Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a hematological

malignancy characterized by the aberrant proliferation of

hematopoietic stem cells and is the most prevalent form of acute

leukemia in adults, accounting for ~80% of cases in this group

(1,2). Despite the continuous development of

medical technology, the 5-year survival rate of patients with AML

is 32% (with the rate as high as 50% in younger patients and lower

than 10% in those over 60 years old) and the prognosis remains poor

(3–5). Although traditional cytotoxic

chemotherapy has been the foundation of AML treatment for the past

50 years, researchers are investigating therapeutic approaches

aimed at enhancing patient survival (6,7).

Transcription is a complex biological event

involving the interaction of transcription factors, RNA polymerase

II and transcriptional cofactors with DNA regulatory elements. This

process is key for maintaining essential cell functions such as

cell proliferation, differentiation, and metabolic homeostasis

(8). It converts DNA sequences into

translatable mRNA, which regulates protein synthesis. Organisms

achieve precise gene expression through a sophisticated

transcriptional regulatory network that ensures internal

environmental stability and regulates normal cell development

(9–11). When transcriptional dysregulation

occurs, it can lead to abnormal cell proliferation and

differentiation, which ultimately results in tumors (12). Consequently, small-molecule targeted

therapies aimed at key proteins in transcriptional regulation have

become a focal point of current research (13). Menin protein inhibitors have

emerged, with several preclinical studies confirming their notable

potential as chromatin regulators (14–16).

The menin protein, encoded by the multiple endocrine

neoplasia type 1 gene, functions primarily as a scaffolding protein

that modulates gene transcription via interactions with various

gene regulators, such as histone methyltransferases and

transcription factors including JunD and SMAD (15,17,18).

In AML, menin serves a key role in epigenetic regulation by

interacting with genes such as lysine methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A)

and mutant nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1), thereby facilitating the

progression of AML (19,20). Inhibitors of the menin protein may

reverse aberrant transcription associated with tumors and restore

normal gene expression and cellular function by targeting this

essential epigenetic regulator (21). The present review aimed to provide a

comprehensive evaluation of the role of menin protein, assess the

data supporting its mechanisms in KMT2A/NPM1 mutations and discuss

the pharmacological characteristics and clinical challenges

associated with current inhibitors, such as functional disparities

of menin in various cellular contexts and optimization pathways for

combinatorial therapeutic strategies.

AML is categorized into subtypes based on genetic

and transcriptomic characteristics, one of which is defined by the

homeobox (HOX) gene upregulation and primarily includes NPM1-mutant

(NPM1-mut) and MLL-rearranged leukemia (22). MLL proteins (MLL1 and MLL2) belong

to the histone H3 position 4 lysine (H3K4) methyltransferase

family, which is essential for the maintenance of high HOX gene

expression, and activate myeloid ecotropic viral integration site 1

(MEIS1) through direct epigenetic regulation (16). Notably, MLL fusion proteins contain

specific Su(var)3-9, Enhancer-of-zeste, Trithorax) structural

domains, whereas the crystal structure of menin proteins exhibits a

rectangular conformation, which allows for the formation of deep

binding pockets that bind specifically to the N-terminal fragment

of MLL fusion proteins (23,24).

This interaction designates menin protein as an oncogenic cofactor

that facilitates histone H3 lysine trimethylation at position 4

(H3K4me3) via its engagement with MLL, subsequently enhancing

HOX/MEIS1 gene expression and precipitating leukemia (25). Utilizing a structure-based drug

design approach targeting the menin-MLL interaction interface,

Krivtsov et al (15)

developed a highly selective small molecule inhibitor, VTP50469,

which displaces menin from the fusion protein and prevents the

recruitment of MLL to target genes. Both cell and animal studies

(immunodeficient NSG mice xenotransplanted with human KMT2A-r

leukemia cells) have demonstrated notable anti-leukemic efficacy

(15,26). While preclinical data indicate that

the small molecule inhibitors exhibit potential anti-leukemic

efficacy, the extensive menin-MLL binding interface reveals that

the crystal structure of VTP50469 occupies a subregion of the

menin-MLL interface (15,27). This indicates the necessity for

potentially higher inhibitor concentrations to achieve complete

menin-MLL disruption, consistent with the typical dose-response

association of partial protein-protein interaction inhibitors

(28,29). This technical barrier may represent

a notable impediment in the translation of menin-MLL-targeted

therapies from laboratory research to clinical application.

The sirtuin family comprises seven highly conserved

members (SIRT1-SIRT7) that share evolutionary conservation, all of

which possess highly conserved catalytic structural domains,

differing markedly only at their N- and C-terminus (30,31).

This structure enables each member to exhibit

NAD+-dependent deacetylase and ADP-ribosyltransferase

activity (31). As components of

histone deacetylases, SIRTs serve a key role in cell proliferation,

survival, maintenance of genomic stability and metabolic regulation

by modulating gene expression and chromatin dynamics. A direct

interaction between the menin protein and SIRT1 has been identified

(30). Menin binds directly to the

deacetylase structural domain of SIRT1 through its C-terminal

domain, which forms a functional complex that regulates epigenetic

processes. In mouse hepatocytes, SIRT1 modulates CD36 gene

expression and intracellular triglyceride accumulation via histone

deacetylation, a process that is contingent upon the involvement of

the menin protein (32).

Furthermore, in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, menin enhances

NF-κB (p65) deacetylation by recruiting SIRT1, which underscores

its key role in the SIRT regulatory network (33). Numerous studies have demonstrated

that SIRT1 impacts apoptosis and inflammatory activation by

modulating the NF-κB pathway (34–36).

For example, in murine models, upregulation of SIRT1 promotes B

lymphocyte proliferation, inhibits apoptosis and advances

inflammatory responses by suppressing the NF-κB pathway (37,38).

Therefore, it is hypothesized that in acute leukemia, the

menin-SIRT interaction may also influence apoptosis and

inflammatory activation via the NF-κB pathway, potentially

inhibiting or promoting acute leukemia (39).

The human genome encodes a total of 11 PRMTs, which

regulate cell signaling networks by modifying arginine residues in

both histone and non-histone proteins (40). As important epigenetic regulators in

eukaryotes, all members of the PRMT family contain highly conserved

S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase structural

domains that facilitate the transfer of methyl groups from SAM to

the nitrogen atom of substrate arginine residues (41,42).

Menin protein can recruit PRMT5 to the growth arrest-specific

protein 1 (GAS1) gene locus, inhibiting GAS1 gene expression by

promoting the symmetric dimethylation of histone H4 at position 3

(H4R3me2) (43). However, in MLL,

the interaction between menin protein and PRMT5 leads to decreased

levels of H4R3me2 and fails to effectively inhibit GAS1 expression

(44,45). This suggests that the regulation of

PRMT by menin protein may be context-dependent (43). In MEN1 tumor syndrome and

mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL), the regulation of GAS1 by the

menin-PRMT5 complex exhibits opposite outcomes, suggesting an

oncogenic isoform of the menin-PRMT5 complex that reverses

epigenetic manifestations by altering the conformation of the

complex (43,44).

