Introduction

Breast cancer (BRCA) is one of the most prevalent

and challenging cancer types affecting women worldwide (1,2). BRCA

is characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal

cells within breast tissue, leading to tumorigenesis (3). Although the exact etiology of BRCA

remains elusive, several risk factors, including genetic mutations,

hormonal imbalances and environmental influences, have been

identified (4,5). Investigating the mechanisms underlying

BRCA is of paramount importance in clinical medicine, as it

facilitates the development of targeted therapies, early detection

techniques and preventive strategies, ultimately enhancing patient

outcomes and prognosis.

With advancements in bioinformatics tools and gene

sequencing technologies, extensive research has shed light on the

underlying mechanisms driving BRCA development and progression

(6,7). A key contributor is genetic

alterations, particularly mutations in genes such as BRCA1 and

BRCA2 (8,9). These mutations compromise the normal

function of tumor suppressor genes, enabling uncontrolled cell

division and growth (10).

Additionally, the dysregulation of hormonal signaling pathways,

including estrogen and progesterone receptors, has been implicated

in the pathogenesis of hormone receptor-positive BRCA (11,12).

Thus, a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying BRCA may

offer valuable insights for early detection and prevention.

In the present study, an integrated analysis of BRCA

samples utilizing bioinformatics databases and analytical

approaches was performed to identify clinically significant key

genes. Additionally, cell-based experiments were conducted to

explore the specific functions and underlying mechanisms of these

key genes in BRCA. The present study provides valuable insights

into the tumorigenesis of BRCA and contributes to the development

of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Identification of differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) from the GSE21422 and The Cancer Genome

Atlas (TCGA)-BRCA datasets

The GSE21422 dataset (GPL570 platform, expression

profiling by array) was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus

(ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and includes 5 healthy breast and 14 BRCA

samples (ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive ductal breast

carcinoma) (13). Gene expression

data from TCGA-BRCA cohort were downloaded from the UCSC Xena

Browser (https://xenabrowser.net/). Gene

expression RNA-seq data in HTSeq-FPKM format were obtained from

TCGA-BRCA dataset. TCGA-BRCA dataset encompasses all molecular

subtypes of BRCA, including the triple-negative BRCA (TNBC),

hormone receptor-positive and HER2-enriched subtypes. Using the

GEO2R tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/) and ‘limma’ R

package (version 3.52.4) in R software (version 4.2.2), DEGs were

analyzed on the basis of log2[fold change (FC)]>1 for

upregulation and <-1 for downregulation, with statistical

significance (P<0.05). The GSE21422-DEGs and TCGA-BRCA-DEGs were

combined and the overlapping genes were screened via a Venn

diagram, which were then uploaded to the Database for Annotation,

Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp) to conduct Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and Gene Ontology

[GO; including Cell Component (CC), Biological Process (BP) and

Molecular Function (MF)] analysis. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. To identify key

genes among the DEGs, a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

was constructed using the STRING database (string-db.org/) with a

minimum required interaction score of 0.4. The resulting network

was imported into Cytoscape software (version 3.9.1), and the

CytoHubba plugin was applied to analyze network topology. The

BottleNeck algorithm within CytoHubba was used to rank genes based

on their network importance.

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection

Operator (LASSO) regression model

LASSO analysis was performed via the ‘glmnet’

package in R software. This model was applied to the overlapping

genes identified in the aforementioned analysis. The coefficients

of the signature genes were determined at λmin, which

was obtained by examining the association between the partial

likelihood deviation and log(λ). The samples from TCGA-BRCA dataset

were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median

value (−0.0085) of the calculated risk scores derived from the

expression levels of the overlapping genes. A risk score model was

then designed to compare the survival status of patients with BRCA

and the differences in the expression of signature genes between

the two groups. Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curves for

progression-free survival (PFS) were generated using the ‘survival’

package. The hazard ratio (HR), confidence interval (CI) and log

rank P-value were calculated to compute the differences in survival

outcomes between the high-risk and low-risk groups. To assess the

prognostic value of the risk model, receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curves were established using the ‘timeROC’

package, specifically for the 1-, 3- and 5-year time points. The

predictive accuracy of the model was quantified by calculating the

area under the curve (AUC) values.

Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA)

GSCA is a computational method used to assess the

variation in gene set activity across different samples in gene

expression data. In the present study, the GSCA database

(https://guolab.wchscu.cn/GSCA/#/) was

used to perform gene mutation analysis on signature genes,

including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variations

(CNVs), variant types, variant classifications, variant

classification summaries and variants per sample.

Expression, ROC and KM survival

analyses

Expression, ROC and KM survival analyses were also

conducted to evaluate the individual clinical relevance of each

signature gene. Unlike the risk model-based analyses described

above, which assessed the combined prognostic value of the entire

gene signature using a composite risk score, these analyses focused

on the diagnostic and prognostic value of each gene independently.

Specifically, the signature gene expression levels in the TCGA-BRCA

tumor and normal groups were observed. ROC analysis was

subsequently used to evaluate the diagnostic value of the signature

genes in BRCA. ROC analysis was performed using the ‘pROC’ package.

The larger the AUC value, the greater the diagnostic value. KM

survival curves were constructed to visualize the differences in

survival outcomes. KM survival analysis was conducted using the

‘survminer’ package in R. The log-rank test was used to estimate

the significant difference between the groups, and HRs were

calculated to estimate the risk associated with the gene expression

levels. Finally, the overall survival (OS) probability of genes

with diagnostic value was evaluated.

Construction of the prognostic

nomogram

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

were performed on signature genes that showed significant

association with OS together with clinical factors, including age,

pT stage and pTNM stage, to identify the 5 candidate genes linked

to BRCA survival. These analyses were conducted via the

‘forestplot’ package, and prognostic genes with a significant

association (P<0.05) were identified. A prognostic nomogram

incorporating the significant prognostic variables was subsequently

designed via the ‘rms’ package. The nomogram aimed to predict the

1-, 3- and 5-year survival probabilities of patients with BRCA with

identified prognostic factors. Additionally, a calibration curve

was used to estimate the performance and accuracy of the survival

nomogram model.

Analysis of the correlation between

gene expression and clinical parameters in BRCA

The Human Protein Atlas (HPA; proteinatlas.org/) is

a comprehensive and publicly available resource that provides

information about the expression and localization of proteins in

various human tissues and cells (14). In the present study, the protein

expression of Rac/Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 6

(ARHGEF6) in BRCA was assessed. Data from the University of Alabama

at Birmingham Cancer Data Analysis Portal (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html) was used to

conduct clinical feature analysis on the basis of individual cancer

stage, age, nodal metastasis status and TP53 mutation status. The

Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database (cancerrxgene.org/)

was used to analyze the relationship between ARHGEF6 expression

levels and the IC50 of paclitaxel in BRCA. We collected

genes involved in apoptosis and performed single-sample gene set

enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) using the GSVA package (version 3.21)

in R with the method set to ‘ssgsea’. Finally, Spearman correlation

analysis was used to assess the relationship between gene

expression and pathway scores.

Cell lines

The BRCA cell lines, Hs578t (cat. no. QS-H157;

Keycell Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and MDA-MB-231 (cat. no.

BFN608008564; The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of the

Chinese Academy of Sciences), were subjected to short tandem repeat

analysis and mycoplasma testing. These cell lines were stored in

liquid nitrogen at −80°C and subsequently cultured in Roswell Park

Memorial Institute 1640 medium (cat. no. E600028; Sangon Biotech

Co., Ltd.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no.

C0235; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and

penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 60162ES76; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). For subsequent studies, the cells were

cultured at 37°C in a humidified environment with 5%

CO2.

Cell transfection

The ARHGEF6 overexpression plasmid

[pRP(Exp)-CMV>hARHGEF6; NM_004840.3] and a negative control

[pRP(Exp)-CMV>ORF_Stuffer) were constructed by VectorBuilder,

Inc. Lipofectamine 2000 (cat. no. 11668019; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for cell transfection according

to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 2 µg of plasmid was

transfected into cells cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator

with 5% CO2. The transfection mixture was incubated with

cells for 6 h at 37°C, after which the medium was replaced with

fresh complete medium. Subsequent experiments were performed 48 h

post-transfection.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

After cell transfection, total RNA was isolated from

cells with TRIzol reagent (cat. no. R0016; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), followed by RT of the RNA into complementary DNA

with a PrimeScript RT kit (cat. no. 04379012001; Roche Diagnostics)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was conducted

with a SYBR Green PCR Mix Kit (cat. no. 4344463; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The reaction conditions were as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec and

extension at 74°C for 30 sec. GAPDH served as the internal control.

The 2−ΔΔCq method was used to determine the relative

expression levels of the target genes (15). The primers used were as follows:

ARHGEF6 forward, 5′-TCCAGGAATGGTTGGAGCAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGCTGTCCGGTAGAGCTAAA-3′; BCL2 forward,

5′-AAAAATACAACATCACAGAGGAAGT-3′ and reverse,

5′-GTTTCCCCCTTGGCATGAGA-3′; caspase3 forward,

5′-TGAGGCGGTTGTAGAAGAGTTTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TTATTAACGAAAACCAGAGCGCC-3′; p53 forward,

5′-AAGTCTAGAGCCACCGTCCA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GACGCTAGGATCTGACTGCG-3′;

GAPDH forward, 5′-AATGGGCAGCCGTTAGGAAA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GCGCCCAATACGACCAAATC-3′.

Western blotting

Cell lysis was performed using RIPA lysis buffer

(cat. no. P0013; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and total

protein was extracted. Then, 12% sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (cat. no. P0690;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used to separate the

proteins (25 µg/lane), before the proteins were transferred to PVDF

membranes (cat. no. FFP24; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

The membranes were then blocked for 2 h at room temperature with 5%

non-fat milk. Primary antibodies were added to the membranes and

incubated overnight at 4°C. Antibodies were as follows:

anti-ARHGEF6 (1:1,000, ab184569, Abcam), anti-BCL2 (1:1,000,

ab182858, Abcam, UK), anti-p53 (1:1,000, ab32509, Abcam, UK),

anti-caspase-3 (1:1,000, ab32351, Abcam, UK), anti-c-caspase-3

(1:1,000, ab32042, Abcam, UK) and anti-GAPDH (1:3,000, ab9485,

Abcam, UK). Then the membranes were incubated with goat Anti-Rabbit

IgG H&L (HRP) (1:5,000, ab6721, Abcam, UK) for 4 h at room

temperature. GAPDH served as the internal control, and protein

expression was visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit

(cat. no. KGC4603; KeyGene).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured using Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8; cat. no. C0038; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

assay. After transfection for 48 h, the cells were seeded into

96-well plates at a density of 2×103 cells per well.

Then, 10 µl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well at various

time intervals (0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h) to assess the viability and

proliferation of the cells, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C.

A microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was then used to

measure the absorbance of the cells at 450 nm.

