Introduction

The lymphatic system serves dual roles in fluid

homeostasis and immune surveillance, which functions as a key

component of both the circulatory and immune systems. As part of

the circulatory network, it maintains tissue fluid balance by

draining ~2–4 l of protein-rich interstitial fluid on a daily basis

through specialized vessels equipped with intrinsic contractility

and unidirectional valves. Concurrently, its immune functions

facilitate antigen presentation and lymphocyte trafficking via

lymph node filtration (1).

Lymphedema, which is pathologically defined as the abnormal

accumulation of high-protein interstitial fluid (2), arises from either primary

developmental abnormalities or secondary acquired damage. Primary

lymphedema typically manifests through genetic mutations affecting

lymphatic morphogenesis (2) and is

diagnosed via combined lymphoscintigraphy findings and molecular

testing (3). Secondary forms are

identified via clinical history (including histories of surgery,

radiation or filariasis) and imaging evidence of lymphatic

obstruction, with CT/MRI indicating characteristic dermal backflow

patterns (4–6).

Although the proportion of lymphoma-associated

lymphedema in secondary lymphedema is relatively low (7), the association between lymphedema and

lymphoma exhibits distinctive clinical features, including rapid

unilateral progression, disproportionate truncal involvement and

concurrent B symptoms. For the present study, the accumulation of

11 cases over 17 years reflects both the specialization in

lymphatic disorders at Beijing Shijitan Hospital (managing

>1,200 patients with lymphedema on an annual basis) and improved

diagnostic sensitivity via advanced imaging protocols. The present

case series addresses a key literature gap, as previous reports

lacked standardized diagnostic criteria, of which only 4 out of 19

previous cases documented imaging correlates (Table I) (8–26).

These findings establish essential clinical benchmarks to

distinguish malignancy-related edema from benign edema.

| Table I.Previous case reports of

lymphoma-associated lymphedema. |

Table I.

Previous case reports of

lymphoma-associated lymphedema.

| First author,

year | Cases, n | Patient age,

years/sex | Duration of

edema | Localization of

edema | Accompanied

symptoms | Past history | Diagnostic

findings | Histological

types | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Present study | Case 1 | 72/M | 2 months | Lower extremity | None | None | CT enhancement:

Multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the groin, pelvic cavity and

retroperitoneum | Angioimmunoblastic

T-cell lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 2 | 74/M | 1 month | Upper

extremity | Axillary mass | None | CT enhancement:

Multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the left axilla, with notable

delayed enhancement, splenic space- occupying lesions and multiple

lymph nodes of varying sizes in the mediastinum | Lymphoplasmacytic

lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 3 | 53/M | 7 months | Lower

extremity | Groin mass | None | CT: Multiple

enlarged lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum | Follicular

lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 4 | 41/F | 10 months | Lower

extremity | Enlargement of the

supraclavicular lymph nodes | History of

accessory breast surgery >20 years, history of hysteromyoma

>2 years, history of hysteroscopic surgery >1 year | CT: Multiple lymph

nodes on the lesser curvature of the stomach. Malignant mass in the

upper lobe of the right lung, lymph node metastasis in the right

hilum and mediastinum and multiple metastatic nodules under the

anterior chest wall | B-cell lymphoma,

unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin's lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 5 | 62/F | 3 months | Lower

extremity | Abdominal pain and

enlargement of cervical and inguinal lymph nodes | None | CT: The root of the

mesentery, retroperitoneum to bilateral iliac masses, multiple

enlarged lymph nodes in both inguinal regions and local compression

and narrowing of the inferior vena cava. The lower end of the left

ureter is compressed and narrowed and the upper ureter and left

renal pelvis and calyx are dilated with hydronephrosis. Multiple

nodules in the spleen, considering metastatic lesions. Multiple

enlarged lymph node shadows in the upper and lower regions of both

clavicles, mediastinum and axilla, with metastatic lesions not

excluded | Follicular

lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 6 | 79/M | 8 months | Lower

extremity | Enlargement of

cervical lymph node | None | Ultrasound:

Bilateral cervical lymph nodes visible | Diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 7 | 52/M | 2 years | Generalized

edema | Enlargement of

lymph nodes in neck, armpit and groin and recurrent fever | None | Ultrasound:

Multiple lymph node enlargement in both inguinal regions. Bilateral

cervical lymph nodes are visible | Angioimmunoblastic

T-cell lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 8 | 46/M | 2 months | Lower extremity and

perineal region | Enlargement of

inguinal lymph node | None | Ultrasound:

Bilateral inguinal lymph node enlargement | Follicular

lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 9 | 73/F | 2 years | Lower

extremity | None | History of

endometrial cancer | CT enhancement:

Multiple small nodules in the right lung. Multiple swollen lymph

nodes in both armpits | Angioimmunoblastic

T-cell lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 10 | 64/M | 9 months | Lower

extremity | Enlargement of

inguinal lymph node and loss of weight | None | Null | Diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma | - |

| Present study | Case 11 | 55/M | 1 month | Lower

extremity | Enlargement of

inguinal lymph node | None | CT: A small amount

of hydrocele is present in both testicles and there is swelling in

both inguinal regions and left external iliac lymph nodes. It is

recommended to rule out tumor lesions | Diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma | - |

| Sun, 2022 | Case 12 | 69/F | 40 years | Lower

extremity | Multiple nodules of

varying sizes, the surface of some of the lesions demonstrated

erosion and exudation, with pain. | None | Null | Diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma | (8) |

| Vijaya, 2019 | Case 13 | 47/F | 47 years | Lower

extremity | Multiple ulcers and

nodules | Null | Null | Diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma | (9) |

| Sanna, 1997 | Case 14 | 84/F | 7 months | Lower

extremity | None | History of

coxarthrosis | Null | Angiotropic large

B-cell lymphoma | (10) |

| González-Vela,

2008 | Case 15 | 89/M | 7 years | Lower

extremity | Multiple

violaceous, firm, slightly infiltrated nodules | History of a right

femoropopliteal bypass | None | Diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma | (11) |