SUV39H1 is a histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferase

(H3K9). Menin protein enhances trimethylation of H3K9 in the

promoter regions of target genes by interacting with SUV39H1,

thereby silencing transcription of associated genes (24,46).

In a previous study on IL-6 gene regulation, Song et al

(47) detected the enrichment of

menin protein and SUV39H1 around the IL-6 gene using chromatin

immunoprecipitation (ChIP). The aforementioned study reported that

menin protein and SUV39H1 are specifically recruited to the

auxiliary region of the IL-6 promoter and the recruitment of

SUV39H1 decreases with the depletion of menin protein, which

suggests menin protein may serve a key role in the regulation of

SUV39H1. Further analysis indicated that menin protein and SUV39H1

may regulate IL-6 gene expression at the protein level through H3K9

methylation (47). Numerous

preclinical and clinical studies have confirmed that IL-6 serves a

notable role in the development of acute leukemia (48–50).

Anti-IL-6 antibodies, such as cetuximab, have potential therapeutic

value in the treatment of various malignancies, including acute

leukemia, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy regimens

(51). However, the pathogenesis of

leukemia involves a complex regulatory network of multiple

signaling pathways - such as JAK/STAT, NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin -

which limits the therapeutic efficacy of targeting IL-6 alone

(52–54). Following blocking IL-6 signaling,

leukemia cells sustain their survival and proliferative capacity by

activating alternative pathways (for example, Janus kinase/STAT),

which markedly reduces the clinical benefit of single-agent

therapy. These direct epigenetic regulatory interactions mediated

by menin are summarized in Table

I.

SMAD proteins are key downstream effector molecules

in the TGF-β signaling pathway and serve a direct role in TGF-β

signaling and gene transcriptional regulation (58). As transcriptional regulators, menin

protein binds SMAD proteins, thereby indirectly influencing the

activity of the TGF-β signaling pathway and regulating the

transcription of target genes. In pituitary secretory tumor cell

lines, menin protein markedly enhances the binding specificity of

SMAD3 to DNA sequences via interaction with SMAD3 (59,60).

More importantly, during osteoblast differentiation and maturation,

menin protein forms complexes with SMAD1, SMAD5 and the key

regulator of osteogenesis Runt-related transcription factor 2 to

promote the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into

osteoblasts (59,61). While the interaction of menin

protein with SMAD1, SMAD3 and SMAD5 has been demonstrated (59), the specific molecular mechanisms

underlying their synergistic activation of transcription warrant

further investigation.

As a key proto-oncogene, the dysregulated expression

of Myc is closely associated with >50% of malignant

tumorigenesis (62). Myc serves

primarily as a transcription factor through the classical

enhancer-box (E-box) region (63).

Wu et al (64) demonstrated

that Myc forms a regulatory complex with positive transcription

elongation factor b (P-TEEb) within the E-box region to activate

transcription, with the menin protein being a key factor in this

process. Menin regulates Myc-mediated transcriptional activity by

influencing the transcriptional elongation regulator P-TEEb. In the

KMT2A rearrangement (KMT2A-r) AML model, the expression of Myc and

its characteristic genes is markedly suppressed in leukemia cells

following treatment with a menin inhibitor (65). Zhou et al (65) found a notable positive correlation

between menin protein levels and Myc expression, which suggests Myc

may serve as a common target of menin protein. Based on these

findings, co-targeting menin protein and Myc may represent a novel

therapeutic strategy for leukemia treatment in future.

The FOX family is an evolutionarily conserved group

of transcription factors, all of which possess the distinctive

forkhead DNA-binding structural domain and are key for cell

proliferation and differentiation (66). Previous studies have indicated that

menin protein engages with several members of the FOX family, such

as FOXG1, FOXA1 and FOXO1 (67–69).

In FOXG1-associated encephalopathy, menin protein influences

α-thalassemia X-linked mental retardation protein-mediated FOXG1

transcription via modulation of the FOXG1 transcripts (67). Bonnavion et al (70) established that menin protein

interacts with FOXA2, which influences its trans-auto reactivation

ability and serves a role in the control of FOXA2 expression in

adult pancreatic α-cells.

The inaugural member of the Wnt family was

identified in 1982 and research has consistently validated the

essential function of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in

embryonic development and tissue regeneration (71–73),

Dysregulation of this system results in numerous illnesses, such as

colorectal and gastric cancer (74–77).

Menin protein serves as a reciprocal partner of β-catenin proteins,

the principal effector molecules of this signaling pathway, and can

facilitate their nuclear translocation. ChIP and chromosome

conformation capture (3C) studies demonstrated that the menin

protein augments the association of β-catenin proteins with the Myc

promoter (78–80). The mechanism of action of menin

protein inhibitors in the treatment of AML may partially arise from

their suppression of the Wnt/β-catenin protein signaling pathway

(81–83).

Nuclear receptors are a class of receptor proteins

located in the nucleus, which include the androgen receptor (AR),

estrogen, thyroid hormone, glucocorticoid, retinoid X, peroxisome

proliferator-activated, liver X and retinoic acid receptors

(84). These receptors not only

serve as biosensors to regulate key cellular activities such as

proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis but also directly

bind to DNA to exert transcriptional regulation (85,86).

The interactions between nuclear receptors and tumor growth have

attracted notable research regarding their role in tumor

progression (87–89). Luo et al (90) identified that the menin protein

exhibits distinct pro-oncogenic actions in androgen

receptor-dependent prostate cancer cells by modulating AR

transcription and its target genes. Based on the presence of

nuclear receptor interaction sites in the amino acid sequence of

the menin protein, menin serves as an important coactivator of

nuclear receptor-mediated transcription (68,90).

The NF-κB family comprises five members: Rel or

c-Rel, RelA or p65, RelB, NF-κB1 or p50 and NF-κB2 or p52. Each

member exists in dimeric form and possesses a Rel homology domain

(91). The pro-carcinogenic role of

NF-κB is prevalent in hepatocellular carcinoma (92). Previous studies have demonstrated

that menin protein engages with NF-κB and suppresses p65-mediated

transcriptional activation via the recruitment of SIRT1 (33,93).

Another previous study revealed that the degree of menin-NF-κB

interaction changes the production of cell cycle protein D1, a

downstream signaling molecule of NF-κB that governs the G1/S phase

transition and affects cell proliferation (55). Irregularities in this mechanism may

result in tumorigenesis.

