Introduction

Immunization via vaccination not only prevents the

spread of infectious diseases in children and adults, but also

provides lifelong protection against certain diseases (1). However, whether the use of

chemotherapeutic drugs reduces vaccine efficacy remains

unclear.

Chemotherapeutic drugs kill hematopoietic cells in

the bone marrow, which can cause side-effects such as neutropenia,

erythropenia and thrombocytopenia. Due to changes in the immune

system, patients with cancer are at a higher risk of becoming

infected with pathogens than the general population, and infections

in these patients often lead to excessive morbidity and mortality

rates (2). This increased risk may

be related to a variety of causes, including cancer, chemotherapy

and poor nutrition. Although traditional chemotherapy has long been

recognized as an effective anticancer treatment, its potentially

severe side-effects are also widely recognized, including the

marked impairment of immune function (3). In patients treated with platinum-based

drugs, such as epirubicin, doxorubicin, paclitaxel and

cyclophosphamide chemotherapeutic regimens, the absolute numbers of

B-cell subsets significantly decrease between 2 and 12 weeks of

treatment (4). By contrast,

treatment with methotrexate at various doses for 6 weeks has been

shown to result in a decrease in B-cell numbers (5).

B-cells play a key role in adaptive immune

responses. These cells are activated in the germinal centers of

secondary lymphoid organs to form long-lived memory B-cells, which

differentiate into plasma cells following antigen stimulation and

produce high-affinity antibodies. The ‘Clinical Practice Guidelines

for Vaccination of Immunocompromised Hosts’ issued by the

Infectious Diseases Society of America considers that live

attenuated vaccines should be administered at least 4 weeks prior

to the start of any immunosuppressive treatment (6). In the case that radiotherapy or

chemotherapy are performed, vaccination should be terminated due to

concerns that live vaccines may cause infection (7). The present study reports the case of a

patient who was likely naturally infected with hepatitis B virus

(HBV) during chemotherapy, who recovered spontaneously and

developed high levels of anti-hepatitis Bs (anti-HBs).

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the disease that

the patient was originally treated for, is a malignant disease that

originates from B- or T-lymphocytes that proliferate abnormally in

the bone marrow. ALL can also invade tissues outside the bone

marrow (such as meninges, lymph nodes and peripheral blood)

(8). The treatment of ALL usually

includes four stages: i) Induction therapy; ii) consolidation

therapy; iii) enhancement therapy; and iv) targeted therapy to

prevent the relapse of central nervous system leukemia (9). During treatment, patients receive

different chemotherapeutic drugs, such as vincristine, cytarabine,

mercaptopurine, doxorubicin, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide and

L-asparaginase (10).

Case report

The patient in the present study was a 49-year-old

woman as of 2024. The vaccination history of the patient was

unknown, and the patient began to feel weak in January 2021,

accompanied by subcostal and lumbar pain, but did not pay attention

to it. The patient received treatment at the Chifeng Municipal

Hospital (Chifeng, China). The patient is a woman who was admitted

to the hospital for examination in March 2021 and was 46 years old

at the time. A peripheral blood examination in March, 2021,

revealed the following: i) A total white blood cell (WBC) count of

56.84×109/l (reference interval: 4-10×109/l);

ii) a lymphocyte ratio (L%) of 87.7% (reference interval: 20-40%)

and a neutrophil ratio (N%) of 6.95% (reference interval: 50-70%);

iii) a total red blood cell (RBC) count of 2.47×1012/l

(reference interval: 3.5-5.0×1012/l) and a hemoglobin

(Hb) level of 75 g/l (reference interval: 110-150 g/l); and iv) a

platelet (PLT) count of 20×109/l (reference interval:

100-300×109/l). Blood test results revealed that

primitive cells accounted for 84% of the cells (reference interval:

0%). The morphological description was that a large number of

primitive cells were observed, mature RBCs were of different sizes,

no nucleated RBCs or RBC inclusion bodies were observed and the

PLTs were relatively few. The bone marrow morphology report was

grade 1-2 myeloproliferation, mainly the abnormal proliferation of

lymphoid system cells, mature RBCs of different sizes and primitive

lymphocytes of the lymphocyte system accounting for 95%. The

primitive lymphocytes in the bone marrow smear are of different

sizes, with more nuclear chromatin, visible nucleoli, less serous

fluid, blue color, no granules, larger nuclei, and darker cytoplasm

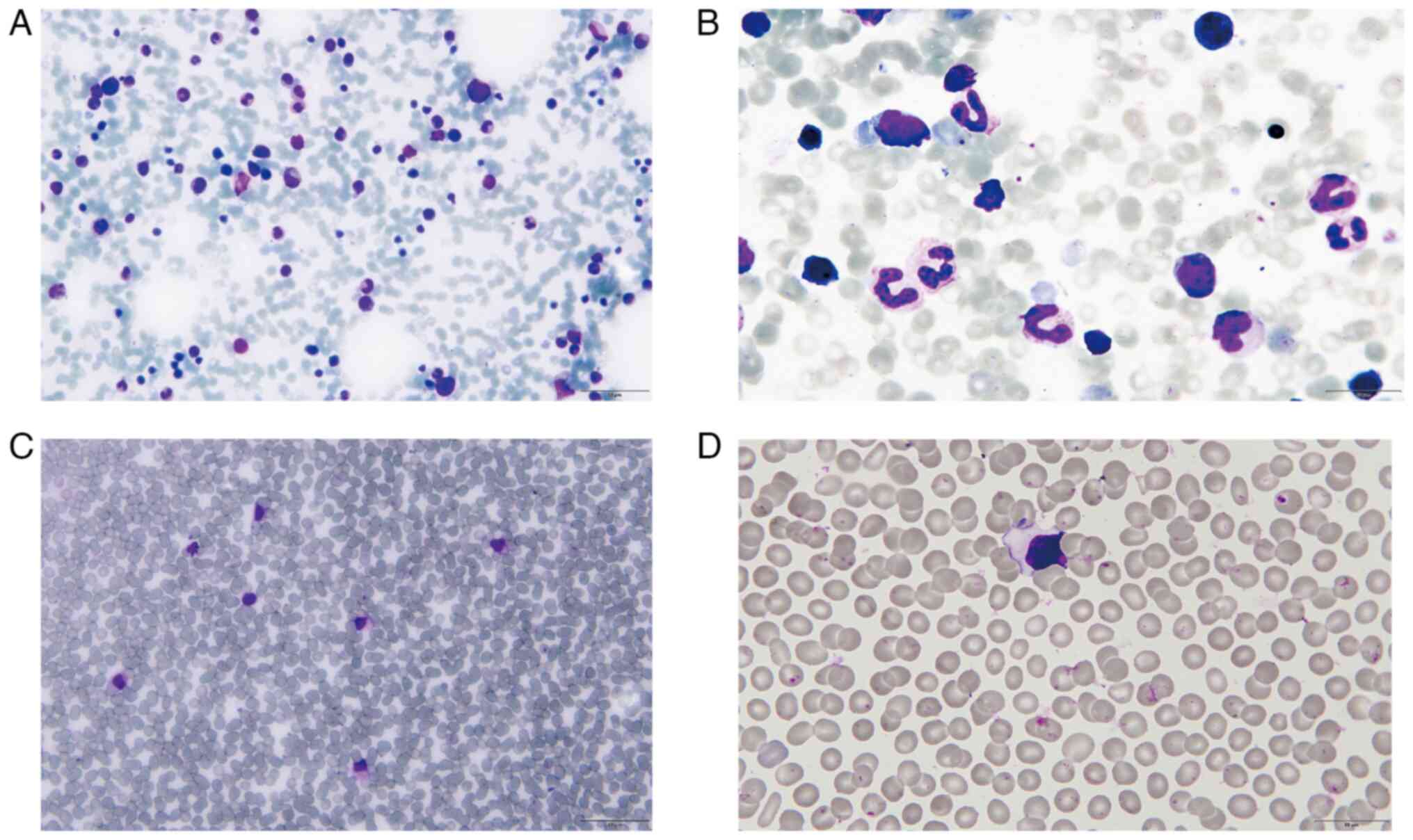

(Fig. 1A and B). Primitive

lymphocytes were also found in the peripheral blood (Fig. 1C and D). The diagnosis of ALL was

made. Immunophenotyping revealed that immature cells accounted for

91.6% of all cells expressing CD19, CD38, CD43, CD58, CD79a and

HLA-DR (human leukocyte antigen DR α chain precursor); some cells

expressed CD123, CD81, CD24, CD15, glial antigen 2 and terminal

deoxynucleotidyl transferase; there was no expression of CD45, CD5,

CD10, CD7, CD56, CD117, CD34, CD33, CD65, CD13, CD66c, CD22, CD20,

c/mκ and c/mλ. The IKAROS family zinc finger 1 mutation status was

positive.

In March 2021, the patient received 1.4

mg/m2 of vincristine, 40 mg/m2 of doxorubicin

and 1.4 mg/m2 of prednisone based on the body surface

area (m2). The aforementioned medication is called VDP

chemotherapy regimen. Bone marrow morphology analysis suggested

that the patient achieved morphological remission after 15 days of

VDP chemotherapy regimen. The day after the first administration of

VDP, the test result of HBsAg was <0.05 IU/ml (negative). One

intramuscular injection of 3,750 IU pegaspargase was given in April

2021. A further 13 days later, the patient received methotrexate

(MTX) chemotherapy at a dose of 1 g/m2 (body surface area), with a

total dose of 1.6 g. After 24 h, the MTX concentration in the blood

was 0.086 µmol/l. In May 2021, the quantitative result of HBsAg was

<0.05 IU/ml (negative). A cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and

methotrexate (CAM) chemotherapy program was administered in June

2021. In July 2021, the patient was treated once with daunorubicin

(total dose 30 mg) and cytarabine (total dose 7.2 mg).