| Hills, 1993 | Case 16 | 55/M | 47 years | Lower extremity and

the right hand | Multiple firm

purplish-blue cutaneous nodules | History of a

deep-vein thrombosis of the left leg and pulmonary embolus | None | Follicular centre

cell lymphoma | (12) |

| Dargent, 2005 | Case 17 | 79/F | 28 years | Upper

extremity | A cutaneous tumor

of ~2 cm width | History of chronic

arterial hypertension, ischemic cardiomyopathy, hepatitis,

cholecystectomy, left ovariectomy, hysteropexy for cystocele

repair, varicose vein stripping and depression | None | Diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma | (13) |

| Shabbir, 2022 | Case 18 | 71/M | Several weeks | Upper

extremity | None | An extensive

history of tobacco and substance use in remission and untreated HCV

infection | A CT scan of the

RUE demonstrated cortical destruction Of the humeral head and

proximal shaft, along with infiltrative enlargement of the muscles

of the proximal RUE and marked soft tissue edema. There were also a

few enlarged axillary lymph nodes, the largest Measuring 2 cm in

short-axis. A PET scan demonstrated striking 18-FDG avidity in the

humerus and surrounding musculature (msuv 10–15), as well as two

FDG-avid axillary lymph nodes with msuv 5 and 14 | Diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma | (14) |

| Massini, 2013 | Case 19 | 45/F | Null | Upper

extremity | Purplish cutaneous

nodules, in part ulcerated and infected | Null | None | Mantle cell

lymphoma | (15) |

| Wan and Jiao,

2013 | Case 20 | 33/M | 3 years | Lower

extremity | Leg pain, flank

pain, oliguria and dark urine | Smoking

history | Vascular ultrasound

revealed segmental occlusion of inferior vena cava and

hypoechogenic lesion around abdominal aorta, bilateral sacral

arteries and right renal artery. Inguinal ultrasound found

bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy and a hypoechoic mass in the

left inguinal region. Abdominal CT scan with contrast revealed a

retroperitoneal soft-tissue mass, which invaded the right kidney

and surrounded the abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava, superior

mesenteric artery and bilateral renal vessels (Fig. 2). Left renal pelvic and bilateral

psoas major muscles were also involved. CT urography revealed

hydronephrosis, with occlusion of right renal pelvis and right

ureter. A renal scan indicated the glomerular filtration rate to be

9.46 (left) and 65.39 ml/min (right) | Non-Hodgkin's

lymphoma of B-cell type | (16) |

| Tatnall and Mann,

1985 | Case 21 | 76/M | 3 years | Lower

extremity | Leg skin

nodules | History of prostate

cancer | Null | Non-Hodgkin's

lymphoma | (17) |

| Barki, 2020 | Case 22 | 60/M | Null | Penile scrotum | Fever, weight

loss | Null | Ultrasound imaging

indicated a thickening of the scrotum with normal scrotal contents.

CT: Bilateral upper and centrilobular pulmonary emphysema, large

lateral aortic, common iliac and left external iliac

lymphadenopathies | Hodgkin's

lymphoma | (18) |

| Paydas, 2000 | Case 23 | 63/F | Null | Upper

extremity | Skin induration and

ulceration ranging from 0.5 to 1 cm on the dorsum of her left hand

and arm | Null | Null | Diffuse large cell

lymphoma | (19) |

| Fan, 2017 | Case 24 | 56/M | 10 years | Lower

extremity | Erythema on the

right leg, multiple nodular ulcerative lesions | Null | Null | Primary cutaneous

anaplastic large cell lymphoma | (20) |

| Torres-Paoli

Sánchez, 2000, | Case 25 | 87/F | 67 years | Lower

extremity | Painful

nodules | History of

filariasis | None | Primary cutaneous

B-cell lymphoma | (21) |

| Waxman, 1984 | Case 26 | 76/M | 1.5 years | Upper

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Primary B-cell

lymphoma (?) | (22) |

| d'Amore, 1990 | Case 27 | 55/F | 30 years | Upper

extremity | Severe pain in the

left arm, a lesion of the soft tissue surrounding the upper

humerus | Null | Radiographic

studies demonstrated a large mass involving the left biceps and

triceps muscles; the underlying cortical bone was also focally

involved in this process | Primary B-cell

lymphoma | (23) |

| d'Amore, 1990 | Case 28 | 70/F | 11 years | Upper

extremity | A slowly growing,

violaceous soft-tissue nodule in the right deltoid region | Null | Null | Primary B-cell

lymphoma | (23) |

| Binjawhar,

2021 | Case 29 | 27/M | 3 years | Scrotum | None | Null | Null | Hodgkin's

lymphoma | (24) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 30 | 49/M | 6 months | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 31 | 63/M | 6 weeks | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 32 | 57/F | Null | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 33 | 57/F | 1 month | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 34 | 75/F | 3 months | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 35 | 68/F | 1 day | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 36 | 56/F | Several weeks | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 37 | 64/M | 5 months | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 38 | 59/F | 3 years | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Hawkins, 1980 | Case 39 | 16/F | 1 year | Lower

extremity | Null | Null | Null | Lymphoma | (25) |

| Elgendy, 2014 | Case 40 | 60/M | Several weeks | Lower

extremity | Mild erythema,

increased warmth and moderate tenderness of the left leg | Hyperlipidaemia and

hypertension | A CT scan of the

abdomen and pelvis demonstrated left aortic lymphadenopathy and

bulky lymphadenopathies alongside the left iliac vessels, extending

to the left inguinal region with compression of the left iliac

vein | Non-Hodgkin's

lymphoma | (26) |

Case report

From May 2007 to December 2024, a cohort of 11

patients suffering from lymphedema (either induced or exacerbated

by lymphoma) received treatment at Beijing Shijitan Hospital

(Beijing, China). Following the acquisition of approval from the

institutional review board [approval no. sjtkyll-lx-2022(058)], a

retrospective analysis of these 11 patients was conducted. In the

present case report, a cohort of 11 patients diagnosed with

lymphedema underwent a series of diagnostic evaluations, including

laboratory tests (blood routine examination, blood tumor marker

examination), ultrasonography, MRI, CT and radionuclide imaging.

