Introduction

Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer

and the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. Over 80% of

cases are histologically classified as non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC) (1,2). Surgery is generally the treatment of

choice for early stage NSCLC. However, 30–55% of patients develop

recurrence even following complete resection, and the mortality

rate is high (3). As early disease is

typically asymptomatic, the majority of patients are diagnosed at a

distant stage, resulting in extremely poor prognosis, even with

chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (2).

Recently, computed tomography (CT)-guided iodine-125 interstitial

brachytherapy (125I-IBT) has been employed to treat

NSCLC at the inoperable advanced stage, and in cases with local

recurrence or metastasis following surgery or concurrent

chemoradiotherapy, alone or in combination with other treatments

(3–6).

It was demonstrated that 125I-IBT significantly improves

overall survival and local control, by maximizing the radiation

dose delivered to the tumor, and minimizing radiation injury of the

surrounding normal lung tissue. Certain preclinical studies have

further suggested that increased G2/M arrest, increased apoptosis

and enhanced bystander effect may serve key roles in the

anti-proliferative effects induced by 125I-IBT in NSCLC

(7–9).

However, the association between 125I-IBT and glucose

metabolism in NSCLC remains unclear.

The Warburg effect, a hallmark for tumor cells, was

discovered by Otto Warburg in 1924. It is well established that in

contrast to normal cells, which predominantly rely on mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to generate the energy required

for cellular processes, the majority of tumor cells instead rely on

aerobic glycolysis. The Warburg effect is a determinant of tumor

cell proliferation (10). The rate of

glucose entry into tumor cells is at least 20–30-fold higher than

normal cells. This unique phenomenon is the basis for the use of

positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG), a

radioactive glucose analog that is intensely accumulated by tumor

cells (11). 18F-FDG

PET/CT is widely used for initial diagnosis, disease staging,

recurrence and metastasis detection, as well as for monitoring

chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy response in lung cancer (12–16).

In recent years, several studies have investigated

the Warburg effect in lung cancer progression, as well as for the

development of targeted therapies (17–19). It

was suggested that Sad1 and UNC84 domain containing 2 (SUN2)

protein may suppress lung cancer cell proliferation and migration

by attenuating the Warburg effect, whereas pyruvate dehydrogenase

kinase 1 (PDK1), may promote lung cancer cell proliferation and

migration, via the inverse mechanism. In addition, dichloroacetate,

a metabolic agent, may partially revert the Warburg effect in tumor

cells, increase X-ray sensitivity and inhibit the growth of lung

cancer cells. Based on these previous reports, the present study

aimed to investigate if and how the Warburg effect was involved in

125I-IBT for NSCLC. Herein, it was hypothesized that

125I-IBT may have suppressed tumor growth via Warburg

effect inhibition in NSCLC. Alterations in tumor growth and

18F-FDG uptake were monitored using micro-PET/CT

imaging. In addition, the relationships among these factors, the

expression of glycolysis-associated molecules and the radiation

dose were analyzed in NSCLC A549 ×enografts following

125I-IBT.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and animal model

The A549 cell line was purchased from Shanghai

Jianglin Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cells

were cultured in RPMI-1640 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT,

USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and

0.1 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Cells were trypsinized and harvested once 80–90% confluence was

reached. Male BALB/c-nu mice (18–20 g; 4–6 weeks old) were

purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai,

China) and allowed to acclimatize for 1 week in a specific

pathogen-free room under controlled temperature and humidity prior

to experimental initiation. Following this, ~0.2 ml A549 cell

suspension (1×107 cells/1 ml RPMI-1640) was injected

subcutaneously into the right armpits of the forelegs. After 4

weeks, mice with a xenograft diameter of ~10 mm were used for

study.

Study design

A total of 24 prior mice were randomly divided into

four groups (n=6 per group). The control group without

125I seed implantation, and three treatment groups with

a prescribed dose of 20, 40 and 60 Gy, via 1–2 125I seed

implantation with a radioactivity of 0.3–0.6 mCi, respectively. The

treatment period was 4 weeks. Tumor growth was monitored by

determining the xenograft size every 2 days with a calliper. Before

and 14, 28 days after receiving 125I-IBT, micro-PET/CT

imaging was performed to determine the baseline level and

post-treatment alterations in 18F-FDG uptake. At the end

of study, the mice were euthanized with dislocation of cervical

vertebra after being anesthetized with 3% isoflurane inhalation and

all xenografts were histologically analyzed with

immunohistochemical (IHC) staining.

Interstitial brachytherapy

125I seeds (model 6711; diameter, 0.8 mm;

length, 4.5 mm; half-life, 59.6 days; half value thickness, 1.7 cm

in tissue; main emission, 27.4–31.4 Kev X-ray and 35.5 Kev γ-ray)

were provided by Seeds Biological Pharmacy, Ltd. (Tianjin, China).

The 125I seeds were preloaded into 18-gauge needles and

subsequently implanted into the xenograft center. The radiation

prescribed dose was planned based on the axial micro-CT images

using a brachytherapy treatment planning system (Beijing Astro

Technology, Beijing, China).

Tumor volume

Based on measurements of the short (a) and long (b)

tumor diameters, tumor volume (TV) was calculated, according to the

formula of TV=1/2 × a2 × b. The TV and tumor inhibition

rate (TIR) on day 14 and 28 were defined as TV14,

TV28, TIR14 and TIR28,

respectively. TIR was calculated using the following equation:

TIR=(mean of TVc-mean of TVt)/mean of

TVc ×100%, where TVc was the control TV, and

TVt was the treatment group TV.

Micro-PET/CT imaging

18F-FDG was synthesized by the PET/CT

center in our institution. Following an overnight fast, mice were

injected with ~0.1 mCi 18F-FDG via the tail vein. After

1 h, mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane inhalation and

placed in the prone position in the center of a Siemens Inveon

combined micro-PET/CT scanner (Siemens Preclinical Solution USA,

Inc., Knoxville, TN, USA). Micro-CT scans were performed with a 80

kV X-ray tube voltage, 500 µA current, 150 ms ec exposure time and

120 rotation steps. Micro-PET static acquisition was subsequently

performed for 10 min and the data were processed using the ordered

set expectation maximization algorithm for three dimensional PET

reconstruction. Micro-PET/CT images were analyzed with an Inveon

Research Workplace 4.1 (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The maximum

standardized uptake value (SUVmax; g/ml) of the xenograft was

measured on day 0, 14 and 28 and referred to as SUVmax0,

SUVmax14, SUVmax28, respectively. The

18F-FDG uptake attenuation rate (FUAR) of the xenograft

on day 14 and 28 was defined as FUAR14 and

FUAR28, respectively, using the following equation:

FUAR=(mean SUVmaxc value-mean SUVmaxt

value)/mean SUVmaxc value ×100%, where

SUVmaxc was the control group SUVmax, and the

SUVmaxt was the treatment group SUVmax.

Histological evaluation

All xenografts were fixed in 10% formalin overnight

at 4°C and subsequently embedded in paraffin for histological

section preparation (4 µm). The sections were deparaffinized and

stained with hematoxylin and eosin for normal histological

evaluation. IHC was also performed with antibodies to detect

mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), c-Myc, hypoxia inducible

factor-1α (HIF-1α) and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) expression,

according to manufacturer's instructions. Primary antibodies

(Abcam, Cambridge, UK) used were anti-mTOR ab2732 (diluted 1:200),

anti-c-Myc ab32072 (diluted 1:100), anti-HIF-1α ab16066 (diluted

1:400) and anti-GLUT1 ab652 (diluted 1:200). In brief, sections

were dewaxed and rehydrated prior to quenching in 3% hydrogen

peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity for 10 min.

Antigen retrieval was performed by immersing the sections in

EDTA/Tris solution (pH 9.0) in a microwave oven for 2×15 min.

