biogenesis, potentially triggered by frequent radiation exposure,

can all influence miRNA expression (15), investigating these changes may help

clarify the molecular basis of acquired radioresistance. Therefore,

in this study, we performed transcriptome analysis focusing on

miRNA expression in Res-HL60 cells to explore mechanisms associated

with radioresistance in AML.

Materials and methods

Leukemia cell line and culture

The human AML cell line HL60 (wild-type: Wt-HL60)

was obtained from the RIKEN BioResource Center. The Res-HL60 cell

line was generated by exposing Wi-HL60 cells to 4-Gy irradiation

per week for 4 weeks. Wt-HL60 and Res-HL60 cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with

10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Japan Bioserum, Inc.) and

1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. In this

study, the control group was defined as non-irradiated Wt-HL60

cells cultured under these standard conditions (5% CO2

and 95% air). The characteristics of Res-HL60 cells, including

higher proliferative capacity, smaller cell size and altered

chemical reactivity, have been reported previously by our group

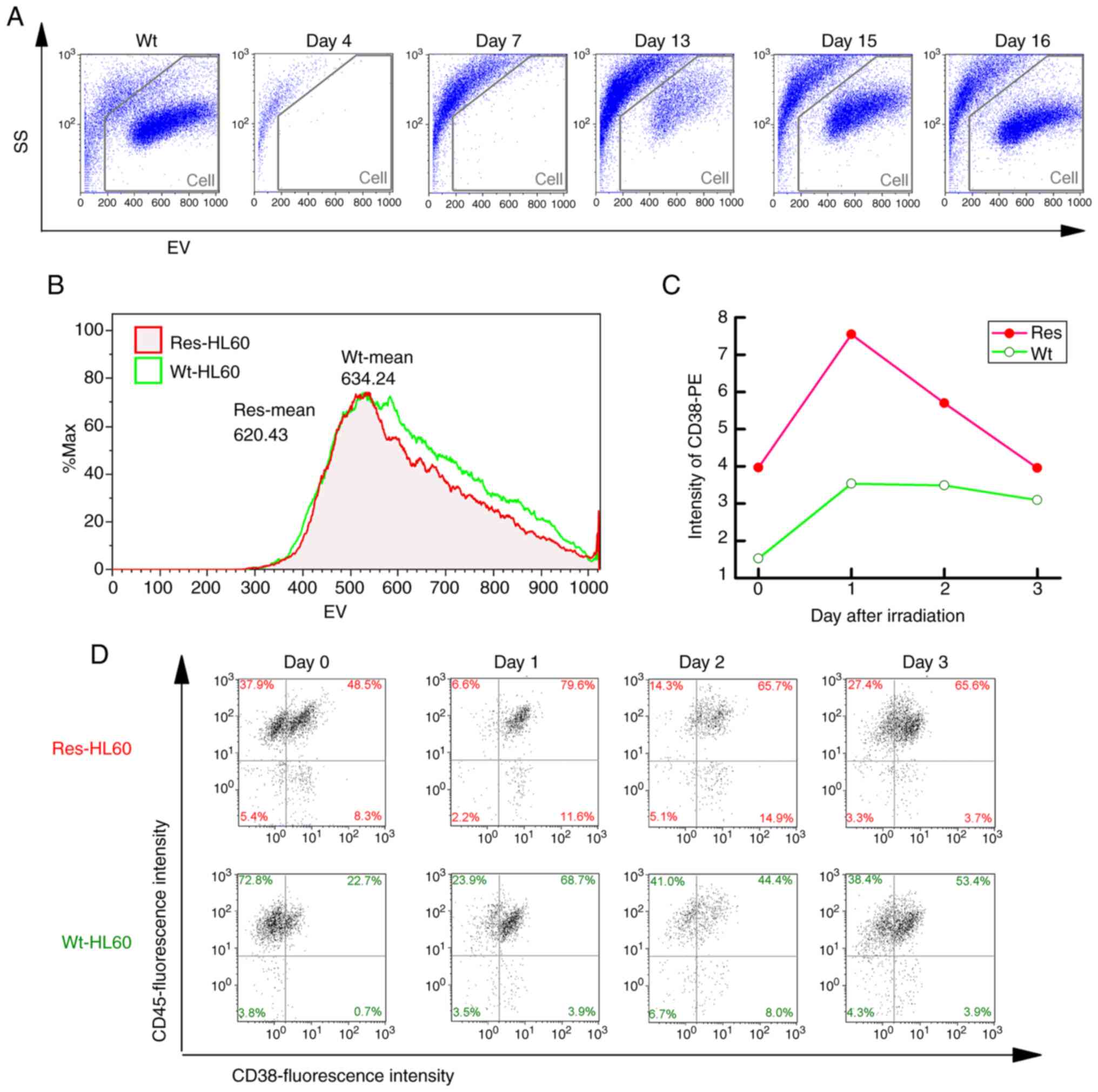

(8–12). In the present study, a time-course

analysis of morphological changes in Res-HL60 cells was conducted

(Fig. 1). Cells were initially

seeded at a density of 2×105 cells/ml on Day-1. X-ray

irradiation was performed on Day 0. On Day 2 (i.e., the third day

after initial seeding), cells were passaged and reseeded at

2×105 cells/ml. When the cell density remained below

2×105 cells/ml, only medium replacement was performed.

No additional supplements (e.g., non-essential amino acids, sodium

pyruvate) were added. To calculate the cumulative total viable cell

number including all passages, the following formula was used:

Cumulative cell number (/ml)=A × [(2×105) +

B]/(2×105), where ‘A’ is the viable cell number

(cells/ml) measured up to Day 2 (before passaging), and ‘B’ is the

net increase in viable cell number (cells/ml) from Day 3 onward,

relative to the reseeded density (2×105 cells/ml). B=0

for Days 0–2. This method allowed us to reflect the overall

proliferation dynamics across reseeding and media replacement

steps. The updated y-axis label in Fig. 2A and B reflects this definition. To

confirm the identity and authenticity of the cell lines used in

this study, short tandem repeat (STR) profiling was performed. The

STR profiles of both Wt-HL60 and Res-HL60 showed a perfect match

with the reference profile for HL60 (Cellosaurus ID: CVCL_0002,

URL: http://www.cellosaurus.org/CVCL_0002), as provided by

the RIKEN BioResource Center, indicating no evidence of

contamination or misidentification. The STR profiles are provided

in Fig. S1 and Table SI.

Irradiation

X-ray irradiation (150 kVp, 20 mA with 0.5-mm

aluminum and 0.3-mm copper filters) was performed using an X-ray

generator (MBR-1520R-3; Hitachi Medical Co., Ltd.) at a distance of

45 cm between the focus and target. The dose was monitored during

irradiation using a thimble ionization chamber set next to the

sample. The dose rate was 1 Gy/min. The cultured cells were exposed

to X-rays as previously described (8–12).

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry was performed using Cell Lab

Quanta™ Sc MPL system (Beckman Colter Immunotech) to

assess cell size, granularity, and CD38 surface expression. Unlike

conventional flow cytometers that use forward scatter to estimate

cell size, the Cell Lab Quanta utilizes Electric Volume (EV), which

is based on the Coulter principle, to directly measure cell size

via changes in electrical resistance as cells pass through an

aperture. This method allows for accurate assessment of cell volume

independent of optical scattering. Granularity, representing

internal cellular complexity, was evaluated based on side scatter

(SSC) intensity, as is standard in flow cytometry. CD38 expression

was also assessed due to its dual relevance as both a hematopoietic

differentiation marker and a potential indicator of acquired

radioresistance. CD38 is a well-characterized surface antigen known

to be markedly upregulated during granulocytic differentiation of

HL60 cells (16). Furthermore, our

previous studies demonstrated sustained CD38 expression in Res-HL60

cells even in the absence of differentiation-inducing agents,

suggesting a role in the radioresistant phenotype (8–12).

Based on these findings, CD38 was utilized in this study both as a

marker of differentiation and as a surrogate indicator of radiation

resistance.

