Introduction

Sepsis, resulting from a dysregulated host immune

response to infection and characterized by the excessive release of

inflammatory mediators and abnormal immune cell activation, remains

a major challenge in global healthcare (1). In 2017, ~11.0 million sepsis-related

mortalities were reported worldwide, representing 19.7% of all

global mortalities. Despite a 52.8% decline in the age-standardized

sepsis mortality from 1990 to 2017, sepsis remains a leading cause

of death, prompting researchers to explore new treatment strategies

(2).

The attachment of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) via

an oxygen linkage (O-GlcNAcylation) is a post-translational

modification (PTM) of the serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) residues

in proteins. This PTM can regulate the activation, proliferation

and apoptosis of immune cells, as well as the production of

inflammatory mediators, by influencing various metabolic pathways

and cellular processes (3,4). The regulatory role of O-GlcNAcylation

is particularly important in the context of sepsis (5), as it not only regulates the immune

response to infection but also controls autophagy, the main

mechanism by which cells clear pathogens and damaged organelles.

Therefore, O-GlcNAcylation may play a critical role in the

development of sepsis by affecting immune cell function and the

efficiency of autophagy. The present review aims to investigate the

underlying mechanisms of O-GlcNAcylation as a bridge between

infection immunity and autophagy in sepsis, and to assess its

potential as a therapeutic target.

Infection immunity in sepsis

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition characterized

by organ dysfunction resulting from dysregulation of the host

response to infection (6), and

affected ~48.9 million individuals worldwide in 2017, posing a

great threat to health (2). The

pathogens responsible for sepsis include bacteria, fungi, viruses

and parasites.

Immune cells play a key role in the pathogenesis of

sepsis. Immunological studies have shown that the host immune

response in sepsis involves several sequential or concurrent

processes that lead to excessive inflammation and immune

suppression. This immune dysfunction results in impaired innate and

adaptive immune responses (7).

During the initial phase of sepsis, the body mounts

a robust inflammatory response to infection. Immune cells such as

macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes are

activated following the recognition of pathogen-associated and

damage-associated molecular patterns, which triggers the

inflammatory response (8). As

sepsis progresses, patients often develop immunosuppression,

characterized by diminished immune cell function, particularly

decreased activity of T cells and B cells, and increased activity

of regulatory T (Treg) cells. This immunosuppressive state

increases susceptibility to secondary infections and may lead to

clinical deterioration and even death (Fig. 1) (8,9).

In sepsis, autophagy plays a vital role in

cytoplasmic quality control, cellular metabolism, and innate and

adaptive immune responses. It involves a variety of immune cells,

including neutrophils, macrophages, T cells and B cells (10,11).

In neutrophils, autophagy facilitates the clearance of pathogenic

microorganisms, supports cellular function and prevents cell death.

Studies have shown that the autophagic activity of neutrophils

increases during sepsis, which may help to maintain their survival

and function. However, the hyperactivation or inhibition of

autophagy can impair the function of neutrophils, thereby affecting

the progression of sepsis (12,13).

In macrophages, autophagy not only facilitates the clearance of

pathogens but also regulates the inflammatory response. During

sepsis, the autophagic activity of macrophages may be suppressed,

leading to the excessive release of inflammatory mediators and

amplification of the inflammatory response. Conversely, the

activation of autophagy can attenuate macrophage-mediated

inflammation, offering protection against sepsis (14). Autophagy is also essential for the

survival and function of T cells. In sepsis, the autophagic

activity of T cells is weakened, which results in increased T-cell

apoptosis and immunosuppression. In a murine model of sepsis, mice

deficient in a T-cell-specific autophagy gene known as autophagy

related 7 exhibited a higher mortality rate and greater

immunosuppression than was observed in wild-type mice, suggesting a

protective role for T-cell autophagy in the regulation of T-cell

apoptosis and immunosuppression (10,15).

The role of B cells in sepsis has not been fully elucidated;

however, autophagy has been indicated to affect the immune response

in sepsis by regulating B cell maturation and antibody production,

with the activation of autophagy being suggested to contribute to

the maintenance of B cell function and prevent immunosuppression

(10). In summary, the effect of

autophagy on immune cells in sepsis is multifaceted, involving

various immune cells, such as neutrophils, macrophages, T cells and

B cells. Activation or inhibition of autophagy may have an

important effect on the pathogenesis of sepsis, and the regulation

of autophagy may be a novel therapeutic strategy for sepsis.

Basic biological functions of protein

O-GlcNAc modification

O-GlcNAcylation is a crucial PTM in which GlcNAc

molecules attach to Ser or Thr residues in proteins. O-GlcNAc

modifications differ from other types of glycosylation in several

important aspects (3,16–18):

i) They involve the addition of a monosaccharide, unlike other

types where complex sugar chains are involved; ii) they primarily

occur in the cytoplasm and nucleus, rather than via the Golgi or

endoplasmic reticulum pathways; iii) the modification process is

dynamic, reversible and regulated by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and

O-GlcNAcase (OGA); iv) they interact with other PTMs, such as

phosphorylation, methylation and ubiquitination, to regulate

protein activity and function; and v) they play a role in the

regulation of key cellular biological functions. Due to these

characteristics, O-GlcNAcylation makes a multifaceted contribution

to cell biology and disease development.

Impact of the interaction between

O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation in terms of sepsis

O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation are two key

protein PTMs that regulate a variety of physiological and

pathological processes through dynamic competition or synergy.

O-GlcNAcylation involves the addition of a single GlcNAc group to

Ser or Thr residues, whereas phosphorylation involves the addition

of phosphate groups, often at the same or adjacent sites, resulting

in a competitive or cooperative regulatory relationship between the

two mechanisms (19). For example,

in metabolic regulation, O-GlcNAcylation inhibits the Ser9

phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β, thereby reducing

the hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein, which may protect against

neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (20,21).

Similarly, the Ser40 phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)

promotes dopamine synthesis, whereas O-GlcNAcylation reduces TH

activity by inhibiting phosphorylation at this site, thereby

affecting L-DOPA levels (22). In

addition, O-GlcNAcylation can increase the activity of glycogen

phosphorylase, suggesting that synergistic effects may exist

between these two PTMs in certain contexts (23).

In the pathological process of sepsis, the balance

between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation markedly influences the

regulation of inflammatory responses and cell death. Recent studies

have shown that O-GlcNAcylation can inhibit phosphorylation-driven

pro-inflammatory signaling by targeting key inflammation-related

proteins. For example, the O-GlcNAcylation of gasdermin D (GSDMD)

inhibits its phosphorylation-dependent activation, thereby

attenuating lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced pyroptosis, a

mechanism that may protect against vascular endothelial injury in

sepsis (24). Similarly,

homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2) inhibits

hyperinflammation by promoting the acetylation of NF-κB via the

phosphorylation of histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3), while

O-GlcNAcylation may affect this pathway indirectly by regulating

the activity or stability of HIPK2 (25). The NF-κB acetylation promoted by

the HIPK2-mediated phosphorylation of HDAC3 has been shown to

ameliorate colitis-associated colorectal cancer and sepsis in mice.

In another study, Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) was shown to activate

ERK1/2 phosphorylation, leading to the downregulation of

Kruppel-like factor 4, thereby exacerbating the inflammatory

response in sepsis (26).

In sepsis, phosphorylation is often associated with

the amplification of pro-inflammatory and cell death signals. For

example, peptidylprolyl cis/trans isomerase, NIMA-interacting 1

exacerbates the inflammatory response in septic shock by promoting

the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, which increases the activation of

the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome.

O-GlcNAcylation can counteract this effect by competitively

modifying the same or adjacent sites of p38 MAPK, thereby

preventing its phosphorylation and blocking downstream inflammatory

signaling (27,28). Notably, O-GlcNAcylation and

phosphorylation may act synergistically in certain contexts. For

example, O-GlcNAc modification has been shown to increase

glycogenolysis by promoting the phosphorylation of glycogen

phosphorylase L during energy stress (23). In summary, the dynamic interplay

between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation in sepsis reflects a

precisely regulated balance that controls inflammatory intensity,

cell death patterns and metabolic adaptation. Targeting this

interaction may offer novel strategies for the treatment of

sepsis.

Impact of the interaction between

O-GlcNAcylation and ubiquitination in terms of sepsis

There is a complex, cross-regulatory relationship

between O-GlcNAcylation and ubiquitination, both of which are

involved in cellular stress responses, metabolic regulation and

disease progression. O-GlcNAc modification affects the stability,

activity and interactions of proteins by the dynamic addition or

removal of GlcNAc groups, thereby influencing the ubiquitination

process (29). For example,

O-GlcNAcylation can increase the stability of key proteins by

inhibiting their ubiquitination; the O-GlcNAcylation of the

circadian regulators brain and muscle ARNT-like 1 and circadian

locomotor output cycles kaput prevents their ubiquitin-mediated

degradation, thereby maintaining the normal functioning of the

biological clock (30). In

addition, the synergistic or antagonistic effects of

O-GlcNAcylation and ubiquitination play critical roles in processes

such as DNA damage repair and cancer metabolism (31,32).

The activity of certain E3 ubiquitin ligases, such as members of

the cullin-RING ligase (CRL) family, can be regulated by O-GlcNAc

modifications, thereby affecting the ubiquitination levels of their

substrate proteins (33). The

ubiquitin-proteosome system itself is highly complex, with various

ubiquitin chain types, including lysine (Lys)48- and Lys63-linked

chains, and dynamic modification patterns. These features form a

multi-level interaction network with O-GlcNAcylation to coordinate

cellular responses to stresses such as oxidative stress and

nutrient deprivation (29,34).