The imaging findings involved characterizations of

ultrasound-assessed lymph node size (short-axis diameter >10 mm

defined as being abnormal), vascularity and soft-tissue edema. CT

was used to evaluate lymphadenopathy (axial diameter >15 mm),

visceral/organ involvement and tumor masses. MRI was used to

characterize soft-tissue infiltration and lymphatic obstruction

patterns, as well as to differentiate between edema and neoplastic

infiltration. Additionally, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were

performed to corroborate the diagnosis of malignancy (27).

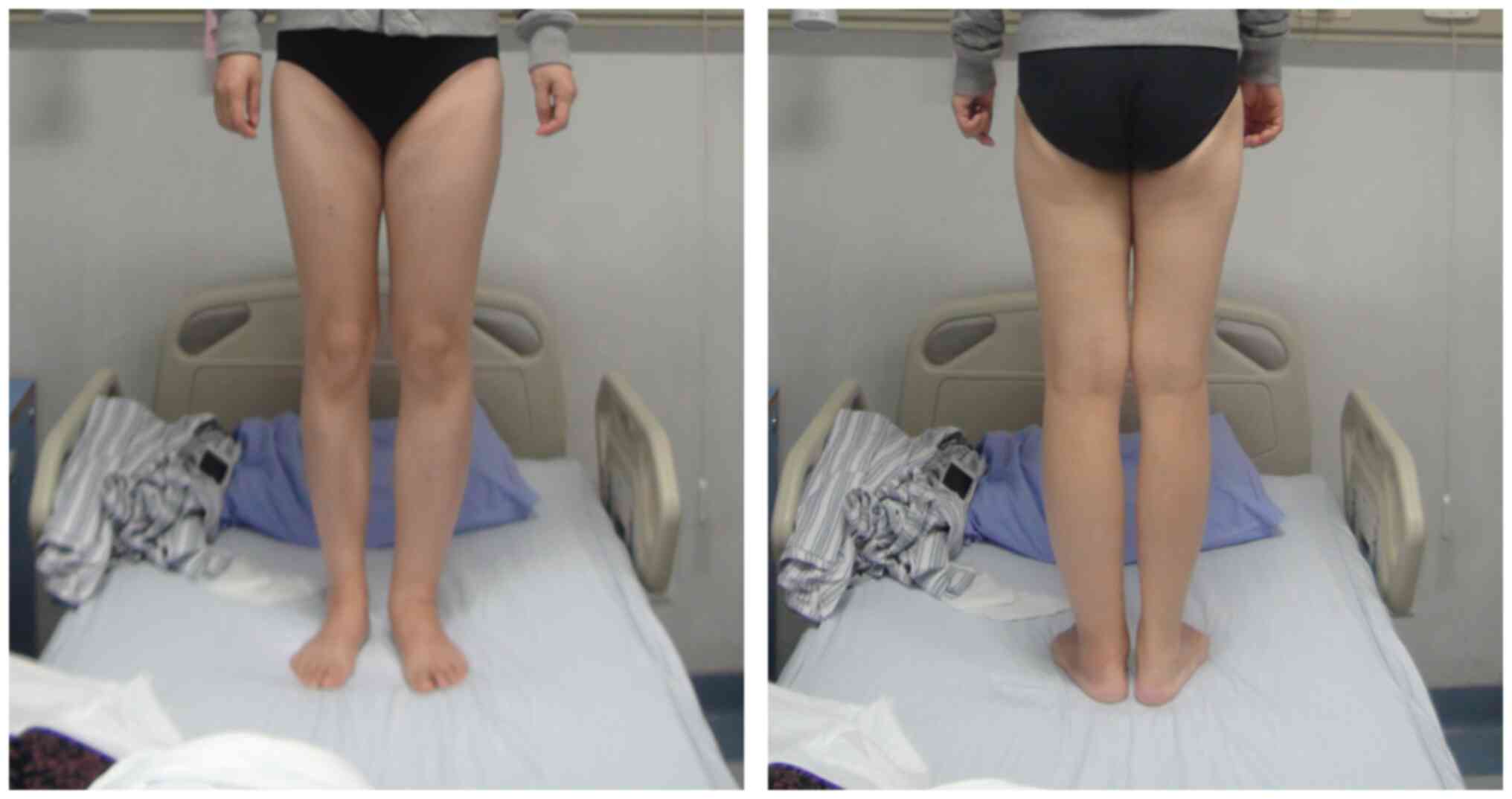

The cohort of 11 patients included 8 men and 3

women. The distribution of lymphedema types included 1 patient with

upper extremity lymphedema, 9 patients with lower extremity

lymphedema (Fig. 1) and 1 patient

with systemic edema. The ages of the patients with lymphoma ranged

from 41 to 79 years, with a mean age of 61.0±12.5 years. The

interval between the onset of lymphedema and the subsequent

diagnosis of lymphoma varied from 1 to 24 months, with a median

duration of 7 months. Additionally, these patients presented with

various clinical symptoms, including weakness, weight loss, pain,

the presence of a mass and lymphadenopathy. A detailed summary of

the clinical features of each patient is provided in Table I.

