Introduction

Sarcopenia is an age-related syndrome characterized

by a progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass,

strength and function. It is associated with various adverse

clinical outcomes, including fracture, falls and mortality

(1–3). Sarcopenia is particularly prevalent

among elderly patients with cancer (4,5) and

can occur across all types of cancer. Studies indicate that cancer

patients with low skeletal muscle mass during treatment face

increased risks of mortality, cancer recurrence and lower quality

of life (6–8). A systematic meta-analysis of 39

studies involving 8,966 cancer patients revealed an overall pooled

sarcopenia prevalence of 42% [95% confidence interval (CI)

0.36–0.48; P<0.001], with substantial heterogeneity across

cancer subtypes (8). Consistent

with these findings, a review revealed a particularly high

prevalence of sarcopenia (approaching 70%) in patients with

esophageal, gastrointestinal, lung, head and neck malignancies,

compared with a moderate prevalence (~50%) in those with breast,

renal cell and hematologic cancers (9). These tumor-specific prevalence

patterns exhibited correlations with disease stage, progression

kinetics and the severity of nutritional and absorptive

dysfunction. Although the pathogenesis of sarcopenia is not well

understood, early identification of at-risk patients and timely

intervention can markedly reduce the risk of adverse clinical

outcomes.

The diagnosis of sarcopenia requires assessing

muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance (10). The assessment of muscle mass is a

critical component in the clinical diagnosis of sarcopenia

(1,11). Currently, the measurement of the

cross-sectional area (CSA) of the third lumbar vertebra (L3) using

computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is

considered a reliable method for assessing muscle mass. However,

taking into account the expense, convenience, radiation exposure

and equipment availability, various alternative methods have been

developed, such as calf circumference (CC), mid-upper arm

circumference and surrogate vertebral measurements. The present

review summarized current methods for measuring skeletal muscle

mass, aiming to early identify potential sarcopenia cases and

facilitate timely intervention.

Methodology

Literature search strategy

A systematic literature search was performed across

three principal databases: PubMed/Medline (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), Web of Science

(https://webofscience.clarivate.cn)

and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, http://www.cnki.net), between January 2010 and

February 2024. The search strategy used Medical Subject Headings

(MeSH) terminology with Boolean operators, structured as

follows:

Pathology Concepts: sarcopenia OR ‘skeletal muscle’

OR ‘muscle wasting’ OR ‘muscle atrophy’ OR ‘body composition’ OR

‘muscle mass’ OR ‘cachexia’ OR ‘muscle weakness’

Measuring Methods: ‘calf circumference (CC)’ OR

‘mid-arm muscle circumference (MAMC)’ OR ‘Yubi-wakka test’ OR

‘bioimpedance analysis (BIA)’ OR ‘computed tomography (CT)’ OR

‘magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)’ OR ‘dual-energy X-ray

absorptiometry (DXA)’ OR ‘ultrasound (US)’

The search syntax employed Boolean AND operators

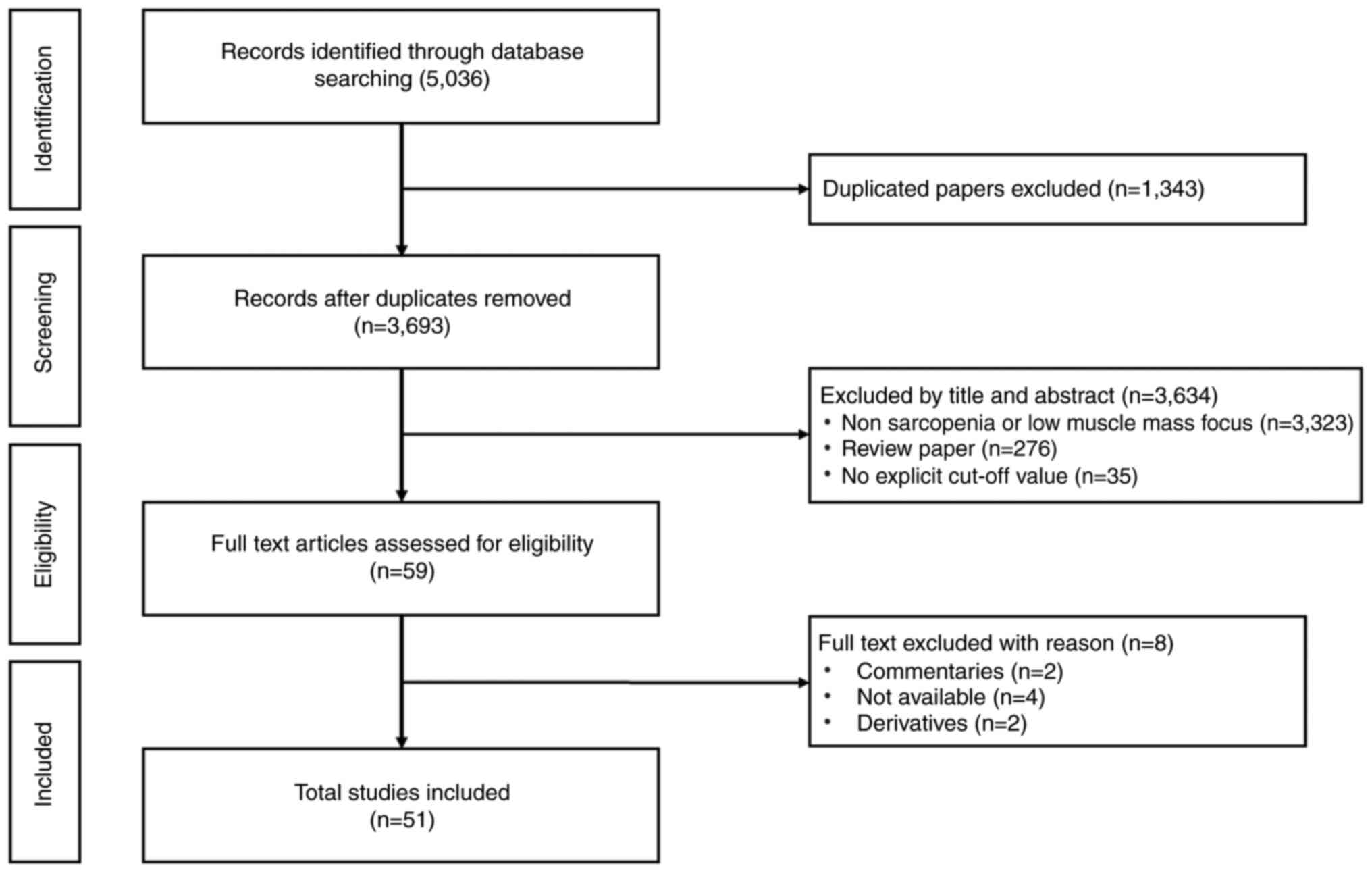

between these two conceptual groups. The study selection workflow

is schematically presented in Fig.

1.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Eligible studies met the following criteria:

Investigation of skeletal muscle mass assessment in sarcopenia

populations, with particular emphasis on cancer patients or

geriatric cohorts; employment of at least one validated measurement

modality for muscle mass evaluation, including, but not limited to,

anthropometric measurements, medical imaging techniques

(CT/MRI/DXA), or BIA; and peer-reviewed original research articles

published in English or Chinese.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded based on the following

considerations: Case reports, conference abstracts, commentaries,

or non-peer-reviewed publications; articles lacking standardized

diagnostic thresholds for low muscle mass determination; duplicate

publications or studies with substantial cohort overlap.

Study selection and flowchart

The literature screening process followed the PRISMA

guidelines (Fig. 1). Initial

searches identified 5,036 records. After removing duplicates

(n=1,343), 3,693 titles/abstracts were screened. Of these, 3,323

were excluded for irrelevance (non-sarcopenia or low muscle mass

focus). A full-text review of 276 articles led to the exclusion of

142 studies (due to insufficient data or non-quantitative methods).

Ultimately, 51 studies were included for the present review.

