Thyroid cancer, a leading concern among endocrine

system tumors, has demonstrated a consistent rise in global

incidence. Thyroid cancer ranked as the seventh most common

malignancy globally in 2022, with >821,000 reported cases

(1). The diverse pathological types

and clinical manifestations of thyroid cancer pose notable

challenges for both medical research and clinical management. As it

occurs within a vital organ within the human endocrine system,

thyroid gland dysfunction not only disrupts metabolic homeostasis

but also endangers overall health when compromised by cancer

progression (2).

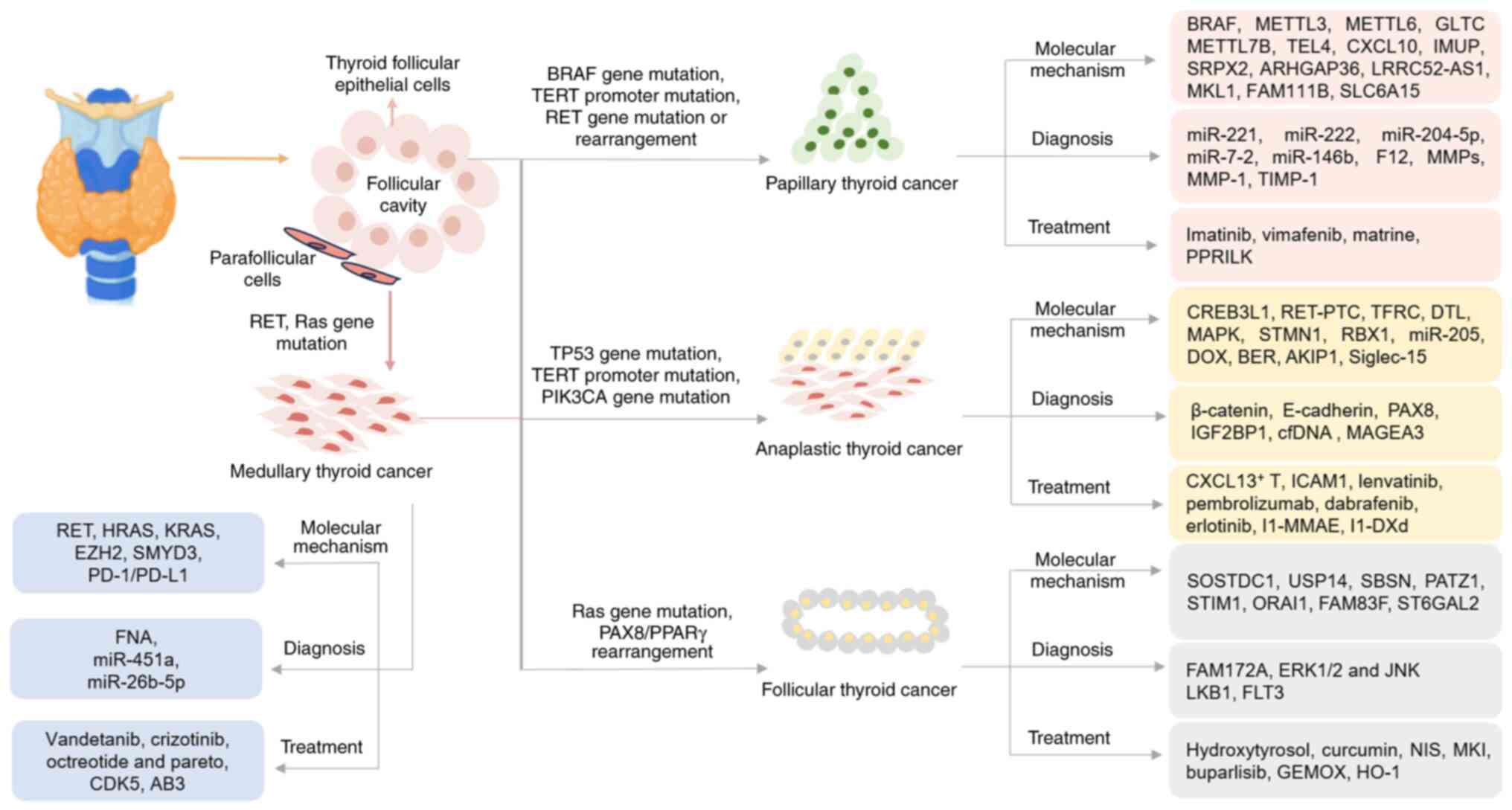

Thyroid cancer arises from follicular or

parafollicular epithelial cells, representing the most common head

and neck malignancy. Thyroid cancer can be histologically

classified into several types, including papillary thyroid

carcinoma (PTC), follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC), medullary

thyroid carcinoma (MTC) and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC),

with PTC being the most prevalent. The global incidence of thyroid

cancer continues to rise, particularly among high-risk groups, such

as women, individuals with genetic predispositions or those with a

family history of the disease (3).

PTC, accounting for 85–90% of thyroid malignancies,

is characterized by papillary structures and a favorable prognosis,

yet recurrence and lymph node metastasis remain clinical challenges

(4). FTC, comprising ~10% of cases,

exhibits greater invasiveness and a higher probability of distant

metastasis to the lungs and bones compared with PTC, which

necessitates precise and individualized treatment strategies

(5). MTC, a neuroendocrine

malignancy originating from calcitonin-secreting parafollicular C

cells, constitutes 1–5% of thyroid malignancies. The pathogenesis

of MTC has been significantly associated with rearranged during

transfection (RET) proto-oncogene mutations and exhibits notable

hereditary predisposition, notably mediated by gain-of-function

mutations, which necessitates comprehensive genetic counseling and

multidisciplinary approaches for optimal management (6). ATC, although accounting for only 1–2%

of all thyroid malignancies, is the most aggressive form. It is

characterized by poor differentiation, rapid progression, a poor

prognosis and limited responsiveness to current treatments

(7).

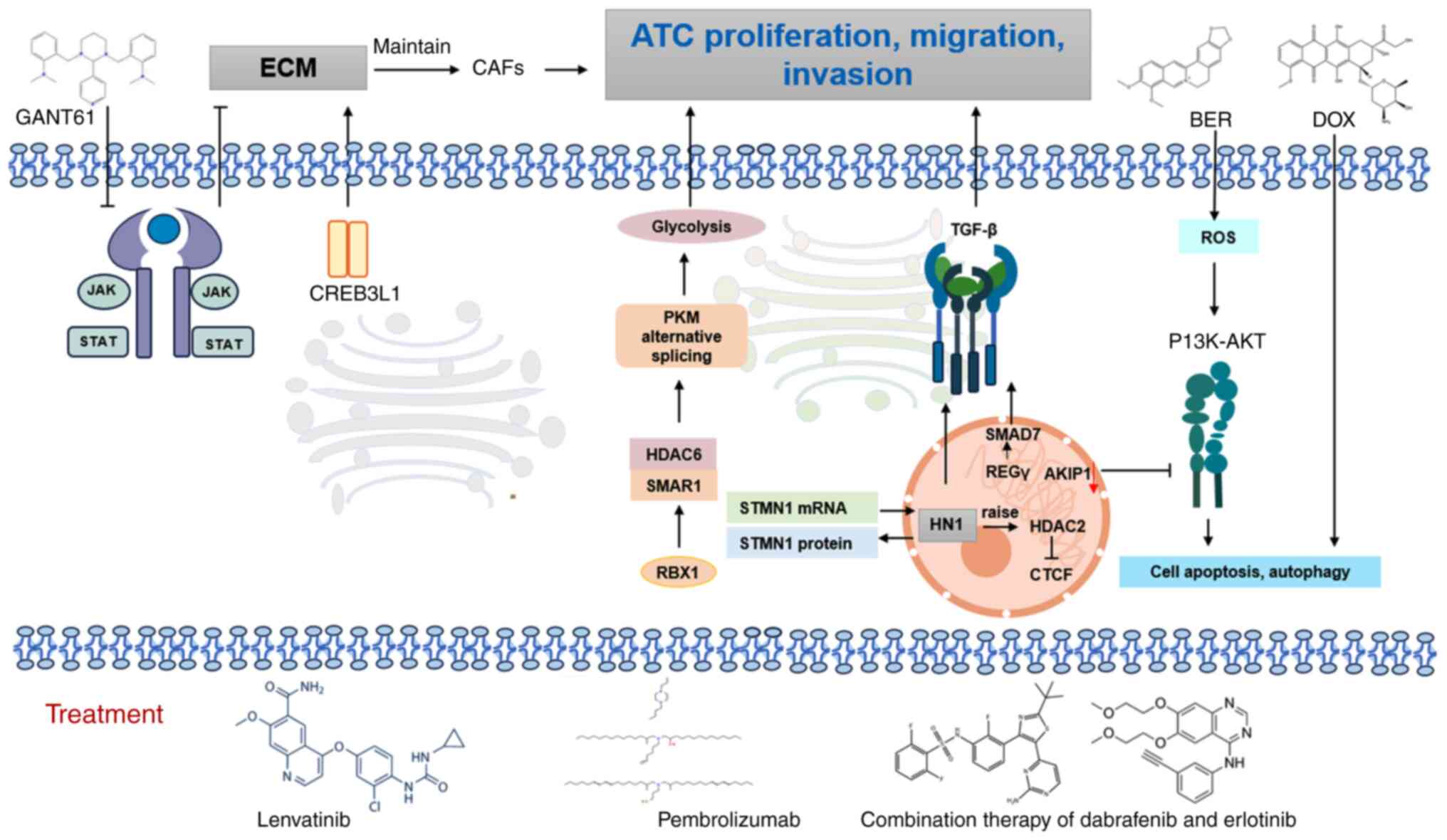

The present comprehensive review systematically

evaluates recent progress in understanding the four principal

histological subtypes of thyroid carcinoma. While PTC remains the

most extensively characterized subtype, notable knowledge gaps

persist regarding the signaling cascades and metabolic

reprogramming in FTC, MTC and ATC, as schematically illustrated in

Fig. 1. The present review

summarizes notable findings spanning molecular pathogenesis,

diagnostic biomarker development and emerging therapeutic

modalities specific to these understudied thyroid cancers.

Particular emphasis has been placed on delineating subtype-specific

molecular signatures that may inform precision diagnostics and

targeted intervention strategies. The present review aims to

establish a comprehensive framework to guide subsequent mechanistic

investigations and clinical translation in thyroid oncology.

