Introduction

Anal cancer is a rare but serious malignancy

accounting for ~3% of all gastrointestinal types of cancer

(1). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

is the most common type of anal cancer and is suspected to be

linked to inflammatory processes secondary to human papilloma virus

(HPV), particularly subtypes 16 and 18 (2). A third of anal cancers are

asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms, while the

remaining cases will present with anal bleeding or pain (3). Anal cancer treatment is

multi-disciplinary and stage dependent, consisting of combined

chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and/or surgical resection (2). The 5-year overall survival of

localized disease is ~78%, and 18% in metastatic disease, with the

median survival of metastatic disease being 12 months (4). In anal SCC, distant metastasis is

relatively uncommon, with the liver being the most common area for

metastatic spread (4). Distant

metastasis of anal SCC has been reported in 5–8% of cases at

diagnosis, with 10–20% after curative local treatment (5). An even more uncommon occurrence of

anal SCC is metastatic spread to the brain; to the best of our

knowledge, only 9 previous cases have reported cerebral metastatic

disease after an initial anal SCC diagnosis (6–13). The

current study presents the case of a 56-year-old female with anal

canal SCC who later developed cerebral metastasis, adding to the

limited literature of this rare phenomenon.

Case report

The current study presents the case of a now

56-year-old right-handed Caucasian female who initially presented

with anal SCC (T3 N1c Mx) and later went on to develop an isolated

cerebral metastasis. In September 2017, the patient presented to a

rural hospital in South Australia with a non-tender lump in the

right pubic area with no reported systemic symptoms. A fine-needle

aspiration under ultrasound guidance demonstrated malignant cells,

in keeping with poorly differentiated SCC that was reactive for

p16, a tumour marker highly associated with HPV (14). A computed tomography (CT) scan of

the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated no primary tumour. The patient

underwent pubic lumpectomy in February of 2017 and was subsequently

offered combination CRT but was lost to follow-up due to scheduling

difficulties.

In September 2022, the patient presented to the

Emergency Department of a local rural hospital with sharp anal pain

and obstipation, in which a CT scan demonstrated a perforated

rectal tumour above the anal verge. The perforation was repaired,

and the tumour was removed laparoscopically via loop colostomy in

November 2022 following a multi-disciplinary team meeting. The

subsequent pathology report confirmed the presence of invasive

basaloid SCC with focal necrosis, in keeping with the initial

primary diagnosis in 2017. The tumour expressed p40 positivity,

which indicated SCC origin (15).

Concurrent CRT with mitomycin-C with oral capecitabine was

commenced, and the patient also underwent 54 Gy of targeted

radiation therapy in 27 fractions. The patient was declared in

remission in December of 2023 and shortly thereafter underwent a

reversal of the colostomy the following month.

