Introduction

Cancer has long been a paramount concern in global

public health, with the complexity of its pathogenesis extending

far beyond initial understanding. At present, clinical treatments

for cancer include radiotherapy, chemotherapy and some targeted

drugs. However, these treatments still cannot effectively relieve

pain or prolong the quality of life of the patient (1,2).

Therefore, identifying effective therapeutic targets for precision

medicine is of great significance.

The occurrence and development of cancer are

inextricably linked to epigenetic modifications, which are

influenced by environmental factors (3). Epigenetics has therefore emerged as a

research focus. DNA methylation, a key epigenetic modification,

refers to the addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases within

CpG islands by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). CpG islands act as

‘clusters of switch buttons’ in gene promoter regions, dynamically

regulating methylation similar to a light switch for gene

expression. Methylation acts as an ‘off button,’ silencing tumor

suppressor genes (4,5). Under normal physiological conditions,

DNA methylation accurately regulates gene activation and

repression, governing human organ development and contributing to

cancer initiation. DNA methylation also plays an important role in

cancer development and is often closely associated with the

silencing of tumor suppressor genes. When the CpG islands in tumor

suppressor genes are highly methylated, the expression of these

genes decreases, allowing tumor cells to escape regulation and

undergo rampant proliferation and metastasis, which seriously

threatens human life and health (6,7).

Therefore, in-depth study of the DNA methylation changes in various

target genes in cancer not only helps to understand the mechanisms

of cancer occurrence and development but is also expected to

provide new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for early diagnosis,

prognosis assessment and the targeted therapy of cancer (8).

The 14-3-3 gene family has been extensively studied

in cancer research (9). The 14-3-3

protein comprises seven isoforms (β, ε, γ, η, σ, τ and ζ), each

with distinct functions. This family regulates the activity,

stability, subcellular localization and interactions of client

proteins by mediating direct binding or promoting interactions with

other signaling molecules. These regulatory processes govern key

cellular pathways, including cell cycle control, apoptosis,

proliferation and programmed necrosis, often involving proteins

such as p53, cell division cycle 25C (CDC25C) and Bad (9,10).

14-3-3σ (SFN) is one of the numerous proteins closely associated

with cancer. SFN is a dimeric small molecule protein present in all

eukaryotes, particularly in epithelial cells (11). First identified in bovine brain

tissue, SFN has since been detected in various human organs,

including breasts, pancreas, stomach, colorectum, liver and kidneys

(12). The diversity of SFN

functions makes it a strong candidate as a therapeutic target for a

variety of diseases. Drawing from the existing literature on SFN in

the fields of epigenetics and cancer, the present review

synthesizes the role of the DNA methylation of SFN in different

malignancies, dissects its underlying mechanisms and evaluates its

potential as a diagnostic or prognostic biomarker and therapeutic

target.

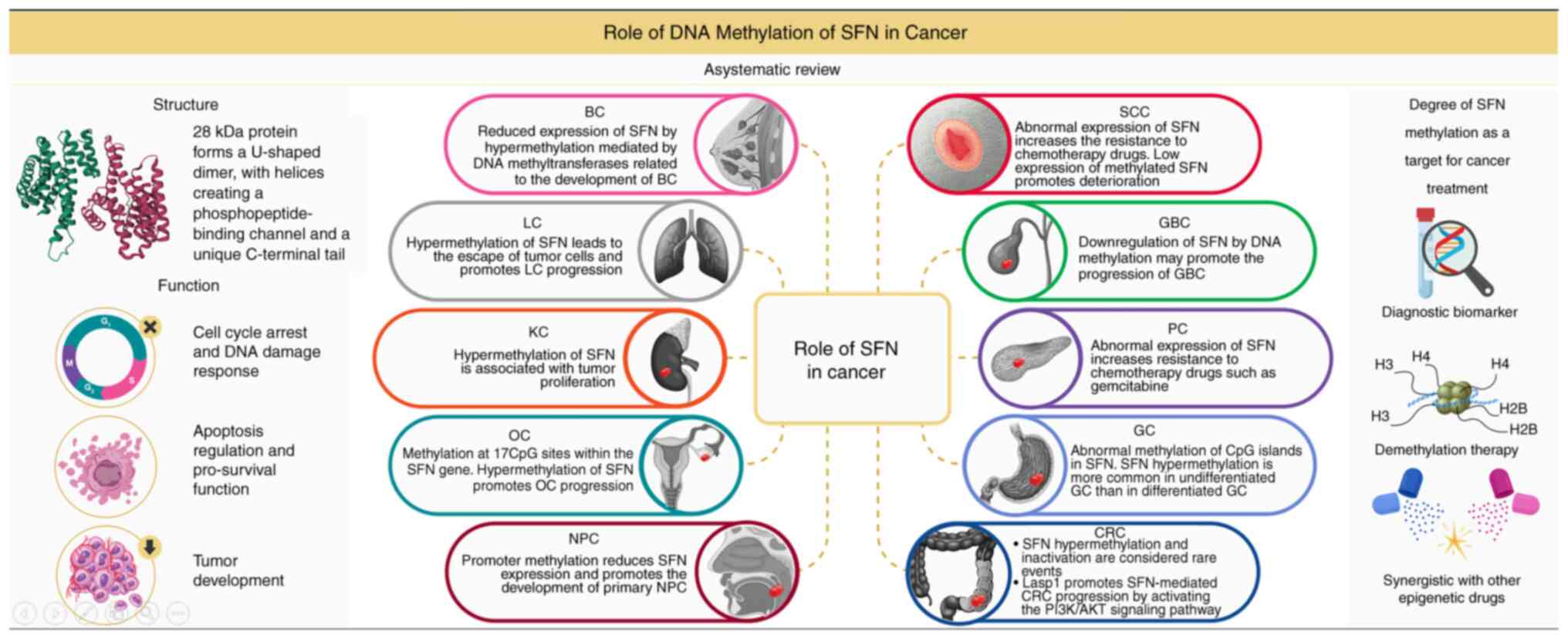

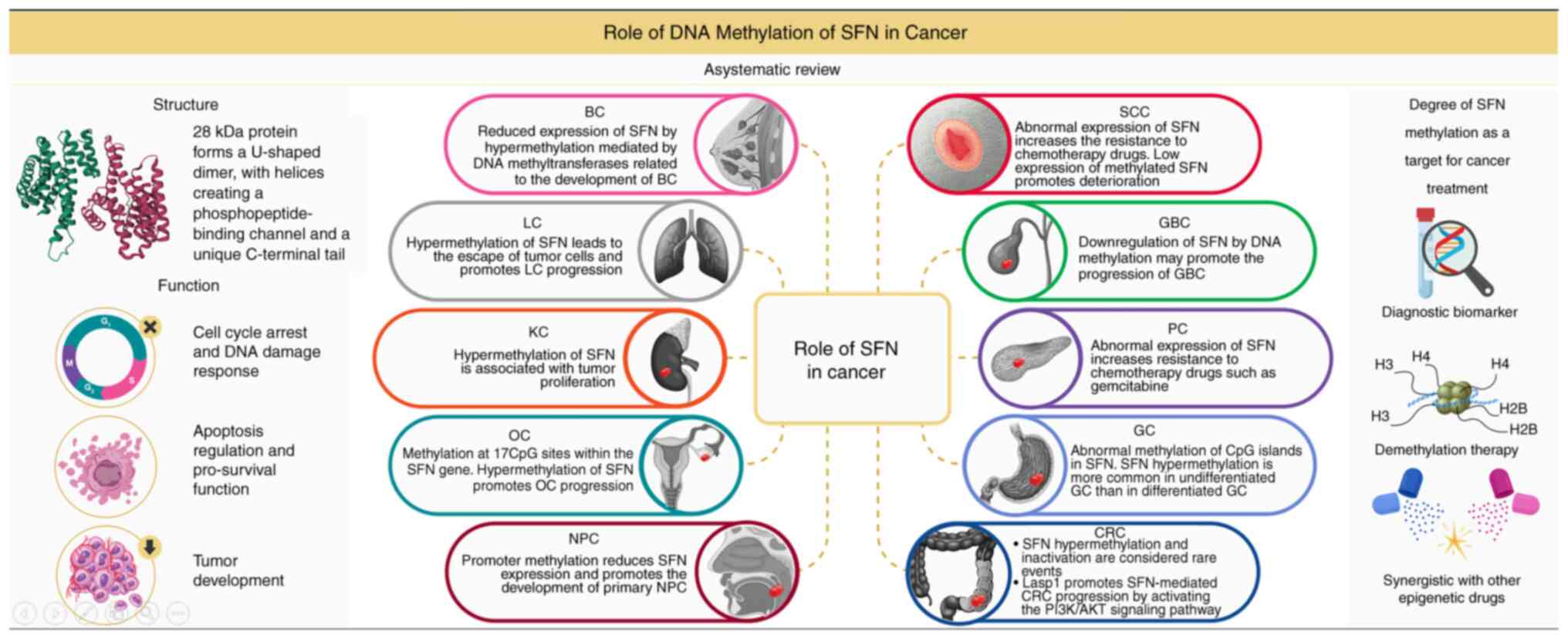

Structure and biological function of

SFN

The SFN protein is composed of 245 amino acids, with

a molecular weight of ~28 kDa. Similar to other family members, SFN

forms a typical ‘U’-shaped dimer structure via an N- and C-terminal

α-helix. Each monomer contains nine α-helices, among which helices

α3, α4 and α8 form a conserved phosphopeptide-binding channel

similar to a molecular locking structure, which recognize

phosphorylated proteins through charge matching (13). Through its unique structure and