The cross-regulation between O-GlcNAcylation and

ubiquitination plays a key role in modulating the intensity of the

inflammatory response and maintaining cellular homeostasis. Studies

have shown that O-GlcNAc modification can dynamically modulate

pro-inflammatory signaling pathways by targeting key components of

the ubiquitination system. For example, in macrophages,

O-GlcNAc-modified NOD-like receptor X1 (NLRX1) downregulates IL-1β

expression by interacting with inhibitor of κB kinase α (IKK-α) and

inhibiting its ubiquitination-dependent activation, thereby

potentially limiting tissue damage due to excessive inflammatory

responses in sepsis (35). In

addition, the E3 ubiquitin ligase tripartite motif containing 27

(TRIM27) exacerbates sepsis-related oxidative stress and

endothelial dysfunction by promoting the ubiquitin-mediated

degradation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

(PPARγ), and O-GlcNAc modification may counteract the

pro-inflammatory effects of TRIM27 by stabilizing PPARγ protein

levels (30,36). Notably, the diversity of

ubiquitination systems, including different chain linkages such as

Lys48- and Lys63-linked chain types, contributes to the dual

regulatory features observed in sepsis: Lys48-linked ubiquitination

typically targets proteins for proteosomal degradation, helping to

clear damaged proteins, whereas Lys63-linked ubiquitination

amplifies inflammation by activating pathways such as the NF-κB

pathway (29,37). O-GlcNAc modification may balance

the inflammatory phenotype of macrophages by selectively regulating

the activity of specific E3 ligases, such as E3 ubiquitin-protein

ligase COP1, and affecting the ubiquitination status of

transcription factors such as CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β

(38).

Ubiquitination often serves as a central node for

pro-inflammatory and cell death signaling in sepsis, while O-GlcNAc

modification may exert a protective effect through multi-level

regulatory mechanisms. For example, microbial infection-induced

endothelial cell dysfunction is associated with the aberrant

ubiquitination of a variety of proteins, such as NADPH oxidase 4

(NOX4), whose stability is regulated by ubiquitination, and its

overexpression exacerbates oxidative stress (36,37).

O-GlcNAc modification may reduce the production of reactive oxygen

species (ROS) by directly modifying NOX4 or regulating the activity

of its E3 ligases, such as TRIM27, analogous to its modulatory role

in the CRL family ubiquitin ligases involved in DNA damage repair

(33). Small-molecule drugs

targeting the ubiquitination system, such as deubiquitinase

inhibitors, have been shown to modulate the inflammatory cascade in

sepsis (39). Similarly, the

development of OGT inhibitors or activators may provide new

therapeutic strategies by modulating the O-GlcNAc-ubiquitination

axis. Notably, there may be synergistic effects between these

pathways: For example, O-GlcNAcylation may enhance the stability of

NLRX1, promoting its binding to IKK-α and thereby indirectly

inhibiting the ubiquitin-dependent activation of the IKK complex;

this regulatory homeostasis may exhibit distinct regulatory

characteristics at different stages of sepsis (35). In conclusion, the interplay between

O-GlcNAcylation and ubiquitination constitutes a complex regulatory

network in sepsis. Further elucidation of the underlying mechanism

may lay a foundation for the development of targeted interventions

to prevent inflammatory imbalance and organ injury.

Impact of the interaction between

O-GlcNAcylation and methylation in terms of sepsis

There is extensive cross-regulation between O-GlcNAc

modification and both DNA and histone methylation, which together

contribute to the maintenance of epigenetic homeostasis and the

regulation of gene expression. Studies have shown that OGT directly

modifies DNA methyltransferase 1 through glucose-dependent

O-GlcNAcylation, thereby inhibiting its activity, reducing the

overall level of genomic methylation and affecting transposon

silencing (40,41). At the histone level, OGT is

recruited to specific chromatin regions by disruptor of telomeric

silencing 1-like, a histone methyltransferase, where it catalyzes

the O-GlcNAcylation of histone H2B, which works synergistically

with histone H3 Lys79 (H3K79) methylation to regulate gene

transcriptional activation (31).

In addition, metabolic signals, such as glucose availability, are

integrated into the epigenetic regulatory network via O-GlcNAc

modification. For example, the c-Myc oncoprotein modulates

mitochondrial metabolism and O-GlcNAc cycling, influencing the

activity and subcellular localization of DNA and RNA demethylases,

thereby linking cellular metabolic state to epigenetic

reprogramming (42).

The crosstalk between O-GlcNAcylation and

methylation regulates epigenetic reprogramming and metabolic

adaptation, which affects the inflammatory response and organ

injury. Dysregulation of this epigenetic modification is

particularly prominent in monocytes from patients with sepsis and

is strongly associated with the aberrant expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, as well as organ

dysfunction (43). In addition,

the synergistic interaction of histone methylation with

O-GlcNAcylation has a dual role in sepsis: During the endotoxin

tolerance stage, G9a-mediated H3K9 methylation and DNA methylation

contribute to silencing of the TNF-α gene (44), while O-GlcNAc modification

dynamically regulates the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory

genes by regulating DOT1-like histone Lys

methyltransferase-dependent H3K79 methylation (31). This multilevel

epigenetic-metabolic-ubiquitination regulatory network provides a

new paradigm for targeting immunometabolic imbalances in

sepsis.

In conclusion, O-GlcNAcylation forms a

multi-dimensional regulatory network with other PTMs, including

phosphorylation, ubiquitination and methylation, that supports a

shift in sepsis treatment from a single anti-inflammatory mode to a

systematic regulation based on the dynamic integration of the PTM

network. This integrated perspective could provide enable the

reversal of immunometabolic imbalances in sepsis.