DNA fragmentation

The Comet Assay Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis

Assay (cat. no. 4250-050-K; TREVIGEN, Inc., Gaithersburg, USA) was

used to evaluate the DNA fragments of the cells irradiated with

X-rays. One day after seeding in a 60-mmφ culture dish at a

concentration of 1.0×105 cells/ml, the cells were

irradiated with 1–4 Gy of X-rays, and the cells were collected

after 24 h. The collected cells were fixed on glass slide

(Matsunami Grass Inc., Osaka, Japan) using LM Agarose (TREVIGEN

Inc.). The glass slide to which the sample was attached was

immersed in an alkaline solution [200-mM NaOH, 1-mM

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)], and electrophoresis (21 V,

3 A, 30 min, 4°C) was performed. After washing the glass slide with

distilled water and 70% EtOH and drying, it was stained with 100 µl

of a staining solution containing a mixture of SYBR Green (TREVIGEN

Inc.) and TE Buffer (10-mM Tris, 1-mM EDTA). After drying, the tail

moment was observed using a fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS Inc.).

Images were taken using Comet Assay IV (Instem, Conshohocken, USA)

for observation purposes. Tail moment was calculated using the

formula: Tail Moment=Tail Length × % Tail DNA/100, using Comet

Assay IV software. This calculation reflects both the extent and

the intensity of DNA fragmentation in individual cells.

Extraction of total RNAs from

cells

Total intracellular RNAs (four replicates performed

in parallel) were extracted using ISOGEN II (Nippon Gene Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purity and

concentration of extracellular RNAs were assessed using a NanoDrop

spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo-Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The RNA samples had 260/280-nm absorbance ratios of 1.8–2.0.

Furthermore, the peaks of the small RNAs were confirmed using an

Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Microarray analysis of miRNAs

SurePrint G3 human miRNA 8×60-K Microarray (Agilent

Technologies Inc.) was used to analyze intracellular microRNA

expression. Cyanine 3 labeling was performed with 1 ng of

intracellular microRNA using an miRNA Complete Labeling and

Hybridization kit (Agilent Technologies Inc.), following the

manufacturer's instructions. After hybridization and washing of the

microarray slide, fluorescence image scanning was performed using a

SureScan G 2600 D (Agilent Technologies Inc.). The expression data

were processed using GeneSpring GX14.5 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.)

to normalize the quantiles of all values in the respective

microarrays. The obtained microarray data were registered with the

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (GSE285934).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) analysis

First-strand cDNA was synthesized using

Mir-X™ miRNA First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Takara Bio

Inc., Otsu, Japan; Cat. Nos. 638313) according to the

manufacturer's protocol (Protocol No. PT5001-1). MiRNA expression

was assessed by qPCR using TB Green Advantage qPCR Premix (Takara

Bio Inc., Cat. Nos. 639676) on a SmartCycler® II system

(Takara Bio Inc.). The thermocycling conditions were as follows:

95°C for 10 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C

for 20 sec. Relative miRNA expression levels were calculated using

the 2−ΔΔCq method. U6 small nuclear RNA, included as an

internal control primer set in the Mir-X™ First-Strand

Synthesis Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Cat. Nos. 638313), was used for

normalization. The exact primer sequences for U6 were not publicly

disclosed, and direct inquiries to the manufacturer did not yield

this information. However, the Mir-X™ system is widely

used and has been independently validated in numerous peer-reviewed

studies for reliable miRNA quantification. We adhered strictly to

the manufacturer's standardized protocol to ensure data

reproducibility and accuracy. For the analysis ΔCq was calculated

as (Cq of target miRNA-Cq of U6). ΔΔCq was defined as (ΔCq of

Res-HL60-ΔCq of Wt-HL60), and fold change was calculated as

2−ΔΔCq, with Wt-HL60 set as the baseline (fold change-1)

(17). Sequences of the target

miRNAs were obtained from the miRBase database (https://www.mirbase.org/). MiRNA-specific forward

primers were synthesized by Eurofins Genomics Inc. and are listed

in Table I. A universal reverse

primer provided in the Mir-X™ kit was used for all

miRNAs. The Mir-X™ qRT-PCR system employs a

poly(A)-tailing strategy followed by reverse transcription with an

adapter-anchored oligo(dT) primer. This approach selectively

amplifies mature polyadenylated miRNAs, while excluding pre-miRNAs,

long non-coding RNAs, and host transcripts lacking poly(A) tails.

The specificity of the amplification was further supported by the

observation of single, sharp melt curve peaks in all reactions.

| Table I.Sequences of miRNA primers for

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Sequences of miRNA primers for

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Primer name | Accession no. | Sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| hsa-miR-3612 | MIMAT0017989 |

AGGAGGCATCTTGAGAAATGGA |

| hsa-miR-324-5p | MIMAT0000761 |

CGCATCCCCTAGGGCATTGGTG |

|

hsa-miR-146a-5p | MIMAT0000449 |

TGAGAACTGAATTCCATGGGTT |

| hsa-miR-1246 | MIMAT0005898 |

AATGGATTTTTGGAGCAGG |

|

hsa-miR-3190-3p | MIMAT0022839 |

TGTGGAAGGTAGACGGCCAGAGA |

|

hsa-miR-3156-5p | MIMAT0015030 |

AAAGATCTGGAAGTGGGAGACA |

| hsa-miR-124-3p | MIMAT0000422 |

TAAGGCACGCGGTGAATGCCAA |

| hsa-miR-9-3p | MIMAT0000442 |

ATAAAGCTAGATAACCGAAAGT |

| hsa-miR-324-3p | MIMAT0000762 |

CCCACTGCCCCAGGTGCTGCTGG |

| hsa-let-7e-5p | MIMAT0000066 |

TGAGGTAGGAGGTTGTATAGTT |

| hsa-miR-3669 | MIMAT0018092 |

TACGGAATATGTATACGGAATAT |

| hsa-miR-29b-3p | MIMAT0000100 |

TAGCACCATTTGAAATCAGTGTT |

|

hsa-miR-30c-1-3p | MIMAT0004674 |

CTGGGAGAGGGTTGTTTACTCC |

| hsa-miR-671-5p | MIMAT0003880 |

AGGAAGCCCTGGAGGGGCTGGAG |

| hsa-miR-425-5p | MIMAT0003393 |

AATGACACGATCACTCCCGTTGA |

| hsa-miR-345-5p | MIMAT0000772 |

GCTGACTCCTAGTCCAGGGCTC |

| hsa-miR-610 | MIMAT0003278 |

TGAGCTAAATGTGTGCTGGGA |

| hsa-miR-4260 | MIMAT0016881 |

CTTGGGGCATGGAGTCCCA |

|

hsa-miR-376c-3p | MIMAT0000720 |

AACATAGAGGAAATTCCACGT |

| hsa-miR-512-3p | MIMAT0002823 |

AAGTGCTGTCATAGCTGAGGTC |

| hsa-miR-744-3p | MIMAT0004946 |

CTGTTGCCACTAACCTCAACCT |

| hsa-miR-27b-3p | MIMAT0000419 |

TTCACAGTGGCTAAGTTCTGC |

| hsa-miR-7-2-3p | MIMAT0004554 |

CAACAAATCCCAGTCTACCTAA |

| hsa-miR-769-3p | MIMAT0003887 |

CTGGGATCTCCGGGGTCTTGGTT |

|

hsa-miR-3675-5p | MIMAT0018098 |

TATGGGGCTTCTGTAGAGATTTC |

| hsa-miR-101-5p | MIMAT0004513 |

CAGTTATCACAGTGCTGATGCT |

| hsa-miR-20b-5p | MIMAT0001413 |

CAAAGTGCTCATAGTGCAGGTAG |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Origin

software package (Pro version 9.0; OriginLab Corporation,

Northampton, MA, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office 365).

