Introduction

Cancer remains a major global health burden and

continues to be a prominent cause of death, with incidence and

mortality rates rising sharply worldwide. Data from the

International Agency for Research on Cancer estimated that there

were 19.3 million new cancer cases and ~10 million cancer-related

deaths globally in 2020. Projections indicate that by 2040, the

global cancer burden will reach 28.4 million cases, an increase of

47% compared with 2020 levels (1,2).

Timely diagnosis and intervention are essential for enhancing both

curative outcomes and 5-year survival rates among patients

(3). However, the absence of

specific clinical manifestations often leads to delayed detection,

with a number of cases identified at advanced stages. Although

advancements in targeted therapy (4) and immunotherapy (5) have extended both the progression-free

survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced

malignancies, these modalities remain limited by narrow therapeutic

windows and do not consistently align with individual clinical

expectations. Immediate efforts are therefore warranted to identify

novel biomarkers capable of enabling early detection, precise

diagnosis and personalized therapeutic strategies, while also

offering predictive value for immunotherapy responsiveness

(6).

Damaged proteins pose a notable threat to cellular

function and viability. To preserve homeostasis, 80–90% of such

aberrant proteins are eliminated via the ubiquitin-proteasome

system (UPS) (7). This degradation

process depends on the sequential action of three enzymes: E1, E2

and E3. The E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme utilizes ATP hydrolysis

to activate ubiquitin by forming a thioester bond between its

cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin. Activated

ubiquitin is subsequently transferred to the E2

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. In coordination with the E3 ubiquitin

ligase, E2 mediates the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to

specific substrate proteins, thereby marking them for recognition

and degradation by the 26S proteasome complex (8). Accumulating evidence indicates that

dysregulation or mutation of UPS components is strongly correlated

with tumorigenesis, positioning the UPS as a central target in

contemporary antitumor therapeutic strategies (9–12).

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 2T (UBE2T), a key

element of the UPS, comprises a conserved UBC fold and a C-terminal

extension. UBE2T has been previously identified as a regulatory

factor in the DNA repair pathway associated with Fanconi anemia

(13). Elevated UBE2T mRNA

expression has been observed in multiple myeloma (14), breast cancer (15), renal cell carcinoma (16), ovarian cancer (9), cervical cancer (17) and retinoblastoma (18) compared with adjacent normal tissues.

Furthermore, increased UBE2T expression has been shown to be

correlated with reduced OS and PFS, indicating its potential role

in tumor progression.

Although accumulating evidence implicates

UBE2T in the pathogenesis of various malignancies,

comprehensive analyses across tumor types remain scarce. The

present study systematically evaluated UBE2T across diverse

cancer types, analyzing gene and protein expression profiles,

clinical phenotypes, survival outcomes, genetic alterations and

drug sensitivity. Additionally, correlations with immune checkpoint

genes, tumor-infiltrating immune cells and immune-related molecular

signatures were explored. Data integration was performed using R

software and datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (19), Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx),

UALCAN, GEPIA2, Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER)2.0, GSCA

and cBioPortal.

Materials and methods

Analysis of UBE2T expression

profiles

The ‘Gene DE’ module of the TIMER 2.0 database

(20) was employed to compare the

UBE2T expression levels between tumor tissues and adjacent

normal tissues across various cancer types. Gene expression

distributions were visualized using box plots, with statistical

significance assessed via the Wilcoxon test and denoted by asterisk

notation. To reinforce and expand these comparisons, the ‘Box

Plots’ feature in GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer–pku.cn/#index) (21), integrating TCGA and GTEx datasets,

was utilized under the thresholds of P<0.01 and

log2FoldChange=1. Protein expression data for UBE2T in

pan-cancer contexts were retrieved from the UALCAN database

(http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html), which supports

TCGA-based cancer data analysis. UBE2T mRNA profiles across

cancer cell lines were sourced from the Cancer Cell Line

Encyclopedia (https://sites.broadinstitute.org/ccle/tools) (22).

Expression levels of UBE2T mRNA and protein

in pancreatic cancer cell lines [PANC1, ASPC, BXPC3, MIA2

(Mia-paca-2), SW1990 and CAPAN1] and normal pancreatic epithelial

cells (HPDE) were assessed via reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR (RT-qPCR) and western blotting. These 7 cell lines were

purchased from American Type Culture Collection and underwent

cultivation in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (cat. no.

C11995500BT; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the

addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. 10099-141 C; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml

streptomycin (cat. no. 15140-122; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). These cell cultures were nurtured under humidified

conditions at 37°C with 5% CO2 utilizing the Thermo

Scientific HERACELL 240i CO2 Incubator (240i; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Western blotting was conducted using

established protocols. Briefly, cell lysates were prepared in Radio

Immunoprecipitation Assay buffer (cat. no. 87787; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with protease (cat. no. 04693124001;

Roche Diagnostics) and phosphatase inhibitors (cat. no. B15001-A;

Selleck Chemicals), followed by incubation on ice for 30 min. The

lysates underwent centrifugation at 13,580 × g for 15 min at 4°C,

and the supernatant was subsequently collected with care. A total

of 20 µg/lane of total protein was separated by 10%

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Post-electrophoresis,

proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes

(0.45 µm; MilliporeSigma). Membranes were incubated in 5% bovine

serum albumin (cat. no. SLBN9354V; MilliporeSigma) to block

non-specific binding sites for 1 h at room temperature. Primary

antibodies specific to UBE2T (1:2,000; cat. no. A6853;

Abclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) and β-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. 4967S;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) were applied and maintained at 4°C

overnight. After primary incubation, membranes were exposed to

horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)

secondary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. no. 7074S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. Signal detection was

achieved using Super ECL Detection Reagent (cat. no. 36208ES60;

Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and imaged with the

Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Chemiluminescence Gel Imaging system (cat. no.

1708280; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Quantification of western

blot bands was performed using Image Lab™ software (Version 6.1;

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

For RT-qPCR, total RNA was extracted by lysing cells

in 1 ml RNAiso Plus reagent (cat. no. 9109; Takara Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.), ensuring complete homogenization. Following

centrifugation (12,000 × g; 4°C; 15 min), the supernatant was

removed and the RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol to improve

purities. RNA extraction and subsequent reverse transcription were

performed according to the protocols in the PrimeScript™ RT Master

Mix (cat. no. RR036A; Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and TB

Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (cat. no. RR820A; Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) kits. qPCR was carried out on the 7500

Real-Time PCR System (cat. no. RR820A; Takara Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) using standard operational guidelines, and performed with the

SYBR® Premix TM kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The conditions for RT-qPCR were as follows: 95°C

for 10 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and 72°C

for 30 sec, and a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. Relative mRNA

expression levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCq

method (23) and normalized against

β-actin as an internal control. The primer sequences used as

follows: UBE2T forward (F), 5′-ATCCCTCAACATCGCAACTGT-3′ and

reverse (R), 5′-CAGCCTCTGGTAGATTATCAAGC-3′; β-actin F,

5′-CGTGCGTGACATTAAGGAGAA-3′ and R, 5′-AGGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAG-3′.

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad

Prism version 9.01 (Dotmatics). Comparisons between each of the six

pancreatic cancer cells and the single control group were performed

using independent samples t-tests, with statistical significance

assessed at a Bonferroni-corrected alpha level of α=0.01 (0.05/5

comparisons). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and

were obtained from three independent repeats. All statistical

analyses were two-sided. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Clinical phenotype analysis and

receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves for diagnosis and

prognostic value

The association between UBE2T expression and

clinical phenotype was assessed using R software (version 4.2.1;

http://www.r-project.org/). The results

were visualized through violin plots and histograms. The diagnostic

and prognostic relevance of UBE2T in tumors was further

evaluated via Xiantao Academic (https://xiantaozi.com).

Survival analysis

Kaplan-Meier plots for OS and disease-free survival

(DFS) across 33 tumor types were generated using the ‘Survival

Analysis’ module in the GEPIA2 database, with ‘Median’ specified as

the group cut-off. Hazard ratios were estimated via the Cox

proportional hazards model, with 95% confidence intervals indicated

by dashed lines and statistical significance defined as

P<0.05. Associations between UBE2T expression and

OS, progression-free interval (PFI) and disease-specific survival

(DSS) in pan-cancer contexts were further examined through Cox

regression. The R packages ‘survival’ and ‘survminer’ were employed

for this analysis, and outcomes were visualized using forest

plots.

Genetic characterization and

alteration analysis

Genomic location, subcellular distribution, protein

tertiary structure and known protein interactions of UBE2T

were retrieved from the GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/). The cBioPortal platform

(https://www.cbioportal.org/) integrates

multi-dimensional genomic and clinical datasets (24), offering analyses of somatic

mutations, DNA copy number variations (CNVs) and associated

oncogenic alterations. Through modules such as ‘Cancer Types

Summary’, ‘Plots’, ‘Mutations’ and ‘Survival’, cBioPortal was used

to delineate the mutation prevalence, classification, prognostic

relevance and potential epitope modification sites of UBE2T

across various cancer types.

CNV, single nucleotide variant (SNV)

and drug sensitivity analyses of UBE2T in pan-cancer

A database known as GSCALite (https://guolab.wchscu.cn/GSCA/#/) integrates genomic

and pharmacological data including >10,000 tumor samples from 33

TCGA cancer types and >750 small-molecule agents from the

Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) and Cancer

Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) repositories (25). UBE2T was systematically

analyzed within this platform for its association with drug

sensitivity, CNV and SNV profiles.

Correlation between UBE2T expression

levels and immune checkpoint genes and immune markers

The ‘Gene_Corr’ module of the TIMER2.0 database was

employed to assess the association between UBE2T expression

and a spectrum of immune checkpoint genes, including TNFSF9, CD27,

IDO1, CD274, TNFRSF9, CD28, TIGIT, CD40, CD70, PDCD1, CD86, LAG3,

ICOS, HHLA2, ICOSLG, CTLA4, IDO2, CD80, CD276 and BTLA (26). Heatmap visualization was generated

under the ‘Purity Adjustment’ mode to reduce the impact of sample

composition variability. Key immunotherapy response predictors,

such as mismatch repair (MMR), microsatellite instability (MSI),

tumor mutation burden (TMB) and neoantigens (NEO), were further

examined. Expression profiles for MSI and 5 core MMR genes (EPCAM,

MSH6, PMS2, MSH2 and MLH1) were retrieved from TCGA. Pearson

correlation analysis was conducted to quantify associations between

UBE2T expression and MMR, MSI, TMB and NEO metrics.

Statistical significance was determined at P<0.05.

Analysis of immune infiltration

The ESTIMATE algorithm infers stromal and immune

cell infiltration in tumor tissues via single-sample gene set

enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) based on transcriptomic profiles

(27), yielding quantitative

metrics termed ‘stromalscore’ and ‘immunescore’. This computational

procedure, executed using the R package ‘estimate’, visualizes the

outcomes through scatter plots. UBE2T expression data were

retrieved from the normalized pan-cancer dataset available in the

UCSC database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway), with

expression levels log2-transformed as log2(x

+ 0.001). Immune cell infiltration associated with UBE2T

across multiple cancer types was further evaluated using the R

algorithms ‘Timer,’ ‘EPIC’ and ‘Cibersort’.

Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), GSEA and cellular functional state

analyses

Given the elevated expression of UBE2T and

its association with adverse prognosis across various malignancies,

functional characterization was pursued through GO/KEGG and GSEA

analyses. Additionally, KEGG analysis results for pancreatic cancer

were derived from the LinkedOmics database (https://linkedomics.org/login.php). The specific steps

were as follows: Firstly, ‘Pancreatic adenocarcinoma’ was selected

as the ‘cancer cohort’, the data type was set to RNAseq,

UBE2T was set as the dataset attribute, the data type in the

Target dataset was also set as RNAseq, and finally, the Pearson

correlation test was chosen as the statistical method. A total of

123 genes, identified as UBE2T-related or interacting

partners via GEPIA2 and STRING databases (https://cn.string-db.org/), were subjected to GO and

KEGG pathway enrichment using the R packages ‘clusterprofiler’ and

‘pathview’. To examine the biological relevance of UBE2T in

tumor subtypes such as breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA) and

pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), GSEA was conducted to assess

pathway-level enrichment between phenotypic states. Moreover, the

CancerSea platform (http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/CancerSEA/), including

93,475 single cancer cells across 74 single cell RNA-sequencing

datasets from 27 cancer types and defining 14 cellular functional

states (28), was employed to

interrogate UBE2T-related cellular programs at single-cell

resolution.

Results

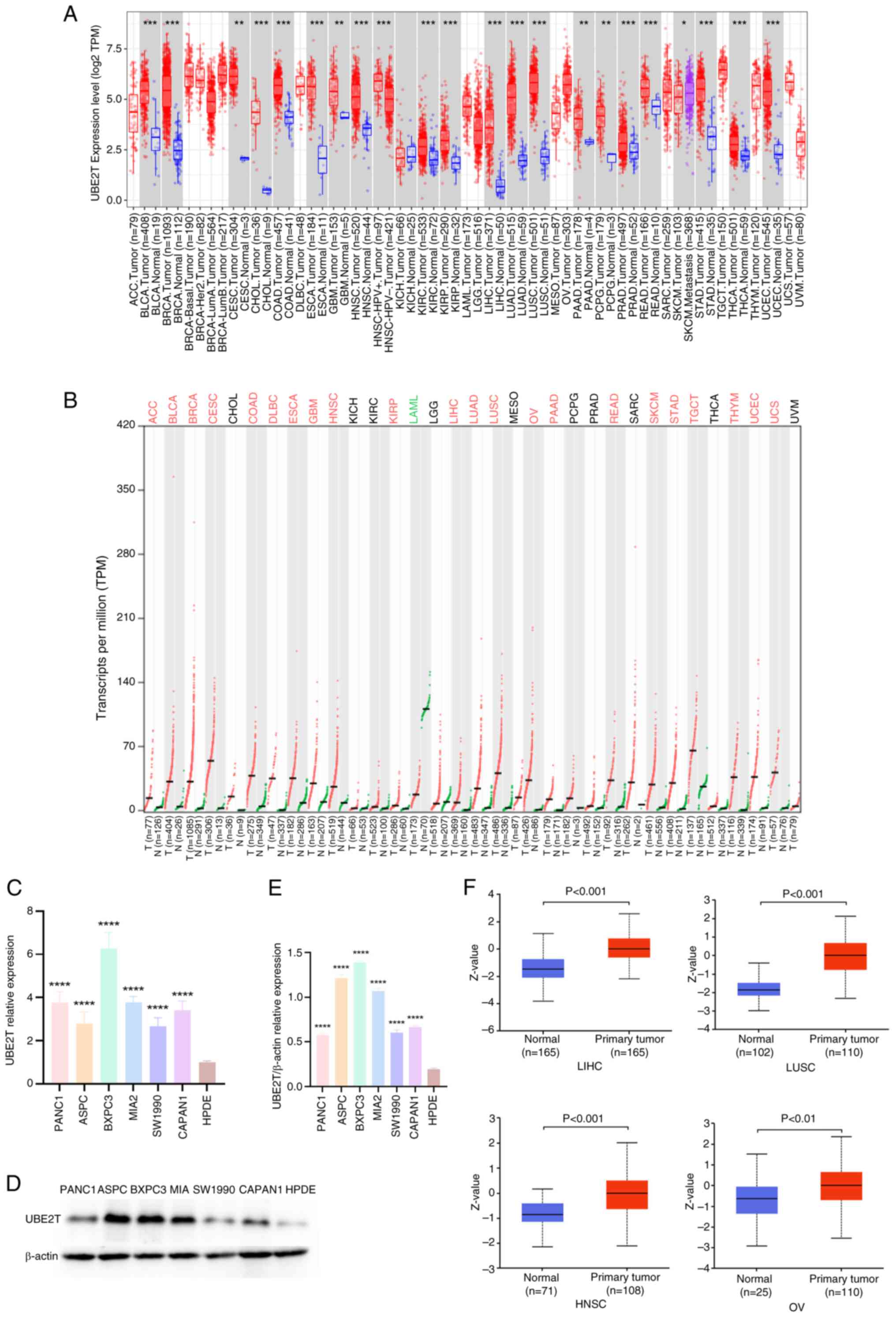

Expression profiles of UBE2T

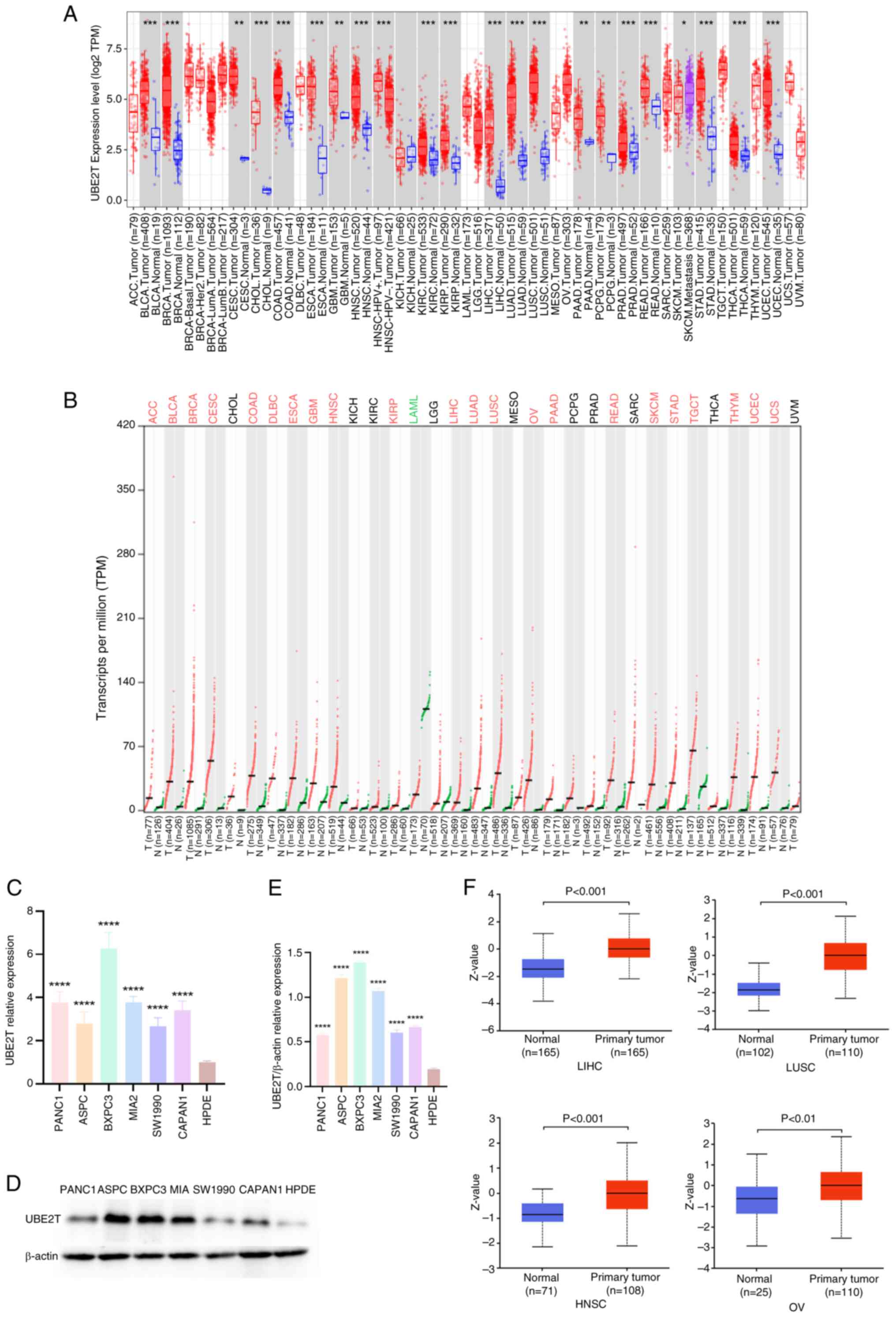

Analysis using the TIMER2.0 database revealed

differential expression of UBE2T between pan-cancer and

normal tissues within TCGA dataset. Elevated UBE2T

expression was observed in bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA),

BRCA, cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical

adenocarcinoma (CESC), cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), colon

adenocarcinoma (COAD), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), glioblastoma

multiforme (GBM), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC),

kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), kidney renal papillary

cell carcinoma (KIRP), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), lung

adenocarcinoma (LUAD), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), PAAD,

pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG), prostate adenocarcinoma

(PRAD), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), stomach adenocarcinoma

(STAD), thyroid carcinoma (THCA) and uterine corpus endometrial

carcinoma (UCEC) compared with the matched normal tissues, whereas

expression in kidney chromophobe (KICH) was reduced (Fig. 1A). Data from adrenocortical

carcinoma (ACC), acute myeloid leukemia (LAML), mesothelioma

(MESO), lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC),

brain lower grade glioma (LGG), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma

(OV), sarcoma (SARC), testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT), thymoma

(THYM), uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS) and uveal melanoma (UVM)

lacked sufficient normal tissue samples for reliable comparison. To

strengthen and extend these observations, UBE2T expression

across 33 tumor types and normal tissues was analyzed using the

GEPIA2 platform. Consistent with the initial findings, UBE2T

was generally upregulated in tumors, excluding MESO and UVM due to

the absence of normal controls. No significant expression

differences were identified for CHOL, KICH, KIRC, LGG, PCPG, PRAD,

SARC and THCA (Fig. 1B). Notably,

normal LAML tissues exhibited higher UBE2T expression

relative to tumor counterparts. Results from both databases

demonstrated notable concordance. The results shown in Fig. 1-E revealed increased UBE2T

mRNA and protein expression in pancreatic cancer cell lines

relative to normal pancreatic cells. Additionally, the results

shown in Fig. 1F indicated higher

UBE2T protein levels in LIHC, HNSC, LUSC, OV, LUAD, RCC and UCEC

compared with the respective normal tissues.

