Introduction

Pneumocystis jirovecii infection, classified

as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP), is a leading

cause of pneumonia in immunocompromised populations, including

individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), solid organ

transplant recipients on immunosuppressive regimens, and patients

with cancer undergoing dose-dense chemotherapy (1). Notably, PJP carries a substantial

mortality risk, particularly in non-HIV immunocompromised

populations where 90-day mortality is significantly higher than in

HIV-infected patients (adjusted OR=5.47; 95% CI:2.16–14.1 for solid

tumor patients) (2). Owing to their

immunocompromised status, these patients exhibit heightened

susceptibility to Pneumocystis jirovecii colonization and

subsequent progression to clinically significant PJP (3), with critical risk factors including

prolonged high-dose corticosteroid use (≥10 mg/day prednisone

equivalent, increasing mortality by 80%) and lymphopenia

(<0.6×109/l). Mortality rates escalate to 43.3% for

non-HIV PJP patients requiring ICU admission, and reach 61.6% at 3

months in lung cancer population (4).

Advanced HR+/HER2- breast cancer survival has

significantly improved with CDK4/6 inhibitors (median OS now

exceeding 5 years in 1L), particularly in visceral metastasis

(5). Abemaciclib, a selective

CDK4/6 inhibitor, is approved for the treatment of hormone receptor

(HR)-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

(HER2)-negative breast cancer. As a CDK4/6 inhibitor, abemaciclib

functions by inhibiting CDK4 and CDK6 proteins, which are critical

regulators of cell division and growth. This inhibition directly

suppresses cancer cell proliferation (6). Clinically, abemaciclib is utilized in

combination with endocrine therapy (ET), demonstrating established

efficacy in both early-stage and advanced

HR+/HER2− breast cancer settings (7). It constitutes a first-line

standard-of-care option for HR+/HER2−

advanced disease, with key clinical trials (MONARCH-2 and

MONARCH-3) reporting therapeutic benefits when combined with

aromatase inhibitors or fulvestran (8,9). The

most common adverse event (AE) associated with abemaciclib is

diarrhea, with other frequently reported toxicities including

nausea, fatigue, elevated serum creatinine and myelosuppression

(neutropenia and lymphopenia) (10,11).

The present report details a case of PJP occurring

in a patient with HR+/HER2− advanced breast

cancer receiving abemaciclib in combination with ET. There have

been no prior documented cases of PJP in patients treated with

abemaciclib, to the best of our knowledge.

Case report

In February 2023, a 52-year-old treatment-naïve

woman diagnosed with stage IV HR+/HER2−

advanced breast cancer, confirmed via core needle biopsy of the

primary breast lesion and metastatic lung deposits at Longhua

Hospital affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese

Medicine (Shanghai, China), had been receiving combination therapy

with abemaciclib (400 mg/day orally), letrozole (2.5 mg/day orally)

and goserelin (3.6 mg administered subcutaneously once monthly) in

28-day cycles for 6 cycles. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

images of the primary breast lesion and metastatic lung deposits

via core needle biopsy are presented in Fig. S1. Tissue sections were

formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded, and immunohistochemistry was

performed using antibodies following antigen retrieval. HER2

expression was scored using the 2023 American Society of Clinical

Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines (12).

Tissue specimens were initially fixed in 10% neutral

buffered formalin, prepared by mixing 100 ml of 37–40% formaldehyde

with 900 ml PBS, at 4°C for 24 h (cold fixation). Paraffin-embedded

tissues were prepared and sectioned to a thickness of 4 µm. For

antigen retrieval, heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed

using citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 min, followed by a

30-min cooling period at room temperature (RT). Sections were then

rehydrated through a descending alcohol series: Two washes in

xylene (5 min each), two washes in 100% ethanol (2 min each), one

wash in 95% ethanol (2 min), one wash in 70% ethanol (2 min) and

finally a rinse in dH2O. For intracellular or membrane

epitopes, permeabilization was carried out using 0.1% Triton X-100

in PBS for 10 min at RT. Non-specific binding sites were blocked by

incubating sections with 5% normal goat serum (cat. no. 16210064;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at RT. Sections were

subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody,

rabbit anti-CDK4 monoclonal antibody (cat. no. 12790; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), diluted 1:200 in antibody diluent.

Following primary incubation, sections were incubated for 1 h at RT

with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary

antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (cat. no. ab6721; Abcam),

diluted 1:500 in PBS. Detection was performed using HRP/DAB with

3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; cat. no. K3468; Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) as the chromogen.