Sections were cooled at room temperature and washed in PBS for 3×10

min. Following this, sections were blocked in 5% bovine serum

albumin (BSA) for 30 min and subsequently incubated overnight with

primary antibodies at 4°C and rewarmed for 30 min and washed in PBS

for 3×10 min. Then sections were incubated with biotinylated

secondary antibodies at 37°C for 45 min and washed in PBS for 3×10

min, followed by exposure to streptavidin-biotin complex

(Ready-to-use SABC-POD kits: SA1021, goat anti-mouse IgG and

SA1022, goat anti-rabbit IgG) for 45 min at 37°C and

diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB AR1022; both Boster,

Wuhan, China). Staining without primary antibodies was performed in

parallel and served as a negative control. Finally, sections were

counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in ethanol and xylene

and mounted with cover slips using neutral balsam. Each section was

assessed in three random microscopic fields (×200). The expression

of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 was quantified by determining the

mean optical density (MOD) using Image-Pro Plus software (version

6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc. Maryland, USA). The expression

suppression rate (ESR) of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 was defined

as ESRmTOR, ESRc-Myc, ESRHIF-1α

and ESRGLUT1, respectively, using the following

equations: ESR=(mean MODc-mean MODt)/mean

MODc ×100%, where MODc was the control group

MOD, and MODt was the MOD of the treatment groups.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

19.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The continuous

variables were described as the mean ± standard deviation.

Significant differences were evaluated using one-way analysis of

variance. If variances were equal, all pairwise comparisons between

group means were performed with Fisher's Least Significant

Difference test; if unequal, Dunnett's T3 test was used. Pearson's

correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationships among

TV, SUVmax and the MOD of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

125I-IBT inhibits A549

×enograft growth

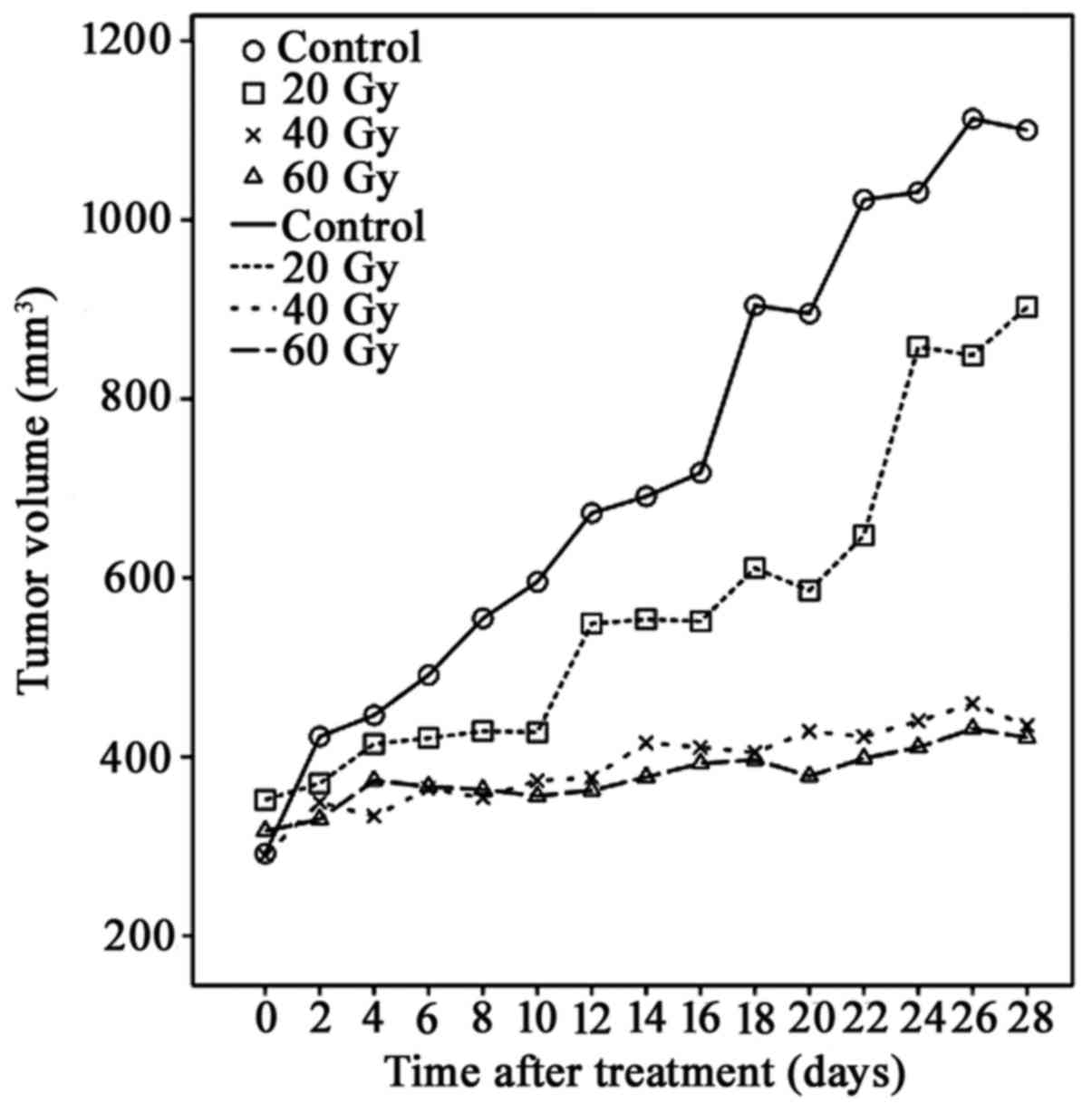

A549 ×enograft growth over time following

125I-IBT was presented in Fig.

1. Overall, the tumor gradually enlarged over time in all

groups, although TV decreased as the radiation dose increased. The

mean TV of the 60 Gy group (377.3±227.2 mm3) and 40 Gy

group (410.7±174.42 mm3) was significantly reduced

compared with controls since day 14 (691.0±258.5 mm3)

and 16 (717.5±212.9 mm3), respectively (P<0.05).

However, no statistical differences were observed between the 20 Gy

group and controls or among all treatment groups (P>0.05). In

addition, the TIR14 of the 20, 40 and 60 Gy groups was

19.9, 39.8 and 45.4%; and the TIR28 were 18.0, 60.5 and

61.7%, respectively. These data suggested that 125I-IBT

may have inhibited the growth of A549 ×enografts, and inhibition

was enhanced as the radiation dose increased.