Cell invasion and migration

assays

For the invasion experiment, the transfected cells

(5×104) were plated in the upper chamber of a Transwell

insert covered with Matrigel (cat. no. 356234; BD Biosciences),

which had been incubated at 37°C for 1 h before cell seeding. The

cells were cultured in serum-free media in the upper chamber. The

lower chamber was filled with media containing 10% FBS. The cells

were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The invading cells were fixed with

4% paraformaldehyde (cat. no. P0099; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (cat.

no. C1006; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Randomly chosen

fields of view were used to study the cells under a microscope.

Same procedures were followed for the cell migration experiment,

except that Matrigel was not applied to the Transwell insert.

Flow cytometry

Transfected cells were harvested using trypsin (cat.

no. 40101ES25; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The cell

suspension was then centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at room

temperature to obtain a pellet. The pellet was subsequently

resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (cat. no. C0221A; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The resuspended cells were stained

with an Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium

iodide (PI) (cat. no. C1383L; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

staining kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Following incubation, the stained cells were analyzed by a flow

cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed with FlowJo software

(version 10.8.1; BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

All cellular experiments were performed in

triplicate, and data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0

software (Dotmatics). Comparisons between two groups were performed

using unpaired independent samples t-test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Identification and functional

enrichment analysis of overlapping DEGs

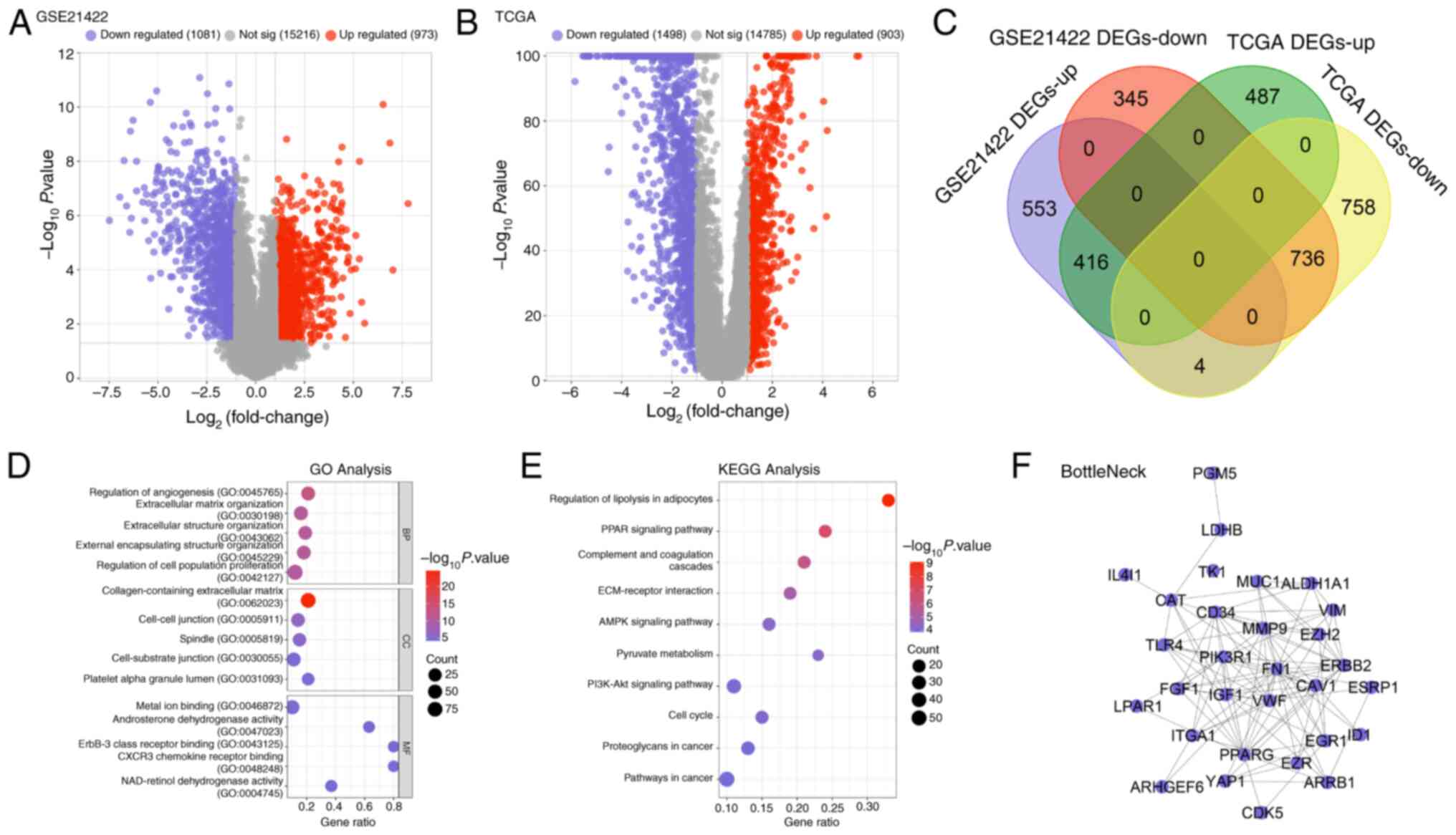

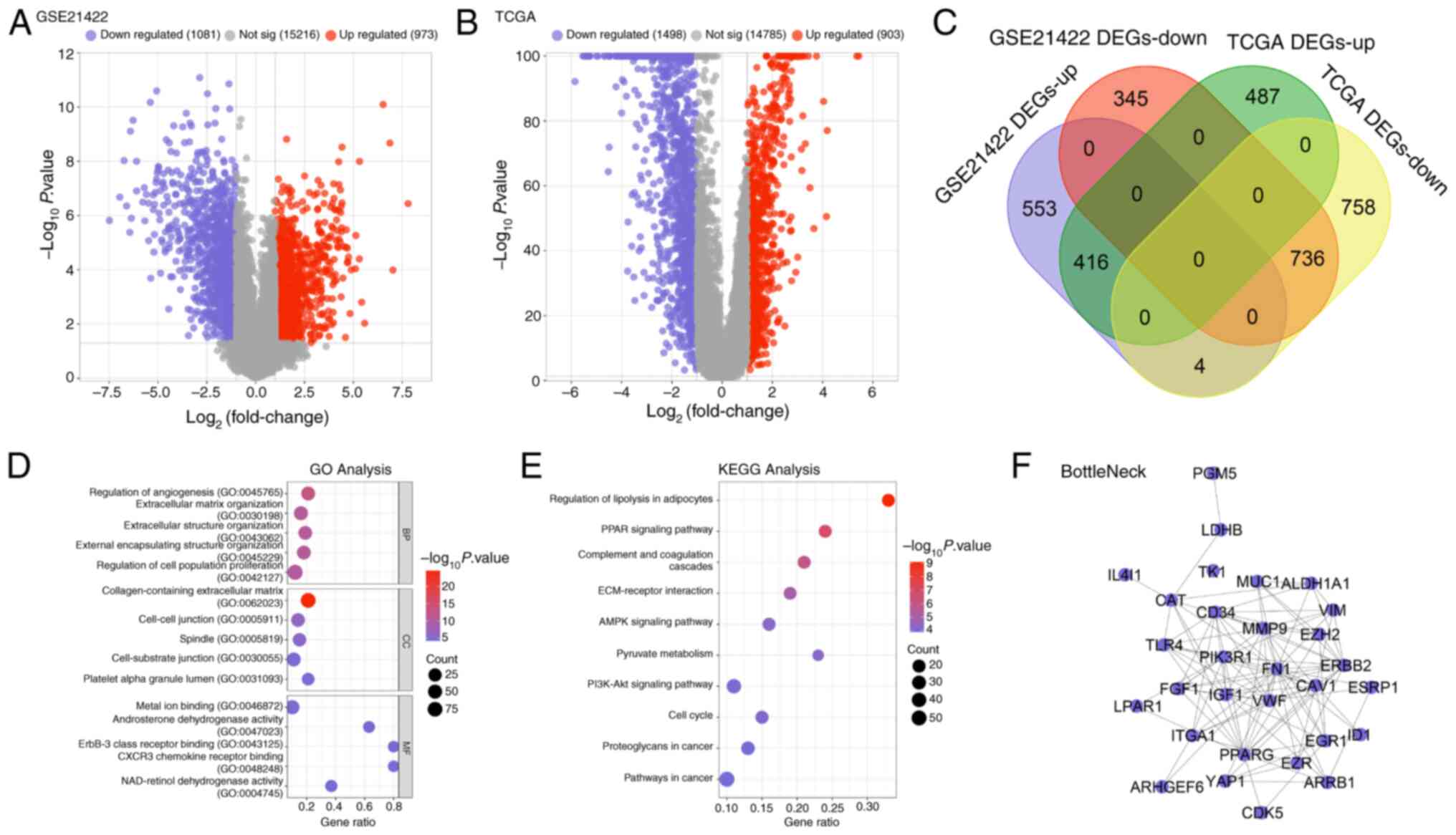

The overlapping DEGs were identified by integrating

data from the GSE21422 dataset and TCGA-BRCA cohort. Using the

GSE21422 dataset, 1,081 downregulated and 973 upregulated DEGs were

identified (Fig. 1A). From

TCGA-BRCA samples, 1,498 downregulated and 903 upregulated DEGs

were obtained (Fig. 1B). The

intersection of these datasets yielded overlapping DEGs (Fig. 1C). To explore the biological

significance of these overlapping DEGs, GO enrichment analysis was

performed. In the BP category, the overlapping DEGs were

significantly enriched in processes such as the ‘Regulation of

angiogenesis’, ‘External encapsulating structure organization’ and

‘Regulation of cell population proliferation’ (Fig. 1D). For CC, the genes were

predominantly associated with the ‘Collagen-containing

extracellular matrix’, ‘Cell-cell junction’ and ‘Spindle’ (Fig. 1D). In terms of MF, significant

enrichment was observed for ‘Metal ion binding’, ‘Androsterone

dehydrogenase activity’, ‘ErbB-3 class receptor binding’, ‘CXCR3

chemokine receptor binding’ and ‘NAD-retinol dehydrogenase

activity’ (Fig. 1D). KEGG pathway

analysis further revealed that the overlapping DEGs were involved

in several critical pathways, including those related to the

Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes, PPAR signaling pathway,

ECM-receptor interaction, AMPK signaling pathway and Pyruvate

metabolism (Fig. 1E). To identify

potential hub genes, a protein-protein interaction network was

constructed utilizing the BottleNeck algorithm, which pinpointed 30

key interactive genes (Fig.