To evaluate the statistical significance of differences between the

control and experimental groups, an unpaired Student's t-test was

used, as the data met assumptions for parametric testing. All

results are presented as the mean ± SEM based on four independent

experiments. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Analysis of cell damage exposed to

IR

The cell population exposed to 4-Gy radiation

temporarily disappeared but reappeared on days 15–16 (Fig. 1A). However, it was confirmed that

Res-HL60 had a decreased EV (Wt: 634.24, Res: 620.43) (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the expression of

the CD38 cell surface antigen in Res-HL60 cells was significantly

increased after radiation compared with that in the wild-type cells

(maximum on day 1: Res=7.55±0.53, Wt=3.54±0.89), confirming a

similar previously reported response (Fig. 1C and D). In our previous study, we

evaluated CD38 as a differentiation marker and found that its

expression was consistently elevated in Res-HL60 cells (8). The Res-HL60 cells seeded at

1×105 cells/ml exhibited approximately 30-fold

proliferation (3.1±0.4×105 cells/ml) on day 5, and the

Wt-HL60 cells exhibited approximately 15-fold proliferation

(1.6±0.1×105 cells/ml) (Fig. 2A). The 4-Gy irradiation condition

of Res-HL60 cells was also maintained approximately 5-fold after

exposure on day 4 (4.9±0.5×105 cells/ml); however, it

remained at the level observed on day 0 in Wt-HL60 cells

(1.9±0.1×105 cells/ml) (Fig. 2B). The extent of DNA damage caused

by radiation exposure in these cells was determined using a comet

assay (Fig. 2C). The tail moment

of Res-HL60 cells irradiated with 1–4 Gy was similar to that

observed in cells without irradiation, whereas the tail moment of

Wt-HL60 cells exposed to irradiation was significantly increased

(Fig. 2D).

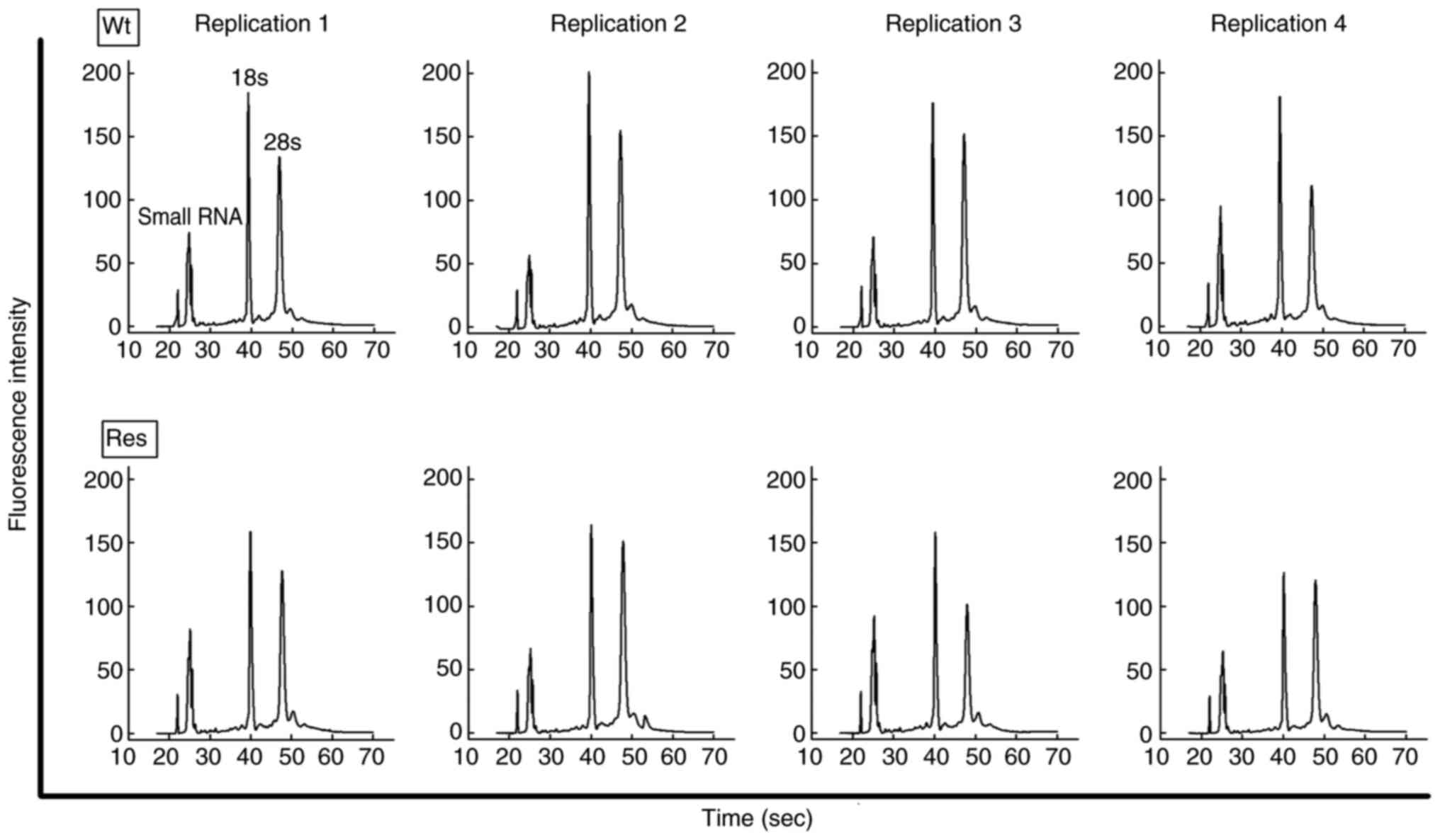

Expression profiles of miRs

To clarify the miRNA expression profiles of Res-HL60

cells, total RNAs were extracted from these cells. Using an Agilent

bioanalyzer, the extracted total RNAs were confirmed to have an RIN

value (max-10) and rRNA 18s and 28s peaks, which reveal whether

small RNAs, including miRNAs, are of sufficient concentration and

quality for analysis (Fig. 3).

Total RNAs extracted from each cell exhibited an RIN >9 in all

samples. Furthermore, the peak of small RNAs, 18s, and 28s in the

histogram was cleared, and these samples were considered to have

good quality for RNA analysis (Table

II).

| Table II.Concentration and quality of total

RNA extracted from Res-HL60 cells and Wt-HL60 cells. |

Table II.

Concentration and quality of total

RNA extracted from Res-HL60 cells and Wt-HL60 cells.