125I-IBT reduces

18F-FDG uptake in A549 ×enografts

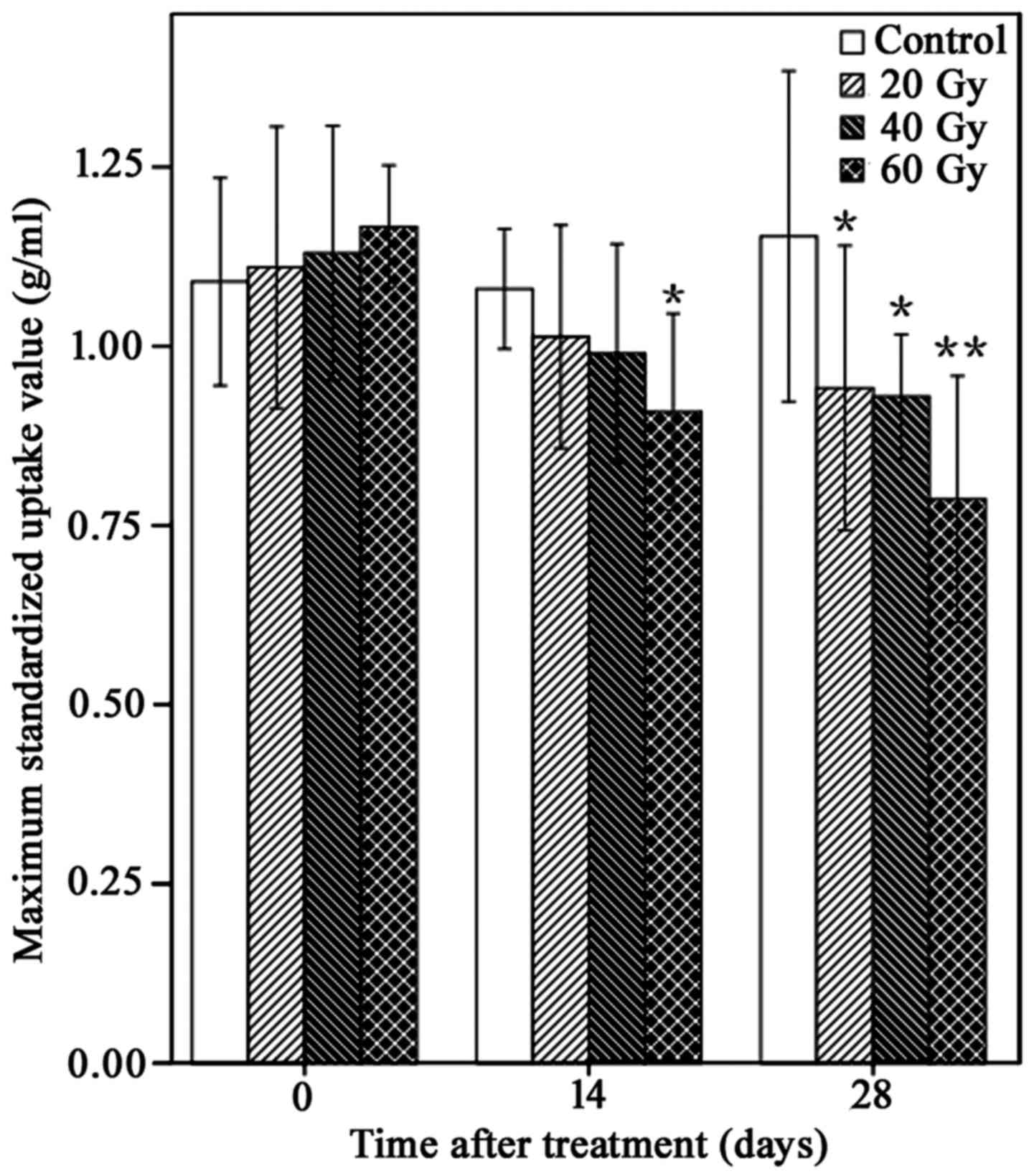

18F-FDG uptake within A549 ×enografts

following 125I-IBT was presented in Fig. 2. In general, compared with controls,

the 18F-FDG uptake of xenografts gradually reduced over

time in 125I-IBT treatment groups. Furthermore, the

reduction in SUVmax was increased as the radiation dose increased

(Fig. 3). The mean of

SUVmax14 of the 60 Gy-group was significantly lower than

the control group (0.91±0.13 g/ml vs. 1.08±0.08 g/ml; P<0.05).

The mean SUVmax28 of all treatment groups was

significantly lower than the control group (20 Gy, 0.94±0.19 g/ml;

40 Gy, 0.93±0.08 g/ml; 60 Gy, 0.79±0.16 g/ml vs. control group,

1.15±0.22 g/ml; P<0.05), although there were no significant

differences among treatment groups on day 14 and 28 (P>0.05).

Furthermore, the FUAR14 of the 20, 40 and 60 Gy groups

was 6.5, 8.3 and 15.7%, and the FUAR28 of the 20, 40 and

60 Gy groups was 18.3, 19.1 and 31.3%, respectively. These data

suggested that 125I-IBT may have reduced

18F-FDG uptake within A549 ×enografts, and this effect

was more marked as the radiation dose increased.

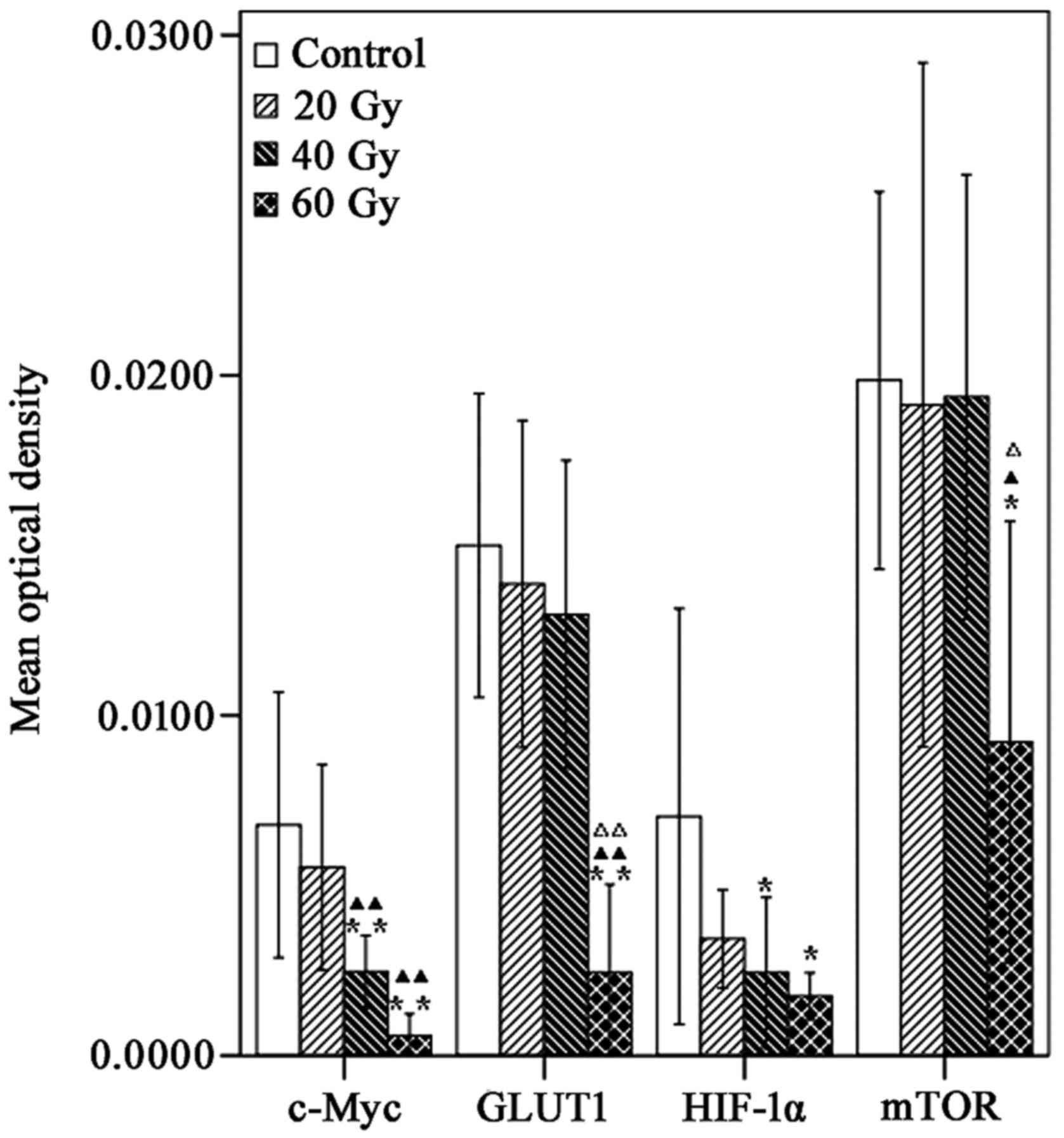

125I-IBT suppresses mTOR,

c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 expression in A549 ×enografts