For H&E staining, sections were stained with

Harris hematoxylin for 5 min at 25°C, followed by a 10-min rinse

under running tap water. Differentiation was then performed by

briefly treating sections with 1% acid alcohol (1 ml HCl in 99 ml

70% ethanol) for 5–10 sec at RT; this step was monitored

microscopically until the nuclei turned pale blue. Bluing was

achieved by immersing sections in 0.2% ammonium hydroxide for 30

sec at RT. Sections were counterstained with 0.5% aqueous eosin Y

solution for 2 min at RT. Immediately following eosin staining,

sections were dehydrated through a graded alcohol series. All

H&E and IHC-stained sections were routinely observed under a

light microscope during protocol optimization and quality control.

Finally, images were captured using a BX53 microscope (Olympus

Corp.) equipped with a DP74 camera at either ×200 or ×400

magnification (oil immersion for ×400).

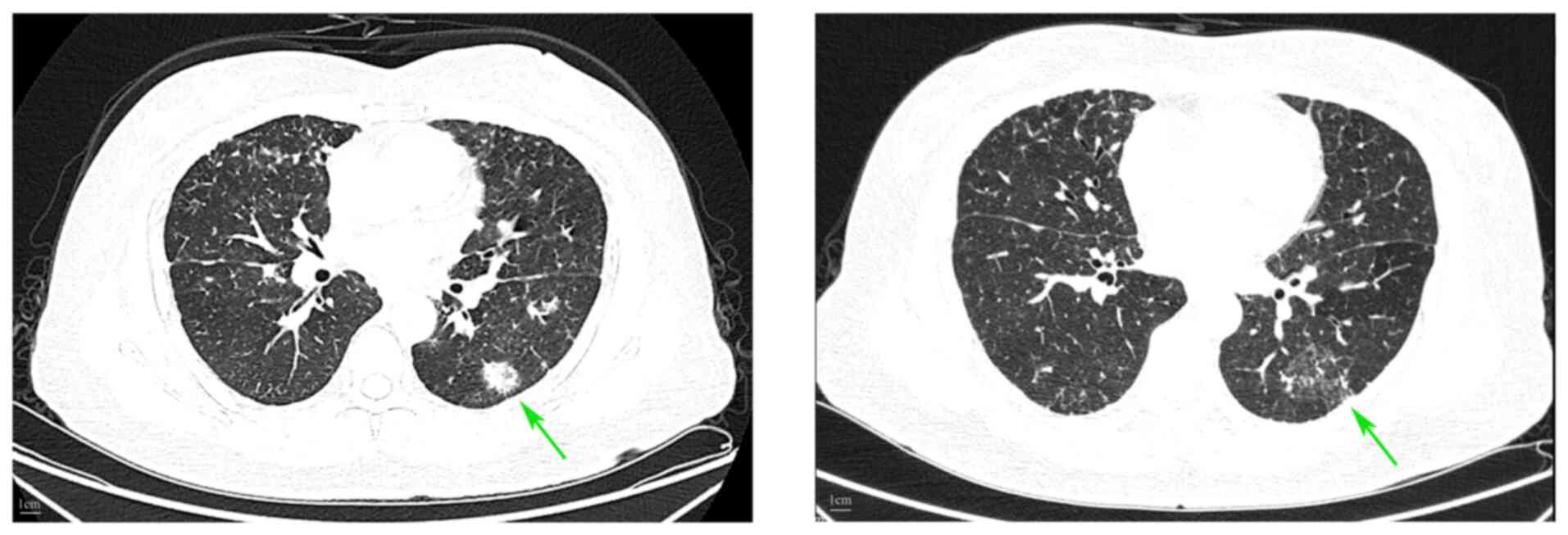

Before starting antitumor therapy, the baseline

CD4+/CD8+ T-cell counts of the patient were

normal, and viral/bacterial infection screens were negative. Tumor

response assessed using CT demonstrated partial remission per the

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 criteria

in June 2023 (13) (Fig. 1).