Data extraction

A total of two independent reviewers extracted data

using a standardized form, including: Study characteristics

(author, year, design); population (sample size, age, cancer type);

muscle mass assessment methods and cut-off values.

Anthropometry

Calf circumference (CC)

CC serves as a straightforward and convenient

indicator for assessing muscle mass, playing a crucial role in

determining sarcopenia cut-off values (12–14).

The Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) 2019 consensus

updated the diagnosis criteria for sarcopenia and recommended CC as

an effective screening tool in community (15–17).

Compared with commonly used methods for assessing muscle mass, CC

shows a positive association with muscle mass measured by BIA and

DXA, regardless of age or body fat percentage (18). Özcan et al (19) reported a positive association

between CC and low muscle mass in patients receiving maintenance

hemodialysis. Numerous studies have investigated the relationship

between CC and low muscle mass, establishing frequently utilized

cut-off values of <34 cm for males and <33 cm for females, as

detailed in Table I.

| Table I.Summary of research on CC cut-off

values for predicting low skeletal muscle mass. |

Table I.

Summary of research on CC cut-off

values for predicting low skeletal muscle mass.

| First author/s,

year | Population | Country/Region | Position | Comparing | Criteria for

cut-off point | Cut-off for CC

(cm) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Champaiboon et

al, 2023 | 6,404 older adults

(≥60 years) | Thailand | Sitting | BIA | AWGS | ♀<33, ♂<34

BMI ≥25:♀<34, ♂<35 older-old adults ≥75 years: ♀<33,

♂<34 | (13) |

| Fernandes et

al, 2022 | 796 older adults

(≥60 years) | Southeast region of

Brazil | Standing | GAMs | WHO (1995) Physical

Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. WHO technical

report series; 854 Geneva, Switzerland | <34.5

(mortality) | (81) |

| Gonzalez et

al, 2021 | 3,104 participants

aged 18–39 years and with normal BMI (18.5–24.9) | US population | Siting | - | 1 and 2 SDs below

the mean | Moderately low

values ♂ ≤34, ♀ ≤33 severely low CC values: ♂≤32, ♀≤ 31 adjusted

BMI: adding 4 cm (BMI <18.5) or subtracting 3,7, or 12 cm (BMI

25–29, 30–39, and ≥40, respectively) | (12) |

| Xu et al,

2020 | 7,311 cases of

Chinese elderly hospitalized population aged >70 years | China | Supine | - | GLIM Criteria | ♂≤29.6, ♂≤27.5 | (20) |

| Kawakami et

al, 2020 | 1,239 adults ≥40

years | Japan | Standing | DEXA/BIA | AWGS | ♂<35 (BIA)/36

(DXA), ♀<33 (BIA)/34 (DXA) | (18) |

| Kim et al,

2018 | 657 older aged

(70–84 years) | Koreans | Standing | DXEA | AWGS | ♂<35, ♀<33 in

community-dwelling Korean elders | (64) |

| Pagotto et

al, 2018 | 132 elderly

people | Brazil | Standing | DEXA | LMM: ♂:7.26

kg/m2, ♀5.45 kg/m2 | ♂<34,

♀<33 | (82) |

| Maeda et al,

2017 | 1,164 hospitalized,

elderly adults | Japan | Supine | BIA | AWGS | ♀≤ 29, ♂≤30 | (83) |

| Barbosa-Silva et

al, 2016 | 1,291

community-dwelling elderly aged 60 y or over | Brazil | Standing | DEXA | EWGSOP2 | ♂≤34, ♀≤33 | (69) |

| Kawakami et

al, 2015 | 40~89 y adults | Japan | Standing | DEXA | AWGS | ♂<34,

♀<33 | (84) |

Xu et al conducted two consecutive studies

involving 7,311 hospitalized elderly patients aged >70 years in

China, using a prospective multi-center database established by the

authors. In the first study, the critical value of CC was

determined using the receiver operating characteristic curve

method, with in-hospital mortality as the primary outcome. This

value was further validated using clinical and financial metrics.

In the second study, three screening tools, NRS 2002, NA-SF and

MUST, were employed for risk assessment. Malnutrition was diagnosed

based on the GLIM criteria, incorporating the newly identified CC

values. The optimal cut-off for CC was determined to be 29.6 cm for

men and 27.5 cm for women (20).

The measurement of CC can be influenced by body type

and positioning. Studies have shown that CC tends to be markedly

higher in individuals with sedentary lifestyles (21). Furthermore, CC measurements vary

across regions, populations and levels of physical activity

intensity. These variations lead to differences in CC cut-off

values for predicting low muscle mass. Therefore, it is essential

to consider the effect of body type and positioning when measuring

CC. Additionally, the most suitable criteria for sarcopenia

screening using CC should be explored across diverse countries,

regions and populations.

Mid-arm muscle circumference

(MAMC)

A study assessed muscle mass in aging individuals

using MAMC within the community, suggesting MAMC as a valid tool

for evaluating nutrition and muscle mass in elderly adults

(22). Carnevale et al

(23) compared DXA and MAMC for

muscle mass assessment, showing that MAMC is a practical screening

tool for elderly patients and more effective in detecting low

muscle mass. Gort-van Dijk et al (24) conclude that MAMC is more specific

but less sensitive for assessing muscle mass. Despite these

considerations, the convenience of MAMC makes it a recommended tool

for screening decreased muscle mass in older populations (24). Notably, MAMC may be less suitable

for subjects with edema (lymphedema or generalized extreme edema)

or extreme obesity.

The cut-off values for determining low muscle mass

using MAMC vary across studies and populations. Carnevale et

al (23) established cut-off

values of <11.0 cm for males and <10.3 cm for females in

healthy young individuals. For older adults, the cut-offs were

<22.3 cm for males and <18.6 cm for females. Gort-van Dijk

et al (24) define low

muscle mass as falling below the 10th percentile of MAMC cut-off

values. However, there is no standardized cut-off value for MAMC to

define low muscle mass. Further research is needed to establish its

applicability across different age groups and to determine

appropriate cut-off values.

Yubi-wakka (finger-ring) test

The finger-ring measurement (Yubi-wakka) is a

self-testing tool developed by Tanaka et al (25) in 2018 to assess the risk of

sarcopenia among community-dwelling older adults. Participants

compared the circumference of their own hands with their CC. A

larger CC indicated no sarcopenia risk, while equal measurements

suggested potential early-stage sarcopenia. A smaller CC indicated

sarcopenia risk necessitating further evaluation and intervention.

Tanaka et al (25) verified

the Yubi-wakka test in a study of 1,904 older adults (≥65 years),

finding 53% in the larger CC group, 33% in the equal group and 14%

in the smaller CC group. Multiple-factor analysis revealed that,

compared with the larger CC group, the equal and smaller CC groups

were more likely to develop sarcopenia (OR=2.4, 95% CI 1.4–4.1;

OR=6.6, 95% CI 3.5–13, respectively). Lawongsa et al

(26) replicated these findings in

a study of Thai older adults, affirming the high sensitivity and

specificity of the Yubi-wakka test for sarcopenia risk

identification. At present, the Yubi-wakka test is primarily

validated in Asian populations (27–29).

Further research is needed to explore its applicability and

validity across diverse ethnic groups.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI)

CT and MRI are widely used in clinical practice to

assess muscle mass (30–32). CT can be targeted to show different

body components by setting different thresholds, where the

threshold for muscle tissue is −29~150 Hounsfield units (33,34).

MRI relies on instrument-based marking or manual labeling of muscle

tissue for accurate measurement (30). CT or MRI assessment of muscle mass

usually involves measuring the skeletal muscle CSA from a single

image. This value is then adjusted for height to calculate the

skeletal muscle index (SMI, cm/m2) (35). Therefore, muscle mass measurements

using CT or MRI require both the selection of experienced staff to

circle the muscle area and, more importantly, the selection of

appropriate and typical vertebrae to measure the CSA of the muscle.