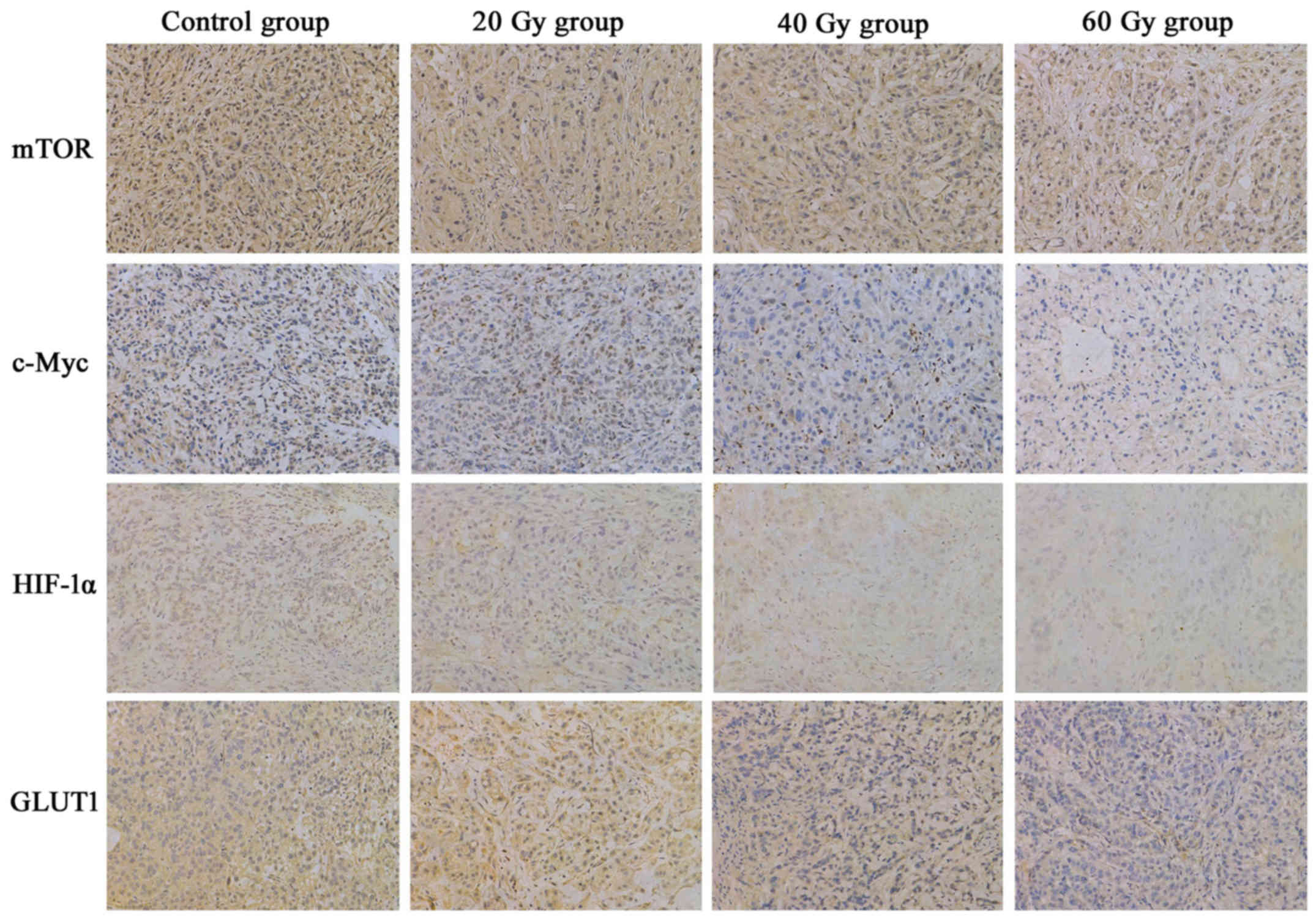

The IHC staining patterns of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and

GLUT1 in A549 ×enografts following 125I-IBT were

presented in Fig. 4. In tumor cells,

mTOR, c-Myc and HIF-1α were expressed in the nucleus and cytoplasm,

whereas GLUT1 was predominantly expressed in the cytomembrane and

cytoplasm. Overall, the expression of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1

in xenografts was gradually downregulated as the radiation dose

increased in the 125I-IBT treatment groups, compared

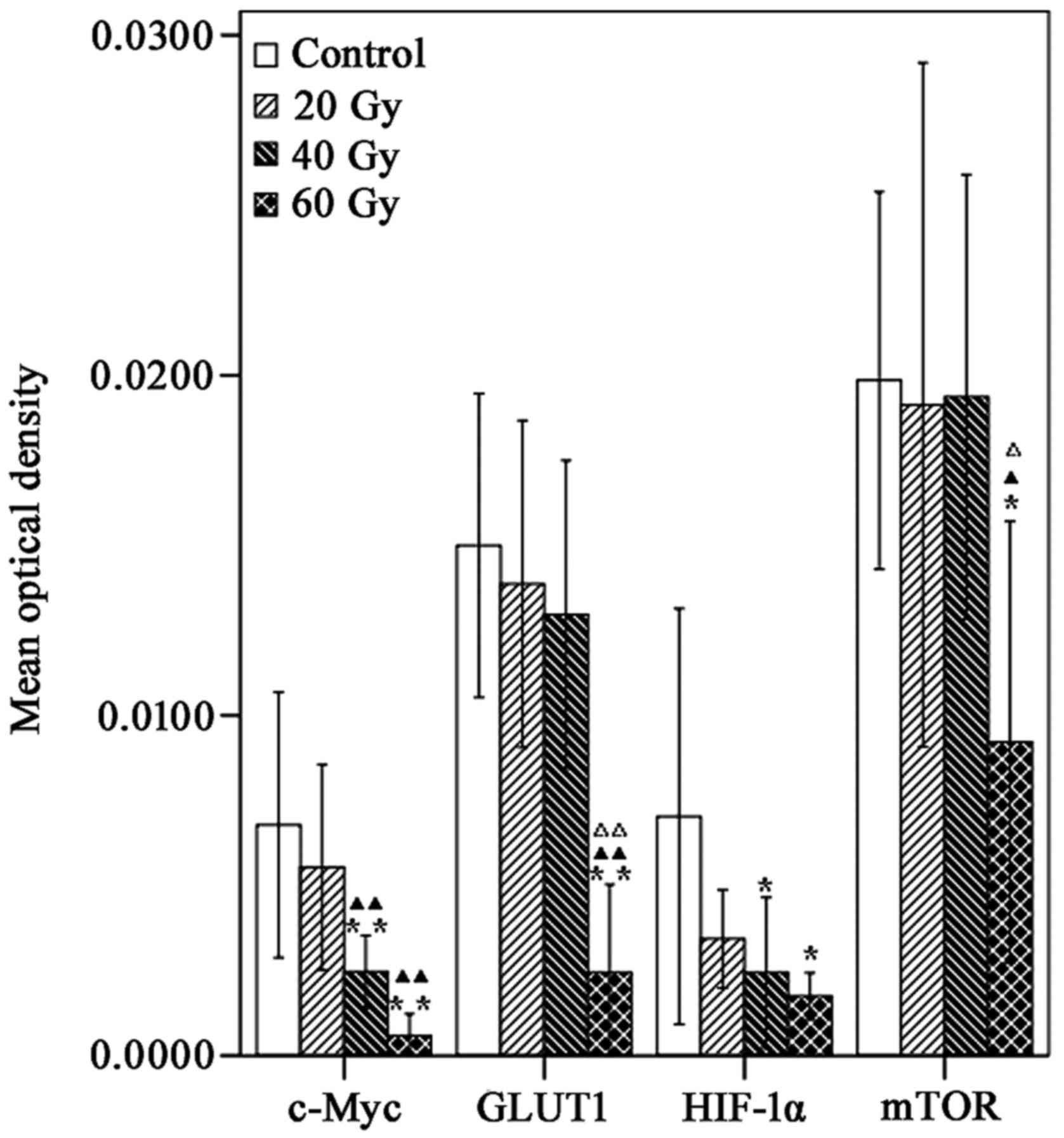

with the controls (Fig. 5). The MOD

of mTOR staining in the 60 Gy-group (0.0092±0.0062) was markedly

decreased compared with the other groups (control, 0.0198±0.0053;

20 Gy, 0.0191±0.0096 and 40 Gy, 0.0194±0.0062; P<0.05). In

addition, the MOD of c-Myc staining was significantly lower in the

40 (0.0025±0.0010) and 60 Gy (0.0006±0.0006) treatment groups,

compared with the other groups (control, 0.0077±0.0020 and 20 Gy,

0.0055±0.0029; P<0.01). Furthermore, the MOD of HIF-1α staining

in the 40 (0.0024±0.0021) and 60 Gy (0.0018±0.0006) treatment

groups was significantly than that of the control group

(0.0070±0.0058; P<0.05). Finally, the MOD of GLUT1 staining in

the 60 Gy (0.0024±0.0025) group was significantly decreased

compared with the other (control, 0.0150±0.0043; 20 Gy,

0.0139±0.0046; 40 Gy, 0.0130±0.0043; P<0.01). However, there

were no significant differences between 20 Gy group and the control

for mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α or GLUT1 expression in A549 ×enografts

(P>0.05). Additionally, the ESRmTOR, in the 20, 40

and 60 Gy groups was 4.0, 2.5 and 53.8%, respectively; the

ESRc-Myc was 28.6, 67.5 and 92.2%, respectively; the

ESRHIF-1α was 51.4, 65.7 and 74.3%, respectively; and

the ESRGLUT1 was 7.3, 13.3 and 84.0%, respectively.

