Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common

malignancies of the digestive tract and is ranked third for

incidence and second for cancer-related mortality worldwide

(1). It has been reported that 20%

of patients with CRC have metastatic disease at the time of

presentation, and a further 25% who initially present with in

situ tumors develop metastases during follow-up (2). Notably, 5% of metastatic CRCs harbor

alterations in Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2), also

known as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). HER2 is a

known oncogene (3) that can trigger

carcinogenesis via the upregulation of HER2 protein expression,

gene amplification of ERBB2, or point mutations, which occur mainly

in patients with breast or gastric cancer (4).

HER2 positivity is considerably less common in CRC

than in breast or gastric cancer, affecting only ~5% cases overall,

but represents an important focus of research (5). First-line chemotherapeutic agents

currently approved for KRAS/NRAS wild-type (WT) metastatic CRC

include conventional cytotoxic agents such as fluorouracil,

oxaliplatin and irinotecan, vascular endothelial growth factor

inhibitors such as bevacizumab, and epidermal growth factor

receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, including cetuximab and panitumab

(2,6,7).

However, there is no standard treatment for HER2-positive

metastatic CRC. Although several recent studies have found

anti-HER2 therapy to be effective in HER2-positive CRC (8–10), the

evidence is not conclusive enough to warrant the inclusion of

anti-HER2 agents in the relevant diagnostic and treatment

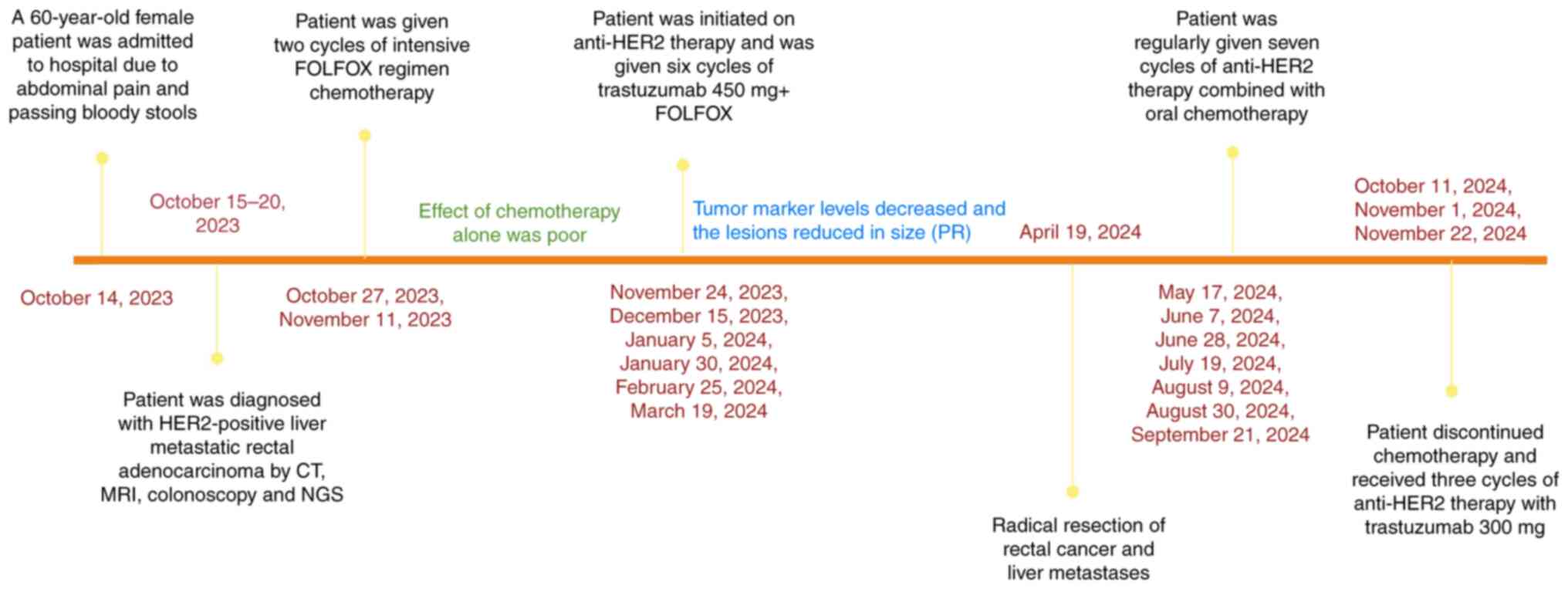

guidelines. The present case report describes a patient who was

diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma and multiple metastases to the

liver in whom next-generation sequencing (NGS) results suggested

positive HER2 expression. As two cycles of an intensive folinic

acid (leucovorin) + fluorouracil + oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) exhibited

poor treatment efficacy, anti-HER2 therapy was introduced. The

clinical findings for this case are described to highlight the

important role of anti-HER2 therapy in HER2-positive CRC and

underscore the importance of further investigating personalized

treatment strategies for this disease.