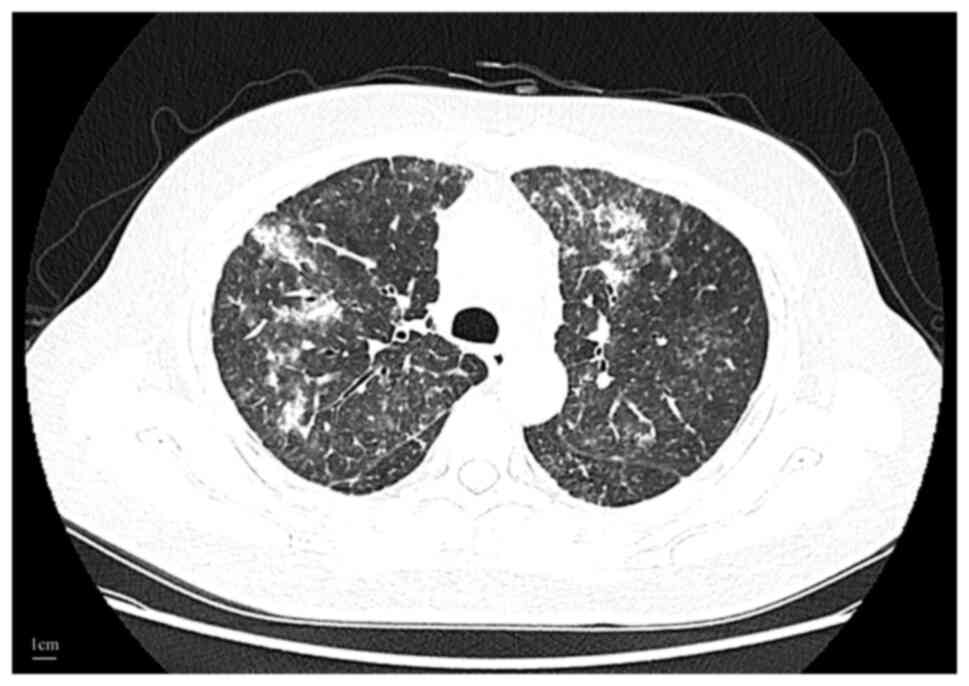

In August 2023, the patient presented with fever,

fatigue and a cough, requiring hospitalization. Chest CT revealed

minimal lung metastases alongside bilateral interstitial pneumonia

(Fig. 2). Laboratory investigations

revealed elevated serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP)

and serum amyloid A (SAA), reduced circulating T-cell

(CD4+ and CD8+) and B-cell (CD19+)

counts, and negative serum (1,3)-β-D-glucan (BG). Nucleic acid

amplification tests for SARS-CoV-2 and common respiratory viruses

returned negative results. Detailed laboratory results are

presented in Table I. The

laboratory findings indicate that the patient developed grade 3

lymphopenia, grade 1 neutropenia and anemia during abemaciclib

therapy. Bacterial pneumonia was initially suspected based on

clinical presentation and elevated inflammatory markers. Anticancer

therapy was discontinued, and the patient received levofloxacin

(750mg/day intravenous) combined with piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5

grams every 6 h intravenously) as empirical antimicrobial therapy

for 3 days.

| Table I.Laboratory data. |

Table I.

Laboratory data.

| Variable | Value (Pre-PJP

treatment) | Value (Post-PJP

treatment) | Reference

rangea |

|---|

| White-cell count,

/µl | 4,170 | 5,280 | 3,500-9,500 |

| Neutrophil count,

/µl | 2,790 | 5,370 | 1,800-6,300 |

| Lymphocyte count,

/µl | 590 | 1,260 | 1,100-3,200 |

| CD4+,

/Ul | 344 | 512 | 430-980 |

| CD8+,

/Ul | 199 | 287 | 380-670 |

| CD19+,

/Ul | 15 | 97 | 128-388 |

| C-reactive protein,

mg/l | 16.34 | 3.11 | 0.00–5.00 |

| Serum amyloid A,

mg/l | 90.97 | 9.09 | 0.00–10.00 |

| (1,3)-β-D-glucan | Negative | - | - |

|

Lipopolysaccharide | Negative | - | - |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Negative | - | - |

| Respiratory

syncytial virus | Negative | - | - |

| Adenovirus | Negative | - | - |

| Influenza

virus | Negative | - | - |

| Mycoplasma | Negative | - | - |

| Chlamydia | Negative | - | - |

| Legionella

pneumophila | Negative | - | - |

| Human

immunodeficiency virus | Negative | - | - |

After 3 days, the temperature of the patient

increased to 39.6°C with severe hypoxia (SpO2, 71% on

room air). High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy was initiated and

bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. Metagenomic

next-generation sequencing (mNGS) of BAL fluid identified P.