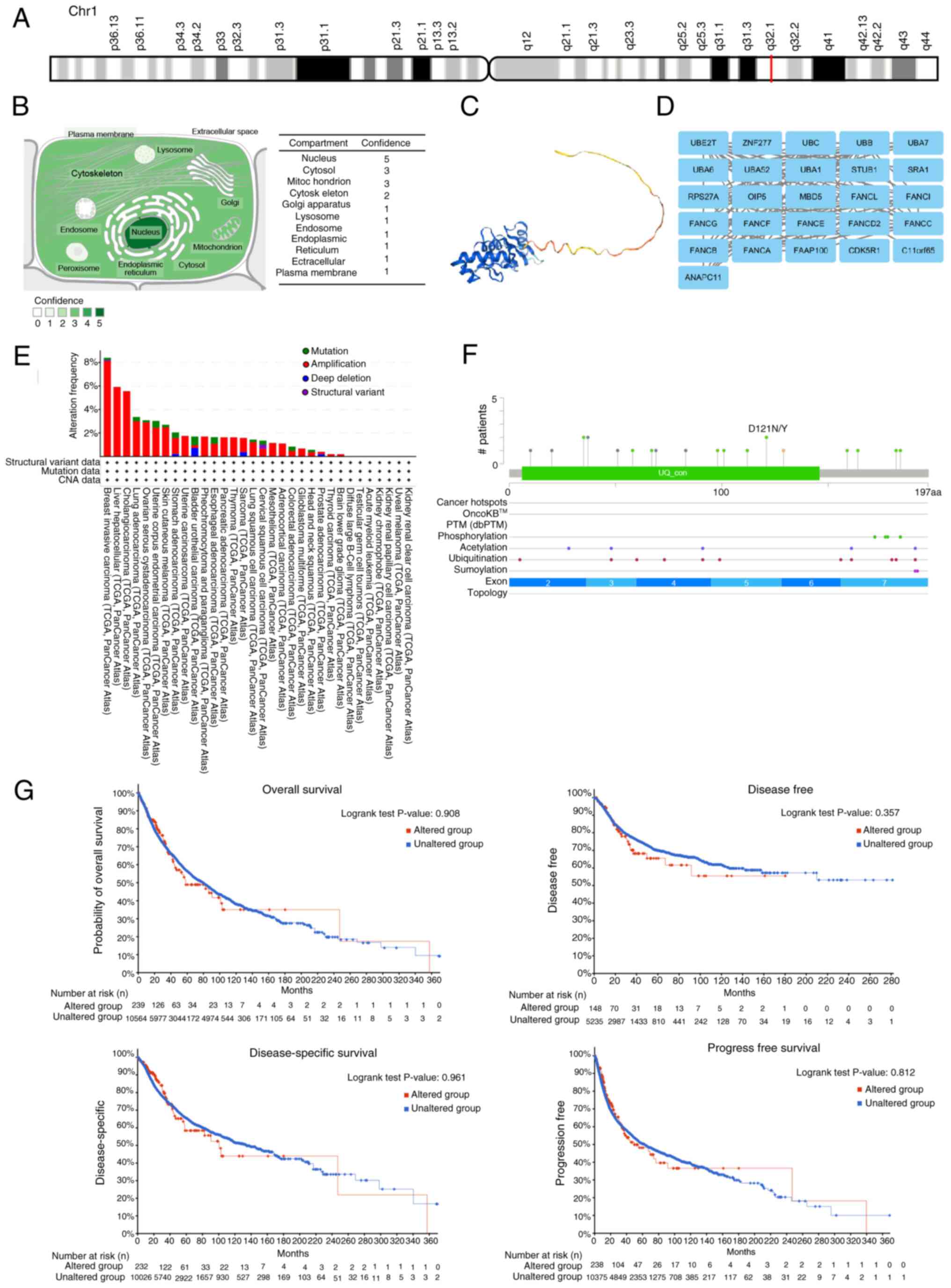

| Figure 1.UBE2T expression profiles in

pan-cancer. (A) Difference in UBE2T expression between

pan-cancer and normal tissues in TCGA; (B) difference in

UBE2T expression between pan-cancer and normal tissues in

TCGA + GTEx. Difference in UBE2T (C) mRNA and (D and E)

protein expression between pancreatic cancer cells including PANC1,

ASPC, BXPC3, MIA2, SW1990, CAPAN1 and normal pancreatic cells

(HPDE). (F) Difference in the protein level of UBE2T in LIHC, LUSC,

HNSC and OV compared with matched paracancerous tissues.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. UBE2T,

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 2T; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

TPM, transcripts per million. |

Association between UBE2T and clinical

phenotype

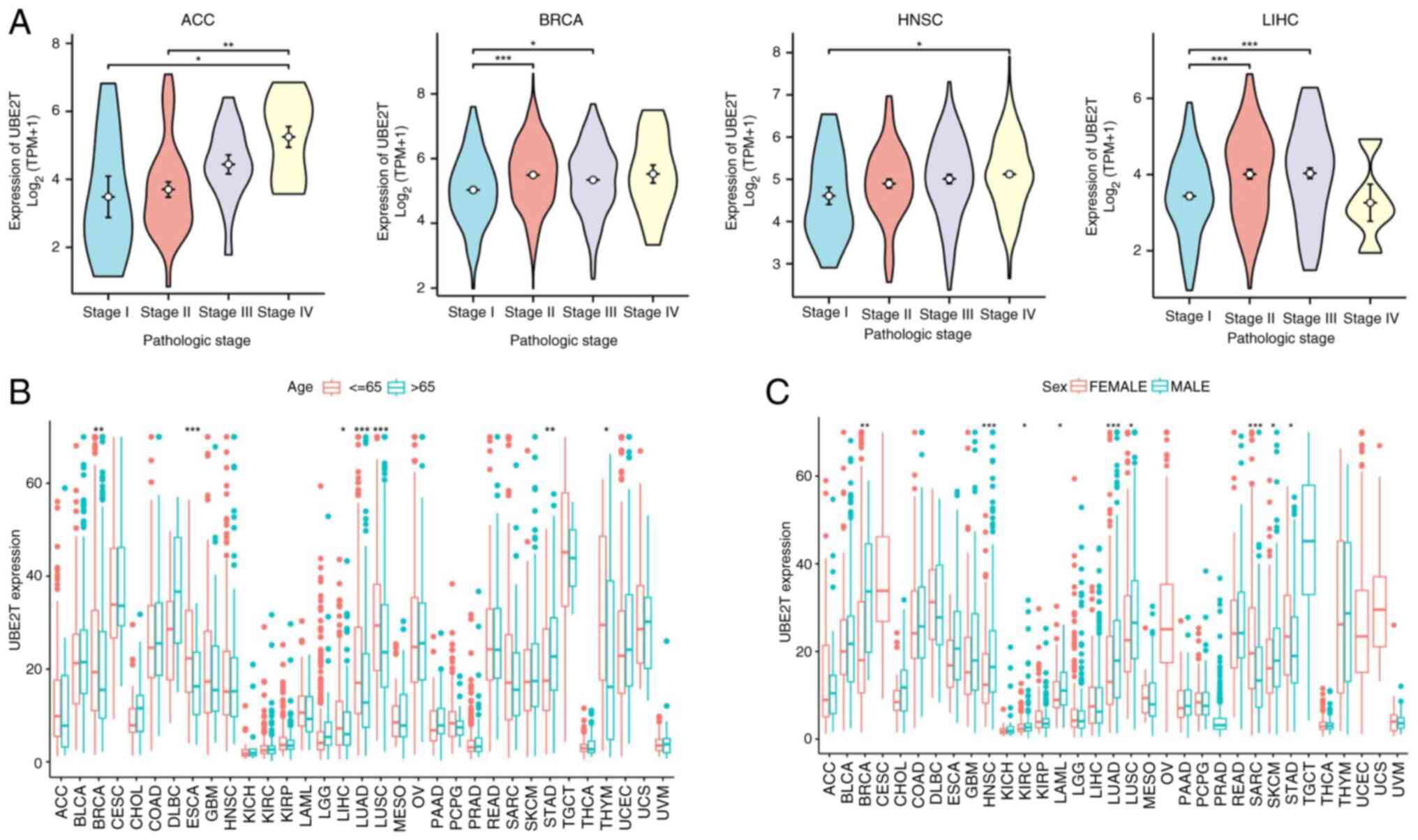

Analysis across 33 tumor types revealed significant

associations between UBE2T expression and clinical characteristics.

As depicted in Fig. 2A, elevated

UBE2T levels in ACC, BRCA, KIRP, KICH, LIHC, HNSC, KIRC and THCA

were associated with advanced pathological stages. Furthermore,

UBE2T expression was higher in individuals aged ≤65 in BRCA, ESCA,

LIHC, LUAD, LUSC and THYM, whereas STAD exhibited an inverse

pattern (Fig. 2B). Increased UBE2T

expression was observed in male patients with BRCA, HNSC, KIRC,

LAML, LUAD, LUSC and skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), in contrast to

lower expression levels in men with SARC and STAD (Fig. 2C).

