Introduction

Esophageal cancer is a highly malignant tumor of the

digestive system, characterized by high incidence and mortality

rates. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2020,

53.7% of the global esophageal cancer cases (324,000 new cases) and

55.4% of the associated deaths (301,000 cases) were reported in

China, thus China ranked first in the world in terms of both new

cases and associated deaths. In light of current data, the

prognosis of esophageal cancer is not ideal. Based on data from 60

countries and regions around the world, the age-standardized 5-year

survival rate of esophageal cancer is only 10.0–30.0% (1). As a result, esophageal cancer poses a

major threat to human health.

Numerous clinical studies have clarified the status

of synchronous radiotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced

esophageal cancer (2–4). Due to their efforts, the survival rate

of patients has greatly improved. However, the 5-year survival rate

remains at a low level. More than two-thirds of patients are

diagnosed at advanced stages, where surgical options are no longer

viable. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), as novel therapeutic

tools in clinical practice, have gradually changed the treatment

paradigm of esophageal cancer by exhibiting durable response rates

in some refractory tumors. Over the last 5 years, numerous large

randomized controlled studies have actively explored the efficacy

and safety of immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) in first-line clinical

treatment (5–9). However, survival benefits are still

limited, highlighting the need for further exploration of improved

treatment strategies.

Sintilimab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that

binds to programmed cell death receptor-1 (PD-1) in order to block

the interaction of PD-1 with its ligands [programmed cell

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and polyclonal antibody to mitochondrial

ribosomal protein L2] and consequently help to restore the

endogenous antitumor T-cell response (10). Due to its potential advantages,

sintilimab has been investigated extensively in China, and was

recently approved by the State Drug Administration of China for the

treatment of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma, natural killer/T cell

lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and hepatocellular

carcinoma. To explore its broader applications, sintilimab is

undergoing phase I, II and III development for use in various solid

tumors, including glioblastoma, osteosarcoma and pancreatic

adenocarcinoma, in China (11–13).

Based on the results of the ORIENT-15 study, sintilimab in

combination with chemotherapy has been approved for first-line

treatment of ESCC (14).

When combined with anti-angiogenesis agents, such as

bevacizumab and ramucirumab, ICIs have exhibited synergistic

antitumor effects in preclinical studies (15,16).

Recombinant human-endostatin (rh-endostatin) is a broad-spectrum

anti-angiogenic drug, which is a novel recombinant human vascular

endothelial inhibitor drug independently developed in China.

Rh-endostatin inhibits endothelial cell migration, impedes

angiogenesis and reduces tumor blood supply, thereby suppressing

tumor growth and metastasis. Additionally, the drug enhances the

local tumor microenvironment and induces tumor cell death,

potentially prolonging patient survival (17). It has also been reported that

rh-endostatin combined with conventional chemotherapy can improve

therapeutic outcomes in numerous malignant tumors, including lung,

breast and colorectal cancer (18–21).

However, its combination with chemotherapy for advanced ESCC

remains underexplored.

Considering the potential therapeutic benefits of

rh-endostatin combined with sintilimab and chemotherapy, the

present study collected clinicopathological data from 31 patients

with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic ESCC treated with

rh-endostatin combined with sintilimab, paclitaxel liposome and

platinum (TP regimen) as a first-line treatment. Subsequently, the

overall effective rate, incidence of adverse events (AEs) and

survival times were assessed.

The present study aimed to provide effective

combination medication regimens and supportive evidence to improve

the efficiency of first-line treatment for advanced ESCC, improve

the prognosis of patients and provide a theoretical basis for the

clinical exploration of novel treatment regimens.

Patients and methods

Study design

The present retrospective analysis included data

from 31 patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic

esophageal cancer who received treatment with rh-endostatin in

combination with sintilimab and the TP regimen at the First

Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, China)

between January 2019 and December 2023. The objective was to assess

the clinical efficacy and AEs associated with this regimen.

Patient eligibility

A total of 31 patients with unresectable locally

advanced or metastatic esophageal cancer treated with rh-endostatin

in combination with sintilimab and the TP regimen on a first-line

basis were retrospectively included. All the patients included in

this study provided written informed consent agreeing to the use of

their clinical data and biological samples.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients

with histologically confirmed unresectable locally advanced,

recurrent or metastatic ESCC; ii) patients who were underwent

first-line treatment with rh-endostatin in combination with

sintilimab and the TP regimen; iii) patients with at least one

evaluable lesion according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid

Tumors (RECIST 1.1) classification (22); iv) patients with an expected

survival time ≥3 months; and v) patients with adequate heart, lung,

liver and kidney function.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients

who were severely malnourished (weight <40 kg or body mass index

<18), or who required tube feeding; ii) patients who had major

surgery within 30 days prior to study treatment; iii) patients with

other malignant tumors that have not been cured within 2 years

(except for patients with a combination of other early-stage tumors

that have been treated radically and are assessed by the

investigator to be at low risk of recurrence in the short term);

iv) patients with active infections who still require systemic

therapy 7 days prior to administration of the first dose of

treatment in this study; v) patients who are allergic to the drugs

or related ingredients involved in this study; vi) patients who are

currently enrolled in other interventional clinical studies; vii)

patients who have not recovered from prior antitumor-related AEs to

CTCAE Grade 1 prior to the first dose; viii) patients with a

tendency or history of thrombosis or bleeding, regardless of

severity, within 60 days prior to the first dose; and ix) patients

with any serious or unstable medical condition or mental illness;

patients with known active alcohol or drug abuse or dependence.