O-GlcNAcylation and autophagy

The PTM of proteins plays a key role in autophagy,

either by directly regulating the expression of autophagy-related

genes or by modulating key components of the autophagy signaling

pathway (45–47). Among these PTMS, O-GlcNAcylation

has been shown to be closely associated with the regulation of

autophagy; it regulates autophagy by modifying key

autophagy-related proteins, thereby affecting their activity,

stability and subcellular localization (18). Several proteins with different

roles in the autophagy pathway have been identified as potential

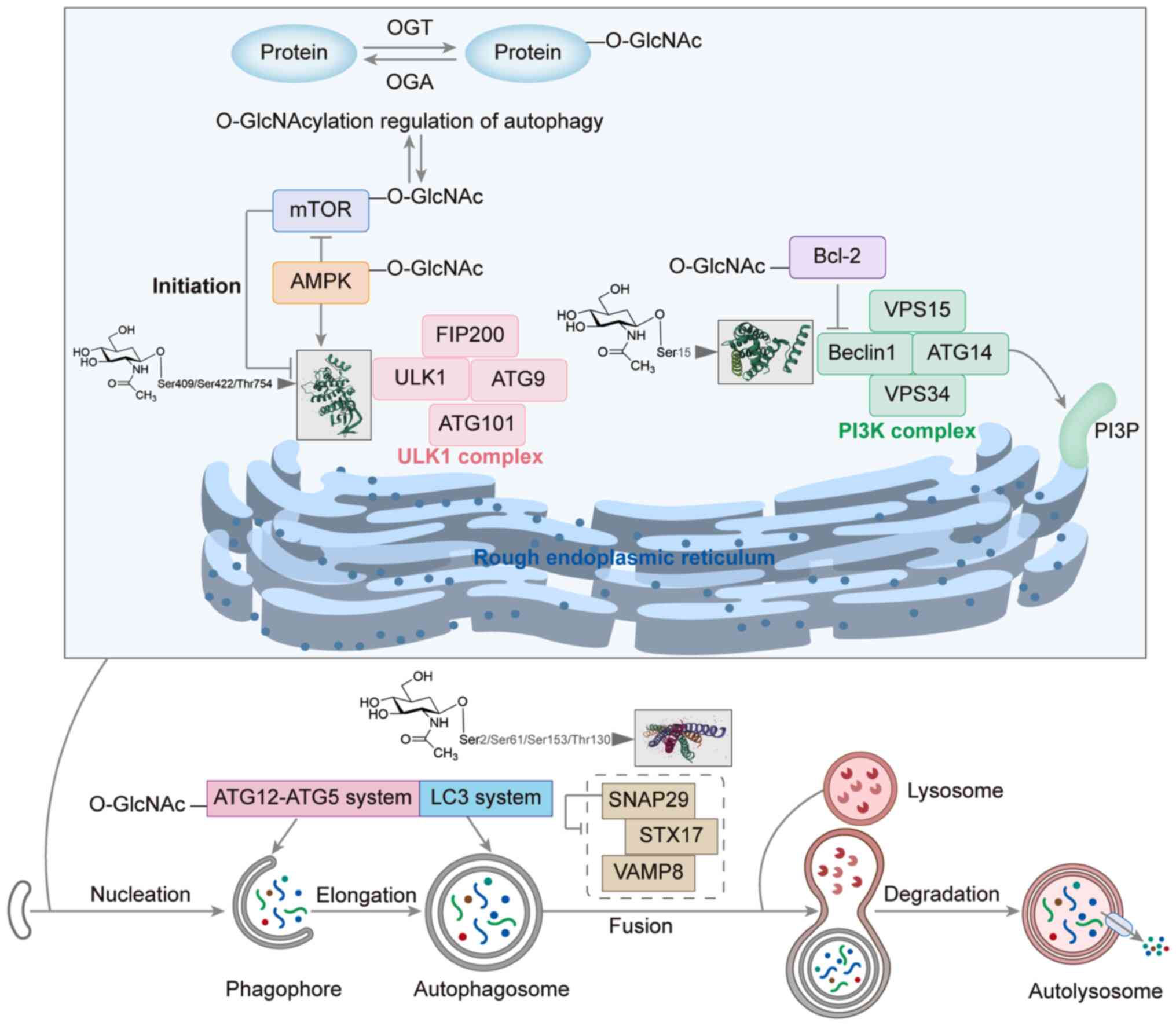

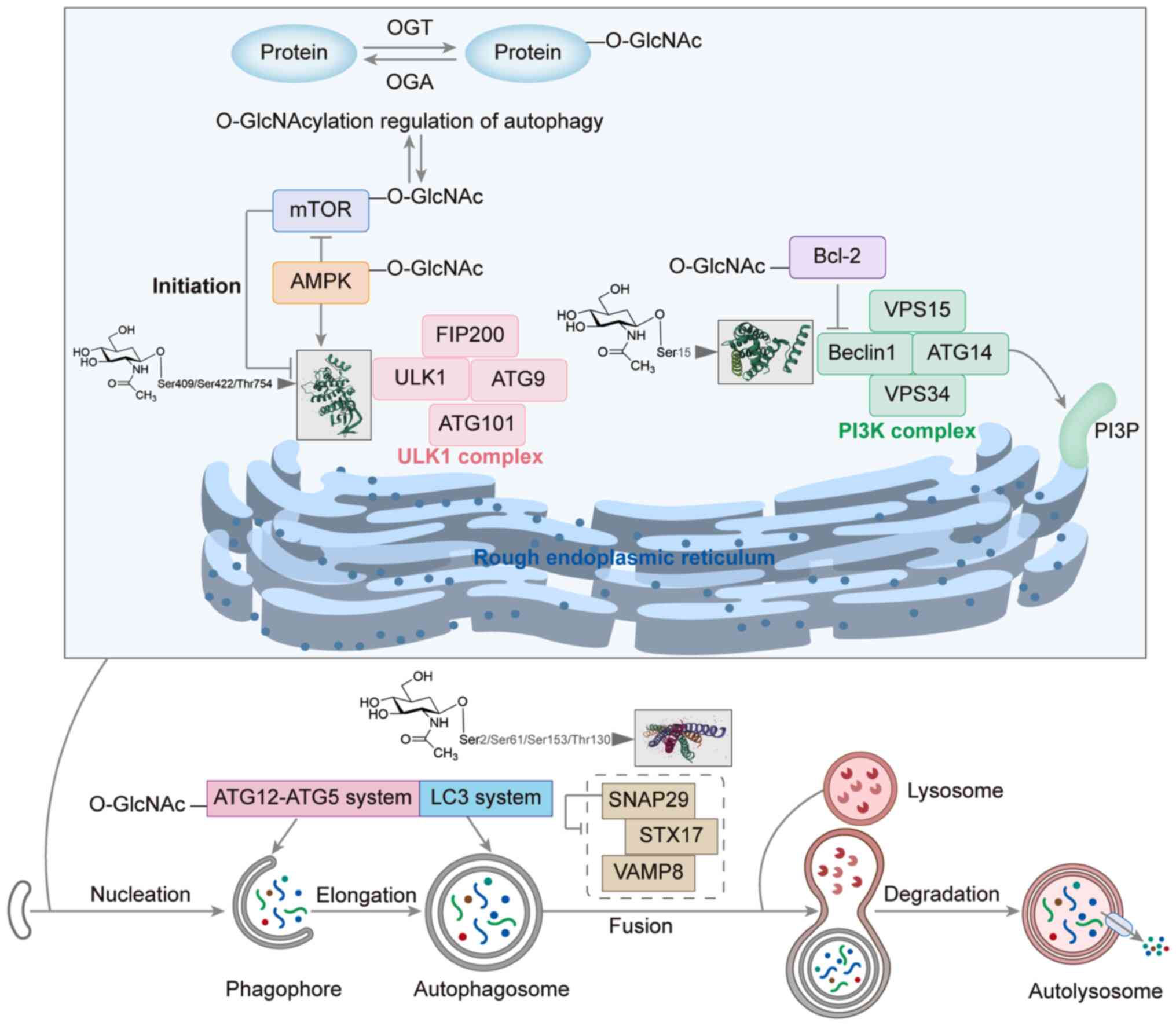

targets of O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 2

and Table I) (28,48–60).

| Figure 2.Role of O-GlcNAcylation in the

initiation, nucleation, elongation and fusion stages of autophagy

and lysosomal activity. AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ATG,

autophagy related; FIP200, FAK family kinase-interacting protein of

200 kDa; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3;

O-GlcnAc, O-linked N-acetylglucosamine; O-GlcNAcylation, attachment

of GlcNAc via an oxygen linkage; OGA, O-GlcNAcase; OGT, O-GlcNAc

transferase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PI3P,

phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate; SNAP29, synaptosome-associated

protein 29; STX17, syntaxin 17; ULK1, unc-51 like autophagy

activating kinase 1; VAMP8, vesicle-associated membrane protein 8;

VSP, voltage-sensing phosphatase. |

| Table I.Summary of O-GlcNAc modification

sites and their effects on protein function in autophagy

regulation. |

Table I.

Summary of O-GlcNAc modification

sites and their effects on protein function in autophagy

regulation.

| Protein | O-GlcNAc

modification sites | O-GlcNAcylation

regulatory mechanism | Autophagy

phase | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Beclin1 | Ser15 | O-GlcNAcylation

enhances beclin1 binding to Bcl-2, blocks its independent activity,

inhibits autophagosome formation, and reduces basal autophagy

levels | Initiation | (48,49) |

| Bcl-2 | Unclear | O-GlcNAcylation

upregulates Bcl-2 expression, enhances binding stability with

beclin1, inhibits autophagy, promotes apoptosis, and balances

cellular stress responses | Initiation | (49,50) |

| AMPK | Unclear | O-GlcNAc

modification inhibits AMPK activity, suppressing ULK1 activation

and autophagy | Initiation | (28) |

| mTOR | Unclear | Inhibiting OGT

enhances autophagy in rat cortical neurons; this effect is further

amplified when treated with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin | Initiation | (51) |

| ULK1 | Thr754, Ser409 and

Ser422 | O-GlcNAcylation at

Thr754 is critical for VPS34 activation via ATG14L, promoting

autophagy; Ser409 modification inhibits phosphorylation at Ser423,

stabilizing ULK1; maresin-2 activates GFAT1, enhances O-GlcNAc

modification and autophagosome formation via TAK1-TAB1 inhibition,

but ULK1 Ser409 and Ser422 mutations counteract this effect | Initiation | (52–54) |

| PINK1 | Unclear | O-GlcNAcylation

inhibits PINK1 stability, blocks PARKIN recruitment during

mitochondrial depolarization, suppresses mitophagy, and leads to

the accumulation of damaged mitochondria | Elongation | (55) |

| SNAP29 | Ser2, Ser61, Thr130

and Ser153 | O-GlcNAcylation

blocks SNARE complex assembly with STX17-VAMP8, thereby interfering

with membrane fusion and inhibiting autophagy | Fusion | (56–60) |

The activation of unc-51 like autophagy activating

kinase 1 (ULK1) by stressors such as nutrient deprivation (for

example, amino acid starvation) and energy stress (for example, ATP

depletion/AMP elevation) triggers the autophagic process. ULK1 and

ULK2 form protein complexes with various mitosome-associated

proteins, including 200 kDa FAK family kinase-interacting protein,

autophagy related (ATG)13 and ATG101, which jointly regulate the

initiation phase of autophagy (61). These ULK protein complexes play a

key regulatory role in the formation of autophagic vesicles and are

responsive to signals from multiple signaling pathways. The

activity of the ULK1 complex is regulated by both mTOR complex 1

and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (62,63).

Specifically, activation of mTOR via Akt and MAPK signaling

inhibits autophagy, while the inhibition of mTOR by AMPK or p53

signaling promotes autophagy. The ULK complex promotes the

localized synthesis of phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate by

phosphorylating components of the class III phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase complex, which includes beclin1, vacuolar protein sorting

(VPS)15, VPS34 and ATG14 (64).

Beclin1 has been identified as a direct target of O-GlcNAcylation,

and the O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of beclin1 at the Ser15

site has been shown to regulate autophagy in HTR-8/SVneo cells

(48). Bcl-2 inhibits autophagy by

interacting with beclin1, and Bcl-2 is also a target of

O-GlcNAcylation (49). The

O-GlcNAcylation of beclin1 enhances its binding to Bcl-2, thereby

suppressing autophagic activity, whereas the O-GlcNAcylation of

Bcl-2 regulates autophagy and apoptosis by influencing its

expression levels (50,65).

The elongation of phagophores is promoted by two

ubiquitin-like conjugation systems: The ATG12-ATG5 system and the

microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) system

(66). Wang and Hanover (67) demonstrated that the deletion of OGT

in Drosophila resulted in a reduction in O-GlcNAc levels and

a significant increase in the accumulation of GFP-LGG-1 (an

ATG8/LC3 homolog) and its phosphatidylethanolamine-modified form

under starvation conditions, indicating enhanced autophagosome

formation. Furthermore, OGT knockdown upregulated the mRNA

expression of ATG1 and ATG5, whereas OGT overexpression inhibited

the transcription of ATG5 and ATG8 (68). These findings suggest that

O-GlcNAcylation limits autophagic activity by suppressing the

expression of ATG genes. This mechanism may operate synergistically

with the stabilization of the beclin1/Bcl-2 complex by

O-GlcNAcylation in mammals to maintain the basal autophagy in a

low-activity state under normal conditions.

During autophagic fusion, intact autophagosomes fuse

with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, which enables the degradation

of substances via the action of lysosomal enzymes. O-GlcNAcylation

has been shown to regulate the autophagosome-lysosome fusion phase

of autophagy in an arsenic-exposed environment by targeting

synaptosome-associated protein 29 (SNAP29) (29). In SNAP29-mediated vesicle fusion,

autophagosome membranes containing syntaxin 17 (STX17) are linked

to lysosomes containing vesicle-associated membrane protein 8

(VAMP8) (69). The O-GlcNAcylation

of SNAP29 blocks the assembly of the SNARE complex from STX17,

SNAP29 and VAMP8, thereby impairing normal autophagy (70).

Infection and immune regulation by O-GlcNAc

modification

O-GlcNAc modification affects cellular metabolism,

autotransduction, translation and signal transduction as a nutrient

and stress sensor. The maintenance of proper O-GlcNAcylation is

crucial for health, as imbalances in O-GlcNAcylation can result in

pathological conditions such as tumors, diabetes and

neurodegenerative diseases (71–73).