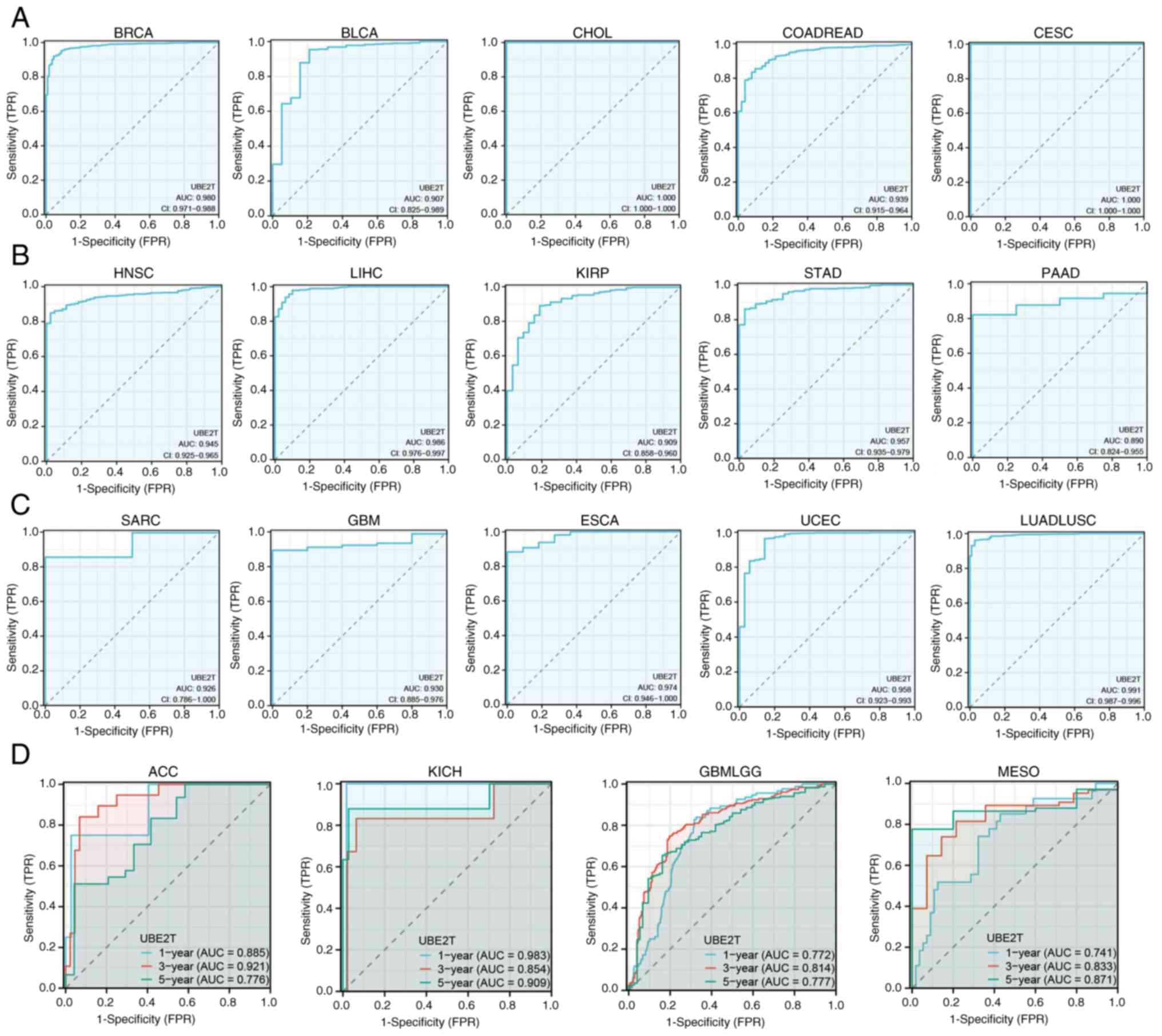

ROC curves for diagnostic and

prognostic value of UBE2T in pan-cancer

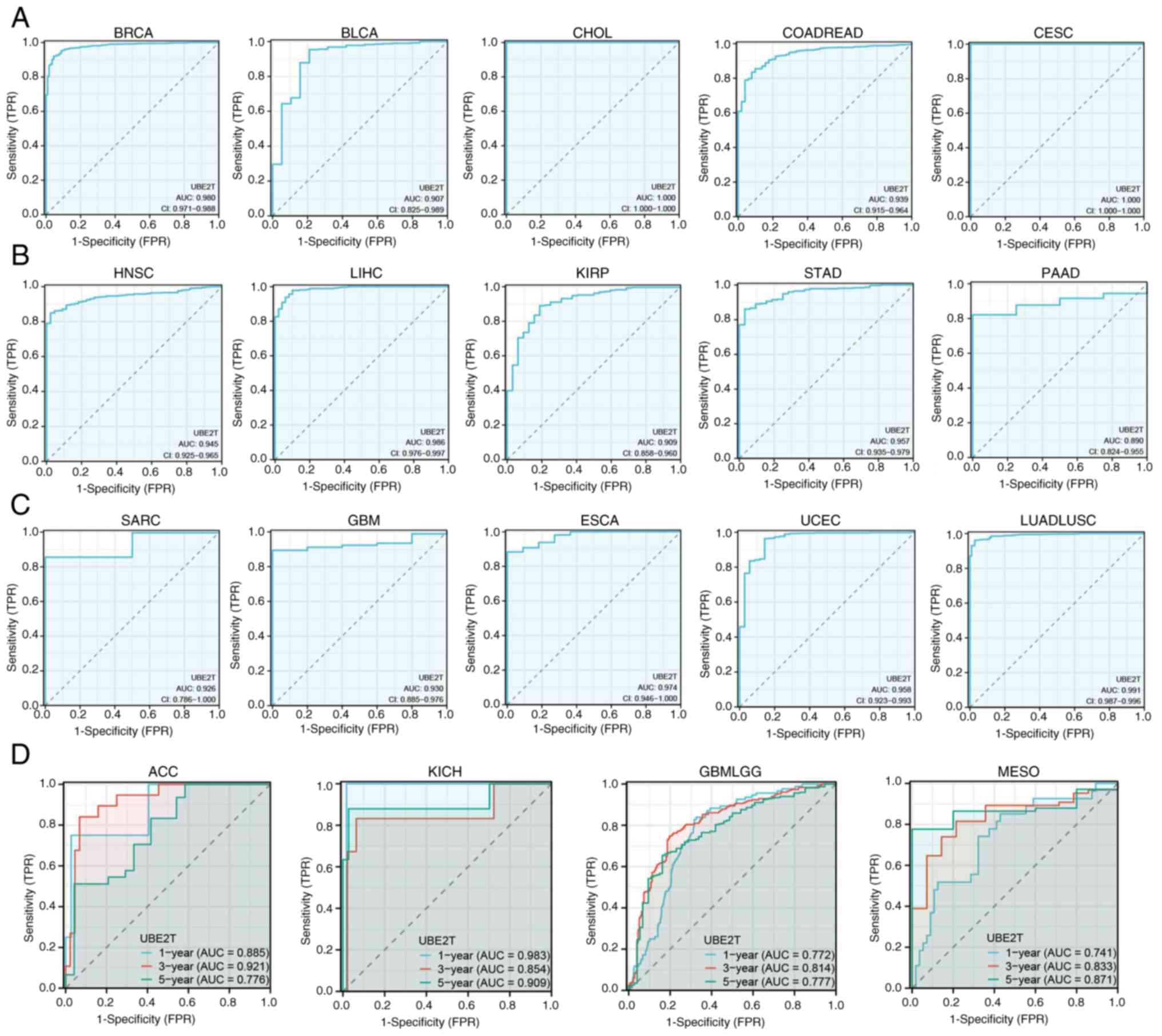

The identification of reliable biomarkers for early

tumor detection and prognostication remains a primary objective in

oncology. ROC analysis demonstrated that UBE2T achieved area

under the curve (AUC) values >0.9 in BRCA, BLCA, CHOL, COADREAD,

CESC, HNSC and LIHC, supporting its diagnostic applicability

(Fig. 3A-C). Furthermore,

UBE2T displayed AUC values >0.7 in predicting 1-, 3- and

5-year survival in ACC, KICH, GBMLGG and MESO (Fig. 3D), indicating its potential utility

in prognostic stratification.

| Figure 3.ROC curves. ROC curves for the

diagnostic value of UBE2T in (A) BRCA, BLCA, CHOL, COADREAD

and CESC, (B) HNSC, LIHC, KIRP, STAD and PAAD and (C) SARC, GBM,

ESCA, UCEC and LUADLUSC. (D) ROC curves for the prognostic value of

UBE2T in ACC, KICH, GBMLGG and MESO. ROC, receiver operating

characteristics; UBE2T, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 2T; AUC, area

under the curve; CI, confidence interval; TPR, true positive rate;

FPR, false positive rate. |

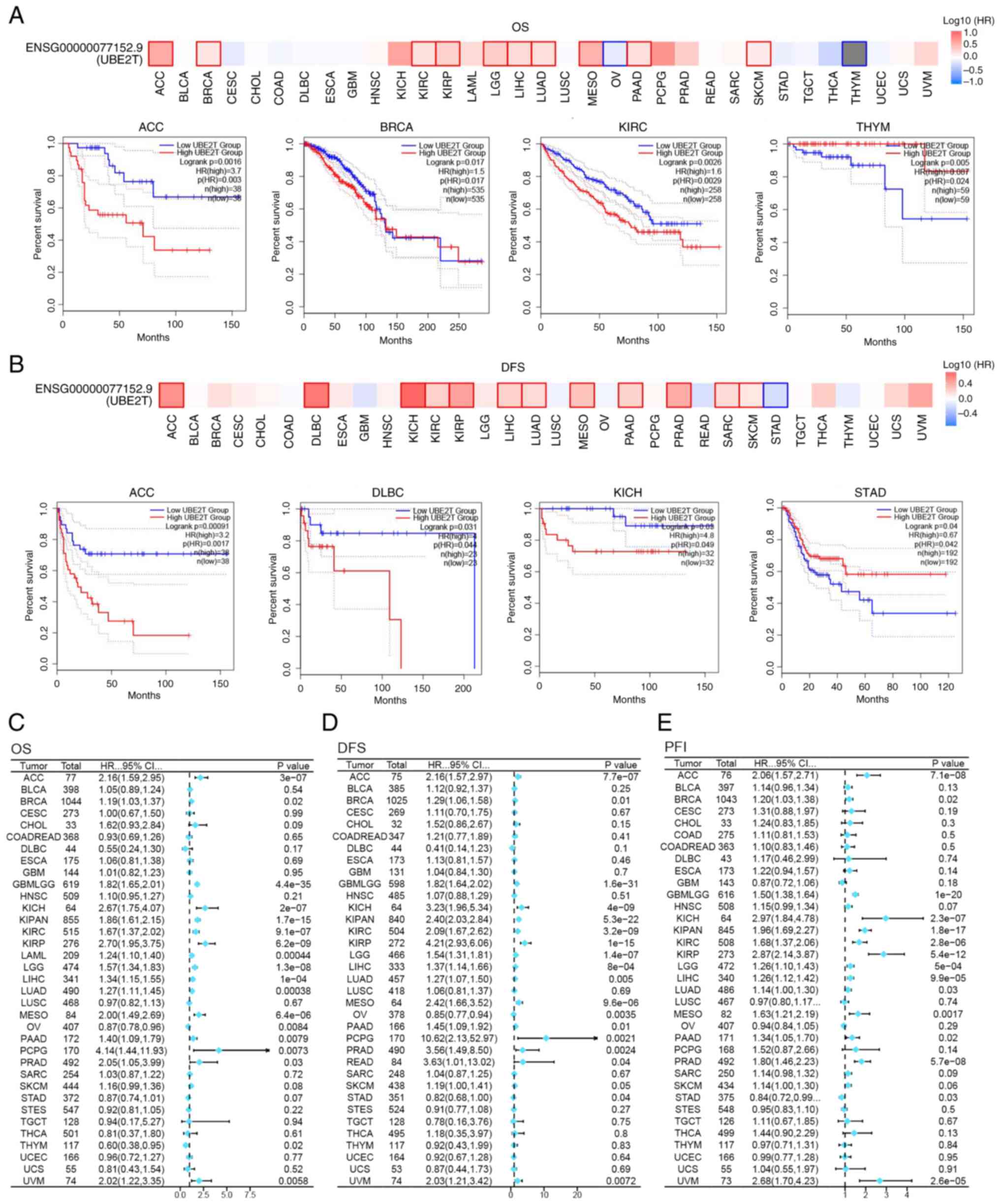

Survival analysis

Patients were stratified into high- and

low-expression cohorts according to the median UBE2T

expression level, followed by survival analysis to evaluate the

prognostic relevance of UBE2T. Analysis via GEPIA2 revealed

that elevated UBE2T expression was associated with reduced

DFS in ACC, DLBC, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LIHC, LUAD, MESO, PAAD, PRAD,

SARC and SKCM, whereas a favorable correlation with DFS was

observed in STAD (Fig. 4B).

Similarly, increased UBE2T expression was linked to

decreased OS in ACC, BRCA, KIRC, KIRP, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, MESO, PAAD

and SKCM, while improved OS outcomes were observed in OV and THYM

(Fig. 4A). Further evaluation

through Cox regression analysis reinforced the prognostic value of

UBE2T across multiple cancer types. As illustrated in

Fig. 4C, elevated UBE2T

expression predicted unfavorable outcomes in ACC, BRCA, GBMLGG,

KICH, KIPAN, KIRC, KIRP, LAML, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, MESO, PCPG, PAAD

and UVM. Additionally, Fig. 4D

indicated a negative association between high UBE2T

expression and DFS in approximately half of the tumor types

analyzed. In parallel, a shortened PFI in ACC, BRCA, KICH, PAAD,

KIRP, LUAD and others was linked to high UBE2T expression

(Fig. 4E). Collectively, the data

suggest that UBE2T functions as a negative prognostic

indicator in a broad spectrum of tumors and may offer diagnostic

utility or therapeutic relevance in oncological contexts.

UBE2T gene characterization and

genetic variation analysis

The UBE2T gene was mapped to chromosome

1q32.1 (Fig. 5A), with

high-confidence localization to the nucleus, cytosol and

mitochondria (Fig. 5B). The

tertiary protein structure of UBE2T is illustrated in Fig. 5C. Protein-protein interaction

analysis via the STRING database identified 25

UBE2T-associated proteins, including ZNF277, UBC, UBB, UBA7,

UBA6, FANCF and CDK5R1 (Fig. 5D).

Genomic alterations of UBE2T across 10,967 tumor samples

from 33 cancer types were analyzed using cBioPortal. As presented

in Fig. 5E, gene amplification

represents the most frequent alteration, particularly in BRCA,

followed by LIHC, CHOL and LUAD. Mutations are most prevalent in

BLCA, while deep deletions were also observed in BLCA, SARC, PRAD

and STAD. Predicted post-translational modifications of

UBE2T included phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination

and sumoylation (Fig. 5F). Survival

analysis revealed no statistically significant association between

UBE2T mutations and OS (P=0.908), DSS (P=0.961), DFS

(P=0.357) or PFI (P=0.812) for all individuals with cancer

(Fig. 5G).