jirovecii and an ultra-high pathogen load (read counts of

>500 with 72.87% coverage). All other pathogens, including

bacteria, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Mycobacterium, parasites

and DNA viruses, were excluded using mNGS. No malignant cells were

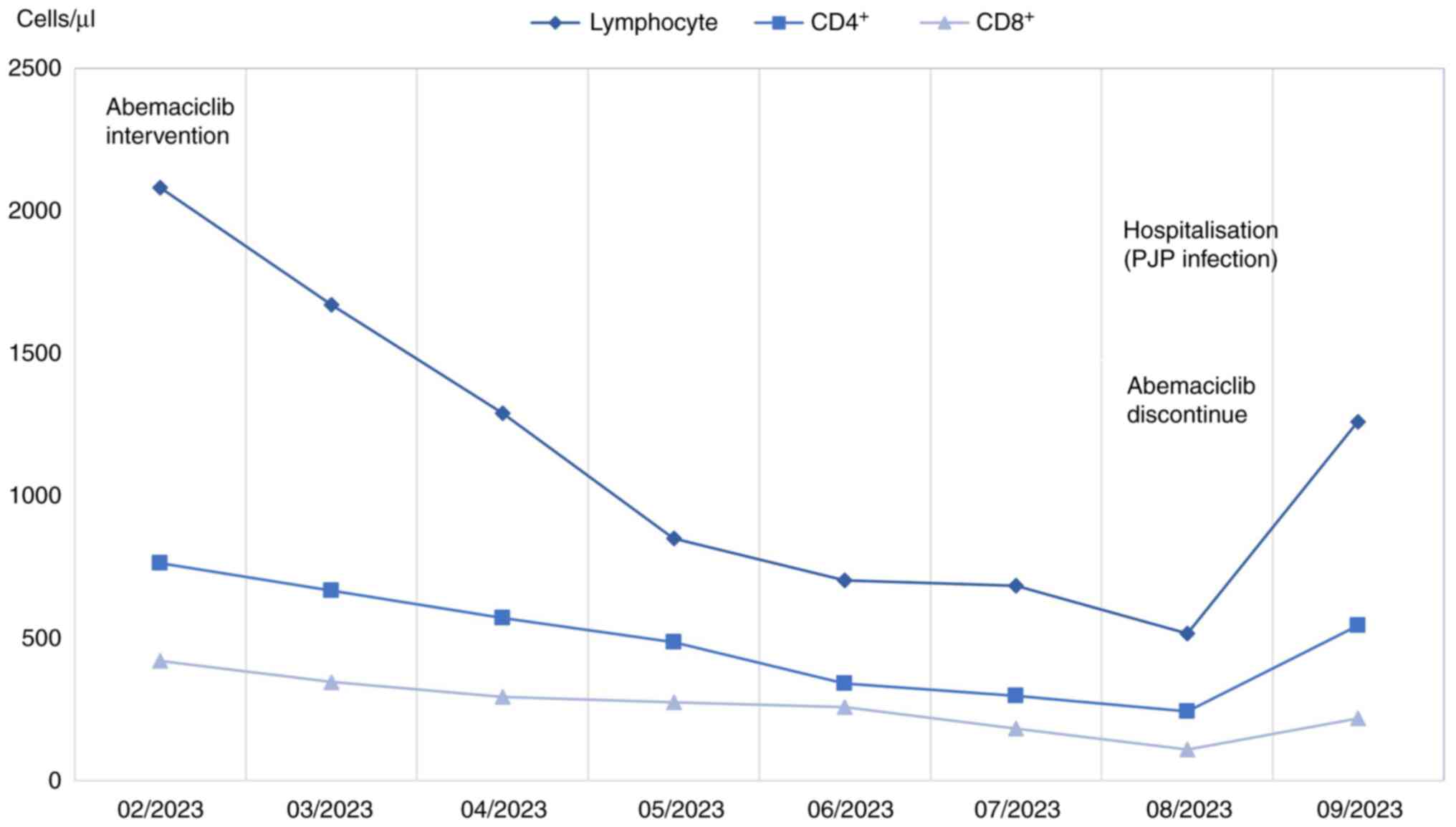

detected in the BAL specimen. The laboratory findings indicate that

the patient's lymphocyte count significantly decreased from

1.5×109/l pre-treatment to 0.5×109/l during

therapy, accompanied by a decline in CD4+ T-cells as

well (Fig. 3). Based on these

findings, a diagnosis of PJP was established and the therapeutic

regimen was switched to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX;

160/800 mg orally every 6 h). Concurrently, methylprednisolone was

administered at 500 mg daily. The fever resolved to 36.8°C after 4

days of targeted therapy. Clinical symptoms (cough, dyspnoea and

fatigue) and laboratory parameters (CRP, SAA and lymphocyte counts)

demonstrated gradual improvement during the first week (Table I). The patient was discharged for

outpatient management after 14 days of hospitalization. TMP/SMX was

continued for 21 days, whilst methylprednisolone was tapered and

discontinued over 4 weeks. The patient remained afebrile without

recurrence of fatigue, chest pain, dyspnoea or cough.