In the present cohort, tumor markers were assessed

in 6 patients, with 66.7% (4 out of 6) of the patients exhibiting

abnormalities in at least one marker. The distribution of abnormal

markers included CA125 (1 patient), urinary Igκ light chain (3

patients), serum β2-microglobulin (1 patient), urinary Igλ light

chain (2 patients), serum Igκ light chain (2 patients) and urinary

β2-microglobulin (1 patient). Individual patients often presented

with multiple marker abnormalities (Table II). Additionally, the prevalence of

anemia among patients diagnosed with malignant lymphedema was 45.5%

(5 out of 11 patients). Several suspicious lesions were further

evaluated via imaging modalities, which yielded positive detection

rates of 100.0% for ultrasonography (7 out of 7 lesions), 100.0%

for CT (8 out of 8 lesions) and 100.0% for MRI (2 out of 2

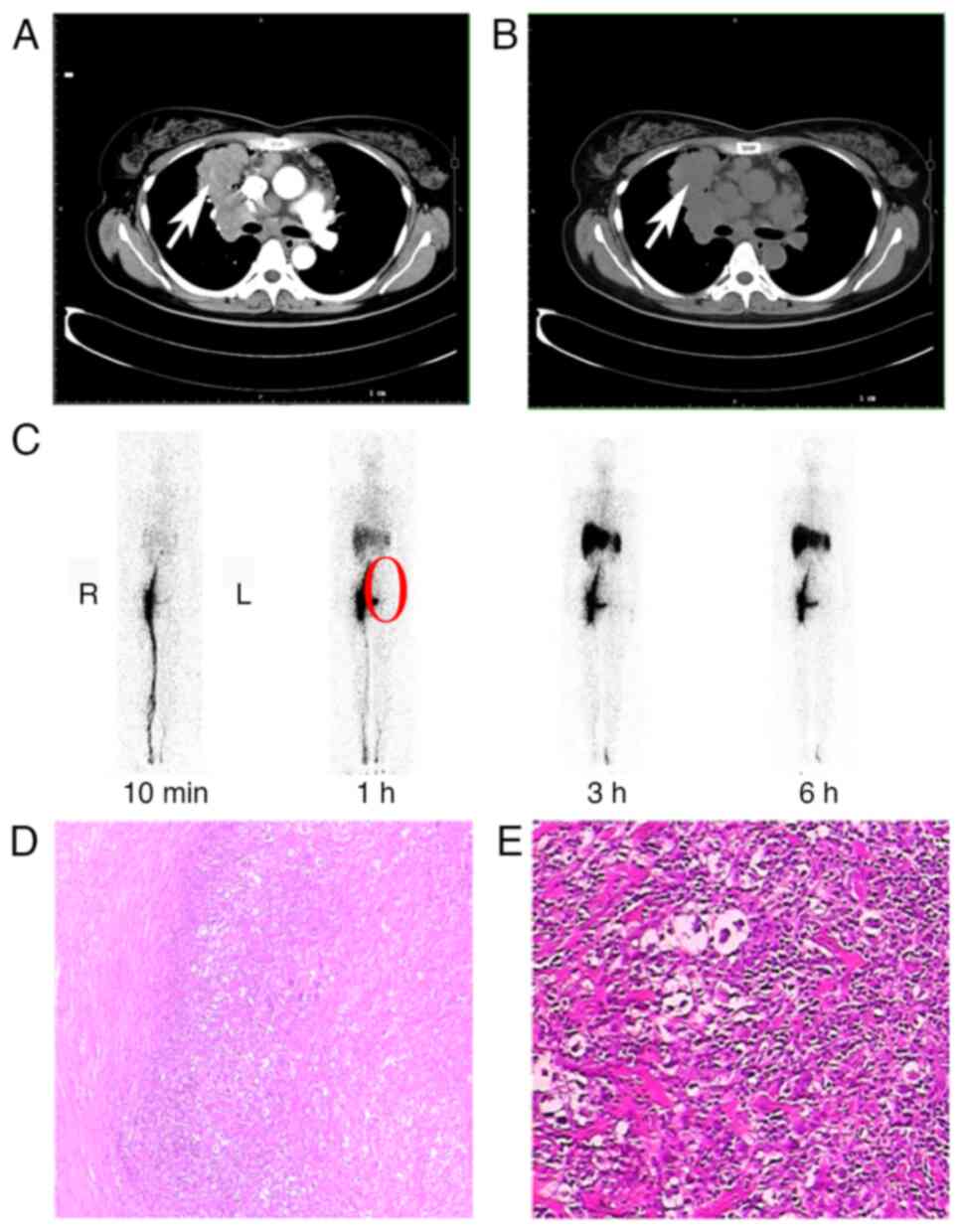

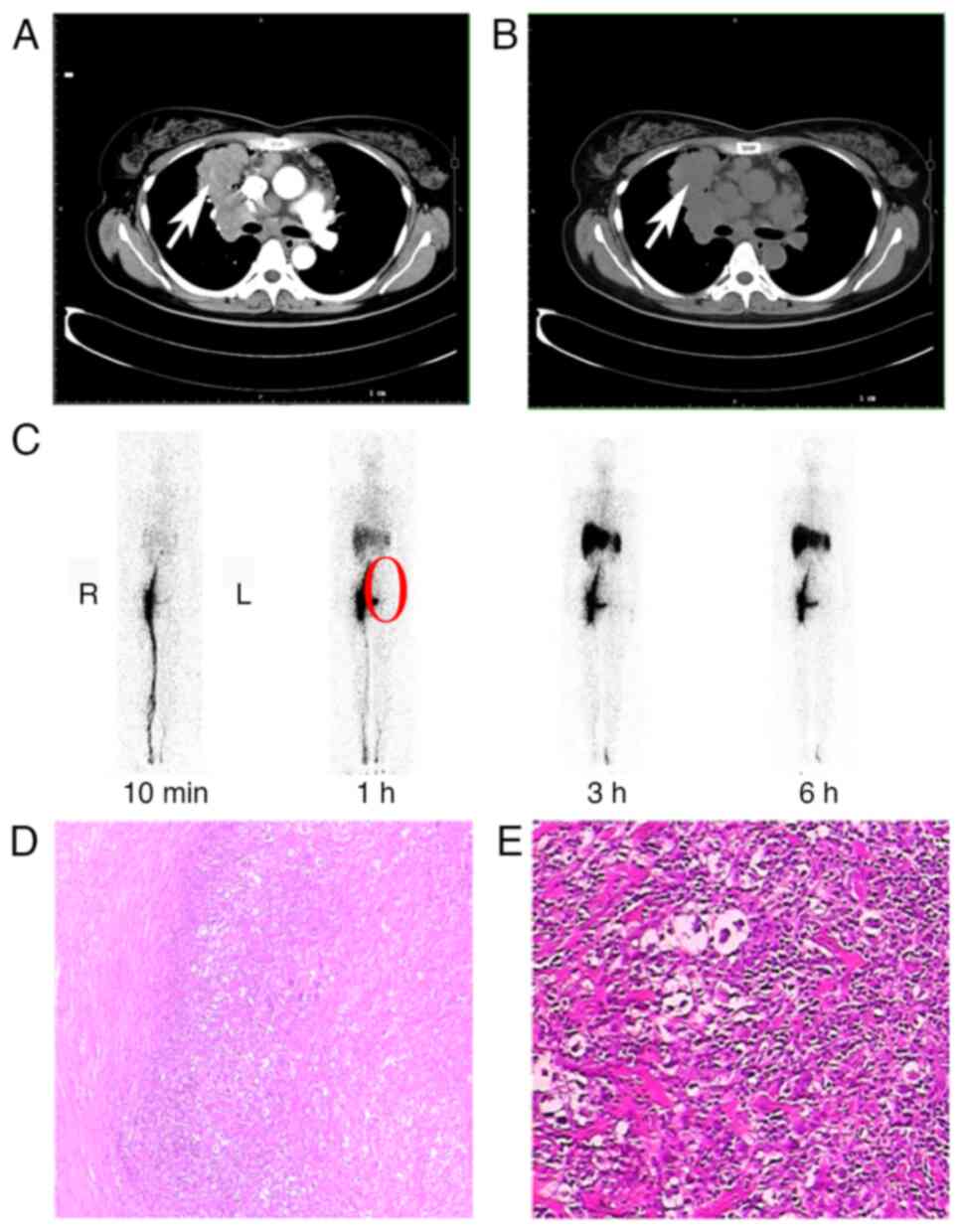

lesions). Representative imaging and pathology findings from Case 4

are shown in Fig. 2. Axial chest CT

demonstrated a mass adjacent to the mediastinum involving the right

lung hilum and upper lobe. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed this mass

exhibited heterogeneous enhancement and was contiguous with a

larger mediastinal mass, confirming their connection. Whole-body

lymphoscintigraphy following foot injection showed mild left lower

limb thickening, significant tracer retention at the left foot

injection site suggesting impaired lymphatic drainage, and

non-visualization (absence of uptake) in the left inguinal, iliac

and para-aortic/lumbar nodal basins, indicating lymphatic

obstruction in these regions. Histopathological examination of the

dissected left supraclavicular lymph node (H&E stain) revealed

effacement of nodal architecture with fibrosis, scattered lymph

follicles, large cells and histiocyte-like cells. The morphology

led to the diagnosis of ‘B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with

features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and

classical Hodgkin lymphoma’.

| Figure 2.Case 4. (A) Chest CT scan. This axial

CT image demonstrates a mass lesion (indicated by the white arrow)

located adjacent to the mediastinum, specifically involving the

right lung hilum and upper lobe (each mark on the scale bar

corresponds to one centimeter). (B) The contrast-enhanced axial CT

image (same level as 2A) reveals that the right hilar/upper lobe

mass (white arrow) exhibits heterogeneous (‘uneven’) enhancement

and is contiguous with a larger mediastinal mass, confirming their

connection. (Each mark on the scale bar corresponds to one

centimeter). (C) Whole-body lymphoscintigraphy image showing tracer