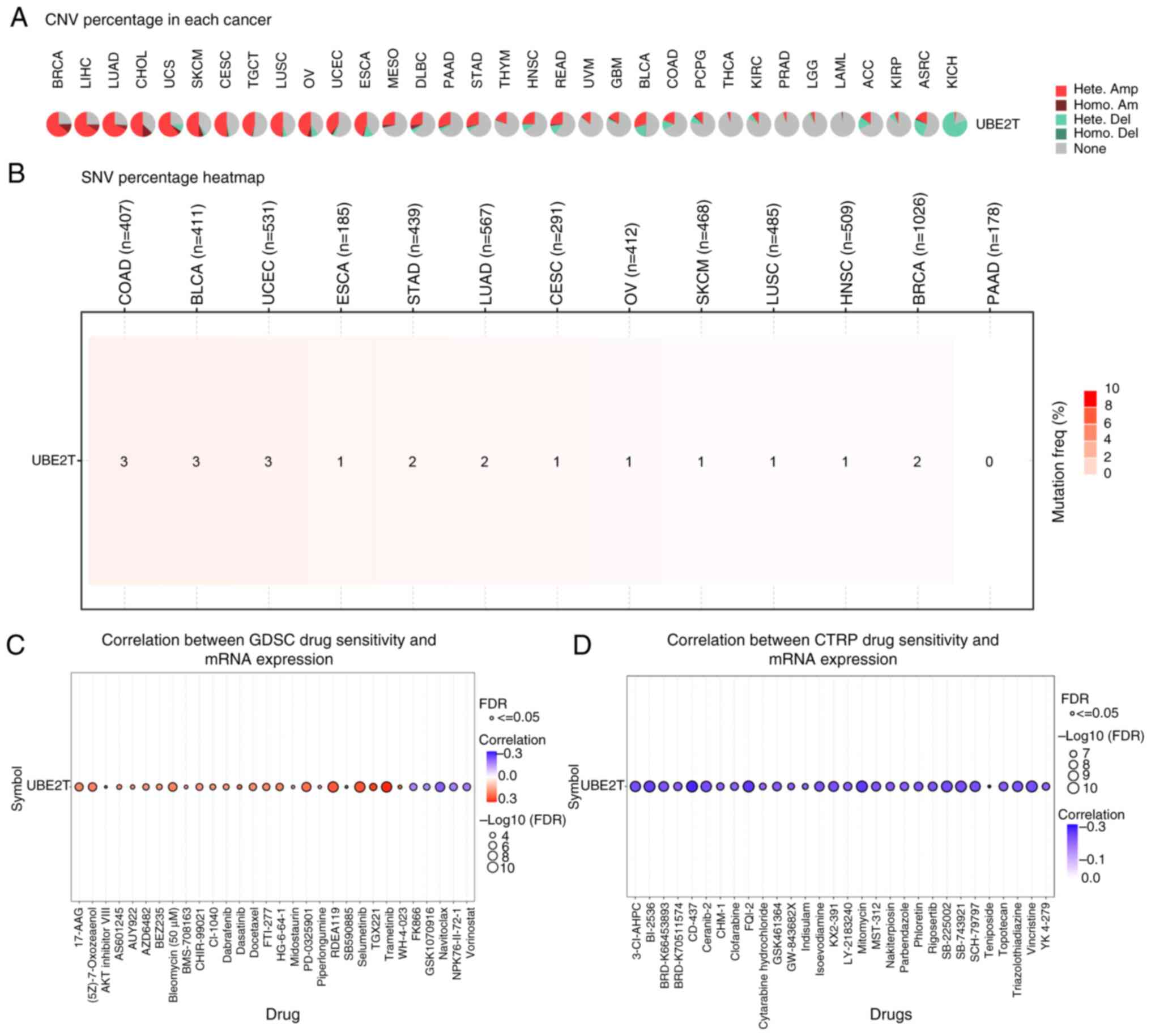

CNV, SNV and drug sensitivity analyses

of UBE2T in pan-cancer

CNV and SNV represent prevalent genetic alterations

in tumors. UBE2T was subjected to CNV, SNV and drug

sensitivity profiling via the GSCALite platform. As illustrated in

Fig. 6A, heterozygous amplification

emerged as the dominant CNV subtype of UBE2T, frequently

observed in malignancies including BRCA, LIHC, LUAD, CHOL, CESC,

UCS and SKCM. The results shown in Fig.

6B indicated that UBE2T SNVs were more frequently

detected in COAD, BLCA and UCEC, whereas no SNVs were identified in

PAAD. Drug response data were obtained from GDSC and CTRP. Analysis

based on the GDSC dataset revealed significant positive

correlations between UBE2T expression and sensitivity to

trametinib, selumetinib, RDEA119 and PD-0325901, while inverse

correlations were noted with navitoclax, vorinostat and FK866

(Fig. 6C). Additionally, CTRP-based

results demonstrated significant negative associations between

UBE2T expression and responses to CD-437, mitomycin,

SB-225002, vincristine and BI-2536 (Fig. 6D).

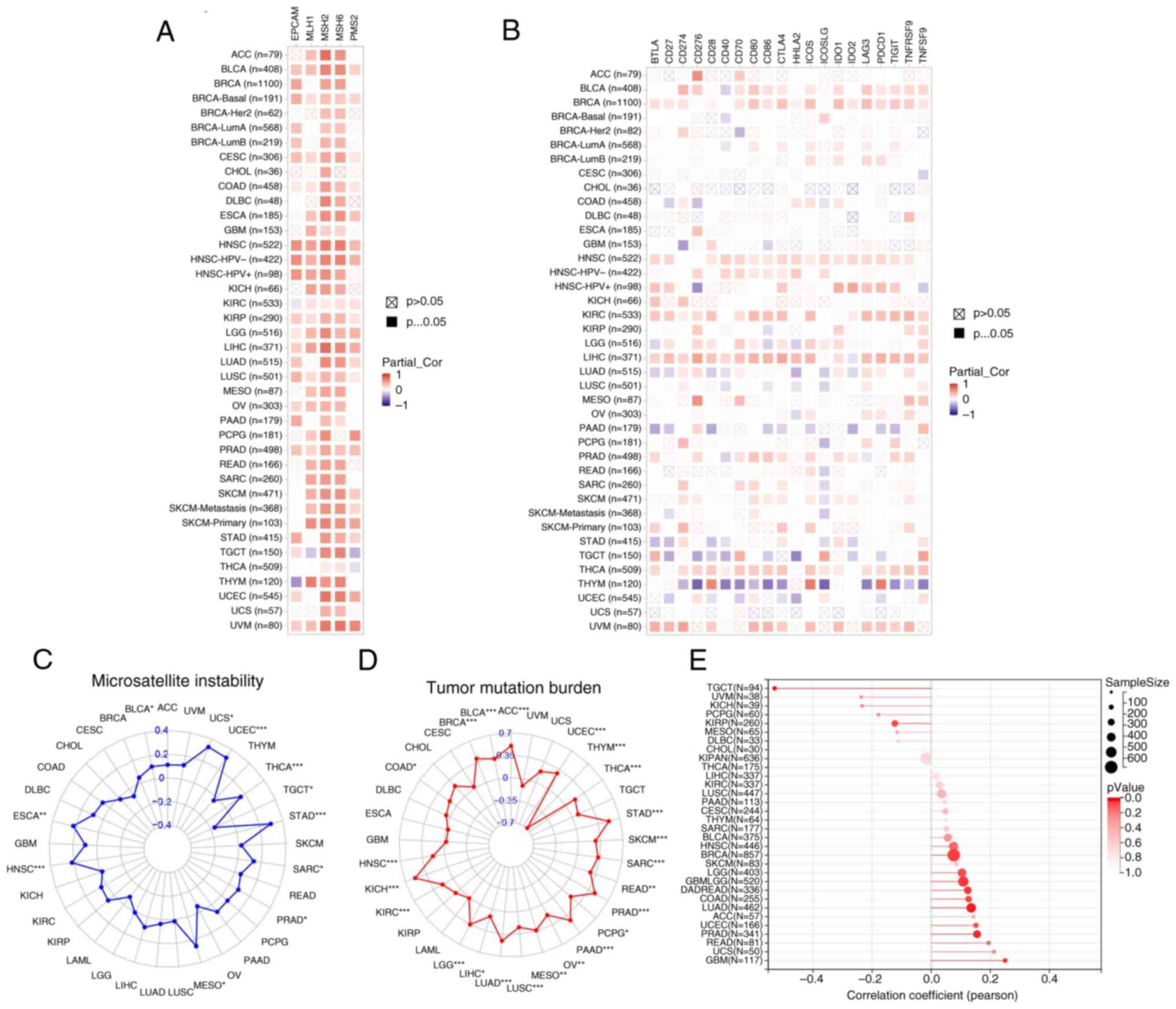

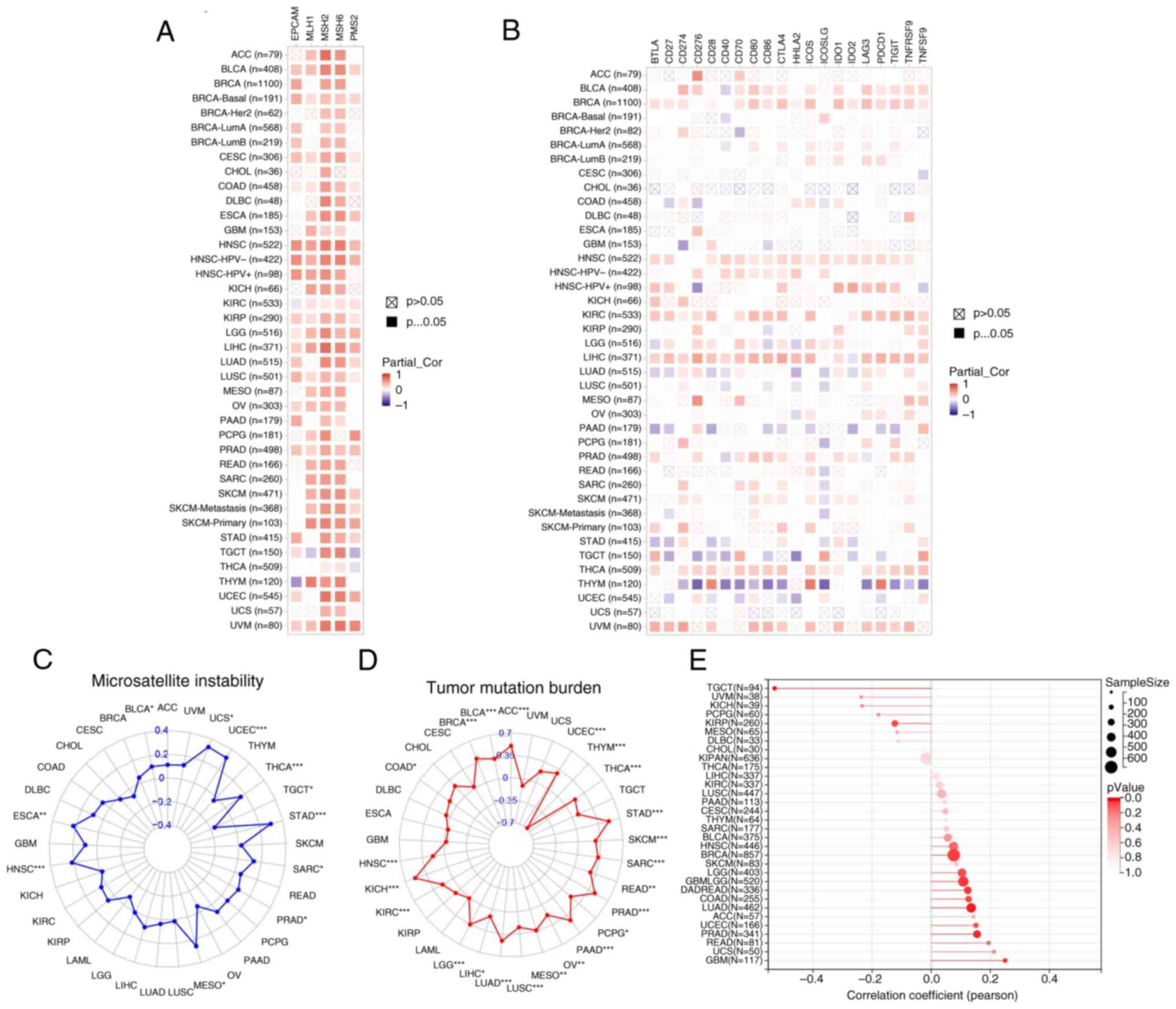

Association of UBE2T expression with

tumor immunomarkers and immune checkpoint genes

MMR, MSI, TMB and NEO serve as established

indicators for predicting responses to tumor immunotherapy

(29,30). The present analysis evaluated the

relationship between UBE2T expression and these markers. In

a pan-cancer context, UBE2T exhibited strong positive

associations with nearly all MMR-related genes (EPCAM, PMS2, MLH1,

MSH2 and MSH6) across diverse tumor types, with significant

correlations observed in BLCA, BRCA-Basal, CESC, COAD, ESCA, HNSC,

KIRC, KIRP, LGG, LIHC, LUSC, OV, PRAD and UVM (Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 7B, UBE2T expression was