The patient presented to the Emergency Department in

March 2024 with several weeks of lethargy, disorientation, labile

mood, personality changes and headaches. Physical examination was

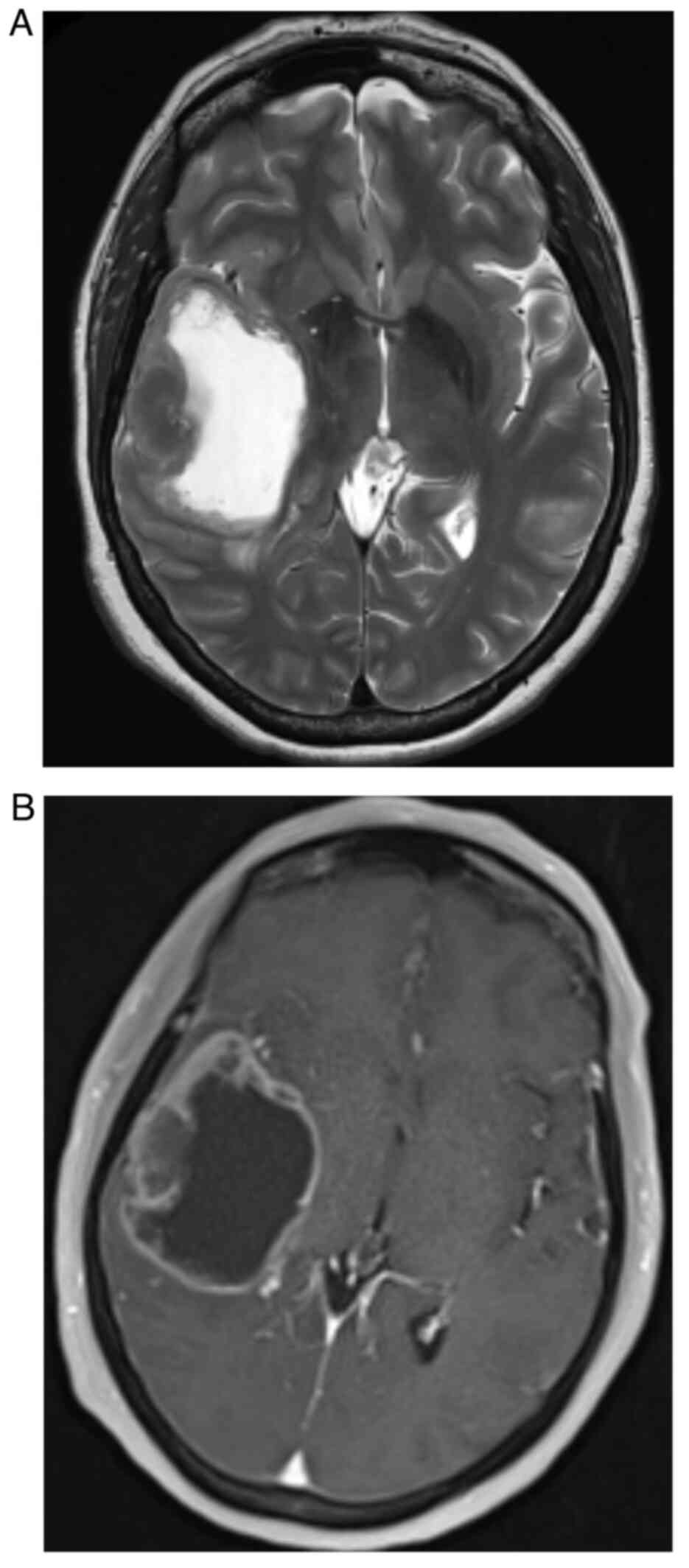

unremarkable on admission. A CT scan demonstrated a 5.2×4.2×4.9 cm

rounded solid and cystic, irregular enhancing mass in the right

frontotemporal region of the brain, in keeping with metastasis

(Fig. 1). There was midline shift

to the left, effacement of the right lateral ventricle and mild

perilesional oedema. The patient was subsequently transferred to

Flinders Medical Centre (Adelaide, Australia), and admitted for

review and treatment under the Neurosurgical Unit.

CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis did not

demonstrate recurrent colorectal malignancy or new nodal or

metastatic disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain

with gadolinium confirmed a large cystic and necrotic solitary

metastatic lesion within the temporal lobe (Fig. 2).

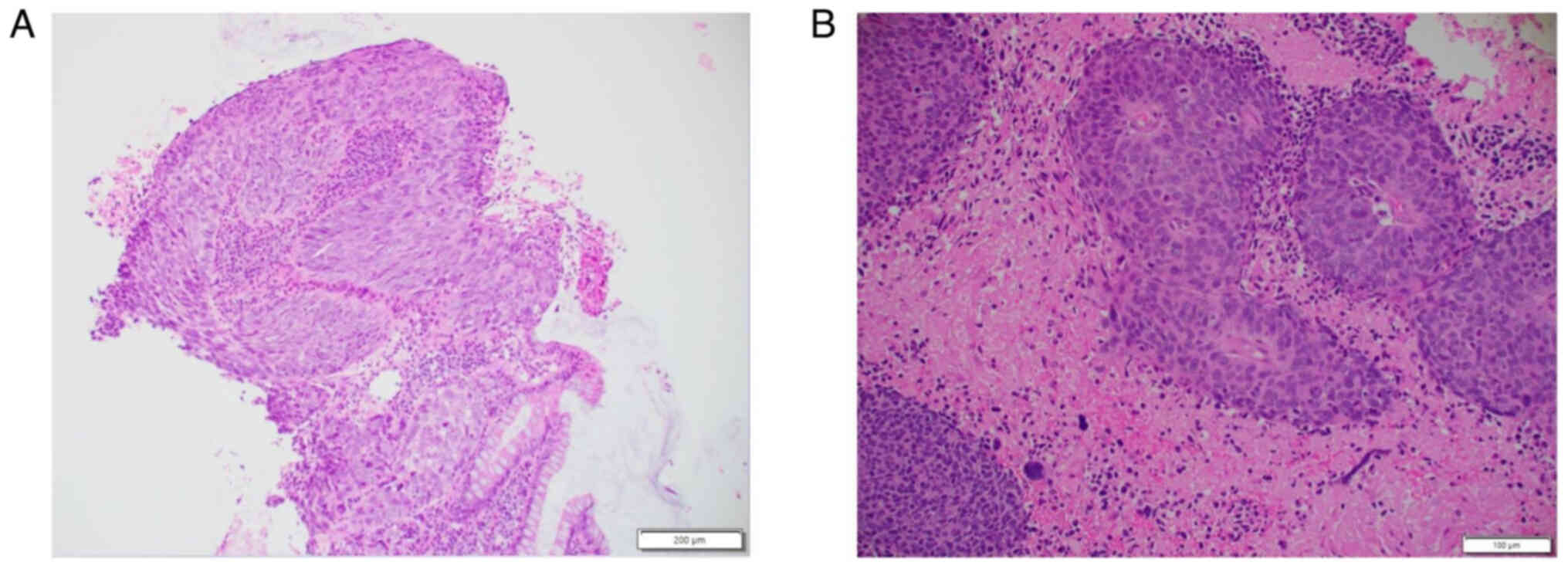

Following counselling and consent, the patient

underwent neuronavigation-guided craniotomy and resection of the

tumour in March of 2024. Histopathological analysis of haematoxylin

and eosin staining confirmed the presence of cells consistent with

sheets and nests of malignant basaloid epithelial cells

demonstrating nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia and marked