1F).

| Figure 1.Overlapping DEGs were obtained from

GSE21422 and TCGA datasets. (A) DEGs in the GSE21422 dataset

includes 1,081 downregulated genes, 973 upregulated genes and

15,216 non-significant genes. (B) DEGs in TCGA dataset includes 903

upregulated genes, 1,498 downregulated genes and 14,785

non-significant genes. (C) The Venn diagram of overlapping DEGs

from the GSE21422 and TCGA datasets. Purple represents upregulated

GSE21422 DEGs, orange represents downregulated GSE21422 DEGs, green

represents upregulated TCGA DEGs and yellow represents

downregulated TCGA DEGs. (D) The enriched GO terms of overlapping

DEGs, including BP, CC and MF. (E) The enriched KEGG pathways of

the overlapping DEGs. (F) The protein-protein interaction network

of overlapping DEGs analyzed by BottleNeck algorithm, with 30

nodes. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; TCGA, The Cancer

Genome Atlas; GO, Gene Ontology; BP, Biological Process; CC, Cell

Component; MF, Molecular Function; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes. |

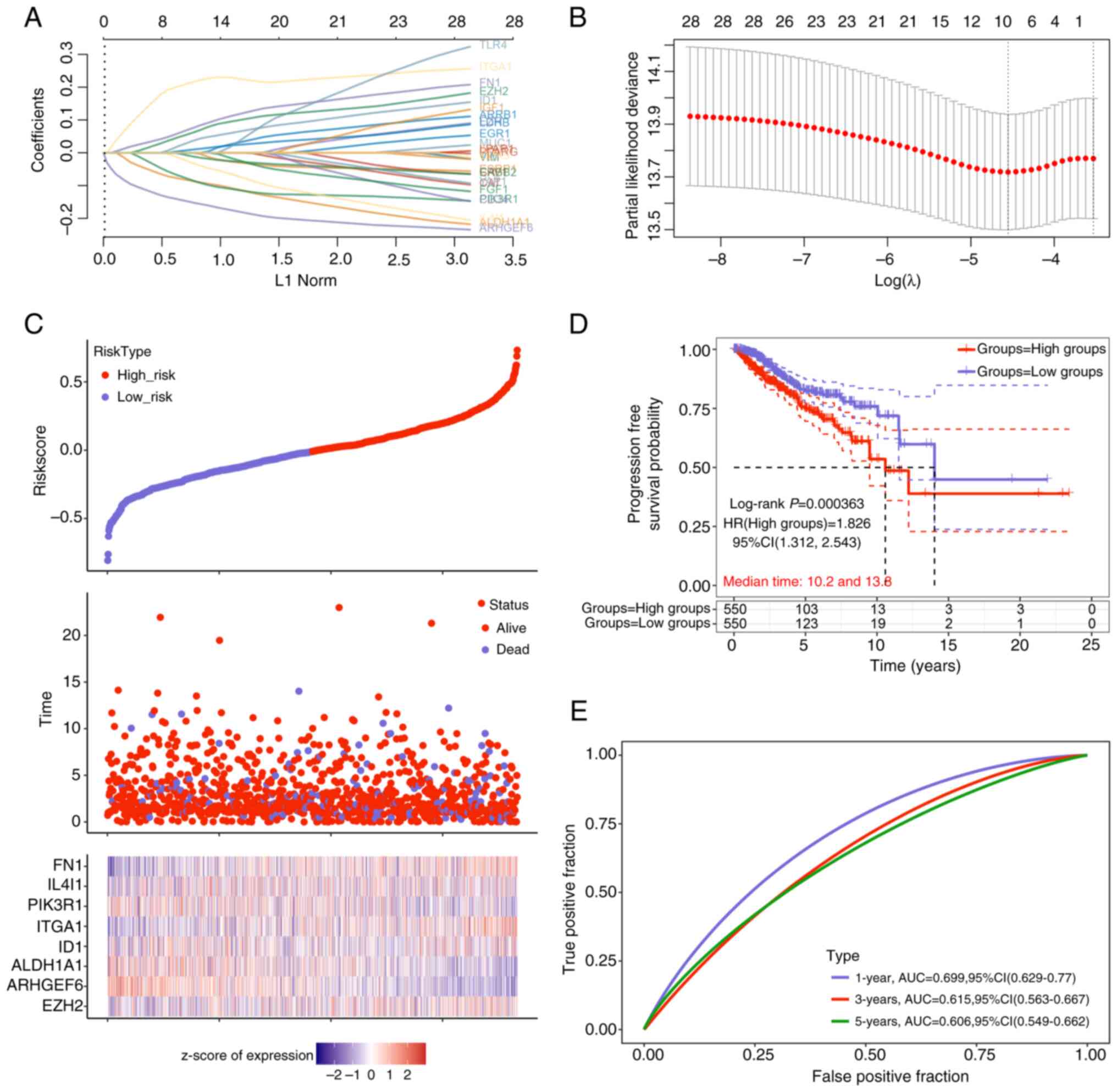

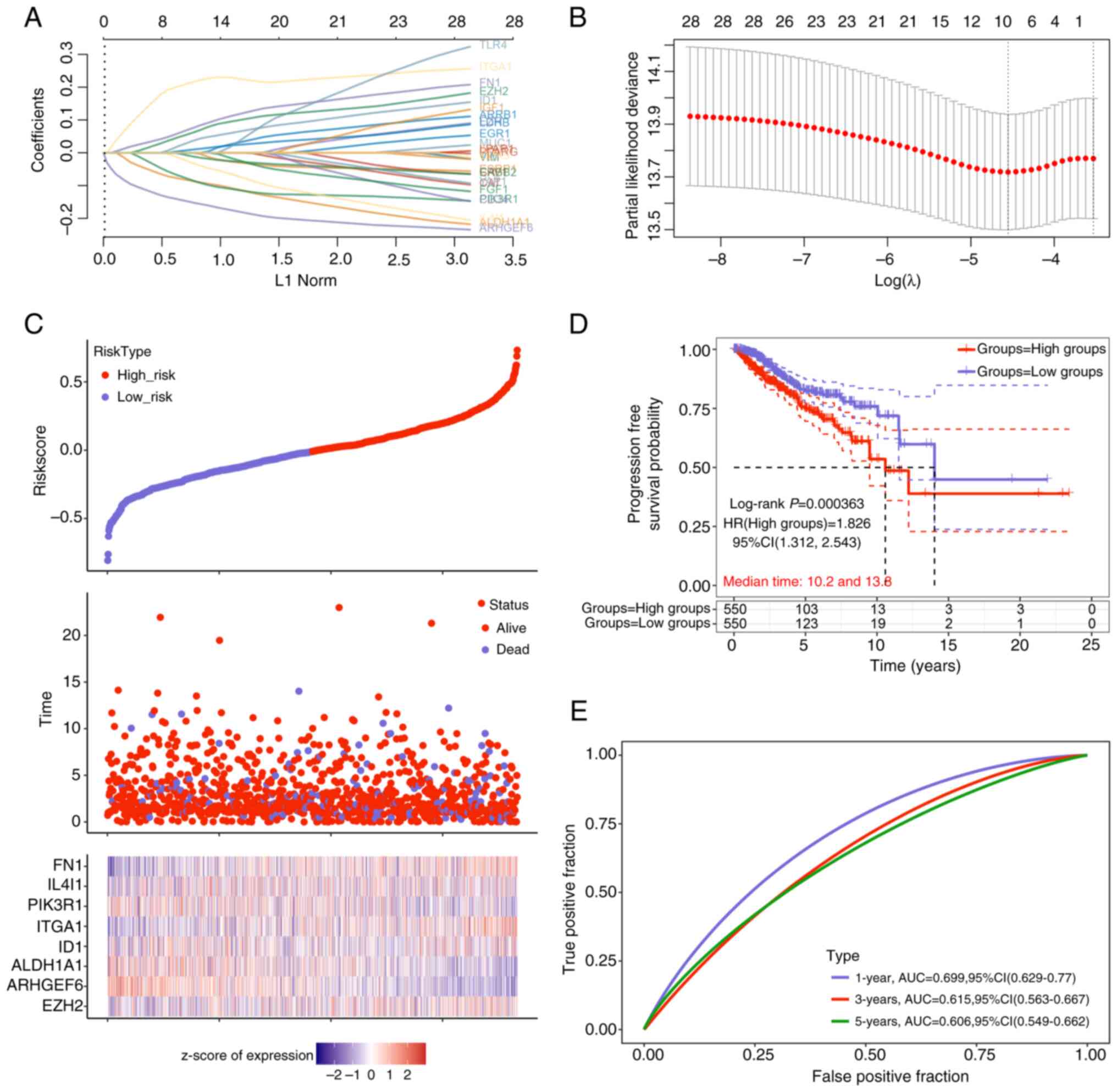

Identification of 8 prognostic

signature genes via the risk score model

Subsequent LASSO Cox regression analysis of the 30

previously identified interactive genes led to the selection of 8

prognostic signature genes on the basis of the λmin

value (Fig. 2A and B). The risk

model analysis (Fig. 2C)

demonstrated that patients in the high-risk group had a higher

mortality rate and a lower survival rate than did those in the

low-risk group. Notably, the expression levels of the 8 signature

genes, fibronectin (FN1), IL4I1, PIK3R1, integrin α1 (ITGA1),

inhibitor of DNA binding 1 (ID1), aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family

member A1 (ALDH1A1), ARHGEF6 and enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb

repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2), were significantly different

between the two groups. KM survival curve analysis for PFS revealed

that patients in the high-risk group had significantly poorer

prognoses (log-rank P=0.000363; 95% CI, 1.312-2.543). The

calculated HR between the groups was 1.826 (>1), underscoring

the utility of the risk model as an effective prognostic indicator

(Fig. 2D). Furthermore, ROC curve

analysis (Fig. 2E) indicated that

the risk model exhibited strong predictive performance (AUC

>0.6) for survival outcomes at 1, 3 and 5 years, with the

highest accuracy observed at the 1-year time point (AUC=0.699).

These results underscore the prognostic value of the identified

signature genes and the robustness of the developed risk model in

predicting survival outcomes for the studied population.

| Figure 2.Prognostic signature genes were

identified by the risk score model. (A) Detailed table shows the

feature gene selection corresponding to the λmin value.

Each row represents a feature gene, and the columns include the

gene name and its corresponding coefficient. (B) The LASSO

regression coefficient plot illustrates the selection of 8

signature genes out of the 30 interactive genes. The vertical axis

represents the coefficient magnitude, and the horizontal axis

represents log(λ) values, where λ is the regularization parameter.