multifunctional regulatory network, SFN modulates key biological

processes, including the cell cycle, DNA damage repair, apoptosis

and tumor suppression (14). In

recent years, the loss of SFN expression in cancer due to

epigenetic modifications (such as DNA methylation) has become a hot

topic of research, providing important clues for understanding the

tumorigenesis mechanism. The main functional regulatory networks of

the SFN protein include: i) Cell cycle arrest and DNA damage

response: SFN induces G2/M arrest by sequestering cell cycle

regulators (such as CDK2/cyclin E complexes) upon DNA damage,

preventing their nuclear translocation. For instance, in

p53-dependent responses, SFN maintains G2 arrest by binding

phosphorylated CDC25C and inhibiting CDK1 activation (15). ii) Apoptosis regulation and

pro-survival function: SFN inhibits apoptosis by binding to the

phosphorylated forms of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bad and Bax,

preventing their mitochondrial localization and subsequent

cytochrome C release under unstressed conditions (16). However, under conditions of

sustained DNA damage or oncogene activation, SFN protein

degradation can release the inhibition of apoptotic signals and

promote cell clearance (17). iii)

Tumor suppressor function: SFN expression is silenced in a variety

of epithelial tumors due to hypermethylation of promoter CpG

islands. Silencing SFN leads to cell cycle checkpoint defects,

genomic instability and apoptotic resistance, thereby promoting

tumor progression (18).

Restoration of SFN expression has been shown to significantly

reduce tumor cell proliferation and metastasis by inhibiting CDK

activity and suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

pathways. The silencing of SFN expression is closely related to

tumorigenesis, with promoter methylation being the main regulatory

mechanism (19). SFN acts as a

molecular scaffold integrating multiple signaling pathways. Studies

of its structure-function relationship provide a new direction for

the development of targeted cancer therapies, such as demethylation

drugs or phosphatase inhibitors. In the future, it will be

necessary to further analyze its interaction network in different

tissue microenvironments and explore its clinical application

potential as a biomarker or therapeutic target.

Relationship between DNA methylation and

cancer

Epigenetic modifications (such as DNA methylation,

histone modification and non-coding RNA regulation) play a pivotal

role in cancer development, with abnormal DNA methylation being one

of the most common epigenetic changes in tumor cells. DNA

methylation refers to the covalent addition of methyl groups to the

5′ position of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides (forming

5-methylcytosine), catalyzed by DNMTs (20). A number of studies have shown that

DNA methylation alters chromatin structure, DNA conformation,

stability and protein-DNA interactions, thereby regulating gene

expression (21–23). In normal cells, DNA methylation

regulates gene function through mechanisms such as promoter CpG

island hypermethylation and global genome hypomethylation. In

cancer, DNA methylation patterns are significantly disrupted, often

manifested as: i) Global hypomethylation, which promotes chromosome

instability and proto-oncogene activation; and ii) local

hypermethylation, which is concentrated in the promoter regions of

tumor suppressor genes, resulting in the silencing of their

expression (24,25). Different detection methods employ

distinct thresholds for defining hypermethylation. For instance, in

methylation-specific PCR (MSP), hypermethylation is identified when

the intensity of the methylated band exceeds 50% of the

unmethylated band. Pyrosequencing defines hypermethylation as

either a single CpG site methylation rate >30% or a regional

average >50%. Exceeding these hypermethylation thresholds

represents the molecular mechanism for the transcriptional

silencing of SFN, which correlates with malignancy in specific

cancer types (26). DNA methylation

affects genome stability and signaling pathway activity by

regulating gene expression silencing, making it an important

research direction in cancer diagnosis and treatment. Promoter CpG

island hypermethylation acts as an epigenetic switch for tumor

suppressor genes. DNA methylation forms dense chromatin structures

by recruiting methyl-binding proteins (such as methyl-CpG binding

protein 2) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), resulting in the

transcriptional silencing of genes. For example, in breast and lung

cancer, hypermethylation of the SFN promoter leads to defects in

G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis resistance, significantly promoting

tumor progression (27).

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase is a DNA repair enzyme that

protects genomic stability by clearing DNA damage induced by

alkylating agents. Hypermethylation of its promoter region leads to

gene silencing and loss of repair function, thereby increasing

mutation accumulation and promoting tumorigenesis (28). In tumor cells, signal transducers

and activators of transcription 5A, involved in cell proliferation

and immune regulation, exhibits promoter hypermethylation that

suppresses antitumor immune responses (such as T cell activation)

and facilitates immune escape (29). The clinical value of DNA methylation

is emerging in early diagnosis, prognosis, therapeutic targeting,

drug resistance modulation and immunotherapy synergy. Future

challenges in cancer research include identifying actionable

methylation targets, developing dynamic methylation regulation

strategies, and constructing methylation-driven gene networks.

Abnormal methylation of SFN in cancer

Breast cancer (BC)

BC is one of the most common malignant tumors, with

an increasing incidence among tumors afflicting women. In 2018

alone, 268,670 new cases of BC were reported in the United States

(30). As a heterogeneous disease

influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, BC remains a

significant health burden despite recent therapeutic advances.

Current research efforts in personalized treatment (previously

guided by disease severity) now focus on underlying biological

mechanisms. The search for new targets and treatment strategies is

important for patient survival and quality of life.

In recent years, DNA methylation is a major

epigenetic modification, and SFN (a tumor suppressor gene) is

frequently silenced by this modification in BC (31). Studies have shown that SFN DNA

methylation frequency exceeds 90% in BC. Additionally, SFN

hypermethylation has been observed in breast hyperplasia samples,

while normal tissues remain unmethylated (as determined by MSP

assay) (32,33). The downregulation of SFN has been

detected in BC samples by serial analysis of gene expression, but

no specific gene locus at the SFN site that could account for its

downregulation was identified. After the treatment of BC cells with

the DNMT inhibitor (DNMTI), 5-Azacytidine, SFN expression was

re-detected and found to be activated, indicating that SFN

underwent DNA methylation modification mediated by DNMTs. This

suggests that DNA hypermethylation of SFN is closely related to the

occurrence and development of BC (34). Another study grouped 77 patients

with BC (no symptoms of disease) and 34 patients with metastatic BC

(symptoms of disease), then DNA methylation in the serum samples

from these two groups was detected. The DNA methylation level was

higher in the BC group, indicating that SFN may serve as a

predictor of BC progression (35).

Therefore, SFN can be considered as a biomarker for screening

metastatic BC, both in early detection and for monitoring

subsequent treatment responses.

The specific mechanism by which SFN affects BC

progression is as follows. A study has shown that SFN is a

p53-dependent negative regulator of the cell cycle, blocking the

G2/M phase by inhibiting the formation of the CDC2-cyclin B1

complex. However, under conditions of hypermethylation, the

inactivation of SFN fails to block the cell cycle, thereby

promoting cancer progression (36).

The hypermethylation of the SFN gene promoter not only facilitates

BC diagnosis but also drives the development of new treatments.

Inhibiting DNA methylation of SFN is expected to become a potential

therapeutic target for BC, and drug design targeting this mechanism

could provide a valuable reference for the further clinical

treatment of BC.

Lung cancer (LC)

LC is the leading cause of cancer-related death

worldwide and includes two main subtypes: Small cell LC and

non-small cell LC (NSCLC) (37).