| Sample list | Concentration of

total RNA, µg/106 cells | RNA integrity

number | Ratio of rRNA,

28s/18s |

|---|

| Wt |

|

|

|

|

Replication 1 | 3.6 | 9.5 | 1.03 |

|

Replication 2 | 5.6 | 9.5 | 0.98 |

|

Replication 3 | 6.5 | 9.6 | 1.16 |

|

Replication 4 | 4.4 | 9.1 | 0.84 |

| Mean ±

SE | 5.0±0.6 | 9.4±0.1 | 1.0±0.1 |

| Res |

|

|

|

|

Repliction 1 | 5.5 | 9.4 | 0.98 |

|

Replication 2 | 4.3 | 9.6 | 1.18 |

|

Replication 3 | 3.6 | 9.2 | 0.76 |

|

Replication 4 | 4.1 | 9.6 | 1.13 |

| Mean ±

SE | 4.4±0.3 | 9.5±0.1 | 1.0±0.1 |

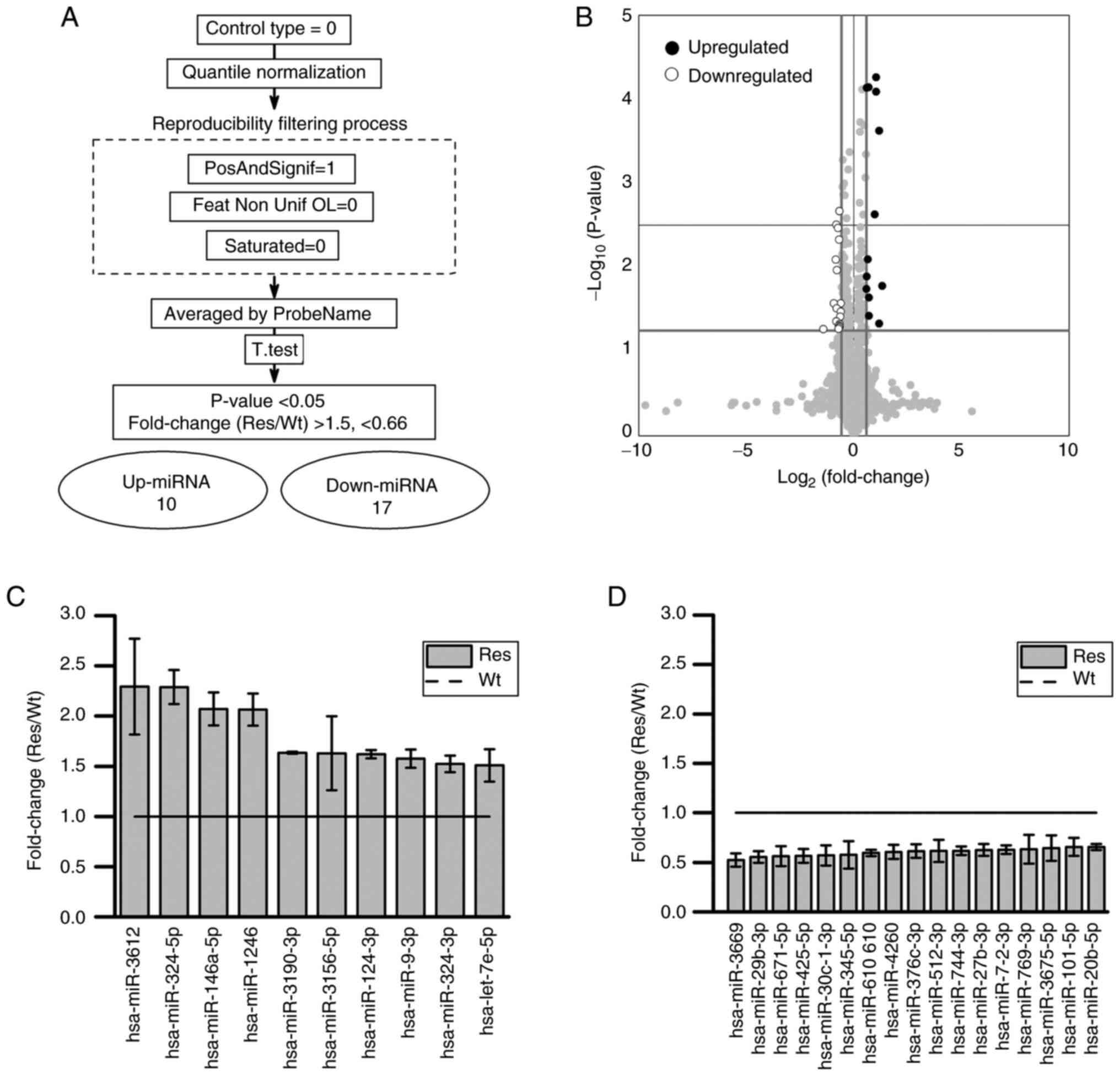

After miRNA microarray analysis, data were extracted

after quantile normalization, excluding under background, and

collection of unsaturated signals (Fig. 4A). After processing, the signal

values obtained using multiple types of detection probes were

averaged for each miRNA name, yielding 1,187 miRNA data. Among the

miRNAs that significantly increased or decreased in Res compared

with Wt, 10 miRNAs had a fold change (Res/Wt) >1.5, and 17

miRNAs had a fold change (Res/Wt) <0.66 (Fig. 4B-D). For the 27 miRNAs that

exhibited expression changes in the microarray analysis, a

functional enrichment analysis using the Reactome Pathway Database

in OmicsNet 2.0 was performed to estimate the associated mRNA

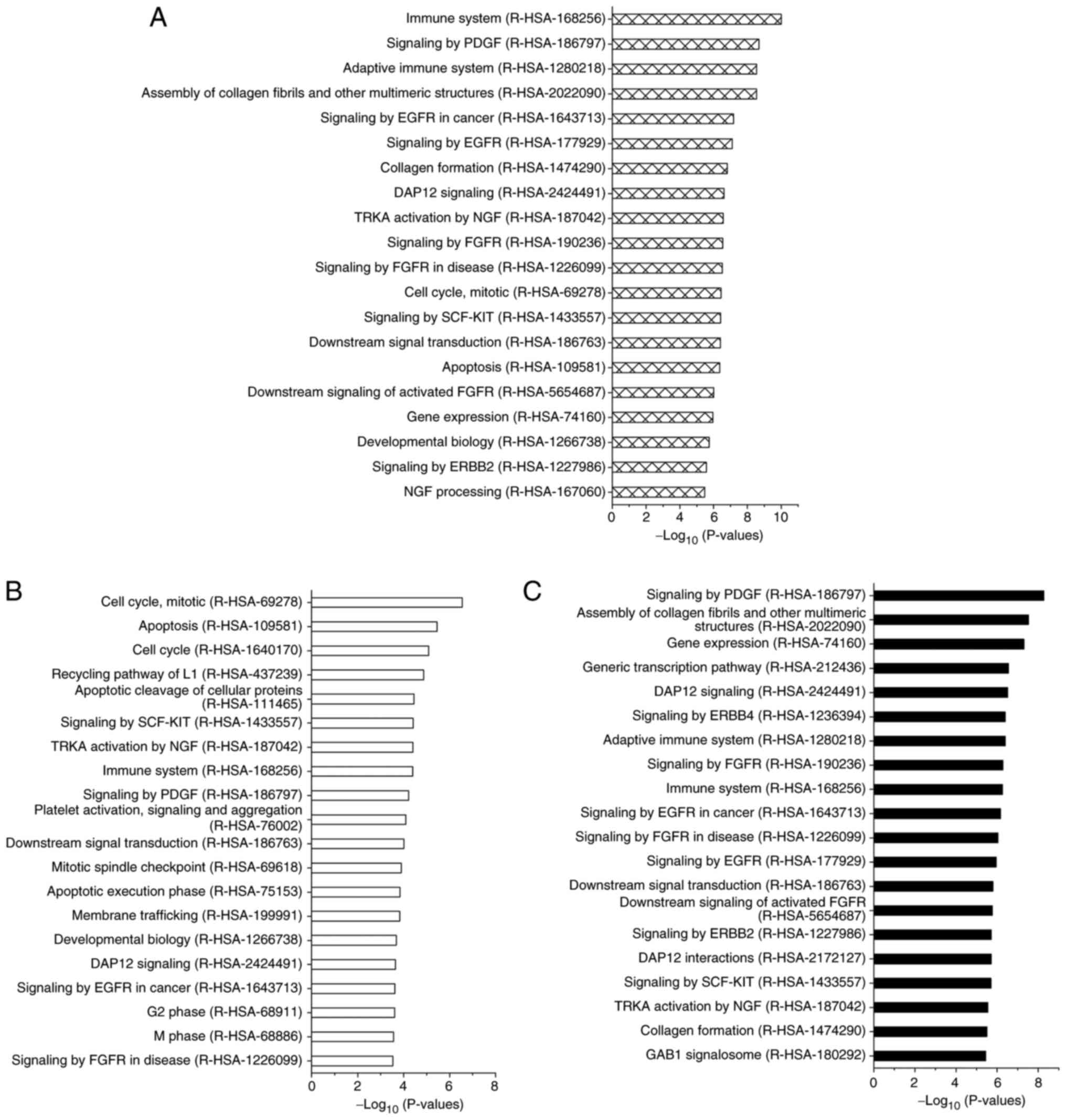

expression pathways. Cellular functional changes were observed in

the following pathways: ‘Immune System (R-HAS-168256)’, ‘Signaling

by PGDF (R-HAS-186797)’, ‘Adaptive Immune System (R-HAS-1280218)’,

‘Signaling by EGFR in Cancer (R-HAS-1643713)’, ‘Apoptosis

(R-HAS-109581)’, and ‘Cell Cycle, Mitotic (R-HAS-69278)’ for tumor

growth and/or invasion (Fig.

5A).

Furthermore, when we focused on the functional

analysis of the target mRNAs of the 10 upregulated miRNAs in

Res-HL60 cells, these mRNAs were strongly related to the following

functional pathways: ‘cell cycle’, ‘cell division’ and ‘apoptosis’

(Fig. 5B). In contrast, the target

mRNAs of the 16 downregulated miRNAs in Res-HL60 cells were

strongly related to the following functional pathways: ‘Signaling

by PDGF’ and ‘Assembly of collagen fibrils and other multimeric

structures (R-HAS-2022090)’ (Fig.

5C).