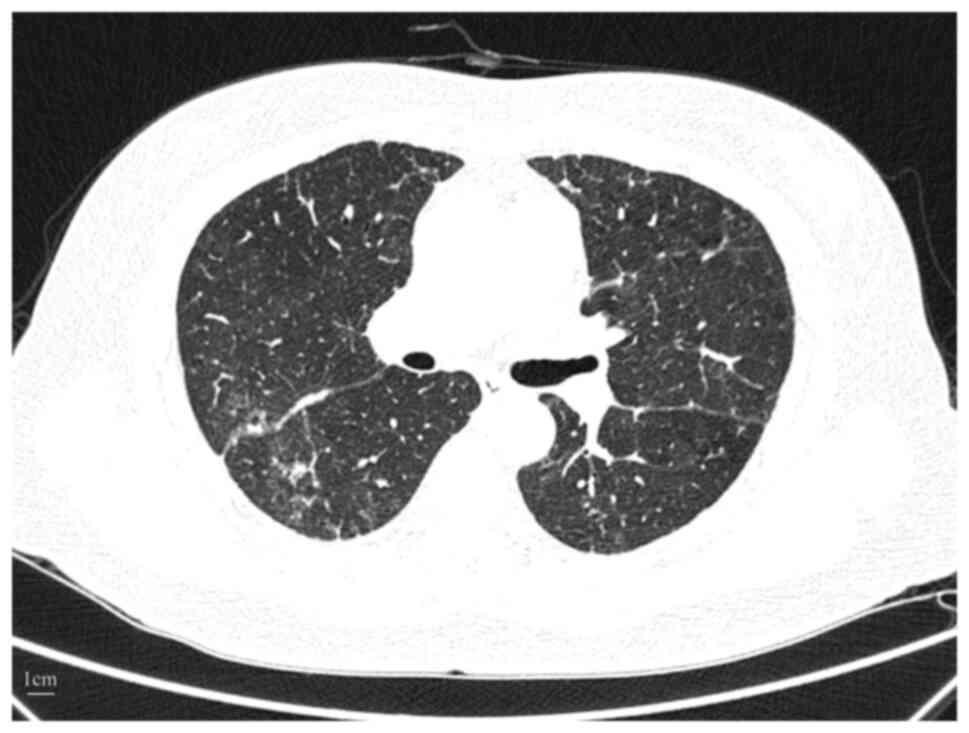

Follow-up chest CT after 1 month revealed partial

resolution of interstitial infiltrates (Fig. 4). Antitumor therapy was resumed 2

months later, with abemaciclib permanently discontinued in favor of

fulvestrant (500 mg intramuscular subcutaneously once monthly) +

goserelin (3.6 mg administered subcutaneously once monthly).

Discussion

The present report describes the first documented

case of PJP occurring in a patient with advanced breast cancer

receiving abemaciclib therapy, to the best of our knowledge.

Lymphopenia is established as an adverse effect of CDK4/6

inhibitors, including abemaciclib, palbociclib and ribociclib.

These agents operate through a shared mechanism of action targeting

CDK4/6, which regulates cell cycle progression in both malignant

cells and normal lymphocytes. CDK4/6 inhibitors serve a pivotal

role in regulating the G1-to-S phase transition during the cell

cycle, a process critical for T-cell clonal expansion following

activation (14). Abemaciclib

exerts potent inhibitory activity against CDK4/6, leading to

hypophosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein, sustained E2F

transcription factor suppression and resultant G1-phase cell cycle

arrest in lymphocytes (15). This

mechanism directly impairs T-cell proliferation and reduces

circulating lymphocyte counts. Notably, abemaciclib has been

associated with markedly higher incidences of severe lymphopenia

compared with palbociclib and ribociclib. This difference may

relate to the greater selectivity of abemaciclib for CDK4 over

CDK6, which could preferentially affect lymphocyte subsets

dependent on CDK4 signaling (16).

To date, there are no documented cases of PJP linked to palbociclib

or ribociclib use in the published literature, to the best of our

knowledge.

PJP is associated with elevated overall mortality in

hospitalized populations, and the present case underscores the

necessity of considering Pneumocystis as a differential

diagnosis in patients receiving abemaciclib who develop pulmonary

infections. PJP remains a predominant cause of pneumonia in

immunocompromised hosts, particularly among HIV-infected

individuals (17).