Subsequently, 10 days later, the quantitative result of HBsAg was

<0.05 IU/ml (negative). Subsequently, 18 days later,

chemotherapy with 1.4 mg/m2 vinblastine, 40

mg/m2 daunorubicin, 800 mg/m2

cyclophosphamide and 40 mg/m2 dexamethasone (VDCD) was

administered. In August 2021, a single intramuscular injection of

high-dose MTX (total dose 2.1 g) and 3,750 IU of pegaspargase was

administered. In September 2021, the quantitative result of HBsAg

was <0.05 IU/ml (negative). In October 2021, to create

conditions for donor stem cell implantation, the patient received

0.8 mg/kg busulfan and 60 mg/kg cyclophosphamide (BUCY) regimen for

pre-autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

conditioning. Hematopoietic stem cells were transfused 7 days after

the BUCY regimen was administered. In February 2022, the patient

was treated once with a regimen of 1.4 mg/m2 vindesine,

40 mg/m2 daunorubicin, 800 mg/m2

cyclophosphamide and 40 mg/m2 dexamethasone (VICP), and

3,750 IU of pegaspargase intramuscularly. for consolidation

chemotherapy. Subsequently, 10 days later, the γ-glutamyl

transferase (GGT) test result was 68 IU/l (reference interval:

<60 U/l) which indicated a marked increase.

For possible potential blood transfusion treatment,

relevant infectious markers are tested before blood transfusion.

Subsequently, 7 days later, the HBsAg quantitative level was

accidentally detected and was 0.19 IU/ml (positive) and was

followed by a peripheral blood HBV nucleic acid test; the results

revealed that no amplification occurred. In March 2022, the HBsAg

quantitative result was 12.8 IU/ml (positive); however, the

cisplatin, oxaliplatin, doxorubicin, etoposide and tegafur regimen

consolidation chemotherapy was still administered the following

day. In April 2022, the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (reference

interval: <35 U/l) levels began to increase slightly, with a

test result of 41 IU/l, and the GGT level was 104 IU/l. In April

2022, the possibility of hepatitis B virus infection began to be

considered due to a notable increase in transaminase levels [ALT,

1,334 IU/l; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 1,334 IU/l; and GGT,

198 IU/l] (Table I). The patient

developed jaundice and received hepatoprotective treatment with

100-200 mg magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate and 1.8-2.4 g glutathione

daily for 3 weeks. Ursodeoxycholic acid and adenosine blue butane

sulfonate (the dosage and duration of treatment are unknown) were

used for treatment simultaneously, and gradual improvements were

observed.

| Table I.Determination of biochemical substance

content in peripheral blood. |

Table I.

Determination of biochemical substance

content in peripheral blood.

|

| Days post

admission |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Biomarker name | 325 | 384 | 405 | 411 | 483 | Unit | Reference

interval |

|---|

| TP | 53.00 | 57.00 | 46.00 | 61.00 | 63.00 | g/l | 65.00-85.00 |

| ALB | 36.00 | 42.00 | 29.00 | 36.00 | 41.00 | g/l | 40.00-55.00 |

| GLO | 17.00 | 15.00 | 17.00 | 25.00 | 21.00 | g/l | 20.00-40.00 |

| A/G | 2.12 | 2.80 | 1.71 | 1.44 | 1.88 | - | 1.20-2.40 |

| PREA | 210.00 | 330.00 | 40.00 | 80.00 | 170.00 | mg/l | 180.00-350.00 |

| AST | 15.00 | 21.00 | 916.00 | 289.00 | 18.00 | IU/l | 13.00-35.00 |

| ALT | 13.00 | 41.00 | 1,334.00 | 259.00 | 12.00 | IU/l | 7.00-40.00 |

| AST/ALT | 1.15 | 0.51 | 0.69 | 1.12 | 1.53 | - | 0.25-4.4 |

| ALP | 119.00 | 93.00 | 477.00 | 230.00 | 86.00 | IU/l | 35.00-100.00 |

| GGT | 74.00 | 104.00 | 198.00 | 75.00 | 88.00 | IU/l | 7.00-45.00 |

| ADA | 10.00 | 9.00 | 138.00 | 210.00 | 6.00 | U/l | 1.00-20.00 |

VD (vincristine 1.4 mg/m2; daunorubicin

30-40 mg/m2) treatment regimen treatmentwas continued in

July 2022. In August 2022, in order to observe whether the patient

had liver damage, liver function-related biomarkers were tested,

and the results were as follows: ALT, 13.8 IU/l; AST, 17.7 IU/l;