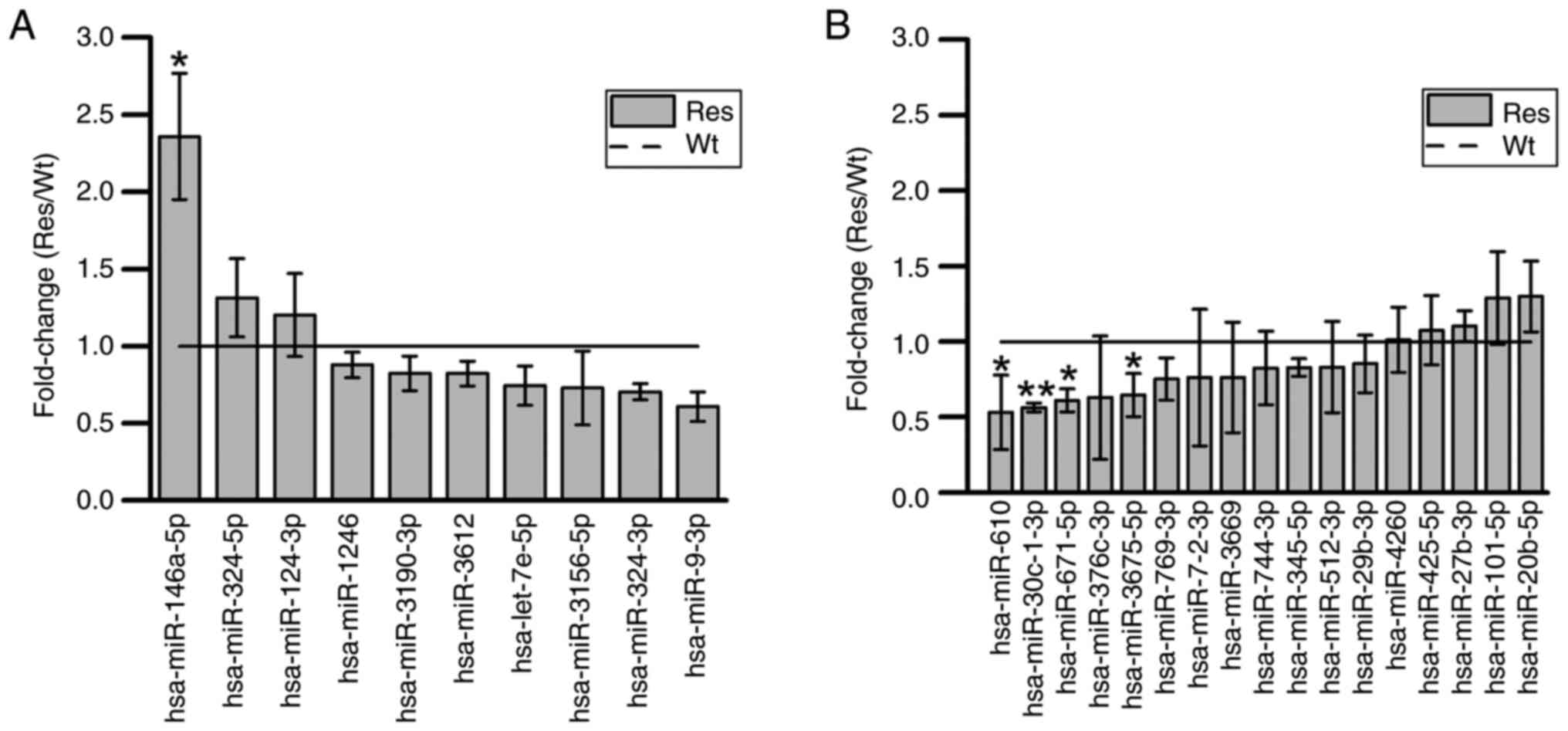

Validation of the expression of 27

miRNAs

The significant expression of the 27 miRNAs obtained

from these microarray analysis signals was reconfirmed by RT-qPCR.

Thus, the expression of miRNA-146a-5p was significantly increased,

whereas the expression of miRNA-30c-1-3p, miRNA-671-5p, miRNA-610,

and miRNA-3675-5p was significantly decreased (Fig. 6).