A number of studies have focused on the role of O-GlcNAcylation in

the regulation of the immune response and maintenance of

homeostasis during infection. The present review offers insights

into the role of O-GlcNAcylation in the modulation of immune

responses against viral, bacterial, fungal and parasitic

infections, and explores its potential as a therapeutic target in

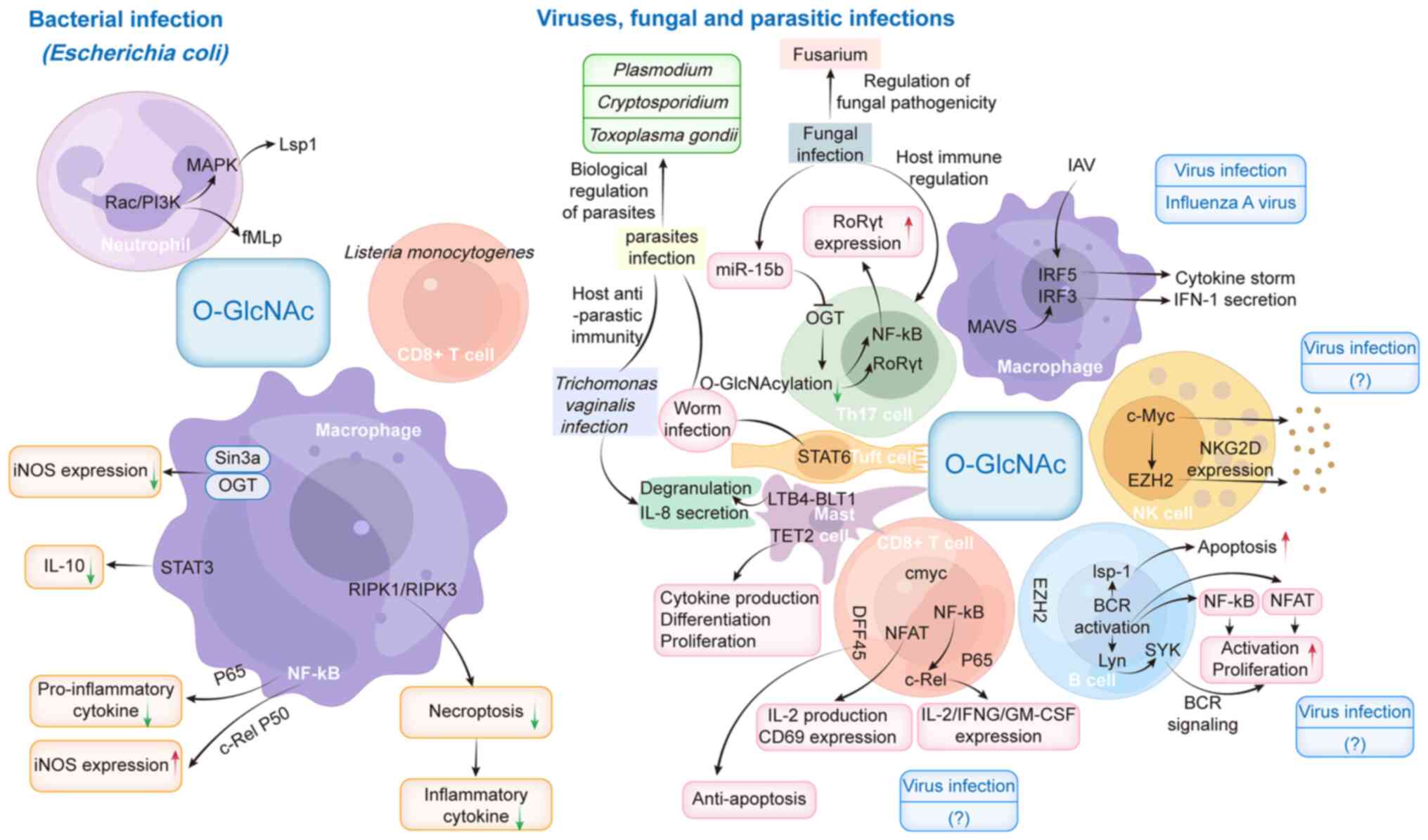

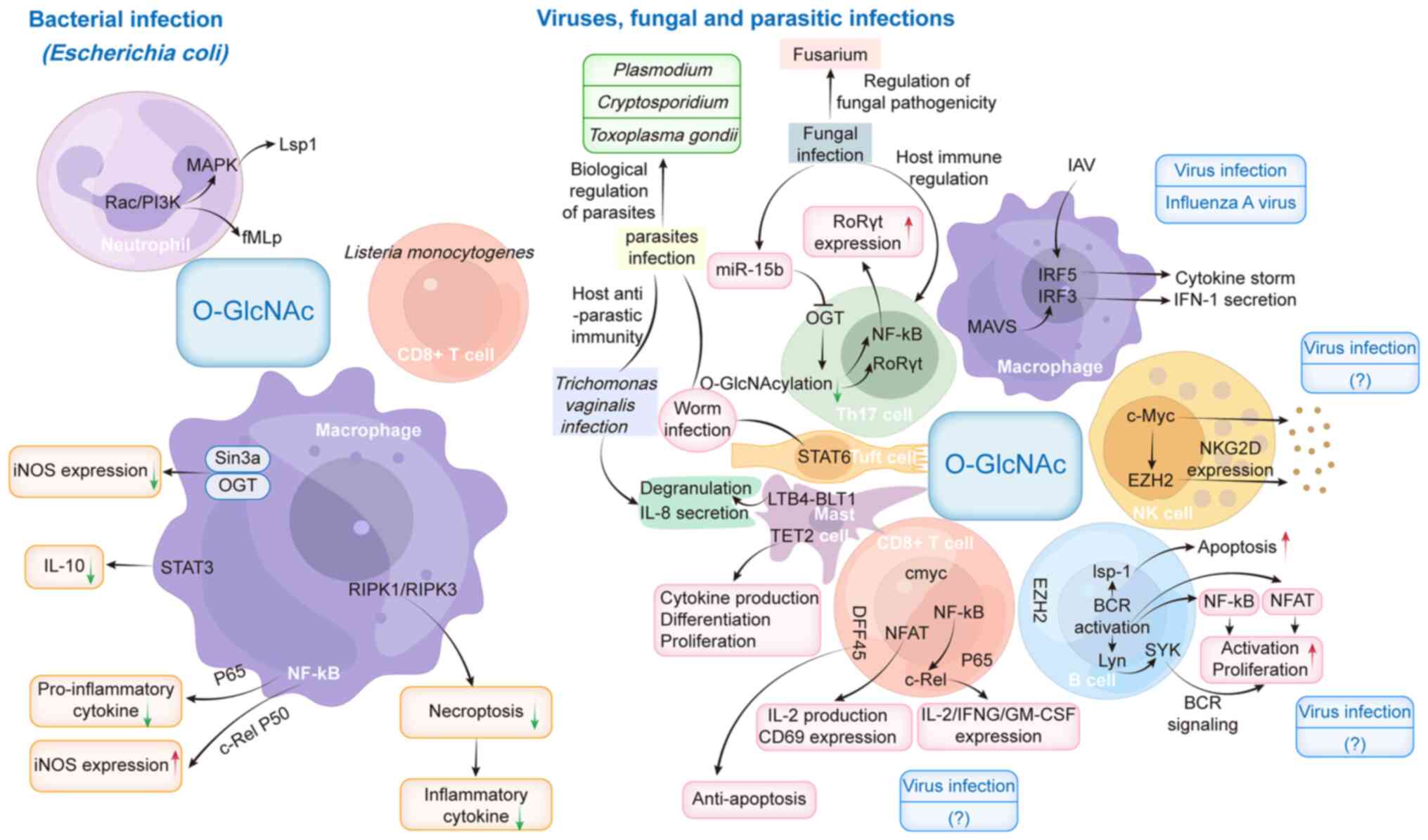

sepsis (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3.Role of O-GlcNAcylation in the immune

response to infection with different pathogens. BCR, B-cell

receptor; BLT1, LTB4 receptor 1; c-Rel, cellular-Rel; DFF45, DNA

fragmentation factor 45; EZH2, enhancer of zeste 2; fMLP,

N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine; GM-CSF, granulocyte

macrophage-colony-stimulating factor; IAV, influenza A virus; IFN,

interferon; IFNG, IFN-g; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase;

IRF, IFN regulatory factor 3; Lsp1, lymphocyte-specific protein 1;

LTB4, leukotriene B4; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral signaling

protein; miR-15b, microRNA-15b; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated

T-cells; NK, natural killer; NKG2D, NK group 2D; O-GlcNAc, O-linked

N-acetylglucosamine; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase; PI3K,

phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RIPK, receptor-interacting protein

kinase; RoRyt, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor gt;

TET2, Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2; Th17, T helper 17. |

Function of O-GlcNAcylation in immune

cell recognition of bacterial infections

Neutrophils are key cells of the innate immune

system that rapidly migrate to sites of bacterial infection and

remove pathogens via phagocytosis, the release of ROS and necrosis.

Neutrophils are the initial responders to injury and infection, and

the prognosis of sepsis is poor when neutrophil migration is

impaired (74). In both animal

models and patients with advanced sepsis, neutrophil function is

notably compromised, as evidenced by diminished bacterial

clearance, reduced reactivity, decreased ROS production and a

significant reduction in neutrophil numbers within infected tissues

(75).

O-GlcNAcylation has been found to significantly

influence neutrophil chemotaxis and cell migration. For example,

treatment with the chemoattractant

N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine significantly elevates

O-GlcNAcylation levels, thereby promoting neutrophil chemotaxis and

migration (76). In addition,

glucosamine (GlcN) promotes O-GlcNAcylation by increasing the

availability of UDP-GlcNAc, which is the donor substrate for OGT;

GlcN enters the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) downstream of

the rate-limiting enzyme glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate

transaminase 1, effectively bypassing it and boosting UDP-GlcNAc

production (77). Mechanistically,

enhanced O-GlcNAcylation promotes Rac- and phosphoinositide

3-kinase-dependent chemotaxis. Rac is an key small GTPase that

regulates neutrophil mobilization by activating downstream MAPK

signaling and promoting the phosphorylation of lymphocyte specific

protein 1 at Ser243 (78–80). These signaling pathways are

critical for neutrophil migration and effector functions.