positively associated with the majority of immune checkpoint genes

in BLCA, BRCA, HNSC, KIRC, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, PAAD, PRAD and TGCT,

whereas inverse associations were detected in THCA and THYM. These

patterns imply that UBE2T may modulate the tumor immune

microenvironment through immune checkpoint gene regulation in

select malignancies. Additionally, UBE2T demonstrated

significant positive correlations with MSI in BLCA, UCS, UCEC,

THCA, TGCT, STAD, SARC, PRAD, MESO, HNSC and ESCA (Fig. 7C). According to Fig. 7D, UBE2T expression showed positive

correlations across most tumor types, except for THYM, which

exhibited a negative association, and UVM, UCS, TGCT, LAML, KIRP,

GBM, ESCA, DLBC, CHOL and CESC, where no significant correlation

was noted. Fig. 7E indicated a

significant positive relationship between UBE2T and NEO in

GBM, GBMLGG, LUAD, COADREAD, BRCA and PRAD, while a negative

correlation was identified in TGCT. Collectively, these data

indicate that UBE2T expression is strongly associated with

tumor immunogenicity across multiple cancer types.

| Figure 7.Correlation between UBE2T and

immune checkpoint genes, as well as its association with

immunomarkers. (A) Correlation with MMR genes (including EPCAM,

MSH6, PMS2, MSH2 and MLH1). (B) Correlation with immune checkpoint

genes (including TNFSF9, CD27, IDO1, CD274, TNFRSF9, CD28, TIGIT,

CD40, CD70, PDCD1, CD86, LAG3, ICOS, HHLA2, ICOSLG, CTLA4, IDO2,

CD80, CD276 and BTLA). (C) Association with MSI, (D) TMB and (E)

NEO in pan-cancer. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. UBE2T,

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 2T; MMR, mismatch repair; MSI,

microsatellite instability; TMB, tumor mutational burden; NEO,

neoantigens. |

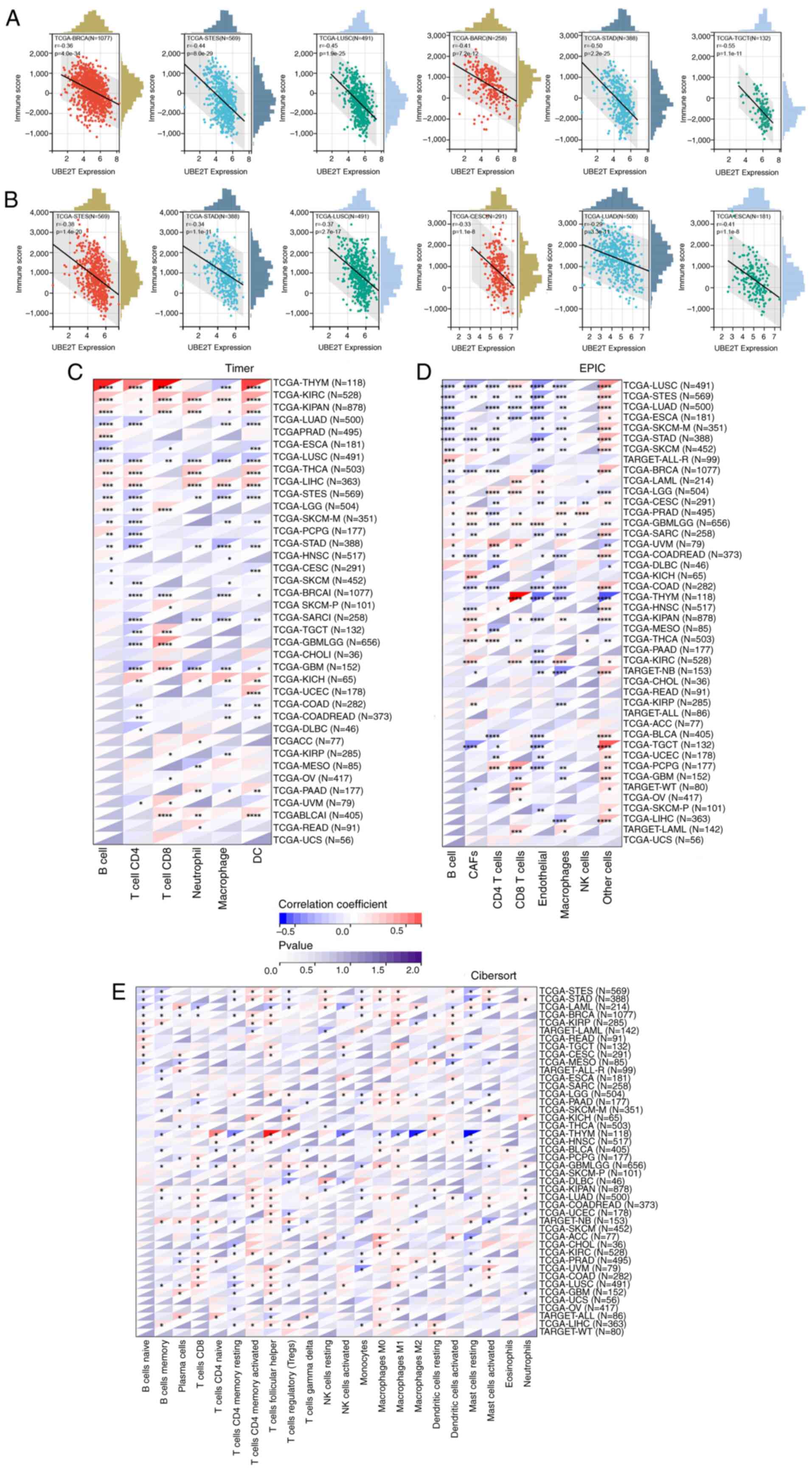

Immune infiltration analysis

Tumor-infiltrating immune cells represent a central

component of the tumor microenvironment, exerting substantial

influence on tumor progression and clinical outcomes (31–33).

The present study assessed the relationship between UBE2T

expression and both StromalScore and ImmuneScore. As shown in

Fig. 8A, UBE2T expression

exhibited a negative correlation with StromalScore in BRCA, stomach

and esophageal carcinoma (STES), LUSC, SARC, STAD and TGCT, among

others. A similar inverse association was observed between

UBE2T and ImmuneScore in STES, STAD, LUSC, CESC, LUAD and

ESCA (Fig. 8B).

To further characterize the immune landscape, TIMER,

EPIC and CIBERSORT algorithms were applied to evaluate associations

between UBE2T expression and immune cell infiltration.

According to Fig. 8C, UBE2T

expression showed positive correlations with B cells,

CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and dendritic

cells (DCs) in THYM, KIRC, KIPAN, THCA and LIHC. Additionally, a

strong positive association with cancer-associated fibroblasts

(CAFs) was observed in PRAD, GBMLGG, KICH, KIPAN, MESO, THCA, KIRC

and KIRP, while most remaining immune cell types demonstrated

negative correlations. EPIC-based analysis (Fig. 8D) indicated that UBE2T

expression was predominantly negatively associated with immune cell

infiltration across pan-cancer, with the notable exception of a

positive correlation with CD8+ T cells in THYM.

Comparable patterns were identified using the CIBERSORT algorithm

(Fig. 8E). Collectively, these data

highlight the intricate and context-dependent role of UBE2T

in modulating the tumor immune microenvironment. UBE2T may

contribute to immune evasion through the expansion of

immunosuppressive populations in certain tumors, whereas in others,

it may enhance the recruitment or activity of cytotoxic immune

subsets, thereby supporting antitumor responses.

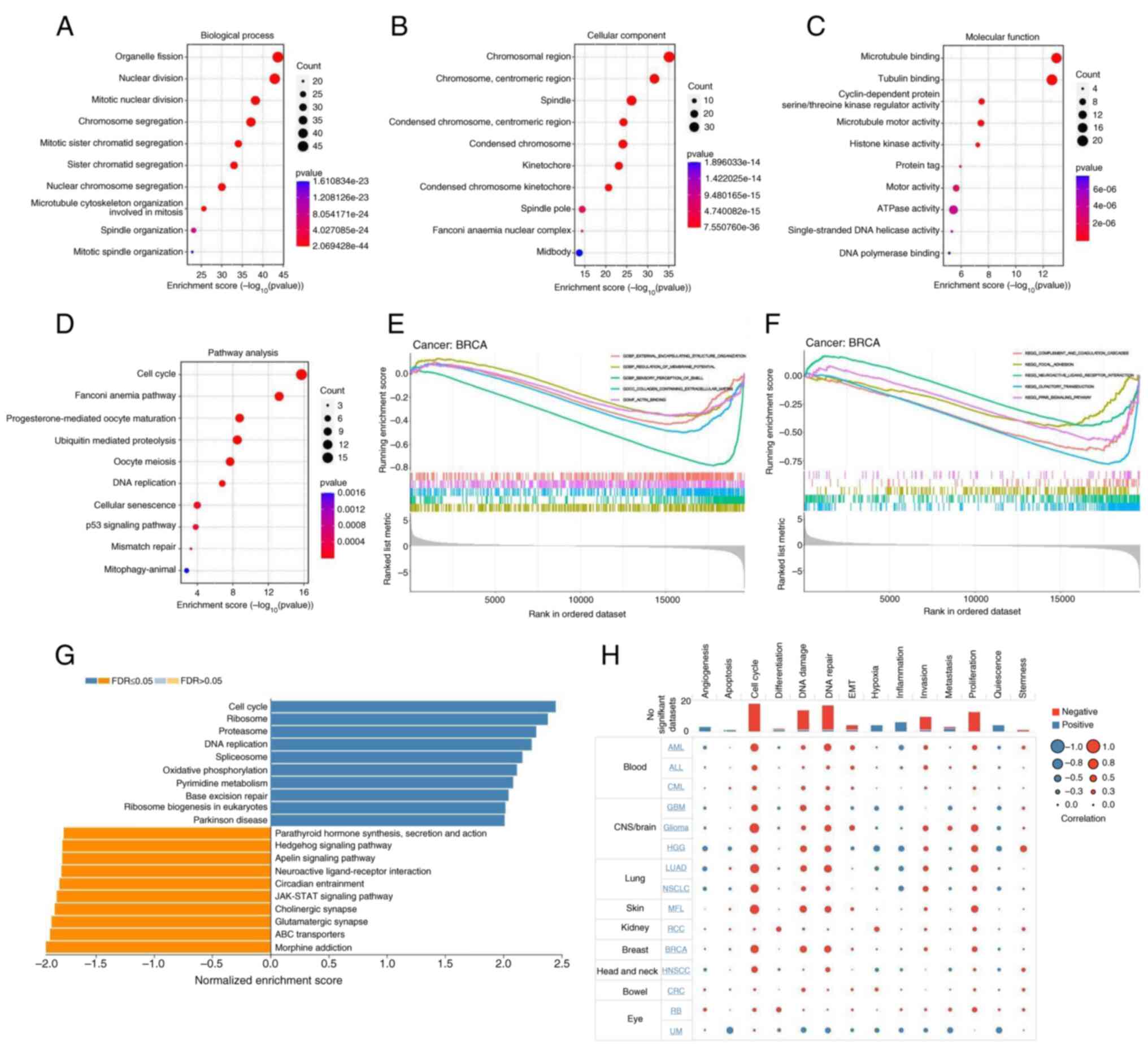

GO, KEGG, GSEA and cellular functional

state analyses

The GO database classifies gene functions into three

categories: Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC) and

Molecular Function (MF). As shown in Fig. 9A, UBE2T and its associated

genes were predominantly involved in BPs such as ‘organelle

fission’, ‘nuclear division’, ‘mitotic nuclear division’ and

‘chromosome segregation’. Corresponding CC terms included

‘chromosomal region’, ‘chromosome, centromeric region’ and

‘spindle’ (Fig. 9B), while MF

annotations primarily included ‘microtubule binding’ and ‘tubulin

binding’ (Fig. 9C). KEGG pathway

enrichment (Fig. 9D) revealed

significant associations with ‘cell cycle’, ‘Fanconi anemia

pathway’, ‘ubiquitin mediated proteolysis’, ‘oocyte meiosis’, ‘DNA

replication’ and ‘p53 signaling pathway’. Notably, ‘mismatch

repair’ also appeared as a key pathway, indicating a strong link

between UBE2T and tumor immune contexture, as well as

potential responsiveness to immunotherapeutic strategies. The GSEA

results for BRCA (Fig. 9E)

identified BPs including ‘external encapsulating structure

organization’, ‘regulation of membrane potential’ and ‘sensory

perception of smell’. Enriched CCs involved ‘collagen-containing

extracellular matrix’ and MF terms included ‘actin binding’.