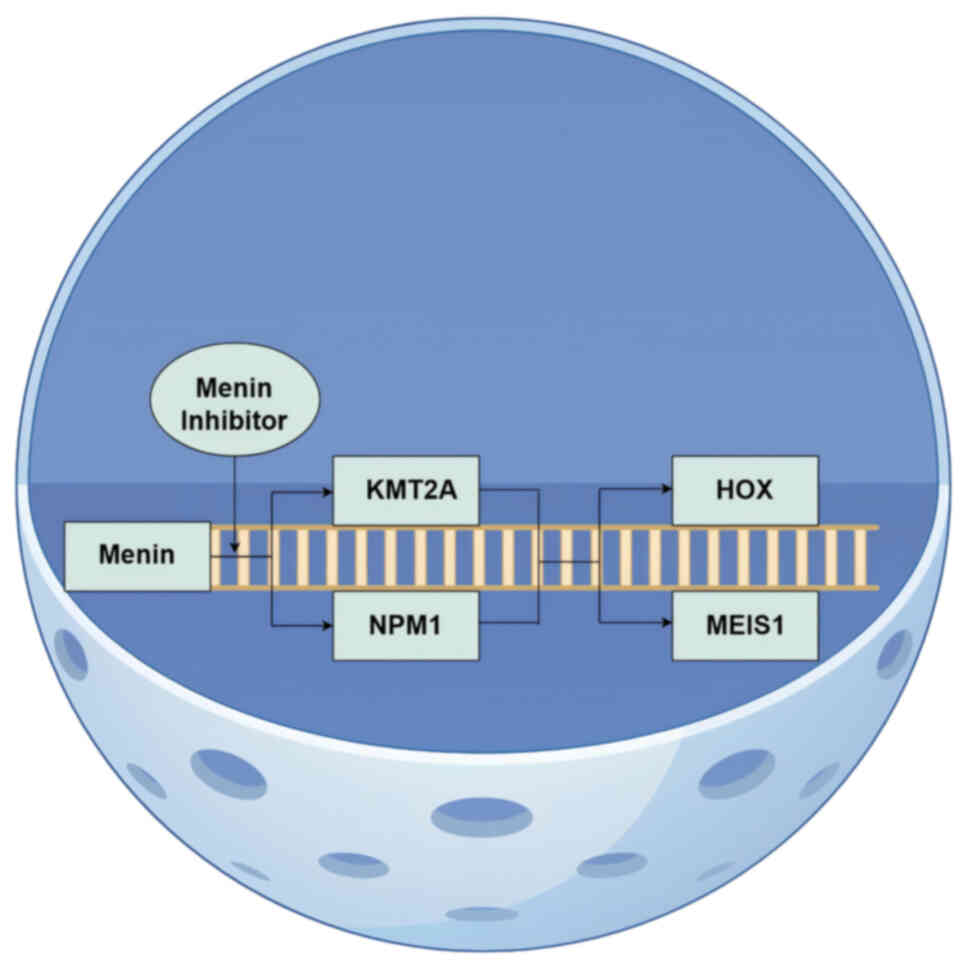

The menin-MLL complex activates the expression of

the HOX/MEIS1 gene cluster by mediating aberrant H3K4me3, a

well-established axis of epigenetic regulation implicated in

KMT2A-r and NPM1-mut leukemia (Fig.

1 (17,94). This mechanism was first elucidated

by Yokoyama et al (94), who

demonstrated that blocking the interaction between menin and the

methyltransferase KMT2A markedly decreases leukemia incidence in

mice (95). Further research has

confirmed the key role of menin protein in NPM1-mut leukemia

(96). Specifically, menin protein

contributes to KMT2A-r leukemia by binding to fusion proteins and

to NPM1-mut leukemias via aberrant nucleoplasmic transport pathways

(97). The role of the menin

protein in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia and NPM1-mutant leukemia cause

the dysregulated expression of the HOX and MEIS1 genes (98,99).

Menin inhibitors effectively suppress the abnormal proliferation

and differentiation of leukemia cells by specifically disrupting

the interaction between menin and KMT2A or NPM1, while

simultaneously downregulating the expression of HOX and MEIS1,

thereby demonstrating notable therapeutic potential (21).

Patients with acute leukemia characterized by

KMT2A-r, previously referred to as MLL, exhibit a long-term

survival rate <60% and poor prognosis across all age

demographics (100,101). This leukemia variant exhibits a

high prevalence among infants and children, accounting for >70%

of new acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) diagnoses in infants, is

marked by notable aggressiveness, frequent relapse, substantial

medication resistance and presents considerable challenges for

therapeutic management as a high-risk genetic subtype (101).

KMT2A-r may lead to aberrant expression of the HOX

gene and its DNA-binding cofactor MEIS1, which may inhibit

hematological development and precipitate leukemia (21,102).

Although no specific medications have been approved for KMT2A-r

leukemia, preclinical studies have identified the chromatin

regulatory protein menin as a promising therapeutic target

(14,103,104). In KMT2A-driven leukemia, all KMT2A

fusion proteins contain menin-binding sequences, with menin protein

serving as a key cofactor that facilitates the interaction between

the KMT2A protein complex and the HOX gene promoter. In a study

using the KMT2A-mut leukemia model (105), it was demonstrated that the

inhibition of menin protein markedly reduces the transcript levels

of HOX and MEIS1, thereby reversing the leukemogenesis process.

Through the examination of gene expression in

pediatric and adult patients with primary AML, researchers

discovered that NPM1-mut leukemia exhibits notable similarities to

the KMT2A-r subtype and NPM1 is associated with the HOX/MEIS1 gene

cluster (106). NPM1-mut is among

the most prevalent genetic alterations in AML, affecting ~30% of

the total patient population (107). These mutations, primarily located

in the terminal exons of the NPM1 gene, enhance nuclear export

signaling activity and impair nucleolus localization signaling,

which results in the dysregulated expression of the HOXA/B and

MEIS1 genes (108). NPM1 may serve

as a transcriptional amplifier of gene expression, potentially

constituting a notable factor in the development of AML (109). Dillon et al (110) identified microscopic residual

lesions in patients with AML through pre-transplantation DNA

sequencing of hematopoietic stem cells, which revealed that

patients with NPM1-mut AML experience a significantly higher

recurrence rate and shorter survival compared with those without

NPM1-mut.

The persistence of NPM1-mut AML in an

undifferentiated state is attributed to the HOX-associated pathway,

which underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting this

pathway. Menin protein serves as a cofactor to promote H3K4me3

through interactions with MLL, thereby modulating the expression of

HOX and MEIS1 genes. This mechanism highlights the feasibility of

targeting menin protein for therapeutic interventions (96). In vivo experiments have

demonstrated that inhibitors of menin protein exhibit notable

anti-leukemic activity in NPM1-mut leukemia (20,21,111).