pleomorphism, as well as brisk mitotic activity in addition to

focal keratinisation (Fig. 3). A

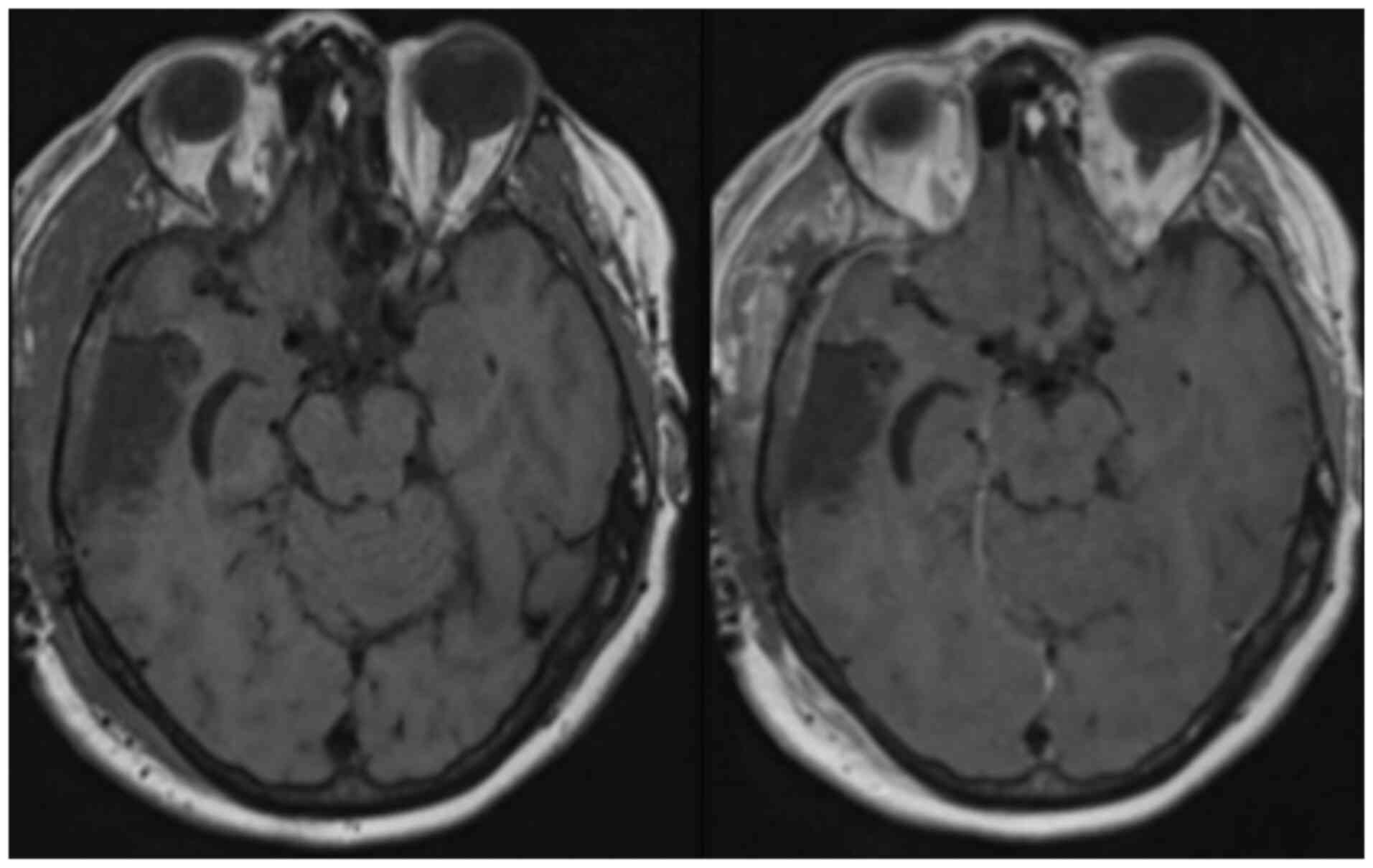

post-operative MRI did not demonstrate any residual tumour

(Fig. 4). The patient had recovered

well post-operatively without any complications and was discharged

home on day 9 post-operatively, with referrals to the original

oncologic team for consideration of further CRT.

The patient attended a follow-up appointment with a

medical oncologist 1 month after discharge, who discussed radiation

therapy. It was considered that systemic chemotherapy would not

have provided any benefit at the time due to the lack of

progression of systemic disease. The patient underwent 30 Gy over

10 fractions of hypofractionated radiotherapy to the cerebral

resection cavity. The patient had repeat abdomen CT and brain MRI

scans (Fig. 4) 4 months

post-operatively, which showed no recurrence of either anal primary

or cerebral metastasis. At a 2- and 5-month neurosurgical review,

no ongoing clinical issues were reported except mild fatigue, and

the patient remained neurologically intact. The patient was

subsequently discharged from the neurosurgical clinic with no

further follow ups.