distribution following injection in the feet. Key findings include

the following: i) Mild thickening of the left lower limb, ii)

significant retention of the radiotracer (‘imaging agent’) at the

injection site in the left foot (suggesting impaired lymphatic

drainage), and iii) non-visualization (absence of tracer uptake) in

the left inguinal, iliac and para-aortic/lumbar lymph node basins

(highlighted by the red circle), indicating lymphatic obstruction

or dysfunction in these regions. (D and E) Pathology-left

supraclavicular lymph node: Photomicrographs of histopathological

sections from the dissected left supraclavicular lymph node (D)

magnification, ×200; (E) magnification, ×400 (H&E stain). The

morphology is diagnostic of ‘B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with

features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and

classical Hodgkin lymphoma’. The lymph node structure is unclear,

with no subcapsular sinus observed. Fibrosis is evident and

scattered lymph follicles and nodular lymphoid tissue are visible.

In E, large cells and dry corpse-like cells are scattered within,

with some presenting as histiocyte-like. |

| Table II.Tumor marker profiles in patients

with abnormal results. |

Table II.

Tumor marker profiles in patients

with abnormal results.

| Patient no. | CA125, U/ml

(normal, <35) | Serum β2-MG, mg/l

(normal, 1.09–2.53) | Urinary β2-MG, mg/l

(normal, <0.20) | Serum Igκ, g/l

(normal, 1.70–3.70) | Serum Igλ, g/l

(normal, 0.90–2.10) | Urinary Igκ, mg/l

(normal, <7.91) | Urinary Igλ, mg/l

(normal, <4.09) |

|---|

| 3 | - | 4.05a | 1.40a | - | - | 22.40a | 4.34a |

| 4 | 53.60a | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | - | - | - | 1.68a | - | 20.60a | 4.18a |

| 11 | - | - | - | 3.75a | - | 8.26a | - |

A total of 11 cases of lymphedema associated with

malignant tumors were pathologically verified to have originated

from the lymphatic tissue. The present cohort included 8 cases of

mature B-cell lymphoma and 3 cases of mature T-cell lymphoma, as

detailed in Table I and Fig. 2.

Furthermore, 11 patients underwent tumor and

enlarged lymph node resection biopsies. A total of 6 patients were

followed up until December 2024. Of note, 2 patients with vascular

immune T-cell lymphoma died within 1 year after diagnosis. A total

of 3 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma were diagnosed and

received chemotherapy (the specific details are unknown). These

patients have survived for 7, 10 and 11 years. In addition, 1

patient with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma has been receiving

long-term oral treatment with traditional Chinese medicine (the

specific details are unknown) and has survived for 14 years

(Table I).