Previous studies conducted in NPM1-mutant leukemia models have

indicated that treatment with the menin inhibitor VTP50469, a

precursor drug to revumenib, leads to downregulation of oncogenic

cofactors such as MEIS1 and a marked reduction in the self-renewal

capacity of leukemic stem cells (15,104).

Understanding of the menin formation mechanism in

leukemia, alongside advancements in high-throughput screening

techniques and structural biology, facilitate creation of highly

selective small chemical inhibitors (112). Based on the efficacy of menin

inhibitors in KMT2A-r and NPM1-mut leukemia, a growing array of

menin inhibitors (such as revumenib and ziftomenib) exhibiting

enhanced pharmacological efficacy against these AML subtypes has

recently been introduced into clinical practice (21,113,114).

A total of seven menin inhibitors are undergoing

different phases of clinical development for acute myeloid

leukemia, with numerous candidates in development (Table II). The leading candidate is

revumenib, which demonstrated a promising safety and effectiveness

profile in a phase I open-label, dose-escalation and extension

study (AUGMENT-101) assessing the menin inhibitor revumenib for

KMT2A-r leukemia treatment (21,113).

The occurrence of grade ≤3 treatment-related side events was

minimal in treated patients, with asymptomatic QT interval

prolongation being the sole dose-limiting effect. Revumenib

achieved an overall remission rate of ≤53% and a complete remission

rate of ≤30% with partial hematological recovery (98,113).

In the subsequent phase II trial (AUGMENT-101), a total of 94

patients with KMT2A-r acute leukemia (comprising 78 patients with

AML, 14 with ALL and two with an indeterminate subtype) received

menin inhibitors, which achieved an overall remission rate of 63.2%

(of which, 68.2% exhibited no measurable residual disease;

unpublished data). In 57 patients with assessable efficacy, the

combined complete response and complete response with incomplete

hematological recovery rate reached 22.8% (113). Grade ≥3 adverse events included

neutropenia (37.2%), differentiation syndrome (16%) and QT interval

prolongation (13.8%). Most of these events were controllable and

transitory and menin inhibitors had a predictable safety

profile.

The combination therapy of menin inhibitors with

other targeted leukemia medications has potential due to the

promising efficacy and safety profile of menin inhibitor

monotherapy in the treatment of acute leukemia. Miao et al

(115) administered a menin

inhibitor and kinase inhibitor to NUP98-r leukemia samples, which

demonstrated that the combination therapy outperformed monotherapy,

with a combination index between 0.12 and 0.65, as determined by

the Chou-Talalay method, which indicated notable synergistic

effects. The combinatorial therapy induced a more pronounced

decrease in both the quantity and size of leukemic blasts in

NUP98-r leukemia specimens and was more effective in promoting cell

proliferation arrest and differentiation. Furthermore, the

combination of Brahma-related gene 1/Brahma inhibitors with menin

inhibitors for acute leukemia treatment has demonstrated notable

preclinical efficacy, resulting in a more substantial reduction in

leukemia burden and extended survival duration in mice compared

with monotherapy (116). A

clinical trial is currently examining menin inhibitors in

conjunction with azacitidine/vincristine for the treatment of acute

leukemia, specifically evaluating JNJ-75276617 with AML-targeted

treatments (trial no. NCT05453903) (117). The combined regimen inhibits the

immune evasion of acute leukemia cells following monotherapy and

diminishes relapse in treatment-resistant leukemia (117).

Common adverse effects of menin inhibitors include

gastrointestinal reactions, QT interval prolongation, cytopenia and

differentiation syndromes, however, these adverse effects are

within manageable limits and menin inhibitors are generally safe

(113,118). Furthermore, menin inhibitors are

not associated with notable off-target toxicity, which has enabled

the clinical scale-up of menin inhibitors and their emergence as a

potential option for long-term therapy (112). However, recent data have also

demonstrated that certain patients have menin mutations that

prevent binding of the inhibitor and thus mediate clinical

resistance, which leads to clinical relapse; therefore, resistance

to menin inhibitors remains a challenge (21,119).

Although menin inhibitors have demonstrated

significant efficacy in KMT2A-r and NPM1-mut leukemia, their

clinical application faces key challenges such as drug resistance

and optimization of combination strategies (21,98).

Future research should focus on overcoming resistance mediated by

menin protein mutations, including the development of allosteric

inhibitors and combination with epigenetic regulatory drugs to

block compensatory pathways. In terms of combination therapy, it is

necessary to optimize combination regimens with other drugs based

on synergy indices (such as the Chou-Talalay model) and explore the

potential advantages of sequential therapy. Furthermore, the

indication scope of menin inhibitors should be expanded to include

other subtypes dependent on the HOX/MEIS1 pathway, such as NUP98-r

leukemia and predictive biomarkers based on HOX gene expression

profiles or menin-MLL complex activity should be developed to

screen beneficiary populations. From a technical perspective,

structural biology and artificial intelligence-assisted design

should be leveraged to develop high-affinity inhibitors and

targeted delivery systems should be developed to enhance efficacy

and safety. In-depth studies of the menin protein regulatory

network may reveal its functional heterogeneity in different cell

environments and provide a theoretical basis for dual-targeting

strategies (such as menin-Myc co-inhibition). With the advancement

of multidisciplinary collaboration, menin inhibitors may become a

key therapy for specific leukemia subtypes and provide novel

directions for epigenetically targeted therapy.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 81600129), Zhejiang Provincial

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. LY21H080001 and

BY22H205675), the Medical and Health Research Project of Zhejiang

Province (grant nos. WKJ-ZJ-2444 and 2022KY944) and Zhejiang

Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology

Project (grant no. 2022ZB276).

Not applicable.

HZ conceived, designed and supervised the study and

edited the manuscript. JB wrote the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable. Both authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Pollyea DA, Bixby D, Perl A, Bhatt VR,

Altman JK, Appelbaum FR, de Lima M, Fathi AT, Foran JM, Gojo I, et

al: NCCN guidelines insights: Acute myeloid leukemia, version

2.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 19:16–27. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

De Kouchkovsky I and Abdul-Hay M: Acute

myeloid leukemia: A comprehensive review and 2016 update. Blood

Cancer J. 6:e4412016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shimony S, Stahl M and Stone RM: Acute

myeloid leukemia: 2025 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification,

and management. Am J Hematol. 100:860–891. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sasaki K, Ravandi F, Kadia TM, DiNardo CD,

Short NJ, Borthakur G, Jabbour E and Kantarjian HM: De novo acute

myeloid leukemia: A population-based study of outcome in the United

States based on the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results

(SEER) database, 1980 to 2017. Cancer. 127:2049–2061. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fruchtman H, Avigan ZM, Waksal JA, Brennan

N and Mascarenhas JO: Management of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2

mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 38:927–935. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Short NJ, Konopleva M, Kadia TM, Borthakur