Data collection

The patients in this study were selected from the

biobank of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical

University. All donors of clinical data had provided informed

written consent, agreeing that the related information could be

used for all medical research. Medical records for this study were

collected and obtained in January 2024. During the survival

follow-up process, follow-up surveys were conducted via telephone

with patients who had previously used the drug or with their family

members.

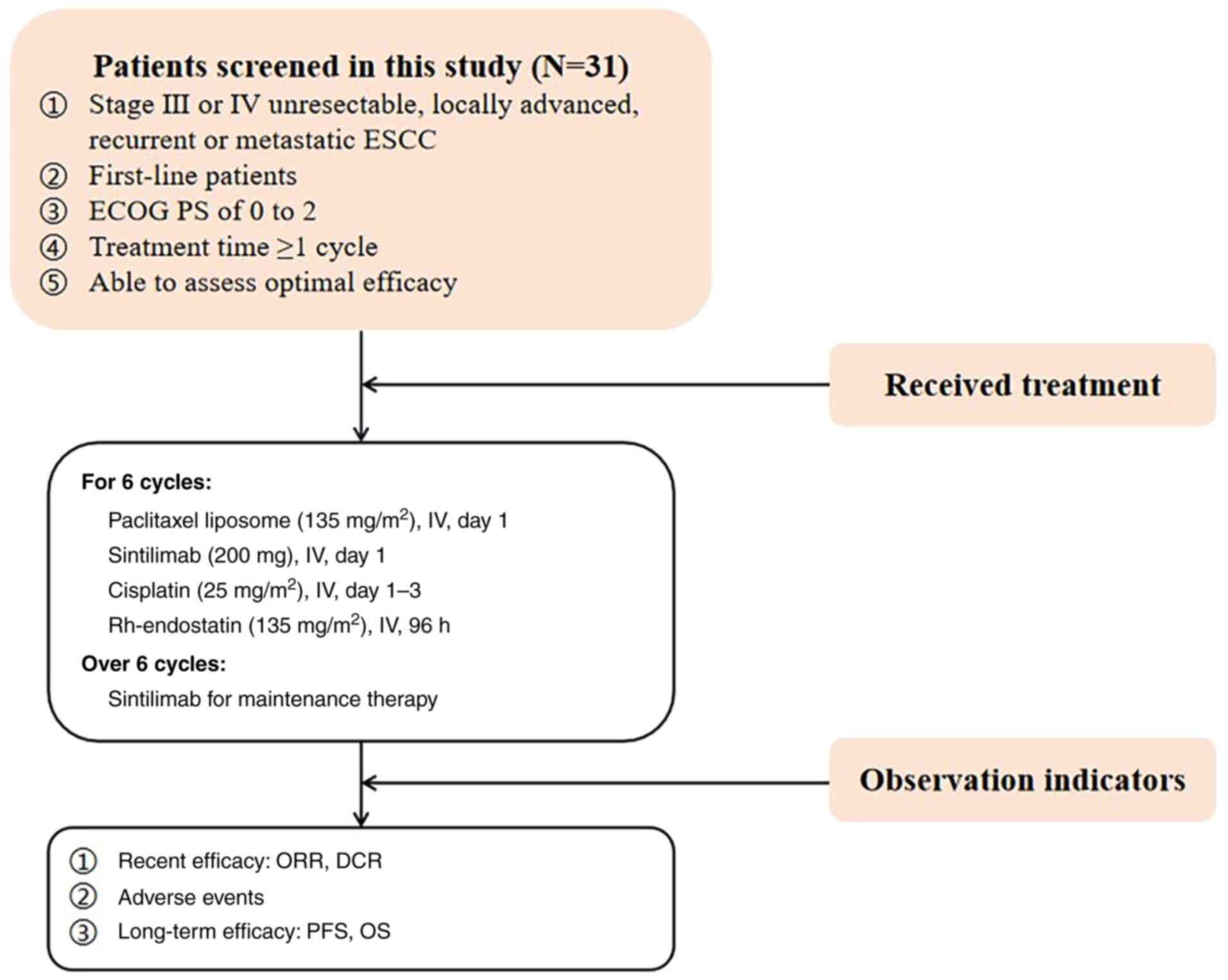

Treatment plan

All included patients received rh-endostatin

combined with sintilimab and the TP regimen. Based on the dosage

applied in previous studies, the continuous intravenous infusion of

cisplatin (25 mg/m2) was administrated consecutively

from the first day to the third day, with paclitaxel liposome (135

mg/m2) administrated on day 1, sintilimab (200 mg) on

day 1 and continuous intravenous infusion of rh-endostatin (135

mg/m2) on day 1 for 96 h (14). All treatments were applied

intravenously every 3 weeks as one cycle, with 6 cycles completed.

Following the completion of 6 cycles, maintenance therapy with

sintilimab was administered until disease progression occurred

(Fig. 1).

Baseline and follow-up assessment

Baseline assessments included age, sex, pathological

type, stage, metastasis, PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS)

(23), Eastern Cooperative Oncology

Group performance status (ECOG PS) (24) and smoking status. AEs were monitored

weekly during treatment. Efficacy was assessed every two treatment

cycles based on the RECIST 1.1 guidelines (22).

The follow-up assessment included recent efficacy,

AEs and long-term efficacy. The recent efficacy of patients was

classified as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable

disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD), and the total efficacy

rate was calculated as CR + PR, according to the WHO solid tumor

efficacy evaluation criteria (25).

The objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR)

can be calculated from the CR, PR, SD and PD. The ORR was defined

as the percentage of patients achieving CR and PR. The DCR was

defined as the percentage of patients achieving CR, PR and SD. The

AE evaluation was performed within 5 months after the

administration of the drug according to the RECIST 1.1 guidelines.

Treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) were graded according to the National

Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events 4.0

guidelines (26). For long-term

efficacy, survival statistics were obtained for the 31 patients by

telephone follow-up or outpatient follow-up. The survival time was

defined as the time from the initial chemotherapy to death or the

follow-up cut-off date.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24.0;

measurements are expressed as median (Q3-Q1), and comparisons were

made using Wilcoxon's rank-sum test and Kruskal-Wallis test. Counts

are expressed as percentages, and the test level was α=0.05. The

median follow-up period, progression-free survival (PFS) time and

overall survival (OS) time were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier

method.

A clinical heterogeneity analysis was performed

using Wilcoxon's rank-sum test and Kruskal-Wallis test, with the

overall population stratified into groups based on different

subgroup characteristics. Wilcoxon's rank-sum test was used to

compare quantitative efficacy between two groups and the

Kruskal-Wallis test was used for multiple groups. The specific

dataset consisted of the PFS time and the total follow-up time of

the groups. P<0.05 was used to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 31 patients with unresectable locally

advanced or metastatic esophageal cancer were included in the

present study. Of these, 83.9% (26/31) were male and 16.1% (5/31)

were female, with a median age of 68 years (range, 56–77 years).

All patients had histologically confirmed ESCC, and metastasis

occurred in the liver (5 cases), lung (5 cases), bone (1 case) and

peritoneum (1 case) (Table I).

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of included

patients (n=31). |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of included

patients (n=31).

| Baseline

characteristics | n (%) |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

<65 | 7 (22.6) |

|

≥65 | 24 (77.4) |

| Sex |

|

|

Male | 26 (83.9) |

|

Female | 5 (16.1) |

| Pathological

type |

|

|

Adenocarcinoma | 0 (0.0) |

|

Squamous carcinoma | 31 (100.0) |

|

Others | 0 (0.0) |

| Stage |

|

|

III | 17 (54.8) |

| IV | 14 (45.2) |

| No. of metastatic

sites |

|

|

<2 | 14 (45.2) |

| ≥2 | 17 (54.8) |

| Liver

metastasis |

|

|

Absent | 26 (83.9) |

|

Present | 5 (16.1) |

| Bone

metastasis |

|

|

Absent | 30 (96.8) |

|

Present | 1 (3.2) |

| Lung

metastasis |

|

|

Absent | 26 (83.9) |

|

Present | 5 (16.1) |

| Peritoneal

metastasis |

|

|

Absent | 30 (96.8) |

|

Present | 1 (3.2) |

| PD-L1 tumor

proportion score |

|

|

<10% | 12 (38.7) |

|

≥10% | 2 (6.5) |

| Could

not be evaluated | 17 (54.8) |

| ECOG PS |

|

| 0-1

points | 29 (93.5) |

| 2

points | 2 (6.5) |

| Smoking status |

|

|

Never | 14 (45.2) |

|

Former/current | 17 (54.8) |

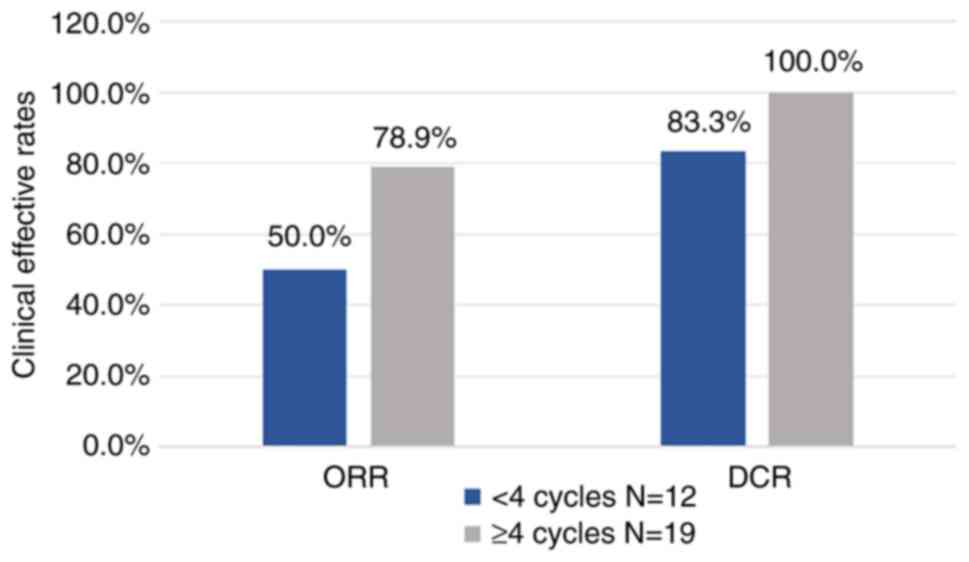

Clinical efficacy

The data cut-off date for the analysis was July 17,

2024, with a median follow-up duration of 13.067 months (95% CI,

10.267–15.866 months). In the overall sample, a total of 31

patients were eligible for efficacy analysis. For the whole cohort,

the ORR was 67.7% and the DCR was 93.5%. The data showed that of

the 12 patients who received <4 treatment cycles, 0% achieved

CR, 50.0% achieved PR, 33.3% achieved SD and 16.7% achieved PD.

Additionally, of the 19 individuals who received ≥4 treatment

cycles, 10.5% achieved CR, 68.4% achieved PR and 21.1% achieved SD.

For patients with <4 treatment cycles, the ORR reached 50%, and

the DCR reached 83.3%. Compared with fewer treatment cycles, both

ORR and DCR were improved with ≥4 treatment cycles, reaching 78.9

and 100.0%, respectively (Table

II; Fig. 2).

| Table II.Results of clinical efficacy. |

Table II.