In addition to measuring skeletal muscle CSA for MRI, advanced MRI

sequences can also enable the estimation of body composition in

combination with the assessment of muscle mass abnormalities. This

combined approach enhances the diagnostic accuracy of sarcopenia in

aging patients (36). Xiao et

al (35) show that CT-based

diagnosis of sarcopenia can help to predict clinical outcomes and

prognosis in surgical patients and illustrate that CT is intuitive,

rapid and accurate in the diagnosis of sarcopenia. Beyond CSA

measurement, CT can assess muscle steatosis by measuring

intermuscular adipose tissue area or identifying muscle mass loss

(37). Despite their advantages in

sarcopenia diagnosis, CT and MRI are not widely used for screening

due to their high cost, time consumption and ionizing radiation (in

the case of CT) and the need for specialized technical expertise

(35,36).

The third lumbar vertebra (L3)

The third lumbar vertebra (L3) is currently the most

commonly used for measuring the SMI to assess whole-body muscle

mass, given its strong correlation with whole-body musculature

(r=0.86 ~0.94; P<0.001) (38).

This method is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of low

muscle mass and sarcopenia (39).

Prado et al (40) measured

the L3 SMI in patients with respiratory and gastrointestinal tumors

to assess muscle mass. Martin et al (41) defined the cut-off value for

sarcopenia as SMI <52.4 cm2/m2 in men and

SMI <38.5 cm2/m2 in women. The L3 SMI

cut-off values for assessing whole-body muscle mass range from

40.2–55.0 cm2/m2 in men and 30.0–43.23

cm2/m2 in women, respectively, as shown in

Table II.

| Table II.Summary of research on measuring

muscle mass at L3 using computerized tomography. |

Table II.

Summary of research on measuring

muscle mass at L3 using computerized tomography.

| First author/s,

year | Population | Software | Criteria for

cut-off point | Cutoff for Low SMI

(cm2/m2) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Sahin et al,

2023 | 162 stomach cancer

patients, aged ≥18 years, Turkey | 3D Slicer (version

4.10.2) (Slicer) | - | ♂52.4; ♀38.5 | (85) |

| Sealy et al,

2020 | 213 head and neck

cancer patients, the Netherlands | Slice-O-Matic V5.0

(TomoVision) | Tertiles in the

cohort | ♂53.4; ♀43.23 | (86) |

| Van der Kroft et

al, 2020 | 180 patients with

Colorectal cancer, Germany | Slice-O-Matic V5.0

(TomoVision) | At the lowest

tertile | ♂46.6; ♀36.8 | (87) |

| Li et al,

2019 | 153 gastric cancer

patients, China | Slice-O-Matic V5.0

(TomoVision) | Optimum

stratification | ♂40.2; ♀30.0 | (88) |

|

Blauwhoff-Buskermolen et al,

2017 | 241 cancer

patients, aged ≥18 years, the Netherlands | Slice-O-Matic V5.0

(TomoVision) | - | ♂55.0; ♀39.0 | (89) |

By analyzing the relationship between SMI and

prognosis in ovarian cancer patients, Jin et al (42) found significant variability in the

cut-off values for low muscle mass among female patients. Commonly

used SMI cut-off values ranged from 38.5–41.0

cm2/m2, with 38.5 and 41.5

cm2/m2 being the most frequently applied

thresholds. The authors suggested that there was a large

heterogeneity in the cut-off values for low muscle mass,

potentially due to variations in methodology or population

characteristics. As a clinical reference standard for assessing low

SMI, the use of L3 needs further refinement to establish a robust

diagnostic criterion. Considering that most of the patients do not

routinely undergo CT scanning of the abdomen in clinical practice,

performing such examinations solely for sarcopenia diagnosis would

increase radiation exposure and assessment costs. In such case,

researchers have tried to measure the CSA of other non-L3 vertebrae

to evaluate muscle mass (43).

Thus, it may be a cost-effective alternative measurement of

skeletal muscle mass in screening of sarcopenia, improving patient

prognosis without increasing additional economic and radiation

burdens.

The third cervical vertebra (C3)

Patients with head and neck tumors have a higher

risk of developing sarcopenia (44), but abdominal CT scanning is not

routinely performed in this population. Thus, some researchers are

exploring whether the C3 could serve as an alternative for

screening low muscle mass in these patients. This approach could

facilitate timely treatment, such as nutritional support or

physical therapy and improve prognosis.

By measuring C3 and L3 muscle mass with CT in 51

trauma and 52 head and neck tumors patients, Swartz et al

(44) found a strong correlation

between L3 and C3 (r=0.891). The authors demonstrate that it is

feasible to use the head and neck CT to evaluate muscle mass in

head and neck tumors patients. This method also serves as a viable

alternative to abdominal CT for measuring L3 muscle mass. Jung

et al (45) also advocate

the use of C3 CSA measured by head and neck CT to estimate L3

muscle mass in patients with head and neck tumors and predict

overall survival. Meerkerk et al (30) used C3 muscle mass measurements to

predict frailty in patients with head and neck tumors. The authors'

findings showed that low SMI and sarcopenia are associated with

frailty in older patients. Additionally, a retrospective cohort

study has demonstrated a correlation between C3 muscle mass and

prognosis in oral cancer patients, suggesting its potential as an

imaging marker for predicting outcomes (46).

However, some researchers doubt whether the CSA

measured by C3 can accurately predict the CSA of L3. Yoon et

al (34) concluded that in

patients with head and neck tumors complicated with sarcopenia, the

muscle mass measured by C3 did not strongly correlate with that at

L3 (r=0.381). This discrepancy is probably due to the fact that the

sternocleidomastoid muscle at C3 was excluded from the analysis due

to tumor invasion, leading to variability in the results between

studies. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the

feasibility of using C3 as a substitute for L3 in evaluating

systemic muscle mass in patients' head and neck tumors. Key

questions include how to measure C3 muscle mass, which muscles

should be included and correlation between C3 and L3 muscle mass as

well as the determination of a cut-off value for low muscle mass

based on C3.

The fourth thoracic vertebra

(Th4)

The Th4 is commonly used to assess muscle mass in

patients undergoing chest CT scans for lung cancer and breast

cancer. Gronberg et al (47)

compared the concordance between Th4-measured SMI and L3-measured

SMI and showed that there was only moderate concordance between

them (r2=0.51 in men and r2=0.28 in women),

indicating that Th4 cannot yet replace L3 to assess low muscle

mass. Neefjes et al (48)

also explored the use of Th4 for assessing low muscle mass and the

findings suggested that further work is needed to validate the

reliability of Th4 for this purpose. The current studies on the

cut-off value of Th4 for assessing low muscle mass are summarized

in Table III.

| Table III.Summary of research on measuring

muscle mass at Th4 using computerized tomography. |

Table III.

Summary of research on measuring

muscle mass at Th4 using computerized tomography.

| First author/s,

year | Population | Software | Criteria for

cut-off point/muscle area | Cut-off for low SMI

(cm2/m2) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Tao et al,

2023 | 750 NSCLC patients,

China | Simens syngo via

VB20 (Siemens Healthineers) | X-tile

software/bilateral pectoralis major, pectoralis minor muscles | ♂ 18.1; ♀ 14.7 | (90) |

| Sealy et al,

2020 | 213 head and neck

cancer patients, the Netherlands | Slice-O-Matic V5.0

(TomoVision) | Tertiles in the

cohort/Total muscle | ♂69.45; ♀52.88 | (86) |

| Van der Kroft et

al, 2020 | 180 patients with

Colorectal cancer, Germany | Slice-O-Matic V5.0

(TomoVision) | The lowest

tertile/Total muscle | ♂65.2; ♀51.9 | (87) |

|

Blauwhoff-Buskermolen et al,

2017 | 241 cancer

patients, aged ≥18 years, the Netherlands | Slice-O-Matic V5.0

(TomoVision) | -/Total muscle | ♂66.0; ♀51.9 | (89) |

According to the current research results, the

cut-off values of Th4 in evaluating low muscle mass and the muscle

measurement area still are not standardized. Therefore, further

research is needed for the adoption of Th4 instead of L3 to

evaluate low muscle mass.