Discussion

Anal cancer, a rare but deadly malignancy, is

increasingly prevalent in Western countries. SCC is the most common

form of anal cancer, accounting for 80% of cases (1). Primary anal adenocarcinoma comprises

10–20% of anal cancer cases, while anal melanoma and basal cell

carcinoma are exceedingly rare, seen at 1–4 and 0.2%, respectively

(1). Certain risk factors increase

the likelihood of developing anal cancer, such as smoking, HIV and

sexually transmitted diseases such as HPV subtypes 16 and 18. Once

anal cancer has metastasized, it carries a poor prognosis and is

often fatal (4). Other risk factors

include males who engage in sexual activity with males, receptive

anal intercourse, history of other sexually transmitted diseases,

use of immunosuppressive medication and women with a history of

cervical cancer (16). The

incidence of anal cancer has increased in Western countries over

the last few decades at ~2.2% per year, likely due to changes in

sexual behaviour leading to sexually transmitted infections.

Individuals who have undergone organ transplantation are also at an

increased risk for anal cancer due to the necessary

immunosuppressive medication regimen, allowing cancer cells to

proliferate without mounting a significant immune response

(16). Combined CRT, commonly

utilising 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in addition to cisplatin or

mitomycin-C, is the standard treatment for anal SCC, but there is

no current consensus for treating metastatic disease (4).

To date, 9 previous cases of cerebral metastasis

from anal SCC have been documented in the literature, with ages

ranging from 44–69 years (see Table

I) (6–13). Among these cases, 5 patients were

female, 3 were male and the sex of 1 patient was not disclosed.

Treatment of metastatic brain lesions varied based on the location

and extent of the metastasis, the patient's preferences, and their

functional status at diagnosis. None of the reported cases

initially presented with known metastatic cerebral disease and 3

cases presented with no evidence of metastasis at all (6,11,12).

The most common locations for distant metastasis were the local

lymph nodes, the liver or both, as observed in 6 patients (7–10,13).

Only 2 cases initially presented with lung metastasis at diagnosis

(10,13). There was no discernible pattern when

comparing the natural history of these cases. The first documented

case of cerebral metastatic spread was secondary to anal

cloacogenic carcinoma in 1967. No further information was reported

regarding patient demographics, staging, treatment or outcome for

this patient (12).

| Table I.Previously reported cases of anal

squamous cell carcinoma. |

Table I.

Previously reported cases of anal

squamous cell carcinoma.

| First author,

year | Age, years | Sex | Histopathology | Location of distant

metastasis at time of diagnosis | Initial

treatment | Time from diagnosis

to cerebral metastasis | Location of cerebral

metastasis and subsequent treatment | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Klotz et al,

1967 | Information not

provided. | Information not

provided. | Transitional

cloacogenic carcinoma (subtype of squamous cell carcinoma) | Nil | Information not