Lymphopenia is documented as a frequent AE in prior

clinical trials of abemaciclib. In the MONARCH 2 and 3 trials,

lymphopenia occurred in 52.7–62.9% of patients treated with

abemaciclib (compared with 25.6–31.7% with the placebo). Moreover,

7.9–12.2% developed grade ≥3 lymphopenia compared with 1.8% in the

control arm. Furthermore, MONARCH 2 reported a higher incidence of

any-grade infections in the abemaciclib group (42.6%) compared with

in the placebo group (24.7%), although infection types were not

characterized but predominantly low-grade. In MONARCH 3, pulmonary

infections represented the most common severe AE (2.8%), resulting

in three fatalities in the abemaciclib cohort. However, these

trials did not establish a statistically significant association

between infection risk and lymphopenia severity (7,8). In

the present case, the patient developed grade 3 lymphopenia, grade

1 neutropenia and anemia during abemaciclib therapy, suggestive of

myelosuppression. Neutropenia was mild and not considered the

primary etiology for PJP, and the endocrine agents letrozole and

goserelin administered concurrently have no documented association

with lymphopenia in prior studies (18,19).

Consequently, abemaciclib-induced lymphopenia was postulated as the

critical factor predisposing to PJP. Furthermore, despite the

negative HIV serology and absence of pre-existing immunosuppressive

comorbidities, the patient exhibited a marked reduction in

lymphocyte counts from 1.5 G/l pre-treatment to 0.5 G/l (August

2023), with CD4+ T-cell counts of 244 cells/µl during

abemaciclib therapy (Fig. 3). Such

profound lymphopenia likely induced immunosuppression, heightening

susceptibility to Pneumocystis infection.

Drug-induced interstitial lung disease (ILD) is

indeed a recognized AE of abemaciclib, and this possibility was

thoroughly considered in the present case. However, there are

distinct differences between ILD and PJP. Drug-induced ILD

typically manifests with low-grade fever (20), whereas the patient in the present

case exhibited a high fever of 39.6°C. Moreover, chest CT revealed

focal consolidation, whereas ILD typically presents with bilateral

symmetrical ground-glass opacities on imaging (21). The patient also showed rapid

clinical improvement following administration of TMP/SMX, whereas

ILD-related changes usually resolve more gradually, often requiring

corticosteroids (22). Based on

these findings, particularly the focal consolidation on CT, high

fever and dramatic response to anti-PJP therapy, a diagnosis of PJP

infection was strongly favored over drug-induced ILD in the present

case.

Diagnostic modalities for PJP include serum BG, PCR,

Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) staining and mNGS. In the present

case, serum BG was negative, and a negative serum BG result may

reflect insufficient β-glucan release during early-stage infection

(<48 h) (23). Whilst repeat

testing during the symptomatic peak is feasible, even a positive

result cannot specify the causative pathogen. Thus, mNGS was

performed for pathogen identification. mNGS is an untargeted,

broad-spectrum pathogen detection platform wherein total DNA/RNA

from clinical specimens undergoes high-throughput sequencing,

generating pathogen taxonomic data through alignment with reference

databases. This enables rapid, unbiased pathogen identification

without prior targeting. A single sequencing run can identify

diverse pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites

(24). Recent studies have reported

the diagnostic performance of mNGS for PJP, with sensitivity and

specificity of 92.3 and 87.4%, respectively (25,26).

Whilst mNGS exhibits comparable sensitivity with PCR, it

demonstrates superiority in detecting co-infections. Moreover,

although combined GMS staining and mNGS enhances diagnostic

accuracy to 96.2% (27), empiric

TMP/SMX therapy was promptly initiated in the present case, given

the risk of clinical deterioration during the diagnostic interval,

leading to rapid symptomatic resolution. Moreover, to avoid

incurring additional costs, GMS and PCR were not performed.

Lymphopenia, akin to neutropenia, compromises immune

function, rendering the host susceptible to bacterial, viral and

other pathogenic invasions. This elevates the risk of infections,

potentially culminating in fatal outcomes. Whilst standardized

approaches exist for detecting and managing abemaciclib-induced

neutropenia (28), evidence-based

protocols for identifying and mitigating abemaciclib-associated

lymphopenia remain deficient. Currently, there are no established

protocols for discontinuing treatment, adjusting doses or offering

symptomatic care after lymphopenia, thereby notably elevating the

risk of opportunistic infections such as PJP.

In conclusion, the present case demonstrates that

lymphopenia is a common and clinically significant AE associated

with abemaciclib therapy. Therefore, routine surveillance of

absolute lymphocyte counts (ALC) and CD4+ T-cell subsets

is warranted during abemaciclib treatment. PJP prophylaxis should

be considered in patients exhibiting persistent lymphopenia (ALC,

<0.5×109/l) or CD4+ T-cell depletion

(<300 cells/µl), particularly when concomitant risk factors

exist, including concomitant immunosuppressive agents or

pre-existing immunodeficiencies. The preferred regimen is oral

TMP/SMX (160/800 mg) once daily; for patients intolerant to

TMP/SMX, oral dapsone (100 mg once daily or 50 mg twice daily) may

be administered as an alternative. Clinicians should monitor for

hematologic toxicities associated with TMP/SMX and dapsone, both of

which are associated with a risk of neutropenia (29,30).