The twelfth thoracic vertebra

(Th12)

Chest CT scans do not cover the L3 region, as that

would increase both the financial burden and radiation exposure for

patients who only need a chest CT. It is worth exploring how to

diagnose sarcopenia without additional CT scans. Some researchers

have attempted to use Th10, Th12 and other thoracic vertebrae for

muscle mass assessment.

In a study by Matsuyama et al (49) Th12 muscle mass was measured using

chest CT in patients with progressive oral squamous cell carcinoma.

This value was compared with L3 muscle mass and the results showed

that SMI measured at Th12 using chest CT can be used to diagnose

sarcopenia and has predictive value for postoperative outcomes in

these patients. In conclusion, current evidence is insufficient to

support the use of Th10 and Th12 as alternatives to L3 for muscle

mass measurement and more studies are needed.

Masticatory muscle

Masticatory muscles reflect the chewing and

swallowing function of patients and are closely related to their

nutritional status. Studies have shown that the mass of masticatory

muscles is closely related to patients' grip strength, walking

speed and physical activity (50,51).

This suggests that masticatory muscles could serve as a new site

for muscle mass measurement. Hwang et al (52) retrospectively analyzed 314 patients

in emergency department and confirmed a significant association

between masticatory muscle mass and systemic nutritional

biomarkers. These findings suggest that masticatory muscle mass is

a potential indicator of nutritional status, physical activity

levels and trauma-related prognosis (53).

Chang et al (53) attempted to measure the muscle mass

of the masticatory muscles in patients with head and neck cancers

to explore its relationship with L3 muscle mass, specifically at

the level of the mandibular notch. The authors found a strong

correlation between masticatory muscle mass and L3 muscle mass

(r=0.901). The study also suggested that C3 muscle mass

measurements may be unreliable in patients with head and neck

tumors involving lymphatic metastasis or severe muscle tissue

invasion. Thus, measuring masticatory muscle mass might be a useful

alternative. However, it should be noted that the number of studies

on masticatory muscle for assessing low muscle mass is insufficient

to support its validity as an alternative to L3.

Bilateral mid-thigh muscle area

(TMA)

TMA has also been used to assess muscle mass. It

provides more accurate evaluation of overall skeletal muscle mass

and is highly sensitive to changes. The 2019 European Working Group

on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) guideline highlighted that

mid-thigh muscle mass correlates more strongly with whole-body

muscle mass than L1-L5 measurements (10). Tsai et al (54) found a strong correlation between TMA

and abdominal muscle area (AMA) while investigating the

relationship between lower extremity muscle mass and vascular

stenosis in patients with peripheral arterial disease. This

suggests that TMA could be another effective method for assessing

muscle mass and future research in this area is warranted.

Clinical ultrasound (US)

US enables evaluation of muscle echotexture by

detecting variations in intramuscular fat and connective tissue

composition. Recently, the Sarcopenia Group of the European

Geriatric Society published a consensus protocol for the detection

of sarcopenia using ultrasound, including the measurements of CSA,

muscle thickness, echo intensity, muscle wing angle and muscle

bundle length (55). While the

quadriceps remain the most studied muscle group, uncertainty

persists regarding optimal anatomical measurement sites for

assessing total skeletal muscle mass. Perkisas et al

(56) concluded that muscle mass

decreases before the number of muscle fibers is lost, which could

be a reliable indicator of early signs of sarcopenia in the

elderly. Although human errors in the interpretation of ultrasound

results, might affect the formulation of unified diagnostic

criteria, ultrasound still has the potential to become a tool for

early screening and clinical diagnosis of sarcopenia due to its

advantages of being non-invasive, painless, non-ionizing radiation

and low-cost.

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

DXA is currently widely used in body composition

measurement due to its accuracy and repeatability. DXA enables

simultaneous quantification of fat mass, appendicular skeletal

muscle mass (ASM), fat-free mass (FFM) and bone mineral content.

Studies demonstrate strong concordance between DXA-derived

non-fat/adipose tissue measurements and corresponding values

obtained via CT or MRI (1,57). ASMI measured by DXA varied in

different study populations, with cut-off values ranging from 5.86

kg/m2−7.40 kg/m2 in males and from 4.42

kg/m2−5.67 kg/m2 in females (58). Based on available studies, EWGSOP2

has established the cut-off value for DXA to assess low muscle mass

as ASMI <7.0 kg/m2 for males and <5.5

kg/m2 for females (59).

The AWGS has established DXA cut-off values for assessing low

muscle mass as ASMI <7.0 kg/m2 for males and <5.7

kg/m2 for females (60).

Nevertheless, DXA is unable to assess intramuscular

fat infiltration (myosteatosis), which limits muscle quality

evaluation. Furthermore, DXA measurements can be inaccurate due to

variations in body thickness, fluid retention conditions (e.g.,

renal/hepatic dysfunction) and fluctuations in hydration

status.

Bioimpedance analysis (BIA)

BIA is widely used for body composition assessment,

indirectly calculating muscle mass using specific formulas. Cheng

et al (57) demonstrated

that BIA initially overestimates muscle mass but aligns closely

with DXA measurements after adjustment, making it a rapid and

reliable tool for sarcopenia screening. Compared with DXA, BIA is a

simple measurement method with the advantages of being

non-invasive, radiation-free and fast, making it an improved better

choice for muscle mass screening of sarcopenia.

Although the AWGS2019 diagnostic criteria for

sarcopenia define low muscle mass as muscle mass measured by BIA

<7.0 kg/m2 for males and <5.7 kg/m2 for

females (61), there is no

diagnostic criterion for low muscle mass determined by BIA in

EWGSOP2. This may be due to the heterogeneity of low muscle mass

cut-off values among different ethnicities. Therefore, the cut-off

values for low muscle mass range from 7.4 kg/m2−9.31

kg/m2 for males and from 5.14 kg/m2−7.4

kg/m2 for females, as shown in Table IV.

| Table IV.Summary of research on BIA. |

Table IV.

Summary of research on BIA.

| First author/s,

year | Population | BIA instrument | Criteria for

cut-off point | Cut-off for low SMI

(kg/m2) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pineda-Zuluaga

et al, 2023 | 237 people, older

than 60 years, Colombia | Hydra 4200 Xitron

Technologies | −2 SD of the mean

value of Colombia older adults | ♂8.0; ♀6.1 | (91) |

| Bulut et al,

2020 | 1,150 participants,

>60 years old, Turkey | Tanita MC-780U | −2 SD of Turkish

young adults (18 ~40 years old) | ♂8.33; ♀5.7 | (92) |

| Björkman et

al, 2019 | 428 healthy people,

>75 years, Finland | ImpediMed SFB7 | Age-specific median

values | ♂9.31; ♀6.9 | (93) |

| Han et al,

2016 | 878 healthy

volunteers, >65 years, China | InBody 720 | −2 SD of Chinese

young adults (20~40 years old) | ♂7.40; ♀5.14 | (94) |

| Bahat et al,

2016 | 301 participants,

Turkey | Tanita BC 532 | −2 SD of Turkish

young adults (18–39 years old) | ♂9.2; ♀7.4 | (95) |

The use of different evaluation instruments results

in significant differences in cut-off values because different

formulas are used to measure muscle mass. In the future, more

studies should focus on establishing a unified and standardized

instrument to explore the cut-off values for low muscle mass in

different ethnicities, for the purpose of improving the sensitivity

and specificity of sarcopenia screening. In general, BIA is a

convenient and simple tool for measuring muscle mass and can be

used in muscle mass screening for sarcopenia. However, it should be

noted that muscle mass measurements by BIA are susceptible to the

hydration status of patients, leading to inaccurate muscle mass

values. Therefore, BIA is not recommended for patients with

edema.