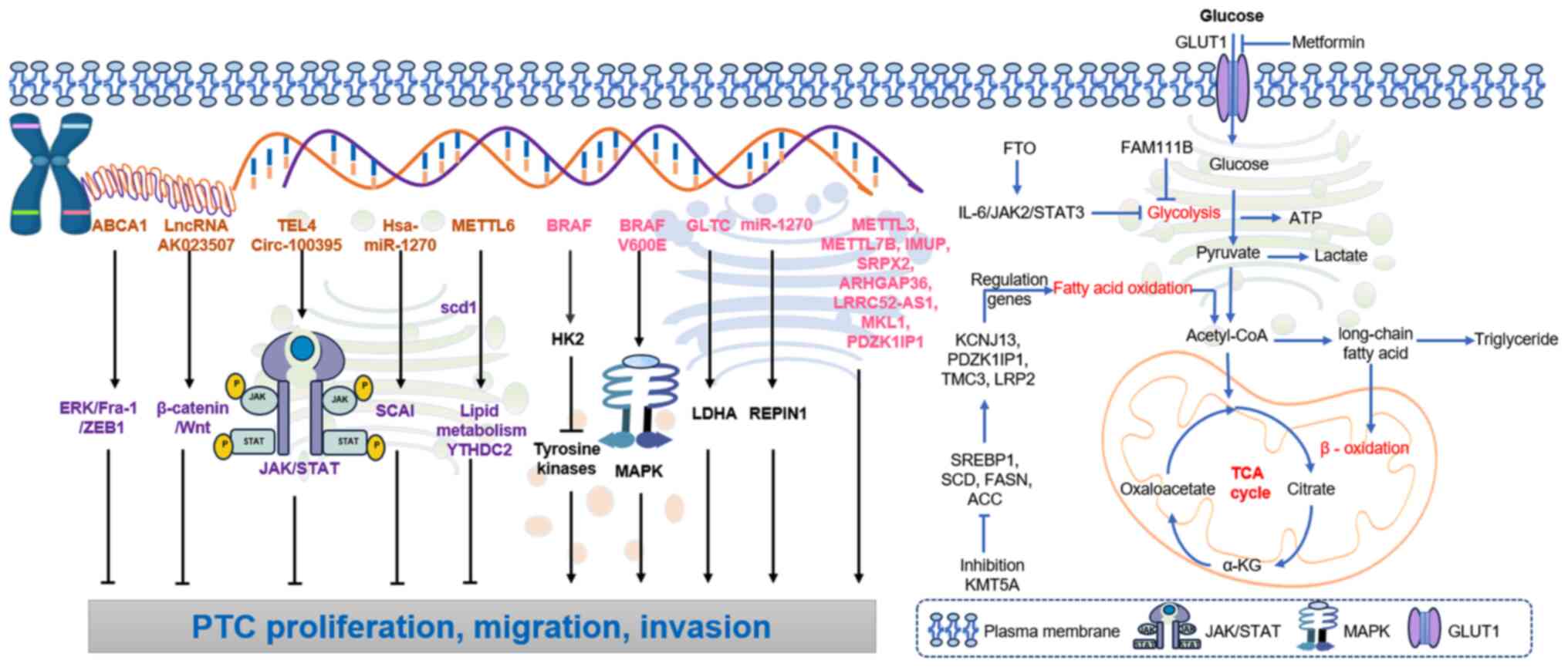

PTC is the most prevalent form of thyroid cancer and

its incidence is rising globally. The pathogenesis of PTC is

intricate, involving a range of genetic and epigenetic alterations.

Among these, the BRAF V600E gene mutation is one of the most

frequently observed molecular events in PTC, the pooled sensitivity

of IHC for detecting BRAF V600E mutation was 96.8% [95% confidence

interval (CI): 94.1–98.3%] (8).

This mutation primarily impacts the MAPK signaling pathway,

resulting in the persistent activation of the downstream MEK

protein, which in turn promotes cell proliferation, differentiation

and tumorigenesis (9). A thorough

understanding of these molecular mechanisms not only elucidates the

pathogenesis of PTC but also identifies key molecular markers for

its diagnosis, treatment and prognostic evaluation in the

future.

PTC accounts for 85–90% of all thyroid cancer cases,

with its molecular mechanisms being both complex and diverse

(4). These mechanisms involve

various genetic mutations (such as BRAF, RAS, RET/PTC) and the

dysregulated expression of non-coding RNAs (10). Recent studies have highlighted

genes, like methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), METTL16, METTL7B and

transducin-like enhancer of split 4, closely associated with the

onset progression invasiveness and prognosis of PTC. Emerging

evidence identifies long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) among key

non-coding RNA regulators driving PTC pathogenesis (11–14).

Deciphering these molecular pathways enhances mechanistic insights

into PTC pathogenesis, while establishing essential frameworks for

early detection, therapeutic development and outcome prediction

(Fig. 2).

The molecular landscape of PTC is notably shaped by

mutations in various coding genes, with the BRAF gene mutation

being one of the most prevalent. Located on chromosome 7q34, BRAF

serves a key role in the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway. The

BRAF V600E mutation is present in up to 90% of PTC cases and leads

to the continuous activation of the MEK protein, which promotes

cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. This mutation also

upregulates hexokinase-2 (HK2), which inhibits upstream tyrosine

kinases, thereby further contributing to PTC growth (15). The BRAF V600E mutation enhances cell

proliferation and tumor growth by activating the MAPK signaling

pathway.

Additional genes, such as METTL3, METTL6 and

METTL7B, are associated with the proliferation and migration of PTC

(11,12). Overexpression of METTL3 and METTL7B

has been shown to facilitate tumor progression, while METTL16

interacts with stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 to activate lipid

metabolism pathways and with YT521-B homology domain-containing

protein 2, which inhibits PTC progression (13). By contrast, transducin-like enhancer

of split 4 negatively associates with the proliferation, migration

and invasion of PTC cells, while promoting the activation of the

JAK/STAT signaling pathway (14).

The potassium calcium-activated channel subfamily N

member 4 (KCNN4) gene serves an essential role in modulating the

proliferation, migration and invasion of PTC cells. Low expression

levels of KCNN4 not only hamper tumor progression but also enhance

the expression of apoptosis-related genes, which suppresses

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (16). By contrast, the expression of PDZ

domain-containing kidney-specific protein 1-interacting protein 1

(PDZK1IP1) enhances the proliferation and migration of PTC while

inhibiting apoptosis (17).

Furthermore, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 expression is

downregulated in PTC, which has been closely associated with

immunity and cellular defense mechanisms (18). C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 gene

upregulation in PTC tissues provides a potential therapeutic target

(19). Furthermore, the

downregulation of Bcl-2-like protein 11 in PTC results in increased

microRNA (miRNA/miR)-300 expression, which influences PTC activity

and behavior (20).

Lastly, the genes immortalization-upregulated

protein (IMUP), sushi repeat-containing protein, X-linked 2

(SRPX2), ρ GTPase-activating protein 36, leucine-rich

repeat-containing protein 52 antisense RNA 1 and megakaryoblastic

leukemia 1 are positively associated with the progression of PTC.

High expression levels of these genes contributed to the

proliferation, migration and invasion of PTC cells, which suggests

their utility as potential therapeutic targets (21–25).

In glutamine-affinity PTC, the inhibition of glutamine breakdown

can reduce mitochondrial respiration, thereby inhibiting PTC

activity (26). The family with

sequence similarity 111 member B (FAM111B) motif inhibits the

glycolytic process in PTC, which in turn prevents its

proliferation, migration and invasion (27). As a tumor suppressor, solute carrier

family 6 member 15 (SLC6A15) serves a key role in inhibiting the

migration and invasion of PTC. The effect of SLC6A15 on PTC cells

was associated with intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1).

SLC6A15 functions as a tumor suppressor gene and may represent a

potential target for the treatment of PTC in the future (28).

Non-coding RNAs, including lncRNAs and miRNAs, are

emerging as key regulators in the pathogenesis of PTC Among the

lncRNAs, glycolysis-associated regulator of lactate dehydrogenase A

(LDHA) post-transcriptional modification 1 (GLTC), which interacts

with LDHA, serves an essential role in aerobic glycolysis and

enhances cell viability in PTC (29–31).

Elevated expression levels of GLTC in PTC tissues correlates with

more extensive metastasis, larger tumor size and worse prognosis.

Inhibition of GLTC negates the effects of K155-succinylated LDHA,

particularly on radioiodine iodine refractory, which suggests its

potential as an oncogenic target in PTC (32). Bioinformatic analyses of miRNA-mRNA

regulatory networks reveal that miR-204-5p exhibits the broadest

regulatory capacity, targeting multiple genes, including tumor

necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 12A (TNFRSF12A).

Furthermore, miR-146b, miR-204 and miR-7-2 demonstrate

stage-specific expression patterns in PTC, while elevated TNFRSF12A

and claudin-1 levels correlate with adverse prognostic outcomes in

this malignancy (23,33). The expression level of lncRNA

metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) is

also upregulated in PTC, suggesting that MALAT1 may serve a

carcinogenic role and could potentially serve as a diagnostic

marker for PTC (34).

Hsa-miR-1270 is significantly upregulated in PTC

cell lines (such as TPC-1 and K1) and human PTC tumors. The

regulatory mechanism of hsa-miR-1270 in PTC appears to be primarily

associated with the suppressor of cancer cell invasion (SCAI) gene.

hsa-miR-1270 can bind to SCAI and negatively regulate the

expression of the SCAI gene in PTC cells. Downregulation of

hsa-miR-1270 expression inhibits the development of PTC cells both

in vitro and in vivo (35). By contrast, overexpression of

miR-1270 promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of PTC

cells by targeting REPIN1 (36).

Circ-0011058 positively regulates yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1),

thereby enhancing PTC proliferation, angiogenesis and

radioresistance by acting as a sponge for miR-335-5p (37). Furthermore, miR-106a has been

implicated in the carcinogenesis of the lncRNA highly upregulated

in liver cancer (HULC). Both HULC and miR-106a are positively

associated with cell viability, proliferation, migration, invasion

capacity, and the volume and weight of PTC tumors (38). HULC overexpression enhances the

activity of the PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways by

upregulating the expression of miR-106a. A positive correlation

exists between the expression levels of HOXA3 and HOXA-AS2, with

HOXA-AS2 being notably expressed in the cytoplasm of PTC cells

(39). Furthermore, FOXD2-AS1

upregulates HOXA3 expression by binding to miR-15a-5p. The global

function of the HOXA-AS2/miR-15a-5p/HOXA3 axis serves a notable

role in the progression of PTC (40).