NSCLC accounts for ~75% of all LC cases (38). Most patients with NSCLC present with

advanced disease at diagnosis, as obvious symptoms often emerge in

the mid-to-late stages. Current clinical treatments for LC involve

a combination of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy (39), yet these approaches fail to

sufficiently improve the quality of life for patients with advanced

disease. The development of early diagnostic markers and targeted

therapeutics for LC remains a critical need. The upregulation of

oncogenes and the silencing of tumor suppressor genes are the main

causes of LC (40). A study has

shown that the loss of SFN expression caused by DNA methylation is

correlated with the carcinogenesis and prognosis of LC. SFN

methylation has been detected in the serum of 167 patients with

NSCLC, with methylation rates ranging from 64.6 to 100% (as

determined by MSP assay). Thus, SFN could be used as a marker for

the serological testing of NSCLC (41).

As for the specific mechanism of the involvement of

SFN in LC progression, current studies mainly focus on cell cycle

regulation and drug resistance. For instance, it has been shown

that when SFN is hypermethylated and its expression is absent in

LC, failure of cell cycle arrest leads to tumor cells escaping

constraints on abnormal proliferation, thereby promoting LC

progression (34). The therapeutic

effect of chemotherapy drugs is often affected by drug resistance.

In a cisplatin-treated NSCLC cell line (A549 cells), tripartite

motif containing 25-mediated cisplatin resistance is primarily due

to the downregulation of SFN, indicating that targeting SFN may be

a potential strategy to reverse cisplatin resistance (42). However, rare contradictory reports

exist regarding SFN expression in NSCLC. For instance, one study

documented that high SFN expression, as a result of SFN

hypomethylation, in orthotopic lung adenocarcinoma models is a key

driver of early-stage malignant progression (43). The conflicting observations

regarding SFN methylation in NSCLC fundamentally reflect the

complexity of epigenetic regulation. The methylation status of the

same gene across distinct genomic regions may drive tumorigenesis

through divergent mechanisms, while sample heterogeneity, technical

limitations and co-mutation backgrounds further exacerbate

interpretational discrepancies. Future research should integrate

spatial methylation profiling, single-cell multi-omics and clinical

prospective cohorts to establish dynamic SFN methylation models,

potentially uncovering novel epigenetic targets for precision

stratified therapy in NSCLC.

Kidney cancer (KC)

Worldwide, KC occurs more frequently in men than in

women. Although there have been advances in the treatment and

diagnosis of KC in recent years, KC remains one of the deadliest

malignancies of the urinary system; its incidence is increasing,

with an estimated 400,000 new cases per year, according to the most

recent data from the World Health Organization. The global

mortality rate is close to 175,000 deaths per year (44,45).

Risk factors for KC include smoking, obesity, hypertension, poor

diet and chronic kidney disease; acute/chronic kidney injury are

often precursors of KC (46,47).

At present, the main selected treatment for KC is based on the

location of the tumor and the stage of the disease. These options

can be divided into surgical and non-surgical treatments (48). While improved screening has

increased patient survival, rising KC prevalence and stagnant cure

rates highlight the need for early diagnostic markers and targeted

small-molecule inhibitors to prevent disease progression. Very

little is known about the role of SFN in KC, especially regarding

the effects of the DNA methylation of SFN. A study has shown

abnormal expression of SFN in 15 (38%) canine KC cases, with a

positive association between SFN expression and a significantly

reduced survival time observed (11). In human KC, SFN is typically

silenced by hypermethylation of its promoter. In a study of 31

patients with KC, methylation levels were found to increase

progressively with the malignancy of renal cancer, from normal to

cancerous kidney tissue. Among the 16 samples of renal cancer

tissues, 87.5% had complete hypermethylation of SFN (as determined

by MSP assay) (49). Additionally,

SFN can also influence cell cycle regulation, enabling tumor cells

to escape DNA damage caused by cisplatin and further promote tumor

cell proliferation. These findings indicate that SFN expression,

DNA methylation and the treatment of KC are closely related

(50). Whether SFN can unlock the

mystery of KC development or emerge as a key target for developing

KC treatment strategies remains to be further explored by

researchers.

Ovarian cancer (OC)

OC is the second most common cause of cancer-related

death in women worldwide, accounting for ~140,000 deaths annually.

This high mortality rate is largely due to a lack of clear early

diagnostic markers and delayed treatment (51). Most OC cases are definitively

diagnosed at an advanced stage, with a high recurrence rate. The

standard treatment for OC includes surgery and combination

chemotherapy. In the early stages, the disease can be successfully

treated with surgery alone. However, advanced stages require

complex chemotherapy regimens, with drugs such as bevacizumab

representing newer therapeutic options (52). While these targeted drugs have shown

progress in improving the prognosis of OC, it remains the deadliest

gynecological cancer in women. OC is generally divided into four

main types: Epithelial OC, germ cell tumors, sex cord-stromal

tumors and metastatic cancer (53).

DNA methylation, histone modification and gene silencing mediated

by non-coding RNAs are key processes in the development of OC and

represent new targets for cancer detection and treatment (54). In OC, SFN is primarily inactivated

by DNA methylation. A study evaluating SFN methylation as a

prognostic marker found that it is associated with OC but unable to

predict patient outcomes (MSP assay) (55). Hypermethylation of SFN promotes OC

progression.

Nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC)

NPC exhibits a significant geographical clustering,

with ~70% of the world's new cases concentrated in Southeast Asia

and East Asia. Among these regions, China has the highest incidence

of NPC, accounting for 47% of all cases (56). The main risk factors for NPC include

Epstein-Barr virus infection, genetic susceptibility, environmental

factors and diet (57). Current

prevention and control strategies focus on the following areas:

Screening of high-risk groups, risk factor intervention and

precision epidemiological studies. At present, only one study has

shown that SFN promoter methylation occurs in primary NPC tumors,

leading to decreased SFN expression; however, promoter

hypermethylation has not been detected in normal nasopharyngeal

epithelial cells (MSP-detected methylation rate: 63%). This

suggests that SFN expression may also serve as a prognostic marker

for NPC (58). SFN is a downstream

target gene of miR-597 and miR-675-5p. The downregulation of SFN by

miR-597 and miR-675-5p can drive EMT and promote the migration and

invasion of NPC (59,60). Additionally, SFN functions as a

tumor suppressor in vitro, inhibiting NPC cell invasion

through the SFN/EGFR/keratin-8 signaling axis (61). Collectively, these findings

highlight the research value of SFN in NPC progression.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

SCC can occur in multiple organs, including vulvar

SCC (VSCC), esophageal SCC (ESCC) and oral SCC (OSCC), among

others. SFN exhibits strong immune reactivity in SCCs from

different parts of the body (62).

VSCC is commonly found in young women, and the main treatment

method is radical surgery. However, the postoperative recurrence

rate is relatively high (63).

Targeted therapy has attracted attention, driving researchers to

identify tumor-associated factors and novel therapeutic markers. In

a previous study, SFN CpG methylation was found in ~53% of cases

(as determined by MSP assay) (64).

In another study of 302 cases of VSCC, it was confirmed that the

expression of SFN protein was downregulated, contributing to the

development of the disease (63).

This indicates that in VSCC, SFN is downregulated as a tumor

suppressor through DNA methylation, thereby promoting the

progression of the disease.

ESCC is one of the major types of esophageal cancer

in Asia and one of the most aggressive gastrointestinal cancer

types (65). The absence of

symptoms in early ESCC leads to late detection of the disease and

poor prognosis. SFN is downregulated in the early stage of ESCC,

and this downregulation is associated with a shortened survival

period, suggesting that SFN may serve as a biomarker for the early

detection of ESCC (66). Abnormal

expression of SFN affects the sensitivity of patients with ESCC to

chemotherapy drugs, which is the main pathway through which SFN is

involved in ESCC (67).

OSCC is a common cancer type and although it

accounts for only 1.5% of malignant tumors, its incidence rate is

increasing, which deserves attention. Existing studies have shown

that SFN is strongly expressed in OSCC, and the survival time of

patients with OSCC with high SFN expression is lower than that of

patients with low SFN expression, which is different from the

expression of SFN in other SCC types (68,69).

Inhibition of CpG methylation of SFN may inhibit the progression of

SCC.