Results of clinical efficacy.

| Best response | Overall (n=31) | <4 cycles

(n=12) | ≥4 cycles

(n=19) |

|---|

| CR, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (10.5) |

| PR, n (%) | 19 (61.3) | 6 (50.0) | 13 (68.4) |

| SD, n (%) | 8 (25.8) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (21.1) |

| PD, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| ORR, % | 67.7 | 50.0 | 78.9 |

| DCR, % | 93.5 | 83.3 | 100.0 |

In subgroup analyses, patients were grouped

according to characteristics, including age, sex, stage, TPS, ECOG

PS and smoking status. Each subgroup member had a corresponding PFS

time and total follow-up time, and Wilcoxon's rank-sum test or

Kruskal-Wallis test was performed between subgroups. No significant

differences were found between the different subgroups based on

age, sex, stage, PD-L1 TPS, ECOG PS or smoking status in terms of

PFS (Table III). The OS in some

subgroups was not reached, making statistical comparison

infeasible.

| Table III.Subgroup analysis of PFS and OS in

the 31 patients. |

Table III.

Subgroup analysis of PFS and OS in

the 31 patients.

| Variable | Patients, n

(%) | PFS,

monthsa | OS,

monthsa | P-value (PFS) |

|---|

| Age, years |

|

|

| 0.422 |

|

<65 | 7 (22.6) | 4.267

(3.400–15.767) | NR |

|

|

≥65 | 24 (77.4) | 8.300

(4.333–23.067) | 23.067

(5.733-NR) |

|

| Sex |

|

|

| 0.259 |

|

Male | 26 (83.9) | 5.733

(4.267–23.067) | 23.067

(9.767-NR) |

|

|

Female | 5 (16.1) | 12.633

(9.933–15.767) | NR |

|

| Stage |

|

|

| 0.171 |

|

III | 17 (54.8) | 11.967

(4.800–23.067) | 23.067

(5.733-NR) |

|

| IV | 14 (45.2) | 5.367

(3.400–10.367) | NR |

|

| PD-L1 tumor

proportion score |

|

|

| 0.814 |

|

<10% | 12 (38.7) | 9.933

(4.333–12.633) | 13.067

(4.333-NR) |

|

|

>10% | 2 (6.5) | 4.333

(4.333–8.300) | NR |

|

| Could

not be evaluated | 17 (54.8) | 8.100

(4.067–23.067) | 23.067

(23.067-NR) |

|

| ECOG PS |

|

|

| 0.634 |

| 0

points | 14 (45.2) | 9.033

(4.267–23.067) | 23.067

(23.067-NR) |

|

| ≥1

points | 17 (54.8) | 5.733

(4.333–12.633) | NR |

|

| Smoking status |

|

|

| 0.937 |

|

Never | 14 (45.2) | 8.100

(4.800-NR) | NR |

|

|

Former/current | 17 (54.8) | 9.933

(3.367–15.767) | 23.067

(13.067-NR) |

|

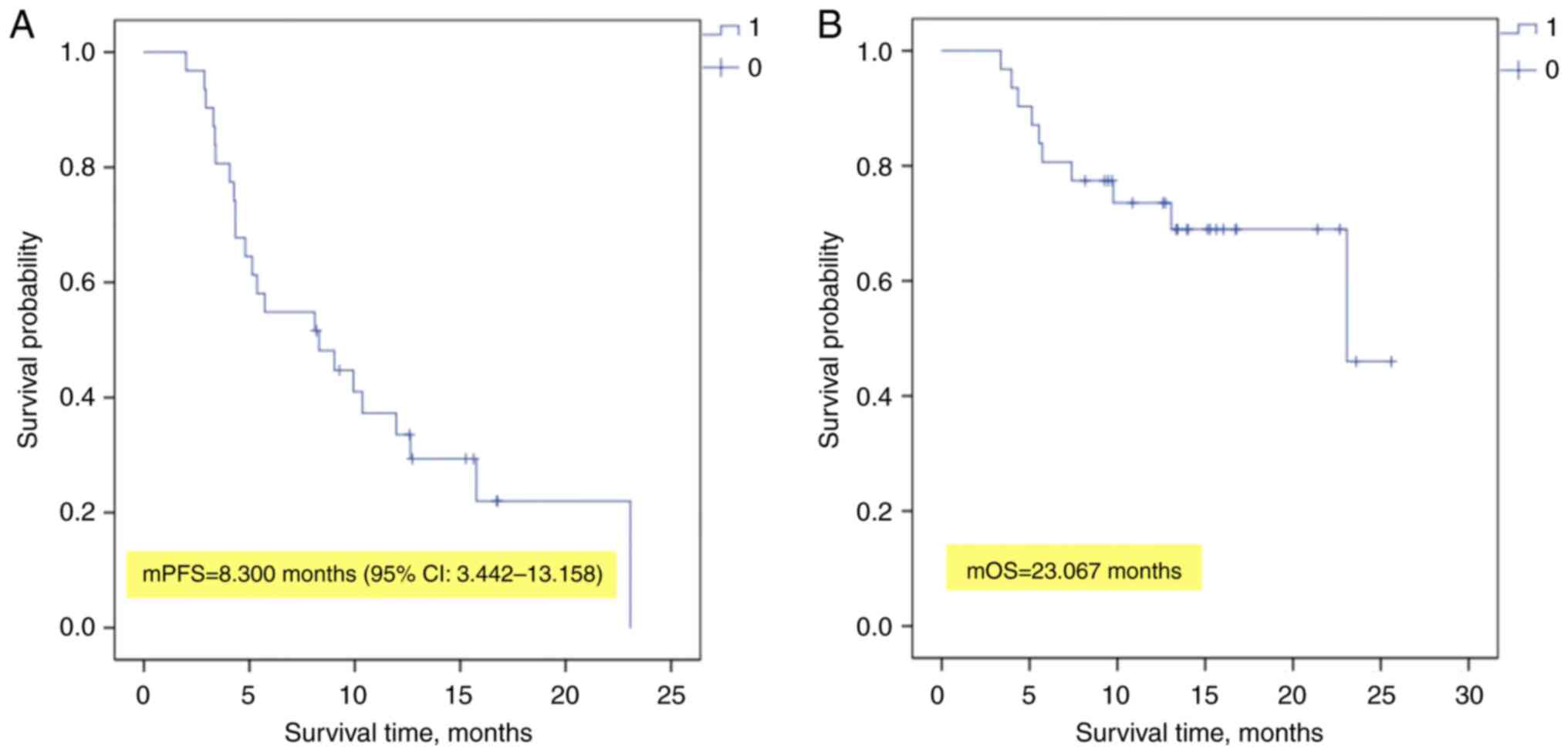

For the entire cohort, the median PFS time was 8.30

months (95% CI, 3.442–13.158 months) and the median OS time reached

23.07 months (Fig. 3).

AEs

The AEs are outlined in Table IV. Among the 31 patients with ESCC

included in the safety analysis, 24 (77.4%) experienced at least

one TRAE, with 35.5% (11/31) reporting grade ≥3 TRAEs. The most

common TRAEs were anemia (83.9%; 26/31), thrombocytopenia (38.7%;

12/31) and neutropenia (32.3%; 10/31). The most serious AEs,

including grade ≥3 events, were neutropenia and anemia; each was

observed in 9.7% (3/31) of patients. No unexpected AEs were

observed during the study.

| Table IV.Profile of AEs in the 31

patients. |

Table IV.

Profile of AEs in the 31

patients.

| AEs | Any grade | Grade ≥3 |

|---|

| Hematological

adverse event |

|

|

|

Neutropenia | 10 (32.3) | 3 (9.7) |

|

Thrombocytopenia | 12 (38.7) | 2 (6.5) |

|

Anemia | 26 (83.9) | 3 (9.7) |

| Non-hematological

adverse events |

|

|

| Nausea

or vomiting | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

Rash | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) |

|

Fatigue | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

Hemorrhage | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Immune-related

adverse events |

|

|

|

Reactive cutaneous capillary

endothelial proliferation | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

Immune-mediated

pneumonitis | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) |