GGT, 67 IU/l. Quantitative analysis of blood samples with hepatitis

B infection indicators on the second day showed that the HBsAg

level had decreased to <0.05 (negative) and the anti-HBs content

was 982 IU/l (Table II). The first

day of chemotherapy in March 2021, was considered as

hospitalization day 0, and some of the collected clinical test data

were counted by day to observe the results more intuitively. On day

347, HbSAg was first found to be positive and became negative on

day 524. The anti-HBs level significantly increased on day 524

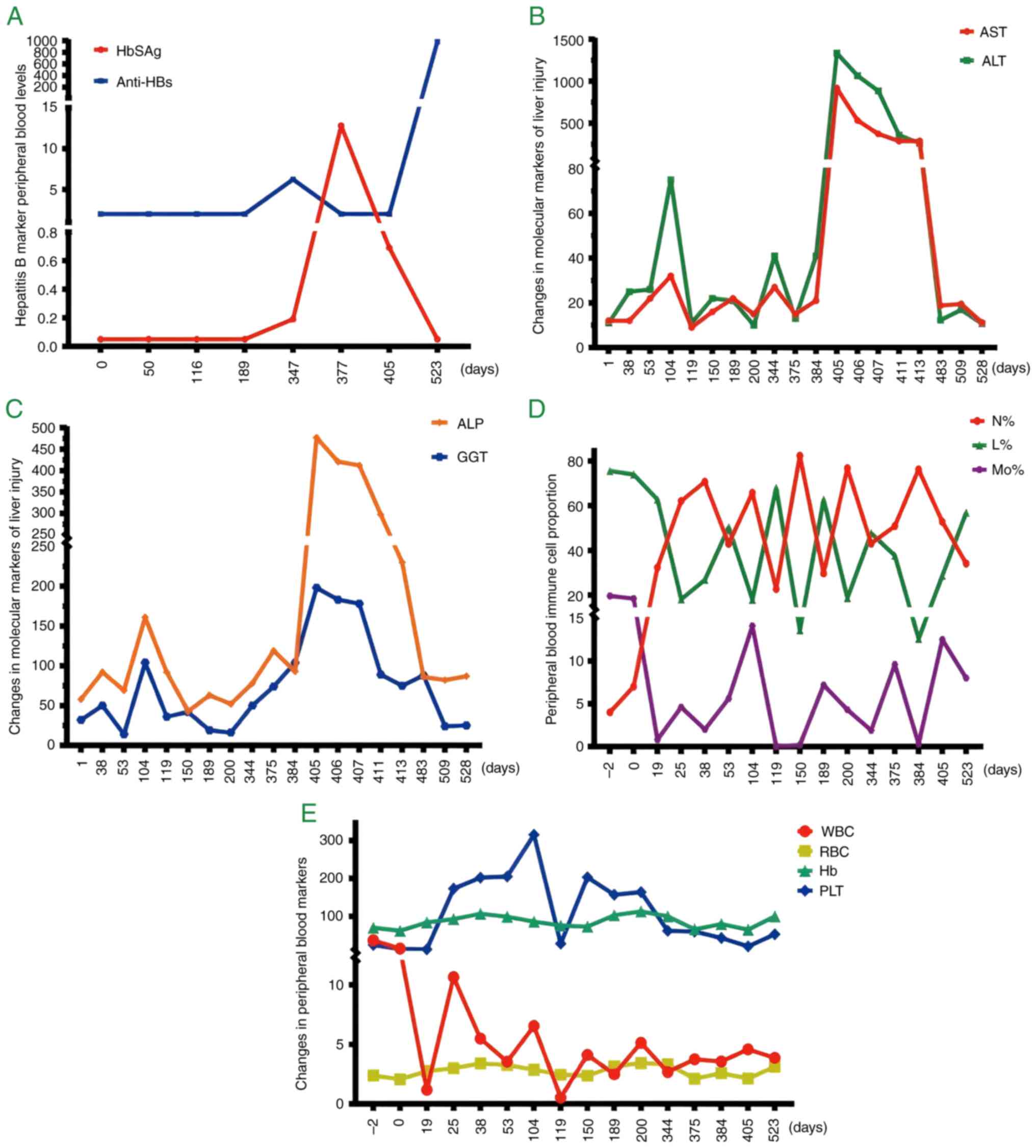

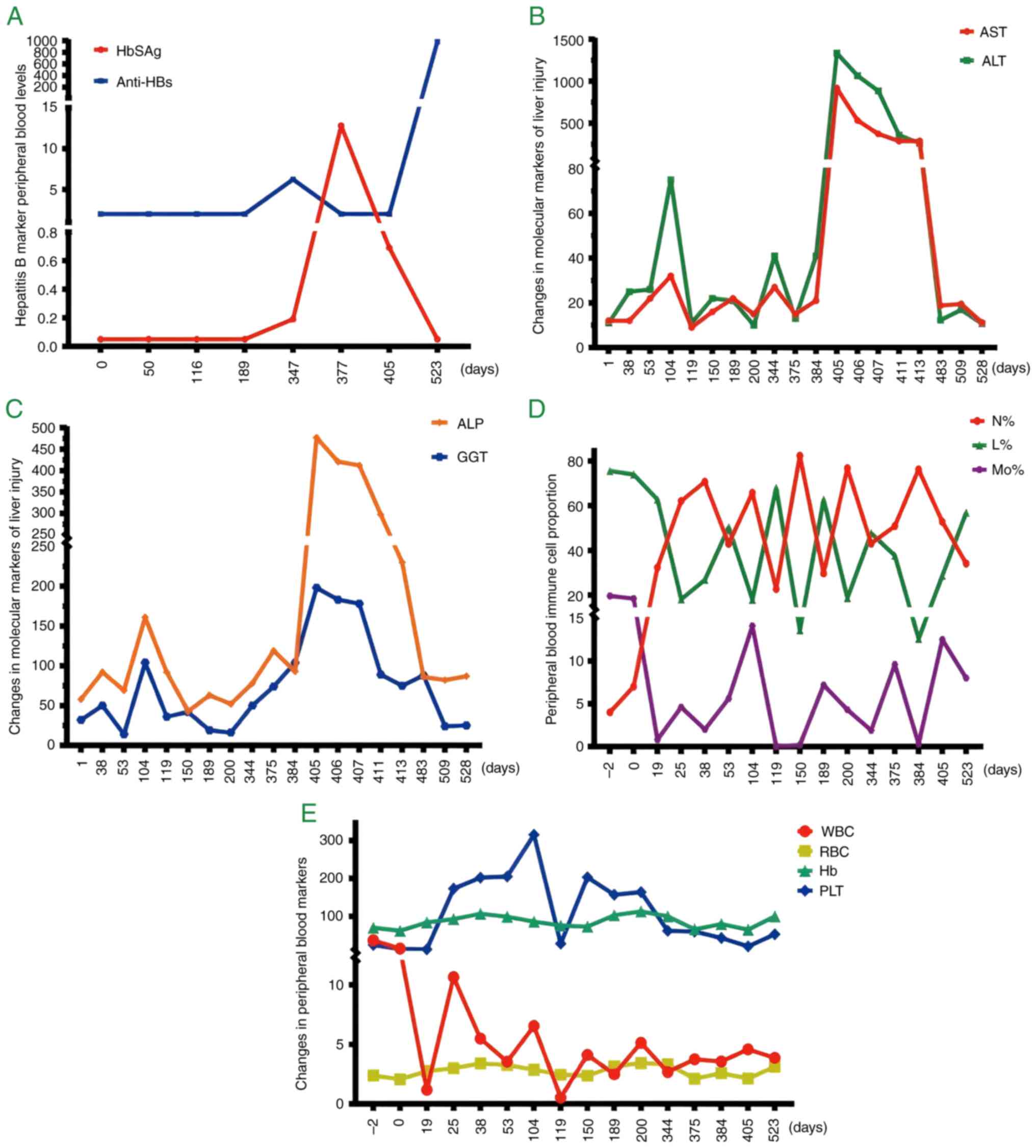

(Fig. 2A and Table SI). The activities of ALT and AST

in peripheral serum can reflect the degree of liver damage, which

peaked on day 405 and then gradually decreased (Fig. 2B and Table SII). The other two indicators of

liver function, ALP and GGT, reached their highest levels on day

405 (Fig. 2C and Table SII). Peripheral blood indices (WBC,

N%, L%, Mo%, RBC, Hb and PLT) revealed irregular ‘wave-like’

changes (Fig. 2D and E; Table SIII). The disease occurrence

timeline is presented in Table

III.

| Figure 2.Changes in trends in peripheral

blood-related clinical diagnostic markers. (A) Detection of

hepatitis B markers HBsAg (IU/ml) and anti-Hbs (IU/l). (B)

Detection of ALT and AST levels (unit, IU/l). (C) Detection of ALP