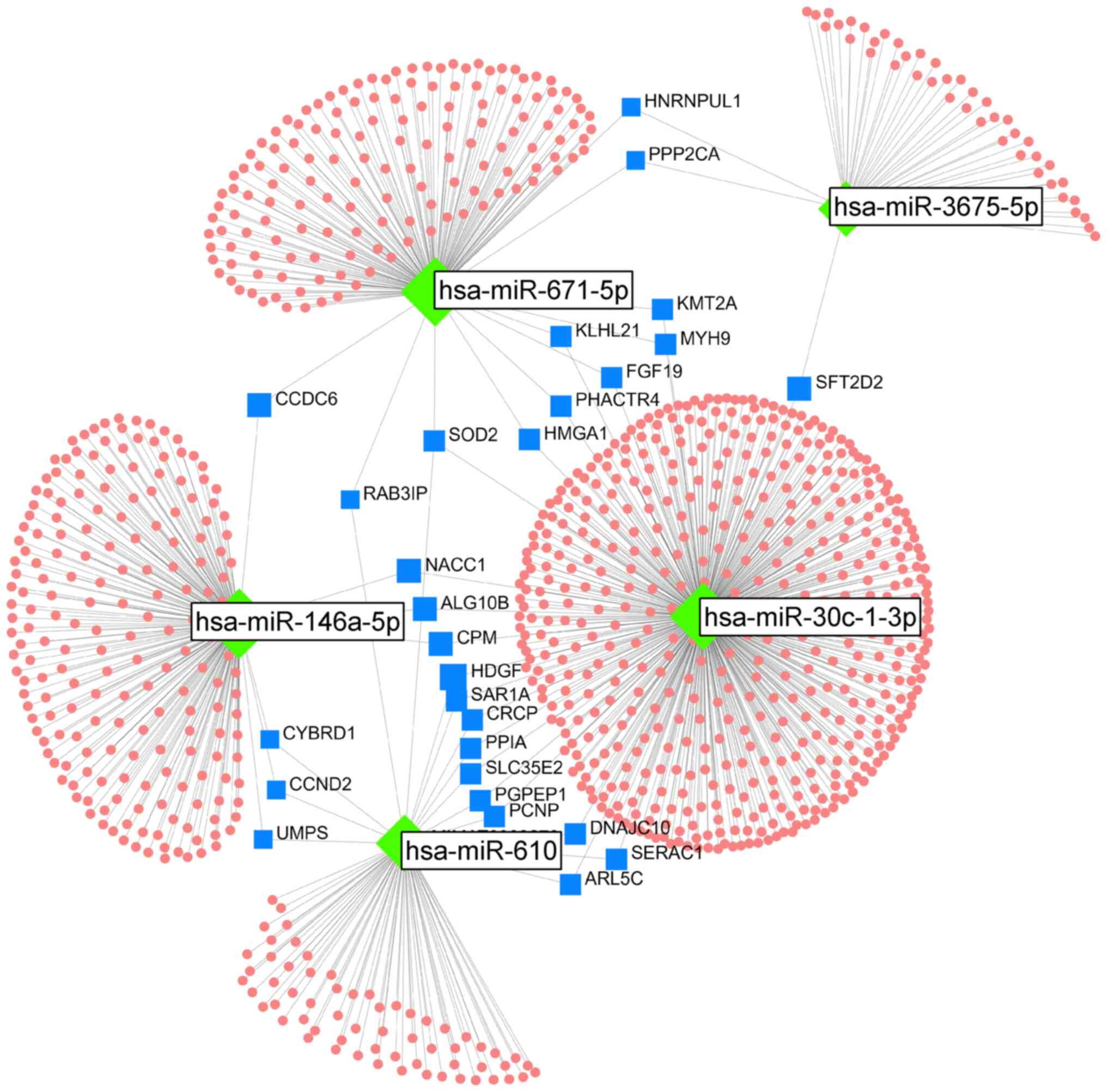

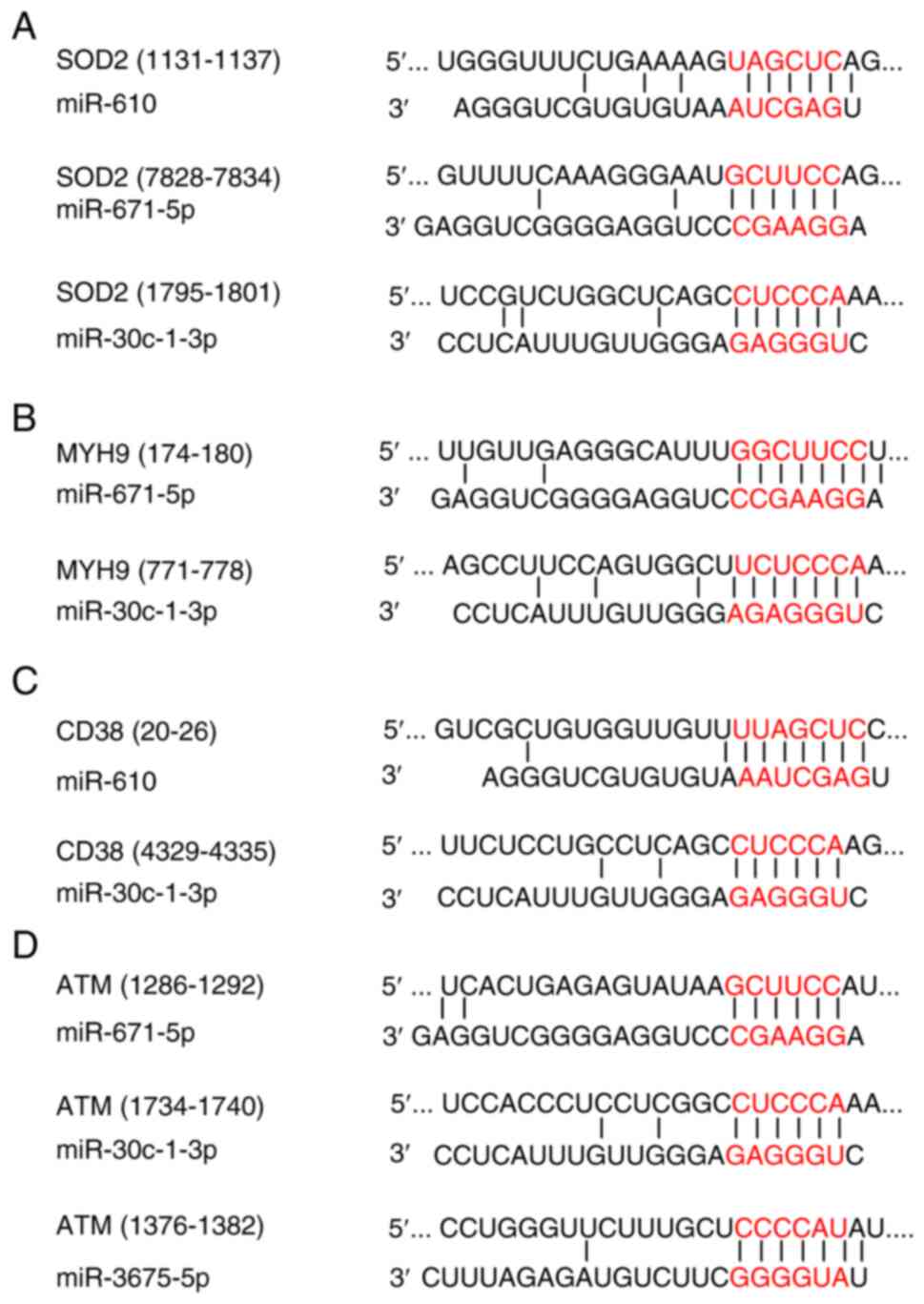

Analysis of bioinformatics: The mRNA networks

controlled by the five reproduced miRNAs were analyzed using

OmicsNet 2.0. In this network, 28 mRNAs were associated with two or

more miRNAs (Fig. 7). Of these 28

target mRNAs, seven (i.e., ALG10B, CCDC6, CCND2, CPM, CYBRD1,

NACC1, and UMPS) were targeted by miRNA-146a-5p, which is an

upregulated miRNA, and the other four miRNAs, which are

downregulated. Furthermore, three miRNAs (i.e., miRNA-610,

miRNA-671-5p, and miRNA-30c-1-3p) targeted superoxide dismutase 2

(SOD2). In the Target Scan analysis, three miRNAs (miRNA-610,

miRNA-671-5p, and miRNA-30c-1-3p) were predicted to bind to the

3′-UTR region of SOD2, which was predicted as the target mRNA

(Fig. 8). Furthermore, two miRNAs

(i.e., miRNA-671-5p and miRNA-30c-1-3p) were predicted to bind to

the 3′-UTR region of MYH9 mRNA. The putative target sites of

miR-610 and miR-30c-1-3p for CD38 mRNA and miR-3675-5p, miR-671-5p,

and miR-30c-1-3p for ATM mRNA were located in the 3′-UTR

region.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the miRNA expression

profile of a radioresistant AML cell model (Res-HL60) derived from

the HL60 cell line, which belongs to the FAB M2 subtype of AML. We

reconfirmed that Res-HL60 cells, which were established by repeated

irradiation of HL60 cells, maintained the morphological

characteristics previously described, even when remade (Fig. 1). The HL60 cell line, which is

derived from a patient with AML, exhibits inherently low CD38

expression, as previously reported (18). We have previously evaluated CD38 as

a differentiation marker and found that its expression was

consistently elevated in Res-HL60 cells (8). In this study, we observed transient

increases in CD38 expression immediately after irradiation. This

upregulation has been reported to be associated with cellular

activation and proliferation (19). CD38 was selected as the primary

marker in this study because it is a well-established

differentiation-associated antigen in the HL60 model system; its

expression increases markedly during granulocytic differentiation,

as demonstrated by Partida-Sánchez et al (16). In our Res-HL60 cells, CD38

consistently showed strong upregulation both under baseline

conditions and immediately after irradiation. These observations,

combined with CD38′s known roles in NAD+-dependent

calcium signaling and immune modulation, made it a biologically

relevant candidate for investigating radioresistant phenotypes in

AML. Although Breitman et al broadly discussed the HL60

differentiation model, CD38-specific functional insights were

established in later work (20).

In this context, ‘cellular activation’ refers to an increased

responsiveness of cells to external stimuli, such as radiation,

typically accompanied by changes in surface markers, including CD38

upregulation. Although direct functional activation markers were

not assessed in this study, similar CD38 upregulation has been

correlated with cell activation and immune modulation in leukemia

models. Our previously established Res-HL60 cells demonstrated

enhanced proliferative capacity compared to Wt-HL60 cells, as

evidenced by shortened population doubling times and increased

viable cell counts (8–12). Although these proliferation

characteristics were not re-evaluated in the present study, the

phenotypic stability and CD38 expression patterns observed here are

consistent with those findings.

Furthermore, DNA fragments did not increase in these

cells due to radiation, and the response was confirmed to be

similar to γ-H2AX, a marker for DNA double-strand breaks, and to

previous DNA ladder analyses (9,21).

In these damage responses in Res-HL60 cells, 27 miRNAs (10

upregulated and 17 downregulated) showed altered expression in the

microarray analysis. Among them, five miRNAs (miR-146a-5p,

miR-30c-1-3p, miR-671-5p, miR-610, and miR-3675-5p) consistently

demonstrated significant changes in the same direction across both

microarray and RT-qPCR validation experiments. This consistency

suggests that these five miRNAs may play a regulatory role in

modulating molecular pathways associated with the development of

radiation resistance. These five miRNAs have been implicated in

tumor proliferation, radiosensitivity, and hematopoiesis (22–30).

miR-146a functions together with TRAF1 and IRAK1 as negative

feedback factors for the two toll-like receptor pathway proteins

(22). It is also involved in

regulating the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, which is

necessary for the differentiation of hematopoietic cells (23,24).

In radiotherapy for meningioma, the expression of miR-30c-1-3p is

suppressed when treatment resistance occurs (25). In another report, the suppression

of miR-30c-1-3p expression was associated with the progression of

prostate cancer (26). The

overexpression of miR-671-5p has been shown to significantly

increase apoptosis and DNA damage in human glioblastoma cells

(27). In neuroblastoma cells, the

overexpression of miR-610 induces apoptosis and reduces cell

viability (28). miR-3651 promotes

the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal cancer

cells (29,30). These reports from various cell

types suggest that changes in miRNA expression in radioresistant

AML are triggered by cell viability activity.