| Liver

injury | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Kidney

injury | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) |

|

Hypothyroidism | 5 (16.1) | 0 (0.0) |

|

Diarrhea and colitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cardiac

creatine kinase level change | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.2) |

| Hair

loss | 9 (29.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Discussion

The present retrospective study evaluated the

efficacy and safety of rh-endostatin in combination with sintilimab

and chemotherapy in patients with advanced ESCC. The exploratory

findings suggested that, compared with the chemotherapy combined

with immunotherapy regimens, rh-endostatin in combination with

sintilimab and chemotherapy exhibited favorable efficacy in

improving survival and treatment outcomes in patients with locally

advanced or metastatic ESCC, with a manageable safety profile.

In the ORIENT-15 study, the PFS and OS times of the

treatment modality involving sintilimab combined with chemotherapy

were found to be 7.2 and 16.7 months, respectively. This indicated

that, compared with the traditional radiotherapy and chemotherapy

regimens, sintilimab combination chemotherapy markedly prolonged

OS, improved PFS and increased the overall remission rate in

patients with locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic ESCC.

Additionally, this combination therapy had a manageable safety

profile compared with placebo-based chemotherapy, regardless of the

PD-L1 expression level (14).

Therefore, sintilimab in combination with chemotherapy is

recommended as a novel first-line standard treatment for locally

advanced, recurrent or metastatic ESCC by the Chinese Society of

Clinical Oncology guidelines (27).

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) serves a

crucial role in the development of ESCC; it is upregulated in the

tumor microenvironment, leading to the formation of abnormal and

incomplete blood vessel networks around the tumor, which limits

immune cell infiltration. The blood vessels formed under the

influence of VEGF are often structurally abnormal, resulting in

impaired blood flow. These VEGF-induced vessels typically exhibit

leakage, fluid accumulation and irregular barrier functions. The

abnormal vasculature also contributes to increased interstitial

pressure within the tumor microenvironment. As a result, poor blood

flow, leakage and high interstitial pressure hinder the effective

penetration of immune cells into the tumor tissue, thereby

weakening the antitumor response of the immune system (28,29).

Targeting the aforementioned mechanisms, recent

studies have shown that combination of anti-angiogenic treatment

with immunotherapy can improve antitumor efficacy (30,31).

On the one hand, antiangiogenic drugs not only reverse the

immunosuppressive effect caused by serum VEGF, but also normalize

the tumor vascular system, promote the exudation and perivascular

accumulation of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes expressing

γ-interferon (IFN-γ), and may induce or increase active T-cell

transit to specific tumor antigens or other effector cells of the

immune system. On the other hand, ICIs can restore the

immune-supportive microenvironment, normalize the tumor vascular

system by activating effector T cells and upregulating the

secretion of IFN-γ, increase the infiltration and killing function

of effector T cells, facilitate the delivery of drugs, reduce the

dosage of ICIs and decrease the risk of AEs (32–36).

Overall, the combination of anti-angiogenesis treatment and

immunotherapy holds promise for improving the immune

microenvironment while normalizing tumor vasculature, thereby

enhancing therapeutic efficacy.