and GGT levels (unit, IU/l). (D) Proportion of major immune cells;

(E) WBC (109/l); RBC (1012/l); Hb (g/l); PLT

(109/l) content determination. HBsAg, Hepatitis B

surface antigen; anti-Hbs, anti-hepatitis B surface antibodies;

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase;

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; N,

neutrophils; L, lymphocytes; Mo, monocytes; WBC, white blood cell;

RBC, red blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet. |

| Table II.Changes in peripheral blood

pathogenic diagnostic markers. |

Table II.

Changes in peripheral blood

pathogenic diagnostic markers.

|

| Days post

admission |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Marker | 189 | 189 | 377 | 524 | Unit | Reference

interval |

|---|

| HbSAg | <0.05 | 0.19 | 12.80 | <0.05 | IU/ml | Negative <0.05;

positive ≥0.05 |

| Anti-HBs | <2.00 | 6.25 | <2.00 | 982.00 | IU/l | Negative <10.0;

positive ≥10.0 |

| HBeAg | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.97 | 0.10 | COI | Negative <1.0;

positive ≥1.0 |

| HBeAb | 1.49 | 1.40 | 1.62 | 0.01 | COI | Negative >1.0;

positive ≤1.0 |

| Anti-HBc | 2.37 | 2.11 | 0.91 | 0.01 | COI | Negative >1.0;

positive ≤1.0 |

| Anti-HBcIgM | 0.090 | 0.063 | 0.089 | - | COI | Negative <1.0;

positive ≥1.0 |

| Table III.Timeline. |

Table III.