G, Ravandi F, DiNardo CD and Daver N: Advances in the treatment of

acute myeloid leukemia: New drugs and new challenges. Cancer

Discov. 10:506–525. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Carter JL, Hege K, Yang J, Kalpage HA, Su

Y, Edwards H, Hüttemann M, Taub JW and Ge Y: Targeting multiple

signaling pathways: The new approach to acute myeloid leukemia

therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5:2882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pei H, Guo W, Peng Y, Xiong H and Chen Y:

Targeting key proteins involved in transcriptional regulation for

cancer therapy: Current strategies and future prospective. Med Res

Rev. 42:1607–1660. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Milano L, Gautam A and Caldecott KW: DNA

damage and transcription stress. Mol Cell. 84:70–79. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Morgan MP, Finnegan E and Das S: The role

of transcription factors in the acquisition of the four latest

proposed hallmarks of cancer and corresponding enabling

characteristics. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:1203–1215. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Vervoort SJ, Devlin JR, Kwiatkowski N,

Teng M, Gray NS and Johnstone RW: Targeting transcription cycles in

cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 22:5–24. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Layden HM, Johnson AE and Hiebert SW:

Chemical-genetics refines transcription factor regulatory circuits.

Trends Cancer. 10:65–75. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kathman SG, Koo SJ, Lindsey GL, Her HL,

Blue SM, Li H, Jaensch S, Remsberg JR, Ahn K, Yeo GW, et al:

Remodeling oncogenic transcriptomes by small molecules targeting

NONO. Nat Chem Biol. 19:825–836. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Appel LM, Benedum J, Engl M, Platzer S,

Schleiffer A, Strobl X and Slade D: SPOC domain proteins in health

and disease. Genes Dev. 37:140–170. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Krivtsov AV, Evans K, Gadrey JY, Eschle

BK, Hatton C, Uckelmann HJ, Ross KN, Perner F, Olsen SN, Pritchard

T, et al: A Menin-MLL inhibitor induces specific chromatin changes

and eradicates disease in models of MLL-rearranged leukemia. Cancer

Cell. 36:660–673.e11. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kühn MW, Song E, Feng Z, Sinha A, Chen CW,

Deshpande AJ, Cusan M, Farnoud N, Mupo A, Grove C, et al: Targeting

chromatin regulators inhibits leukemogenic gene expression in NPM1

mutant leukemia. Cancer Discov. 6:1166–1181. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cuglievan B, Kantarjian H, Rubnitz JE,

Cooper TM, Zwaan CM, Pollard JA, DiNardo CD, Kadia TM, Guest E,

Short NJ, et al: Menin inhibitors in pediatric acute leukemia: A

comprehensive review and recommendations to accelerate progress in

collaboration with adult leukemia and the international community.

Leukemia. 38:2073–2084. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Agarwal SK, Guru SC, Heppner C, Erdos MR,

Collins RM, Park SY, Saggar S, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS,

Spiegel AM, et al: Menin interacts with the AP1 transcription

factor JunD and represses JunD-activated transcription. Cell.

96:143–152. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Huang J, Gurung B, Wan B, Matkar S,

Veniaminova NA, Wan K, Merchant JL, Hua X and Lei M: The same

pocket in menin binds both MLL and JUND but has opposite effects on

transcription. Nature. 482:542–546. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fiskus W, Mill CP, Birdwell C, Davis JA,

Das K, Boettcher S, Kadia TM, DiNardo CD, Takahashi K, Loghavi S,

et al: Targeting of epigenetic co-dependencies enhances anti-AML

efficacy of Menin inhibitor in AML with MLL1-r or mutant NPM1.

Blood Cancer J. 13:532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Issa GC, Aldoss I, DiPersio J, Cuglievan

B, Stone R, Arellano M, Thirman MJ, Patel MR, Dickens DS, Shenoy S,

et al: The menin inhibitor revumenib in KMT2A-rearranged or

NPM1-mutant leukaemia. Nature. 615:920–924. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gundry MC, Goodell MA and Brunetti L: It's

all about MEis: Menin-MLL inhibition eradicates NPM1-Mutated and

MLL-rearranged acute leukemias in mice. Cancer Cell. 37:267–269.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Borkin D, He S, Miao H, Kempinska K,

Pollock J, Chase J, Purohit T, Malik B, Zhao T, Wang J, et al:

Pharmacologic inhibition of the Menin-MLL interaction blocks

progression of MLL leukemia in vivo. Cancer Cell. 27:589–602. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Feng Z, Ma J and Hua X: Epigenetic

regulation by the menin pathway. Endocr Relat Cancer. 24:T147–T159.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yokoyama A and Cleary ML: Menin critically

links MLL proteins with LEDGF on cancer-associated target genes.

Cancer Cell. 14:36–46. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Adriaanse FRS, Schneider P,

Arentsen-Peters STCJM, Fonseca AMND, Stutterheim J, Pieters R,

Zwaan CM and Stam RW: Distinct responses to menin inhibition and

synergy with DOT1L inhibition in KMT2A-rearranged acute

lymphoblastic and myeloid leukemia. Int J Mol Sci. 25:60202024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kurmasheva RT, Bandyopadhyay A, Favours E,

Pozo VD, Ghilu S, Phelps DA, McGeehan GM, Erickson SW, Smith MA and

Houghton PJ: Evaluation of VTP-50469, a menin-MLL1 inhibitor,

against Ewing sarcoma xenograft models by the pediatric preclinical

testing consortium. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 67:e282842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nicholls SJ, Nissen SE, Fleming C, Urva S,

Suico J, Berg PH, Linnebjerg H, Ruotolo G, Turner PK and Michael

LF: Muvalaplin, an oral small molecule inhibitor of lipoprotein(a)

formation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 330:1042–1053. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Groenland SL, Martínez-Chávez A, van

Dongen MGJ, Beijnen JH, Schinkel AH, Huitema ADR and Steeghs N:

Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the

cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors palbociclib, ribociclib,

and abemaciclib. Clin Pharmacokinet. 59:1501–1520. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ianni A, Kumari P, Tarighi S, Braun T and

Vaquero A: SIRT7: A novel molecular target for personalized cancer

treatment? Oncogene. 43:993–1006. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Goes JVC, Carvalho LG, de Oliveira RTG,

Melo MML, Novaes LAC, Moreno DA, Gonçalves PG, Montefusco-Pereira

CV, Pinheiro RF and Ribeiro Junior HL: Role of sirtuins in the

pathobiology of onco-hematological diseases: A PROSPERO-registered

study and in silico analysis. Cancers (Basel). 14:46112022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cao Y, Xue Y, Xue L, Jiang X, Wang X,