Discussion

The clinical presentations of lymphoma can vary and

a notable number of cases are identified at an advanced stage,

which is primarily due to the constraints of existing diagnostic

methodologies (28). In certain

patients, lymphedema may be the initial manifestation of lymphoma,

with lymphedema representing the sole clinical manifestation of

lymphoma in certain cases. While no specific molecular biomarkers

are universally established for the diagnosis of lymphedema,

advancements in imaging and bioimpedance technologies have provided

indirect markers for the assessment of lymphatic dysfunction

(29,30). For instance, bioimpedance

spectroscopy and the tissue dielectric constant are non-invasive

tools that quantify extracellular fluid volume and detect

subclinical lymphedema with high sensitivity (31). Additionally, serum biomarkers such

as β2-microglobulin and urinary immunoglobulins (e.g., Igκ/λ light

chains) have been observed in patients with malignancy-associated

lymphedema, although these are non-specific and often linked to

underlying conditions such as lymphoma (32). Emerging research also highlights the

role of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α) and

lymphangiogenic factors (such as VEGF-C/D) in lymphatic remodeling,

which may serve as potential molecular indicators in the future

(33). The current study presented

a series of lymphoma cases characterized by the presence of

lymphedema. The analysis of the present study, in conjunction with

previous studies, indicated that lymphedema could represent a

potential manifestation of lymphoma, which potentially resulted

from lymphatic or venous obstruction.

Previous studies have revealed a notable association

between lymphedema and lymphoma, with lymphomas being the most

prevalent neoplasms associated with immunodysregulation. It is

posited that abnormal lymphoid proliferation may be causally linked

to lymphatic stasis (11).

Insufficient lymphatic drainage can disrupt the normal trafficking

of lymphocytes and Langerhans cells, which are essential for the

maintenance of immunocompetence, which leads to an immunologically

susceptible state in the lymphedematous region and increases the

risks of infection and oncogenesis (34). Several theories have been proposed

to elucidate the underlying mechanisms involved in the

aforementioned process. Futrell and Myers (35) emphasized the role of the

immunological status in determining the response of animal hosts to

tumors implanted in the skin, regardless of the integrity of the

lymphatic system. Their findings revealed that, although tumor

solutions did not induce malignancy when injected into areas with

intact lymphatic vessels, malignant tumors developed when

injections occurred in regions with compromised lymphatics

(35). Furthermore, deficiencies in

the lymphatic drainage system may hinder the early detection of

tumor-specific antigens (36).

Chronic stasis can lead to alterations in the local lymphatic

protein composition, which are characterized by a decrease in the

α-2 globulin fraction and an increase in the albumin-globulin ratio

(37). This delay in protein

transport from the interstitial space to the lymphatic space may

modify the antigenic composition and/or regional immunological

competence of the tissue. The relationship between elevated

lymphocyte counts and lymphatic stasis remains complex and

context-dependent. While chronic lymphatic stasis can lead to

localized immune dysregulation, specific thresholds for lymphocyte

proliferation in lymphedema are not well-defined in the literature.

However, previous studies have suggested that persistent

CD4+ T-cell infiltration in lymphedematous tissues

contributes to chronic inflammation and fibrosis, which exacerbates

lymphatic dysfunction (38). For

instance, in cases of malignancy-related lymphedema,

tumor-associated lymphocytes may infiltrate obstructed lymphatic

pathways, although quantitative percentages are rarely reported.

Further research is warranted to establish standardized values that

associate lymphocyte counts with stasis severity. Additionally,

systemic immunodeficiency or external factors, such as potential

carcinogenic viral infections (e.g., HPV infection), may be

evaluated and utilized to further elucidate the etiology of tumors

(5,39).

In a study of 10 cases of lymphedema associated with

lymphoma, Hawkins et al (25) demonstrated that unilateral leg edema

was the sole presenting symptom in 7 cases. Similarly, Smith et

al (7) reported that among 35

cases of lymphedema attributed to neoplasms, all 8 lymphoma cases

presented with palpable inguinal lymph nodes, with 3 cases

presenting with edema as the initial manifestation of the

condition. Upon the diagnosis of lymphedema, clinicians should

maintain a heightened clinical suspicion of lymphoma as a potential

underlying cause.

In the present cohort of 11 patients, lymphedema

predominantly affected the lower extremities (9 out of 11

patients), with a mean age of 61.0±12.5 years and a median delay of

7 months between lymphedema onset and lymphoma diagnosis. The key

clinical manifestations of these patients included limb swelling,

weakness, weight loss, lymphadenopathy and pain. These findings

align with those of previous studies, such as that by Hawkins et

al (25), which reported

unilateral leg edema as the sole presenting symptom in 70% of

patients with lymphoma-associated lymphedema. Similarly, Smith

et al (7) noted that

lymphedema secondary to malignancy often manifests acutely and

asymmetrically, along with accompanying systemic symptoms such as

fatigue and weight loss. Notably, the present case report revealed

a greater proportion of lower extremity involvement (81.8%)

compared with upper limb involvement (9.1%), which is consistent

with a report by Tatnall and Mann (17), which described chronic limb

lymphedema as a predisposing factor for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The

present scenario contrasts with secondary lymphedema caused by

breast cancer surgery, where upper limb involvement is

predominant.

Lymphoma-induced lymphedema is frequently

misdiagnosed initially because of its nonspecific presentation. In

the present cohort, 66.7% of patients exhibited abnormal changes in

tumor markers (including alterations in CA125 and β2-microglobulin)

and 45.5% had anemia, which suggested systemic involvement.

Furthermore, imaging modalities (such as CT, MRI and

ultrasonography) achieved 100% detection rates for suspicious

lesions, which thereby underscores their diagnostic utility.