Discussion

Sarcopenia, a syndrome characterized by progressive

and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass and function, has

gained recognition as a critical determinant of health in older

adults (62). Accurate assessment

of muscle mass is crucial for the diagnosis, monitoring and

management of sarcopenia, markedly influencing clinical

decision-making and patient outcomes (63). Anthropometric measurements such as

CC, mid-upper arm circumference and the Yubi-wakka test, offer

non-invasive, rapid and cost-effective approaches for sarcopenia

screening (15). These methods are

particularly valuable in both in community and hospital settings,

enabling widespread screening initiatives (61). However, while the Yubi-wakka test

shows good applicability in Asian populations, further validation

in diverse ethnic groups is needed to ensure its global

applicability (64). BIA is a

widely used tool for assessing body composition, including muscle

mass, owing to its ease of use and non-invasive nature. However,

variability in BIA devices and methodologies can affect the

accuracy and reliability of measurements, highlighting the need for

standardization in sarcopenia diagnosis (65,66).

Cut-off values for BIA in sarcopenia screening exhibit variability,

with suggested thresholds being <7.0 kg/m2 for men

and <5.5 or 5.7 kg/m2 for women (61). The EWGSOP recommends DXA for muscle

mass assessment (39), due to its

precision and ability to evaluate regional lean mass. However, its

high cost and limited availability may restrict its use in routine

clinical practice (67). The

cut-off values for DXA in sarcopenia diagnosis are <7.0

kg/m2 for men and <5.4 kg/m2 for women.

However, these thresholds may not be universally applicable across

diverse populations (68). Imaging

techniques such as CT and MRI provide detailed visualization of

muscle mass and quality, making them valuable tools in sarcopenia

research and clinical practice (31). The use of skeletal muscle mass

measured at the L3 level serves as a common reference standard.

However, the lack of standardized cut-off values and variability in

the selection of vertebral levels and muscles for assessment pose

significant challenges (69).

Future research should prioritize the establishment of standardized

criteria to enable more consistent diagnosis and monitoring of

sarcopenia (70–72). US is emerging as a promising tool

for sarcopenia assessment, offering a non-invasive, portable and

repeatable method to evaluate muscle mass and quality (25). Its potential for real-time imaging

and the absence of radiation exposure represent significant

advantages. However, US results are operator-dependent and further

research is required to establish its reliability and validity in

sarcopenia assessment (55).

Despite the variety of available methods, several challenges

persist, such as the lack of standardized cut-off values across

methodologies, the reliance on equipment that may not be

universally accessible and the dependence on techniques requiring

specialized training (63). The

comparative merits and drawbacks of these measurement approaches

are detailed in Table V.

Additionally, the heterogeneity in sarcopenia presentation across

diverse populations underscores the need for more inclusive

research to ensure diagnostic accuracy (73). Given the limitations of individual

methods, a combined approach may offer a more comprehensive

assessment of sarcopenia. Integrating anthropometric measures with

BIA or imaging techniques can yield a more accurate representation

of muscle mass and function (58,74).

Future research should explore the integration of these methods to

improve diagnostic accuracy and enhance clinical applicability. The

field of sarcopenia assessment is rapidly evolving, necessitating

innovative approaches that balance accuracy with practicality for

widespread implementation. The development of emerging

technologies, such as advanced imaging software and machine

learning algorithms, holds promise for delivering more precise and

accessible methods for sarcopenia diagnosis (75). Furthermore, incorporation of

biomarkers and genetic factors into the assessment framework could

enable a more comprehensive understanding of sarcopenia (76).

| Table V.Comparative analysis of body

composition assessment modalities for sarcopenia evaluation. |

Table V.

Comparative analysis of body

composition assessment modalities for sarcopenia evaluation.

| Methods | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| CT | • Quantitative gold

standard | • Radiation

burden |

|

| • Widely

available | • Threshold

variability |

|

| • Validated

prognostic value | • Cost prohibitive

for serial monitoring |

| MRI | • Superior soft

tissue resolution | • Limited

availability |

|

| • Multi-parametric

tissue characterization | • Lengthy

acquisition |

|

| • No ionizing

radiation | • Motion

artifacts |

| DXA | • Established

reference ranges | • Hydration status

confounding |

|

| • Low radiation

dose | • Regional

variability |

|

| • Rapid

acquisition | • Limited quality

assessment |

|

| • Widely

available |

|

| US | • Point-of-care

application | • Operator

expertise required |

|

| • Dynamic muscle

evaluation | • Limited

reproducibility |

|

| •

Cost-effective | • Depth

constraints |

| Anthropometry | • Universally

accessible | • Insensitive to

early changes |

|

| • Minimal training

required | • Body habitus

confounding |

|

| • Low-cost

screening | • Qualitative

only |

Sarcopenia is a prevalent condition among cancer

patients, with significant implications for clinical outcomes.

Current evidence establishes CT as the most widely adopted and

clinically validated modality for body composition assessment in

this population. The systematic review by McGovern et al

(77) highlights that low SMI and

skeletal muscle density, as assessed by CT, are prevalent across

malignancies, independent of disease stage. However, the review

underscores the lack of standardized thresholds for defining

sarcopenia in oncology, with studies employing heterogeneous

cut-offs. By contrast, Ubachs et al (78) provide compelling evidence for the

prognostic value of CT-based assessments, demonstrating significant

associations between both SMI [P=0.02; hazard ratio (HR): 1.17; 95%

CI: 1.03–1.33] and skeletal muscle radiation attenuation

(P<0.001; HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.08–1.20) with overall survival.

The study highlights the particular clinical utility of CT in

ovarian cancer, where ascites-related weight masking renders

anthropometric measurements unreliable for nutritional assessment.

The applicability of sarcopenia assessment varies markedly across

cancer types, with methodology selection often dictated by

anatomical considerations. Notably, studies in head and neck

cancers predominantly employ cervical skeletal muscle index (C3

SMI) measurements, whereas investigations of gastrointestinal

malignancies typically utilize lumbar skeletal muscle index (L3

SMI), reflecting site-specific clinical relevance (8). Other tools such as DXA (limited by

hydration status), MRI (costly) and US (operator-dependent) are

less robust for cancer-specific prognostication. Anthropometrics

(such as CC) are accessible but lack precision. A meta-analysis by

Zhang et al (8)

systematically compared prognostic capabilities across skeletal

muscle quantification methods, revealing that while L3 SMI remains

the preferred modality for cross-cancer applications due to its

standardized implementation, C3 SMI emerges as particularly

predictive of mortality outcomes in head and neck malignancies; a

finding that aligns with the anatomical and pathophysiological

characteristics of these tumors. However, C3 SMI limited

application in non-head/neck cancers restricts broader

generalizability. Future research should prioritize tumor-specific

diagnostic thresholds and multimodal assessment frameworks to

optimize SMI assessment in cancer patients.

Normative values and cut-off criteria for muscle

mass exhibit variations across ethnicities, sexes and age groups.

However, a number of countries, including China, currently lack

clinically validated cut-off standards and population-specific

reference values derived from rigorous methodologies. To address

this gap, future research is needed to determine benchmarks across

diverse populations using advanced technologies, large-scale

studies and high-quality methodologies. Future research should

define clinically supported indices, such as FFM index in different

ethnic groups, to determine sex- and age-specific normal ranges and

clinically supported indices for diagnosing reduced muscle

mass.

The present review presented a systematic evaluation

framework that innovatively combined both conventional and emerging

assessment modalities, thereby offering distinct methodological

advantages compared with previous works by Muraki (methodological

analysis) (79) and Li et al

(technical imaging review) (80).

The present review broadened the assessment paradigm by

incorporating low-cost clinical tools including anthropometric

measurements (such as CC) and validated self-assessment methods

(such as the Yubi-wakka test), implemented through standardized

diagnostic criteria (AWGS 2019) to enhance clinical utility across

diverse settings without compromising diagnostic accuracy.

Furthermore, the present review assessed multi-modal strategies,

such as combining BIA with anthropometry, to improve accuracy while

addressing limitations such as hydration effects or positioning

errors, often overlooked in prior studies, with particular emphasis

on population-specific validation for Asian cohorts to address

diagnostic heterogeneity and technical rigor. Notably, the present

review bridged research and practice by advocating harmonized

protocols that balance gold-standard imaging (such as L3-CT) with

scalable tools (such as US and CC), while also exploring emerging

technologies such as machine learning for muscle segmentation. By

comprehensively integrating multiple assessment approaches, our

study extends the current evaluative paradigm to improve clinical

utility.