Timeline.

| Days post

admission | Patient notes |

|---|

| January 2021 | Fatigue and

subcostal and back pain began to occur. |

| March 2021 | Acute lymphoblastic

leukemia was diagnosed and chemotherapy was administered using the

VDP regimen. HBsAg test result <0.05 IU/ml (negative). |

| September 2021 | HBsAg test result

<0.05 IU/ml (negative). |

| October 2021 | Hematopoietic stem

cell infusion |

| February 2022 | Treated with VICP

and pegaspargase. The quantitative result of HBsAg detected

unexpectedly was 0.19 IU/ml (positive). |

| March 2022 | Chemotherapy was

performed using the COATD regimen. The quantitative result of HBsAg

was 12.8 IU/ml (positive). |

| April 2022 | Peripheral plasma

ALT levels began to increase and soon reached 1334 IU/l. The same

changes occur in AST levels. Anti-HBc-IgM levels were significantly

increased in peripheral serum. |

| July 2022 | ALT and AST levels

in peripheral plasma decreased to within the reference range. Use

VD regimen for treatment. |

| August 2022 | The HBsAg

quantitative result became <0.05 (negative), and the Anti-HBs

content was 982 IU/l. |

Discussion

The present study reports the case of an adult

patient with ALL who may have been infected with HBV during

chemotherapy. The patient subsequently produced corresponding

antibodies and successfully achieved clinical self-recovery.

The average incubation period of HBV infection is

60-90 days (11). Infants, children

<5 years of age and immunosuppressed adults usually have no

obvious clinical symptoms in the case of infection with HBV. In

adults with normal immune function, ~95% of infections will be

rapidly cleared by the immune system of the body following viral

infection (12). Immunosuppressed

patients (such as those undergoing hemodialysis and those infected

with human immunodeficiency virus) may develop chronic infection

from acute infection. Currently, there is no specific treatment

available to completely eliminate HBV from the body (13). HBsAg positivity indicates HBV

infection. In the case of an acute HBV infection, anti-HBc (IgM and

IgG subtypes) in peripheral blood can be detected 1-2 weeks later

than HBsAg (14). After a healthy

adult is infected with HBV, HBsAg usually disappears within 3-4

months and anti-HBs appear. The presence of anti-HBs usually

indicates immunity to HBV infection (15). Occult HBV infection refers to

patients who test negative for HBsAg in their peripheral blood, but

there is replication-competent viral DNA in their liver and HBV DNA

is undetectable in their serum, which poses a challenge to the

study of HBV (16). In the present

study, the use of chemotherapy did not affect the production of

anti-HBs, although there was no evidence of an occult HBV

infection. No information on the disease history of HBV in family

members was obtained from medical records of the patient.

B-cells are generally known to produce secretory

antibodies during HBV infection and are a key component of the

adaptive immune response of the body (17). It is generally believed that the use

of chemotherapeutic drugs to treat tumors will have the side-effect

of suppressing bone marrow hematopoiesis, leading to a decrease in

the number of immune cells, such as B-lymphocytes and a decrease in

the ability of B-lymphocytes to respond to immune responses, such

as against viruses (18). Notably,

there is limited scientific knowledge available as to whether

chemotherapeutic drugs will affect the function of lymphoid tissue

and cell subsets, and whether they will have long-term effects on

the cellular and humoral immune responses of the body. The main

drugs used in patients with ALL in the maintenance phase are

6-mercaptopurine and MTX, which can reduce the risk of relapse;

however, they also have potentially severe toxic effects, with bone

marrow suppression being the most common side-effect (19). Therefore, it can be taken for

granted that chemotherapeutic drugs have significant adverse

effects on the immune system.

It has long been recognized that chemotherapeutic

agents can treat immune diseases. For example, the inactive

chemotherapeutic agent, cyclophosphamide, undergoes complex

metabolism in the liver to produce cytotoxic metabolites (20). Decades ago, the immunomodulatory

effects of cyclophosphamide were discovered in animal models, and

its mechanism of action is through the reduction of cell numbers

(21). In addition,

chemotherapeutic agents can deplete cells known as regulatory

T-lymphocytes (Tregs), thereby promoting local antitumor immune

responses. There has been renewed interest in the use of

cyclophosphamide to deplete human Tregs (22). As Tregs have low levels of

intracellular ATP and glutathione, they are considered to be more

susceptible to the toxic effects of cyclophosphamide than other

T-cells (23). When high-dose

corticosteroids are combined with cyclophosphamide to treat

severely active lupus nephritis, it can preferentially eliminate

naive B cells (24). Notably,

cyclophosphamide has no significant effect on class-switched memory

B cells, as these cells are normally dormant and do not proliferate

(25). Additionally,

chemotherapeutic drugs, including cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin,

methotrexate, mitomycin C, paclitaxel and vincristine, can improve

the function of antigen-presenting cells and increase the antitumor

effect of immune cells at low doses (26). Paclitaxel can also directly affect

the maturation of dendritic cells (27). Paclitaxel displays

lipopolysaccharide-mimicking activity in mice, activates TLR4, and

enhances DC activation and cytokine biosynthesis (28).

The majority of vaccination strategies for patients

with cancer involve vaccines for influenza, pneumococcal infection,

hepatitis B or recurrent herpes zoster. Experience suggests that

patients with cancer, or immunocompromised or immunosuppressed

patients may require a greater number of vaccine doses and more

vaccinations than immunocompetent individuals (29). A previous study of a recombinant

herpes zoster vaccine in patients with cancer demonstrated that the

overall immune response differed when the first dose of the vaccine

was administered prior to chemotherapy compared with when the first

dose was administered during chemotherapy (30). However, another study on a

recombinant subunit herpes zoster vaccine found that only 15% of

patients with hematological malignancies had a detectable

serological response (31).