The Empower study, presented at the 2022 American

Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, explored the efficacy

of sintilimab in combination with recombinant human vascular

endothelial inhibitor plus standard platinum-containing two-agent

chemotherapy (pemetrexed + carboplatin/cisplatin) for the

first-line treatment of advanced non-squamous NSCLC in

driver-negative NSCLC (37). The

combination therapy resulted in an ORR of 53% and a DCR of 93%.

Most AEs were grade 1–2 AEs, suggesting that the combination of

recombinant human vascular endothelial inhibitor, immunotherapy and

chemotherapy offers promising efficacy and safety (18). The favorable safety and tolerability

of the combination mode in the Empower study further supports the

exploration and application of the combination regimen of

immunological and antiangiogenic drugs.

In order to improve antitumor efficacy, the present

retrospective study was theoretically based on anti-angiogenesis

treatment combined with immunotherapy. The present study aimed to

explore a potentially optimal treatment regimen by adding the

anti-angiogenic agent rh-endostatin to a chemotherapy and

immunotherapy protocol. The regimen seemed to have a promising

clinical efficacy. Thus, the present study retrospectively analyzed

the data from these patients. Although the analysis was

retrospective, rigorous screening was performed in the patient

selection process, and the treatment process was subjected to

rigorous quality control, closely aligning with the requirements of

a prospective trial.

In the short-term efficacy assessment, improved ORR

and DCR were observed. The study demonstrated that the ORR and DCR

were 67.7 and 93.5% respectively, while in the ORIENT-15 study, the

ORR and DCR were 66.1 and 90.2% respectively. This indicated that

the present results seemed to show an upward trend. However, this

may be related to the relatively small sample size in the present

study, and thus it should be interpreted with caution. In patients

receiving longer cycles of treatment, the improvements in ORR and

DCR seemed to be more marked. Specifically, the ORR was 78.9% for

those receiving ≥4 cycles of treatment, compared with 67.7% for the

overall cohort, and the DCR was 100.0% in patients receiving ≥4

cycles, compared with 93.5% in the overall cohort. These findings

suggest that the treatment duration may be associated with

therapeutic efficacy. Preliminary results indicated that the

adequate ≥4-cycle long regimen of rh-endostatin may be associated

with more significant survival gain. However, the safety of

combination therapy with rh-endostatin in full cycles still

deserves to be explored.

In addition to short-term efficacy assessment, it is

also important to assess the long-term survival of patients. The

median PFS time of patients treated with rh-endostatin combined

with sintilimab and chemotherapy was 8.30 months (95% CI,

3.442–13.158 months), and the median OS time reached 23.07 months.

In the ORIENT-15 study, the PFS and OS of the treatment modality

involving sintilimab combined with chemotherapy were found to be

7.2 and 16.7 months, respectively. It was observed that

rh-endostatin-combined treatment tended to extend PFS and OS.

However, as the present results were from a retrospective study, a

head-to-head comparison could not be conducted. Therefore, further

prospective large-scale clinical trials are still needed for

confirmation.

In terms of safety, the incidence of at least one

TRAE associated with any level of treatment (sintilimab, placebo,

cisplatin, paclitaxel or 5-fluorouracil) in the ORIENT-15 study was

98% (321/327). The incidence of TRAEs of rh-endostatin combined

with sintilimab and chemotherapy in the present study was 77.4%

(24/31), while the incidence of all adverse reactions was lower

than that in the ORIENT-15 study. Anemia, thrombocytopenia and

neutropenia were the most common AEs. However, the majority of

these events were mild to moderate, with severe AEs being rare. The

incidence of grade ≥3 AEs was 35.5% (11/31). In the ORIENT-15

study, the incidence of grade ≥3 TRAEs was 59.9% (196/327) in the

sintilimab chemotherapy group. By contrast, the present study

exhibited a significant decrease. The reduced incidence of these

AEs may be associated with the lower dose of paclitaxel used in the

present study. The chemotherapy regimen used in the present study

had a dose of 135 mg/m2 of paclitaxel liposome, which is

in the low-dose range of paclitaxel liposome (135–175

mg/m2) (38), and the

combined application of rh-endostatin can reduce the chemotherapy

dose, which is conducive to the reduction of AEs of chemotherapy.

The present data suggest that the addition of rh-endostatin

treatment to sintilimab combination chemotherapy is beneficial on

trend, both in terms of efficacy and safety, and that this can also

lower the chemotherapy dose and reduce the incidence of toxic side

effects; however, this needs to be further confirmed by prospective

clinical trials with large samples.

In the subgroup analysis, there were no significant

differences in PFS across subgroups based on age, sex, stage, PD-L1

TPS, ECOG PS or smoking status. This suggests that the response to

treatment was similar across different subgroups, and the subgroup

characteristics studied (age, sex, stage, PD-L1 TPS, ECOG PS and

smoking status) are not key factors influencing treatment efficacy.

Therefore, the treatment strategy exhibited broad effectiveness

across different patient populations.

The present study also had certain limitations.

Firstly, this investigation was a small sample size, single-center,

retrospective analysis. With a sample size of 31 patients and the

study being conducted solely at one institution, it is highly

susceptible to the influence of random factors. This may

potentially compromise the reliability and generalizability of the

research findings. Secondly, the median follow-up duration in the

present study was 13.067 months (95% CI, 10.267–15.866 months). The

relatively short follow-up period may not be adequate to capture a

sufficient number of target events, such as mortality and

recurrence. This can introduce inaccuracies in the analysis of

survival rates and treatment efficacy. Furthermore, short-term

follow-up may impede the accurate assessment of safety. For

instance, immune-related AEs (irAEs) are prevalent adverse

reactions among patients with cancer undergoing ICI therapy. irAEs

are characterized by latency and chronic persistence. Short-term

follow-up may fail to detect these persistent or progressively

deteriorating conditions. Additionally, the symptoms of irAEs are

often non-specific and can be easily confounded with those of other

common diseases or adverse reactions induced by treatment. As a

result, short-term follow-up may overlook certain subtle symptoms,

potentially leading to misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis. This could

lead to an underestimation of the incidence of AEs in the

statistical data.