These data suggested that 125I-IBT may have suppressed

the expression of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 in A549 ×enografts,

and the suppression effect was increased as the radiation dose

increased.

| Figure 5.Comparison of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and

GLUT1 staining in A549 ×enografts following 125I-IBT.

The mean optical densities of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1

gradually decreased as the radiation dose increased in treatment

groups, compared with the controls. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs.

controls; ▲P<0.05, ▲▲P<0.01 vs. 20 Gy

group; ΔP<0.05, ΔΔP<0.01 vs. 40 Gy

group. mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; HIF-1α, hypoxia

inducible factor-1α; GLUT1, glucose transporter 1;

125I-IBT, iodine-125 interstitial brachytherapy. |

Relationships among tumor growth,

18F-FDG uptake and expression of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and

GLUT1

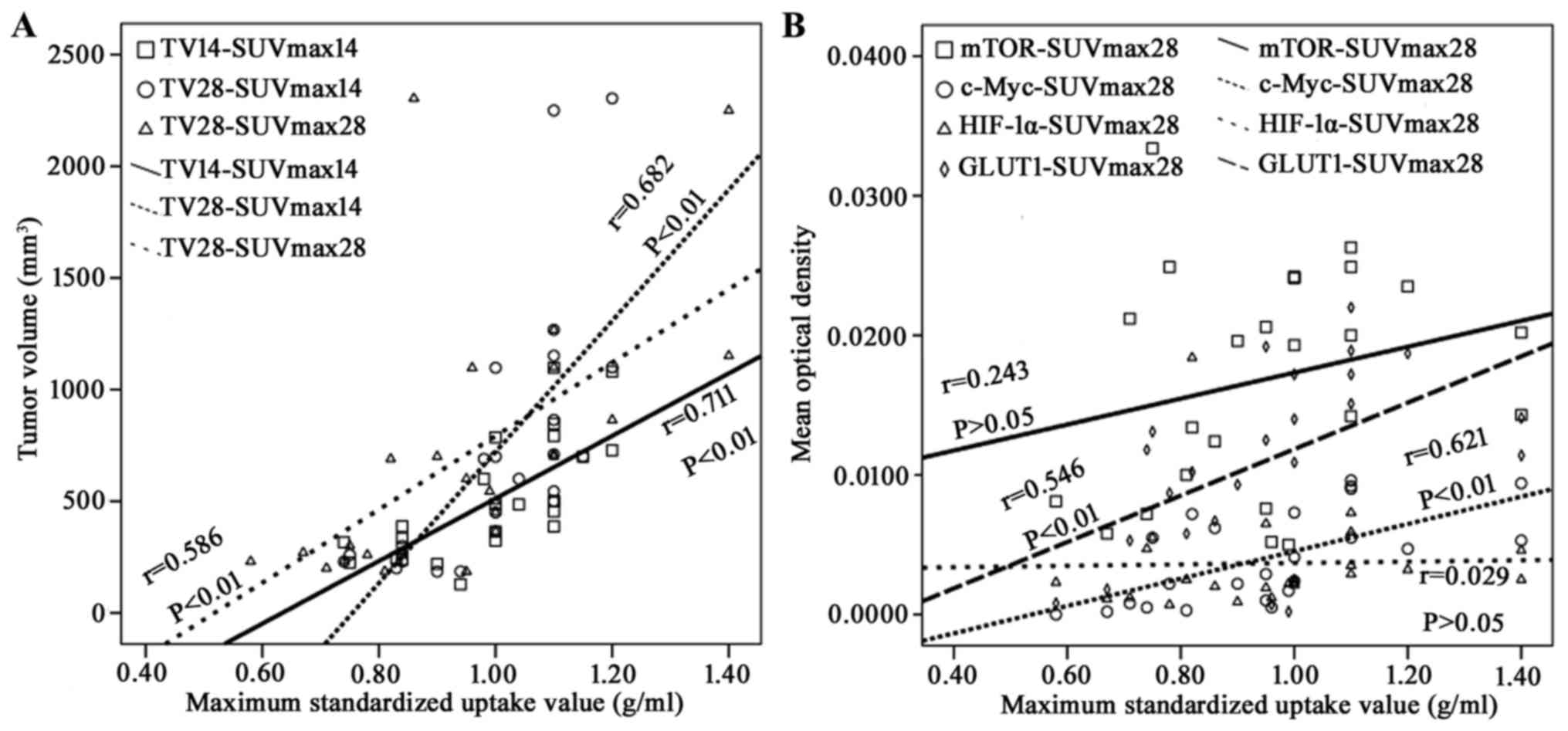

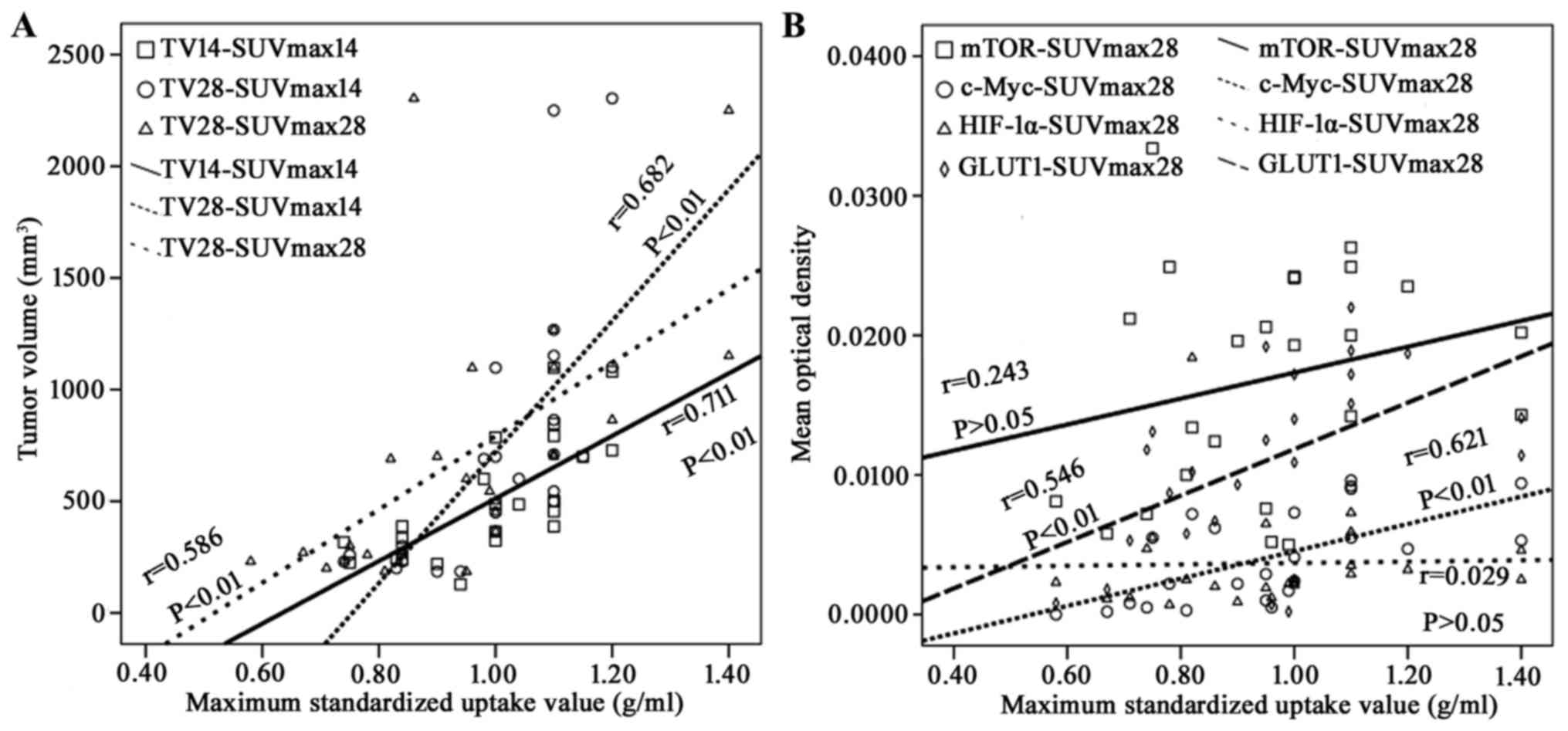

The correlations among tumor growth,

18F-FDG uptake and expression of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and

GLUT1 were presented in Fig. 6. There

was a positive correlation between TV14 and

SUVmax14 (r=0.711), TV28 and

SUVmax14 (r=0.682) and TV28 and

SUVmax28 (r=0.586), respectively (P<0.01). In

addition, SUVmax28 positively correlated to the MOD of

c-Myc (r=0.621) and GLUT1 (r=0.546), respectively (P<0.01).

However, the MOD of mTOR (r=0.243) and HIF-1α (r=0.029) had no

significant correlation with SUVmax28 (P>0.05).

Furthermore, the MOD of mTOR, c-Myc and GLUT1 had a significant

correlation with each other (P<0.05; Table I).

| Figure 6.Relationships among tumor growth,

18F-FDG uptake and expression of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and

GLUT1 in A549 ×enografts following 125I-IBT. (A) TV

positively correlated to SUVmax on day 14 (r=0.711; P<0.01) and

day 28 (r=0.586; P<0.01). TV on day 28 also correlated to SUVmax

on day 14 (r=0.682; P<0.01). (B) SUVmax positively correlated

with the mean optical densities of c-Myc (r=0.621) and GLUT1

(r=0.546) on day 28, respectively (P<0.01). TV, tumor volume;

SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; mTOR, mammalian target

of rapamycin; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor-1α; GLUT1, glucose

transporter 1; 125I-IBT, iodine-125 interstitial

brachytherapy. |

| Table I.Associations among expression of

mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 in A549 ×enograft after

125I-IBT. |

Table I.

Associations among expression of

mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 in A549 ×enograft after

125I-IBT.

| Protein name | mTOR, correlation

coefficient (P-value) | c-Myc, correlation

coefficient (P-value) | HIF-1α, correlation

coefficient (P-value) |

|---|

| c-Myc | 0.500a (0.013) |

|

|

| HIF-1α | −0.003 (0.988) | 0.365 (0.079) |

|

| GLUT1 | 0.526b (0.008) | 0.614b (0.001) | 0.264 (0.212) |

Discussion

In the present study, it was postulated that

125I-IBT may have suppressed NSCLC tumor growth by

inhibiting the Warburg effect. Tumor growth and 18F-FDG

uptake was monitored in NSCLC A549 ×enografts following

125I-IBT with a radiation dose of 20, 40 or 60 Gy, and

the relationships among them were also evaluated. It was

demonstrated that both the TV and SUVmax of all treatment groups

were decreased compared with controls following

125I-IBT, and these reductions were more marked as the

time and radiation dose increased, which was consistent with

results obtained in previous studies of pancreatic carcinoma

xenografts (20,21). In addition, the TIR and FUAR increased

more or less as the radiation dose increased, and TV positively

correlated to SUVmax on day 14 and 28. On the basis of these

results, it can be inferred that 125I-IBT may have

reduced tumor growth by inhibiting the Warburg effect in NSCLC, and