In summary, the dysregulation of both coding and

non-coding genes significantly contributes to the molecular

mechanisms of PTC. These insights not only enhance current

understanding of PTC biology but also open the door for novel

diagnostic and therapeutic strategies targeting specific genes and

pathways involved in PTC progression.

PTC involves a variety of signaling pathways that

regulate its development, proliferation and invasiveness. IMUP and

eva-1 homolog A (EVA1A), along with the key effectors of the Hippo

pathway, YAP1 and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding

motif, can inhibit the proliferation, migration and invasion of PTC

cells, while also inducing apoptosis. EVA1A promotes the

progression and EMT of PTC through the Hippo signaling pathway

(41). lncRNA AK023507 inhibits the

proliferation and metastasis of PTC cells by targeting the

β-catenin/Wnt signaling pathway (42). In PTC cell lines, the

tumor-suppressive effect of Tektin-4 (TEKT4) downregulation was

associated with the silencing of the PI3K/AKT pathway. The

downregulation of TEKT4 expression inhibited cell proliferation,

colony formation, migration and invasion (43). Overexpression of circ-100395

significantly reduced aerobic glycolysis, proliferation, migration

and invasion, while downregulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, an

effect that was reversed by the PI3K activator 740Y-P. Circ-100395

may exert an anticancer effect in PTC cells by inhibiting the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway (44).

SRPX2 promotes proliferation and migration of PTC.

SRPX2 serves a role in the malignant development of PTC by

activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (22). ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

serves a key role in inhibiting PTC lung metastasis through the

ERK/Fos-related antigen 1/zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1

(ZEB1) pathway (45). METTL3

inactivates the NF-κB pathway through cellular

reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog and v-rel

reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A, regulates tumor

growth together with YT521-B homology domain-containing family

protein 2 and tumor-associated neutrophil infiltration, and serves

a key tumor suppressor role in PTC carcinogenesis, which expands

current understanding of the relationship between

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification and tumor microenvironment

(TME) plasticity (46).

FTO can inhibit glycolysis and the growth of PTC,

and its expression has been significantly downregulated in PTC

tissues. FTO suppresses the expression of apolipoprotein E (APOE)

through insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2

(IGF2BP2)-mediated m6A modification and may inhibit glycolytic

metabolism in PTC by regulating the IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling

pathway, thereby impeding tumor growth (47). Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1)

promotes the proliferation and invasion of PTC via the STAT3

signaling pathway (36,47). Key oncogenes, including leucine-rich

repeat kinase 2, solute carrier family 34 member 2, mucin 1,

forkhead box protein Q1 and keratin 19, are upregulated in

BRAF-enriched subtypes and are associated with oncogenic MAPK and

PI3K/AKT signaling pathways (48).

The present review provides a key appraisal of the

oncogenic signaling network architecture underlying PTC

pathogenesis. Emerging evidence demonstrates that a complex

interplay of mitogenic pathways, including MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT

cascades, coordinately regulates malignant phenotype evolution

through modulation of proliferation kinetics, metastatic

competence, apoptotic resistance and epithelial-mesenchymal

plasticity in PTC models. Particular emphasis has been placed on

delineating pathway crosstalk mechanisms that create therapeutic

vulnerabilities, with concurrent discussion of preclinical

validation strategies for molecularly targeted interventions.

Thyroid cancer is a prevalent malignant tumor within

the endocrine system, and its occurrence and progression are

closely associated with various metabolic processes. Recent studies

have demonstrated that the metabolomic profiles of serum samples

from patients with thyroid cancer differ significantly from those

of healthy adults. These differences encompass multiple metabolic

pathways, including glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism and amino

acid metabolism (49,50).

FAM111B expression is negatively associated with

glucose uptake and inhibits the growth, migration, invasion and

glycolysis of PTC. Methylation of FAM111B mediated by DNA

(cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 3β (DNMT3B) accelerates the growth,

migration, invasion and glycolysis of PTC cells. The

estradiol/DNMT3B/FAM111B axis is a key regulator of PTC growth and

progression (27). FTO functions as

a tumor suppressor gene in PTC, inhibiting tumor glycolysis.

Research has demonstrated that FTO suppresses the expression of

APOE through IGF2BP2-mediated mRNA modification and may inhibit

glycolytic metabolism in PTC by modulating the IL-6/JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway, thereby restraining tumor growth (51). Pyruvate carboxylase influences the

proliferation and motility of thyroid cell lines. PTC demonstrates

metabolic reprogramming characterized by enhanced tricarboxylic

acid (TCA) cycle flux that sustains oncogenic bioenergetic demands

while generating biosynthetic precursors (52). Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is

elevated in thyroid cancer cells compared with stromal cells.

PiggyBac transposable element derived 5 (PGBD5), a gene associated

with glucose metabolism, is enriched in inflammatory response

pathways and has been correlated with high levels of immune cell

infiltration in groups sensitive to paclitaxel and anti-PD-1

treatment. Therefore, PGBD5 may serve as a therapeutic target to

inhibit the progression of PTC (53).

Emerging evidence highlights the pivotal role of

metabolic reprogramming in PTC progression, with glucose and lipid

metabolism emerging as key regulatory axes. In glucose metabolism,

pharmacological modulation using metformin suppresses HK2 and

glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) expression, impairing glycolytic flux

in PTC models both in vitro and in vivo, which

suggests its therapeutic potential as a metabolic adjuvant

(54). This effect is

synergistically enhanced by BTB domain and CNC homology 1

knockdown, which induces metabolic inflexibility by inhibiting

mitochondrial respiration, thereby sensitizing cancer cells to

metformin-mediated cytotoxicity (55). Complementary strategies targeting

glucose transport (SGLT2 inhibitors) and mitochondrial energetics

(mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inhibition)

further demonstrate metabolic vulnerabilities in PTC, associating

glucose uptake restriction with oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis

and energy crisis (56,57).

Obesity-associated PTC progression associates with

METTL16-mediated lipid metabolic activation, while lysine

methyltransferase 5A (KMT5A) regulates oncogenic lipogenesis

through sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1/SCD/fatty acid

synthase (FASN) signaling, modulating redox balance and

chemotherapy response (13,58). Prognostically relevant lipid

signatures involving PDZK1IP1, transmembrane channel-like 3,

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 2 and potassium

inwardly-rectifying channel subfamily J member 13 genes underscore

the clinical implications of lipid metabolism in tumor evolution

(59). Beyond canonical pathways,

metabolic crosstalk between tumors and microenvironmental

adipocytes drives local lipid restructuring, characterized by

elevated very long chain saturated fatty acids and polyunsaturated

fatty acid metabolism in peritumoral thyroid tissue (60). These findings collectively identify

metabolic plasticity, characterized by predominant aerobic

glycolysis activity, glutamine dependency and enhanced lipid

anabolism, as a hallmark feature of PTC malignancy, with both

diagnostic significance and therapeutic potential (61).

Current understanding of metabolic reprogramming in

PTC remains predominantly focused on glucose and lipid homeostasis,

with amino acid metabolism representing a key knowledge gap in PTC

pathobiology. The present review systematically examines

therapeutically exploitable mechanisms in glycolytic and lipogenic

pathways, while Table I delineates

emerging insights into amino acid metabolic networks that warrant

further mechanistic interrogation (26,51,53,58,61–101).

The paucity of comprehensive studies on glutaminolysis,

serine-glycine axis modulation and branched-chain amino acid

utilization underscores an urgent need for multi-omics

investigations to map the complete metabolic landscape of PTC.

Increased expression of Stanniocalcin 1 (STC1) in

PTC tissues has been associated with an elevated risk of lymph node

metastasis. Furthermore, elevated STC1 expression in thyroid

lesions may aid in the diagnosis of PTC, which makes it a

potentially valuable marker for predicting disease prognosis

(102). miRNAs such as miR-221,

miR-222, miR-204-5p, miR-7-2 and miR-146b have been identified as

potential biomarkers for staging PTC. Furthermore, fibronectin 1,

claudin-1, TNFRSF12A, ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1, cyclin T1,

specificity protein 1 and chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein

4 may serve as novel prognostic biomarkers for PTC. The expression

of coagulation factor XII (F12) may influence the overall survival

(OS) of patients with PTC by modulating metabolic pathways,

suggesting that F12 could be a reliable diagnostic and prognostic

biomarker for PTC (103).

Downregulation of Alu-mediated CDKN1A/p21 transcriptional regulator

(APTR) has been associated with tumorigenesis and suggests the

potential diagnostic value of APTR in patients with PTC and ATC

(104). Lectin microarray analysis

of salivary glycoproteins in patients with PTC revealed

postoperative normalization of six lectin-binding patterns to

levels comparable with healthy volunteers. These findings highlight

the potential utility of salivary glycome profiling as a

non-invasive prognostic biomarker for PTC. Quantitative alterations

in specific lectin-reactive glycostructures may enable clinical

stratification of disease progression and therapeutic monitoring in

PTC management (55). Matrix

metalloproteinases and their inhibitors play a role in PTC cervical

metastasis, therefore high expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1

(MMP-1) and its tissue inhibitors in tumor tissue can serve as

predictive indicators for tumor metastasis (105). In PTC detection diagnosis,

immunohistochemical results demonstrated that E-cadherin

negativity, and p53 and BRAF positivity are notable risk factors,

while radioiodine refractory therapy can reduce the risk of

recurrence (106). A six-gene

diagnostic panel incorporating transient receptor potential cation

channel subfamily C member 5, teneurin transmembrane protein 1,

neural EGFL-like 2, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, solute carrier

family 35 member F3 and autism susceptibility candidate 2

demonstrated robust discriminative capacity for differentiating PTC

from benign thyroid tissues (107).

Our current routine diagnostic practice for PTC

conforms to established medical pathological standards. However,

the diagnosis in most early-stage cases is typically established

using ultrasound (108–110) and subsequently confirmed by a

series of more complex tests (111,112), such as ultrasound-guided

fine-needle aspiration biopsy for the definitive diagnosis of PTC.

Therefore, the present study summarized the relevant literature on

the diagnosis of PTC, with the aim of enhancing current

capabilities in the prevention and diagnosis of this condition.