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) and

cholangiocarcinoma

GBC is one of the few cancer types in developing

countries with a high mortality rate. The disease presents with

almost no obvious symptoms in its early stage, leading to most

patients being diagnosed in the middle or late stages, with a poor

prognosis (70). Given the

epithelial continuity between the gallbladder and bile duct, GBC

and cholangiocarcinoma share similar oncogenic and metastatic

mechanisms. Current effective treatments for GBC and

cholangiocarcinoma include complete tumor resection and adjuvant

therapy. However, the prognosis following surgical resection

remains poor and incidence has not declined significantly over

decades (71). Moreover, there has

been little progress in treatment (72). Therefore, it is urgent to identify

therapeutic targets and develop targeted drug therapies. At

present, there are few studies on the role and therapeutic

significance of SFN dysregulation in cholangiocarcinoma.

Epigenetics plays a key role in cancer development; however, there

is still no clear understanding of SFN DNA methylation in

cholangiocarcinoma and GBC (73,74).

As a result, research into new biomarkers for these two cancer

types has attracted significant interest from researchers. Only a

small number of studies have focused on GBC. In a study, SFN DNA

methylation was detected in 45 out of 50 GBC cases, and SFN

expression was downregulated in patients with advanced GBC (as

determined by MSP assay). These results suggest that low SFN

expression, driven by DNA methylation, may promote the progression

of GBC (75). Another study

confirmed that SFN gene upregulation is associated with an improved

prognosis, lower early cancer recurrence rates and reduced distant

metastasis after resection (72).

This suggests that detecting SFN DNA methylation or SFN expression

may represent a new approach in the treatment of GBC. Inhibiting

SFN DNA methylation may be a potential therapeutic strategy for

GBC; however, the role of SFN in the treatment of

cholangiocarcinoma remains unclear.

Pancreatic cancer (PC)

PC ranks among the highest in terms of cancer

mortality; >90% of patients with PC die due to a non-response to

treatment, which is attributed to the lack of effective diagnostic

and therapeutic strategies (76).

Therefore, it is urgent to identify the pathogenic targets in PC.

Whole-genome mapping has offered hope for improving PC management,

enabling the development of histological/serological markers and

immunotherapies. Through such efforts, SFN has emerged as a key

player in PC diagnosis and treatment (77). By analyzing the methylation patterns

of SFN, a high incidence of hypomethylation was observed in PC cell

lines and primary PC tissues, suggesting that SFN hypomethylation

is a common epigenetic event in PC. This study further showed that

SFN protein expression is significantly increased in PC (MSP

assay), and this elevated expression almost inversely correlated

with patients' survival rates (76). This suggests a potential link to PC

treatment failure. The mechanism of action of SFN in PC may involve

resistance to treatment-induced apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle

blockade, thereby causing resistance to anticancer drugs and

obstructing their therapeutic effects. For example, gemcitabine is

an important anticancer drug used in the treatment of various

cancer types, including PC. SFN methylation is regulated by DNMT1,

which is involved in the acquisition of gemcitabine resistance

(78). Elevated SFN expression also

results in resistance to mitoxantrone and doxorubicin, resistance

to drug-induced apoptosis and resistance to the G2/M cell cycle

blockade (79,80). Therefore, it is considered that SFN

may serve as a prognostic indicator to predict the survival of

patients with PC, as a biomarker to detect PC in its early stages

and as a potential target for therapeutic drugs to guide the

clinical treatment of patients. This approach is expected to bring

hope in improving the lifespan of patients with PC.

Gastric cancer (GC)

GC is a leading cause of cancer-related death

worldwide, ranking as the fifth most common cancer and third

deadliest globally (81). In China,

GC is the second most prevalent cancer and second leading cause of

cancer mortality, with a dismal prognosis (82). Despite recent progress in surgical

and pharmacological treatments, the survival rate for patients with

GC in China remains very low (~40%) (83). Therefore, it is urgent to identify

reliable therapeutic targets or develop small-molecule drugs to

treat GC or alleviate the pain it causes. Genetic predisposition

may play a key role in the development of GC (84). GC is a disease influenced by

environmental epigenetic modifications and often presents with

tumors that have a high frequency of abnormal CpG island

methylation (85). A study found

that abnormally elevated SFN expression is a biomarker of poor

prognosis in GC and is associated with shortened survival time in

patients with advanced GC (86).

Additionally, an analysis of SFN expression in tumor samples from

157 patients who underwent GC resection showed that SFN expression

was elevated in 48% of cases and was correlated with p53 expression

(86). A study has shown that after

SFN knockout, the proliferation and in vitro invasion

abilities of GC cells are reduced. Additionally, serum levels of

SFN are related to the therapeutic status of locally advanced

cancer. These findings suggest that SFN plays an important role in

the proliferation and metastasis of GC cells and may be a new

target for the detection and prevention of GC (87). Another study has shown that SFN

expression is increased in the gastric tissue of mice infected with

Helicobacter pylori. Since H. pylori is a recognized

factor in the development of GC, these results also indicate that

high expression of SFN is closely related to GC (88). Regarding the role of SFN in GC, its

effects vary across different stages of the disease. In some human

cancer types, SFN is often inactivated due to methylation of the

CpG islands, thereby losing its tumor suppressor function. This

mechanism may play an important role in undifferentiated GC. The

incidence of SFN hypermethylation was found to be 43% in primary GC

and higher in poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, suggesting

that SFN hypermethylation is more prevalent in undifferentiated GC

than in differentiated GC (as determined by

bisulfite-bisulfite-single-strand conformation polymorphism assay

(89). In differentiated GC, SFN

interacts with p53 to stabilize and enhance its transcriptional

activity (87). In another study of

60 GC samples, SFN expression was positive in 64% of cases, with

positive staining observed in low, medium and highly differentiated

GC cells. This suggests that SFN is involved in the proliferation

of GC cells (90). Therefore, these

findings indicate that SFN may be a promising target for the

treatment of GC.

Colorectal cancer (CRC)

Compared with normal colorectal tissues, SFN

expression is significantly decreased in CRC tissues. Low

expression of SFN is also significantly correlated with low

survival rates in patients with CRC (91). SFN influences CRC progression

through transcriptional programs regulated by interacting factors

(such as Snail, c-JUN, Yes-associated protein 1 and Foxo1), which

promote tumorigenesis and growth (92,93).

Additionally, LIM and SH3 protein 1 (Lasp1) drives SFN-mediated CRC

progression via PI3K/AKT pathway activation. A combination of low

SFN and high Lasp1 expression is associated with a poorer overall

survival in patients with CRC (94). Notably, there are different

viewpoints. The latest research indicates that SFN functions as an

oncogene in CRC and is associated with treatment resistance

(9,95). This suggests that SFN may have

different effects in different regions of CRC, with upregulation of

SFN in the invasive areas promoting tumor progression. Epigenetic

silencing of the SFN gene through CpG hypermethylation has been

reported in a variety of cancer types; however, this mechanism is

not thought to apply to CRC, where SFN hypermethylation and

inactivation are considered rare events (96). In invasive CRC zones, the SFN gene

regulates cell cycle progression and tumor cell migration,

promoting metastasis (9). The

contradictory expression patterns of SFN may be attributed to

spatial heterogeneity, immune cell exhaustion and dynamic

epigenetic regulation. Similar discrepancies between gene

expression and function have been documented in other organs and

tissues. Cells in distinct anatomical regions not only exhibit

divergent gene expression profiles but also display distinct

epigenetic signatures and biological functions (29,97–99).

Other cancer types

SFN is also potentially linked to other cancer

types, including glioma, endometrial cancer (EC) and prostate

cancer (PCa) (34,100,101). In a study of 186 tumor samples

from patients with different grades of glioma, higher SFN

expression was associated with higher survival rates. SFN

inactivation in glioma was also due to its DNA methylation (as

determined by MSP assay). Compared with normal tissues, SFN

expression in glioma was downregulated, suggesting that targeting

SFN DNA methylation may offer a new opportunity to improve outcomes

in patients with this disease (100,102).

SFN is expressed in the normal epithelial cells of

most organs, and its epigenetic regulation is involved in

controlling specific expression in normal cells and gene silencing

in cancer cells (34). SFN is often

absent in EC and PCa. A study has shown that CpG island methylation

of SFN is closely related to its low expression (as determined by

MSP assay) (55). Most EC cases are

detected early due to vaginal bleeding and the recurrence rate is

low after treatment (103).

However, a study of 86 cases of EC and 46 cases of normal

endometrial tissue found that SFN hypermethylation, low expression

and inactivation in EC may be associated with recurrence (as

determined by MSP assay) (104).