this inhibition increased in a dose-dependent manner more or less.

Notably, it was revealed that SUVmax14 was positively

correlated with TV28 (P<0.05). This suggested that

interim 18F-FDG PET/CT may be a promising strategy to

predict the anti-tumor efficacy of 125I-IBT in NSCLC in

the early stages. 18F-FDG PET/CT is currently used to

predict chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy efficacy in lung cancer

(16), as well as other malignancies

(22,23).

The Warburg effect is considered to involve multiple

intricate mechanisms, including tumor microenvironment support, HIF

stabilization, oncogene activation, tumor suppressor gene loss,

cancer cell mitochondrial dysfunction, nuclear DNA mutations,

epigenetic modifications, microRNA regulation, glutamine metabolism

and post-translational modifications (24). HIF-1, a heterodimeric transcription

factor consisting of α and β subunits, is known to contribute to

the adaptability of tumor cells to hypoxic conditions. It may

increase the efficacy of the glycolytic pathway by upregulating the

expression of several GLUTs and several other genes linked to

aerobic glycolysis (25). For

example, GLUT1 is ubiquitously expressed, but overexpressed in

tumor cells and therefore increases the uptake of glucose. HIF

regulation is predominantly dependent on the HIF-1α subunit, that

has a short half-life under normoxic conditions due to proteasomal

degradation (24,26,27). The

phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) and the

Ras/Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

(MAPKK)/extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK) pathways are

the major signaling pathways downstream from growth factor-bound

receptor tyrosine kinases, which are linked to both growth control

and glucose metabolism in tumor cells (28,29). mTOR,

a serine/threonine kinase, is an important downstream effector of

AKT that stimulates the synthesis of HIF-1α under normoxic

conditions, further enhancing the expression of GLUT1 and

glycolytic enzymes, including lactate dehydrogenase B and pyruvate

kinase M2 (PKM2) (10,24,30). The

suppression of mTOR expression reduces glucose uptake in tumor

cells (31). Furthermore, activated

ERK induces the expression of MYC oncogene, which encodes a

transcription factor c-Myc that is known to be aberrantly

overexpressed in more than half of all human cancers (32). Similar to HIF-1, c-Myc activates GLUT1

and several glycolytic genes, resulting in increased glucose influx

and higher glycolytic rates and contributes to the Warburg effect

(33). In addition, activated c-Myc

may work together with HIF-1 in glycolysis and OXPHOS regulation.

Both HIF and c-Myc activate hexokinase 2 (HK2) and PDK1, leading to

increased glycolytic rates and conversion of glucose to lactate

(27).

In the present study, alterations in mTOR, c-Myc,

HIF-1α and GLUT1 expression was analyzed by IHC techniques, and the

relationship among them was determined. The findings revealed that

the xenograft expression of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 decreased

as the radiation dose increased, with the largest decrease observed

in the 60 Gy group, compared with the controls. Furthermore, the

ESRmTOR, ESRc-Myc, ESRHIF-1α and

ESRGLUT1 was dose-dependently increased, and the MOD of

mTOR, c-Myc and GLUT1 were significantly correlated with each

other. These findings indicated that the Warburg effect was

inhibited by 125I-IBT, which may have resulted from

mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 downregulation in NSCLC A549

×enografts.

Although the downregulation of the above molecules

by 125I-IBT has not been explicitly defined in the

present study, possible involvement of AKT and ERK-mediated

signaling pathways may be suggested in accordance with a previous

report demonstrating that 125I-IBT may downregulate

epidermal growth factor receptor, inhibiting AKT activation in

colorectal tumor cells (34).