In future studies, the following adjustments can be

made to address the aforementioned limitations. Firstly, a

prospective randomized controlled clinical trial could be set up to

compare the clinical efficacy of rh-endostatin combined with

sintilimab and chemotherapy against that of sintilimab combined

with chemotherapy. Secondly, the follow-up time could be extended.

The optimal follow-up time should be as long as 2 years, or even

longer if possible. Thirdly, individualized monitoring programs

could be added. Monitoring programs can be developed based on

patients' underlying diseases and their previous adverse reaction

histories. irAEs often involve multiple organ systems, and thus,

timely and comprehensive assessments are crucial for the early

detection of irAEs.

It is therefore necessary to conduct larger sample

size, multicenter, long-term, randomized, controlled clinical

trials to further validate the efficacy and safety of rh-endostatin

in combination with sintilimab and chemotherapy for the first-line

treatment of locally advanced or metastatic ESCC, and to confirm

its long-term effectiveness and toxicity.

In conclusion, rh-endostatin combined with

sintilimab and chemotherapy has a positive efficacy and safety in

the first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic ESCC,

suggesting that this regimen may be a potential treatment option

for patients with advanced ESCC. Further randomized controlled

trials are needed to study the efficacy and safety of rh-endostatin

in combination with sintilimab and chemotherapy for advanced

ESCC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of

Jiangsu Province Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no.

2024YZRKXJJ20), the National Natural Science Foundation of China

(grant no. 82073164), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing,

China (grant no. CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0914) and the Qijiang District

Science and Technology Plan Project (grant no. 2024082).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SC and LF provided materials and contributed to the

study conception and design. XS was responsible for writing the

draft manuscript and conducting the analysis. YC and TW performed

data analysis and interpretation. PL and RW contributed to the

acquisition of data. LL participated in data analysis and study

design. SC and LF confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval was granted by the First Affiliated

Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, China; approval

no. 2024-SR-415). Written informed consent was gathered from the

participants prior to initiation of the study.

Patient consent for publication

In the present study, the patient, parent, guardian

or next of kin as appropriate provided written informed consent for

the publication of any associated data and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

GBD 2017 Oesophageal Cancer Collaborators,

. The global, regional, and national burden of oesophageal cancer

and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories,

1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease

Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5:582–597. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Medical Affairs Bureau of the National

Health and Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, .

Esophageal cancer diagnosis and treatment guidelines (2022

edition). Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 21:1247–1268. 2022.(In

Chinese).

|

|

3

|

Sasaki Y and Kato K: Chemoradiotherapy for

esophageal squamous cell cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 46:805–810.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Watanabe M, Otake R, Kozuki R, Toihata T,

Takahashi K, Okamura A and Imamura Y: Recent progress in

multidisciplinary treatment for patients with esophageal cancer.

Surg Today. 50:12–20. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sun JM, Shen L, Shah MA, Enzinger P,

Adenis A, Doi T, Kojima T, Metges JP, Li Z, Kim SB, et al:

Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for

first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590):

A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet.

398:759–771. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Doki Y, Ajani JA, Kato K, Xu J, Wyrwicz L,

Motoyama S, Ogata T, Kawakami H, Hsu CH, Adenis A, et al: Nivolumab

combination therapy in advanced esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma.

N Engl J Med. 386:449–462. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Song Y, Zhang B, Xin D, Kou X, Tan Z,

Zhang S, Sun M, Zhou J, Fan M, Zhang M, et al: First-line

serplulimab or placebo plus chemotherapy in PD-L1-positive

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A randomized, double-blind

phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 29:473–482. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xu J, Kato K, Raymond E, Hubner RA, Shu Y,

Pan Y, Park SR, Ping L, Jiang Y, Zhang J, et al: Tislelizumab plus

chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy as first-line

treatment for advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell

carcinoma (RATIONALE-306): A global, randomised,

placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 24:483–495. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Luo H, Lu J, Bai Y, Mao T, Wang J, Fan Q,

Zhang Y, Zhao K, Chen Z, Gao S, et al: Effect of camrelizumab vs

placebo added to chemotherapy on survival and progression-free

survival in patients with advanced or metastatic esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma: The ESCORT-1st Randomized clinical trial.

JAMA. 326:916–925. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hoy SM: Sintilimab: First global approval.

Drugs. 79:341–346. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lu Y, Liao L, Du K, Mo J, Zou X, Liang J,

Chen J, Tang W, Su L, Wu J, et al: Clinical activity and safety of

sintilimab, bevacizumab, and TMZ in patients with recurrent

glioblastoma. BMC Cancer. 24:1332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li F, Zhang DB, Ma Y, Song Y and Duan XL:

Effects of combined sintilimab and chemotherapy on progression-free

survival and overall survival in osteosarcoma patients with

metastasis. Pak J Med Sci. 40:648–651. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou SQ, Wan P, Zhang S, Ren Y, Li HT and

Ke QH: Programmed cell death 1 inhibitor sintilimab plus concurrent

chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

World J Clin Oncol. 15:859–866. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lu Z, Wang J, Shu Y, Liu L, Kong L, Yang

L, Wang B, Sun G, Ji Y, Cao G, et al: Sintilimab versus placebo in

combination with chemotherapy as first line treatment for locally

advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma

(ORIENT-15): Multicentre, randomised, double blind, phase 3 trial.