provided. | Information not

provided. | Information not

provided. | Information not

provided. | (12) |

| Davidson et

al, 1991 | 53 | F | Basaloid carcinoma

(subtype of SCC) | Nil | Abdominoperineal

surgery. | 8 years | Cerebellum. Surgical

excision and palliative radiotherapy. | Succumbed to disease

3 months after diagnosis of cerebral metastasis. | (11) |

| Rughani et al,

2011 | 63 | F | Poorly differentiated

SCC | Inguinal

lymphadenopathy and liver lesion. | 17 doses of pelvic

radiation with oral chemotherapy (capecitabine 1500 mg, twice

daily). | Unclear | Right parietal lobe

lesion. Elective craniotomy and whole brain radiation. | Neurological symptoms

unchanged at 1-month post-operative follow up. Patient succumbed to

disease 14 weeks post diagnosis of cerebral metastasis. | (10) |

| Gassman et al,

2012 | 67 | M | Invasive poorly

differentiated SCC. | Isolated hepatic

metastasis. | 5-FU, cisplatin +

50.4 Gy radiation, followed by further cisplatin therapy. | 6 months | Intracranial mass

with involvement of the sphenoid and temporal bones, in addition to

left orbit, CNII and rectus muscle. Stereotactic radiotherapy

planned for newly found brain metastasis. | Patient experienced

recurrence of primary disease, treated with abdominoperineal and

liver resection for recurrence. Patient succumbed to disease prior

to commencement of stereotactic radiotherapy for brain

metastasis. | (9) |

| Hernando-Hubero

et al, 2014 | 69 | M | Stage IV basaloid

undifferentiated carcinoma. | Mesorectal

lymphadenopathy, multiple pulmonary and liver metastases. | Cisplatin +

5-FU | 14 months | Right parietal,

left rolandic, cortical and subcortical, cerebellar and frontal

lobes, with tonsillar herniation. Steroid therapy + 30 Gy. | Patient succumbed

to disease 12 weeks after brain metastasis discovered. | (13) |

| Ogawa et al,

2017 | 60′s | F | Poorly

differentiated SCC, positive for CK5/6 and 34βE12, and negative for

CDX2. Negative for HPV and p16. | Liver and internal

iliac lymph node. | Two cycles of 5-FU

700 mg/m2 and cisplatin 70 mg/m2 + 54 Gy/27

fractions of radiotherapy. | 7 months | Metastatic lesions

in occipital lobe (19 Gy) and cerebellum (21 Gy). Patient then

underwent surgical excision of occipital tumour that had grown,

while cerebellar lesion showed full response to treatment. A

fluoropyrimidine anticancer agent was administered + 22 Gy for

progression of liver metastasis. Occipital tumour recurrence

detected, subsequently treated with 22 Gy of radiotherapy.

Recurrence of occipital lesion was treated surgically. | Patient experienced

adverse effects from treatment which included significant anorexia.

After 5 years, treatment was ceased. Out-patient follow up was

scheduled. Longest reported survival of a patient with a distant

cerebral metastasis. | (7) |

| Chihabeddine et

al, 2021 | 44 | F | Poorly

differentiated SCC | Extension into

gluteal soft tissue and involvement of mesorectal nodules,

cutaneous nodules of the sacral region, and bone lesions of greater

trochanter. | Chemotherapy with

capecitabine 825 mg/m2, cisplatin 80 mg/m2 +

radiotherapy total dose of 60 Gy. | A few months | Left parietal lobe

and frontal bone with involvement of soft tissue of scalp. Total

brain external radiotherapy, total dose of 20 Gy. | Patient succumbed

to disease during treatment. | (8) |

| Chihabeddine et

al, 2021 | 60 | M | Moderately

differentiated SCC with positive anti p40. Negative for programmed

death ligand 1 and microsatellite instability. | Secondary lung

localization, external iliac and inguinal lymphadenopathy. Lesions

seen in sacrum, pubis, and coccyx. | Palliative

chemotherapy docetaxel, cisplatin, FU + granulocyte

colony-stimulating factor, docetaxel, and 5-FU for 12 weeks.

Treatment ceased early due to persistent neutropenia. Second-line

treatment: 60 Gy, capecitabine and cisplatin. | A few months | Multiple metastatic

lesions above and below the tentorium Total brain radiotherapy

planned. | Patient succumbed

to disease prior to starting treatment. | (8) |

| Malla et al,

2022 | 54 | F | Poorly

differentiated SCC with ki-67 at 80%. Positive for p63 and

pancytokeratin. p16 also strongly positive. | Nil | 5-FU and

mitomycin | 3 months | Right frontal mass

with significant oedema. Surgical resection and g knife

radiosurgery. Whole brain radiotherapy with 3,000 Gy and intensity

modulated radiation therapy. | Patient experienced

recurrence 8 months later and had another round of g knife

radiosurgery. Following another recurrence of a brain lesion 7

months later, patient opted for hospice care. | (6) |

In the present study, the patient was diagnosed with

anal malignancy at the end of 2017. After being lost to follow-up

following their initial presentation, the patient underwent

appropriate treatment with CRT in 2022. However, despite undergoing

appropriate treatment for anal SCC, the patient was diagnosed with

a cerebral metastatic lesion ~6.5 years following initial diagnosis

and 6 months after achieving remission. The shortest reported

interval between primary and metastatic diagnosis was 3 months

(6) and the longest was 8 years

(11). Malla et al (6) reported a patient to have metastatic

spread to the frontal lobe who underwent surgical resection of the

brain tumour plus γ knife radiosurgery before experiencing a

recurrence of the brain lesion 8 months later and was subsequently

treated with whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT). Despite

receiving WBRT, another cerebral recurrence was discovered 7 months

later. The patient then opted for hospice care instead of further

treatment.

The longest period between primary diagnosis and

metastatic discovery was reported by Davidson and Yong (11) in 1991. A 61-year-old female patient

with anal SCC presented with neurological symptoms 8 years after

undergoing surgical resection of the primary malignancy. The

patient subsequently underwent surgical resection and radiotherapy

for the brain lesion. This was the only reported case with surgical

resection of the primary malignancy, similar to the present

case.

Of the 9 reported cases, 2 patients had succumbed to

their disease before commencing treatment (9,10).

Both patients were found to have multiple cerebral metastases in

different areas of the brain several months after their initial

diagnosis of anal cancer. Both patients passed away before

beginning the planned radiotherapy. In total, 3 patients succumbed

to the disease either during the treatment of the brain metastasis

or shortly after completing secondary treatment (8,10,13).

All cerebral metastases were treated or planned for treatment with

surgical resection, radiation therapy or a combination of the two.