Co-administration with abemaciclib may amplify the risk and

severity of neutropenia, necessitating vigilant hematologic

surveillance. Additionally, abemaciclib is predominantly

metabolized by CYP3A4, whereas TMP/SMX is primarily metabolized via

CYP2C9/CYP2C19, and dapsone via CYP2E1/CYP2C. Consequently, no dose

adjustment of abemaciclib is required when used concomitantly with

these medications (31–33).

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Science and Technology

Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant no. 20Z21900300).

Availability of data and materials

The mNGS data generated in the present study may be

found in the figshare database under accession number 29591006 or

at the following URL: https://figshare.com/s/88124d28658523f8f3f9. The

personal information of the patient is anonymized for privacy

protection.

Authors' contributions

WH and SL was involved in the study's

conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation and

writing - original draft preparation. YQ participated in the

study's conceptualization and contributed by performing patient

follow-up, writing-reviewing and editing and supervision. CS was

involved in data acquisition. CW and JB were involved in patient

follow-up. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. WH, SL, YQ, CS, CW and JB confirm the authenticity of

all raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written and signed consent was obtained from the

patient to publish their history, images, clinical data and other

data included in the present manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhou S and Aitken SL: Prophylaxis against

pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in adults. JAMA. 330:182–183.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Masur H, Brooks JT, Benson CA, Holmes KK,

Pau AK and Kaplan JE; National Institutes of Health, Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention HIV Medicine Association of the

Infectious Diseases Society of America, : Prevention and treatment

of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents:

Updated guidelines from the centers for disease control and

prevention, national institutes of health, and HIV medicine

association of the infectious diseases society of America. Clin

Infect Dis. 58:1308–1311. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gilroy SA and Bennett NJ: Pneumocystis

pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 32:775–782. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang Y, Zhou X, Saimi M, Huang X, Sun T,

Fan G and Zhan Q: Risk factors of mortality from pneumocystis

pneumonia in non-HIV patients: A meta-analysis. Front Public

Health. 9:6801082021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jerzak KJ, Bouganim N, Brezden-Masley C,

Edwards S, Gelmon K, Henning JW, Hilton JF and Sehdev S: HR+/HER2-

Advanced breast cancer treatment in the first-line setting: Expert

review. Curr Oncol. 30:5425–5447. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cooley L, Dendle C, Wolf J, Teh BW, Chen

SC, Boutlis C and Thursky KA: Consensus guidelines for diagnosis,

prophylaxis and management of pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in

patients with haematological and solid malignancies, 2014. Intern

Med J. 44:1350–1363. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Johnston SRD, Harbeck N, Hegg R, Toi M,

Martin M, Shao ZM, Zhang QY, Martinez Rodriguez JL, Campone M,

Hamilton E, et al: Abemaciclib combined with endocrine therapy for

the adjuvant treatment of HR+, HER2-, node-positive, high-risk,

early breast cancer (monarchE). J Clin Oncol. 38:3987–3998. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sledge GW Jr, Toi M, Neven P, Sohn J,

Inoue K, Pivot X, Burdaeva O, Okera M, Masuda N, Kaufman PA, et al:

MONARCH 2: Abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant in women

with HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer who had progressed while

receiving endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol. 35:2875–2884. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Goetz MP, Toi M, Campone M, Sohn J,

Paluch-Shimon S, Huober J, Park IH, Trédan O, Chen SC, Manso L, et

al: MONARCH 3: Abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast

cancer. J Clin Oncol. 35:3638–3646. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Patnaik A, Rosen LS, Tolaney SM, Tolcher

AW, Goldman JW, Gandhi L, Papadopoulos KP, Beeram M, Rasco DW,

Hilton JF, et al: Efficacy and safety of abemaciclib, an inhibitor

of CDK4 and CDK6, for patients with breast cancer, non-small cell

lung cancer, and other solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 6:740–753.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu Y, Wu J, Ji Z, Zhao Y, Li S, Li J,

Chen L, Zou J, Zheng J, Lin W, et al: Comparative efficacy and

safety of different combinations of three CDK4/6 inhibitors with

endocrine therapies in HR+/HER-2- metastatic or advanced breast

cancer patients: A network meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 23:8162023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lombardo JF: American society of clinical

oncology/college of American pathologists guidelines should be

scientifically validated. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 131:1510–1511. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Guillaume Z, Medioni J, Lillo-Lelouet A,

Marret G, Oudard S and Simonaggio A: Severe cellular

immunodeficiency triggered by the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib.