Case report

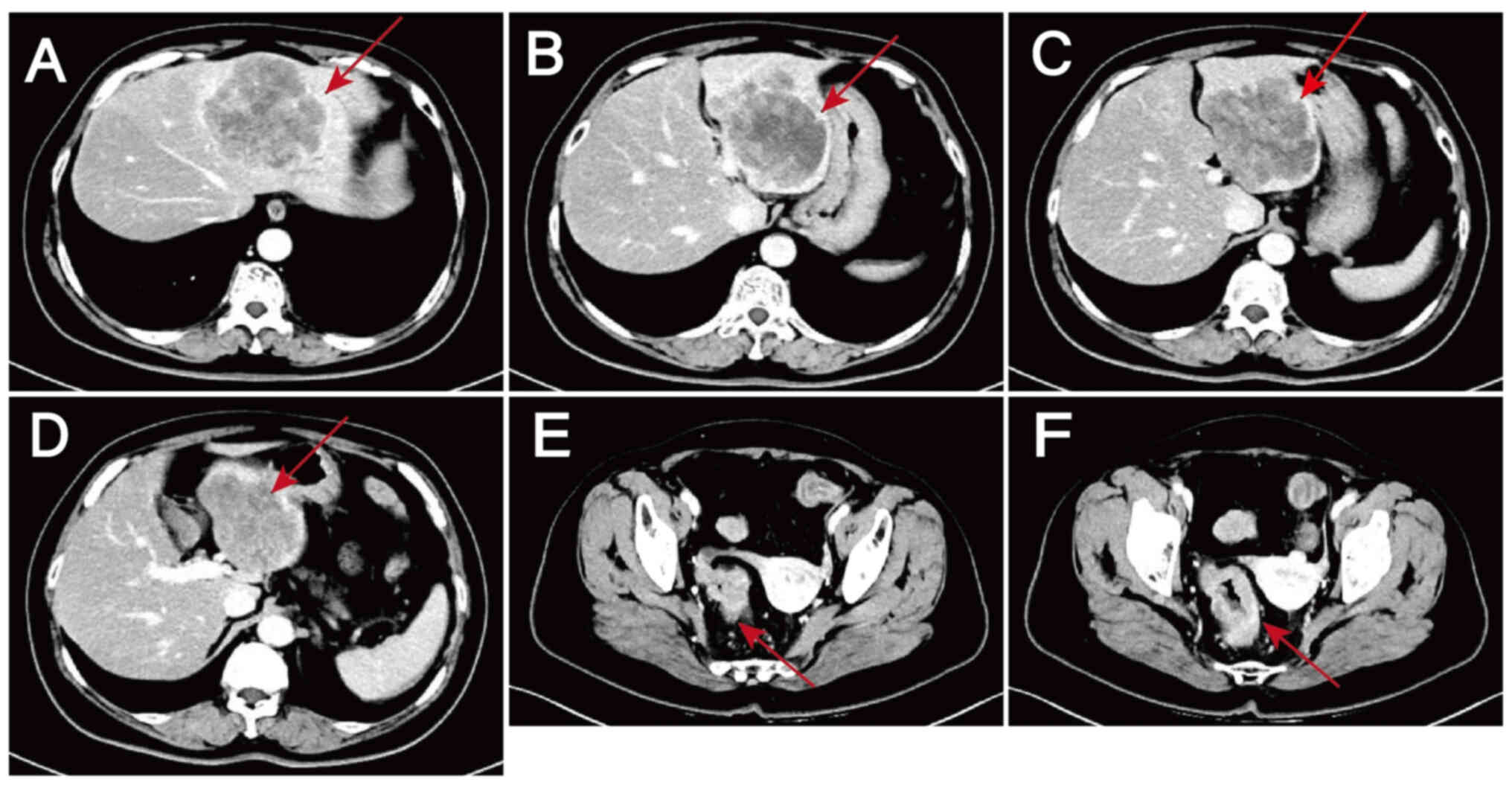

A 60-year-old woman with complaints of abdominal

pain and passage of bloody stools was admitted to Hebei General

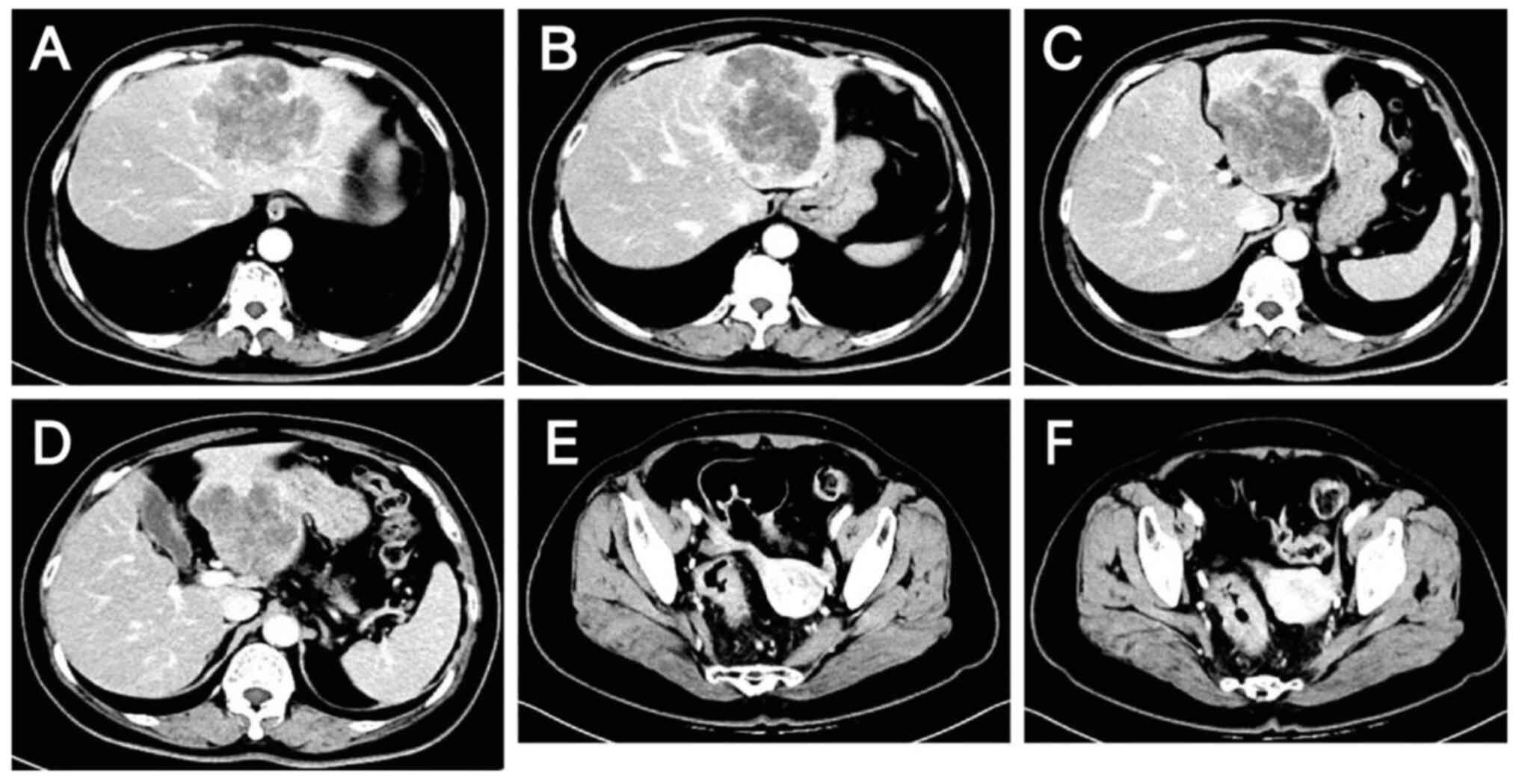

Hospital (Shijiazhuang, China) in October 2023. Contrast-enhanced

scans of the abdomen and pelvis revealed wall thickening in the

sigmoid colon and rectum, enlarged lymph nodes in the surrounding

area suggestive of malignancy, and low-density shadows in the S2,

S3 and S4 segments of the liver that were thought to be metastases

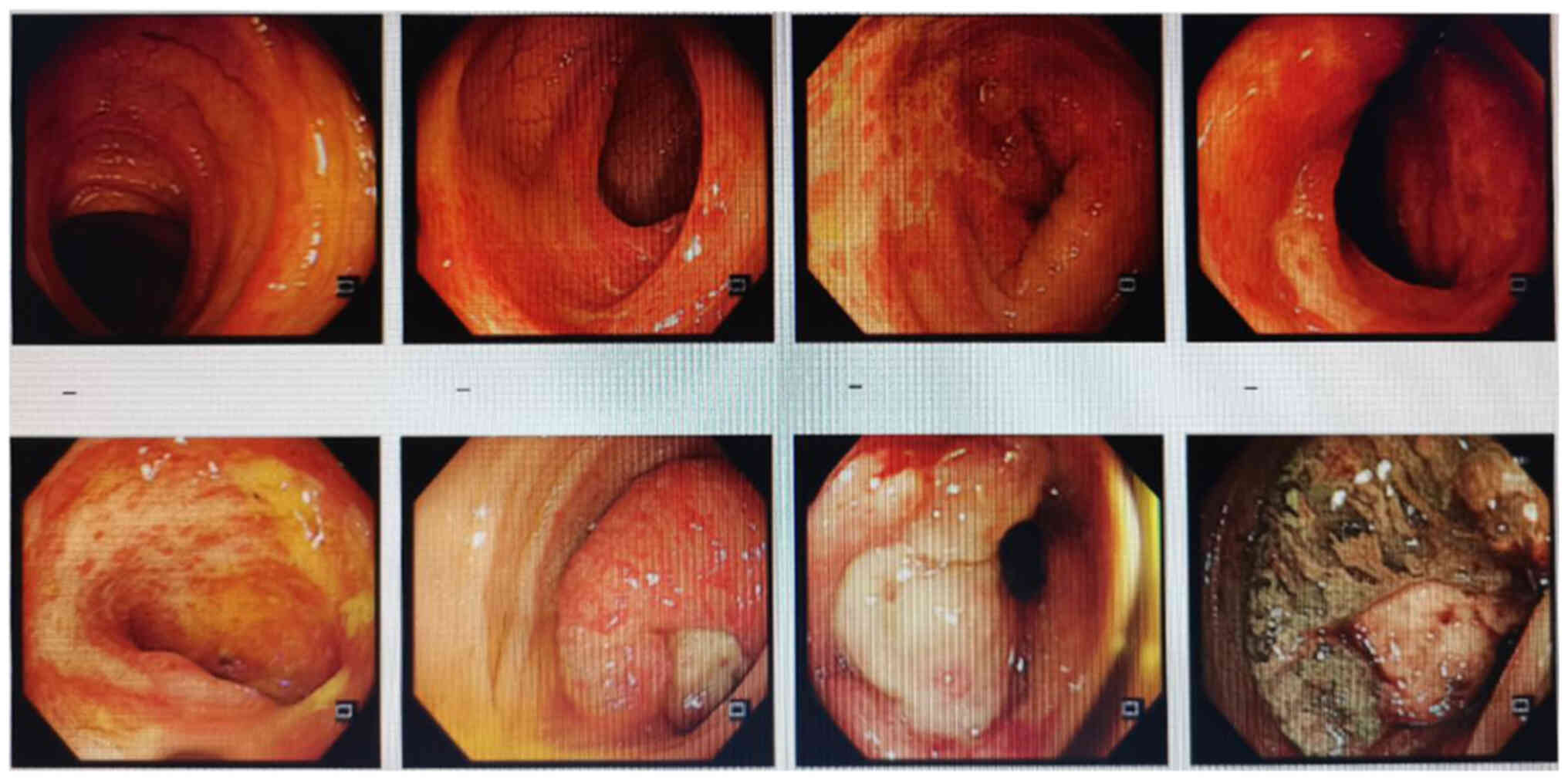

(Fig. 1). Colonoscopy suggested

rectal cancer, and a tissue biopsy revealed moderately and

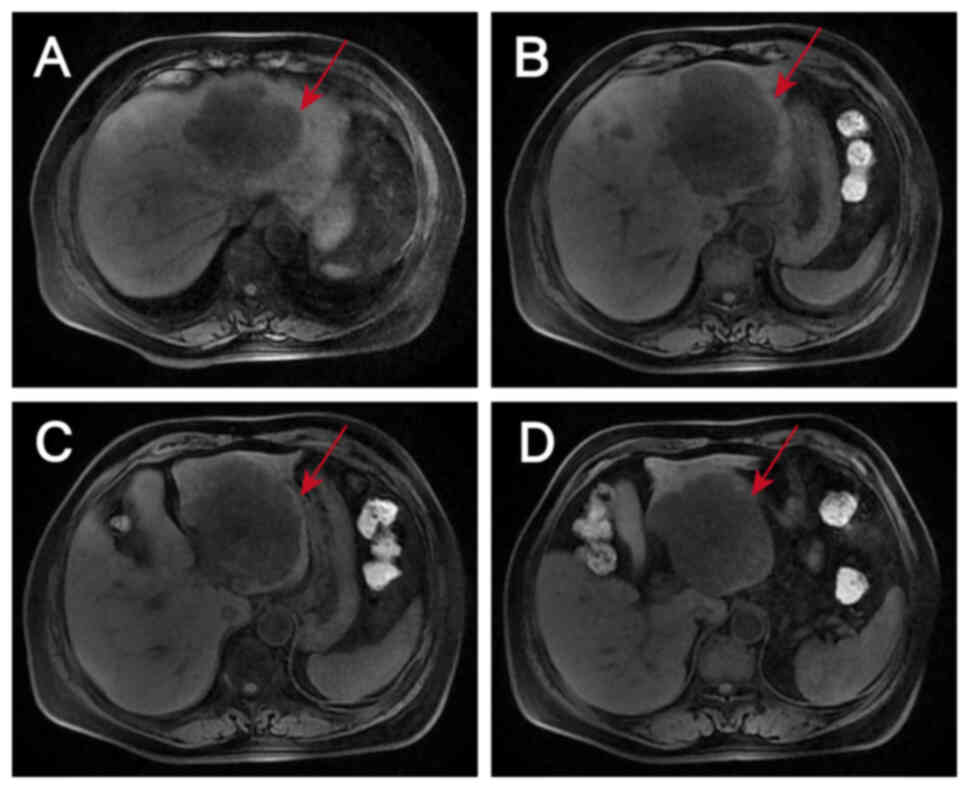

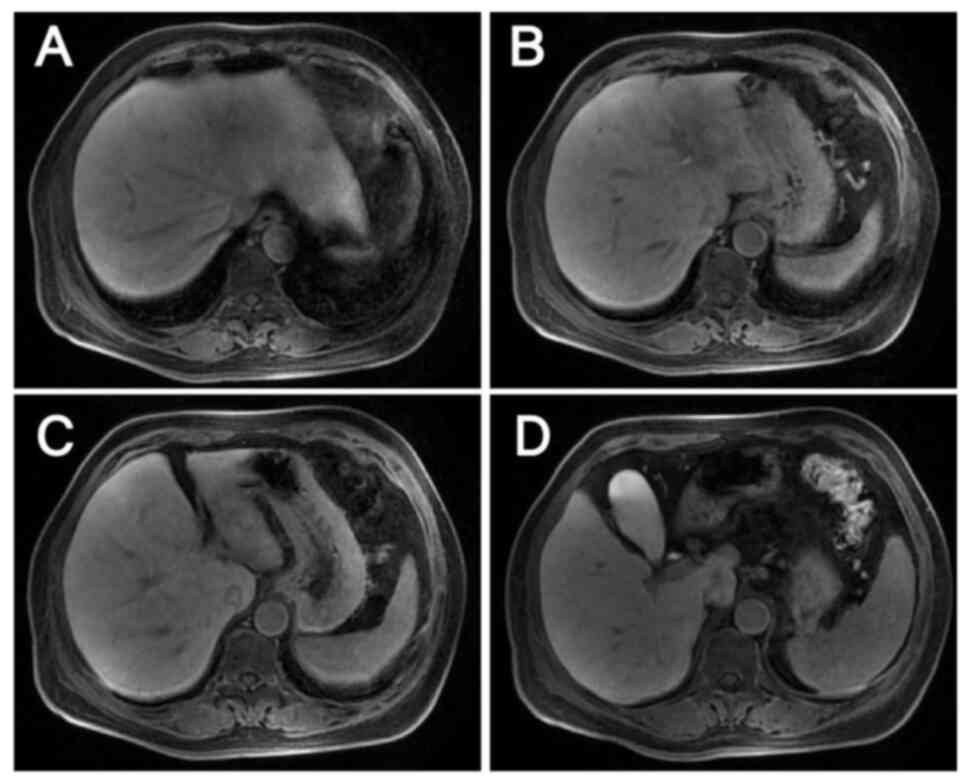

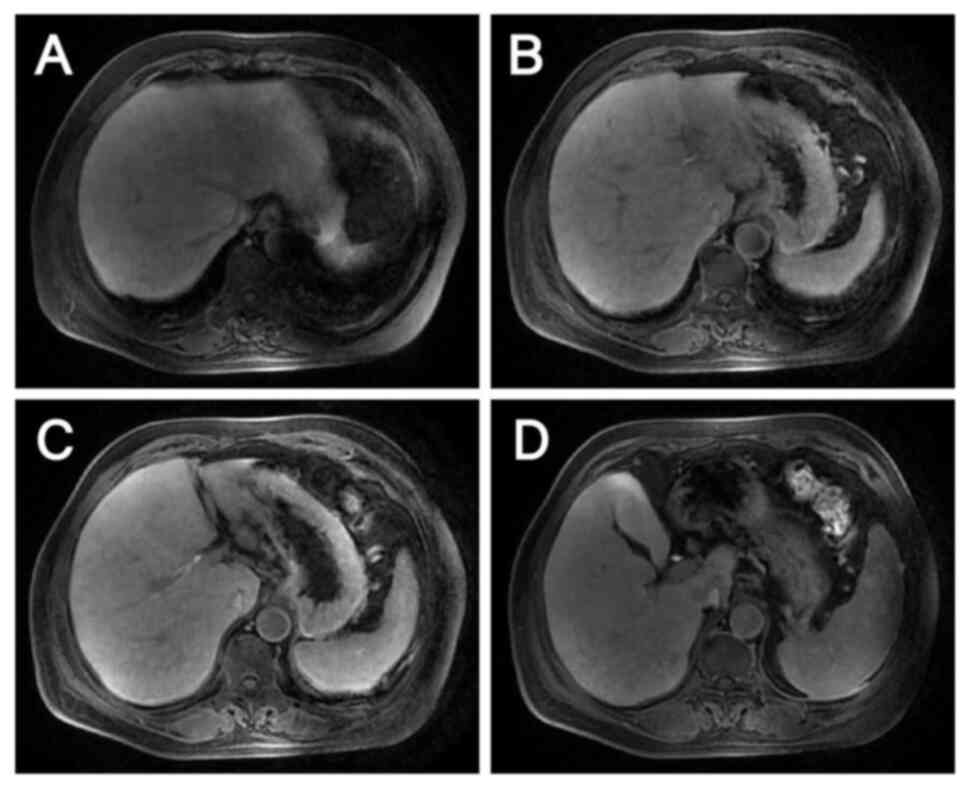

well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with necrosis (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance images revealed

liver metastases in the S2, S3 and S4 segments and two enlarged

lymph nodes, one anterior and one posterior to the portal vein

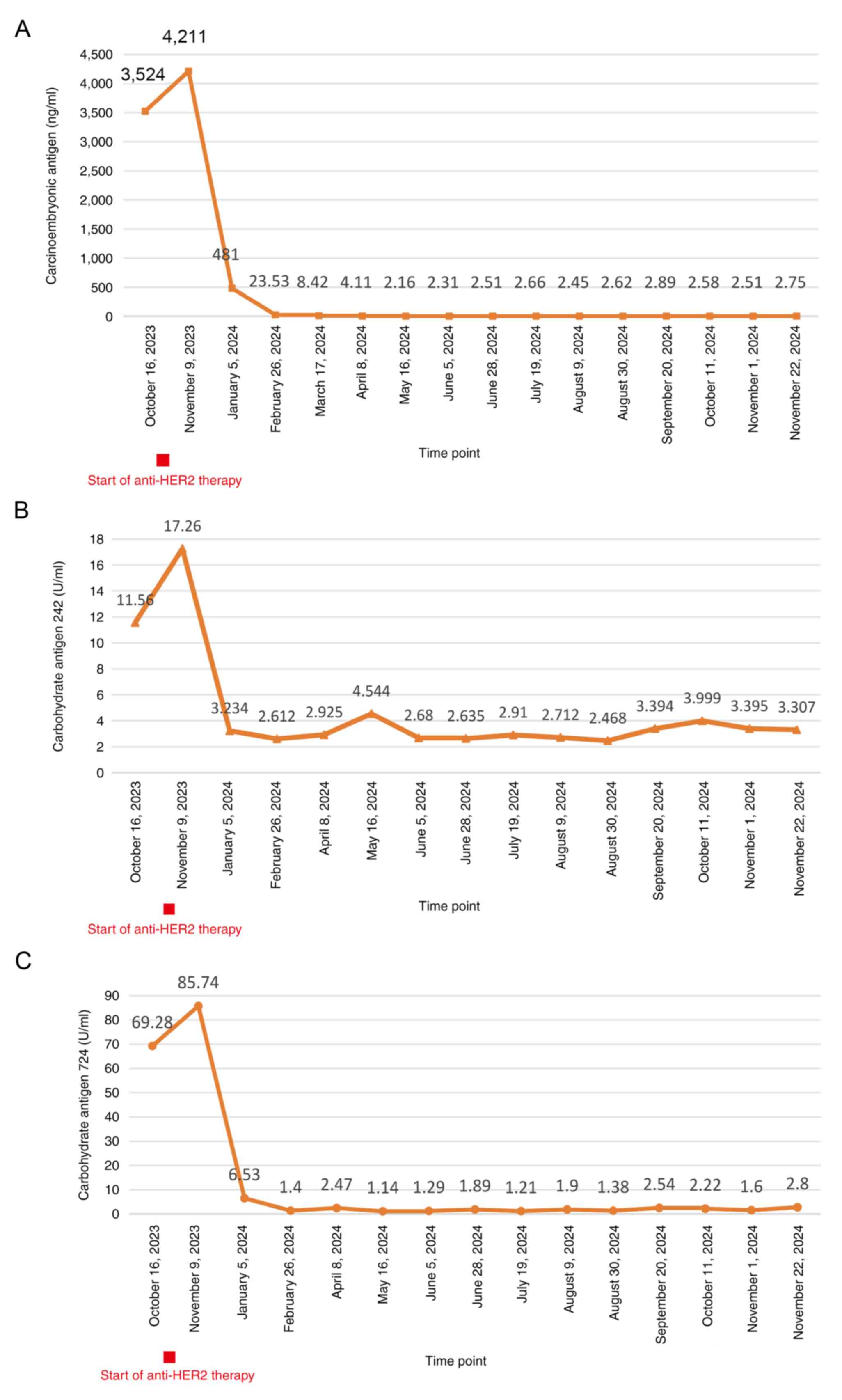

(Fig. 3). Digestive tract tumor

marker levels, including carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate

antigen (CA)242 and CA724, were all higher than normal (Fig. 4). NGS of a biopsy specimen obtained

by colonoscopy suggested that KRAS, NRAS and BRAF were WT (Figs. S1 and S2). It also revealed that ERBB2 (HER2)

had a mutation abundance 8.3-fold higher than the reference level,

suggesting possible resistance to panitumumab and cetuximab. In

addition, TP53 exon5c.399del had a mutation abundance of 31.61%,

suggesting microsatellite stability. The NGS was performed by

Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. DNA extraction and

library preparation was performed using the Qiagen QIAamp DNA FFPE

Kit (Qiagen, GmbH) and Agilent SureSelect XT HS2 (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.), respectively. Sample quality was assessed by

pathological analysis of tumor cell content, nucleic acid quality

assessment (total DNA amount, DNA degradation degree and total

pre-library amount) and sequencing quality assessment (average

sequencing depth, coverage uniformity, genome alignment rate and

base quality Q30 proportion). The hybridization capture method was

used, and the read length and sequencing direction were double ends

of 150 bp and double-end sequencing, respectively. The sequencing

platform and sequencing kit were the Illumina NextSeq 550 and

Illumina NextSeq 550 High Output kits (Illumina, Inc.),

respectively. Final library loading concentration was 1.2–1.8 pM.

The software used for the analysis included CNVkit (version 0.9.9;

University of California), GATK Mutect2 (version 4.1.8.1; Broad

Institute of MIT and Havard) and PierianDx (version 7.3; Velsera,

Inc.).