Patients with cancer are more likely to have an

immune response following vaccination for coronavirus disease-19

than non-cancer patients. As previously demonstrated, after the

third dose of the vaccine in patients with solid tumors, the

proportion of patients with neutralization to the Omicron variant

increased from 47.8 to 88.9% (32).

It has also been found that after two doses of the mRNA vaccine in

patients with non-small cell lung cancer, the neutralization

response to the Omicron variant was 79-fold lower than that of

individuals without cancer (33).

Neutralizing antibodies are rarely detected in patients with

hematological malignancies after two doses of the Omicron vaccine;

however, neutralizing antibodies are detected in ~50% of patients

after the third dose (34).

Therefore, limited knowledge is available as regards the impact of

chemotherapy on the immune system of patients with cancer,

particularly with regards to vaccination strategies in the context

of chemotherapy.

The present study revealed that a patient

accidentally infected with HBV continued to produce protective

antibodies against HBV despite taking chemotherapy drugs to reduce

the number of lymphocytes in their blood, ultimately achieving

clinical cure. This phenomenon highlights the complexity of the

human immune system. Further understanding of the immune system is

needed to potentially produce effective strategies to enhance

antibody production in patients with HBV after vaccination.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (grant no. 2021MS08060), Inner

Mongolia Medical University Joint Project (grant nos. YKD2021LH068

and YKD2022LH072) and the Public Hospital Research Joint Fund

Science and Technology Project (grant no. 2024GLLH0990).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

LW, FZ and JH wrote the manuscript. YH, FZ and JH

provided critical comments on the manuscript content and made

substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data. LW and

YH made substantial contributions to the conception and design of

the manuscript, identified the clinical cases, assessed the

clinical data, verified the case data and reviewed the manuscript.

DS and RY analyzed and interpreted the data. HN acquired the data.

LW and YH confirm the authenticity of all original data and take

responsibility for all aspects of the work, ensuring that any

questions regarding the accuracy or integrity of any part of the

work were appropriately investigated and resolved (according to

ICMJE regulations). All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript and unanimously agreed that the manuscript could

be published.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This case report (including images and related text)

was submitted and published in accordance with the COPE guidelines,

strictly following the Declaration of Helsinki and Chinese national

policies, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chifeng

Municipal Hospital (approval no. CK20250101, approved in January

2025).

Patient consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from the patient to

publish these details.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Principe DR, Kamath SD, Korc M and Munshi

HG: The immune modifying effects of chemotherapy and advances in

Chemo-immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 236:1081112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yusuf K, Sampath V and Umar S: Bacterial

infections and cancer: Exploring this association and its

implications for patients with cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 24:31102023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Terrones-Campos C, Ledergerber B, Specht

L, Vogelius IR, Helleberg M and Lundgren J: Risk of bacterial,

viral, and fungal infections in patients with solid malignant

tumors treated with curative intent radiation therapy. Adv Radiat

Oncol. 7:1009502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Goswami M, Prince G, Biancotto A, Moir S,

Kardava L, Santich BH, Cheung F, Kotliarov Y, Chen J, Shi R, et al:

Impaired B-cell immunity in patients with acute myeloid leukemia

after chemotherapy. J Transl Med. 15:1552017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zandvoort A, Lodewijk ME, Klok PA, Dammers

PM, Kroese FG and Timens W: Slow recovery of follicular B cells and

marginal zone B cells after chemotherapy: Implications for humoral

immunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 124:172–179. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Henderson DK, Dembry LM, Sifri CD, Palmore

TN, Dellinger EP, Yokoe DS, Grady C, Heller T, Weber D, Del Rio C,

et al: Management of healthcare personnel living with hepatitis B,

hepatitis C, or human immunodeficiency virus in US healthcare

institutions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 43:147–155. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS,

Englund JA, File TM, Fry AM, Gravenstein S, Hayden FG, Harper SA,

Hirshon JM, et al: Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious

diseases society of America: 2018 update on diagnosis, treatment,

chemoprophylaxis, and institutional break management of seasonal

influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 68:e1–e47. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lv M, Liu Y, Liu W, Xing Y and Zhang S:

Immunotherapy for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Recent

advances and future perspectives. Front Immunol. 13:9218942022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gavralidis A and Brunner AM: Novel

therapies for treating adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr

Hematol Malig Rep. 15:294–304. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sas V, Moisoiu V, Teodorescu P, Tranca S,

Pop L, Iluta S, Pasca S, Blag C, Man S, Roman A, et al: Approach to

the adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient. J Clin Med.