The vertical line at λmin indicates the selection of the

feature genes. (C) Risk score (top), survival time (middle) and

signature gene expression (bottom) from the low-risk group to

high-risk group. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curve based on

progression-free survival reveals a significantly worse prognosis

in the high-risk group, indicating the prognostic risk model's

capability. (E) AUC values from the ROC curve analysis demonstrate

good predictive accuracy of the risk model for survival at 1, 3 and

5 years, with the highest prediction accuracy observed at the

1-year mark (AUC=0.699). LASSO, Least Absolute Shrinkage and

Selection Operator; AUC, area under the curve; HR, hazard ratio;

CI, confidence interval. |

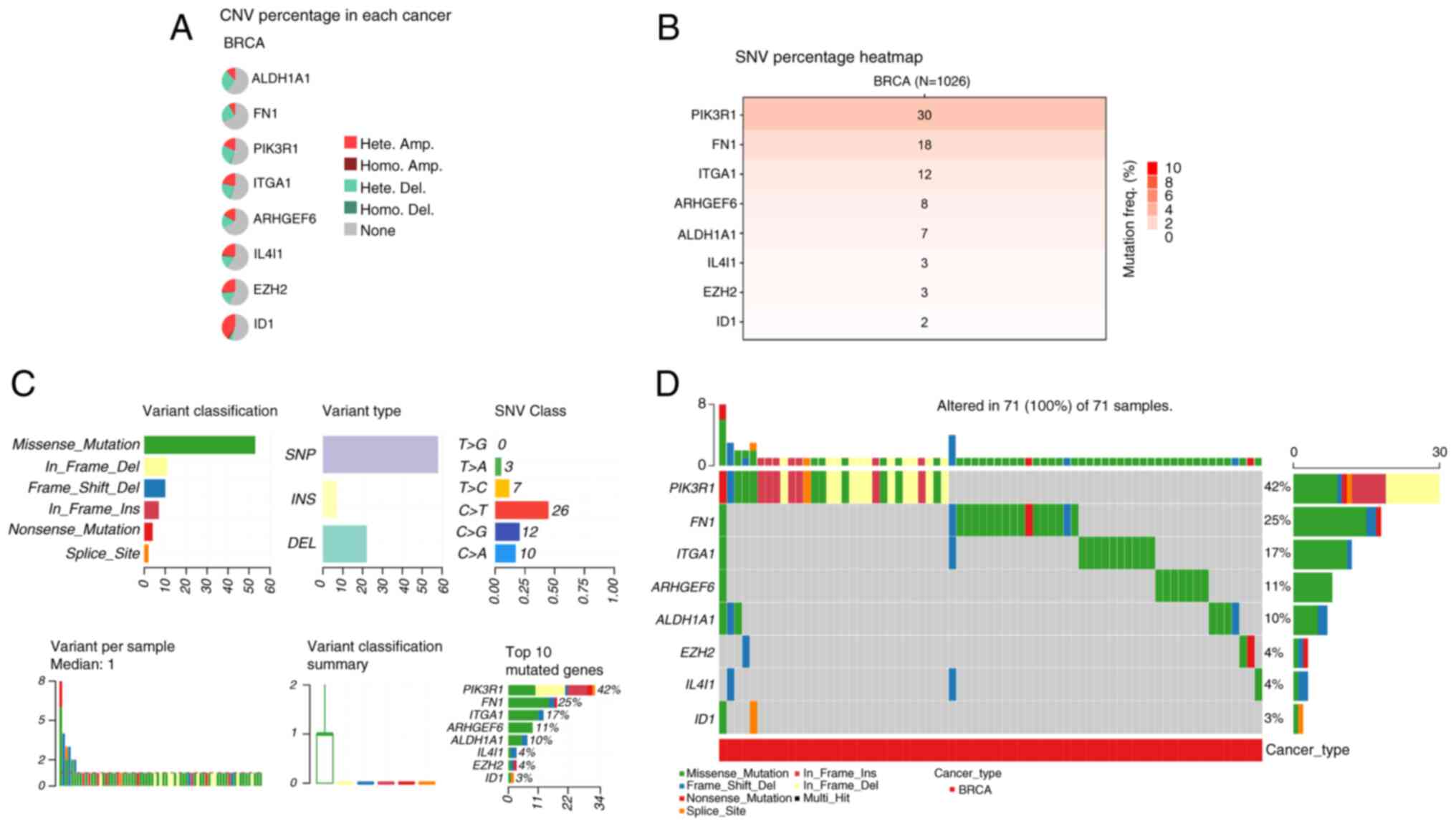

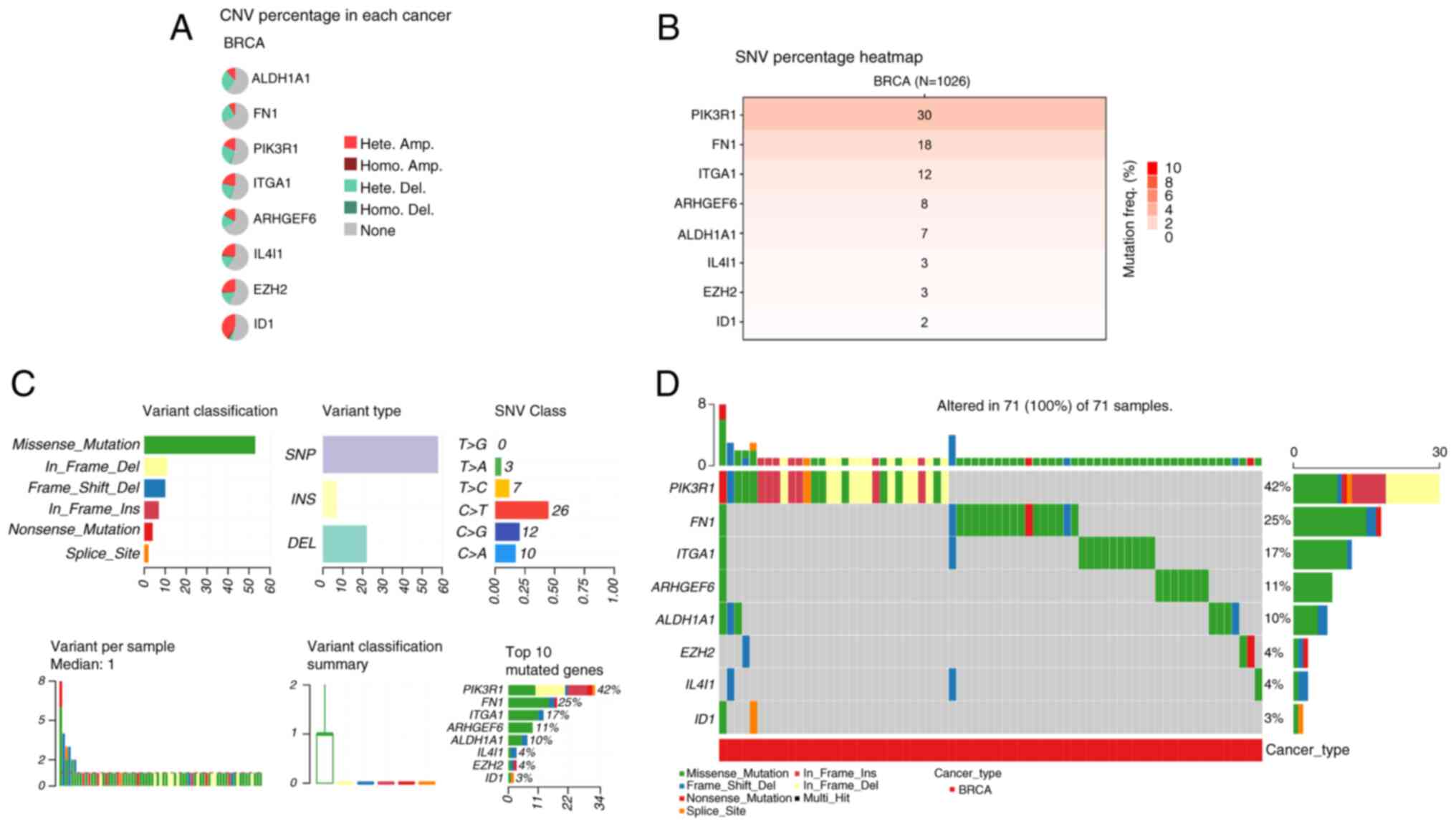

Comprehensive gene mutation analysis

of the 8 signature genes in BRCA

Next, a comprehensive analysis of gene mutations in

the signature genes in BRCA was performed, which revealed

significant genomic alterations across multiple samples, providing

valuable insights into the landscape of somatic mutations in

cancer. CNV analysis revealed diverse CNV percentages among the 8

genes in patients with BRCA (Fig.

3A). Notably, ID1 exhibited the highest percentage of

heterozygous amplification, whereas PIK3R1 showed the highest

percentage of heterozygous deletion. By contrast, nearly all the

genes displayed a low percentage of homozygous amplification. The

SNV heatmap further revealed that PIK3R1 had the highest mutation

frequency in BRCA samples, followed by FN1 and ITGA1 (Fig. 3B). Among the mutation types,

missense mutations were the most prevalent, with single nucleotide

polymorphisms identified as the primary variant type. Additionally,

C>T transitions were the most common substitution pattern in the

SNV class, with PIK3R1 emerging as the most frequently mutated gene

(Fig. 3C and D).