No case report documented the use of chemotherapy in treating

cerebral metastasis. In a review by Sclafani et al (17) in 2019, treatment protocols in 8

reports of advanced anal SCC with liver and lung metastasis were

compared and it was found that although there is a lack of

high-level evidence to guide the treatment of advanced anal SCC, a

multi-disciplinary approach to treating metastatic disease was

considered a superior approach. It was concluded that aggressive

management with various treatment modalities, including surgery,

radiotherapy and radiofrequency ablation, can offer more extended

disease control compared with systemic chemotherapy alone. However,

given the rarity of the disease and lack of supportive evidence,

further randomised control trials are urgently necessary to develop

a substantial treatment regime tailored to individualised

treatments.

A case reported in 2017 by Ogawa et al

(7) documented the longest survival

period from diagnosis of primary malignancy to death, which was 5

years. The case involved a female patient in her 60s who was

initially diagnosed with poorly differentiated SCC, which was

positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5, 6 and 34bE12, and negative for

CDX2. CK5 and 6 are understood to be indicative of squamous cell

origin, ruling out adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine origins

(18). At the initial presentation,

the patient also had liver and internal iliac lymph node

involvement. Initial treatment included CRT with 5-FU and cisplatin

with 54 Gy over 27 fractions of radiotherapy. However, 7 months

after initial diagnosis, metastatic brain lesions were found in the

occipital lobe and cerebellum. The patient received 19 Gy of

radiation to the occipital lesion and 21 Gy to the cerebellar

lesion. Over the next 4 years, the patient experienced multiple

recurrences of the primary cancer, as well as further cerebral

metastasis. Despite receiving various treatments, including

radiation, surgical resection and chemotherapeutics, the patient

experienced significant adverse events, including significant

anorexia and ceased further treatment after 5 years (7).

The present patient's primary SCC displayed strong,

diffuse cytoplasmic and nuclear labelling for p16. The only other

documented case of p16 positivity was reported by Malla et

al (6). p16 upregulation was

previously considered an indicator of HPV-induced transformation to

anal carcinoma; however, it has since been discovered to occur

independent of HPV infection. HPV-negative tumours more frequently

correlate with TP53 mutations compared with p16 upregulation

(19), while p16 upregulation can

occur independent of HPV via the p16/ retinoblastoma protein (Rb)

pathway. Specifically, if p16 expression is lost, unregulated

CDK4/6 expression leads to hyperphosphorylated Rb, ultimately

leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation (20). p16 has also been used as a marker of

malignancy in cervical SCC. It was found that the intensity with

which p16 stained immunohistochemically has a direct relationship

to the severity of cervical lesion or disease (21).

HPV and p16 should only be considered in tandem; p16

independently is not considered to be a reliable marker of

HPV-induced transformation as p16 can be positive for malignancies

unrelated to HPV (22). Although

not an exhaustive list, p16 overexpression is seen in endometrial

carcinoma (23) and mesothelioma

(24). The presence of p16

positivity without HPV in anal SCC tends to lead to a poorer

prognosis due to a reduced response to treatment (14). The presence of both HPV and p16 is

linked to an increased response to treatment, whereas HPV and p16

negative status records the lowest rate of response to treatment

and the worst prognosis overall (14). A meta-analysis in 2017 concluded

that patients with HPV+/p16+ status anal SCC had improved outcomes

than those with HPV-/p16+ or HPV-/p16-status. Additionally, it was

suggested that an individual's HPV and p16 status can be used for

therapeutic guidance and of prognostic utility in anal SCC

(25). The American Society of

Colon and Rectal Cancer Surgeons guidelines suggests that there may

be benefit in vaccination against HPV to prevent anal cancer

altogether (26). The present

patient did not have any risk factors for anal cancer other than

smoking. At the time of initial diagnosis of anal SCC, the patient

had been a smoker for a couple of decades, although had since

ceased smoking.

Patients who complete CRT may benefit from

assessment of clinical response to the primary malignancy at 6

months with a digital rectal exam, palpation of inguinal lymph

nodes, and a yearly CT/positron emission tomography scan for up to

3 years (27,28). However, no significant data supports

investigating distant metastasis during the surveillance period

(27). The benefits of full-body

scanning in patients who present with evidence of liver and/or lung

metastasis at the initial diagnosis of an anal primary should be

considered. This does, however, carry implications. For example,

the cost-effectiveness of a full-body scan, as well as the

availability of such scans. Furthermore, a false positive can

inflict unnecessary distress on a patient and their family members.

Other logistical barriers also exist, including insurance

limitations and transport to such facilities. Further research

aiming to optimise surveillance may potentially benefit

gastrointestinal malignancies altogether.

Anal SCC with metastatic spread to the brain

presents a poor prognosis as survival from the time of discovery of

cerebral lesions to death is a short few months to years (5). Distant spread to the brain follows no

understood pattern concerning either location, quantity or

timeline. Additionally, those who present without metastasis

initially do not necessarily carry an improved prognosis when

compared with those who present with metastasis. The case report by

Davidson and Young was the first to report that their patient had

been in remission of their primary anal SCC at the time of

presentation with cerebral disease (11). This implies that at the time of

declaring remission, there is a likelihood that microscopic

malignant cells will linger undetected at the time of a follow-up

scan. Colorectal cancer may spread to the liver via the portal

circulation, which can lead to hepatic metastasis while increasing

the risk of spread to the lungs as well. From here, a highway is

created for dissemination of metastases to the central nervous

system (29).