Following discussions among the multidisciplinary

team and considering the patient's preference for surgery,

neoadjuvant therapy was initiated, with plans to proceed to surgery

for the primary CRC lesions and liver metastases if the treatment

was effective. After obtaining informed consent, the patient was

treated with two cycles of a modified FOLFOX6 regimen based on a

body surface area of 1.66 m2, comprising oxaliplatin 140

mg + leucovorin calcium 600 mg + fluorouracil 0.625 g by

intravenous injection + fluorouracil 3.75 g. This regimen was

administered by continuous intravenous drip on 13 days post

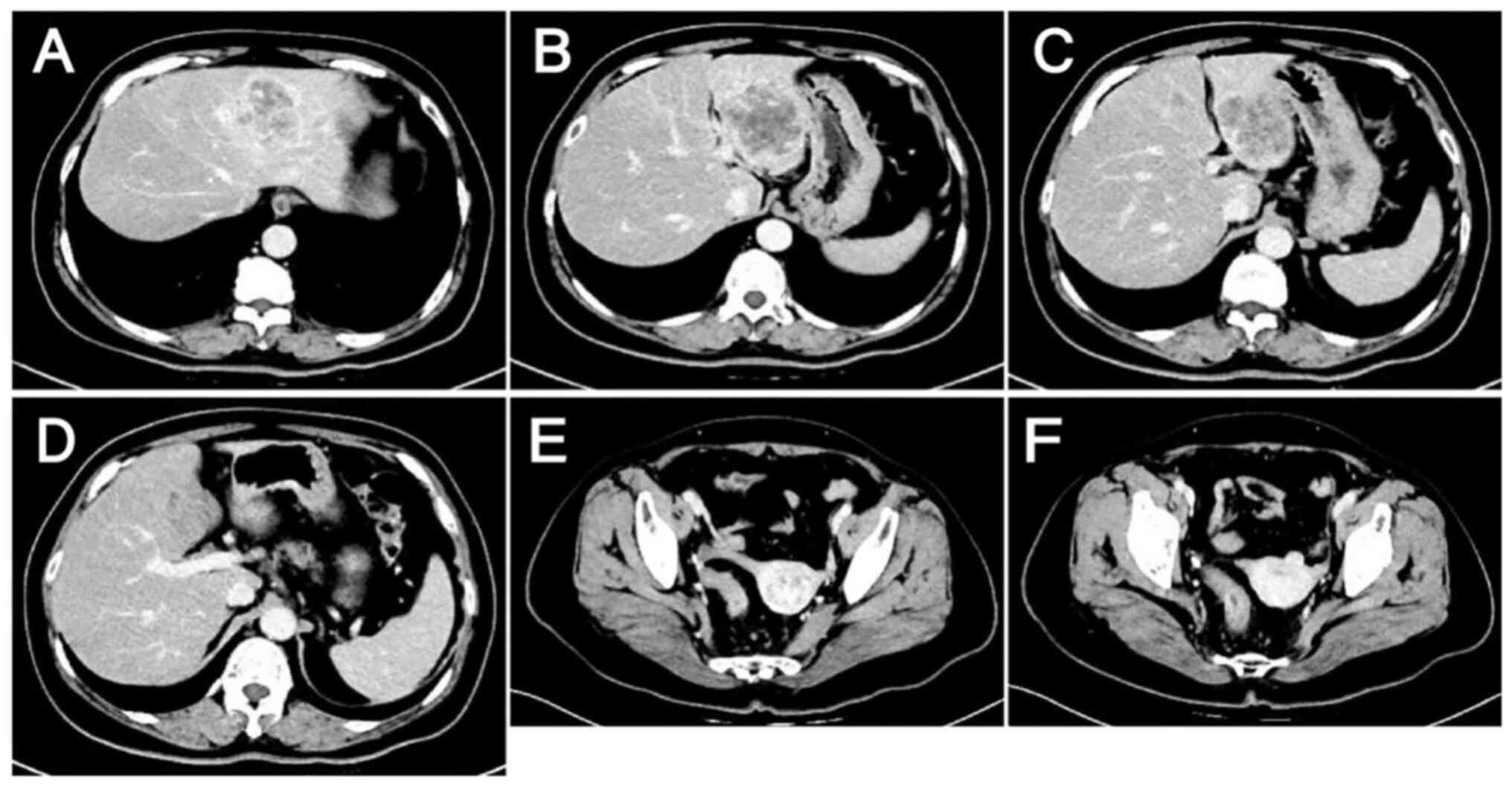

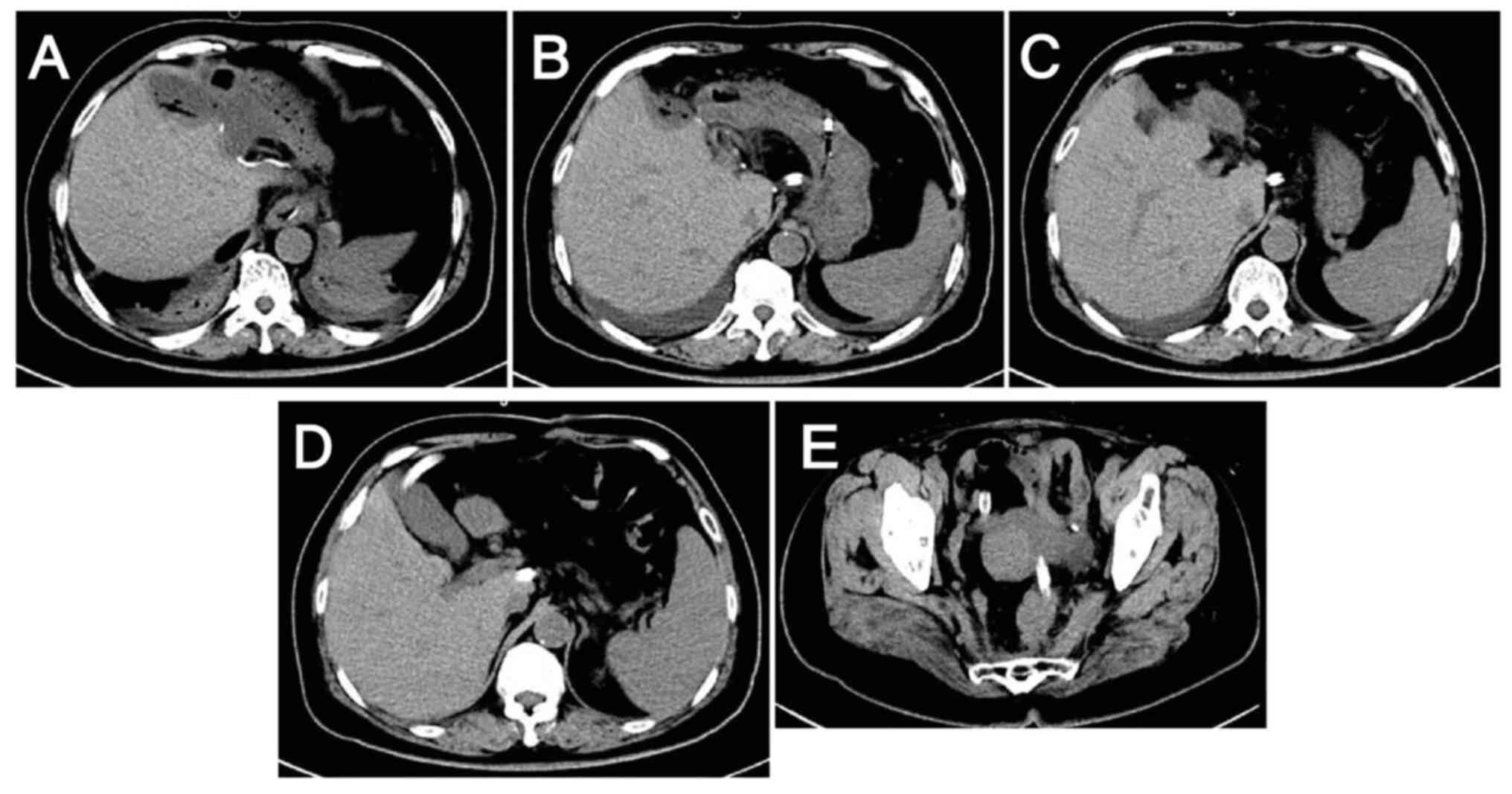

admission and 28 days post admission. However, after the two

cycles, no reduction in the size of the tumor lesions was evident

(Fig. 5) and the tumor marker

levels remained elevated (Fig. 4),

suggesting poor treatment efficacy.

EGFR inhibitor therapy was not considered due to the

NGS result and the evidence suggesting that patients with

HER2-positive CRC are highly resistant to EGFR inhibitors (11,12).