GSEA-based KEGG results for BRCA further implicated pathways such

as ‘complement and coagulation cascades’, ‘focal adhesion’ and

‘PPAR signaling pathway’ in UBE2T-related mechanisms

(Fig. 9F). Analysis of KEGG results

for pancreatic cancer revealed the mechanism by which UBE2T

promotes the occurrence and development of pancreatic cancer

(Fig. 9G). The results in Fig. 9H showed that UBE2T induced

different changes in cellular function in different tumor types,

but mainly focused on ‘Cell cycle’, ‘DNA damage’, ‘DNA repair’,

‘proliferation’, ‘invasion’, ‘EMT’, ‘inflammation’ and

‘angiogenesis’.

Discussion

The UPS governs the degradation of aberrant

proteins, with E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes playing a central

role in the ubiquitination cascade. UBE2T encodes a member

of this enzyme class and has been implicated in tumorigenesis.

Accumulating evidence suggests that UBE2T contributes to

oncogenic processes across multiple malignancies. Specifically,

Huang et al (9) observed

elevated UBE2T expression in ovarian cancer, which was

associated with an unfavorable prognosis, and demonstrated that

UBE2T drove epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) via the

AKT/mTOR axis, enhancing cellular proliferation and invasiveness.

Similarly, Hu et al (10)

reported increased UBE2T levels in nasopharyngeal carcinoma

tissues, with immunohistochemical analysis linking its upregulation

to adverse clinical outcomes. Functional assays in vitro and

in vivo confirmed that UBE2T enhanced proliferation,

invasion and metastasis through activation of the

AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway. Cui et al (11) further validated

UBE2T-mediated EMT induction via the PI3K/AKT pathway in

ovarian cancer, reinforcing its role in tumor progression. In

breast cancer, Ueki et al (12) demonstrated that silencing

UBE2T upregulated BRCA1 expression, thereby attenuating

tumor cell development. In colorectal cancer, UBE2T was

found to be upregulated and implicated in tumor advancement by

accelerating p53 protein degradation (34). Based on this collective evidence,

the present study explored the relationship between UBE2T

expression and tumor prognosis, clinical characteristics,

immune-related biomarkers, immune checkpoint proteins, immune cell

infiltration and associated signaling pathways.

The results of the present study indicated that

UBE2T expression was elevated across a broad spectrum of

tumor types, including BLCA, BRCA, CESC, CHOL, COAD, KIRC, LUSC,

PCPG and UCEC. Protein-level upregulation in LIHC, HNSC, LUSC, OV,

LUAD, RCC and UCEC was corroborated by the UALCAN database,

aligning with previous studies (9,14–18,9–12,34).

Furthermore, diagnostic analyses in the present study indicated

that UBE2T exhibited high discriminative power in multiple

tumor types, with ROC values >0.9. Genomic instability, a

central feature of tumorigenesis (35,36),

was reflected in UBE2T gene alterations, predominantly

amplifications and mutations, consistent with observed CNV and SNV

profiles. These genetic aberrations likely contribute to

UBE2T upregulation and its tumor-promoting function.

Clinically, elevated UBE2T expression, more prevalent among

male patients aged ≤65, was linked to advanced disease stages in

ACC, BRCA, KIRP, KICH, LIHC, LUSC, HNSC, KIRC and THCA. This

pattern partially accounts for the association between high

UBE2T expression and poor survival outcomes in pan-cancer

cohorts, as confirmed in the present study. Similar associations

have been previously reported. For instance, Zhu et al

(37) observed UBE2T

upregulation in gallbladder cancer, correlating it with an advanced

clinical stage and an unfavorable prognosis. Increased UBE2T

expression was also documented in gastric cancer, where it's

correlated with a high T classification, low differentiation and

reduced survival (38). Parallel

trends were observed in colorectal (39), pancreatic (40), esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

(41), as well as in breast and

lung cancer (42). Cumulatively,

these data support the classification of UBE2T as an

oncogene and a viable therapeutic target. In the present study,

mechanistic analyses revealed UBE2T involvement in pathways

including ‘cell cycle’, ‘ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis’, ‘p53

signaling pathway’, ‘mismatch repair’, and ‘DNA replication’.

Functionally, UBE2T contributed to altered cellular states

characterized by enhanced proliferation, invasion and EMT,

consistent with earlier studies (9–11,42–44).

Immunotherapy represents a central strategy in

contemporary oncology, with immune-related biomarkers such as

StromalScore, ImmunoScore, TMB, MMR, MSI and NEO widely employed to

assess and predict treatment efficacy (45,46).

In the present study, UBE2T exhibited a negative correlation

with the StromalScore and ImmunoScore across most cancer types,

suggesting its involvement in shaping the tumor immune

microenvironment. Immune checkpoint genes modulate T-cell activity

to preserve immune equilibrium (47), and monoclonal antibodies targeting

these checkpoints have demonstrated sustained therapeutic benefit

in malignancies such as colorectal cancer (48). In the present study, UBE2T

showed widespread associations with immune checkpoint genes in

pan-cancer, implying that UBE2T may influence antitumor

immune responses by regulating these genes and altering immune cell

infiltration patterns (49). MMR

genes are essential for preserving genomic integrity during DNA

replication, and their dysfunction can result in MSI, contributing

to tumorigenesis through increased somatic mutation burden

(50–52), NEO generation (53) and the recruitment of immune effector

cells and inflammatory mediators (54,55).

The findings of the present study revealed significant associations

between UBE2T expression and both MMR gene expression and

MSI status in multiple tumor types. TMB, a widely recognized

biomarker in immunotherapy (56),

displayed a positive correlation with UBE2T in 23 cancer

types, further supporting a potential immunogenomic role. By

contrast, UBE2T expression was positively correlated with

NEO in only a limited subset of tumors and negatively in TGCT,

indicating heterogeneity in its relationship with NEO presentation.

Collectively, the evidence suggests that UBE2T may influence

immunotherapeutic outcomes through multifaceted interactions with

immune-related genomic features.

The tumor microenvironment comprises malignant

cells alongside surrounding immune and inflammatory components,

tumor-associated fibroblasts, microvasculature and a complex array

of chemokines and cytokines. Among immune constituents,

CD8+ T cells and Th1-polarized CD4+ T cells

exert potent cytotoxic effects, with elevated infiltration levels

inversely associated with tumor recurrence (27). An enhanced presence of DCs and

natural killer (NK) cells has also been linked to favorable

clinical outcomes (33,57). By contrast, immune evasion

mechanisms are supported by myeloid-derived suppressor cells, CAFs,

regulatory T cells, tumor-associated macrophages and M2

macrophages, which suppress T-cell-mediated antitumor responses

(58). In the present study,

analysis revealed a positive correlation between UBE2T

expression and immunocidal cell infiltration in THYM, KIRC, KIPAN,

THCA and LIHC. Conversely, UBE2T expression exhibited

negative correlations with macrophages, B cells, CD4+

and CD8+ T cells, neutrophils and DCs in LUSC, STES,

TGCT, STAD, SKCM, and COAD, with additional negative associations

observed in SKCM-M, PCPG, STAD, BRCA and SARC. EPIC algorithm-based

evaluation further indicated a positive correlation between

UBE2T and CD4+ T cells in LGG, UVM, THCA and

PCPG, as well as with CD8+ T cells in LUSC, LAML, LGG,

UVM, THYM and PCPG. Notably, UBE2T expression correlated

positively with NK cells only in PRAD and THCA. Complementary

analysis via ssGSEA demonstrated a positive correlation between Th2

cell infiltration and anaplastic grade in retinoblastoma, as

reported by Wang et al (18). Despite accumulating data, the

relationship between UBE2T and immune cell infiltration

remains unclear. Further experimental validation is warranted to

elucidate the underlying mechanisms and confirm these

associations.

Although the present study comprehensively analyzed

the UBE2T gene from various aspects, with an emphasis on

pancreatic cancer, it still has some shortcomings, mainly including

a lack of sufficient experimental verification and reliance on

publicly available databases. Therefore, further functional and

mechanistic experiments are needed to refine the data.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that

abnormal expression of UBE2T in tumor tissues, as identified

through analysis of public databases, is associated with

unfavorable clinical outcomes. Furthermore, the genetic profile of

UBE2T, its immunological correlations and underlying

regulatory mechanisms have been delineated. These insights

collectively characterize UBE2T as a proto-oncogene with

therapeutic relevance.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PL made contributions to conception and design. ZZ

obtained the database data. ANX analyzed the data using R software.

YHC obtained the experimental data. Data analysis and

interpretation was completed by ZZ. ZZ, PL, ANX and YHC confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

UBE2T

|

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 2T

|

|

ACC

|

adrenocortical carcinoma

|

|

BLCA

|

bladder urothelial carcinoma

|

|

BRCA

|

breast invasive carcinoma

|

|

CESC

|

cervical squamous cell carcinoma and

endocervical adenocarcinoma

|

|

CHOL

|

cholangiocarcinoma

|

|

COAD

|

colon adenocarcinoma

|

|

DLBC

|

lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma

|

|

ESCA

|

esophageal carcinoma

|

|

GBM

|

glioblastoma multiforme

|

|

HNSC

|

head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma

|

|

KICH

|

kidney chromophobe

|

|

KIRC

|

kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

|

|

KIRP

|

kidney renal papillary cell

carcinoma

|

|

LAML

|

acute myeloid leukemia

|

|

LGG

|

brain lower grade glioma

|

|

LIHC

|

liver hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

LUAD

|

lung adenocarcinoma

|

|

LUSC

|

lung squamous cell carcinoma

|

|

MESO

|

mesothelioma

|

|

OV

|

ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma

|

|

PAAD

|

pancreatic adenocarcinoma

|

|

PCPG

|

pheochromocytoma and

paraganglioma

|

|

PRAD

|

prostate adenocarcinoma

|

|

READ

|

rectum adenocarcinoma

|

|

SARC

|

sarcoma

|

|

SKCM

|

skin cutaneous melanoma

|

|

STAD

|

stomach adenocarcinoma

|

|

STES

|

stomach and esophageal carcinoma

|

|

TGCT

|

testicular germ cell tumor

|

|

THCA

|

thyroid carcinoma

|

|

THYM

|

thymoma

|

|

UCEC

|

uterine corpus endometrial

carcinoma

|

|

UCS

|

uterine carcinosarcoma

|

|

UVM

|

uveal melanoma

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

GTEx

|

Genotype-Tissue Expression

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating

characteristics

|

|

AUC

|

area under the curve

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

DFS

|

disease-free survival

|

|

DSS

|

disease-specific survival

|

|

PFS

|

progression-free survival

|

|

PFI

|

progression-free interval

|

|

TMB

|

tumor mutation burden

|

|

MSI

|

microsatellite instability

|

|

NEO

|

neoantigens

|

|

CNV

|

copy number variation

|

|

SNV

|

single nucleotide variant

|

|

BP

|

Biological Process

|

|

CC

|

Cellular Component

|

|

MF

|

Molecular Function

|

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Miller KD, Ortiz AP, Pinheiro PS, Bandi P,