The analysis of linking target mRNA networks of five

miRNAs with radioresistant AML is new information, and 11 target

mRNAs of these miRs (i.e., ALG10B, CCDC6, CCND2, CPM, CYBRD1,

NACC1, UMPS, SOD2, MYH9, CD38, and ATM) may regulate the expression

of its associated proteins and transcription factors in a complex

manner. SOD2 can scavenge active oxygen produced by radiation

irradiation, and SOD2 has been reported to protect against cellular

stress (31). Furthermore, MYH9 is

involved in cell division, cell migration, and maintenance of cell

morphology and acts as an antiapoptotic agent in head and neck

cancers where MYH9 is highly expressed (32). Moreover, it also reduces

intracellular reactive oxygen species levels through the activation

of the MAPK signaling pathway and Nrf2/keap1 pathway and the

promotion of the production of the antioxidant enzyme GCLC. It is

also involved in radioresistance. This observation may also explain

the morphological stability and resistance to radiation-induced

apoptosis observed in Res-HL60 cells. To further investigate the

clinical relevance of these target genes, we examined publicly

available AML gene expression datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Yu et al have

reported that MYH9 overexpression was significantly associated with

poor prognosis in patients with AML based on TCGA-LAML data

(33). This finding is also

supported by GSE12417 (GEO), a dataset originally published by

Metzeler et al (34), which

includes cytogenetically normal AML cases. In a recent analysis by

Zhai et al (35), MYH9 was

among the genes linked to adverse outcomes in this cohort.

Expression of ATM, although not frequently mutated in AML, has been

implicated in treatment responses; low ATM expression enhances

sensitivity to FLT3 inhibitors and may affect DNA damage signaling

(36). SOD2 has not been directly

studied in AML; however, it plays a key role in scavenging reactive

oxygen species. A meta-analysis of pan-cancer TCGA datasets by Noh

et al (31) reported that

SOD2 upregulation is associated with treatment resistance,

suggesting its potential role in radioresistant phenotypes. We note

that original survival analyses were not performed in this study.

Instead, we relied on published results from previous analyses of

these public datasets. This approach was taken due to the

experimental focus of our study on the HL60-derived model. However,

we fully acknowledge the importance of such analyses in increasing

the translational relevance of our findings. While we agree with

the reviewer's suggestion to perform updated survival analyses

using the most recent TCGA and GEO datasets, this was beyond the

scope of the current in vitro study. Nonetheless,

incorporating such analyses is a clear objective for future work.

We plan to conduct comprehensive bioinformatics evaluations of

MYH9, ATM, and SOD2 expression in larger patient cohorts using

integrated clinical and molecular data. Furthermore, the use of

radiation-resistant AML patient samples to validate these gene

targets was not feasible in the present study due to sample

unavailability. However, this represents a crucial next step.

Future studies will aim to collect and analyze patient-derived AML

samples, particularly from individuals with known radiation

treatment history, to directly confirm the relevance of MYH9, ATM,

and SOD2 in clinical radioresistance. These findings complement our

in vitro results and support the relevance of SOD2, ATM, and

MYH9 in AML radioresistance.

Most functions inferred from the Reactome analysis

were related to anti-apoptotic processes and were associated with

upregulated miR-146a-5p. Our original hypothesis was that

miR-146a-5p promotes apoptosis by inhibiting antiapoptotic

molecules, thereby enhancing radiosensitivity in Res-HL60 cells.

However, the results of the inhibition of anti-apoptotic molecules

did not support this hypothesis. Instead, these findings suggest

that miR-146a-5p regulates an alternative pathway that could

contribute to radiation resistance. Target-scan analysis

revealed that the high expression of CD38 cell surface antigen

protein, CD38 mRNA, and intracellular ATM is related to the

regulation of the five miRNAs revealed here (Fig. 8). These miRNA regulations provide

molecular biology information supporting previous cellular

responses. This information enhances our understanding of the

molecular mechanisms underlying radiation resistance in AML. To

further elucidate the mechanisms linking CD38 expression and

radiation resistance, our future studies will focus on dissecting

the intracellular signaling pathways downstream of CD38.

Specifically, we plan to investigate NAD+ metabolism and

calcium signaling pathways, both of which are regulated by CD38 and

are known to affect cell survival, DNA repair capacity, and

oxidative stress responses. These pathways may provide crucial

mechanistic links between CD38 expression and the observed

radioresistant phenotype in AML cells. In addition, combining CD38

expression analysis with metabolic profiling may help clarify its

functional relevance in therapeutic resistance. This approach may

also reveal novel therapeutic targets to overcome resistance in

CD38-expressing AML subtypes. Although CD38 was a useful marker in

our initial evaluation, we recognized that other markers, such as

CD34, CD123, and ALDH are also relevant in the context of leukemia

stemness and therapy resistance. Exploring the role of these

markers was not within the scope of this study. However, future

studies incorporating a broader panel of surface markers are

warranted to further elucidate the mechanisms of AML

radioresistance.

One limitation of this study is the lack of a

regulatory analysis for the expression of the five miRNAs in AML

cells, including investigations of intracellular signaling pathways

and knockdown of the 11 predicted target mRNAs. Another limitation

is that all experiments were performed using a single cell line,

HL60, and its derived radioresistant subline. Although HL60 is a

widely used model for AML studies, it does not capture the full

genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of AML, which can

significantly affect radiosensitivity and miRNA profiles.

Therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing these

findings. Future studies should include additional AML cell lines

representing different molecular subtypes, as well as

patient-derived primary cells, to validate the observed miRNA and

mRNA expression patterns. Furthermore, functional assays using

miRNA mimics/inhibitors or siRNA-mediated knockdown of key targets

such as MYH9, ATM, and SOD2 are necessary to directly confirm their

roles in radiation resistance. Such validations will be crucial for

establishing the broader applicability and clinical relevance of

our findings. Clinically, the identified miRNAs and their targets

(e.g., MYH9, ATM, SOD2) may serve as biomarkers for predicting

radiotherapy resistance in AML. They may also provide novel

therapeutic targets to overcome such resistance, enabling more

personalized treatment strategies. Although our findings are

currently preclinical, they lay important groundwork for future

translational research aimed at improving AML patient outcomes.

In summary, further studies are warranted to clarify

the role of these miRNA-mRNA networks in therapy-resistant

leukemia. Future investigations employing integrative miRNA-mRNA

analyses, as demonstrated here, may further elucidate the molecular

basis of radiosensitivity in AML.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grants-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (B) (grant no. 21H02861/23K21419, to Satoru

Monzen) and Takeda Science Foundation 2022 (to Satoru Monzen). The

funders played no role in the study design, data collection and

analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the

manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing data generated in the present study

may be found in the GEO under accession number GSE285934 or at the

following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE285934.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HS, YH and SM designed the study, prepared the

manuscript draft and participated in the revision of the

manuscript. HS, MK, MC and SM performed the biological analysis and

collection of the experimental data. SM supervised the study,

critically reviewed the manuscript and provided final approval for

the version to be submitted and published. All authors have read

and approved the final version of the manuscript. HS and SM confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Nemkov T, D'Alessandro A and Reisz JA:

Metabolic underpinnings of leukemia pathology and treatment. Cancer

Rep (Hoboken). 2:e11392019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shallis RM, Wang R, Davidoff A, Ma X and

Zeidan AM: Epidemiology of acute myeloid leukemia: Recent progress

and enduring challenges. Blood Rev. 36:70–87. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang ZY and Chen Z: Acute promyelocytic

leukemia: From highly fatal to highly curable. Blood.

111:2505–2515. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Reske SN, Deisenhofer S, Glatting G,

Zlatopolskiy BD, Morgenroth A, Vogg ATJ, Buck AK and Friesen C:

123I–ITdU-mediated nanoirradiation of DNA efficiently induces cell

kill in HL60 leukemia cells and in doxorubicin-, beta-, or

gamma-radiation-resistan cell lines. J Nucl Med. 48:1000–1007.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Godley LA and Larson RA: Therapy-related

myeloid leukemia. Semin Oncol. 35:418–429. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bhatia S: Therapy-related myelodysplasia

and acute myeloid leukemia. Semin Oncol. 40:666–675. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nemecek ER, Hilger RA, Adams A, Shaw BE,

Kiefer D, Le-Rademacher J, Levine JE, Yanik G, Leung W, Talano JA,

et al: Treosulfan, fludarabine, and low-dose total body irradiation

for children and young adults with acute myeloid leukemia or

myelodysplastic syndrome undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell

transplantation: prospective phase II trial of the pediatric blood

and marrow transplant consortium. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant.