Furthermore, targeted bevacizumab therapy was not started because

hemorrhage is one of the most serious adverse effects of

bevacizumab and the patient had persistent hematochezia. In light

of the recent developments in CRC research and the financial

circumstances of the patient, single-agent anti-HER2 therapy

combined with a modified FOLFOX6 regimen was selected as the

subsequent treatment, in which the doses of chemotherapeutic agents

were adjusted and administered on a 3-week cycle. The patient

received six cycles of trastuzumab 450 mg + FOLFOX, with the latter

comprising oxaliplatin 150 mg + leucovorin calcium 600 mg +

fluorouracil 0.625 g by injection + fluorouracil 4 g by continuous

intravenous drip. These agents were administered on 41 days post

admission, 62 days post admission, 83 days post admission, 108 days

post admission, 134 days post admission, and 157 days post

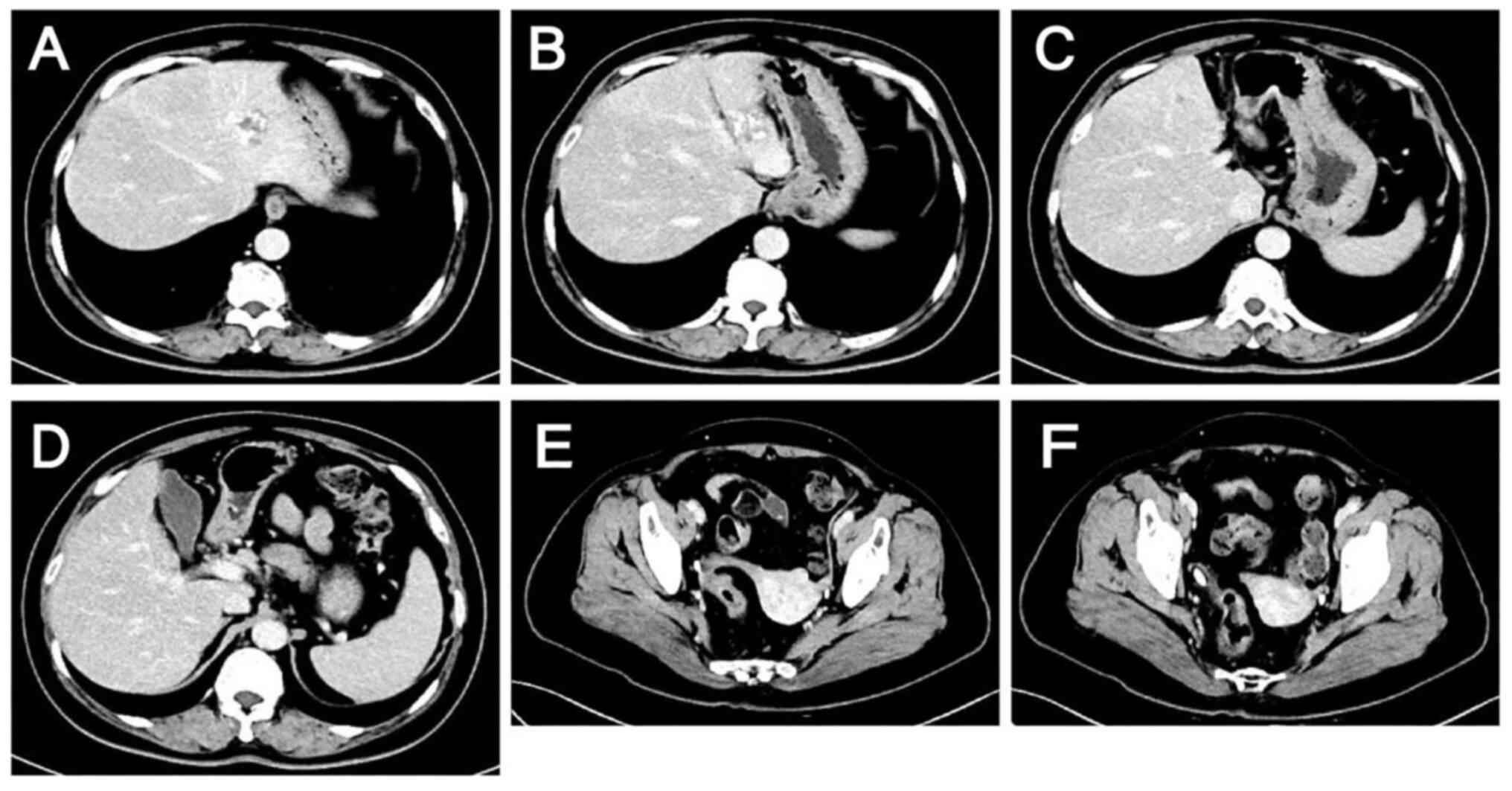

admission. During treatment, the tumor marker levels gradually

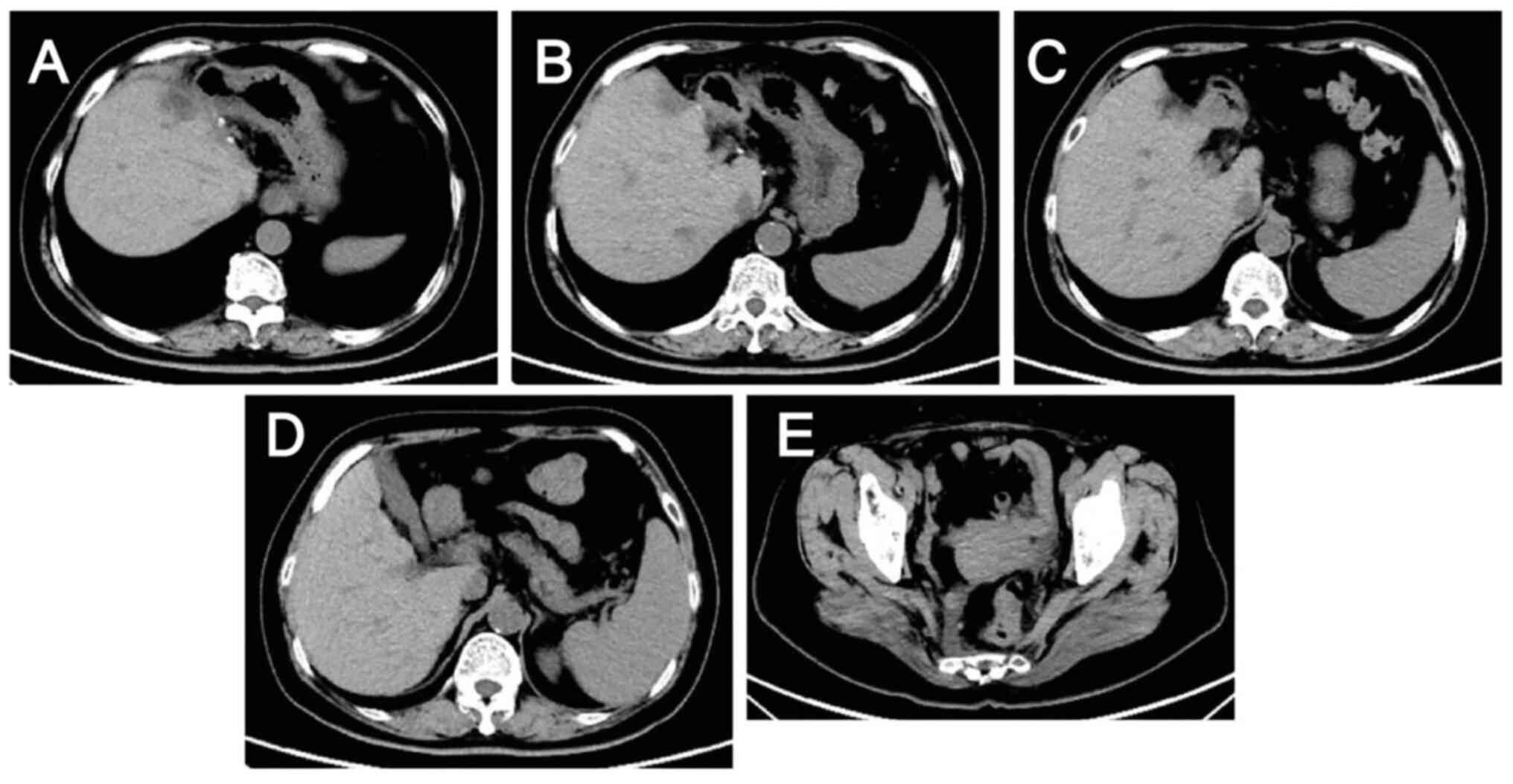

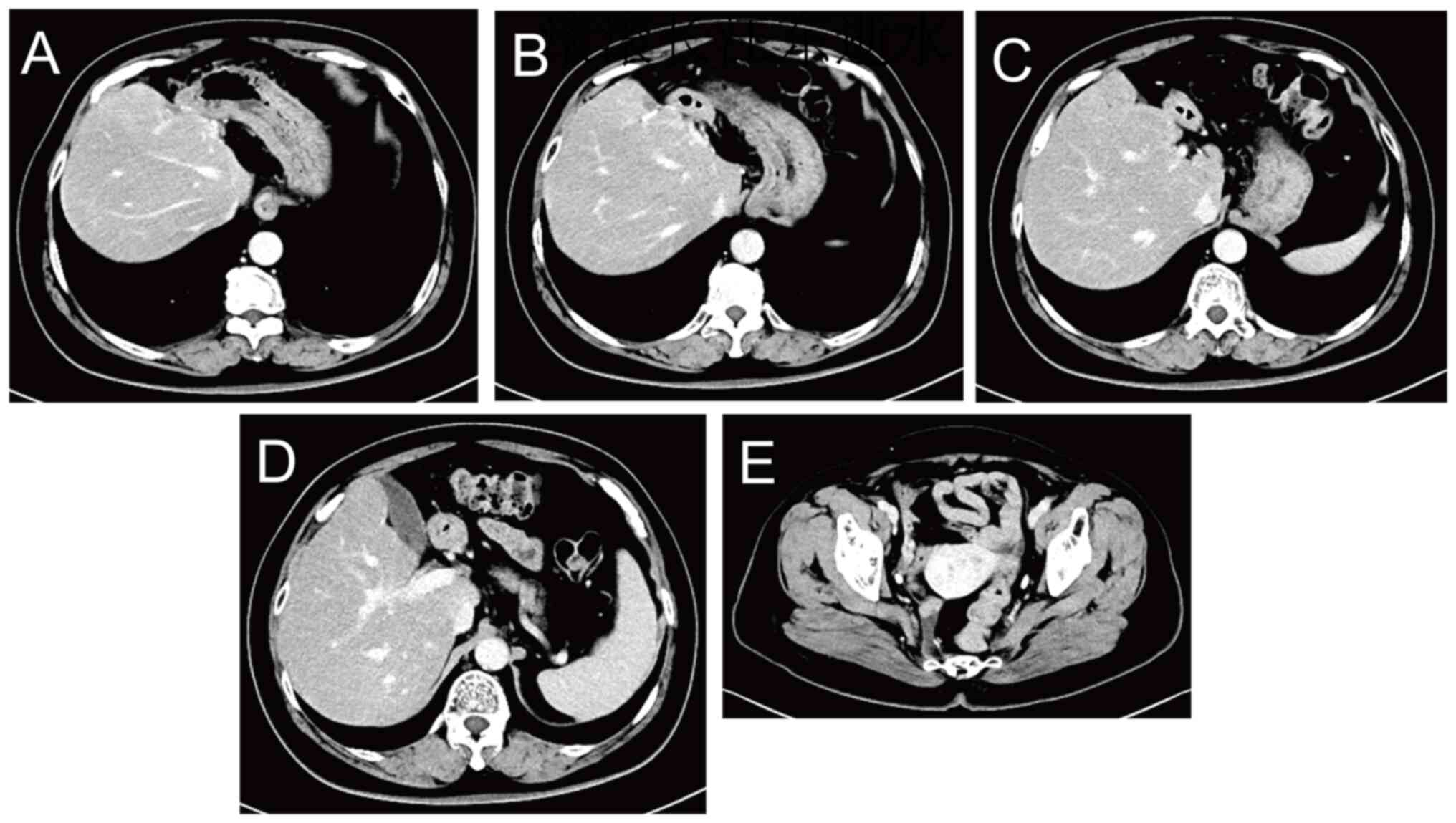

decreased (Fig. 4), and computed

tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance scans of the liver indicated

a marked reduction in the size of the tumor lesions (Fig. 6, Fig.

7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9). This was evaluated as a partial

response.