| Figure 3.Gene mutation analysis of 8 signature

genes in BRCA. (A) The CNV percentage of 8 signature genes in BRCA

samples was evaluated to assess the genomic alterations. (B) A

heatmap displaying the SNV percentage of the 8 signature genes in

breast cancer samples (n=1,026) was generated to visualize the

mutation frequency. (C) The gene mutation details of signature

genes, including variant classification, variant type, SNV Class,

variants per sample, variant classification summary and the top 10

mutated genes. (D) The mutation types of 8 signature genes altered

in 71 (100%) of 71 BRCA samples. BRCA, breast cancer; CNV, copy

number variation; Hete Amp, heterozygous amplification; Homo Amp,

homozygous amplification; Hete Del, heterozygous deletion; Homo

Del, homozygous deletion; SNV, single nucleotide variant. |

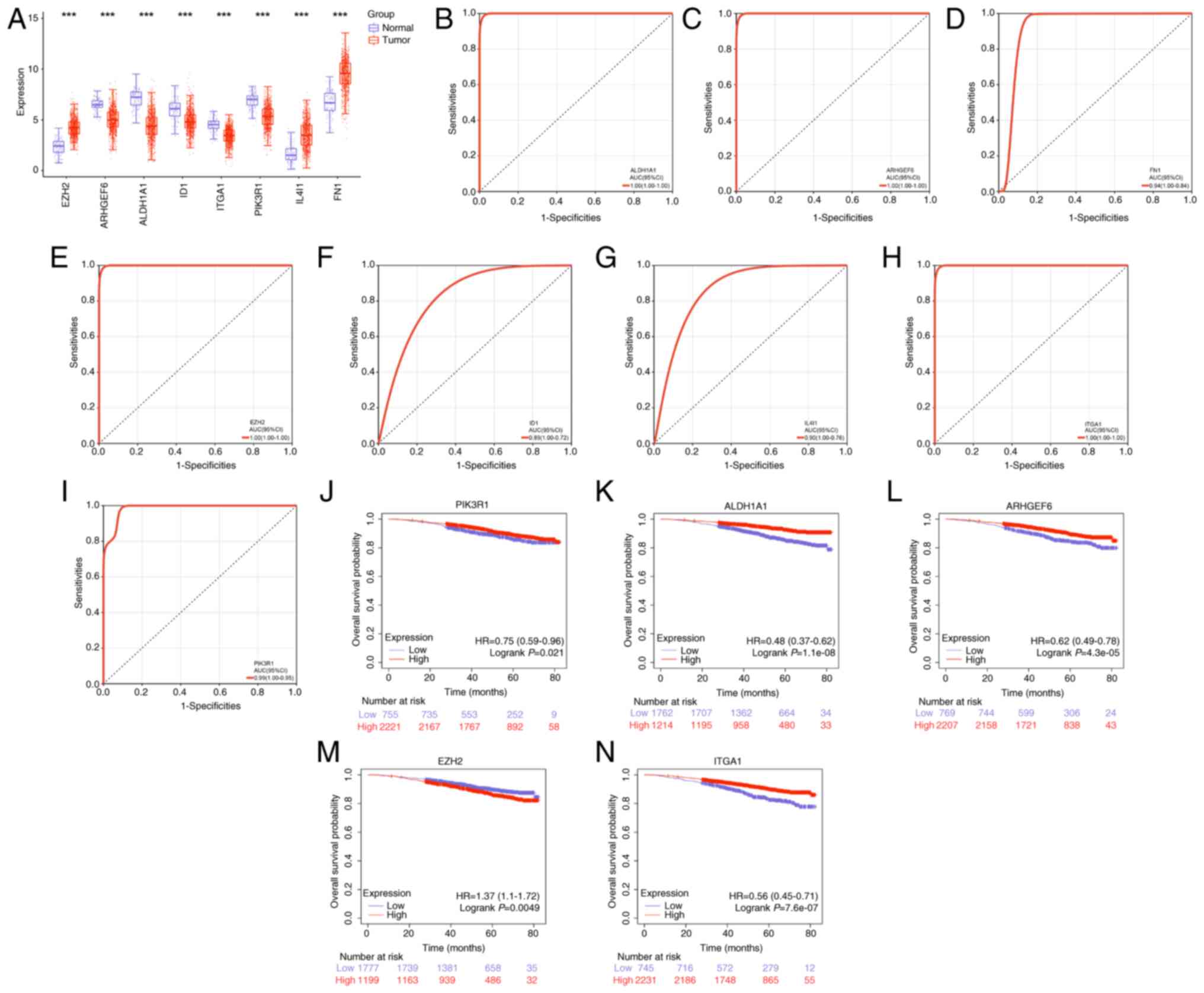

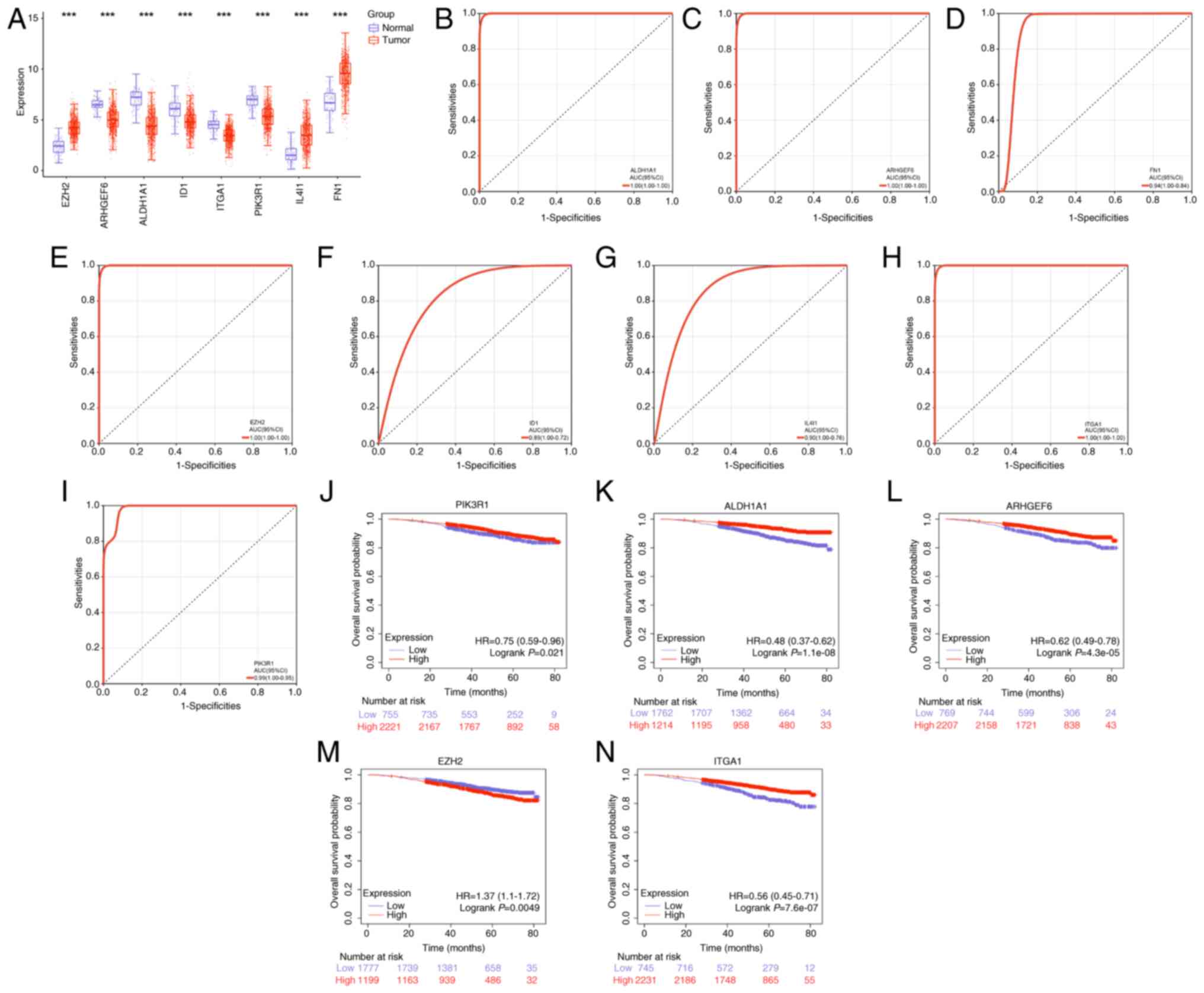

Identification of 5 candidate genes

with diagnostic and prognostic value in BRCA

The expression levels of the 8 signature genes in

the normal and BRCA tumor groups were further analyzed. The results

revealed that EZH2, IL4I1 and FN1 were upregulated in the tumor

group, whereas the remaining genes were downregulated (Fig. 4A). ROC curve analysis demonstrated

that ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6, EZH2, ITGA1 and PIK3R1 exhibited high

diagnostic value for BRCA (Fig.

4B-I). KM survival analysis further revealed the prognostic

significance of these genes. Specifically, high expression levels

of ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6, ITGA1 and PIK3R1 were associated with improved

OS, whereas high EZH2 expression was associated with a poorer OS

(Fig. 4J-N). These findings

highlight ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6, EZH2, ITGA1 and PIK3R1 as potential

diagnostic biomarkers for patients with BRCA, with prognostic

implications.

| Figure 4.Candidate genes with diagnostic and

prognostic value in BRCA were identified. (A) The expression levels

of 8 signature genes in normal and BRCA tumor groups. (B-I) The

receiver operating calibration curve analysis of 8 signature genes.

The top 5 genes with the highest AUC values are ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6,

EZH2, ITGA1 and PIK3R1. (J-N) The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of

PIK3R1, ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6, EZH2 and ITGA1. ***P<0.001. BRCA,

breast cancer; AUC, area under the curve; HR, hazard ratio; CI,

confidence interval; ALDH1A1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family

member A1; ARHGEF6, Rac/Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 6;

EZH2, enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit;