BMJ. 377:e0687142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ohm JE, Gabrilovich DI, Sempowski GD,

Kisseleva E, Parman KS, Nadaf S and Carbone DP: VEGF inhibits

T-cell development and may contribute to tumor-induced immune

suppression. Blood. 101:4878–4886. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hu H, Chen Y, Tan S, Wu S, Huang Y, Fu S,

Luo F and He J: The research Progress of antiangiogenic therapy,

immune therapy and tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol.

13:8028462022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sun Y, Wang JW, Liu YY, Yu QT, Zhang YP,

Li K, Xu LY, Luo SX, Qin FZ, Chen ZT, et al: Long-term results of a

randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled phase III trial:

Endostar (rhendostatin) versus placebo in combination with

vinorelbine and cisplatin in advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

Thorac Cancer. 4:440–448. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pu X, Wang Q, Liu L, Chen B, Li K, Zhou Y,

Sheng Z, Liu P, Tang Y, Xu L, et al: Rh-endostatin plus

camrelizumab and chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced

non-small cell lung cancer: A multicenter retrospective study.

Cancer Med. 12:7724–7733. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Huang H, Zhong P, Zhu X, Fu S, Li S, Peng

S, Liu Y, Lu Z and Chen L: Immunotherapy combined with

rh-endostatin improved clinical outcomes over immunotherapy plus

chemotherapy for second-line treatment of advanced NSCLC. Front

Oncol. 13:11372242023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen J, Yao Q, Huang M, Wang B, Zhang J,

Wang T, Ming Y, Zhou X, Jia Q, Huan Y, et al: A randomized Phase

III trial of neoadjuvant recombinant human endostatin, docetaxel

and epirubicin as first-line therapy for patients with breast

cancer (CBCRT01). Int J Cancer. 142:2130–2138. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang X, Jin F, Jiang S, Cao J, Meng Y, Xu

Y, ChunmengWan g, Chen Y, Yang H, Kong Y, et al: Rh-endostatin

combined with chemotherapy in patients with advanced or recurrent

mucosal melanoma: retrospective analysis of real-world data. Invest

New Drugs. 40:453–460. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tsuchida Y and Therasse P: Response

evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST): New guidelines. Med

Pediatr Oncol. 37:1–3. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chinese Anti-Cancer Association, . Chinese

expert consensus on PD-L1 immunohistochemical detection criteria

for non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Lung Cancer. 23:733–740.

2020.

|

|

24

|

Mischel AM and Rosielle DA: Eastern

Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status #434. J Palliat Med.

25:508–510. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

National Cancer Institute, . Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE). https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdfFebruary

6–2024

|

|

26

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bureau of Medical Administration and

National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, .

Standardization for diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer

(2022 edition). Chin J Dig Surg. 21:1247–1268. 2022.(In

Chinese).

|

|

28

|

Wang B, Zhao Q, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Zheng Z,

Liu S, Meng L, Xin Y and Jiang X: Targeting hypoxia in the tumor

microenvironment: A potential strategy to improve cancer

immunotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Khan KA and Kerbel RS: Improving

immunotherapy outcomes with anti-angiogenic treatments and vice

versa. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 15:310–324. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Baas P, Scherpereel A, Nowak AK, Fujimoto

N, Peters S, Tsao AS, Mansfield AS, Popat S, Jahan T, Antonia S, et

al: First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in unresectable malignant

pleural mesothelioma (CheckMate 743): A multicentre, randomised,

open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 397:375–386. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda

DG and Jain RK: Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using

antiangiogenics: Opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

15:325–340. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Tian L, Goldstein A, Wang H, Ching Lo H,

Sun Kim I, Welte T, Sheng K, Dobrolecki LE, Zhang X, Putluri N, et

al: Mutual regulation of tumour vessel normalization and

immunostimulatory reprogramming. Nature. 544:250–254. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Schmidt EV: Developing combination

strategies using PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors to treat cancer. Semin

Immunopathol. 41:21–30. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Voron T, Colussi O, Marcheteau E, Pernot

S, Nizard M, Pointet AL, Latreche S, Bergaya S, Benhamouda N,

Tanchot C, et al: VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory

checkpoints on CD8(+) T cells in tumors. J Exp Med. 212:139–148.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Allen E, Jabouille A, Rivera LB,

Lodewijckx I, Missiaen R, Steri V, Feyen K, Tawney J, Hanahan D,

Michael IP and Bergers G: Combined antiangiogenic and anti-PD-L1

therapy stimulates tumor immunity through HEV formation. Sci Transl

Med. 9:eaak96792017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Manning EA, Ullman JG, Leatherman JM,

Asquith JM, Hansen TR, Armstrong TD, Hicklin DJ, Jaffee EM and

Emens LA: A vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 inhibitor

enhances antitumor immunity through an immune-based mechanism. Clin

Cancer Res. 13:3951–3959. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Fuming Qiu, Fan J, Shao M, Yao J, Zhao L,

Zhu L, Li B, Fu Y, Li L, Yang Y, et al: Efficacy of two - and

three-cycle neoadjuvant sinadilizumab plus platinum-based

double-agent chemotherapy in patients with resectable non-small

cell lung cancer (neoSCORE): A randomized, single-center, two-arm

Phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 40:8500. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Huizing MT, Keung AC, Rosing H, van der

Kuij V, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, Mandjes IM, Dubbelman AC, Pinedo HM

and Beijnen JH: Pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel and metabolites in a

randomized comparative study in platinum-pretreated ovarian cancer

patients. J Clin Oncol. 11:2127–2135. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|