On April, 2024, the patient underwent

laparoscopy-assisted resection of rectal cancer and abdominal lymph

node dissection, followed by surgery for the liver metastases. This

included dissection of the group 8a lymph nodes, complete resection

of the left outer liver lobe with intrahepatic metastases, and S4

resection, including metastases. This radical resection of the

rectal cancer and liver metastases provided a foundation for

subsequent treatment and potential improvements in survival and

quality of life. Postoperative pathological examination of the

rectal specimen suggested moderately and well-differentiated

adenocarcinoma penetrating the muscularis propria to the subserosa,

with no intravascular cancer thrombus or nerve invasion, and

negative resection margins. One positive regional lymph node was

detected. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of the rectal specimen

suggested positivity for mismatch repair endonuclease PMS2 (PMS2),

DNA mismatch repair protein Msh2 (MSH2), DNA mismatch repair

protein Msh6 (MSH6) and DNA mismatch repair protein Mlh1 (MLH1),

which indicated microsatellite stability (Fig. S3). Postoperative pathological

examination of the excised liver tissue suggested moderately and

well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with a negative resection margin

and no lymph node involvement. For IHC, the tissues were

paraffin-embedded and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24

h at room temperature. The tissues were section to a 3-µm

thickness. 3% Hydrogen peroxide was used for blocking for 10 min at

room temperature. The following ready-to-use primary antibodies

supplied by Roche Diagnostics, were added at 37°C for 32 min:

VENTANA anti-MLH1 (M1) Mouse Monoclonal Primary Antibody (cat. no.

08033668001), VENTANA anti-MSH2 (G219-1129) Mouse Monoclonal

Primary Antibody (cat. no. 07862253001), VENTANA anti-MSH6 (SP93)

Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody (cat. no. 07862245001) and

VENTANA anti-PMS2 (A16-4) Mouse Monoclonal Primary Antibody (cat.

no. 08033692001). These primary antibodies and OptiView DAB IHC

Detection Kit (cat. no. 06396500001) supplied by Roche Diagnostics

were used together to detect mismatch repair protein. The OptiView

DAB IHC Detection Kit includes HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

optimized for automated staining on Ventana BenchMark instruments

and was added at 37°C for 30 min. Results were assessed under a

light microscope.

On postoperative day 6, abdominal-pelvic CT revealed

postoperative changes in the rectum and liver, along with blurring

of the left abdominal fat space, and small local nodules and small

lymph nodes in the hilar area and omental capsule (Fig. 10). Repeat CT examination on 27 days

post surgery showed less shadowing from the small nodules (Fig. 11).

The CT results indicated that a small lymph node in

the hilum and omental capsule had a short diameter of ~8 mm, could

be malignant, and would be difficult to remove surgically.

Therefore, seven 3-week cycles of anti-HER2 therapy (300 mg

trastuzumab on day 1 of the cycle) combined with oral chemotherapy

(1 g capecitabine twice daily on days 1–14 of the cycle) were

administered on 28, 39, 60, 81, 102, 123 and 145 days post-surgery.

Thereafter, the chemotherapy was discontinued and the patient

received three 3-week cycles of anti-HER2 therapy (trastuzumab 300

mg) on 165, 186 and 207 days post-surgery. The tumor marker levels

were within the normal range during the postoperative period, and

the patient remained on anti-HER2 therapy for 1 year. The latest CT

result, which was recorded on 210 days post-surgery, showed

postoperative changes in the rectum and liver, along with no signs

of recurrence (Fig. 12). The

patient was found to be in good condition and discontinued

anti-HER2 therapy with instructions to attend for review every 3

months. The timeline of the treatment sequences, imaging

evaluations and key clinical events are shown in Fig. 13.

Discussion

The incidence of HER2 positivity in CRC is

relatively low, at only ~5% overall (5). HER2 is a member of the ERBB family of

transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which also includes

ERBB1 (EGFR), ERBB3 and ERBB4 (13,14).

It is widely accepted that the overexpression, amplification or

mutation of HER2 results in resistance to EGFR inhibitors and can

be used as a biomarker for the prediction of treatment efficacy

(11,12,15).

The EGFR inhibitor cetuximab exerts an antitumor effect by

inhibiting EGFR and downstream ERK activation, thereby hindering

cancer cell proliferation (16).

The mechanism underlying resistance to EGFR inhibitors is thought

to involve HER2 amplification, leading to aberrant activation of

HER2-ERK signal transduction and the bypass of EGFR-ERK signaling

(16). Accordingly, ERK activation

is maintained in HER2-amplified cells, conferring resistance to

EGFR inhibitors in patients with HER2-positive tumors (16). The specific targeting of HER2 with

small interfering RNA or HER2 inhibitors has been shown to block

HER2 and ERK activation in HER2-amplified cells, thereby restoring

sensitivity to cetuximab (16).

These findings suggest that the HER2-mediated activation of

alternative signaling pathways promotes resistance to EGFR

inhibitors and that anti-HER2 therapy could potentially restore

sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors and exert an anticancer effect in

HER2-positive tumors. Preclinical and clinical studies have shown

that the progression-free and overall survival rates achieved by

EGFR inhibitors in patients with HER2-amplified CRC are

significantly lower than those of their WT counterparts and

comparable with those in patients with RAS or BRAF mutations

(17,18). This suggests that HER2 predicts a

poor response to EGFR inhibitor therapy. Therefore, we hypothesize

that CRC with HER2 positivity, whether amplified, overexpressed or

mutated, can lead to resistance to EGFR inhibitors and that the

early initiation of anti-HER2 therapy should be considered.

In the present case, the NGS results indicated that

KRAS, NRAS and BRAF were all WT, while ERBB2 (HER2) was mutated and

amplified with a mutation abundance elevated 8.3-fold. These

findings suggest possible resistance to drugs such as panitumumab

and cetuximab, based on the aforementioned findings. Accordingly,

first-line chemotherapy alone was initiated for metastatic CRC;

however, after two cycles, an increase in tumor marker levels was

observed and no clear change in the size of the lesions was shown

by imaging, indicating that chemotherapy alone was having a poor

effect. Given advances in clinical trials on CRC diagnosis and

treatment, as well as the patient's circumstances, the patient was

subsequently treated with anti-HER2 therapy combined with

chemotherapy. Notably, tumor markers gradually decreased during the

treatment, and imaging revealed a reduction in the size of the

lesions. After six cycles of treatment, the tumor marker levels

were within the normal range and the lesions were markedly smaller.

Simultaneous surgical resection of the rectal cancer and liver

metastases was subsequently achieved, demonstrating that anti-HER2

therapy can be beneficial in the treatment of metastatic CRC.

Although HER2 has a well-established prognostic significance in

breast cancer, its prognostic role in metastatic CRC remains

unclear (19). However, HER2

positivity appears to have been beneficial in the present case,

converting unresectable lesions into resectable ones after

anti-HER2 therapy, potentially improving the prognosis and quality

of life of the patient.

HER2 positivity is more common in patients with

RAS/BRAF WT disease (20), with one

study reporting HER2 upregulation in only 1.0% of patients with

KRAS/BRAF mutations compared with 5.2% in those with WT disease

(21). In the MyPathway trial, 23%

of patients had KRAS mutations, with an objective response rate

(ORR) of only 8%, much lower than the ORR of 40% observed for

patients with KRAS WT disease (22). An exploratory analysis of the Phase

II TRIUMPH study also showed the treatment responses in patients

with alterations in RTK/RAS/PI3K-related genes detected by

circulating tumor DNA were poorer compared with those of patients

without these alterations (23).

These studies suggest that patients with KRAS WT disease may have a

stronger response to anti-HER2 therapy. The microsatellite

instability (MSI) status of CRC can be classified as MSI-high,

MSI-low or microsatellite-stable (MS-stable) (24). Immunotherapy offers significant

benefits to patients with MSI-high CRC and has been approved in

this indication by the US Food and Drug Administration. However, it

does not provide a significant survival advantage in patients with

MS-stable CRC (25). In the present

case, NGS results showed that KRAS, NRAS and BRAF were WT, the

tumor microsatellite status was MS-stable, and HER2 expression was

positive; therefore, anti-HER2 therapy was recommended.

HER2 overexpression or amplification is

traditionally assessed by IHC to evaluate protein expression and by

in situ hybridization (ISH) to evaluate gene amplification.

The diagnostic criteria developed by Valtorta et al

(26) for the HERACLES clinical

trial established a standardized procedure for defining HER2

positivity in CRC by IHC and ISH. According to these criteria, HER2

status is considered positive if there is intense (3+) IHC staining

in ≥50% of cells, or either intense (3+) IHC staining in >10 to

<50% of cells or moderate (2+) IHC staining in ≥50% of cells,

combined with amplification on ISH testing, defined as an ERBB2 to

centromere of chromosome 17 ratio of ≥2 in ≥50% of cells (26). Studies (27,28)

have shown that NGS results are closely consistent with IHC/ISH

testing results, and can also be used to evaluate the amplification

of HER2 in CRC. Furthermore, the assessment of circulating tumor

DNA by liquid biopsy is a simple method for the detection of HER2

status that requires only a blood sample rather than a tissue

biopsy, with some studies demonstrating its success in metastatic

CRC (23,29,30).

Therefore, the circulating tumor DNA assay can be used to

complement tissue-based methods or serve as an alternative when

tissue testing is not feasible. Sartore-Bianchi et al

(12) proposed that HER2 status

assessment should be included in the molecular diagnostic workup of

all patients with metastatic CRC to allow prompt referral to

clinical trials involving HER2-targeted double blockade, regardless

of previous anti-EGFR treatment. Another study emphasized the

importance of detecting HER2 status in patients with advanced or

metastatic CRC, particularly those with RAS WT and MS-stable

disease (31). The current National

Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend the assessment of

HER2 status in all patients with metastatic CRC using either

IHC/ISH or NGS (32). This

indicates that greater emphasis should be placed on the detection

of HER2 expression in patients with CRC, particularly those with

metastatic disease. Timely treatment based to these results may

lead to enhanced clinical outcomes and an improved prognosis.

The findings from the Trastuzumab for Gastric Cancer

trial, published in 2010, revealed that the mean overall survival

of patients with HER2-positive (IHC 3+ or overexpression on

fluorescence ISH) recurrent or metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma or

gastric-esophageal junction cancer was prolonged when trastuzumab

was added to first-line chemotherapy. In addition, the combination

of trastuzumab and chemotherapy exhibited a safety profile

comparable with that of first-line chemotherapy alone (33). This discovery marked a shift from

traditional therapy to a new era of molecular targeted therapy for

gastric cancer. Trastuzumab combined with chemotherapy is now

considered the standard first-line treatment for HER2-positive

gastric cancer (34,35). Furthermore, the 2023 Chinese Society

of Clinical Oncology gastric cancer guidelines emphasize that HER2

status testing is necessary in all patients with a confirmed

pathological diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma (36).