Zhang Z, Yang J, Lu J, Zhang C, Wang W and Ning G: Hepatic menin

recruits SIRT1 to control liver steatosis through histone

deacetylation. J Hepatol. 59:1299–1306. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gang D, Hongwei H, Hedai L, Ming Z, Qian H

and Zhijun L: The tumor suppressor protein menin inhibits

NF-κB-mediated transactivation through recruitment of Sirt1 in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Biol Rep. 40:2461–2466. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hernández-Jiménez M, Hurtado O, Cuartero

MI, Ballesteros I, Moraga A, Pradillo JM, McBurney MW, Lizasoain I

and Moro MA: Silent information regulator 1 protects the brain

against cerebral ischemic damage. Stroke. 44:2333–2337. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Teng Y, Huang Y, Yu H, Wu C, Yan Q, Wang

Y, Yang M, Xie H, Wu T, Yang H and Zou J: Nimbolide targeting SIRT1

mitigates intervertebral disc degeneration by reprogramming

cholesterol metabolism and inhibiting inflammatory signaling. Acta

Pharm Sin B. 13:2269–2280. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhao X, Li M, Lu Y, Wang M, Xiao J, Xie Q,

He X and Shuai S: Sirt1 inhibits macrophage polarization and

inflammation in gouty arthritis by inhibiting the MAPK/NF-κB/AP-1

pathway and activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Inflamm Res.

73:1173–1184. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang Q, Yan C, Xin M, Han L, Zhang Y and

Sun M: Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1) overexpression in BaF3 cells contributes

to cell proliferation promotion, apoptosis resistance and

pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Med Sci Monit. 23:1477–1482.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kotas ME, Gorecki MC and Gillum MP:

Sirtuin-1 is a nutrient-dependent modulator of inflammation.

Adipocyte. 2:113–118. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu QJ, Zhang TN, Chen HH, Yu XF, Lv JL,

Liu YY, Liu YS, Zheng G, Zhao JQ, Wei YF, et al: The sirtuin family

in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:4022022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Alinari L, Mahasenan KV, Yan F, Karkhanis

V, Chung JH, Smith EM, Quinion C, Smith PL, Kim L, Patton JT, et

al: Selective inhibition of protein arginine methyltransferase 5

blocks initiation and maintenance of B-cell transformation. Blood.

125:2530–2543. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Peng J, Ni B, Li D, Cheng B and Yang R:

Overview of the PRMT6 modulators in cancer treatment: Current

progress and emerged opportunity. Eur J Med Chem. 279:1168572024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Qian K, Hu H, Xu H and Zheng YG: Detection

of PRMT1 inhibitors with stopped flow fluorescence. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 3:62018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Abe Y and Tanaka N: Fine-Tuning of GLI

activity through arginine methylation: Its mechanisms and function.

Cells. 9:19732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Gurung B, Feng Z, Iwamoto DV, Thiel A, Jin

G, Fan CM, Ng JM, Curran T and Hua X: Menin epigenetically

represses Hedgehog signaling in MEN1 tumor syndrome. Cancer Res.

73:2650–2658. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kim H and Ronai ZA: PRMT5 function and

targeting in cancer. Cell Stress. 4:199–215. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Padeken J, Methot SP and Gasser SM:

Establishment of H3K9-methylated heterochromatin and its functions

in tissue differentiation and maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

23:623–640. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Song TY, Lim J, Kim B, Han JW, Youn HD and

Cho EJ: The role of tumor suppressor menin in IL-6 regulation in

mouse islet tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 51:308–313.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Mei Y, Ren K, Liu Y, Ma A, Xia Z, Han X,

Li E, Tariq H, Bao H, Xie X, et al: Bone marrow-confined IL-6

signaling mediates the progression of myelodysplastic syndromes to

acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest. 132:e1526732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Burger R: Impact of interleukin-6 in

hematological malignancies. Transfus Med Hemother. 40:336–343.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kaser EC, Zhao L, D'Mello KP, Zhu Z, Xiao

H, Wakefield MR, Bai Q and Fang Y: The role of various interleukins

in acute myeloid leukemia. Med Oncol. 38:552021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yao X, Huang J, Zhong H, Shen N, Faggioni

R, Fung M and Yao Y: Targeting interleukin-6 in inflammatory

autoimmune diseases and cancers. Pharmacol Ther. 141:125–139. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Qin R, Wang T, He W, Wei W, Liu S, Gao M

and Huang Z: Jak2/STAT6/c-Myc pathway is vital to the pathogenicity

of Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia caused by

P190(BCR-ABL). Cell Commun Signal. 21:272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Di Francesco B, Verzella D, Capece D,

Vecchiotti D, Di Vito Nolfi M, Flati I, Cornice J, Di Padova M,

Angelucci A, Alesse E and Zazzeroni F: NF-κB: A druggable target in

acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers (Basel). 14:35572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Láinez-González D, Alonso-Aguado AB and

Alonso-Dominguez JM: Understanding the Wnt signaling pathway in

acute myeloid leukemia stem cells: A feasible key against relapses.

Biology (Basel). 12:6832023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Liu P, Shi C, Qiu L, Shang D, Lu Z, Tu Z

and Liu H: Menin signaling and therapeutic targeting in breast

cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 51:1011182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Paneni F, Osto E, Costantino S, Mateescu

B, Briand S, Coppolino G, Perna E, Mocharla P, Akhmedov A, Kubant

R, et al: Deletion of the activated protein-1 transcription factor

JunD induces oxidative stress and accelerates age-related

endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 127:1229–1240. e1–e21. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Gallo A, Cuozzo C, Esposito I, Maggiolini

M, Bonofiglio D, Vivacqua A, Garramone M, Weiss C, Bohmann D and

Musti AM: Menin uncouples Elk-1, JunD and c-Jun phosphorylation

from MAP kinase activation. Oncogene. 21:6434–6445. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Dockray GJ: Keeping neuroendocrine cells

in check: Roles for TGFbeta, Smads, and menin? Gut. 52:1237–1239.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Hendy GN, Kaji H, Sowa H, Lebrun JJ and

Canaff L: Menin and TGF-beta superfamily member signaling via the

Smad pathway in pituitary, parathyroid and osteoblast. Horm Metab

Res. 37:375–379. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Matkar S, Thiel A and Hua X: Menin: A

scaffold protein that controls gene expression and cell signaling.

Trends Biochem Sci. 38:394–402. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Sowa H, Kaji H, Hendy GN, Canaff L, Komori

T, Sugimoto T and Chihara K: Menin is required for bone

morphogenetic protein 2- and transforming growth factor

beta-regulated osteoblastic differentiation through interaction

with Smads and Runx2. J Biol Chem. 279:40267–40275. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Chen H, Liu H and Qing G: Targeting

oncogenic Myc as a strategy for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 3:52018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, Fang F, Huss M, Vega

VB, Wong E, Orlov YL, Zhang W, Jiang J, et al: Integration of

external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network

in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 133:1106–1117. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Wu G, Yuan M, Shen S, Ma X, Fang J, Zhu L,

Sun L, Liu Z, He X, Huang D, et al: Menin enhances c-Myc-mediated

transcription to promote cancer progression. Nat Commun.