In terms of tumor growth, the combination of

imatinib and vemurafenib resulted in nearly complete tumor

disappearance, with a reduction of ~90%. However, monotherapy was

significantly less effective in BCPAP cells expressing

platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)α (11). Matrine has been shown to induce

apoptosis in PTC cells in vitro and inhibit tumor growth by

downregulating miR-182-5p in vivo. Matrine, a natural

product derived from marine sources, has emerged as a promising

alternative for the treatment of various types of cancer, including

exerting inhibitory effects in liver cancer and colorectal cancer.

Emerging pharmacological evidence demonstrates that Matrine exerts

potent anti-neoplastic effects in PTC through multi-modal

pro-apoptotic mechanisms (113,114). In PTC-derived TPC-1 and B-CPAP

cell models, Matrine induces mitochondrial apoptotic pathway

activation characterized by Bcl-2 suppression and caspase-3

activation cascade. Mechanistically, this alkaloid compound

mediates tumor growth inhibition via epigenetic regulation of

oncogenic miR-182-5p, establishing this miRNA as a therapeutically

actionable node in the anti-PTC activity of Matrine (115). The dual regulatory capacity of

Matrine in modulating canonical apoptotic signaling pathways and

epigenetic RNA networks establishes this alkaloid as a novel

therapeutic agent for combination therapies targeting molecular

vulnerabilities in PTC.

BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi), including vemurafenib and

dabrafenib, have demonstrated notable therapeutic efficacy in the

treatment of PTC harboring the BRAF V600E mutation (92,116).

However, the development of drug resistance is primarily attributed

to the adaptive reactivation of the MAPK signaling pathway,

exemplified by mechanisms such as neuroblastoma Ras viral oncogene

homolog mutations or the presence of BRAF splice variants that

sustain continuous ERK phosphorylation (117). Furthermore, compensatory

activation of parallel signaling pathways, notably the IGF-1

receptor (IGF-1R)-mediated PI3K/AKT pathway, contributes to

resistance (118). In this

context, Sui et al (119)

identified nerve/glial antigen 2 (NG2) as a key quaternary

structural component implicated in BRAF inhibitor resistance within

BRAF V600E-mutant PTC. NG2 modulates the activity of multiple

receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), including EGFR, fibroblast growth

factor receptor (FGFR), human EGFR2, insulin-like growth factor 1

receptor (IGF-1R), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

(VEGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), via

the RTK signaling axis, thereby promoting resistance to BRAFi

through the activation of ERK and AKT signaling cascades. These

findings indicated that treatment approaches with triple targeted

inhibition (such as simultaneously blocking BRAF, MEK and EGFR) or

combined immunotherapies might be needed to address drug resistance

challenges in this setting (119).

While surgical resection remains the cornerstone of

PTC management, emerging multimodal strategies address key

limitations in recurrence prevention and metastatic control. Recent

advances in nano-theranostics have yielded TME-responsive platforms

such as the polypyrrole (Ppy)-poly(vinylimine)-siILK nanocomplex,

which integrates photothermal ablation with gene silencing for

synergistic anti-PTC efficacy (120). This system leverages

near-infrared-activated gelatin-stabilized Ppy for precise

photothermal conversion while exploiting pH-responsive charge

inversion to mediate lysosomal escape of siILK payloads, achieving

dual suppression of primary tumor growth and lymphatic metastasis.

Real-time visualization of tumor-specific Ppy localization further

enhances therapeutic precision.

Complementary to such technological innovations,

clinical optimization requires consideration of endocrine-metabolic

variables. Thyroglobulin antibody dynamics, modulated by iodine

homeostasis in thyroid TMEs, may serve as both prognostic

biomarkers and therapeutic adjuvants, which necessitates

personalized dietary iodine regulation during intervention

(121).

Collectively, these developments underscore the

paradigm shift toward precision multimodality in PTC care. Although

radical surgery remains primary for tumor debulking, its

combination with photothermal-gene therapy and metabolic modulation

provides a multimodal strategy against locoregional recurrence and

systemic dissemination, which are key unmet needs in advanced PTC

management.

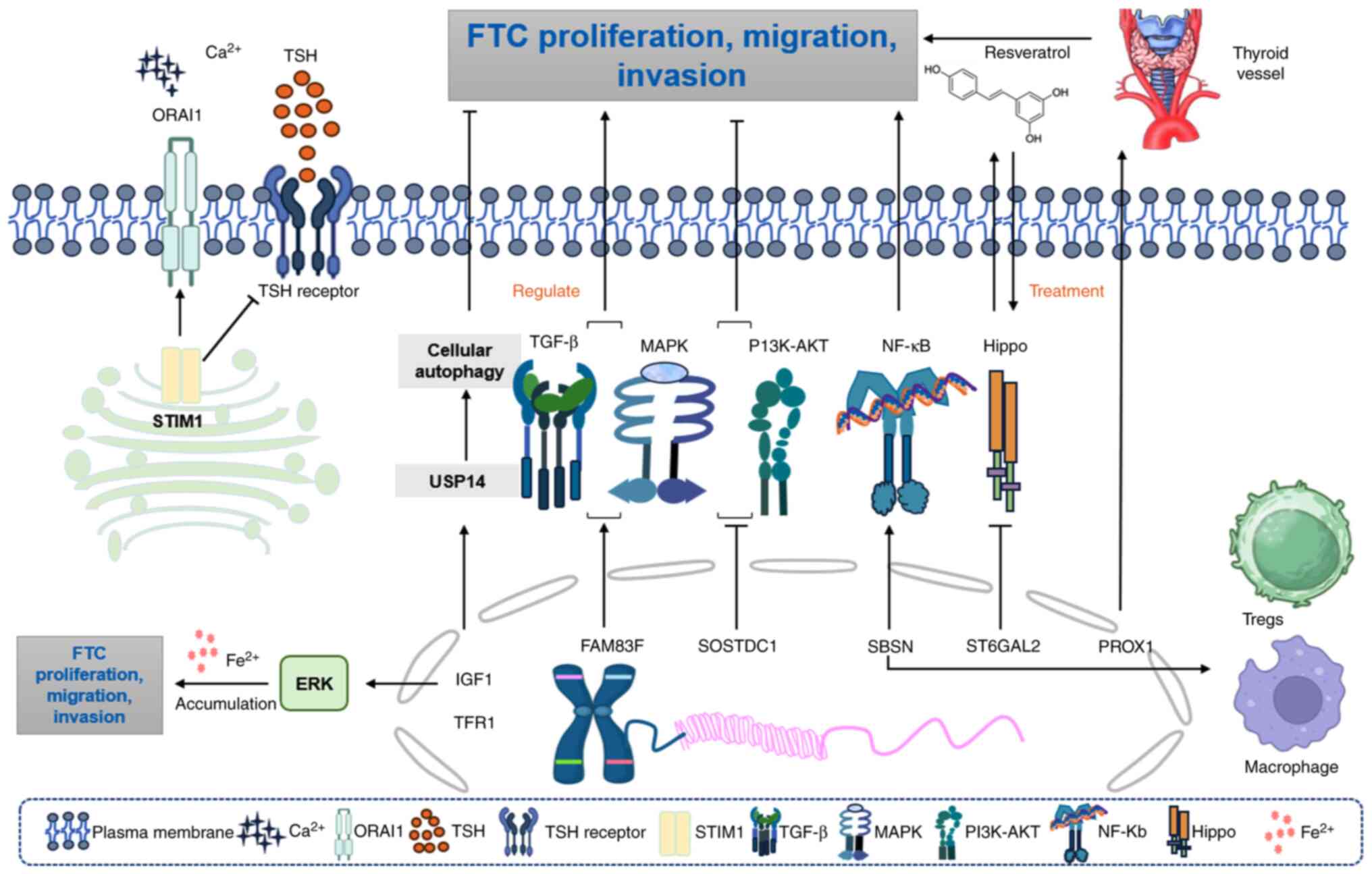

FTC is a notable type of thyroid cancer and its

incidence exhibits distinct trends (122–124) across various regions (125). The incidence rate of FTC in the

United States increased significantly from 3.98 in 1980–1984 to

9.88 in 2005–2009. In the United States, non-Hispanic whites have

the highest incidence rate of thyroid cancer, followed by

Asian/Pacific islanders, Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks. The

pathogenesis of FTC is highly complex, involving numerous genetic

and epigenetic alterations. Of these, mutations in the Ras gene are

among the most prevalent molecular events associated with FTC

(126), with the highest Ras

mutation rate (61.5%). Ras gene mutations primarily disrupt the

Ras-MAPK signaling pathway, which leads to the abnormal activation

of several downstream proteins, such as Raf. This disruption

results in aberrant cell proliferation, impaired differentiation

and tumor formation (127,128). Previous studies have demonstrated

that Ras gene mutations are not only associated with the

pathogenesis of FTC but that they are also closely associated with

the invasiveness, risk of recurrence and overall prognosis of the

disease (129,130).

lncRNAs may regulate the progression of FTC by

influencing cell proliferation, apoptosis, EMT and miRNA expression

(131).

1-[1-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-3-yl]-2-pyrrolidin-1-ylethanone (IU1)

inhibits FTC proliferation and migration by targeting

ubiquitin-specific protease 14 (USP14), a deubiquitinating enzyme

that affects various cellular processes, including cell survival,

DNA repair, endoplasmic reticulum stress, endocytosis and

inflammatory responses. IU1 induces autophagy and proteasomal

stimulation in a cell type-dependent manner, increasing autophagy

in ML1 cancer cells and resulting in decreased proliferation and

migration of these cells (132).

Piperonine induces apoptosis and autophagy in human FTC cells

through the reactive oxygen species (ROS)/AKT signaling pathway

(133). Aberrant regulation of

suprabasin (SBSN) has been implicated in the development of cancer

and immune disorders. The most abundant evidence regarding SBSN

comes from cancer research. SBSN expression is the response of

cancer cells to anti-tumor T-cell activity. The role of SBSN in

adapting to stress conditions, activating pro-survival signaling

pathways and angiogenesis is often associated with carcinogenic

effects. SBSN influences tumor cell migration, proliferation,

angiogenesis, immune cell infiltration and the cancer immune cycle

(134). The infiltration of M2

macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs) was significantly

increased in tumor tissues with high SBSN expression. SBSN may

serve a key role in the development of thyroid cancer, tumor

dedifferentiation and immunosuppression as an important regulator

of tumor immune cell infiltration. The pox virus and zinc finger

protein/BTB and AT-hook-containing zinc finger protein 1 gene can

inhibit the malignant phenotype of thyroid follicular epithelial

cells and thyroid cancer cells, and it participates in the

dedifferentiation process of thyroid cancer (135,136).