Additionally, a brain lesion may then be missed in

the workup and surveillance for anal cancer as the brain is not

routinely imaged unless otherwise clinically indicated (30). It may be beneficial to consider a CT

of the brain with contrast in patients with initial metastasis in

the liver and/or lungs to rule out cerebral metastasis at

presentation confidently.

Furthermore, utilisation of a chemotherapeutic agent

that can effectively cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) could be

considered, to ensure that spread to the brain is minimised or

prevented in patients with known existing metastatic disease. For

example, an agent such as temozolomide, which has historically been

used in treating gliomas and can penetrate the BBB, may be

considered in preventing cerebral metastasis (31). A review of 21 clinical trials in

2014 investigated the efficacy of temozolomide in treating cerebral

metastases from various solid tumours which included non-small cell

lung cancer and malignant melanoma. It was noted that trials with

temozolomide-monotherapy had modest response, while metastases

treated with combination chemotherapy with temozolomide and

radiation therapy saw an even greater response to treatment

compared with monotherapy alone (32).

Of the previous cases reported, no two primary anal

malignancies nor cerebral metastasis were treated identically.

Primary treatment consisted of either surgery, chemotherapy,

radiation or a combination of the three. This area of

gastrointestinal malignancies would benefit from further research

in standardising primary treatment to decrease the risk of

recurrence and metastatic spread and develop treatment protocols

for advanced disease and surveillance protocols. Whether

investigating cerebral lesions before declaring remission would be

of benefit warrants further study. Finally, testing for tumour

markers such as p16 may be considered when planning treatment and

to further understand the disease course. In conclusion, patients

at risk for anal cancer should take steps to protect their health

by mitigating risks and undergoing regular screening to detect any

potential problems early.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Eri Sakata for

her assistance with the translation of Japanese to English for

reference 7.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are not

publicly available due to patient confidentiality.

Author's contributions

EAP, VMT and ARM made substantial contributions to

the conception/design of the work. PSM, EQ and CT were responsible

for the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of medical

information for the work, advised on patient treatment, obtained

CT/MRI images and pathology images. All authors contributed to

drafting the work or revising it critically for important

intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. EAP, VMT, ARM, PSM, EQ and CT confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Southern

Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics (SAC HREC) Committee

(November 12 2024; Adelaide, Australia). Ethics and Governance

compliance within the network is regulated by the Southern Adelaide

Local Health Network Research Hub through the SAC HREC. Flinders

Medical Centre is part of the same network.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided oral (recorded) informed

consent for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Young AN, Jacob E, Willauer P, Smucker L,

Monzon R and Oceguera L: Anal Cancer. Surg Clin North Am.

100:629–634. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Babiker HM, Kashyap S, Mehta SR, Lekkala

MR and Cagir B: Anal Cancer. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Morton M, Melnitchouk N and Bleday R:

Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Curr Probl Cancer.

42:486–492. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gnanajothy R, Warren GW, Okun S and

Peterson LL: A combined modality therapeutic approach to metastatic

anal squamous cell carcinoma with systemic chemotherapy and local

therapy to sites of disease: Case report and review of literature.

J Gastrointest Oncol. 7:E58–E63. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sawai K, Goi T, Tagai N, Kurebayashi H,

Morikawa M, Koneri K, Tamaki M, Murakami M, Hirono Y and Maeda H:

Stage IV anal canal squamous cell carcinoma with Long-term

survival: A case report. Surg Case Rep. 8:1192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Malla M, Hatoum H and George S: Brain

metastases in anal squamous cell carcinoma: Case report and review

of the literature. J Clin Images Med Case Rep. 32022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ogawa S, Fujishiro H, Fujiwara A, Tsukano

K, Kotani S, Yamanouchi S, Kusunoki R, Aimi M, Miyaoka Y, Kohge N

and Onuma H: A case of Long-term survival in stage IV squamous cell

carcinoma of the anal canal with multidisciplinary treatment. Nihon

Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 114:1987–1995, (In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chihabeddine M, Naim A, Habi J, Kassimi M,

Mahi M and Kouhen F: Anal cancer with atypical brain and cranial

bones metastasis: About 2 cases and literature review. Case Rep

Oncol. 14:778–783. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gassman AA, Fernando E, Holmes CJ, Kapur U

and Eberhardt JM: Development of cerebral metastasis after medical

and surgical treatment of anal squamous cell carcinoma. Case Rep

Oncol Med. 2012:9121782012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rughani AI, Lin C, Tranmer BI and Wilson

JT: Anal cancer with cerebral metastasis: A case report. J

Neurooncol. 101:141–143. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Davidson NG and Yong PP: Brain metastasis

from basaloid carcinoma of the anal canal 8 years after

abdominoperineal resection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 17:227–230.