8:152782017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhou X, Zhang L, Aryal S, Veasey V, Tajik

A, Restelli C, Moreira S, Zhang P, Zhang Y, Hope KJ, et al:

Epigenetic regulation of noncanonical menin targets modulates menin

inhibitor response in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 144:2018–2032.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Tsai JW, Cejas P, Wang DK, Patel S, Wu DW,

Arounleut P, Wei X, Zhou N, Syamala S, Dubois FPB, et al: FOXR2 is

an epigenetically regulated pan-cancer oncogene that activates ETS

transcriptional circuits. Cancer Res. 82:2980–3001. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zhuang K, Leng L, Su X, Wang S, Su Y, Chen

Y, Yuan Z, Zi L, Li J, Xie W, et al: Menin deficiency induces

autism-like behaviors by regulating foxg1 transcription and

participates in foxg1-related encephalopathy. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e23079532024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Dreijerink KMA, Groner AC, Vos ESM,

Font-Tello A, Gu L, Chi D, Chi D, Reyes J, Cook J, Lim E, et al:

Enhancer-mediated oncogenic function of the menin tumor suppressor

in breast cancer. Cell Rep. 18:2359–2372. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Jiang Z, Shi D, Tu Y, Tian J, Zhang W,

Xing B, Wang J, Liu S, Lou J, Gustafsson JÅ, et al: Human proislet

peptide promotes pancreatic progenitor cells to ameliorate diabetes

through FOXO1/menin-mediated epigenetic regulation. Diabetes.

67:1345–1355. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Bonnavion R, Teinturier R, Gherardi S,

Leteurtre E, Yu R, Cordier-Bussat M, Du R, Pattou F, Vantyghem MC,

Bertolino P, et al: Foxa2, a novel protein partner of the tumour

suppressor menin, is deregulated in mouse and human MEN1

glucagonomas. J Pathol. 242:90–101. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Nusse R and Clevers H: Wnt/β-catenin

signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell.

169:985–999. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Bonnet C, Brahmbhatt A, Deng SX and Zheng

JJ: Wnt signaling activation: Targets and therapeutic opportunities

for stem cell therapy and regenerative medicine. RSC Chem Biol.

2:1144–1157. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Steinhart Z and Angers S: Wnt signaling in

development and tissue homeostasis. Development. 145:dev1465892018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang

X, Zhou Z, Shu G and Yin G: Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function,

biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 7:32022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Xiang Z, Wang Y, Ma X, Song S, He Y, Zhou

J, Feng L, Yang S, Wu Y, Yu B, et al: Targeting the

NOTCH2/ADAM10/TCF7L2 Axis-mediated transcriptional regulation of

Wnt pathway suppresses tumor growth and enhances chemosensitivity

in colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e24057582025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Hao J, Liu C, Gu Z, Yang X, Lan X and Guo

X: Dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling contributes to

intestinal inflammation through regulation of group 3 innate

lymphoid cells. Nat Commun. 15:28202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Feng Q, Nie F, Gan L, Wei X, Liu P, Liu H,

Zhang K, Fang Z, Wang H and Fang N: Tripartite motif 31 drives

gastric cancer cell proliferation and invasion through activating

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by regulating Axin1 protein stability.

Sci Rep. 13:200992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Luo Y, Vlaeminck-Guillem V, Baron S,

Dallel S, Zhang CX and Le Romancer M: MEN1 silencing aggravates

tumorigenic potential of AR-independent prostate cancer cells

through nuclear translocation and activation of JunD and β-catenin.

J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:2702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Hagège H, Klous P, Braem C, Splinter E,

Dekker J, Cathala G, de Laat W and Forné T: Quantitative analysis

of chromosome conformation capture assays (3C-qPCR). Nat Protoc.

2:1722–1733. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Sancho A, Li S, Paul T, Zhang F, Aguilo F,

Vashisht A, Balasubramaniyan N, Leleiko NS, Suchy FJ, Wohlschlegel

JA, et al: CHD6 regulates the topological arrangement of the CFTR

locus. Hum Mol Genet. 24:2724–2732. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Wang Y, Krivtsov AV, Sinha AU, North TE,

Goessling W, Feng Z, Zon LI and Armstrong SA: The Wnt/beta-catenin

pathway is required for the development of leukemia stem cells in

AML. Science. 327:1650–1653. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Wagstaff M, Coke B, Hodgkiss GR and Morgan

RG: Targeting β-catenin in acute myeloid leukaemia: Past present,

and future perspectives. Biosci Rep. 42:2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Khan I, Eklund EE and Gartel AL:

Therapeutic vulnerabilities of transcription factors in AML. Mol

Cancer Ther. 20:229–237. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Font-Díaz J, Jiménez-Panizo A, Caelles C,

Vivanco MD, Pérez P, Aranda A, Estébanez-Perpiñá E, Castrillo A,

Ricote M and Valledor AF: Nuclear receptors: Lipid and hormone

sensors with essential roles in the control of cancer development.

Semin Cancer Biol. 73:58–75. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Yang Z, Gimple RC, Zhou N, Zhao L,

Gustafsson J and Zhou S: Targeting nuclear receptors for cancer

therapy: Premises, promises, and challenges. Trends Cancer.

7:541–556. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Lian F, Wang Y, Xiao Y, Wu X, Xu H, Liang

L and Yang X: Activated farnesoid X receptor attenuates apoptosis

and liver injury in autoimmune hepatitis. Mol Med Rep.

12:5821–5827. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Xu Y, Huangyang P, Wang Y, Xue L,

Devericks E, Nguyen HG, Yu X, Oses-Prieto JA, Burlingame AL,

Miglani S, et al: ERα is an RNA-binding protein sustaining tumor

cell survival and drug resistance. Cell. 184:5215–5229.e17. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Manickasamy MK, Jayaprakash S, Girisa S,

Kumar A, Lam HY, Okina E, Eng H, Alqahtani MS, Abbas M, Sethi G, et

al: Delineating the role of nuclear receptors in colorectal cancer,

a focused review. Discov Oncol. 15:412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Sun Y, Xie J, Cai S, Wang Q, Feng Z, Li Y,

Lu JJ, Chen W and Ye Z: Elevated expression of nuclear

receptor-binding SET domain 3 promotes pancreatic cancer cell

growth. Cell Death Dis. 12:9132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Luo Y, Vlaeminck-Guillem V, Teinturier R,

Abou Ziki R, Bertolino P, Le Romancer M and Zhang CX: The scaffold

protein menin is essential for activating the MYC locus and

MYC-mediated androgen receptor transcription in androgen

receptor-dependent prostate cancer cells. Cancer Commun (Lond).