The knockdown of stromal interaction molecule 1

(STIM1) can reduce the invasion and proliferation of human FTC

cells while enhancing the expression of thyroid-specific proteins.

STIM1 and ORAI calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1

(ORAI1) calcium channels mediate store-operated calcium entry

(SOCE) and regulate various cellular functions. The presence of

STIM1 or ORAI1 enhances SOCE in thyroid cancer ML-1 cells, which

promotes invasion and the expression of primary

sphingosine-1-phosphate and VEGF-2 receptors (137,138). Compared with that in normal

tissues, STIM1 protein was upregulated in thyroid cancer tissues,

inhibiting the expression of the thyroid-stimulating hormone

receptor and thyroid-specific proteins, while increasing iodine

absorption (139).

Emerging evidence highlights key molecular drivers

in FTC pathogenesis, with dysregulated signaling networks and

intercellular communication mechanisms emerging as key therapeutic

targets (140,141). The transcription factor prospero

homeobox 1 orchestrates angiogenic programming during metastatic

dissemination through vascular remodeling mechanisms (142). Similarly, exosome-mediated

tumor-stromal crosstalk facilitates malignant progression, as

demonstrated by annexin A1-enriched vesicles from SW579 cells

inducing proliferative activation and EMT in recipient Nthy-ori3-1

cells via paracrine signaling (143).

Regarding the MAPK signaling pathway, sclerostin

domain containing 1 (SOSTDC1) inhibits the proliferation, migration

and EMT of FTC cells by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK

signaling pathways (144). By

contrast, family with sequence similarity 83 member F upregulation

serves a pro-cancer role by cross-activating follicular cell

transformation through synergizing with the MAPK/TGFβ pathway,

which activates thyroid cell migration and causes resistance to

chemotherapy (145). Furthermore,

β-galactoside α-2,6-sialyltransferase 2 (ST6GAL2)-mediated

glycosylation perturbation inhibits Hippo tumor suppressor

signaling, establishing a dual-drug node in FTC tumorigenesis

(146). Pharmacological modulation

using resveratrol reverses ST6GAL2-Hippo axis dysfunction, which

highlights the therapeutic potential of pathway-specific inhibitors

(146). Concurrently, iron

homeostasis disruption via transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1)-dependent

ERK hyperactivation creates metabolic vulnerabilities exploitable

through iron chelation strategies (147). Cell cycle control mechanisms

further contribute to FTC pathobiology. The BRCA1/cyclin-dependent

kinase inhibitor 2C tumor suppressor axis constrains cyclin

D-CDK4/6 signaling, with CDK4 inhibitor sensitivity demonstrating

clinical potential in cyclin D-dysregulated FTC subtypes (148). Genomic landscape analyses reveal

recurrent mutations in chromatin remodelers (for example, nuclear

receptor corepressor 1), mRNA processing factors [e.g., poly(A)

binding protein cytoplasmic 1/3] and mitotic regulators (e.g., cell

division cycle 27), which suggests epigenetic vulnerabilities

(149). TME reprogramming via

fibroblast-mediated signaling amplifies FTC aggressiveness,

highlighting stromal co-targeting strategies as promising

therapeutic frontiers (150).

As a marker for FTC, family with sequence similarity

172 member A (FAM172A) promotes the development of this malignancy.

FAM172A serves a key role in the pathogenesis of FTC through the

ERK1/2 and JNK signaling pathways. The downregulation of FAM172A

can inhibit the proliferation, invasion and migration of FTC cells

via these pathways (151).

Emerging insights into FTC pathogenesis reveal paradoxical

oncogenic signaling activation within canonical tumor suppressor

pathways. Mechanistic studies demonstrated that protein kinase

A-mediated adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

activation via liver kinase B1 (LKB1) phosphorylation exhibits

context-dependent tumorigenic effects, with accumulating

preclinical and clinical evidence associating LKB1 pathway

hyperactivation to FTC progression (152–154). Concurrently, genomic profiling of

thyroid malignancies identifies feline McDonough sarcoma-like

tyrosine kinase 3 domain mutations as recurrent targetable

alterations, although their functional contribution to FTC

oncogenesis and clinical utility for precision kinase inhibition

therapies remains to be fully elucidated (155).

Current therapeutic strategies for advanced FTC

encompass diverse advanced modalities, including radioactive iodine

(131I) therapy, multikinase inhibitors (MKIs) and RET/NTRK/ALK

inhibitors. These approaches target key molecular pathways and

resistance mechanisms to enhance therapeutic efficacy in refractory

cases.

Targeted therapeutic approaches primarily involve

multikinase inhibitors and PI3K pathway modulation. The treatment

of advanced FTC primarily relies on indirect evidence derived from

clinical trials of MKIs, which are associated with notable toxicity

and may adversely affect quality of life in patients. The antitumor

effect of the pan-class I PI3K inhibitor buparlisib on refractory

follicular carcinoma and poorly differentiated thyroid cancer

(PDTC) dysregulation was investigated, given that PI3K pathway

dysregulation is commonly observed in advanced FTC and PDTC, and

has been associated with tumorigenesis and disease progression. The

efficacy of buparlisib in the treatment of advanced FTC and PDTC

has been found to be limited. However, the observed reduction in

tumor growth rate may suggest that oncogenic pathways and/or escape

mechanisms are not entirely inhibited (156).

Natural compounds demonstrate antitumor effects

through redox modulation and signaling pathway regulation.

Hydroxytyrosol, a prominent phenolic compound present in olive oil,

exhibits antitumor effects attributed to its pro-oxidative

properties, as well as its capacity to inhibit cell proliferation

and promote apoptosis in various tumor cell lines, including MCF-7

and MDA-MB-231 (157). Notably,

high doses of hydroxytyrosol have been shown to induce apoptosis in

papillary and FTC cells (158).

Curcumin induces ferroptosis in FTC through heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)

upregulation (159). Mechanistic

studies have revealed that HO-1 serves as a key mediator of

oxidative stress regulation, with its abnormal upregulation

observed in FTC vs. adjacent tissues. By contrast, elevated HO-1

levels reduce cellular viability via ferroptosis pathway activation

(160,161). Curcumin exerts dual antitumor

effects by enhancing HO-1 expression to suppress FTC proliferation

while potentiating ferroptosis-mediated cell death. These findings

position the HO-1-ferroptosis axis as a key therapeutic target in

FTC pathogenesis (162). Matrine,

a bioactive alkaloid derived from Sophora flavescens,

exhibits anti-neoplastic effects in FTC by modulating the

miR-21/phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten

(PTEN)/AKT signaling axis. Mechanistic studies have demonstrated

that matrine suppresses miR-21 expression, thereby alleviating its

inhibitory effect on PTEN (163).

The subsequent upregulation of PTEN inactivates AKT

phosphorylation, which induces caspase-dependent apoptosis and

proliferation arrest in FTC-133 cells. This dual regulation of

miRNA and kinase signaling pathways highlights the therapeutic

potential of matrine in targeting FTC pathogenesis (163).

Molecular-targeted radiosensitization represents an

advanced strategy exploiting specific pathways to overcome

radioactive iodine (RAI) resistance. Sorafenib and sunitinib are

effective treatment options for delaying disease progression in

patients with RAI-refractory metastatic DTC, both demonstrating

acceptable safety profiles (164).

Furthermore, sunitinib appears to exhibit some efficacy even in

patients who experience disease progression following treatment

with sorafenib (165). Inhibition

of β-catenin expression may enhance the efficacy of radioiodine

treatment in invasive FTC cells by modulating the localization of

the sodium iodide symporter (NIS). Following the inhibition of

β-catenin expression, FTC cells that exhibit high levels of hypoxia

inducible factor-1α can be completely suppressed by radioiodine

treatment. This mechanism may be associated with the regulation of

NIS localization (166).

Chemotherapy remains an alternative for

multi-resistant cases. Conventional chemotherapy with a gemcitabine

plus oxaliplatin (GEMOX) regimen is an off-label treatment that

demonstrates some efficacy and a favorable safety profile in

advanced DTC. Dias et al (167) reported a case of metastatic FTC in

a patient who developed resistance to multiple therapies. Notably,

OS time appeared to be significantly prolonged by this chemotherapy

due to durable responses to GEMOX. In conclusion, GEMOX may be a

viable option for patients with thyroid cancer who do not respond

to MKIs.