The role of SFN in PCa has not been extensively studied. An early

study has shown that SFN is highly expressed in normal prostate

tissue, but its expression is significantly reduced in PCa

(105). As a cell cycle regulator

and tumor suppressor, SFN downregulation in PCa may promote

tumorigenesis by bypassing DNA damage checkpoints-possibly

independent of p53 (55,106). Detection of SFN CpG methylation

could potentially be used for diagnostic and prognostic purposes in

the future.

Tumor drug development targeting SFN and its

epigenetic modifications

Over the past decade, significant progress has been

made in the field of epigenetics research in cancer (107). Numerous studies have shown that

epigenetic modifications play a crucial regulatory role in the

dysregulation of tumor cells. The reversibility of epigenetic

modifications offers a chance to rectify their abnormal

alterations. Thus, employing epigenome-targeting agents to

facilitate the normalization of aberrant methylation in cancer

cells will serve as a key strategy for treating cancer (20). While research in this area has

advanced significantly in recent years, new challenges have arisen,

including low drug specificity and toxic side effects. Hence,

developing gene-specific targeted approaches holds notable

scientific and clinical value.

SFN methylation causes chromatin structure to become

more compact by recruiting methyl-binding proteins (such as

methyl-CpG binding domain protein 2) and HDACs, ultimately

inhibiting gene expression and blocking the binding of

transcription factors (such as p53) (108,109). The DNA methylation of SFN has the

dual potential of both being a therapeutic target and diagnostic

marker. As a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker, the SFN

methylation status is detectable in body fluids (such as plasma and

urine), which provides the possibility for non-invasive cancer

screening. For example, SFN methylation in the serum of patients

with BC is positively correlated with tumor stage (110). In CRC, the SFN methylation level

predicts resistance to 5-FU chemotherapy (111). This 5-FU predictive value not only

contributes to the formulation of individualized treatment plans

but also provides biomarkers for the efficacy monitoring of

epigenetic targeted drugs. Additionally, SFN methylation is also an

indicator of the response to demethylation therapy. SFN can work

synergistically with other epigenetic drugs, such as HDAC

inhibitors. For example, AR42 (OSU-HDAC42), an HDAC inhibitor,

shows a negative correlation with SFN expression and collaborates

to inhibit tumor growth (112).

The current literature reports that DNMTIs (such as 5-Aza-CdR) can

reverse SFN methylation and restore its expression, thereby

delaying tumor progression. For instance, 5-Aza-CdR restores SFN

expression, induces G2/M phase arrest and promotes apoptosis,

enhancing radiosensitivity in osteosarcoma and BC cells (113,114). Additionally, 5-Aza-CdR-induced SFN

upregulation triggers senescence in melanoma cells, inhibiting

tumor progression (115). In EC,

SFN-mediated G2/M arrest via 5-Aza-CdR exerts direct antitumor

effects. Notably, immunotherapy is a cornerstone of cancer

treatment. Recent studies have shown that DNMTIs can potentiate

immunotherapy [such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade]

(116,117). We therefore propose exploring

novel molecules integrating methylation reversal and

immunomodulation to reactivate SFN and enhance antitumor immunity,

with promising translational potential. SFN and microenvironment

therapy may also be related to tumor progression. For example, a

hypoxic microenvironment contributes to tumor progression, while

SFN inhibits metastasis and angiogenesis in CRC induced by tumor

hypoxia through regulating hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α)

(118). Hypoxic regions in gliomas

can induce HIF-1α activation, potentially influencing SFN

expression (119). Therefore, SFN

may also play a role in mediating responses to

microenvironment-targeted therapies. Although DNMTIs can reverse

SFN methylation, preclinical and clinical studies have revealed

notable limitations: Systemic toxicity, risk of proto-oncogene

activation, suboptimal targeting in solid tumors and off-target

effects. Most notably, robust clinical evidence supporting their

efficacy remains limited (120,121). To date, to the best of our

knowledge, there have been no clinical trials directly targeting

SFN methylation. In the existing studies, abnormal methylation of

SFN has been observed in the majority of cancer types (Table I). Therefore, developing antitumor

drugs targeting SFN methylation is also a promising strategy. In a

very small number of cancer types such as CRC, SFN exhibits a dual

role. However, the underlying reasons for these differences are not

clear, so further research is needed before conducting in-depth

studies on specific targeted treatment strategies.

| Table I.Relationship between DNA methylation

state and the expression level of 14-3-3σ in different cancer

types. |

Table I.

Relationship between DNA methylation

state and the expression level of 14-3-3σ in different cancer

types.

| Cancer type | DNA methylation

state | Expression of

14-3-3σ | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Breast cancer | High | Low | (31) |

| Kidney cancer | High | Low | (49) |

| Ovarian cancer | High | Low | (55) |

| Nasopharyngeal

cancer | High | Low | (58) |

| Vulvar squamous

cell carcinoma | High | Low | (64) |

| Gallbladder

cancer | High | Low | (75) |

| Glioma | High | Low | (100) |

| Gastric cancer

(primary) | High | Low | (89) |

| Endometrial

cancer | High | Low | (55) |

| Lung cancer | High/Low | Low/High | (41,43) |

| Pancreatic

cancer | Low | High | (76) |

| Oral squamous cell

carcinoma | / | High | (68) |

| Prostatic

cancer | / | Low | (105) |

| Esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma | / | Low | (66) |

| Colorectal

cancer | / | Low | (91) |

Conclusions and perspectives

The SFN protein is a core molecule in cell cycle

regulation and the DNA damage response, and its functional

inactivation is closely related to cancer initiation and

progression. In the present review, the epigenetic regulation

mechanisms and clinical significance of this protein in various

tumor types were systematically summarized (Fig. 1 and Table SI). Silencing of SFN expression is

not only caused by gene mutation or deletion but also by abnormal

hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands. This epigenetic silencing

shows tissue-specific patterns in BC, PCa and LC and is positively

associated with tumor aggressiveness. Although the degree of DNA

methylation varies among different cancer types, SFN methylation

leads to G2/M checkpoint failure and apoptotic resistance, thereby

promoting genomic instability. There are also some specific

mechanisms. These findings suggest the pivotal role of SFN in

precision therapy.

| Figure 1.Role of DNA methylation of SFN in

cancer. SFN, 14-3-3σ; BC, breast cancer; LC, lung cancer; KC,

kidney cancer; OC, ovarian cancer; NPC, nasopharyngeal cancer; SCC,

squamous cell carcinoma; GBC, gall blader cancer; PC, pancreatic

cancer; GC, gastric cancer; CRC, colorectal cancer. |

At present, to the best of our knowledge, there are

no clinical guidelines incorporating SFN methylation detection.

Through a literature review, we conclude that SFN methylation, as a

prognostic marker, holds certain clinical significance. SFN

methylation precedes abnormal protein expression, in contrast to

prostate-specific antigen/CA-125 that often serve as late-stage

indicators. SFN methylation is prognostically relevant across

multiple cancer types (such breast and lung cancer), supporting the

development of pan-cancer screening strategies. Additionally, SFN

methylation directly mediates resistance to cisplatin/gemcitabine,

a mechanism unaddressed by traditional markers. Thus, we consider

that SFN methylation profiling holds significant clinical utility

as a biomarker.

The existing challenges and breakthroughs highlight

the need for in-depth mechanistic research. At present, to the best

of our knowledge, the upstream driving factors of SFN methylation

have not been fully analyzed. The synergistic mechanisms between

methylation and other epigenetic modifications need to be clarified

through multi-omics integration analyses. The technical bottleneck

in clinical transformation lies in the insufficient sensitivity of

existing detection technologies for low-abundance methylated

circulating tumor DNA. At present, there is a lack of specific SFN

methylation inhibitors, and methyltransferase inhibitors also have

some unresolved clinical challenges. Systemic off-target effects of

DNMTIs, such as decitabine, may result from the activation of

proto-oncogenes. Therefore, further exploration of tumor-targeted

delivery strategies is needed. There is room for innovation in

therapeutic strategies. ‘Pulsed administration’ based on

methylation dynamics may balance demethylation efficacy and

toxicity. Combining epigenetic editing with immune checkpoint

blocking may break tumor immune tolerance. With the development of

single-cell epigenomics and spatial multi-omics techniques, it will

be possible to analyze the role of SFN methylation in the evolution

of tumor heterogeneity. We therefore propose that the development

of bi-functional molecules with both methylation reversal and

immune regulation functions, such as DNMT-PD-L1 dual-target

inhibitors, may provide a new paradigm for overcoming therapeutic

resistance. SFN is expected to become a signature target in the

field of cancer epigenetic therapy in these new modalities. Other

epigenetic modifications also need the attention of researchers,

such as RNA modifications and histone modifications, which may

drive cancer progression through synergistic or independent

effects. In the future, research should focus on multi-modification

interactions, dynamic regulation and precise intervention

strategies, combined with technological innovation and clinical

validation, to provide new targets and paradigms for cancer

treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

DH, YH wrote the main manuscript text and DN was

involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for

important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

de Visser KE and Joyce JA: The evolving

tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic

outgrowth. Cancer Cell. 41:374–403. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Arafeh R, Shibue T, Dempster JM, Hahn WC

and Vazquez F: The present and future of the cancer dependency map.