Conclusion

While current methods provide valuable tools for

both clinical practice and research, there remains a critical need

for further standardization, validation and innovation. Future

research should focus on the development and validation of

assessment methods that are accessible, reliable and applicable

across diverse populations, improving the care and outcomes for

individuals affected by sarcopenia.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Hunan Province (grant no. 2023JJ40907), the Natural

Science Foundation of Changsha (grant no. kq2208355) and the Hunan

Cancer Hospital Climb Plan (grant no. IIT2021005).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JH and CT conceived the study and contributed to the

critical revision of the manuscript. WW and ML designed the study,

collected data, prepared tables, drafted the original draft and

conducted the review and editing. QZ contributed to manuscript

drafting, prepared the tables, and reviewed the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cruz-Jentoft AJ and Sayer AA: Sarcopenia.

Lancet. 393:2636–2646. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Damluji AA, Alfaraidhy M, AlHajri N,

Rohant NN, Kumar M, Al Malouf C, Bahrainy S, Ji Kwak M, Batchelor

WB, Forman DE, et al: Sarcopenia and cardiovascular diseases.

Circulation. 147:1534–1553. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sayer AA and Cruz-Jentoft A: Sarcopenia

definition, diagnosis and treatment: Consensus is growing. Age and

ageing. 51:afac2202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhang FM, Wu HF, Shi HP, Yu Z and Zhuang

CL: Sarcopenia and malignancies: Epidemiology, clinical

classification and implications. Ageing Res Rev. 91:1020572023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fang P, Zhou J, Xiao X, Yang Y, Luan S,

Liang Z, Li X, Zhang H, Shang Q, Zeng X and Yuan Y: The prognostic

value of sarcopenia in oesophageal cancer: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14:3–16. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chang KV, Chen JD, Wu WT, Huang KC, Hsu CT

and Han DS: Association between loss of skeletal muscle mass and

mortality and tumor recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma: A

systematic review and Meta-analysis. Liver Cancer. 7:90–103. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nipp RD, Fuchs G, El-Jawahri A, Mario J,

Troschel FM, Greer JA, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Kambadakone A,

Hong TS, et al: Sarcopenia is associated with quality of life and

depression in patients with advanced cancer. Oncologist. 23:97–104.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zhan Y, Pan Z, Liu Q and

Yuan W: Sarcopenia is a prognostic factor of adverse effects and

mortality in patients with tumour: A systematic review and

Meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15:2295–2310. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yuan S and Larsson SC: Epidemiology of

sarcopenia: Prevalence, risk factors, and consequences. Metabolism.

144:1555332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie

Y, Bruyere O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA,

et al: Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and

diagnosis. Age Ageing. 48:6012019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Dent E, Woo J, Scott D and Hoogendijk EO:

Sarcopenia measurement in research and clinical practice. Eur J

Intern Med. 90:1–9. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gonzalez MC, Mehrnezhad A, Razaviarab N,

Barbosa-Silva TG and Heymsfield SB: Calf circumference: Cutoff

values from the NHANES 1999–2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 113:1679–1687.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Champaiboon J, Petchlorlian A, Manasvanich

BA, Ubonsutvanich N, Jitpugdee W, Kittiskulnam P, Wongwatthananart

S, Menorngwa Y, Pornsalnuwat S and Praditpornsilpa K: Calf

circumference as a screening tool for low skeletal muscle mass:

Cut-off values in independent Thai older adults. BMC Geriatr.

23:8262023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kiss CM, Bertschi D, Beerli N, Berres M,

Kressig RW and Fischer AM: Calf circumference as a surrogate

indicator for detecting low muscle mass in hospitalized geriatric

patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 36:252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW,

Chou MY, Iijima K, Jang HC, Kang L, Kim M, Kim S, et al: Asian

working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia

diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 21:300–307.e2. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Oh MH, Shin HE, Kim KS, Won CW and Kim M:

Combinations of sarcopenia diagnostic criteria by asian working

group of sarcopenia (AWGS) 2019 guideline and incident adverse

health outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Med Dir

Assoc. 24:1185–1192. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sri-On J, Fusakul Y, Kredarunsooksree T,

Paksopis T and Ruangsiri R: The prevalence and risk factors of

sarcopenia among Thai community-dwelling older adults as defined by

the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS-2019) criteria: A

cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 22:7862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kawakami R, Miyachi M, Sawada SS, Torii S,

Midorikawa T, Tanisawa K, Ito T, Usui C, Ishii K, Suzuki K, et al:

Cut-offs for calf circumference as a screening tool for low muscle

mass: WASEDA's Health study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 20:943–950.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Özcan B, Güner M, Ceylan S, Öztürk Y,

Girgin S, Okyar Baş A, Koca M, Balcı C, Doğu BB, Cankurtaran M, et

al: Calf circumference predicts sarcopenia in maintenance

hemodialysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 39:193–201. 2024.

|

|

20

|

Xu JY, Zhu MW, Zhang H, Li L, Tang PX,

Chen W and Wei JM: A Cross-Sectional study of GLIM-defined

malnutrition based on new validated calf circumference Cut-off

values and different screening tools in hospitalised patients over

70 years old. J Nutr Health Aging. 24:832–838. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rigby L, Frey M, Alexander KL and De

Carvalho D: Monitoring calf circumference: Changes during prolonged

constrained sitting. Ergonomics. 65:631–641. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Landi F, Russo A, Liperoti R, Pahor M,

Tosato M, Capoluongo E, Bernabei R and Onder G: Midarm muscle

circumference, physical performance and mortality: Results from the

aging and longevity study in the Sirente geographic area (ilSIRENTE

study). Clin Nutr. 29:441–447. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Carnevale V, Castriotta V, Piscitelli PA,

Nieddu L, Mattera M, Guglielmi G and Scillitani A: Assessment of

skeletal muscle mass in older people: Comparison between 2

Anthropometry-based methods and Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J

Am Med Dir Assoc. 19:793–796. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gort-van Dijk D, Weerink LBM, Milovanovic

M, Haveman JW, Hemmer PHJ, Dijkstra G, Lindeboom R and

Campmans-Kuijpers MJE: Bioelectrical impedance analysis and

Mid-upper arm muscle circumference can be used to detect low muscle

mass in clinical practice. Nutrients. 13:23502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tanaka T, Takahashi K, Akishita M, Tsuji T

and Iijima K: ‘Yubi-wakka’ (finger-ring) test: A practical

self-screening method for sarcopenia, and a predictor of disability

and mortality among Japanese community-dwelling older adults.

Geriatr Gerontol Int. 18:224–232. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lawongsa K, Srisuwan P, Tejavanija S and

Gesakomol K: Sensitivity and specificity of Yubi-wakka

(finger-ring) screening method for sarcopenia among older Thai

adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 24:263–268. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Hiraoka A, Izumoto H, Ueki H, Yoshino T,

Aibiki T, Okudaira T, Yamago H, Suga Y, Iwasaki R, Tomida H, et al:

Easy surveillance of muscle volume decline in chronic liver disease

patients using finger-circle (yubi-wakka) test. J Cachexia

Sarcopenia Muscle. 10:347–354. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hiraoka A, Nagamatsu K, Izumoto H, Yoshino

T, Adachi T, Tsuruta M, Aibiki T, Okudaira T, Yamago H, Suga Y, et

al: SARC-F combined with a simple tool for assessment of muscle

abnormalities in outpatients with chronic liver disease. Hepatol

Res. 50:502–511. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Nishikawa H, Yoh K, Enomoto H, Nishimura

T, Nishiguchi S and Iijima H: Clinical impact of the finger-circle

test in patients with liver diseases. Hepatol Res. 51:603–613.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Meerkerk CDA, Chargi N, de Jong PA, van

den Bos F and de Bree R: Low skeletal muscle mass predicts frailty

in elderly head and neck cancer patients. Eur Arch

Otorhinolaryngol. 279:967–977. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Albano D, Messina C, Vitale J and

Sconfienza LM: Imaging of sarcopenia: Old evidence and new

insights. Eur Radiol. 30:2199–2208. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