O-GlcNAcylation is inducible in neutrophils and modulates their

dynamic responses, potentially providing a novel therapeutic target

for the treatment of sepsis.

Macrophages play a key role in resistance to

bacterial infections by eliminating pathogens through various

mechanisms, including the activation of inducible nitric oxide

synthase (iNOS) to produce nitric oxide (NO). NO is a gaseous

signaling molecule with antibacterial properties, capable of

inhibiting bacterial metabolic enzymes, thereby impairing bacterial

viability. In response to bacterial infection or inflammatory

stimuli, macrophages increase iNOS expression, thereby increasing

NO production (81). NF-κB is a

key regulator of the inflammatory response in macrophages and can

be modified via O-GlcNAcylation. In RAW264.7 macrophage-like cells,

the interaction of OGT with murine Sin3A disrupts NF-κB activation

and downregulates iNOS gene expression upon LPS stimulation

(82). In microglia,

O-GlcNAcylation of the NF-κB subunit cellular-Rel (c-Rel) promotes

the formation of the c-Rel-p50 heterodimer and increases iNOS

production (83). Notably, the

response of the NF-κB subunit p65 to O-GlcNAcylation differs

markedly from that of c-Rel. Thiamet-G, a potent and selective

inhibitor of OGA, exerts anti-inflammatory effects by promoting the

O-GlcNAcylation of p65 in microglia, which subsequently modulates

its nuclear localization and reduces the expression of inflammatory

genes (84).

Inflammatory diseases such as sepsis are

characterized by elevated glucose metabolism in immune cells.

Despite macrophages exhibiting increased glycolytic activity and

pentose phosphate pathway activation during inflammation, endotoxin

exposure inhibits HBP activity, resulting in decreased protein

O-GlcNAcylation. Loss of OGT promotes the innate immune response

and exacerbates inflammation in sepsis. Specifically, OGT-mediated

O-GlcNAcylation of receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK)3 at

Thr467 disrupts its interaction with RIPK1 and RIPK3 proteins,

thereby inhibiting downstream innate immune responses, necroptosis

and antibacterial activity (85).

CD8+ T cells are essential for

cell-mediated immunity. Upon acute infection, naive CD8+

T cells differentiate into effector cells following antigen

stimulation. These effector cells eliminate bacteria by releasing

granules containing perforins and granzymes, and secreting

cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ and TNF-α (86,87).

This immune response involves the phosphorylation of various

intracellular signaling proteins. Protein O-GlcNAcylation often

acts synergistically with phosphorylation (16). Lopez Aguilar et al (88) demonstrated that O-GlcNAcylation was

dynamically elevated in murine CD8+ T cells during

Listeria infection and in vitro differentiation, with

activated effector cells exhibiting increased global levels in

vivo, and memory-like cells exhibiting even higher levels

(including distinct high-molecular weight modifications) in

vitro. Proteomics revealed that O-GlcNAc in effector-like cells

primarily targets transcription/translation machinery (such as

ribosomal proteins) to enable rapid proliferation, while in

memory-like cells it modifies transcriptional regulators, mRNA

processing factors and tRNA synthetases, suggesting roles in

establishing a poised state. Notably, O-GlcNAc contributes to the

‘histone code’ in both subsets, implicating it in epigenetic

regulation of T cell function.

O-GlcNAcylation plays a key regulatory role in the

immune response triggered by bacterial infection by dynamically

modifying inflammation-related proteins. Pathogen-associated

molecular patterns, such as bacterial LPS, can increase

O-GlcNAcylation levels in endothelial cells, thereby exacerbating

inflammation via the activation of inflammatory signaling

pathways (89). At the

molecular level, the OGT-mediated glycosylation of NLRX1

facilitates its interaction with IKK-α and promotes the expression

of IL-1β in M1 macrophages (35). In parallel, O-GlcNAcylation of the

NLRP3 inflammasome not only directly regulates pyroptosis but also

promotes the release of inflammatory cytokines by enhancing the

activity of the NIMA related kinase 7/NLRP3 axis (90,91).

Furthermore, this PTM can create a positive feedback loop, whereby

the O-GlcNAcylation of STAT3 further amplifies pro-inflammatory

signaling by enhancing JAK2/STAT3 pathway signaling

activity (92,93). As an upstream regulator, the phase

separation process of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 may also

contribute to this regulatory network. Notably, inhibition of

O-GlcNAcylation has been shown to effectively block STAT3- and

forkhead box protein O1-mediated oxidative stress-induced

apoptosis (93–95), suggesting that targeting this

modification may be a promising strategy for the alleviation of

hyperinflammation during bacterial infections.

These findings suggest that targeting O-GlcNAc

modifications may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for the

treatment of sepsis by optimizing immune cell function and reducing

the tissue damage caused by excessive inflammation.

Influence of O-GlcNAcylation on immune

cell detection of fungal infections

O-GlcNAcylation has been implicated in the

differentiation of T helper (Th)17 cells during fungal infections.

Naive CD4+ T cells can differentiate into Th1, Th2, Th17

and Treg cells (96). The

downregulation of OGT through microRNA-15b has been shown to

inhibit Th17 cell differentiation, thereby contributing to the

pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (97). In addition, elevated O-GlcNAc

levels have been shown to promote the secretion of IL-17A by Th17

cells and upregulate the production of lipid ligands for the

transcription factor RAR-related orphan receptor γt in diet-induced

obese mice (98). Furthermore, in

Treg cells, O-GlcNAc-mediated post-translational modifications of

the T-cell receptor (TCR) have been demonstrated to increase the

stability of forkhead box P3 and activate STAT5, effects that act

synergistically to control Treg cell homeostasis and function

(96).

Notably, fungal O-GlcNAc metabolism itself directly

affects pathogenicity. As a key signaling molecule, GlcNAc

regulates morphological transitions, the expression of virulence

factors and environmental adaptation in a variety of fungi such as

Fusarium. For example, deletion of the OGT homologous gene

FpOGT in Fusarium proliferatum inhibits the expression of

glucose metabolism-related genes, such as glucokinase, resulting in

restricted fungal growth, a downregulated stress response and

markedly reduced virulence (99).

In addition, GlcNAc has been demonstrated to be a key metabolic

target for fungal pathogenesis since it regulates cell wall

synthesis, biofilm formation and host tissue invasion pathways

(100,101). From a therapeutic perspective,

interventions targeting GlcNAc sensing and metabolism, such as

GlcNAc analogs or metabolic engineering, have been shown to

effectively reduce the virulence of pathogenic fungi (102).

Therefore, in sepsis complicated by fungal

infection, the combined modulation of host O-GlcNAc levels to

enhance Th17-mediated antifungal immunity while inhibiting fungal

GlcNAc-dependent virulence pathways may offer a synergistic

therapeutic strategy. Future studies are necessary to further

elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the host-fungus O-GlcNAc

interaction network and to develop dual regulatory strategies to

optimize immunometabolic balance.

Role of O-GlcNAcylation in immune cell

recognition of viral infections

Macrophages play a crucial role in the innate immune

system, particularly for the early detection of and response to

viral infections. Research indicates that O-GlcNAcylation in

macrophages is essential for the recognition of RNA viruses. These

viruses are detected by cytosolic retinoic acid-inducible gene

I-like receptors (RLRs), particularly retinoic acid-inducible gene

I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. Upon viral

recognition, these receptors engage mitochondrial antiviral

signaling protein (MAVS), which activates IFN regulatory factor

(IRF)3 and promotes the production of type I IFN (103). In mouse bone marrow-derived

macrophages, the absence of OGT disrupts MAVS-dependent RLR

signaling and reduces inflammatory cytokine expression (104). Research has further shown that

O-GlcNAcylation is crucial for modulating immune responses and

increasing infection resistance in macrophages. During influenza A

virus infection, O-GlcNAcylation regulates the inflammatory

response by modulating the activity of specific transcription

factors.

Specifically, O-GlcNAcylation at the Ser430 residue

of IRF5 is necessary for its Lys63-linked ubiquitination, which

promotes IRF5 activation by facilitating nuclear translocation and

interaction with the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6. This modification

drives downstream proinflammatory cytokine production during

influenza infection (105). Thus,

both IRF3 and IRF5 undergo O-GlcNAcylation and ubiquitination,

which are crucial for the regulation of macrophage-mediated

inflammatory responses following influenza infection. Balancing

these modifications is essential to ensure the appropriate

intensity of the immune response while preventing excessive

inflammation.

Natural killer (NK) cells are crucial components of

the innate immune system, responsible for targeting and eliminating

virus-infected cells. O-GlcNAcylation has been shown to modulate

the function of NK cells as a PTM; specifically, the elevated

O-GlcNAcylation of NK cells attenuates their cytotoxicity. Notably,

certain molecules, such as the glutathione S-transferase-soluble

HLA-G1α chain fusion protein, inhibit O-GlcNAcylation in NK cells,

thereby enhancing their cytotoxic function (106).

NK group 2D (NKG2D) is an activating receptor on NK

cells that facilitates the recognition and elimination of

virus-infected cells presenting stress-induced ligands associated

with major histocompatibility complex class I molecules (107). The cytotoxic function of

NKG2D-expressing NK cells is regulated by the transcription factor

enhancer of zeste 2 (EZH2), a core subunit of polycomb repressive

complex 2. Inhibition of EZH2 has been shown to accelerate the

maturation of NK cells and improve their killing ability. Notably,

EZH2 contains five O-GlcNAcylation sites, which are pivotal for its

stabilization and function (108–110).