However, the case reported by González-Vela et al (11) was extremely prone to misdiagnosis:

an 89-year-old male presented with multiple cutaneous lesions on

his right limb, manifesting as chronic lymphedema. Upon skin

examination, multiple purplish red, firm, slightly infiltrated

nodules were found on his legs and instep of his foot. Biopsy of

one of the nodules revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the

leg. CT scans of the patient's chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not

show signs of lymph node enlargement. Bone marrow aspiration and

biopsy results were normal. The patient underwent local

radiotherapy and achieved significant clinical remission. The

differentiation of lymphoma-associated lymphedema from lymphedema

of other etiologies requires a comprehensive evaluation of the

clinical presentation, imaging findings, biomarkers, pathological

mechanisms and therapeutic responses. In our research, we found

that lymphoma-induced lymphedema typically manifests with

insidious, asymmetric lower extremity swelling (81.8% of cases)

occurring over weeks to months, which is often accompanied by

systemic symptoms such as weight loss, fever or lymphadenopathy. In

addition, patients may exhibit acute-onset skin pigmentation

changes or localized neuropathic symptoms, which represent features

that are distinct from acute unilateral swelling with

tenderness/cyanosis (which occurs in venous edema) or bilateral

symmetry (which occurs in systemic causes such as heart failure).

Additionally, imaging serves a key role. Specifically, the use of

CT/MRI in lymphoma can reveal tumor-obstructed lymphatic pathways

or malignant lymphadenopathy, whereas the use of positron emission

tomography-CT can identify hypermetabolic lesions, which contrasts

the venous duplex findings of thrombosis observed in venous edema

or the hypoalbuminemia-driven fluid shifts observed with systemic

causes. Furthermore, elevated serum biomarkers (such as

β2-microglobulin and CA125) are observed in 66.7% of patients with

lymphoma, which further distinguishes lymphoma from hypoproteinemia

(low albumin levels) or a venous etiology (elevated D-dimer

levels). Pathologically, lymphoma disrupts lymphatic integrity via

direct tumor infiltration or cytokine-mediated dysfunction, which

thus creates an immunocompromised microenvironment, whereas primary

lymphedema stems from congenital lymphatic malformations.

Therapeutically, lymphoma-associated edema responds poorly to

conventional compression therapy and requires tumor-directed

interventions (such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy), unlike venous

edema (which is anticoagulation-responsive) or primary lymphedema

(which is partially improved by using decongestive therapy).

Notably, lymphoma rarely induces systemic edema, which is a feature

that is absent in postoperative or primary lymphedema and thereby

underscores the importance of screening for malignancy in atypical

presentations (40,41).

In conclusion, based on the retrospective analysis

of 11 patients with lymphoma presenting with lymphedema at our

institution, this case series establishes that lymphedema

frequently serves as an early and occasionally isolated

manifestation of lymphoma, particularly affecting the lower

extremities with asymmetric progression. Key findings include a

median diagnostic delay of 7 months, frequent systemic biomarkers

and universal detection of malignant lesions by cross-sectional

imaging (CT/MRI/ultrasonography). Critically, lymphoma-induced

lymphedema demonstrates poor response to conventional decongestive

therapy but shows significant improvement with tumor-directed

interventions (chemotherapy/radiotherapy). These observations

underscore that unilateral lower limb edema-particularly when

acute, therapy-refractory or accompanied by unexplained serologic

abnormalities-warrants rigorous screening for occult lymphoma.

Integrating targeted imaging and biomarker assessment into the

diagnostic workflow is essential to reduce delays in lymphoma

diagnosis and initiate timely oncologic management, thereby

altering the natural history of this potentially misdiagnosed

condition.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding for the present case report was provided by the Talent

Development Program of Beijing Shijitan Hospital Affiliated to

Capital Medical University during the 14th Five-Year Plan (grant

no. 2023LJRCSWB); the Youth Fund of Beijing Shijitan Hospital

Affiliated to Capital Medical University (grant no. 2022-q16); the

Key Project of Beijing Shijitan Hospital Affiliated to Capital

Medical University (grant no. 2024-C04); and the Haidian District

Health Development Research and Cultivation Plan of Beijing (grant

no. HP2025-04-506002).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KH, RW, WS and YS conceptualized and designed the

present case report. WS, RW and YS provided administrative support.

KH, XL, JR, CY, LZ, BL, RW, YS and WS provided the study materials

and recruited patients. KH, XL, JR, CY, LZ, BL, RW and YS collected

and assembled the data. KH, XL, JR, RW and YS performed the data

analysis and interpreted the data. KH and YS confirmed the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors wrote the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Ethics Committee of Beijing Shijitan Hospital,

Capital Medical University, approved the present study [approval

no. sjtkyll-lx-2022(058)], which adhered to the ethical guidelines

set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

participating patients for the publication of the anonymized

medical images (including radiological data) and associated case

details.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Davis MJ, Zawieja SD and King PD:

Transport and immune functions of the lymphatic system. Annu Rev

Physiol. 87:151–172. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rockson SG and Rivera KK: Estimating the

population burden of lymphedema. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1131:147–154.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shaitelman SF, Cromwell KD, Rasmussen JC,

Stout NL, Armer JM, Lasinski BB and Cormier JN: Recent progress in

the treatment and prevention of cancer-related lymphedema. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:55–81. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Grada AA and Phillips TJ: Lymphedema:

Diagnostic workup and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 77:995–1006.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV and Ruocco

E: The immunocompromised district: A unifying concept for

lymphooedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J

Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 23:1364–1373. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ruocco V, Schwartz RA and Ruocco E:

Lymphedema: An immunologically vulnerable site for development of

neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 47:124–127. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Smith RD, Spittell JA and Schirger A:

Secondary lymphedema of the leg: Its characteristics and diagnostic

implications. JAMA. 185:80–82. 1963. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sun L, Sun Y, Xin W, He J, Hu Y, Zhang H,

Yu J and Zhang JA: A case of CD5-positive primary cutaneous diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma, leg type secondary to chronic lymphedema. Am

J Dermatopathol. 44:179–182. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vijaya B, Narahari SR, Shruthi MK and

Aggithaaya G: A rare case of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma, leg type in a patient with chronic lymphedema of the leg.

Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 62:470–472. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sanna P, Bertoni F, Roggero E, Quattropani

C, Rusca T, Pedrinis E, Monotti R, Mombelli G, Cavalli F and Zucca

E: Angiotropic (intravascular) large cell lymphoma: case report and

short discussion of the literature. Tumori. 83:772–775. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

González-Vela MC, González-López MA,

Val-Bernal JF and Fernández-Llaca H: Cutaneous diffuse large B cell

lymphoma of the leg associated with chronic lymphedema. Int J

Dermatol. 47:174–177. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hills RJ and Ive FA: Cutaneous secondary

follicular centre cell lymphoma in association with lymphoedema

praecox. Br J Dermatol. 129:186–189. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Dargent JL, Lespagnard L, Feoli F,

Debusscher L, Greuse M and Bron D: De novo CD5-positive diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma of the skin arising in chronic limb

lymphedema. Leuk Lymphoma. 46:775–780. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shabbir A, Kojadinovic A, Gidfar S and

Mundi PS: Extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of bone and soft

tissue presenting with marked lymphedema and hypercalcemia. Cureus.

14:e220252022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Massini G, Hohaus S, D'Alò F, Bozzoli V,

Vannata B, Larocca LM and Teofili L: Mantle cell lymphoma relapsing

at the lymphedematous arm. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

5:e20130162013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wan N and Jiao Y: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

mimics retroperitoneal fibrosis. BMJ Case Rep.

2013:bcr20130104332013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tatnall FM and Mann BS: Non-Hodgkin's

lymphoma of the skin associated with chronic limb lymphoedema. Br J

Dermatol. 113:751–756. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Barki A, Dua-Boateng P, Mhanna T, Houmaidi

AE, Souarji A and Allat Oufkir A: Penoscrotal lymphedema revealing

a lymphoma: A case report. Urol Case Rep. 33:1013082020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Paydaş S, Sahin B, Yavuz S and Gönlüşen G:

Postmastectomy malignant lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 36:417–420. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fan P, Nong L, Sun J, Liu X, Kadin ME, Li

T, Tu P and Wang Y: Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell

lymphoma with intralymphatic involvement associated with chronic

lymphedema. J Cutan Pathol. 44:616–619. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Torres-Paoli D and Sánchez JL: Primary

cutaneous B-cell lymphoma of the leg in a chronic lymphedematous

extremity. Am J Dermatopathol. 22:257–260. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Waxman M, Fatteh S, Elias JM and Vuletin

JC: Malignant lymphoma of skin associated with postmastectomy

lymphedema. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 108:206–208. 1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

d'Amore ES, Wick MR, Geisinger KR and

Frizzera G: Primary malignant lymphoma arising in postmastectomy

lymphedema. Another facet of the Stewart-Treves syndrome. Am J Surg

Pathol. 14:456–463. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Binjawhar A, El-Tholoth HS, Alzayed EM and

Althobity A: Successful surgical treatment of giant scrotal

lymphedema associated with Hodgkin's lymphoma: A rare case report.

Urol Case Rep. 37:1017082021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hawkins KA, Amorosi EL and Silber R:

Unilateral leg edema. A symptom of lymphoma. JAMA. 244:2640–2641.

1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Elgendy IY and Lo MC: Unilateral lower

extremity swelling as a rare presentation of non-Hodgkin's

lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2014:bcr20132024242014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Shi F, Zhou Q, Gao Y, Cui XQ and Chang H:

Primary splenic B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features

intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical

Hodgkin lymphoma: A case report. Oncol Lett. 12:1925–1928. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sehn LH and Salles G: Diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 384:842–858. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mozas P, Sorigué M and López-Guillermo A:

Follicular lymphoma: An update on diagnosis, prognosis, and

management. Med Clin (Barc). 157:440–448. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Merryman R, Mehtap Ö and LaCasce A:

Advancements in the management of follicular lymphoma: A

comprehensive review. Turk J Haematol. 41:69–82. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lahtinen T, Seppälä J, Viren T and

Johansson K: Experimental and analytical comparisons of tissue

dielectric constant (TDC) and bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) in

assessment of early arm lymphedema in breast cancer patients after

axillary surgery and radiotherapy. Lymphat Res Biol. 13:176–185.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kaseb H, Wang Z and Cook JR:

Ultrasensitive RNA in situ hybridization for kappa and lambda light

chains assists in the differential diagnosis of nodular

lymphocyte-predominant hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol.

46:1078–1083. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ge Q, Zhao L, Liu C, Ren X, Yu YH, Pan C

and Hu Z: LCZ696, an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor,

improves cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and cardiac lymphatic

remodeling in transverse aortic constriction model mice. Biomed Res

Int. 2020:72568622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Witte CL and Witte MH: Disorders of lymph

flow. Acad Radiol. 2:324–334. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Futrell JW and Myers GH Jr: Regional

lymphatics and cancer immunity. Ann Surg. 177:1–7. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Parthiban R, Kaler AK, Shariff S and

Sangeeta M: Squamous cell carcinoma arising from congenital

lymphedema. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. Sep 19–2013.(Epub ahead of

print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Rockson SG: Advances in lymphedema. Circ

Res. 128:2003–2016. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li CY, Kataru RP and Mehrara BJ:

Histopathologic features of lymphedema: A molecular review. Int J

Mol Sci. 21:25462020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Gomes CA, Magalhães CB, Soares C Jr and

Peixoto Rde O: Squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic

lymphedema: Case report and review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med

J. 128:42–44. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cheng G and Zhang J: Imaging features (CT,

MRI, MRS, and PET/CT) of primary central nervous system lymphoma in

immunocompetent patients. Neurol Sci. 40:535–542. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Winkelmann M, Kassube M, Rübenthaler J,

Sheikh GT and Kunz WG: Primary imaging diagnostics of lymphomas.

Radiologie (Heidelb). 65:500–507. 2025.(In German). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|