ITGA1, integrin α1; ID1, inhibitor of DNA binding 1; FN1,

fibronectin. |

ARHGEF6 is the key gene of the 5

candidate genes

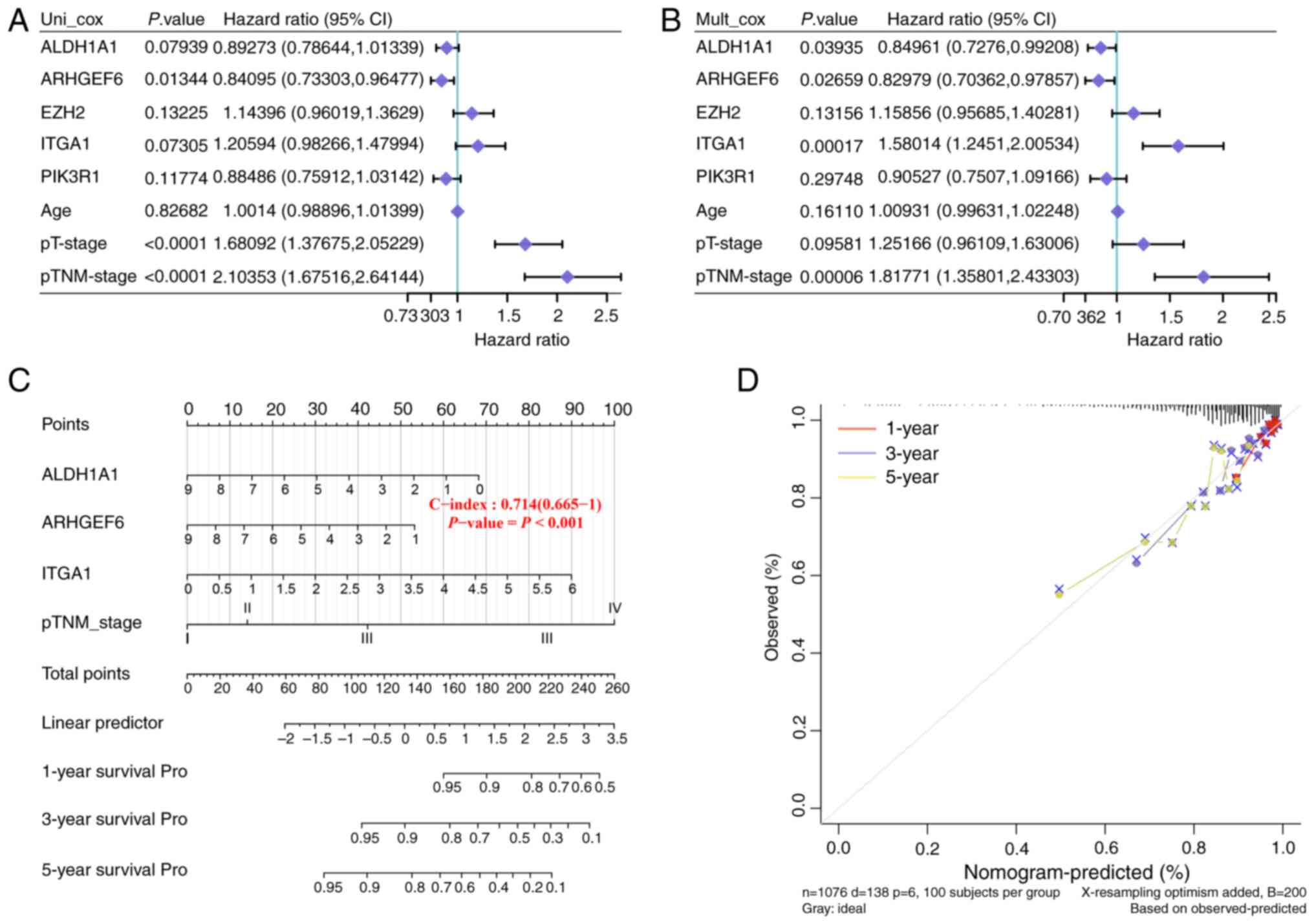

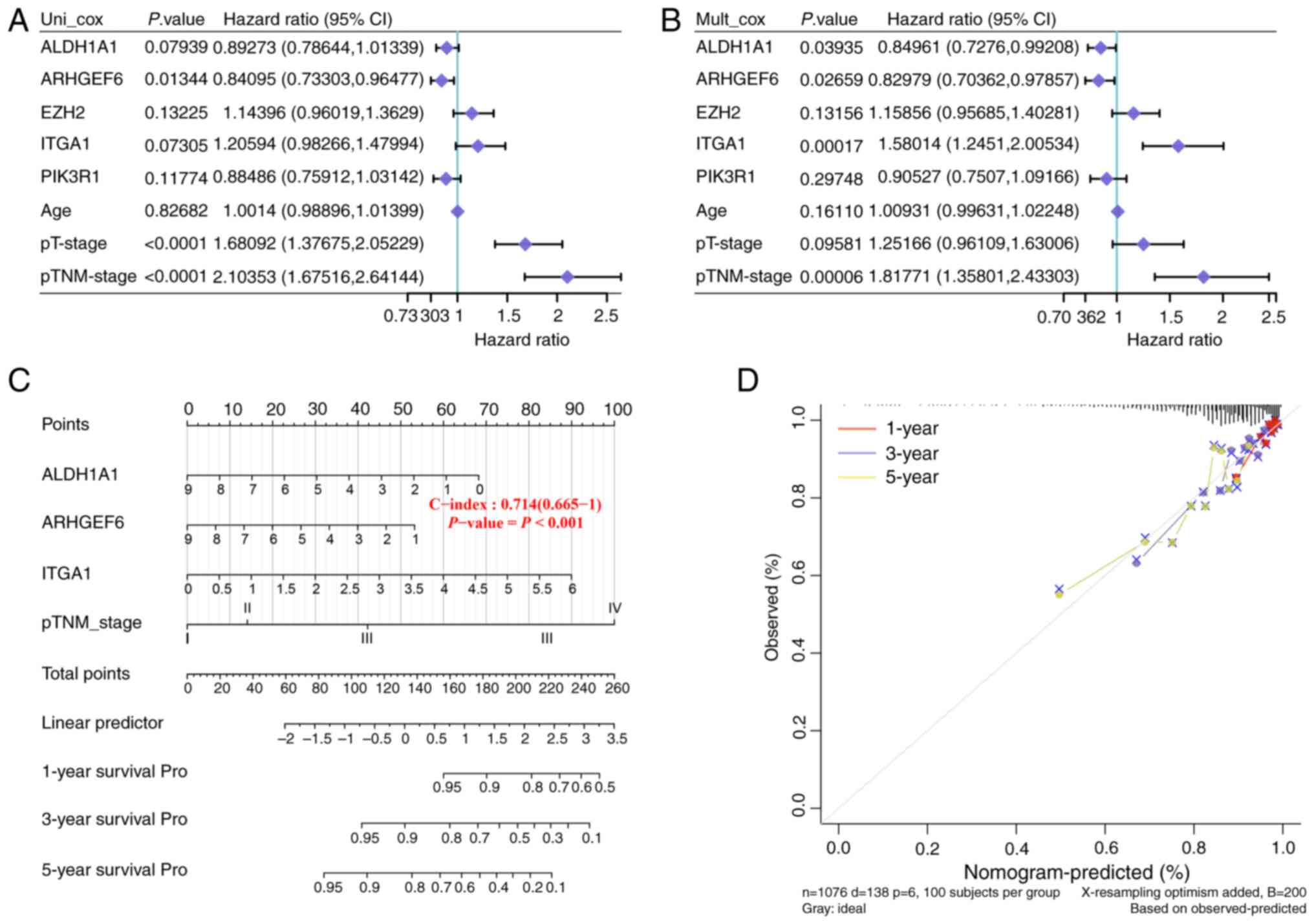

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

were performed to estimate the prognostic significance of the

candidate prognostic genes (Fig. 5A and

B). In univariate analysis, ARHGEF6 was significantly

associated with better overall survival, while advanced pT-stage

and pTNM-stage predicted worse outcomes (Fig. 5A). In multivariate analysis, ARHGEF6

remained an independent protective factor, whereas ITGA1 and

pTNM-stage were independent risk factors (Fig. 5B). To facilitate accurate prognosis

prediction for patients with BRCA, a nomogram was subsequently

created on the basis of the independent prognostic factors

identified via multivariate Cox regression analysis. This nomogram

integrated multiple clinical characteristics, including ALDH1A1,

ARHGEF6, ITGA1 and the pTNM stage (Fig.

5C), which were evaluated via a calibration curve. These curves

were generated to assess the agreement between the predicted

survival probabilities from the nomogram and the actual observed

survival rates at 1, 3 and 5 years. The results in Fig. 5D show that the predicted results

closely corresponded to the actual results, which indicated that

this nomogram had high predictive accuracy. On the basis of these

findings, ARHGEF6 was targeted as the key gene in the present

study.

| Figure 5.ARHGEF6 was targeted in the present

study as the key gene. (A) Univariate and (B) multivariate Cox

regression analyses were performed to assess the prognostic

significance of PIK3R1, ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6, EZH2 and ITGA1. (C) The

prognostic nomogram integrated ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6, ITGA1 and pTNM

stage to predict the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival probability. (D)

The performance of the prognostic nomogram was evaluated using

calibration curves. ALDH1A1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member

A1; ARHGEF6, Rac/Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 6; EZH2,

enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit; ITGA1,

integrin α1; CI, confidence interval. |

ARHGEF6 is a tumor suppressor gene in

BRCA

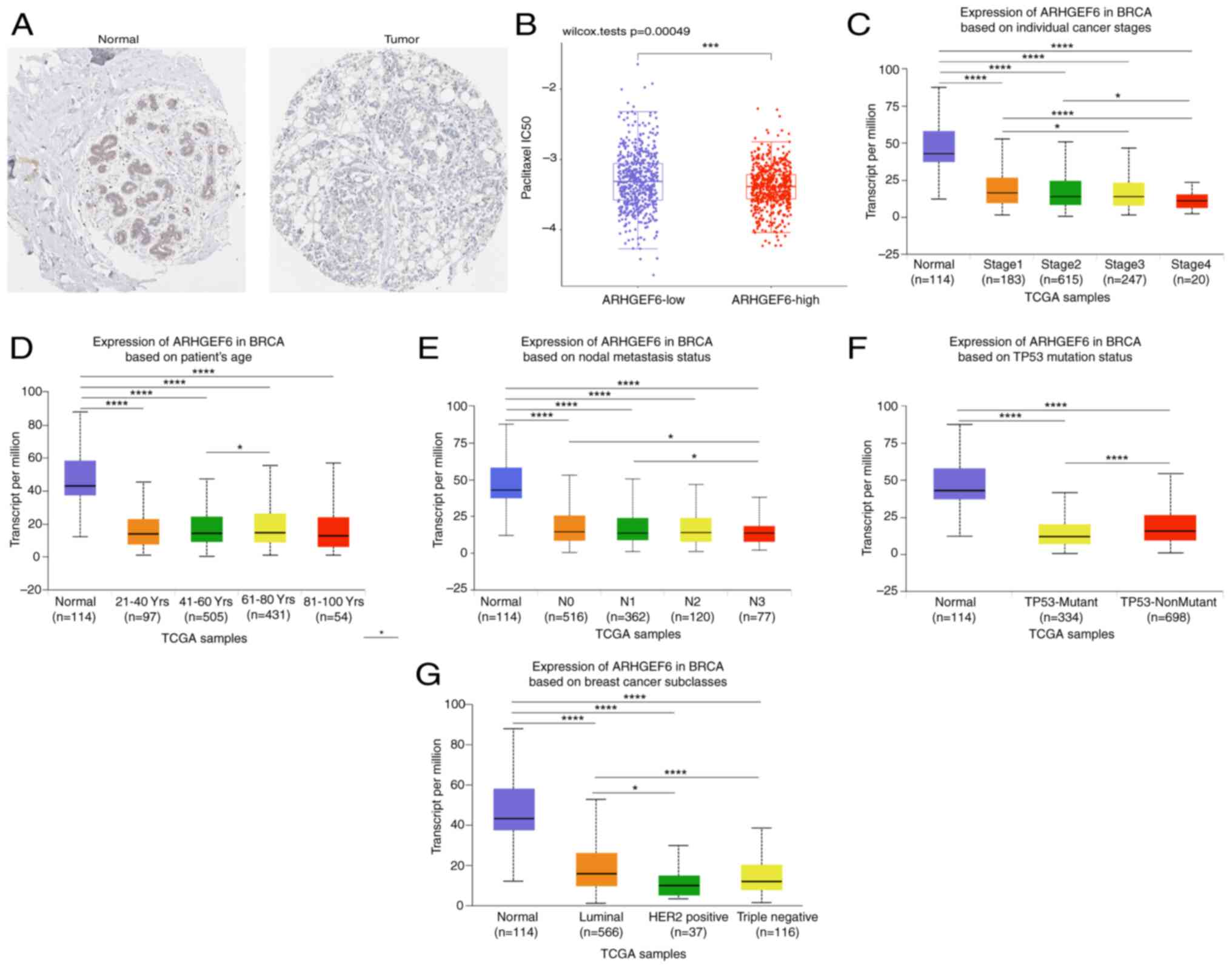

Analysis using the HPA database revealed that the

ARHGEF6 protein levels were significantly lower in BRCA tumor

tissues than in normal tissues (Fig.

6A). Higher ARHGEF6 expression was associated with lower

IC50 values in the paclitaxel sensitivity analysis,

suggesting its potential role in guiding personalized therapeutic

strategies (Fig. 6B). The

downregulation of ARHGEF6 was observed across various clinical

subgroups, including different cancer stages (Fig. 6C), age groups (Fig. 6D), nodal metastasis statuses

(Fig. 6E) and TP53 mutation

statuses (Fig. 6F). However, the

differences in ARHGEF6 expression among these clinical subgroups

were relatively minor. ARHGEF6 expression across molecular subtypes

of BRCA was further compared and it was found that ARHGEF6 was

downregulated in the Luminal, HER2-positive and TNBC subtypes

compared with normal tissues (Fig.

6G). Compared with the Luminal subtype, the ARHGEF6 levels were

significantly lower in both the HER2-positive and TNBC groups

(Fig 6G). Although ARHGEF6

expression was slightly higher in TNBC than in the HER2-positive

group, the difference was not statistically significant (Fig 6G). Although both HER2-positive and

TNBC subtypes showed reduced ARHGEF6 expression compared with the

normal breast tissue and Luminal subtypes, TNBC was selected for

functional validation due to its poor prognosis and lack of

targeted therapies.