Nat Rev Cancer. 25:59–73. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mathers JC, Strathdee G and Relton CL:

Induction of epigenetic alterations by dietary and other

environmental factors. Adv Genet. 71:3–39. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gupta MK, Peng H, Li Y and Xu CJ: The role

of DNA methylation in personalized medicine for immune-related

diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 250:1085082023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bergstedt J, Azzou SAK, Tsuo K,

Jaquaniello A, Urrutia A, Rotival M, Lin DTS, MacIsaac JL, Kobor

MS, Albert ML, et al: The immune factors driving DNA methylation

variation in human blood. Nat Commun. 13:58952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zeng Y and Chen T: DNA methylation

reprogramming during mammalian development. Genes (Basel).

10:2572019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tolmacheva EN, Vasilyev SA and Lebedev IN:

Aneuploidy and DNA methylation as mirrored features of early human

embryo development. Genes (Basel). 11:10842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Klutstein M, Nejman D, Greenfield R and

Cedar H: DNA methylation in cancer and aging. Cancer Res.

76:3446–3450. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Huang Y, Yang M and Huang W: 14-3-3 σ: A

potential biomolecule for cancer therapy. Clin Chim Acta.

511:50–58. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Iwahori S, Umaña AC, Kalejta RF and Murata

T: Serine 13 of the human cytomegalovirus viral cyclin-dependent

kinase UL97 is required for regulatory protein 14-3-3 binding and

UL97 stability. J Biol Chem. 298:1025132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Suárez-Bonnet A, Lara-Garcia A, Stoll AL,

Carvalho S and Priestnall SL: 14-3-3σ protein expression in canine

renal cell carcinomas. Vet Pathol. 55:233–240. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gu Q, Cuevas E, Raymick J, Kanungo J and

Sarkar S: Downregulation of 14-3-3 proteins in Alzheimer's disease.

Mol Neurobiol. 57:32–40. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Obsil T, Ghirlando R, Klein DC, Ganguly S

and Dyda F: Crystal structure of the 14-3-3zeta:serotonin

N-acetyltransferase complex. A role for scaffolding in enzyme

regulation. Cell. 105:257–267. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mhawech P: 14-3-3 proteins-an update. Cell

Res. 15:228–236. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hermeking H and Benzinger A: 14-3-3

Proteins in cell cycle regulation. Semin Cancer Biol. 16:183–192.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Henry RE, Andrysik Z, Paris R, Galbraith

MD and Espinosa JM: A DR4:tBID axis drives the p53 apoptotic

response by promoting oligomerization of poised BAX. EMBO J.

31:1266–1278. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Pozuelo-Rubio M: 14-3-3 Proteins are

regulators of autophagy. Cells. 1:754–773. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lodygin D and Hermeking H: The role of

epigenetic inactivation of 14-3-3sigma in human cancer. Cell Res.

15:237–246. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Raychaudhuri K, Chaudhary N, Gurjar M,

D'Souza R, Limzerwala J, Maddika S and Dalal SN: 14-3-3σ gene loss

leads to activation of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition due

to the stabilization of c-Jun protein. J Biol Chem.

291:16068–16081. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sun L, Zhang H and Gao P: Metabolic

reprogramming and epigenetic modifications on the path to cancer.

Protein Cell. 13:877–919. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Meng H, Cao Y, Qin J, Song X, Zhang Q, Shi

Y and Cao L: DNA methylation, its mediators and genome integrity.

Int J Biol Sci. 11:604–617. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dai X, Ren T, Zhang Y and Nan N:

Methylation multiplicity and its clinical values in cancer. Expert

Rev Mol Med. 23:e22021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Suo XG, Wang JN, Zhu Q, Zhang MM, Ge QL,

Peng LJ, Wang YY, Ji ML, Ou YM, Yu JT, et al: METTL3 mediated m6A

modification of HKDC1 promotes renal injury and inflammation in

lead nephropathy. Int J Biol Sci. 21:3755–3775. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Nishiyama A and Nakanishi M: Navigating

the DNA methylation landscape of cancer. Trends Genet.

37:1012–1027. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kulis M and Esteller M: DNA methylation

and cancer. Adv Genet. 70:27–56. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ku JL, Jeon YK and Park JG:

Methylation-specific PCR. Methods Mol Biol. 791:23–32. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Horie-Inoue K and Inoue S: Epigenetic and

proteolytic inactivation of 14-3-3sigma in breast and prostate

cancers. Semin Cancer Biol. 16:235–239. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Jayaprakash C, Radhakrishnan R, Ray S and

Satyamoorthy K: Promoter methylation of MGMT in oral carcinoma: A

population-based study and meta-analysis. Arch Oral Biol.

80:197–208. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liang WW, Lu RJ, Jayasinghe RG, Foltz SM,

Porta-Pardo E, Geffen Y, Wendl MC, Lazcano R, Kolodziejczak I, Song

Y, et al: Integrative multi-omic cancer profiling reveals DNA

methylation patterns associated with therapeutic vulnerability and

cell-of-origin. Cancer Cell. 41:1567–1585.e7. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Barzaman K, Karami J, Zarei Z,

Hosseinzadeh A, Kazemi MH, Moradi-Kalbolandi S, Safari E and

Farahmand L: Breast cancer: Biology, biomarkers, and treatments.

Int Immunopharmacol. 84:1065352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Gheibi A, Kazemi M, Baradaran A, Akbari M

and Salehi M: Study of promoter methylation pattern of 14-3-3 sigma

gene in normal and cancerous tissue of breast: A potential

biomarker for detection of breast cancer in patients. Adv Biomed

Res. 1:802012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Luo J, Feng J, Lu J, Wang Y, Tang X, Xie F

and Li W: Aberrant methylation profile of 14-3-3 sigma and its

reduced transcription/expression levels in Chinese sporadic female

breast carcinogenesis. Med Oncol. 27:791–797. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Umbricht CB, Evron E, Gabrielson E,

Ferguson A, Marks J and Sukumar S: Hypermethylation of 14-3-3 sigma

(stratifin) is an early event in breast cancer. Oncogene.

20:3348–3353. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lodygin D and Hermeking H: Epigenetic

silencing of 14-3-3sigma in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 16:214–224.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zurita M, Lara PC, del Moral R, Torres B,

Linares-Fernández JL, Arrabal SR, Martínez-Galán J, Oliver FJ and

Ruiz de Almodóvar JM: Hypermethylated 14-3-3-sigma and ESR1 gene

promoters in serum as candidate biomarkers for the diagnosis and

treatment efficacy of breast cancer metastasis. BMC Cancer.

10:2172010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ko S, Kim JY, Jeong J, Lee JE, Yang WI and

Jung WH: The role and regulatory mechanism of 14-3-3 sigma in human

breast cancer. J Breast Cancer. 17:207–218. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, Gainor JF

and Heist RS: Lung cancer. Lancet. 398:535–554. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Petrella F, Rizzo S, Attili I, Passaro A,

Zilli T, Martucci F, Bonomo L, Del Grande F, Casiraghi M, De

Marinis F and Spaggiari L: Stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: An

overview of treatment options. Curr Oncol. 30:3160–3175. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Giaccone G and He Y: Current knowledge of

small cell lung cancer transformation from non-small cell lung

cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 94:1–10. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ansari J, Shackelford RE and El-Osta H:

Epigenetics in non-small cell lung cancer: From basics to

therapeutics. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 5:155–171. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Raungrut P, Petjaroen P, Geater SL,

Keeratichananont W, Phukaoloun M, Suwiwat S and Thongsuksai P:

Methylation of 14-3-3σ gene and prognostic significance of 14-3-3σ

expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 14:5257–5264.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Qin X, Qiu F and Zou Z: TRIM25 is

associated with cisplatin resistance in non-small-cell lung

carcinoma A549 cell line via downregulation of 14-3-3σ. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 493:568–572. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Radhakrishnan VM, Jensen TJ, Cui H,

Futscher BW and Martinez JD: Hypomethylation of the 14-3-3σ

promoter leads to increased expression in non-small cell lung

cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 50:830–836. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bahadoram S, Davoodi M, Hassanzadeh S,

Bahadoram M, Barahman M and Mafakher L: Renal cell carcinoma: An

overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. G Ital

Nefrol. 39:2022–vol3. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Cirillo L, Innocenti S and Becherucci F:

Global epidemiology of kidney cancer. Nephrol Dial Transplant.