Another transcription factor that induces

cytotoxicity by regulating the O-GlcNAcylation of NK cells is

c-Myc. It upregulates the expression of granzyme B, thereby

increasing the cytotoxic activity of NK cells against

virus-infected cells. O-GlcNAcylation helps to maintain the

stability and function of c-Myc. The substrate for this

modification, UDP-GlcNAc, is generated through glycolysis and the

glutamine metabolic pathway. Glutamine depletion reduces UDP-GlcNAc

levels in NK cells, subsequently impacting c-Myc function and

diminishing cytotoxic activity (111). Thus, O-GlcNAc modification

potentially boosts NK cell immune responses, aiding in the

elimination of infected cells and protecting against the

progression of sepsis.

B cells are activated via the B-cell receptor (BCR)

on their surface, a process that is regulated by O-GlcNAcylation.

This PTM affects the YN proto-oncogene, an Src family tyrosine

kinase, and its interaction with spleen tyrosine kinase to initiate

BCR signaling (112). In

addition, the O-GlcNAcylation of nuclear factor of activated

T-cells, cytoplasmic 1 (NFATc1) and NF-κB further amplifies B cell

activation (113). Following BCR

crosslinking, the interaction between O-GlcNAc-modified

lymphocyte-specific protein 1 (Lsp1) and protein kinase C-β1 is

crucial for the regulation of apoptosis in activated B cells. The

O-GlcNAcylation of Lsp1 at Ser209 facilitates its phosphorylation

at Ser243, thereby modulating Lsp1 function (114). Also, the dysregulation of EZH2

activity or aberrant O-GlcNAcylation may impair antibody production

in B cells, indicating the importance of O-GlcNAcylation in the

modulation of B cell function and antibody responses (115).

CD8+ cytotoxic T cells identify and

destroy infected cells during viral infections. NF-κB and c-Myc are

essential transcription factors in the activation of

CD8+ T cells, and TCR-mediated stimulation induces their

O-GlcNAcylation. The O-GlcNAcylation of c-Rel enhances its binding

to the CD28 response element, resulting in the production of

proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-2, IFN-γ and granulocyte

macrophage-colony-stimulating factor. In addition, site-specific

O-GlcNAcylation stabilizes c-Myc, while the inhibition of OGT

decreases c-Myc levels (116,117). Furthermore, NFATc1 is mainly

O-GlcNAcylated in the cytosol, and translocates to the nucleus

after TCR activation. The O-GlcNAc modification of NFAT has been

demonstrated to be crucial for its nuclear translocation and

function, as the inhibition of OGT decreases TCR-induced IL-2

production and CD69 expression (113). These findings highlight the

importance of O-GlcNAcylation in T cells. The inhibition of OGT has

also been shown to affect the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in

T cells, with the p65 subunit of NF-κB undergoing O-GlcNAcylation

(113,118). In addition, the O-GlcNAcylation

of DNA fragmentation factor 45 shields proteins from

caspase-mediated cleavage during DNA damage-induced T-cell

apoptosis, indicating its protective role against apoptotic cell

death in T cells (119).

Modulating O-GlcNAc glycosylation levels or its

downstream signaling pathways may help to address immune imbalances

in patients with sepsis, suppress excessive inflammation, prevent

organ dysfunction and ultimately improve clinical outcomes.

Role of O-GlcNAcylation in immune cell

recognition of parasitic infections

The dual role of O-GlcNAcylation in host

anti-parasitic immunity and parasite self-regulation has become

increasingly evident. This involves an interaction between the

regulation of host immune cell function and the metabolic

dependence of the parasite on O-GlcNAc pathways. In the

anti-parasitic immunity of the host, O-GlcNAc contributes to key

pathways that regulate type 2 immune responses. For example, the

O-GlcNAcylation of STAT6 in intestinal epithelial cells forms the

first line of defense against helminth infection by driving tuft

cell proliferation and the release of gasdermin C-dependent

alarmins (120). Restoration of

STAT6 activation partially rescues the impaired immune responses to

helminth infection in OGT-deficient mice, which exhibit defective

STAT6 signaling and intestinal villus dysplasia (121). In addition, mast cell function is

closely associated with O-GlcNAc modification: In Trichomonas

vaginalis infection, leukotriene B4 (LTB4) secreted by the

parasite binds to LTB4 receptor 1 on mast cells, elevates O-GlcNAc

levels and promotes NADPH oxidase-dependent migration,

degranulation and IL-8 secretion (122). However, Tet methylcytosine

dioxygenase 2 (TET2)-mediated O-GlcNAcylation affects mast cell

differentiation and cytokine production by regulating chromatin

accessibility (123). These

findings suggest that O-GlcNAc contributes to the anti-parasitic

response through the multifaceted regulation of host immune cell

functions, including Th2 polarization, epithelial barrier defense

and mast cell effector functions.

At the biological level, glycosylation

modifications, including O-GlcNAc-related pathways, are essential

for the survival, development and pathogenicity of parasites. For

example, Plasmodium falciparum relies on the HBP to produce

glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, which are critical

for the invasion of red blood cells and immune evasion. Therefore,

blocking this pathway can lead to the growth arrest of

Plasmodium at the schizont stage (124). Although Cryptosporidium

lacks certain glycosylases, it compensates by hijacking host

glycosylation resources to perform its protein modifications

(125). In addition,

glycosylation in various parasites, such as Plasmodium and

Toxoplasma gondii, affects host immune recognition by

altering the function of surface proteins (126,127). Notably, there is an interaction

between host and parasite O-GlcNAc metabolism: Parasites may

disrupt the glycosylation homeostasis of host immune cells by

secreting metabolites such as GlcNAc, while host-targeted drugs

against key enzymes involved in parasite glycosylation, such as

glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate transaminase (GFAT) in the HBP, can

simultaneously inhibit parasite growth and enhance immune clearance

(124,127).

In summary, O-GlcNAcylation affects infection

outcomes through host-parasite bidirectional regulation: It

regulates host type 2 immune responses and effector cell functions

through targets such as STAT6 and TET2, while parasites rely on

glycosylation pathways to complete their developmental cycles and

evade host immunity. Future studies should aim to further elucidate

the parasite-specific O-GlcNAc modification network and explore

dual intervention strategies, such as the development of GFAT

inhibitors combined with immunomodulators, to synergistically

enhance anti-parasitic immunity and block pathogen

metabolism-dependent virulence mechanisms.

Discussion

O-GlcNAcylation plays diverse roles in different

types of infection by modulating host defense mechanisms and

affecting immune cell function. Specifically, macrophage responses

to infection reveal a key functional divergence of O-GlcNAcylation:

It promotes antiviral defenses but suppresses antibacterial

responses. Given the dual role of O-GlcNAcylation in different

types of infection, the modulation of O-GlcNAcylation activity may

serve as a novel therapeutic strategy. For example, enhancing

O-GlcNAcylation may strengthen the host antiviral response, while

in bacterial infections, moderate inhibition of O-GlcNAcylation may

help to limit inflammatory damage and promote tissue repair.

Therefore, targeting O-GlcNAcylation may represent a potential

approach for the treatment of infectious diseases such as

sepsis.

O-GlcNAc glycosylation is a crucial PTM that

influences protein function by interacting with other PTMs, such as

phosphorylation and ubiquitination (16). For example, O-GlcNAcylation has

been demonstrated to promote protein phosphorylation, including

that of Lsp1 in B cells, where it facilitates interaction with

F-actin (114). Also,

O-GlcNAcylation can modulate the function of ubiquitinated

proteins, including macrophage proteins MAVS and IRF5, which depend

on downstream ubiquitination signaling for proper immune activation

(103–105). Understanding the interplay

between O-GlcNAcylation and other PTMs, such as phosphorylation and

ubiquitination, is crucial for elucidating the role of

O-GlcNAcylation in the regulation of immune cell function in both

homeostatic and infectious states.

Intervention strategies targeting O-GlcNAc

homeostasis have demonstrated multidimensional potential in the

treatment of sepsis. For example, GlcN significantly inhibits

LPS-induced activation of the MAPK and NF-κB inflammatory pathways

by increasing the O-GlcNAc modification of nucleoplasmic proteins,

thereby attenuating lung tissue damage and improving survival in

mouse and zebrafish models (128). In addition, OGT-mediated

modification of O-GlcNAc at RIPK3 Thr467 has been shown to block

the formation of necroptotic complexes and inhibit the inflammatory

storm in sepsis (129). Also, an

acute increase in overall O-GlcNAc levels, such as that induced by

the OGA inhibitor N-butyryl-glucosamine-1,5-lactone

O-(phenylcarbamoyl)oxime, significantly reduces mortality in septic

shock models by inhibiting the cleavage and activation of GSDMD, a

key pyroptosis protein (130,131). At the metabolic level,

O-GlcNAcylation regulates metabolic enzymes such as ATP citrate

lyase in rat models of juvenile sepsis and helps to modulate

systemic inflammatory responses through non-transcriptional

pathways, suggesting its multi-target regulatory advantage

(132,133). However, the clinical application

of OGT/OGA inhibitors faces complex challenges. Specifically, the

inhibition of OGT may have off-target effects that interfere with

protective mechanisms in sepsis. For example, inhibition of OGT may

inadvertently weaken its inhibitory effect on GSDMD-mediated

pyroptosis or impair the glutamine-maintained gut mucus barrier by

interfering with mucin-type glycosylation, potentially through the

cross-inhibition of enzymes such as UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide

N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (5,24,134). In addition, the compensatory

stimulation of OGA or fluctuations in the UDP-GlcNAc metabolic pool

triggered by OGT inhibition may disrupt the N-glycosylation of

immune receptors such as TLR4, thereby exacerbating inflammatory

dysregulation (134–136). However, the spatiotemporal

heterogeneity of O-GlcNAcylation, such as the contrasting roles

observed between endothelial cells and macrophages, and the lack of

cell-specific regulatory tools make it challenging to accurately

target the dynamic pathological processes of sepsis (137,138). Future strategies combining

nano-targeted delivery and dynamic biomarker monitoring are

necessary for the development of spatiotemporally accurate

modification approaches that optimize therapeutic benefits while

minimizing risks.