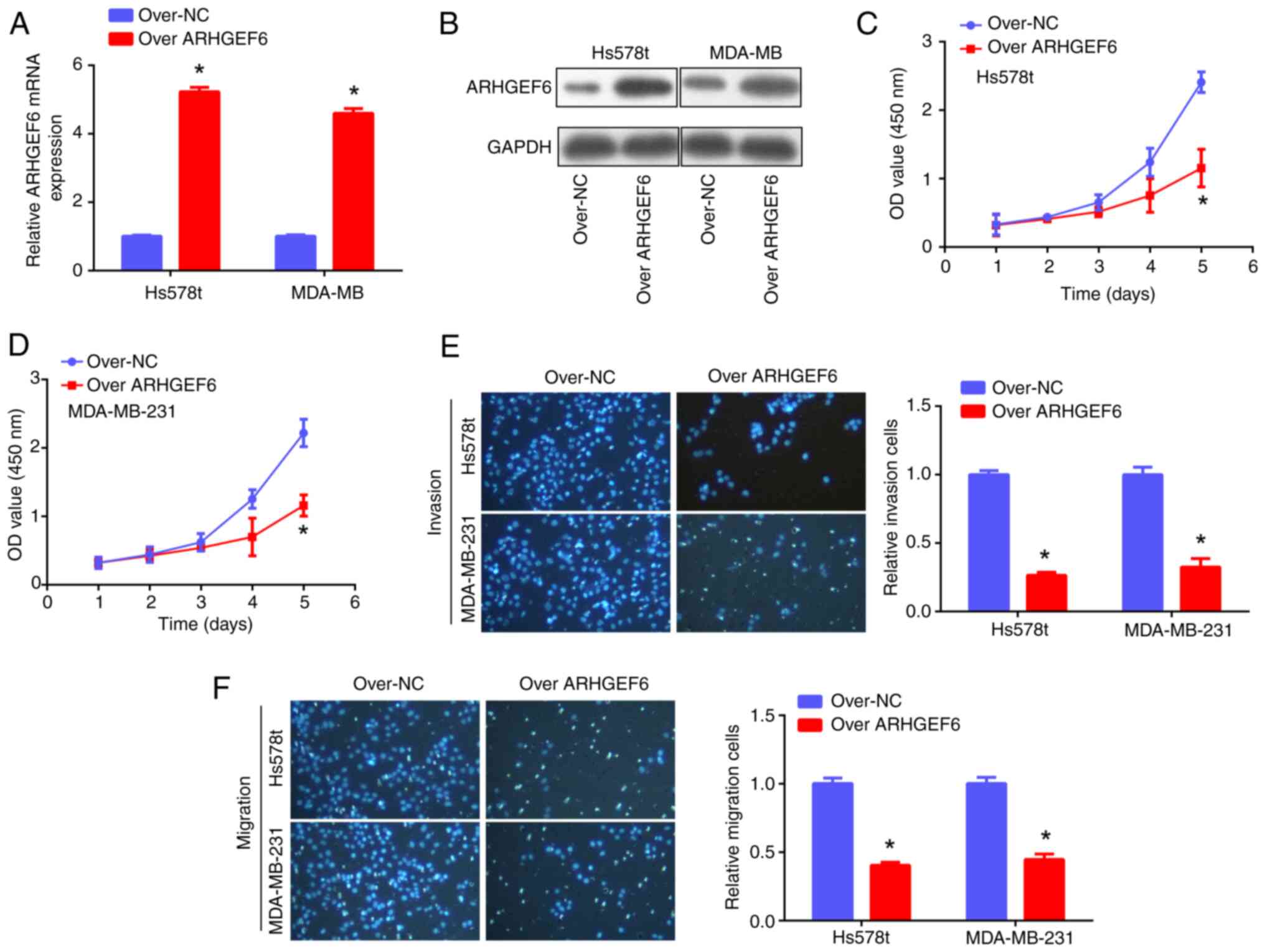

ARHGEF6 overexpression suppresses cell

proliferation, invasion and migration and promotes apoptosis

For the cellular experiments, ARHGEF6 was first

overexpressed in Hs578t and MDA-MB-231 cells, as confirmed by PCR

and western blotting assays (Fig. 7A

and B). Subsequent functional experiments demonstrated that

ARHGEF6 overexpression significantly suppressed the proliferation

(Fig. 7C and D), invasion and

migration (Fig. 7E and F) of BRCA

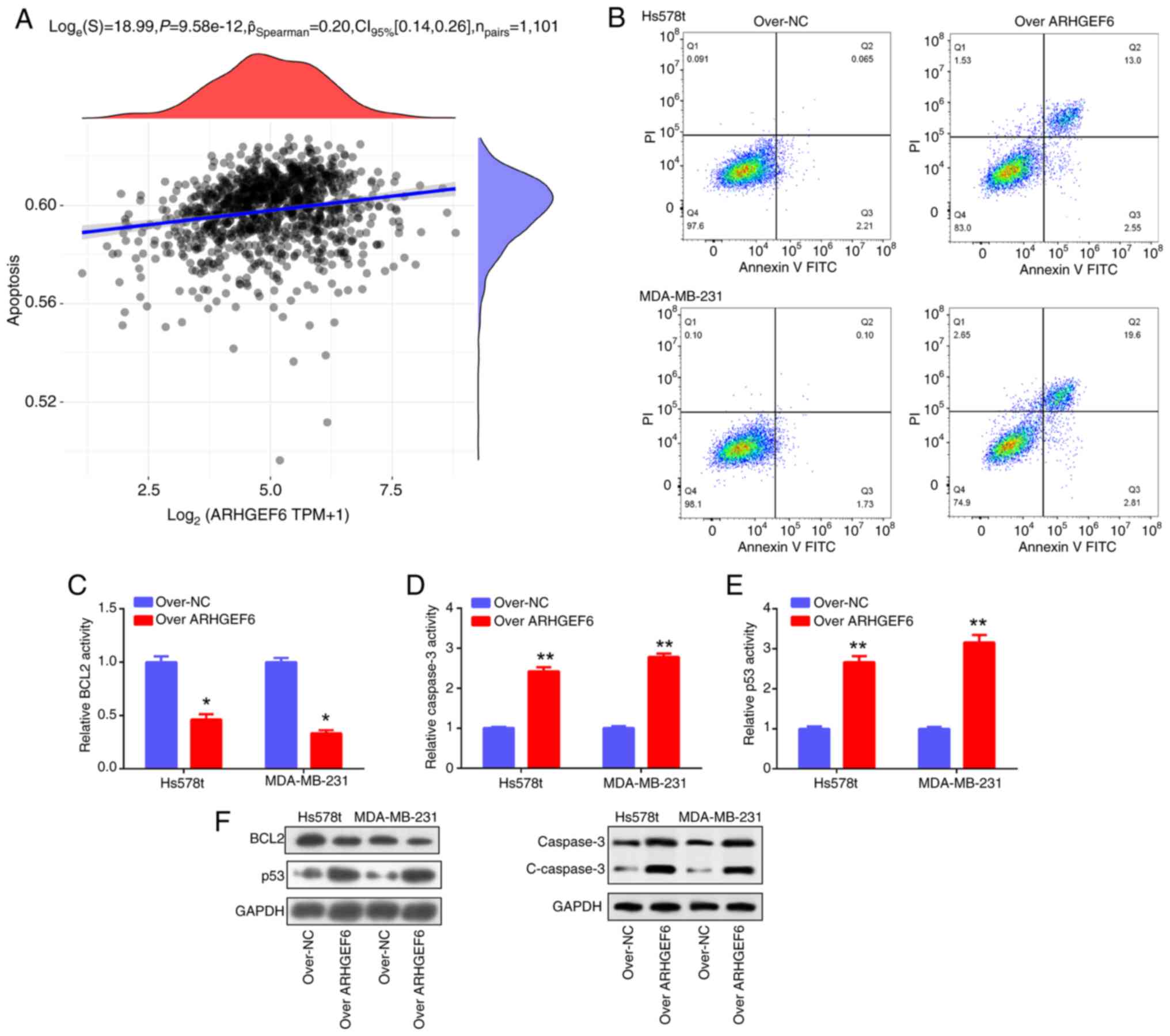

cell lines. Furthermore, ARHGEF6 was found to be positively

correlated with apoptosis (Fig.

8A), a finding further validated by flow cytometry (Fig. 8B), PCR and western blotting

analyses. Mechanistically, ARHGEF6 overexpression downregulated

BCL2 while upregulating caspase-3 and p53 at both the mRNA and

protein levels, along with increased cleaved caspase-3 protein

expression, thereby promoting apoptosis in BRCA cells (Fig. 8C-F). Collectively, these results

highlight ARHGEF6 as a tumor suppressor gene in BRCA that regulates

cell growth, invasion, migration and apoptosis.

Discussion

Clinical biomarkers are essential for predicting

treatment response and optimizing therapy selection (16). For example, genetic mutations such

as BRAF mutations in melanoma can help predict the response to

targeted therapies (17,18). Similarly, biomarkers such as

programmed death-ligand 1 expression in tumors have been utilized

to determine which patients can benefit from immune checkpoint

inhibitors in various cancer types (19,20).

BRCA is a heterogeneous disease with various subtypes according to

the presence or absence of specific molecular markers (21,22).

At present, it is vital to identify biomarkers and genetic

signatures related to BRCA because current diagnostic tools lack

sufficient sensitivity and specificity for early-stage detection,

leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, existing

biomarkers may not fully capture tumor heterogeneity, limiting

personalized therapy options. Improving biomarker discovery can

facilitate earlier intervention and better patient outcomes.

In the present study, the overlapping DEGs from the

GSE21422 and TCGA-BRCA datasets were selected due to their

comprehensive breast cancer gene expression profiles and large

sample sizes. Overlapping DEGs identified from these datasets were

enriched primarily in the regulation of angiogenesis,

collagen-containing extracellular matrix (ECM) and metal ion

binding. Angiogenesis plays a vital role in the growth and

metastasis of tumors, including BRCA. Several regulatory factors

have been identified in the context of BRCA angiogenesis. For

example, vascular endothelial growth factor is a key angiogenic

factor that promotes the formation of new blood vessels (23,24).

The primary element of the ECM, collagen, is essential for

preserving tissue integrity (25).

In BRCA, alterations in the composition and organization of

collagen within the ECM have been observed (26). Metal ions are essential for various

physiological processes, but their dysregulation can contribute to

cancer development (27). In BRCA,

metal ion-binding proteins have been implicated in tumor

progression and angiogenesis (28).

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these processes

can provide valuable insights for developing targeted therapies and

improving patient outcomes in BRCA treatment.

In the present study, on the basis of the

overlapping genes, risk score model, expression, ROC and KM

survival analyses were performed and 5 genes with diagnostic value

were identified, namely, ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6, EZH2, ITGA1 and PIK3R1.