Patients with gastric cancer are tested early for

HER2 status, and those who are positive receive first-line

anti-HER2 treatment. However, in CRC, the testing of anti-HER2

treatment typically occurs later. Insights from the present case

and a review of the literature on anti-HER2 therapy for gastric

cancer suggest some notable similarities between the diagnosis and

treatment principles of gastric cancer and those of CRC (33). This leads to the suggestion that the

early detection of the HER2 expression status of patients with CRC,

particularly those with metastatic CRC, could allow anti-HER2

therapy to be brought forward into the first-line setting,

potentially improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Similarly, another study proposed that anti-HER2 therapy for

HER2-amplified CRC should be initiated as soon as possible rather

than reserved for last-line application (37). However, further research is

necessary to determine whether the earlier application of anti-HER2

therapy should be included in clinical guidance on the diagnosis

and treatment of CRC.

At present, anti-HER2 therapy mainly includes

monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab, tyrosine

kinase inhibitors such as lapatinib and tucatinib, and

antibody-drug conjugates, including trastuzumab deruxtecan and

trastuzumab emtansine. Advances in molecular pathology and

detection methods have led to a series of studies in patients with

HER2-positive CRC, including MyPathway, TRIUMPH, MOUNTAINEER,

DESTINY-CRC and HERACLES (22,38–40).

Most treatments in these studies involved a dual-targeted approach,

such as a combination of two anti-HER2 antibodies or a monoclonal

antibody combined with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Significant

improvements have been reported in the overall prognosis for these

treatments compared with standard treatment or best supportive care

in the aforementioned trials, particularly with regard to the ORR,

suggesting that patients with HER2-positive CRC can benefit from

anti-HER2 therapy. Based on these promising outcomes, the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend four

HER2-targeted regimens, namely, trastuzumab combined with

pertuzumab, lapatinib or tucatinib, or trastuzumab deruxtecan

(DS-8201) alone for patients with CRC, HER2 amplification and WT

RAS/BRAF (32). In the present

case, a dual-targeted regimen was not feasible due to financial

constraints. Therefore, single-agent trastuzumab was used as a

targeted therapy and achieved favorable results. Nevertheless, a

dual-targeted approach is recommended when financial resources

allow.

Trastuzumab deruxtecan is an antibody-drug conjugate

consisting of trastuzumab linked to a topoisomerase I inhibitor.

The Phase II DESTINY-CRC01 trial assessed the activity of this

agent in patients with HER2-positive, WT RAS/BRAF and previously

treated metastatic CRC at a dosage of 6.4 mg/kg every 3 weeks

(40). In contrast with the

aforementioned trials (22,38,39),

the DESTINY-CRC01 trial allowed the inclusion of patients who had

previously received anti-HER2 therapy (40). This trial found no significant

reduction in the response rate in patients who had previously

received anti-HER2 therapy, suggesting that trastuzumab deruxtecan

is effective in anti-HER2-pretreated patients (40). The subsequent DESTINY-CRC02 trial

explored the efficacy of two dose levels of trastuzumab deruxtecan

(6.4 and 5.4 mg/kg) administered every 3 weeks (41). Unlike DESTINY-CRC01, DESTINY-CRC02

enrolled patients with both RAS-WT and RAS-mutant CRC (41). No significant difference in

treatment response was observed between the two dose levels

(41). However, due to toxicity

concerns, the 5.4 mg/kg dosage was preferred, supporting its use in

future treatments. This trial demonstrated a promising treatment

effect in patients with RAS-mutated disease (n=20; ORR 20.0%) and

those who had previously received anti-HER2 therapy (n=27; ORR

40.1%), suggesting that trastuzumab deruxtecan could be considered

for the subsequent treatment of HER2-positive and RAS-mutated

metastatic CRC (41). In addition,

both trials showed that the response of patients with IHC 3+

disease was improved compared with that of patients with IHC

2+/ISH+ disease, indicating that high HER2 expression may be

important for an effective response to anti-HER2 therapy (40,41).

Most anti-HER2 therapy regimens used in clinical

trials for HER2-positive CRC have demonstrated good tolerability.

However, cardiotoxicity associated with anti-HER2 agents, and

interstitial lung disease or pneumonia associated with trastuzumab

deruxtecan warrant careful monitoring (42–44).

In the present case, the patient tolerated anti-HER2 therapy well,

with no adverse effects observed. The results of regular

electrocardiograms and measurements of left ventricular ejection

fraction were within the normal ranges. Cardiac function should be

assessed before, during and after the completion of HER2-targeted

therapy, and treatment should be withheld or discontinued if a

significant reduction in ejection fraction is observed (45,46).

Grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events have been reported in

clinical trials of trastuzumab deruxtecan for breast cancer,

gastric cancer and CRC (47–49).

Therefore, patients treated with this agent should be promptly

evaluated for any signs or symptoms of pulmonary toxicity. The

aforementioned studies (40,41)

have investigated a variety of anti-HER2 agents, including some

that remain under investigation. Further clinical research is

necessary to determine the optimal anti-HER2 regimen and the

appropriate sequencing of subsequent anti-HER2 therapies.

Currently available anti-HER2 therapies have

provided clinical benefits to certain patients with HER2-positive

CRC. However, more than half of patients do not experience any

benefit, suggesting that anti-HER2 therapy has some limitations. A

meta-analysis found a median progression-free survival of only 4.89

months in patients with advanced CRC receiving anti-HER2 therapy

(50). The relatively lower

efficacy of anti-HER2 therapy in patients with HER2-positive CRC in

comparison with that in patients with other types of cancer may be

associated with HER2 resistance (51). While a number of studies have shown

that the overexpression or mutation of genes involved in the

RTK/RAS and PI3K pathways may contribute to resistance to anti-HER2

therapy (51–53), additional studies are necessary to

explore the mechanisms of this resistance. This may facilitate the

identification of strategies that can overcome drug resistance and

enhance the clinical benefits of this therapy for patients with

HER2-positive CRC.

In conclusion, anti-HER2 therapy has not been

thoroughly investigated in CRC, and the relationship between HER2

positivity and the prognosis of patients with CRC remains

inconclusive. The present case provides evidence that patients with

HER2-positive CRC could significantly benefit from anti-HER2

therapy, and such therapy may confer a good prognosis for patients.

Moreover, given that HER2 positivity is associated with resistance

to EGFR inhibitors, early anti-HER2-containing combination therapy

is warranted. Therefore, it is important to assess HER2 status

promptly and accurately in patients with CRC, particularly those

with metastatic disease. Further studies are required to determine

whether anti-HER2 therapy can be moved into the frontline setting

for patients with HER2-positive CRC and to identify the optimal

anti-HER2 regimen.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of

Hebei Province in 2021 and 2024 (grant nos. H2021307016 and

H2024206176) and Projects from Health and Family Planning

Commission of Hebei Province (grant no. 20220829).

Availability of data and materials

The NGS data generated in the present study may be

found in the BioProject database under accession number

PRJNA1247027 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1247027. The

remaining data generated in the present study are included in the

figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

JH, ZL and XF collected clinical data, reviewed the

literature and drafted the manuscript. DH, XL, YW, QL and DW

collected clinical data and contributed to drafting the manuscript.

XF and JH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of their data and associated images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

EGFR

|

epidermal growth factor receptor

|

|

HER2

|

human epidermal growth factor receptor

2

|

|

NGS

|

next-generation sequencing

|

|

ORR

|

objective response rate

|

|

WT

|

wild-type

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Biller LH and Schrag D: Diagnosis and

treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A review. JAMA.

325:669–685. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yarden Y and Sliwkowski MX: Untangling the

ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2:127–137. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ross JS, Fakih M, Ali SM, Elvin JA,

Schrock AB, Suh J, Vergilio JA, Ramkissoon S, Severson E, Daniel S,

et al: Targeting HER2 in colorectal cancer: The landscape of

amplification and short variant mutations in ERBB2 and ERBB3.

Cancer. 124:1358–1373. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Marsoni S,

Hurwitz HI, McCall SJ, Penault-Llorca F, Srock S, Bardelli A and

Trusolino L: Targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

(HER2) oncogene in colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 29:1108–1119.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Margonis GA, Buettner S, Andreatos N, Kim

Y, Wagner D, Sasaki K, Beer A, Schwarz C, Løes IM, Smolle M, et al:

Association of BRAF mutations with survival and recurrence in

surgically treated patients with metastatic colorectal liver

cancer. JAMA Surg. 153:e1809962018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Suwaidan AA, Lau DK and Chau I: HER2

targeted therapy in colorectal cancer: New horizons. Cancer Treat

Rev. 105:1023632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rosati G, Aprile G, Colombo A, Cordio S,

Giampaglia M, Cappetta A, Porretto CM, De Stefano A, Bilancia D and

Avallone A: Colorectal cancer heterogeneity and the impact on

precision medicine and therapy efficacy. Biomedicines. 10:10352022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yang L, Li W, Lu Z, Lu M, Zhou J, Peng Z,

Zhang X, Wang X, Shen L and Li J: Clinicopathological features of

HER2 positive metastatic colorectal cancer and survival analysis of

anti-HER2 treatment. BMC Cancer. 22:3552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chitkara A, Bakhtiar M, Sahin IH, Hsu D,

Zhang J, Anamika F, Mahnoor M, Ahmed R, Gholami S and Saeed A: A

meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of HER2-targeted treatment

regimens in HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Curr

Oncol. 30:8266–8277. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li QH, Wang YZ, Tu J, Liu CW, Yuan YJ, Lin

R, He WL, Cai SR, He YL and Ye JN: Anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic

colorectal cancer: Mechanisms and potential regimens of drug

resistance. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 8:179–191. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sartore-Bianchi A, Amatu A, Porcu L,

Ghezzi S, Lonardi S, Leone F, Bergamo F, Fenocchio E, Martinelli E,

Borelli B, et al: HER2 positivity predicts unresponsiveness to

EGFR-targeted treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer.

Oncologist. 24:1395–1402. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hynes NE and Lane HA: ERBB receptors and

cancer: The complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer.