125I-IBT has also been demonstrated to suppress vascular

endothelial growth factor-A expression, and consequently inhibit

ERK activation in nasopharyngeal tumor cells (35). It is plausible that AKT and ERK

inactivation may have reduced the expression of mTOR and c-Myc,

resulting in the downregulation of HIF-1α and GLUT1 expression in

the present study. In addition, Cron et al (36) reported that 125I seeds may

significantly increase oxygen partial pressure within 24 h and even

on day 3. Furthermore, it may elevate blood perfusion from day 3,

in 2–4 mm of the surrounding liver tumor region (36). As a result, the improvement of the

tumor hypoxic microenvironment by 125I-IBT may have also

partially reduced the expression and/or accelerated the degradation

of HIF-1α. However, Hu et al (37) demonstrated that 125I-IBT

increases mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

and consequently upregulates the expression of HIF-1α in human

colorectal cancer cells (37).

Therefore, the downregulation of HIF-1α by 125I-IBT may

have been a synthetic action of above factors in NSCLC.

In addition, the correlation analysis between

glucose metabolism and the expression of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and

GLUT1 in the present study revealed that the SUVmax28

positively correlated with the MOD of c-Myc (r=0.621) and GLUT1

(r=0.546). This suggested that 18F-FDG uptake may depend

upon the overexpression of c-Myc and GLUT1 in xenografts,

particularly c-Myc. GLUT1 is the major glucose transporter

expressed in NSCLC. Although its overexpression is considered to be

linked to 18F-FDG uptake within tumors, it is unlikely

that this is the sole or rate-limiting step in this process

(38). The role of GLUT1 remains

controversial in NSCLC; certain studies have reported a significant

correlation (39,40), whereas others have detected no

correlation (41,42). This may be attributed to the fact that

18F-FDG uptake involves tumor blood flow and tracer

delivery rate, in addition to expression of GLUT1. Once

18F-FDG enters tumor cells, hexokinase and

glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) activity determines how much

phosphorylated 18F-FDG is trapped in cells (38). c-Myc, as a central regulator of cell

growth and proliferation (43),

targets genes involved in glucose transport, glycolysis,

glutaminolysis and fatty acid synthesis (44). c-Myc activates GLUT1, as well as HK2

(27) and G6Pase (45), leading to increased uptake of

18F-FDG. Downregulation of c-Myc and GLUT1 suppresses

the glycolytic pathway and glycolytic enzyme activity, leading to

18F-FDG uptake inhibition (46).

However, it was noted that in the present study, no

statistical differences between TV, SUVmax14 and

SUVmax28 were observed among the treatment groups, or

between the TV and the MOD of mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 in the

20 Gy and control group. This may have been due to the short

investigation duration of 28 days, as 125I-IBT is

typically delivered over >180 days (21). Additionally, 60 Gy is a relatively low

radiation dose, considering that the clinically effective dose is

typically 100–160 Gy (3–6). Furthermore, there were no significant

correlations between HIF-1α expression and the other detected

proteins, or between the SUVmax28 and the MOD of mTOR

and HIF-1α (P>0.05). This may be attributed in part to the

complex, multifactorial regulation of HIF-1α as detailed above. In

addition, it suggested that the AKT/mTOR pathway may have less

influence on the Warburg effect in NSCLC, compared with the

ERK/c-Myc pathway.

Certain limitations of the present study should be

considered. First, other key molecules associated with glycolysis

were not examined, such as PKM2 and HK2. Second, the expression of

glycolysis-associated molecules was only evaluated using IHC rather

than via western blotting and/or reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction assays for transcriptional and

translational expression analyses, respectively. Third, A549 cells

harbor the mutant K-ras gene, and the Ras/Raf/ERK signaling pathway

is critical for tumor proliferation. Therefore, multiple NSCLC

cells, including those with the wild-type K-ras gene, should be

used to confirm the results of the present study.

In conclusion, the present study suggested that

125I-IBT may have reduced tumor growth via Warburg

effect inhibition, and this inhibitory effect increased as the

radiation dose increased. Warburg effect inhibition may have

resulted from mTOR, c-Myc, HIF-1α and GLUT1 expression

downregulation, particularly c-Myc and GLUT1, in NSCLC A549

×enografts. Further research is required to clearly delineate the

exact mechanisms underlying Warburg effect inhibition by

125I-IBT in NSCLC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Jiong Yu for the

cell culture assistance, Mr. Li Jiang for helping establishing the

animal model and Mr. Hui Chen for assistance in animal imaging.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Zhejiang

Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant no. LY15H180007) and

Zhejiang Province Medical Health Science Foundation of China (grant

nos. 2015KYB153, 2016KYB099 and 2017KY061).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

JZ established animal models, performed animal

imaging and drafted the manuscript. YZ was responsible for cell

culture and participated in preparation of animal model and

imaging. MD, JY and WW participated in the iodine-125 seed

implantation and immunohistochemistry. LT conceived and designed

the study, performed the statistical analysis and revised the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animals used in the present study received

humane care in compliance with the Guideline to the Care and Use of

Experimental Animals established by the Medical Ethical Committee

on animal experiments of the Zhejiang University.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

125I-IBT

|

iodine-125 interstitial

brachytherapy

|

|

OXPHOS

|

oxidative phosphorylation

|

|

PET/CT

|

positron emission tomography/computed

tomography

|

|

18F-FDG

|

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

|

|

PDK1

|

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1

|

|

TV

|

tumor volume

|

|

TIR

|

tumor inhibition rate

|

|

SUVmax

|

maximum standardized uptake value

|

|

FUAR

|

18F-FDG uptake attenuation

rate

|

|

IHC

|

immunohistochemistry

|

|

mTOR

|

mammalian target of rapamycin

|

|

HIF-1α

|

hypoxia inducible factor-1α

|

|

GLUT1

|

glucose transporter 1

|

|

MOD

|

mean optical density

|

|

ESR

|

expression suppression rate

|

|

PI3K

|

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

|

|

AKT

|

protein kinase B

|

|

MAPKK

|

mitogen-activated protein kinase

kinase

|

|

ERK

|

extracellular regulated protein

kinase

|

|

PKM2

|

pyruvate kinase M2

|

|

HK2

|

hexokinase 2

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

G6Pase

|

glucose-6-phosphatase

|

References

|

1

|

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J,

Lortet-Tieulent J and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:87–108. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB,

Kramer JL, Rowland JH, Stein KD, Alteri R and Jemal A: Cancer

treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin.

66:271–289. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Huo X, Wang H, Yang J, Li X, Yan W, Huo B,

Zheng G, Chai S, Wang J, Guan Z and Yu Z: Effectiveness and safety

of CT-guided (125)I seed brachytherapy for postoperative

locoregional recurrence in patients with non-small cell lung

cancer. Brachytherapy. 15:370–380. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Li W, Guan J, Yang L, Zheng X, Yu Y and

Jiang J: Iodine-125 brachytherapy improved overall survival of

patients with inoperable stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer

versus the conventional radiotherapy. Med Oncol. 32:3952015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yu X, Li J, Zhong X and He J: Combination

of Iodine-125 brachytherapy and chemotherapy for locally recurrent

stage III non-small cell lung cancer after concurrent

chemoradiotherapy. BMC Cancer. 15:6562015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li W, Dan G, Jiang J, Zheng Y, Zheng X and

Deng D: Repeated iodine-125 seed implantations combined with

external beam radiotherapy for the treatment of locally recurrent

or metastatic stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer: A

retrospective study. Radiat Oncol. 11:1192016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chen HH, Jia RF, Yu L, Zhao MJ, Shao CL

and Cheng WY: Bystander effects induced by continuous low-dose-rate

125I seeds potentiate the killing action of irradiation on human

lung cancer cells in vitro. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

72:1560–1566. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Qu A, Wang H, Li J, Wang J, Liu J, Hou Y,

Huang L and Zhao Y: Biological effects of (125)i seeds radiation on

A549 lung cancer cells: G2/M arrest and enhanced cell death. Cancer

Invest. 32:209–217. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang Z, Zhao Z, Lu J, Chen Z, Mao A, Teng

G and Liu F: A comparison of the biological effects of 125I seeds

continuous low-dose-rate radiation and 60Co high-dose-rate gamma

radiation on non-small cell lung cancer cells. PLoS One.