The prognostic nomogram revealed that ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6 and ITGA1

also had prognostic value. ALDH1A1 is involved in the oxidation of

aldehydes (29,30); it has also been investigated in the

context of cancer, in which its upregulation has been related to

tumor initiation, progression and resistance to chemotherapy

(31). For example, in BRCA, cancer

stem cells are expected to play a role in tumor recurrence and

metastasis and ALDH1A1 is frequently utilized as a marker for these

cells (32,33). ITGA1 is a transmembrane receptor

protein involved in cell adhesion and signaling (34). ITGA1 is abnormally expressed in

cancer and is associated with tumor progression (35,36).

In BRCA, ITGA1 has been identified as a potential biomarker for

predicting tumor aggressiveness and patient prognosis (37).

Notably, ARHGEF6 was identified as the key gene.

ARHGEF6 is dysregulated in lung adenocarcinoma and medulloblastoma

(38,39). Additionally, cancer metastasis

involves a process known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition,

which is associated with ARHGEF6 (40,41).

Targeting ARHGEF6 and its downstream signaling pathways may have

therapeutic potential for inhibiting cancer metastasis. As key

players in several biological processes, ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6 and ITGA1

have also been linked to tumor growth, metastasis and therapeutic

resistance. These findings may help in the development of targeted

treatments and biomarkers for improved diagnostic and treatment

results.

Moreover, the functions of ARHGEF6 were investigated

in cell-based experiments in the present study. Using public

databases, downregulated ARHGEF6 mRNA and protein levels were

detected in BRCA. ARHGEF6 was overexpressed and CCK-8, Transwell

and apoptosis assays were performed. The data demonstrated that

ARHGEF6 overexpression suppressed cell proliferation, invasion and

migration while promoting cell apoptosis. These findings suggest

that ARHGEF6 is a suppressor gene in BRCA, which could have

implications for the clinical treatment of BRCA.

There are limitations to the present study. First,

validation was only performed in Hs578T and MDA-MB-231 cells, and

other BRCA subtypes or animal models were not used, which limits

the broad applicability of the conclusions. In future studies,

animal experiments will further verify the biological function of

ARHGEF6 and elucidate its underlying mechanisms. Additionally, the

present study did not thoroughly investigate clinical heterogeneity

factors, such as molecular subtypes, patient age and treatment

regimens, which may influence gene expression and patient

prognosis. Therefore, future research should expand the clinical

sample size, and further validate the clinical prognostic value of

ARHGEF6, thereby enhancing its potential for clinical

translation.

Overall, the present study identified novel

diagnostic indicators (such as ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6, EZH2, ITGA1 and

PIK3R1) and prognostic indicators (such as ALDH1A1, ARHGEF6 and

ITGA1) for BRCA, identified a key gene, ARHGEF6, and confirmed its

function by cellular experiments. These findings provide valuable

directions for understanding BRCA tumor development, progression

and response to therapy. These findings may facilitate the

development of novel therapeutic targets and personalized treatment

strategies and thus the improvement of patient outcomes in BRCA

management.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by Natural Science Foundation of

Bengbu Central Hospital (Grant No. 2025bbsy01 and 2025bbsy17).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YZ, DZ and XS conceived and designed the study,

analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. QS, LY and WL analyzed

data. XZ, WF and BL performed experiments. CX, JL, HF and QZ

supervised the study, revised the manuscript and contributed to

data interpretation. YZ and QZ confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liyanage PY, Hettiarachchi SD, Zhou Y,

Ouhtit A, Seven ES, Oztan CY, Celik E and Leblanc RM:

Nanoparticle-mediated targeted drug delivery for breast cancer

treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1871:419–433. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Al-Mulhim F, Alqosaib AI, Al-Muhnna A,

Fari K, Abdel-Ghany S, Rizk H, Prince AB, Isichei A and Sabit H:

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated activation of CDH1 suppresses metastasis of

breast cancer in rats. Electronic J Biotechnol. 53:54–60. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mao XD, Wei X, Xu T, Li TP and Liu KS:

Research progress in breast cancer stem cells: Characterization and

future perspectives. Am J Cancer Res. 12:3208–3222. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yousef AJA: Male breast cancer:

Epidemiology and risk factors. Semin Oncol. 44:267–272. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Momenimovahed Z and Salehiniya H:

Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast

cancer in the world. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 11:151–164.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lei Y, Tang R, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Liu

J, Yu X and Shi S: Applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer

research: Progress and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 14:912021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang K, Li L, Fu L, Yuan Y, Dai H, Zhu T,

Zhou Y and Yuan F: Integrated bioinformatics analysis the function

of RNA binding proteins (RBPs) and their prognostic value in breast

cancer. Front Pharmacol. 10:1402019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Feng Y, Spezia M, Huang S, Yuan C, Zeng Z,

Zhang L, Ji X, Liu W, Huang B, Luo W, et al: Breast cancer

development and progression: Risk factors, cancer stem cells,

signaling pathways, genomics, and molecular pathogenesis. Genes

Dis. 5:77–106. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Marra A, Trapani D, Viale G, Criscitiello

C and Curigliano G: Practical classification of triple-negative

breast cancer: Intratumoral heterogeneity, mechanisms of drug

resistance, and novel therapies. NPJ Breast Cancer. 6:542020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sheikh A, Hussain SA, Ghori Q, Naeem N,

Fazil A, Giri S, Sathian B, Mainali P and Al Tamimi DM: The

spectrum of genetic mutations in breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev. 16:2177–2185. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Viedma-Rodríguez R, Baiza-Gutman L,

Salamanca-Gómez F, Diaz-Zaragoza M, Martínez-Hernández G,

Esparza-Garrido R, Velázquez-Flores MA and Arenas-Aranda D:

Mechanisms associated with resistance to tamoxifen in estrogen

receptor-positive breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 32:3–15. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Nagini S: Breast cancer: Current molecular

therapeutic targets and new players. Anticancer Agents Med Chem.

17:152–163. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kretschmer C, Sterner-Kock A, Siedentopf

F, Schoenegg W, Schlag PM and Kemmner W: Identification of early

molecular markers for breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 10:152011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Thul PJ and Lindskog C: The human protein

atlas: A spatial map of the human proteome. Protein Sci.

27:233–244. 2018. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sutcliffe M, Radley G and Barton A:

Personalized medicine in rheumatic diseases: How close are we to

being able to use genetic biomarkers to predict response to TNF

inhibitors? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 16:389–396. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ahmadzada T, Kao S, Reid G, Boyer M, Mahar

A and Cooper WA: An update on predictive biomarkers for treatment

selection in non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Med. 7:1532018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pao W and Girard N: New driver mutations

in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 12:175–180. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Meng X, Huang Z, Teng F, Xing L and Yu J:

Predictive biomarkers in PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade

immunotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 41:868–876. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sivapiragasam A, Kumar P, Sokol ES,

Albacker LA, Killian JK, Ramkissoon SH, Huang RSP, Severson EA,

Brown CA, Danziger N, et al: Predictive biomarkers for immune

checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Med.

10:53–61. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Januškevičienė I and Petrikaitė V:

Heterogeneity of breast cancer: The importance of interaction

between different tumor cell populations. Life Sci. 239:1170092019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ibragimova MK, Tsyganov MM and Litviakov

NV: Molecular-genetic portrait of breast cancer with triple

negative phenotype. Cancers (Basel). 13:53482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Melincovici CS, Boşca AB, Şuşman S,

Mărginean M and Mihu C, Istrate M, Moldovan IM, Roman AL and Mihu

C: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-key factor in normal

and pathological angiogenesis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 59:455–467.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kajdaniuk D, Marek B, Borgiel-Marek H and

Kos-Kudła B: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-part 1: In

physiology and pathophysiology. Endokrynol Pol. 62:444–455.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yuan Z, Li Y, Zhang S, Wang X, Dou H, Yu

X, Zhang Z, Yang S and Xiao M: Extracellular matrix remodeling in

tumor progression and immune escape: from mechanisms to treatments.

Mol Cancer. 22:482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Insua-Rodríguez J and Oskarsson T: The

extracellular matrix in breast cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev.

97:41–55. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Park KC, Dharmasivam M and Richardson DR:

The role of extracellular proteases in tumor progression and the

development of innovative metal ion chelators that inhibit their

activity. Int J Mol Sci. 21:68052020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Stelling MP, Motta JM, Mashid M, Johnson

WE, Pavão MS and Farrell NP: Metal ions and the extracellular

matrix in tumor migration. FEBS J. 286:2950–2964. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tomita H, Tanaka K, Tanaka T and Hara A:

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 in stem cells and cancer. Oncotarget.

7:11018–11032. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Poturnajova M, Kozovska Z and Matuskova M:

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 and 1A3 isoforms-mechanism of activation

and regulation in cancer. Cell Signal. 87:1101202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ciccone V, Morbidelli L, Ziche M and

Donnini S: How to conjugate the stemness marker ALDH1A1 with tumor

angiogenesis, progression, and drug resistance. Cancer Drug Resist.

3:26–27. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kong Y, Lyu N, Wu J, Tang H and Xie X,

Yang L, Li X, Wei W and Xie X: Breast cancer stem cell markers CD44

and ALDH1A1 in serum: Distribution and prognostic value in patients

with primary breast cancer. J Cancer. 9:3728–3735. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li W, Ma H, Zhang J, Zhu L, Wang C and

Yang Y: Unraveling the roles of CD44/CD24 and ALDH1 as cancer stem

cell markers in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Sci Rep. 7:138562017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Adorno-Cruz V and Liu H: Regulation and

functions of integrin α2 in cell adhesion and disease. Genes Dis.

6:16–24. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Gharibi A, La Kim S, Molnar J, Brambilla

D, Adamian Y, Hoover M, Hong J, Lin J, Wolfenden L and Kelber JA:

ITGA1 is a pre-malignant biomarker that promotes therapy resistance

and metastatic potential in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep.

7:100602017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wei L, Yin F, Zhang W and Li L: ITGA1 and

cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Int J

Clin Exp Pathol. 10:5522–5529. 2017.

|

|

37

|

Han Y, Wang J and Xu B: Novel biomarkers

and prediction model for the pathological complete response to

neoadjuvant treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. J Cancer.

12:936–945. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Tong L, Wang S, Yang J, Zhang Q, Gu X, Mo

T, Luo Y, Zhang C, Zhang J and Liu Y: Combined ARHGEF6 and tumor

mutational burden may serve as a potential biomarker for

immunotherapy of lung adenocarcinoma. Heliyon. 9:e185012023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hemmesi K, Squadrito ML, Mestdagh P, Conti

V, Cominelli M, Piras IS, Sergi LS, Piccinin S, Maestro R, Poliani

PL, et al: miR-135a inhibits cancer stem cell-driven

medulloblastoma development by directly repressing Arhgef6

expression. Stem Cells. 33:1377–1389. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Guan X, Guan X, Dong C and Jiao Z: Rho

GTPases and related signaling complexes in cell migration and

invasion. Exp Cell Res. 388:1118242020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhou W, Li X and Premont RT: Expanding

functions of GIT Arf GTPase-activating proteins, PIX Rho guanine

nucleotide exchange factors and GIT-PIX complexes. J Cell Sci.

129:1963–1974. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|