41:1427–1430. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Zhang T, Ma C, Zhang Z, Zhang H and Hu H:

NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. MedComm (2020).

2:618–653. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

He G and Karin M: NF-κB and STAT3 - key

players in liver inflammation and cancer. Cell Res. 21:159–168.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD,

Jones DR, Frye RA and Mayo MW: Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent

transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J.

23:2369–2380. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Yokoyama A, Somervaille TC, Smith KS,

Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Meyerson M and Cleary ML: The menin tumor

suppressor protein is an essential oncogenic cofactor for

MLL-associated leukemogenesis. Cell. 123:207–218. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Mullard A: FDA approves first biparatopic

antibody therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 24:72025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Falini B, Brunetti L, Sportoletti P and

Martelli MP: NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: From bench to

bedside. Blood. 136:1707–1721. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Falini B, Gjertsen BT and Andresen V: The

acidic stretch and the C-terminal nuclear export signal motif of

NPM1 mutant: Are they druggable in AML? Leukemia. 37:2173–2175.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Perner F, Stein EM, Wenge DV, Singh S, Kim

J, Apazidis A, Rahnamoun H, Anand D, Marinaccio C, Hatton C, et al:

MEN1 mutations mediate clinical resistance to menin inhibition.

Nature. 615:913–919. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Brunetti L, Gundry MC, Sorcini D, Guzman

AG, Huang YH, Ramabadran R, Gionfriddo I, Mezzasoma F, Milano F,

Nabet B, et al: Mutant NPM1 maintains the leukemic state through

HOX expression. Cancer Cell. 34:499–512.e9. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Krivtsov AV and Armstrong SA: MLL

translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell

development. Nat Rev Cancer. 7:823–833. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Forgione MO, McClure BJ, Eadie LN, Yeung

DT and White DL: KMT2A rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukaemia:

Unravelling the genomic complexity and heterogeneity of this

high-risk disease. Cancer Lett. 469:410–418. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Thorsteinsdottir U, Kroon E, Jerome L,

Blasi F and Sauvageau G: Defining roles for HOX and MEIS1 genes in

induction of acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Cell Biol. 21:224–234.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Grembecka J, He S, Shi A, Purohit T,

Muntean AG, Sorenson RJ, Showalter HD, Murai MJ, Belcher AM,

Hartley T, et al: Menin-MLL inhibitors reverse oncogenic activity

of MLL fusion proteins in leukemia. Nat Chem Biol. 8:277–284. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Uckelmann HJ, Kim SM, Wong EM, Hatton C,

Giovinazzo H, Gadrey JY, Krivtsov AV, Rücker FG, Döhner K, McGeehan

GM, et al: Therapeutic targeting of preleukemia cells in a mouse

model of NPM1 mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Science. 367:586–590.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Di Fazio P: Targeting menin: A promising

therapeutic strategy for susceptible acute leukemia subtypes.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Nadiminti KVG, Sahasrabudhe KD and Liu H:

Menin inhibitors for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia:

Challenges and opportunities ahead. J Hematol Oncol. 17:1132024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Wang R, Xu P, Chang LL, Zhang SZ and Zhu

HH: Targeted therapy in NPM1-mutated AML: Knowns and unknowns.

Front Oncol. 12:9726062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Uckelmann HJ, Haarer EL, Takeda R, Wong

EM, Hatton C, Marinaccio C, Perner F, Rajput M, Antonissen NJC, Wen

Y, et al: Mutant NPM1 directly regulates oncogenic transcription in

acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov. 13:746–765. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Wang XQD, Fan D, Han Q, Liu Y, Miao H,

Wang X, Li Q, Chen D, Gore H, Himadewi P, et al: Mutant NPM1

hijacks transcriptional hubs to maintain pathogenic gene programs

in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov. 13:724–745. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Dillon LW, Gui G, Page KM, Ravindra N,

Wong ZC, Andrew G, Mukherjee D, Zeger SL, El Chaer F, Spellman S,

et al: DNA sequencing to detect residual disease in adults with

acute myeloid leukemia prior to hematopoietic cell transplant.

JAMA. 329:745–755. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Mill CP, Fiskus W, Das K, Davis JA,

Birdwell CE, Kadia TM, DiNardo CD, Daver N, Takahashi K, Sasaki K,

et al: Causal linkage of presence of mutant NPM1 to efficacy of

novel therapeutic agents against AML cells with mutant NPM1.

Leukemia. 37:1336–1348. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Huls G, Woolthuis CM and Schuringa JJ:

Menin inhibitors in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood.

145:561–566. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Issa GC, Aldoss I, Thirman MJ, DiPersio J,

Arellano M, Blachly JS, Mannis GN, Perl A, Dickens DS, McMahon CM,

et al: Menin inhibition with revumenib for KMT2A-Rearranged

relapsed or refractory acute leukemia (AUGMENT-101). J Clin Oncol.

43:75–84. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Wang ES, Issa GC, Erba HP, Altman JK,

Montesinos P, DeBotton S, Walter RB, Pettit K, Savona MR, Shah MV,

et al: Ziftomenib in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia

(KOMET-001): A multicentre, open-label, multi-cohort, phase 1

trial. Lancet Oncol. 25:1310–1324. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Miao H, Chen D, Ropa J, Purohit T, Kim E,

Sulis ML, Ferrando A, Cierpicki T and Grembecka J: Combination of

menin and kinase inhibitors as an effective treatment for leukemia

with NUP98 translocations. Leukemia. 38:1674–1687. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Fiskus W, Piel J, Collins M, Hentemann M,

Cuglievan B, Mill CP, Birdwell CE, Das K, Davis JA, Hou H, et al:

BRG1/BRM inhibitor targets AML stem cells and exerts superior

preclinical efficacy combined with BET or menin inhibitor. Blood.

143:2059–2072. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Kwon MC, Thuring JW, Querolle O, Dai X,

Verhulst T, Pande V, Marien A, Goffin D, Wenge DV, Yue H, et al:

Preclinical efficacy of the potent, selective menin-KMT2A inhibitor

JNJ-75276617 (bleximenib) in KMT2A- and NPM1-altered leukemias.

Blood. 144:1206–1220. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

An ZY and Zhang XH: Menin inhibitors for

acute myeloid leukemia: latest updates from the 2023 ASH Annual

Meeting. J Hematol Oncol. 17:522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Heikamp EB, Henrich JA, Perner F, Wong EM,

Hatton C, Wen Y, Barwe SP, Gopalakrishnapillai A, Xu H, Uckelmann

HJ, et al: The menin-MLL1 interaction is a molecular dependency in

NUP98-rearranged AML. Blood. 139:894–906. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|