Minihan A, Fuchs HE, Tyson DM, Tortolero-Luna G, Fedewa SA, Jemal

AM and Siegel RL: Cancer statistics for the US Hispanic/Latino

population, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:466–487. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yang J, Xu R, Wang C, Qiu J, Ren B and You

L: Early screening and diagnosis strategies of pancreatic cancer: A

comprehensive review. Cancer Commun (Lond). 41:1257–1274. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sun W, Shi Q, Zhang H, Yang K, Ke Y, Wang

Y and Qiao L: Advances in the techniques and methodologies of

cancer gene therapy. Discov Med. 27:45–55. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Abbott M and Ustoyev Y: Cancer and the

immune system: The history and background of immunotherapy. Semin

Oncol Nurs. 35:1509232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yang Z, Wu L, Wang A, Tang W, Zhao Y, Zhao

H and Teschendorff AE: dbDEMC 2.0: Updated database of

differentially expressed miRNAs in human cancers. Nucleic Acids

Res. 45:D812–D818. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Park J, Cho J and Song EJ:

Ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as a target for anticancer

treatment. Arch Pharm Res. 43:1144–1161. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Johnson DE: The ubiquitin-proteasome

system: Opportunities for therapeutic intervention in solid tumors.

Endocr Relat Cancer. 22:T1–T17. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Huang W, Huang H, Xiao Y, Wang L, Zhang T,

Fang X and Xia X: UBE2T is upregulated, predicts poor prognosis,

and promotes cell proliferation and invasion by promoting

epithelial-mesenchymal transition via inhibiting autophagy in an

AKT/mTOR dependent manner in ovarian cancer. Cell Cycle.

21:780–791. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hu W, Xiao L, Cao C, Hua S and Wu D: UBE2T

promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell proliferation, invasion, and

metastasis by activating the AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway.

Oncotarget. 7:15161–15172. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cui P, Li H, Wang C, Liu Y, Zhang M, Yin

Y, Sun Z, Wang Y and Chen X: UBE2T regulates epithelial-mesenchymal

transition through the PI3K-AKT pathway and plays a carcinogenic

role in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 15:1032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ueki T, Park JH, Nishidate T, Kijima K,

Hirata K, Nakamura Y and Katagiri T: Ubiquitination and

downregulation of BRCA1 by ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T

overexpression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res.

69:8752–8760. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Alpi AF, Chaugule V and Walden H:

Mechanism and disease association of E2-conjugating enzymes:

Lessons from UBE2T and UBE2L3. Biochem J. 473:3401–3419. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Alagpulinsa DA, Kumar S, Talluri S,

Nanjappa P, Buon L, Chakraborty C, Samur MK, Szalat R, Shammas MA

and Munshi NC: Amplification and overexpression of E2 ubiquitin

conjugase UBE2T promotes homologous recombination in multiple

myeloma. Blood Adv. 3:3968–3972. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Dutta R, Guruvaiah P, Reddi KK, Bugide S,

Bandi DS, Edwards YJK, Singh K and Gupta R: UBE2T promotes breast

cancer tumor growth by suppressing DNA replication stress. NAR

Cancer. 4:zcac0352022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hao P, Kang B, Li Y, Hao W and Ma F: UBE2T

promotes proliferation and regulates PI3K/Akt signaling in renal

cell carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 20:1212–1220. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu Y, Ji W, Yue N and Zhou W:

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T promotes tumor stem cell

characteristics and migration of cervical cancer cells by

regulating the GRP78/FAK pathway. Open Life Sci. 16:1082–1090.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang Z, Chen N, Liu C, Cao G, Ji Y, Yang W

and Jiang Q: UBE2T is a prognostic biomarker and correlated with

Th2 cell infiltrates in retinoblastoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

614:138–144. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hutter C and Zenklusen JC: The cancer

genome atlas: Creating lasting value beyond its data. Cell.

173:283–285. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q,

Li B and Liu XS: TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48:W509–W514. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C and

Zhang Z: GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression

profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:W98–W102.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ghandi M, Huang FW, Jané-Valbuena J,

Kryukov GV, Lo CC, McDonald ER III, Barretina J, Gelfand ET,

Bielski CM, Li H, et al: Next-generation characterization of the

cancer cell line encyclopedia. Nature. 569:503–508. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G,

Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al:

Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical

profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 6:pl12013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu CJ, Hu FF, Xia MX, Han L, Zhang Q and

Guo AY: GSCALite: A web server for gene set cancer analysis.

Bioinformatics. 34:3771–3772. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhao Y, Zhang M, Pu H, Guo S, Zhang S and

Wang Y: Prognostic implications of pan-cancer CMTM6 expression and

its relationship with the immune microenvironment. Front Oncol.

10:5859612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E,

Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Treviño V, Shen H, Laird PW,

Levine DA, et al: Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune

cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 4:26122013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yuan H, Yan M, Zhang G, Liu W, Deng C,

Liao G, Xu L, Luo T, Yan H, Long Z, et al: CancerSEA: A cancer

single-cell state atlas. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:D900–D908. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Schumacher TN and Schreiber RD:

Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 348:69–74. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yarchoan M, Hopkins A and Jaffee EM: Tumor

mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J

Med. 377:2500–2501. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tada K, Kitano S, Shoji H, Nishimura T,

Shimada Y, Nagashima K, Aoki K, Hiraoka N, Honma Y, Iwasa S, et al:

Pretreatment immune status correlates with progression-free

survival in chemotherapy-treated metastatic colorectal cancer

patients. Cancer Immunol Res. 4:592–599. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Angelova M, Charoentong P, Hackl H,

Fischer ML, Snajder R, Krogsdam AM, Waldner MJ, Bindea G, Mlecnik

B, Galon J and Trajanoski Z: Characterization of the

immunophenotypes and antigenomes of colorectal cancers reveals

distinct tumor escape mechanisms and novel targets for

immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 16:642015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sanz-Pamplona R, Melas M, Maoz A, Schmit

SL, Rennert H, Lejbkowicz F, Greenson JK, Sanjuan X, Lopez-Zambrano

M, Alonso MH, et al: Lymphocytic infiltration in stage II

microsatellite stable colorectal tumors: A retrospective prognosis

biomarker analysis. PLoS Med. 17:e10032922020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wu M, Li X, Huang W, Chen Y, Wang B and

Liu X: Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T(UBE2T) promotes colorectal

cancer progression by facilitating ubiquitination and degradation

of p53. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 45:1014932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhao L, Jiang L, Wang L, He J, Yu H, Sun

G, Chen J, Xiu Q and Li B: UbcH10 expression provides a useful tool

for the prognosis and treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. J

Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 138:1951–1961. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhu X, Li T, Niu X, Chen L and Ge C:

Identification of UBE2T as an independent prognostic biomarker for

gallbladder cancer. Oncol Lett. 20:442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yu H, Xiang P, Pan Q, Huang Y, Xie N and

Zhu W: Ubiquitin-Conjugating enzyme E2T is an independent

prognostic factor and promotes gastric cancer progression. Tumour

Biol. 37:11723–11732. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Luo M and Zhou Y: Comprehensive analysis

of differentially expressed genes reveals the promotive effects of

UBE2T on colorectal cancer cell proliferation. Oncol Lett.

22:7142021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zheng YW, Gao PF, Ma MZ, Chen Y and Li CY:

Role of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T in the carcinogenesis and

progression of pancreatic cancer. Oncol Lett. 20:1462–1468. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang X, Liu Y, Leng X, Cao K, Sun W, Zhu J

and Ma J: UBE2T contributes to the prognosis of esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 27:6325312021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Perez-Peña J, Corrales-Sánchez V, Amir E,

Pandiella A and Ocana A: Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T (UBE2T)

and denticleless protein homolog (DTL) are linked to poor outcome

in breast and lung cancers. Sci Rep. 7:175302017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wang Y, Leng H, Chen H, Wang L, Jiang N,

Huo X and Yu B: Knockdown of UBE2T inhibits osteosarcoma cell

proliferation, migration, and invasion by suppressing the PI3K/Akt

signaling pathway. Oncol Res. 24:361–369. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Gong YQ, Peng D, Ning XH, Yang XY, Li XS,

Zhou LQ and Guo YL: UBE2T silencing suppresses proliferation and

induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in bladder cancer cells.

Oncol Lett. 12:4485–4492. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhang Y and Zhang Z: The history and

advances in cancer immunotherapy: Understanding the characteristics

of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic

implications. Cell Mol Immunol. 17:807–821. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Peng M, Mo Y, Wang Y, Wu P, Zhang Y, Xiong

F, Guo C, Wu X, Li Y, Li X, et al: Neoantigen vaccine: An emerging

tumor immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 18:1282019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liu Y, Zugazagoitia J, Ahmed FS, Henick

BS, Gettinger SN, Herbst RS, Schalper KA and Rimm DL: Immune cell

PD-L1 colocalizes with macrophages and is associated with outcome

in PD-1 pathway blockade therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 26:970–977.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ciardiello D, Vitiello PP, Cardone C,

Martini G, Troiani T, Martinelli E and Ciardiello F: Immunotherapy

of colorectal cancer: Challenges for therapeutic efficacy. Cancer

Treat Rev. 76:22–32. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Topalian SL, Drake CG and Pardoll DM:

Immune checkpoint blockade: A common denominator approach to cancer

therapy. Cancer Cell. 27:450–461. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Baretti M and Le DT: DNA mismatch repair

in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 189:45–62. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Sha D, Jin Z, Budczies J, Kluck K,

Stenzinger A and Sinicrope FA: Tumor mutational burden as a

predictive biomarker in solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 10:1808–1825.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ballhausen A, Przybilla MJ, Jendrusch M,

Haupt S, Pfaffendorf E, Seidler F, Witt J, Sanchez AH, Urban K,

Draxlbauer M, et al: The shared frameshift mutation landscape of

microsatellite-unstable cancers suggests immunoediting during tumor

evolution. Nat Commun. 11:47402020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Li J, Wu C, Hu H, Qin G, Wu X, Bai F,

Zhang J, Cai Y, Huang Y, Wang C, et al: Remodeling of the immune

and stromal cell compartment by PD-1 blockade in mismatch

repair-deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 41:1152–1169.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Xie N, Shen G, Gao W, Huang Z, Huang C and

Fu L: Neoantigens: Promising targets for cancer therapy. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 8:92023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Shin SJ, Kim SY, Choi YY, Son T, Cheong

JH, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Park CG and Kim HI: Mismatch repair status of

gastric cancer and its association with the local and systemic

immune response. Oncologist. 24:e835–e844. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Hou W, Yi C and Zhu H: Predictive

biomarkers of colon cancer immunotherapy: Present and future. Front

Immunol. 13:10323142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Gulubova MV, Ananiev JR, Vlaykova TI,

Yovchev Y, Tsoneva V and Manolova IM: Role of dendritic cells in

progression and clinical outcome of colon cancer. Int J Colorectal

Dis. 27:159–169. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Veglia F, Perego M and Gabrilovich D:

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat Immunol.

19:108–119. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|