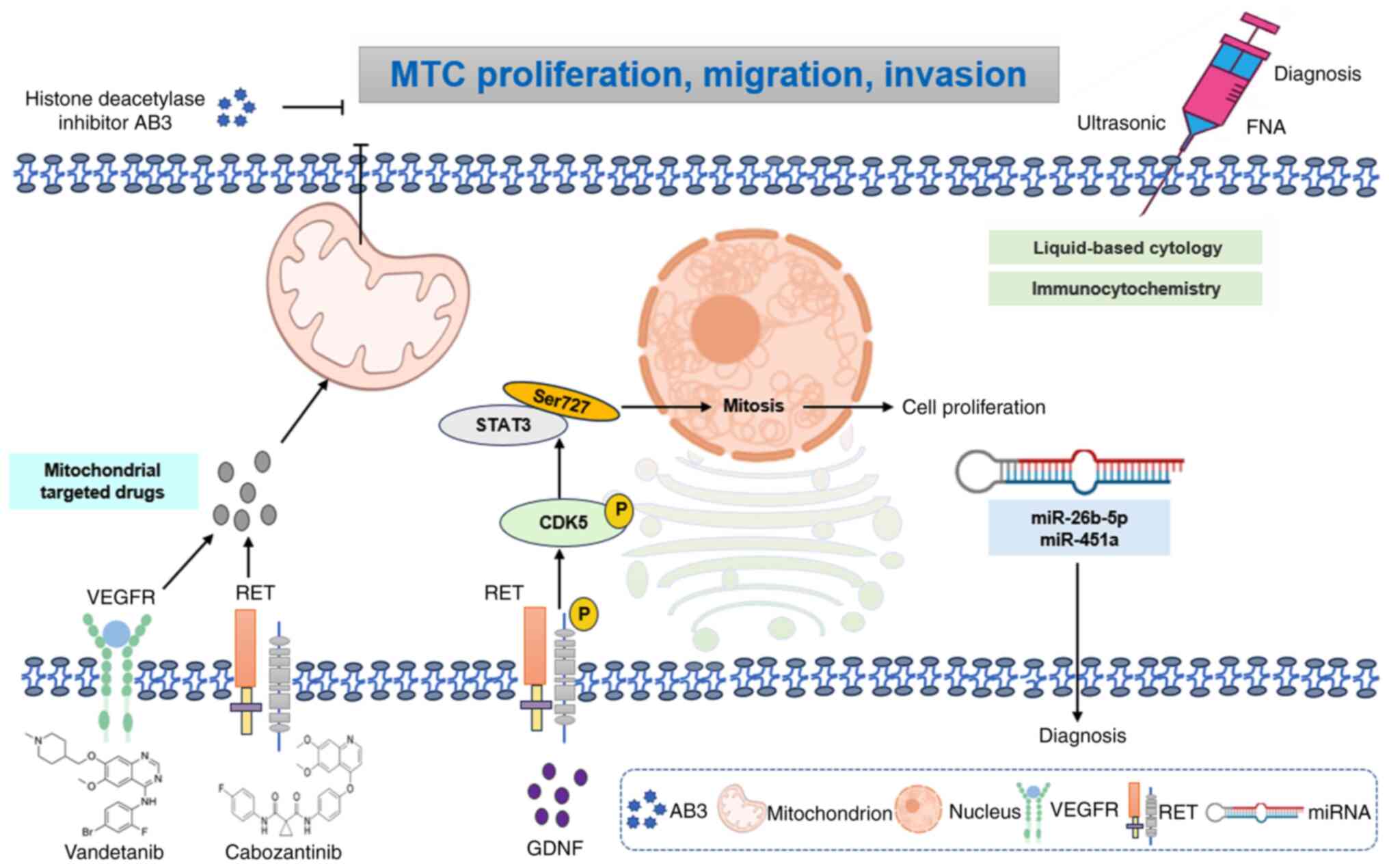

MTC is a neuroendocrine tumor that originates from

parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland. The molecular mechanisms

underlying MTC primarily involve mutations in the RET

proto-oncogene, which is the most prevalent genetic driver of this

cancer (191). Mutations in the

RET gene result in alterations to the protein conformation in both

the inner and outer regions of cells, leading to excessive cell

proliferation and carcinogenesis. In addition to RET mutations,

alterations in the Ras gene also contribute to the pathogenesis of

MTC, particularly in cases of sporadic MTC.

Recent studies have identified novel pathogenic

genes associated with MTC, including BRAF and neurofibromatosis

type 1. These findings have enhanced current understanding of the

molecular pathological mechanisms underlying MTC. By analyzing the

genome, transcriptome, epigenome, proteome and phosphoproteome of a

substantial cohort of patients with MTC, researchers have, to the

best of our knowledge, created the first comprehensive proteomic

profile of MTC globally. This classification based on protein

expression profiles offers notable reference data for the precise

treatment of MTC (192–194).

Furthermore, the differential expression and gene

regulation of miRNA in MTC have garnered notable attention. These

studies offer potential biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for

the early diagnosis, accurate prognosis and gene therapy of MTC.

Collectively, the molecular mechanisms underlying MTC involve the

mutation and regulatory expression of multiple genes and these

findings contribute to the development of novel therapeutic

approaches and the enhancement of patient prognosis.

From a genetic perspective, RET, Harvey rat sarcoma

viral oncogene homolog (HRAS) and KRAS are the most notable genes

in MTC. Epigenetically, the development of MTC may be associated

with the methylation of the telomerase reverse transcriptase

promoter, upregulation of histone methyltransferases such as

enhancer of zeste homolog 2 and SET and murine homolog of

Max-domain containing 3, and notable fluctuations in non-coding

RNAs, including Ras association domain family member 1A (195). Unique transcriptional and

functional alterations in myeloid cells manifest prior to tumor

invasion and initiate within the bone marrow, indicating their

active role in shaping the tumor immune microenvironment (196). The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is expressed

in patients with MTC and has been significantly correlated with

intraoperative distant metastasis, positioning it as a potential

novel target for MTC treatment (197). A comprehensive understanding of

PD-1/PD-L1 expression and its association with immunotherapy

response may provide a key foundation to address refractory

MTC.

The management of locally advanced or metastatic MTC

necessitates a thorough workup, which includes the measurement of

serum procalcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen, assessment of

their doubling times and comprehensive imaging to evaluate the

extent of disease, aggressiveness and treatment requirements.

Recent advances in MTC diagnostics have established multimodal

approaches combining imaging guidance with molecular profiling.

Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration integrated with

liquid-based cytology and immunocytochemical analysis demonstrates

high preoperative diagnostic reliability for MTC through enhanced

cellular characterization (198).

Complementing this, circulating miRNA signatures (particularly

miR-26b-5p and miR-451a) exhibit robust diagnostic accuracy

metrics, offering non-invasive diagnostic adjuncts that synergize

with conventional techniques to enable precision risk

stratification (199). These

complementary strategies collectively advance MTC detection

paradigms by bridging cytomorphological precision with systemic

molecular biomarkers, underscoring their translational potential to

optimize clinical decision-making in thyroid oncology.

At the molecular level, mTOR pathway dysregulation

in MTC involves protein interacting with carboxyl terminus

1-mediated spliceosomal control, where its upregulation counteracts

everolimus-induced cytotoxicity via PTEN suppression and AKT-serine

(Ser)473 hyperphosphorylation, revealing novel resistance

mechanisms in neuroendocrine neoplasms (206). Concurrently, the glial cell

line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)/RET/CDK5/STAT3 signaling

axis emerged as a key driver of MTC progression. Mechanistic

studies reported that GDNF-induced RET phosphorylation activates

cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), which phosphorylates STAT3 at

Ser727 to sustain proliferative signaling (207–209). This pathway is enhanced by a

unique feature of MTC biology, such as direct RET-CDK5 interaction

(207).

These findings collectively map therapeutic

vulnerabilities across three dimensions: Neuroendocrine receptor

modulation, mTOR-AKT crosstalk and RET-kinase network targeting.

The identification of CDK5 as a RET-interacting kinase partner

particularly highlights its promise as a druggable node for

precision intervention strategies in advanced MTC management.

MTC often exhibits resistance to standard therapies,

which highlights the need for alternative treatment options. AB3, a

novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, has demonstrated efficacy in

inhibiting the proliferation of MTC cells in vitro. However,

its clinical application in vivo is hindered by poor water

solubility and stability, rapid clearance and insufficient tumor

targeting ability. Recent advancements in MTC nanotheranostics have

yielded precision-targeted delivery systems to optimize therapeutic

efficacy (210,211). Engineered single-molecule micelles

incorporating AB3 chemotherapeutic payloads with KE108

peptide-directed active targeting demonstrated enhanced

tumor-selective accumulation, achieving 2.3-fold greater

cytotoxicity in MTC models compared with free drug formulations.

This nanoplatform significantly suppresses tumor biomarker

expression while mitigating off-target effects key for patients

with comorbidities, particularly those with cardiovascular

complications requiring blood pressure stability (212). Furthermore, these micelles

demonstrated optimal anticancer effects in vivo without

notable systemic toxicity, which offers a promising strategy for

targeted therapy in MTC.

ATC is a highly aggressive endocrine malignancy

frequently presenting with extrathyroidal extension or distant

metastasis, ~70% of ATC spreads to nearby tissues such as the

trachea, esophagus and throat. The lungs, bones, and brain are also

common sites of ATC metastasis (256), although its pathogenesis remains

to be elucidated. Mechanistic studies have identified

cAMP-responsive element-binding protein 3-like 1 (CREB3L1) as a key

regulator maintaining cancer-associated fibroblast-like phenotypes

in ATC through extracellular matrix (ECM) signaling activation,

thereby remodeling TMEs to facilitate malignant progression

(257,258). The MAPK pathway, activated via

Ras/BRAF mutations or RET-PTC fusions, has been established as a

central oncogenic driver and therapeutic target for TKIs, while

secondary genomic alterations, including telomerase reverse

transcriptase (TERT) promoter and tumor protein p53 (TP53)

mutations, are correlated with advanced tumor evolution (259).

Molecular profiling analyses have revealed distinct

protein expression patterns in ATC, characterized by marked

upregulation of miRNA-regulated oncogenes, such as transferrin

receptor TFRC or CD71, and E3-ubiquitin ligase denticleless,

enabling reliable differentiation from PDTC (260). Angiogenesis and EMT are suppressed

by miR-205 through dual targeting of VEGF-A and ZEB1 (261). Epigenetic and transcriptional

regulators include sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin 15

(Siglec-15) (STAT1/STAT3-mediated proliferation/apoptosis)

(262), CCCTC-binding

factor/hematological and neurological expressed 1 (HN1; chromatin

remodeling of thyroid differentiation genes) (263), REGγ (TGF-β activation via SMAD7

degradation) (264) and HOXD9

(PI3K/AKT-driven proliferation/EMT through miR-451a/proteasome 20S

subunit β8 axis) (265). The

miR-17-92 cluster has been implicated in differentiation blockade,

with CRISPR/caspase 9-mediated knockdown restoring

thyrocyte-specific gene expression (266).

The stepwise molecular progression from DTC to ATC

entails early MAPK pathway alterations, including BRAF V600E and

Ras mutations, with subsequent acquisition of TERT and TP53

mutations driving dedifferentiation (267).

Cellular invasion mechanisms in ATC are regulated

through multiple molecular axes: HN1 stabilizes stathmin 1 (STMN1)

mRNA and prevents its ubiquitin-mediated degradation, thereby

enhancing invasiveness (268).

RING-box protein 1 (RBX1) modulates pyruvate kinase M1/2 splicing

via scaffold/matrix attachment region binding protein 1/histone

deacetylase 6 complex disruption, promoting metastasis and aerobic

glycolysis (269) and type 2

deiodinase depletion induces cellular senescence (270).

Capsaicin exemplifies the multimodal mechanisms of

pharmacological interventions, where transient receptor potential

vanilloid 1 activation initiates mitochondrial calcium overload

culminating in apoptosis (271).

Berberine induces ROS-dependent apoptosis/autophagy via

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway modulation and synergizes with doxorubicin

(272). A-kinase interacting

protein 1 knockdown enhances chemosensitivity through

PI3K/AKT/β-catenin inactivation (273). Gli-antagonist 61 inhibits EMT via

AKT/mTOR and JAK/STAT3 pathway suppression (274).