1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Klotz RG, Pamukcoglu T and Souilliard DH:

Transitional cloacogenic carcinoma of the anal canal.

Clinicopathologic study of three hundred Seventy-three cases.

Cancer. 20:1727–1745. 1967. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hernando-Cubero J, Alonso-Orduña V,

Hernandez-Garcia A, De Miguel AC, Alvarez-Garcia N and Anton-Torres

A: Brain metastasis in basaloid undifferentiated anal carcinoma: A

case report. Oncol Lett. 7:1276–1278. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mai S, Welzel G, Ottstadt M, Lohr F,

Severa S, Prigge ES, Wentzensen N, Trunk MJ, Wenz F, von

Knebel-Doeberitz M and Reuschenbach M: Prognostic relevance of HPV

infection and p16 overexpression in squamous cell anal cancer. Int

J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 93:819–827. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rami S, Han YD, Jang M, Cho MS, Hur H, Min

BS, Lee KY and Kim NK: Efficacy of Immunohistochemical staining in

differentiating a squamous cell carcinoma in poorly differentiated

rectal cancer: Two case reports. Ann Coloproctol. 32:1502016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

van der Zee RP, Richel O, de Vries HJC and

Prins JM: The increasing incidence of anal cancer: Can it be

explained by trends in risk groups? Neth J Med. 71:401–411.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sclafani F, Hesselberg G, Thompson SR,

Truskett P, Haghighi K, Rao S and Goldstein D: Multimodality

treatment of oligometastatic anal squamous cell carcinoma: A case

series and literature review. J Surg Oncol. 119:489–496. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gondal TA, Chaudhary N, Bajwa H, Rauf A,

Le D and Ahmed S: Anal cancer: The past, present and future.

Current Oncol. 30:3232–3250. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Meulendijks D, Tomasoa NB, Dewit L, Smits

PHM, Bakker R, van Velthuysen MLF, Rosenberg EH, Beijnen JH,

Schellens JH and Cats A: HPV-negative squamous cell carcinoma of

the anal canal is unresponsive to standard treatment and frequently

carries disruptive mutations in TP53. Br J Cancer. 112:1358–1366.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rayess H, Wang MB and Srivatsan ES:

Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int J Cancer.

130:1715–1725. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Izadi-Mood N, Asadi K, Shojaei H, Sarmadi

S, Ahmadi SA, Sani S and Chelavi LH: Potential diagnostic value of

P16 expression in premalignant and malignant cervical lesions. J

Res Med Sci. 17:428–433. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Mai S, Welzel G, Ottstadt M, Lohr F,

Severa S, Prigge ES, Wentzensen N, Trunk MJ, Wenz F, von

Knebel-Doeberitz M and Reuschenbach M: Prognostic relevance of HPV

infection and p16 overexpression in squamous cell anal cancer. Int

J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 93:819–827. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yoon G, Koh CW, Yoon N, Kim JY and Kim HS:

Stromal p16 expression is significantly increased in endometrial

carcinoma. Oncotarget. 8:4826–4836. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kettunen E, Savukoski S, Salmenkivi K,

Böhling T, Vanhala E, Kuosma E, Anttila S and Wolff H: CDKN2A copy

number and p16 expression in malignant pleural mesothelioma in

relation to asbestos exposure. BMC Cancer. 19:5072019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sun G, Dong X, Tang X, Qu H, Zhang H and

Zhao E: The prognostic value of HPV combined p16 status in patients

with anal squamous cell carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget.

9:8081–8088. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Stewart DB, Gaertner WB, Glasgow SC,

Herzig DO, Feingold D and Steele SR: The American society of colon

and rectal surgeons clinical practice guidelines for anal squamous

cell cancers (revised 2018). Dis Colon Rectum. 61:755–774. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Adams R: Surveillance of anal canal

cancers. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 26:127–132. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D,

Meadows HM, Cunningham D, Begum R, Adab F, Benstead K, Harte RJ,

Stewart J, Beare S, et al: Best time to assess complete clinical

response after chemoradiotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the

anus (ACT II): A post-hoc analysis of randomised controlled phase 3

trial. Lancet Oncol. 18:347–356. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang Y, Zhong X, He X, Hu Z, Huang H, Chen

J, Chen K, Zhao S, Wei P and Li D: Liver metastasis from colorectal

cancer: Pathogenetic development, immune landscape of the tumour

microenvironment and therapeutic approaches. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

42:1772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J and

Hemminki K: Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci

Rep. 6:297652016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tashima T: Brain cancer chemotherapy

through a delivery system across the Blood-brain barrier into the

brain based on Receptor-mediated transcytosis using monoclonal

antibody conjugates. Biomedicines. 10:15972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhu W: Temozolomide for treatment of brain

metastases: A review of 21 clinical trials. World J Clin Oncol.

5:192013. View Article : Google Scholar

|