O'Brien ME, Zou RH, Hyre N, Leader JK,

Fuhrman CR, Sciurba FC, Nouraie M and Bon J: CT pectoralis muscle

area is associated with DXA lean mass and correlates with emphysema

progression in a Tobacco-exposed cohort. Thorax. 78:394–401. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Huang W, Tan P, Zhang H, Li Z, Lin H, Wu

Y, Du Q, Wu Q, Cheng J, Liang Y and Pan Y: Skeletal muscle mass

measurement using Cone-beam computed tomography in patients with

head and neck cancer. Front Oncol. 12:9029662022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Yoon JK, Jang JY, An YS and Lee SJ:

Skeletal muscle mass at C3 may not be a strong predictor for

skeletal muscle mass at L3 in sarcopenic patients with head and

neck cancer. PLoS One. 16:e02548442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xiao Y, Xiao-Yue Z, Yue W, Ruo-Tao L,

Xiang-Jie L, Xing-Yuan W, Qian W, Xiao-Hua Q and Zhen-Yi J: Use of

computed tomography for the diagnosis of surgical sarcopenia:

Review of recent research advances. Nutr Clin Pract. 37:583–593.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Codari M, Zanardo M, di Sabato ME,

Nocerino E, Messina C, Sconfienza LM and Sardanelli F: MRI-derived

biomarkers related to sarcopenia: A systematic review. J Magn Reson

Imaging. 51:1117–1127. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Pishgar F, Shabani M, Quinaglia ACST,

Bluemke DA, Budoff M, Barr RG, Allison MA, Post WS, Lima JAC and

Demehri S: Quantitative analysis of adipose depots by using chest

CT and associations with All-cause mortality in chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease: Longitudinal analysis from MESArthritis

ancillary study. Radiology. 299:703–711. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Mourtzakis M, Prado CM, Lieffers JR,

Reiman T, McCargar LJ and Baracos VE: A practical and precise

approach to quantification of body composition in cancer patients

using computed tomography images acquired during routine care. Appl

Physiol Nutr Metab. 33:997–1006. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tagliafico AS, Bignotti B, Torri L and

Rossi F: Sarcopenia: How to measure, when and why. Radiol Med.

127:228–237. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, Reiman

T, Sawyer MB, Martin L and Baracos VE: Prevalence and clinical

implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours

of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: A population-based

study. Lancet Oncol. 9:629–635. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, Reiman

T, Clandinin MT, McCargar LJ, Murphy R, Ghosh S, Sawyer MB and

Baracos VE: Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle

depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass

index. J Clin Oncol. 31:1539–1547. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Jin Y, Ma X, Yang Z and Zhang N: Low L3

skeletal muscle index associated with the clinicopathological

characteristics and prognosis of ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. J

Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14:697–705. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ufuk F, Herek D and Yuksel D: Diagnosis of

sarcopenia in head and neck computed tomography: Cervical muscle

mass as a strong indicator of sarcopenia. Clin Exp

Otorhinolaryngol. 12:317–324. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Swartz JE, Pothen AJ, Wegner I, Smid EJ,

Swart KM, de Bree R, Leenen LP and Grolman W: Feasibility of using

head and neck CT imaging to assess skeletal muscle mass in head and

neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 62:28–33. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Jung AR, Roh JL, Kim JS, Choi SH, Nam SY

and Kim SY: Efficacy of head and neck computed tomography for

skeletal muscle mass estimation in patients with head and neck

cancer. Oral Oncol. 95:95–99. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Lin SC, Lin YS, Kang BH, Yin CH, Chang KP,

Chi CC, Lin MY, Su HH, Chang TS, She YY, et al: Sarcopenia results

in poor survival rates in oral cavity cancer patients. Clin

Otolaryngol. 45:327–333. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Gronberg BH, Sjoblom B, Wentzel-Larsen T,

Baracos VE, Hjermstad MJ, Aass N, Bremnes RM, Fløtten Ø, Bye A and

Jordhøy M: A comparison of CT based measures of skeletal muscle

mass and density from the Th4 and L3 levels in patients with

advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr. 73:1069–1076.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Neefjes ECW, van den Hurk RM,

Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, van der Vorst M, Becker-Commissaris A, de

van der Schueren MAE, Buffart LM and Verheul HMW: Muscle mass as a

target to reduce fatigue in patients with advanced cancer. J

Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 8:623–629. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Matsuyama R, Maeda K, Yamanaka Y, Ishida

Y, Kato R, Nonogaki T, Shimizu A, Ueshima J, Kazaoka Y, Hayashi T,

et al: Assessing skeletal muscle mass based on the cross-sectional

area of muscles at the 12th thoracic vertebra level on computed

tomography in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral

Oncol. 113:1051262021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Gaszynska E, Godala M, Szatko F and

Gaszynski T: Masseter muscle tension, chewing ability, and selected

parameters of physical fitness in elderly care home residents in

Lodz, Poland. Clin Interv Aging. 9:1197–1203. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yamaguchi K, Tohara H, Hara K, Nakane A,

Yoshimi K, Nakagawa K and Minakuchi S: Factors associated with

masseter muscle quality assessed from ultrasonography in

community-dwelling elderly individuals: A cross-sectional study.

Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 82:128–1232. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hwang Y, Lee YH, Cho DH, Kim M, Lee DS and

Cho HJ: Applicability of the masseter muscle as a nutritional

biomarker. Medicine. 99:e190692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Chang SW, Tsai YH, Hsu CM, Huang EI, Chang

GH, Tsai MS and Tsai YT: Masticatory muscle index for indicating

skeletal muscle mass in patients with head and neck cancer. PLoS

One. 16:e02514552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Tsai PS, Lin DC, Jan YT, Liu YP, Wu TH and

Huang SC: Lower-extremity muscle wasting in patients with

peripheral arterial disease: Quantitative measurement and

evaluation with CT. Eur Radiol. 33:4063–4072. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Perkisas S, Bastijns S, Baudry S, Bauer J,

Beaudart C, Beckwee D, Cruz-Jentoft A, Gasowski J, Hobbelen H and

Jager-Wittenaar H: Application of ultrasound for muscle assessment

in sarcopenia: 2020 SARCUS update. Eur Geriatr Med. 12:45–59. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Perkisas S, Baudry S, Bauer J, Beckwee D,

De Cock AM, Hobbelen H, Jager-Wittenaar H, Kasiukiewicz A, Landi F,

Marco E, et al: Application of ultrasound for muscle assessment in

sarcopenia: Towards standardized measurements. Eur Geriatr Med.

9:739–757. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Cheng KY, Chow SK, Hung VW, Wong CH, Wong

RM, Tsang CS, Kwok T and Cheung WH: Diagnosis of sarcopenia by

evaluating skeletal muscle mass by adjusted bioimpedance analysis

validated with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J Cachexia

Sarcopenia Muscle. 12:2163–2173. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Walowski CO, Braun W, Maisch MJ, Jensen B,

Peine S, Norman K, Müller MJ and Bosy-Westphal A: Reference values

for skeletal muscle mass-current concepts and methodological

considerations. Nutrients. 12:7552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Marini ACB, Perez DRS, Fleuri JA and

Pimentel GD: SARC-F is better correlated with muscle function

indicators than muscle mass in older hemodialysis patients. J Nutr

Health Aging. 24:999–1002. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Lee YA, Kim HN and Song SW: Associations

between hair mineral concentrations and skeletal muscle mass in

korean adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 26:515–520. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Kim M and Won CW: Sarcopenia in Korean

Community-dwelling adults aged 70 years and older: Application of

screening and diagnostic tools from the asian working group for

sarcopenia 2019 update. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 21:752–758. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Janssen I, Baumgartner RN, Ross R,

Rosenberg IH and Roubenoff R: Skeletal muscle cutpoints associated

with elevated physical disability risk in older men and women. Am J

Epidemiol. 159:413–421. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, Bhasin S,

Morley JE, Newman AB, Abellan van Kan G, Andrieu S, Bauer J,

Breuille D, et al: Sarcopenia: An undiagnosed condition in older

adults. Current consensus definition: Prevalence, etiology, and

consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med

Dir Assoc. 12:249–256. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Kim S, Kim M, Lee Y, Kim B, Yoon TY and

Won CW: Calf circumference as a simple screening marker for

diagnosing sarcopenia in older korean adults: The Korean frailty

and aging cohort study (KFACS). J Korean Med Sci. 33:e1512018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Sergi G, De Rui M, Veronese N, Bolzetta F,

Berton L, Carraro S, Bano G, Coin A, Manzato E and Perissinotto E:

Assessing appendicular skeletal muscle mass with bioelectrical

impedance analysis in free-living Caucasian older adults. Clin

Nutr. 34:667–673. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Lee MM, Jebb SA, Oke J and Piernas C:

Reference values for skeletal muscle mass and fat mass measured by

bioelectrical impedance in 390 565 UK adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia

Muscle. 11:487–496. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Harvey NC, Kanis JA, Liu E, Johansson H,

Lorentzon M and McCloskey E: Appendicular lean mass and fracture

risk assessment: Implications for FRAX® and sarcopenia.