Taken together, ATC pathogenesis involves

multilevel dysregulation spanning CREB3L1-mediated ECM remodeling,

MAPK/TERT/TP53 genetic evolution and coordinated control of

invasion/metastasis by HN1/STMN1/RBX1. Therapeutic vulnerabilities

were identified in calcium signaling, redox balance, epigenetic

reprogramming and kinase cascades, which provides a molecular

framework for targeted intervention strategies.

Total residual disease remains the most key

prognostic indicator for ATC. Factors such as the capsule, marginal

status, percentage and size of the primary ATC are associated with

prognosis. Pure thyroid squamous cell carcinoma can be classified

as ATC if it shares a similar BRAF V600E genotype and prognosis.

Both BRAF-mutated and Ras-mutated ATC exhibit comparable metastatic

spread. The coexistence of BRAF or Ras mutations alongside TERT

mutations is correlated with a poor prognosis (7,275,276). Current diagnostic algorithms for

ATC incorporate three cardinal immunohistochemical features: i)

Aberrant nuclear β-catenin accumulation with membranous expression

loss, indicative of Wnt pathway activation; ii) disrupted

E-cadherin localization patterns reflecting EMT; and iii) paired

box 8 nuclear expression deficiency marking thyroid differentiation

loss, collectively serving as histopathological hallmarks for ATC

confirmation (277).

Optical imaging has been shown to effectively

visualize cellular and tissue architectures through optical

absorption, refraction and scattering properties, enabling

functional assessment across organ systems and facilitating

diagnostic applications. This modality further demonstrates

therapeutic potential for targeted and non-invasive precision

treatment in thyroid carcinoma (278). Concurrently, contrast-enhanced

CT-based radiomics analysis exhibits notable discriminative

capacity in distinguishing ATC and PDTC from DTC in patients with

advanced thyroid malignancies (279).

IGF2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) is currently

regarded as the most promising single-gene marker for ATC, followed

by melanoma-associated antigen 3 (MAGEA3), representing an

advancement over existing techniques (280), like application of single-cell

sequencing technology and epigenetic analysis. The expression

levels of IGF2BP1 and MAGEA3 can effectively differentiate ATC from

PDTC. Furthermore, IGF2BP1 has the capability to identify ATC foci

within poorly differentiated FTC. Reliable markers are key for

distinguishing this high-grade malignancy (ATC) from other types of

thyroid cancer subtypes, thereby informing surgical decisions,

treatment options and post-resection or therapeutic monitoring

strategies (280).

Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has emerged as a

key biomarker for characterizing tumor molecular profiles in ATC.

Comparative analyses have demonstrated high concordance between

cfDNA-derived genetic alterations and tumor tissue-based

next-generation sequencing results, which supports the utility of

cfDNA in dynamically monitoring actionable mutations. These

findings underscore the clinical relevance of cfDNA in guiding

therapeutic decisions and prognostic stratification in ATC

management (281).

Similarly, previous studies in non-small cell lung

cancer have demonstrated that combined radiotherapy and anti-PD-L1

treatment induces the formation of spatially adjacent synergistic

units comprising CXCL13+CD8+ T cells and

CXCL9+ macrophages, whose effector molecules, including

granzyme B and IFN-γ, directly suppress tumor growth (291,292). Similarly, in lung adenocarcinoma

associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

CXCL13+CD8+ T cells cooperate with tumor

cells exhibiting high HLA class I expression to enhance

immunotherapy response rates (293). By contrast, within clear cell

renal cell carcinoma, CXCL13+CD8+ T cells

predominantly display a terminally exhausted phenotype associated

with unfavorable clinical outcomes. The high infiltration of

CXCL13+CD8+T cells can also demonstrate the

immune escape structure of CD8+T cells, characterized by

immune damage, increased tumor promoting cells and reduced

anti-tumor factors (294). These

observations underscore that the functional role of

CXCL13+ T cells is highly contingent upon the specific

TME context, including the composition and spatial arrangement of

coexisting immune cell populations. Therefore, in ATC,

CXCL13+ T cells both promote immune activation by

augmenting antitumor responses through TLS formation and may

increase risk of malignancy due to their exhausted phenotype and

associated systemic complications.

In therapeutic investigations, combination regimens

targeting both angiogenesis and immune checkpoints, such as

lenvatinib with pembrolizumab, demonstrated favorable clinical

outcomes. A retrospective study involving 6 metastatic ATC patients

receiving combination therapy with lenvatinib and pembrolizumab and

2 PDTC patients confirmed. These regimens achieved durable complete

remissions in subsets of patients with ATC and PDTC (295). Notably, BRAF-targeted strategies

continue to evolve. A subset of patients with BRAF-mutant ATC

exhibited significant tumor regression when treated with

neoadjuvant pembrolizumab followed by BRAF/MEK inhibitor

combinations, enabling subsequent curative resection (296). Mechanistic studies further

revealed that dabrafenib combined with erlotinib synergistically

suppresses MAPK/EGFR signaling pathways, as evidenced by

downregulation of p-MEK, p-ERK and p-EGFR in preclinical models

(297). This dual inhibition

strategy overcomes monotherapy resistance and significantly reduces

tumor burden in xenograft models (298).

Clinical trials evaluating PD-1 blockade in ATC

demonstrated durable responses across BRAF mutation statuses.

Spartalizumab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, achieved a 52.1%

1-year survival rate in patients who were PD-L1+, with

objective responses observed in both BRAF mutant and wild-type

cohorts (299). PD-L1 was

significantly upregulated in a subset of patients with advanced

ATC. Notably, PD-L1 expression in immune cells was detected in

11.1% of ATC cases (300).

Furthermore, monoclonal antibodies targeting PD-L1 have

demonstrated notable efficacy in inhibiting ATC tumor growth in

vivo (301). Siglec-15 has

emerged as a promising immunotherapeutic target in ATC, whose

function is to suppress T-cell activation by downregulating nuclear

factor of activated T cells (NFAT)1, NFAT2 and NF-κB signaling

pathways. Inhibition of Siglec-15 has been shown to enhance the

secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2 both in vitro and in vivo

(218). Furthermore, the

combination therapy of dabrafenib and trametinib has notably

transformed the treatment landscape for BRAF V600E-mutant ATC.

Despite initial responses, resistance to this targeted therapy

inevitably develops, leading to disease progression. Furthermore,

neoadjuvant BRAF-targeted therapy administered preoperatively has

demonstrated improvements in patient survival outcomes (302).

These findings underscore the potential of

immunotherapy as a backbone for multimodal treatment paradigms in

ATC. ICAM1 is a promising target for the treatment of ATC and PTC.

Two ICAM1-targeted antibody-drug conjugates (I1-MMAE and I1-DXd)

have been developed, exhibiting selective cytotoxicity against

proliferating ATC and PTC cells in vitro, while maintaining

minimal impact on non-proliferative cell populations (303). Preclinical evaluation further

demonstrated notable tumor regression in ATC and PTC xenograft

models following ADC administration (304). Similarly, a CD44-directed

nanodelivery system was engineered through tyrosine-hyaluronic

acid-polyethylenimine self-assembly, enabling simultaneous

131I/125I radiolabeling and encapsulation of p53 reactivation and

induction of massive apoptosis-1 (Prima-1), a p53 mutation-targeted

therapeutic agent. The 125I-labeled nanocomposites

achieved sustained tumor visualization and prolonged

radiosensitivity, while 131I-conjugated nanoparticles exerted

synergistic antitumor effects in ATC models through

Prima-1-mediated p53 reactivation and radiation potentiation

(305).

Recent advances in ATC therapeutics have revealed

several promising strategies. Emerging evidence suggests that

CXCL13+ T cell infiltration and nascent TLS formation

may serve as biomarkers for immunotherapy responsiveness. The

combined regimen of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab, when integrated

with BRAF/MEK inhibition, has demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in

molecularly defined ATC subsets. Notably, neoadjuvant applications

of pembrolizumab remain under clinical investigation (282,295,296). Pharmacodynamic studies have

indicated that dabrafenib-erlotinib co-administration achieves

synergistic tumor suppression through circumventing monotherapy

resistance mechanisms. PD-1 blockade via spartalizumab has induced

objective responses across diverse ATC histological variants,

including spindle cell variant, giant cell variant, and epithelioid

variant. Preclinical models further highlight the therapeutic

potential of CD44-directed nanocarriers co-delivering

131I radiotherapy and Prima-1-mediated p53 reactivation

(298,300,305). These multimodal approaches

collectively expand the therapeutic landscape for this aggressive

malignancy (Fig. 5).

In the field of thyroid cancer research, notable

progress has been made in recent years; however, several

limitations persist. Firstly, studies investigating the molecular

mechanisms and gene mutations associated with thyroid cancer have

identified the roles of various key genes (such as BRAF, RET and

Ras) (306–309). However, these studies do not fully

elucidate the occurrence and developmental processes of all types

of thyroid cancer. The intricate interactions between multiple

genetic mutations and environmental factors remain inadequately

understood, such as ionizing radiation induces DNA double strand

breaks, leading to RET/PTC rearrangements; excessive iodine can

promote BRAF V600E mutation, which increases the risk of PTC. These

poses presenting challenges in the pursuit of more effective

prevention and treatment strategies.

In the research and treatment of thyroid cancer, it

is imperative to focus on the early screening of high-risk groups,

the application of molecular markers in diagnosis and treatment,

and the development of individualized treatment strategies tailored

to the various pathological types of thyroid cancer (310). Concurrently, for advanced and

refractory cases, overcoming drug resistance and enhancing

treatment efficacy remain key areas of investigation. For instance,

in the case of highly malignant subtypes, such as ATC, treatment

options are currently limited and survival rates are dismal, which

necessitates the urgent identification of novel therapeutic targets

and strategies. Furthermore, despite the generally favorable

prognosis for DTC, the monitoring and management of recurrence and

metastasis continue to pose notable challenges in clinical practice

(311).