In summary, as a key PTM, O-GlcNAcylation acts as a

critical link between the immune response to infection and the

progression of sepsis. Future studies should aim to fully elucidate

the specific role of O-GlcNAcylation in the pathogenesis of sepsis,

including the mechanisms by which it activates immune cells,

regulates the inflammatory response and controls the autophagic

process. In addition, the identification of specific

O-GlcNAcylation markers as potential biomarkers may improve the

early diagnosis and prognostic assessment of sepsis, providing

deeper mechanistic insights. Intervention strategies targeting

O-GlcNAcylation may enable the regulation of autophagy and immune

responses, thereby providing new therapeutic options for patients

with sepsis. Such approaches may include the development of

small-molecule drugs to modulate the activity of OGT and OGA, or

the design of interventions targeting specific O-GlcNAcylation

sites.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82260135).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZH and XL wrote and revised this manuscript. PL

designed the subject of review. LZ, YL and XM reviewed and revised

the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Nedeva C: Inflammation and cell death of

the innate and adaptive immune system during sepsis. Biomolecules.

11:10112021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford

KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer

S, et al: Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and

mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the global burden of disease

study. Lancet. 395:200–211. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lockridge A and Hanover JA: A nexus of

lipid and O-Glcnac metabolism in physiology and disease. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 13:9435762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cai H, Xiong W, Zhu H, Wang Q, Liu S and

Lu Z: Protein O-GlcNAcylation in multiple immune cells and its

therapeutic potential. Front Immunol. 14:12099702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wu D, Su S, Zha X, Wei Y, Yang G, Huang Q,

Yang Y, Xia L, Fan S and Peng X: Glutamine promotes O-GlcNAcylation

of G6PD and inhibits AGR2 S-glutathionylation to maintain the

intestinal mucus barrier in burned septic mice. Redox Biol.

59:1025812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Srzić I, Nesek Adam V and Tunjić Pejak D:

Sepsis definition: What's new in the treatment guidelines. Acta

Clin Croat. 61 (Suppl 1):S67–S72. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wiersinga WJ and van der Poll T:

Immunopathophysiology of human sepsis. EBioMedicine. 86:1043632022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Torres LK, Pickkers P and van der Poll T:

Sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Annu Rev Physiol. 84:157–181.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu D, Huang SY, Sun JH, Zhang HC, Cai QL,

Gao C, Li L, Cao J, Xu F, Zhou Y, et al: Sepsis-induced

immunosuppression: Mechanisms, diagnosis and current treatment

options. Mil Med Res. 9:562022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wen X, Xie B, Yuan S and Zhang J: The

‘Self-sacrifice’ of ImmuneCells in sepsis. Front Immunol.

13:8334792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yang L, Zhou L, Li F, Chen X, Li T, Zou Z,

Zhi Y and He Z: Diagnostic and prognostic value of

Autophagy-related key genes in sepsis and potential correlation

with immune cell signatures. Front Cell Dev Biol. 11:12183792023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Reglero-Real N, Pérez-Gutiérrez L,

Yoshimura A, Rolas L, Garrido-Mesa J, Barkaway A, Pickworth C,

Saleeb RS, Gonzalez-Nuñez M, Austin-Williams SN, et al: Autophagy

modulates endothelial junctions to restrain neutrophil diapedesis

during inflammation. Immunity. 54:1989–2004.e9. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhu CL, Wang Y, Liu Q, Li HR, Yu CM, Li P,

Deng XM and Wang JF: Dysregulation of neutrophil death in sepsis.

Front Immunol. 13:9639552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Qin Y, Li W, Liu J, Wang F, Zhou W, Xiao

L, Zhou P, Wu F, Chen X, Xu S, et al: Andrographolide ameliorates

sepsis-induced acute lung injury by promoting autophagy in alveolar

macrophages via the RAGE/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Int

Immunopharmacol. 139:1127192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang H, Bai G, Chen J, Han W, Guo R and

Cui N: mTOR deletion ameliorates CD4 + T cell apoptosis during

sepsis by improving autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Apoptosis.

27:401–408. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ye L, Ding W, Xiao D, Jia Y, Zhao Z, Ao X

and Wang J: O-GlcNAcylation: Cellular physiology and therapeutic

target for human diseases. MedComm (2020). 4:e4562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gonzalez-Rellan MJ, Fondevila MF, Dieguez

C and Nogueiras R: O-GlcNAcylation: A sweet hub in the regulation

of glucose metabolism in health and disease. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13:8735132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chatham JC, Zhang J and Wende AR: Role of

O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine protein modification in cellular

(patho)physiology. Physiol Rev. 101:427–493. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao Q, Zhou S, Lou W, Qian H and Xu Z:

Crosstalk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation in

metabolism: Regulation and mechanism. Cell Death Differ.

32:1181–1199. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

El Hajjar L, Page A, Bridot C, Cantrelle

FX, Landrieu I and Smet-Nocca C: Regulation of Glycogen Synthase

Kinase-3β by Phosphorylation and O-β-Linked

N-Acetylglucosaminylation: Implications on tau protein

phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 63:1513–1533. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cardozo CF, Vera A, Quintana-Peña V,

Arango-Davila CA and Rengifo J: Regulation of Tau protein

phosphorylation by glucosamine-induced O-GlcNAcylation as a

neuroprotective mechanism in a brain ischemia-reperfusion model.

Int J Neurosci. 133:194–200. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

da Costa Rodrigues B, Dos Santos Lucena

MC, Costa A, de Araújo Oliveira I, Thaumaturgo M, Paes-Colli Y,

Beckman D, Ferreira ST, de Mello FG, de Melo Reis RA, et al:

O-GlcNAcylation regulates tyrosine hydroxylase serine 40

phosphorylation and l-DOPA levels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol.

328:C825–C835. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen YF, Zhu JJ, Li J and Ye XS:

O-GlcNAcylation increases PYGL activity by promoting

phosphorylation. Glycobiology. 32:101–109. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yu F, Zhang Z, Leng Y and Chen AF:

O-GlcNAc modification of GSDMD attenuates LPS-induced endothelial

cells pyroptosis. Inflamm Res. 73:5–17. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Correction for Zhang et al. HIPK2

phosphorylates HDAC3 for NF-κB acetylation to ameliorate

colitis-associated colorectal carcinoma and sepsis. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 122:e25060471222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li C, Yu L, Mai C, Mu T and Zeng Y: KLF4

down-regulation resulting from TLR4 promotion of ERK1/2

phosphorylation underpins inflammatory response in sepsis. J Cell

Mol Med. 25:2013–2024. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Dong R, Xue Z, Fan G, Zhang N, Wang C, Li

G and Da Y: Pin1 Promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation by

phosphorylation of p38 MAPK Pathway in Septic Shock. Front Immunol.

12:6202382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Jin L, Yuan F, Dai G, Yao Q, Xiang H, Wang

L, Xue B, Shan Y and Liu X: Blockage of O-linked GlcNAcylation

induces AMPK-dependent autophagy in bladder cancer cells. Cell Mol

Biol Lett. 25:172020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sheng X, Xia Z, Yang H and Hu R: The

ubiquitin codes in cellular stress responses. Protein Cell.

15:157–190. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li MD, Ruan HB, Hughes ME, Lee JS, Singh

JP, Jones SP, Nitabach MN and Yang X: O-GlcNAc signaling entrains

the circadian clock by inhibiting BMAL1/CLOCK ubiquitination. Cell

Metab. 17:303–310. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xu B, Zhang C, Jiang A, Zhang X, Liang F,

Wang X, Li D, Liu C, Liu X, Xia J, et al: Histone methyltransferase

Dot1L recruits O-GlcNAc transferase to target chromatin sites to

regulate histone O-GlcNAcylation. J Biol Chem. 298:1021152022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang Q, Wei D, Li C, Yang X, Su K, Wang T,

Zou R, Wang L, Cun D, Tang B, et al: O-GlcNAcylation with

ubiquitination stabilizes METTL3 to promoting HMGB1 degradation to

inhibit ferroptosis and enhance gemcitabine resistance in

pancreatic cancer. Mol Med. 31:2282025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Koo SY, Park EJ, Noh HJ, Jo SM, Ko BK,

Shin HJ and Lee CW: Ubiquitination links DNA damage and repair

signaling to cancer metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 24:84412023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Dikic I and Schulman BA: An expanded

lexicon for the ubiquitin code. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:273–287.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen L, Li Y, Zeng S, Duan S, Huang Z and

Liang Y: The interaction of O-GlcNAc-modified NLRX1 and IKK-α

modulates IL-1β expression in M1 macrophages. In Vitro Cell Dev

Biol Anim. 58:408–418. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ning M, Liu Y, Wang D, Wei J, Hu G and

Xing P: Knockdown of TRIM27 alleviated sepsis-induced inflammation,

apoptosis, and oxidative stress via suppressing ubiquitination of

PPARγ and reducing NOX4 expression. Inflamm Res. 71:1315–1325.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang J, He Y and Zhou D: The role of

ubiquitination in microbial infection induced endothelial

dysfunction: Potential therapeutic targets for sepsis. Expert Opin

Ther Targets. 27:827–839. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yu Y, Fu Q and Li J, Zen X and Li J: E3

ubiquitin ligase COP1-mediated CEBPB ubiquitination regulates the

inflammatory response of macrophages in sepsis-induced myocardial

injury. Mamm Genome. 35:56–67. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li ZQ, Chen X and Wang Y: Small molecules

targeting ubiquitination to control inflammatory diseases. Drug

Discov Today. 26:2414–2422. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

O-GlcNAc transferase is a key regulator of

DNA methylation and transposon silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

32:1137–1138. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Shin H, Leung A, Costello KR, Senapati P,

Kato H, Moore RE, Lee M, Lin D, Tang X, Pirrotte P, et al:

Inhibition of DNMT1 methyltransferase activity via

glucose-regulated O-GlcNAcylation alters the epigenome. Elife.