24:1651–1656. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Monzen S, Takimura K, Kashiwakura I and

Hosokawa Y: Acute promyelocytic leukemia mutated to radioresistance

suppressed monocyte lineage differentiation by phorbol 12-myristate

13-acetate. Leuk Res. 37:1162–1169. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hazawa M, Hosokawa Y, Monzen S, Yoshino H

and Kashiwakura I: Regulation of DNA damage response and cell cycle

in radiation-resistant HL60 myeloid leukemia cells. Oncol Rep.

28:55–61. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Monzen S, Chiba M, Ueno T, Morino Y,

Terada K, Yamaya H and Hosokawa Y: A radioresistant fraction of

acute promyelocytic leukemia cells exhibit CD38 cell-surface

antigen and mRNA expression. Oncol Lett. 15:6709–6714.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Monzen S, Chiba M and Hosokawa Y: Genetic

network profiles associated with established resistance to ionizing

radiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells and their

extracellular vesicles. Oncol Rep. 35:749–756. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Morino Y, Sugiyama H, Yamane K, Kikuchi M,

Yamanaka T, Honda K and Monzen S: Additive antitumor effect of

arsenic trioxide with exposure to ionizing radiation to human acute

promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Oncol Rep. 52:1092024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

He B, Zhao Z, Cai Q, Zhang Y, Zhang P, Shi

S, Xie H, Peng X, Yin W, Tao Y and Wang X: miRNA-based biomarkers,

therapies, and resistance in cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 16:2628–2647.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sun Z, Shi K, Yang S, Liu J, Zhou Q, Wang

G, Song J, Li Z, Zhang Z and Yuan W: Effect of exosomal miRNA on

cancer biology and clinical applications. Mol Cancer. 17:1472018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Peng Y and Croce CM: The role of MicroRNAs

in human cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 1:150042016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Partida-Sánchez S, Cockayne DA, Monard S,

Jacobson EL, Oppenheimer N, Garvy B, Kusser K, Goodrich S, Howard

M, Harmsen A, et al: Cyclic ADP-ribose production by CD38 regulates

intracellular calcium release, extracellular calcium influx and

chemotaxis in neutrophils and is required for bacterial clearance

in vivo. Nat Med. 7:1209–1216. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mouly E, Planquette C, Rousseau E and

Delansorne R: Inecalcitol enhances daratumumab-induced

antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity towards multiple myeloma and

acute myeloid leukemia cell lines. Blood. 132 (Suppl 1):S14472018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Zhong X and Ma H: Targeting CD38 for acute

leukemia. Front Oncol. 12:10077832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Breitman TR, Chen ZX and Takahashi N:

Potential applications of cytodifferentiation therapy in

hematologic malignancies. Semin Hematol. 31 (4 Suppl 5):S18–S25.

1994.

|

|

21

|

Johansson P, Fasth A, Ek T and Hammarsten

O: Validation of a flow cytometry-based detection of γ-H2AX, to

measure DNA damage for clinical applications. Cytometry B Clin

Cytom. 92:534–540. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yuan W, Sun Q, Jiang Y, Zhang X, Chen L,

Xie C, Qin F, Chen Y, Lv H, Chen W and Xiao Y: MiR-146a affects the

alteration in myeloid differentiation induced by hydroquinone in

human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and HL-60

cells. Toxicol Res (Camb). 5:848–858. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Vergani E, Dugo M, Cossa M, Frigerio S, Di

Guardo L, Gallino G, Mattavelli I, Vergani B, Lalli L, Tamborini E,

et al: miR-146a-5p impairs melanoma resistance to kinase inhibitors

by targeting COX2 and regulating NFkB-mediated inflammatory

mediators. Cell Commun Signal. 18:1562020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tse AKW, Wan CK, Shen XL, Zhu GY, Cheung

HY, Yang M and Fong WF: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces biphasic

NF-kappaB responses during HL-60 leukemia cells differentiation

through protein induction and PI3K/Akt-dependent

phosphorylation/degradation of IkappaB. Exp Cell Res.

313:1722–1734. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang X, Zhang G, Huang H, Li H, Lin S and

Wang Y: Differentially expressed MicroRNAs in radioresistant and

radiosensitive atypical meningioma: A clinical study in chinese

patients. Front Oncol. 10:5012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen W, Yao G and Zhou K:

miR-103a-2-5p/miR-30c-1-3p inhibits the progression of prostate

cancer resistance to androgen ablation therapy via targeting

androgen receptor variant 7. J Cell Biochem. 120:14055–14064. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lin JC, Kuo CY, Tsai JT and Liu WH:

miR-671-5p inhibition by MSI1 promotes glioblastoma tumorigenesis

via radioresistance, tumor motility and cancer stem-like cell

properties. Biomedicines. 10:212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Qiu X and Qin F: Retraction: FAM64A

antagonizes tumor suppressive effects of miR-610 in neuroblastoma

in vitro. J Neurosurg Sci. Apr 16–2021.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liu Y, Hu L, Liu O, Ye J and Zhang J:

miR-3651 participates in the growth cycle of hepatocellular

carcinoma cells and promotes the malignant metastasis via the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway. J Oncol. 2022:57449992022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li C, Ding D, Gao Y and Li Y:

MicroRNA-3651 promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation through

directly repressing T-box transcription factor 1. Int J Mol Med.

45:956–966. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Noh JK, Woo SR, Yun M, Lee MK, Kong M, Min

S, Kim SI, Lee YC, Eun YG and Ko SG: SOD2- and NRF2-associated gene

signature to predict radioresistance in head and neck cancer.

Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 18:675–684. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

You GR, Chang JT, Li YL, Huang CW, Tsai

YL, Fan KH, Kang CJ, Huang SF, Chang PH and Cheng AJ: MYH9

facilitates cell invasion and radioresistance in head and neck

cancer via modulation of cellular ROS levels by activating the

MAPK-Nrf2-GCLC pathway. Cells. 11:28552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yu M, Wang J, Zhu Z, Hu C, Ma Q, Li X, Yin

X, Huang J, Zhang T, Ma Z, et al: Prognostic impact of MYH9

expression on patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget.

8:156–163. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Metzeler KH, Hummel M, Bloomfield CD,

Spiekermann K, Braess J, Sauerland MC, Heinecke A, Radmacher M,

Marcucci G, Whitman SP, et al: An 86-probe-set gene-expression

signature predicts survival in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid

leukemia. Blood. 112:4193–4201. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhai Y, Shen H and Wei H: A comprehensive

metabolism-related gene signature predicts the survival of patients

with acute myeloid leukemia. Genes (Basel). 15:632023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gregory MA, D'Alessandro A,

Alvarez-Calderon F, Kim J, Nemkov T, Adane B, Rozhok AI, Kumar A,

Kumar V, Pollyea DA, et al: ATM/G6PD-driven redox metabolism

promotes FLT3 inhibitor resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 113:E6669–E6678. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![Cell proliferation curve and DNA

fragmentation analysis. (A) Cumulative proliferation of Wt-HL60 and

Res-HL60 cells under non-irradiated conditions. Cells were seeded

at 2×105 cells/ml on Day-1 and cultured without

irradiation. On Day 2, the cells were passaged to maintain the same

seeding density. If cell density remained below this threshold,

only the medium was replaced without passaging. The cumulative

number of viable cells was calculated using the formula: Cumulative

cell number (/ml)=A × [(2×105) + B]/(2×105),

where ‘A’ is the viable cell number up to Day 2, and ‘B’ is the net

increase from Day 3 onward relative to the reseeding density. (B)

Cumulative proliferation of Wt-HL60 and Res-HL60 cells under 4-Gy

irradiated conditions. The same seeding and passaging protocol as

in (A) was followed, except that the cells were exposed to 4 Gy of

X-ray irradiation on Day 0. Cell proliferation was then monitored

to assess the impact of irradiation on the growth of wild-type and

resistant HL60 cells. Cumulative viable cell numbers were

calculated using the same formula as in (A). (C) Representative

images of the comet assay showing DNA damage 24 h after X-ray

exposure at doses of 1–4 Gy. (D) Quantification of DNA damage based

on tail moment calculated from the comet assay shown in (C). Data

are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean from four

independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Wt-HL60,

determined by unpaired Student's t-test. Wt, wild type; Res,

resistant.](/article_images/mmr/32/4/mmr-32-04-13645-g01.jpg)