10:e1337282015.

|

|

10

|

Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC and Thompson

CB: Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of

cell proliferation. Science. 324:1029–1033. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ganapathy V, Thangaraju M and Prasad PD:

Nutrient transporters in cancer: Relevance to Warburg hypothesis

and beyond. Pharmacol Ther. 121:29–40. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Liu J, Dong M, Sun X, Li W, Xing L and Yu

J: Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in surgical non-small cell

lung cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 11:e1461952016.

|

|

13

|

Madsen PH, Holdgaard PC, Christensen JB

and Høilund-Carlsen PF: Clinical utility of F-18 FDG PET-CT in the

initial evaluation of lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging.

43:2084–2097. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ruilong Z, Daohai X, Li G, Xiaohong W,

Chunjie W and Lei T: Diagnostic value of 18F-FDG-PET/CT for the

evaluation of solitary pulmonary nodules: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Nucl Med Commun. 38:67–75. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sheikhbahaei S, Mena E, Yanamadala A,

Reddy S, Solnes LB, Wachsmann J and Subramaniam RM: The value of

FDG PET/CT in treatment response assessment, follow-up, and

surveillance of lung cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 208:420–433.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cremonesi M, Gilardi L, Ferrari ME,

Piperno G, Travaini LL, Timmerman R, Botta F, Baroni G, Grana CM,

Ronchi S, et al: Role of interim 18F-FDG-PET/CT for the

early prediction of clinical outcomes of non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC) during radiotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy. A systematic

review. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 44:1915–1927. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Allen KT, Chin-Sinex H, DeLuca T,

Pomerening JR, Sherer J, Watkins JR, Foley J, Jesseph JM and

Mendonca MS: Dichloroacetate alters Warburg metabolism, inhibits

cell growth, and increases the X-ray sensitivity of human A549 and

H1299 NSC lung cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 89:263–273. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lv XB, Liu L, Cheng C, Yu B, Xiong L, Hu

K, Tang J, Zeng L and Sang Y: SUN2 exerts tumor suppressor

functions by suppressing the Warburg effect in lung cancer. Sci

Rep. 5:179402015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu T and Yin H: PDK1 promotes tumor cell

proliferation and migration by enhancing the Warburg effect in

non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 37:193–200. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ma JX, Jin ZD, Si PR, Liu Y, Lu Z, Wu HY,

Pan X, Wang LW, Gong YF, Gao J and Zhao-shen L: Continuous and

low-energy 125I seed irradiation changes DNA methyltransferases

expression patterns and inhibits pancreatic cancer tumor growth. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 30:352011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jian L, Zhongmin W, Kemin C, Yunfeng Z and

Gang H: MicroPET-CT evaluation of interstitial brachytherapy in

pancreatic carcinoma xenografts. Acta Radiol. 54:800–804. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Subocz E, Hałka J and Dziuk M: The role of

FDG-PET in Hodgkin lymphoma. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 21:104–114.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cremonesi M, Garibaldi C, Timmerman R,

Ferrari M, Ronchi S, Grana CM, Travaini L, Gilardi L, Starzynska A,

Ciardo D, et al: Interim 18F-FDG-PET/CT during

chemo-radiotherapy in the management of oesophageal cancer

patients. A systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 125:200–212. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Upadhyay M, Samal J, Kandpal M, Singh OV

and Vivekanandan P: The Warburg effect: Insights from the past

decade. Pharmacol Ther. 137:318–330. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Thorens B and Mueckler M: Glucose

transporters in the 21st Century. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab.

298:E141–E145. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lu H, Forbes RA and Verma A:

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation by aerobic glycolysis

implicates the Warburg effect in carcinogenesis. J Biol Chem.

277:23111–23115. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chen X, Qian Y and Wu S: The Warburg

effect: Evolving interpretations of an established concept. Free

Radic Biol Med. 79:253–263. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Dang CV: Links between metabolism and

cancer. Genes Dev. 26:877–890. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hsieh AL, Walton ZE, Altman BJ, Stine ZE

and Dang CV: MYC and metabolism on the path to cancer. Semin Cell

Dev Biol. 43:11–21. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Makinoshima H, Takita M, Saruwatari K,

Umemura S, Obata Y, Ishii G, Matsumoto S, Sugiyama E, Ochiai A, Abe

R, et al: Signaling through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

(PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) axis is responsible for

aerobic glycolysis mediated by glucose transporter in epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutated lung adenocarcinoma. J Biol

Chem. 290:17495–17504. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Toschi A, Lee E, Thompson S, Gadir N,

Yellen P, Drain CM, Ohh M and Foster DA: Phospholipase D-mTOR

requirement for the Warburg effect in human cancer cells. Cancer

Lett. 299:72–79. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Dang CV: MYC on the path to cancer. Cell.

149:22–35. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Dang CV, Kim JW, Gao P and Yustein J: The

interplay between MYC and HIF in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 8:51–56.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu J, Wang H, Qu A, Li J, Zhao Y and Wang

J: Combined effects of C225 and 125-iodine seed radiation on

colorectal cancer cells. Radiat Oncol. 8:2192013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tian Y, Xie Q, Tian Y, Liu Y, Huang Z, Fan

C, Hou B, Sun D, Yao K and Chen T: Radioactive 125I seed

inhibits the cell growth, migration, and invasion of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma by triggering DNA damage and inactivating VEGF-A/ERK

signaling. PLoS One. 8:e740382013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Cron GO, Beghein N, Crokart N, Chavée E,

Bernard S, Vynckier S, Scalliet P and Gallez B: Changes in the

tumor microenvironment during low-dose-rate permanent seed

implantation iodine-125 brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 63:1245–1251. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hu L, Wang H, Huang L, Zhao Y and Wang J:

The protective roles of ROS-mediated mitophagy on 125I

seeds radiation induced cell death in HCT116 cells. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2016:94604622016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Brown RS, Leung JY, Kison PV, Zasadny KR,

Flint A and Wahl RL: Glucose transporters and FDG uptake in

untreated primary human non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med.

40:556–565. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

van Baardwijk A, Dooms C, van Suylen RJ,

Verbeken E, Hochstenbag M, Dehing-Oberije C, Rupa D, Pastorekova S,

Stroobants S, Buell U, et al: The maximum uptake of

(18)F-deoxyglucose on positron emission tomography scan correlates

with survival, hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha and GLUT-1 in

non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 43:1392–1398. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Suzawa N, Ito M, Qiao S, Uchida K, Takao

M, Yamada T, Takeda K and Murashima S: Assessment of factors

influencing FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer on PET/CT by

investigating histological differences in expression of glucose

transporters 1 and 3 and tumour size. Lung Cancer. 72:191–198.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chung JK, Lee YJ, Kim SK, Jeong JM, Lee DS

and Lee MC: Comparison of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake with

glucose transporter-1 expression and proliferation rate in human

glioma and non-small-cell lung cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 25:11–17.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

de Geus-Oei LF, van Krieken JH, Aliredjo

RP, Krabbe PF, Frielink C, Verhagen AF, Boerman OC and Oyen WJ:

Biological correlates of FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung Cancer. 55:79–87. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dang CV: Rethinking the Warburg effect

with Myc micromanaging glutamine metabolism. Cancer Res.

70:859–862. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Morrish F, Isern N, Sadilek M, Jeffrey M

and Hockenbery DM: c-Myc activates multiple metabolic networks to

generate substrates for cell-cycle entry. Oncogene. 28:2485–2491.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Collier JJ, Doan TT, Daniels MC, Schurr

JR, Kolls JK and Scott DK: c-Myc is required for the

glucose-mediated induction of metabolic enzyme genes. J Biol Chem.

278:6588–6595. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Broecker-Preuss M, Becher-Boveleth N,

Bockisch A, Dührsen U and Müller S: Regulation of glucose uptake in

lymphoma cell lines by c-MYC- and PI3K-dependent signaling pathways

and impact of glycolytic pathways on cell viability. J Transl Med.

15:1582017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|