12:e855952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lin AP, Qiu Z, Ethiraj P, Sasi B, Jaafar

C, Rakheja D and Aguiar R: MYC, mitochondrial metabolism and

O-GlcNAcylation converge to modulate the activity and subcellular

localization of DNA and RNA demethylases. Leukemia. 36:1150–1159.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Lorente-Sorolla C, Garcia-Gomez A,

Català-Moll F, Toledano V, Ciudad L, Avendaño-Ortiz J, Maroun-Eid

C, Martín-Quirós A, Martínez-Gallo M, Ruiz-Sanmartín A, et al:

Inflammatory cytokines and organ dysfunction associate with the

aberrant DNA methylome of monocytes in sepsis. Genome Med.

11:662019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

El Gazzar M, Yoza BK, Chen X, Hu J,

Hawkins GA and McCall CE: G9a and HP1 couple histone and DNA

methylation to TNFalpha transcription silencing during endotoxin

tolerance. J Biol Chem. 283:32198–32208. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhu Z, Ren W, Li S, Gao L and Zhi K:

Functional significance of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine protein

modification in regulating autophagy. Pharmacol Res.

202:1071202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li S, Ren W, Zheng J, Li S, Zhi K and Gao

L: Role of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine protein modification in

oxidative stress-induced autophagy: A novel target for bone

remodeling. Cell Commun Signal. 22:3582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Jeon M, Park J, Yang E, Baek HJ and Kim H:

Regulation of autophagy by protein methylation and acetylation in

cancer. J Cell Physiol. 237:13–28. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang Q, Na Q and Song W: Moderate

mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition induces autophagy in

HTR8/SVneo cells via O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine signaling. J

Obstet Gynaecol Res. 43:1585–1596. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Qiu Z, Cui J, Huang Q, Qi B and Xia Z:

Roles of O-GlcNAcylation in mitochondrial homeostasis and

cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 13:5712024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Marsh SA, Powell PC, Dell'italia LJ and

Chatham JC: Cardiac O-GlcNAcylation blunts autophagic signaling in

the diabetic heart. Life Sci. 92:648–656. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Rahman MA, Cho Y, Hwang H and Rhim H:

Pharmacological Inhibition of O-GlcNAc transferase promotes

mTOR-Dependent autophagy in rat cortical neurons. Brain Sci.

10:9582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Pyo KE, Kim CR, Lee M, Kim JS, Kim KI and

Baek SH: ULK1 O-GlcNAcylation is crucial for activating VPS34 via

ATG14L during Autophagy initiation. Cell Rep. 25:2878–2890.e4.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Shi Y, Yan S, Shao GC, Wang J, Jian YP,

Liu B, Yuan Y, Qin K, Nai S, Huang X, et al: O-GlcNAcylation

stabilizes the autophagy-initiating kinase ULK1 by inhibiting

chaperone-mediated autophagy upon HPV infection. J Biol Chem.

298:1023412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang J, Li C, Shuai W, Chen T, Gong Y, Hu

H, Wei Y, Kong B and Huang H: Maresin2 fine-tunes ULK1

O-GlcNAcylation to improve post myocardial infarction remodeling.

Eur J Pharmacol. 962:1762232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Alghusen IM, Carman MS, Wilkins HM, Strope

TA, Gimore C, Fedosyuk H, Shawa J, Ephrame SJ, Denson AR, Wang X,

et al: O-GlcNAc impacts mitophagy via the PINK1-dependent pathway.

Front Aging Neurosci. 16:13879312024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Guo B, Liang Q, Li L, Hu Z, Wu F, Zhang P,

Ma Y, Zhao B, Kovács AL, Zhang Z, et al: O-GlcNAc-modification of

SNAP-29 regulates autophagosome maturation. Nat Cell Biol.

16:1215–1226. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Dodson M, Liu P, Jiang T, Ambrose AJ, Luo

G, Rojo de la Vega M, Cholanians AB, Wong PK, Chapman E and Zhang

DD: Increased O-GlcNAcylation of SNAP29 drives Arsenic-induced

autophagic dysfunction. Mol Cell Biol. 38:e00595–e00517. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Pellegrini FR, De Martino S, Fianco G,

Ventura I, Valente D, Fiore M, Trisciuoglio D and Degrassi F:

Blockage of autophagosome-lysosome fusion through SNAP29

O-GlcNAcylation promotes apoptosis via ROS production. Autophagy.

19:2078–2093. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Huang L, Yuan P, Yu P, Kong Q, Xu Z, Yan

X, Shen Y, Yang J, Wan R, Hong K, et al: O-GlcNAc-modified SNAP29

inhibits autophagy-mediated degradation via the disturbed

SNAP29-STX17-VAMP8 complex and exacerbates myocardial injury in

type I diabetic rats. Int J Mol Med. 42:3278–3290. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhou F, Yang X, Zhao H, Liu Y, Feng Y, An

R, Lv X, Li J and Chen B: Down-regulation of OGT promotes cisplatin

resistance by inducing autophagy in ovarian cancer. Theranostics.

8:5200–5212. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Patel A and Faesen AC: Metamorphosis by

ATG13 and ATG101 in human autophagy initiation. Autophagy.

20:968–969. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang X and Jia J: Magnolol improves

Alzheimer's disease-like pathologies and cognitive decline by

promoting autophagy through activation of the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1

pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 161:1144732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Ge Y, Zhou M, Chen C, Wu X and Wang X:

Role of AMPK mediated pathways in autophagy and aging. Biochimie.

195:100–113. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Pizzimenti C, Fiorentino V, Ruggeri C,

Franchina M, Ercoli A, Tuccari G and Ieni A: Autophagy involvement

in Non-neoplastic and neoplastic endometrial pathology: The state

of the art with a focus on carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 25:121182024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wang TF, Feng ZQ, Sun YW, Zhao SJ, Zou HY,

Hao HS, Du WH, Zhao XM, Zhu HB and Pang YW: Disruption of

O-GlcNAcylation homeostasis induced ovarian granulosa cell injury

in bovine. Int J Mol Sci. 23:78152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Xu J, Gu J, Pei W, Zhang Y, Wang L and Gao

J: The role of lysosomal membrane proteins in autophagy and related

diseases. FEBS J. 291:3762–3785. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Wang P and Hanover JA: Nutrient-driven

O-GlcNAc cycling influences autophagic flux and neurodegenerative

proteotoxicity. Autophagy. 9:604–606. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Park S, Lee Y, Pak JW, Kim H, Choi H, Kim

JW, Roth J and Cho JW: O-GlcNAc modification is essential for the

regulation of autophagy in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Mol Life

Sci. 72:3173–3183. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zheng D, Tong M, Zhang S, Pan Y, Zhao Y,

Zhong Q and Liu X: Human YKT6 forms priming complex with STX17 and

SNAP29 to facilitate autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Cell Rep.

43:1137602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Ben Ahmed A, Lemaire Q, Scache J, Mariller

C, Lefebvre T and Vercoutter-Edouart AS: O-GlcNAc dynamics: The

sweet side of protein trafficking regulation in mammalian cells.

Cells. 12:13962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Du P, Zhang X, Lian X, Hölscher C and Xue

G: O-GlcNAcylation and its roles in neurodegenerative diseases. J

Alzheimers Dis. 97:1051–1068. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

He XF, Hu X, Wen GJ, Wang Z and Lin WJ:

O-GlcNAcylation in cancer development and immunotherapy. Cancer

Lett. 566:2162582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Liu C, Dong W, Li J, Kong Y and Ren X:

O-GlcNAc modification and its role in diabetic retinopathy.

Metabolites. 12:7252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Bruserud Ø, Mosevoll KA, Bruserud Ø,

Reikvam H and Wendelbo Ø: The regulation of neutrophil migration in

patients with sepsis: The complexity of the molecular mechanisms

and their modulation in sepsis and the heterogeneity of sepsis

patients. Cells. 12:10032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Zhou YY and Sun BW: Recent advances in

neutrophil chemotaxis abnormalities during sepsis. Chin J

Traumatol. 25:317–324. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Kneass ZT and Marchase RB: Neutrophils

exhibit rapid Agonist-induced increases in protein-associated

O-GlcNAc. J Biol Chem. 279:45759–45765. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Cong R, Sun L, Yang J, Cui H, Ji X, Zhu J,

Gu JH and He B: Protein O-GlcNAcylation alleviates small intestinal

injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion and oxygen-glucose

deprivation. Biomed Pharmacother. 138:1114772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Hossain M, Qadri SM, Xu N, Su Y, Cayabyab

FS, Heit B and Liu L: Endothelial LSP1 modulates extravascular

neutrophil chemotaxis by regulating nonhematopoietic vascular

PECAM-1 Expression. J Immunol. 195:2408–2416. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Machin PA, Johnsson AE, Massey EJ,

Pantarelli C, Chetwynd SA, Chu JY, Okkenhaug H, Segonds-Pichon A,

Walker S, Malliri A, et al: Dock2 generates characteristic

spatiotemporal patterns of Rac activity to regulate neutrophil

polarisation, migration and phagocytosis. Front Immunol.

14:11808862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Kneass ZT and Marchase RB: Protein

O-GlcNAc modulates motility-associated signaling intermediates in

neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 280:14579–14585. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Wu KK, Xu X, Wu M, Li X, Hoque M, Li G,

Lian Q, Long K, Zhou T, Piao H, et al: MDM2 induces

pro-inflammatory and glycolytic responses in M1 macrophages by

integrating iNOS-nitric oxide and HIF-1α pathways in mice. Nat

Commun. 15:86242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Hwang SY, Hwang JS, Kim SY and Han IO:

O-GlcNAc transferase inhibits LPS-mediated expression of inducible

nitric oxide synthase through an increased interaction with mSin3A

in RAW264.7 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 305:C601–C608. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|