Clin Breast Cancer. 20:e192–e195. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Deng J, Wang ES, Jenkins RW, Li S, Dries

R, Yates K, Chhabra S, Huang W, Liu H, Aref AR, et al: CDK4/6

inhibition augments antitumor immunity by enhancing T-cell

activation. Cancer Discov. 8:216–233. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gebbia V, Valerio MR, Firenze A and

Vigneri P: Abemaciclib: Safety and effectiveness of a unique

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. Expert Opin Drug Saf.

19:945–954. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Weyant RB, Kabbani D, Doucette K, Lau C

and Cervera C: Pneumocystis jirovecii: A review with a focus on

prevention and treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 22:1579–1592.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ruhstaller T, Giobbie-Hurder A, Colleoni

M, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, de Azambuja E, Neven P, Láng I, Jakobsen

EH, Gladieff L, et al: Adjuvant letrozole and tamoxifen alone or

sequentially for postmenopausal women with hormone

receptor-positive breast cancer: Long-term follow-up of the BIG

1–98 trial. J Clin Oncol. 37:105–114. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Pagani O, Francis PA, Fleming GF, Walley

BA, Viale G, Colleoni M, Láng I, Gómez HL, Tondini C, Pinotti G, et

al: Absolute improvements in freedom from distant recurrence to

tailor adjuvant endocrine therapies for premenopausal women:

Results from TEXT and SOFT. J Clin Oncol. 38:1293–1303. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Spagnolo P, Bonniaud P, Rossi G,

Sverzellati N and Cottin V: Drug-induced interstitial lung disease.

Eur Respir J. 60:21027762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pipavath S and Godwin JD: Imaging of

interstitial lung disease. Clin Chest Med. 25:455–465. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Conte P, Ascierto PA, Patelli G, Danesi R,

Vanzulli A, Sandomenico F, Tarsia P, Cattelan A, Comes A, De

Laurentiis M, et al: Drug-induced interstitial lung disease during

cancer therapies: Expert opinion on diagnosis and treatment. ESMO

Open. 7:1004042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Damiani C, Demey B, Pauc C, Le Govic Y and

Totet A: A negative (1,3)-β-D-glucan result alone is not sufficient

to rule out a diagnosis of pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with

hematological malignancies. Front Microbiol. 12:7132652021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu Y, Wang X, Xu J, Yang Q, Zhu H, Liu Y

and Yang J: Diagnostic value of metagenomic next-generation

sequencing of lower respiratory tract specimen for the diagnosis of

suspected pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Ann Med.

55:22323582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang JZ, Wang JB, Yuan D, Sun CH, Hou LL,

Zhang Y, Yang XH, Xie HX and Gao YX: Metagenomic next-generation

sequencing-based diagnosis of pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in

patients without human immunodeficiency virus infection: A

dual-center retrospective propensity matched study. J Infect Public

Health. 18:1028312025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li X, Li Z, Ye J and Ye W: Diagnostic

performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for

pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis. 23:4552023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Pang Y, Qiu J, Yang H, Zhang J, Mo J,

Huang W, Zeng C and Xu P: Application value of metagenomic

next-generation sequencing based on protective bronchoalveolar

lavage in nonresponding pneumonia. Microbiol Spectr.

13:e03138242025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Spring LM, Zangardi ML, Moy B and Bardia

A: Clinical management of potential toxicities and drug

interactions related to cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors in

breast cancer: Practical considerations and recommendations.

Oncologist. 22:1039–1048. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen JK, Guerci J, Corbo H, Richmond M and

Martinez M: Low-dose TMP-SMX for pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

prophylaxis in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients. J

Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 28:123–128. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hsieh CY and Tsai TF: Drug-induced

neutropenia during treatment of non-neoplastic dermatologic

diseases: A review. Clin Drug Investig. 40:915–926. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wolf R, Matz H, Orion E, Tuzun B and Tuzun

Y: Dapsone. Dermatol Online J. 8:22002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huang YS, Tseng SY, Chang TE, Perng CL and

Huang YH: Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim-induced liver injury and

genetic polymorphisms of NAT2 and CYP2C9 in Taiwan. Pharmacogenet

Genomics. 31:200–206. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Posada MM, Morse BL, Turner PK,

Kulanthaivel P, Hall SD and Dickinson GL: Predicting clinical

effects of CYP3A4 modulators on abemaciclib and active metabolites

exposure using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. J

Clin Pharmacol. 60:915–930. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|