39:920–928. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bukavina L, Bensalah K, Bray F, Carlo M,

Challacombe B, Karam JA, Kassouf W, Mitchell T, Montironi R,

O'Brien T, et al: Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma: 2022

Update. Eur Urol. 82:529–542. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chow WH, Dong LM and Devesa SS:

Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol.

7:245–257. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hancock SB and Georgiades CS: Kidney

cancer. Cancer J. 22:387–392. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Liang S, Xu Y, Shen G, Zhao X, Zhou J, Li

X, Gong F, Ling B, Fang L, Huang C and Wei Y: Gene expression and

methylation status of 14-3-3sigma in human renal carcinoma tissues.

IUBMB Life. 60:534–540. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Vasko R, Mueller GA, von Jaschke AK, Asif

AR and Dihazi H: Impact of cisplatin administration on protein

expression levels in renal cell carcinoma: A proteomic analysis.

Eur J Pharmacol. 670:50–57. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Penny SM: Ovarian cancer: An overview.

Radiol Technol. 91:561–575. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Konstantinopoulos PA and Matulonis UA:

Clinical and translational advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Nat

Cancer. 4:1239–1257. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

O'Shea AS: Clinical staging of ovarian

cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2424:3–10. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Thi HV, Ngo AD and Chu DT: Epigenetic

regulation in ovarian cancer. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 387:77–98.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Mhawech P, Benz A, Cerato C, Greloz V,

Assaly M, Desmond JC, Koeffler HP, Lodygin D, Hermeking H, Herrmann

F and Schwaller J: Downregulation of 14-3-3sigma in ovary, prostate

and endometrial carcinomas is associated with CpG island

methylation. Mod Pathol. 18:340–348. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Dee EC, Wang S, Ho FDV, Patel RR, Lapen K,

Wu Y, Yang F, Patel TA, Feliciano EJG, McBride SM and Lee NY:

Nasopharynx cancer in the United States: Racial and ethnic

disparities in stage at presentation. Laryngoscope. 135:1113–1119.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Su ZY, Siak PY, Lwin YY and Cheah SC:

Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Current insights and

future outlook. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 43:919–939. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Chan SY, To KF, Leung SF, Yip WW, Mak MK,

Chung GT and Lo KW: 14-3-3 sigma expression as a prognostic marker

in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncol Rep.

24:949–955. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Xie L, Jiang T, Cheng A, Zhang T, Huang P,

Li P, Wen G, Lei F, Huang Y, Tang X, et al: MiR-597 targeting

14-3-3σ enhances cellular invasion and EMT in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cells. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 12:105–114. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhang T, Lei F, Jiang T, Xie L, Huang P,

Li P, Huang Y, Tang X, Gong J, Lin Y, et al: H19/miR-675-5p

targeting SFN enhances the invasion and metastasis of

nasalpharyngeal cancer cells. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 12:324–333. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Huang WG, Cheng AL, Chen ZC, Peng F, Zhang

PF, Li MY, Li F, Li JL, Li C, Yi H, et al: Targeted proteomic

analysis of 14-3-3sigma in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Biochem

Cell Biol. 42:137–147. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Nakajima T, Shimooka H, Weixa P, Segawa A,

Motegi A, Jian Z, Masuda N, Ide M, Sano T, Oyama T, et al:

Immunohistochemical demonstration of 14-3-3 sigma protein in normal

human tissues and lung cancers, and the preponderance of its strong

expression in epithelial cells of squamous cell lineage. Pathol

Int. 53:353–360. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Wang Z, Tropè CG, Suo Z, Trøen G, Yang G,

Nesland JM and Holm R: The clinicopathological and prognostic

impact of 14-3-3 sigma expression on vulvar squamous cell

carcinomas. BMC Cancer. 8:3082008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Gasco M, Sullivan A, Repellin C, Brooks L,

Farrell PJ, Tidy JA, Dunne B, Gusterson B, Evans DJ and Crook T:

Coincident inactivation of 14-3-3sigma and p16INK4a is an early

event in vulval squamous neoplasia. Oncogene. 21:1876–1881. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Okumura H, Kita Y, Yokomakura N, Uchikado

Y, Setoyama T, Sakurai H, Omoto I, Matsumoto M, Owaki T, Ishigami S

and Natsugoe S: Nuclear expression of 14-3-3 sigma is related to

prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Anticancer Res. 30:5175–5179. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Qi YJ, Wang M, Liu RM, Wei H, Chao WX,

Zhang T, Lou Q, Li XM, Ma J, Zhu H, et al: Downregulation of

14-3-3σ correlates with multistage carcinogenesis and poor

prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One.

9:e953862014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Lai KKY, Chan KT, Choi MY, Wang HK, Fung

EYM, Lam HY, Tan W, Tung LN, Tong DKH, Sun RWY, et al: 14-3-3σ

confers cisplatin resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

cells via regulating DNA repair molecules. Tumour Biol.

37:2127–2136. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Hayashi E, Kuramitsu Y, Fujimoto M, Zhang

X, Tanaka T, Uchida K, Fukuda T, Furumoto H, Ueyama Y and Nakamura

K: Proteomic profiling of differential display analysis for human

oral squamous cell carcinoma: 14-3-3 σ protein is upregulated in

human oral squamous cell carcinoma and dependent on the

differentiation level. Proteomics Clin Appl. 3:1338–1347. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Laimer K, Blassnig N, Spizzo G, Kloss F,

Rasse M, Obrist P, Schäfer G, Perathoner A, Margreiter R and

Amberger A: Prognostic significance of 14-3-3sigma expression in

oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Oral Oncol. 45:127–134. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wang S, Zheng R, Li J, Zeng H, Li L, Chen

R, Sun K, Han B, Bray F, Wei W and He J: Global, regional, and

national lifetime risks of developing and dying from

gastrointestinal cancers in 185 countries: A population-based

systematic analysis of GLOBOCAN. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

9:229–237. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Hu Z, Wang X, Zhang X, Sun W and Mao J: An

analysis of the global burden of gallbladder and biliary tract

cancer attributable to high BMI in 204 countries and territories:

1990-2021. Front Nutr. 11:15217702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Sirivatanauksorn V, Dumronggittigule W,

Dulnee B, Srisawat C, Sirivatanauksorn Y, Pongpaibul A, Masaratana

P, Somboonyosdech C, Sripinitchai S, Kositamongkol P, et al: Role

of stratifin (14-3-3 sigma) in adenocarcinoma of gallbladder: A

novel prognostic biomarker. Surg Oncol. 32:57–62. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Sharma A, Sharma KL, Gupta A, Yadav A and

Kumar A: Gallbladder cancer epidemiology, pathogenesis and

molecular genetics: Recent update. World J Gastroenterol.

23:3978–3998. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Nakaoka T, Saito Y and Saito H: Aberrant

DNA methylation as a biomarker and a therapeutic target of

cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 18:11112017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Singh TD, Gupta S, Shrivastav BR and

Tiwari PK: Epigenetic profiling of gallbladder cancer and gall

stone diseases: Evaluation of role of tumour associated genes.

Gene. 576:743–752. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Li Z, Dong Z, Myer D, Yip-Schneider M, Liu

J, Cui P, Schmidt CM and Zhang JT: Role of 14-3-3σ in poor

prognosis and in radiation and drug resistance of human pancreatic

cancers. BMC Cancer. 10:5982010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Rodriguez JA, Li M, Yao Q, Chen C and

Fisher WE: Gene overexpression in pancreatic adenocarcinoma:

Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. World J Surg. 29:297–305.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Qin L, Dong Z and Zhang JT: Reversible

epigenetic regulation of 14-3-3σ expression in acquired gemcitabine

resistance by uhrf1 and DNA methyltransferase 1. Mol Pharmacol.