Targeted drug therapy has demonstrated notable

therapeutic potential in the management of thyroid cancer,

particularly for advanced or refractory cases. These therapies

inhibit tumor progression by focusing on specific molecular targets

that promote cancer cell proliferation. Common targeted drugs

include VEGFR inhibitors, such as pazopanib and sorafenib, which

primarily inhibit new angiogenesis and restrict tumor blood supply

(312–314). Furthermore, EGFR inhibitors,

including gefitinib and erlotinib (315), mainly function to inhibit tumor

cell proliferation and survival. Targeting the prevalent BRAF V600E

driver mutation in thyroid cancer subtypes, BRAFi, including

vemurafenib and dabrafenib, represent a mechanistically grounded

therapeutic strategy. Furthermore, RET inhibitors, such as

pralsetinib and selpercatinib, primarily inhibit key drivers of

MTC, such as RET gene fusion or mutation (316). Targeted therapies are

characterized by their high specificity, resulting in less impact

on normal cells and fewer side effects compared with conventional

chemotherapy; they can effectively control disease progression and

prolong progression-free survival, which makes them particularly

suitable for advanced cases that are not amenable to surgical or

radiotherapeutic interventions. However, the cost of targeted drugs

is typically high, which can impose economic burdens on patients

over the long term. Furthermore, drug resistance may develop, as

tumor cells can evolve novel mechanisms to evade treatment.

Potential side effects, including hypertension, diarrhea and rash

(317), necessitate long-term

management and continuous monitoring.

Drug resistance in BRAF V600E-mutant PTC to BRAFi

is characterized by a multifaceted mechanism encompassing

epigenetic regulation, signaling pathway reprogramming and

metabolic adaptation. For instance, Pit-Oct-Unc class 5 homeobox 1B

contributes to dabrafenib resistance by promoting stem cell-like

properties and activating the Taste 1 Receptor Member 1 signaling

axis (318). Similarly, NG2

(chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4) diminishes the efficacy of

BRAFi through feedback activation of the ERK/AKT pathway mediated

by multiple RTKs, including EGFR and FGFR (119). Furthermore, aberrant activation of

the JAK/STAT pathway exacerbates resistance via IFN regulatory

factor 1-driven immune evasion mechanisms, such as upregulation of

human leukocyte antigen A2 and ICAM-1 (118). Transcription factors Forkhead box

protein P2 and Src homology-2 domain-containing protein tyrosine

phosphatase 2 sustain the resistant phenotype by cross-activating

the lysophosphatidic acid receptor (LPAR)3/PI3K-AKT and MAPK/PI3K

pathways, respectively (319,320). At the metabolic level, myeloid

cell leukemia-1 inhibits apoptosis by maintaining mitochondrial

membrane stability, while resistance to ferroptosis mediated by the

arylsulfatase I-STAT3-epiregulin axis restricts the therapeutic

efficacy of sorafenib (321).

Collectively, these findings indicate that monotherapy targeting

BRAF is readily circumvented by compensatory mechanisms, which

underscores the urgent need for combinatorial therapeutic

strategies.

The mechanisms underlying drug resistance in ATC

are notably complex, frequently involving widespread dysregulation

of the transcriptome and epigenetic landscape. NOP2/Sun RNA

methyltransferase family member 2 (NSUN2)-mediated 5-methylcytosine

modification stabilizes ATP-binding cassette transporters via the

serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 6/UDP-N-acetylglucosamine

pyrophosphorylase 1 axis, thereby promoting multidrug resistance

(322). Furthermore, N-Myc

proto-oncogene (MYCN) induces paclitaxel resistance through

transcriptional reprogramming (323). Microenvironmental factors, such as

glutamate accumulation, inhibit lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1,

which results in persistent activation of the MAPK pathway and

reduced sensitivity to anlotinib (117). These interconnected mechanisms

collectively establish a ‘pan-drug resistance’ barrier, rendering

conventional chemotherapy and targeted therapies largely

ineffective in ATC.

Although BRAF/MEK inhibitors, including dabrafenib

and trametinib, have demonstrated high objective response rates

(ranging from 54 to 89%) in BRAF V600E-mutant thyroid cancer, their

long-term efficacy is compromised by the development of acquired

resistance (324,325). Combination immunotherapy

approaches, such as BRAFi combined with atezolizumab, have extended

the median survival time in patients with ATC to ~43 months;

however, the associated cumulative toxicities, including dysphoria

and fatigue, limit broader clinical application (326).

Additional challenges include histological

variability in response to targeted therapies. For instance,

lenvatinib only achieved an 11.9% 1-year survival rate in ATC

(327), while pazopanib combined

with chemoradiotherapy failed to significantly improve survival

outcomes, underscoring the limitations of VEGFR monotherapy

(219). The feasibility and safety

of metabolic interventions remains a challenge. Although melittin

combined with apatinib enhances antitumor efficacy by inducing

pyroptosis, optimizing the therapeutic-toxicity balance persists as

a key concern (220). A lack of

reliable predictive biomarkers complicates treatment. No current

biomarkers adequately forecast patient responses to NSUN2- or

MYCN-targeted therapies, which hampers patient stratification and

treatment personalization (322,323).

Future studies may continue to investigate the

molecular mechanisms underlying thyroid cancer, with particular

emphasis on key signaling pathways and gene variants in ATC. This

research will encompass the examination of oncogenes, tumor

suppressor genes, cell cycle regulatory genes and molecules that

interact with the TME. Further understanding of the molecular

heterogeneity of thyroid cancer will shift the focus of future

research towards personalized treatment strategies. This approach

can involve the selection of appropriate targeted therapies and

immunotherapy regimens based on the molecular characteristics of

individual tumors. For instance, the identification of driver

genes, such as the BRAF V600E mutation and RET/neurotrophic

tyrosine receptor kinase fusion, has informed the application of

targeted therapeutic agents (328). Concurrently, research may also

prioritize the development of novel targeted drugs and

immunotherapy techniques, as well as the integration of these

treatments with established methods such as surgery, radioiodine

therapy and TKIs to enhance treatment efficacy and improve patient

survival.

Through multi-omics studies, researchers may aim to

identify precise molecular markers of thyroid cancer, which could

potentially enhance patient stratification and risk assessment,

leading to more refined management strategies. Furthermore,

advancements in bioinformatics and artificial intelligence

technologies are expected to serve an increasingly vital role in

the diagnosis, treatment planning and prognostic evaluation of

thyroid cancer. For instance, artificial intelligence-based models

can assist in determining lymph node metastasis in DTC, thereby

improving diagnostic accuracy (329).

Research on thyroid cancer encompasses multiple

disciplines, including genetics, pathology, imaging, endocrinology

and oncology. Effectively integrating the resources and expertise

from these fields to establish a comprehensive interdisciplinary

research system is key to enhance the quality of thyroid cancer

research and its clinical applications. Clinical research must

persist in advancing efforts to validate the efficacy and safety of

novel treatment strategies and medications for patients.

Furthermore, translational research can facilitate the swift

application of laboratory findings to clinical settings, ensuring

that research outcomes benefit patients at the earliest

opportunity.

Thyroid cancer represents a highly heterogeneous

endocrine malignancy with significant differences in molecular

mechanisms, clinical presentations and therapeutic approaches

across its subtypes (PTC, FTC, MTC and ATC). This review delineates

key molecular characteristics of these four categories: PTC is

predominantly characterized by BRAF V600E mutations, FTC is

frequently associated with RAS mutations and MTC primarily

originates from RET proto-oncogene mutations, while ATC

demonstrates profound genomic instability evidenced by TP53 and

TERT promoter mutations. These molecular markers not only

facilitate disease diagnosis and prognostic stratification but also

provide foundational insights for targeted therapy development.

In diagnostic practice, integrating ultrasound,

fine-needle aspiration biopsy and molecular profiling, including

BRAF, RET and RAS mutation analysis substantially enhances

preoperative diagnostic precision. Regarding therapeutic

management, surgical resection remains the primary intervention for

localized tumors. For advanced or metastatic disease, however,

targeted therapies such as RET inhibitor selpercatinib and BRAF/MEK

inhibitor combinations alongside immunotherapy demonstrate

transformative potential. Particularly for aggressive ATC,

multimodal regimens combining surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy

and targeted agents may extend survival in selected patient

cohorts.

Notwithstanding substantial research advancements

in thyroid oncology, persistent challenges warrant attention.

Certain resistance mechanisms in FTC and ATC remain incompletely

elucidated. Comprehensive evaluation of long-term efficacy and

toxicity profiles for targeted therapies is imperative.

Furthermore, molecular stratification-guided personalized treatment

paradigms require validation through large-scale clinical trials.

Future investigations should prioritize novel biomarker discovery,

optimization of combination therapies and multi-omics exploration

of TME dynamics in disease progression, ultimately aiming to

enhance patient survival outcomes and quality of life.

Not applicable.

The present review was supported by grants from the Natural

Science Foundation of Shandong Province China (grant no.

ZR2023MA069), the Medical and Health Technology Development Project

of Shandong Province China (grant no. 202202050602), the Shandong

Project for Talents Introduction and development on Youth

Innovation Team of Higher Education, the Graduate Student Research

Grant from Shandong Second Medical University, Jiangyin Outstanding

Young Health Talents Project (grant no. JYOYT202310) and The Fourth

Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University 2024 Subjects

(grant no. 2024YJKT15).

Not applicable.

ZL, NW, XL and HX collected related literature and

drafted the manuscript. ZD, YL, YX, YS, TF and GW participated in

the design of the review and draft of the manuscript. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wan Y, Li G, Cui G, Duan S and Chang S:

Reprogramming of thyroid cancer metabolism: From mechanism to

therapeutic strategy. Mol Cancer. 24:7432025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Myung SK, Lee CW, Lee J, Kim J and Kim HS:

Risk factors for thyroid cancer: A hospital-based case-control

study in Korean adults. Cancer Res Treat. 49:70–78. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Li M, Li Q, Zou C, Huang Q and Chen Y:

Application and recent advances in conventional biomarkers for the

prognosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Front Oncol.

15:15989342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Badulescu CI, Piciu D, Apostu D, Badan M

and Piciu A: Follicular thyroid carcinoma-clinical and diagnostic

findings in a 20-year follow up study. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar).

16:170–177. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Huai JX, Wang F, Zhang WH, Lou Y, Wang GX,

Huang LJ, Sun J and Zhou XQ: Unveiling new chapters in medullary

thyroid carcinoma therapy: Advances in molecular genetics and

targeted treatment strategies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

15:14848152024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cleere EF, Prunty S and O'Neill JP:

Anaplastic thyroid cancer: Improved understanding of what remains a

deadly disease. Surgeon. 22:e48–e53. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Singarayer R, Mete O, Perrier L, Thabane

L, Asa SL, Van Uum S, Ezzat S, Goldstein DP and Sawka AM: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance

of BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry in thyroid histopathology.