Osteoporos Int. 30:537–539. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Yamada Y, Yamada M, Yoshida T, Miyachi M

and Arai H: Validating muscle mass cutoffs of four international

sarcopenia-working groups in Japanese people using DXA and BIA. J

Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 12:1000–1010. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Barbosa-Silva TG, Bielemann RM, Gonzalez

MC and Menezes AM: Prevalence of sarcopenia among

community-dwelling elderly of a medium-sized South American city:

Results of the COMO VAI? study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle.

7:136–143. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wang L, Zhu B, Xue C, Lin H, Zhou F and

Luo Q: A prospective cohort study evaluating impact of sarcopenia

on hospitalization in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal

dialysis. Sci Rep. 14:169262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Benz E, Pinel A, Guillet C, Capel F,

Pereira B, De Antonio M, Pouget M, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Eglseer D,

Topinkova E, et al: Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity and mortality

among older people. JAMA Netw Open. 7:e2436042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Kirk B, Cawthon PM, Arai H, Avila-Funes

JA, Barazzoni R, Bhasin S, Binder EF, Bruyere O, Cederholm T, Chen

LK, et al: The conceptual definition of sarcopenia: Delphi

consensus from the global leadership initiative in sarcopenia

(GLIS). Age Ageing. 53:afae0522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Morley JE, Abbatecola AM, Argiles JM,

Baracos V, Bauer J, Bhasin S, Cederholm T, Coats AJ, Cummings SR,

Evans WJ, et al: Sarcopenia with limited mobility: An international

consensus. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 12:403–449. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Mizuno T, Matsui Y, Tomida M, Suzuki Y,

Ishizuka S, Watanabe T, Takemura M, Nishita Y, Tange C, Shimokata

H, et al: Relationship between quadriceps muscle computed

tomography measurement and motor function, muscle mass, and

sarcopenia diagnosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 14:12593502023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM,

Zuniga C, Arai H, Boirie Y, Chen LK, Fielding RA, Martin FC, Michel

JP, et al: Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing

adults: A systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia

Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing. 43:748–759. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Cawthon PM, Peters KW, Shardell MD, McLean

RR, Dam TT, Kenny AM, Fragala MS, Harris TB, Kiel DP, Guralnik JM,

et al: Cutpoints for low appendicular lean mass that identify older

adults with clinically significant weakness. J Gerontol A Biol Sci

Med Sci. 69:567–575. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

McGovern J, Dolan RD, Horgan PG, Laird BJ

and McMillan DC: Computed tomography-defined low skeletal muscle

index and density in cancer patients: Observations from a

systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 12:1408–1417.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Ubachs J, Ziemons J, Minis-Rutten IJG,

Kruitwagen R, Kleijnen J, Lambrechts S, Olde Damink SWM, Rensen SS

and Van Gorp T: Sarcopenia and ovarian cancer survival: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle.

10:1165–1174. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Muraki I: Muscle mass assessment in

sarcopenia: A narrative review. JMA J. 6:381–386. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Li C, Huang Y, Wang H, Lu J and He B:

Application of imaging methods and the latest progress in

sarcopenia. Chin J Academic Radiol. 7:15–27. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Fernandes DPS, Juvanhol LL, Lozano M and

Ribeiro AQ: Calf circumference is an independent predictor of

mortality in older adults: An approach with generalized additive

models. Nutr Clin Pract. 37:1190–1198. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Pagotto V, Santos KFD, Malaquias SG,

Bachion MM and Silveira EA: Calf circumference: Clinical validation

for evaluation of muscle mass in the elderly. Rev Bras Enferm.

71:322–328. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Maeda K, Koga T, Nasu T, Takaki M and

Akagi J: Predictive accuracy of calf circumference measurements to

detect decreased skeletal muscle mass and European society for

clinical nutrition and metabolism-defined malnutrition in

hospitalized older patients. Ann Nutr Metab. 71:10–15. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Kawakami R, Murakami H, Sanada K, Tanaka

N, Sawada SS, Tabata I, Higuchi M and Miyachi M: Calf circumference

as a surrogate marker of muscle mass for diagnosing sarcopenia in

Japanese men and women. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 15:969–976. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Sahin MEH, Akbas F, Yardimci AH and Sahin

E: The effect of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity on survival in

gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 23:9112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Sealy MJ, Dechaphunkul T, van der Schans

CP, Krijnen WP, Roodenburg JLN, Walker J, Jager-Wittenaar H and

Baracos VE: Low muscle mass is associated with early termination of

chemotherapy related to toxicity in patients with head and neck

cancer. Clin Nutr. 39:501–509. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

van der Kroft G, van Dijk DPJ, Rensen SS,

Van Tiel FH, de Greef B, West M, Ostridge K, Dejong CHC, Neumann UP

and Olde Damink SWM: Low thoracic muscle radiation attenuation is

associated with postoperative pneumonia following partial

hepatectomy for colorectal metastasis. HPB (Oxford). 22:1011–1019.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Li Y, Wang WB, Jiang HG, Dai J, Xia L,

Chen J, Xie CH, Peng J, Liao ZK, Gao Y, et al: Predictive value of

pancreatic dose-volume metrics on sarcopenia rate in gastric cancer

patients treated with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Clin Nutr.

38:1713–1720. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, Langius JAE,

Becker A, Verheul HMW and de van der Schueren MAE: The influence of

different muscle mass measurements on the diagnosis of cancer

cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 8:615–622. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Tao J, Fang J, Chen L, Liang C, Chen B,

Wang Z, Wu Y and Zhang J: Increased adipose tissue is associated

with improved overall survival, independent of skeletal muscle mass

in non-small cell lung cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle.

14:2591–2601. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Pineda-Zuluaga MC, Gonzalez-Correa CH and

Sepulveda-Gallego LE: Cut-off points for low skeletal muscle mass

in older adults: Colombia versus other populations. F1000Res.

11:3042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Bulut EA, Soysal P, Dokuzlar O, Kocyigit

SE, Aydin AE, Yavuz I and Isik AT: Validation of population-based

cutoffs for low muscle mass and strength in a population of Turkish

elderly adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 32:1749–1755. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Bjorkman MP, Pitkala KH, Jyvakorpi S,

Strandberg TE and Tilvis RS: Bioimpedance analysis and physical

functioning as mortality indicators among older sarcopenic people.

Exp Gerontol. 122:42–46. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Han DS, Chang KV, Li CM, Lin YH, Kao TW,

Tsai KS, Wang TG and Yang WS: Skeletal muscle mass adjusted by

height correlated better with muscular functions than that adjusted

by body weight in defining sarcopenia. Sci Rep. 6:194572016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Bahat G, Tufan A, Tufan F, Kilic C,

Akpinar TS, Kose M, Erten N, Karan MA and Cruz-Jentoft AJ: Cut-off

points to identify sarcopenia according to European Working Group

on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition. Clin Nutr.

35:1557–1563. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|