86:561–569. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Dim DC, Jiang F, Qiu Q, Li T, Darwin P,

Rodgers WH and Peng HQ: The usefulness of S100P, mesothelin,

fascin, prostate stem cell antigen, and 14-3-3 sigma in diagnosing

pancreatic adenocarcinoma in cytological specimens obtained by

endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn

Cytopathol. 42:193–199. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Qin L, Dong Z and Zhang JT: 14-3-3σ

regulation of and interaction with YAP1 in acquired gemcitabine

resistance via promoting ribonucleotide reductase expression.

Oncotarget. 7:17726–17736. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Venneman K, Huybrechts I, Gunter MJ,

Vandendaele L, Herrero R and Van Herck K: The epidemiology of

Helicobacter pylori infection in Europe and the impact of lifestyle

on its natural evolution toward stomach cancer after infection: A

systematic review. Helicobacter. 23:e124832018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Zhu Y, Jeong S, Wu M, Zhou JY, Jin ZY, Han

RQ, Yang J, Zhang XF, Wang XS, Liu AM, et al: Index-based dietary

patterns and stomach cancer in a Chinese population. Eur J Cancer

Prev. 30:448–456. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Zhang Y, Li Y, Lin C, Ding J, Liao G and

Tang B: Aberrant upregulation of 14-3-3σ and EZH2 expression serves

as an inferior prognostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma.

PLoS One. 9:e1072512014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Kim W, Kidambi T, Lin J and Idos G:

Genetic syndromes associated with gastric cancer. Gastrointest

Endosc Clin N Am. 32:147–162. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Chen YZ, Guo F, Sun HW, Kong HR, Dai SJ,

Huang SH, Zhu WW, Yang WJ and Zhou MT: Association between XPG

polymorphisms and stomach cancer susceptibility in a Chinese

population. J Cell Mol Med. 20:903–908. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Muhlmann G, Ofner D, Zitt M, Müller HM,

Maier H, Moser P, Schmid KW, Zitt M and Amberger A: 14-3-3 Sigma

and p53 expression in gastric cancer and its clinical applications.

Dis Markers. 29:21–29. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Jung JY, Koh SA, Lee KH and Kim JR: 14-3-3

Sigma protein contributes to hepatocyte growth factor-mediated cell

proliferation and invasion via matrix metalloproteinase-1

regulation in human gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 42:519–530.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Nagappan A, Park HS, Park KI, Hong GE,

Yumnam S, Lee HJ, Kim MK, Kim EH, Lee WS, Lee WJ, et al:

Helicobacter pylori infection combined with DENA revealed altered

expression of p53 and 14-3-3 isoforms in Gulo-/- mice. Chem Biol

Interact. 206:143–152. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Suzuki H, Itoh F, Toyota M, Kikuchi T,

Kakiuchi H and Imai K: Inactivation of the 14-3-3 sigma gene is

associated with 5′ CpG island hypermethylation in human cancers.

Cancer Res. 60:4353–4357. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Li YL, Liu L, Xiao Y, Zeng T and Zeng C:

14-3-3σ is an independent prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer

and is associated with apoptosis and proliferation in gastric

cancer. Oncol Lett. 9:290–294. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Young GM, Radhakrishnan VM, Centuori SM,

Gomes CJ and Martinez JD: Comparative analysis of 14-3-3 isoform

expression and epigenetic alterations in colorectal cancer. BMC

Cancer. 15:8262015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Winter M, Rokavec M and Hermeking H:

14-3-3σ functions as an intestinal tumor suppressor. Cancer Res.

81:3621–3634. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Shao Q, Duong TN, Park I, Orr LM and

Nomura DK: Targeted protein localization by covalent 14-3-3

recruitment. J Am Chem Soc. 146:24788–24799. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Shao Z, Cai Y, Xu L, Yao X, Shi J, Zhang

F, Luo Y, Zheng K, Liu J, Deng F, et al: Loss of the 14-3-3σ is

essential for LASP1-mediated colorectal cancer progression via

activating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 6:256312016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Lonare A, Raychaudhuri K, Shah S, Madhu G,

Sachdeva A, Basu S, Thorat R, Gupta S and Dalal SN: 14-3-3σ

restricts YY1 to the cytoplasm, promoting therapy resistance, and

tumor progression in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 156:623–637.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Ide M, Nakajima T, Asao T and Kuwano H:

Inactivation of 14-3-3sigma by hypermethylation is a rare event in

colorectal cancers and its expression may correlate with cell cycle

maintenance at the invasion front. Cancer Lett. 207:241–249. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Ben-Moshe S and Itzkovitz S: Spatial

heterogeneity in the mammalian liver. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 16:395–410. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Postwala H, Shah Y, Parekh PS and

Chorawala MR: Unveiling the genetic and epigenetic landscape of

colorectal cancer: New insights into pathogenic pathways. Med

Oncol. 40:3342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Klemm SL, Shipony Z and Greenleaf WJ:

Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat Rev

Genet. 20:207–220. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Deng J, Gao G, Wang L, Wang T, Yu J and

Zhao Z: Stratifin expression is a novel prognostic factor in human

gliomas. Pathol Res Pract. 207:674–679. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Ito K, Suzuki T, Akahira J, Sakuma M,

Saitou S, Okamoto S, Niikura H, Okamura K, Yaegashi N, Sasano H and

Inoue S: 14-3-3sigma in endometrial cancer-a possible prognostic

marker in early-stage cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 11:7384–7391. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Liang S, Shen G, Liu Q, Xu Y, Zhou L, Xiao

S, Xu Z, Gong F, You C and Wei Y: Isoform-specific expression and

characterization of 14-3-3 proteins in human glioma tissues

discovered by stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell

culture-based proteomic analysis. Proteomics Clin Appl. 3:743–753.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Iavazzo C, Gkegkes ID and Vrachnis N:

Early recurrence of early stage endometrioid endometrial carcinoma:

Possible etiologic pathways and management options. Maturitas.

78:155–159. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Nakayama H, Sano T, Motegi A, Oyama T and

Nakajima T: Increasing 14-3-3 sigma expression with declining

estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen-responsive finger protein

expression defines malignant progression of endometrial carcinoma.

Pathol Int. 55:707–715. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Evren S, Dermen A, Lockwood G, Fleshner N

and Sweet J: mTOR-RAPTOR and 14-3-3σ immunohistochemical expression

in high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic

adenocarcinomas: A tissue microarray study. J Clin Pathol.

64:683–688. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Lodygin D, Diebold J and Hermeking H:

Prostate cancer is characterized by epigenetic silencing of

14-3-3sigma expression. Oncogene. 23:9034–9041. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Chu DT, Ngo AD and Wu CC: Epigenetics in

cancer development, diagnosis and therapy. Prog Mol Biol Transl

Sci. 198:73–92. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Devailly G, Grandin M, Perriaud L, Mathot

P, Delcros JG, Bidet Y, Morel AP, Bignon JY, Puisieux A, Mehlen P

and Dante R: Dynamics of MBD2 deposition across methylated DNA

regions during malignant transformation of human mammary epithelial

cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:5838–5854. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Feng L, Pan M, Sun J, Lu H, Shen Q, Zhang

S, Jiang T, Liu L, Jin W, Chen Y, et al: Histone deacetylase 3

inhibits expression of PUMA in gastric cancer cells. J Mol Med

(Berl). 91:49–58. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Ye M, Huang T, Ying Y, Li J, Yang P, Ni C,

Zhou C and Chen S: Detection of 14-3-3 sigma (σ) promoter

methylation as a noninvasive biomarker using blood samples for

breast cancer diagnosis. Oncotarget. 8:9230–9242. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Sakai A, Otani M, Miyamoto A, Yoshida H,

Furuya E and Tanigawa N: Identification of phosphorylated serine-15

and −82 residues of HSPB1 in 5-fluorouracil-resistant colorectal

cancer cells by proteomics. J Proteomics. 75:806–818. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Balch C, Naegeli K, Nam S, Ballard B,

Hyslop A, Melki C, Reilly E, Hur MW and Nephew KP: A unique histone

deacetylase inhibitor alters microRNA expression and signal

transduction in chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Biol

Ther. 13:681–693. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Li Y, Geng P, Jiang W, Wang Y, Yao J, Lin

X, Liu J, Huang L, Su B and Chen H: Enhancement of radiosensitivity

by 5-Aza-CdR through activation of G2/M checkpoint response and