5:341–354. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Popescu NC, King CR and Kraus MH:

Localization of the human erbB-2 gene on normal and rearranged

chromosomes 17 to bands q12-21.32. Genomics. 4:362–366. 1989.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang G, He Y, Sun Y, Wang W, Qian X, Yu X

and Pan Y: Prevalence, prognosis and predictive status of HER2

amplification in anti-EGFR-resistant metastatic colorectal cancer.

Clin Transl Oncol. 22:813–822. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yonesaka K, Zejnullahu K, Okamoto I, Satoh

T, Cappuzzo F, Souglakos J, Ercan D, Rogers A, Roncalli M, Takeda

M, et al: Activation of ERBB2 signaling causes resistance to the

EGFR-directed therapeutic antibody cetuximab. Sci Transl Med.

3:99ra862011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sawada K, Nakamura Y, Yamanaka T, Kuboki

Y, Yamaguchi D, Yuki S, Yoshino T, Komatsu Y, Sakamoto N, Okamoto W

and Fujii S: Prognostic and predictive value of HER2 amplification

in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal

Cancer. 17:198–205. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jeong JH, Kim J, Hong YS, Kim D, Kim JE,

Kim SY, Kim KP, Yoon YK, Kim D, Chun SM, et al: HER2 amplification

and cetuximab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal

cancer harboring wild-type RAS and BRAF. Clin Colorectal Cancer.

16:e147–e152. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jang JY, Jeon YK, Jeong SY, Lim SH, Park

YS, Lim HY, Lee JY and Kim ST: Effect of human epidermal growth

factor receptor 2 overexpression in metastatic colorectal cancer on

standard chemotherapy outcomes. J Gastrointest Oncol. 14:2097–1110.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Nam SK, Yun S, Koh J, Kwak Y, Seo AN, Park

KU, Kim DW, Kang SB, Kim WH and Lee HS: BRAF, PIK3CA, and HER2

oncogenic alterations according to KRAS mutation status in advanced

colorectal cancers with distant metastasis. PLoS One.

11:e01518652016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Richman SD, Southward K, Chambers P, Cross

D, Barrett J, Hemmings G, Taylor M, Wood H, Hutchins G, Foster JM,

et al: HER2 overexpression and amplification as a potential

therapeutic target in colorectal cancer: Analysis of 3256 patients

enrolled in the QUASAR, FOCUS and PICCOLO colorectal cancer trials.

J Pathol. 238:562–570. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Meric-Bernstam F, Hurwitz H, Raghav KPS,

McWilliams RR, Fakih M, VanderWalde A, Swanton C, Kurzrock R,

Burris H, Sweeney C, et al: Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab for

HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer (MyPathway): An updated

report from a multicentre, open-label, phase 2a, multiple basket

study. Lancet Oncol. 20:518–530. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nakamura Y, Okamoto W, Kato T, Esaki T,

Kato K, Komatsu Y, Yuki S, Masuishi T, Nishina T, Ebi H, et al:

Circulating tumor DNA-guided treatment with pertuzumab plus

trastuzumab for HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer: A

phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 27:1899–1903. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jass JR: Classification of colorectal

cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and

molecular features. Histopathology. 50:113–130. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zumwalt TJ and Goel A: Immunotherapy of

metastatic colorectal cancer: Prevailing challenges and new

perspectives. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 11:125–140. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Valtorta E, Martino C, Sartore-Bianchi A,

Penaullt-Llorca F, Viale G, Risio M, Rugge M, Grigioni W,

Bencardino K, Lonardi S, et al: Assessment of a HER2 scoring system

for colorectal cancer: Results from a validation study. Mod Pathol.

28:1481–1491. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fujii S, Magliocco AM, Kim J, Okamoto W,

Kim JE, Sawada K, Nakamura Y, Kopetz S, Park WY, Tsuchihara K, et

al: International harmonization of provisional diagnostic criteria

for ERBB2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer allowing for

screening by next-generation sequencing panel. JCO Precis Oncol.

4:6–19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Shimada Y, Yagi R, Kameyama H, Nagahashi

M, Ichikawa H, Tajima Y, Okamura T, Nakano M, Nakano M, Sato Y, et

al: Utility of comprehensive genomic sequencing for detecting

HER2-positive colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 66:1–9. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Siravegna G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Nagy RJ,

Raghav K, Odegaard JI, Lanman RB, Trusolino L, Marsoni S, Siena S

and Bardelli A: Plasma HER2 (ERBB2) copy number predicts response

to HER2-targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 25:3046–3053. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Takegawa N, Yonesaka K, Sakai K, Ueda H,

Watanabe S, Nonagase Y, Okuno T, Takeda M, Maenishi O, Tsurutani J,

et al: HER2 genomic amplification in circulating tumor DNA from

patients with cetuximab-resistant colorectal cancer. Oncotarget.

7:3453–3460. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Singh H, Kang A, Bloudek L, Hsu LI,

Corinna Palanca-Wessels M, Stecher M, Siadak M and Ng K: Systematic

literature review and meta-analysis of HER2 amplification,

overexpression, and positivity in colorectal cancer. JNCI Cancer

Spectr. 8:pkad0822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Benson AB, Venook AP, Adam M, Chang G,

Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen SA, Cooper HS, Deming D, Garrido-Laguna

I, et al: Colon cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical practice

guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 22:e2400292024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A,

Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T,

et al: Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus

chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric

or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): A phase 3,

open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 376:687–697. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van

Grieken NC and Lordick F: Gastric cancer. Lancet. 396:635–648.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Chao J,

Cooke D, Corvera C, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Fanta P, et al:

Gastric cancer, version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines

in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 20:167–192. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang FH, Zhang XT, Tang L, Wu Q, Cai MY,

Li YF, Qu XJ, Qiu H, Zhang YJ, Ying JE, et al: The Chinese society

of clinical oncology (CSCO): Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis

and treatment of gastric cancer, 2023. Cancer Commun (Lond).

44:127–172. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Nakamura Y, Sawada K, Fujii S and Yoshino

T: HER2-targeted therapy should be shifted towards an earlier line

for patients with anti-EGFR-therapy naïve, HER2-amplified

metastatic colorectal cancer. ESMO Open. 4:e0005302019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Sartore-Bianchi A, Trusolino L, Martino C,

Bencardino K, Lonardi S, Bergamo F, Zagonel V, Leone F, Depetris I,

Martinelli E, et al: Dual-targeted therapy with trastuzumab and

lapatinib in treatment-refractory, KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type,

HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer (HERACLES): A

proof-of-concept, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 17:738–746. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sartore-Bianchi A, Lonardi S, Martino C,

Fenocchio E, Tosi F, Ghezzi S, Leone F, Bergamo F, Zagonel V,

Ciardiello F, et al: Pertuzumab and trastuzumab emtansine in

patients with HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer: The

phase II HERACLES-B trial. ESMO Open. 5:e0009112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Siena S, Di Bartolomeo M, Raghav K,

Masuishi T, Loupakis F, Kawakami H, Yamaguchi K, Nishina T, Fakih

M, Elez E, et al: Trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201) in patients with

HER2-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer (DESTINY-CRC01): A

multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 22:779–789.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Raghav K, Siena S, Takashima A, Kato T,

Van den Eynde M, Pietrantonio F, Komatsu Y, Kawakami H, Peeters M,

Andre T, et al: Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with

HER2-positive advanced colorectal cancer (DESTINY-CRC02): Primary

results from a multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 25:1147–1162. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Long HD, Lin YE, Zhang JJ, Zhong WZ and

Zheng RN: Risk of congestive heart failure in early breast cancer

patients undergoing adjuvant treatment with trastuzumab: A

meta-analysis. Oncologist. 21:547–554. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Suter TM and Ewer MS: Cancer drugs and the

heart: Importance and management. Eur Heart J. 34:1102–1111. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Swain SM, Nishino M, Lancaster LH, Li BT,

Nicholson AG, Bartholmai BJ, Naidoo J, Schumacher-Wulf E, Shitara

K, Tsurutani J, et al: Multidisciplinary clinical guidance on

trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd)-related interstitial lung

disease/pneumonitis-Focus on proactive monitoring, diagnosis, and

management. Cancer Treat Rev. 106:1023782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, Carver

J, Constine LS, Denduluri N, Dent S, Douglas PS, Durand JB, Ewer M,

et al: Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in

survivors of adult cancers: American society of clinical oncology

clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 35:893–911. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J,

Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, Anderson B, Bailey J,

Burstein HJ, et al: Breast cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

22:331–357. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, Park YH, Kim

SB, Tamura K, Andre F, Iwata H, Ito Y, Tsurutani J, et al:

Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast

cancer. N Engl J Med. 382:610–621. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Shitara K, Bang YJ, Iwasa S, Sugimoto N,

Ryu MH, Sakai D, Chung HC, Kawakami H, Yabusaki H, Lee J, et al:

Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive gastric

cancer. N Engl J Med. 382:2419–2430. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Edoardo C and Giuseppe C:

Trastuzumab-deruxtecan in solid tumors with HER2 alterations: From

early phase development to the first agnostic approval of an

antibody-drug conjugate. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 33:851–865.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Gao M, Jiang T, Li P, Zhang J, Xu K and

Ren T: Efficacy and safety of HER2-targeted inhibitors for

metastatic colorectal cancer with HER2-amplified: A meta-analysis.

Pharmacol Res. 182:1063302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Siravegna G, Lazzari L, Crisafulli G,

Sartore-Bianchi A, Mussolin B, Cassingena A, Martino C, Lanman RB,

Nagy RJ, Fairclough S, et al: Radiologic and genomic evolution of

individual metastases during HER2 blockade in colorectal cancer.

Cancer Cell. 34:148–162.e7. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang N, Cao Y, Si C, Shao P, Su G, Wang K,

Bao J and Yang L: Emerging role of ERBB2 in targeted therapy for

metastatic colorectal cancer: Signaling pathways to therapeutic

strategies. Cancers (Basel). 14:51602022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Lazzari L, Corti G, Picco G, Isella C,

Montone M, Arcella P, Durinikova E, Zanella ER, Novara L, Barbosa

F, et al: Patient-derived xenografts and matched cell lines

identify pharmacogenomic vulnerabilities in colorectal cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 25:6243–6259. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|