8:11752019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ghany MG, Feld JJ, Chang KM, Chan HLY, Lok

ASF, Visvanathan K and Janssen HLA: Serum alanine aminotransferase

flares in chronic hepatitis B infection: Good and bad. Lancet

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5:406–417. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang

KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr, Bzowej NH and Wong JB: Update

on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B:

AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 67:1560–1599. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang G and Duan Z: Guidelines for

prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J Clin Transl

Hepatol. 9:769–791. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Campos-Valdez M, Monroy-Ramírez HC,

Armendáriz-Borunda J and Sánchez-Orozco LV: Molecular mechanisms

during hepatitis B infection and the effects of the virus

variability. Viruses. 13:11672021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kramvis A, Chang KM, Dandri M, Farci P,

Glebe D, Hu J, Janssen HLA, Lau DTY, Penicaud C, Pollicino T, et

al: A roadmap for serum biomarkers for hepatitis B virus: Current

status and future outlook. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

19:727–745. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Saitta C, Pollicino T and Raimondo G:

Occult hepatitis B virus infection: An UPdate. Viruses.

14:15042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cai Y and Yin W: Multiple functions of B

cells in chronic HBV infection. Front Immunol. 11:5822922020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Heylmann D, Bauer M, Becker H, van Gool S,

Bacher N, Steinbrink K and Kaina B: Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory

T-cells are sensitive to Low-dose cyclophosphamide. PLoS One.

8:e833842013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Toksvang LN, Lee SHR, Yang JJ and

Schmiegelow K: Maintenance therapy for acute lymphoblastic

leukemia: Basic science and clinical translations. Leukemia.

36:1749–1758. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang H, Lu Y, Zhang Y, Dong J, Jiang S

and Tang Y: DHA-enriched phosphatidylserine ameliorates

cyclophosphamide-induced liver injury via regulating the gut-liver

axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 140:1128952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Khimani F, Ranspach P, Elmariah H, Kim J,

Whiting J, Nishihori T, Locke FL, Perez Perez A, Dean E, Mishra A,

et al: Increased infections and delayed CD4+ T cell but Faster B

cell immune reconstitution after Post-transplantation

cyclophosphamide compared to conventional GVHD prophylaxis in

allogeneic transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther. 27:940–948. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kondĕlková K, Vokurková D, Krejsek J,

Borská L, Fiala Z and Ctirad A: Regulatory T cells (TREG) and their

roles in immune system with respect to immunopathological

disorders. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 53:73–77. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Naicker SD, Feerick CL, Lynch K, Swan D,

McEllistrim C, Henderson R, Leonard NA, Treacy O, Natoni A, Rigalou

A, et al: Cyclophosphamide alters the tumor cell secretome to

potentiate the anti-myeloma activity of daratumumab through

augmentation of macrophage-mediated antibody dependent cellular

phagocytosis. Oncoimmunology. 10:18592632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Scurr M, Pembroke T, Bloom A, Roberts D,

Thomson A, Smart K, Bridgeman H, Adams R, Brewster A, Jones R, et

al: Low-dose cyclophosphamide induces antitumor T-cell responses,

which associate with survival in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 23:6771–6780. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhao L, Jiang Z, Jiang Y, Ma N, Wang K and

Zhang Y: Changes in immune cell frequencies after cyclophosphamide

or mycophenolate mofetil treatments in patients with systemic lupus

erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 31:951–959. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kaneno R, Shurin GV, Tourkova IL and

Shurin MR: Chemomodulation of human dendritic cell function by

antineoplastic agents at low non-cytotoxic concentrations. J Transl

Med. 7:582009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Byrd-Leifer CA, Block EF, Takeda K, Akira

S and Ding A: Role of MyD88 and TLR4 in LPS-mimetic activity of

Taxol. Eur J Immunol. 31:2448–2457. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

John J, Ismail M, Riley C, Askham J,

Morgan R, Melcher A and Pandha H: Differential effects of

paclitaxel on dendritic cell function. BMC Immunol. 11:142010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Noori M, Azizi S, Abbasi Varaki F,

Nejadghaderi SA and Bashash D: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of the immune response against the first and second

doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in adult patients with hematological

malignancies. Int Immunopharmacol. 110:1090462022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Rubio-Viqueira B, Jung KH, Rodriguez

Moreno JF, Grande E, Marrupe Gonzalez D, Lowndes S, Puente J,

Kristeleit H, Farrugia D, McNeil SA, et al: Immunogenicity and

safety of the adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine in patients

with solid tumors, vaccinated before or during chemotherapy: A

randomized trial. Cancer. 125:1301–1312. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pedrazzoli P, Lasagna A, Cassaniti I,

Ferrari A, Bergami F, Silvestris N, Sapuppo E, Di Maio M, Cinieri S

and Baldanti F: Vaccination for herpes zoster in patients with

solid tumors: A position paper on the behalf of the Associazione

Italiana di Oncologia Medica (AIOM). ESMO Open. 7:1005482022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wei Z, He J, Wang C, Bao J, Leng T and

Chen F: Importance of booster vaccination in the context of Omicron

waves. Front Immunol. 13:9779722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fendler A, de Vries EGE, Geurtsvan Kessel

CH, Haanen JB, Wörmann B, Turajlic S and von Lilienfeld-Toal M:

COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer: Immunogenicity,

efficacy, and safety. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 19:385–401. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhao L, Fu L, He Y, Li H, Song Y and Liu

S: Effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccination in patients

with malignant disease. Vaccines (Basel). 11:4862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|